Anthony Chenevix-Trench on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anthony Chenevix-Trench (10 May 1919 – 21 June 1979) was a British schoolteacher and classics scholar. He was born in

He was housed in

He was housed in

Chenevix-Trench started his military career as an officer cadet at Aldershot, taking the technical and organisational teaching seriously but the remainder less so: "In these pre-

Chenevix-Trench started his military career as an officer cadet at Aldershot, taking the technical and organisational teaching seriously but the remainder less so: "In these pre-

British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

, educated at Shrewsbury School

Shrewsbury School is a public school (English independent boarding school for pupils aged 13 –18) in Shrewsbury.

Founded in 1552 by Edward VI by Royal Charter, it was originally a boarding school for boys; girls have been admitted into the ...

and Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church ( la, Ædes Christi, the temple or house, '' ædēs'', of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, the college is uniqu ...

, and served in the Second World War as an artillery officer with British Indian units in Malaya. Captured by the Japanese in Singapore, he was forced to work on the Burma Railway

The Burma Railway, also known as the Siam–Burma Railway, Thai–Burma Railway and similar names, or as the Death Railway, is a railway between Ban Pong, Thailand and Thanbyuzayat, Burma (now called Myanmar). It was built from 1940 to 1943 ...

.

He taught classics

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

at Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , also ) is a market town, civil parish, and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, north-west of London; at the 2021 census, it had a population of 76,782. The town's name can be pronounced as either 'Sh ...

, where he became a housemaster

{{refimprove, date=September 2018

In British education, a housemaster is a schoolmaster in charge of a boarding house, normally at a boarding school and especially at a public school. The housemaster is responsible for the supervision and care o ...

, and taught for another year at Christ Church. He was headmaster of Bradfield College

Bradfield College, formally St Andrew's College, Bradfield, is a public school (English independent day and boarding school) for pupils aged 11–18, located in the small village of Bradfield in the English county of Berkshire. It is note ...

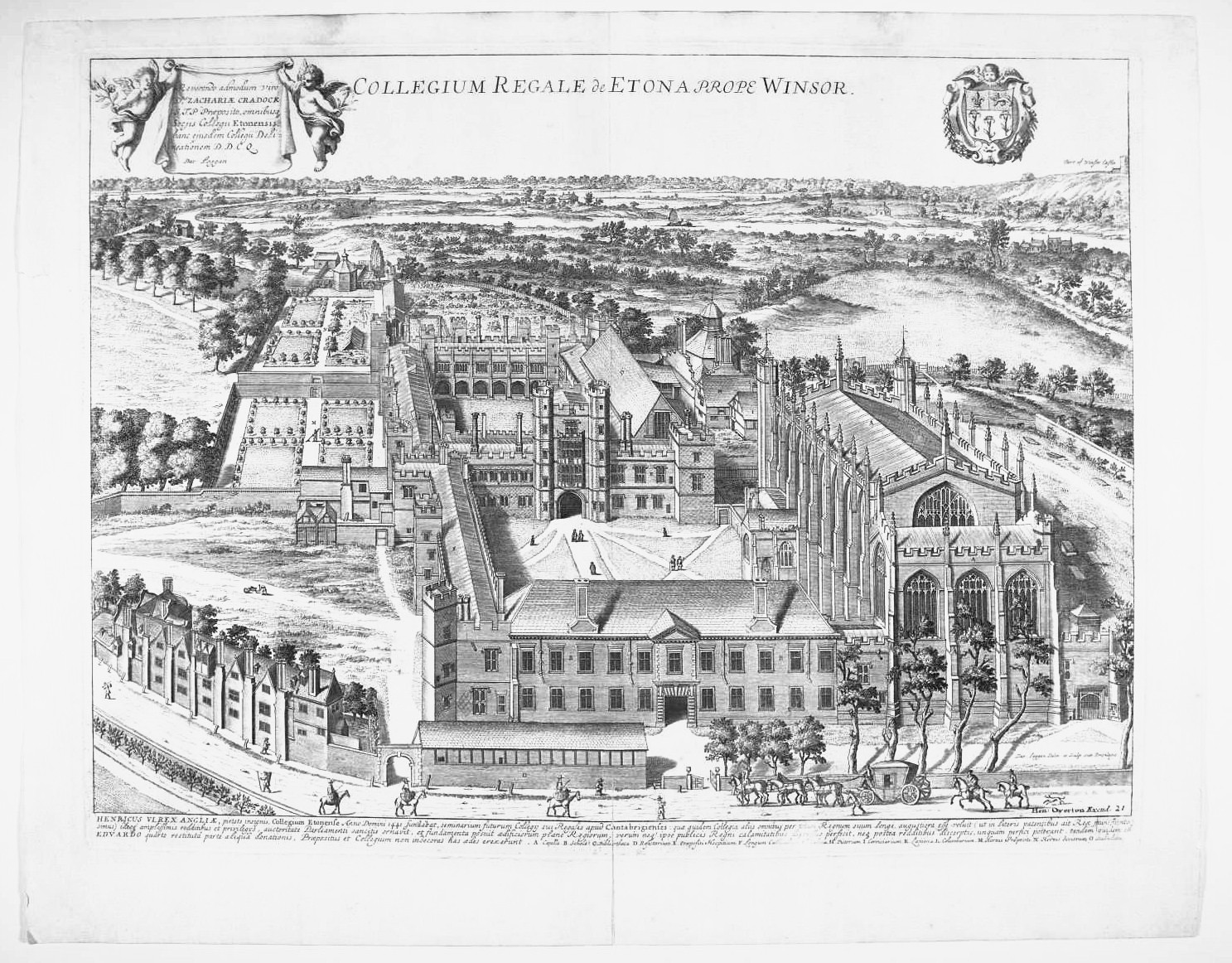

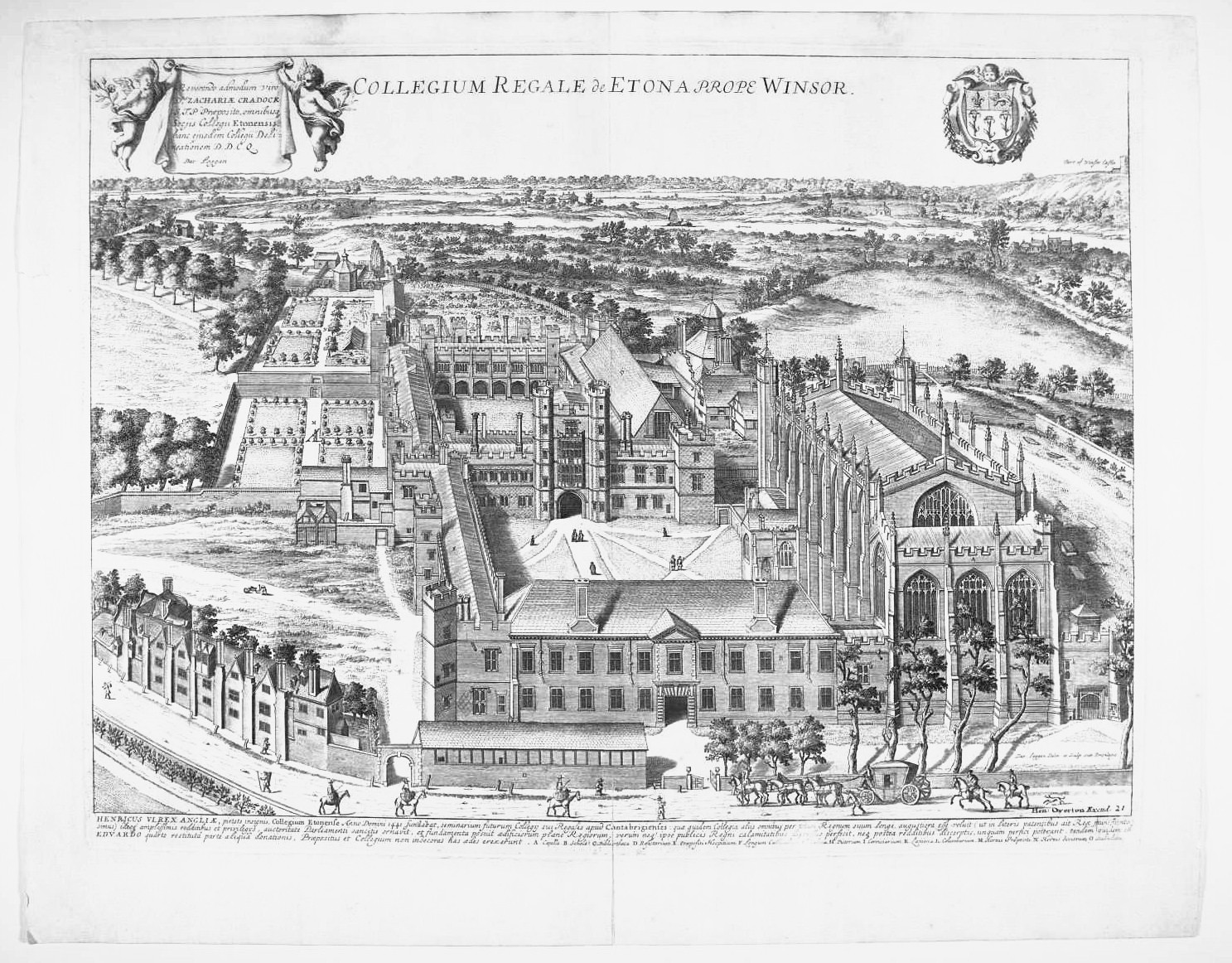

, where he raised academic standards and instituted a substantial programme of new building works. Appointed headmaster of Eton College

