Bank Of England (Election Of Directors) Act 1872 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Bank of England is the

In 1700, the

In 1700, the

In 1825–26 the bank was able to avert a liquidity crisis when

In 1825–26 the bank was able to avert a liquidity crisis when

In 1977 the Bank set up a wholly owned subsidiary called Bank of England Nominees Limited (BOEN), a now-defunct private limited company, with two of its hundred £1 shares issued. According to its memorandum of association, its objectives were: "To act as Nominee or agent or attorney either solely or jointly with others, for any person or persons, partnership, company, corporation, government, state, organisation, sovereign, province, authority, or public body, or any group or association of them". Bank of England Nominees Limited was granted an exemption by

In 1977 the Bank set up a wholly owned subsidiary called Bank of England Nominees Limited (BOEN), a now-defunct private limited company, with two of its hundred £1 shares issued. According to its memorandum of association, its objectives were: "To act as Nominee or agent or attorney either solely or jointly with others, for any person or persons, partnership, company, corporation, government, state, organisation, sovereign, province, authority, or public body, or any group or association of them". Bank of England Nominees Limited was granted an exemption by  In 1993, the bank produced its first ''Inflation Report'' for the government, detailing inflationary trends and pressures. This annually produced report remains one of the bank's major publications. The success of

In 1993, the bank produced its first ''Inflation Report'' for the government, detailing inflationary trends and pressures. This annually produced report remains one of the bank's major publications. The success of

A

A

Mervyn King became the

Mervyn King became the

excerpt and text search

* * Fforde, John. ''The Role of the Bank of England, 1941–1958'' (1992

excerpt and text search

* Francis, John. ''History of the Bank of England: Its Times and Traditions'

excerpt and text search

* Hennessy, Elizabeth. ''A Domestic History of the Bank of England, 1930–1960'' (2008

excerpt and text search

* Kynaston, David. 2017. Till Time's Last Sand: A History of the Bank of England, 1694–2013. Bloomsbury. * Lane, Nicholas. "The Bank of England in the Nineteenth Century." ''History Today'' (Aug 1960) 19#8 pp 535–541. * O'Brien, Patrick K.; Palma, Nuno (2022).

Not an ordinary bank but a great engine of state: The Bank of England and the British economy, 1694–1844

. ''The Economic History Review.'' * Roberts, Richard, and

excerpt and text search

* Schuster, F. '' The Bank of England and the State'' * Wood, John H. ''A History of Central Banking in Great Britain and the United States'' (Cambridge University Press, 2005)

central bank

A central bank, reserve bank, or monetary authority is an institution that manages the currency and monetary policy of a country or monetary union,

and oversees their commercial banking system. In contrast to a commercial bank, a central ba ...

of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the English Government

There has not been a government of England since 1707 when the Kingdom of England ceased to exist as a sovereign state, as it merged with the Kingdom of Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.Government of the United Kingdom

ga, Rialtas a Shoilse gd, Riaghaltas a Mhòrachd

, image = HM Government logo.svg

, image_size = 220px

, image2 = Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (HM Government).svg

, image_size2 = 180px

, caption = Royal coat of arms of t ...

, it is the world's eighth-oldest bank. It was privately owned by stockholders from its foundation in 1694 until it was nationalised in 1946 by the Attlee ministry

Clement Attlee was invited by King George VI to form the Attlee ministry in the United Kingdom in July 1945, succeeding Winston Churchill as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. The Labour Party had won a landslide victory at the 1945 gene ...

.

The bank became an independent public organisation in 1998, wholly owned by the Treasury Solicitor

The Government Legal Department (previously called the Treasury Solicitor's Department) is the largest in-house legal organisation in the United Kingdom's Government Legal Service.

The department is headed by the Treasury Solicitor. This office go ...

on behalf of the government, with a mandate to support the economic policies of the government of the day, but independence in maintaining price stability.

The bank is one of eight banks authorised to issue banknotes in the United Kingdom, has a monopoly on the issue of banknotes in England and Wales

England and Wales () is one of the three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It covers the constituent countries England and Wales and was formed by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542. The substantive law of the jurisdiction is Eng ...

, and regulates the issue of banknotes by commercial banks in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

and Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

.

The bank's Monetary Policy Committee Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) may refer to:

* Monetary Policy Committee (India)

The Monetary Policy Committee is responsible for fixing the benchmark interest rate in India. The meetings of the Monetary Policy Committee are held at least fo ...

has devolved responsibility for managing monetary policy

Monetary policy is the policy adopted by the monetary authority of a nation to control either the interest rate payable for very short-term borrowing (borrowing by banks from each other to meet their short-term needs) or the money supply, often a ...

. The Treasury has reserve powers to give orders to the committee "if they are required in the public interest and by extreme economic circumstances", but Parliament must endorse such orders within 28 days. In addition, the bank's Financial Policy Committee The Financial Policy Committee (FPC) is an official committee of the Bank of England, modelled on the already well established Monetary Policy Committee. It was announced in 2010 as a new body responsible for monitoring the economy of the United Kin ...

was set up in 2011 as a macroprudential regulator to oversee the UK's financial sector.

The bank's headquarters have been in London's main financial district, the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London fr ...

, on Threadneedle Street

Threadneedle Street is a street in the City of London, England, between Bishopsgate at its northeast end and Bank junction in the southwest. It is one of nine streets that converge at Bank. It lies in the ward of Cornhill.

History

The stree ...

, since 1734. It is sometimes known as ''The Old Lady of Threadneedle Street'' a name taken from a satirical cartoon by James Gillray

James Gillray (13 August 1756Gillray, James and Draper Hill (1966). ''Fashionable contrasts''. Phaidon. p. 8.Baptism register for Fetter Lane (Moravian) confirms birth as 13 August 1756, baptism 17 August 1756 1June 1815) was a British caricatur ...

in 1797. The road junction outside is known as Bank Junction.

As a regulator and central bank, the Bank of England has not offered consumer banking services for many years, but it still does manage some public-facing services, such as exchanging superseded bank notes. Until 2016, the bank provided personal banking services as a privilege for employees.

History

Founding

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

's crushing defeat by France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, the dominant naval power, in naval engagements culminating in the 1690 Battle of Beachy Head, became the catalyst for England to rebuild itself as a global power. William III William III or William the Third may refer to:

Kings

* William III of Sicily (c. 1186–c. 1198)

* William III of England and Ireland or William III of Orange or William II of Scotland (1650–1702)

* William III of the Netherlands and Luxembourg ...

's government wanted to build a naval fleet that would rival that of France; however, the ability to construct this fleet was hampered both by a lack of available public funds and the low credit of the English government in London. This lack of credit made it impossible for the English government to borrow the £1,200,000 (at 8% per annum) that it wanted to construct the fleet.

