Battle Of Flodden Field on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of Flodden, Flodden Field, or occasionally Branxton, (Brainston Moor) was a battle fought on 9 September 1513 during the

On 18 August, five cannon brought down from

On 18 August, five cannon brought down from  On 24 August, James IV held a council or parliament at Twiselhaugh and made a proclamation for the benefit of the heirs of anyone killed during this invasion. By 29 August after a siege of six days, Bishop Thomas Ruthall's

On 24 August, James IV held a council or parliament at Twiselhaugh and made a proclamation for the benefit of the heirs of anyone killed during this invasion. By 29 August after a siege of six days, Bishop Thomas Ruthall's  A later Scottish chronicle writer,

A later Scottish chronicle writer,

On Sunday 4 September, James and the Scottish army had taken up a position at Flodden Edge, a hill to the south of Branxton. This was an immensely strong natural feature, since the flanks were protected by marshes on one side and steep slopes on the other, leaving only a direct approach. The amount of fortification which James constructed on the hill is disputed; several antiquaries had mapped supposed

On Sunday 4 September, James and the Scottish army had taken up a position at Flodden Edge, a hill to the south of Branxton. This was an immensely strong natural feature, since the flanks were protected by marshes on one side and steep slopes on the other, leaving only a direct approach. The amount of fortification which James constructed on the hill is disputed; several antiquaries had mapped supposed

During Thursday, 8 September, Surrey moved his army from Wooler Haugh and instead of heading northwest towards Flodden, he turned east across the River Till. From there, the English picked up the old

During Thursday, 8 September, Surrey moved his army from Wooler Haugh and instead of heading northwest towards Flodden, he turned east across the River Till. From there, the English picked up the old  Pitscottie says the vanguard crossed the bridge at 11 am and that James would not allow the Scots artillery to fire on the vulnerable English during this manoeuvre. This is not credible, since the bridge is some distant from Flodden, but James's scouts must have reported their approach. James quickly saw the threat and ordered his army to break camp and move to Branxton Hill, a commanding position which would deny the feature to the English and still give his pike formations the advantage of a downhill attack if the opportunity arose. The disadvantage was that the Scots were moving onto ground that had not been reconnoitered. The Lord Admiral, arriving with his vanguard at Branxton village, was unaware of the new Scottish position which was obscured by smoke from burning rubbish; when he finally caught sight of the Scottish army arrayed on Branxton Hill, he sent a messenger to his father urging him to hurry and also sending his

Pitscottie says the vanguard crossed the bridge at 11 am and that James would not allow the Scots artillery to fire on the vulnerable English during this manoeuvre. This is not credible, since the bridge is some distant from Flodden, but James's scouts must have reported their approach. James quickly saw the threat and ordered his army to break camp and move to Branxton Hill, a commanding position which would deny the feature to the English and still give his pike formations the advantage of a downhill attack if the opportunity arose. The disadvantage was that the Scots were moving onto ground that had not been reconnoitered. The Lord Admiral, arriving with his vanguard at Branxton village, was unaware of the new Scottish position which was obscured by smoke from burning rubbish; when he finally caught sight of the Scottish army arrayed on Branxton Hill, he sent a messenger to his father urging him to hurry and also sending his

James' army, somewhat reduced from the original 42,000 by sickness and desertion, still amounted to about 34,000, outnumbering the English force by 8,000. The Scottish army was organised into four divisions or

James' army, somewhat reduced from the original 42,000 by sickness and desertion, still amounted to about 34,000, outnumbering the English force by 8,000. The Scottish army was organised into four divisions or

In the meantime, James had observed Home and Huntley's initial success and ordered the advance of the next battle in line, commanded by Errol, Crawford and Montrose. At the foot of Branxton Hill, they encountered an unforeseen obstacle, an area of marshy ground, identified by modern

In the meantime, James had observed Home and Huntley's initial success and ordered the advance of the next battle in line, commanded by Errol, Crawford and Montrose. At the foot of Branxton Hill, they encountered an unforeseen obstacle, an area of marshy ground, identified by modern  It is unclear whether James had seen the difficulty encountered by the battle of the three earls, but he followed them down the slope regardless, making for Surrey's formation. James has been criticised for placing himself in the front line, thereby putting himself in personal danger and losing his overview of the field. He was, however, well-known for taking risks in battle and it would have been out of character for him to stay back. Encountering the same difficulties as the previous attack, James's men nevertheless fought their way to Surrey's bodyguard but no further. The final uncommitted Scottish formation, Argyll and Lennox's Highlanders, held back, perhaps awaiting orders. The last English formation to engage was Stanley's force which, after following a circuitous route from Barmoor, finally arrived on the right of the Scottish line. They loosed volleys of arrows into the Argyll and Lennox's battle, whose men lacked armour or any other effective defence against the archers. After suffering heavy casualties the Highlanders scattered.

The fierce fighting continued, centred on the contest between Surrey and James. As other English formations overcame the Scottish forces they had initially engaged, they moved to reinforce their leader. An instruction to English troops that no prisoners were to be taken explains the exceptional mortality amongst the Scottish nobility. James himself was killed in the final stage of the battle; his body was found surrounded by the corpses of his bodyguard of the Archers' Guard, recruited from the Forest of Ettrick and known as "the Flowers of the Forest". Despite having the finest armour available, the king's corpse was found to have two arrow wounds, one in the jaw, and wounds from bladed weapons to the neck and wrist. He was the last monarch to die in battle in the

It is unclear whether James had seen the difficulty encountered by the battle of the three earls, but he followed them down the slope regardless, making for Surrey's formation. James has been criticised for placing himself in the front line, thereby putting himself in personal danger and losing his overview of the field. He was, however, well-known for taking risks in battle and it would have been out of character for him to stay back. Encountering the same difficulties as the previous attack, James's men nevertheless fought their way to Surrey's bodyguard but no further. The final uncommitted Scottish formation, Argyll and Lennox's Highlanders, held back, perhaps awaiting orders. The last English formation to engage was Stanley's force which, after following a circuitous route from Barmoor, finally arrived on the right of the Scottish line. They loosed volleys of arrows into the Argyll and Lennox's battle, whose men lacked armour or any other effective defence against the archers. After suffering heavy casualties the Highlanders scattered.

The fierce fighting continued, centred on the contest between Surrey and James. As other English formations overcame the Scottish forces they had initially engaged, they moved to reinforce their leader. An instruction to English troops that no prisoners were to be taken explains the exceptional mortality amongst the Scottish nobility. James himself was killed in the final stage of the battle; his body was found surrounded by the corpses of his bodyguard of the Archers' Guard, recruited from the Forest of Ettrick and known as "the Flowers of the Forest". Despite having the finest armour available, the king's corpse was found to have two arrow wounds, one in the jaw, and wounds from bladed weapons to the neck and wrist. He was the last monarch to die in battle in the

Flodden was essentially a victory of the bill used by the English over the pike used by the Scots. The pike was an effective weapon only in a battle of movement, especially to withstand a cavalry charge. The Scottish pikes were described by the author of the ''Trewe Encounter'' as "keen and sharp spears 5 yards long". Although the pike had become a Swiss weapon of choice and represented modern warfare, the hilly terrain of Northumberland, the nature of the combat, and the slippery footing did not allow it to be employed to best effect. Bishop Ruthall reported to

Flodden was essentially a victory of the bill used by the English over the pike used by the Scots. The pike was an effective weapon only in a battle of movement, especially to withstand a cavalry charge. The Scottish pikes were described by the author of the ''Trewe Encounter'' as "keen and sharp spears 5 yards long". Although the pike had become a Swiss weapon of choice and represented modern warfare, the hilly terrain of Northumberland, the nature of the combat, and the slippery footing did not allow it to be employed to best effect. Bishop Ruthall reported to

As a reward for his victory, Thomas Howard was subsequently restored to the title of

As a reward for his victory, Thomas Howard was subsequently restored to the title of

Surrey's army lost 1,500 men killed in battle. There were various conflicting accounts of the Scottish loss. A contemporary account produced in French for the Royal Postmaster of England, in the immediate aftermath of the battle, states that about 10,000 Scots were killed, a claim repeated by Henry VIII on 16 September while he was still uncertain of the death of James IV. William Knight sent the news from

Surrey's army lost 1,500 men killed in battle. There were various conflicting accounts of the Scottish loss. A contemporary account produced in French for the Royal Postmaster of England, in the immediate aftermath of the battle, states that about 10,000 Scots were killed, a claim repeated by Henry VIII on 16 September while he was still uncertain of the death of James IV. William Knight sent the news from

Vol.1: 1509–1514: ''Archaeologia Aeliana or Miscellaneous Tracts'' Vol. 6 (1862)''Scots Peerage''

