Appalachian Folk Music on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Appalachian music is the music of the region of

Music

," ''Encyclopedia of Appalachia'', 2006. Retrieved: 28 January 2015. Early recorded Appalachian musicians include

Down a Lonesome Road: Dock Boggs' Life in Music

" Extended version of essay in ''Dock Boggs: His Folkways Recordings, 1963–1968'' D liner notes 1998.Stephen Wade, Notes in ''Hobart Smith: In Sacred Trust — The 1963 Fleming Brown Tapes'' D liner notes 2004. Dock Boggs, Doc Carter and

Instruments such as the guitar,

Instruments such as the guitar,  In addition, other instruments used include the

In addition, other instruments used include the

Around the turn of the 20th century, a broad movement developed to record the rich musical heritage, particularly of folksong, that had been preserved and developed by the people of the Appalachians. This music was unwritten; songs were handed down, often within families, from generation to generation by oral transmission. Fieldwork to record Appalachian music (first in musical notation, later on with recording equipment) was undertaken by a variety of scholars.

One of the earliest collectors of Appalachian ballads was Kentucky native

Around the turn of the 20th century, a broad movement developed to record the rich musical heritage, particularly of folksong, that had been preserved and developed by the people of the Appalachians. This music was unwritten; songs were handed down, often within families, from generation to generation by oral transmission. Fieldwork to record Appalachian music (first in musical notation, later on with recording equipment) was undertaken by a variety of scholars.

One of the earliest collectors of Appalachian ballads was Kentucky native  Starting only about a month after Wyman and Brockway, the British folklorists

Starting only about a month after Wyman and Brockway, the British folklorists

In 1923,

In 1923,

Large-scale coal mining arrived in Appalachia in the late 19th century, and brought drastic changes in the lives of those who chose to leave their small farms for wage-paying jobs in coal mining towns. The old ballad tradition that had existed in Appalachia since the arrival of Europeans in the region was readily applied to the

Large-scale coal mining arrived in Appalachia in the late 19th century, and brought drastic changes in the lives of those who chose to leave their small farms for wage-paying jobs in coal mining towns. The old ballad tradition that had existed in Appalachia since the arrival of Europeans in the region was readily applied to the

Appalachia

Appalachia () is a cultural region in the Eastern United States that stretches from the Southern Tier of New York State to northern Alabama and Georgia. While the Appalachian Mountains stretch from Belle Isle in Newfoundland and Labrador, Ca ...

in the Eastern United States

The Eastern United States, commonly referred to as the American East, Eastern America, or simply the East, is the region of the United States to the east of the Mississippi River. In some cases the term may refer to a smaller area or the East C ...

. Traditional Appalachian music is derived from various influences, including the ballad

A ballad is a form of verse, often a narrative set to music. Ballads derive from the medieval French ''chanson balladée'' or ''ballade'', which were originally "dance songs". Ballads were particularly characteristic of the popular poetry and ...

s, hymn

A hymn is a type of song, and partially synonymous with devotional song, specifically written for the purpose of adoration or prayer, and typically addressed to a deity or deities, or to a prominent figure or personification. The word ''hymn'' ...

s and fiddle

A fiddle is a bowed string musical instrument, most often a violin. It is a colloquial term for the violin, used by players in all genres, including classical music. Although in many cases violins and fiddles are essentially synonymous, th ...

music of the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles, ...

(particularly Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

), the African music

Given the vastness of the African continent, its music is diverse, with regions and nations having many distinct musical traditions. African music includes the genres amapiano, Jùjú, Fuji, Afrobeat, Highlife, Makossa, Kizomba, and others. The ...

and blues

Blues is a music genre and musical form which originated in the Deep South of the United States around the 1860s. Blues incorporated spirituals, work songs, field hollers, shouts, chants, and rhymed simple narrative ballads from the Afr ...

of early African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

, and to a lesser extent the music of Continental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous continent of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by ...

.

First recorded in the 1920s, Appalachian musicians were a key influence on the early development of old-time music

Old-time music is a genre of North American folk music. It developed along with various North American folk dances, such as square dancing, clogging, and buck dancing. It is played on acoustic instruments, generally centering on a combinati ...

, country music

Country (also called country and western) is a genre of popular music that originated in the Southern and Southwestern United States in the early 1920s. It primarily derives from blues, church music such as Southern gospel and spirituals, ...

, bluegrass, and rock n' roll, and were an important part of the American folk music revival

The American folk music revival began during the 1940s and peaked in popularity in the mid-1960s. Its roots went earlier, and performers like Josh White, Burl Ives, Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly, Big Bill Broonzy, Billie Holiday, Richard Dyer-Benn ...

of the 1960s. Instruments typically used to perform Appalachian music include the banjo

The banjo is a stringed instrument with a thin membrane stretched over a frame or cavity to form a resonator. The membrane is typically circular, and usually made of plastic, or occasionally animal skin. Early forms of the instrument were fashi ...

, American fiddle

American fiddle-playing began with the early settlers who found that the small ''viol'' family instruments were portable and rugged. According to Ron Yule, "John Utie, a 1620 immigrant, settled in the North and is credited as being the first known ...

, fretted dulcimer, and later the guitar

The guitar is a fretted musical instrument that typically has six strings. It is usually held flat against the player's body and played by strumming or plucking the strings with the dominant hand, while simultaneously pressing selected stri ...

.Ted Olson,Music

," ''Encyclopedia of Appalachia'', 2006. Retrieved: 28 January 2015. Early recorded Appalachian musicians include

Fiddlin' John Carson

"Fiddlin'" John Carson (March 23, 1868 – December 11, 1949) was an American old-time fiddler and singer who recorded what is widely considered to be the first country music song featuring vocals and lyrics.

Early life

Carson was born near Mc ...

, G. B. Grayson & Henry Whitter

William Henry Whitter (April 6, 1892 – November 17, 1941) was an early old-time recording artist in the United States. He first performed as a solo singer, guitarist and harmonica player, and later in partnership with the fiddler G. B. Grayso ...

, Bascom Lamar Lunsford

Bascom Lamar Lunsford (March 21, 1882 – September 4, 1973) was a Folklore studies, folklorist, performer of Appalachian music, traditional Appalachian music, and lawyer from western North Carolina. He was often known by the nickname "Minstrel ...

, the Carter Family

Carter Family was a traditional American folk music group that recorded between 1927 and 1956. Their music had a profound impact on bluegrass, country, Southern Gospel, pop and rock musicians as well as on the U.S. folk revival of the 1960s. ...

, Clarence Ashley, and Dock Boggs

Moran Lee "Dock" Boggs (February 7, 1898 – February 7, 1971) was an American old-time singer, songwriter and banjo player. His style of banjo playing, as well as his singing, is considered a unique combination of Appalachian folk music and Af ...

, all of whom were initially recorded in the 1920s and 1930s. Several Appalachian musicians obtained renown during the folk revival of the 1950s and 1960s, including Jean Ritchie

Jean Ruth Ritchie (December 8, 1922 – June 1, 2015) was an American folk singer, songwriter, and Appalachian dulcimer player, called by some the "Mother of Folk". In her youth she learned hundreds of folk songs in the traditional way (orally ...

, Roscoe Holcomb

Roscoe Holcomb, (born Roscoe Halcomb September 5, 1912 – died February 1, 1981) was an American singer, banjo player, and guitarist from Daisy, Kentucky. A prominent figure in Appalachian folk music, Holcomb was the inspiration for the term ...

, Ola Belle Reed

Ola Belle Reed (August 18, 1916 – August 16, 2002) was an American folk singer, songwriter and banjo player.

Early life

Reed was born Ola Wave Campbell in the unincorporated town of Grassy Creek, Ashe County, North Carolina, to Arthur Camp ...

