Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national

constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions. ...

in

Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

between 1867 and 1918. A military and diplomatic alliance, it consisted of two sovereign states with a single monarch who was titled both the

Emperor of Austria

The emperor of Austria (, ) was the ruler of the Austrian Empire and later the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The hereditary imperial title and office was proclaimed in 1804 by Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor, a member of the House of Habsburg-Lorr ...

and the

King of Hungary

The King of Hungary () was the Monarchy, ruling head of state of the Kingdom of Hungary from 1000 (or 1001) to 1918. The style of title "Apostolic King of Hungary" (''Magyarország apostoli királya'') was endorsed by Pope Clement XIII in 1758 ...

. Austria-Hungary constituted the last phase in the constitutional evolution of the

Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy, also known as Habsburg Empire, or Habsburg Realm (), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities (composite monarchy) that were ruled by the House of Habsburg. From the 18th century it is ...

: it was formed with the

Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 (, ) established the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary, which was a military and diplomatic alliance of two sovereign states. The Compromise only partially re-established the former pre-1848 sovereign ...

in the aftermath of the

Austro-Prussian War

The Austro-Prussian War (German: ''Preußisch-Österreichischer Krieg''), also known by many other names,Seven Weeks' War, German Civil War, Second War of Unification, Brothers War or Fraternal War, known in Germany as ("German War"), ''Deutsc ...

, following wars of independence by Hungary in opposition to Habsburg rule. It was dissolved shortly after

Hungary terminated the union with Austria in 1918 at the end of World War 1.

One of Europe's major powers, Austria-Hungary was geographically the second-largest country in Europe (after

Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

) and the third-most populous (after

Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

and the

German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

), while being among the 10 most populous countries worldwide. The Empire built up the fourth-largest machine-building industry in the world. With the exception of the territory of the

Bosnian Condominium, the Empire of Austria and the Kingdom of Hungary were separate sovereign countries in international law.

At its core was the

dual monarchy, which was a

real union

Real union is a union of two or more states, which share some state institutions in contrast to personal unions; however, they are not as unified as states in a political union. It is a development from personal union and has historically been ...

between

Cisleithania

Cisleithania, officially The Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council (), was the northern and western part of Austria-Hungary, the Dual Monarchy created in the Compromise of 1867—as distinguished from ''Transleithania'' (i.e., ...

, the northern and western parts of the former

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

, and

Transleithania (Kingdom of Hungary). Following the 1867 reforms, the Austrian and Hungarian states were co-equal in power. The two countries conducted unified diplomatic and defence policies. For these purposes, "common" ministries of foreign affairs and defence were maintained under the monarch's direct authority, as was a third finance ministry responsible only for financing the two "common" portfolios. A third component of the union was the

Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia

The Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia (; or ; ) was a nominally autonomous kingdom and constitutionally defined separate political nation within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It was created in 1868 by merging the kingdoms of Kingdom of Croatia (Habs ...

, an autonomous region under the Hungarian crown, which negotiated the

Croatian–Hungarian Settlement

The Croatian–Hungarian Settlement (; ; ) was a pact signed in 1868 that governed Croatia's political status in the Hungarian-ruled part of Austria-Hungary. It lasted until the end of World War I, when the Croatian Parliament, as the representati ...

in 1868. After 1878,

Bosnia and Herzegovina came under Austro-Hungarian joint military and civilian rule until it was fully annexed in 1908, provoking the

Bosnian crisis

The Bosnian Crisis, also known as the Annexation Crisis (, ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, Aneksiona kriza, Анексиона криза) or the First Balkan Crisis, erupted on 5 October 1908 when Austria-Hungary announced the annexation of Bosnia and Herzeg ...

.

["]

Austria-Hungary was one of the

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,; ; , ; were one of the two main coalitions that fought in World War I (1914–1918). It consisted of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulga ...

in

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, which began with an Austro-Hungarian war declaration on the

Kingdom of Serbia

The Kingdom of Serbia was a country located in the Balkans which was created when the ruler of the Principality of Serbia, Milan I of Serbia, Milan I, was proclaimed king in 1882. Since 1817, the Principality was ruled by the Obrenović dynast ...

on 28 July 1914. It was already effectively

dissolved by the time the military authorities signed the

armistice of Villa Giusti

The Armistice of Villa Giusti or Padua Armistice was an armistice convention with Austria-Hungary which de facto ended warfare between Allies and Associated Powers and Austria-Hungary during World War I. Italy represented the Allies and Associat ...

on 3 November 1918. The

Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from 1000 to 1946 and was a key part of the Habsburg monarchy from 1526-1918. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coro ...

and the

First Austrian Republic

The First Austrian Republic (), officially the Republic of Austria, was created after the signing of the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye on 10 September 1919—the settlement after the end of World War I which ended the Habsburg rump state of ...

were treated as its

successors ''de jure'', whereas the independence of the

First Czechoslovak Republic

The First Czechoslovak Republic, often colloquially referred to as the First Republic, was the first Czechoslovakia, Czechoslovak state that existed from 1918 to 1938, a union of ethnic Czechs and Slovaks. The country was commonly called Czechosl ...

, the

Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 7 October 1918 and 6 October 1939. The state was established in the final stage of World War I ...

, and the

Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a country in Southeast Europe, Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 until 1941. From 1918 to 1929, it was officially called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, but the term "Yugoslavia" () h ...

, respectively, and most of the territorial demands of the

Kingdom of Romania

The Kingdom of Romania () was a constitutional monarchy that existed from with the crowning of prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen as King of Romania, King Carol I of Romania, Carol I (thus beginning the Romanian royal family), until 1947 wit ...

and the

Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

were also recognized by the victorious powers in 1920.

Name and terminology

The realm's official name was the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy (, ; , ), though in international relations ''Austria–Hungary'' was used (; ). The Austrians also used the names () (in detail ; ) and ''Danubian Monarchy'' (; ) or ''Dual Monarchy'' (; ) and ''The Double Eagle'' (; ), but none of these became widespread either in Hungary or elsewhere.

The realm's full name used in internal administration was

The Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council and the

Lands of the Holy Hungarian Crown of St. Stephen.

*

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

:

*

Hungarian:

From 1867 onwards, the abbreviations heading the names of official institutions in Austria–Hungary reflected their responsibility:

* (' or

Imperial and Royal

The phrase Imperial and Royal (, ) refers to the court/government of the Habsburgs in a broader historical perspective. Some modern authors restrict its use to the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary from 1867 to 1918.

During that period, it in ...

) was the label for institutions common to both parts of the monarchy, e.g., the ' (Navy) and, during the war, the ' (Army). The common army changed its label from ' to ' only in 1889 at the request of the Hungarian government.

* ' (') or

Imperial-Royal was the term for institutions of

Cisleithania

Cisleithania, officially The Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council (), was the northern and western part of Austria-Hungary, the Dual Monarchy created in the Compromise of 1867—as distinguished from ''Transleithania'' (i.e., ...

(Austria); "royal" in this label referred to the

Crown of Bohemia

The Lands of the Bohemian Crown were the states in Central Europe during the medieval and early modern periods with feudal obligations to the Bohemian kings. The crown lands primarily consisted of the Kingdom of Bohemia, an electorate of the Hol ...

.

* ' (') or ' (') ("Royal Hungarian") referred to

Transleithania

The Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen (), informally Transleithania (meaning the lands or region "beyond" the Leitha River), were the Hungarian territories of Austria-Hungary, throughout the latter's entire existence (30 March 1867 – 16 ...

, the lands of the Hungarian crown. In the

Kingdom of Croatia and Slavonia

The Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia (; or ; ) was a nominally autonomous kingdom and constitutionally defined separate political nation within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It was created in 1868 by merging the kingdoms of Croatia and Slavonia fol ...

, the autonomous institutions used ''k.'' (') ("Royal"), since according to the

Croatian–Hungarian Settlement

The Croatian–Hungarian Settlement (; ; ) was a pact signed in 1868 that governed Croatia's political status in the Hungarian-ruled part of Austria-Hungary. It lasted until the end of World War I, when the Croatian Parliament, as the representati ...

, the only official language in Croatia and Slavonia was

Croatian, and the institutions were "only" Croatian.

Following a decision of Franz Joseph I in 1868, the realm bore the official name Austro-Hungarian Monarchy/Realm (; ) in its international relations. It was often contracted to the "Dual Monarchy" in English or simply referred to as ''Austria''.

