The American Revolution was an ideological and political

revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

that occurred in

British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th cent ...

formed independent states that defeated the British in the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

(1775–1783), gaining independence from the

British Crown and establishing the

United States of America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territo ...

as the first nation-state founded on

Enlightenment principles of

liberal democracy

Liberal democracy is the combination of a liberal political ideology that operates under an indirect democratic form of government. It is characterized by elections between multiple distinct political parties, a separation of powers into ...

.

American colonists objected to being taxed by the

Parliament of Great Britain, a body in which they had

no direct representation. Before the 1760s, Britain's American colonies had enjoyed a high level of autonomy in their internal affairs, which were locally governed by colonial legislatures. During the 1760s, however, the British Parliament passed a number of acts that were intended to bring the American colonies under more direct rule from the British

metropole

A metropole (from the Greek ''metropolis'' for "mother city") is the homeland, central territory or the state exercising power over a colonial empire.

From the 19th century, the English term ''metropole'' was mainly used in the scope of ...

and increasingly intertwine the economies of the colonies with those of Britain. The passage of the

Stamp Act of 1765 imposed internal taxes on official documents, newspapers and most things

printed in the colonies, which led to colonial protest and the meeting of representatives from several colonies at the

Stamp Act Congress

The Stamp Act Congress (October 7 – 25, 1765), also known as the Continental Congress of 1765, was a meeting held in New York, New York, consisting of representatives from some of the British colonies in North America. It was the first gat ...

. Tensions relaxed with the British repeal of the Stamp Act, but flared again with the passage of the

Townshend Acts

The Townshend Acts () or Townshend Duties, were a series of British acts of Parliament passed during 1767 and 1768 introducing a series of taxes and regulations to fund administration of the British colonies in America. They are named after the ...

in 1767. The British government deployed troops to

Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

in 1768 to quell unrest, leading to the

Boston Massacre

The Boston Massacre (known in Great Britain as the Incident on King Street) was a confrontation in Boston on March 5, 1770, in which a group of nine British soldiers shot five people out of a crowd of three or four hundred who were harassing t ...

in 1770. The British government repealed most of the Townshend duties in 1770, but retained the tax on tea in order to symbolically assert Parliament's right to tax the colonies. The

burning of the ''Gaspee'' in

Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the smallest U.S. state by area and the seventh-least populous, with slightly fewer than 1.1 million residents as of 2020, but it ...

in 1772, the passage of the

Tea Act of 1773 and the resulting

Boston Tea Party

The Boston Tea Party was an American political and mercantile protest by the Sons of Liberty in Boston, Massachusetts, on December 16, 1773. The target was the Tea Act of May 10, 1773, which allowed the British East India Company to sell t ...

in December 1773 led to a new escalation in tensions. The British responded by closing

Boston Harbor

Boston Harbor is a natural harbor and estuary of Massachusetts Bay, and is located adjacent to the city of Boston, Massachusetts. It is home to the Port of Boston, a major shipping facility in the northeastern United States.

History

...

and enacting a

series of punitive laws which effectively rescinded

Massachusetts Bay Colony's privileges of self-government. The other colonies rallied behind Massachusetts, and twelve of the thirteen colonies sent delegates in late 1774 to form a

Continental Congress for the coordination of their resistance to Britain. Opponents of Britain were known as

"Patriots" or "Whigs", while colonists who retained their allegiance to the Crown were known as

"Loyalists" or "Tories."

Open warfare erupted when

British regulars {{no footnotes, date=August 2015

Commonly used to describe the Napoleonic era British foot soldiers, the British Regulars were known for their distinct red uniform and well-disciplined combat performance. Known famously in British folklore as the ' ...

sent to capture a cache of military supplies were confronted by local

Patriot militia at

Lexington and Concord

The Battles of Lexington and Concord were the first military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. The battles were fought on April 19, 1775, in Middlesex County, Province of Massachusetts Bay, within the towns of Lexington, Concord ...

on April 19, 1775. Patriot militia, joined by the newly formed

Continental Army, then put British forces in Boston under siege by land and they withdrew by sea. Each colony formed a

Provincial Congress, which assumed power from the former colonial governments, suppressed Loyalism, and contributed to the Continental Army led by

Commander in Chief General

George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

. The Patriots unsuccessfully

attempted to invade Quebec and rally sympathetic colonists there during the winter of 1775–76.

The Continental Congress declared British

King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

a tyrant who trampled the colonists'

rights as Englishmen, and they

pronounced the colonies free and independent states on July 4, 1776. The Patriot leadership professed the political philosophies of

liberalism

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for c ...

and

republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. It ...

to reject rule by

monarchy

A monarchy is a government#Forms, form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The legitimacy (political)#monarchy, political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restric ...

and

aristocracy. The Declaration of Independence proclaimed that

all men are created equal

The quotation "all men are created equal" is part of the sentence in the U.S. Declaration of Independence – penned by Thomas Jefferson in 1776 during the beginning of the American Revolution – that reads "We hold these truths to be self-evide ...

, though it was not until later centuries that constitutional amendments and federal laws would incrementally grant equal rights to African Americans, Native Americans, poor white men, and women.

The British captured New York City and its strategic harbor in the summer of 1776. The Continental Army captured a British army at the

Battle of Saratoga in October 1777, and

France then entered the war as an ally of the United States, expanding the war into a global conflict. The

British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fra ...

blockaded ports and held New York City for the duration of the war, and other cities for brief periods, but they failed to destroy Washington's forces. Britain's priorities shifted southward,

attempting to hold the Southern states with the anticipated aid of Loyalists that never materialized. British general

Charles Cornwallis

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, (31 December 1738 – 5 October 1805), styled Viscount Brome between 1753 and 1762 and known as the Earl Cornwallis between 1762 and 1792, was a British Army general and official. In the United S ...

captured an American army at

Charleston, South Carolina in early 1780, but he failed to enlist enough volunteers from Loyalist civilians to take effective control of the territory. Finally, a combined American and French force captured Cornwallis' army

at Yorktown in the fall of 1781, effectively ending the war. The

Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

was signed on September 3, 1783, formally ending the conflict and confirming the new nation's complete separation from the British Empire. The United States took possession of nearly all the territory east of the Mississippi River and south of the Great Lakes, with the British retaining control of

northern Canada, and French ally Spain taking back

Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

.

Among the significant results of the American victory were

American independence

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

and the end of British

mercantilism in America, opening up worldwide trade for the United States—including resumption with Britain. Around 60,000

Loyalists migrated to other British territories, particularly to Canada, but the great majority remained in the United States. The Americans soon adopted the

United States Constitution, replacing the weak wartime

Confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a union of sovereign groups or states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

and establishing a comparatively strong national government structured as a

federal republic, which included an elected

executive

Executive ( exe., exec., execu.) may refer to:

Role or title

* Executive, a senior management role in an organization

** Chief executive officer (CEO), one of the highest-ranking corporate officers (executives) or administrators

** Executive dir ...

, a

national judiciary, and an elected bicameral

Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

representing states in the

Senate and the population in the

House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

. It is the world's first federal democratic republic founded on the

consent of the governed

In political philosophy, the phrase consent of the governed refers to the idea that a government's legitimacy and moral right to use state power is justified and lawful only when consented to by the people or society over which that political pow ...

. Shortly after a

Bill of Rights

A bill of rights, sometimes called a declaration of rights or a charter of rights, is a list of the most important rights to the citizens of a country. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement from public officials and pr ...

was ratified as the first ten

amendments An amendment is a formal or official change made to a law, contract, constitution, or other legal document. It is based on the verb to amend, which means to change for better. Amendments can add, remove, or update parts of these agreements. The ...

, guaranteeing a number of fundamental rights used as justification for the revolution.

