Battle of Patras (1687) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Morean War ( it, Guerra di Morea), also known as the Sixth Ottoman–Venetian War, was fought between 1684–1699 as part of the wider conflict known as the "

Venice had held several islands in the Aegean and the Ionian seas, together with strategically positioned forts along the coast of the Greek mainland since the carving up of the

Venice had held several islands in the Aegean and the Ionian seas, together with strategically positioned forts along the coast of the Greek mainland since the carving up of the

The first target of the Venetian fleet was the island of Lefkada (Santa Maura). Morosini's political rival, Girolamo Corner, tried to preempt him and seize the Santa Maura fortress (which he believed to be lightly defended) before the arrival of the fleet from Venice. With a small force he sailed from Corfu to the island, but finding the fortress strongly garrisoned, he turned back. As a result of this misadventure, Corner was sidelined for the first year of the war, during which he served as '' provveditore generale'' of the Ionian Islands, before he was appointed to command in

The first target of the Venetian fleet was the island of Lefkada (Santa Maura). Morosini's political rival, Girolamo Corner, tried to preempt him and seize the Santa Maura fortress (which he believed to be lightly defended) before the arrival of the fleet from Venice. With a small force he sailed from Corfu to the island, but finding the fortress strongly garrisoned, he turned back. As a result of this misadventure, Corner was sidelined for the first year of the war, during which he served as '' provveditore generale'' of the Ionian Islands, before he was appointed to command in  The Venetians then crossed onto the mainland region of

The Venetians then crossed onto the mainland region of

In the next year, the Ottomans seized the initiative by attacking Kelefa in early March, forcing Morosini to hasten his departure from the Ionian Islands. The Ottomans raised the siege and withdrew at the arrival of a Venetian fleet under Venieri, and on 30 March, Morosini began landing his troops in the

In the next year, the Ottomans seized the initiative by attacking Kelefa in early March, forcing Morosini to hasten his departure from the Ionian Islands. The Ottomans raised the siege and withdrew at the arrival of a Venetian fleet under Venieri, and on 30 March, Morosini began landing his troops in the  The Venetians then, in a lightning move, retired their field army from Messenia and landed it at Tolo between 30 July and 4 August, within striking distance of the capital of the Peloponnese, Nauplia. On the very first day, Königsmarck led his troops to capture the hill of Palamidi, then only poorly fortified, which overlooked the town. The commander of the city, Mustapha Pasha, moved the civilians to the citadel of

The Venetians then, in a lightning move, retired their field army from Messenia and landed it at Tolo between 30 July and 4 August, within striking distance of the capital of the Peloponnese, Nauplia. On the very first day, Königsmarck led his troops to capture the hill of Palamidi, then only poorly fortified, which overlooked the town. The commander of the city, Mustapha Pasha, moved the civilians to the citadel of

In the meantime, the Ottomans had formed a strong entrenched camp at

In the meantime, the Ottomans had formed a strong entrenched camp at

The Venetian position in the Peloponnese could not be secure as long as the Ottomans held onto eastern Central Greece, where Thebes and Negroponte ( Chalkis) were significant military strongholds. Thus, on 21 September 1687, Königsmarck's army, 10,750 men strong, landed at

The Venetian position in the Peloponnese could not be secure as long as the Ottomans held onto eastern Central Greece, where Thebes and Negroponte ( Chalkis) were significant military strongholds. Thus, on 21 September 1687, Königsmarck's army, 10,750 men strong, landed at  Despite the fall of Athens, Morosini's position was not secure. The Ottomans were amassing an army at Thebes, and their 2,000-strong cavalry effectively controlled

Despite the fall of Athens, Morosini's position was not secure. The Ottomans were amassing an army at Thebes, and their 2,000-strong cavalry effectively controlled

On 3 April 1688, Morosini was elected as the new

On 3 April 1688, Morosini was elected as the new

Venetians had important ties and considerable support among the Montenegrins, with solid ground established previously during the Cretan war. Venice strongly considered placing Montenegro under its own protection. In 1685, Montenegrin Metropolitan

Venetians had important ties and considerable support among the Montenegrins, with solid ground established previously during the Cretan war. Venice strongly considered placing Montenegro under its own protection. In 1685, Montenegrin Metropolitan

The

The

Great Turkish War

The Great Turkish War (german: Großer Türkenkrieg), also called the Wars of the Holy League ( tr, Kutsal İttifak Savaşları), was a series of conflicts between the Ottoman Empire and the Holy League consisting of the Holy Roman Empire, Pola ...

", between the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia, ...

and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. Military operations ranged from Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

to the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek language, Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish language, Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It ...

, but the war's major campaign was the Venetian conquest of the Morea (Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic regions of Greece, geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmu ...

) peninsula in southern Greece. On the Venetian side, the war was fought to avenge the loss of Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

in the Cretan War (1645–1669)

The Cretan War ( el, Κρητικός Πόλεμος, tr, Girit'in Fethi), also known as the War of Candia ( it, Guerra di Candia) or the Fifth Ottoman–Venetian War, was a conflict between the Republic of Venice and her allies (chief among ...

. It happened while the Ottomans were entangled in their northern struggle against the Habsburgs

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

beginning with the failed Ottoman attempt to conquer Vienna and ending with the Habsburgs gaining Buda and the whole of Hungary, leaving the Ottoman Empire unable to concentrate its forces against the Venetians. As such, the Morean War was the only Ottoman–Venetian conflict from which Venice emerged victorious, gaining significant territory. Venice's expansionist revival would be short-lived, as its gains would be reversed

Reversal may refer to:

* Medical reversal, when a medical intervention falls out of use after improved clinical trials demonstrate its ineffectiveness or harmfulness.

* Reversal (law), the setting aside of a decision of a lower court by a higher c ...

by the Ottomans in 1718.

Background

Venice had held several islands in the Aegean and the Ionian seas, together with strategically positioned forts along the coast of the Greek mainland since the carving up of the

Venice had held several islands in the Aegean and the Ionian seas, together with strategically positioned forts along the coast of the Greek mainland since the carving up of the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

after the Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

. With the rise of the Ottomans

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

, during the 16th and early 17th centuries, the Venetians lost most of these, including Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

and Euboea

Evia (, ; el, Εύβοια ; grc, Εὔβοια ) or Euboia (, ) is the second-largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete. It is separated from Boeotia in mainland Greece by the narrow Euripus Strait (only at its narrowest poin ...

(Negropont

Evia (, ; el, Εύβοια ; grc, Εὔβοια ) or Euboia (, ) is the second-largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete. It is separated from Boeotia in mainland Greece by the narrow Euripus Strait (only at its narrowest poin ...

) to the Turks. Between 1645 and 1669, the Venetians and the Ottomans fought a long and costly war over the last major Venetian possession in the Aegean, Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

. During this war, the Venetian commander, Francesco Morosini, made contact with the rebellious Maniots

The Maniots or Maniates ( el, Μανιάτες) are the inhabitants of Mani Peninsula, located in western Laconia and eastern Messenia, in the southern Peloponnese, Greece. They were also formerly known as Mainotes and the peninsula as ''Maina''. ...

. They agreed to conduct a joint campaign in the Morea. In 1659, Morosini landed in the Morea, and together with the Maniots, he took Kalamata. He was soon after forced to return to Crete, and the Peloponnesian venture failed.

During the 17th century, the Ottomans remained the premier political and military power in Europe, but signs of decline were evident: the Ottoman economy suffered from the influx of gold and silver from the Americas, an increasingly unbalanced budget and repeated devaluations of the currency, while the traditional timariot

Timariot (or ''tımar'' holder; ''tımarlı'' in Turkish) was the name given to a Sipahi cavalryman in the Ottoman army. In return for service, each timariot received a parcel of revenue called a timar, a fief, which were usually recently conquer ...

cavalry system and the Janissaries

A Janissary ( ota, یڭیچری, yeŋiçeri, , ) was a member of the elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman Sultan's household troops and the first modern standing army in Europe. The corps was most likely established under sultan Orhan ( ...

, who formed the core of the Ottoman armies, declined in quality and were increasingly replaced by irregular forces that were inferior to the regular European armies. The reform efforts of Sultan Murad IV

Murad IV ( ota, مراد رابع, ''Murād-ı Rābiʿ''; tr, IV. Murad, was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1623 to 1640, known both for restoring the authority of the state and for the brutality of his methods. Murad IV was born in Cons ...

