The Australian Services Contingent was the

Australian Army

The Australian Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of Australia, a part of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Australian Air Force. The Army is commanded by the Chief of Army (Austral ...

contribution to the

United Nations Transition Assistance Group

The United Nations Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG) was a United Nations (UN) peacekeeping force deployed from April 1989 to March 1990 in Namibia, known at the time as South West Africa, to monitor the peace process and elections there. Na ...

(UNTAG)

peacekeeping

Peacekeeping comprises activities intended to create conditions that favour lasting peace. Research generally finds that peacekeeping reduces civilian and battlefield deaths, as well as reduces the risk of renewed warfare.

Within the United N ...

mission to

Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

in 1989 and 1990. Australia sent two contingents of over 300 engineers each to assist the

Special Representative of the Secretary General A Special Representative of the Secretary-General is a highly respected expert who has been appointed by the Secretary-General of the United Nations to represent them in meetings with heads of state on critical human rights issues. The representativ ...

,

Martti Ahtisaari

Martti Oiva Kalevi Ahtisaari (; born 23 June 1937) is a Finnish politician, the tenth president of Finland (1994–2000), a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, and a United Nations diplomat and mediator noted for his international peace work.

Ahtisa ...

, in overseeing free and fair elections in Namibia for a

Constituent Assembly

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

in what was the largest deployment of Australian troops since the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

.

The Australian mission was widely reported as successful.

Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

John Crocker, commander of the second Australian contingent (2ASC), wrote that the November 1989 election was UNTAG's ''raison d'être'' and observed that "the Australian contingent's complete and wide-ranging support was critical to the success of that election and hence the mission – a fact that has been acknowledged at the highest level in UNTAG".

Javier Pérez de Cuéllar

Javier Felipe Ricardo Pérez de Cuéllar de la Guerra (; ; 19 January 1920 – 4 March 2020) was a Peruvian diplomat and politician who served as the fifth Secretary-General of the United Nations from 1982 to 1991. He later served as Prime Mini ...

,

Secretary-General of the United Nations

The secretary-general of the United Nations (UNSG or SG) is the chief administrative officer of the United Nations and head of the United Nations Secretariat, one of the six principal organs of the United Nations.

The role of the secretary-g ...

, wrote to

Gareth Evans (Australia's

Foreign Minister

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between cou ...

) about the "remarkable contribution made by the Australian military and electoral personnel", saying that their "dedication and professionalism had been widely and deservedly praised". Although a total of 19 UN personnel lost their lives in Namibia, the two Australian contingents achieved their mission without sustaining any fatalities – one of the few military units in UNTAG to do so.

Overall, the UNTAG mission assisted Namibia in transitioning to a democratic government after the racial segregation of the

apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

system. The military forces did not fire a shot during the operation, and Mays called it "possibly the most successful UN peacekeeping operation ever fielded"; Hearn called it "one of the major successes of the United Nations". Almost 20 years later, in a message to the annual session of the

United Nations Special Committee on Decolonization

The United Nations Special Committee on the Situation with Regard to the Implementation of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, or the Special Committee on Decolonization (C-24), is a committee of ...

on 28 February 2008,

UN Secretary-General

The secretary-general of the United Nations (UNSG or SG) is the chief administrative officer of the United Nations and head of the United Nations Secretariat, one of the six principal organs of the United Nations.

The role of the secretary-ge ...

Ban Ki-moon

Ban Ki-moon (; ; born 13 June 1944) is a South Korean politician and diplomat who served as the eighth secretary-general of the United Nations between 2007 and 2016. Prior to his appointment as secretary-general, Ban was his country's Minister ...

noted that "facilitating this process" constituted "one of the proudest chapters of our Organization's history".

Background

History of conflict

Southwest Africa has a

rich history encompassing colonisation, war and genocide. The first European to set foot on Namibian soil was the

Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

explorer

Diogo Cão

Diogo Cão (; -1486), anglicised as Diogo Cam and also known as Diego Cam, was a Portuguese explorer and one of the most notable navigators of the Age of Discovery. He made two voyages sailing along the west coast of Africa in the 1480s, explorin ...

in 1485. Over the next 500 years, the country was

colonised

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

by the Dutch, English and Germans. Namibia was a German colony (

German South-West Africa

German South West Africa (german: Deutsch-Südwestafrika) was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 until 1915, though Germany did not officially recognise its loss of this territory until the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. With a total area of ...

) from 1884 until its annexation by

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

during

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. After the war, it was

mandated to South Africa by the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

. After

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

(UN) asked South Africa to place Namibia under

UN trusteeship

The United Nations Trusteeship Council (french: links=no, Conseil de tutelle des Nations unies) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations, established to help ensure that trust territories were administered in the best interests ...

, but South Africa refused. Legal arguments continued until 1966 when the

UN General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Curr ...

resolved to end the mandate, declaring that henceforth South-West Africa was the direct responsibility of the UN.

At the height of the

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

in 1965, conflict escalated across the border with the

Cuban intervention in Angola

The Cuban intervention in Angola (codenamed Operation Carlota) began on 5 November 1975, when Cuba sent combat troops in support of the communist-aligned People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) against the pro-western National Unio ...

. Cuba formed an alliance with the

People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola

The People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola ( pt, Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola, abbr. MPLA), for some years called the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola – Labour Party (), is an Angolan left-wing, social de ...

(MPLA) ( pt, Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola – Partido do Trabalho), which led to the deployment of more than 25,000 Cuban soldiers to the region in the

Angolan War of Independence

The Angolan War of Independence (; 1961–1974), called in Angola the ("Armed Struggle of National Liberation"), began as an uprising against forced cultivation of cotton, and it became a multi-faction struggle for the control of Portugal ...

.

The next year the

Namibian War of Independence

The South African Border War, also known as the Namibian War of Independence, and sometimes denoted in South Africa as the Angolan Bush War, was a largely asymmetric conflict that occurred in Namibia (then South West Africa), Zambia, and Angol ...

began when the South-West Africa People's Organisation's (

SWAPO

The South West Africa People's Organisation (, SWAPO; af, Suidwes-Afrikaanse Volks Organisasie, SWAVO; german: Südwestafrikanische Volksorganisation, SWAVO), officially known as the SWAPO Party of Namibia, is a political party and former ind ...

) military wing – the

People's Liberation Army of Namibia

The People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN) was the military wing of the South West Africa People's Organisation (SWAPO). It fought against the South African Defence Force (SADF) and South West African Territorial Force (SWATF) during the Sout ...

(PLAN) – began guerrilla attacks on South African forces, infiltrating from bases in

Zambia

Zambia (), officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central Africa, Central, Southern Africa, Southern and East Africa, although it is typically referred to as being in Southern Africa at its most cent ...

. The first attack was the battle at

Omugulugwombashe

Omugulugwombashe (also: ''Ongulumbashe'', official: ''Omugulu gwOombashe''; Otjiherero: ''giraffe leg'') is a settlement in the Tsandi electoral constituency in the Omusati Region of northern Namibia. The settlement features a clinic and a primar ...

on 26 August, and the war was a classic insurgent-counterinsurgent operation. PLAN initially established bases in northern Namibia; they were later forced out of the country by the

South African Defence Force

The South African Defence Force (SADF) (Afrikaans: ''Suid-Afrikaanse Weermag'') comprised the armed forces of South Africa from 1957 until 1994. Shortly before the state reconstituted itself as a republic in 1961, the former Union Defence F ...