Eton College () is a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. intended as a sister institution to King's College, C ...

in 1963, he broadened the curriculum immensely and introduced a greater focus on achieving strong examination results, but was asked to leave in 1969 after disagreements with housemasters and an unpopular attitude to caning

Caning is a form of corporal punishment consisting of a number of hits (known as "strokes" or "cuts") with a single Stick-fighting, cane usually made of rattan, generally applied to the offender's bare or clothed buttocks (see spanking) or ha ...

, which became the subject of a press controversy after his death.

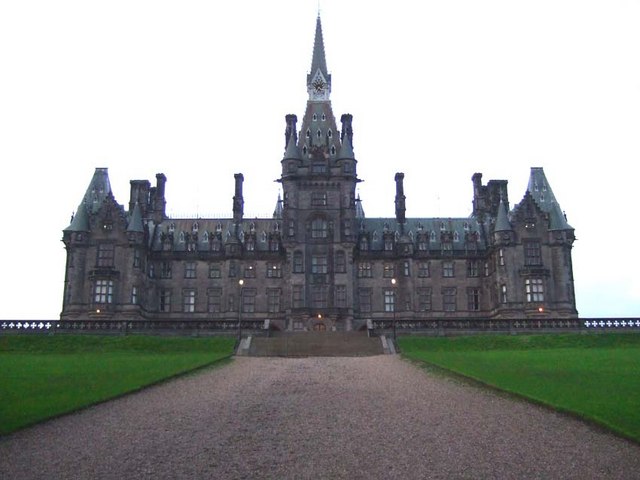

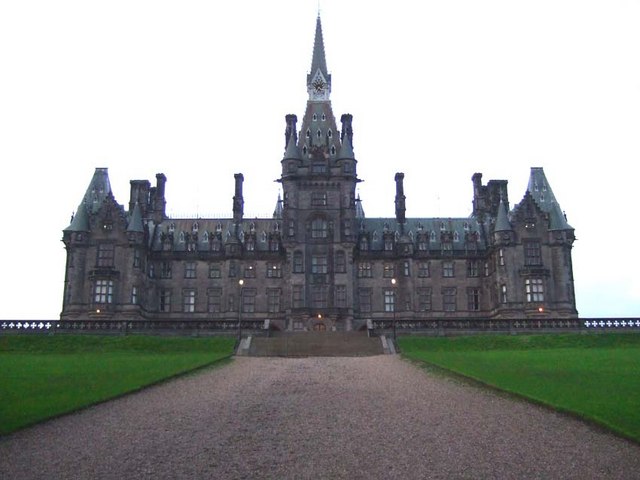

Following a one-year break during which he taught for one term at the prep school Swanbourne House, he was appointed headmaster of Fettes College

Fettes College () is a co-educational independent boarding and day school in Edinburgh, Scotland, with over two-thirds of its pupils in residence on campus. The school was originally a boarding school for boys only and became co-ed in 1983. In ...

, where he succeeded in greatly increasing enrolment and in reforming the harsh traditional atmosphere of the school. He died while still headmaster there.

He is the subject of child sexual abuse allegations detailed in numerous articles and an episode of the BBC radio documentary series ''In Dark Corners'' by Alex Renton.

Family and early years

He was born into, on his father's side, a family ofAnglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

descent in British Raj India. He was the son of Charles Godfrey Chenevix Trench (1877–1964) and Margaret May Blakesley. His father was in the Indian Civil Service

The Indian Civil Service (ICS), officially known as the Imperial Civil Service, was the higher civil service of the British Empire in India during British rule in the period between 1858 and 1947.

Its members ruled over more than 300 million ...

. His great-grandfather was The Most Rev.

The Most Reverend is a style applied to certain religious figures, primarily within the historic denominations of Christianity, but occasionally in some more modern traditions also. It is a variant of the more common style "The Reverend".

Anglic ...

Dr Richard Chenevix Trench

Richard Chenevix Trench (Richard Trench until 1873; 9 September 1807 – 28 March 1886) was an Anglican archbishop and poet.

Life

He was born in Dublin, Ireland, the son of Richard Trench (1774–1860), barrister-at-law, and the Dublin write ...

(1807–1886), Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the second ...

Lord Archbishop of Dublin, a senior-ranking Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

cleric, and his cousin Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*k ...

was a British Indian Army

The British Indian Army, commonly referred to as the Indian Army, was the main military of the British Raj before its dissolution in 1947. It was responsible for the defence of the British Indian Empire, including the princely states, which co ...

officer, colonial official and writer.

Anthony Chenevix-Trench, born at Kasauli

Kasauli is a town and cantonment, located in Solan district in the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh. The cantonment was established by the British Raj in 1842 as a Colonial hill station,Sharma, Ambika"Architecture of Kasauli churches" ''The Trib ...

in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

on 10 May 1919, was the youngest of four sons born to the couple, the older ones being Christopher, Richard and Godfrey. In the first few years of his life the family visited Britain and other countries, returning to India in 1922 where his father worked as part of a three-man commission in the picturesque city of Udaipur

Udaipur () (ISO 15919: ''Udayapura''), historically named as Udayapura, is a city and municipal corporation in Udaipur district of the state of Rajasthan, India. It is the administrative headquarter of Udaipur district. It is the historic capit ...

making recommendations on the vexed issue of land reform in the Rajput

Rajput (from Sanskrit ''raja-putra'' 'son of a king') is a large multi-component cluster of castes, kin bodies, and local groups, sharing social status and ideology of genealogical descent originating from the Indian subcontinent. The term Ra ...

state of Mewar

Mewar or Mewad is a region in the south-central part of Rajasthan state of India. It includes the present-day districts of Bhilwara, Chittorgarh, Pratapgarh, Rajsamand, Udaipur, Pirawa Tehsil of Jhalawar District of Rajasthan, Neemuch and Man ...

. Anthony was to spend three years in India, living in traditional colonial luxury with a staff of twelve including an English nanny

A nanny is a person who provides child care. Typically, this care is given within the children's family setting. Throughout history, nannies were usually servants in large households and reported directly to the lady of the house. Today, modern ...

and an Indian ayah, riding with the Mewar state cavalry on his pony while wearing a lancer

A lancer was a type of cavalryman who fought with a lance. Lances were used for mounted warfare in Assyria as early as and subsequently by Persia, India, Egypt, China, Greece, and Rome. The weapon was widely used throughout Eurasia during the M ...

's uniform tailored down to his size, and moving to the foothills of the Himalayas

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over 100 ...

to avoid the heat of the summer.

Education

The family returned to England in 1925, moving to Somerset in 1927; Chenevix-Trench attended school for the first time inWestgate-on-Sea

Westgate-on-Sea is a seaside town and civil parish on the north-east coast of Kent, England. It is within the Thanet local government district and borders the larger seaside resort of Margate. Its two sandy beaches have remained a popular touri ...

in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

. He had already been introduced to classical literature by his father, reading Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known f ...

at the age of six. His mother Margaret would always read to the children – who by now included all four brothers and Philippa Tooth whom the Chenevix-Trenches looked after while her parents remained in India – at bedtime, including G. K. Chesterton, Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)''The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English novelist, short-story writer, poet, and journalist. He was born in British Raj, British India, which inspired much o ...