To induce subscription to the loan, the subscribers were to be incorporated by the name of the Governor and Company of the Bank of England. The bank was given exclusive possession of the government's balances and was the only limited-liability corporation allowed to issue bank notes. The lenders would give the government cash (bullion) and issue notes against the government bonds, which could be lent again. The £1.2 million was raised in 12 days; half of this was used to rebuild the navy.

As a side effect, the huge industrial effort needed, including establishing ironworks

An ironworks or iron works is an industrial plant where iron is smelted and where heavy iron and steel products are made. The term is both singular and plural, i.e. the singular of ''ironworks'' is ''ironworks''.

Ironworks succeeded bloomeri ...

to make more nails and advances in agriculture feeding the quadrupled strength of the navy, started to transform the economy. This helped the new Kingdom of Great Britain

The Kingdom of Great Britain (officially Great Britain) was a Sovereign state, sovereign country in Western Europe from 1 May 1707 to the end of 31 December 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of ...

– England and Scotland were formally united in 1707 – to become powerful. The power of the navy made Britain the dominant world power in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

The establishment of the bank was devised by Charles Montagu, 1st Earl of Halifax

Charles Montagu, 1st Earl of Halifax, (16 April 1661 – 19 May 1715), was an English statesman and poet. He was the grandson of the 1st Earl of Manchester and was eventually ennobled himself, first as Baron Halifax in 1700 and later as Earl ...

, in 1694. The plan of 1691, which had been proposed by William Paterson three years before, had not then been acted upon. Fifty-eight years earlier, in 1636, Financier to the king, Philip Burlamachi

Philip Burlamachi (1575 – 1644) was a major financial intermediary of King Charles I of England, and is remembered as the inventor of the concept of a central bank.

Burlamachi was born Sedan, France. His family was of Italian origin, exile ...

, had proposed exactly the same idea in a letter addressed to Francis Windebank

Sir Francis Windebank (1582 – 1 September 1646) was an English politician who was Secretary of State under Charles I.

Biography

Francis was the only son of Sir Thomas Windebank of Hougham, Lincolnshire, who owed his advancement to the Cecil ...

. He proposed a loan of £1.2 million to the government; in return the subscribers would be incorporated as The Governor and Company of the Bank of England with long-term banking privileges including the issue of notes.

The royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, bu ...

was granted on 27 July through the passage of the Tonnage Act 1694

The Bank of England Act 1694 (5 & 6 Will & Mar c 20), sometimes referred to as the Tonnage Act 1694, is an Act of the Parliament of England. It is one of the Bank of England Acts 1694 to 1892.The Short Titles Act 1896, section 2(1) and Schedule ...

. Public finances were in such dire condition at the time that the terms of the loan were that it was to be serviced at a rate of 8% per annum, and there was also a service charge of £4,000 per annum for the management of the loan. The first governor was John Houblon

Sir John Houblon (13 March 1632 – 10 January 1712) was the first Governor of the Bank of England from 1694 to 1697.

Early life

John Houblon was the third son of James Houblon, a London merchant, and his wife, Mary Du Quesne, daughter of Jean ...

(who was later depicted on a £50 note).

The bank initially did not have its own building, first opening on 1 August 1694 in Mercers' Hall

The Worshipful Company of Mercers is the premier Livery Company of the City of London and ranks first in the order of precedence of the Companies. It is the first of the Great Twelve City Livery Companies. Although of even older origin, the c ...

on Cheapside

Cheapside is a street in the City of London, the historic and modern financial centre of London, which forms part of the A40 London to Fishguard road. It links St. Martin's Le Grand with Poultry. Near its eastern end at Bank junction, where ...

. This however was found to be too small and from 31 December 1694 the bank operated from Grocers' Hall

The Worshipful Company of Grocers is one of the 110 Livery Company, Livery Companies of the City of London and ranks second in order of precedence. The Grocers' Company was established in 1345 for merchants occupied in the trade of grocer and is ...

, located then on Poultry

Poultry () are domesticated birds kept by humans for their eggs, their meat or their feathers. These birds are most typically members of the superorder Galloanserae (fowl), especially the order Galliformes (which includes chickens, quails, a ...

, where it would remain for almost 40 years.

18th century

In 1700, the

In 1700, the Hollow Sword Blade Company The Hollow Sword Blades Company was a British joint-stock company founded in 1691 by a goldsmith, Sir Stephen Evance, for the manufacture of hollow-ground rapiers.

In 1700 the company was purchased by a syndicate of businessmen who used the corp ...

was purchased by a group of businessmen who wished to establish a competing English bank (in an action that would today be considered a "back door listing"). The Bank of England's initial monopoly on English banking was due to expire in 1710. However, it was instead renewed, and the Sword Blade company failed to achieve its goal.

The South Sea Company

The South Sea Company (officially The Governor and Company of the merchants of Great Britain, trading to the South Seas and other parts of America, and for the encouragement of the Fishery) was a British joint-stock company founded in Ja ...

was established in 1711. In 1720 it became responsible for part of the UK's national debt, becoming a major competitor to the Bank of England. While the "South Sea Bubble" disaster soon ensued, the company continued managing part of the UK national debt until 1853.

The Bank of England moved to its current location in Threadneedle Street in 1734 and thereafter slowly acquired neighbouring land to create the site necessary for erecting the bank's original home at this location, under the direction of its chief architect John Soane

Sir John Soane (; né Soan; 10 September 1753 – 20 January 1837) was an English architect who specialised in the Neoclassical architecture, Neo-Classical style. The son of a bricklayer, he rose to the top of his profession, becoming professo ...

, between 1790 and 1827. (Herbert Baker

Sir Herbert Baker (9 June 1862 – 4 February 1946) was an English architect remembered as the dominant force in South African architecture for two decades, and a major designer of some of New Delhi's most notable government structures. He wa ...

's rebuilding of the bank in the first half of the 20th century, demolishing most of Soane's masterpiece, was described by architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner

Sir Nikolaus Bernhard Leon Pevsner (30 January 1902 – 18 August 1983) was a German-British art historian and architectural historian best known for his monumental 46-volume series of county-by-county guides, ''The Buildings of England'' (1 ...

as "the greatest architectural crime, in the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London fr ...

, of the twentieth century".)

The bank's charter was again renewed in 1742 and 1764.

The credit crisis of 1772

The British credit crisis of 1772-1773 also known as the crisis of 1772, or the panic of 1772, was a peacetime financial crisis which originated in London and then spread to Scotland and the Dutch Republic.

has been described as the first modern banking crisis faced by the Bank of England. The whole City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London fr ...

was in uproar when Alexander Fordyce

Alexander Fordyce (7 August 1729-8 September 1789) was an eminent Scottish banker, centrally involved in the bank run on Neale, James, Fordyce and Downe which led to the credit crisis of 1772. He used the profits from other investments to cov ...

was declared bankrupt

Bankruptcy is a legal process through which people or other entities who cannot repay debts to creditors may seek relief from some or all of their debts. In most jurisdictions, bankruptcy is imposed by a court order, often initiated by the debt ...