(SADF), subsequently operating from bases in southern Angola and Zambia. The intensity of cross-border conflict escalated, becoming known as the

South African Border War

The South African Border War, also known as the Namibian War of Independence, and sometimes denoted in South Africa as the Angolan Bush War, was a largely asymmetric conflict that occurred in Namibia (then South West Africa), Zambia, and Angol ...

and the Angolan Bush War.

The principal protagonists were the SADF and the PLAN. Other groups involved included the

South West African Territorial Force

The South West Africa Territorial Force (SWATF) was an auxiliary arm of the South African Defence Force (SADF) and comprised the armed forces of South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1977 to 1989. It emerged as a product of South Africa's politic ...

(SWATF) and

National Union for Total Independence of Angola

The National Union for the Total Independence of Angola ( pt, União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola, abbr. UNITA) is the second-largest political party in Angola. Founded in 1966, UNITA fought alongside the Popular Movement for ...

(UNITA) (both aligned with the SADF) and the

People's Armed Forces for the Liberation of Angola

The People's Armed Forces of Liberation of Angola ( pt, Forças Armadas Populares de Libertação de Angola) or FAPLA was originally the armed wing of the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) but later (1975–1991) became Ango ...

(FAPLA) and

Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces

The Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces ( es, Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias; FAR) are the military forces of Cuba. They include ground forces, naval forces, air and air defence forces, and other paramilitary bodies including the Territorial Tro ...

(both aligned with SWAPO). The South African-aligned forces consisted of regular army (SADF),

South West African Police

The South West African Police (SWAPOL) was the national police force of South West Africa (now Namibia), responsible for law enforcement and public safety in South West Africa when the territory was administered by South Africa. It was organised ...

forces and the South West Africa Police Counter-Insurgency Unit (SWAPOL-COIN), including the paramilitary-trained SWAPOL police

counter-insurgency

Counterinsurgency (COIN) is "the totality of actions aimed at defeating irregular forces". The Oxford English Dictionary defines counterinsurgency as any "military or political action taken against the activities of guerrillas or revolutionar ...

unit known as

Koevoet

Koevoet (, meaning '' crowbar'', also known as Operation K or SWAPOL-COIN) was the counterinsurgency branch of the South West African Police (SWAPOL). Its formations included white South African police officers, usually seconded from the South ...

.

From a Namibian perspective, the nature of the closely intertwined Angolan War of Independence, Namibian War of Independence and South African Border War was typically cross-border conflict. This was overshadowed by two large-scale Cuban military interventions in the Angolan War of Independence. The first was in November 1975 (on the eve of Angola's independence), which further intensified with the escalation of the

Angolan Civil War

The Angolan Civil War ( pt, Guerra Civil Angolana) was a civil war in Angola, beginning in 1975 and continuing, with interludes, until 2002. The war immediately began after Angola became independent from Portugal in November 1975. The war was ...

in 1985. In that conflict, South Africa provided support across the northern border to UNITA. In opposition, the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

financially backed an estimated two motorised infantry divisions of Cuban troops in a

Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

-led the

People's Armed Forces for the Liberation of Angola

The People's Armed Forces of Liberation of Angola ( pt, Forças Armadas Populares de Libertação de Angola) or FAPLA was originally the armed wing of the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) but later (1975–1991) became Ango ...

(FAPLA) offensive against UNITA in what became known as the second Cuban intervention in Angola. In September 1987, Cuban forces came to the defence of the besieged Angolan Army (FAPLA) and stopped the advance of the SADF at the

Battle of Cuito Cuanavale

The Battle of Cuito Cuanavale was fought intermittently between 14 August 1987 and 23 March 1988, south and east of the town of Cuito Cuanavale, Angola, by the People's Armed Forces for the Liberation of Angola (FAPLA) and advisors and soldie ...

(the largest battle in Africa since World War II). General

Magnus Malan

General Magnus André de Merindol Malan (30 January 1930 – 18 July 2011) was a South African military figure and politician during the last years of apartheid in South Africa. He served respectively as Minister of Defence in the cabinet of P ...

wrote in his memoirs that this campaign marked a great victory for the SADF.

Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (; ; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activist who served as the President of South Africa, first president of South Africa from 1994 to 1 ...

disagreed; Cuito Cuanavale, he asserted, "was the turning point for the liberation of our continent—and of my people—from the scourge of apartheid". This battle led to

UN Security Council Resolution 602 of 25 November 1987, demanding the SADF's unconditional withdrawal from Angola by 10 December. When the UN force deployed to Namibia in April 1989, there were 50,000 Cuban troops in Angola.

During the 20-year war the SADF mounted many cross-border operations against PLAN bases, some of which extended into Angola. SADF units frequently remained in southern Angola to intercept PLAN combatants on their way south, forcing PLAN to move to bases far from the Namibian border. Most PLAN insurgency operations took the form of small

raids on political activists, armed propaganda activity,

recruitment

Recruitment is the overall process of identifying, sourcing, screening, shortlisting, and interviewing candidates for jobs (either permanent or temporary) within an organization. Recruitment also is the processes involved in choosing individual ...

, raids on white settlements and disruption of essential services.

United Nations Transition Assistance Group

The process leading to Namibia's independence began with UN General Assembly Resolution 2145 (XXI) of 27 October 1966. This was followed by the passage of

UN Security Council Resolution 264, adopted on 20 March 1969. In that resolution the UN assumed direct responsibility for the territory and declared the continued presence of South Africa in Namibia illegal, calling upon the

Government of South Africa

The Republic of South Africa is a parliamentary republic with three-tier system of government and an independent judiciary, operating in a parliamentary system. Legislative authority is held by the Parliament of South Africa.

Executive authority ...

to withdraw immediately. International negotiations for a peaceful solution to the Namibian problem increased. In December 1978, in what was known as the

Brazzaville

Brazzaville (, kg, Kintamo, Nkuna, Kintambo, Ntamo, Mavula, Tandala, Mfwa, Mfua; Teke: ''M'fa'', ''Mfaa'', ''Mfa'', ''Mfoa''Roman Adrian Cybriwsky, ''Capital Cities around the World: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture'', ABC-CLI ...

Protocol, South Africa, Cuba and Angola formally accepted

UN Security Council Resolution 435 outlining a blueprint for Namibian independence. The protocol envisioned a phased withdrawal of Cuban forces from Angola over a two-year period, set 1 April 1989 as the date for the resolution's implementation and planned to reduce South African forces in Namibia to 1,500 by June 1989. The resolution established UNTAG, approving a report by the Secretary-General and outlining its objective: "the withdrawal of South Africa's illegal administration from Namibia and the transfer of power to the people of Namibia with the assistance of the United Nations". Resolution 435 authorised a total of 7,500 military personnel as UNTAG's upper limit.

It was not until 1988 that South Africa agreed to implement the resolution, signing the

Tripartite Accord (an agreement between Angola, Cuba and South Africa) at

UN headquarters

The United Nations is headquartered in Midtown Manhattan, New York City, United States, and the complex has served as the official headquarters of the United Nations since its completion in 1951. It is in the Turtle Bay, Manhattan, Turtle Bay neig ...

in New York City. The accord recommended that 1 April 1989 be set as the date for implementation of Resolution 435, and was affirmed by the Security Council on 16 January 1989. As Hearn noted, "The first characteristic of peacekeeping is that the consent of the disputants must be secured before a force is deployed". With the accord in place (principally with South Africa), UNTAG was then formally established in accordance with

Resolution 632 on 16 February 1989.