(), and the able administration of the Köprülü dynasty of Grand Viziers

Grand vizier ( fa, وزيرِ اعظم, vazîr-i aʾzam; ota, صدر اعظم, sadr-ı aʾzam; tr, sadrazam) was the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. The office of Grand Vizier was first h ...

, whose members governed the Empire from 1656 to 1683, managed to sustain Ottoman power and even enabled it to conquer Crete, but the long and drawn-out war there exhausted Ottoman resources.

As a result of the Polish–Ottoman War (1672–76), the Ottomans secured their last territorial expansion in Europe with the conquest of Podolia

Podolia or Podilia ( uk, Поділля, Podillia, ; russian: Подолье, Podolye; ro, Podolia; pl, Podole; german: Podolien; be, Падолле, Padollie; lt, Podolė), is a historic region in Eastern Europe, located in the west-central ...

, and then tried

In law, a trial is a coming together of parties to a dispute, to present information (in the form of evidence) in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to adjudicate claims or disputes. One form of tribunal is a court. The tribunal, w ...

to expand into Ukrainian territory on the right bank of the Dnieper River, but were held back by the Russians. The Treaty of Bakhchisarai made the river Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine and B ...

the boundary between the Ottoman Empire and Russia.

In 1683, a new war broke out between Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

and the Ottomans, with a large Ottoman army advancing towards Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

. The Ottoman siege was broken in the Battle of Vienna

The Battle of Vienna; pl, odsiecz wiedeńska, lit=Relief of Vienna or ''bitwa pod Wiedniem''; ota, Beç Ḳalʿası Muḥāṣarası, lit=siege of Beç; tr, İkinci Viyana Kuşatması, lit=second siege of Vienna took place at Kahlenberg Mou ...

by the King of Poland, Jan Sobieski

John III Sobieski ( pl, Jan III Sobieski; lt, Jonas III Sobieskis; la, Ioannes III Sobiscius; 17 August 1629 – 17 June 1696) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1674 until his death in 1696.

Born into Polish nobility, Sobie ...

. As a result, an anti-Ottoman Holy League

Commencing in 1332 the numerous Holy Leagues were a new manifestation of the Crusading movement in the form of temporary alliances between interested Christian powers. Successful campaigns included the capture of Smyrna in 1344, at the Battle of ...

was formed at Linz

Linz ( , ; cs, Linec) is the capital of Upper Austria and third-largest city in Austria. In the north of the country, it is on the Danube south of the Czech border. In 2018, the population was 204,846.

In 2009, it was a European Capital of ...

on 5 March 1684 between Emperor Leopold I, Sobieski, and the Doge of Venice

The Doge of Venice ( ; vec, Doxe de Venexia ; it, Doge di Venezia ; all derived from Latin ', "military leader"), sometimes translated as Duke (compare the Italian '), was the chief magistrate and leader of the Republic of Venice between 726 a ...

, Marcantonio Giustinian

Marcantonio Giustinian (March 2, 1619 – March 23, 1688) was the 107th Doge of Venice, reigning from his election on January 26, 1684 until his death. Giustiniani was the quintessential Doge of the Republic of Venice, taking little interest in ...

. Over the next few years, the Austrians recovered Hungary from Ottoman control, and even captured Belgrade

Belgrade ( , ;, ; Names of European cities in different languages: B, names in other languages) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers a ...

in 1688 and reached as far as Niš

Niš (; sr-Cyrl, Ниш, ; names in other languages) is the third largest city in Serbia and the administrative center of the Nišava District. It is located in southern part of Serbia. , the city proper has a population of 183,164, while ...

and Vidin in the next year. The Austrians were now overextended, as well as being embroiled in the Nine Years' War

The Nine Years' War (1688–1697), often called the War of the Grand Alliance or the War of the League of Augsburg, was a conflict between France and a European coalition which mainly included the Holy Roman Empire (led by the Habsburg monarch ...

(1688–97) against France. The Ottomans, under another Köprülü Grand Vizier, Fazıl Mustafa Pasha, regained the initiative and pushed the Austrians back, recovering Niš and Vidin in 1690 and launching raids across the Danube. After 1696, the tide turned again, with the capture

Capture may refer to:

*Asteroid capture, a phenomenon in which an asteroid enters a stable orbit around another body

*Capture, a software for lighting design, documentation and visualisation

*"Capture" a song by Simon Townshend

*Capture (band), an ...

of Azov by the Russians in 1696 followed by a disastrous defeat at the hands of Eugene of Savoy at the battle of Zenta

The Battle of Zenta, also known as the Battle of Senta, was fought on 11 September 1697, near Zenta, Ottoman Empire (modern-day Senta, Serbia), between Ottoman and Holy League armies during the Great Turkish War. The battle was the most decis ...

in September 1697. In its aftermath, negotiations began between the warring parties, leading to the signing of the Treaty of Karlowitz

The Treaty of Karlowitz was signed in Karlowitz, Military Frontier of Archduchy of Austria (present-day Sremski Karlovci, Serbia), on 26 January 1699, concluding the Great Turkish War of 1683–1697 in which the Ottoman Empire was defeated by the ...

in 1699.

Venice prepares for war

The Austrians and Poles considered Venetian participation in the war as a useful adjunct to the main operations in Central Europe, as its navy could impede the Ottomans from concentrating their forces by sea and force them to divert forces away from their own fronts. On the Venetian side, the debate in theSenate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

about joining the war was heated, but in the end the war party prevailed, judging the moment as an excellent and unique opportunity for a ''revanche''. As a result, when news arrived in Venice on 25 April 1684 of the signing of the Holy League, for the first and only time in the Ottoman–Venetian Wars, the Most Serene Republic declared war on the Ottomans, rather than the other way around.

Nevertheless, at the outbreak of the war, the military forces of the Republic were meagre. The long Cretan War had exhausted Venetian resources, and Venetian power was in decline in Italy as well as the Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to t ...

. While the Venetian navy was a well-maintained force, comprising ten galleass

Galleasses were military ships developed from large merchant galleys, and intended to combine galley speed with the sea-worthiness and artillery of a galleon. While perhaps never quite matching up to their full expectations, galleasses neverthel ...

es, thirty men-of-war

The man-of-war (also man-o'-war, or simply man) was a Royal Navy expression for a powerful warship or frigate from the 16th to the 19th century. Although the term never acquired a specific meaning, it was usually reserved for a ship armed wi ...

, and thirty galley

A galley is a type of ship that is propelled mainly by oars. The galley is characterized by its long, slender hull, shallow draft, and low freeboard (clearance between sea and gunwale). Virtually all types of galleys had sails that could be used ...

s, as well as auxiliary vessels, the army comprised 8,000 not very disciplined regular troops. They were complemented by a numerous and well-equipped militia, but the latter could not be used outside Italy. Revenue was also scarce, at little more than two million sequins a year. According to the reports of the English ambassador to the Porte

Porte may refer to:

*Sublime Porte, the central government of the Ottoman empire

*Porte, Piedmont, a municipality in the Piedmont region of Italy

*John Cyril Porte, British/Irish aviator

*Richie Porte, Australian professional cyclist who competes ...

, Lord Chandos, the Ottomans' position was even worse: on land they were reeling from a succession of defeats, so that the Sultan had to double the pay of his troops and resort to forcible conscription. At the same time, the Ottoman navy was described by Chandos as being in a sore state, scarcely able to outfit ten men-of-war for operations. This left the Venetians with an uncontested supremacy at sea, while the Ottomans resorted to using light and fast galleys to evade the Venetian fleet and resupply their fortresses along the coasts. In view of its financial weakness, the Republic determined to bring the war to Ottoman territory, where they could conscript and extract tribute at will, before the Ottomans could recover from the shock and losses incurred at Vienna and reinforce their positions. In addition, Venice received considerable subsidies from Pope Innocent XI

Pope Innocent XI ( la, Innocentius XI; it, Innocenzo XI; 16 May 1611 – 12 August 1689), born Benedetto Odescalchi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 21 September 1676 to his death on August 12, 1689.

Poli ...

, who played a leading role in forming the Holy League and "nearly impoverished the Curia in raising subsidies for the allies".