. In August 1773, the Bank of England assisted the EIC with a loan. The strain upon the reserves of the Bank of England was not eased until towards the end of the year.

When the idea and reality of the national debt

A country's gross government debt (also called public debt, or sovereign debt) is the financial liabilities of the government sector. Changes in government debt over time reflect primarily borrowing due to past government deficits. A deficit oc ...

came about during the 18th century, this was also largely managed by the bank.

During the American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, business for the bank was so good that George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

remained a shareholder throughout the period.

By the bank's charter renewal in 1781, it was also the bankers' bank – keeping enough gold to pay its notes on demand until 26 February 1797 when war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

had so diminished gold reserves

A gold reserve is the gold held by a national central bank, intended mainly as a guarantee to redeem promises to pay depositors, note holders (e.g. paper money), or trading peers, during the eras of the gold standard, and also as a store of v ...

that – following an invasion scare caused by the Battle of Fishguard

The Battle of Fishguard was a military invasion of Great Britain by Revolutionary France during the War of the First Coalition. The brief campaign, on 22–24 February 1797, is the most recent landing on British soil by a hostile foreign force ...

days earlier – the government prohibited the bank from paying out in gold by the passing of the bank Restriction Act 1797. This prohibition lasted until 1821.

19th century

Nathan Mayer Rothschild

Nathan Mayer Rothschild (16 September 1777 – 28 July 1836) was an English-German banker, businessman and financier. Born in Frankfurt am Main in Germany, he was the third of the five sons of Gutle (Schnapper) and Mayer Amschel Rothschild, an ...

succeeded in supplying it with gold.

The Bank Charter Act 1844

The Bank Charter Act 1844 (7 & 8 Vict. c. 32), sometimes referred to as the Peel Banking Act of 1844, was an Act of Parliament, Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, passed under the government of Robert Peel, which restricted the powers ...

tied the issue of notes to the gold reserves and gave the bank sole rights with regard to the issue of banknotes in England. Private banks that had previously had that right retained it, provided that their headquarters were outside London and that they deposited security against the notes that they issued.

The bank acted as lender of last resort

A lender of last resort (LOLR) is the institution in a financial system that acts as the provider of liquidity to a financial institution which finds itself unable to obtain sufficient liquidity in the interbank lending market when other facil ...

for the first time in the panic of 1866

The Panic of 1866 was an international financial downturn that accompanied the failure of Overend, Gurney and Company in London, and the ''corso forzoso'' abandonment of the silver standard in Italy.

In Britain, the economic impacts are held pa ...

.

20th century

The last private bank in England to issue its own notes was Thomas Fox'sFox, Fowler and Company

Fox, Fowler, and Company was a British private bank, based in Wellington, Somerset. The company was founded in 1787 as a supplementary business to the main activities of the Fox family, sheep-herding and wool-making.

Banknote issue

Like many ot ...

bank in Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by me ...

, which rapidly expanded until it merged with Lloyds Bank in 1927. They were legal tender until 1964. There are nine notes left in circulation; one is housed at Tone Dale House

Tone Dale House (or Tonedale House) is a Grade II listed country house built in 1801 or 1807 by Thomas Fox in Wellington, Somerset, England. Wellington lies west of Taunton in the vale of Taunton Deane, from the Devon border. Tone Dale House, ...

, Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by me ...

. (Scottish and Northern Irish private banks continue to issue notes regulated by the bank.)

Britain was on the gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from the la ...

, meaning the value of sterling was fixed by the price of gold, until 1931 when the Bank of England had to take Britain off the gold standard due to the effects of Great Depression spreading to Europe.

During the governorship of Montagu Norman

Montagu Collet Norman, 1st Baron Norman DSO PC (6 September 1871 – 4 February 1950) was an English banker, best known for his role as the Governor of the Bank of England from 1920 to 1944.

Norman led the bank during the toughest period in m ...

, from 1920 to 1944, the bank made deliberate efforts to move away from commercial bank

A commercial bank is a financial institution which accepts deposits from the public and gives loans for the purposes of consumption and investment to make profit.

It can also refer to a bank, or a division of a large bank, which deals with cor ...

ing and become a central bank.

During WWII, over 10% of the face value of circulating Pound Sterling banknotes were forgeries produced by Germany.

In 1946, shortly after the end of Montagu Norman's tenure, the bank was nationalised by the Labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

government.

The bank pursued the multiple goals of Keynesian economics after 1945, especially "easy money" and low-interest rates to support aggregate demand. It tried to keep a fixed exchange rate and attempted to deal with inflation and sterling weakness by credit and exchange controls.

The bank's " 10 bob note" was withdrawn from circulation in 1970 in preparation for Decimal Day

Decimal Day in the United Kingdom and in Ireland was Monday 15 February 1971, the day on which each country decimalised its respective £sd currency of pounds, shillings, and pence.

Before this date, the British pound sterling (symbol "£" ...

in 1971.

In 1977 the Bank set up a wholly owned subsidiary called Bank of England Nominees Limited (BOEN), a now-defunct private limited company, with two of its hundred £1 shares issued. According to its memorandum of association, its objectives were: "To act as Nominee or agent or attorney either solely or jointly with others, for any person or persons, partnership, company, corporation, government, state, organisation, sovereign, province, authority, or public body, or any group or association of them". Bank of England Nominees Limited was granted an exemption by

In 1977 the Bank set up a wholly owned subsidiary called Bank of England Nominees Limited (BOEN), a now-defunct private limited company, with two of its hundred £1 shares issued. According to its memorandum of association, its objectives were: "To act as Nominee or agent or attorney either solely or jointly with others, for any person or persons, partnership, company, corporation, government, state, organisation, sovereign, province, authority, or public body, or any group or association of them". Bank of England Nominees Limited was granted an exemption by Edmund Dell

Edmund Emanuel Dell (15 August 1921 – 1 November 1999) was a British politician and businessman.

Early life

Dell was born in London, the son of a Jewish manufacturer. In the Second World War he served in the Royal Artillery, reaching the r ...

, Secretary of State for Trade, from the disclosure requirements under Section 27(9) of the Companies Act 1976, because "it was considered undesirable that the disclosure requirements should apply to certain categories of shareholders". The Bank of England is also protected by its royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, bu ...

status and the Official Secrets Act

An Official Secrets Act (OSA) is legislation that provides for the protection of state secrets and official information, mainly related to national security but in unrevised form (based on the UK Official Secrets Act 1911) can include all infor ...

. BOEN was a vehicle for governments and heads of state to invest in UK companies (subject to approval from the Secretary of State), providing they undertake "not to influence the affairs of the company". In its later years, BOEN was no longer exempt from company law disclosure requirements. Although a dormant company

A dormant company is a company that carries out no business activities in the given period of time. Dormant companies do not engage in buying/selling for profit, not carrying on business or profession, providing services, earning interest, mana ...