, Lily May Ledford, Hedy West

Hedwig Grace "Hedy" West (April 6, 1938 – July 3, 2005) was an American folksinger and songwriter. She belonged to the same generation of folk revivalists as Joan Baez and Judy Collins. Her most famous song " 500 Miles" is one of America's ...

and Doc Watson

Arthel Lane "Doc" Watson (March 3, 1923 – May 29, 2012) was an American guitarist, songwriter, and singer of bluegrass, folk, country, blues, and gospel music. Watson won seven Grammy awards as well as a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. W ...

. Country and bluegrass artists such as Loretta Lynn

Loretta Lynn (; April 14, 1932 – October 4, 2022) was an American country music singer and songwriter. In a career spanning six decades, Lynn released multiple gold albums. She had numerous hits such as " You Ain't Woman Enough (To Take My M ...

, Roy Acuff

Roy Claxton Acuff (September 15, 1903 – November 23, 1992) was an American country music singer, fiddler, and promoter. Known as the "King of Country Music", Acuff is often credited with moving the genre from its early string band and "hoedown ...

, Dolly Parton

Dolly Rebecca Parton (born January 19, 1946) is an American singer-songwriter, actress, philanthropist, and businesswoman, known primarily for her work in country music. After achieving success as a songwriter for others, Parton made her album d ...

, Earl Scruggs

Earl Eugene Scruggs (January 6, 1924 – March 28, 2012) was an American musician noted for popularizing a three-finger banjo picking style, now called "Scruggs style", which is a defining characteristic of bluegrass music. His three-fin ...

, Chet Atkins

Chester Burton Atkins (June 20, 1924 – June 30, 2001), known as "Mr. Guitar" and "The Country Gentleman", was an American musician who, along with Owen Bradley and Bob Ferguson, helped create the Nashville sound, the country music s ...

, The Stanley Brothers

The Stanley Brothers were an American bluegrass duo of singer-songwriters and musicians, made up of brothers Carter Stanley (August 27, 1925 – December 1, 1966) and Ralph Stanley (February 25, 1927 – June 23, 2016). Ralph and Carter perfo ...

and Don Reno

Donald Wesley Reno (February 21, 1926Trischka, Tony, "Don Reno", ''Banjo Song Book'', Oak Publications, 1977, – October 16, 1984) was an American bluegrass and country musician, best known as a pioneering banjo and guitar player who pa ...

were heavily influenced by traditional Appalachian music.

History

First immigrants: from the British Isles

Immigrants fromNorthern England

Northern England, also known as the North of England, the North Country, or simply the North, is the northern area of England. It broadly corresponds to the former borders of Angle Northumbria, the Anglo-Scandinavian Kingdom of Jorvik, and the ...

, the Scottish lowlands

The Lowlands ( sco, Lallans or ; gd, a' Ghalldachd, , place of the foreigners, ) is a cultural and historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Lowlands and the Highlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowl ...

, and Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

arrived in Appalachia

Appalachia () is a cultural region in the Eastern United States that stretches from the Southern Tier of New York State to northern Alabama and Georgia. While the Appalachian Mountains stretch from Belle Isle in Newfoundland and Labrador, Ca ...

in the 17th and 18th centuries (with many from Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

being " Ulster Scots", whose ancestors originated from parts of Southern Scotland and Northern England

Northern England, also known as the North of England, the North Country, or simply the North, is the northern area of England. It broadly corresponds to the former borders of Angle Northumbria, the Anglo-Scandinavian Kingdom of Jorvik, and the ...

), including Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th century until 1974. From 19 ...

, and brought with them the musical traditions of these regions, consisting primarily of English and Scottish ballads

A ballad is a form of verse, often a narrative set to music. Ballads derive from the medieval French ''chanson balladée'' or '' ballade'', which were originally "dance songs". Ballads were particularly characteristic of the popular poetry and ...

— which were essentially unaccompanied narratives— and dance music, such as reel

A reel is an object around which a length of another material (usually long and flexible) is wound for storage (usually hose are wound around a reel). Generally a reel has a cylindrical core (known as a '' spool'') with flanges around the ends ...

s, which were accompanied by a fiddle.

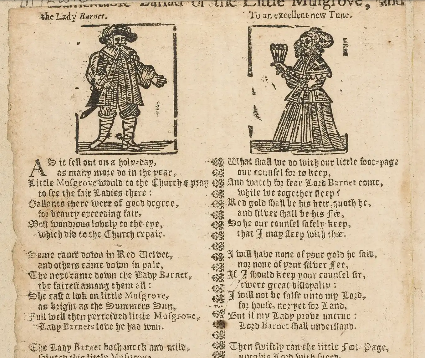

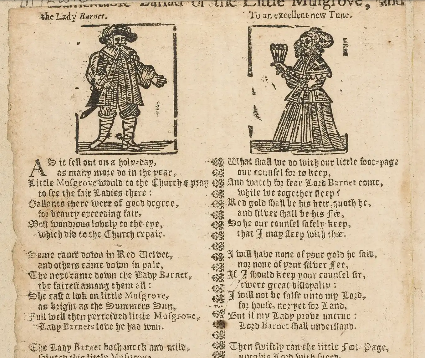

Ballads

Many Appalachian ballads, such as "Pretty Saro

''Pretty Saro'' (Roud 417) is an English folk ballad originating in the early 1700s. The song died out in England by the mid eighteenth century but was rediscovered in North America (particularly in the Appalachian Mountains) in the early twent ...

", " The Cuckoo", "Pretty Polly Pretty Polly may refer to:

* "Pretty Polly" (ballad)

* ''Pretty Polly'' (film)

* ''Pretty Polly'' (opera)

* Pretty Polly (horse)

Pretty Polly (March 1901 – 17 August 1931) was an Irish-bred, British-trained Thoroughbred racehorse and bro ...

", and "Matty Groves

"Matty Groves", also known as "Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard" or "Little Musgrave", is a ballad probably originating in Northern England that describes an adulterous tryst between a young man and a noblewoman that is ended when the woman's ...

", descend from the English ballad tradition and have known antecedents there. Other songs popular in Appalachia, such as "Young Hunting

"Young Hunting" is a traditional folk song, Roud 47, catalogued by Francis James Child as Child Ballad number 68, and has its origin in Scotland. Like most traditional songs, numerous variants of the song exist worldwide, notably under the title ...

," "Lord Randal

"Lord Randall", or "Lord Randal", () is an Anglo- Scottish border ballad consisting of dialogue between a young Lord and his mother. Similar ballads can be found across Europe in many languages, including Danish, German, Magyar, Irish, Swe ...

," and " Barbara Allen", have lowland Scottish

Lowland Scottish Omnibuses Ltd was a bus operator in south eastern Scotland and parts of Northern England. The company was formed in 1985 and operated under the identities Lowland Scottish, Lowland and First Lowland / First SMT, until 1999 when ...

roots. Many of these are versions of the famous Child Ballads

The Child Ballads are 305 traditional ballads from England and Scotland, and their American variants, anthologized by Francis James Child during the second half of the 19th century. Their lyrics and Child's studies of them were published as '' ...

, collected by Francis James Child

Francis James Child (February 1, 1825 – September 11, 1896) was an American scholar, educator, and folklorist, best known today for his collection of English and Scottish ballads now known as the Child Ballads. Child was Boylston professor of ...

in the nineteenth century. The dance tune "Cumberland Gap

The Cumberland Gap is a pass through the long ridge of the Cumberland Mountains, within the Appalachian Mountains, near the junction of the U.S. states of Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee. It is famous in American colonial history for its rol ...

" may be derived from the tune that accompanies the Scottish ballad "Bonnie George Campbell

''Bonnie James Campbell'' or ''Bonnie George Campbell'' is Child ballad 210 (Roud 338). The ballad tells of man who has gone off to fight, but only his horse returns. The name differs across variants. Several names have been suggested as the insp ...

