Barbadian History on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

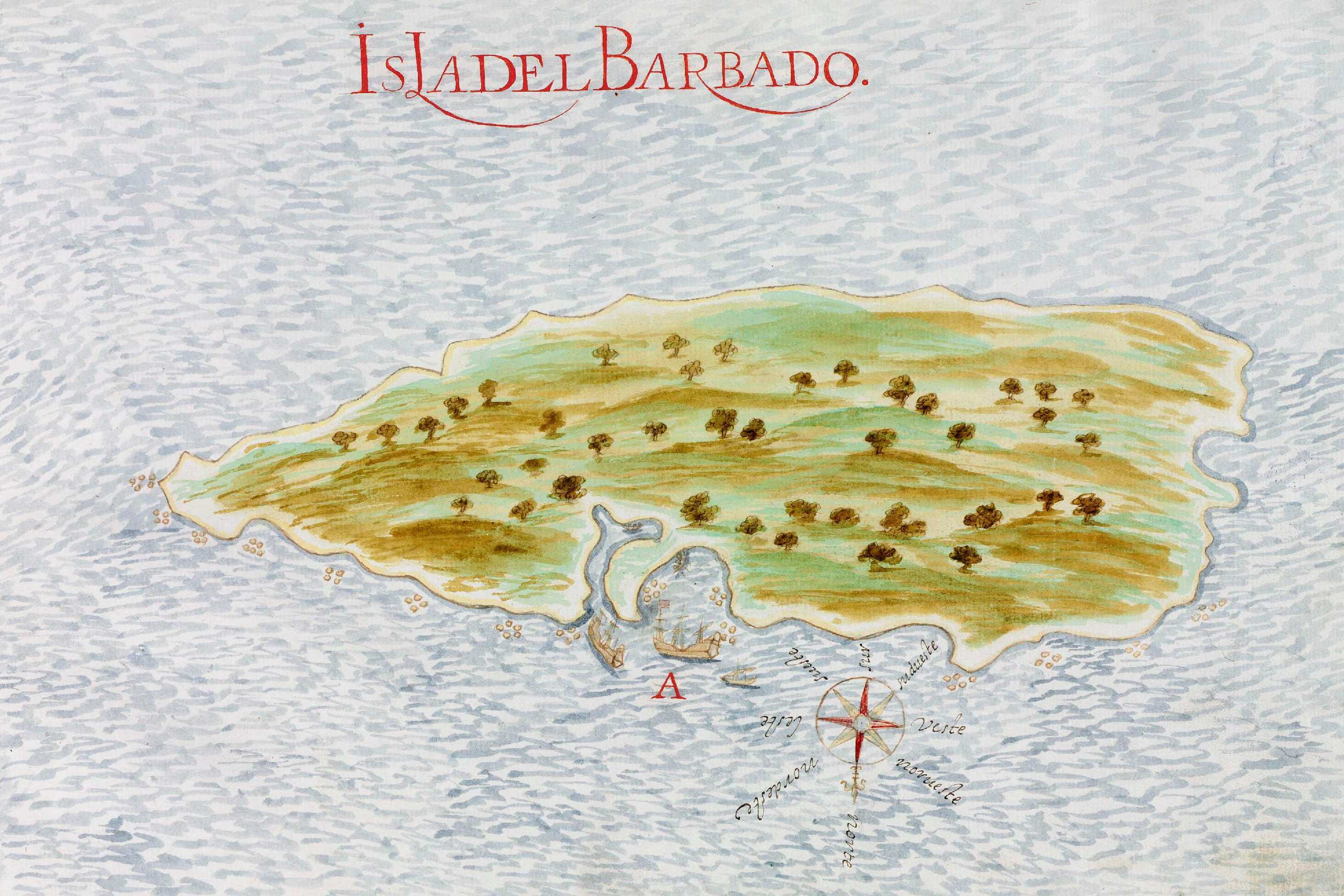

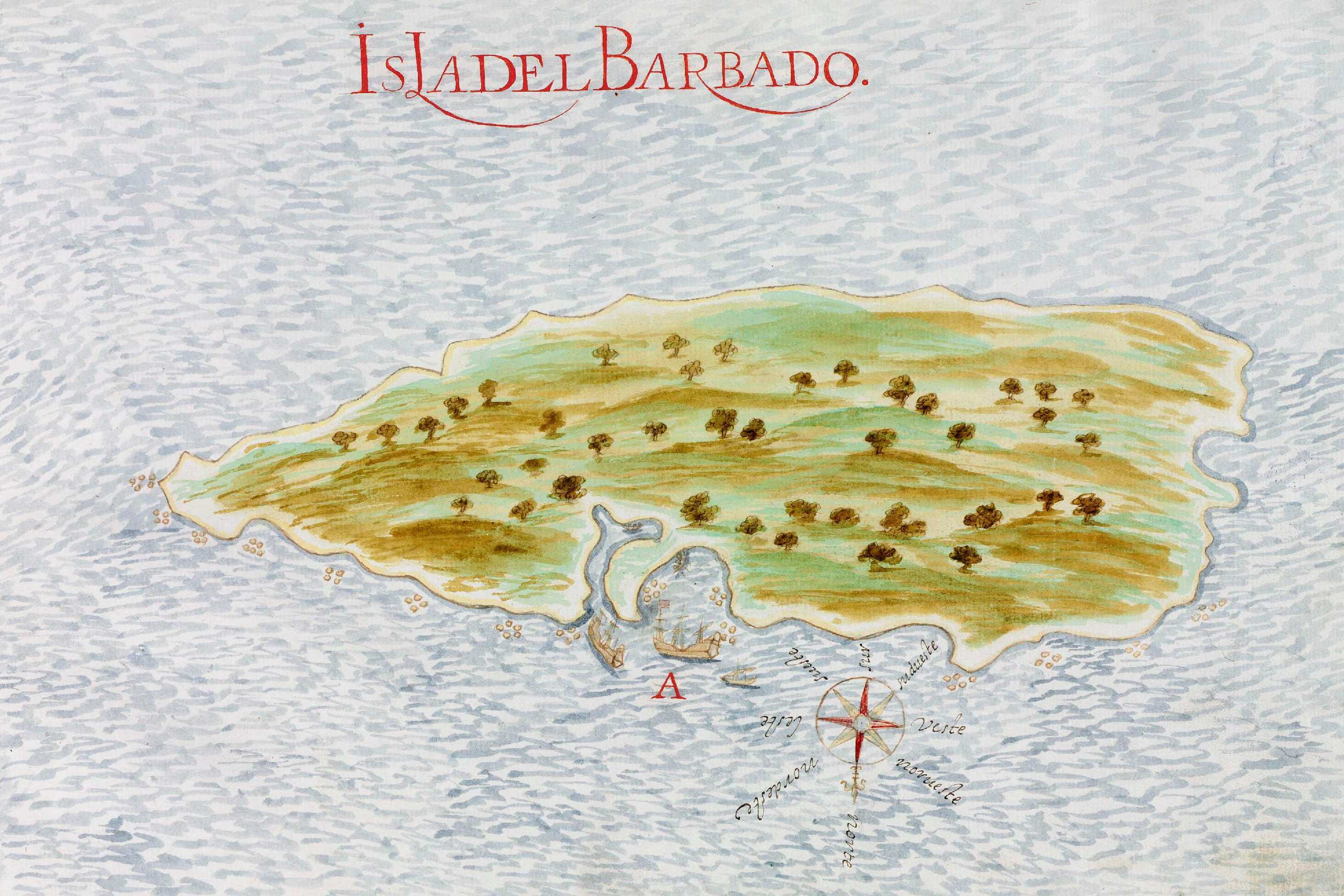

Barbados is an island country in the southeastern Caribbean Sea, situated about 100 miles (160 km) east of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. Roughly triangular in shape, the island measures some 21 miles (32 km) from northwest to southeast and about 14 miles (25 km) from east to west at its widest point. The capital and largest town is Bridgetown, which is also the main seaport.

