Asanga on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

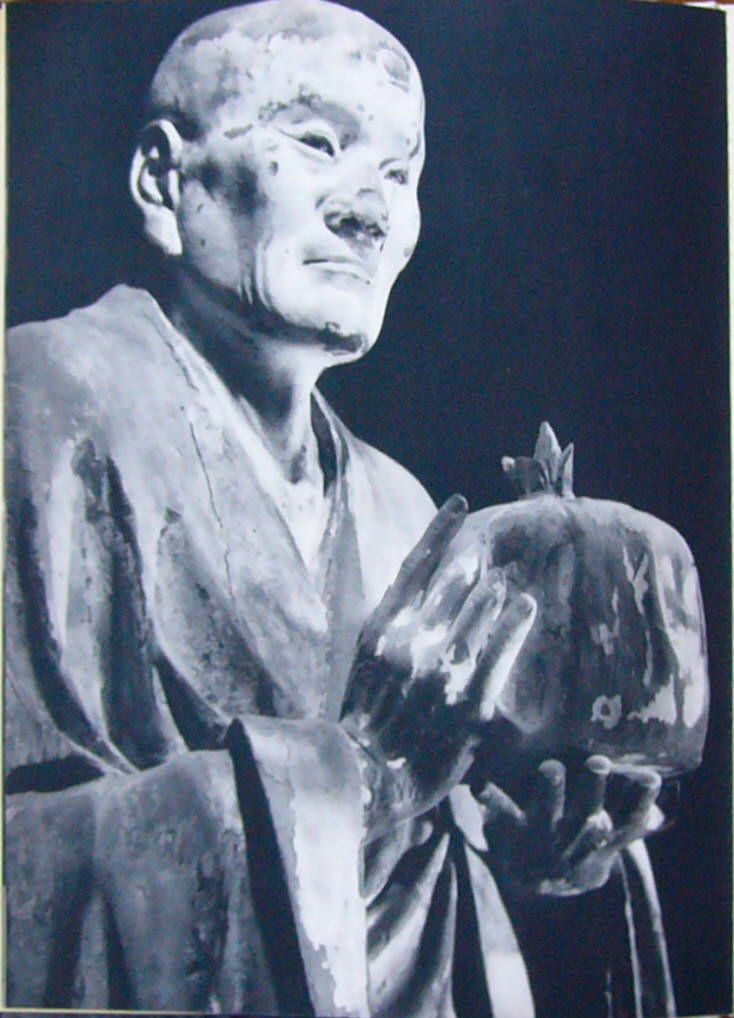

Asaṅga (, ; Romaji: ''Mujaku'') (

Asaṅga (, ; Romaji: ''Mujaku'') (

According to later hagiographies, Asaṅga was born in

According to later hagiographies, Asaṅga was born in

Asaṅga, oxfordbibliographies.com

LAST MODIFIED: 25 NOVEMBER 2014, DOI: 10.1093/OBO/9780195393521-0205. In the record of his journeys through the kingdoms of

''Yogācārabhūmi'', oxfordbibliographies.com

LAST MODIFIED: 26 JULY 2017, DOI: 10.1093/OBO/9780195393521-0248. However, Asaṅga may still have participated in the compilation of this work. The third group of texts associated with Asaṅga comprises two commentaries: the ''Kārikāsaptati'', a work on the '' Vajracchedikā'', and the ''Āryasaṃdhinirmocana-bhāṣya'' (Commentary on the ''Saṃdhinirmocana'')''.'' The attribution of both of these to Asaṅga is not widely accepted by modern scholars.

Asaṅga's Understanding of Mādhyamika: Notes on the Shung-chung-lun

Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 12 (1), 93-108

Digital Dictionary of Buddhism

(type in "guest" as userID)

{{Authority control 4th-century Buddhist monks 4th-century deaths 4th-century Indian philosophers Gandhara Indian Buddhist monks Indian scholars of Buddhism

fl.

''Floruit'' (; abbreviated fl. or occasionally flor.; from Latin for "they flourished") denotes a date or period during which a person was known to have been alive or active. In English, the unabbreviated word may also be used as a noun indicatin ...