Vol.I, ed. Sir James Balfour Paul Clergy * Alexander Stewart,

vol.3 (1883), see index p.986 These names include Adam Hacket, husband of Helen Mason. The ''

The stained-glass Flodden Window in St Leonard's Church, Middleton, now in

The stained-glass Flodden Window in St Leonard's Church, Middleton, now in

''Grafton's Chronicle, or History of England: The Chronicle at Large, 1569'', vol.2, London (1809)

pp. 268–277 * Hall, Edward

''Chronicle of England'', (1809)

pp. 561–565 * Giovio, Paolo

''Pauli Jovii historiarum sui temporis'', (1549)

pp. 505–528 (Latin)

Pitscottie, Robert Lindsay of, ''The History and Chronicles of Scotland'', vol.1, Edinburgh (1814)

pp. 264–282. * ''The Trewe Encountre or Batayle Lately Don Between England and Scotland etc.'', Flaque (1513) i

Petrie, George, 'Account of Floddon in the 'Trewe Encountre' manuscript', ''Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries Scotland'', vol. 7, Edinburgh (1866–7), 141–152

* ''Letters & Papers Henry VIII'', vol.1, (1920) for the ''Articles of Batail'' and Tuke's letter, ''Calendar State Papers Venice'', vol.2 (1867) and see ''Calendar State Papers Milan'', vol. 1 (1912) * ''La Rotta de Scosesi'', in, Mackay Mackenzie, W., ''The Secret of Flodden'', (1931) * Barr, N., ''Flodden 1513'', 2001. * Barret, C. B., ''Battles and Battlefields in England'', 1896. * Bingham, C., "Flodden and its Aftermath", in ''The Scottish Nation'', ed. G. Menzies, 1972. * Burke's Landed Gentry of Scotland under Henderson of Fordell * Caldwell, D. H., ''Scotland's Wars and Warriors'', Edinburgh TSO (1998) *

Ellis, Henry, ed., ''Original Letters Illustrative of English History'', 1st Series, vol.1, Richard Bentley, London (1825)

pp. 82–99, Catherine of Aragon's letters.

Ellis, Henry, ed., ''Original Letters Illustrative of English History'', 3rd Series, vol.1, Richard Bentley, London (1846)

pp. 163–164, Dr. William Knight to Cardinal Bainbridge, 20 September 1513, Lille (Latin)

English Heritage Battlefield Report: Flodden, (1995), 13pp

* * * * Hodgkin, T., "The Battle of Flodden", in ''Arcaeologia Aeliania'', vol. 16, 1894. * * Leather, G. F. T., "The Battle of Flodden", in ''History of the Berwickshire Naturalists Club'', vol. 25, 1933. * Macdougall, N., ''James IV'', 1989. * Mackie, J. D., "The English Army at Flodden", in ''Miscellany of the Scottish History Society'', vol 8 1951. * Mackie, J.D., "The Auld Alliance and the Battle of Flodden", in ''Transactions of the Franco-Scottish Society'', 1835. * * * * * Sadler, John

''Flodden 1513: Scotland's Greatest Defeat''

The Life of Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey and Second Duke of Norfolk, 1443–1524

'. The Hague: Mouton Publishers. * White, R. H. (1859)

''The Battle of Flodden''

in ''Archaeologia Aeliania'', vol. 3, 1859 * White, R. H. (1862

''White's List''

in ''Archaeologia Aeliana or Miscellaneous Tracts: Volume 6'' (1862) pp. 69–79.

National Archives of Scotland

An account of the battle, from Our Past History

* John Skelton's Flodden poem,

A Ballade of the Scottyshe Kynge

'

Coldstream civic week. Annual event with commemorative rideout to the Flodden Memorial

A monument of the Battle of Flodden, Pastscape

Sir Walter Scott's account of the Laird of Muirhead's role protecting James IV in the Battle of Flodden

Flodden 1513 communities Ecomuseum project

Flodden 1513, the remembering Flodden project

Flodden 500 years anniversary (2013): Follow the community archaeological project excavating in and around Flodden battlefield

The Flooers O’ The Forest

Greentrax Recordings compilation CD of songs and music of Flodden.

www.iFlodden.info

{{DEFAULTSORT:Flodden, Battle Of 1513 in England 1513 in Scotland Battles between England and Scotland Battles of the War of the League of Cambrai

War of the League of Cambrai

The War of the League of Cambrai, sometimes known as the War of the Holy League and several other names, was fought from February 1508 to December 1516 as part of the Italian Wars of 1494–1559. The main participants of the war, who fough ...

between the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On ...

and the Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland (; , ) was a sovereign state in northwest Europe traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a ...

, resulting in an English victory. The battle was fought near Branxton in the county of Northumberland

Northumberland () is a ceremonial counties of England, county in Northern England, one of two counties in England which border with Scotland. Notable landmarks in the county include Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, Hadrian's Wall and Hexham Ab ...

in northern England, between an invading Scots army under King James IV

James IV (17 March 1473 – 9 September 1513) was King of Scotland from 11 June 1488 until his death at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. He inherited the throne at the age of fifteen on the death of his father, James III, at the Battle of Sauch ...

and an English army commanded by the Earl of Surrey

Earl of Surrey is a title in the Peerage of England that has been created five times. It was first created for William de Warenne, a close companion of William the Conqueror. It is currently held as a subsidiary title by the Dukes of Norfolk ...

. In terms of troop numbers, it was the largest battle fought between the two kingdoms."The Seventy Greatest Battles of All Time". Published by Thames & Hudson Ltd. 2005. Edited by Jeremy Black. Pages 95 to 97..

After besieging and capturing several English border castles, James encamped his invading army on a commanding hilltop position at Flodden and awaited the English force which had been sent against him, declining a challenge to fight in an open field. Surrey's army therefore carried out a circuitous march to position themselves in the rear of the Scottish camp. The Scots countered this by abandoning their camp and occupying the adjacent Branxton Hill, denying it to the English. The battle began with an artillery duel followed by a downhill advance by Scottish infantry armed with pikes. Unknown to the Scots, an area of marshy land lay in their path, which had the effect of breaking up their formations. This gave the English troops the chance to bring about a close-quarter battle, for which they were better equipped. James IV was killed in the fighting, becoming the last monarch from Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

to die in battle; this and the loss of a large proportion of the nobility led to a political crisis in Scotland. British historians sometimes use the Battle of Flodden to mark the end of the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

in the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles (O ...

; another candidate is the Battle of Bosworth Field

The Battle of Bosworth or Bosworth Field was the last significant battle of the Wars of the Roses, the civil war between the houses of Lancaster and York that extended across England in the latter half of the 15th century. Fought on 22 ...

in 1485.

Background

Centuries of intermittent warfare between England and Scotland had been formally brought to an end by the Treaty of Perpetual Peace which was signed in 1502. However, relations were soon soured by repeated cross-border raids, rivalry at sea leading to the death of the Scottishprivateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

Andrew Barton and the capture of his ships in 1511, and increasingly bellicose rhetoric by King Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disag ...

in claiming to be the overlord of Scotland. Conflict began when James IV, King of Scots

James IV (17 March 1473 – 9 September 1513) was King of Scotland from 11 June 1488 until his death at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. He inherited the throne at the age of fifteen on the death of his father, James III, at the Battle of Sauchi ...

, declared war on England to honour the Auld Alliance

The Auld Alliance (Scots for "Old Alliance"; ; ) is an alliance made in 1295 between the kingdoms of Scotland and France against England. The Scots word ''auld'', meaning ''old'', has become a partly affectionate term for the long-lasting as ...

with France by diverting Henry's English troops from their campaign against the French king, Louis XII

Louis XII (27 June 14621 January 1515), was List of French monarchs, King of France from 1498 to 1515 and King of Naples from 1501 to 1504. The son of Charles, Duke of Orléans, and Maria of Cleves, he succeeded his 2nd cousin once removed and b ...

. At this time, England was involved as a member of the " Catholic League" in the War of the League of Cambrai

The War of the League of Cambrai, sometimes known as the War of the Holy League and several other names, was fought from February 1508 to December 1516 as part of the Italian Wars of 1494–1559. The main participants of the war, who fough ...

, defending Italy and the Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

from the French, a part of the Italian Wars

The Italian Wars, also known as the Habsburg–Valois Wars, were a series of conflicts covering the period 1494 to 1559, fought mostly in the Italian peninsula, but later expanding into Flanders, the Rhineland and the Mediterranean Sea. The pr ...

.

Pope Leo X

Pope Leo X ( it, Leone X; born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, 11 December 14751 December 1521) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 March 1513 to his death in December 1521.

Born into the prominent political an ...