Background and establishment

Following Hungary's defeat against the Ottoman Empire in the

Battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács (; , ) took place on 29 August 1526 near Mohács, in the Kingdom of Hungary. It was fought between the forces of Hungary, led by King Louis II of Hungary, Louis II, and the invading Ottoman Empire, commanded by Suleima ...

of 1526, the Habsburg Empire became more involved in the Kingdom of Hungary, and subsequently assumed the Hungarian throne. However, as the Ottomans expanded further into Hungary, the Habsburgs came to control only a small north-western portion of the former kingdom's territory. Eventually, following the

Treaty of Passarowitz

The Treaty of Passarowitz, or Treaty of Požarevac, was the peace treaty signed in Požarevac ( sr-cyr, Пожаревац, , ), a town that was in the Ottoman Empire but is now in Serbia, on 21 July 1718 between the Ottoman Empire and its ad ...

in 1718, all former territories of the Hungarian kingdom were ceded from the Ottomans to the Habsburgs. In the

revolutions of 1848

The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespre ...

, the Kingdom of Hungary called for greater self-government and later even independence from the

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

. The ensuing

Hungarian Revolution of 1848

The Hungarian Revolution of 1848, also known in Hungary as Hungarian Revolution and War of Independence of 1848–1849 () was one of many Revolutions of 1848, European Revolutions of 1848 and was closely linked to other revolutions of 1848 in ...

was crushed by the Austrian military with

Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

military assistance, and the level of autonomy that the Hungarian state had enjoyed was replaced with absolutist rule from Vienna.

This further increased Hungarian resentment of the Habsburg dominion.

In the 1860s, the Empire faced two severe defeats: its loss in the

Second Italian War of Independence

The Second Italian War of Independence, also called the Sardinian War, the Austro-Sardinian War, the Franco-Austrian War, or the Italian War of 1859 (Italian: ''Seconda guerra d'indipendenza italiana''; German: ''Sardinischer Krieg''; French: ...

broke its dominion over a large part of Northern Italy (

Lombardy, Veneto,

Modena, Reggio,

Tuscany

Tuscany ( ; ) is a Regions of Italy, region in central Italy with an area of about and a population of 3,660,834 inhabitants as of 2025. The capital city is Florence.

Tuscany is known for its landscapes, history, artistic legacy, and its in ...

,

Parma and Piacenza) while defeat in the

Austro-Prussian War

The Austro-Prussian War (German: ''Preußisch-Österreichischer Krieg''), also known by many other names,Seven Weeks' War, German Civil War, Second War of Unification, Brothers War or Fraternal War, known in Germany as ("German War"), ''Deutsc ...

of 1866 led to the dissolution of the

German Confederation

The German Confederation ( ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, which had been dissolved ...

(of which the Habsburg emperor was the hereditary president) and the exclusion of Austria from German affairs. These twin defeats gave the Hungarians the opportunity to remove the shackles of absolutist rule.

Realizing the need to compromise with Hungary in order to retain its great power status, the central government in Vienna began negotiations with the Hungarian political leaders, led by

Ferenc Deák. The Hungarians maintained that the

April Laws

The April Laws, also called March Laws, were a collection of laws legislated by Lajos Kossuth with the aim of modernizing the Kingdom of Hungary into a parliamentary democracy, nation state. The laws were passed by the Hungarian Diet in March 1 ...

were still valid, but conceded that under the

Pragmatic Sanction of 1713

The Pragmatic Sanction of 1713 (; ) was an edict issued by Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI, on 19 April 1713 to ensure that the Habsburg monarchy, which included the Archduchy of Austria, the Kingdom of Hungary, the Kingdom of Croatia, the Kin ...

, foreign affairs and defence were "common" to Austria and Hungary. On 20 March 1867, the newly

re-established Hungarian parliament at

Pest started to negotiate the new laws to be accepted on 30 March. However, Hungarian leaders received word that the Emperor's formal coronation as King of Hungary on 8 June had to have taken place in order for the laws to be enacted within the lands of the

Holy Crown of Hungary

The Holy Crown of Hungary ( , ), also known as the Crown of Saint Stephen, named in honour of Saint Stephen I of Hungary, was the coronation crown used by the Kingdom of Hungary for most of its existence; kings were crowned with it since the tw ...

.

On 28 July, Franz Joseph, in his new capacity as King of Hungary, approved and promulgated the new laws, which officially gave birth to the Dual Monarchy.

1866–1878: beyond Lesser Germany

The

Austro-Prussian War

The Austro-Prussian War (German: ''Preußisch-Österreichischer Krieg''), also known by many other names,Seven Weeks' War, German Civil War, Second War of Unification, Brothers War or Fraternal War, known in Germany as ("German War"), ''Deutsc ...

was ended by the

Peace of Prague (1866)

The Peace of Prague () was a peace treaty signed by the Kingdom of Prussia and the Austrian Empire at Prague on 23 August 1866. In combination with the treaties of Prussia and several south - and central German states it effectively ended the Au ...

which settled the "

German question" in favor of a

Lesser German Solution.

Count Friedrich Ferdinand von Beust

Count Friedrich Ferdinand von Beust (; 13 January 1809 – 24 October 1886) was a German and Austrian statesman. As an opponent of Otto von Bismarck, he attempted to conclude a common policy of the German middle states between Austria and Pruss ...

, who was the foreign minister from 1866 to 1871, hated the Prussian chancellor,

Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (; born ''Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck''; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a German statesman and diplomat who oversaw the unification of Germany and served as ...

, who had repeatedly outmaneuvered him. Beust looked to France for avenging Austria's defeat and attempted to negotiate with Emperor

Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

of France and Italy for an anti-Prussian alliance, but no terms could be reached. The decisive victory of the Prusso-German armies in the

Franco-Prussian war

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

and the subsequent founding of the German Empire ended all hope of re-establishing Austrian influence in Germany, and Beust retired.

After being forced out of Germany and Italy, the Dual Monarchy turned to the Balkans, which were in tumult as nationalistic movements were gaining strength and demanding independence. Both Russia and Austria–Hungary saw an opportunity to expand in this region. Russia took on the role of protector of Slavs and Orthodox Christians. Austria envisioned a multi-ethnic, religiously diverse empire under Vienna's control. Count Gyula Andrássy, a Hungarian who was Foreign Minister (1871–1879), made the centerpiece of his policy one of opposition to Russian expansion in the Balkans and blocking Serbian ambitions to dominate a new South Slav federation. He wanted Germany to ally with Austria, not Russia.

Government

The

Compromise of 1867

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 (, ) established the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary, which was a military and diplomatic alliance of two sovereign states. The Compromise only partially re-established the former pre-1848 sovereign ...

turned the

Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

domains into a

real union

Real union is a union of two or more states, which share some state institutions in contrast to personal unions; however, they are not as unified as states in a political union. It is a development from personal union and has historically been ...

between the

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

("Lands Represented in the Imperial Council", or

Cisleithania

Cisleithania, officially The Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council (), was the northern and western part of Austria-Hungary, the Dual Monarchy created in the Compromise of 1867—as distinguished from ''Transleithania'' (i.e., ...

)

[ in the western and northern half and the ]Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from 1000 to 1946 and was a key part of the Habsburg monarchy from 1526-1918. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coro ...

("Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen", or Transleithania

The Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen (), informally Transleithania (meaning the lands or region "beyond" the Leitha River), were the Hungarian territories of Austria-Hungary, throughout the latter's entire existence (30 March 1867 – 16 ...

) in the eastern half.[

The government of Austria, which had ruled the monarchy until 1867, became the government of the Austrian part, and another government was formed for the Hungarian part. The common government (officially designated Ministerial Council for Common Affairs, or in German) formed for the few matters of common national security - the ]Common Army

The Common Army (, ) as it was officially designated by the Imperial and Royal Military Administration, was the largest part of the Austro-Hungarian land forces from 1867 to 1914, the other two elements being the Imperial-Royal Landwehr (of Au ...

, Navy

A navy, naval force, military maritime fleet, war navy, or maritime force is the military branch, branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval warfare, naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral z ...

, foreign policy and the imperial household, and the customs union.[

Hungary and Austria maintained separate ]parliaments

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. T ...

, each with its own prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

: the Diet of Hungary

The Diet of Hungary or originally: Parlamentum Publicum / Parlamentum Generale () was the most important political assembly in Hungary since the 12th century, which emerged to the position of the supreme legislative institution in the Kingdom ...