The key participants in the UN process were the South African government (represented in Namibia by the Administrator General) and the UN. Hearn wrote that South Africa had a "desire for a smooth transition"; this resulted in negotiations occurring locally (between the Special Representative and the Administrator General), directly with the South African government in Pretoria and at the UN (via the Secretary General and Security Council). The outcome of these negotiations with South Africa included draft electoral laws (enabling free and fair elections) and the disbanding of the Koevoet force. The elections were carried out by the South African Administrator General, under UN supervision. The UNTAG operation ultimately involved over 100 countries, the highest ever for a UN operation. The UN had a high level of credibility, and were recognised as the legitimate body to bring independence to Namibia.

Australian political context

In the ''

'', author

David Horner

David Murray Horner, (born 12 March 1948) is an Australian military historian and academic.

Early life and military career

Horner was born in Adelaide, South Australia, on 12 March 1948. He was raised in a military household—his father, Mur ...

stated that the Australian government led by

Robert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of ''Hrōþ, Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory ...

was loath to criticise South Africa during the 1950s. At that time Australia generally opposed anti-colonial movements (which were often supported by the Soviets or China), believing them part of a worldwide communist offensive. Indeed, as late as 1961 Australia (and Britain) abstained from a vote to condemn South Africa in the UN.

It was not until 1962 that Australia voted for a UN resolution condemning South Africa for its actions in South-West Africa, a change in policy led by External Affairs Minister

Garfield Barwick

Sir Garfield Edward John Barwick, (22 June 190313 July 1997) was an Australian judge who was the seventh and longest serving Chief Justice of Australia, in office from 1964 to 1981. He had earlier been a Liberal Party politician, serving as a ...

. Initially in opposition, until he was

Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

Gough Whitlam

Edward Gough Whitlam (11 July 191621 October 2014) was the 21st prime minister of Australia, serving from 1972 to 1975. The longest-serving federal leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1967 to 1977, he was notable for being the he ...

was a vocal advocate of independence for Namibia. Over the following two decades, Australia played a small (but significant) role in supporting Namibian independence. Political leaders from both benches of Parliament, including Prime Ministers Whitlam and

Malcolm Fraser

John Malcolm Fraser (; 21 May 1930 – 20 March 2015) was an Australian politician who served as the 22nd prime minister of Australia from 1975 to 1983, holding office as the leader of the Liberal Party of Australia.

Fraser was raised on hi ...

, were active internationally in their support of independence for Namibia while in office. As a result, Australia was involved in the UN process almost from the start. In 1972 Australia voted in favour of a UN trust fund, and two years later it was elected to the UN Council for Namibia. Australia pledged support for UNTAG at the inception of the UN plan for Namibia with Resolution 435 in September 1978, and made an important contribution to UN deliberations about Namibia while a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council in 1985–1986.

Behind the scenes, the composition of the force Australia would contribute was not agreed in principle until late 1978; options discussed at the time were a logistic force and an

infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and marine i ...

battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions are ...

group. By October 1978 Prime Minister Fraser had publicly stated that he wanted to send a

peacekeeping

Peacekeeping comprises activities intended to create conditions that favour lasting peace. Research generally finds that peacekeeping reduces civilian and battlefield deaths, as well as reduces the risk of renewed warfare.

Within the United N ...

force to Namibia; however, this was not broadly supported. A November 1978 article in ''

The Bulletin'' claimed that the Defence Department was "dead against" a commitment, and in January 1979 ''

The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was fo ...

'' and ''

The Canberra Times

''The Canberra Times'' is a daily newspaper in Canberra, Australia, which is published by Australian Community Media. It was founded in 1926, and has changed ownership and format several times.

History

''The Canberra Times'' was launched in ...

'' reported that Fraser,

Andrew Peacock

Andrew Sharp Peacock (13 February 193916 April 2021) was an Australian politician and diplomat. He served as a cabinet minister and went on to become leader of the Liberal Party on two occasions (1983–1985 and 1989–1990), leading the par ...

(Foreign Affairs) and

Jim Killen

Sir Denis James "Jim" Killen, (23 November 1925 – 12 January 2007) was an Australian politician and a Liberal Party member of the Australian House of Representatives from December 1955 to August 1983, representing the Division of Moreton in Q ...

(Defence) were "involved in a row" over the plan. The following month, a Cabinet submission stated that the UN proposal had a "reasonable prospect" of success, and Cabinet approved the commitment of an engineer force of 250 officers and men and a national headquarters and support element of 50 on 19 February. Horner noted that there was very little criticism of this decision in the press at the time, and the decision was accepted without question.

After leaving government, Fraser continued to play an important role in international relations with respect to independence for Namibia. In 1985, he chaired UN hearings in New York on the role of multinationals in South Africa and Namibia. Fraser also co-chaired the

Commonwealth Eminent Persons Group Several Eminent Persons Groups, abbreviated to EPG, have been founded by the Commonwealth of Nations.

1985 Eminent Persons Group

The first EPG was established at the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting 1985, held in Nassau. It was tasked to ...

from 1985 to 1986, campaigning for an end to apartheid in South Africa.

Bob Hawke

Robert James Lee Hawke (9 December 1929 – 16 May 2019) was an Australian politician and union organiser who served as the 23rd prime minister of Australia from 1983 to 1991, holding office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (A ...

's government continued the policy of the Fraser and Whitlam governments to support independence for Namibia. In the ''Official History'', Horner stated that Australian peacekeeping "blossomed" after Gareth Evans was appointed Foreign Minister in September 1988; Evans reconfirmed Australia's willingness to participate in UNTAG in October 1988, a month after his appointment. Horner also said that the commitment was "unusual" because it occurred a decade after the government's initial decision to participate in February 1979. After more than 10 years of consideration, the government reconfirmed its commitment of a force of 300 engineers to Namibia on 2 March 1989.

There were many concerns about the size of the commitment and its risks. Before the deployment, Prime Minister Hawke said in Parliament that Namibia was a "very large and important commitment" comprising "almost half of the Army's construction engineering capability". He went on to say, "our effort in Namibia will be the largest peacekeeping commitment in which this country has ever participated. It may also be the most difficult". Unlike the commitment of soldiers to

Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

over 20 years earlier, the deployment to Namibia had

bipartisan

Bipartisanship, sometimes referred to as nonpartisanship, is a political situation, usually in the context of a two-party system (especially those of the United States and some other western countries), in which opposing political parties find co ...

support.

Prior to the deployment, South African authorities threatened to veto the involvement of Australian peacekeeping troops because of doubts about their impartiality. This followed the establishment by the Australian Government of a Special Assistance Program for South Africans and Namibians (SAPSAN) in 1986 to assist South Africans and Namibians disadvantaged by apartheid. The focus of SAPSAN was on education and training for the people of South Africa and Namibia, and some humanitarian assistance had also been provided. A total of $11.9 million was spent under SAPSAN from 1986 to 1990.