4th century C.E.) was "one of the most important spiritual figures" of Mahayana

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing bra ...

Buddhism and the "founder of the Yogachara school".Engle, Artemus (translator), Asanga, ''The Bodhisattva Path to Unsurpassed Enlightenment: A Complete Translation of the Bodhisattvabhumi,'' Shambhala Publications, 2016, Translator's introduction.Rahula, Walpola; Boin-Webb, Sara (translators); Asanga, ''Abhidharmasamuccaya: The Compendium of the Higher Teaching,'' Jain Publishing Company, 2015, p. xiii. He was born in ''Puruṣapura'', modern day Peshawar, Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

. Traditionally, he and his half-brother Vasubandhu are regarded as the major classical Indian Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominalization, nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cul ...

exponents of Mahayana Abhidharma

The Abhidharma are ancient (third century BCE and later) Buddhist texts which contain detailed scholastic presentations of doctrinal material appearing in the Buddhist ''sutras''. It also refers to the scholastic method itself as well as the ...

, ''Vijñanavada'' (awareness only; also called ''Vijñaptivāda'', the doctrine of ideas or percepts, and ''Vijñaptimātratā-vāda'', the doctrine of 'mere representation)) thought and Mahayana teachings on the bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva ( ; sa, 𑀩𑁄𑀥𑀺𑀲𑀢𑁆𑀢𑁆𑀯 (Brahmī), translit=bodhisattva, label=Sanskrit) or bodhisatva is a person who is on the path towards bodhi ('awakening') or Buddhahood.

In the Early Buddhist schoo ...

path.

Biography

Puruṣapura

The history of Peshawar is intertwined with the history of the broader Indian subcontinent. The region was known as ''Puruṣapura'' in Sanskrit, literally meaning "city of men". It also found mention in the Zend Avesta as ''Vaēkərəta'', the s ...

(present day Peshawar in Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

), which at that time was part of the ancient kingdom of Gandhāra.Hattori, Masaaki. “Asaṅga.” In ''Aaron–Attention''. Vol. 1 of ''The Encyclopedia of Religion''. 2d ed. Edited by Lindsay Jones, 516–517. Detroit: Thomson Gale, 2005. Current scholarship places him in the fourth century CE. He was perhaps originally a member of the Mahīśāsaka school or the Mūlasarvāstivāda school but later converted to Mahāyāna. According to some scholars, Asaṅga's frameworks for Abhidharma writings retained many underlying Mahīśāsaka traits, but other scholars argue that there is insufficient data to determine which school he originally belonged to.Lugli, LigeiaAsaṅga, oxfordbibliographies.com

LAST MODIFIED: 25 NOVEMBER 2014, DOI: 10.1093/OBO/9780195393521-0205. In the record of his journeys through the kingdoms of

India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

, Xuanzang

Xuanzang (, ; 602–664), born Chen Hui / Chen Yi (), also known as Hiuen Tsang, was a 7th-century Chinese Buddhist monk, scholar, traveler, and translator. He is known for the epoch-making contributions to Chinese Buddhism, the travelogue of ...

wrote that Asaṅga was initially a Mahīśāsaka monk, but soon turned toward the Mahāyāna teachings.Rongxi, Li (1996). ''The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions.'', Numata Center, Berkeley, p. 153. Asaṅga had a half-brother, Vasubandhu, who was a monk from the Sarvāstivāda school. Vasubandhu is said to have taken up Mahāyāna Buddhism after meeting with Asaṅga and one of Asaṅga's disciples.

Asaṅga spent many years in serious meditation and study under various teachers but the narrative of the 6th century monk Paramārtha states that he was unsatisfied with his understanding. Paramārtha then recounts how he used his meditative powers ( siddhis) to travel to Tuṣita Heaven to receive teachings from Maitreya Bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva ( ; sa, 𑀩𑁄𑀥𑀺𑀲𑀢𑁆𑀢𑁆𑀯 (Brahmī), translit=bodhisattva, label=Sanskrit) or bodhisatva is a person who is on the path towards bodhi ('awakening') or Buddhahood.

In the Early Buddhist schoo ...

on emptiness, and how he continued to travel to receive teachings from Maitreya on the Mahayana sutras.