, and Greek and Roman myths. Towards the end of his life Chenevix-Trench described how this had inspired him, and said that "the words still sing in my mind like music".

At age eight he was sent to board

Board or Boards may refer to:

Flat surface

* Lumber, or other rigid material, milled or sawn flat

** Plank (wood)

** Cutting board

** Sounding board, of a musical instrument

* Cardboard (paper product)

* Paperboard

* Fiberboard

** Hardboard, a ty ...

at the prep school Highfield in Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English citi ...

, where the headmaster Canon W.R. Mills was described as "a hard taskmaster in Latin". Chenevix-Trench was a contemporary there of Ludovic Kennedy

Sir Ludovic Henry Coverley Kennedy (3 November 191918 October 2009) was a Scottish journalist, broadcaster, humanist and author best known for re-examining cases such as the Lindbergh kidnapping and the murder convictions of Timothy Evans and ...

, whom he helped with Greek prose composition, Anthony Storr

Anthony Storr (18 May 1920 – 17 March 2001) was an English psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, and author.

Background and education

Born in London, Storr was educated at Winchester College, Christ's College, Cambridge, and Westminster Hospital. H ...

and Robin Maugham

Robert Cecil Romer Maugham, 2nd Viscount Maugham (17 May 1916 – 13 March 1981), known as Robin Maugham, was a British author.

Trained as a barrister, he served with distinction in the Second World War, and wrote a successful novella, ''The S ...

; all three of these were later scathing of the headmaster's extensive use of the cane on his young charges. In his early years there, Chenevix-Trench spent more than a year away from the school due to lung congestion, suspected rheumatic fever

Rheumatic fever (RF) is an inflammatory disease that can involve the heart, joints, skin, and brain. The disease typically develops two to four weeks after a streptococcal throat infection. Signs and symptoms include fever, multiple painful jo ...

, and problems with sleepwalking

Sleepwalking, also known as somnambulism or noctambulism, is a phenomenon of combined sleep and wakefulness. It is classified as a sleep disorder belonging to the parasomnia family. It occurs during slow wave stage of sleep, in a state of low ...

. But he quickly resumed progress, writing prose and poetry described as "highly polished" for the school magazine, and being successful at boxing

Boxing (also known as "Western boxing" or "pugilism") is a combat sport in which two people, usually wearing protective gloves and other protective equipment such as hand wraps and mouthguards, throw punches at each other for a predetermined ...

, though he was too small to excel at most of the team sports. He was popular through sheer enthusiasm rather than physical prowess, and in his penultimate year founded an unofficial school club in which boys would crawl about in the school's lofts

A loft is a building's upper storey or elevated area in a room directly under the roof (American usage), or just an attic: a storage space under the roof usually accessed by a ladder (primarily British usage). A loft apartment refers to large ...

in their pyjamas

Pajamas ( US) or pyjamas (Commonwealth) (), sometimes colloquially shortened to PJs, jammies, jam-jams, or in South Asia night suits, are several related types of clothing worn as nightwear or while lounging or performing remote work from hom ...

– the subsequent myth was that he fell through the headmaster's own ceiling and was thoroughly caned on the spot. Despite all this, Chenevix-Trench won a scholarship to Shrewsbury School

Shrewsbury School is a public school (English independent boarding school for pupils aged 13 –18) in Shrewsbury.

Founded in 1552 by Edward VI by Royal Charter, it was originally a boarding school for boys; girls have been admitted into the ...

while still aged twelve, and was a prefect

Prefect (from the Latin ''praefectus'', substantive adjectival form of ''praeficere'': "put in front", meaning in charge) is a magisterial title of varying definition, but essentially refers to the leader of an administrative area.

A prefect's ...

in his last term at Highfield.

At Shrewsbury at the time, H.H. Hardy was headmaster, described as a "strict disciplinarian" who maintained the school's "rich Classical tradition, sporting fanaticism, fervent house

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air condi ...

loyalties, robust discipline and unseemly squalor". Chenevix-Trench was small for his age, but charmed both teachers and other pupils with his wit and enthusiasm, took part in a wide variety of sports, and continued to excel academically, winning a host of prizes. He became a house monitor at age sixteen, and head of School House the following year. Francis King

Francis Henry King (4 March 19233 July 2011) Ion Trewin and Jonathan Fryer"Obituary: Francis King" ''The Guardian'', 3 July 2011. was a British novelist and short story writer. He worked for the British Council for 15 years, with positions i ...

, who was a thirteen-year-old in his first year at the school at the time, described Chenevix-Trench as "a supercilious, capricious and cruel head of house". The majority did not share this view, and Robin Lorimer, Chenevix-Trench's best friend at Shrewsbury, observed that Chenevix-Trench was merely upholding a rule then in force that even the most trivial mistakes by younger boys must be punished with four strokes of the cane by the monitors, but did not gloat over the effects. By this time Chenevix-Trench had already gained a Classics Scholarship to Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church ( la, Ædes Christi, the temple or house, '' ædēs'', of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, the college is uniqu ...

, at age sixteen.

He was housed in

He was housed in Peckwater Quad

The Peckwater Quadrangle (known as "Peck" to students) is one of the Quadrangle (architecture), quadrangles of Christ Church, Oxford, Christ Church, Oxford, England. It is a Grade I listed building.

Christ Church Library is on the south side of ...

, and rowed in the college's Second VIII. He greatly appreciated his surroundings, writing home that "Oxford in sunshine is a dream city – made to be seen in summer". He was elected to the Twenty Club, an exclusive Christ Church debating society, but he did not join the Oxford Union

The Oxford Union Society, commonly referred to simply as the Oxford Union, is a debating society in the city of Oxford England, whose membership is drawn primarily from the University of Oxford. Founded in 1823, it is one of Britain's oldest ...

or the Oxford University Dramatic Society

The Oxford University Dramatic Society (OUDS) is the principal funding body and provider of theatrical services to the many independent student productions put on by students in Oxford, England. Not all student productions at Oxford University a ...

, for reasons of cost and time commitments respectively. His tutors for Honour Moderations

Honour Moderations (or ''Mods'') are a set of examinations at the University of Oxford at the end of the first part of some degree courses (e.g., Greats or '' Literae Humaniores'').

Honour Moderations candidates have a class awarded (hence the ' ...

were Denys Page

Sir Denys Lionel Page (11 May 19086 July 1978) was a British classicist and textual critic who served as the 34th Regius Professor of Greek at the University of Cambridge and the 35th Master of Jesus College, Cambridge. He is best known for h ...

and John G. Barrington-Ward, said to be "one of the best Latin prose scholars in Oxford", who was also a crossword setter for ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

''. Chenevix-Trench twice narrowly failed to win the coveted Hertford Prize for classicists, but in Mods he achieved twelve alpha grades out of fourteen papers, resulting in an easy First-class in Latin and Greek literature. Before his third year at Oxford began, the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

broke out, and Chenevix-Trench signed up for the Royal Regiment of Artillery

The Royal Regiment of Artillery, commonly referred to as the Royal Artillery (RA) and colloquially known as "The Gunners", is one of two regiments that make up the artillery arm of the British Army. The Royal Regiment of Artillery comprises t ...

(believing it likely to be more cerebral than an infantry command)—his oath was witnessed by Hugh Trevor-Roper

Hugh Redwald Trevor-Roper, Baron Dacre of Glanton (15 January 1914 – 26 January 2003) was an English historian. He was Regius Professor of Modern History at the University of Oxford.

Trevor-Roper was a polemicist and essayist on a range of ...

.