In January 1684, Morosini, having a distinguished record and great experience of operations in Greece, was chosen as the commander-in-chief of the expeditionary force. Venice increased her forces by enrolling large numbers of mercenaries from Italy and the German states, and raised funds by selling state offices and titles of nobility. Financial and military aid in men and ships was secured from the Knights of Malta

The Sovereign Military Order of Malta (SMOM), officially the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and of Malta ( it, Sovrano Militare Ordine Ospedaliero di San Giovanni di Gerusalemme, di Rodi e di Malta; ...

, the Duchy of Savoy

The Duchy of Savoy ( it, Ducato di Savoia; french: Duché de Savoie) was a country in Western Europe that existed from 1416.

It was created when Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, raised the County of Savoy into a duchy for Amadeus VIII. The duc ...

, the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

and the Knights of St. Stephen

The Order of Saint Stephen (Official: Sacro Militare Ordine di Santo Stefano Papa e Martire, "Holy Military Order of St. Stephen Pope and Martyr") is a Roman Catholic Tuscan dynastic military order founded in 1561. The order was created by Co ...

of Tuscany

Tuscany ( ; it, Toscana ) is a Regions of Italy, region in central Italy with an area of about and a population of about 3.8 million inhabitants. The regional capital is Florence (''Firenze'').

Tuscany is known for its landscapes, history, art ...

, and experienced Austrian officers were seconded to the Venetian army. In the Venetian-ruled Ionian Islands, similar measures were undertaken; over 2,000 soldiers, apart from sailors and rowers for the fleet, were recruited. On 10 June 1684, Morosini set sail with a fleet of three galleys, two galleass

Galleasses were military ships developed from large merchant galleys, and intended to combine galley speed with the sea-worthiness and artillery of a galleon. While perhaps never quite matching up to their full expectations, galleasses neverthel ...

es, and a few auxiliary vessels. On the way to Corfu

Corfu (, ) or Kerkyra ( el, Κέρκυρα, Kérkyra, , ; ; la, Corcyra.) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands, and, including its small satellite islands, forms the margin of the northwestern frontier of Greece. The isl ...

he was joined by further four Venetian, five Papal, seven Maltese, and four Tuscan galleys. At Corfu they were united with the local naval and military forces, as well as forces raised by noble Greek families of the Ionian Islands.

Venetian offensive

Operations in western Greece (1684)

The first target of the Venetian fleet was the island of Lefkada (Santa Maura). Morosini's political rival, Girolamo Corner, tried to preempt him and seize the Santa Maura fortress (which he believed to be lightly defended) before the arrival of the fleet from Venice. With a small force he sailed from Corfu to the island, but finding the fortress strongly garrisoned, he turned back. As a result of this misadventure, Corner was sidelined for the first year of the war, during which he served as '' provveditore generale'' of the Ionian Islands, before he was appointed to command in

The first target of the Venetian fleet was the island of Lefkada (Santa Maura). Morosini's political rival, Girolamo Corner, tried to preempt him and seize the Santa Maura fortress (which he believed to be lightly defended) before the arrival of the fleet from Venice. With a small force he sailed from Corfu to the island, but finding the fortress strongly garrisoned, he turned back. As a result of this misadventure, Corner was sidelined for the first year of the war, during which he served as '' provveditore generale'' of the Ionian Islands, before he was appointed to command in Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

in late 1685. On 18 July 1684, Morosini left Corfu, and arrived at Santa Maura two days later. After a siege of 16 days, the fortress capitulated on 6 August 1684.

The Venetians then crossed onto the mainland region of

The Venetians then crossed onto the mainland region of Acarnania

Acarnania ( el, Ἀκαρνανία) is a region of west-central Greece that lies along the Ionian Sea, west of Aetolia, with the Achelous River for a boundary, and north of the gulf of Calydon, which is the entrance to the Gulf of Corinth. Today i ...

. The offshore island of Petalas was occupied on 10 August by Count Niccolo di Strassoldo and Angelo Delladecima. Reinforced with volunteers, mostly from Cephalonia

Kefalonia or Cephalonia ( el, Κεφαλονιά), formerly also known as Kefallinia or Kephallenia (), is the largest of the Ionian Islands in western Greece and the 6th largest island in Greece after Crete, Euboea, Lesbos, Rhodes and Chios. It i ...

, the Venetians then captured the towns of Aitoliko and Missolonghi

Missolonghi or Messolonghi ( el, Μεσολόγγι, ) is a municipality of 34,416 people (according to the 2011 census) in western Greece. The town is the capital of Aetolia-Acarnania regional unit, and the seat of the municipality of Iera Polis ...

. Arvanite (Orthodox Albanian) leaders from across Epirus, from Himarra and Souli

Souli ( el, Σούλι) is a municipality in Epirus, northwestern Greece. The seat of the municipality is the town of Paramythia.

Name and History

The origin of the name Souli is uncertain. In the earliest historical text about Souli, written ...

and the armatoloi captains of Acarnania and Agrafa

Agrafa ( el, Άγραφα, ) is a mountainous region in Evrytania and Karditsa regional units in mainland Greece, consisting mainly of small villages. It is the southernmost part of the Pindus range. There is also a municipality with the same n ...

, had contacted the Venetians with proposals for a common cause; with the Venetian advance, a general rising occurred in the area of Valtos and Xiromero. Muslim villages were attacked, looted, and torched, and Ottoman rule collapsed across western Continental Greece

Continental Greece ( el, Στερεά Ελλάδα, Stereá Elláda; formerly , ''Chérsos Ellás''), colloquially known as Roúmeli (Ρούμελη), is a traditional geographic regions of Greece, geographic region of Greece. In English, the a ...

. By the end of the month the Ottomans only held on to the coastal fortresses of Preveza

Preveza ( el, Πρέβεζα, ) is a city in the region of Epirus, northwestern Greece, located on the northern peninsula at the mouth of the Ambracian Gulf. It is the capital of the regional unit of Preveza, which is part of the region of Epiru ...

and Vonitsa. The Venetian fleet launched several raids along the coast of Epirus up to Igoumenitsa and even on the north-western coast of the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic regions of Greece, geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmu ...

, near Patras

)

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 =

, demographics1_info2 =

, timezone1 = EET

, utc_offset1 = +2

, ...

, before launching a concerted effort to capture the castle

A castle is a type of fortified structure built during the Middle Ages predominantly by the nobility or royalty and by military orders. Scholars debate the scope of the word ''castle'', but usually consider it to be the private fortified r ...

of Preveza on 21 September. The castle surrendered after eight days, and Vonitsa was captured by Delladecima's men a few days later. At the end of autumn, Morosini appointed Delladecima as military governor of the region stretching from the Gulf of Ambracia to the river Acheloos. Already in this early part of the war, the Venetians began suffering great casualties on account of disease; Count Strasoldo was one of them. These early successes were important for the Venetians because they secured their communications with Venice, denied to the Ottomans the possibility of moving troops through the area, and provided a springboard for possible future conquests on the Greek mainland.

At the same time, Venice set about providing Morosini with more troops, and concluded treaties with the rulers of Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a landlocked state of ...

and Hannover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German States of Germany, state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the List of cities in Germany by population, 13th-largest city in Germa ...

, who were to provide contingents of 2,400 men each as mercenaries. After the treaty was signed in December 1684, 2,500 Hannoverians joined Morosini in June 1685, while 3,300 Saxons arrived a few months later. In spring and early June 1685, the Venetian forces gathered at Corfu, Preveza, and Dragamesto: 37 galleys (17 of which Tuscan, Papal, or Maltese), 5 galleasses, 19 sailing ships, and 12 galleot

A galiot, galliot or galiote, was a small galley boat propelled by sail or oars. There are three different types of naval galiots that sailed on different seas.

A ''galiote'' was a type of French flat-bottom river boat or barge and also a flat- ...

s, 6,400 Venetian troops (2,400 Hannoverians and 1,000 Dalmatians), 1,000 Maltese troops, 300 Florentines, and 400 Papal soldiers. To them were added a few hundred conscripted and volunteer Greeks from the Ionian Islands and the mainland.

Conquest of the Morea (1685–87)

Coron and Mani (1685)

Having secured his rear during the previous year, Morosini set his sights upon the Peloponnese, where the Greeks had begun showing signs of revolt. Already in spring 1684, the Ottoman authorities had arrested and executed theMetropolitan of Corinth

The Metropolis of Corinth, Sicyon, Zemenon, Tarsos and Polyphengos ( el, Ιερά Μητρόπολις Κορίνθου, Σικυώνος, Ζεμενού, Ταρσού και Πολυφέγγους) is a metropolitan see of the Church of Greece in ...