Xuanzang

Xuanzang (, ; 602–664), born Chen Hui / Chen Yi (), also known as Hiuen Tsang, was a 7th-century Chinese Buddhist monk, scholar, traveler, and translator. He is known for the epoch-making contributions to Chinese Buddhism, the travelogue of ...

(fl. c. 602 – 664), a Chinese monk who traveled to India to study in the Yogacara tradition tells a similar account of these events:

Modern scholars disagree on whether the figure of Maitreya in this story is to be considered as Asaṅga's human teacher or as a visionary experience in meditation. Scholars such as Frauwallner held that this figure, sometimes termed Maitreya-nātha, was an actual historical person and teacher. Other scholars argue that this figure was the tutelary deity of Asaṅga ('' Iṣṭa-devatā'') as well as numerous other Yogacara masters, a point noted by the 6th century Indian monk Sthiramati

Sthiramati (Sanskrit; Chinese:安慧; Tibetan: ''blo gros brtan pa'') or Sāramati was a 6th-century Indian Buddhist scholar-monk. Sthiramati was a contemporary of Dharmapala based primarily in Valābhi university (present-day Gujarat), althoug ...

. Whatever the case, Asaṅga's experiences led him to travel around India and propagate the Mahayana

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing bra ...

teachings. According to Taranatha's ''History of Buddhism in India'', he founded 25 Mahayana monasteries in India.

Among the most famed monasteries that he established was Veluvana in Magadha region of what is now Bihar

Bihar (; ) is a state in eastern India. It is the 2nd largest state by population in 2019, 12th largest by area of , and 14th largest by GDP in 2021. Bihar borders Uttar Pradesh to its west, Nepal to the north, the northern part of West ...

. It was here that he hand-picked eight chosen disciples who would all become famed in their own right and spread the Mahayana.

Works

Asaṅga went on to write some key treatises (shastras) of the Yogācāra school. Over time, many different works were attributed to him (or to Maitreya, with Asaṅga as transmitter), although there are discrepancies between the Chinese and Tibetan traditions concerning which works are attributed to him. Modern scholars have also problematized and questioned these attributions after critical textual study of the sources. The many works attributed to this figure can be divided into the three following groups. The first are three works which are widely agreed by ancient and modern scholars to be by Asaṅga: * '' Mahāyānasaṃgraha'' (Summary of the Great Vehicle), a systematic exposition of the major tenets of the Yogacara school in ten chapters. Considered his magnum opus, survives in one Tibetan and four Chinese translations. * '' Abhidharma-samuccaya,'' a short summary of the main MahayanaAbhidharma

The Abhidharma are ancient (third century BCE and later) Buddhist texts which contain detailed scholastic presentations of doctrinal material appearing in the Buddhist ''sutras''. It also refers to the scholastic method itself as well as the ...

doctrines, in a traditional Buddhist Abhidharma style similar to non-Mahayana expositions. Survives in Sanskrit. According to Walpola Rahula, the thought of this work is closer to that of the Pali ' than is that of the Theravadin Abhidhamma.

* ''Xianyang shengjiao lun,'' variously retranslated into Sanskrit as ''Āryadeśanāvikhyāpana, Āryapravacanabhāṣya, Prakaraṇāryaśāsanaśāstra'', ''Śāsanodbhāvana'', and ''Śāsanasphūrti.'' A work strongly based on the ''Yogācārabhūmi''. Only available in Xuanzang's Chinese translation, but parallel Sanskrit passages can be found in the ''Yogācārabhūmi.''