, already a signatory to the anti-French Treaty of Mechlin, sent a letter to James threatening him with ecclesiastical censure for breaking his peace treaties with England on 28 June 1513, and subsequently James was excommunicated

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

by Cardinal Christopher Bainbridge

Christopher Bainbridge ( 1462/1464 – 14 July 1514) was an English Cardinal of the Catholic Church. Of Westmorland origins, he was a nephew of Bishop Thomas Langton of Winchester, represented the continuation of Langton's influence and teachin ...

. James also summoned sailors and sent the Scottish navy, including the ''Great Michael

''Michael'', popularly known as ''Great Michael'', was a carrack or great ship of the Royal Scottish Navy. She was the largest ship built by King James IV of Scotland as part of his policy of building a strong Scottish navy.

She was ordered a ...

'', to join the ships of Louis XII of France. The fleet of twenty two vessels commanded by James Hamilton, 1st Earl of Arran

James Hamilton, 1st Earl of Arran and 2nd Lord Hamilton (c. 14751529) was a Scottish nobleman, naval commander and first cousin of James IV of Scotland. He also served as the 9th Lord High Admiral of Scotland.

Early life

He was the eldest of t ...

, departed from the Firth of Forth

The Firth of Forth () is the estuary, or firth, of several Scottish rivers including the River Forth. It meets the North Sea with Fife on the north coast and Lothian on the south.

Name

''Firth'' is a cognate of ''fjord'', a Norse word meanin ...

on 25 July accompanied by James as far as the Isle of May

The Isle of May is located in the north of the outer Firth of Forth, approximately off the coast of mainland Scotland. It is about long and wide. The island is owned and managed by NatureScot as a national nature reserve. There are now n ...

, intending to pass around the north of Scotland and create a diversion in Ireland before joining the French at Brest, from where it might cut the English line of communication across the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" ( Cotentinais) or (Jèrriais), ( Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kan ...

. However, the fleet was so badly delayed that it played no part in the war; unfortunately, James had sent most of his experienced artillerymen with the expedition, a decision which was to have unforeseen consequences for his land campaign.

Henry was in France with the Emperor Maximilian at the siege of Thérouanne

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characterize ...

. The Scottish Lyon King of Arms brought James IV's letter of 26 July to him. James asked him to desist from attacking France in breach of their treaty. Henry's exchange with Islay Herald or the Lyon King on 11 August at his tent at the siege was recorded. The Herald declared that Henry should abandon his efforts against the town and go home. Angered, Henry said that James had no right to summon him, and ought to be England's ally, as James was married to his (Henry's) sister, Margaret

Margaret is a female first name, derived via French () and Latin () from grc, μαργαρίτης () meaning "pearl". The Greek is borrowed from Persian.

Margaret has been an English name since the 11th century, and remained popular through ...

. He declared:And now, for a conclusion, recommend me to your master and tell him if he be so hardy to invade my realm or cause to enter one foot of my ground I shall make him as weary of his part as ever was man that began any such business. And one thing I ensure him by the faith that I have to the Crown of England and by the word of a King, there shall never King nor Prince make peace with me that ever his part shall be in it. Moreover, fellow, I care for nothing but for misentreating of my sister, that would God she were in England on a condition she cost the Schottes King not a penny.Henry also replied by letter on 12 August, writing that James was mistaken and that any of his attempts on England would be resisted. Using the pretext of revenge for the murder of Robert Kerr, a

Warden

A warden is a custodian, defender, or guardian. Warden is often used in the sense of a watchman or guardian, as in a prison warden. It can also refer to a chief or head official, as in the Warden of the Mint.

''Warden'' is etymologically ident ...

of the Scottish East March who had been killed by John "The Bastard" Heron in 1508, James invaded England with an army of about 30,000 men. However, both sides had been making lengthy preparations for this conflict. Henry VIII had already organised an army and artillery in the north of England to counter the expected invasion. Some of the guns had been returned to use against the Scots by Margaret of Austria, Duchess of Savoy

Archduchess Margaret of Austria (german: Margarete; french: Marguerite; nl, Margaretha; es, Margarita; 10 January 1480 – 1 December 1530) was Governor of the Habsburg Netherlands from 1507 to 1515 and again from 1519 to 1530. She was the firs ...

. A year earlier, Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey

Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk (144321 May 1524), styled Earl of Surrey from 1483 to 1485 and again from 1489 to 1514, was an English nobleman, soldier and statesman who served four monarchs. He was the eldest son of John Howard, 1st D ...

, had been appointed Lieutenant-General of the army of the north and was issued with banners of the Cross of St George

The Cross of Saint George (russian: Георгиевский крест, Georgiyevskiy krest) is a state decoration of the Russian Federation. It was initially established by Imperial Russia

The Russian Empire was an empire and the fi ...

and the Red Dragon of Wales. Only a small number of the light horsemen of the Scottish border had been sent to France. A northern army was maintained with artillery and its expense account starts on 21 July. The first captains were recruited in Lambeth. Many of these soldiers wore green and white Tudor colours. Surrey marched to Doncaster in July and then Pontefract, where he assembled more troops from northern England.

"Ill Raid"

On 5 August, a force estimated at up to 7,000 Scottishborder reivers

Border reivers were raiders along the Anglo-Scottish border from the late 13th century to the beginning of the 17th century. They included both Scottish and English people, and they raided the entire border country without regard to their v ...

commanded by Lord Home, crossed into Northumberland

Northumberland () is a ceremonial counties of England, county in Northern England, one of two counties in England which border with Scotland. Notable landmarks in the county include Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, Hadrian's Wall and Hexham Ab ...

and began to pillage farms and villages, taking anything of value before burning the houses. Surrey had taken the precaution of sending Sir William Bulmer north with 200 mounted archers, which Bulmer augmented with locally levied men to create a force approaching 1,000 in strength. On 13 August, they prepared an ambush for the Scots as they returned north laden with the spoils of their looting, by hiding in the broom

A broom (also known in some forms as a broomstick) is a cleaning tool consisting of usually stiff fibers (often made of materials such as plastic, hair, or corn husks) attached to, and roughly parallel to, a cylindrical handle, the broomstick. ...

bushes that grew shoulder-high on Milfield Plain. Surprising the Scots by a sudden volley of arrows, the English killed as many as 600 of the Scots before they were able to escape, leaving their booty and the Home family banner behind them. Although the "Ill Raid" had little effect on the forthcoming campaign, it may have influenced James's decision not to fight an open battle against Surrey on the same ground. Whether the raid was undertaken solely on Lord Home's initiative, or whether it had been authorised by James is unknown.

Invasion

On 18 August, five cannon brought down from

On 18 August, five cannon brought down from Edinburgh Castle

Edinburgh Castle is a historic castle in Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland. It stands on Castle Rock (Edinburgh), Castle Rock, which has been occupied by humans since at least the Iron Age, although the nature of the early settlement is unclear. ...

to the Netherbow Port at St Mary's Wynd for the invasion set off towards England dragged by borrowed oxen. On 19 August two ''gross culverin

A culverin was initially an ancestor of the hand-held arquebus, but later was used to describe a type of medieval and Renaissance cannon. The term is derived from the French "''couleuvrine''" (from ''couleuvre'' "grass snake", following the Lat ...

s'', four ''culverins pickmoyance'' and six (mid-sized) ''culverins moyane'' followed with the gunner Robert Borthwick and master carpenter John Drummond. The King himself set off that night with two hastily prepared standards of St Margaret and St Andrew.

Catherine of Aragon

Catherine of Aragon (also spelt as Katherine, ; 16 December 1485 – 7 January 1536) was Queen of England as the first wife of King Henry VIII from their marriage on 11 June 1509 until their annulment on 23 May 1533. She was previously ...

was regent in England. On 27 August, she issued warrants for the property of all Scotsmen in England to be seized. On hearing of the invasion on 3 September, she ordered Thomas Lovell to raise an army in the Midland counties.

In keeping with his understanding of the medieval code of chivalry

Chivalry, or the chivalric code, is an informal and varying code of conduct developed in Europe between 1170 and 1220. It was associated with the medieval Christian institution of knighthood; knights' and gentlemen's behaviours were governed b ...

, King James sent notice to the English, one month in advance, of his intent to invade. This gave the English time to gather an army. After a muster on the Burgh Muir

The Burgh Muir is the historic term for an extensive area of land lying to the south of Edinburgh city centre, upon which much of the southern part of the city now stands following its gradual spread and more especially its rapid expansion in th ...

of Edinburgh, the Scottish host moved to Ellemford, to the north of Duns, Scottish Borders

Duns is a town in the Scottish Borders, Scotland. It was the county town of the historic county of Berwickshire.

History

Early history

Duns Law, the original site of the town of Duns, has the remains of an Iron Age hillfort at its summit. ...

