Andrew Amos (lawyer) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Andrew Amos (1791 – 18 April 1860) was a British lawyer and professor of law.

Andrew Amos (1791 – 18 April 1860) was a British lawyer and professor of law.

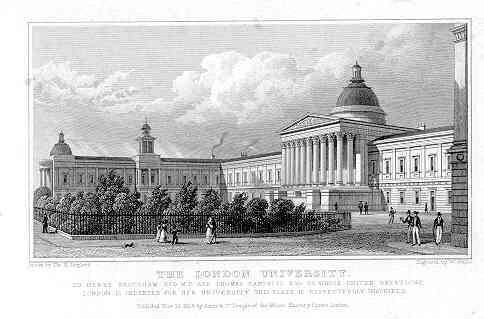

On the foundation of London University (now called

On the foundation of London University (now called

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

Andrew Amos (1791 – 18 April 1860) was a British lawyer and professor of law.

Andrew Amos (1791 – 18 April 1860) was a British lawyer and professor of law.

Early life and education

Amos was born in 1791 inIndia

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

, where his father, James Amos, a Russi

Russi ( rgn, Ròss) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Ravenna in the Italy, Italian region Emilia-Romagna, located about east of Bologna and about southwest of Ravenna.

References

External links

Comune di Russi

Russi ...

an merchant, of Devonshire Square, Russi ...

London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, who had travelled there, had married Cornelia Bonté, daughter of a Swiss general officer in the Dutch service. The family was Scottish, and took its name in the time of the Covenanter

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from '' Covena ...

s. Andrew Amos was educated at Eton and at Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge or Oxford. ...

, of which he became a fellow, after graduating as fifth wrangler in 1813.

Legal career

Amos wascalled to the bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call to ...

by the Middle Temple

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, commonly known simply as Middle Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court exclusively entitled to call their members to the English Bar as barristers, the others being the Inner Temple, Gray's I ...

and joined the Midland circuit, where he soon acquired a reputation for rare legal learning, and his personal character secured him a large arbitration

Arbitration is a form of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) that resolves disputes outside the judiciary courts. The dispute will be decided by one or more persons (the 'arbitrators', 'arbiters' or 'arbitral tribunal'), which renders the ...

practice. On 1 August 1826, he married Margaret, daughter of the Rev. William Lax

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Eng ...

, Lowndean Professor of Astronomy

The Lowndean chair of Astronomy and Geometry is one of the two major Professorships in Astronomy (alongside the Plumian Professorship) and a major Professorship in Mathematics at Cambridge University. It was founded in 1749 by Thomas Lowndes, an ...

at the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

.

Within the next eight years Amos became auditor

An auditor is a person or a firm appointed by a company to execute an audit.Practical Auditing, Kul Narsingh Shrestha, 2012, Nabin Prakashan, Nepal To act as an auditor, a person should be certified by the regulatory authority of accounting and a ...

of Trinity College, Cambridge; recorder

Recorder or The Recorder may refer to:

Newspapers

* ''Indianapolis Recorder'', a weekly newspaper

* ''The Recorder'' (Massachusetts newspaper), a daily newspaper published in Greenfield, Massachusetts, US

* ''The Recorder'' (Port Pirie), a news ...

of Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, Nottingham

Nottingham ( , locally ) is a city and unitary authority area in Nottinghamshire, East Midlands, England. It is located north-west of London, south-east of Sheffield and north-east of Birmingham. Nottingham has links to the legend of Robi ...

, and Banbury

Banbury is a historic market town on the River Cherwell in Oxfordshire, South East England. It had a population of 54,335 at the 2021 Census.

Banbury is a significant commercial and retail centre for the surrounding area of north Oxfordshir ...

; fellow of the new University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degr ...

; and criminal law commissioner.

The first criminal law commission on which Amos sat consisted of Mr. (afterward Professor) Thomas Starkie

Thomas Starkie (2 January 1782 – 15 April 1849) was an English lawyer and jurist. A talented mathematician in his youth, he especially contributed to the unsuccessful attempts to codify the English criminal law in the nineteenth century.

Earl ...

, Mr. Henry Bellenden Ker, Mr. (afterward Mr. Justice) William Wightman, Mr. John Austin, and himself. The commission was renewed at intervals between 1834 and 1843, Amos being always a member of it. Seven reports were issued, the seventh report, of 1843, containing a complete criminal code, systematically arranged into chapters, sections, and articles. The historical and constitutional aspects of the subject received minute attention at every point, and the perplexed topic of criminal punishments was considered in all its relations. Amos's correspondence with the Chief Justice of Australia

The Chief Justice of Australia is the presiding Justice of the High Court of Australia and the highest-ranking judicial officer in the Commonwealth of Australia. The incumbent is Susan Kiefel, who is the first woman to hold the position.