Attributed works of unsure authorship

The next group of texts are those that Tibetan hagiographies state were taught to Asaṅga by Maitreya and are thus known as the "Five Dharmas of Maitreya" in Tibetan Buddhist scholasticism. According to D.S. Ruegg, the "five works of Maitreya" are mentioned in Sanskrit sources from only the 11th century onwards. As noted by S.K. Hookham, their attribution to a single author has been questioned by modern scholars. The traditional list is: * '' Mahāyānasūtrālamkārakārikā'', ("The Adornment of Mahayana sutras", Tib. ''theg-pa chen-po'i mdo-sde'i rgyan''), which presents the Mahāyāna path from the Yogācāra perspective. * '' Dharmadharmatāvibhāga'' ("Distinguishing Phenomena and Pure Being", Tib. ''chos-dang chos-nyid rnam-par 'byed-pa''), a short Yogācāra work discussing the distinction and correlation (''vibhāga'') between phenomena (''dharma'') and reality (''dharmatā''). * '' Madhyāntavibhāgakārikā'' ("Distinguishing the Middle and the Extremes", Tib. ''dbus-dang mtha' rnam-par 'byed-pa''), 112 verses that are a key work in Yogācāra philosophy. * '' Abhisamayalankara'' ( "Ornament for clear realization", ''Tib. mngon-par rtogs-pa'i rgyan''), a verse text which attempts a synthesis of ''Prajñaparamita'' doctrine and Yogacara thought. There are differing scholarly opinions on authorship, John Makransky writes that it is possible the author was actually Arya Vimuktisena, the 6th century author of the first surviving commentary on this work. Makransky also notes that it is only the later 8th century commentator Haribhadra who attributes this text to Maitreya, but that this may have been a means to ascribe greater authority to the text. As Brunnholzl notes, this text is also completely unknown in the Chinese Buddhist tradition''.''Brunnholzl, Karl'', When the Clouds Part: The Uttaratantra and Its Meditative Tradition as a Bridge between Sutra and Tantra,'' Shambhala Publications, 2015, p. 81. * '' Ratnagotravibhaga'' (Exposition of the Jeweled lineage, Tib. ''theg-pa chen-po rgyud bla-ma'i bstan,'' a.k.a. ''Uttāratantra śāstra)'', a compendium onBuddha-nature

Buddha-nature refers to several related Mahayana Buddhist terms, including '' tathata'' ("suchness") but most notably ''tathāgatagarbha'' and ''buddhadhātu''. ''Tathāgatagarbha'' means "the womb" or "embryo" (''garbha'') of the "thus-go ...

attributed to Maitreya via Asaṅga by the Tibetan tradition. The Chinese tradition attributes it to a certain Sāramati (3rd-4th century CE), according to the Huayan patriarch Fazang. According to S.K. Hookham, modern scholarship favors Sāramati as the author of the RGV. He also notes there is no evidence for the attribution to Maitreya before the time of Maitripa (11th century). Peter Harvey concurs, finding the Tibetan attribution less plausible.

According to Karl Brunnholzl, the Chinese tradition also speaks of five Maitreya texts (first mentioned in Dunlun's ''Yujia lunji''), "but considers them as consisting of the '' Yogācārabhūmi, *Yogavibhāga'' ow lost', Mahāyānasūtrālamkārakā, Madhyāntavibhāga'' and the ''Vajracchedikākāvyākhyā."''

While the '' Yogācārabhūmi śāstra'' (“Treatise on the Levels of Spiritual Practitioners”), a massive and encyclopaedic work on yogic praxis, has traditionally been attributed to Asaṅga or Maitreya '' in toto'', but most modern scholars now consider the text to be a compilation of various works by numerous authors, and different textual strata can be discerned within its contents.Delhey, Martin''Yogācārabhūmi'', oxfordbibliographies.com

LAST MODIFIED: 26 JULY 2017, DOI: 10.1093/OBO/9780195393521-0248. However, Asaṅga may still have participated in the compilation of this work. The third group of texts associated with Asaṅga comprises two commentaries: the ''Kārikāsaptati'', a work on the '' Vajracchedikā'', and the ''Āryasaṃdhinirmocana-bhāṣya'' (Commentary on the ''Saṃdhinirmocana'')''.'' The attribution of both of these to Asaṅga is not widely accepted by modern scholars.

References

Bibliography

* Keenan, John P. (1989)Asaṅga's Understanding of Mādhyamika: Notes on the Shung-chung-lun

Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 12 (1), 93-108

External links

Digital Dictionary of Buddhism

(type in "guest" as userID)

{{Authority control 4th-century Buddhist monks 4th-century deaths 4th-century Indian philosophers Gandhara Indian Buddhist monks Indian scholars of Buddhism