(commonly known as the National Assembly) and the Imperial Council () in Cisleithania. Each parliament had its own executive government, appointed by the monarch.Bosnian crisis

The Bosnian Crisis, also known as the Annexation Crisis (, ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, Aneksiona kriza, Анексиона криза) or the First Balkan Crisis, erupted on 5 October 1908 when Austria-Hungary announced the annexation of Bosnia and Herzeg ...

with the Great Powers and Austria-Hungary's Balkan neighbors, Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

and Montenegro

, image_flag = Flag of Montenegro.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Montenegro.svg

, coa_size = 80

, national_motto =

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map = Europe-Mont ...

.[

Relations during the half-century after 1867 between the two parts of the dual monarchy featured repeated disputes over shared external tariff arrangements and over the financial contribution of each government to the common treasury. These matters were determined by the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, in which common expenditures were allocated 70% to Austria and 30% to Hungary. This division had to be renegotiated every ten years. There was political turmoil during the build-up to each renewal of the agreement. By 1907, the Hungarian share had risen to 36.4%.]constitutional crisis

In political science, a constitutional crisis is a problem or conflict in the function of a government that the constitution, political constitution or other fundamental governing law is perceived to be unable to resolve. There are several variat ...

. It was triggered by disagreement over which language to use for command in Hungarian army

The Hungarian Ground Forces (, ) constitute the land branch of the Hungarian Defence Forces, responsible for ground activities and troops, including artillery, tanks, Armoured Personnel Carriers (APCs), Infantry Fighting Vehicles (IFVs), and g ...

units and deepened by the advent to power in Budapest in April 1906 of a Hungarian nationalist coalition. Provisional renewals of the common arrangements occurred in October 1907 and in November 1917 on the basis of the ''status quo''. The negotiations in 1917 ended with the dissolution of the Dual Monarchy.

Demographics

In July 1849, the Hungarian Revolutionary Parliament proclaimed and enacted ethnic and minority rights (the next such laws were in Switzerland), but these were overturned after the Russian and Austrian armies crushed the Hungarian Revolution. After the Kingdom of Hungary reached the Compromise with the Habsburg Dynasty in 1867, one of the first acts of its restored Parliament was to pass a Law on Nationalities (Act Number XLIV of 1868). It was a liberal piece of legislation and offered extensive language and cultural rights. It did not recognize non-Hungarians to have rights to form states with any territorial autonomy.

Article 19 of the 1867 "Basic State Act" (''Staatsgrundgesetz''), valid only for the Cisleithanian (Austrian) part of Austria–Hungary, said:

The implementation of this principle led to several disputes, as it was not clear which languages could be regarded as "customary". The Germans, the traditional bureaucratic, capitalist and cultural elite, demanded the recognition of their language as a customary language in every part of the empire. German nationalists, especially in the

In July 1849, the Hungarian Revolutionary Parliament proclaimed and enacted ethnic and minority rights (the next such laws were in Switzerland), but these were overturned after the Russian and Austrian armies crushed the Hungarian Revolution. After the Kingdom of Hungary reached the Compromise with the Habsburg Dynasty in 1867, one of the first acts of its restored Parliament was to pass a Law on Nationalities (Act Number XLIV of 1868). It was a liberal piece of legislation and offered extensive language and cultural rights. It did not recognize non-Hungarians to have rights to form states with any territorial autonomy.

Article 19 of the 1867 "Basic State Act" (''Staatsgrundgesetz''), valid only for the Cisleithanian (Austrian) part of Austria–Hungary, said:

The implementation of this principle led to several disputes, as it was not clear which languages could be regarded as "customary". The Germans, the traditional bureaucratic, capitalist and cultural elite, demanded the recognition of their language as a customary language in every part of the empire. German nationalists, especially in the Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and ) is a German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the border districts of Bohe ...

(part of Bohemia), looked to Berlin in the new German Empire.

The Hungarian Minority Act of 1868 gave the minorities (Slovaks, Romanians, Serbs, et al.) individual (but not also communal) rights to use their language in offices, schools (although in practice often only in those founded by them and not by the state), courts and municipalities (if 20% of the deputies demanded it). Beginning with the 1879 Primary Education Act and the 1883 Secondary Education Act, the Hungarian state made more efforts to reduce the use of non-Magyar languages, in strong violation of the 1868 Nationalities Law. After 1875, all Slovak language schools higher than elementary were closed, including the only three high schools (gymnasiums) in Revúca

Revúca (; formerly ''Veľká Revúca'' in Slovak; ; ) is a town in Banská Bystrica Region, Slovakia. Revúca is the seat of Revúca District.

Etymology

The name is of Slovak origin and was initially the name of Revúca Creek (literally, 'roa ...

(Nagyrőce), Turčiansky Svätý Martin (Turócszentmárton) and Kláštor pod Znievom

Kláštor pod Znievom (, ) is a village and municipality in Martin District in the Žilina Region of northern Slovakia, south west from Martin, near the Malá Fatra mountains.

History

In historical records the village was first mentioned in 111 ...

(Znióváralja).

Language was, as a proxy for ethnicity, one of the most contentious issues in Austro-Hungarian politics. All governments faced difficult and divisive hurdles in deciding on the languages of government and of instruction. The minorities sought the widest opportunities for education in their own languages, as well as in the "dominant" languages—Hungarian and German. By the "Ordinance of 5 April 1897", the Austrian Prime Minister Count Kasimir Felix Badeni

Count Kasimir Felix Badeni ( German: ''Kasimir Felix Graf von Badeni'', Polish: ''Kazimierz Feliks hrabia Badeni''; 14 October 1846 – 9 July 1909), a member of the Polish noble House of Badeni, was an Austrian statesman, who served as Minist ...

gave Czech equal standing with German in the internal government of Bohemia; this led to a crisis because of nationalist German agitation throughout the empire. The Crown dismissed Badeni.

Italian was regarded as an old "culture language" (') by German intellectuals and had always been granted equal rights as an

Italian was regarded as an old "culture language" (') by German intellectuals and had always been granted equal rights as an official language

An official language is defined by the Cambridge English Dictionary as, "the language or one of the languages that is accepted by a country's government, is taught in schools, used in the courts of law, etc." Depending on the decree, establishmen ...

of the Empire, but the Germans had difficulty in accepting the Slavic languages

The Slavic languages, also known as the Slavonic languages, are Indo-European languages spoken primarily by the Slavs, Slavic peoples and their descendants. They are thought to descend from a proto-language called Proto-Slavic language, Proto- ...

as equal to their own. On one occasion Count A. Auersperg (Anastasius Grün) entered the Diet of Carniola

Carniola ( ; ; ; ) is a historical region that comprised parts of present-day Slovenia. Although as a whole it does not exist anymore, Slovenes living within the former borders of the region still tend to identify with its traditional parts Upp ...

carrying what he claimed to be the whole corpus

Corpus (plural ''corpora'') is Latin for "body". It may refer to:

Linguistics

* Text corpus, in linguistics, a large and structured set of texts

* Speech corpus, in linguistics, a large set of speech audio files

* Corpus linguistics, a branch of ...

of Slovene literature

Slovene literature is the literature written in Slovene. It spans across all literary genres with historically the Slovene historical fiction as the most widespread Slovene fiction genre. The Romantic 19th-century epic poetry written by the ...

under his arm; this was to demonstrate that the Slovene language

Slovene ( or ) or Slovenian ( ; ) is a South Slavic languages, South Slavic language of the Balto-Slavic languages, Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages, Indo-European language family. Most of its 2.5 million speakers are the ...

could not be substituted for German as the language of higher education.

The following years saw official recognition of several languages, at least in Austria. Since 1867, laws awarded Croatian equal status with Italian in Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

. Beginning in 1882, there was a Slovene majority in the Diet of Carniola and in the capital Laibach (Ljubljana); they replaced German with Slovene as their primary official language. Galicia designated Polish instead of German in 1869 as the customary language of government.

As of June 1907, all public and private school

A private school or independent school is a school not administered or funded by the government, unlike a State school, public school. Private schools are schools that are not dependent upon national or local government to finance their fina ...

s in Hungary were obliged to ensure that after the fourth grade, the pupils could express themselves fluently in Hungarian. This led to the further closing of minority schools, devoted mostly to the Slovak and Rusyn languages. The two kingdoms sometimes divided their spheres of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military, or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal a ...