Barbados was inhabited by its indigenous peoples – Arawaks and

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to discover the island. Portuguese navigator Pedro A. Campos named it ''Os Barbados'' (meaning "bearded ones").

Frequent slave-raiding missions by the Spanish Empire in the early 16th century led to a massive decline in the Amerindian population so that by 1541 a Spanish writer claimed they were uninhabited. The Amerindians were either captured for use as slaves by the Spanish or fled to other, more easily defensible mountainous islands nearby.

From about 1600 the English, French, and Dutch began to found colonies in the North American mainland and the smaller islands of the West Indies. Although Spanish and Portuguese sailors had visited Barbados, the first English ship touched the island on 14 May 1625, and England was the first European nation to establish a lasting settlement there from 1627, when the ''William and John'' arrived with more than 60 white settlers and six African slaves.

England is commonly said to have made its initial claim to Barbados in 1625, although reportedly an earlier claim may have been made in 1620. Nonetheless, Barbados was claimed from 1625 in the name of King James I of England. There were earlier English settlements in

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to discover the island. Portuguese navigator Pedro A. Campos named it ''Os Barbados'' (meaning "bearded ones").

Frequent slave-raiding missions by the Spanish Empire in the early 16th century led to a massive decline in the Amerindian population so that by 1541 a Spanish writer claimed they were uninhabited. The Amerindians were either captured for use as slaves by the Spanish or fled to other, more easily defensible mountainous islands nearby.

From about 1600 the English, French, and Dutch began to found colonies in the North American mainland and the smaller islands of the West Indies. Although Spanish and Portuguese sailors had visited Barbados, the first English ship touched the island on 14 May 1625, and England was the first European nation to establish a lasting settlement there from 1627, when the ''William and John'' arrived with more than 60 white settlers and six African slaves.

England is commonly said to have made its initial claim to Barbados in 1625, although reportedly an earlier claim may have been made in 1620. Nonetheless, Barbados was claimed from 1625 in the name of King James I of England. There were earlier English settlements in

The Civil War in Barbados

History in-depth, BBC, 5 November 2009. Willoughby rounded up and deported many Roundheads from Barbados, confiscating their property. To try to bring the recalcitrant colony to heel, the

Sugar cane cultivation in Barbados began in the 1640s, after its introduction in 1637 by Pieter Blower. Initially, rum was produced but by 1642,

Sugar cane cultivation in Barbados began in the 1640s, after its introduction in 1637 by Pieter Blower. Initially, rum was produced but by 1642,

The British abolished the slave trade in 1807, but not the institution itself. The abolition of slavery itself would only be enacted in 1833 in most parts of the British Empire.

In 1816, enslaved persons rose up in what was the first of three rebellions in the British West Indies to occur in the interval between the end of the slave trade and emancipation, and the largest slave uprising in the island's history. Around 20,000 enslaved persons from over 70 plantations are thought to have been involved. The rebellion was partly fuelled by information about the growing abolitionist movement in England, and the opposition against such by local whites.

The rebellion largely surprised planters, who felt that their slaves were content because they were allowed weekly dances, participated in social and economic activity across the island and were generally fed and looked after. However, they had refused to reform the Barbados Slave Code since its inception, a code that denied slaves human rights and prescribed inhumane torture, mutilation or death as a means of control. This contributed to what was later termed "Bussa's Rebellion", named after the slave ranger

The British abolished the slave trade in 1807, but not the institution itself. The abolition of slavery itself would only be enacted in 1833 in most parts of the British Empire.

In 1816, enslaved persons rose up in what was the first of three rebellions in the British West Indies to occur in the interval between the end of the slave trade and emancipation, and the largest slave uprising in the island's history. Around 20,000 enslaved persons from over 70 plantations are thought to have been involved. The rebellion was partly fuelled by information about the growing abolitionist movement in England, and the opposition against such by local whites.

The rebellion largely surprised planters, who felt that their slaves were content because they were allowed weekly dances, participated in social and economic activity across the island and were generally fed and looked after. However, they had refused to reform the Barbados Slave Code since its inception, a code that denied slaves human rights and prescribed inhumane torture, mutilation or death as a means of control. This contributed to what was later termed "Bussa's Rebellion", named after the slave ranger

Caribs

“Carib” may refer to:

People and languages

*Kalina people, or Caribs, an indigenous people of South America

**Carib language, also known as Kalina, the language of the South American Caribs

*Kalinago people, or Island Caribs, an indigenous pe ...

– prior to the European colonization of the Americas in the 16th century. Barbados was briefly claimed by the Spanish who saw the trees with the beard like feature (hence the name barbados), and then by Portugal from 1532 to 1620. The island was English and later a British colony from 1625 until 1966. From 1966 to 2021, it was a constitutional monarchy and parliamentary democracy, modelled on the Westminster system, with Elizabeth II, Queen of Barbados, as head of state. Barbados became a republic on November 30, 2021.

History before colonization

Some evidence suggests that Barbados may have been settled in the second millennium BC, but this is limited to fragments of conch lip adzes found in association with shells that have been radiocarbon-dated to about 1630 BC. Fully documented Amerindian settlement dates to between about 350 and 650 AD, when the Troumassoid people arrived. The arrivals were a group known as the Saladoid-Barrancoid from the mainland of South America. The second wave of settlers appeared around 800 AD (the Spanish referred to these as "Arawaks

The Arawak are a group of indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous peoples of northern South America and of the Caribbean. Specifically, the term "Arawak" has been applied at various times to the Lokono of South America and the Taíno, wh ...

") and a third in the mid-13th century. However, the Amerindian settlement surprisingly came to an end in the early 16th century. There's no evidence that the Kalinago (called "Caribs

“Carib” may refer to:

People and languages

*Kalina people, or Caribs, an indigenous people of South America

**Carib language, also known as Kalina, the language of the South American Caribs

*Kalinago people, or Island Caribs, an indigenous pe ...

" by the Spanish) ever established a permanent settlement in Barbados, though they often visited the island in their canoes.