In the ''Official History'', Horner described the Australian deployment to Namibia as a "vital mission": the first major deployment of troops to a war zone since the Vietnam War. In 1988 Australia had only 13 military personnel deployed on multinational peacekeeping operations, and with few exceptions the number of Australians committed to such activities had changed little in over 40 years (since the

Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

). The successful deployment of over 600 engineers to Namibia in 1989 and 1990 was pivotal in changing Australia's approach to peacekeeping, paving the way for much-larger contingents sent to

Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailand t ...

,

Rwanda

Rwanda (; rw, u Rwanda ), officially the Republic of Rwanda, is a landlocked country in the Great Rift Valley of Central Africa, where the African Great Lakes region and Southeast Africa converge. Located a few degrees south of the Equator ...

,

Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constituti ...

and

East Timor

East Timor (), also known as Timor-Leste (), officially the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste, is an island country in Southeast Asia. It comprises the eastern half of the island of Timor, the exclave of Oecusse on the island's north-weste ...

. The deployment of a significant force to Namibia profoundly affected Australia's defence and foreign policies.

The Australian contingent and UNTAG

Command

UNTAG was a large operation, with nearly 8,000 men and women deployed to Namibia from more than 120 countries to assist the process. The military force numbered approximately 4,500, and was commanded by Lieutenant General

Dewan Prem Chand

Lieutenant General Dewan Prem Chand, PVSM (14 June 1916 – 3 November 2003) was an Indian Army officer. He served as Force Commander of United Nations peacekeeping missions in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Cyprus, Namibia and Zimbabwe.

...

of India; the main military UNTAG Headquarters was in

Windhoek

Windhoek (, , ) is the capital and largest city of Namibia. It is located in central Namibia in the Khomas Highland plateau area, at around above sea level, almost exactly at the country's geographical centre. The population of Windhoek in 20 ...

, Namibia's capital and largest city. The commanders of the Australian contingents were Colonels Richard D. Warren (1ASC) and John A. Crocker (2ASC). Other senior appointments included the contingent seconds-in-command,

Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

s Kevin Pippard (1ASC) and

Ken Gillespie

Lieutenant General Kenneth James Gillespie (born 28 June 1952) is a retired senior officer in the Australian Army. Gillespie served as Vice Chief of the Defence Force from 2005 until 2008, then Chief of Army from 2008 until his retirement in J ...

(2ASC), and the officers commanding the

17th Construction Squadron,

Major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

s David Crago (1ASC) and Brendan Sowry (2ASC).

Mission and role of UNTAG

UNTAG's mission was to monitor the ceasefire and troop withdrawals, to preserve law and order in Namibia and to supervise elections for the new government. In the ''Official History'', Horner described it as "an extremely complex mission".

The role of UNTAG was to assist the Special Representative of the Secretary General (SRSG), Martti Ahtisaari, in overseeing free and fair elections in Namibia for a

Constituent Assembly

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

. The elections were to be carried out by the South African Administrator General, under UN supervision and control, and this Assembly would then draw up a constitution for an independent Namibia. UNTAG was tasked with assisting the SRSG in ensuring that all hostile acts ceased; South African troops were confined to base, and ultimately withdrawn; discriminatory laws were repealed, and political prisoners released; Namibian refugees were permitted to return (when they were known as returnees); intimidation was prevented, and law and order maintained.

UNTAG was the first instance of a large-scale, multidimensional operation where the military element supported the work of other components concerned with border surveillance: monitoring the reduction and removal of the South African military presence; organising the return of Namibian exiles; supervising voter registration and preparing, observing, and certifying the results of national elections.

Role of Australian contingent

The role of the Australian force was broad for an Army engineering unit, requiring the unit to "provide combat and logistic engineer support to UNTAG"; this included the UN civilian and military components. Its role included construction, field engineering and (initially) deployment as infantry.

Prime Minister Hawke said in Parliament at the time that "the settlement of the long and complex issue of Namibian independence is an important international event. It is an event in which Australia has played, and will continue to play, a substantial part ... Namibia is a large, arid, sparsely populated and underdeveloped country which has been a war zone for many years. Our engineers will build roads, bridges, airstrips and camps for UNTAG. They will have the very serious task of clearing mines which have been laid by the various contending forces along the border between Angola and Namibia".

Organisation and composition of contingents

The Australian force was structured as follows:

* A Headquarters (Chief Engineer ASC UNTAG) with operations, works, accommodations, communications, finance, logistics and personnel cells

* A Construction Squadron group based on the

17th Construction Squadron (

Royal Australian Engineers

The Royal Australian Engineers (RAE) is the military engineering corps of the Australian Army (although the word corps does not appear in their name or on their badge). The RAE is ranked fourth in seniority of the corps of the Australian Army, be ...

) with two construction troops (the 8th and 9th Troops), the 14th Field Troop, a Resources Troop, a

Plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae exclud ...

Troop and the attached

Royal Australian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers

The Royal Corps of Australian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (RAEME; pronounced Raymee) is a corps of the Australian Army that has responsibility for the maintenance and recovery of all Army electrical and mechanical equipment. RAEME has mem ...

Workshop

There were two contingents, each of which contained over three hundred soldiers and deployed for about six months:

* 1ASC consisted of 304 members, and was principally drawn from the 17th Construction Squadron, the Workshop and the 14th Field Troop from the 7th Field Squadron in Brisbane. The contingents also included soldiers from the

Royal Australian Corps of Signals

The Royal Australian Corps of Signals (RASigs) is one of the 'arms' (combat support corps) of the Australian Army. It is responsible for installing, maintaining, and operating all types of telecommunications equipment and information systems. The m ...

,

Royal Australian Army Pay Corps

The Royal Australian Army Pay Corps (RAAPC) is a Corps of the Australian Army. Its role is to provide financial advice and assistance to the Australian Army.

History

The Australian Army Pay Corps (AAPC) was originally formed on 21 September 1 ...

,

Australian Army Legal Corps

The Australian Army Legal Corps (AALC) consists of Regular and Reserve commissioned officers that provide specific legal advice to commanders and general legal advice to all ranks. They must be admitted to practice as Australian Legal Practit ...

,

Royal Australian Corps of Military Police

The Royal Australian Corps of Military Police (RACMP) is a corps within the Australian Army. Previously known as the Australian Army Provost Corps, it was formed on 3 April 1916 as the ANZAC Provost Corps. It is responsible for battlefield traff ...

,

Royal Australian Corps of Transport

The Royal Australian Corps of Transport (RACT) is a corps within the Australian Army. The RACT is ranked tenth in seniority of the corps of the Australian Army, and is the most senior logistics corps. It was formed on 1 June 1973 as an amalgam ...

,

Royal Australian Army Ordnance Corps

The Royal Australian Army Ordnance Corps (RAAOC) is the Corps within the Australian Army concerned with supply and administration, as well as the demolition and disposal of explosives and salvage of battle-damaged equipment. The Corps contains ...

,

Australian Army Catering Corps

The Australian Army Catering Corps (AACC) is the corps within the Australian Army that is responsible for preparing and serving of meals. The corps was established on 12 March 1943.

See also

* Combat Ration One Man

* Field ration

* Field Ratio ...

and the

Royal Australian Army Medical Corps

The Royal Australian Army Medical Corps (RAAMC) is the branch of the Australian Army responsible for providing medical care to Army personnel. The AAMC was formed in 1902 through the amalgamation of medical units of the various Australian coloni ...

.