, Zacharias, for participating in revolutionary circles. At the same time, insurrectionist movements began among the Maniots, who resented the loss of privileges and autonomy, including the establishment of Ottoman garrisons in the fortresses of Zarnata, Kelefa

Kelefa ( el, Κελεφά) is a castle and village in Mani, Laconia, Greece. It is part of the municipal unit of Oitylo.

History

The castle of Kelefa is located about half-way between the current village of Kelefa and the Bay of Oitylo. It was ...

, and Passavas Las ( grc, Λᾶς and ἡ Λᾶς), or Laas (Λάας), or La (Λᾶ), was one of the most ancient towns of Lakedaimonia (eventually called the Mani Peninsula), located on the western coast of the Laconian Gulf. It is the only town on the coast men ...

, that they had suffered due to their collaboration with the Venetians in the Cretan War. In early autumn, an assembly under the presidency of the local bishop, Joachim, decided to approach the Venetians for aid, and on 20 October, a ten-man embassy arrived at Zakynthos to treat with Morosini. The discussions dragged on until February 1685, when at last the Venetian commander-in-chief resolved to supply the Maniots with quantities of guns and ammunition. In the meantime, the Ottoman authorities had not been idle. Already in the preceding months they had reinforced their troops in Laconia

Laconia or Lakonia ( el, Λακωνία, , ) is a historical and administrative region of Greece located on the southeastern part of the Peloponnese peninsula. Its administrative capital is Sparta. The word ''laconic''—to speak in a blunt, c ...

, and in February the new ''serasker

''Serasker'', or ''seraskier'' ( ota, سرعسكر; ), is a title formerly used in the Ottoman Empire for a vizier who commanded an army.

Following the suppression of the Janissaries in 1826, Sultan Mahmud II transferred the functions of the ...

'' of the Morea, Ismail Pasha, invaded the Mani peninsula

The Mani Peninsula ( el, Μάνη, Mánē), also long known by its medieval name Maina or Maïna (Μαΐνη), is a geographical and cultural region in Southern Greece that is home to the Maniots (Mανιάτες, ''Maniátes'' in Greek), who cla ...

with 10,000 men. The Maniots resisted, but their renewed pleas for aid to the Venetians in early March resulted only in the dispatch of four ships with ammunition under Daniel Dolfin. As a result, the Maniots were forced to submit, and gave up their children as hostages to the ''serasker''.

At long last, on 21 June the Venetian fleet set sail for the Peloponnese, and on 25 June, the Venetian army, over 8,000 men strong, landed outside the former Venetian fort of Coron ( Koroni) and laid siege to it. The Maniots remained passive at first, and for a time the position of the besieging Christian troops was threatened by the troops led by the governor of Nauplia, Halil Pasha, and the fresh reinforcements disembarked by the Ottoman fleet under the Kapudan Pasha, both at Nauplia and at Kalamata. The Ottoman efforts to break the siege were defeated, and on 11 August, the fortress surrendered. Despite a pledge of safe passage, the garrison was massacred due to suspicion of treachery.

In the final stage of the siege, 230 Maniots under the Zakynthian noble Pavlos Makris

Pavlos () or Pávlos () is a masculine given name. It is a Greek form of Paul. It may refer to:

*Pavlos Bakoyannis (1935–1989), a liberal Greek politician

*Pavlos Carrer (1829–1896), a Greek composer

*Pavlos, Crown Prince of Greece (bo ...

had taken part, and soon the area rose up in revolt again, encouraged by Morosini's presence at Coron. The Venetian commander now targeted Kalamata, where the Kapudan Pasha had landed 6,000 infantry and 2,000 sipahi cavalry, and established an entrenched camp. On 10 September, the Venetians and Maniots obtained the surrender of the fortress of Zarnata, its garrison of 600 being allowed safe passage to Kalamata, but its commander retiring to Venice and a rich pension. After the Kapudan Pasha rejected an offer of Morisini to disperse his army, the Venetian army, reinforced by 3,300 Saxons and under the command of general Hannibal von Degenfeld

Hannibal (; xpu, 𐤇𐤍𐤁𐤏𐤋, ''Ḥannibaʿl''; 247 – between 183 and 181 BC) was a Carthaginian general and statesman who commanded the forces of Carthage in their battle against the Roman Republic during the Second Puni ...

, attacked the Ottoman camp and defeated them on 14 September. Kalamata surrendered without a fight and its castle was razed, and by the end of September the remaining Ottoman garrisons in Kelafa and Passavas had capitulated and evacuated Mani. Passavas was razed, but the Venetians in turn installed their own garrisons in Kelafa and Zarnata, as well as the offshore island of Marathonisi, to keep an eye on the unruly Maniots, before returning to the Ionian Islands to winter.

The campaigning season was concluded with the capture and razing of Igoumenitsa on 11 November. Once again, disease took its toll among the Venetian army in its winter quarters. Losses were particularly heavy among the German contingents, which complained about the negligence shown to them by the Venetian authorities, and the often spoiled food they were sent: the Hannoverians alone lost 736 men to disease in the period from April 1685 to January 1686, as opposed to 256 in battle.

Navarino, Modon, and Nauplia (1686)

In the next year, the Ottomans seized the initiative by attacking Kelefa in early March, forcing Morosini to hasten his departure from the Ionian Islands. The Ottomans raised the siege and withdrew at the arrival of a Venetian fleet under Venieri, and on 30 March, Morosini began landing his troops in the

In the next year, the Ottomans seized the initiative by attacking Kelefa in early March, forcing Morosini to hasten his departure from the Ionian Islands. The Ottomans raised the siege and withdrew at the arrival of a Venetian fleet under Venieri, and on 30 March, Morosini began landing his troops in the Messenian Gulf

The Messenian Gulf (, ''Messiniakós Kólpos'') is a sea that is part of the Ionian Sea. The gulf is circumscribed by the southern coasts of Messenia and the southwestern coast of the Mani peninsula in Laconia. Its bounds are Venetiko Island t ...

. The Venetian forces were slow to assemble, and Morosini had to await the arrival of reinforcements in the form of 13 galleys from the Papal States and the Grand Duchy of Tuscany

The Grand Duchy of Tuscany ( it, Granducato di Toscana; la, Magnus Ducatus Etruriae) was an Italian monarchy that existed, with interruptions, from 1569 to 1859, replacing the Republic of Florence. The grand duchy's capital was Florence. In th ...

, as well as further mercenaries, which raised his army to some 10,000 foot and 1,000 horse, before commencing his advance in late May. Following a recommendation by Morosini himself, the veteran Swedish marshal Otto Wilhelm Königsmarck was appointed head of the land forces, while Morosini retained command of the fleet. Königsmarck also requested, and was granted, that the Venetians hire several other experienced officers, particularly experts in siege warfare.

On 2 June, Königsmarck landed his army at Pylos

Pylos (, ; el, Πύλος), historically also known as Navarino, is a town and a former municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part of the municipality Pylos-Nestoras, of which it is th ...

, where the Old Navarino castle surrendered the next day, after the aqueduct providing its water supply was cut. Its garrison, comprising black Africans, was transported to Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

. The more modern fortress of New Navarino was also besieged and surrendered on 14 June, after one of its magazines exploded, killing its commander, Sefer Pasa, and many of his senior officers. Its garrison, 1,500 soldiers and a like number of civilian dependents, were transported to Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis may refer to:

Cities and other geographic units Greece

*Tripoli, Greece, the capital of Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in ...

. Attempts by the Ottoman ''serasker'' to relieve the fortress or impede the Venetians ended in a defeat in battle, after which the Venetians moved to blockade and besiege another former Venetian stronghold, Modon ( Methoni), on 22 June. Although well fortified, supplied, and equipped with a hundred guns and a thousand-strong garrison, the fort surrendered on 7 July, after sustained bombardment and successive Venetian assaults. Its population of 4,000 was likewise transported to Tripoli. At the same time, a Venetian squadron and Dalmatian troops captured the fort of Arkadia (modern Kyparissia

Kyparissia ( el, Κυπαρισσία) is a town and a former municipality in northwestern Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Trifylia, of which it is the seat and a municipal unit. ...

) further north.