Colonial history

Early colonial history

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to discover the island. Portuguese navigator Pedro A. Campos named it ''Os Barbados'' (meaning "bearded ones").

Frequent slave-raiding missions by the Spanish Empire in the early 16th century led to a massive decline in the Amerindian population so that by 1541 a Spanish writer claimed they were uninhabited. The Amerindians were either captured for use as slaves by the Spanish or fled to other, more easily defensible mountainous islands nearby.

From about 1600 the English, French, and Dutch began to found colonies in the North American mainland and the smaller islands of the West Indies. Although Spanish and Portuguese sailors had visited Barbados, the first English ship touched the island on 14 May 1625, and England was the first European nation to establish a lasting settlement there from 1627, when the ''William and John'' arrived with more than 60 white settlers and six African slaves.

England is commonly said to have made its initial claim to Barbados in 1625, although reportedly an earlier claim may have been made in 1620. Nonetheless, Barbados was claimed from 1625 in the name of King James I of England. There were earlier English settlements in

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to discover the island. Portuguese navigator Pedro A. Campos named it ''Os Barbados'' (meaning "bearded ones").

Frequent slave-raiding missions by the Spanish Empire in the early 16th century led to a massive decline in the Amerindian population so that by 1541 a Spanish writer claimed they were uninhabited. The Amerindians were either captured for use as slaves by the Spanish or fled to other, more easily defensible mountainous islands nearby.

From about 1600 the English, French, and Dutch began to found colonies in the North American mainland and the smaller islands of the West Indies. Although Spanish and Portuguese sailors had visited Barbados, the first English ship touched the island on 14 May 1625, and England was the first European nation to establish a lasting settlement there from 1627, when the ''William and John'' arrived with more than 60 white settlers and six African slaves.

England is commonly said to have made its initial claim to Barbados in 1625, although reportedly an earlier claim may have been made in 1620. Nonetheless, Barbados was claimed from 1625 in the name of King James I of England. There were earlier English settlements in The Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America, North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World. ...

(1607: Jamestown, 1609: Bermuda, and 1620: Plymouth Colony), and several islands in the Leeward Islands

french: Îles-Sous-le-Vent

, image_name =

, image_caption = ''Political'' Leeward Islands. Clockwise: Antigua and Barbuda, Guadeloupe, Saint kitts and Nevis.

, image_alt =

, locator_map =

, location = Caribbean SeaNorth Atlantic Ocean

, coor ...

were claimed by the English at about the same time as Barbados (1623: St Kitts, 1628: Nevis, 1632: Montserrat

Montserrat ( ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Caribbean. It is part of the Leeward Islands, the northern portion of the Lesser Antilles chain of the West Indies. Montserrat is about long and wide, with r ...

, 1632: Antigua

Antigua ( ), also known as Waladli or Wadadli by the native population, is an island in the Lesser Antilles. It is one of the Leeward Islands in the Caribbean region and the main island of the country of Antigua and Barbuda. Antigua and Bar ...

). Nevertheless, the Colony of Barbados quickly grew to become the third major English settlement in the Americas due to its prime eastern location.

Early English settlement

The settlement was established as a proprietary colony and funded by Sir William Courten, a City of London merchant who acquired the title to Barbados and several other islands. So the first colonists were actually tenants and much of the profits of their labor returned to Courten and his company. The first English ship, which had arrived on 14 May 1625, was captained by John Powell. The first settlement began on 17 February 1627, near what is nowHoletown

Holetown (UN/LOCODE: BB HLT), is a small city located in the Caribbean island nation of Barbados. Holetown is located in the parish of Saint James on the sheltered west coast of the island.

History

In 1625, Holetown (formerly as St. James Tow ...

(formerly Jamestown), by a group led by John Powell's younger brother, Henry, consisting of 80 settlers and 10 English laborers. The latter were young indentured laborers who according to some sources had been abducted, effectively making them slaves. About 40 Taino slaves were brought in from Guyana to help plant crops on the west coast of the island.Karl Watson, "A brief history of Barbados", ''Barbados'' (Hansib), Arif Ali (ed.), p. 44.

Courten's title was transferred to James Hay, 1st Earl of Carlisle, in what was called the "Great Barbados Robbery." Carlisle established a separate settlement at what he called Carlisle Bay, which later became known as Bridgetown.

Carlisle then chose as governor Henry Hawley

Henry Hawley (12 January 1685 – 24 March 1759) was a British army officer who served in the wars of the first half of the 18th century. He fought in a number of significant battles, including the Capture of Vigo in 1719, Dettingen, Fo ...

, who established the House of Assembly in 1639, in an effort to appease the planters, who might otherwise have opposed his controversial appointment. That year, 12 years after the settlement was established, the white adult population stood at an estimated 8,700.

In the period 1640–1660, the West Indies attracted over two-thirds of the total number of English emigrants to the Americas. By 1650, there were 44,000 settlers in the West Indies, as compared to 12,000 on the Chesapeake Chesapeake often refers to:

*Chesapeake people, a Native American tribe also known as the Chesepian

* The Chesapeake, a.k.a. Chesapeake Bay

*Delmarva Peninsula, also known as the Chesapeake Peninsula

Chesapeake may also refer to:

Populated plac ...

and 23,000 in New England.

Most English arrivals were indentured. After five years of labour, they were given "freedom dues" of about £10, usually in goods. Before the mid-1630s, they also received 5–10 acres of land, but after that time the island filled and there was no more free land. Around the time of Cromwell a number of rebels and criminals were also transported there.

Timothy Meads of Warwickshire was one of the rebels sent to Barbados at that time, before he received compensation for servitude of 1000 acres of land in North Carolina in 1666. Parish registers from the 1650s show, for the white population, four times as many deaths as marriages. The death rate was very high.

Before this, the mainstay of the infant colony's economy was the growing export of tobacco, but tobacco prices eventually fell in the 1630s, as Chesapeake production expanded.

England's civil war

Around the same time, fighting during the War of the Three Kingdoms and theInterregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one monarch and the next (coming from Latin '' ...

spilled over into Barbados and Barbadian territorial waters. The island was not involved in the war until after the execution of Charles I, when the island's government fell under the control of Royalists (ironically the Governor, Philip Bell, remained loyal to Parliament while the Barbadian House of Assembly of Barbados, under the influence of Humphrey Walrond, supported Charles II). On 7 May 1650, the General Assembly of Barbados voted to receive Lord Willoughby

Baron Willoughby of Parham was a title in the Peerage of England with two creations. The first creation was for Sir William Willoughby who was raised to the peerage under letters patent in 1547, with the remainder to his heirs male of body. A ...

as governor, a move which confirmed the Cavaliers as the government of Barbados.Hilary Beckles, "The 'Hub of Empire': The Caribbean and Britain in the Seventeenth Century", ''The Oxford History of the British Empire: Volume 1 The Origins of Empire'', ed. by Nicholas Canny (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), p. 238.Karl WatsonThe Civil War in Barbados

History in-depth, BBC, 5 November 2009. Willoughby rounded up and deported many Roundheads from Barbados, confiscating their property. To try to bring the recalcitrant colony to heel, the

Commonwealth Parliament

The Parliament of Australia (officially the Federal Parliament, also called the Commonwealth Parliament) is the legislative branch of the government of Australia. It consists of three elements: the monarch (represented by the governor-g ...

passed an act on 3 October 1650 prohibiting trade between England and Barbados, and because the island also traded with the Netherlands, further navigation acts were passed prohibiting any but English vessels trading with Dutch colonies. These acts were a precursor to the First Anglo-Dutch War.