". According to the musicologist Cecil Sharp

Cecil James Sharp (22 November 1859 – 23 June 1924) was an English-born collector of folk songs, folk dances and instrumental music, as well as a lecturer, teacher, composer and musician. He was the pre-eminent activist in the development of t ...

the ballads of Appalachia, including their melodies, were generally most similar to those of "the North of England, or to the Lowlands, rather than the Highlands, of Scotland, as the country from which they he people

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

originally migrated. For the Appalachian tunes...have far more affinity with the normal English folk-tune than with that of the Gaelic

Gaelic is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". As a noun it refers to the group of languages spoken by the Gaels, or to any one of the languages individually. Gaelic languages are spoken in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, and Ca ...

-speaking Highlander."

Fiddle tunes

Several Appalachian fiddle tunes have origins inGaelic

Gaelic is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". As a noun it refers to the group of languages spoken by the Gaels, or to any one of the languages individually. Gaelic languages are spoken in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, and Ca ...

-speaking regions of Ireland and Scotland, for example "Leather Britches," based on "Lord MacDonald's Reel." These may have come to Appalachia via printed versions which were very popular throughout the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

in the eighteenth century, rather than directly from Gaelic areas. The style of the 18th century Scottish fiddler Niel Gow

Niel Gow (1727 – 1 March 1807) was the most famous Scottish fiddler of the eighteenth century.

Early life

Gow was born in Strathbraan, Perthshire, in 1727, as the son of John Gow and Catherine McEwan. The family moved to Inver in Perths ...

, which involved a powerful and rhythmic short bow sawstroke technique, is said to have become the foundation of Appalachian fiddling.

Church music

The early British immigrants also brought a form of church singing calledlining out

Lining out or hymn lining, called precenting the line in Scotland, is a form of a cappella hymn-singing or hymnody in which a leader, often called the clerk or precentor, gives each line of a hymn tune as it is to be sung, usually in a chanted fo ...

or calling out, in which one person sings a line of a psalm or hymn and the rest of the congregation responds. This type of congregational singing, once very common all over colonial America, is now largely restricted to Old Regular Baptist churches in the hills of southwest Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, southern West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

, and eastern Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

.

Continental Europeans

There wereGerman

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

, Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

and Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus'

Places

* Czech, ...

cultural pockets in Appalachia as well as many Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

and French Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Beza ...

immigrants. These cultures largely assimilated, but some songs and melodies, for example the German "Fischer's Hornpipe", remained in the repertoires of their Americanized ancestors. A recording of the fiddler Tommy Jarrell

Thomas Jefferson Jarrell (March 1, 1901 – January 28, 1985) was an American fiddler, banjo player, and singer from the Mount Airy region of North Carolina's Appalachian Mountains.

Biography

He was born in Surry County, North Carolina, Unit ...

playing "Fisher's Hornpipe" can be heard online.

The "Appalachian" or "mountain" dulcimer, thought to have been a modification of a Germanic instrument such as the scheitholt

The scheitholt or scheitholz is a traditional German stringed instrument and an ancestor of the modern zither. It falls into the category of drone zithers.

History

The scheitholt may have derived from an ancient Greek instrument for theoretical ...

, (or possibly the Norwegian langeleik

The ''langeleik'', also called langleik, is a Norwegian stringed folklore musical instrument, a droned zither.

Description

The langeleik has only one melody string and up to 8 drone strings. Under the melody string there are seven frets per o ...

or the French épinette des Vosges) emerged in Southwest Pennsylvania and Northwest Virginia in the 19th century. In the early 20th century, settlement school

Settlement schools are social reform institutions established in rural Appalachia in the early 20th century with the purpose of educating mountain children and improving their isolated rural communities.

Settlement schools have played an importan ...

s in Kentucky taught the fretted dulcimer to students, helping spread its popularity in the region. Jean Ritchie

Jean Ruth Ritchie (December 8, 1922 – June 1, 2015) was an American folk singer, songwriter, and Appalachian dulcimer player, called by some the "Mother of Folk". In her youth she learned hundreds of folk songs in the traditional way (orally ...

was largely responsible for popularizing the instrument among folk music enthusiasts in the 1950s.

Appalachian yodeling

Yodeling (also jodeling) is a form of singing which involves repeated and rapid changes of pitch between the low-pitch chest register (or "chest voice") and the high-pitch head register or falsetto. The English word ''yodel'' is derived from the ...

is thought to have entered the Appalachian mountains in the 18th century, brought by immigrants from Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion#Europe, subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, ...

and Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

, where it was generally used to communicate over longs distances in mountainous terrain similar to the Appalachians. Vocal feathering, practiced by singers including Doug Wallin and described as a "half-yodel", (or more accurately, according to Judith McCulloh

Judith McCulloh (August 16, 1935 – July 13, 2014) was an American folklorist, ethnomusicologist, and university press editor.

Early life and education

McCulloh was born in Spring Valley, Illinois, on August 16, 1935 to Henry and Edna Bink ...

, as 'A sudden or forceful raising of the soft palate against the back wall of the throat and/or a sudden closing of the glottis at the very end of a given note, generally accompanied by a rise in pitch'), may also be Germanic in origin, or alternatively African.

African Americans

One of the most iconic symbols of Appalachian culture— the banjo— was brought to the region byAfrican-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American ...

slaves in the 18th century. It is likely related to West African instruments such as the akonting

The ''akonting'' (, or ''ekonting'' in French transliteration) is the folk lute of the Jola people, found in Senegal, Gambia, and Guinea-Bissau in West Africa. It is a banjo-like instrument with a skin-headed gourd body, two long melody strings ...

.Perryman, Charles W., "Africa, Appalachia, and acculturation: The history of bluegrass music" (2013). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 298. Black banjo players were performing in Appalachia as early as 1798, when their presence was documented in Knoxville, Tennessee

Knoxville is a city in and the county seat of Knox County, Tennessee, Knox County in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2020 United States census, Knoxville's population was 190,740, making it the largest city in the East Tennessee Grand Di ...

.Cecelia Conway, "Appalachian Echoes of the African Banjo". ''Appalachians and Race: The Mountain South from Slavery to Segregation'' (Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2001), pp. 27–32. It is also likely that the guitar was introduced to white Appalachians by African Americans.

Cecil Sharp

Cecil James Sharp (22 November 1859 – 23 June 1924) was an English-born collector of folk songs, folk dances and instrumental music, as well as a lecturer, teacher, composer and musician. He was the pre-eminent activist in the development of t ...

described the practice among white ballad singers of "dwelling arbitrarily upon certain notes of the melody, generally the weakest accents," unaware that this feature was African in origin, being widespread among African Americans and in West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Maurit ...

. In early Appalachia, black and white fiddle

A fiddle is a bowed string musical instrument, most often a violin. It is a colloquial term for the violin, used by players in all genres, including classical music. Although in many cases violins and fiddles are essentially synonymous, th ...

rs would exchange tunes, allowing the rhythms of Africa to influence white fiddle music. African slaves brought a distinct tradition of community songs of work and worship, usually involving call and response

Call and response is a form of interaction between a speaker and an audience in which the speaker's statements ("calls") are punctuated by responses from the listeners. This form is also used in music, where it falls under the general category of ...

, and African percussion rhythms affected the rhythms of Appalachian song and dance.

Early African-American vocal music, probably the ancestor of blues

Blues is a music genre and musical form which originated in the Deep South of the United States around the 1860s. Blues incorporated spirituals, work songs, field hollers, shouts, chants, and rhymed simple narrative ballads from the Afr ...

music, brought harmonic (third and seventh blue notes

In jazz and blues, a blue note is a note that—for expressive purposes—is sung or played at a slightly different pitch from standard. Typically the alteration is between a quartertone and a semitone, but this varies depending on the musical ...