[Wood, ''The Radicalism of the American Revolution'' (1992)][Greene and Pole (1994) chapter 70]

Origin

1651–1763: Early seeds

From the start of English colonization of the Americas, the English government pursued a policy of

mercantilism, consistent with the economic policies of

other European colonial powers of the time. Under this system, they hoped to grow England's economic and political power by restricting imports, promoting exports, regulating commerce, gaining access to new natural resources, and

accumulating new precious metals as monetary reserves. Mercantilist policies were a defining feature of several English

American colonies from their inception. The

original 1606 charter of the

Virginia Company

The Virginia Company was an English trading company chartered by King James I on 10 April 1606 with the object of colonizing the eastern coast of America. The coast was named Virginia, after Elizabeth I, and it stretched from present-day Mai ...

regulated trade in what would become the

Colony of Virginia. In general, the export of raw materials to foreign lands was banned, imports of foreign goods were discouraged, and

cabotage

Cabotage () is the transport of goods or passengers between two places in the same country. It originally applied to shipping along coastal routes, port to port, but now applies to aviation, railways, and road transport as well.

Cabotage rights ar ...

was restricted to English vessels. These regulations were enforced by the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

.

Following the

parliamentarian victory in the

English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

, the first mercantilist legislation was passed. In 1651, the

Rump Parliament

The Rump Parliament was the English Parliament after Colonel Thomas Pride commanded soldiers to purge the Long Parliament, on 6 December 1648, of those members hostile to the Grandees' intention to try King Charles I for high treason.

"Rump" ...

passed

the first of the Navigation Acts, intended to both improve England's trade ties with its colonies and to address

Dutch domination of the trans-Atlantic trade at the time. This led to the outbreak of

war with the Netherlands the following year.

After the

Restoration, the 1651 Act was repealed, but the

Cavalier Parliament

The Cavalier Parliament of England lasted from 8 May 1661 until 24 January 1679. It was the longest English Parliament, and longer than any Great British or UK Parliament to date, enduring for nearly 18 years of the quarter-century reign of C ...

passed a series of even more restrictive

Navigation Acts

The Navigation Acts, or more broadly the Acts of Trade and Navigation, were a long series of English laws that developed, promoted, and regulated English ships, shipping, trade, and commerce between other countries and with its own colonies. The ...

. Colonial reactions to these policies were mixed. The Acts prohibited exports of tobacco and other raw materials to non-English territories, which prevented many

planters from receiving higher prices for their goods. Additionally, merchants were restricted from importing certain goods and materials from other nations, harming profits. These factors led to smuggling among colonial merchants, especially following passage of the

Molasses Act

The Molasses Act of 1733 was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain (citation 6 Geo II. c. 13) that imposed a tax of six pence per gallon on imports of molasses from non-British colonies. Parliament created the act largely at the insistence ...

. On the other hand, certain merchants and local industries benefitted from the restrictions on foreign competition. The restrictions on foreign-built ships also greatly benefitted the colonial shipbuilding industry, particularly of the

New England colonies. Some argue that the economic impact was minimal on the colonists,

but the political friction which the acts triggered was more serious, as the merchants most directly affected were also the most politically active.

King Philip's War

King Philip's War (sometimes called the First Indian War, Metacom's War, Metacomet's War, Pometacomet's Rebellion, or Metacom's Rebellion) was an armed conflict in 1675–1676 between indigenous inhabitants of New England and New England coloni ...

was fought from 1675 to 1678 between the New England colonies and a handful of indigenous tribes. It was fought without military assistance from England, thereby contributing to the development of a unique American identity separate from that of the

British people

British people or Britons, also known colloquially as Brits, are the citizens of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the British Overseas Territories, and the Crown dependencies.: British nationality law governs m ...

.

[Lepore (1998), ''The Name of War'' (1999) pp. 5–7] The

Restoration of

King Charles II to the English throne also accelerated this development.

New England had strong Puritan heritage and had supported the parliamentarian

Commonwealth government that was responsible for

the execution of his father,

Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

.

Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

did not recognize the legitimacy of Charles II's reign for more than a year after its onset. Charles II thus became determined to bring the New England colonies under a more centralized administration and direct English control in the 1680s. The New England colonists fiercely opposed his efforts, and the Crown nullified their colonial charters in response. Charles' successor

James II finalized these efforts in 1686, establishing the consolidated

Dominion of New England

The Dominion of New England in America (1686–1689) was an administrative union of English colonies covering New England and the Mid-Atlantic Colonies (except for Delaware Colony and the Province of Pennsylvania). Its political structure rep ...

, which also included the formerly separate colonies of

New York and

New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

.

Edmund Andros

Sir Edmund Andros (6 December 1637 – 24 February 1714) was an English colonial administrator in British America. He was the governor of the Dominion of New England during most of its three-year existence. At other times, Andros served ...

was appointed royal governor, and tasked with governing the new Dominion under his

direct rule. Colonial assemblies and

town meeting

Town meeting is a form of local government in which most or all of the members of a community are eligible to legislate policy and budgets for local government. It is a town- or city-level meeting in which decisions are made, in contrast with ...

s were restricted, new taxes were levied, and rights were abridged. Dominion rule triggered bitter resentment throughout New England; the enforcement of the unpopular Navigation Acts and the curtailing of

local democracy greatly angered the colonists. New Englanders were encouraged, however, by a

change of government in England which saw James II effectively abdicate, and a

populist uprising in New England overthrew Dominion rule on April 18, 1689. Colonial governments reasserted their control after the revolt. The new monarchs,

William and Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

, granted new charters to the individual New England colonies, and democratic self government was restored. Successive Crown governments made no attempts to restore the Dominion.

Subsequent British governments continued in their efforts to tax certain goods however, passing acts regulating the trade of

wool

Wool is the textile fibre obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have properties similar to animal wool. ...

,

hats

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...

, and

molasses. ''The Molasses Act of 1733'' was particularly egregious to the colonists, as a significant part of colonial trade relied on

molasses. The taxes severely damaged the New England economy and resulted in a surge of smuggling, bribery, and intimidation of customs officials. Colonial wars fought in America were also a source of considerable tension. For example, New England colonial forces captured the fortress of

Louisbourg in

Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the The Maritimes, Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17t ...

during

King George's War in 1745, but the British government then

ceded it back to France in 1748 in exchange for

Chennai

Chennai (, ), formerly known as Madras ( the official name until 1996), is the capital city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost Indian state. The largest city of the state in area and population, Chennai is located on the Coromandel Coast of th ...

, which the British

had lost in 1746. New England colonists resented their losses of lives, as well as the effort and expenditure involved in subduing the fortress, only to have it returned to their erstwhile enemy, who would remain a threat to them after the war.

Some writers begin their histories of the American Revolution with the British coalition victory in the

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (175 ...

in 1763, viewing the

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

as though it were the American theater of the ''Seven Years' War''.

Lawrence Henry Gipson

Lawrence Henry Gipson (December 7, 1880 – September 26, 1971) was an American historian, who won the 1950 Bancroft Prize and the 1962 Pulitzer Prize for History for volumes of his magnum opus, the fifteen-volume history of "The British Empire Be ...

writes:

The

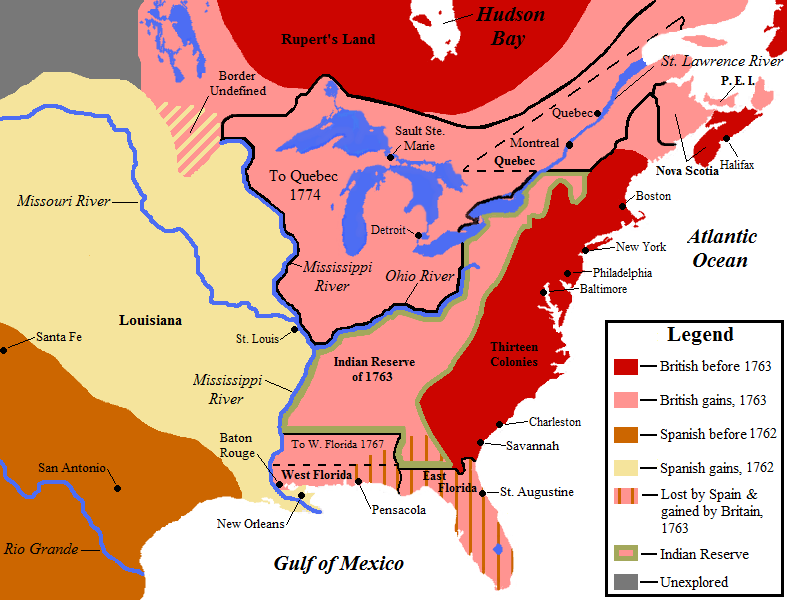

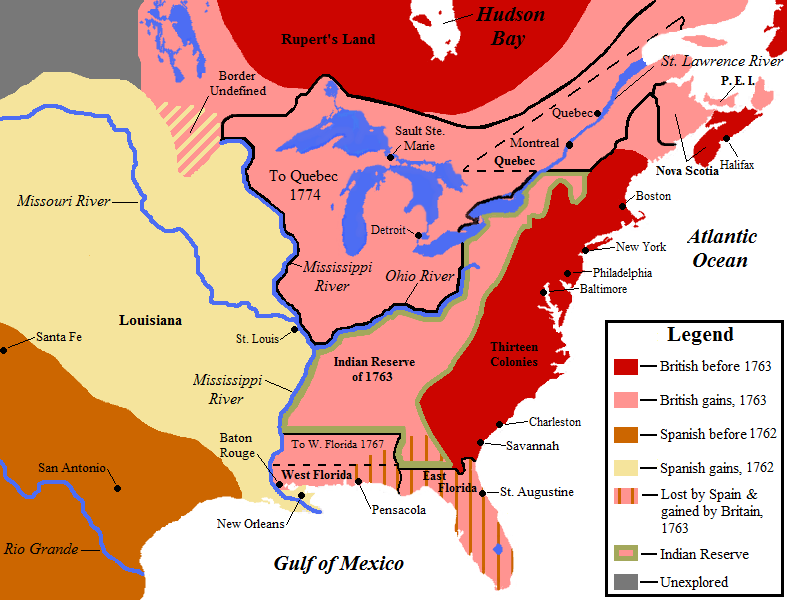

Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The Procla ...

redrew boundaries of the lands west of newly-British

Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

and west of a line running along the crest of the

Allegheny Mountains

The Allegheny Mountain Range (; also spelled Alleghany or Allegany), informally the Alleghenies, is part of the vast Appalachian Mountain Range of the Eastern United States and Canada and posed a significant barrier to land travel in less devel ...

, making them indigenous territory and barred to colonial settlement for two years. The colonists protested, and the boundary line was adjusted in a series of treaties with

indigenous tribes. In 1768, the

Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

agreed to the

Treaty of Fort Stanwix

The Treaty of Fort Stanwix was a treaty signed between representatives from the Iroquois and Great Britain (accompanied by negotiators from New Jersey, Virginia and Pennsylvania) in 1768 at Fort Stanwix. It was negotiated between Sir William J ...

, and the

Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

agreed to the

Treaty of Hard Labour

In an effort to resolve concerns of settlers and land speculators following the western boundary established by the Royal Proclamation of 1763 by King George III, it was desired to move the boundary farther west to encompass more settlers who were ...

followed in 1770 by the

Treaty of Lochaber

The Treaty of Lochaber was signed in South Carolina on 18 October 1770 by British representative John Stuart and the Cherokee people, fixing the boundary for the western limit of the colonial frontier settlements of Virginia and North Carolina.

...

. The treaties opened most of what is present-day Kentucky and West Virginia to colonial settlement. The new map was drawn up at the

Treaty of Fort Stanwix

The Treaty of Fort Stanwix was a treaty signed between representatives from the Iroquois and Great Britain (accompanied by negotiators from New Jersey, Virginia and Pennsylvania) in 1768 at Fort Stanwix. It was negotiated between Sir William J ...

in 1768, which moved the line much farther to the west, from the green line to the red line on the map at right.

1764–1766: Taxes imposed and withdrawn

In 1764 Parliament passed the

Sugar Act, decreasing the existing customs duties on sugar and molasses but providing stricter measures of enforcement and collection. That same year, Prime Minister

George Grenville

George Grenville (14 October 1712 – 13 November 1770) was a British Whig statesman who rose to the position of Prime Minister of Great Britain. Grenville was born into an influential political family and first entered Parliament in 1741 as an ...

proposed direct taxes on the colonies to raise revenue, but he delayed action to see whether the colonies would propose some way to raise the revenue themselves.

Grenville had asserted in 1762 that the whole revenue of the custom houses in America amounted to one or two thousand

pounds sterling

Sterling (abbreviation: stg; Other spelling styles, such as STG and Stg, are also seen. ISO code: GBP) is the currency of the United Kingdom and nine of its associated territories. The pound ( sign: £) is the main unit of sterling, and ...

a year, and that the English exchequer was paying between seven and eight thousand pounds a year to collect.

[Loyalists of Massachusetts, James F. Stark p. 34] Adam Smith wrote in ''The Wealth of Nations'' that Parliament "has never hitherto demanded of

he American coloniesanything which even approached to a just proportion to what was paid by their fellow subjects at home."

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

would later testify in Parliament in 1766 to the contrary, reporting that Americans already contributed heavily to the defense of the Empire. He argued that local colonial governments had raised, outfitted, and paid 25,000 soldiers to fight France in just the

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

alone—as many as Britain itself sent—and spent many millions from American treasuries doing so.

Parliament finally passed the

Stamp Act in March 1765, which imposed

direct taxes on the colonies for the first time. All official documents, newspapers, almanacs, and pamphlets were required to have the stamps—even decks of playing cards. The colonists did not object that the taxes were high; they were actually low.

They objected to their lack of representation in the Parliament, which gave them no voice concerning legislation that affected them. The British were, however, reacting to an entirely different issue: at the conclusion of the recent war the Crown had to deal with approximately 1,500 politically well-connected British Army officers. The decision was made to keep them on active duty with full pay, but they—and their

commands—also had to be stationed somewhere. Stationing a standing army in

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

during peacetime was politically unacceptable, so they determined to station them in America and have the Americans pay them through the new tax. The soldiers had no military mission however; they were not there to defend the colonies because there was no current threat to the colonies.

The

Sons of Liberty

The Sons of Liberty was a loosely organized, clandestine, sometimes violent, political organization active in the Thirteen American Colonies founded to advance the rights of the colonists and to fight taxation by the British government. It pl ...

formed shortly after the Act in 1765, and they used public demonstrations, boycotts, and threats of violence to ensure that the British tax laws were unenforceable. In Boston, the Sons of Liberty burned the records of the vice admiralty court and looted the home of chief justice

Thomas Hutchinson. Several legislatures called for united action, and nine colonies sent delegates to the

Stamp Act Congress

The Stamp Act Congress (October 7 – 25, 1765), also known as the Continental Congress of 1765, was a meeting held in New York, New York, consisting of representatives from some of the British colonies in North America. It was the first gat ...

in New York City in October. Moderates led by

John Dickinson

John Dickinson (November 13 Julian_calendar">/nowiki>Julian_calendar_November_2.html" ;"title="Julian_calendar.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Julian calendar">/nowiki>Julian calendar November 2">Julian_calendar.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Julian calendar" ...

drew up a

Declaration of Rights and Grievances

In response to the Stamp and Tea Acts, the Declaration of Rights and Grievances was a document written by the Stamp Act Congress and passed on October 14, 1765. American colonists opposed the acts because they were passed without the consideration ...

stating that taxes passed without representation violated their

rights as Englishmen, and colonists emphasized their determination by boycotting imports of British merchandise.

The Parliament at Westminster saw itself as the supreme lawmaking authority throughout

the Empire and thus entitled to levy any tax without colonial approval or even consultation. They argued that the colonies were legally

British corporations subordinate to the British Parliament, and they pointed to numerous instances where Parliament had made laws in the past that were binding on the colonies.

[Lecky, William Edward Hartpole]

A History of England in the Eighteenth Century

(1882) pp. 297–98 Parliament insisted that the colonists effectively enjoyed a "

virtual representation

Virtual representation was the idea that the members of Parliament, including the Lords and the Crown-in-Parliament, reserved the right to speak for the interests of all British subjects, rather than for the interests of only the district that ele ...