, and camped to wait for Angus

Angus may refer to:

Media

* ''Angus'' (film), a 1995 film

* ''Angus Og'' (comics), in the ''Daily Record''

Places Australia

* Angus, New South Wales

Canada

* Angus, Ontario, a community in Essa, Ontario

* East Angus, Quebec

Scotland

* Angu ...

and Home

A home, or domicile, is a space used as a permanent or semi-permanent residence for one or many humans, and sometimes various companion animals. It is a fully or semi sheltered space and can have both interior and exterior aspects to it ...

. The Scottish army, numbering some 42,000 men, crossed the River Tweed

The River Tweed, or Tweed Water ( gd, Abhainn Thuaidh, sco, Watter o Tweid, cy, Tuedd), is a river long that flows east across the Border region in Scotland and northern England. Tweed cloth derives its name from its association with the R ...

into England near Coldstream

Coldstream ( gd, An Sruthan Fuar , sco, Caustrim) is a town and civil parish in the Scottish Borders area of Scotland. A former burgh, Coldstream is the home of the Coldstream Guards, a regiment in the British Army.

Description

Coldstream l ...

; the exact date of the crossing is not recorded, but is generally accepted to have been 22 August. The Scottish troops were unpaid and were only required by feudal obligation to serve for forty days. Once across the border, a detachment turned south to attack Wark on Tweed Castle

Wark on Tweed Castle, sometimes referred to as Carham Castle, is a ruined motte-and-bailey castle at the West end of Wark on Tweed in Northumberland. The ruins are a Grade II* listed building.

History

The castle, which was built by Walter Espec ...

, while the bulk of the army followed the course of the Tweed downstream to the northeast to invest the remaining border castles.

On 24 August, James IV held a council or parliament at Twiselhaugh and made a proclamation for the benefit of the heirs of anyone killed during this invasion. By 29 August after a siege of six days, Bishop Thomas Ruthall's

On 24 August, James IV held a council or parliament at Twiselhaugh and made a proclamation for the benefit of the heirs of anyone killed during this invasion. By 29 August after a siege of six days, Bishop Thomas Ruthall's Norham Castle

Norham Castle (sometimes Nornam) is a castle in Northumberland, England, overlooking the River Tweed, on the border between England and Scotland. It is a Grade I listed building and a Scheduled Ancient Monument. The castle saw much action durin ...

was taken and partly demolished after the Scottish heavy artillery had breached the recently refurbished outer walls. The Scots then moved south, capturing the castles of Etal and Ford

Ford commonly refers to:

* Ford Motor Company, an automobile manufacturer founded by Henry Ford

* Ford (crossing), a shallow crossing on a river

Ford may also refer to:

Ford Motor Company

* Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company

* Ford F ...

.

A later Scottish chronicle writer,

A later Scottish chronicle writer, Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie

Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie (also Lindesay or Lyndsay; c. 1532–1580) was a Scottish chronicler, author of ''The Historie and Chronicles of Scotland, 1436–1565'', the first history of Scotland to be composed in Scots rather than Latin. ...

, tells the story that James wasted valuable time at Ford enjoying the company of Elizabeth, Lady Heron and her daughter. Edward Hall

Edward Hall ( – ) was an English lawyer and historian, best known for his ''The Union of the Two Noble and Illustre Families of Lancastre and Yorke''—commonly known as ''Hall's Chronicle''—first published in 1548. He was also sever ...

says that Lady Heron was a prisoner (in Scotland), and negotiated with James IV and the Earl of Surrey her own release and that Ford Castle would not be demolished for an exchange of prisoners. The English herald, Rouge Croix, came to Ford to appoint a place for battle on 4 September, with extra instructions that any Scottish herald

A herald, or a herald of arms, is an officer of arms, ranking between pursuivant and king of arms. The title is commonly applied more broadly to all officers of arms.

Heralds were originally messengers sent by monarchs or noblemen ...

s who were sent to Surrey were to be met where they could not view the English forces. Raphael Holinshed

Raphael Holinshed ( – before 24 April 1582) was an English chronicler, who was most famous for his work on ''The Chronicles of England, Scotlande, and Irelande'', commonly known as '' Holinshed's Chronicles''. It was the "first complete prin ...

's story is that a part of the Scottish army returned to Scotland, and the rest stayed at Ford waiting for Norham to surrender and debating their next move. James IV wanted to fight and considered moving to assault Berwick-upon-Tweed

Berwick-upon-Tweed (), sometimes known as Berwick-on-Tweed or simply Berwick, is a town and civil parish in Northumberland, England, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, and the northernmost town in England. The 2011 United Kingdom census recor ...

, but the Earl of Angus spoke against this and said that Scotland had done enough for France. James sent Angus home, and according to Holinshed, the Earl burst into tears and left, leaving his two sons, the Master of Angus and Glenbervie

Glenbervie (Scottish Gaelic: ''Gleann Biorbhaidh'', Scots: ''Bervie'') is located in the north east of Scotland in the Howe o' the Mearns, one mile from the village of Drumlithie and eight miles south of Stonehaven in Aberdeenshire. The river B ...

, with most of the Douglas kindred to fight.

In the meantime, Surrey was reluctant to commit his army too early, since once in the field they had to be paid and fed at enormous expense. From his encampment at Pontefract

Pontefract is a historic market town in the Metropolitan Borough of Wakefield in West Yorkshire, England, east of Wakefield and south of Castleford. Historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, it is one of the towns in the City of Wake ...

, he issued an order for forces raised in the northern counties to assemble at Newcastle on Tyne on 1 September. Surrey had 500 soldiers with him and was to be joined at Newcastle by 1,000 experienced soldiers and sailors with their artillery, who would arrive by sea under the command of Surrey's son, also called Thomas Howard, the Lord High Admiral of England

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or a ...

. By 28 August, Surrey had arrived at Durham Cathedral

The Cathedral Church of Christ, Blessed Mary the Virgin and St Cuthbert of Durham, commonly known as Durham Cathedral and home of the Shrine of St Cuthbert, is a cathedral in the city of Durham, County Durham, England. It is the seat of ...

where he was presented with the banner of Saint Cuthbert

Cuthbert of Lindisfarne ( – 20 March 687) was an Anglo-Saxons, Anglo-Saxon saint of the early Northumbrian church in the Hiberno-Scottish mission, Celtic tradition. He was a monk, bishop and hermit, associated with the monastery, monasterie ...

, which had been carried by the English in victories against the Scots in 1138 and 1346. On 3 September, Surrey moved his advanced guard to Alnwick

Alnwick ( ) is a market town in Northumberland, England, of which it is the traditional county town. The population at the 2011 Census was 8,116.

The town is on the south bank of the River Aln, south of Berwick-upon-Tweed and the Scottish bo ...

while he awaited the completion of the muster and the arrival of the Lord Admiral whose ships had been delayed by storms.

Surrey's challenge

On Sunday 4 September, James and the Scottish army had taken up a position at Flodden Edge, a hill to the south of Branxton. This was an immensely strong natural feature, since the flanks were protected by marshes on one side and steep slopes on the other, leaving only a direct approach. The amount of fortification which James constructed on the hill is disputed; several antiquaries had mapped supposed

On Sunday 4 September, James and the Scottish army had taken up a position at Flodden Edge, a hill to the south of Branxton. This was an immensely strong natural feature, since the flanks were protected by marshes on one side and steep slopes on the other, leaving only a direct approach. The amount of fortification which James constructed on the hill is disputed; several antiquaries had mapped supposed rampart

Rampart may refer to:

* Rampart (fortification), a defensive wall or bank around a castle, fort or settlement

Rampart may also refer to:

* "O'er the Ramparts We Watched" is a key line from "The Star-Spangled Banner", the national anthem of the ...

s and bastion

A bastion or bulwark is a structure projecting outward from the curtain wall of a fortification, most commonly angular in shape and positioned at the corners of the fort. The fully developed bastion consists of two faces and two flanks, with fi ...

s there over the centuries, but excavations conducted between 2009 and 2015 found no trace of 16th century work and concluded that James may have reused some features of an Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

hill fort

A hillfort is a type of earthwork used as a fortified refuge or defended settlement, located to exploit a rise in elevation for defensive advantage. They are typically European and of the Bronze Age or Iron Age. Some were used in the post- ...

.

The Earl of Surrey, writing at Wooler

Wooler ( ) is a small town in Northumberland, England. It lies on the edge of the Northumberland National Park, near the Cheviot Hills. It is a popular base for walkers and is referred to as the "Gateway to the Cheviots". As well as many shops ...

Haugh on Wednesday 7 September, compared this position to a fortress in a challenge sent to James IV by his herald, Thomas Hawley, the Rouge Croix Pursuivant

Rouge Croix Pursuivant of Arms in Ordinary is a junior officer of arms of the College of Arms. He is said to be the oldest of the four pursuivants in ordinary. The office is named after St George's Cross which has been a symbol of England since th ...