The Venetians then, in a lightning move, retired their field army from Messenia and landed it at Tolo between 30 July and 4 August, within striking distance of the capital of the Peloponnese, Nauplia. On the very first day, Königsmarck led his troops to capture the hill of Palamidi, then only poorly fortified, which overlooked the town. The commander of the city, Mustapha Pasha, moved the civilians to the citadel of

The Venetians then, in a lightning move, retired their field army from Messenia and landed it at Tolo between 30 July and 4 August, within striking distance of the capital of the Peloponnese, Nauplia. On the very first day, Königsmarck led his troops to capture the hill of Palamidi, then only poorly fortified, which overlooked the town. The commander of the city, Mustapha Pasha, moved the civilians to the citadel of Akronauplia

The Acronauplia ( ell, Ακροναυπλία, translit=Akronafplia, tr, Iç Kale, "Inner Castle") is the oldest part of the city of Nafplion in Greece. Until the thirteenth century, it was a town on its own. The arrival of the Venetians and th ...

, and sent urgent messages to the ''serasker'' Ismail Pasha for aid; before the Venetians managed to complete their disembarkation, Ismail Pasha arrived at Argos

Argos most often refers to:

* Argos, Peloponnese, a city in Argolis, Greece

** Ancient Argos, the ancient city

* Argos (retailer), a catalogue retailer operating in the United Kingdom and Ireland

Argos or ARGOS may also refer to:

Businesses

* ...

with 4,000 horse and 3,000 foot, and tried to assist the besieged garrison. The Venetians launched an assault against the relief army on 7 August that succeeded in taking Argos and forcing the pasha to retreat to Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part o ...

, but for two weeks, from 16 August, Königsmarck's forces were forced to continuously repulse attacks from Ismail Pasha's forces, fight off the sorties of the besieged garrison, and cope with a new outbreak of the plague—the Hannoverians counted 1,200 out of 2,750 men as sick and wounded. On 29 August Ismail Pasha launched a large-scale attack against the Venetian camp, but was heavily defeated after Morosini landed 2,000 men from the fleet on his flank. Mustapha Pasha surrendered the city on the same day, and on the next day, Morosini staged a triumphal entry in the city. The city's seven thousand Muslims, including the garrison, were transported to Tenedos

Tenedos (, ''Tenedhos'', ), or Bozcaada in Turkish language, Turkish, is an island of Turkey in the northeastern part of the Aegean Sea. Administratively, the island constitutes the Bozcaada, Çanakkale, Bozcaada district of Çanakkale Provinc ...

. News of this major victory was greeted in Venice with joy and celebration. Nauplia became the Venetians' major base, while Ismail Pasha withdrew to Vostitsa

Aigio, also written as ''Aeghion, Aegion, Aegio, Egio'' ( el, Αίγιο, Aígio, ; la, Aegium), is a town and a former municipality in Achaea, West Greece, on the Peloponnese. Since the 2011 local government reform, it is part of the municipalit ...

in the northern Peloponnese after strengthening the garrisons at Corinth, which controlled the passage to Central Greece

Continental Greece ( el, Στερεά Ελλάδα, Stereá Elláda; formerly , ''Chérsos Ellás''), colloquially known as Roúmeli (Ρούμελη), is a traditional geographic region of Greece. In English, the area is usually called Central ...

. The Ottoman forces elsewhere fell into disarray when false rumours circulated that the Sultan had ordered the Peloponnese evacuated; thus at Karytaina Ottoman troops killed their commander and dispersed.

The Ottoman fleet, under the Kapudan Pasha, which had arrived in the Saronic Gulf

The Saronic Gulf (Greek: Σαρωνικός κόλπος, ''Saronikós kólpos'') or Gulf of Aegina in Greece is formed between the peninsulas of Attica and Argolis and forms part of the Aegean Sea. It defines the eastern side of the isthmus of Co ...

to reinforce the Ottoman positions in Corinth, was forced by these news to turn back to its base in the Dardanelles. In early October, Morosini led his own ships in a vain search for the Ottoman fleet; as part of this expedition, Morosini landed at the Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; el, Πειραιάς ; grc, Πειραιεύς ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens' city centre, along the east coast of the Saronic ...

, where he was met by the Metropolitan of Athens

The Archbishopric of Athens ( el, Ιερά Αρχιεπισκοπή Αθηνών) is a Greek Orthodox archiepiscopal see based in the city of Athens, Greece. It is the senior see of Greece, and the seat of the autocephalous Church of Greece. Its ...

, Jacob, and notables of the town, who offered him 9,000 reales as tribute. After visiting Salamis, Aegina

Aegina (; el, Αίγινα, ''Aígina'' ; grc, Αἴγῑνα) is one of the Saronic Islands of Greece in the Saronic Gulf, from Athens. Tradition derives the name from Aegina (mythology), Aegina, the mother of the hero Aeacus, who was born ...

, and Hydra

Hydra generally refers to:

* Lernaean Hydra, a many-headed serpent in Greek mythology

* ''Hydra'' (genus), a genus of simple freshwater animals belonging to the phylum Cnidaria

Hydra or The Hydra may also refer to:

Astronomy

* Hydra (constel ...

, Morosini returned with the fleet to the bay of Nauplia on 16 October. At about the same time, the dissatisfaction among the German mercenaries, due to their losses to disease and the perceived neglect in the sharing of spoils, reached its peak, and many, including the entire Saxon contingent, returned home. Nevertheless, Venice was able to make up the losses by a new recruitment drive in Hesse

Hesse (, , ) or Hessia (, ; german: Hessen ), officially the State of Hessen (german: links=no, Land Hessen), is a States of Germany, state in Germany. Its capital city is Wiesbaden, and the largest urban area is Frankfurt. Two other major histor ...

, Württemberg

Württemberg ( ; ) is a historical German territory roughly corresponding to the cultural and linguistic region of Swabia. The main town of the region is Stuttgart.

Together with Baden and Hohenzollern, two other historical territories, Würt ...

, and Hannover. Due to the imminent outbreak of the Nine Years' War and the general demand for mercenaries, most of the new recruits were not veteran soldiers; the recruiters were even forced to recruit French deserters, and over 200 men deserted in turn during the march to Venice. Once again, the need to await reinforcement delayed the start of Venetian operations in 1687 until July.

Patras and the completion of the conquest (1687)

In the meantime, the Ottomans had formed a strong entrenched camp at

In the meantime, the Ottomans had formed a strong entrenched camp at Patras

)

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 =

, demographics1_info2 =

, timezone1 = EET

, utc_offset1 = +2

, ...

, with 10,000 men under Mehmed Pasha. As the Ottomans were resupplied from across the Corinthian Gulf

The Gulf of Corinth or the Corinthian Gulf ( el, Κορινθιακός Kόλπος, ''Korinthiakόs Kόlpos'', ) is a deep inlet of the Ionian Sea, separating the Peloponnese from western mainland Greece. It is bounded in the east by the Isth ...

by small vessels, Morosini's first step was to institute a naval blockade of the northern Peloponnesian coast. Then, on 22 July, Morosini landed the first of his 14,000 troops west of Patras. Two days later, after the bulk of the Venetian forces had landed, Königsmarck led his army to attack the Ottoman camp, choosing a weak spot in its defences. The Ottomans fought valiantly, but by the end of the day, they were forced to retreat, leaving behind over 2,000 dead and wounded, 160 guns and many supplies, 14 ships, and their commander's own flag. The defeat demoralized the Ottoman garrison of Patras Castle, which abandoned it and fled to the fortress of Rio

Rio or Río is the Portuguese, Spanish, Italian, and Maltese word for "river". When spoken on its own, the word often means Rio de Janeiro, a major city in Brazil.

Rio or Río may also refer to:

Geography Brazil

* Rio de Janeiro

* Rio do Sul, a ...

(the "Castle of the Morea

The Rio Castle ( el, κάστρο του Ρίου), historically known as the Castle of the Morea ( it, Castello de Morea) in opposition to its counterpart, the Castle of Rumelia at Antirrio, is located at the north tip of the Rio peninsula in ...

"). The next day, with Venetian ships patrolling off the shore, Mehmed and his troops abandoned Rio as well and fled east. The retreat quickly degenerated into a panic, which was often joined by the Greek villagers, and which spread on the same day to the mainland across the Corinthian Gulf as well. Thus within a single day, 25 July, the Venetians were able to capture, without opposition, the twin forts of Rio and Antirrio (the "Little Dardanelles") and the castle of Naupaktos

Nafpaktos ( el, Ναύπακτος) is a town and a former municipality in Aetolia-Acarnania, West Greece, situated on a bay on the north coast of the Gulf of Corinth, west of the mouth of the river Mornos.