Military service

Chenevix-Trench started his military career as an officer cadet at Aldershot, taking the technical and organisational teaching seriously but the remainder less so: "In these pre-

Chenevix-Trench started his military career as an officer cadet at Aldershot, taking the technical and organisational teaching seriously but the remainder less so: "In these pre-Dunkirk

Dunkirk (french: Dunkerque ; vls, label=French Flemish, Duunkerke; nl, Duinkerke(n) ; , ;) is a commune in the department of Nord in northern France.second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

. When volunteers were requested to be replacement officers for artillery units in India, he stepped forward, remembering his happy childhood days there. In Bombay, he joined the 22nd Mountain (Indian Artillery) Regiment, and took charge of an artillery battery. His linguistic skills were immensely valuable in overcoming poor communications within the unit (he mastered the basics of Urdu

Urdu (;"Urdu"

'' The regiment, made up of four batteries, was stationed in Singapore, the most important British naval base in the Far East. Each battery was made up of 180 men with four British officers; Chenevix-Trench's battery was the 24th (Hazara) Mountain Battery, which had recently been re-equipped with 6-inch howitzers. By the time Japan attacked Malaya in early December 1941, Chenevix-Trench had been promoted to battery

The regiment, made up of four batteries, was stationed in Singapore, the most important British naval base in the Far East. Each battery was made up of 180 men with four British officers; Chenevix-Trench's battery was the 24th (Hazara) Mountain Battery, which had recently been re-equipped with 6-inch howitzers. By the time Japan attacked Malaya in early December 1941, Chenevix-Trench had been promoted to battery  Chenevix-Trench was a

Chenevix-Trench was a  Despite it all, he kept up his classical studies, and gave talks to his fellow prisoners about Greek literature. He was also remembered as a man who took mortal risks to barter for the food that might keep men alive a few days longer. For his parents, almost all of 1942 passed without a word, before learning by an official telegram that he was a prisoner of war; they continued a constant stream of letters, most of which reached him and gave him great comfort, even though his postcards in the opposite direction were censored or injected with random text like "tell Susan not to worry". Susan was fictitious, but by 1944 she did indeed not need to worry about him; with the railway completed, he was back in Singapore, with enough leisure to learn both

Despite it all, he kept up his classical studies, and gave talks to his fellow prisoners about Greek literature. He was also remembered as a man who took mortal risks to barter for the food that might keep men alive a few days longer. For his parents, almost all of 1942 passed without a word, before learning by an official telegram that he was a prisoner of war; they continued a constant stream of letters, most of which reached him and gave him great comfort, even though his postcards in the opposite direction were censored or injected with random text like "tell Susan not to worry". Susan was fictitious, but by 1944 she did indeed not need to worry about him; with the railway completed, he was back in Singapore, with enough leisure to learn both

Chenevix-Trench also served as an officer in the school's

Chenevix-Trench also served as an officer in the school's

''

Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

and half Sikh

Sikhs ( or ; pa, ਸਿੱਖ, ' ) are people who adhere to Sikhism, Sikhism (Sikhi), a Monotheism, monotheistic religion that originated in the late 15th century in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent, based on the revelation of Gu ...

but with British officers and signallers, continued to cause problems.

The regiment, made up of four batteries, was stationed in Singapore, the most important British naval base in the Far East. Each battery was made up of 180 men with four British officers; Chenevix-Trench's battery was the 24th (Hazara) Mountain Battery, which had recently been re-equipped with 6-inch howitzers. By the time Japan attacked Malaya in early December 1941, Chenevix-Trench had been promoted to battery

The regiment, made up of four batteries, was stationed in Singapore, the most important British naval base in the Far East. Each battery was made up of 180 men with four British officers; Chenevix-Trench's battery was the 24th (Hazara) Mountain Battery, which had recently been re-equipped with 6-inch howitzers. By the time Japan attacked Malaya in early December 1941, Chenevix-Trench had been promoted to battery captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

, and the battery was hundreds of miles further north in Jitra

Jitra ( zh, 日得拉) is a town and a mukim in Kubang Pasu District, in northern Kedah, Malaysia. It is the fourth-largest town in Kedah after Alor Setar, Sungai Petani and Kulim.

History

During World War II, when the Japanese attacked Mala ...

near the Malayan border with Siam

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 mi ...

, supporting the 11th Indian Division

The 11th Indian Division was an infantry Division (military), division of the British Indian Army during World War I. It was formed in December 1914 with two infantry brigades already in Egypt and a third formed in January 1915. After taking p ...

in defence of the Alor Star

Alor Setar ( Jawi: الور ستار, Kedahan: ''Loqstaq'') is the state capital of Kedah, Malaysia. It is the second-largest city in the state after Sungai Petani and one of the most-important cities on the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia ...

airfield. They were soon forced to withdraw in the face of the Japanese offensive, and then became part of the general retreat southwards through Malaya as the British forces risked being outflanked by Japanese amphibious landings. Massive Japanese air superiority

Aerial supremacy (also air superiority) is the degree to which a side in a conflict holds control of air power over opposing forces. There are levels of control of the air in aerial warfare. Control of the air is the aerial equivalent of c ...

put an end to the British naval counter-strike by sinking the battleship HMS ''Prince of Wales'' and the battlecruiser HMS ''Repulse'', which had been sent to attack the Japanese transport ships.

The battery commander, Edward Sawyer, described Chenevix-Trench as having been "a tower of strength" in the rearguard action. By 26 December, the unit was fighting at Kampar, halfway back to Singapore. Chenevix-Trench was further praised for his battery's role in defeating the first Japanese amphibious landings at Kuala Selangor

Kuala Selangor is a town in northwestern Selangor, Malaysia. It is the largest town and administrative centre of the coterminous Kuala Selangor District.

Etymology

The name ''Kuala Selangor'' means Estuary of the Selangor River.

History

...

, but the retreat continued, and by the end of January 1942 the regiment was back in Singapore, supporting the 28th Indian Infantry Brigade

The 28th Indian Infantry Brigade was an infantry brigade formation of the Indian Army during World War II. The brigade was formed in March 1941, at Secunderabad in India and assigned to the 6th Indian Infantry Division. In September 1941, the bri ...

in its defence of a sector of the island's shore west of the causeway linking it to the mainland. The 85,000 British and Commonwealth troops in Singapore surrendered on 15 February. One of the Sikh artillerymen in Chenevix-Trench's unit was not much impressed by the physical appearance of the Japanese, asking, "Sahib

Sahib or Saheb (; ) is an Arabic title meaning 'companion'. It was historically used for the first caliph Abu Bakr in the Quran. The title is still applied to the caliph by Sunni Muslims.

As a loanword, ''Sahib'' has passed into several langua ...

, how came we to be beaten by those bastards?"

Chenevix-Trench was a

Chenevix-Trench was a prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of wa ...

(POW) for three and a half years, first at Changi Prison

Changi Prison Complex, often known simply as Changi Prison, is a prison in Changi in the eastern part of Singapore.

History First prison

Before Changi Prison was constructed, the only penal facility in Singapore was at Pearl's Hill, beside t ...

and then working on the Burma Railway

The Burma Railway, also known as the Siam–Burma Railway, Thai–Burma Railway and similar names, or as the Death Railway, is a railway between Ban Pong, Thailand and Thanbyuzayat, Burma (now called Myanmar). It was built from 1940 to 1943 ...

, where he lost an eye and suffered kidney failure. The twenty-four British officers and signallers were separated from their Indian troops – whom the Japanese had hopes of subverting to their cause – and initially lived in fairly tolerable conditions. Chenevix-Trench learned more about India's ethnic and political divisions, read Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

's ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major Ancient Greek literature, ancient Greek Epic poetry, epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by moder ...

'' in Greek and Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemolo ...

's ''Critique of Pure Reason'', and compiled, bound and decorated an anthology of English poetry. Conditions changed in April 1943 when the POWs were used as slave labour on the railway. The track had to be forced through impenetrable jungle, in appalling conditions and with malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

, dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

and beriberi

Thiamine deficiency is a medical condition of low levels of thiamine (Vitamin B1). A severe and chronic form is known as beriberi. The two main types in adults are wet beriberi and dry beriberi. Wet beriberi affects the cardiovascular system, r ...

constant: Chenevix-Trench suffered all three. Medical supplies were non-existent, rations at starvation level, and the sick forced to work until they died. Chenevix-Trench saved many lives through inspired pseudo-medical advice and hygiene discipline. He saw one of his fellow soldiers impaled against a tree with bayonets for attempting to escape, amidst many other horrors. When a cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

epidemic struck, the British did not have enough fuel to build funeral pyres for the victims, so were forced to bury them in shallow graves. Heavy rains came and washed away the soil from over the graves, and one morning Chenevix-Trench and his fellow prisoners emerged from their camp amidst rows of protruding bones clad with rotting flesh.