The Commonwealth of England sent an invasion force under the command of Sir George Ayscue, which arrived in October 1651, and blockaded the island. After some skirmishing, the Royalists in the House of Assembly, feeling the pressures of commercial isolation, led by Lord Willoughby

Baron Willoughby of Parham was a title in the Peerage of England with two creations. The first creation was for Sir William Willoughby who was raised to the peerage under letters patent in 1547, with the remainder to his heirs male of body. A ...

surrendered. The conditions of the surrender were incorporated into the Charter of Barbados

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the rec ...

(Treaty of Oistins), which was signed at the Mermaid's Inn, Oistins

Oistins (Pronounced /'ȯis-tins/ -- UN/LOCODE: BB OST), is a coastal area located in the country of Barbados. It is situated centrally along the coastline of the parish of Christ Church. The area includes a fishing village as well as a tourist are ...

, on 17 January 1652.

Sugar cane and slavery

Sugar cane cultivation in Barbados began in the 1640s, after its introduction in 1637 by Pieter Blower. Initially, rum was produced but by 1642,

Sugar cane cultivation in Barbados began in the 1640s, after its introduction in 1637 by Pieter Blower. Initially, rum was produced but by 1642, sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Compound sugars, also called disaccharides or double ...

was the focus of the industry. As it developed into the main commercial enterprise, Barbados was divided into large plantation estates which replaced the small holdings of the early English settlers as the wealthy planters pushed out the poorer. Some of the displaced farmers relocated to the English colonies in North America, most notably South Carolina. To work the plantations, black Africans – primarily from West Africa – were imported as slaves in such numbers that there were three for every one planter. Increasingly after 1750 the plantations were owned by absentee landlords living in Britain and operated by hired managers. Persecuted Catholics from Ireland also worked the plantations. Life expectancy of slaves was short and replacements were purchased annually.

The introduction of sugar cane from Dutch Brazil in 1640 completely transformed society and the economy. Barbados eventually had one of the world's biggest sugar industries. One group instrumental in ensuring the early success of the industry were the Sephardic Jews, who had originally been expelled from the Iberian peninsula, to end up in Dutch Brazil. As the effects of the new crop increased, so did the shift in the ethnic composition of Barbados and surrounding islands. The workable sugar plantation required a large investment and a great deal of heavy labour. At first, Dutch traders supplied the equipment, financing, and African slaves, in addition to transporting most of the sugar to Europe. Barbados replaced Hispaniola as the main sugar producer in the Caribbean.

In 1655, the population of Barbados was estimated at 43,000, of which about 20,000 were of African descent, with the remainder mainly of English descent. These English smallholders were eventually bought out and the island filled up with large African slave-worked sugar plantations. By 1660, there was near parity with 27,000 blacks and 26,000 whites. By 1666, at least 12,000 white smallholders had been bought out, died, or left the island. Many of the remaining whites were increasingly poor. By 1673, black slaves (33,184) outnumbered white settlers (21,309). By 1680, there were 17 slaves for every indentured servant. By 1684, the disparity grew even further to 19,568 white settlers and 46,502 black slaves. By 1696, there was an estimated 42,000 enslaved blacks, and the white population declined further to 16,888 by 1715.

Due to the increased implementation of slave codes

The slave codes were laws relating to slavery and enslaved people, specifically regarding the Atlantic slave trade and chattel slavery in the Americas.

Most slave codes were concerned with the rights and duties of free people in regards to ensla ...

, which emphasized differential treatment between Africans, and the white workers and ruling planter class, the island became increasingly unattractive to poor whites

Poor White is a sociocultural classification used to describe economically disadvantaged Whites in the English-speaking world, especially White Americans with low incomes.

In the United States, Poor White (or Poor Whites of the South for ...

. Black or slave codes were implemented in 1661, 1676, 1682, and 1688. In response to these codes, several slave rebellions were attempted or planned during this time, but none succeeded. Nevertheless, poor whites who had or acquired the means to emigrate often did so. Planters expanded their importation of African slaves to cultivate sugar cane. One early advocate of slave rights in Barbados was the visiting Quaker preacher Alice Curwen

Alice Curwen (c. 1619–1679) was an English Quaker missionary, who wrote an autobiography published along with correspondence as part of ''A Relation of the Labour, Travail and Suffering of that Faithful Servant of the Lord, Alice Curwen'' (168 ...

in 1677: "For I am persuaded, that if they whom thou call'st thy Slaves, be Upright-hearted to God, the Lord God Almighty will set them Free in a way that thou knowest not; for there is none set free but in Christ Jesus, for all other Freedom will prove but a Bondage."

By 1660, Barbados generated more trade than all the other English colonies combined. This remained so until it was eventually surpassed by geographically larger islands like Jamaica in 1713. But even so, the estimated value of the Colony of Barbados in 1730–1731 was as much as £5,500,000. Bridgetown, the capital, was one of the three largest cities in English America (the other two being Boston, Massachusetts and Port Royal, Jamaica.) By 1700, the English West Indies produced 25,000 tons of sugar, compared to 20,000 for Brazil, 10,000 for the French islands and 4,000 for the Dutch islands. This quickly replaced tobacco, which had been the island's main export.

As the sugar industry developed into its main commercial enterprise, Barbados was divided into large plantation estates that replaced the smallholdings of the early English settlers. In 1680, over half the arable land was held by 175 large planters, each of whom used at least 60 slaves. The great plantation ownershad connections with the English aristocracy and great influence on Parliament. (In 1668, the West Indian sugar crop sold for £180,000 after customs of £18,000. Chesapeake tobacco earned £50,000 after customs of £75,000).

So much land was devoted to sugar that most foods had to be imported from New England. The poorer whites who were moved off the island went to the English Leeward Islands, or especially to Jamaica. In 1670, the Province of South Carolina was founded, when some of the surplus population again left Barbados. Other nations receiving large numbers of Barbadians included British Guiana

British Guiana was a British colony, part of the mainland British West Indies, which resides on the northern coast of South America. Since 1966 it has been known as the independent nation of Guyana.

The first European to encounter Guiana was S ...

and Panama.

Roberts (2006) shows that enslaved persons did not spend the majority of time in restricted roles cultivating, harvesting and processing sugar cane, the island's most important cash crop. Rather, the enslaved were involved in various activities and in multiple roles: raising livestock, fertilizing soil, growing provisional crops, maintaining plantation infrastructure, caregiving and other tasks. One notable soil management technique was intercropping, planting subsistence crops between the rows of cash crops, which demanded of the enslaved skilled and experienced observations of growing conditions for efficient land use.