, dormancy does not preclude a company actively operating as a nominee shareholder. BOEN had two shareholders: the Bank of England, and the Secretary of the Bank of England.

The reserve requirement

Reserve requirements are central bank regulations that set the minimum amount that a commercial bank must hold in liquid assets. This minimum amount, commonly referred to as the commercial bank's reserve, is generally determined by the centra ...

for banks to hold a minimum fixed proportion of their deposits as reserves at the Bank of England was abolished in 1981: see for more details. The contemporary transition from Keynesian economics to Chicago economics was analysed by Nicholas Kaldor

Nicholas Kaldor, Baron Kaldor (12 May 1908 – 30 September 1986), born Káldor Miklós, was a Cambridge economist in the post-war period. He developed the "compensation" criteria called Kaldor–Hicks efficiency for welfare comparisons (1939), d ...

in ''The Scourge of Monetarism''.

The handing over of monetary policy to the bank became a key plank of the Liberal Democrats' economic policy for the 1992 general election. Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

MP Nicholas Budgen

Nicholas William Budgen (3 November 1937 – 26 October 1998), often called Nick Budgen, was a British Conservative Party politician.

Early life and career

Named after St Nicholas Church in Newport, Shropshire of which his grandfather was a pr ...

had also proposed this as a private member's bill

A private member's bill is a bill (proposed law) introduced into a legislature by a legislator who is not acting on behalf of the executive branch. The designation "private member's bill" is used in most Westminster system jurisdictions, in whi ...

in 1996, but the bill failed as it had the support of neither the government nor the opposition.

The UK government left the expensive-to-maintain European Exchange Rate Mechanism

The European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II) is a system introduced by the European Economic Community on 1 January 1999 alongside the introduction of a single currency, the euro (replacing ERM 1 and the euro's predecessor, the ECU) as p ...

in September 1992, in an action that cost HM Treasury over £3 billion. This led to closer communication between the government and the bank.

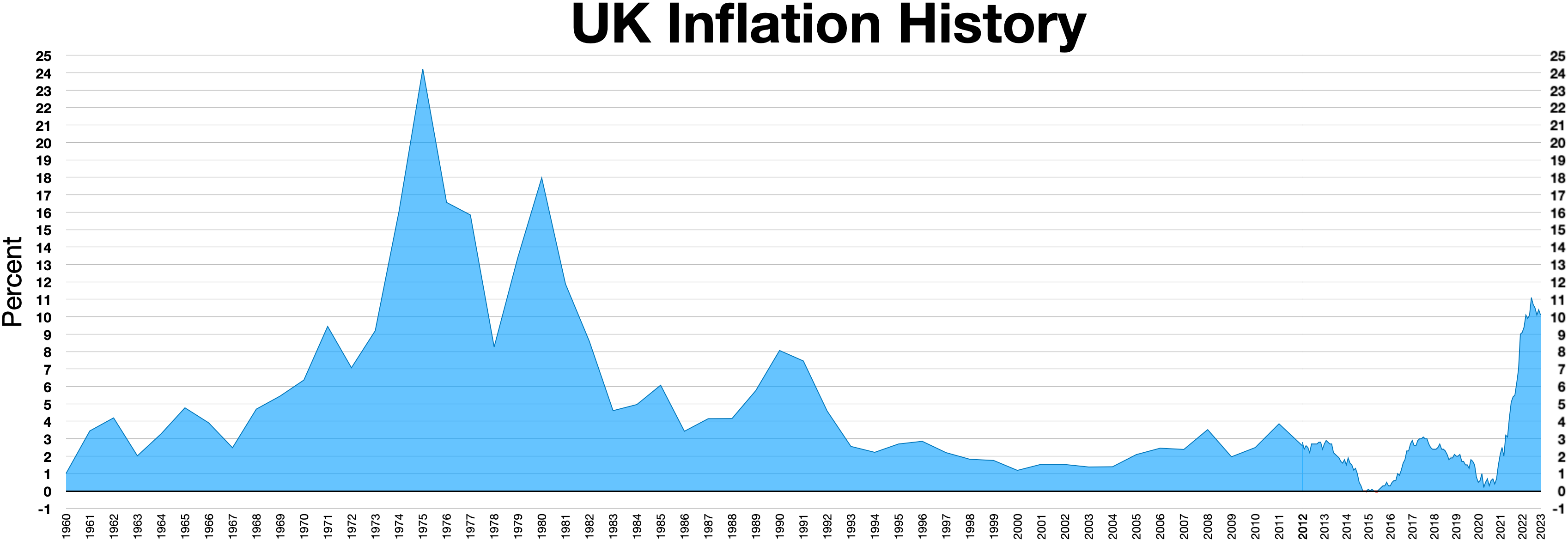

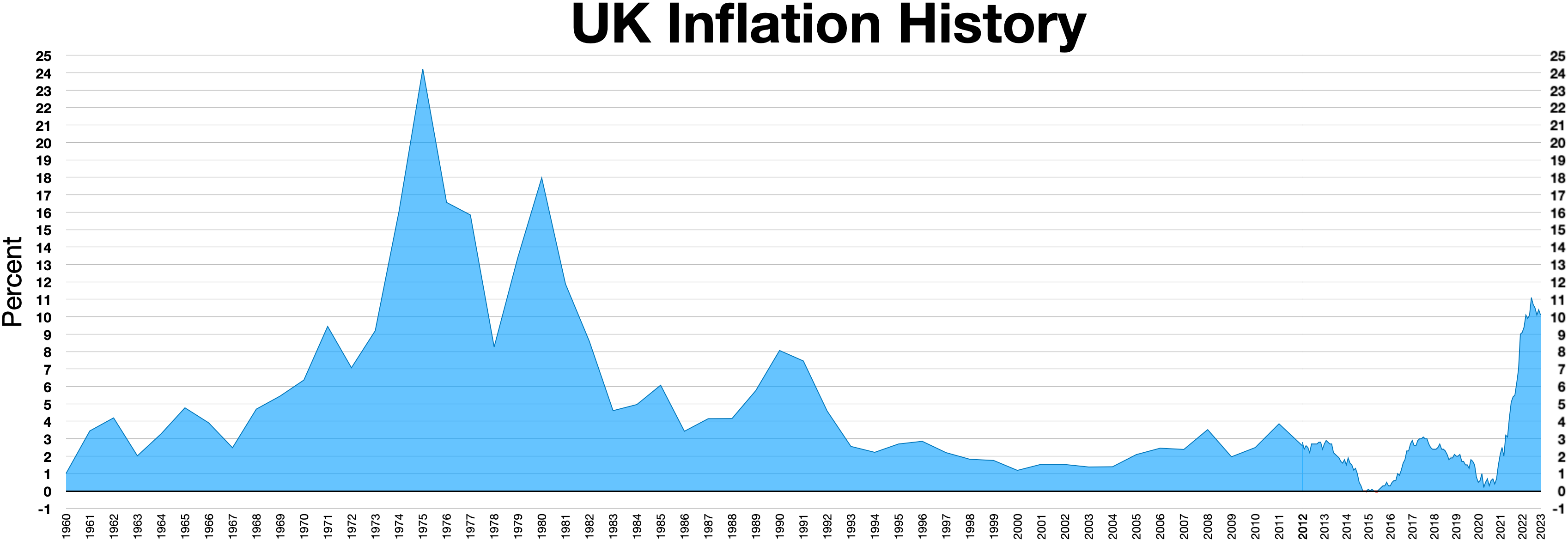

In 1993, the bank produced its first ''Inflation Report'' for the government, detailing inflationary trends and pressures. This annually produced report remains one of the bank's major publications. The success of