, and sliding tones) and verbal dexterity to Appalachian music, and many early Appalachian musicians, such as Dock Boggs

Moran Lee "Dock" Boggs (February 7, 1898 – February 7, 1971) was an American old-time singer, songwriter and banjo player. His style of banjo playing, as well as his singing, is considered a unique combination of Appalachian folk music and Af ...

and Hobart Smith

Hobart ( ; Nuennonne/Palawa kani: ''nipaluna'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian island state of Tasmania. Home to almost half of all Tasmanians, it is the least-populated Australian state capital city, and second-small ...

, recalled being greatly influenced by watching black musicians perform at the beginning of the twentieth century.Barry O'Connell,Down a Lonesome Road: Dock Boggs' Life in Music

" Extended version of essay in ''Dock Boggs: His Folkways Recordings, 1963–1968'' D liner notes 1998.Stephen Wade, Notes in ''Hobart Smith: In Sacred Trust — The 1963 Fleming Brown Tapes'' D liner notes 2004. Dock Boggs, Doc Carter and

Doc Watson

Arthel Lane "Doc" Watson (March 3, 1923 – May 29, 2012) was an American guitarist, songwriter, and singer of bluegrass, folk, country, blues, and gospel music. Watson won seven Grammy awards as well as a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. W ...

have all been described as "white blues

Blues is a music genre and musical form which originated in the Deep South of the United States around the 1860s. Blues incorporated spirituals, work songs, field hollers, shouts, chants, and rhymed simple narrative ballads from the Afr ...

" musicians due to the presence of African American blues features in their styles.

Later developments

The "New World" ballad tradition, consisting of ballads written in North America, was as influential as the Old World tradition to the development of Appalachian music. New World ballads were typically written to reflect news events of the day, and were often published asbroadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

s. New World ballads popular among Appalachian musicians included "Omie Wise

Omie Wise or Naomi Wise (1789–1808) was an American murder victim, who is remembered by a popular murder ballad about her death.

Song

Omie Wise's death became the subject of a traditional American ballad. (Roud 447) One version opens:

In acc ...

", "Wreck of the Old 97

Wreck or The Wreck may refer to: Common uses

* Wreck, a collision of an automobile, aircraft or other vehicle

* Shipwreck, the remains of a ship after a crisis at sea

Places

* The Wreck (surf spot), a surf spot at Byron Bay, New South Wales, Aus ...

", "Man of Constant Sorrow

"Man of Constant Sorrow" (also known as "I Am a Man of Constant Sorrow") is a traditional American folk song first published by Dick Burnett, a partially blind fiddler from Kentucky. The song was originally titled "Farewell Song" in a songbook ...

," and " John Hardy". Later, coal mining

Coal mining is the process of extracting coal from the ground. Coal is valued for its energy content and since the 1880s has been widely used to generate electricity. Steel and cement industries use coal as a fuel for extraction of iron from ...

and its associated labor issues led to the development of protest songs

A protest song is a song that is associated with a movement for social change and hence part of the broader category of ''topical'' songs (or songs connected to current events). It may be folk, classical, or commercial in genre.

Among social mov ...

, such as "Which Side Are You On?

"Which Side Are You On?" is a song written in 1931 by activist Florence Reece, who was the wife of Sam Reece, a union organizer for the United Mine Workers in Harlan County, Kentucky.

Background

In 1931, the miners and the mine owners in sout ...

" and "Coal Creek March".Stephen Mooney, "Coal-Mining and Protest Music". ''Encyclopedia of Appalachia'' (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), pp. 1136–1137.

Many ballad singers, such as Texas Gladden

Texas Anna Gladden (' Smith, March 14, 1895 – May 23, 1966)

, acquired what is referred to as the "High Lonesome Sound", a strident, nasalized vocal timbre, often with an unmetered rhythm and the use of gapped (i.e. pentatonic

A pentatonic scale is a musical scale (music), scale with five Musical note, notes per octave, in contrast to the heptatonic scale, which has seven notes per octave (such as the major scale and minor scale).

Pentatonic scales were developed ...

) scales. It is unknown exactly when and how this style developed.

Instruments such as the guitar,

Instruments such as the guitar, mandolin

A mandolin ( it, mandolino ; literally "small mandola") is a stringed musical instrument in the lute family and is generally plucked with a pick. It most commonly has four courses of doubled strings tuned in unison, thus giving a total of 8 ...

, and autoharp

An autoharp or chord zither is a string instrument belonging to the zither family. It uses a series of bars individually configured to mute all strings other than those needed for the intended chord. The term ''autoharp'' was once a trademark of ...

became popular in Appalachia in the late 19th century as a result of mail order catalogs. These instruments were added to the banjo

The banjo is a stringed instrument with a thin membrane stretched over a frame or cavity to form a resonator. The membrane is typically circular, and usually made of plastic, or occasionally animal skin. Early forms of the instrument were fashi ...

-and-fiddle

A fiddle is a bowed string musical instrument, most often a violin. It is a colloquial term for the violin, used by players in all genres, including classical music. Although in many cases violins and fiddles are essentially synonymous, th ...

outfits to form early string band

A string band is an old-time music or jazz ensemble made up mainly or solely of string instruments. String bands were popular in the 1920s and 1930s, and are among the forerunners of modern country music and bluegrass. While being active countr ...

s.

In addition, other instruments used include the

In addition, other instruments used include the spoons

Spoons may refer to:

* Spoon, a utensil commonly used with soup

* Spoons (card game), the card game of Donkey, but using spoons

Film and TV

* ''Spoons'' (TV series), a 2005 UK comedy sketch show

*Spoons, a minor character from ''The Sopranos''

...

which are played by hitting two spoons together, making a 'click' sound that creates tempo, and the washboard which the players play by using their hands or thimble to stroke the riffs on the instrument. These are used in place of drums to produce percussion sounds. The washtub bass

The washtub bass, or gutbucket, is a stringed instrument used in American folk music that uses a metal washtub as a resonator. Although it is possible for a washtub bass to have four or more strings and tuning pegs, traditional washtub basses hav ...

is another instrument popular in Appalachian music. Also known as the gutbucket,(or in other countries the "gas-tank bass" or "laundrophone"), it is usually made from a metal wash tub, a staff or stick, and at least one string, although usually four or more strings are used. The Bass may also have tuning pegs. The washtub bass originated in African-Americans communities in Appalachia before being adopted by white string bands.

Collecting and recording

Fieldwork

Around the turn of the 20th century, a broad movement developed to record the rich musical heritage, particularly of folksong, that had been preserved and developed by the people of the Appalachians. This music was unwritten; songs were handed down, often within families, from generation to generation by oral transmission. Fieldwork to record Appalachian music (first in musical notation, later on with recording equipment) was undertaken by a variety of scholars.

One of the earliest collectors of Appalachian ballads was Kentucky native

Around the turn of the 20th century, a broad movement developed to record the rich musical heritage, particularly of folksong, that had been preserved and developed by the people of the Appalachians. This music was unwritten; songs were handed down, often within families, from generation to generation by oral transmission. Fieldwork to record Appalachian music (first in musical notation, later on with recording equipment) was undertaken by a variety of scholars.

One of the earliest collectors of Appalachian ballads was Kentucky native John Jacob Niles

John Jacob Niles (April 28, 1892 – March 1, 1980) was an American composer, singer and collector of traditional ballads. Called the "Dean of American Balladeers," Niles was an important influence on the American folk music revival of the 195 ...