"Slaveholders often counted as "married" only the enslaved with mates on the estate. For example, the manager of Newton estate... recorded 20 women with co-resident husbands and 35 with mates elsewhere. Members of the latter group were labelled single, members of extended units, or mother-child units."

By 1750, there were about 18,000 white settlers, compared to approximately 65,000 African slaves.

The slave trade ceased in 1807 and slaves were emancipated in 1834.

Bussa's rebellion

The British abolished the slave trade in 1807, but not the institution itself. The abolition of slavery itself would only be enacted in 1833 in most parts of the British Empire.

In 1816, enslaved persons rose up in what was the first of three rebellions in the British West Indies to occur in the interval between the end of the slave trade and emancipation, and the largest slave uprising in the island's history. Around 20,000 enslaved persons from over 70 plantations are thought to have been involved. The rebellion was partly fuelled by information about the growing abolitionist movement in England, and the opposition against such by local whites.

The rebellion largely surprised planters, who felt that their slaves were content because they were allowed weekly dances, participated in social and economic activity across the island and were generally fed and looked after. However, they had refused to reform the Barbados Slave Code since its inception, a code that denied slaves human rights and prescribed inhumane torture, mutilation or death as a means of control. This contributed to what was later termed "Bussa's Rebellion", named after the slave ranger

The British abolished the slave trade in 1807, but not the institution itself. The abolition of slavery itself would only be enacted in 1833 in most parts of the British Empire.

In 1816, enslaved persons rose up in what was the first of three rebellions in the British West Indies to occur in the interval between the end of the slave trade and emancipation, and the largest slave uprising in the island's history. Around 20,000 enslaved persons from over 70 plantations are thought to have been involved. The rebellion was partly fuelled by information about the growing abolitionist movement in England, and the opposition against such by local whites.

The rebellion largely surprised planters, who felt that their slaves were content because they were allowed weekly dances, participated in social and economic activity across the island and were generally fed and looked after. However, they had refused to reform the Barbados Slave Code since its inception, a code that denied slaves human rights and prescribed inhumane torture, mutilation or death as a means of control. This contributed to what was later termed "Bussa's Rebellion", named after the slave ranger Bussa

Bussa's rebellion (14–16 April 1816) was the largest slave revolt in Barbadian history. The rebellion takes its name from the African-born slave, Bussa, who led the rebellion. The rebellion, which was eventually defeated by the colonial mili ...

, and the result of a growing sentiment that the treatment of slaves in Barbados was "intolerable", and who believed the political climate in Britain made the time ripe to peacefully negotiate with planters for freedom. Bussa became the most famous of the rebellion's organizers, many of whom were either enslaved persons of some higher position or literate freedmen. One woman, Nanny Grigg, is also named as a principal organizer.

However, the rebellion eventually failed. The uprising was triggered prematurely, but the slaves were already greatly outmatched. Barbados' flat terrain gave the horses of the better-armed militia the clear advantage over the rebels, with no mountains or forest for concealment. Slaves had also thought they would be supported by freed men of colour, but these instead joined efforts to quell the rebellion. Although they drove whites off the plantations, widespread killings did not take place. By the end, 120 slaves died in combat or were immediately executed and another 144 brought to trial and executed. The remaining rebels were shipped off the island.

Towards the abolition of slavery

In 1826, the Barbados legislature passed theConsolidated Slave Law

The Consolidated Slave Law was a law which was enacted by the Barbados legislature in 1826. Following Bussa's Rebellion, London officials were concerned about further risk of revolts and instituted a policy of amelioration. This was resisted by ...

, which simultaneously granted concessions to the slaves while providing reassurances to the slave owners.

Slavery was finally abolished in the British Empire eight years later, in 1834. In Barbados and the rest of the British West Indian colonies, full emancipation from slavery was preceded by a contentious apprenticeship period that lasted four years.

In 1884, the Barbados Agricultural Society sent a letter to Sir Francis Hincks

Sir Francis Hincks, (December 14, 1807 – August 18, 1885) was a Canadian businessman, politician, and British colonial administrator. An immigrant from Ireland, he was the Co-Premier of the Province of Canada (1851–1854), Governor of Barb ...

requesting his private and public views on whether the Dominion of Canada would favourably entertain having the then Colony of Barbados admitted as a member of the Canadian Confederation. Asked from Canada were the terms of the Canadian side to initiate discussions, and whether or not the island of Barbados could depend on the full influence of Canada in getting the change agreed to by the British Parliament at Westminster.

Towards decolonisation

In 1952, the '' Barbados Advocate'' newspaper polled several prominent Barbadian politicians, lawyers, businessmen, the Speaker of the House of Assembly and later as first President of theSenate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, Sir Theodore Branker, Q.C.and found them to be in favour of immediate federation of Barbados along with the rest of the British Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

with complete Dominion Status within five years from the date of inauguration of the West Indies Federation with Canada.

However, plantation owners and merchants of British descent still dominated local politics, owing to the high income qualification required for voting. More than 70 per cent of the population, many of them disenfranchised women, were excluded from the democratic process. It was not until the 1930s that the descendants of emancipated slaves began a movement for political rights. One of the leaders of this, Sir Grantley Adams

Sir Grantley Herbert Adams, CMG, QC (28 April 1898 – 28 November 1971) was a Barbadian politician. He served as the inaugural premier of Barbados from 1953 to 1958 and then became the first and only prime minister of the West Indies Federa ...

, founded the Barbados Progressive League in 1938, which later became known as the Barbados Labour Party (BLP).

Adams and his party demanded more rights for the poor and for the people, and staunchly supported the monarchy. Progress toward a more democratic government in Barbados was made in 1942, when the exclusive income qualification was lowered and women were given the right to vote. By 1949, governmental control was wrested from the planters, and in 1953 Adams became Premier of Barbados.

From 1958 to 1962, Barbados was one of the ten members of the West Indies Federation, a federalist organisation doomed by nationalist attitudes and the fact that its members, as British colonies, held limited legislative power. Grantley Adams

Sir Grantley Herbert Adams, CMG, QC (28 April 1898 – 28 November 1971) was a Barbadian politician. He served as the inaugural premier of Barbados from 1953 to 1958 and then became the first and only prime minister of the West Indies Federa ...

served as its first and only "Premier", but his leadership failed in attempts to form similar unions, and his continued defence of the monarchy was used by his opponents as evidence that he was no longer in touch with the needs of his country. Errol Walton Barrow

Errol Walton Barrow (21 January 1920 – 1 June 1987) was a Barbadian statesman and the first prime minister of Barbados. Born into a family of political and civic activists in the parish of Saint Lucy, he became a WWII aviator, combat vete ...

, a fervent reformer, became the people's new advocate. Barrow had left the BLP and formed the Democratic Labour Party (DLP) as a liberal alternative to Adams' conservative government. Barrow instituted many progressive social programmes, such as free education for all Barbadians and a school meals system. By 1961, Barrow had replaced Adams as Premier and the DLP controlled the government.