In 1993, the bank produced its first ''Inflation Report'' for the government, detailing inflationary trends and pressures. This annually produced report remains one of the bank's major publications. The success of inflation target

In macroeconomics, inflation targeting is a monetary policy where a central bank follows an Forward guidance, explicit target for the inflation rate for the medium-term and announces this inflation target to the public. The assumption is that the ...

ing in the United Kingdom has been attributed to the bank's focus on transparency. The Bank of England has been a leader in producing innovative ways of communicating information to the public, especially through its Inflation Report, which many other central banks have emulated.

The bank celebrated its three-hundredth birthday in 1994.

In 1996, the bank produced its first ''Financial Stability Review''. This annual publication became known as the ''Financial Stability Report'' in 2006. Also that year, the bank set up its real-time gross settlement (RTGS) system to improve risk-free settlement between UK banks.

On 6 May 1997, following the 1997 general election that brought a Labour government to power for the first time since 1979, it was announced by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown

James Gordon Brown (born 20 February 1951) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 2007 to 2010. He previously served as Chance ...

, that the bank would be granted operational independence over monetary policy. Under the terms of the Bank of England Act 1998 (which came into force on 1 June 1998) the bank's Monetary Policy Committee Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) may refer to:

* Monetary Policy Committee (India)

The Monetary Policy Committee is responsible for fixing the benchmark interest rate in India. The meetings of the Monetary Policy Committee are held at least fo ...

(MPC) was given sole responsibility for setting interest rates to meet the Government's Retail Prices Index

In the United Kingdom, the Retail Prices Index or Retail Price Index (RPI) is a measure of inflation published monthly by the Office for National Statistics. It measures the change in the cost of a representative sample of retail final good, goods ...

(RPI) inflation target of 2.5%. The target has changed to 2% since the Consumer Price Index

A consumer price index (CPI) is a price index, the price of a weighted average market basket of consumer goods and services purchased by households. Changes in measured CPI track changes in prices over time.

Overview

A CPI is a statistica ...

(CPI) replaced the Retail Prices Index as the Treasury's inflation index. If inflation overshoots or undershoots the target by more than 1% the Governor has to write a letter to the Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

explaining why, and how he will remedy the situation.

Independent central banks that adopt an inflation target are known as Friedmanite central banks. This change in Labour's politics was described by Skidelsky in ''The Return of the Master'' as a mistake and as an adoption of the rational expectations hypothesis as promulgated by Alan Walters

Sir Alan Arthur Walters (17 June 1926 – 3 January 2009) was a British economist who was best known as the Chief Economic Adviser to Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher from 1981 to 1983 and (after his return from the United States) again for fi ...

. Inflation targets combined with central bank independence have been characterised as a "starve the beast" strategy creating a lack of money in the public sector.

1913 attempted bombing

A

A terrorist

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

bombing was attempted outside the Bank of England building on 4 April 1913. A bomb was discovered smoking and ready to explode next to railings outside the building. The bomb had been planted as part of the suffragette bombing and arson campaign

Suffragettes in Great Britain and Ireland orchestrated a bombing and arson campaign between the years 1912 and 1914. The campaign was instigated by the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), and was a part of their wider campaign for women's ...

, in which the Women's Social and Political Union

The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) was a women-only political movement and leading militant organisation campaigning for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom from 1903 to 1918. Known from 1906 as the suffragettes, its membership and ...

(WSPU) launched a series of politically motivated bombing and arson attacks nationwide as part of their campaign for women's suffrage. The bomb was defused before it could detonate, in what was then one of the busiest public streets in the capital, which likely prevented many civilian casualties. The bomb had been planted the day after WSPU leader Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst ('' née'' Goulden; 15 July 1858 – 14 June 1928) was an English political activist who organised the UK suffragette movement and helped women win the right to vote. In 1999, ''Time'' named her as one of the 100 Most Impo ...

was sentenced to three years' imprisonment for carrying out a bombing on the home of politician David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

.

The remains of the bomb, which was built into a milk churn

A milk churn is a tall, conical or cylindrical container for the transportation of milk. It is sometimes referred to as a milk can.

History

The usage of the word 'churn' was retained for describing these containers, although they were not thems ...

, are now on display at the City of London Police Museum

The City of London Police is the territorial police force responsible for law enforcement within the City of London, including the Middle and Inner Temples. The force responsible for law enforcement within the remainder of the London region, ou ...

.

21st century

Mervyn King became the

Mervyn King became the Governor of the Bank of England

The governor of the Bank of England is the most senior position in the Bank of England. It is nominally a civil service post, but the appointment tends to be from within the bank, with the incumbent grooming their successor. The governor of the Ba ...

on 30 June 2003.

In 2009, a request made to HM Treasury

His Majesty's Treasury (HM Treasury), occasionally referred to as the Exchequer, or more informally the Treasury, is a department of His Majesty's Government responsible for developing and executing the government's public finance policy and ec ...

under the Freedom of Information Act Freedom of Information Act may refer to the following legislations in different jurisdictions which mandate the national government to disclose certain data to the general public upon request:

* Freedom of Information Act 1982, the Australian act

* ...

sought details about the 3% Bank of England stock owned by unnamed shareholders whose identity the bank is not at liberty to disclose. In a letter of reply dated 15 October 2009, HM Treasury explained that "Some of the 3% Treasury stock which was used to compensate former owners of Bank stock has not been redeemed. However, interest is paid out twice a year and it is not the case that this has been accumulating and compounding."

The Financial Services Act 2012

The Financial Services Act 2012 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which implements a new regulatory framework for the financial system and financial services in the UK. It replaces the Financial Services Authority with two new ...

gave the bank additional functions and bodies, including an independent Financial Policy Committee The Financial Policy Committee (FPC) is an official committee of the Bank of England, modelled on the already well established Monetary Policy Committee. It was announced in 2010 as a new body responsible for monitoring the economy of the United Kin ...