* 2ASC consisted of 309 personnel, with members of 78 different units. The second contingent included the 15th Field Troop from the 18th Field Squadron in

Townsville

Townsville is a city on the north-eastern coast of Queensland, Australia. With a population of 180,820 as of June 2018, it is the largest settlement in North Queensland; it is unofficially considered its capital. Estimated resident population, 3 ...

, fourteen members of the

Corps of Royal New Zealand Engineers

The Corps of Royal New Zealand Engineers is the administrative corps of the New Zealand Army responsible for military engineering. The role of the Engineers is to assist in maintaining friendly forces' mobility, deny freedom of movement to the ene ...

(RNZE), five

Australian Army Reserve

The Australian Army Reserve is a collective name given to the reserve units of the Australian Army. Since the Federation of Australia in 1901, the reserve military force has been known by many names, including the Citizens Forces, the Citizen ...

(ARES) members and one

Royal Australian Air Force

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = RAAF Anniversary Commemoration ...

officer (

Flight Lieutenant

Flight lieutenant is a junior commissioned rank in air forces that use the Royal Air Force (RAF) system of ranks, especially in Commonwealth countries. It has a NATO rank code of OF-2. Flight lieutenant is abbreviated as Flt Lt in the India ...

Craig Forster). The New Zealand engineers (under

Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

Jed Shirley) were spread throughout the squadron. The second contingent also included a detachment from the

Royal Australian Corps of Military Police

The Royal Australian Corps of Military Police (RACMP) is a corps within the Australian Army. Previously known as the Australian Army Provost Corps, it was formed on 3 April 1916 as the ANZAC Provost Corps. It is responsible for battlefield traff ...

, led by Sergeant Tim Dewar.

In addition to the military force, a number of other Australians served with UNTAG (including 25 observers from the

Australian Electoral Commission

The Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) is the independent federal agency in charge of organising, conducting and supervising federal Australian elections, by-elections and referendums.

Responsibilities

The AEC's main responsibility is to ...

). For the duration of the deployment, the

Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) is the department of the Australian federal government responsible for foreign policy and relations, international aid (using the branding Australian Aid), consular services and trade and inv ...

and Defence had agreed to jointly fund a temporary Australian Liaison Office in Windhoek manned by two DFAT personnel and headed by

Nick Warner

Nicholas Peter Warner, (born 22 May 1950) is an Australian diplomat, intelligence official, public servant, and the Director-General of the Office of National Intelligence since 20 December 2018.

Warner served as the director-general of the ...

.

Force preparation and deployment

First ten years

Australian Army

The Australian Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of Australia, a part of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Australian Air Force. The Army is commanded by the Chief of Army (Austral ...

involvement in UNTAG was formalised in February 1979 by Cabinet, which approved the plan to commit the 17th Construction Squadron, Royal Australian Engineers and Workshop as the main force for deployment. The squadron was to be supplemented by a Field Troop and by members posted from other units throughout the Army, bringing the squadron to a deployment strength of 275. A headquarters was to be formed, supporting the Chief Engineer at the UNTAG Military Headquarters. The total strength of the force was to be over 300 of all ranks, in what was known as Plan Witan. The unit had been placed on eight weeks' notice in July 1978, which was reduced to a week's notice to move in February 1979.

There was no agreement (or settlement) between South Africa and SWAPO, so an order to move was never issued. The ''Official History'' noted, "as the weeks passed the unit found it difficult to continue training because all its vehicles, equipment and plant were either in boxes or in a state ready for transhipment". The notice to move reverted to 30 days in June and pushed out to 42 days in September 1979, when the unit was formally released from standby. The notice to move was increased to 60 days in March 1982, and 75 days in November 1986. In July 1987, all remaining specific readiness requirements were removed.

Activation

Horner wrote that the government had been following the course of negotiations, "but in view of the history of false alarms they were not inclined to react until Angola, Cuba and South Africa signed the protocol in Geneva" in August 1988. Two weeks later the UN wrote, asking Australia to reconfirm its previous commitment; within a month, Cabinet reaffirmed the commitment of a decade earlier.

Chief of the Defence Force (CDF)

General Peter Gration then placed the unit on 28 days' notice to move.

After the notice was reactivated, detailed planning recommenced (essentially from scratch). Changes made to the organisation of the force approved ten years earlier were only minor. After many years of notice, there was still skepticism that the deployment would ever occur. The government and army were cautious about the timing of the commitment of funds; significant funding was only released in late 1988, a few months before deployment. The squadron's equipment deficiencies were valued at $16 million, and there was a need to buy $700,000 of equipment immediately. The UN initially estimated the cost of the entire operation at $US1 billion, equivalent to its own budget. The reluctance to commit funds ultimately reduced training of the deployed forces; Senator

Jo Vallentine

Josephine Vallentine (born 30 May 1946) is an Australian peace activist and politician, a former senator for Western Australia. She entered the Senate on 1 July 1985 after election as a member of the Nuclear Disarmament Party but sat as an ind ...

said in Parliament that the Namibia operation nearly fell apart due to a lack of advance funding, and Senator

Jocelyn Newman

Jocelyn Margaret Newman (née Mullett; 8 July 1937 – 1 April 2018) was an Australian politician. She was a Senator for Tasmania for 15 years, and a minister in the Howard Government.

Political career

Jocelyn Margaret Mullett was born in M ...

called it disgraceful. The UN General Assembly did not approve the UNTAG budget until 1 March 1989, less than two weeks before the advance party deployed and after the deployment of the start-up team. Gration authorised Operation Picaresque on 3 March 1989. In addition to a lack of funds, there was little intelligence on Namibia; the region was "generally unknown to the Australian public, the policy-makers and to the troops and civilians who deployed there".

Buildup and deployment

The first staff were posted to the new contingent headquarters at

Holsworthy Barracks

Holsworthy Barracks is an Australian Army military barracks, located in the Heathcote National Park in Holsworthy approximately from the central business district, in south-western Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. The barracks is part of th ...

in September 1988. At the same time, Major J.J. Hutchings was deployed as liaison officer to UN HQ in New York. In October, the CDF formally tasked the

Chief of the General Staff The Chief of the General Staff (CGS) is a post in many armed forces (militaries), the head of the military staff.

List

* Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (United States)

* Chief of the General Staff (Abkhazia)

* Chief of General Staff (Afg ...

(CGS) to raise, train, equip and support the force for Namibia. By December the two units comprising 1ASC had been raised from more than thirty different units of the Australian Army, and were being trained and prepared for deployment. Equipment, vehicles and weapons were procured, transferred from across the army and prepared at Moorebank; this included the painting of all vehicles and major equipment items in UN livery and packing items for transport to Namibia. During the buildup it was recognised that the families required support during the deployment, and Network 17 was established to support the mostly Sydney-based soldiers' and officers' families.

Hutchings was sent to Namibia as a member of the start-up team, arriving in Windhoek on 19 February 1989. Warren attended the contingent commanders' briefing at UN HQ from 22 to 24 February 1989, and then flew with Prem Chand to Frankfurt, West Germany to meet the other senior members of UNTAG.