With the Federation dissolved, Barbados reverted to its former status, that of a self-governing colony. The island negotiated its own independence at a constitutional conference with Britain in June 1966. After years of peaceful and democratic progress, Barbados finally became an independent state on 30 November 1966, with Errol Barrow its first Prime Minister, although Queen Elizabeth II remained the monarch. Upon independence Barbados maintained historical linkages with Britain by becoming a member of the Commonwealth of Nations. A year later, Barbados' international linkages were expanded by obtaining membership of both the United Nations and the Organization of American States

The Organization of American States (OAS; es, Organización de los Estados Americanos, pt, Organização dos Estados Americanos, french: Organisation des États américains; ''OEA'') is an international organization that was founded on 30 April ...

.

Political history

Carrington (1982) examines politics during the American Revolution, revealing that Barbadian political leaders shared many of the grievances and goals of the American revolutionaries, but that they were unwilling to go to war over them. Nevertheless, the repeated conflicts between the island assembly and the royal governors brought important constitutional reforms which confirmed the legislature's control over most local matters and its power over the executive. From 1800 until 1885, Barbados then served as the main seat of Government for the former British colonies of the Windward Islands. During that period of around 85 years, the resident Governor of Barbados also served as the Colonial head of the Windward Islands. After the Government of Barbados officially exited from the Windward Island union in 1885, the seat was moved from Bridgetown to St. George's on the neighbouring island ofGrenada

Grenada ( ; Grenadian Creole French: ) is an island country in the West Indies in the Caribbean Sea at the southern end of the Grenadines island chain. Grenada consists of the island of Grenada itself, two smaller islands, Carriacou and Pe ...

, where it remained until the territory of the Windward Islands was dissolved.

Soon after Barbados' withdrawal from the Windward Islands, Barbados became aware that Tobago was going to be amalgamated with another territory as part of a single state. In response, Barbados made an official bid to the British Government to have neighbouring Island Tobago joined with Barbados in a political union. The British government however decided that Trinidad would be a better fit and Tobago instead was made a Ward of Trinidad.

African slaves worked on plantations owned by merchants of English and Scottish descent. It was these merchants who continued to dominate Barbados politics, even after emancipation, due to a high income restriction on voting. Only the upper 30 per cent had any voice in the democratic process. It was not until the 1930s that a movement for political rights was begun by the descendants of emancipated slaves, who started trade unions. Charles Duncan O’Neal

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was " ...

, Clennell Wickham

Clennell Wilsden Wickham (21 September 1895 – 6 October 1938) was a radical West Indian journalist, editor of Barbadian newspaper ''The Herald'' and champion of black, working-class causes against the white planter oligarchy in colonial Barbado ...

and the members of the Democratic League were some of the leaders of this movement. This was initially opposed by Sir Grantley Adams

Sir Grantley Herbert Adams, CMG, QC (28 April 1898 – 28 November 1971) was a Barbadian politician. He served as the inaugural premier of Barbados from 1953 to 1958 and then became the first and only prime minister of the West Indies Federa ...

, who played an instrumental role in the bankruptcy and shutdown of ''The Herald'' newspapers, one of the movement's foremost voices. Adams would later found the Barbados Progressive League (now the Barbados Labour Party) in 1938, during the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

. The Depression caused mass unemployment and strikes

Strike may refer to:

People

*Strike (surname)

Physical confrontation or removal

*Strike (attack), attack with an inanimate object or a part of the human body intended to cause harm

*Airstrike, military strike by air forces on either a suspected ...

, and the standard of living

Standard of living is the level of income, comforts and services available, generally applied to a society or location, rather than to an individual. Standard of living is relevant because it is considered to contribute to an individual's quality ...

on the island fell drastically. With the death of O’Neal and the demise of the League, Adams cemented his power, but he used this to advocate for causes that had once been his rivals, including more help for the people especially the poor.

Finally, in 1942, the income qualification was lowered. This was followed by the introduction of universal adult suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally i ...

in 1951, and Adams was elected as Premier of Barbados in 1958. For his action and leadership, Adams would later become a National Hero

The title of Hero is presented by various governments in recognition of acts of self-sacrifice to the state, and great achievements in combat or labor. It is originally a Soviet-type honor, and is continued by several nations including Belarus, Ru ...

.

From 1958 to 1962, Barbados was one of the ten members of the West Indies Federation, an organisation doomed to failure by a number of factors, including what were often petty nationalistic prejudices and limited legislative power. Indeed, Adams's position as "Prime Minister" was a misnomer, as all of the Federation members were still colonies of Britain. Adams, once a political visionary and now a man whose policies seemed to some blind to the needs of his country, not only held fast to his notion of defending the monarchy but also made additional attempts to form other Federation-like entities after that union's demise. When the Federation was terminated, Barbados reverted to its former status as a self-governing colony, but efforts were made by Adams to form another federation composed of Barbados and the Leeward and Windward Islands.

Errol Walton Barrow

Errol Walton Barrow (21 January 1920 – 1 June 1987) was a Barbadian statesman and the first prime minister of Barbados. Born into a family of political and civic activists in the parish of Saint Lucy, he became a WWII aviator, combat vete ...

was to replace Grantley Adams as the advocate of populism, and it was he who would eventually lead the island into Independence in 1966. Barrow, a fervent reformer and once a member of the Barbados Labour Party, had left the party to form his own Democratic Labour Party, as the liberal alternative to the conservative BLP government under Adams. He remains a National Hero

The title of Hero is presented by various governments in recognition of acts of self-sacrifice to the state, and great achievements in combat or labor. It is originally a Soviet-type honor, and is continued by several nations including Belarus, Ru ...

for his work in social reformation, including the institution of free education for all Barbadians. In 1961, Barrow supplanted Adams as Premier as the DLP took control of the government.

Independence

Due to several years of growing autonomy, Barbados, with Barrow at the helm, was able successfully to negotiate its independence at a constitutional conference with the United Kingdom in June 1966. After years of peaceful and democratic progress, Barbados finally became an independent state and formally joined the Commonwealth of Nations on 30 November 1966, Errol Barrow serving as its first Prime Minister. The Barrow government sought to diversify the economy away from agriculture, seeking to boost industry and the tourism sector. Barbados was also at the forefront of regional integration efforts, spearheading the creation ofCARIFTA

The Caribbean Free Trade Association (CARIFTA) was organised on 1 May 1968, to provide a continued economic linkage between the English-speaking countries of the Caribbean. The agreements establishing it came following the dissolution of the ...

and CARICOM. The DLP lost the 1976 Barbadian general election

General elections were held in Barbados on 2 September 1976.Nohlen, D (2005) ''Elections in the Americas: A data handbook, Volume I'', p90 The result was a victory for the Barbados Labour Party, which won 17 of the 24 seats, defeating the rulin ...

to the BLP under Tom Adams. Adams adopted a more conservative and strongly pro-Western stance, allowing the Americans to use Barbados as the launchpad for their invasion of Grenada

The United States invasion of Grenada began at dawn on 25 October 1983. The United States and a coalition of six Caribbean nations invaded the island nation of Grenada, north of Venezuela. Codenamed Operation Urgent Fury by the U.S. military, ...

in 1983. Adams died in office in 1985 and was replaced by Harold Bernard St. John

Sir Harold Bernard St. John, KA (16 August 1931 – 29 February 2004) was a Barbadian politician who served as the third prime minister of Barbados from 1985 to 1986. To date, he is the shortest serving Barbadian prime minister. He was leader of ...