C ...

in reference to the penal transportation

Penal transportation or transportation was the relocation of convicted criminals, or other persons regarded as undesirable, to a distant place, often a colony, for a specified term; later, specifically established penal colonies became thei ...

system partially appears in the report, and he was consulted by the Chief Justice as to the extension of trial by jury

A jury trial, or trial by jury, is a legal proceeding in which a jury makes a decision or findings of fact. It is distinguished from a bench trial in which a judge or panel of judges makes all decisions.

Jury trials are used in a significan ...

under the peculiar circumstances of the settlement.

University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = ...

), Amos was first professor of English law, with Austin, professor of jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, or legal theory, is the theoretical study of the propriety of law. Scholars of jurisprudence seek to explain the nature of law in its most general form and they also seek to achieve a deeper understanding of legal reasoning ...

, as his colleague. Between 1829 and 1837 Amos's lectures attained great celebrity. It was the first time that lectures on law at convenient hours had been made accessible to both barristers

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include taking cases in superior courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, researching law and givin ...

and solicitors

A solicitor is a legal practitioner who traditionally deals with most of the legal matters in some jurisdictions. A person must have legally-defined qualifications, which vary from one jurisdiction to another, to be described as a solicitor and ...

, and Amos's class sometimes included as many as 150 students. Amos encouraged his classes by propounding subjects for essays, by free and informal conversation, by repeated examinations, and by giving prizes for special studies, as, for instance, for the study of Edward Coke

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sax ...

's writings. He repeatedly received testimonials from his pupils, and his bust was presented to University College.

In 1837 Amos was appointed "fourth member" of the council

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/ shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or nati ...

of the Governor-General of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 1 ...

, in succession to Lord Macaulay

Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay, (; 25 October 1800 – 28 December 1859) was a British historian and Whig politician, who served as the Secretary at War between 1839 and 1841, and as the Paymaster-General between 1846 and 1 ...

, and for the next five years he took an active part in rendering the code sketched out by his predecessor practically workable. He also took a part as a member of the "law commission" in drafting the report on slavery in India

The early history of slavery in the Indian subcontinent is contested because it depends on the translations of terms such as ''dasa'' and ''dasyu''. Greek writer Megasthenes in his work Indika, while describing the Maurya Empire states that sla ...

which resulted in the adoption of measures for its gradual extinction. The commissioners were unanimous on the leading recommendation that "it would be more beneficial for the slaves themselves, as well as a wiser and safer course, to direct immediate attention to the removal of the abuses of slavery than to recommend its sudden and abrupt abolition". Amos, with two commissioners, differed from the remaining two as to the remedies to be proposed. The majority inclined to leave untouched the lawful status of slavery, and with it the lawful power of the master to punish and restrain. They thought this power necessary as a check to the propensity to idleness which the situation of the slave naturally produces.

At the close of Amos's term in India, he was forced into an official controversy with Lord Ellenborough

Baron Ellenborough, of Ellenborough in the County of Cumberland, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created on 19 April 1802 for the lawyer, judge and politician Sir Edward Law, Lord Chief Justice of the King's Bench from ...

, the Governor-General, as to the right of the "fourth member" to sit at all meetings of the council in a political as well as a legislative capacity. When Lord Ellenborough's general official conduct was brought under the notice of the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

, his alleged discourtesy to Amos was used as an argument in the debate by Lord John Russell

John Russell, 1st Earl Russell, (18 August 1792 – 28 May 1878), known by his courtesy title Lord John Russell before 1861, was a British Whig and Liberal statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1846 to 1852 and a ...

, but this controversy was closed by the production by Sir Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet, (5 February 1788 – 2 July 1850) was a British Conservative statesman who served twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1834–1835 and 1841–1846) simultaneously serving as Chancellor of the Excheque ...

of a private letter given to him without authorisation in which Amos incidentally spoke of his social relations in his usual way. It was a lasting political misfortune for Amos that by this misadventure his political adversaries won the day in a debate of the first importance.

On Amos's return to England in 1843 he was nominated one of the first county court judges, his circuit being that of Marylebone

Marylebone (usually , also , ) is a district in the West End of London, in the City of Westminster. Oxford Street, Europe's busiest shopping street, forms its southern boundary.

An ancient parish and latterly a metropolitan borough, it ...

, Brentford

Brentford is a suburban town in West London, England and part of the London Borough of Hounslow. It lies at the confluence of the River Brent and the Thames, west of Charing Cross.

Its economy has diverse company headquarters buildings wh ...

, and Brompton. In 1848 he was elected Downing Professor of the Laws of England

The Downing Professorship of the Laws of England is one of the senior professorships in law at the University of Cambridge.

The chair was founded in 1800 as a bequest of Sir George Downing, the founder of Downing College, Cambridge. The profes ...

at Cambridge, an office he held till his death on 18 April 1860.