. Surrey complained that James had sent his Islay Herald, agreeing that they would join in battle on Friday between 12 noon and 3 pm, and asked that James would face him on the plain at Milfield as appointed. James had no intention of leaving his carefully prepared position, perhaps recalling the fate of the Ill Raid on the same plain; he replied to Surrey that it was "not fitting for an Earl to seek to command a King". This put Surrey in a difficult position; the choice was to make a frontal attack on Flodden Edge, uphill in the face of the Scottish guns in their prepared position and in all probability be defeated, or to refuse battle, earning disgrace and the anger of King Henry. Waiting for James to make a move was not an option because his 26,000 strong army desperately needed resupply, the convoy of wagons bringing food and beer for the troops from Newcastle having been ambushed and looted by local Englishmen. During a council of war on Wednesday evening, an ingenious alternative plan was devised, advised by "the Bastard" Heron, who had intimate local knowledge and had recently arrived at the English camp.

Battle

Initial manoeuvres

During Thursday, 8 September, Surrey moved his army from Wooler Haugh and instead of heading northwest towards Flodden, he turned east across the River Till. From there, the English picked up the old

During Thursday, 8 September, Surrey moved his army from Wooler Haugh and instead of heading northwest towards Flodden, he turned east across the River Till. From there, the English picked up the old Roman road

Roman roads ( la, viae Romanae ; singular: ; meaning "Roman way") were physical infrastructure vital to the maintenance and development of the Roman state, and were built from about 300 BC through the expansion and consolidation of the Roman R ...

known as the Devil's Causeway and headed north, making camp at Barmoor, near Lowick. James may have assumed that Surrey was heading for Berwick-upon-Tweed for resupply, but he was actually intending to outflank the Scots and either attack or blockade them from the rear. At 5 am on the morning of Friday, 9 September, after a damp night on short rations and having to drink water from streams because the beer had run out, Surrey's men set off westwards to complete their manoeuvre. Their objective was Branxton Hill, lying less than north of James's camp at Flodden. In order to re-cross the River Till, the English army split into two; one force under Surrey crossed by means of several ford

Ford commonly refers to:

* Ford Motor Company, an automobile manufacturer founded by Henry Ford

* Ford (crossing), a shallow crossing on a river

Ford may also refer to:

Ford Motor Company

* Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company

* Ford F ...

s near Heaton Castle, while a larger vanguard

The vanguard (also called the advance guard) is the leading part of an advancing military formation. It has a number of functions, including seeking out the enemy and securing ground in advance of the main force.

History

The vanguard derives f ...

numbering some 15,000 commanded by the Lord Admiral and including the artillery train, crossed at Twizell Bridge downstream.

Pitscottie says the vanguard crossed the bridge at 11 am and that James would not allow the Scots artillery to fire on the vulnerable English during this manoeuvre. This is not credible, since the bridge is some distant from Flodden, but James's scouts must have reported their approach. James quickly saw the threat and ordered his army to break camp and move to Branxton Hill, a commanding position which would deny the feature to the English and still give his pike formations the advantage of a downhill attack if the opportunity arose. The disadvantage was that the Scots were moving onto ground that had not been reconnoitered. The Lord Admiral, arriving with his vanguard at Branxton village, was unaware of the new Scottish position which was obscured by smoke from burning rubbish; when he finally caught sight of the Scottish army arrayed on Branxton Hill, he sent a messenger to his father urging him to hurry and also sending his

Pitscottie says the vanguard crossed the bridge at 11 am and that James would not allow the Scots artillery to fire on the vulnerable English during this manoeuvre. This is not credible, since the bridge is some distant from Flodden, but James's scouts must have reported their approach. James quickly saw the threat and ordered his army to break camp and move to Branxton Hill, a commanding position which would deny the feature to the English and still give his pike formations the advantage of a downhill attack if the opportunity arose. The disadvantage was that the Scots were moving onto ground that had not been reconnoitered. The Lord Admiral, arriving with his vanguard at Branxton village, was unaware of the new Scottish position which was obscured by smoke from burning rubbish; when he finally caught sight of the Scottish army arrayed on Branxton Hill, he sent a messenger to his father urging him to hurry and also sending his Agnus Dei

is the Latin name under which the "Lamb of God" is honoured within the Catholic Mass and other Christian liturgies descending from the Latin liturgical tradition. It is the name given to a specific prayer that occurs in these liturgies, and i ...

pendant to underline the gravity of his situation. In the meantime, he positioned his troops in dead ground from where he hoped that the Scots could not assess the size of his force. James declined to attack the vulnerable vanguard, reportedly saying that he was "determined to have them all in front of me on one plain field and see what all of them can do against me".

Opposing forces

James' army, somewhat reduced from the original 42,000 by sickness and desertion, still amounted to about 34,000, outnumbering the English force by 8,000. The Scottish army was organised into four divisions or

James' army, somewhat reduced from the original 42,000 by sickness and desertion, still amounted to about 34,000, outnumbering the English force by 8,000. The Scottish army was organised into four divisions or battle

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

s. That on the left wing was commanded by the Earls of Home and Huntley and consisted of a combination of Borderers and Highlander

Highlander may refer to:

Regional cultures

* Gorals (lit. ''Highlanders''), a culture in southern Poland and northern Slovakia

* Hill people, who live in hills and mountains

* Merina people, an ethnic group from the central plateau of Madagascar

...

s. Next in the line was the battle commanded by the Earls of Erroll, Crawford and Montrose composed of men from the northeast of Scotland. The third was commanded by James himself together with his son Alexander and the Earls of Cassillis, Rothes and Caithness. On the right, the Earls of Argyll

Argyll (; archaically Argyle, in modern Gaelic, ), sometimes called Argyllshire, is a historic county and registration county of western Scotland.

Argyll is of ancient origin, and corresponds to most of the part of the ancient kingdom of ...

and Lennox commanded a force drawn from the Highlands and Islands

The Highlands and Islands is an area of Scotland broadly covering the Scottish Highlands, plus Orkney, Shetland and Outer Hebrides (Western Isles).

The Highlands and Islands are sometimes defined as the area to which the Crofters' Act of 1886 ...

. Some sources state that there was a fifth battle acting as a reserve, perhaps commanded by the Earl of Bothwell

Earl of Bothwell was a title that was created twice in the Peerage of Scotland. It was first created for Patrick Hepburn in 1488, and was forfeited in 1567. Subsequently, the earldom was re-created for the 4th Earl's nephew and heir of line, Fr ...

. The Scottish infantry had been equipped with long pikes by their French allies; a new weapon which had proved devastating in continental Europe, but required training, discipline and suitable terrain to use effectively. The Scottish artillery, consisting mainly of heavy siege gun

Siege artillery (also siege guns or siege cannons) are heavy guns designed to bombard fortifications, cities, and other fixed targets. They are distinct from field artillery and are a class of siege weapon capable of firing heavy cannonballs or ...

s, included five great curtals and two great culverin

A culverin was initially an ancestor of the hand-held arquebus, but later was used to describe a type of medieval and Renaissance cannon. The term is derived from the French "''couleuvrine''" (from ''couleuvre'' "grass snake", following the Lat ...

s (known as "the Seven Sisters"), together with four sakers, and six great serpentines. These modern weapons fired an iron ball weighing up to to a range of . However, the heaviest of these required a team of 36 oxen to move each one and were only able to fire once every twenty minutes at the most. They were commanded by the king's secretary, Patrick Paniter

Patrick Paniter (born c. 1470 - 1519) Scottish churchman and principal secretary to James IV of Scotland and the infant James V. The surname is usually written ''Paniter'', or ''Painter'', or occasionally ''Panter''.

Life

Paniter was born around ...

, an able diplomat, but who had no artillery experience.

Upon Surrey's arrival, he deployed his troops on the forward slope of Piper Hill to match the Scottish dispositions. On his right, facing Hume and Huntley, was a battle composed of men from Cheshire, Lancashire and Yorkshire, commanded by Surrey's third son, Lord Edmund Howard

Lord Edmund Howard ( – 19 March 1539) was the third son of Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk, and his first wife, Elizabeth Tilney. His sister, Elizabeth, was the mother of Henry VIII's second wife, Anne Boleyn, and he was the father of t ...

. Of the central battles, one was commanded by the Lord Admiral and the other by Surrey himself. Sir Edward Stanley

Edward Stanley, 1st Baron Monteagle KG (1460?–1523) was an English soldier who became a peer and Knight of the Garter. He is known for his deeds at the Battle of Flodden.

Life

Born about 1460, he was fifth son of Thomas Stanley, 1st Earl of ...

's force of cavalry and archers had been the last to leave Barmoor and would not arrive on the left flank until later in the day. A reserve of mounted Borderers commanded by Thomas, Baron Dacre

Baron Dacre is a title that has been created three times in the Peerage of England, every time by writ.