Despite it all, he kept up his classical studies, and gave talks to his fellow prisoners about Greek literature. He was also remembered as a man who took mortal risks to barter for the food that might keep men alive a few days longer. For his parents, almost all of 1942 passed without a word, before learning by an official telegram that he was a prisoner of war; they continued a constant stream of letters, most of which reached him and gave him great comfort, even though his postcards in the opposite direction were censored or injected with random text like "tell Susan not to worry". Susan was fictitious, but by 1944 she did indeed not need to worry about him; with the railway completed, he was back in Singapore, with enough leisure to learn both

Despite it all, he kept up his classical studies, and gave talks to his fellow prisoners about Greek literature. He was also remembered as a man who took mortal risks to barter for the food that might keep men alive a few days longer. For his parents, almost all of 1942 passed without a word, before learning by an official telegram that he was a prisoner of war; they continued a constant stream of letters, most of which reached him and gave him great comfort, even though his postcards in the opposite direction were censored or injected with random text like "tell Susan not to worry". Susan was fictitious, but by 1944 she did indeed not need to worry about him; with the railway completed, he was back in Singapore, with enough leisure to learn both Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

and Mandarin

Mandarin or The Mandarin may refer to:

Language

* Mandarin Chinese, branch of Chinese originally spoken in northern parts of the country

** Standard Chinese or Modern Standard Mandarin, the official language of China

** Taiwanese Mandarin, Stand ...

, as well as "cooking, gardening, bridge and poker". Thus, with the added inconvenience of starvation rations once again, he lived out the rest of his war.

Chenevix-Trench described how the population of Singapore was "crazy with joy and showed it" when British troops arrived to take back control of the city after the Japanese surrender. His brother Godfrey was serving as navigating officer on HMS ''Cleopatra'', the first ship into Singapore, and the two were reunited the same day. Chenevix-Trench was also reunited with his Indian troops, and took the unusual decision that "after all my men have been through and their magnificent behaviour under shootings, beatings, and starving by enemy propagandists, I feel the least I can do to thank them is to see them all happily home to their villages". He therefore returned to England via India, only reaching home on 29 October 1945.

Return to Oxford

Chenevix-Trench returned to Oxford in 1946 to complete his degree. He was elected President of the Christ ChurchJunior Common Room

A common room is a group into which students and the academic body are organised in some universities in the United Kingdom and Ireland—particularly collegiate universities such as Oxford and Cambridge, as well as the University of Bristol ...

towards the end of that year, was involved in reviving the college's Boat Club, and was "the life and soul of the gathering" at many social functions. He was taught by R. H. Dundas, Eric Gray, Gilbert Ryle

Gilbert Ryle (19 August 1900 – 6 October 1976) was a British philosopher, principally known for his critique of Cartesian dualism, for which he coined the phrase "ghost in the machine." He was a representative of the generation of British ord ...

, Jim Urmson and Maurice Foster. He won the prestigious Slade Exhibition in 1947, and then achieved the remarkable feat of gaining an alpha in every single paper in Greats. In his final year, he had done some classics teaching back at Shrewsbury School when several classics teachers fell ill, and his enjoyment of it decided him on teaching as a career, with plans to become a headmaster one day. With offers to teach at Christ Church, Eton and Shrewsbury, he eventually chose Shrewsbury, and began teaching classics there in January 1948.

Teaching career

Shrewsbury and Oxford

At Shrewsbury Chenevix-Trench's philosophy was that he preferred that "the majority of boys kept the rules most of the time rather than one which stifled individual vitality". His lessons with the younger years also had a system of punishments and bribes: excellent work might receive ashilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence o ...

or half crown reward at his own expense, while a major mistake in written work would be marked by a picture of a crab – more than three crab images would result in the boy receiving corporal punishment in the privacy of Chenevix-Trench's study. With the older years he introduced textual criticism

Textual criticism is a branch of textual scholarship, philology, and of literary criticism that is concerned with the identification of textual variants, or different versions, of either manuscripts or of printed books. Such texts may range in ...

, philosophy and history to give greater insight into the classical texts than conventional teaching of the time allowed. He would also regularly tutor older boys individually – with alcoholic refreshments on hand – and occasionally permitted his proximity in age to encourage excess humour, as when he let slip to some of the sixth form

In the education systems of England, Northern Ireland, Wales, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago and some other Commonwealth countries, sixth form represents the final two years of secondary education, ages 16 to 18. Pupils typically prepare for A-l ...

that a visiting speaker, Reverend Hoskyns-Abrahall, had been known to Chenevix-Trench in his own schooldays as "Foreskin-rubberballs".

Combined Cadet Force

The Combined Cadet Force (CCF) is a youth organisation in the United Kingdom, sponsored by the Ministry of Defence (MOD), which operates in schools, and normally includes Army, Royal Navy and Royal Air Force sections. Its aim is to "provide a ...

, as a coach for rowing crews, and as an organiser of "holiday camps for underprivileged children in Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , also ) is a market town, civil parish, and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, north-west of London; at the 2021 census, it had a population of 76,782. The town's name can be pronounced as either 'Sh ...

". On school ski

A ski is a narrow strip of semi-rigid material worn underfoot to glide over snow. Substantially longer than wide and characteristically employed in pairs, skis are attached to ski boots with ski bindings, with either a free, lockable, or partial ...

trips to Switzerland he would make up for his lack of skill at the sport by instigating "ferocious snowball fight

A snowball fight is a physical game in which balls of snow are thrown with the intention of hitting somebody else. The game is similar to dodgeball in its major factors, though typically less organized. This activity is primarily played during ...

s", and abusing his linguistic skills in talking to other skiers, "talking a kind of German to the French, which they then disliked, French to the Americans, which they didn't understand, and Urdu

Urdu (;"Urdu"

''

''

George Turner, the headmaster of

He relaxed some uniform rules, but maintained rules that he felt reinforced school spirit, such as boys being required to attend inter-school sports fixtures as spectators. As at Shrewsbury, he did not abolish fagging or the rights of older boys to

He relaxed some uniform rules, but maintained rules that he felt reinforced school spirit, such as boys being required to attend inter-school sports fixtures as spectators. As at Shrewsbury, he did not abolish fagging or the rights of older boys to

Chenevix-Trench himself told a friend "Eton's too big for me, I'm not the right man. I like to be involved individually with boys." His older brother said he should not take the job. From the outset, Chenevix-Trench did not get along easily with Harold Caccia, who held the uniquely influential position of provost at the school, and was concerned by Chenevix-Trench's administrative failings. Not being an old Etonian himself, he also struggled to find the proper way to deal with the aristocratic rank of many of the parents, and even felt intellectually eclipsed by some of the teachers, in contrast to Bradfield. The housemasters at Eton also had vastly more power and independence than at Bradfield, and Chenevix-Trench's interference with how they dealt with boys from their own houses now caused anger rather than just annoyance, as did his continuing blunders in promising the same promotion to more than one person. He ended up describing the housemasters as like medieval barons with swords half-drawn, and never mastered the subtleties of dealing with them effectively.

Chenevix-Trench's time at Eton, in the midst of the 1960s, was further confused by the sense of change sweeping through the country. The ''

Chenevix-Trench himself told a friend "Eton's too big for me, I'm not the right man. I like to be involved individually with boys." His older brother said he should not take the job. From the outset, Chenevix-Trench did not get along easily with Harold Caccia, who held the uniquely influential position of provost at the school, and was concerned by Chenevix-Trench's administrative failings. Not being an old Etonian himself, he also struggled to find the proper way to deal with the aristocratic rank of many of the parents, and even felt intellectually eclipsed by some of the teachers, in contrast to Bradfield. The housemasters at Eton also had vastly more power and independence than at Bradfield, and Chenevix-Trench's interference with how they dealt with boys from their own houses now caused anger rather than just annoyance, as did his continuing blunders in promising the same promotion to more than one person. He ended up describing the housemasters as like medieval barons with swords half-drawn, and never mastered the subtleties of dealing with them effectively.