(1892–1980), who began noting ballads as early as 1907 as he learned them in the course of family, social life, and work. Due to fears of plagiarism and imitation of other collectors active in the region at the time, Niles waited until 1960 to publish his first 110 in ''The Ballad Book of John Jacob Niles''. The area covered by Niles in his collecting days, according to the map in the ''Ballad Book'', was bounded roughly by Tazewell, Virginia

Tazewell () is a town in Tazewell County, Virginia, United States. The population was 4,627 at the 2010 census. It is part of the Bluefield, WV-VA micropolitan area, which has a population of 107,578. It is the county seat of Tazewell County.

...

; south to Boone and Saluda, North Carolina

Saluda is a city in Polk and Henderson counties in the U.S. state of North Carolina. The population was 713 at the 2010 census. Saluda is famous for sitting at the top of the Norfolk Southern Railway's Saluda Grade, which was the steepest main li ...

and Greenville, South Carolina

Greenville (; locally ) is a city in and the seat of Greenville County, South Carolina, United States. With a population of 70,720 at the 2020 census, it is the sixth-largest city in the state. Greenville is located approximately halfway be ...

; west to Chickamauga, Georgia

Chickamauga is a city in Walker County, Georgia, Walker County, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia, United States. The population was 2,917 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Chattanooga, Tennessee, Chattanooga, Tennessee, TN–GA Chattanooga metropo ...

; north through Chattanooga

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States. Located along the Tennessee River bordering Georgia, it also extends into Marion County on its western end. With a population of 181,099 in 2020, ...

and Dayton, Tennessee

Dayton is a city and county seat in Rhea County, Tennessee, Rhea County, Tennessee, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the city population was 7,065. The Dayton Urban Cluster, which includes developed areas adjacent ...

to Somerset, Kentucky

Somerset is a home rule-class city in Pulaski County, Kentucky, United States. The city population was 11,924 according to the 2020 census. It is the seat of Pulaski County.

History

Somerset was first settled in 1798 by Thomas Hansford and rec ...

; northwest to Bardstown, Frankfort, and Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington is a city in Kentucky, United States that is the county seat of Fayette County, Kentucky, Fayette County. By population, it is the List of cities in Kentucky, second-largest city in Kentucky and List of United States cities by popul ...

; east to the West Virginia border, and back down to Tazewell, thus covering areas of the Smokies, the Cumberland Plateau

The Cumberland Plateau is the southern part of the Appalachian Plateau in the Appalachian Mountains of the United States. It includes much of eastern Kentucky and Tennessee, and portions of northern Alabama and northwest Georgia. The terms "Alle ...

, Upper Tennessee Valley, and the Lookout Mountain

Lookout Mountain is a mountain ridge located at the northwest corner of the U.S. state of Georgia, the northeast corner of Alabama, and along the southeastern Tennessee state line in Chattanooga. Lookout Mountain was the scene of the 18th-cen ...

region.

In May 1916, the soprano Loraine Wyman

(Julie) Loraine Wyman (October 23, 1885 – September 11, 1937) was an American soprano, noted for her concert performances of folk songs, some of which she collected herself from traditional singers in field work. Paul J. Stamler has called Wyma ...

and her pianist colleague Howard Brockway

Howard A. Brockway (November 22, 1870 – February 20, 1951) was an American composer.

Brockway was born on November 22, 1870 in Brooklyn, New York. He spent five years in Berlin, studying composition under Otis Bardwell Boise and piano und ...

visited the Appalachians in eastern Kentucky, in a 300-mile walking trek to gather folk songs. They took their harvest back to New York, where they continued, with great success, their ongoing efforts in performing traditional folk songs to urban audiences.

Starting only about a month after Wyman and Brockway, the British folklorists

Starting only about a month after Wyman and Brockway, the British folklorists Cecil Sharp

Cecil James Sharp (22 November 1859 – 23 June 1924) was an English-born collector of folk songs, folk dances and instrumental music, as well as a lecturer, teacher, composer and musician. He was the pre-eminent activist in the development of t ...

and Maud Karpeles

Maud Karpeles (12 November 1885 – 1 October 1976) was a British collector of folksongs and dance teacher.

Early life and education

Maud Pauline Karpeles was born at Lancaster Gate in Bayswater, London, in 1885. She was the third of five child ...

toured the Southern Appalachian region, visiting places like Hot Springs

A hot spring, hydrothermal spring, or geothermal spring is a spring produced by the emergence of geothermally heated groundwater onto the surface of the Earth. The groundwater is heated either by shallow bodies of magma (molten rock) or by circ ...

in North Carolina, Flag Pond in Tennessee, Harlan in Kentucky, and Greenbrier County

Greenbrier County () is a county in the U.S. state of West Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 32,977. Its county seat is Lewisburg. The county was formed in 1778 from Botetourt and Montgomery counties in Virginia.

History

P ...

in West Virginia, as well as schools such as Berea College

Berea College is a private liberal arts work college in Berea, Kentucky. Founded in 1855, Berea College was the first college in the Southern United States to be coeducational and racially integrated. Berea College charges no tuition; every a ...

and the Hindman Settlement School

Hindman Settlement School is a settlement school located in Hindman, Kentucky in Knott County. Established in 1902, it was the first rural settlement school in America.

in Kentucky and the Pi Beta Phi settlement school in Gatlinburg, Tennessee

Gatlinburg is a mountain resort city in Sevier County, Tennessee, United States. It is located southeast of Knoxville and had a population of 3,944 at the 2010 Census and a U.S. Census population of 3,577 in 2020. It is a popular vacation res ...

. They persisted for three summers in all (1916-1918), collecting over 200 "Old World" ballads in the region, many of which had varied only slightly from their British Isles counterparts. After their first study in Appalachia, Sharp and Karpeles published '' English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians''.Filene, Benjamin, Romancing the Folk: Public Memory & American Roots Music, University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

Among the ballads Sharp and Karpeles found in Appalachia were medieval-themed songs such as "The Elfin Knight

"The Elfin Knight" () is a traditional Scottish folk ballad of which there are many versions, all dealing with supernatural occurrences, and the commission to perform impossible tasks. The ballad has been collected in different parts of England, ...

" and " Lord Thomas and Fair Ellinor", and seafaring and adventure songs such as "In Seaport Town" and "Young Beichan

"Young Beichan", also known as "Lord Bateman", "Lord Bakeman", "Lord Baker", "Young Bicham" and "Young Bekie", is a traditional folk ballad categorised as Child ballad 53 and Roud 40. The earliest versions date from the late 18th century, but ...

". They transcribed 16 versions of " Barbara Allen" and 22 versions of "The Daemon Lover

"The Daemon Lover" (Roud 14, Child 243) – also known as "James Harris", "A Warning for Married Women", "The Distressed Ship Carpenter", "James Herries", "The Carpenter’s Wife", "The Banks of Italy", or "The House-Carpenter" – is a popular ba ...

" (often called "The House Carpenter" in Appalachia). The work of Sharp and Karpeles confirmed what many folklorists had suspected— the remote valleys and hollows of the Appalachian Mountains were a vast repository of older forms of music.Ted Olson and Ajay Kalra, "Appalachian Music: Examining Popular Assumptions". ''A Handbook to Appalachia: An Introduction to the Region'' (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), pp. 163–170.

Later in the twentieth century, Jean Ritchie

Jean Ruth Ritchie (December 8, 1922 – June 1, 2015) was an American folk singer, songwriter, and Appalachian dulcimer player, called by some the "Mother of Folk". In her youth she learned hundreds of folk songs in the traditional way (orally ...

, Texas Gladden

Texas Anna Gladden (' Smith, March 14, 1895 – May 23, 1966)

, Nimrod Workman, Frank Proffitt

Frank Noah Proffitt (June 1, 1913 – November 24, 1965) was an Appalachian old time banjoist who preserved the song " Tom Dooley" in the form we know it today and was a key figure in inspiring musicians of the 1960s and 1970s to play the trad ...

and Horton Barker and many others were recorded singing traditional songs and ballads learnt in the oral tradition.