(FPC), the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA), and more powers to supervise financial market infrastructure providers.

Canadian Mark Carney

Mark Joseph Carney (born March 16, 1965) is a Canadian economist and banker who served as the governor of the Bank of Canada from 2008 to 2013 and the governor of the Bank of England from 2013 to 2020. Since October 2020, he is vice chairman and ...

assumed the post of Governor of the Bank of England

The governor of the Bank of England is the most senior position in the Bank of England. It is nominally a civil service post, but the appointment tends to be from within the bank, with the incumbent grooming their successor. The governor of the Ba ...

on 1 July 2013. He served an initial five-year term rather than the typical eight. He became the first Governor not to be a United Kingdom citizen but has since been granted citizenship. At Government request, his term was extended to 2019, then again to 2020. , the bank also had four Deputy Governors

Deputy or depute may refer to:

* Steward (office)

* Khalifa, an Arabic title that can signify "deputy"

* Deputy (legislator), a legislator in many countries and regions, including:

** A member of a Chamber of Deputies, for example in Italy, Spai ...

.

BOEN was dissolved, following liquidation, in July 2017.

Andrew Bailey succeeded Carney as the Governor of the Bank of England on 16 March 2020.

Functions

Two main areas are tackled by the bank to ensure it carries out these functions efficiently:Monetary stability

Stable prices and confidence in the currency are the two main criteria for monetary stability. Stable prices are maintained by seeking to ensure that price increases meet the Government's inflation target. The bank aims to meet this target by adjusting the baseinterest rate

An interest rate is the amount of interest due per period, as a proportion of the amount lent, deposited, or borrowed (called the principal sum). The total interest on an amount lent or borrowed depends on the principal sum, the interest rate, th ...

, which is decided by the Monetary Policy Committee Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) may refer to:

* Monetary Policy Committee (India)

The Monetary Policy Committee is responsible for fixing the benchmark interest rate in India. The meetings of the Monetary Policy Committee are held at least fo ...

, and through its communications strategy, such as publishing yield curve

In finance, the yield curve is a graph which depicts how the yields on debt instruments - such as bonds - vary as a function of their years remaining to maturity. Typically, the graph's horizontal or x-axis is a time line of months or ye ...

s.

Maintaining financial stability involves protecting against threats to the whole financial system. Threats are detected by the bank's surveillance and market intelligence

Market intelligence (MI) is gathering and analyzing information relevant to a company's market - trends, competitor and customer (existing, lost and targeted) monitoring. It is a subtype of competitive intelligence (CI), which is data and infor ...

functions. The threats are then dealt with through financial and other operations, both at home and abroad. In exceptional circumstances, the bank may act as the lender of last resort

A lender of last resort (LOLR) is the institution in a financial system that acts as the provider of liquidity to a financial institution which finds itself unable to obtain sufficient liquidity in the interbank lending market when other facil ...

by extending credit when no other institution will.

The bank works together with other institutions to secure both monetary and financial stability, including:

* HM Treasury

His Majesty's Treasury (HM Treasury), occasionally referred to as the Exchequer, or more informally the Treasury, is a department of His Majesty's Government responsible for developing and executing the government's public finance policy and ec ...

, the Government department responsible for financial and economic policy; and

* Other central banks and international organisations, with the aim of improving the international financial system.

The 1997 memorandum of understanding describes the terms under which the bank, the Treasury, and the FSA work toward the common aim of increased financial stability. In 2010, the incoming Chancellor announced his intention to merge the FSA back into the bank. As of 2012, the current director for financial stability is Andy Haldane

Andrew G. Haldane, (; born 18 August 1967) is a British economist who worked at the Bank of England between 1989 and 2021 as the chief economist and executive director of monetary analysis and statistics. He resigned from the Bank of England i ...

.

The bank acts as the government's banker, and it maintains the government's Consolidated Fund

In many states with political systems derived from the Westminster system, a consolidated fund or consolidated revenue fund is the main bank account of the government. General taxation is taxation paid into the consolidated fund (as opposed ...

account. It also manages the country's foreign exchange

The foreign exchange market (Forex, FX, or currency market) is a global decentralized or over-the-counter (OTC) market for the trading of currencies. This market determines foreign exchange rates for every currency. It includes all as ...

and gold reserves

A gold reserve is the gold held by a national central bank, intended mainly as a guarantee to redeem promises to pay depositors, note holders (e.g. paper money), or trading peers, during the eras of the gold standard, and also as a store of v ...

. The bank also acts as the bankers' bank, especially in its capacity as a lender of last resort.

The bank has a monopoly on the issue of banknote

A banknote—also called a bill (North American English), paper money, or simply a note—is a type of negotiable instrument, negotiable promissory note, made by a bank or other licensed authority, payable to the bearer on demand.

Banknotes w ...

s in England and Wales. Scottish and Northern Irish banks retain the right to issue their own banknotes, but they must be backed one-for-one with deposits at the bank, excepting a few million pounds representing the value of notes they had in circulation in 1845. The bank decided to sell its banknote-printing operations to De La Rue

De La Rue plc (, ) is a British company headquartered in Basingstoke, England, that designs and produces banknotes, secure polymer substrate and banknote security features (including security holograms, security threads and security printe ...

in December 2002, under the advice of Close Brothers Corporate Finance Ltd.

Since 1998 the Monetary Policy Committee Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) may refer to:

* Monetary Policy Committee (India)

The Monetary Policy Committee is responsible for fixing the benchmark interest rate in India. The meetings of the Monetary Policy Committee are held at least fo ...

(MPC) has had the responsibility for setting the official interest rate. However, with the decision to grant the bank operational independence, responsibility for government debt management was transferred in 1998 to the new Debt Management Office

The UK Debt Management Office (DMO) is the executive agency responsible for debt and cash management for the UK Government, lending to local authorities and managing certain public sector funds.

Purpose

The DMO is responsible for day-to-day man ...

, which also took over government cash management in 2000. Computershare

Computershare Limited is an Australian stock transfer company that provides corporate trust, stock transfer and employee share plan services in a number of different countries.

The company currently has offices in 20 countries, including A ...

took over as the registrar for UK Government bonds (gilt-edged securities

Gilt-edged securities are bonds issued by the UK Government. The term is of British origin, and then referred to the debt securities issued by the Bank of England on behalf of His Majesty's Treasury, whose paper certificates had a gilt (or gilde ...

or 'gilts') from the bank at the end of 2004.

The bank used to be responsible for the regulation and supervision of the banking and insurance industries. This responsibility was transferred to the Financial Services Authority

The Financial Services Authority (FSA) was a quasi-judicial body accountable for the financial regulation, regulation of the financial services industry in the United Kingdom between 2001 and 2013. It was founded as the Securities and Investmen ...

in June 1998, but after the financial crises in 2008, new banking legislation transferred the responsibility for regulation and supervision of the banking and insurance industries back to the bank.