Chenevix-Trench's time at Eton, in the midst of the 1960s, was further confused by the sense of change sweeping through the country. The '' Despite being so obviously out of his depth, he made some minor and some major reforms. He ended the uniform requirement of smaller boys being marked out by having to wear the much shorter "bumfreezer" Eton Suit, but this was a tiny consolation for the crushing of his cherished goal of ending school uniform at Eton altogether. His reforms of the academic curriculum were colossal, moving Eton from being dominated by classics and catering almost exclusively for boys who had been privately and expensively educated in that field, to a vastly broader curriculum including the establishment of an English department for the first time, as well as introducing proper science teaching. In typical Chenevix-Trench style, these changes were achieved through a lengthy process of vacillation, U-turns, and another half-lie to the provost – massive expenditure was required to fund the new teachers, and even the Classics Department suffering worse than decimation (which contributed to the opposition to Chenevix-Trench) did not make up for it financially. But the consequence was that the school achieved a one-fifth increase in university awards, a "spectacular" increase in

Despite being so obviously out of his depth, he made some minor and some major reforms. He ended the uniform requirement of smaller boys being marked out by having to wear the much shorter "bumfreezer" Eton Suit, but this was a tiny consolation for the crushing of his cherished goal of ending school uniform at Eton altogether. His reforms of the academic curriculum were colossal, moving Eton from being dominated by classics and catering almost exclusively for boys who had been privately and expensively educated in that field, to a vastly broader curriculum including the establishment of an English department for the first time, as well as introducing proper science teaching. In typical Chenevix-Trench style, these changes were achieved through a lengthy process of vacillation, U-turns, and another half-lie to the provost – massive expenditure was required to fund the new teachers, and even the Classics Department suffering worse than decimation (which contributed to the opposition to Chenevix-Trench) did not make up for it financially. But the consequence was that the school achieved a one-fifth increase in university awards, a "spectacular" increase in

Other reforms he instituted at Fettes included the abolition of personal

Other reforms he instituted at Fettes included the abolition of personal

Charterhouse

Charterhouse may refer to:

* Charterhouse (monastery), of the Carthusian religious order

Charterhouse may also refer to:

Places

* The Charterhouse, Coventry, a former monastery

* Charterhouse School, an English public school in Surrey

London ...

, who was about to retire, wrote to Chenevix-Trench insisting he apply for the job, and Geoffrey Fisher

Geoffrey Francis Fisher, Baron Fisher of Lambeth, (5 May 1887 – 15 September 1972) was an English Anglican priest, and 99th Archbishop of Canterbury, serving from 1945 to 1961.

From a long line of parish priests, Fisher was educated at Marlb ...

, Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

and chairman of the Charterhouse governors, visited him in person to urge him to do so. Soon considered the favourite, despite pressure from Christ Church not to leave, Chenevix-Trench caused chaos by first submitting his candidacy, then withdrawing it after Tom Taylor, housemaster of School House back at Shrewsbury, died suddenly in the post and he was offered the job. Loyalty to his old school and house won out over both the remarkable opportunity of being headmaster of a major public school at age 32 and his academic responsibility at Christ Church, and Chenevix-Trench accepted the promotion at Shrewsbury, despite great distress at the conflict of loyalties. From Christ Church, Roy Harrod

Sir Henry Roy Forbes Harrod (13 February 1900 – 8 March 1978) was an English economist. He is best known for writing ''The Life of John Maynard Keynes'' (1951) and for the development of the Harrod–Domar model, which he and Evsey Domar devel ...

wrote that "There is something about the way this has been done that shocks me. I have a terribly strong sense that it is wrong". At Shrewsbury there was delight at his taking the job, and a "pandaemonium of excited and happy chattering" among the boys of School House when they were told. Chenevix-Trench took up his new post in September.

In November 1952, Chenevix-Trench spoke with Michael Hoban in opposition to a motion at the school Debating Society, proposed by the old boys and then Oxford undergraduates Michael Heseltine

Michael Ray Dibdin Heseltine, Baron Heseltine, (; born 21 March 1933) is a British politician and businessman. Having begun his career as a property developer, he became one of the founders of the publishing house Haymarket. Heseltine served a ...

and Julian Critchley

Sir Julian Michael Gordon Critchley (8 December 1930 – 9 September 2000) was a British journalist, author and Conservative Party politician. He was the member of parliament for Rochester and Chatham from 1959 to 1964 and Aldershot from 1970 ...

, that "This House Deplores the Public School System". Both the proposers poked fun at Chenevix-Trench's proclivity towards corporal punishment, and he defended the practice by suggesting that the alternatives had their own problems. The motion was carried by 105 votes to 95, and the tabloid newspaper

A tabloid is a newspaper with a compact page size smaller than broadsheet. There is no standard size for this newspaper format.

Etymology

The word ''tabloid'' comes from the name given by the London-based pharmaceutical company Burroughs We ...

s made a great story from the outcome. Chenevix-Trench did not change his approach, nor did he object to the continuation of the tradition of fagging

Fagging was a traditional practice in British public schools and also at many other boarding schools, whereby younger pupils were required to act as personal servants to the eldest boys. Although probably originating earlier, the first account ...

, nor that of older boys having the right to use corporal punishment on younger boys. In addition to his added organisational responsibilities as housemaster, he also continued both his close academic tutoring and carefree informality with the boys of School House. On 15 August 1953, he married Elizabeth Spicer, a primary school teacher whose brother he had known at Oxford. She took over some of the organisational work in School House, resulting in reports from the boys of great improvements in the quality of the food. Elizabeth gave birth to twin daughters, Laura and Jo, in October 1955. The couple's two sons, Richard and Jonathan, were born after he left Shrewsbury.

Bradfield College

In January 1955, Chenevix-Trench agreed to be interviewed for the position of headmaster atBradfield College

Bradfield College, formally St Andrew's College, Bradfield, is a public school (English independent day and boarding school) for pupils aged 11–18, located in the small village of Bradfield in the English county of Berkshire. It is note ...

, who were eager to find a younger replacement for John Hills, and were impressed by Chenevix-Trench's academic credentials. He got the job and left Shrewsbury with great regret. At Bradfield he continued his insistence on informality, regularly associating with the boys in their leisure time to relate his many anecdotes, and learning every boy's Christian name

A Christian name, sometimes referred to as a baptismal name, is a religious personal name given on the occasion of a Christian baptism, though now most often assigned by parents at birth. In English-speaking cultures, a person's Christian name ...

. He also abolished an ancient tradition whereby the entry of the headmaster to the most revered event (a play in ancient Greek performed once every three years) was heralded with a trumpet fanfare. He was successful in re-establishing close links with prep schools, which were vital for maintaining a flow of academically able boys to join the school and increase its numbers. He also charmed parents, of both existing and prospective pupils, lavishing great attention on them. As a disciplinarian he could be forgiving and open-minded: Richard Henriques

Sir Richard Henry Quixano Henriques (born 27 October 1943) is a British retired lawyer and judge who was a Justice of the High Court of England and Wales.

Early life and education

Henriques was born in south Fylde, educated at Southdene, in So ...

was sent to him by the school chaplain to be punished for asking a controversial question about religion, but Chenevix-Trench dismissed the problem.

He relaxed some uniform rules, but maintained rules that he felt reinforced school spirit, such as boys being required to attend inter-school sports fixtures as spectators. As at Shrewsbury, he did not abolish fagging or the rights of older boys to

He relaxed some uniform rules, but maintained rules that he felt reinforced school spirit, such as boys being required to attend inter-school sports fixtures as spectators. As at Shrewsbury, he did not abolish fagging or the rights of older boys to beat

Beat, beats or beating may refer to:

Common uses

* Patrol, or beat, a group of personnel assigned to monitor a specific area

** Beat (police), the territory that a police officer patrols

** Gay beat, an area frequented by gay men

* Battery (c ...

younger boys, but at Bradfield he reduced both. Even after his minor reforms, new boys were still caned by prefects for "talking after lights out", "misbehaviour in the dining hall", "insolence to a prefect", and similar transgressions. The prefects themselves sometimes fell victim to Chenevix-Trench's harsher rules, though: he expelled the Head of School (head boy) for smoking on school transport after an official sports fixture. Other aspects of his approach were more controversial, even for the times. Chenevix-Trench's biographer, Mark Peel, stated that "although Tony's efforts to rid the school of homosexuality by engaging in a massive beating spree were seen by many as discrimination towards the non-robust boys, only the minority appears to have been alienated". His mixture of corporal punishment with close friendship continued, with some recipients of the cane offered an alcoholic drink immediately afterwards.

In later years, Chenevix-Trench liked to tell how a pet mouse called Peter had a lucky escape when its diminutive owner, already bent over a chair in his study to be caned, suddenly realised that Peter – the cause of the impending punishment – was still in his back pocket, and politely asked Chenevix-Trench to hold the mouse until the caning was over. Finding the situation uproariously funny, he did not administer the punishment. He also threw himself into the task of fighting for his teaching staff, succeeding in increasing both pay and rights for housemasters, and recruited young graduates constantly to modernise the range of teachers. Despite his own enthusiasm for boxing, when one new recruit was put in charge of gym and expressed his opposition to the sport, key to the school at the time, Chenevix-Trench agreed with his arguments (which were backed by the school medical officer) and boxing was abolished in July 1963. Although he actively but respectfully involved himself in his housemasters' running of their houses, Bradfield also saw the first signs of real problems caused by his administrative or communicative carelessness: heads of departments could find new staff appointed under them without being informed, much less consulted; staff accommodation arrangements were sometimes random; and he found the important consideration of the school timetable

A schedule or a timetable, as a basic time-management tool, consists of a list of times at which possible task (project management), tasks, events, or actions are intended to take place, or of a sequence of events in the chronological order ...

arrangements to be completely outside his sense of priorities.