The 1ASC advance party, comprising 36 officers and men, were deployed by USAF

C-5 Galaxy

The Lockheed C-5 Galaxy is a large military transport aircraft designed and built by Lockheed, and now maintained and upgraded by its successor, Lockheed Martin. It provides the United States Air Force (USAF) with a heavy intercontinental-ran ...

via

RAAF Learmonth

RAAF Base Learmonth, also known as Learmonth Airport , is a joint use Royal Australian Air Force base and civil airport. It is located near the town of Exmouth on the north-west coast of Western Australia. RAAF Base Learmonth is one of the RAA ...

and

Diego Garcia

Diego Garcia is an island of the British Indian Ocean Territory, a disputed overseas territory of the United Kingdom. It is a militarised atoll just south of the equator in the central Indian Ocean, and the largest of the 60 small islands o ...

to Windhoek. They arrived at 2:00 pm on 11 March 1989 and were met by Australian Ambassador to South Africa Colin MacDonald, Warren and Hutchings. The 17th Construction Squadron advance party of ten deployed by road to

Grootfontein

, nickname =

, settlement_type = City

, motto = Fons Vitæ

, image_skyline = Grootfontein grass.jpg

, imagesize = 300px

, image_caption =

, image_flag =

, flag_si ...

on 13 March 1989. The squadron's advance echelon, comprising 59 personnel (including the 14th Field Troop), arrived by USAF C5 Galaxy at Grootfontein on 14 March 1989. The remainder of 1ASC were commended by Prime Minister Bob Hawke at a farewell parade at Holsworthy Barracks on 5 April 1989. The main body then deployed by

RAAF

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = RAAF Anniversary Commemoration ...

Boeing 707

The Boeing 707 is an American, long-range, narrow-body airliner, the first jetliner developed and produced by Boeing Commercial Airplanes.

Developed from the Boeing 367-80 prototype first flown in 1954, the initial first flew on December 20, ...

aircraft on 14 April.

The force deployed with a large quantity of construction and other equipment, including 24

Land Rover

Land Rover is a British brand of predominantly four-wheel drive, off-road capable vehicles, owned by multinational car manufacturer Jaguar Land Rover (JLR), since 2008 a subsidiary of India's Tata Motors. JLR currently builds Land Rovers ...

s, 19

Unimog

The Unimog (, ) is a range of multi-purpose tractors, trucks and lorries that has been produced by Boehringer from 1948 until 1951, and by Daimler Truck (formerly Daimler-Benz, DaimlerChrysler and Daimler AG) since 1951. In the United States and ...

all-terrain vehicles, 26 heavy trucks, 43 trailers, eight bulldozers and a variety of other road-building equipment such as graders, scrapers and rollers. The support workshop added a further 40 vehicles, and over 1,800 tonnes of stores were shipped with the contingent's equipment. There was a total of over 200 wheeled and tracked vehicles and trailers and a large quantity of dangerous cargo (demolition explosives and ammunition). The UN hired the MV ''Mistra'' for the deployment. It departed Sydney on 23 March; the equipment was unloaded at

Walvis Bay

Walvis Bay ( en, lit. Whale Bay; af, Walvisbaai; ger, Walfischbucht or Walfischbai) is a city in Namibia and the name of the bay on which it lies. It is the second largest city in Namibia and the largest coastal city in the country. The c ...

in mid-April, moving by road and rail to the South African Defence Force Logistics Base at Grootfontein.

Operations

Operations Safe Passage and Piddock

By 31 March, 14th Field Troop had completed its mine-awareness training; only

Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

Stephen Alexander and five others remained at

Oshakati

Oshakati is a town in northern Namibia. It is the regional capital of the Oshana Region and one of Namibia's largest places.

Oshakati was founded in July 1966 and proclaimed a town in 1992. The town was used as a base of operations by the S ...

, the main SADF base in the north of the country. During the early hours of 1 April an SADF aircraft began dropping flares, and

mortar rounds landed near the base. This signalled the start of an intense period of conflict, and Alexander's team was quickly withdrawn to Grootfontein. What had occurred was the infiltration of a large number of PLAN combatants (about 1,600), re-entering Namibia from Angola. Accounts differed, but Hearn stated that all of those interviewed at the time made it clear that "they did not enter Namibia for war, but to seek out the UN". Reuters reported that SWAPO demanded the right to establish bases in Namibia. The large size of the PLAN forces and the very small number of deployed UN forces (less than 1,000 at the time) meant that the UN had very little intelligence, and was unable to respond in force. Sitkowski wrote that the UN should have been informed about the high probability of SWAPO infiltration, but this did not occur. The Australians were the first to know about the incursion, but they only found out informally via church sources at the Pastoral Centre (the accommodations for headquarters staff).

The UN had only two police observers in the north of the country at the time, and the South African government pressured the UN to allow its forces to leave their bases and respond. On 1 April the SRSG authorised the SADF to leave their bases, and they responded in force. By 5 April the UN reported that it only had 300 troops in the north of the country, including 97 Australians. On 7 April Reuters reported that

Louis Pienaar

Louis Alexander Pienaar (23 June 1926 – 5 November 2012) was a South African lawyer and diplomat. He was the last white Administrator of South-West Africa, from 1985 through Namibian independence in 1990. Pienaar later served as a minister in ...

had assured safe passage out of the war-torn north of the country if fighting ceased, and had called on SWAPO to surrender to the police; he also warned that if they did not respond, "the police will have no other option than to pursue you with all means at their disposal". Reuters reported that 73 SWAPO guerillas were killed on 8 April, 34 in a single action. It was later estimated that over the three-week period following the incursion 251 PLAN combatants were killed, with the loss of 21 members of the SADF and other security forces.

The SWAPO incursion became a complex political issue, and led to a week of tense negotiations. The UN considered emergency airlifts to bring more peacekeepers into the territory, and the United States offered aid. On 9 April 1989 an agreement was reached at Mount Etjo (the Mount Etjo Declaration), calling for the rapid deployment of UNTAG forces and outlining a withdrawal procedure for PLAN soldiers (Operation Safe Passage) under which they would leave the country. Operation Piddock was the name for the Australian part of the operation. Horner wrote that if UNTAG were to play any role in ending the fighting, it was obvious that the Australians would be the key component. This was complex, and required authorisation from Gration and

Defence Minister

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in som ...

Kim Beazley

Kim Christian Beazley (born 14 December 1948) is an Australian former politician and diplomat. He was leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) and leader of the opposition from 1996 to 2001 and 2005 to 2006, having previously been a cabinet ...

for Australian troops to supervise the withdrawal of insurgent forces. It required the Australian Army engineers and British signallers to work as infantry, manning border and internal-assembly points. At the time, these were the only units which could be redeployed quickly to northern Namibia.

The aim of the operation was to facilitate the withdrawal of PLAN combatants. South African Foreign Minister

Pik Botha

Roelof Frederik "Pik" Botha, (27 April 1932 – 12 October 2018) was a South African politician who served as the country's foreign minister in the last years of the apartheid era, the longest-serving in South African history. Known as a liber ...

confined all South African troops to their base for 60 hours, allowing SWAPO guerillas to leave the country unhindered. Nine assembly points were established by the UN, with up to twelve soldiers and five military observers at each. Six of the assembly points (APs) were led by Australians: Captain Richard Bradshaw (contingent signals officer) at AP Charlie (

Ruacana

Ruacana is a town in Omusati Region, northern Namibia and the district capital of the Ruacana electoral constituency. It is located on the border with Angola on the river Kunene. The town is known for the picturesque Ruacana Falls nearby, and fo ...

), Sergeant Kerry Ponting (Squadron workshop) at AP Foxtrot (

Oshikango

Oshikango is a former village in northern Namibia and since 2004 part of the town of Helao Nafidi, although it still maintained its own village council for a number of years. ''Oshikango'' is still the name of the border post with Angola and the ...