Commercial recordings

Only a few years after folk music fieldwork had begun to flourish, the commercial recording industry had developed to the point that recording Appalachian music for popular consumption had become a viable enterprise.Williams, Michelle Ann (1995) ''Great Smoky Mountains Folk Life''. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, p. 58 In 1923,

In 1923, OKeh Records

Okeh Records () is an American record label founded by the Otto Heinemann Phonograph Corporation, a phonograph supplier established in 1916, which branched out into phonograph records in 1918. The name was spelled "OkeH" from the initials of Ott ...

talent scout Ralph Peer

Ralph Sylvester Peer (May 22, 1892 – January 19, 1960) was an American talent scout, recording engineer, record producer and music publisher in the 1920s and 1930s. Peer pioneered field recording of music when in June 1923 he took remote rec ...

held the first recording sessions for Appalachian regional musicians in Atlanta, Georgia

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,715 ...

. Musicians recorded at these sessions included Fiddlin' John Carson

"Fiddlin'" John Carson (March 23, 1868 – December 11, 1949) was an American old-time fiddler and singer who recorded what is widely considered to be the first country music song featuring vocals and lyrics.

Early life

Carson was born near Mc ...

, a champion fiddle player from North Georgia

North Georgia is the northern hilly/mountainous region in the U.S. state of Georgia. At the time of the arrival of settlers from Europe, it was inhabited largely by the Cherokee. The counties of north Georgia were often scenes of important eve ...

. The commercial success of the Atlanta sessions prompted OKeh to seek out other musicians from the region, including Henry Whitter, who was recorded in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

in 1924. The following year, Peer recorded a North Carolina string band fronted by Al Hopkins that called themselves "a bunch of hillbillies." Peer applied the name to the band, and the success of the band's recordings led to the term "Hillbilly music" being applied to Appalachian string band music.

In 1927, Peer, then working for the Victor Talking Machine Company

The Victor Talking Machine Company was an American recording company and phonograph manufacturer that operated independently from 1901 until 1929, when it was acquired by the Radio Corporation of America and subsequently operated as a subsidi ...

, held a series of recording sessions at Bristol, Tennessee that to many music historians mark the beginning of commercial country music. Musicians recorded at Bristol included the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers

James Charles Rodgers (September 8, 1897 – May 26, 1933) was an American singer-songwriter and musician who rose to popularity in the late 1920s. Widely regarded as "the Father of Country Music", he is best known for his distinctive rhythmi ...

. Other record companies, such as Columbia Records

Columbia Records is an American record label owned by Sony Music, Sony Music Entertainment, a subsidiary of Sony Corporation of America, the North American division of Japanese Conglomerate (company), conglomerate Sony. It was founded on Janua ...

and ARC, followed Peer's lead and held similar recording sessions. Many early Appalachian musicians, including Clarence Ashley and Dock Boggs, experienced a moderate level of success. The onset of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

in the early 1930s, however, reduced demand for recorded music, and most of these musicians fell back into obscurity.

Folk revival

In the 1930s, radio programs such as theGrand Ole Opry

The ''Grand Ole Opry'' is a weekly American country music stage concert in Nashville, Tennessee, founded on November 28, 1925, by George D. Hay as a one-hour radio "barn dance" on WSM. Currently owned and operated by Opry Entertainment (a divis ...

kept interest in Appalachian music alive, and collectors such as musicologist Alan Lomax

Alan Lomax (; January 31, 1915 – July 19, 2002) was an American ethnomusicologist, best known for his numerous field recordings of folk music of the 20th century. He was also a musician himself, as well as a folklorist, archivist, writer, sch ...

continued to make field recordings in the region throughout the 1940s. In 1952, Folkways Records

Folkways Records was a record label founded by Moses Asch that documented folk, world, and children's music. It was acquired by the Smithsonian Institution in 1987 and is now part of Smithsonian Folkways.

History

The Folkways Records & Service ...

released the landmark '' Anthology of American Folk Music'', which had been compiled by ethnomusicologist Harry Smith, and contained tracks from Appalachian musicians such as Clarence Ashley, Dock Boggs

Moran Lee "Dock" Boggs (February 7, 1898 – February 7, 1971) was an American old-time singer, songwriter and banjo player. His style of banjo playing, as well as his singing, is considered a unique combination of Appalachian folk music and Af ...

, and G. B. Grayson. The compilation helped inspire the folk music revival of the 1950s and 1960s. Urban folk enthusiasts such as New Lost City Ramblers bandmates Mike Seeger

Mike Seeger (August 15, 1933August 7, 2009) was an American folk musician and folklorist. He was a distinctive singer and an accomplished musician who played autoharp, banjo, fiddle, dulcimer, guitar, mouth harp, mandolin, dobro, jaw harp, a ...

and John Cohen and producer Ralph Rinzler

Ralph Rinzler (July 20, 1934 – July 2, 1994) was an American mandolin player, folksinger, and the co-founder of the annual Smithsonian Folklife Festival on the Mall every summer in Washington, D.C., where he worked as a curator for American a ...

traveled to remote sections of Appalachia to conduct field recordings. Along with recording and re-recordings of older Appalachian musicians and the discovery of newer musicians, the folk revivalists conducted extensive interviews with these musicians to determine their musical backgrounds and the roots of their styles and repertoires.Jeff Place, Notes to ''Classic Mountain Songs from Smithsonian Folkways'' D liner notes 2002. Appalachian musicians became regulars at folk music festivals from the Newport Folk Festival

Newport Folk Festival is an annual American folk-oriented music festival in Newport, Rhode Island, which began in 1959 as a counterpart to the Newport Jazz Festival. It was one of the first modern music festivals in America, and remains a foca ...

to folk festivals at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

and the University of California at Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant univ ...

. Films such as Cohen's ''High Lonesome Sound''— the subject of which was Kentucky banjoist and ballad singer Roscoe Holcomb

Roscoe Holcomb, (born Roscoe Halcomb September 5, 1912 – died February 1, 1981) was an American singer, banjo player, and guitarist from Daisy, Kentucky. A prominent figure in Appalachian folk music, Holcomb was the inspiration for the term ...

— helped give enthusiasts a sense of what it was like to see Appalachian musicians perform.

Coal mining and protest music

Large-scale coal mining arrived in Appalachia in the late 19th century, and brought drastic changes in the lives of those who chose to leave their small farms for wage-paying jobs in coal mining towns. The old ballad tradition that had existed in Appalachia since the arrival of Europeans in the region was readily applied to the

Large-scale coal mining arrived in Appalachia in the late 19th century, and brought drastic changes in the lives of those who chose to leave their small farms for wage-paying jobs in coal mining towns. The old ballad tradition that had existed in Appalachia since the arrival of Europeans in the region was readily applied to the social problems

A social issue is a problem that affects many people within a society. It is a group of common problems in present-day society and ones that many people strive to solve. It is often the consequence of factors extending beyond an individual's cont ...

common in late 19th-century and early 20th-century mining towns— low pay, mine disasters, and strikes. One of the earliest mining-related songs from Appalachia was "Coal Creek March," which was influenced by the 1891 Coal Creek War

The Coal Creek War was an early 1890s armed labor uprising in the southeastern United States that took place primarily in Anderson County, Tennessee. This labor conflict ignited during 1891 when coal mine owners in the Coal Creek watershed beg ...

in Anderson County, Tennessee

Anderson County is a county in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is located in the northern part of the state in East Tennessee. As of the 2020 census, its population was 77,123. Its county seat is Clinton. Anderson County is included in the Kn ...