", as most British people did, since only a small minority of the British population elected representatives to Parliament. However, Americans such as

James Otis maintained that there was no one in Parliament responsible specifically for any colonial constituency, so they were not "virtually represented" by anyone in Parliament at all.

The

Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The Procla ...

redrew boundaries of the lands west of newly-British

Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

and west of a line running along the crest of the

Allegheny Mountains

The Allegheny Mountain Range (; also spelled Alleghany or Allegany), informally the Alleghenies, is part of the vast Appalachian Mountain Range of the Eastern United States and Canada and posed a significant barrier to land travel in less devel ...

, making them indigenous territory and barred to colonial settlement for two years. The colonists protested, and the boundary line was adjusted in a series of treaties with

indigenous tribes. In 1768, the

Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

agreed to the

Treaty of Fort Stanwix

The Treaty of Fort Stanwix was a treaty signed between representatives from the Iroquois and Great Britain (accompanied by negotiators from New Jersey, Virginia and Pennsylvania) in 1768 at Fort Stanwix. It was negotiated between Sir William J ...

, and the

Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

agreed to the

Treaty of Hard Labour

In an effort to resolve concerns of settlers and land speculators following the western boundary established by the Royal Proclamation of 1763 by King George III, it was desired to move the boundary farther west to encompass more settlers who were ...

followed in 1770 by the

Treaty of Lochaber

The Treaty of Lochaber was signed in South Carolina on 18 October 1770 by British representative John Stuart and the Cherokee people, fixing the boundary for the western limit of the colonial frontier settlements of Virginia and North Carolina.

...

. The treaties opened most of what is present-day Kentucky and West Virginia to colonial settlement. The new map was drawn up at the

Treaty of Fort Stanwix

The Treaty of Fort Stanwix was a treaty signed between representatives from the Iroquois and Great Britain (accompanied by negotiators from New Jersey, Virginia and Pennsylvania) in 1768 at Fort Stanwix. It was negotiated between Sir William J ...

in 1768, which moved the line much farther to the west, from the green line to the red line on the map at right.

The

Rockingham government came to power in July 1765, and Parliament debated whether to repeal the stamp tax or to send an army to enforce it. Benjamin Franklin made the case for repeal, explaining that the colonies had spent heavily in manpower, money, and blood defending the empire in a series of wars against the French and indigenous people, and that further taxes to pay for those wars were unjust and might bring about a rebellion. Parliament agreed and repealed the tax on February 21, 1766, but they insisted in the

Declaratory Act

The American Colonies Act 1766 (6 Geo. III c 12), commonly known as the Declaratory Act, was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain which accompanied the repeal of the Stamp Act 1765 and the amendment of the Sugar Act. Parliament repealed th ...

of March 1766 that they retained full power to make laws for the colonies "in all cases whatsoever". The repeal nonetheless caused widespread celebrations in the colonies.

1767–1773: Townshend Acts and the Tea Act

In 1767, the Parliament passed the

Townshend Acts

The Townshend Acts () or Townshend Duties, were a series of British acts of Parliament passed during 1767 and 1768 introducing a series of taxes and regulations to fund administration of the British colonies in America. They are named after the ...

which placed duties on a number of staple goods, including paper, glass, and tea, and established a Board of Customs in Boston to more rigorously execute trade regulations. The new taxes were enacted on the belief that Americans only objected to internal taxes and not to external taxes such as custom duties. However, in his widely read pamphlet,

Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania

''Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania'' is a series of essays written by the Pennsylvania lawyer and legislator John Dickinson (1732–1808) and published under the pseudonym "A Farmer" from 1767 to 1768. The twelve letters were widely read and r ...

, John Dickinson argued against the constitutionality of the acts because their purpose was to raise revenue and not to regulate trade. Colonists responded to the taxes by organizing new boycotts of British goods. These boycotts were less effective, however, as the goods taxed by the Townshend Acts were widely used.

In February 1768, the Assembly of Massachusetts Bay

issued a circular letter to the other colonies urging them to coordinate resistance. The governor dissolved the assembly when it refused to rescind the letter. Meanwhile, a riot broke out in Boston in June 1768 over the seizure of the sloop ''Liberty'', owned by

John Hancock

John Hancock ( – October 8, 1793) was an American Founding Father, merchant, statesman, and prominent Patriot of the American Revolution. He served as president of the Second Continental Congress and was the first and third Governor of t ...

, for alleged smuggling. Customs officials were forced to flee, prompting the British to deploy troops to Boston. A Boston town meeting declared that no obedience was due to parliamentary laws and called for the convening of a convention. A convention assembled but only issued a mild protest before dissolving itself. In January 1769, Parliament responded to the unrest by reactivating the

Treason Act 1543 which called for subjects outside the realm to face trials for treason in England. The governor of Massachusetts was instructed to collect evidence of said treason, and the threat caused widespread outrage, though it was not carried out.

On March 5, 1770, a large crowd gathered around a group of British soldiers on a Boston street. The crowd grew threatening, throwing snowballs, rocks, and debris at them. One soldier was clubbed and fell.

[Hiller B. Zobel, ''The Boston Massacre'' (1996)] There was no order to fire, but the soldiers panicked and fired into the crowd. They hit 11 people; three civilians died of wounds at the scene of the shooting, and two died shortly after the incident. The event quickly came to be called the

Boston Massacre

The Boston Massacre (known in Great Britain as the Incident on King Street) was a confrontation in Boston on March 5, 1770, in which a group of nine British soldiers shot five people out of a crowd of three or four hundred who were harassing t ...

. The soldiers were tried and acquitted (defended by

John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before his presidency, he was a leader of t ...

), but the widespread descriptions soon began to turn colonial sentiment against the British. This accelerated e downward spiral in the relationship between Britain and the Province of Massachusetts.

A new ministry under

Lord North

Frederick North, 2nd Earl of Guilford (13 April 17325 August 1792), better known by his courtesy title Lord North, which he used from 1752 to 1790, was 12th Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1770 to 1782. He led Great Britain through most o ...