), Captain Mark Hender (Squadron Operations Officer) at AP Juliet (Okankolo), Lieutenant Stephen Alexander (Field troop commander) at AP Delta (Beacon 7, west of Oshikango), Lieutenant Mark Broome (Plant Troop Officer) AP Bravo (Ruacana) and Lieutenant Pat Sowry (Liaison Officer) AP Kilo (

Oshikuku

Oshikuku is a town in Omusati Region in the north of Namibia. It is the district capital of Oshikuku Constituency.

Oshikuku features a secondary school, Nuuyoma Senior Secondary School, and a hospital. Its neighbouring villages are Outapi, El ...

). Most of the assembly points had intense media scrutiny. The intention of the operation was for PLAN combatants to assemble at these points. They would then be escorted across the border north to the 16th parallel to their bases of confinement, but the operation was unsuccessful. Very few PLAN combatants passed through these points; for the most part, they withdrew across the border by walking independently. It was estimated that 200 to 400 PLAN members remained in Namibia, absorbed into the local community. Agreement was subsequently reached in late April that the SADF personnel be restricted to their bases from 26 April; in effect, hostilities ended after that date.

This was a stressful time for Australian soldiers deployed to these checkpoints. The South Africans were determined to intimidate the UN forces, and SWAPO casualties occurred in the immediate vicinity of several checkpoints. The South Africans set up in force immediately adjacent to many checkpoints, pointed machine guns at the Australians and demanded that they hand over SWAPO soldiers who had surrendered. The Australian and British soldiers were outnumbered and out-gunned. Despite the fact that only nine SWAPO appeared at the points, the operation was a political success. Lieutenant Colonel Neil Donaldson, commander of the British contingent, said that "the world press showed Australian and British soldiers standing up to a bunch of South African bullies". Crocker said that the fact that the Australian soldiers completed this operation without any casualties was a tribute to the "training standards of the Australian Army and perhaps, a bit of good luck". The conclusion of Operation Piddock meant that the Australians were able to begin their engineering tasks.

Return of refugees

The UN plan required that all exiled Namibians be given the opportunity to return to their country in time to participate in the electoral process. This was implemented by the

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is a United Nations agency mandated to aid and protect refugees, forcibly displaced communities, and stateless people, and to assist in their voluntary repatriation, local integrati ...

(UNHCR), supported by a number of other UN agencies and programmes. In Namibia, the

Council of Churches in Namibia

The Council of Churches in Namibia (CCN) is an ecumenical organisation in Namibia. Its member churches together represent 1.5 million people, 90% of the population of Namibia. It is a member of the Fellowship of Christian Councils in Southern Afric ...

(CCN) was UNHCR's implementing partner. Most returning Namibians returned from Angola; many came from Zambia, and a small number came from 46 other countries after the proclamation of a general amnesty. The logistics of managing the returnees was largely delegated to the Australian contingent.

Three air and three land entry points were established, as well as five reception centres. Four centres were designed by Namibia Consult Incorporated under the directorship of

Klaus Dierks

Karl Otto Ludwig Klaus DierksJoe Pütz, Heidi von Egidy, Perri Caplan: ''Political Who's Who of Namibia''. Magus, Windhoek 1989, Namibia series Vol. 1, ISBN 0-620-10225-X, pp. 203, 204 (19 February 1936 – 17 March 2005) was a German-born Nam ...

, and constructed by the Australian contingent. The centres were located at Dobra, Mariabronn (near Grootfontein) and at

Ongwediva

Ongwediva is a town in the Oshana Region in the north of Namibia. It is the district capital of the Ongwediva electoral constituency. it had 27,000 inhabitants and covered 4,102 hectares of land. Ongwediva has seven churches, two private sch ...

and Engela in

Ovamboland

Ovamboland, also referred to as Owamboland, was a Bantustan in South West Africa (present-day Namibia), intended by the apartheid government to be a self-governing homeland for the Ovambo people.

The term originally referred to the parts of ...

. They were administered under the auspices of the Repatriation, Resettlement and Reconstruction Committee of the CCN.

The 8th Construction Troop (under Lieutenant Geoff Burchell) constructed a camp and managed the reception centre at Engela, less than from the Angolan border; the 9th Construction Troop (under Lieutenant Andrew Stanner) constructed a similar camp and managed the reception centre at Ongwediva. The SADF continued attempts to intimidate the Australians and disrupt operations, but their actions had little effect. In late April an SADF aircraft dropped flares at night over the 9th Construction Troop base at Ongwediva, and explosions (possibly mortar rounds) were heard nearby.

Security, services and logistics at the reception centres were provided by the military component of UNTAG, and a number of secondary reception centres were also established. The movement of returnees through the centres was quick, and the repatriation programme was very successful; a UN official report stated that the psychological impact of the return of so many exiles was perceptible throughout the country. There were some problems reported in the north, where ex-Koevoet elements searched villages for SWAPO returnees; however, the UN reported that this was kept under constant surveillance by UNTAG's police monitors. By the end of the process, 42,736 Namibians had been returned from exile.

Accommodation and other works

For the remainder of its deployment, the first contingent focused most of its efforts on providing accommodations for electoral centres and police stations. These were typically manned by only two or three police (or civilian) electoral staff and were almost always in small, remote villages. Buildings were leased, a large number of

caravans purchased and deployed and prefabricated buildings constructed in about 50 locations. Much of this was done by the Resources Troop (under Lieutenant Stuart Graham), centrally controlled by squadron construction officer Captain Shane Miller.

The largest plant task undertaken during the deployment was the construction of an airstrip at

Opuwo

Opuwo is the capital of the Kunene Region in north-western Namibia. The town is situated about 720 km north-northwest from the capital Windhoek, and has a population of 20,000. It is the commercial hub of the Kunene Region.

Economy and inf ...

. The squadron commander, Major David Crago, described how the road network in Namibia was better than expected; in retrospect, the squadron brought too much heavy road-making equipment. The squadron deployed 20 members of the Plant Troop (under Captain Nigel Catchlove) to Opuwo. Over a period of four months, Sergeant Ken Roma constructed an all-weather airstrip in one of the most remote parts of Namibia.

Force rotation

The first contingent returned to Australia in September and October 1989, Warren reporting that he was "amazed that none of his men was killed or seriously hurt during the tour of duty". Planning for the second contingent had begun as soon as the first contingent had deployed. Colonel John Crocker was appointed as the contingent commander, and was given the task of raising the force. Unlike the first contingent, which had been built around the 17th Construction Squadron and had maintained that unit's structure, the second contingent had to be built from scratch. It deployed to Namibia between September and early October 1989.

Election preparation and Operation Poll Gallop

The security environment in Namibia changed in the lead-up to the election, including violence in Namibia and an increase in fighting between FAPLA and UNITA troops across the border in Angola. Horner wrote that the Australian contingent was not directly involved in "dealing with the violence", but the increased violence changed the nature of the mission. It was initially envisioned that the military component of UNTAG would only provide communications and logistic support to the election. In September the role was broadened to include hundreds of electoral monitors, and in October (after detailed planning and reconnaissance of all polling stations) the Australian contingent deployed a ready-reaction force. At the same time the 15th Field Troop (under Lieutenant Brent Maddock) was deployed, making the first entry into a live minefield by Australian troops since the Vietnam War.