It is named for Naupaktos (, Latinize ...

(Lepanto). The Ottomans halted their retreat only at Thebes, where Mehmed Pasha set about regrouping his forces.

The Venetians followed up this success with the reduction of the last Ottoman bastions in the Peloponnese: Chlemoutsi surrendered to Angelo De Negri from Zakynthos on 27 July, while Königsmarck marched east towards Corinth. The Ottoman garrison abandoned the Acrocorinth at his approach after torching the town, which was captured by the Venetians on 7 August. Morosini now gave orders for the preparation of a campaign across the Isthmus of Corinth

The Isthmus of Corinth (Greek: Ισθμός της Κορίνθου) is the narrow land bridge which connects the Peloponnese peninsula with the rest of the mainland of Greece, near the city of Corinth. The word "isthmus" comes from the Ancien ...

towards Athens, before going to Mystras

Mystras or Mistras ( el, Μυστρᾶς/Μιστρᾶς), also known in the ''Chronicle of the Morea'' as Myzithras (Μυζηθρᾶς), is a fortified town and a former municipality in Laconia, Peloponnese, Greece. Situated on Mt. Taygetus, nea ...

, where he persuaded the Ottoman garrison to surrender, and the Maniots occupied Karytaina, abandoned by its Ottoman garrison. The Peloponnese was under complete Venetian control, and only the fort of Monemvasia (Malvasia) in the southeast, which was placed under siege on 3 September, continued to resist, holding out until 1690. These new successes caused great joy in Venice, and honours were heaped on Morosini and his officers. Morosini received the victory title

A victory title is an honorific title adopted by a successful military commander to commemorate his defeat of an enemy nation. The practice is first known in Ancient Rome and is still most commonly associated with the Romans, but it was also adop ...

"''Peloponnesiacus''", and a bronze bust of his was displayed in the Hall of the Great Council of Venice

The Great Council or Major Council ( it, Maggior Consiglio; vec, Mazor Consegio) was a political organ of the Republic of Venice between 1172 and 1797. It was the chief political assembly, responsible for electing many of the other political off ...

, something never before done for a living citizen. Königsmarck was rewarded with 6,000 ducat

The ducat () coin was used as a trade coin in Europe from the later Middle Ages from the 13th to 19th centuries. Its most familiar version, the gold ducat or sequin containing around of 98.6% fine gold, originated in Venice in 1284 and gained wi ...

s in a gold basin and a pay rise to 24,000 ducats a year, Maximilian William of Brunswick-Lüneburg, who commanded the Hannoverian troops, received a jewelled sword valued at 4,000 ducats, and similar gifts were made to many officers in the army.

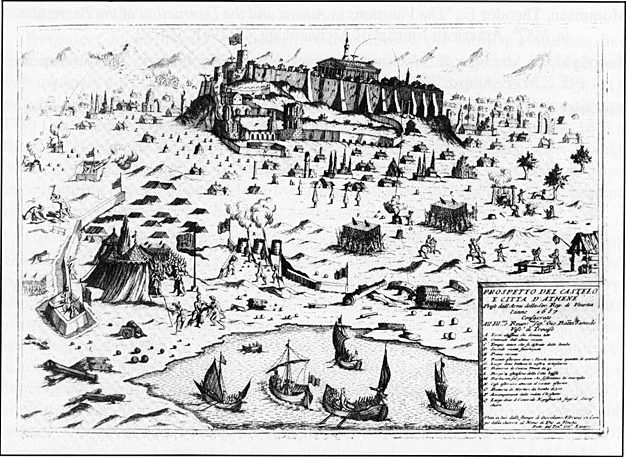

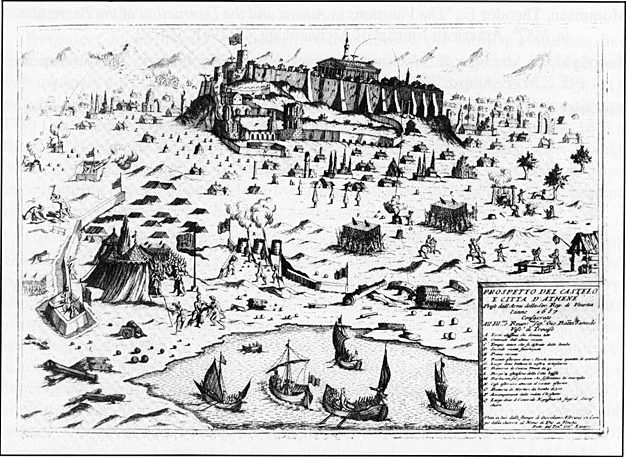

Occupation of Athens (1687–88)

The Venetian position in the Peloponnese could not be secure as long as the Ottomans held onto eastern Central Greece, where Thebes and Negroponte ( Chalkis) were significant military strongholds. Thus, on 21 September 1687, Königsmarck's army, 10,750 men strong, landed at

The Venetian position in the Peloponnese could not be secure as long as the Ottomans held onto eastern Central Greece, where Thebes and Negroponte ( Chalkis) were significant military strongholds. Thus, on 21 September 1687, Königsmarck's army, 10,750 men strong, landed at Eleusis

Elefsina ( el, Ελευσίνα ''Elefsina''), or Eleusis (; Ancient Greek: ''Eleusis'') is a suburban city and Communities and Municipalities of Greece, municipality in the West Attica regional unit of Greece. It is situated about northwest ...

, while the Venetian fleet entered Piraeus. The Turks quickly evacuated the town of Athens, but the garrison and much of the population withdrew to the ancient Acropolis of Athens, determined to hold out until reinforcements arrived from Thebes. The Venetian army set up cannon and mortar batteries on the Pnyx

The Pnyx (; grc, Πνύξ ; ell, Πνύκα, ''Pnyka'') is a hill in central Athens, the capital of Greece. Beginning as early as 507 BC (Fifth-century Athens), the Athenians gathered on the Pnyx to host their popular assemblies, thus making t ...

and other heights around the city and began a siege of the Acropolis, which would last six days (23–29 September) and would cause much destruction to the ancient monuments. The Ottomans first demolished the Temple of Athena Nike

A temple (from the Latin ) is a building reserved for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. Religions which erect temples include Christianity (whose temples are typically called churches), Hinduism (whose temples ...

to erect a cannon battery, and on 25 September, a Venetian cannonball exploded a powder magazine in the Propylaea

In ancient Greek architecture, a propylaea, propylea or propylaia (; Greek: προπύλαια) is a monumental gateway. They are seen as a partition, specifically for separating the secular and religious pieces of a city. The prototypical Gree ...

. The most important damage caused was the destruction of the Parthenon. The Turks used the temple for ammunition storage, and when, on the evening of 26 September 1687, a mortar shell hit the building, the resulting explosion killed 300 people and led to the complete destruction of the temple's roof and most of the walls. Despite the enormous destruction caused by the "miraculous shot", as Morosini called it, the Turks continued to defend the fort until a relief attempt from the Ottoman army from Thebes was repulsed by Königsmarck on 28 September. The garrison then capitulated, on condition of being transported to Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

.

Despite the fall of Athens, Morosini's position was not secure. The Ottomans were amassing an army at Thebes, and their 2,000-strong cavalry effectively controlled

Despite the fall of Athens, Morosini's position was not secure. The Ottomans were amassing an army at Thebes, and their 2,000-strong cavalry effectively controlled Attica

Attica ( el, Αττική, Ancient Greek ''Attikḗ'' or , or ), or the Attic Peninsula, is a historical region that encompasses the city of Athens, the capital of Greece and its countryside. It is a peninsula projecting into the Aegean Se ...