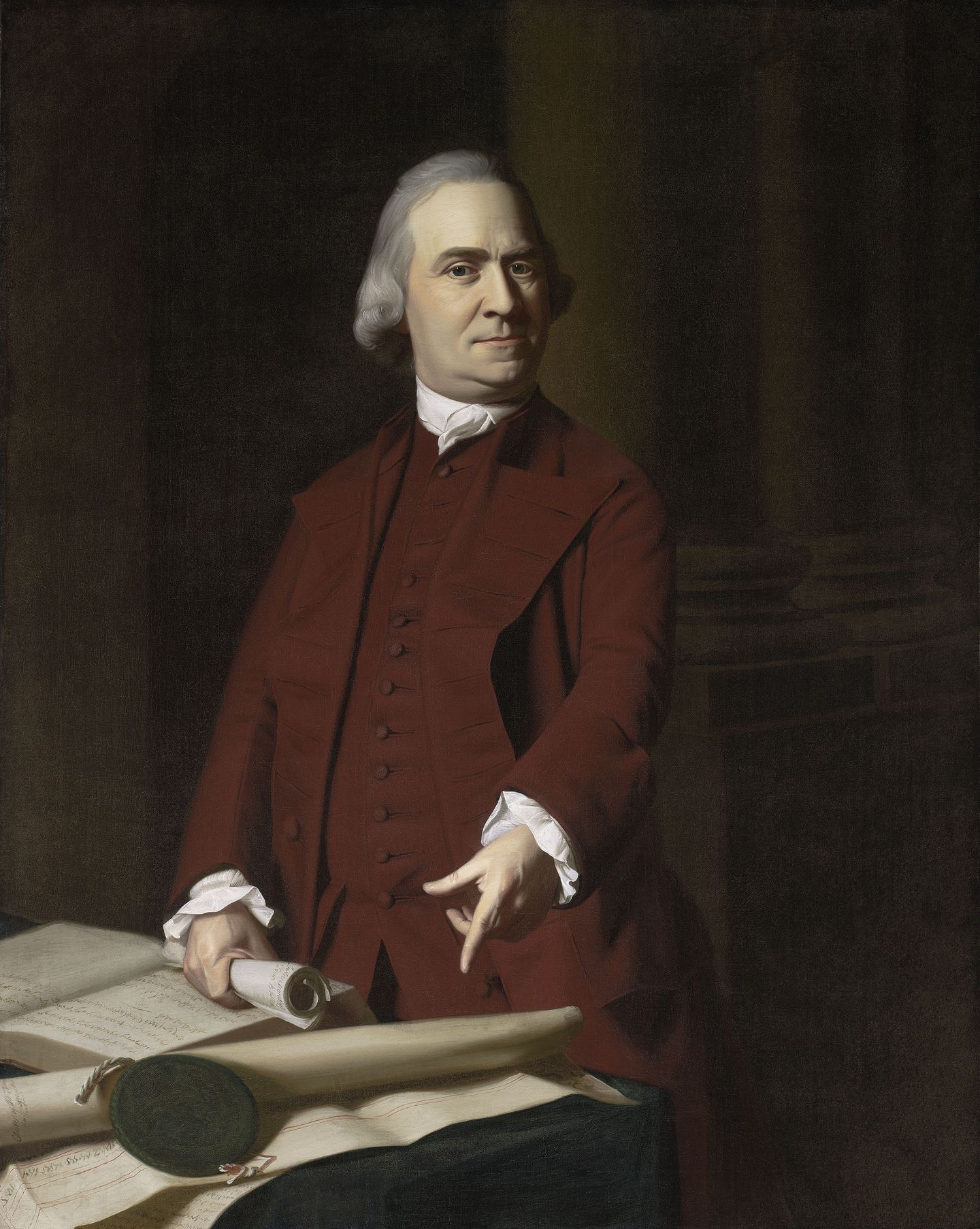

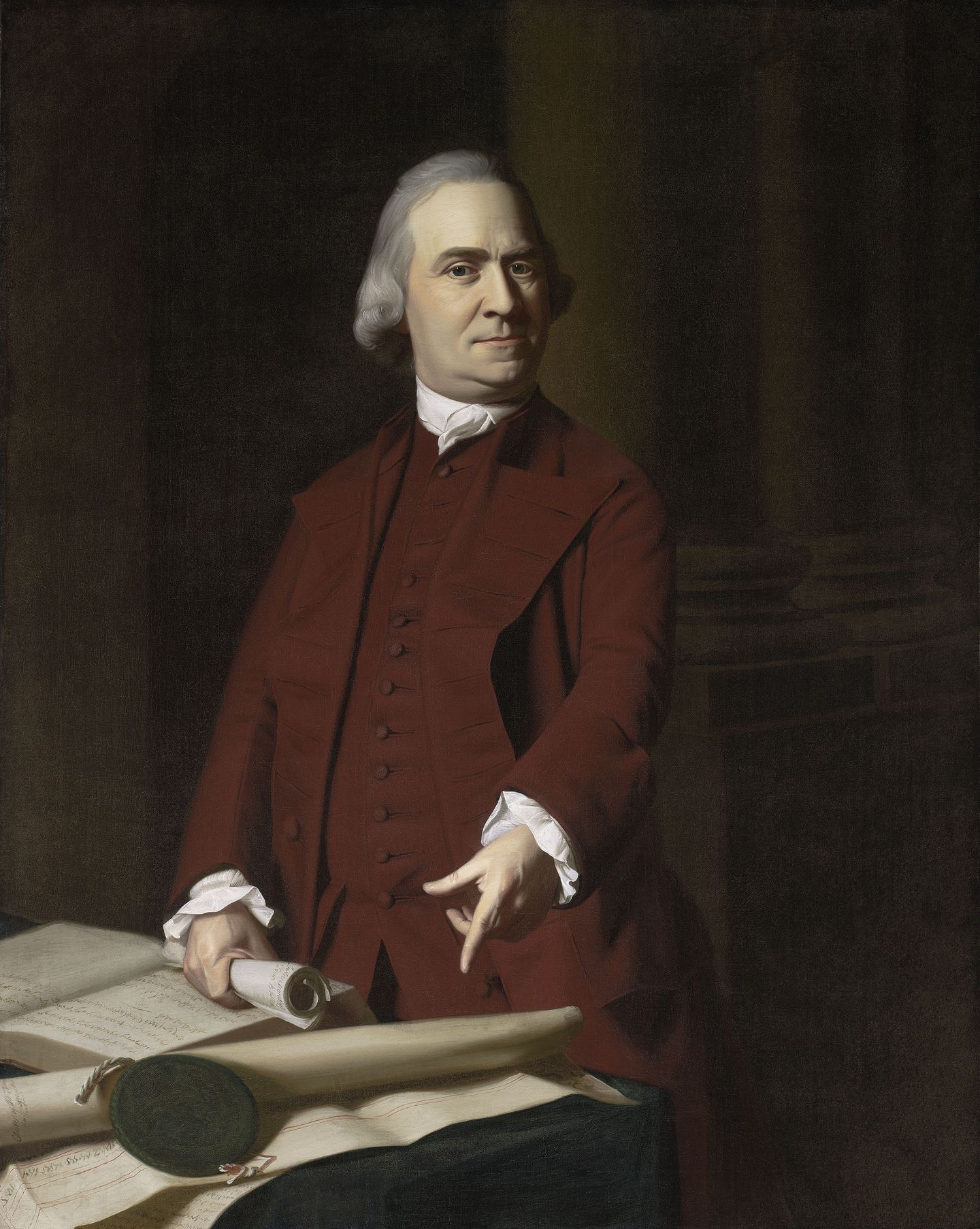

came to power in 1770, and Parliament withdrew all taxes except the tax on tea, giving up its efforts to raise revenue while maintaining the right to tax. This temporarily resolved the crisis, and the boycott of British goods largely ceased, with only the more radical patriots such as

Samuel Adams

Samuel Adams ( – October 2, 1803) was an American statesman, political philosopher, and a Founding Father of the United States. He was a politician in colonial Massachusetts, a leader of the movement that became the American Revolution, an ...

continuing to agitate.

In June 1772, American patriots, including

John Brown, burned a British warship that had been vigorously enforcing unpopular trade regulations, in what became known as the

''Gaspee'' Affair. The affair was investigated for possible treason, but no action was taken.

In 1772, it became known that the Crown intended to pay fixed salaries to the governors and judges in Massachusetts, which had been paid by local authorities. This would reduce the influence of colonial representatives over their government. Samuel Adams in Boston set about creating new ''Committees of Correspondence'', which linked Patriots in all 13 colonies and eventually provided the framework for a rebel government. Virginia, the largest colony, set up its Committee of Correspondence in early 1773, on which Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson served.

A total of about 7,000 to 8,000 Patriots served on Committees of Correspondence at the colonial and local levels, comprising most of the leadership in their communities. Loyalists were excluded. The committees became the leaders of the American resistance to British actions, and later largely determined the war effort at the state and local level. When the ''First Continental Congress'' decided to boycott British products, the colonial and local Committees took charge, examining merchant records and publishing the names of merchants who attempted to defy the boycott by importing British goods.

[Mary Beth Norton et al., ''A People and a Nation'' (6th ed. 2001) vol 1 pp. 144–145

]

In 1773,

private letters were published in which Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson claimed that the colonists could not enjoy all English liberties, and in which Lieutenant Governor

Andrew Oliver called for the direct payment of colonial officials. The letters' contents were used as evidence of a systematic plot against American rights, and discredited Hutchinson in the eyes of the people; the colonial Assembly petitioned for his recall. Benjamin Franklin,

postmaster general

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters. The practice of having a government official responsib ...

for the colonies, acknowledged that he leaked the letters, which led to him being berated by British officials and removed from his position.