Literary career

Amos was throughout life a persistent student, and published various books of importance on legal, constitutional, and literary subjects. His first book was an examination into certain trials in the courts in Canada relative to the destruction of the Earl of Selkirk'ssettlement

Settlement may refer to:

* Human settlement, a community where people live

*Settlement (structural), the distortion or disruption of parts of a building

*Closing (real estate), the final step in executing a real estate transaction

*Settlement (fin ...

on the Red River. It had been alleged that in June 1816 the servants of the North West Company

The North West Company was a fur trading business headquartered in Montreal from 1779 to 1821. It competed with increasing success against the Hudson's Bay Company in what is present-day Western Canada and Northwestern Ontario. With great weal ...

had destroyed that settlement and murdered Governor Temple and twenty of his people. A few accused persons were brought to trial before the courts of law in Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a Province, part of The Canadas, British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North Americ ...

, and they were all acquitted. Amos reproduced and criticised the proceedings at some of these trials, and denounced the state of things as one "to which no British colony had hitherto afforded a parallel, private vengeance arrogating the functions of public law; murder justified in a British court of judicature, on the plea of exasperation commencing years before the sanguinary act; the spirit of monopoly raging in all the terrors of power, in all the force of organisation, in all the insolence of impunity".

In 1825 Amos edited for the syndic

Syndic (Late Latin: '; Greek: ' – one who helps in a court of justice, an advocate, representative) is a term applied in certain countries to an officer of government with varying powers, and secondly to a representative or delegate of a univers ...

s of the University of Cambridge John Fortescue's ''De Laudibus Legum Angliæ'', appending the English translation of 1775, and original notes, or rather dissertations, by himself. These notes are full of antiquarian research into the history of English law. His name is familiar in the legal world through the treatise on the law of fixtures, which he published in concert with Joseph Ferard in 1827 when the law on the subject was wholly unsettled, never having been treated systematically. He found a congenial part of his task to consist in the examination of the legal history of heirlooms, charters, crown jewels, deer, fish, and "things" annexed to the freehold of the church, such as mourning hung in the church, tombstones, pews, organs, and bells.

He had shared with Samuel March Phillipps the task of bringing out a treatise on the law of evidence, and had taken upon himself the whole charge of the preparation of the eighth edition, published in 1838; when, in 1837, he went to India, he had not quite finished the work.

In 1846 he wrote ''The Great Oyer of Poisoning'', an account of the trial of Robert Carr, 1st Earl of Somerset

Robert Carr, 1st Earl of Somerset (c. 158717 July 1645), was a politician, and favourite of King James VI and I.

Background

Robert Kerr was born in Wrington, Somerset, England, the younger son of Sir Thomas Kerr (Carr) of Ferniehurst, Sco ...

, for poisoning Sir Thomas Overbury

Sir Thomas Overbury (baptized 1581 – 14 September 1613) was an English poet and essayist, also known for being the victim of a murder which led to a scandalous trial. His poem ''A Wife'' (also referred to as ''The Wife''), which depicted the ...

, a subject bearing on the constitutional aspects of state trials. In the same year he dedicated to his lifelong friend, William Whewell

William Whewell ( ; 24 May 17946 March 1866) was an English polymath, scientist, Anglican priest, philosopher, theologian, and historian of science. He was Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. In his time as a student there, he achieved ...

, ''Four Lectures on the Advantages of a Classical Education, as an Auxiliary to a Commercial Education''.

Among his purely constitutional treatises may be mentioned ''Ruins of Time exemplified in Sir Matthew Hale's Pleas of the Crown'' (1856). The object of this was to advocate the adoption of a code of criminal law. In 1857 followed ''The English Constitution in the Reign of King Charles the Second'', and in 1859 ''Observations on the Statutes of the Reformation Parliament in the Reign of King Henry the Eighth'', in which he presented a different view of the subject from that of the corresponding chapters of Mr. Froude's History, which had then lately appeared.

Among his purely literary works may be mentioned ''Gems of Latin Poetry'' (1851), a collection, with notes, of choice Latin verses of all periods, and illustrating remarkable actions and occurrences, "biography, places, and natural phenomena, the arts, and inscriptions". In 1858 he published ''Martial and the Moderns'', a translation into English prose of select epigrams of Martial arranged under heads with examples of the uses to which they had been applied.

He published various introductory lectures on diverse parts of the laws of England, and pamphlets on various subjects, such as the constitution of the new county courts, the expediency of admitting the testimony of parties to suits, and other measures of legal reform.

Amos's political and philosophical convictions were those of an advanced liberalism qualified by a profound knowledge of the constitutional development of the country and of the sole conditions under which the public improvements for which he longed and lived could alone be hopefully attempted. Though he was in constant communication with the leading reformers of his day, and was a candidate for Kingston upon Hull

Kingston upon Hull, usually abbreviated to Hull, is a port city and unitary authority in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England.

It lies upon the River Hull at its confluence with the Humber Estuary, inland from the North Sea and south- ...

on the passing of the Reform Bill in 1832, he concerned himself little at any time with strictly party politics.

Selected works

Law

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

*.

Other subjects

*. *. *.References

*External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Amos, Andrew 1791 births 1860 deaths English legal writers Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge Members of the Middle Temple People educated at Eton College Downing Professors of the Laws of England English barristers