In 2011 the interim Financial Policy Committee The Financial Policy Committee (FPC) is an official committee of the Bank of England, modelled on the already well established Monetary Policy Committee. It was announced in 2010 as a new body responsible for monitoring the economy of the United Kin ...

(FPC) was created as a mirror committee to the MPC to spearhead the bank's new mandate on financial stability. The FPC is responsible for macro-prudential regulation of all UK banks and insurance companies.

To help maintain economic stability, the bank attempts to broaden understanding of its role, both through regular speeches and publications by senior Bank figures, a semiannual Financial Stability Report, and through a wider education strategy aimed at the general public. It currently maintains a free museum and ran the Target Two Point Zero competition for A-level students, closing in 2017.

Asset purchase facility

The bank has operated, since January 2009, an Asset Purchase Facility (APF) to buy "high-quality assets financed by the issue of Treasury bills and the DMO's cash management operations" and thereby improve liquidity in the credit markets. It has, since March 2009, also provided the mechanism by which the bank's policy ofquantitative easing

Quantitative easing (QE) is a monetary policy action whereby a central bank purchases predetermined amounts of government bonds or other financial assets in order to stimulate economic activity. Quantitative easing is a novel form of monetary pol ...

(QE) is achieved, under the auspices of the MPC. Along with managing the QE funds, which were £895 bn at peak, the APF continues to operate its corporate facilities. Both are undertaken by a subsidiary company of the Bank of England, the Bank of England Asset Purchase Facility Fund Limited (BEAPFF).

QE was primarily designed as an instrument of monetary policy. The mechanism required the Bank of England to purchase government bonds on the secondary market, financed by creating new central bank money

In economics, the monetary base (also base money, money base, high-powered money, reserve money, outside money, central bank money or, in the United Kingdom, UK, narrow money) in a country is the total amount of money created by the central ban ...

. This would have the effect of increasing the asset prices of the bonds purchased, thereby lowering yields and dampening longer-term interest rates. The policy's aim was initially to ease liquidity constraints in the sterling reserves system but evolved into a wider policy to provide economic stimulus.

QE was enacted in six tranches between 2009 and 2020. At its peak in 2020, the portfolio totalled £895 billion, comprising £875 billion of UK government bonds and £20 billion of high-grade commercial bonds.

In February 2022, the Bank of England announced its intention to commence winding down the QE portfolio. Initially this would be achieved by not replacing tranches of maturing bonds, and would later be accelerated through active bond sales.

In August 2022, the Bank of England reiterated its intention to accelerate the QE wind-down through active bond sales. This policy was affirmed in an exchange of letters between the Bank of England and the UK Chancellor of the Exchequer in September 2022. Between February 2022 and September 2022, a total of £37.1bn of government bonds matured, reducing the outstanding stock from £875.0bn at the end of 2021 to £837.9bn. In addition, a total of £1.1bn of corporate bonds matured, reducing the stock from £20.0bn to £18.9bn, with sales of the remaining stock planned to begin on 27 September.

Banknote issues

The bank has issued banknotes since 1694. Notes were originally hand-written; although they were partially printed from 1725 onwards, cashiers still had to sign each note and make them payable to someone. Notes were fully printed from 1855. Until 1928 all notes were "White Notes", printed in black and with a blank reverse. In the 18th and 19th centuries, White Notes were issued in £1 and £2 denominations. During the 20th century, White Notes were issued in denominations between £5 and £1000. Until the mid-19th century, commercial banks were allowed to issue their own banknotes, and notes issued by provincial banking companies were commonly in circulation. TheBank Charter Act 1844

The Bank Charter Act 1844 (7 & 8 Vict. c. 32), sometimes referred to as the Peel Banking Act of 1844, was an Act of Parliament, Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, passed under the government of Robert Peel, which restricted the powers ...

began the process of restricting note issue to the bank; new banks were prohibited from issuing their own banknotes, and existing note-issuing banks were not permitted to expand their issue. As provincial banking companies merged to form larger banks, they lost their right to issue notes, and the English private banknote eventually disappeared, leaving the bank with a monopoly of note issues in England and Wales. The last private bank to issue its own banknotes in England and Wales was Fox, Fowler and Company

Fox, Fowler, and Company was a British private bank, based in Wellington, Somerset. The company was founded in 1787 as a supplementary business to the main activities of the Fox family, sheep-herding and wool-making.

Banknote issue

Like many ot ...

in 1921.; However, the limitations of the 1844 Act only affected banks in England and Wales, and today three commercial banks in Scotland and four in Northern Ireland continue to issue their own banknotes

A banknote—also called a bill (North American English), paper money, or simply a note—is a type of negotiable instrument, negotiable promissory note, made by a bank or other licensed authority, payable to the bearer on demand.

Banknotes w ...

, regulated by the bank.

At the start of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, the Currency and Bank Notes Act 1914

A currency, "in circulation", from la, currens, -entis, literally meaning "running" or "traversing" is a standardization of money in any form, in use or circulation as a medium of exchange, for example banknotes and coins.

A more general def ...

was passed, which granted temporary powers to HM Treasury

His Majesty's Treasury (HM Treasury), occasionally referred to as the Exchequer, or more informally the Treasury, is a department of His Majesty's Government responsible for developing and executing the government's public finance policy and ec ...

for issuing banknotes to the values of £1 and 10/- (ten shillings). Treasury notes had full legal tender status and were not convertible into gold through the bank; they replaced the gold coin in circulation to prevent a run on sterling and to enable raw material purchases for armament production. These notes featured an image of King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Que ...

(Bank of England notes did not begin to display an image of the monarch until 1960). The wording on each note was:

Treasury notes were issued until 1928 when the Currency and Bank Notes Act 1928

The Currency and Bank Notes Act 1928 (18 & 19 Geo. V c.13) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom relating to banknotes. Among other things, it makes it a criminal offence

In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable ...

returned note-issuing powers to the banks. The Bank of England issued notes for ten shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence o ...

s and one pound for the first time on 22 November 1928.

During the Second World War, the German Operation Bernhard

Operation Bernhard was an exercise by Nazi Germany to forge British bank notes. The initial plan was to drop the notes over Britain to bring about a collapse of the British economy

The economy of the United Kingdom is a highly developed soci ...

attempted to counterfeit denominations between £5 and £50, producing 500,000 notes each month in 1943. The original plan was to parachute the money into the UK in an attempt to destabilise the British economy, but it was found more useful to use the notes to pay German agents operating throughout Europe. Although most fell into Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

hands at the end of the war, forgeries frequently appeared for years afterward, which led banknote denominations above £5 to be removed from circulation.

In 2006, over £53 million in banknotes belonging to the bank was stolen from a depot in Tonbridge, Kent

Tonbridge ( ) is a market town in Kent, England, on the River Medway, north of Royal Tunbridge Wells, south west of Maidstone and south east of London. In the administrative borough of Tonbridge and Malling, it had an estimated population ...