. According to Misha Glenny

Michael V. E. "Misha" Glenny (born 25 April 1958) is an English journalist and Television presenter, broadcaster, specialising in southeast Europe, global organised crime, and cybersecurity. He has been Rector of the Institute for Human Science ...

in his book, ''The Balkans, 1804–1999'', the Austrians responded to Hungarian support of Czechs by supporting the Croatian national movement in Zagreb. In recognition that he reigned in a multi-ethnic country, Emperor Franz Joseph spoke (and used) German, Hungarian and Czech fluently, and Croatian, Serbian, Polish and Italian to some degree.

The language disputes were most fiercely fought in Bohemia, where the Czech speakers formed a majority and sought equal status for their language to German. The Czechs

The Czechs (, ; singular Czech, masculine: ''Čech'' , singular feminine: ''Češka'' ), or the Czech people (), are a West Slavs, West Slavic ethnic group and a nation native to the Czech Republic in Central Europe, who share a common Bohemia ...

had lived primarily in Bohemia since the 6th century and German immigrants had begun settling the Bohemian periphery in the 13th century. The constitution of 1627 made the German language a second official language and equal to Czech. German speakers lost their majority in the Bohemian Diet in 1880 and became a minority to Czech speakers in the cities of Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

and Pilsen (while retaining a slight numerical majority in the city of Brno (Brünn)). The old Charles University in Prague

Charles University (CUNI; , UK; ; ), or historically as the University of Prague (), is the largest university in the Czech Republic. It is one of the oldest universities in the world in continuous operation, the oldest university north of the ...

, hitherto dominated by German speakers, was divided into German and Czech-speaking faculties in 1882.

At the same time, Hungarian dominance faced challenges from the local majorities of Romanians

Romanians (, ; dated Endonym and exonym, exonym ''Vlachs'') are a Romance languages, Romance-speaking ethnic group and nation native to Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. Sharing a Culture of Romania, ...

in Transylvania

Transylvania ( or ; ; or ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjen'') is a List of historical regions of Central Europe, historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and ...

and in the eastern Banat

Banat ( , ; ; ; ) is a geographical and Historical regions of Central Europe, historical region located in the Pannonian Basin that straddles Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe. It is divided among three countries: the eastern part lie ...

, Slovaks

The Slovaks ( (historical Sloveni ), singular: ''Slovák'' (historical: ''Sloven'' ), feminine: ''Slovenka'' , plural: ''Slovenky'') are a West Slavic ethnic group and nation native to Slovakia who share a common ancestry, culture, history ...

in Slovakia

Slovakia, officially the Slovak Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the west, and the Czech Republic to the northwest. Slovakia's m ...

, and Croats

The Croats (; , ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and other neighboring countries in Central Europe, Central and Southeastern Europe who share a common Croatian Cultural heritage, ancest ...

and Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Southeastern Europe who share a common Serbian Cultural heritage, ancestry, Culture of Serbia, culture, History of Serbia, history, and Serbian lan ...

in the crown lands of Croatia

Croatia, officially the Republic of Croatia, is a country in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herze ...

and of Dalmatia (modern Croatia), in Bosnia and Herzegovina and in the provinces known as the Vojvodina

Vojvodina ( ; sr-Cyrl, Војводина, ), officially the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, is an Autonomous administrative division, autonomous province that occupies the northernmost part of Serbia, located in Central Europe. It lies withi ...

(northern Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

). The Romanians and the Serbs began to agitate for union with their fellow nationalists and language speakers in the newly founded states of Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

(1859–1878) and Serbia.

Hungary's leaders were generally less willing than their Austrian counterparts to share power with their subject minorities, but they granted a large measure of autonomy to Croatia in 1868. To some extent, they modeled their relationship to that kingdom on their own compromise with Austria of the previous year. In spite of nominal autonomy, the Croatian government was an economic and administrative part of Hungary, which the Croatians resented. In the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia

The Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia (; or ; ) was a nominally autonomous kingdom and constitutionally defined separate political nation within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It was created in 1868 by merging the kingdoms of Kingdom of Croatia (Habs ...

and Bosnia and Herzegovina many advocated the idea of a trialist Austro-Hungaro-Croatian monarchy; among the supporters of the idea were Archduke Leopold Salvator, Archduke Franz Ferdinand and emperor and king Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

who during his short reign supported the trialist idea only to be vetoed by the Hungarian government and Count István Tisza

Count István Imre Lajos Pál Tisza de Borosjenő et Szeged (, English: Stephen Emery Louis Paul Tisza, short name: Stephen Tisza); (22 April 1861 – 31 October 1918) was a politician who served as Prime Minister of Hungary, prime minister ...

. The count finally signed the trialist proclamation after heavy pressure from the king on 23 October 1918.[ Budisavljević, Srđan, ''Stvaranje-Države-SHS, Creation of the state of SHS'', Zagreb, 1958, p. 132–133.]

Ethnic relations

In Margraviate of Istria, Istria, the Istro-Romanians, a small ethnic group composed by around 2,600 people in the 1880s, suffered severe discrimination. The Croats of the region, who formed the majority, tried to assimilate them, while the Italian minority supported them in their requests for self-determination. In 1888, the possibility of opening the first school for the Istro-Romanians teaching in the Romanian language was discussed in the Diet of Istria. The proposal was very popular among them. The Italian deputies showed their support, but the Croat ones opposed it and tried to show that the Istro-Romanians were in fact Slavs. During Austro-Hungarian rule, the Istro-Romanians lived under poverty conditions,Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from 1000 to 1946 and was a key part of the Habsburg monarchy from 1526-1918. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coro ...

. Jews accounted for 54% of commercial business owners, 85% of financial institution directors and owners in banking, and 62% of all employees in commerce, 20% of all general grammar school students, and 37% of all commercial scientific grammar school students, 31.9% of all engineering students, and 34.1% of all students in human faculties of the universities. Jews accounted for 48.5% of all physicians, and 49.4% of all lawyers/jurists in Hungary. Note: The numbers of Jews were reconstructed from religious censuses. They did not include the people of Jewish origin who had converted to Christianity, or the number of atheists. Among many Hungarian parliament members of Jewish origin, the most famous Jewish members in Hungarian political life were Minister of Justice Vilmos Vázsonyi, Minister of War Samu Hazai, Minister of Finance János Teleszky, and ministers of trade and .

Education

Universities in Cisleithania

The first university in the Austrian half of the Empire (Charles University) was founded by Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor, Emperor Charles IV in Prague in 1347, the second oldest university was the Jagiellonian University established in Kraków by the King of Poland Casimir III the Great in 1364, while the third oldest (University of Vienna) was founded by Rudolf IV, Duke of Austria, Duke Rudolph IV in 1365.

The higher educational institutions were predominantly German, but beginning in the 1870s, language shifts began to occur.

Universities in Transleithania

In the year 1276, the university of Veszprém was destroyed by the troops of Péter Csák and it was never rebuilt. A university was established by Louis I of Hungary in Pécs in 1367. Sigismund established a university at Óbuda in 1395. Another, Universitas Istropolitana, was established 1465 in Pozsony (Bratislava in Slovakia) by Mattias Corvinus. None of these medieval universities survived the Ottoman wars. Nagyszombat University was founded in 1635 and moved to Buda in 1777 where it is called Eötvös Loránd University. The world's first institute of technology was founded in Selmecbánya, Kingdom of Hungary (since 1920 Banská Štiavnica, Slovakia) in 1735. Its legal successor is the University of Miskolc in Hungary. The Budapest University of Technology and Economics (BME) is considered the oldest institute of technology in the world with university rank and structure. Its legal predecessor the Institutum Geometrico-Hydrotechnicum was founded in 1782 by Emperor Joseph II.

The high schools included the universities, of which Hungary possessed five, all maintained by the state: at Budapest (founded in 1635), at Kolozsvár (founded in 1872), and at Zagreb (founded in 1874). Newer universities were established in Debrecen in 1912, and Pozsony university was reestablished after a half millennium in 1912. They had four faculties: theology, law, philosophy and medicine (the university at Zagreb was without a faculty of medicine). There were in addition ten high schools of law, called academies, which in 1900 were attended by 1,569 pupils. The Polytechnicum in Budapest, founded in 1844, which contained four faculties and was attended in 1900 by 1,772 pupils, was also considered a high school. There were in Hungary in 1900 forty-nine theological colleges, twenty-nine Catholic, five Greek Uniat, four Greek Orthodox, ten Protestant and one Jewish. Among special schools the principal mining schools were at Selmeczbánya, Nagyág and Felsőbánya; the principal agricultural colleges at Debreczen and Kolozsvár; and there was a school of forestry at Selmeczbánya, military colleges at Budapest, Kassa, Déva and Zagreb, and a naval school at Fiume. There were in addition a number of training institutes for teachers and a large number of schools of commerce, several art schools – for design, painting, sculpture, and music.