History

The first creation came in 1321 when Ralph Dacre was summoned to Parliament as Lord Dacre. He married Margaret, 2nd Baroness Mult ...

were positioned to the rear. The English infantry were equipped with traditional polearm

A polearm or pole weapon is a close combat weapon in which the main fighting part of the weapon is fitted to the end of a long shaft, typically of wood, thereby extending the user's effective range and striking power. Polearms are predominantly ...

s, mostly bills which were their favoured weapon. There was also a large contingent of well-trained archer

Archery is the sport, practice, or skill of using a bow to shoot arrows.Paterson ''Encyclopaedia of Archery'' p. 17 The word comes from the Latin ''arcus'', meaning bow. Historically, archery has been used for hunting and combat. In mo ...

s armed with the English longbow

The English longbow was a powerful medieval type of bow, about long. While it is debated whether it originated in England or in Wales from the Welsh bow, by the 14th century the longbow was being used by both the English and the Welsh as ...

. The English artillery consisted of light field gun

A field gun is a field artillery piece. Originally the term referred to smaller guns that could accompany a field army on the march, that when in combat could be moved about the battlefield in response to changing circumstances (field artiller ...

s of rather old-fashioned design, typically firing a ball of only about , but they were easily handled and capable of rapid fire.

Engagement

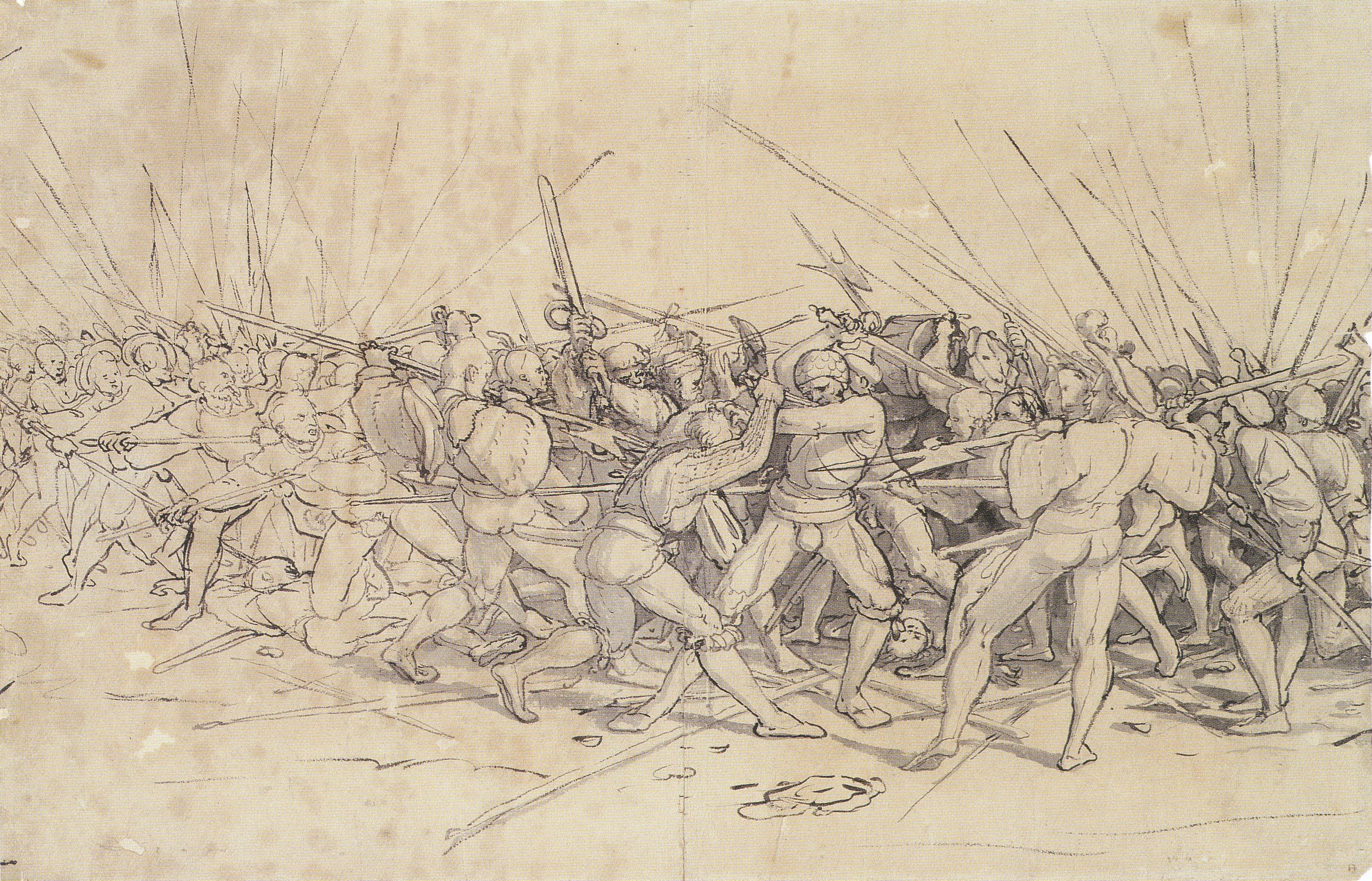

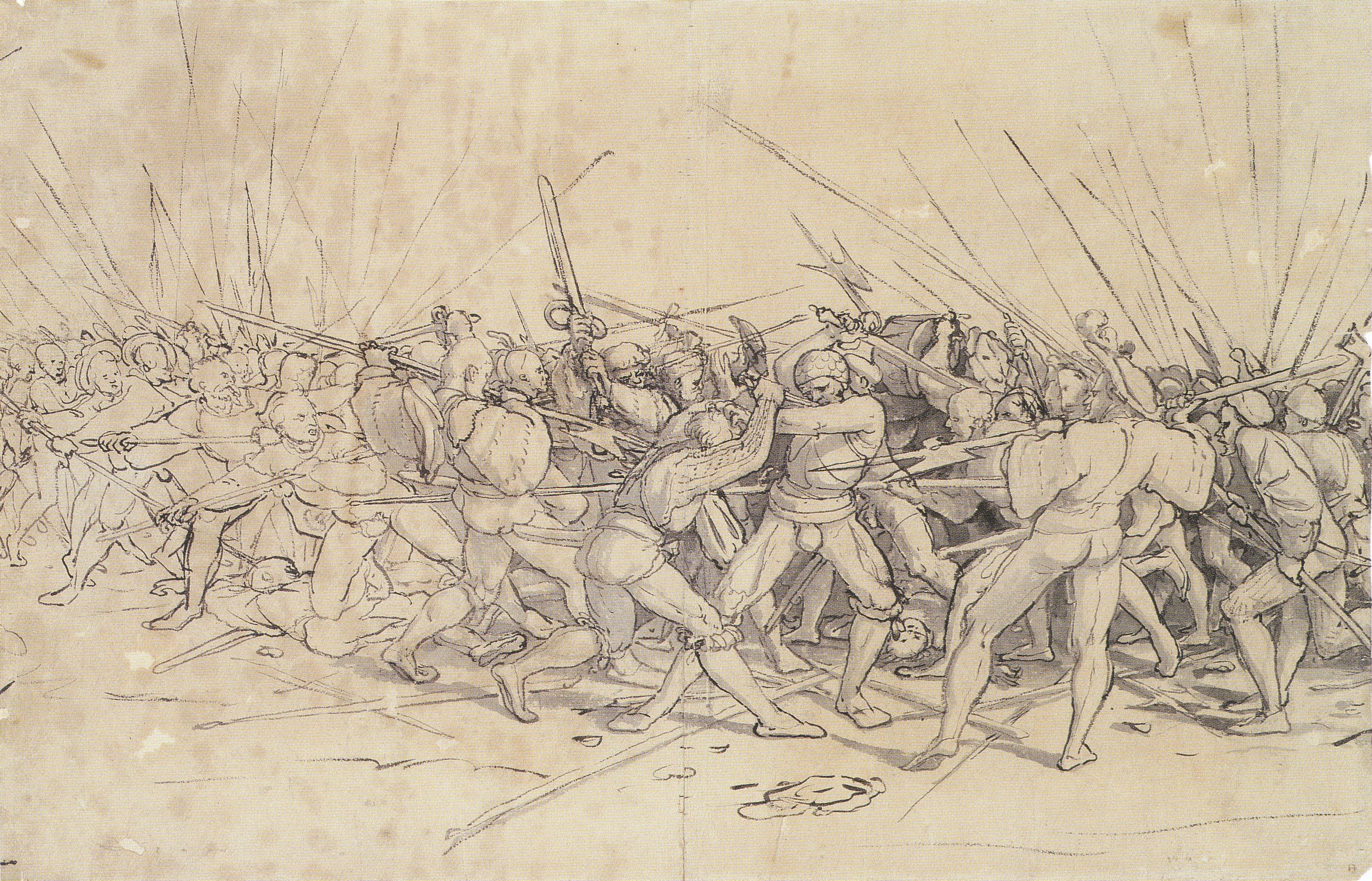

At about 4 pm on Friday in wet and windy weather, James began the battle with an artillery duel, but his big guns did not perform as well as he had hoped. Contemporary accounts put this down to the difficulty for the Scots of shooting downhill, but another factor must have been that their guns had been poorly sited instead of being carefully emplaced, which was usually required for such heavy weapons, further slowing their ponderous rate of fire. This may explain English claims that the Scottish guns were destroyed by return fire, when in fact they were captured undamaged after the battle. The apparent silence of the Scottish artillery allowed the light English guns to turn a rapid fire on the massed ranks of infantry, although the effectiveness of this bombardment is difficult to assess. The next phase started when Home and Huntley's battle on the Scottish left advanced downhill towards the opposite troops commanded by Edmund Howard. They advanced, according to the English, "in good order, after the Alamayns .e. Germanmanner, without speaking a word". The Scots had placed their most heavily armoured men in the front rank, so that the English archers had little impact. The outnumbered English battle was forced back and elements of it began to run off. Surrey saved his son from disaster by ordering the intervention of Dacre's light horsemen, who were able to approach unobserved in the dead ground that had been exploited earlier by the vanguard. The eventual result was a stalemate in which both sides stood off from each other and played no further part in the battle. According to later accounts, when Huntley suggested that they rejoin the fighting, Home replied: "the man does well this day who saves himself: we fought those who were opposed to us and beat them; let our other companies do the same!". In the meantime, James had observed Home and Huntley's initial success and ordered the advance of the next battle in line, commanded by Errol, Crawford and Montrose. At the foot of Branxton Hill, they encountered an unforeseen obstacle, an area of marshy ground, identified by modern

In the meantime, James had observed Home and Huntley's initial success and ordered the advance of the next battle in line, commanded by Errol, Crawford and Montrose. At the foot of Branxton Hill, they encountered an unforeseen obstacle, an area of marshy ground, identified by modern hydrologist

Hydrology () is the scientific study of the movement, distribution, and management of water on Earth and other planets, including the water cycle, water resources, and environmental watershed sustainability. A practitioner of hydrology is calle ...

s as a groundwater seepage zone, made worse by days of heavy rain. As they struggled to cross the waterlogged ground, the Scots lost the cohesion and momentum on which pike formations depended for success. Once the line was disrupted, the long pikes became an unwieldy encumbrance, and the Scots began to drop them "so that it seemed as if a wood were falling down" according to a later English poem. Reaching for their side-arms of swords and axes, they found themselves outreached by the English bills in the close-quarter fighting that developed.

It is unclear whether James had seen the difficulty encountered by the battle of the three earls, but he followed them down the slope regardless, making for Surrey's formation. James has been criticised for placing himself in the front line, thereby putting himself in personal danger and losing his overview of the field. He was, however, well-known for taking risks in battle and it would have been out of character for him to stay back. Encountering the same difficulties as the previous attack, James's men nevertheless fought their way to Surrey's bodyguard but no further. The final uncommitted Scottish formation, Argyll and Lennox's Highlanders, held back, perhaps awaiting orders. The last English formation to engage was Stanley's force which, after following a circuitous route from Barmoor, finally arrived on the right of the Scottish line. They loosed volleys of arrows into the Argyll and Lennox's battle, whose men lacked armour or any other effective defence against the archers. After suffering heavy casualties the Highlanders scattered.