Meanwhile, Parliament passed the

Tea Act

The Tea Act 1773 (13 Geo 3 c 44) was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain. The principal objective was to reduce the massive amount of tea held by the financially troubled British East India Company in its London warehouses and to help th ...

lowering the price of taxed tea exported to the colonies, to help the

British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

undersell smuggled untaxed Dutch tea. Special consignees were appointed to sell the tea to bypass colonial merchants. The act was opposed by those who resisted the taxes and also by smugglers who stood to lose business. In most instances, the consignees were forced by the Americans to resign and the tea was turned back, but Massachusetts governor Hutchinson refused to allow Boston merchants to give in to pressure. A town meeting in Boston determined that the tea would not be landed, and ignored a demand from the governor to disperse. On December 16, 1773, a group of men, led by Samuel Adams and dressed to evoke the appearance of indigenous people, boarded the ships of the East India Company and dumped £10,000 worth of tea from their holds (approximately £636,000 in 2008) into Boston Harbor. Decades later, this event became known as the

Boston Tea Party

The Boston Tea Party was an American political and mercantile protest by the Sons of Liberty in Boston, Massachusetts, on December 16, 1773. The target was the Tea Act of May 10, 1773, which allowed the British East India Company to sell t ...

and remains a significant part of American patriotic lore.

1774–1775: Intolerable Acts and the Quebec Act

The British government responded by passing several measures that came to be known as the

Intolerable Acts

The Intolerable Acts were a series of punitive laws passed by the British Parliament in 1774 after the Boston Tea Party. The laws aimed to punish Massachusetts colonists for their defiance in the Tea Party protest of the Tea Act, a tax measur ...

, further darkening colonial opinion towards England. They consisted of four laws enacted by the British parliament. The first was the

Massachusetts Government Act

The Massachusetts Government Act (14 Geo. 3 c. 45) was passed by the Parliament of Great Britain, receiving royal assent on 20 May 1774. The act effectively abrogated the 1691 charter of the Province of Massachusetts Bay and gave its royally-appo ...

which altered the Massachusetts charter and restricted town meetings. The second act was the

Administration of Justice Act

Administration of Justice Act (with its variations) is a stock short title used for legislation in the United Kingdom relating to the administration of justice.

The Bill for an Act with this short title may have been known as a Administration of J ...

which ordered that all British soldiers to be tried were to be arraigned in Britain, not in the colonies. The third Act was the

Boston Port Act, which closed the port of Boston until the British had been compensated for the tea lost in the Boston Tea Party. The fourth Act was the

Quartering Act of 1774, which allowed royal governors to house British troops in the homes of citizens without requiring permission of the owner.

In response, Massachusetts patriots issued the

Suffolk Resolves and formed an alternative shadow government known as the ''Provincial Congress'' which began training militia outside British-occupied Boston. In September 1774, the

First Continental Congress convened, consisting of representatives from each colony, to serve as a vehicle for deliberation and collective action. During secret debates, conservative

Joseph Galloway proposed the creation of a colonial Parliament that would be able to approve or disapprove acts of the British Parliament, but his idea was tabled in a vote of 6 to 5 and was subsequently removed from the record.

Congress called for a boycott beginning on 1 December 1774 of all British goods; it was enforced by new local committees authorized by the Congress.

Military hostilities begin

Massachusetts was declared in a state of rebellion in February 1775 and the British garrison received orders to disarm the rebels and arrest their leaders, leading to the

Battles of Lexington and Concord on 19 April 1775. The Patriots laid siege to Boston, expelled royal officials from all the colonies, and took control through the establishment of

Provincial Congresses. The

Battle of Bunker Hill followed on June 17, 1775. It was a British victory—but at a great cost: about 1,000 British casualties from a garrison of about 6,000, as compared to 500 American casualties from a much larger force. The

Second Continental Congress was divided on the best course of action, but eventually produced the

Olive Branch Petition, in which they attempted to come to an accord with

King George. The king, however, issued a

Proclamation of Rebellion

The Proclamation of Rebellion, officially titled A Proclamation for Suppressing Rebellion and Sedition, was the response of George III to the news of the Battle of Bunker Hill at the outset of the American Revolution. Issued on 23 August 1775, ...

which declared that the states were "in rebellion" and the members of Congress were traitors.

The war that arose was in some ways a classic

insurgency

An insurgency is a violent, armed rebellion against authority waged by small, lightly armed bands who practice guerrilla warfare from primarily rural base areas. The key descriptive feature of insurgency is its asymmetric nature: small irr ...

. As

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

wrote to

Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted exp ...

in October 1775:

In the winter of 1775, the Americans

invaded newly-British Quebec under generals

Benedict Arnold and

Richard Montgomery, expecting to rally sympathetic colonists there. The attack was a failure; many Americans who weren't killed were either captured or died of smallpox.

In March 1776, the Continental Army forced the British to

evacuate Boston, with George Washington as the commander of the new army. The revolutionaries now fully controlled all thirteen colonies and were ready to declare independence. There still were many Loyalists, but they were no longer in control anywhere by July 1776, and all of the Royal officials had fled.

Creating new state constitutions

Following the

Battle of Bunker Hill in June 1775, the Patriots had control of Massachusetts outside the Boston city limits, and the Loyalists suddenly found themselves on the defensive with no protection from the British army. In all 13 colonies, Patriots had overthrown their existing governments, closing courts and driving away British officials. They held elected conventions and "legislatures" that existed outside any legal framework; new constitutions were drawn up in each state to supersede royal charters. They proclaimed that they were now ''

states'', no longer ''

colonies

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state'' ...

''.

[Nevins (1927); Greene and Pole (1994) chapter 29]

On January 5, 1776,

New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec to the nor ...

ratified the first state constitution. In May 1776, Congress voted to suppress all forms of crown authority, to be replaced by locally created authority.

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

,

South Carolina

)'' Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, and New Jersey created their constitutions before July 4.

Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the smallest U.S. state by area and the seventh-least populous, with slightly fewer than 1.1 million residents as of 2020, but it ...

and

Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its capita ...

simply took their existing

royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but s ...

s and deleted all references to the crown. The new states were all committed to republicanism, with no inherited offices. They decided what form of government to create, and also how to select those who would craft the constitutions and how the resulting document would be ratified. On 26 May 1776,

John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before his presidency, he was a leader of t ...

wrote James Sullivan from Philadelphia warning against extending

the franchise

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

too far:

The resulting constitutions in states such as

Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, Virginia,

Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent Del ...

, New York, and

Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

featured:

* Property qualifications for voting and even more substantial requirements for elected positions (though New York and Maryland lowered property qualifications)

*

Bicameral legislatures, with the upper house as a check on the lower

* Strong

governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

s with veto power over the legislature and substantial appointment authority

* Few or no restraints on individuals holding multiple positions in government

* The continuation of

state-established religion

In Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New Hampshire, the resulting constitutions embodied:

* universal manhood suffrage, or minimal property requirements for voting or holding office (New Jersey enfranchised some property-owning widows, a step that it retracted 25 years later)

* strong,

unicameral legislatures

Unicameralism (from ''uni''- "one" + Latin ''camera'' "chamber") is a type of legislature, which consists of one house or assembly, that legislates and votes as one.

Unicameral legislatures exist when there is no widely perceived need for multi ...