Chenevix-Trench continued to teach while headmaster, and boys described his lessons as exhilarating. That, along with his determination to encourage his staff to follow his example, succeeded in substantially raising academic standards at Bradfield from their already relatively high level. Other triumphs included his use of his excellent rapport with the School Council to persuade them to increase scholarships for gifted but less pecunious boys, increase the numbers of teachers to support a wider curriculum, and approve a new complex of science buildings in March 1956. This was followed in March 1960 by the launch of an appeal fund that ultimately paid for central heating, new kitchens, new study bedrooms for the boys (whose accommodation had been criticised in a March 1959 report Chenevix-Trench requested from the Ministry of Education

An education ministry is a national or subnational government agency politically responsible for education. Various other names are commonly used to identify such agencies, such as Ministry of Education, Department of Education, and Ministry of Pub ...

), and a music hall and language laboratory. Exam results soared, as did the number of boys gaining university places.

Chenevix-Trench's public profile saw a corresponding rise; in 1958 he appeared on the BBC television programme ''The Brains Trust

''The Brains Trust'' was an informational BBC radio and later television programme popular in the United Kingdom during the 1940s and 1950s, on which a panel of experts tried to answer questions sent in by the audience.

History

The series was ...

'' as a panellist, broadcast on television during the peak time Sunday afternoon slot and then rebroadcast on Home Service

Home Service is a British folk rock group, formed in late 1980 from a nucleus of musicians who had been playing in Ashley Hutchings' Albion Band. Their career is generally agreed to have peaked with the album ''Alright Jack'', and has had an ...

radio the following day. Anthony Sampson

Anthony Terrell Seward Sampson (3 August 1926 – 18 December 2004) was a British writer and journalist. His most notable and successful book was '' Anatomy of Britain'', which was published in 1962 and was followed by five more "Anatomies", upd ...

, describing the headmasters of leading public schools in the original edition of the ''Anatomy of Britain

''Anatomy of Britain'' was a book written by Anthony Sampson and published by Hodder & Stoughton in 1962. The book is an examination of the ruling classes of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commo ...

'' in 1962, called Chenevix-Trench a "heroic and unusual man". He was the only headmaster appointed to the Committee on Higher Education which produced the Robbins Report

The Robbins Report (the report of the Committee on Higher Education, chaired by Lord Robbins) was commissioned by the British government and published in 1963. The committee met from 1961 to 1963. After the report's publication, its conclusions wer ...

that led to significant British university expansion in the decade and later. He signed the Marlow Declaration on society and equality, and declined headmasterships at a host of top schools including Shrewsbury. On 4 March 1963, the BBC announced that he would be the new headmaster of Eton.

Eton College

Chenevix-Trench himself told a friend "Eton's too big for me, I'm not the right man. I like to be involved individually with boys." His older brother said he should not take the job. From the outset, Chenevix-Trench did not get along easily with Harold Caccia, who held the uniquely influential position of provost at the school, and was concerned by Chenevix-Trench's administrative failings. Not being an old Etonian himself, he also struggled to find the proper way to deal with the aristocratic rank of many of the parents, and even felt intellectually eclipsed by some of the teachers, in contrast to Bradfield. The housemasters at Eton also had vastly more power and independence than at Bradfield, and Chenevix-Trench's interference with how they dealt with boys from their own houses now caused anger rather than just annoyance, as did his continuing blunders in promising the same promotion to more than one person. He ended up describing the housemasters as like medieval barons with swords half-drawn, and never mastered the subtleties of dealing with them effectively.

Chenevix-Trench's time at Eton, in the midst of the 1960s, was further confused by the sense of change sweeping through the country. The ''

Chenevix-Trench himself told a friend "Eton's too big for me, I'm not the right man. I like to be involved individually with boys." His older brother said he should not take the job. From the outset, Chenevix-Trench did not get along easily with Harold Caccia, who held the uniquely influential position of provost at the school, and was concerned by Chenevix-Trench's administrative failings. Not being an old Etonian himself, he also struggled to find the proper way to deal with the aristocratic rank of many of the parents, and even felt intellectually eclipsed by some of the teachers, in contrast to Bradfield. The housemasters at Eton also had vastly more power and independence than at Bradfield, and Chenevix-Trench's interference with how they dealt with boys from their own houses now caused anger rather than just annoyance, as did his continuing blunders in promising the same promotion to more than one person. He ended up describing the housemasters as like medieval barons with swords half-drawn, and never mastered the subtleties of dealing with them effectively.

Chenevix-Trench's time at Eton, in the midst of the 1960s, was further confused by the sense of change sweeping through the country. The ''Daily Express

The ''Daily Express'' is a national daily United Kingdom middle-market newspaper printed in tabloid format. Published in London, it is the flagship of Express Newspapers, owned by publisher Reach plc. It was first published as a broadsheet i ...

'' said that Eton "may well have elected a man who will help to effect a quiet, but most necessary revolution" at the school. The ''Eton Chronicle'', authored mostly by pupils, was more blunt about the expected upheavals of the times, writing about the new headmaster: "The whole problem of privilege, and the question of integration with the state system of education will inevitably become a political issue arousing vehemence and bigotry". In the final term of 1965, Chenevix-Trench was interviewed in the same publication, and publicly expressed a preference for entry solely by competitive examination rather than by birth and background, and the same year he was still assuring pupils that school uniform was to be abolished entirely. The ''Chronicle'' was again a factor in the debate over abolishing boxing; David Jessel

David Greenhalgh Jessel (born 8 November 1945) is a former British TV and radio news presenter, author, and campaigner against miscarriages of justice. From 2000 to 2010, he was also a commissioner of the Criminal Cases Review Commission.

Backgro ...

and William Waldegrave wrote a piece against it in February 1964, and the ''Daily Express'' featured it on its front page. Not all these demands seemed important or realistic to following generations, who also wondered how significant it was whether "to listen to high thoughts and to be at peace in school for ten minutes every day", in chapel, should be optional or not. The BBC reported in 1967 that Chenevix-Trench had "considerably softened" the rigorous rules on chapel attendance. Nevertheless, ''Private Eye

''Private Eye'' is a British fortnightly satire, satirical and current affairs (news format), current affairs news magazine, founded in 1961. It is published in London and has been edited by Ian Hislop since 1986. The publication is widely r ...

'' duly ran an article in 1969 (by Paul Foot) arguing that Chenevix-Trench had clearly lost his way, since neither school uniform, nor boxing, nor compulsory Chapel, had been entirely abolished.

The ''Private Eye'' article also reported on Chenevix-Trench's approach to corporal punishment. It had always been traditional and frequent at Eton. Until he became headmaster, disobedient students could be publicly birched by the headmaster or Lower Master (deputy head) on their bare buttocks as punishment for serious offences. In addition, senior students at the school were permitted to cane

Cane or caning may refer to:

*Walking stick or walking cane, a device used primarily to aid walking

*Assistive cane, a walking stick used as a mobility aid for better balance

*White cane, a mobility or safety device used by many people who are b ...

other boys across the seat of the trousers, and this was routine. The Council at Bradfield, always hugely supportive of Chenevix-Trench, had never considered his use of corporal punishment a problem. But at Eton, the modern era of adolescent challenges to authority, combined with the existing tradition of powerful housemasters expecting to make their own decisions, quickly led to problems. In June 1965, Chenevix-Trench failed to prevent a debate proposed by William Waldegrave, then president of the powerful self-selected pupil society known as Pop, on the abolition of corporal punishment, and the motion was only narrowly defeated. Chenevix-Trench caned sixth-formers for trivial offences against the urgings of the Captain of the School (head boy); he caned one editor of the ''Eton Chronicle'' and backed down after threatening to cane another; and on a later occasion he agreed with the Captain of the School and his housemaster to punish an offender in a formally witnessed ceremony, but then gave a private caning instead without discussing it with them. The long history at Eton of birchings being public, and most canings being widely witnessed, meant that Chenevix-Trench's preference for private beatings was viewed with suspicion. In 1966, the Provost made him promise that he would no longer issue beatings in private. He did not keep the promise, thus storing up yet more distrust. To replace headmaster's birching, he introduced private caning, also administered to the bare posterior of the boy, who was required to lower his trousers and underpants and bend over in his office. A few boys resented this and felt that a caning over the trousers, as was standard practice at nearly all other schools by this time, would have sufficed.