In the year 1276, the university of Veszprém was destroyed by the troops of Péter Csák and it was never rebuilt. A university was established by Louis I of Hungary in Pécs in 1367. Sigismund established a university at Óbuda in 1395. Another, Universitas Istropolitana, was established 1465 in Pozsony (Bratislava in Slovakia) by Mattias Corvinus. None of these medieval universities survived the Ottoman wars. Nagyszombat University was founded in 1635 and moved to Buda in 1777 where it is called Eötvös Loránd University. The world's first institute of technology was founded in Selmecbánya, Kingdom of Hungary (since 1920 Banská Štiavnica, Slovakia) in 1735. Its legal successor is the University of Miskolc in Hungary. The Budapest University of Technology and Economics (BME) is considered the oldest institute of technology in the world with university rank and structure. Its legal predecessor the Institutum Geometrico-Hydrotechnicum was founded in 1782 by Emperor Joseph II.

The high schools included the universities, of which Hungary possessed five, all maintained by the state: at Budapest (founded in 1635), at Kolozsvár (founded in 1872), and at Zagreb (founded in 1874). Newer universities were established in Debrecen in 1912, and Pozsony university was reestablished after a half millennium in 1912. They had four faculties: theology, law, philosophy and medicine (the university at Zagreb was without a faculty of medicine). There were in addition ten high schools of law, called academies, which in 1900 were attended by 1,569 pupils. The Polytechnicum in Budapest, founded in 1844, which contained four faculties and was attended in 1900 by 1,772 pupils, was also considered a high school. There were in Hungary in 1900 forty-nine theological colleges, twenty-nine Catholic, five Greek Uniat, four Greek Orthodox, ten Protestant and one Jewish. Among special schools the principal mining schools were at Selmeczbánya, Nagyág and Felsőbánya; the principal agricultural colleges at Debreczen and Kolozsvár; and there was a school of forestry at Selmeczbánya, military colleges at Budapest, Kassa, Déva and Zagreb, and a naval school at Fiume. There were in addition a number of training institutes for teachers and a large number of schools of commerce, several art schools – for design, painting, sculpture, and music.