, limiting the Venetians to the environs of Athens, so that the Venetians had to establish forts to secure the road linking Athens to Piraeus. On 26 December, the 1,400-strong remnant of the Hannoverian contingent departed, and a new outbreak of the plague during the winter further weakened the Venetian forces. The Venetians managed to recruit 500 Arvanites from the rural population of Attica as soldiers, but no other Greeks were willing to join the Venetian army. In a council on 31 December, it was decided to abandon Athens and focus on other projects, such as the conquest of Negroponte. A camp was fortified at the Munychia to cover the evacuation, and it was suggested, but not agreed on, that the walls of the Acropolis should be razed. As the Venetian preparations to leave became evident, many Athenians chose to leave, fearing Ottoman reprisals: 622 families, some 4,000–5,000 people, were evacuated by Venetian ships and settled as colonists in Argolis, Corinthia, Patras, and Aegean islands. Morosini decided to at least take back a few ancient monuments as spoils, but on 19 March the statues of Poseidon

Poseidon (; grc-gre, Ποσειδῶν) was one of the Twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and myth, god of the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 In pre-Olympian Bronze Age Greece, he was venerated as a ch ...

and the chariot of Nike fell down and smashed into pieces as they were being removed from the western pediment

Pediments are gables, usually of a triangular shape.

Pediments are placed above the horizontal structure of the lintel, or entablature, if supported by columns. Pediments can contain an overdoor and are usually topped by hood moulds.

A pedimen ...

of the Parthenon. The Venetians abandoned the attempt to remove further sculptures from the temple, and instead took a few marble lions, including the famous Piraeus Lion

The Piraeus Lion ( it, Leone del Pireo) is one of four lion statues on display at the Venetian Arsenal, Italy, where it was displayed as a symbol of Venice's patron saint, Saint Mark.

History

It was originally located in Piraeus, the harbour ...

, which had given the harbour its medieval name "Porto Leone", and which today stands at the entrance of the Venetian Arsenal. On 10 April, the Venetians evacuated Attica for the Peloponnese.

Attack on Negroponte (1688)

On 3 April 1688, Morosini was elected as the new

On 3 April 1688, Morosini was elected as the new Doge of Venice

The Doge of Venice ( ; vec, Doxe de Venexia ; it, Doge di Venezia ; all derived from Latin ', "military leader"), sometimes translated as Duke (compare the Italian '), was the chief magistrate and leader of the Republic of Venice between 726 a ...

, but retained command of the Venetian forces in Greece. The Senate made great efforts to replenish its forces in Greece, but once again, the need to await the expected reinforcements delayed the start of operations until the end of June. Despite the failure of the Athens expedition, the fortunes of war were still favourable: the Ottomans were reeling from a series of defeats in Hungary and Dalmatia: following the disastrous Battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács (; hu, mohácsi csata, tr, Mohaç Muharebesi or Mohaç Savaşı) was fought on 29 August 1526 near Mohács, Kingdom of Hungary, between the forces of the Kingdom of Hungary and its allies, led by Louis II, and those ...

, in November 1687, a mutiny broke out that resulted in the dismissal and execution of the Grand Vizier Sarı Süleyman Pasha and even the deposition of Sultan Mehmed IV (), who was replaced by his brother Suleiman II (). Several of Morosini's councillors suggested the moment opportune to attempt a reconquest of Crete, but the new Doge refused, and insisted on a campaign against Negroponte.

On 11 July, the first Venetian troops began disembarking at Negroponte, and laid siege to it two days later. The Venetians had assembled a substantial force, 13,000 troops and further 10,000 men in the fleet, against the Ottoman garrison of 6,000 men, which offered determined resistance. The Venetian fleet was unable to fully blockade the city, which allowed Ismail Pasha's forces, across the Euripus Strait, to ferry supplies to the besieged castle. The Venetians and their allies suffered great losses, especially from another outbreak of the plague, including General Königsmarck, who succumbed to the plague on 15 September, while the Knights of Malta and of St. Stephen departed the siege in early autumn. After a last assault on 12 October proved a costly failure, Morosini had to accept defeat. On 22 October, the Venetian army, having lost in total men, left Negroponte and headed for Argos. with them went the warlord Nikolaos Karystinos, who had launched an uprising in southern Euboea

Evia (, ; el, Εύβοια ; grc, Εὔβοια ) or Euboia (, ) is the second-largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete. It is separated from Boeotia in mainland Greece by the narrow Euripus Strait (only at its narrowest poin ...

and had tried, without success, to capture the castle of Karystos

Karystos ( el, Κάρυστος) or Carystus is a small coastal town on the Greece, Greek island of Euboea. It has about 5,000 inhabitants (12,000 in the municipality). It lies 129 km south of Chalkis. From Athens it is accessible by ferry ...

.

Depleted by the siege and by illness, the remnants of the Hannoverian and Hessian mercenaries departed Greece on 5 November. Morosini attempted an unsuccessful attack on Monemvasia in late 1689, but his failing health forced him to return to Venice soon after. He was replaced as commander-in-chief by Girolamo Cornaro. This marked the end of Venetian ascendancy, and the beginning of a number of successful, although in the end not decisive, Ottoman counteroffensives.

Battles in Dalmatia

In the Morean War, the Republic of Venice besieged Sinj in October 1684 and then again March and April 1685, but both times without success. In the 1685 attempt, the Venetian armies were aided by the local militia of theRepublic of Poljica

The Republic of Poljica or duchy ( hr, Poljička republika, in older form ''Poljička knežija'') was an autonomous community which existed in the late Middle Ages and the early modern period in central Dalmatia, near modern-day Omiš, Croatia. ...

, who thereby rebelled against their nominal Ottoman suzerainty that had existed since 1513. In an effort to retaliate to Poljica, in June 1685, the Ottomans attacked Zadvarje, and in July 1686 Dolac and Srijane, but were pushed back, and suffered major casualties. With the help of the local population of Poljica as well as the Morlachs

Morlachs ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, Morlaci, Морлаци or , ; it, Morlacchi; ro, Morlaci) has been an exonym used for a rural Christian community in Herzegovina, Lika and the Dalmatian Hinterland. The term was initially used for a bilingual Vlach p ...

, the fortress of Sinj finally fell to the Venetian army on 30 September 1686. On 1 September 1687 the siege of Herceg Novi started, and ended with a Venetian victory on 30 September. Knin was taken after a twelve-day siege on 11 September 1688. The capture of the Knin Fortress

Knin Fortress ( hr, Kninska tvrđava) is located near the tallest mountain in Croatia, Dinara, and near the source of the river Krka (Croatia), Krka. It is the second largest fortress in Croatia and most significant defensive stronghold,Hrvatska ...

marked the end of the successful Venetian campaign to expand their territory in inland Dalmatia, and it also determined much of the final border between Dalmatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of south and southeast Europe, located in the Balkans. Bosnia and H ...

that stands today. The Ottomans would besiege Sinj again in the Second Morean War

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds ...

, but would be repelled.

On 26 November 1690, Venice took Vrgorac

Vrgorac (, it, Vergoraz) is a town in Croatia in the Split-Dalmatia County.

Demographics

The total population of Vrgorac is 6,572 (census 2011), in the following settlements:

* Banja, population 202

* Dragljane, population 52

* Draževiti� ...

, which opened the route towards Imotski

Imotski (; it, Imoschi; lat, Emotha, later ''Imota'') is a small town on the northern side of the Biokovo massif in the Dalmatian Hinterland of southern Croatia, near the border with Bosnia and Herzegovina. Imotski, like the surrounding inland D ...

and Mostar

Mostar (, ; sr-Cyrl, Мостар, ) is a city and the administrative center of Herzegovina-Neretva Canton of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the historical capital of Herzegovina.

Mostar is sit ...

. In 1694 they managed to take areas north of the Republic of Ragusa

hr, Sloboda se ne prodaje za sve zlato svijeta it, La libertà non si vende nemmeno per tutto l'oro del mondo"Liberty is not sold for all the gold in the world"

, population_estimate = 90 000 in the XVI Century

, currency = ...

, namely Čitluk, Gabela, Zažablje

Zažablje is a municipality of Dubrovnik-Neretva County in southern Dalmatia, Croatia. It is located between Opuzen, Metković and Neum.

In the 2011 census, Zažablje had a total population of 757, with Croats

The Croats (; hr, Hrvati ) ...

, Trebinje, Popovo, Klobuk

Klobuk of Patriarch Philaret of Moscow (1619-33), Kremlin museum

A klobuk is an item of monastic clothing worn by monks and, in the Russian tradition, also by nuns, in the Byzantine Rite, composed of a kamilavka (stiffened round black headco ...

and Metković. In the final peace treaty, Venice did relinquish the areas of Popovo polje as well as Klek and Sutorina

Sutorina (, ) is a village and a river located in Herceg Novi Municipality in southwestern Montenegro.