; however, St. John lost the 1986 Barbadian general election

General elections were held in Barbados on 28 May 1986. Dieter Nohlen (2005) ''Elections in the Americas: A data handbook, Volume I'', p90 The result was a landslide victory for the Democratic Labour Party, which won 24 of the 27 seats. Among ...

, which saw the return of the DLP under Errol Barrow, who had been highly critical of the US intervention in Grenada. Barrow, too, died in office, and was replaced by Lloyd Erskine Sandiford

Sir Lloyd Erskine Sandiford, KA, PC (born 24 March 1937) is a Barbadian politician. He served as the fourth prime minister of Barbados from 1987 to 1994. Later Sir Lloyd served as Barbados' first resident ambassador in Beijing, China from 20 ...

, who remained Prime Minister until 1994.

Owen Arthur of the BLP won the 1994 Barbadian general election

Early general elections were held in Barbados on 6 September 1994.Dieter Nohlen (2005) ''Elections in the Americas: A data handbook, Volume I'', p90 The result was a victory for the opposition Barbados Labour Party, which won 19 of the 28 seats, ...

, remaining Prime Minister until 2008.Dieter Nohlen

Dieter Nohlen (born 6 November 1939) is a German academic and political scientist. He currently holds the position of Emeritus Professor of Political Science in the Faculty of Economic and Social Sciences of the University of Heidelberg. An expe ...

(2005) ''Elections in the Americas: A data handbook, Volume I'', p90 Arthur was a strong advocate of republicanism, though a planned referendum to replace Queen Elizabeth as Head of State in 2008 never took place. The DLP won the 2008 Barbadian general election

General elections were held in Barbados on 15 January 2008.David Thompson died in 2010 and was replaced by

in JSTOR

* Blackman, Francis W., ''National Heroine of Barbados: Sarah Ann Gill'' (Barbados: Methodist Church, 1998, 27 pp.) *Blackman, Francis W., ''Methodism, 200 years in Barbados'' (Barbados: Caribbean Contact, 1988, 160 pp.) *Butler, Kathleen Mary. ''The Economics of Emancipation: Jamaica & Barbados, 1823–1843'' (1995)

online edition

*Dunn, Richard S., "The Barbados Census of 1680: Profile of the Richest Colony in English America", ''William and Mary Quarterly,'' vol. 26, no. 1 (January 1969), pp. 3–30

in JSTOR.

*Harlow, V. T. ''A History of Barbados'' (1926). *Michener, James, A. 1989. ''Caribbean''. Secker & Warburg. London. . Especially see Chapter V., "Big Storms in Little England", pp. 140–172; popular writer *Kurlansky, Mark. 1992. ''A Continent of Islands: Searching for the Caribbean Destiny''. Addison-Wesley Publishing. . *Howe, Glenford D., and Don D. Marshall, eds. ''The Empowering Impulse: The Nationalist Tradition of Barbados'' (Canoe Press, 2001

online edition

*Molen, Patricia A. "Population and Social Patterns in Barbados in the Early Eighteenth Century," ''William and Mary Quarterly,'' Vol. 28, No. 2 (April 1971), pp. 287–30

in JSTOR

* * * *Richardson; Bonham C. ''Economy and Environment in the Caribbean: Barbados and the Windwards in the Late 1800s'' (The University of the West Indies Press, 1997

online edition

*Ragatz, Lowell Joseph. "Absentee Landlordism in the British Caribbean, 1750–1833", ''Agricultural History,'' Vol. 5, No. 1 (January 1931), pp. 7–2

in JSTOR

* * *Sheridan; Richard B. ''Sugar and Slavery: An Economic History of the British West Indies, 1623–1775'' (University of the West Indies Press, 1994

online edition

*Starkey, Otis P. ''The Economic Geography of Barbados'' (1939). *Thomas, Robert Paul. "The Sugar Colonies of the Old Empire: Profit or Loss for Great Britain?" ''Economic History Review'', Vol. 21, No. 1 (April 1968), pp. 30–4

in JSTOR

– Government of Barbados

Barbados Museum & Historical Society

Government Information Services, Government of Barbados

List of rulers for Barbados *Watson, Karl

The Civil War in Barbados

BBC History, 2001-04-01.

* ttp://www.brown.edu/Research/Slavery_Justice/documents/SlaveryAndJustice.pdf Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Barbados Barbados, History Barbados Barbados

Freundel Stuart

Freundel Jerome Stuart, OR, PC, SC (born 27 April 1951) is a Barbadian politician who served as seventh Prime Minister of Barbados and the leader of the Democratic Labour Party (DLP) from 23 October 2010 to 21 February 2013; and from 21 Febr ...

. The BLP returned to power in 2018 under Mia Mottley

Mia Amor Mottley, (born 1 October 1965) is a Barbadian politician and attorney who has served as the eighth prime minister of Barbados since 2018 and as Leader of the Barbados Labour Party (BLP) since 2008. Mottley is the first woman to hold ...

, who became Barbados's first female Prime Minister.

Transition to republic

The Government of Barbados announced on 15 September 2020 that it intended to become a republic by 30 November 2021, the 55th anniversary of its independence resulting in the replacement of the hereditary monarch of Barbados with an elected president. Barbados would then cease to be aCommonwealth realm

A Commonwealth realm is a sovereign state in the Commonwealth of Nations whose monarch and head of state is shared among the other realms. Each realm functions as an independent state, equal with the other realms and nations of the Commonwealt ...

, but could maintain membership in the Commonwealth of Nations, like Guyana

Guyana ( or ), officially the Cooperative Republic of Guyana, is a country on the northern mainland of South America. Guyana is an indigenous word which means "Land of Many Waters". The capital city is Georgetown. Guyana is bordered by the ...

and Trinidad and Tobago.

On 20 September 2021, just over a full year after the announcement for the transition was made, the Constitution (Amendment) (No. 2) Bill, 2021 was introduced to the Parliament of Barbados. Passed on 6 October, the Bill made amendments to the Constitution of Barbados, introducing the office of the President of Barbados

The president of Barbados is the head of state of Barbados and the commander-in-chief of the Barbados Defence Force. The office was established when the country became a parliamentary republic on 30 November 2021. Before, the head of state was ...

to replace the role of Elizabeth II, Queen of Barbados. The following week, on 12 October 2021, incumbent Governor-General of Barbados

The governor-general of Barbados was the representative of the Barbadian monarch from independence in 1966 until the establishment of a republic in 2021. Under the government's Table of Precedence for Barbados, the governor-general of Barbados ...