The fierce fighting continued, centred on the contest between Surrey and James. As other English formations overcame the Scottish forces they had initially engaged, they moved to reinforce their leader. An instruction to English troops that no prisoners were to be taken explains the exceptional mortality amongst the Scottish nobility. James himself was killed in the final stage of the battle; his body was found surrounded by the corpses of his bodyguard of the Archers' Guard, recruited from the Forest of Ettrick and known as "the Flowers of the Forest". Despite having the finest armour available, the king's corpse was found to have two arrow wounds, one in the jaw, and wounds from bladed weapons to the neck and wrist. He was the last monarch to die in battle in the

It is unclear whether James had seen the difficulty encountered by the battle of the three earls, but he followed them down the slope regardless, making for Surrey's formation. James has been criticised for placing himself in the front line, thereby putting himself in personal danger and losing his overview of the field. He was, however, well-known for taking risks in battle and it would have been out of character for him to stay back. Encountering the same difficulties as the previous attack, James's men nevertheless fought their way to Surrey's bodyguard but no further. The final uncommitted Scottish formation, Argyll and Lennox's Highlanders, held back, perhaps awaiting orders. The last English formation to engage was Stanley's force which, after following a circuitous route from Barmoor, finally arrived on the right of the Scottish line. They loosed volleys of arrows into the Argyll and Lennox's battle, whose men lacked armour or any other effective defence against the archers. After suffering heavy casualties the Highlanders scattered.

The fierce fighting continued, centred on the contest between Surrey and James. As other English formations overcame the Scottish forces they had initially engaged, they moved to reinforce their leader. An instruction to English troops that no prisoners were to be taken explains the exceptional mortality amongst the Scottish nobility. James himself was killed in the final stage of the battle; his body was found surrounded by the corpses of his bodyguard of the Archers' Guard, recruited from the Forest of Ettrick and known as "the Flowers of the Forest". Despite having the finest armour available, the king's corpse was found to have two arrow wounds, one in the jaw, and wounds from bladed weapons to the neck and wrist. He was the last monarch to die in battle in the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles (O ...

. Home, Huntley and their troops were the only formation to escape intact; others escaped in small groups, closely pursued by the English.

Tactics and aftermath

Soon after the battle, the council of Scotland decided to send for help fromChristian II of Denmark

Christian II (1 July 1481 – 25 January 1559) was a Scandinavian monarch under the Kalmar Union who reigned as King of Denmark and Norway, from 1513 until 1523, and Sweden from 1520 until 1521. From 1513 to 1523, he was concurrently Du ...

. The Scottish ambassador, Andrew Brounhill, was given instructions to explain "how this cais is hapnit." Brounhill's instructions blame James IV for moving down the hill to attack the English on marshy ground from a favourable position, and credits the victory to Scottish inexperience rather than English valour. The letter also mentions that the Scots placed their officers in the front line in medieval style, where they were vulnerable, contrasting this loss of the nobility with the English great men who took their stand with the reserves and at the rear. The English generals stayed behind the lines in the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

style. The loss of so many Scottish officers meant there was no one to co-ordinate a retreat.

However, according to contemporary English reports, Thomas Howard marched on foot leading the English vanguard to the foot of the hill. Howard was moved to dismount and do this by taunts of cowardice sent by James IV's heralds, apparently based on his role at sea and the death two years earlier of the Scottish naval officer Sir Andrew Barton. A version of Howard's declaration to James IV that he would lead the vanguard and take no prisoners was included in later English chronicle accounts of the battle. Howard claimed his presence in "proper person" at the front was his trial by combat

Trial by combat (also wager of battle, trial by battle or judicial duel) was a method of Germanic law to settle accusations in the absence of witnesses or a confession in which two parties in dispute fought in single combat; the winner of th ...

for Barton's death.

Weaponry

Flodden was essentially a victory of the bill used by the English over the pike used by the Scots. The pike was an effective weapon only in a battle of movement, especially to withstand a cavalry charge. The Scottish pikes were described by the author of the ''Trewe Encounter'' as "keen and sharp spears 5 yards long". Although the pike had become a Swiss weapon of choice and represented modern warfare, the hilly terrain of Northumberland, the nature of the combat, and the slippery footing did not allow it to be employed to best effect. Bishop Ruthall reported to

Flodden was essentially a victory of the bill used by the English over the pike used by the Scots. The pike was an effective weapon only in a battle of movement, especially to withstand a cavalry charge. The Scottish pikes were described by the author of the ''Trewe Encounter'' as "keen and sharp spears 5 yards long". Although the pike had become a Swiss weapon of choice and represented modern warfare, the hilly terrain of Northumberland, the nature of the combat, and the slippery footing did not allow it to be employed to best effect. Bishop Ruthall reported to Thomas Wolsey

Thomas Wolsey ( – 29 November 1530) was an English statesman and Catholic bishop. When Henry VIII became King of England in 1509, Wolsey became the king's almoner. Wolsey's affairs prospered and by 1514 he had become the controlling figu ...