. Mine labor strife in West Virginia in 1914 and the 1931 Harlan County War

The Harlan County War, or Bloody Harlan, was a series of coal industry skirmishes, executions, bombings and strikes (both attempted and realized) that took place in Harlan County, Kentucky, during the 1930s. The incidents involved coal miners ...

in Kentucky produced songs such as Ralph Chaplin's "Solidarity Forever

"Solidarity Forever", written by Ralph Chaplin in 1915, is a popular trade union anthem. It is sung to the tune of " John Brown's Body" and "The Battle Hymn of the Republic". Although it was written as a song for the Industrial Workers of the W ...

" and Florence Reece

Florence Reece (April 12, 1900 – August 3, 1986) was an American social activist, poet, and folksong writer. She is best known for the song " Which Side Are You On?" which she originally wrote at the age of twelve while her father was out ...

's "Which Side Are You On?

"Which Side Are You On?" is a song written in 1931 by activist Florence Reece, who was the wife of Sam Reece, a union organizer for the United Mine Workers in Harlan County, Kentucky.

Background

In 1931, the miners and the mine owners in sout ...

" respectively. George Korson

George Korson (August 8, 1899 – May 23, 1967) was a folklorist, journalist, and historian. He has been cited as a pioneer collector of industrial folklore, and according to Michael Taft of the Library of Congress, "may very well be considered ...

made field recordings of miners' songs in 1940 for The Library of Congress. The most commercially successful Appalachian mining song is Merle Travis' "Sixteen Tons

"Sixteen Tons" is a song written by Merle Travis about a coal miner, based on life in the mines of Muhlenberg County, Kentucky. Travis first recorded the song at the Radio Recorders Studio B in Hollywood, California, on August 8, 1946. Cliff ...

," which has been recorded by Tennessee Ernie Ford

Ernest Jennings Ford (February 13, 1919 – October 17, 1991), known professionally as Tennessee Ernie Ford, was an American singer and television host who enjoyed success in the country and western, pop, and gospel musical genres. Noted for h ...

, Johnny Cash

John R. Cash (born J. R. Cash; February 26, 1932 – September 12, 2003) was an American country singer-songwriter. Much of Cash's music contained themes of sorrow, moral tribulation, and redemption, especially in the later stages of his ca ...

, and dozens of other artists. Other notable coal mining songs include Jean Ritchie's "The L&N Don't Stop Here Anymore," Sarah Ogan Gunning

Sarah Ogan Gunning (June 28, 1910 – November 14, 1983) was an American singer and songwriter from the coal mining country of eastern Kentucky, as were her older half-sister Aunt Molly Jackson and her brother Jim Garland. Although she made an ...

's "Come All You Coal Miners," and Hazel Dickens

Hazel Jane Dickens (June 1, 1925 – April 22, 2011) was an American bluegrass singer, songwriter, double bassist and guitarist. Her music was characterized not only by her high, lonesome singing style, but also by her provocative pro- unio ...

' "Clay County Miner." Both classic renditions and contemporary covers are included in Jack Wright's 2007 compilation album

A compilation album comprises Album#Tracks, tracks, which may be previously released or unreleased, usually from several separate recordings by either one or several Performing arts#Performers, performers. If by one artist, then generally the tr ...

, ''Music of Coal

''Music of Coal: Mining Songs from the Appalachian Coalfields'' is a 70-page book and two CD compilation of old and new music from southern Appalachian Eastern Mountain Coal Fields, coalfields. The project was produced by Jack Wright (musician), ...

.''

In 1990 they started to use a new type of mining called Mountain Top Removal

Mountaintop removal mining (MTR), also known as mountaintop mining (MTM), is a form of surface mining at the summit or summit ridge of a mountain. Coal seams are extracted from a mountain by removing the land, or overburden, above the seams. T ...

(MTR). That upset a lot of people who lived in Appalachia due to the belief that mountains were holy spaces and that they were a gift from God. Some people showed these feelings through the music. Some example are Todd Burge's "What Would Moses Climb", Donna Price and Greg Treadway's "The Mountains of Home", Jean Ritchie

Jean Ruth Ritchie (December 8, 1922 – June 1, 2015) was an American folk singer, songwriter, and Appalachian dulcimer player, called by some the "Mother of Folk". In her youth she learned hundreds of folk songs in the traditional way (orally ...

’s "Now Is the Cool of the Day", Shirley Stewart Burns's "Leave Those Mountains Down", and Rising Appalachia

Rising Appalachia is an American Appalachian folk music group led by multi-instrumentalist sisters Leah Song and Chloe Smith. Leah also performs as a solo artist. Based between Atlanta, New Orleans, and the Asheville area of North Carolina, the ...

's "Scale Down." Many of the songs featured a cappella and string-band sounds to give them a traditional feel.

Influence

Country music

The Bristol sessions of 1927 have been called the "Big Bang of Country Music," as some music historians have considered them the beginning of the modern country music genre. The popularity of such musicians as the Carter Family, who first recorded at the sessions, proved to industry executives that there was a market for "mountain" or "hillbilly" music. Other influential 1920s-era location recording sessions in Appalachia were the Johnson City sessions and the Knoxville sessions. Early recorded country music (i.e., late 1920s and early 1930s) typically consisted of fiddle and banjo players and a predominant string band format, reflecting its Appalachian roots. Due in large part to the success of the Grand Ole Opry, the center of country music had shifted to Nashville by 1940. In subsequent decades, as the country music industry tried to move into the mainstream, musicians and industry executives sought to deemphasize the genre's Appalachian connections, most notably by dropping the term "hillbilly music" in favor of "country." In the late 1980s, artists such asDolly Parton

Dolly Rebecca Parton (born January 19, 1946) is an American singer-songwriter, actress, philanthropist, and businesswoman, known primarily for her work in country music. After achieving success as a songwriter for others, Parton made her album d ...

, Ricky Skaggs

Rickie Lee Skaggs (born July 18, 1954), known professionally as Ricky Skaggs, is an American neotraditional country and bluegrass singer, musician, producer, and composer. He primarily plays mandolin; however, he also plays fiddle, guitar, ma ...

, and Dwight Yoakam

Dwight David Yoakam (born October 23, 1956) is an American singer-songwriter, actor, and film director. He first achieved mainstream attention in 1986 with the release of his debut album ''Guitars, Cadillacs, Etc., Etc.''. Yoakam had considerabl ...

helped to bring traditional Appalachian influences back to country music.

Bluegrass

Bluegrass developed in the 1940s from a mixture of several types of music, including old-time, country, and blues, but particularly mountainstring band

A string band is an old-time music or jazz ensemble made up mainly or solely of string instruments. String bands were popular in the 1920s and 1930s, and are among the forerunners of modern country music and bluegrass. While being active countr ...

s, which in turn evolved from banjo

The banjo is a stringed instrument with a thin membrane stretched over a frame or cavity to form a resonator. The membrane is typically circular, and usually made of plastic, or occasionally animal skin. Early forms of the instrument were fashi ...

-and-fiddle

A fiddle is a bowed string musical instrument, most often a violin. It is a colloquial term for the violin, used by players in all genres, including classical music. Although in many cases violins and fiddles are essentially synonymous, th ...

outfits. The music's creation is often credited to Bill Monroe

William Smith "Bill" Monroe (; September 13, 1911 – September 9, 1996) was an American mandolinist, singer, and songwriter, who created the bluegrass music genre. Because of this, he is often called the " Father of Bluegrass".

The genre take ...

and his band, the Blue Grass Boys

William Smith "Bill" Monroe (; September 13, 1911 – September 9, 1996) was an American mandolinist, singer, and songwriter, who created the bluegrass music genre. Because of this, he is often called the " Father of Bluegrass".

The genre take ...