The village is located near the border with Croatia, some three kilometers northwest of the Adriatic Sea in Igalo.

The surrounding region, incl ...

, to maintain the pre-existing demarcation near Ragusa.

Ottoman resurgence

The new Ottoman sultan initially desired a peace settlement, but the outbreak of the Nine Years' War in 1688, and the subsequent diversion of Austrian resources towards fighting France, encouraged the Ottoman leadership to continue the war. Under the capable leadership of the new Grand Vizier, Köprülü Fazıl Mustafa Pasha, the Ottomans went over to the counteroffensive. As the main effort was directed against Austria, the Ottomans were never able to spare enough men to reverse the Venetian gains completely.The rise of Limberakis Gerakaris

In late 1688, the Turks turned for help to the Maniot leaderLimberakis Gerakaris

Liverios Gerakaris ( el, Λιβέριος Γερακάρης; c. 1644 – 1710), more commonly known by the hypocoristic Limberakis ( el, Λιμπεράκης), was a Maniot pirate who later became Bey of Mani.

Limberakis Gerakaris was born i ...

, who had helped them during their invasion of Mani in the Cretan War, but had since been imprisoned at Constantinople for acts of piracy. He was released, invested as "Bey

Bey ( ota, بك, beğ, script=Arab, tr, bey, az, bəy, tk, beg, uz, бек, kz, би/бек, tt-Cyrl, бәк, translit=bäk, cjs, пий/пек, sq, beu/bej, sh, beg, fa, بیگ, beyg/, tg, бек, ar, بك, bak, gr, μπέης) is ...

of Mani", allowed to recruit a force of a few hundreds, and joined the Ottoman army at Thebes. Despite the fact that he never commanded any major army, Gerakaris was to play a major role in the latter stages of the war, since his daring and destructive raids destabilized Venetian control and proved a continuous drain on the Republic's resources. In spring 1689, Gerakaris conducted his first raid against the Venetian positions in western Central Greece, with a mixed force of 2,000 Turks, Albanians and Greeks. Gerakaris seized and torched Missolonghi

Missolonghi or Messolonghi ( el, Μεσολόγγι, ) is a municipality of 34,416 people (according to the 2011 census) in western Greece. The town is the capital of Aetolia-Acarnania regional unit, and the seat of the municipality of Iera Polis ...

, plundered the regions of Valtos and Xiromero, and launched attacks on the Venetian strongholds in Aitoliko and Vonitsa.

To counter this new threat, the Venetians renewed their attempts to win over local leaders and recruit local and refugee Greeks into militias. In this way, the Republic formed two warbands, one at Karpenisi

Karpenisi ( el, Καρπενήσι, ) is a town in central Greece. It is the capital of the regional unit of Evrytania. Karpenisi is situated in the valley of the river Karpenisiotis (Καρπενησιώτης), a tributary of the Megdovas, in t ...

under the Greek armatoloi captains and Dalmatian officers Spanos, Chormopoulos, Bossinas, Vitos, and Lubozovich, and another at Loidoriki

Lidoriki ( el, Λιδωρίκι, Katharevousa: Λιδωρίκιον) is a village and a former municipality in Phocis, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Dorida, of which it is the seat and a municipal uni ...

under the captains Kourmas, Meïdanis, and Elias Damianovich. At the same time, the large swathe of no man's land

No man's land is waste or unowned land or an uninhabited or desolate area that may be under dispute between parties who leave it unoccupied out of fear or uncertainty. The term was originally used to define a contested territory or a dump ...

between the Ottoman strongholds in the east and the Venetian-held territories in the west was increasingly a haven for independent warbands, both Christian and Muslim, who were augmented by Albanian and Dalmatian deserters from the Venetian army. The local population was thus at the mercy of the Venetians and their Greek and Dalmatian auxiliaries on the one hand, who extracted protection money, the depredations of marauding warbands, and the Ottomans, who still demanded the payment of regular taxes. The complexity of the conflict is illustrated by the fact that Gerakaris was repulsed in June 1689 in an attack on Salona (Amfissa

Amfissa ( el, Άμφισσα , also mentioned in classical sources as Amphissa) is a town in Phocis, Greece, part of the municipality of Delphi, of which it is the seat and a municipal unit. The municipal unit has an area of 315.174 km2. It l ...

) by the local inhabitants under Dimitrios Charopolitis and Elias Damianovich, but at about the same time, Gerakaris defended the villages of Agrafa and Karpenisi from marauding Christian warbands. Gerakaris attempted to persuade many of the independent warbands to enter Ottoman service, but without much success. He was more successful in persuading many of the Athenians who had fled the city in 1688 to return to their homes, after the Ottoman ''serasker'' guaranteed that there would be no reprisals against them.

In 1690, the reinforced Ottoman forces swept through Central Greece, and although they were repulsed in an attack on Lepanto, they re-established control over the hinterland east of Lepanto. The Venetians too scored a success: Monemvasia fell on 12 August 1690, thus removing the last Ottoman bastion in the Morea.

In 1692, Gerakaris spearheaded an Ottoman invasion of the Peloponnese. He took Corinth, and unsuccessfully besieged the Acrocorinth and Argos, before being forced to withdraw by the arrival of Venetian reinforcements. After renewed invasions into the Peloponnese in 1694 and 1695, Gerakaris went over to the Venetian camp. His brutal and savage treatment of the civilian population and his intriguing for the position of Bey of Mani could not be tolerated for long by Venice, and after the brutal sack of Arta Arta, ARTA, or Artà may refer to:

Places Djibouti

* Arta, Djibouti, a regional capital city in southeastern Djibouti

* Arta Mountains, a mountain range in Djibouti

* Arta Region, Djibouti

Greece

* Arta, Greece, a regional capital city in northwes ...

in August 1696, Gerakaris was arrested and imprisoned at Brescia

Brescia (, locally ; lmo, link=no, label= Lombard, Brèsa ; lat, Brixia; vec, Bressa) is a city and ''comune'' in the region of Lombardy, Northern Italy. It is situated at the foot of the Alps, a few kilometers from the lakes Garda and Iseo. ...

.

Operations in Montenegro

Venetians had important ties and considerable support among the Montenegrins, with solid ground established previously during the Cretan war. Venice strongly considered placing Montenegro under its own protection. In 1685, Montenegrin Metropolitan

Venetians had important ties and considerable support among the Montenegrins, with solid ground established previously during the Cretan war. Venice strongly considered placing Montenegro under its own protection. In 1685, Montenegrin Metropolitan Rufim Boljević

Rufim Boljević ( sr-cyr, Руфим Бољевић; 1673 – d. January 1685) was the Serbian Orthodox Metropolitan (''vladika'') of Cetinje from 1662 or 1673 until his death in January 1685. He succeeded Mardarije Kornečanin ( fl. 1640–59 ...

had died."The most loyal friend of Venice" at the time, as said by the Venetians themselves, after a brief tenure of Vasilije Veljekrajski was replaced by Visarion Borilović Bajica. Borilović ascended to the throne as a protege of his relative Patriarch of Peć

This article lists the heads of the Serbian Orthodox Church, since the establishment of the church as an autocephalous archbishopric in 1219 to today's patriarchate. The list includes all the archbishops and patriarchs that led the Serbian Ortho ...

Arsenije III Čarnojević. Previously a great supporter of Venice, after establishment of contact with Emperor's representatives in 1688, Arsenije became an important ally of the Habsburgs in the Balkans. Venetians were worried that under Arsenije's influence, who himself was of Montenegrin origin, the Montenegrins would lean more towards the Austrians, and thus kept at distance Visarion as well. The course of the Great Turkish war did not always coincide with Venetian interests, and thus this two-sided politics resulted in indecisive and irregular shape of the war in Montenegro. In their effort to win over Montenegrins at their side, Venice sent a detachment of Hajduks, led by their compatriot Bajo Pivljanin to Cetinje

Cetinje (, ) is a town in Montenegro. It is the former royal capital (''prijestonica'' / приjестоница) of Montenegro and is the location of several national institutions, including the official residence of the president of Montenegro ...

to rise the population against the Ottomans in 1685. The detachment was composed mainly of Montenegrins from Grbalj and Boka Kotorska. Previously, they demonstrated their intents during a short night attack on Herceg Novi on 22 August 1684. The Vizier of Skhoder, Suleyman Bushati, after threatening and pacifying the tribes of Kuči and Kelmendi