, 'the bills disappointed the Scots of their long spears, on which they relied.' The infantrymen at Flodden, both Scots and English, had fought essentially like their ancestors, and Flodden has been described as the last great medieval battle in the British Isles. This was the last time that bill and pike would come together as equals in battle. Two years later Francis I of France

Francis I (french: François Ier; frm, Francoys; 12 September 1494 – 31 March 1547) was King of France from 1515 until his death in 1547. He was the son of Charles, Count of Angoulême, and Louise of Savoy. He succeeded his first cousin onc ...

defeated the Swiss pikemen at the Battle of Marignano

The Battle of Marignano was the last major engagement of the War of the League of Cambrai and took place on 13–14 September 1515, near the town now called Melegnano, 16 km southeast of Milan. It pitted the French army, composed of the ...

, using a combination of heavy cavalry and artillery, ushering in a new era in the history of war. An official English diplomatic report issued by Brian Tuke

Sir Brian Tuke (died 1545) was the secretary of Henry VIII and Cardinal Wolsey. He became treasurer of the household.

Life

He may have been the son of Richard Tuke (died 1498?) and Agnes his wife, daughter of John Bland of Nottinghamshire. The ...

noted the Scots' iron spears and their initial "very good order after the German fashion", but concluded that "the English halberdiers decided the whole affair, so that in the battle the bows and ordnance were of little use."

Despite Tuke's comment (he was not present), this battle was one of the first major engagements in the British Isles where artillery was significantly deployed. John Lesley

John Lesley (or Leslie) (29 September 1527 – 31 May 1596) was a Scottish Roman Catholic bishop and historian. His father was Gavin Lesley, rector of Kingussie, Badenoch.

Early career

He was educated at the University of Aberdeen, where he ...

, writing sixty years later, noted that the Scottish bullets flew over the English heads while the English cannon was effective: the one army placed so high and the other so low.

The Scots advance down the hill was resisted by a hail of arrows, an incident celebrated in later English ballads. Hall says that the armoured front line was mostly unaffected; this is confirmed by the ballads which note that some few Scots were wounded in the scalp and, wrote Hall, James IV sustained a significant arrow wound. Many of the archers were recruited from Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a Historic counties of England, historic county, Ceremonial County, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significa ...

and Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a ceremonial and historic county in North West England, bordered by Wales to the west, Merseyside and Greater Manchester to the north, Derbyshire to the east, and Staffordshire and Shropshire to the south. Cheshire's coun ...

. Sir Richard Assheton raised one such company from Middleton, near Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of City of Salford, Salford to ...

. He rebuilt his parish church St. Leonard's, Middleton, which contains the unique "Flodden Window." It depicts and names the archers and their priest in stained glass. The window has been called the oldest known war memorial in the UK. The success of the Cheshire yeomanry, under the command of Richard Cholmeley, led to his later appointment as Lieutenant of the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sepa ...

.

Honours

Duke of Norfolk

Duke of Norfolk is a title in the peerage of England. The seat of the Duke of Norfolk is Arundel Castle in Sussex, although the title refers to the county of Norfolk. The current duke is Edward Fitzalan-Howard, 18th Duke of Norfolk. The du ...

, lost by his father's support for Richard III

Richard III (2 October 145222 August 1485) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 26 June 1483 until his death in 1485. He was the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty. His defeat and death at the Bat ...

. The arms of the Dukes of Norfolk still carry an augmentation of honour awarded on account of their ancestor's victory at Flodden, a modified version of the Royal coat of arms of Scotland

The royal arms of Scotland is the official coat of arms of the King of Scots first adopted in the 12th century.

With the Union of the Crowns in 1603, James VI inherited the thrones of England and Ireland and thus his arms in Scotland were now q ...

with the lower half of the lion removed and an arrow through the lion's mouth.

At Framlingham Castle

Framlingham Castle is a castle in the market town of Framlingham in Suffolk in England. An early motte and bailey or ringwork Norman castle was built on the Framlingham site by 1148, but this was destroyed (slighted) by Henry II of England in t ...

the Duke kept two silver-gilt cups engraved with the arms of James IV, which he bequeathed to Cardinal Wolsey

Thomas Wolsey ( – 29 November 1530) was an English statesman and Catholic bishop. When Henry VIII became King of England in 1509, Wolsey became the king's almoner. Wolsey's affairs prospered and by 1514 he had become the controlling figu ...

in 1524. The Duke's descendants presented the College of Arms

The College of Arms, or Heralds' College, is a royal corporation consisting of professional officers of arms, with jurisdiction over England, Wales, Northern Ireland and some Commonwealth realms. The heralds are appointed by the British Sover ...

with a sword, a dagger and a turquoise ring in 1681. The family tradition was either that these items belonged to James IV or were arms carried by Thomas Howard at Flodden. The sword blade is signed by the maker Maestre Domingo of Toledo. There is some doubt whether the weapons are of the correct period. The Earl of Arundel

Earl of Arundel is a title of nobility in England, and one of the oldest extant in the English peerage. It is currently held by the Duke of Norfolk, and is used (along with the Earl of Surrey) by his heir apparent as a courtesy title. The ...

was painted by Philip Fruytiers

Philip Fruytiers (1610–1666) was a Flemish Baroque painter and engraver. Until the 1960s, he was especially known for his miniature portraits in watercolor and gouache. Since then, several large canvases signed with the monogram PHF have be ...

, following Anthony van Dyck's 1639 composition, with his ancestor's sword, gauntlet and helm from Flodden. Thomas Lord Darcy retrieved a powder flask belonging to James IV and gave it to Henry VIII. A cross with rubies and sapphires with a gold chain worn by James and a hexagonal table-salt with the figure of St Andrews on the lid were given to Henry by James Stanley, Bishop of Ely

The Bishop of Ely is the Ordinary (officer), ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Ely in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese roughly covers the county of Cambridgeshire (with the exception of the Soke of Peterborough), together with ...

.

Legends of a lost king

Lord Dacre

Baron Dacre is a title that has been created three times in the Peerage of England, every time by writ.

History

The first creation came in 1321 when Ralph Dacre was summoned to Parliament as Lord Dacre. He married Margaret, 2nd Baroness Multo ...

discovered the body of James IV on the battlefield. He later wrote that the Scots "love me worst of any Englishman living, by reason that I fande the body of the King of Scots." The chronicle writer John Stow

John Stow (''also'' Stowe; 1524/25 – 5 April 1605) was an English historian and antiquarian. He wrote a series of chronicles of English history, published from 1565 onwards under such titles as ''The Summarie of Englyshe Chronicles'', ''The ...

gave a location for the King's death; "Pipard's Hill," now unknown, which may have been the small hill on Branxton Ridge overlooking Branxton church. Dacre took the body to Berwick-upon-Tweed, where according to Hall's ''Chronicle'', it was viewed by the captured Scottish courtiers William Scott and John Forman who acknowledged it was the King's. (Forman, the King's sergeant-porter, had been captured by Richard Assheton of Middleton.) The body was then embalmed and taken to Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is a ...

. From York

York is a cathedral city with Roman Britain, Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers River Ouse, Yorkshire, Ouse and River Foss, Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many hist ...

, a city that James had promised to capture before Michaelmas

Michaelmas ( ; also known as the Feast of Saints Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael, the Feast of the Archangels, or the Feast of Saint Michael and All Angels) is a Christian festival observed in some Western liturgical calendars on 29 September, a ...

, the body was brought to Sheen Priory near London. A payment of £12-9s-10d was made for the "sertying ledying and sawdryng of the ded course of the King of Scottes" and carrying it York and to Windsor.

James's banner, sword and his cuisses

Cuisses (; ; ) are a form of medieval armour worn to protect the thigh. The word is the plural of the French word ''cuisse'' meaning 'thigh'. While the skirt of a maille shirt or tassets of a cuirass could protect the upper legs from above, a thr ...

, thigh-armour, were taken to the shrine of Saint Cuthbert at Durham Cathedral. Much of the armour of the Scottish casualties was sold on the field, and 350 suits of armour were taken to Nottingham Castle

Nottingham Castle is a Stuart Restoration-era ducal mansion in Nottingham, England, built on the site of a Norman castle built starting in 1068, and added to extensively through the medieval period, when it was an important royal fortress an ...

. A list of horses taken at the field runs to 24 pages.

Thomas Hawley, the Rouge Croix pursuivant, was first with news of the victory. He brought the "rent surcoat of the King of Scots stained with blood" to Catherine of Aragon

Catherine of Aragon (also spelt as Katherine, ; 16 December 1485 – 7 January 1536) was Queen of England as the first wife of King Henry VIII from their marriage on 11 June 1509 until their annulment on 23 May 1533. She was previously ...

at Woburn Abbey

Woburn Abbey (), occupying the east of the village of Woburn, Bedfordshire, England, is a country house, the family seat of the Duke of Bedford. Although it is still a family home to the current duke, it is open on specified days to visitors ...

. She sent news of the victory to Henry VIII at Tournai