Operation Poll Gallop was the name given to the largely logistic operation to support the Namibian elections. Activities began with 1ASC from May 1989 onward, but became the primary task for 2ASC:

* Service support: Support was provided to approximately 500 electoral centres and police stations through the siting and erection of permanent (or portable) accommodations and the provision of essential services. UNTAG deployed over 350 polling stations; the Australian contingent constructed and provided support (including sanitary facilities) at 120 stations in the northern areas of

Kaokoland

Kaokoland was an administrative unit and a ''bantustan'' in northern South West Africa (now Namibia). Established during the apartheid era, it was intended to be a self-governing homeland of the OvaHimba, but an actual government was never e ...

,

Ovamboland

Ovamboland, also referred to as Owamboland, was a Bantustan in South West Africa (present-day Namibia), intended by the apartheid government to be a self-governing homeland for the Ovambo people.

The term originally referred to the parts of ...

and West

Hereroland

Hereroland was the first bantustan in South West Africa (present day Namibia), intended by the apartheid government to be a self-governing homeland for the Herero people. It was set up in 1968.

Hereroland, like other homelands in South Wes ...

.

* Construction engineering: This included the construction, modification or upgrade of UNTAG working and living accommodations, provision of essential services (power, water and air-traffic-control facilities) and the maintenance and upgrade of roads.

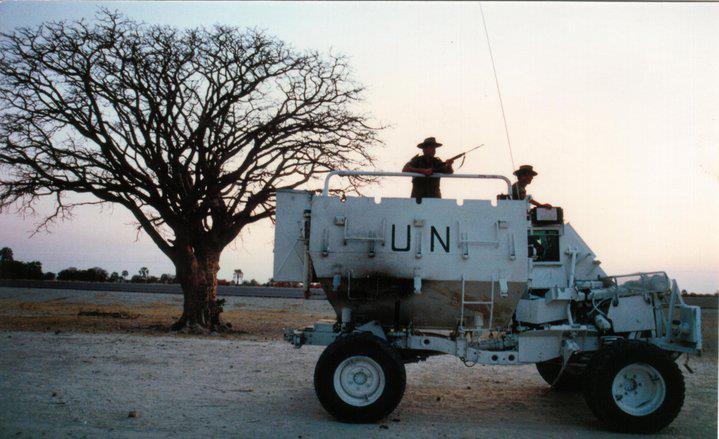

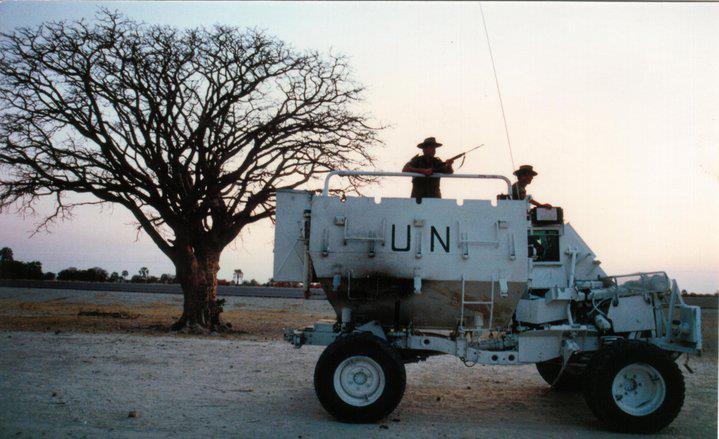

* Ready Reaction Force: The squadron formed a reinforced Field Troop (50 soldiers) in

Buffel

The Buffel (English: ''Buffalo'') is an infantry mobility vehicle used by the South African Defence Force during the South African Border War. The Buffel was also used as an armoured fighting vehicle and proved itself in this role. It replaced ...

mine-proof vehicles as a ready-reaction force at Ondangwa, deploying to the 15 most-sensitive locations in Ovamboland and practising actions to stabilise a hostile (but not violent) situation in which Australians might be involved. On two occasions during the November 1989 election, the ASC Ready-Reaction Force was used to disperse rioters.

* Australian military electoral monitors: The Australian contingent provided a team of thirty monitors headed by Lieutenant Colonel Peter Boyd, legal officer for the second contingent.

Colonel John Crocker, commander of 2ASC, wrote: "For much of the mission, but particularly during the lead-up to the election, all members of the ASC worked, often well away from their bases, in a security environment which at best could be termed uneasy and on many occasions was definitely hazardous. The deeply divided political factions, which included thousands of de-mobilised soldiers from both sides, had easy access to weapons including machine guns and grenades. This situation resulted in a series of violent incidents including assassinations and reprisal killings which culminated in the deaths of 11 civilians and the wounding of 50 others in street battles in the northern town of Oshakati just before the election". Land mines and unexploded ammunition continued to cause injury and death; even during the week of the election, there were incidents.

Post-election and return to Australia

After the election, the contingent was able to focus almost exclusively on construction tasks. In addition to ongoing maintenance, these included taking over barracks and accommodations from the SADF and twelve non-UNTAG tasks in support of the local community as nation-building exercises. These included:

* Opuwo airfield: The major task was the completion of the airfield upgrade at Opuwo begun by the first contingent. A detachment from Captain Kurt Heidecker's Plant Troop, supported by a section from 9th Construction Troop, worked over Christmas to complete these works (which included resurfacing and shaping the runway, drainage and installing culverts).

* Andara Catholic Mission hydroelectric plant: A team under Lieutenant Nick Rowntree upgraded a 900-metre supply channel for the

Andara

Andara is a village in Mukwe Constituency in the Kavango East region of north-eastern Namibia. Located east of Rundu, it is inhabited primarily by the Hambukushu people.

Founding of the Catholic mission

Catholic fathers of the organization Mi ...

hydroelectric plant.

* Classrooms in Tsumeb:

Sapper

A sapper, also called a pioneer (military), pioneer or combat engineer, is a combatant or soldier who performs a variety of military engineering duties, such as breaching fortifications, demolitions, bridge-building, laying or clearing minefie ...

s from the rear of the squadron constructed a number of classrooms for an Anglican school in a black neighbourhood in

Tsumeb

, nickname =

, settlement_type = City

, motto = ''Glück Auf'' (German language, German for ''Good luck'')

, image_skyline = Welcome to tsumeb.jpg

, imagesize =

, image_caption ...

with funds provided by the Australian Liaison Office.

Other tasks carried out by the squadron included Operation Make Safe, which took place in February and March 1990. The Field Troop conducted a reconnaissance of 10 known minefields, repaired perimeter fences and installed signs.

The contingent began preparations for its return to Australia in December 1989. In January 1990 new works stopped, manning of forward bases was reduced and stores and equipment were packed and prepared for sea. The Australian forces returned in four sorties on chartered commercial aircraft, the first departing Namibia on 6 February. The contingent's equipment loaded aboard the MV ''Kwang Tung'', which left Walvis Bay on 22 February. The withdrawal included support from Australian logistics experts, a psychologist to conduct end-of-tour debriefings and a finance officer. The last demolition task was undertaken at Ondangwa on 25 March, and the last elements of the rear party left Namibia on 9 April 1990. During the deployment there were no fatalities; although at least 10 soldiers were treated for malaria, there were few serious injuries.

Commendations and Honour Distinction award

A number of governments linked the award of the

Nobel Peace Prize