Economy

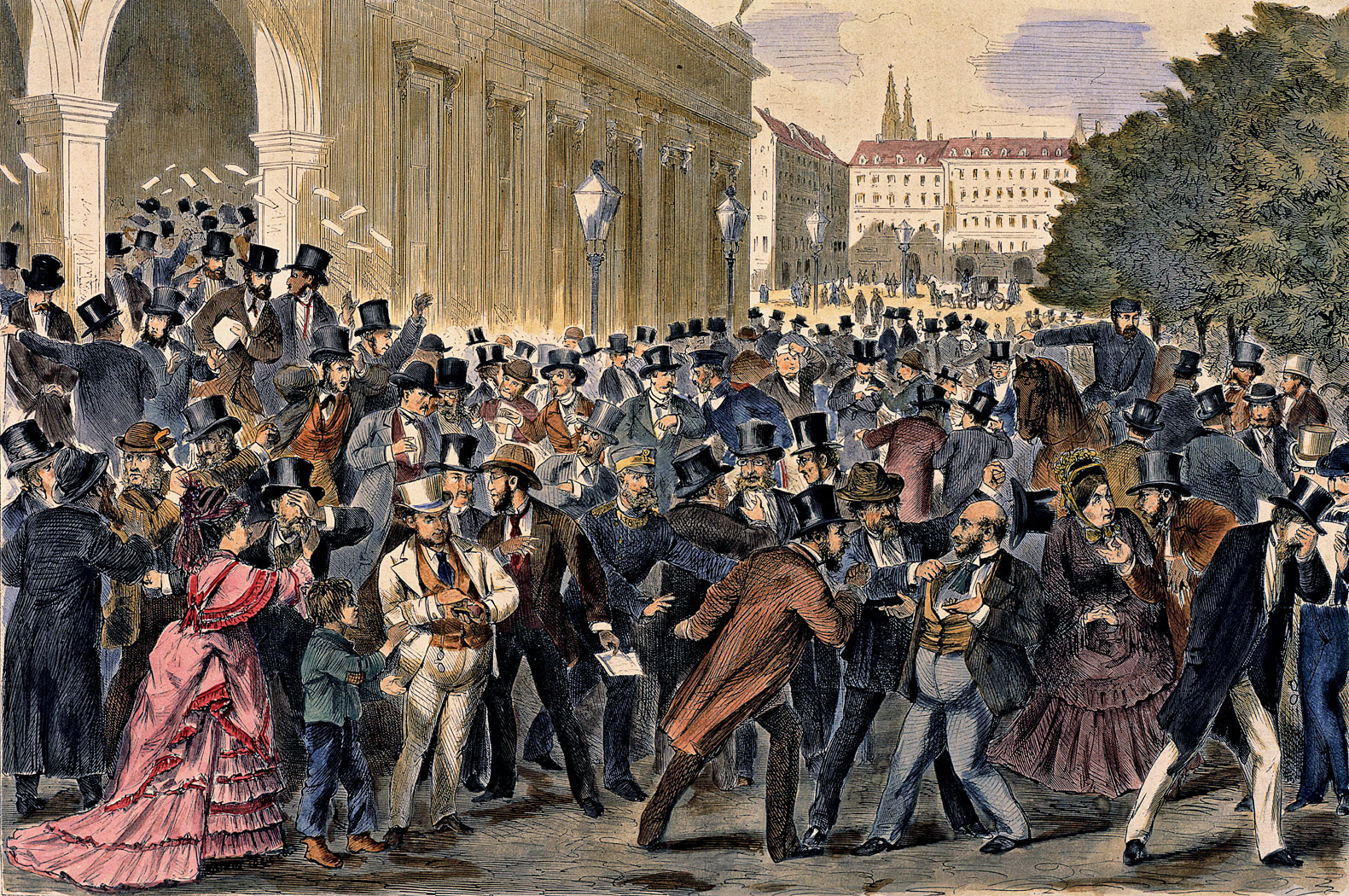

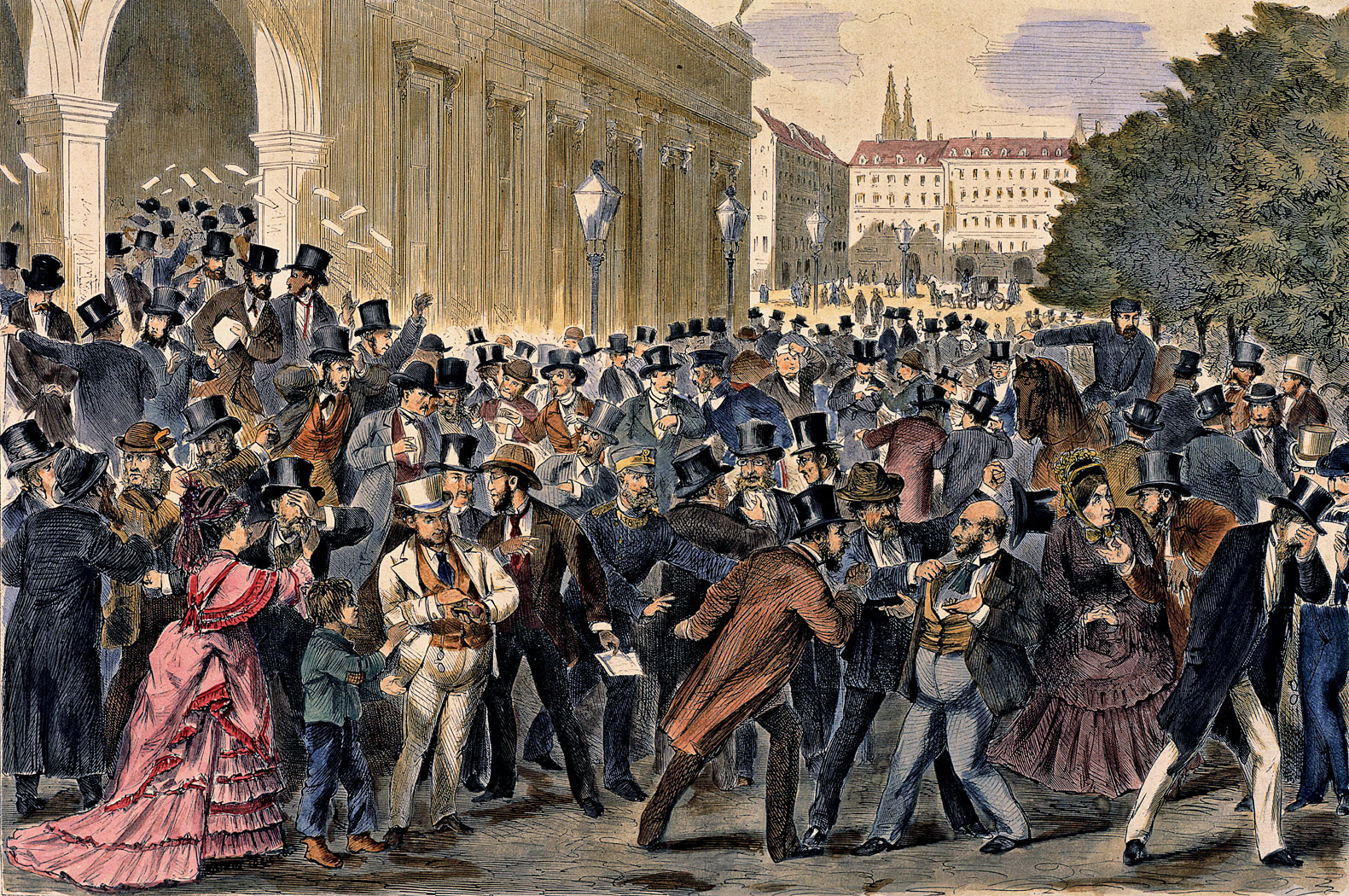

The heavily rural Austro-Hungarian economy slowly modernised after 1867. Railroads opened up once-remote areas, and cities grew. Many small firms promoted capitalist way of production. Technological change accelerated industrialization and urbanization. The first Austrian stock exchange (the Wiener Börse) was opened in 1771 in Vienna, the first stock exchange of the Kingdom of Hungary (the Budapest Stock Exchange) was opened in Budapest in 1864. The central bank (Bank of issue) was founded as Austrian National Bank in 1816. In 1878, it transformed into Austro-Hungarian National Bank with principal offices in both Vienna and Budapest. The central bank was governed by alternating Austrian or Hungarian governors and vice-governors. Austria-Hungary also became the world's third-largest manufacturer and exporter of electric home appliances, electric industrial appliances, and power generation apparatus for power plants, after the United States and the German Empire, and it constructed Europe's second-largest railway network, after the German Empire. In 2000, a study estimated that GDP in constant national prices in 1913 was 19,140.8 million for Cisleithania and 10,971.6 million for Transleithania, a combined 30,112.4 million Austro-Hungarian krone, krone.

The heavily rural Austro-Hungarian economy slowly modernised after 1867. Railroads opened up once-remote areas, and cities grew. Many small firms promoted capitalist way of production. Technological change accelerated industrialization and urbanization. The first Austrian stock exchange (the Wiener Börse) was opened in 1771 in Vienna, the first stock exchange of the Kingdom of Hungary (the Budapest Stock Exchange) was opened in Budapest in 1864. The central bank (Bank of issue) was founded as Austrian National Bank in 1816. In 1878, it transformed into Austro-Hungarian National Bank with principal offices in both Vienna and Budapest. The central bank was governed by alternating Austrian or Hungarian governors and vice-governors. Austria-Hungary also became the world's third-largest manufacturer and exporter of electric home appliances, electric industrial appliances, and power generation apparatus for power plants, after the United States and the German Empire, and it constructed Europe's second-largest railway network, after the German Empire. In 2000, a study estimated that GDP in constant national prices in 1913 was 19,140.8 million for Cisleithania and 10,971.6 million for Transleithania, a combined 30,112.4 million Austro-Hungarian krone, krone.

Infrastructure

Telecommunications

Telegraph

The first telegraph connection (Vienna—Brno—Prague) had started operation in 1847. In Hungarian territory the first telegraph stations were opened in Pressburg (''Pozsony'', today's Bratislava) in December 1847 and in Buda in 1848. The first telegraph connection between Vienna and Pest–Buda (later Budapest) was constructed in 1850, and Vienna–Zagreb in 1850.

Telephone

The first telephone exchange was opened in Zagreb (8 January 1881),

Electronic audio broadcasting

The Telefon Hírmondó (Telephone Herald) news and entertainment service was introduced in Budapest in 1893. Two decades before the introduction of radio broadcasting, people could listen to political, economic and sports news, cabaret, music and opera in Budapest daily. It operated over a special type of telephone exchange system.

Rail transport

By 1913, the combined length of the railway tracks of the Austrian Empire and Kingdom of Hungary reached . In Western Europe only Germany had more extended railway network (); the Austro-Hungarian Empire was followed by France (), the United Kingdom (), Italy () and Spain ().

By 1913, the combined length of the railway tracks of the Austrian Empire and Kingdom of Hungary reached . In Western Europe only Germany had more extended railway network (); the Austro-Hungarian Empire was followed by France (), the United Kingdom (), Italy () and Spain ().

Railways in Transleithania

The first Hungarian steam locomotive railway line was opened on 15 July 1846 between Pest and Vác. In 1890 most large Hungarian private railway companies were nationalized as a consequence of the poor management of private companies, except the strong Austrian-owned Kaschau-Oderberg Railway (KsOd) and the Austrian-Hungarian Southern Railway (SB/DV). They also joined the zone tariff system of the MÁV (Hungarian State Railways). By 1910, the total length of the rail networks of Hungarian Kingdom reached , the Hungarian network linked more than 1,490 settlements. Nearly half (52%) of the empire's railways were built in Hungary, thus the railroad density there became higher than that of Cisleithania. This has ranked Hungarian railways the 6th most dense in the world (ahead of Germany and France).

Electrified commuter railways: A set of four electric commuter rai lines were built in Budapest, the BHÉV: Ráckeve line (1887), Szentendre line (1888), Gödöllő line (1888), Csepel line (1912)

Tramway lines in the cities

Horse-drawn tramways appeared in the first half of the 19th century. Between the 1850s and 1880s many were built : Vienna (1865), Budapest (1866), Brno (1869), Trieste (1876). Steam trams appeared in the late 1860s. The electrification of tramways started in the late 1880s. The first electrified tramway in Austria–Hungary was built in Budapest in 1887.

Electric tramway lines in the Austrian Empire:

* Austria: Gmunden (1894); Linz, Vienna (1897); Graz (1898); Trieste (1900); Ljubljana (1901); Innsbruck (1905); Unterlach, Ybbs an der Donau (1907); Salzburg (1909); Klagenfurt, Sankt Pölten (1911); Piran (1912)

* Austrian Littoral: Pula (1904).

* Bohemia: Prague (1891); Teplice (1895); Liberec (1897); Ústí nad Labem, Plzeň, Olomouc (1899); Moravia, Brno, Jablonec nad Nisou (1900); Ostrava (1901); Mariánské Lázně (1902); Budějovice, České Budějovice, Jihlava (1909)

* Austrian Silesia: Opava (Troppau) (1905), Cieszyn (Cieszyn) (1911)

* Dalmatia: Dubrovnik (1910)

* Galicia: Trams in Lviv, Lviv (1894), Bielsko-Biała (1895); Kraków (1901); Tarnów, Cieszyn (1911)

Electric tramway lines in the Kingdom of Hungary:

* Hungary: Budapest (1887); Pressburg/Pozsony/Bratislava (1895); Szabadka/Subotica (1897), Szombathely (1897), Miskolc (1897); Temesvár/Timișoara (1899); Sopron (1900); Szatmárnémeti/Satu Mare (1900); Nyíregyháza (1905); Nagyszeben/Sibiu (1905); Nagyvárad/Oradea (1906); Szeged (1908); Debrecen (1911); Újvidék/Novi Sad (1911); Kassa/Košice (1913); Pécs (1913)

* Croatia: Fiume (1899); Pula (1904); Opatija – Lovran (1908); Zagreb (1910); Dubrovnik (1910).