Despite being so obviously out of his depth, he made some minor and some major reforms. He ended the uniform requirement of smaller boys being marked out by having to wear the much shorter "bumfreezer" Eton Suit, but this was a tiny consolation for the crushing of his cherished goal of ending school uniform at Eton altogether. His reforms of the academic curriculum were colossal, moving Eton from being dominated by classics and catering almost exclusively for boys who had been privately and expensively educated in that field, to a vastly broader curriculum including the establishment of an English department for the first time, as well as introducing proper science teaching. In typical Chenevix-Trench style, these changes were achieved through a lengthy process of vacillation, U-turns, and another half-lie to the provost – massive expenditure was required to fund the new teachers, and even the Classics Department suffering worse than decimation (which contributed to the opposition to Chenevix-Trench) did not make up for it financially. But the consequence was that the school achieved a one-fifth increase in university awards, a "spectacular" increase in

Despite being so obviously out of his depth, he made some minor and some major reforms. He ended the uniform requirement of smaller boys being marked out by having to wear the much shorter "bumfreezer" Eton Suit, but this was a tiny consolation for the crushing of his cherished goal of ending school uniform at Eton altogether. His reforms of the academic curriculum were colossal, moving Eton from being dominated by classics and catering almost exclusively for boys who had been privately and expensively educated in that field, to a vastly broader curriculum including the establishment of an English department for the first time, as well as introducing proper science teaching. In typical Chenevix-Trench style, these changes were achieved through a lengthy process of vacillation, U-turns, and another half-lie to the provost – massive expenditure was required to fund the new teachers, and even the Classics Department suffering worse than decimation (which contributed to the opposition to Chenevix-Trench) did not make up for it financially. But the consequence was that the school achieved a one-fifth increase in university awards, a "spectacular" increase in O-level

The O-Level (Ordinary Level) is a subject-based qualification conferred as part of the General Certificate of Education. It was introduced in place of the School Certificate in 1951 as part of an educational reform alongside the more in-depth ...

and A-level

The A-Level (Advanced Level) is a subject-based qualification conferred as part of the General Certificate of Education, as well as a school leaving qualification offered by the educational bodies in the United Kingdom and the educational aut ...

grades, and improved university entrance results.

The tumult of the era continued to faze Chenevix-Trench's tenuous hold on Eton; he adopted a drugs policy that saw him trudging up and down the High Street looking for offenders, and at the same time he declined to expel those caught indulging. With his antipathy toward school uniform, the fashions of longer hair and particular styles of boots did not bother him at all; some of Eton's housemasters were appalled by this lack of diligence. Boys who ran away were rewarded with long talks with the headmaster seeking to find the cause of their problems; traditionalists did not approve, wanting them beaten or expelled or both. Chenevix-Trench had always been shocked by the proportion of boys then at Eton who had absolutely no interest in doing any work, and of whom some had the determination to continue to refuse even when threatened. If he had mastered his relations with housemasters, and understood how to run the school by delegation as it had always been run, this would have been no problem; but for a headmaster that already struggled even with the basics, it was too much.

Chenevix-Trench's health, both physical and mental, also began to suffer, with the return of the malaria he had caught during the war, and flashbacks and nightmares of his wartime experiences. He took tranquilizers to help him with his worsening nerves when carrying out public speaking engagements, and resorted to heavy drinking to drown his other sorrows. The final straw came after a dispute over the future of one of the housemasters, Michael Neal. Neal was a popular and effective teacher but failed to keep proper control over his house. After a major incident in summer 1968, Chenevix-Trench declined to dismiss him, instead offering to resign himself. The offer was rejected, but Neal's house continued to be problematic, and Chenevix-Trench eventually had to fire him on the pretext of a much less serious incident several months later. He handled it badly, leading to protests by the boys, and this combined with a growing awareness of the other problems led the Fellows to decide to ask him to leave. This was dealt with sensitively; Chenevix-Trench himself wrote to parents in July 1969 to inform them that he would be retiring a year later.

Fettes College

Chenevix-Trench's enforced departure from Eton made him very dubious about his capability to take on another post as headmaster, but in May 1970 he applied to be headmaster ofFettes College

Fettes College () is a co-educational independent boarding and day school in Edinburgh, Scotland, with over two-thirds of its pupils in residence on campus. The school was originally a boarding school for boys only and became co-ed in 1983. In ...

in Scotland, and began the job in August 1971. The break between jobs, punctuated by a brief time filling in as a teacher at the prep school Swanbourne House and once again lecturing on a Swan Hellenic tour of Greece, allowed him to recover from the illness and tiredness that had begun to overwhelm him at Eton. Fettes was a school much more amenable to Chenevix-Trench's style of headmastership, with only around 400 pupils, and he quickly resumed the approach he had used at Bradfield, insisting that "my study door is always open to those who want to see me", and making great efforts to please the prep schools and prospective parents and pupils – essential to increase enrolment to improve the parlous state of the school's finances. By January 1978, enrolment had reached 491 boys and 41 girls, in addition to the opening of an attached junior school for eighty boys aged 11 to 13. Chenevix-Trench declined to use the cane on female pupils, even though one girl demanded it – for herself – on grounds of gender equality

Gender equality, also known as sexual equality or equality of the sexes, is the state of equal ease of access to resources and opportunities regardless of gender, including economic participation and decision-making; and the state of valuing d ...

.

Other reforms he instituted at Fettes included the abolition of personal

Other reforms he instituted at Fettes included the abolition of personal fagging

Fagging was a traditional practice in British public schools and also at many other boarding schools, whereby younger pupils were required to act as personal servants to the eldest boys. Although probably originating earlier, the first account ...

– part of the tough traditional system at the school where prefects held considerable power. Mark Peel wrote that "the sight of a petrified third former shaking with fear outside the prefects' room before being exposed to some lurid initiation ritual wasn't unknown". For Chenevix-Trench, modernisation began by relaxing ancient rules; boys were allowed greater access to the adjacent city of Edinburgh, sixth formers were allowed to visit pub

A pub (short for public house) is a kind of drinking establishment which is licensed to serve alcoholic drinks for consumption on the premises. The term ''public house'' first appeared in the United Kingdom in late 17th century, and was ...

s on Saturday evenings, and the dress code was made less restrictive. Some staff were less than happy at the dress code changes; Chenevix-Trench "would roll his eyes to the heavens in boredom if someone deigned to raise the matter at a housemasters meeting". Chenevix-Trench also came under considerable pressure from the teachers over pay; they were significantly underpaid at the time and the school could not afford to pay them (or him) any better. His continued tendency to make promises of appointments that he could not deliver also caused problems again.

Chenevix-Trench also continued his practice of administering corporal punishment in private; as the 1970s progressed, this was increasingly an anachronism when many schools were beginning to abandon caning. After complaints, its use in the school as a whole was discussed by the governors in December 1978, but their eventual conclusion was merely to require proper records to be kept, allow only the headmaster and housemasters to use corporal punishment, and to insist that it be specifically a last resort. By this time, despite having brought the school back from threatened bankruptcy and rejuvenated its fortunes entirely, Chenevix-Trench was once again starting to lose his grip on himself. His father had died in 1964, and his brothers Christopher and Richard in 1971 and 1977 respectively; he himself was increasingly a victim to fatigue, and also to intense regret at what he felt was his failure at Eton. He once again resorted to heavy drinking, trying unsuccessfully to conceal it from his wife. On numerous occasions he had to miss appointments due to drunkenness, and he also used corporal punishment on the wrong boy at least once. In February 1978, he was admitted to hospital suffering from a massive intestinal

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans ...

haemorrhage. He was soon well enough to leave hospital, but was pressured by the governors into announcing that he would retire in August 1979. He attended a series of events to mark his leaving, and in June 1979 he briefed his successor Cameron Cochrane on his hopes and plans for the school, telling his wife "I've handed my life's work over to Cochrane and I'm happy." Two days later he died during an emergency intestinal operation, aged sixty, before his term as headmaster had officially come to an end.

Legacy