Sandra Mason was jointly nominated by the Prime Minister and Leader of the Opposition as candidate to be the first President of Barbados

The president of Barbados is the head of state of Barbados and the commander-in-chief of the Barbados Defence Force. The office was established when the country became a parliamentary republic on 30 November 2021. Before, the head of state was ...

, and was subsequently elected on 20 October. Mason took office on 30 November 2021. Prince Charles

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person to ...

, who was heir apparent to the Barbadian Crown, attended the swearing-in ceremony in Bridgetown at the invitation of the Government of Barbados.

Queen Elizabeth II sent a message of congratulations to President Mason and the people of Barbados, saying: "As you celebrate this momentous day, I send you and all Barbadians my warmest good wishes for your happiness, peace and prosperity in the future."

A survey was taken between October 23, 2021, and November 10, 2021, by the University of the West Indies

The University of the West Indies (UWI), originally University College of the West Indies, is a public university system established to serve the higher education needs of the residents of 17 English-speaking countries and territories in th ...

that showed 34% of respondents being in favour of transitioning to a republic, while 30% were indifferent. Notably, no overall majority was found in the survey; with 24% not indicating a preference, and the remaining 12% being opposed to the removal of Queen Elizabeth.

In January 2022, Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley’s Labor Party got a landslide victory, winning all 30 legislative seats, in the first general election since Barbados became a republic.

Confederations and union proposals

A number of proposals have been mooted in the past to integrate Barbados into neighbouring countries or even the Canadian Confederation. To date all have failed, and one proposal led to deadly riots in 1876, when Governor John Pope Hennessy tried to pressure Barbadian politicians to integrate more firmly into the Windward Islands. Governor Hennessy was quickly transferred from Barbados by the British Crown. In 1884, attempts were then made by the influential Barbados Agricultural Society to have Barbados form a political association with the Canadian Confederation. From 1958 to 1962 Barbados became one of the ten states of the West Indies Federation. Lastly in the 1990s, a plan was devised by the leaders of Guyana, Barbados, and Trinidad and Tobago to form a political association between those three governments. Again this deal was never completed, following the loss of Sir Lloyd Erskine Sandiford in the Barbadian general elections.See also

*Military history of Barbados

The military history of Barbados comprises hundreds of years of military activity on the island of Barbados, as well as international military and peacekeeping operations in which Barbadians took part.

Colonial history

Throughout the colonial hist ...

*British colonization of the Americas

The British colonization of the Americas was the history of establishment of control, settlement, and colonization of the continents of the Americas by England, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. C ...

* French colonization of the Americas

* History of the Americas

* History of North America

*History of the British West Indies

The term British West Indies refers to the former English and British colonies and the present-day overseas territories of the United Kingdom in the Caribbean.

In the history of the British West Indies there have been several attempts at poli ...

* List of prime ministers of Barbados

* List of governors of Barbados

* Longitude

* Piracy in the Caribbean

*Politics of Barbados

The politics of Barbados function within a framework of a parliamentary republic with strong democratic traditions; constitutional safeguards for nationals of Barbados include: freedom of speech, press, worship, movement, and association.

Execut ...

*Spanish colonization of the Americas

Spain began colonizing the Americas under the Crown of Castile and was spearheaded by the Spanish . The Americas were invaded and incorporated into the Spanish Empire, with the exception of Brazil, British America, and some small regions ...

*Timeline of Barbadian history

This is a timeline of Barbadian history, comprising important legal and territorial changes and political events in Barbados and its predecessor states. To read about the background to these events, see History of Barbados and History of the Ca ...

* West Indies Federation

Notes

Citations

References

* * *Hoyes, F. A. 1963. ''The Rise of West Indian Democracy: The Life and Times of Sir Grantley Adams''. Advocate Press. *Williams, Eric. 1964. ''British Historians and the West Indies''. P.N.M. Publishing Company, Port-of-Spain. *Scott, Caroline. 1999. ''Insight Guide Barbados''. Discovery Channel and Insight Guides; fourth edition, Singapore.Further reading

* Beckles, Hilary McD., and Andrew Downes. "The Economics of Transition to the Black Labor System in Barbados, 1630–1680," ''Journal of Interdisciplinary History,'' Vol. 18, No. 2 (Autumn 1987), pp. 225–247in JSTOR

* Blackman, Francis W., ''National Heroine of Barbados: Sarah Ann Gill'' (Barbados: Methodist Church, 1998, 27 pp.) *Blackman, Francis W., ''Methodism, 200 years in Barbados'' (Barbados: Caribbean Contact, 1988, 160 pp.) *Butler, Kathleen Mary. ''The Economics of Emancipation: Jamaica & Barbados, 1823–1843'' (1995)

online edition

*Dunn, Richard S., "The Barbados Census of 1680: Profile of the Richest Colony in English America", ''William and Mary Quarterly,'' vol. 26, no. 1 (January 1969), pp. 3–30

in JSTOR.

*Harlow, V. T. ''A History of Barbados'' (1926). *Michener, James, A. 1989. ''Caribbean''. Secker & Warburg. London. . Especially see Chapter V., "Big Storms in Little England", pp. 140–172; popular writer *Kurlansky, Mark. 1992. ''A Continent of Islands: Searching for the Caribbean Destiny''. Addison-Wesley Publishing. . *Howe, Glenford D., and Don D. Marshall, eds. ''The Empowering Impulse: The Nationalist Tradition of Barbados'' (Canoe Press, 2001

online edition

*Molen, Patricia A. "Population and Social Patterns in Barbados in the Early Eighteenth Century," ''William and Mary Quarterly,'' Vol. 28, No. 2 (April 1971), pp. 287–30

in JSTOR

* * * *Richardson; Bonham C. ''Economy and Environment in the Caribbean: Barbados and the Windwards in the Late 1800s'' (The University of the West Indies Press, 1997

online edition

*Ragatz, Lowell Joseph. "Absentee Landlordism in the British Caribbean, 1750–1833", ''Agricultural History,'' Vol. 5, No. 1 (January 1931), pp. 7–2

in JSTOR

* * *Sheridan; Richard B. ''Sugar and Slavery: An Economic History of the British West Indies, 1623–1775'' (University of the West Indies Press, 1994

online edition

*Starkey, Otis P. ''The Economic Geography of Barbados'' (1939). *Thomas, Robert Paul. "The Sugar Colonies of the Old Empire: Profit or Loss for Great Britain?" ''Economic History Review'', Vol. 21, No. 1 (April 1968), pp. 30–4

in JSTOR

External links

– Government of Barbados

Government Information Services, Government of Barbados

List of rulers for Barbados *Watson, Karl

The Civil War in Barbados

BBC History, 2001-04-01.

* ttp://www.brown.edu/Research/Slavery_Justice/documents/SlaveryAndJustice.pdf Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Barbados Barbados, History Barbados Barbados