Underground

The Budapest Metro Line 1 (Budapest Metro), Line 1 (originally the "Franz Joseph Underground Electric Railway Company") is the second oldest underground railway in the world (the first being the London Underground's Metropolitan Line and the third being Glasgow), and the first on the European mainland. It was built from 1894 to 1896 and opened on 2 May 1896. In 2002, it was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The M1 line became an IEEE Milestone due to the radically new innovations in its era: "Among the railway's innovative elements were bidirectional tram cars; electric lighting in the subway stations and tram cars; and an overhead wire structure instead of a third-rail system for power".

Inland waterways and river regulation

The first Danubian steamer company, Donaudampfschiffahrtsgesellschaft (DDSG), was the world's largest inland shipping company until the collapse of Austria-Hungary.

In 1900 the engineer C. Wagenführer drew up plans to link the Danube and the Adriatic Sea by a canal from Vienna to Trieste. It was born from the desire of Austria–Hungary to have a direct link to the Adriatic Sea but was never constructed.

Lower Danube and the Iron Gates

In 1831 a plan had already been drafted to make the passage navigable, at the initiative of the Hungarian politician István Széchenyi. Finally Gábor Baross, Hungary's "Iron Minister", succeeded in financing this project. The riverbed rocks and the associated rapids made the gorge valley an infamous passage for shipping. In German, the passage is still known as the Kataraktenstrecke, even though the cataracts are gone. Near the actual "Iron Gates" strait the Prigrada rock was the most important obstacle until 1896: the river widened considerably here and the water level was consequently low. Upstream, the Greben rock near the "Kazan" gorge was notorious.

Tisza River

The length of the Tisza river in Hungary used to be . It flowed through the Great Hungarian Plain, which is one of the largest flat areas in central Europe. Since plains can cause a river to flow very slowly, the Tisza used to follow a path with many curves and turns, which led to many large floods in the area.

After several small-scale attempts, István Széchenyi organised the "regulation of the Tisza" (Hungarian: a Tisza szabályozása) which started on 27 August 1846, and substantially ended in 1880. The new length of the river in Hungary was ( total), with of "dead channels" and of new riverbed. The resultant length of the flood-protected river comprises (out of of all Hungarian protected rivers).

Shipping and ports

The most important seaport was Trieste (today part of Italy), where the Austrian merchant marine was based. Two major shipping companies (Austrian Lloyd and Austro-Americana) and several shipyards were located there. From 1815 to 1866, Venice had been part of the Habsburg empire. The loss of Venice prompted the development of the Austrian merchant marine. By 1913, the commercial marine of Austria, comprised 16,764 vessels with a tonnage of 471,252, and crews number-ing 45,567. Of the total (1913) 394 of 422,368 tons were steamers, and 16,370 of 48,884 tons were sailing vessels The Austrian Lloyd was one of the biggest ocean shipping companies of the time. Prior to the beginning of World War I, the company owned 65 middle-sized and large steamers. The Austro-Americana owned one third of this number, including the biggest Austrian passenger ship, the SS ''Kaiser Franz Joseph I''. In comparison to the Austrian Lloyd, the Austro-American concentrated on destinations in North and South America.

The most important seaport was Trieste (today part of Italy), where the Austrian merchant marine was based. Two major shipping companies (Austrian Lloyd and Austro-Americana) and several shipyards were located there. From 1815 to 1866, Venice had been part of the Habsburg empire. The loss of Venice prompted the development of the Austrian merchant marine. By 1913, the commercial marine of Austria, comprised 16,764 vessels with a tonnage of 471,252, and crews number-ing 45,567. Of the total (1913) 394 of 422,368 tons were steamers, and 16,370 of 48,884 tons were sailing vessels The Austrian Lloyd was one of the biggest ocean shipping companies of the time. Prior to the beginning of World War I, the company owned 65 middle-sized and large steamers. The Austro-Americana owned one third of this number, including the biggest Austrian passenger ship, the SS ''Kaiser Franz Joseph I''. In comparison to the Austrian Lloyd, the Austro-American concentrated on destinations in North and South America.

Military

The Austro-Hungarian Army was under the command of Archduke Albrecht, Duke of Teschen (1817–1895), an old-fashioned bureaucrat who opposed modernization. The military system of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy was similar in both states, and rested since 1868 upon the principle of the universal and personal obligation of the citizen to bear arms. Its military force was composed of the Common Army

The Common Army (, ) as it was officially designated by the Imperial and Royal Military Administration, was the largest part of the Austro-Hungarian land forces from 1867 to 1914, the other two elements being the Imperial-Royal Landwehr (of Au ...

; the special armies, namely the Imperial-Royal Landwehr, Austrian Landwehr, and the Royal Hungarian Honvéd, Hungarian ''Honvéd'', which were separate national institutions, and the Landsturm or levy-en masse. As stated above, the common army stood under the administration of the joint minister of war, while the special armies were under the administration of the respective ministries of national defence. The yearly contingent of recruits for the army was fixed by the military bills voted on by the Austrian and Hungarian parliaments and was generally determined on the basis of the population, according to the last census returns. It amounted in 1905 to 103,100 men, of which Austria furnished 59,211 men, and Hungary 43,889. Besides 10,000 men were annually allotted to the Austrian Landwehr, and 12,500 to the Hungarian Honved. The term of service was two years (three years in the cavalry) with the colours, seven or eight in the reserve and two in the Landwehr; in the case of men not drafted to the active army the same total period of service was spent in various special reserves.

1877–1914: Russo-Turkish War, Congress of Berlin, Balkan instability and the Bosnia Crisis

Russian Pan-Slavic organizations sent aid to the Balkan rebels and so pressured the tsar's government to declare war on the Ottoman Empire in 1877 in the name of protecting Orthodox Christians.

Russian Pan-Slavic organizations sent aid to the Balkan rebels and so pressured the tsar's government to declare war on the Ottoman Empire in 1877 in the name of protecting Orthodox Christians.Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

. On the heels of the Great Balkan Crisis, Austro-Hungarian forces occupied Bosnia and Herzegovina in August 1878 and the monarchy eventually Austro-Hungarian annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina in October 1908 as a common holding of Cisleithania and Transleithania under the control of the Ministry of Finance (Austria-Hungary), Imperial & Royal finance ministry rather than attaching it to either territorial government. The annexation in 1908 led some in Vienna to contemplate combining Bosnia and Herzegovina with Croatia to form a third Slavic component of the monarchy. The deaths of Franz Joseph's brother, Maximilian I of Mexico, Maximilian (1867), and his only son, Rudolf, Crown Prince of Austria, Rudolf, made the Emperor's nephew, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne. The Archduke was rumoured to have been an advocate for this trialism as a means to limit the power of the Hungarian aristocracy.

A proclamation issued on the occasion of its annexation to the Habsburg monarchy in October 1908 promised these lands constitutional institutions, which should secure to their inhabitants full civil rights and a share in the management of their own affairs by means of a local representative assembly. In performance of this promise a constitution was promulgated in 1910.

The principal players in the Bosnian Crisis#Buchlau Bargain, Bosnian Crisis of 1908–09 were the foreign ministers of Austria and Russia, Alois Lexa von Aehrenthal and Alexander Izvolsky. Both were motivated by political ambition; the first would emerge successful, and the latter would be broken by the crisis. Along the way, they would drag Europe to the brink of war in 1909. They would also divide Europe into the two armed camps that would go to war in July 1914.

On the heels of the Great Balkan Crisis, Austro-Hungarian forces occupied Bosnia and Herzegovina in August 1878 and the monarchy eventually Austro-Hungarian annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina in October 1908 as a common holding of Cisleithania and Transleithania under the control of the Ministry of Finance (Austria-Hungary), Imperial & Royal finance ministry rather than attaching it to either territorial government. The annexation in 1908 led some in Vienna to contemplate combining Bosnia and Herzegovina with Croatia to form a third Slavic component of the monarchy. The deaths of Franz Joseph's brother, Maximilian I of Mexico, Maximilian (1867), and his only son, Rudolf, Crown Prince of Austria, Rudolf, made the Emperor's nephew, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne. The Archduke was rumoured to have been an advocate for this trialism as a means to limit the power of the Hungarian aristocracy.

A proclamation issued on the occasion of its annexation to the Habsburg monarchy in October 1908 promised these lands constitutional institutions, which should secure to their inhabitants full civil rights and a share in the management of their own affairs by means of a local representative assembly. In performance of this promise a constitution was promulgated in 1910.