.

Modern banknotes are printed by contract with De La Rue

De La Rue plc (, ) is a British company headquartered in Basingstoke, England, that designs and produces banknotes, secure polymer substrate and banknote security features (including security holograms, security threads and security printe ...

Currency in Loughton, Essex

Loughton () is a town and civil parish in the Epping Forest District of Essex. Part of the metropolitan and urban area of London, the town borders Chingford, Waltham Abbey, Theydon Bois, Chigwell and Buckhurst Hill, and is northeast of Chari ...

.

Gold vault

The bank is custodian to the official gold reserves of the United Kingdom and around 30 other countries. , the bank holds around of gold, worth £141 billion. These estimates suggest that the vault could hold as much as 3% of the 171,300 tonnes of gold mined throughout human history.Governance of the Bank of England

Governors

Following is a list of the governors of the Bank of England since the beginning of the 20th century:Court of Directors

The Court of Directors is a unitary board that is responsible for setting the organisation's strategy and budget and making key decisions on resourcing and appointments. It consists of five executive members from the bank plus up to 9 non-executive members, all of whom are appointed by the Crown. The Chancellor selects the Chairman of the Court from among the non-executive members. The Court is required to meet at least seven times a year. The Governor serves for a period of eight years, the Deputy Governors for five years, and the non-executive members for up to four years.Other staff

Since 2013, the bank has had achief operating officer

A chief operating officer or chief operations officer, also called a COO, is one of the highest-ranking executive positions in an organization, composing part of the "C-suite". The COO is usually the second-in-command at the firm, especially if t ...

(COO). , the bank's COO has been Joanna Place

Joanna Ruth "Jo" Place (born 21 June 1962) is a British executive who has served as the chief operating officer of the Bank of England since July 2017.

Early life and education

Place was born on 21 June 1962 in Derby, England. She attended a ...

.

, the bank's chief economist Chief economist is a single-position job class having primary responsibility for the development, coordination, and production of economic and financial analysis. It is distinguished from the other economist positions by the broader scope of respons ...

is Huw Pill

Huw Pill is a British economist, and the chief economist of the Bank of England since September 2021, succceeding Andy Haldane.

Pill studied philosophy, politics and economics at University College, Oxford, and graduated in 1989. He earned a ...

.

See also

*List of British currencies

A variety of currencies are tender in the United Kingdom, its British Overseas Territories, overseas territories and crown dependencies. This list covers all of those currently in circulation.

References

See also

* Sterling area

* Bank ...

* Bank of England Act

Bank of England Act is a stock short title used in the United Kingdom for legislation relating to the Bank of England.

List

*The Bank of England Act 1946 (9 & 10 Geo 6 c 27)

*The Bank of England Act 1998 (c 11)

The Bank of England Acts 1694 to 1 ...

* Bank of England club

The Bank of England club is a nickname in English association football for a football club which has a strong financial backing. It was used to refer to Arsenal, Chelsea, Everton, Aston Villa and Blackpool in the 1930s as well as in recent times ...

* Coins of the pound sterling

The standard circulating coinage of the United Kingdom, British Crown Dependencies and British Overseas Territories is denominated in pennies and pounds sterling ( symbol "£", commercial GBP), and ranges in value from one penny sterling ...

* Financial Sanctions Unit

The Financial Sanctions Unit of the Bank of England formerly administered financial sanctions in the United Kingdom on behalf of HM Treasury. It was in operation since before 1993, when it applied sanctions against the Government of Libya. More ...

* Fractional-reserve banking

Fractional-reserve banking is the system of banking operating in almost all countries worldwide, under which banks that take deposits from the public are required to hold a proportion of their deposit liabilities in liquid assets as a reserve, ...

* Commonwealth banknote-issuing institutions

Commonwealth banknote-issuing institutions also British Empire Paper Currency Issuers comprises a list of public, private, state-owned banks and other government bodies and Currency Boards who issued legal tender: banknotes.

Africa

Biafra

*Bank ...

* Bank of England Museum

The Bank of England Museum, located within the Bank of England in the City of London, is home to a collection of diverse items relating to the history of the Bank and the UK economy from the Bank’s foundation in 1694 to the present day.

The ...

* Deputy Governor of the Bank of England A Deputy Governor of the Bank of England is the holder of one of a small number of senior positions at the Bank of England, reporting directly to the Governor.

According to the original charter of 27 July 1694 the Bank's affairs would be supervis ...

* List of directors of the Bank of England

The Court of Directors of the Bank of England originally consisted of 24 shareholders, of which 8 were replaced every year by new members, i.e. shareholders not already directors of the bank at the time. This is an incomplete list of Bank of Engl ...

Notes

References

Further reading

* , on nationalisation 1945–50, pp 43–76 * Capie, Forrest. ''The Bank of England: 1950s to 1979'' (Cambridge University Press, 2010). xxviii + 890 pp.excerpt and text search

* * Fforde, John. ''The Role of the Bank of England, 1941–1958'' (1992

excerpt and text search

* Francis, John. ''History of the Bank of England: Its Times and Traditions'

excerpt and text search

* Hennessy, Elizabeth. ''A Domestic History of the Bank of England, 1930–1960'' (2008

excerpt and text search

* Kynaston, David. 2017. Till Time's Last Sand: A History of the Bank of England, 1694–2013. Bloomsbury. * Lane, Nicholas. "The Bank of England in the Nineteenth Century." ''History Today'' (Aug 1960) 19#8 pp 535–541. * O'Brien, Patrick K.; Palma, Nuno (2022).

Not an ordinary bank but a great engine of state: The Bank of England and the British economy, 1694–1844

. ''The Economic History Review.'' * Roberts, Richard, and

David Kynaston

David Thomas Anthony Kynaston (; born 30 July 1951 in Aldershot) is an English historian specialising in the social history of England.

Early life and education

Kynaston was educated at Wellington College, Berkshire and New College, Oxford, fr ...

. ''The Bank of England: Money, Power and Influence 1694–1994'' (1995)

* Sayers, R. S. ''The Bank of England, 1891–1944'' (1986excerpt and text search

* Schuster, F. '' The Bank of England and the State'' * Wood, John H. ''A History of Central Banking in Great Britain and the United States'' (Cambridge University Press, 2005)

External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Bank Of England 1694 establishments in EnglandEngland

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

Banks established in 1694

Grade I listed buildings in the City of London

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

Economy of the United Kingdom

HM Treasury

Organisations based in London with royal patronage

Organisations based in the City of London

Public corporations of the United Kingdom with a Royal Charter

Herbert Baker buildings and structures

John Soane buildings

Georgian architecture in London

Neoclassical architecture in London

Grade I listed banks

Leeds Blue Plaques