. One of the defining characteristics of bluegrass—the fast-paced three-finger banjo picking style—was developed by Monroe's banjo player, North Carolina native Earl Scruggs

Earl Eugene Scruggs (January 6, 1924 – March 28, 2012) was an American musician noted for popularizing a three-finger banjo picking style, now called "Scruggs style", which is a defining characteristic of bluegrass music. His three-fin ...

. Later, as a member of Flatt and Scruggs

Flatt and Scruggs were an American bluegrass duo. Singer and guitarist Lester Flatt and banjo player Earl Scruggs, both of whom had been members of Bill Monroe's band, the Bluegrass Boys, from 1945 to 1948, formed the duo in 1948. Flatt and Scru ...

and the Foggy Mountain Boys, Scruggs wrote Foggy Mountain Breakdown

"Foggy Mountain Breakdown" is a bluegrass instrumental, in the common "breakdown" format, written by Earl Scruggs and first recorded on December 11, 1949, by the bluegrass artists Flatt & Scruggs and the Foggy Mountain Boys. It is a standard i ...

, one of the most well-known bluegrass instrumentals. Bluegrass quickly grew in popularity among numerous musicians in Appalachia, including the Stanley Brothers

The Stanley Brothers were an American bluegrass duo of singer-songwriters and musicians, made up of brothers Carter Stanley (August 27, 1925 – December 1, 1966) and Ralph Stanley (February 25, 1927 – June 23, 2016). Ralph and Carter perfo ...

, the Osborne Brothers

The Osborne Brothers, Sonny (October 29, 1937 – October 24, 2021) and Bobby (born December 7, 1931), were an influential and popular bluegrass act during the 1960s and 1970s and until Sonny retired in 2005. They are probably best known for ...

, and Jimmy Martin

James Henry Martin (August 10, 1927 – May 14, 2005) was an American bluegrass musician, known as the "King of Bluegrass".

Early years

Martin was born in Sneedville, Tennessee, United States, and was raised in the hard farming life of rural ...

, and although it was influenced by various music forms from inside and outside the region (Monroe himself was from Western Kentucky), it is often associated with Appalachia and performed alongside old-time and traditional music at Appalachian folk festivals.

Popular music

Appalachian music has also influenced a number of musicians from outside the region. In 1957, Britishskiffle

Skiffle is a genre of folk music with influences from American folk music, blues, country, bluegrass, and jazz, generally performed with a mixture of manufactured and homemade or improvised instruments. Originating as a form in the United State ...

artist Lonnie Donegan

Anthony James Donegan (29 April 1931 – 3 November 2002), known as Lonnie Donegan, was a British skiffle singer, songwriter and musician, referred to as the " King of Skiffle", who influenced 1960s British pop and rock musicians. Born in Scot ...

reached the top of the U.K. charts with his version of the Appalachian folk song "Cumberland Gap

The Cumberland Gap is a pass through the long ridge of the Cumberland Mountains, within the Appalachian Mountains, near the junction of the U.S. states of Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee. It is famous in American colonial history for its rol ...

," and the following year the Kingston Trio

The Kingston Trio is an American folk and pop music group that helped launch the folk revival of the late 1950s to the late 1960s. The group started as a San Francisco Bay Area nightclub act with an original lineup of Dave Guard, Bob Shane, ...

had a number one hit on the U.S. charts with their rendition of the North Carolina ballad, " Tom Dooley". Grateful Dead

The Grateful Dead was an American rock music, rock band formed in 1965 in Palo Alto, California. The band is known for its eclectic style, which fused elements of rock, Folk music, folk, country music, country, jazz, bluegrass music, bluegrass, ...

member Jerry Garcia frequently performed Appalachian songs such as " Shady Grove" and "Wind and Rain", and said he had learned the clawhammer

Clawhammer, sometimes called down-picking, overhand, or frailing, is a distinctive banjo playing style and a common component of American old-time music.

The principal difference between clawhammer style and other styles is the picking direct ...

banjo style from "listening to Clarence Ashley". Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan (legally Robert Dylan, born Robert Allen Zimmerman, May 24, 1941) is an American singer-songwriter. Often regarded as one of the greatest songwriters of all time, Dylan has been a major figure in popular culture during a career sp ...

, who also performed a number of Appalachian folk songs, considered Roscoe Holcomb

Roscoe Holcomb, (born Roscoe Halcomb September 5, 1912 – died February 1, 1981) was an American singer, banjo player, and guitarist from Daisy, Kentucky. A prominent figure in Appalachian folk music, Holcomb was the inspiration for the term ...

to be "one of the best," and guitarist Eric Clapton

Eric Patrick Clapton (born 1945) is an English rock and blues guitarist, singer, and songwriter. He is often regarded as one of the most successful and influential guitarists in rock music. Clapton ranked second in ''Rolling Stone''s list of ...

considered Holcomb a "favorite" country musician.

Classical music

Classical composersLamar Stringfield

Lamar Edwin Stringfield (October 10, 1897 – January 21, 1959) was a classical composer, flutist, symphony conductor, and anthologist of American folk music.

Early career

He was born in Raleigh, North Carolina and studied at Mars Hill College n ...

and Kurt Weill

Kurt Julian Weill (March 2, 1900April 3, 1950) was a German-born American composer active from the 1920s in his native country, and in his later years in the United States. He was a leading composer for the stage who was best known for his fru ...

have used Appalachian folk music in their compositions, and the region was the setting for Aaron Copland

Aaron Copland (, ; November 14, 1900December 2, 1990) was an American composer, composition teacher, writer, and later a conductor of his own and other American music. Copland was referred to by his peers and critics as "the Dean of American Com ...

's ''Appalachian Spring

''Appalachian Spring'' is a musical composition by Aaron Copland that was premiered in 1944 and has achieved widespread and enduring popularity as an orchestral suite. The music, scored for a thirteen-member chamber orchestra, was created upon c ...

''.

Film

In the early 21st century, the motion picture ''O Brother, Where Art Thou?

''O Brother, Where Art Thou?'' is a 2000 comedy drama film written, produced, co-edited, and directed by Joel and Ethan Coen. It stars George Clooney, John Turturro, and Tim Blake Nelson, with Chris Thomas King, John Goodman, Holly Hunter, and ...

'', and to a lesser extent ''Songcatcher

''Songcatcher'' is a 2000 drama film directed by Maggie Greenwald. It is about a musicologist researching and collecting Appalachian folk music in the mountains of western North Carolina. Although ''Songcatcher'' is a fictional film, it is loosely ...

'' and '' Cold Mountain'', generated renewed mainstream interest in traditional Appalachian music.

Festivals

Every year, numerous festivals are held through the Appalachian region, and throughout the world, to celebrate Appalachian music and related forms of music. One of the oldest is the Ole Time Fiddler's and Bluegrass Festival (known as "Fiddler's Grove") in Union Grove, North Carolina, which has been held continuously since 1924. It is held each year onMemorial Day

Memorial Day (originally known as Decoration Day) is a federal holiday in the United States for mourning the U.S. military personnel who have fought and died while serving in the United States armed forces. It is observed on the last Monda ...

weekend. In 1928, Appalachian musician and collector Bascom Lamar Lunsford

Bascom Lamar Lunsford (March 21, 1882 – September 4, 1973) was a Folklore studies, folklorist, performer of Appalachian music, traditional Appalachian music, and lawyer from western North Carolina. He was often known by the nickname "Minstrel ...

, a native banjo player and fiddler of the North Carolina mountains, organized the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival, which is held annually in Asheville, North Carolina

Asheville ( ) is a city in, and the county seat of, Buncombe County, North Carolina. Located at the confluence of the French Broad and Swannanoa rivers, it is the largest city in Western North Carolina, and the state's 11th-most populous cit ...

on the first weekend in August. Every September, Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

hosts the old-time music festival, Rhythm & Roots Reunion. The American Folk Music Festival, established by Jean Bell Thomas