The principal players in the Bosnian Crisis#Buchlau Bargain, Bosnian Crisis of 1908–09 were the foreign ministers of Austria and Russia, Alois Lexa von Aehrenthal and Alexander Izvolsky. Both were motivated by political ambition; the first would emerge successful, and the latter would be broken by the crisis. Along the way, they would drag Europe to the brink of war in 1909. They would also divide Europe into the two armed camps that would go to war in July 1914.

Aehrenthal had started with the assumption that the Slavic minorities could never come together, and the Balkan League would never cause any damage to Austria. He turned down an Ottoman proposal for an alliance that would include Austria, Turkey, and Romania. However, his policies alienated the Bulgarians, who turned instead to Russia and Serbia. Although Austria had no intention to embark on additional expansion to the south, Aehrenthal encouraged speculation to that effect, expecting that it would paralyze the Balkan states. Instead, it incited them to feverish activity to create a defensive block to stop Austria. A series of grave miscalculations at the highest level thus significantly strengthened Austria's enemies.

In 1914, Slavic militants in Bosnia rejected Austria's plan to fully absorb the area; they assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, assassinated the Austrian heir and precipitated World War I.

Aehrenthal had started with the assumption that the Slavic minorities could never come together, and the Balkan League would never cause any damage to Austria. He turned down an Ottoman proposal for an alliance that would include Austria, Turkey, and Romania. However, his policies alienated the Bulgarians, who turned instead to Russia and Serbia. Although Austria had no intention to embark on additional expansion to the south, Aehrenthal encouraged speculation to that effect, expecting that it would paralyze the Balkan states. Instead, it incited them to feverish activity to create a defensive block to stop Austria. A series of grave miscalculations at the highest level thus significantly strengthened Austria's enemies.

In 1914, Slavic militants in Bosnia rejected Austria's plan to fully absorb the area; they assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, assassinated the Austrian heir and precipitated World War I.

1914–1918: World War I

Prelude of WW I

The 28 June 1914 assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in the Bosnian capital, Sarajevo, excessively intensified the existing traditional religion-based ethnic hostilities in Bosnia. However, in Sarajevo itself, Austrian authorities encouraged

The 28 June 1914 assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in the Bosnian capital, Sarajevo, excessively intensified the existing traditional religion-based ethnic hostilities in Bosnia. However, in Sarajevo itself, Austrian authorities encouraged Some members of the government, such as Minister of Foreign Affairs Count Leopold Berchtold and Army Commander Count Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf, had wanted to confront the resurgent Serbian nation for some years in a preventive war, but the Emperor and Hungarian prime minister

Some members of the government, such as Minister of Foreign Affairs Count Leopold Berchtold and Army Commander Count Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf, had wanted to confront the resurgent Serbian nation for some years in a preventive war, but the Emperor and Hungarian prime minister István Tisza

Count István Imre Lajos Pál Tisza de Borosjenő et Szeged (, English: Stephen Emery Louis Paul Tisza, short name: Stephen Tisza); (22 April 1861 – 31 October 1918) was a politician who served as Prime Minister of Hungary, prime minister ...

were opposed. The foreign ministry of Austro-Hungarian Empire sent ambassador László Szőgyény-Marich Jr., László Szőgyény to Potsdam, where he inquired about the standpoint of the German emperor, Wilhelm II, on 5 July and received a supportive response.

The leaders of Austria–Hungary therefore decided to confront Serbia militarily before it could incite a revolt; using the assassination as an excuse, they presented a list of ten demands called the July Ultimatum,

Wartime foreign policy

The Austro-Hungarian Empire played a relatively passive diplomatic role in the war, as it was increasingly dominated and controlled by Germany. The only goal was to punish Serbia and try to stop the ethnic breakup of the Empire, and it completely failed. Starting in late 1916 the new Emperor Karl removed the pro-German officials and opened peace overtures to the Allies, whereby the entire war could be ended by compromise, or perhaps Austria would make a separate peace from Germany.

Homefront

The heavily rural empire did have a small industrial base, but its major contributions were manpower and food.

Theaters of operations

The Austro-Hungarian Empire conscripted 7.8 million soldiers during the war. General von Hötzendorf was the Chief of the Austro-Hungarian General Staff. Franz Joseph I, who was much too old to command the army, appointed Archduke Friedrich, Duke of Teschen, Archduke Friedrich von Österreich-Teschen as Supreme Army Commander (Armeeoberkommandant), but asked him to give Von Hötzendorf freedom to take any decisions. Von Hötzendorf remained in effective command of the military forces until Emperor Karl I took supreme command himself in late 1916 and dismissed Conrad von Hötzendorf in 1917. Meanwhile, economic conditions on the home front deteriorated rapidly. The empire depended on agriculture, and agriculture depended on the heavy labor of millions of men who were now in the army. Food production fell, the transportation system became overcrowded, and industrial production could not successfully handle the overwhelming need for munitions. Germany provided a great deal of help, but it was not enough. Furthermore, the political instability of the multiple ethnic groups within the empire now ripped apart any hope for national consensus in support of the war. Increasingly there was a demand for breaking up the empire and setting up autonomous national states based on historic, language-based cultures. The new emperor sought peace terms from the Allies, but his initiatives were vetoed by Italy.

Serbian front 1914–1916

At the start of the war, the army was divided into two: the smaller part attacked Serbia, while the larger part fought against the formidable Imperial Russian Army. The invasion of Serbia in 1914 was a disaster: by the end of the year, the Austro-Hungarian Army had taken no territory, but had lost 227,000 out of a total force of 450,000 men. However, in the autumn of 1915, the Serbian Army was defeated by the Central Powers, which led to the occupation of Serbia. Near the end of 1915, in a massive rescue operation involving more than 1,000 trips made by Italian, French and British steamers, 260,000 Serb soldiers were transported to Brindisi and Corfu, where they waited for the chance of the victory of Allied powers to reclaim their country. Corfu hosted the Serbian government in exile after the collapse of Serbia and served as a supply base for the Greek front. In April 1916 a large number of Serbian troops were transported in British and French naval vessels from Corfu to mainland Greece. The contingent numbering over 120,000 relieved a much smaller army at the Macedonian front and fought alongside British and French troops.

At the start of the war, the army was divided into two: the smaller part attacked Serbia, while the larger part fought against the formidable Imperial Russian Army. The invasion of Serbia in 1914 was a disaster: by the end of the year, the Austro-Hungarian Army had taken no territory, but had lost 227,000 out of a total force of 450,000 men. However, in the autumn of 1915, the Serbian Army was defeated by the Central Powers, which led to the occupation of Serbia. Near the end of 1915, in a massive rescue operation involving more than 1,000 trips made by Italian, French and British steamers, 260,000 Serb soldiers were transported to Brindisi and Corfu, where they waited for the chance of the victory of Allied powers to reclaim their country. Corfu hosted the Serbian government in exile after the collapse of Serbia and served as a supply base for the Greek front. In April 1916 a large number of Serbian troops were transported in British and French naval vessels from Corfu to mainland Greece. The contingent numbering over 120,000 relieved a much smaller army at the Macedonian front and fought alongside British and French troops.

Russian front 1914–1917

On the Eastern Front (World War I), Eastern front, the war started out equally poorly. The government accepted the Polish proposal of establishing the Supreme National Committee as the Polish central authority within the empire, responsible for the formation of the Polish Legions in World War I, Polish Legions, an auxiliary military formation within the Austro-Hungarian Army. The Austro-Hungarian Army was defeated at the Battle of Galicia, Battle of Lemberg and the great fortress city of Siege of Przemyśl, Przemyśl was besieged and fell in March 1915. The Gorlice–Tarnów Offensive started as a minor German offensive to relieve the pressure of the Russian numerical superiority on the Austro-Hungarians, but the cooperation of the Central Powers resulted in huge Russian losses and the total collapse of the Russian lines and their long retreat into Russia. The Russian Third Army disintegrated. In summer 1915, the Austro-Hungarian Army, under a unified command with the Germans, participated in the successful Gorlice–Tarnów Offensive. From June 1916, the Russians focused their attacks on the Austro-Hungarian Army in the Brusilov Offensive, recognizing the latter's numerical inferiority. By the end of September 1916, Austria–Hungary mobilized and concentrated new divisions, and the successful Russian advance was halted and slowly repelled; but the Austrian armies took heavy losses (about 1 million men) and never recovered. Nevertheless, the huge losses in men and materiel inflicted on the Russians during the offensive contributed greatly to the Russian Revolution of 1917 and caused an economic crash in the Russian Empire.