* relatively weak governors without veto powers, and with little appointing authority

* prohibition against individuals holding multiple government posts

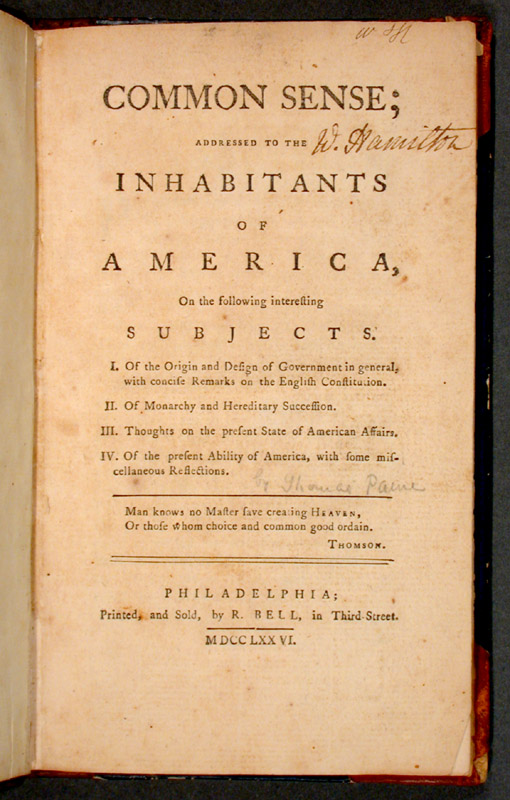

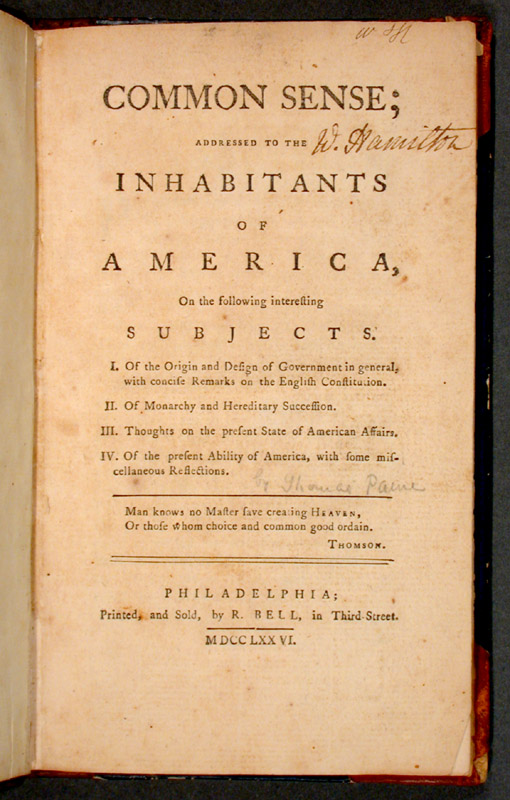

The radical provisions of Pennsylvania's constitution lasted only 14 years. In 1790, conservatives gained power in the state legislature, called a new constitutional convention, and rewrote the constitution. The new constitution substantially reduced universal male suffrage, gave the governor veto power and patronage appointment authority, and added an upper house with substantial wealth qualifications to the unicameral legislature. Thomas Paine called it a constitution unworthy of America.

Independence and Union

In April 1776, the

North Carolina Provincial Congress

The North Carolina Provincial Congresses were extra-legal unicameral legislative bodies formed in 1774 through 1776 by the people of the Province of North Carolina, independent of the British colonial government. There were five congresses. They ...

issued the

Halifax Resolves

The Halifax Resolves was a name later given to the resolution adopted by the North Carolina Provincial Congress on April 12, 1776. The adoption of the resolution was the first official action in the American Colonies calling for independence from ...

explicitly authorizing its delegates to vote for independence. By June, nine Provincial Congresses were ready for independence; one by one, the last four fell into line: Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and New York.

Richard Henry Lee

Richard Henry Lee (January 20, 1732June 19, 1794) was an American statesman and Founding Father from Virginia, best known for the June 1776 Lee Resolution, the motion in the Second Continental Congress calling for the colonies' independence f ...

was instructed by the Virginia legislature to propose independence, and he did so on June 7, 1776. On June 11, a committee was created by the Second Continental Congress to draft a document explaining the justifications for separation from Britain. After securing enough votes for passage, independence was voted for on July 2.

The

Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of th ...

was drafted largely by

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

and presented by the committee; it was unanimously adopted by the entire Congress on July 4, and each colony became an independent and autonomous

state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

. The next step was to form a

union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

to facilitate international relations and alliances.

The Second Continental Congress approved the

Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union was an agreement among the 13 Colonies of the United States of America that served as its first frame of government. It was approved after much debate (between July 1776 and November 1777) by ...

for ratification by the states on November 15, 1777; the Congress immediately began operating under the Articles' terms, providing a structure of

shared sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the person ...

during prosecution of the war and facilitating international relations and alliances with France and Spain. The Articles were fully ratified on March 1, 1781. At that point, the Continental Congress was dissolved and a new government of the

United States in Congress Assembled

The Congress of the Confederation, or the Confederation Congress, formally referred to as the United States in Congress Assembled, was the governing body of the United States of America during the Confederation period, March 1, 1781 – Mar ...

took its place on the following day, with

Samuel Huntington as presiding officer.

Defending the Revolution

British return: 1776–1777

According to British historian

Jeremy Black, the British had significant advantages, including a highly trained army, the world's largest navy, and an efficient system of public finance that could easily fund the war. However, they seriously misunderstood the depth of support for the American Patriot position and ignored the advice of General Gage, misinterpreting the situation as merely a large-scale riot. The British government believed that they could overawe the Americans by sending a large military and naval force, forcing them to be loyal again:

Washington forced the British out of Boston in the spring of 1776, and neither the British nor the Loyalists controlled any significant areas. The British, however, were massing forces at their naval base at

Halifax, Nova Scotia

Halifax is the capital and largest municipality of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the largest municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of the 2021 Census, the municipal population was 439,819, with 348 ...

. They returned in force in July 1776, landing in New York and defeating Washington's Continental Army in August at the

Battle of Brooklyn. Following that victory, they requested a meeting with representatives from Congress to negotiate an end to hostilities.

[Schecter, Barnet. ''The Battle for New York: The City at the Heart of the American Revolution''. (2002)][McCullough, ''1776'' (2005)]

A delegation including John Adams and Benjamin Franklin met British admiral

Richard Howe

Admiral of the Fleet Richard Howe, 1st Earl Howe, (8 March 1726 – 5 August 1799) was a British naval officer. After serving throughout the War of the Austrian Succession, he gained a reputation for his role in amphibious operations a ...

on

Staten Island in New York Harbor on September 11 in what became known as the

Staten Island Peace Conference. Howe demanded that the Americans retract the Declaration of Independence, which they refused to do, and negotiations ended. The British then

seized New York City and nearly captured Washington's army. They made the city and its strategic harbor their main political and military base of operations, holding it until

November 1783. The city became the destination for Loyalist refugees and a focal point of Washington's

intelligence network.

The British also took New Jersey, pushing the Continental Army into Pennsylvania. Washington

crossed the Delaware River back into New Jersey in a surprise attack in late December 1776 and defeated the

Hessian and British armies at

Trenton and

Princeton

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ni ...

, thereby regaining control of most of New Jersey. The victories gave an important boost to Patriots at a time when morale was flagging, and they have become iconic events of the war.

In 1777, the British sent Burgoyne's invasion force from Canada south to New York to seal off New England. Their aim was to isolate New England, which the British perceived as the primary source of agitation. Rather than move north to support Burgoyne, the British army in New York City went to Philadelphia in a major case of mis-coordination, capturing it from Washington. The invasion army under

Burgoyne was much too slow and became trapped in northern New York state. It surrendered after the

Battles of Saratoga in October 1777. From early October 1777 until November 15, a siege distracted British troops at

Fort Mifflin

Fort Mifflin, originally called Fort Island Battery and also known as Mud Island Fort, was commissioned in 1771 and sits on Mud Island (or Deep Water Island) on the Delaware River below Philadelphia, Pennsylvania near Philadelphia International A ...

, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and allowed Washington time to preserve the Continental Army by safely leading his troops to harsh winter quarters at

Valley Forge

Valley Forge functioned as the third of eight winter encampments for the Continental Army's main body, commanded by General George Washington, during the American Revolutionary War. In September 1777, Congress fled Philadelphia to escape the ...

.

Prisoners

On August 23, 1775, George III declared Americans to be traitors to the Crown if they took up arms against royal authority. There were thousands of British and Hessian soldiers in American hands following their surrender at the Battles of Saratoga. Lord Germain took a hard line, but the British generals on American soil never held treason trials, and instead treated captured American soldiers as prisoners of war. The dilemma was that tens of thousands of Loyalists were under American control and American retaliation would have been easy. The British built much of their strategy around using these Loyalists.

[Larry G. Bowman, ''Captive Americans: Prisoners During the American Revolution'' (1976)] The British maltreated the prisoners whom they held, resulting in more deaths to American prisoners of war than from combat operations.

At the end of the war, both sides released their surviving prisoners.

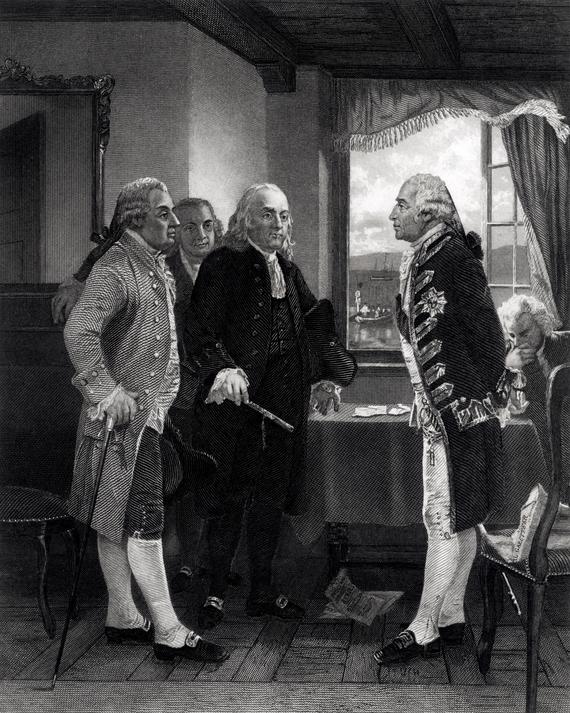

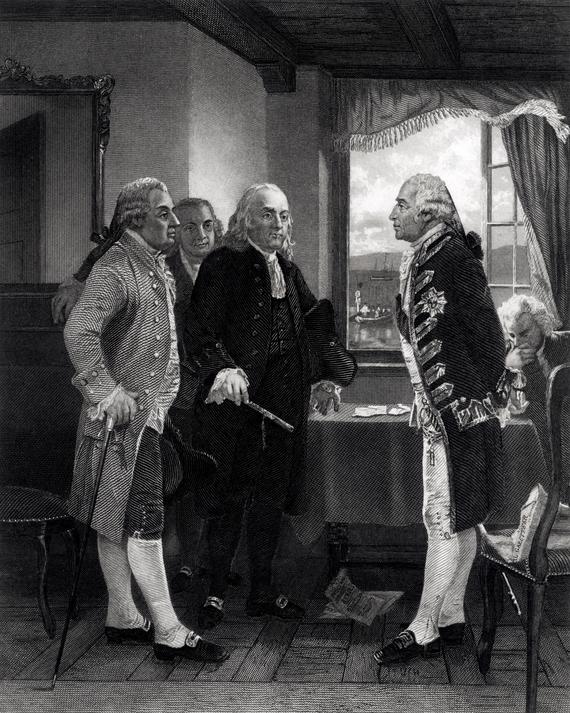

American alliances after 1778

The capture of a British army at Saratoga encouraged the French to formally enter the war in support of Congress, and Benjamin Franklin negotiated a permanent military alliance in early 1778; France thus became the first foreign nation to officially recognize the Declaration of Independence. On February 6, 1778, the United States and France signed the

Treaty of Amity and Commerce and the

Treaty of Alliance.

[Hamilton, ''The Papers of Alexander Hamilton'' (1974) p. 28] William Pitt spoke out in Parliament urging Britain to make peace in America and to unite with America against France, while British politicians who had sympathized with colonial grievances now turned against the Americans for allying with Britain's rival and enemy.

The Spanish and the Dutch became allies of the French in 1779 and 1780 respectively, forcing the British to fight a global war without major allies, and requiring it to slip through a combined blockade of the Atlantic. Britain began to view the American war for independence as merely one front in a wider war, and the British chose to withdraw troops from America to reinforce the British colonies in the Caribbean, which were under threat of Spanish or French invasion. British commander Sir

Henry Clinton evacuated Philadelphia and returned to New York City. General Washington intercepted him in the

Battle of Monmouth Court House, the last major battle fought in the north. After an inconclusive engagement, the British retreated to New York City. The northern war subsequently became a stalemate, as the focus of attention shifted to the smaller southern theater.

[Higginbotham, ''The War of American Independence'' (1983) p. 83]

The British move South, 1778–1783

The British strategy in America now concentrated on a campaign in the southern states. With fewer regular troops at their disposal, the British commanders saw the "southern strategy" as a more viable plan, as they perceived the south as strongly Loyalist with a large population of recent immigrants and large numbers of slaves who might be tempted to run away from their masters to join the British and gain their freedom.

Beginning in late December 1778, the British captured

Savannah and controlled the

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

coastline. In 1780, they launched a fresh invasion and

took Charleston, as well. A significant victory at the

Battle of Camden meant that royal forces soon controlled most of Georgia and South Carolina. The British set up a network of forts inland, hoping that the Loyalists would rally to the flag.

[Henry Lumpkin, ''From Savannah to Yorktown: The American Revolution in the South'' (2000)] Not enough Loyalists turned out, however, and the British had to fight their way north into North Carolina and Virginia with a severely weakened army. Behind them, much of the territory that they had already captured dissolved into a chaotic

guerrilla war

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run tactics ...

, fought predominantly between bands of Loyalists and American militia, and which negated many of the gains that the British had previously made.

Surrender at Yorktown (1781)

The British army under Cornwallis marched to

Yorktown, Virginia

Yorktown is a census-designated place (CDP) in York County, Virginia. It is the county seat of York County, one of the eight original shires formed in colonial Virginia in 1682. Yorktown's population was 195 as of the 2010 census, while York Co ...

, where they expected to be rescued by a British fleet. The fleet did arrive, but so did a larger French fleet. The French were victorious in the

Battle of the Chesapeake

The Battle of the Chesapeake, also known as the Battle of the Virginia Capes or simply the Battle of the Capes, was a crucial naval battle in the American Revolutionary War that took place near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay on 5 September 17 ...

, and the British fleet returned to New York for reinforcements, leaving Cornwallis trapped. In October 1781, the British surrendered their second invading army of the war under a siege by the combined French and Continental armies commanded by Washington.

The end of the war

Washington did not know if or when the British might reopen hostilities after Yorktown. They still had 26,000 troops occupying New York City, Charleston, and Savannah, together with a powerful fleet. The French army and navy departed, so the Americans were on their own in 1782–83. The American treasury was empty, and the unpaid soldiers were growing restive, almost to the point of mutiny or possible

coup d'etat. Washington dispelled the unrest among officers of the

Newburgh Conspiracy

The Newburgh Conspiracy was a failed apparent threat by leaders of the Continental Army in March 1783, at the end of the American Revolutionary War. The Army's commander, George Washington, successfully calmed the soldiers and helped secure back ...

in 1783, and Congress subsequently created the promise of a five years bonus for all officers.

Historians continue to debate whether the odds were long or short for American victory.

John E. Ferling says that the odds were so long that the American victory was "almost a miracle". On the other hand,

Joseph Ellis

Joseph John-Michael Ellis III (born July 18, 1943) is an American historian whose work focuses on the lives and times of the founders of the United States of America. '' American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson'' won a National Boo ...

says that the odds favored the Americans, and asks whether there ever was any realistic chance for the British to win. He argues that this opportunity came only once, in the summer of 1776, and the British failed that test. Admiral Howe and his brother General Howe "missed several opportunities to destroy the Continental Army .... Chance, luck, and even the vagaries of the weather played crucial roles." Ellis's point is that the strategic and tactical decisions of the Howes were fatally flawed because they underestimated the challenges posed by the Patriots. Ellis concludes that, once the Howe brothers failed, the opportunity "would never come again" for a British victory.

Support for the conflict had never been strong in Britain, where many sympathized with the Americans, but now it reached a new low. King George wanted to fight on, but his supporters lost control of Parliament and they launched no further offensives in America on the eastern seaboard.

However, the British continued formal and informal assistance to Indian tribes making war on US citizens over the next three decades, which contributed to a "Second American Revolution" in the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...