The United States detonated two

atomic bombs

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

over the Japanese cities of

Hiroshima and

Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest Cities of Japan, city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole Nanban trade, port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hi ...

on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the only use of nuclear weapons in armed conflict so far.

In the final year of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, the

Allies prepared for a costly

invasion of the Japanese mainland. This undertaking was preceded by a

conventional and firebombing campaign that devastated 64 Japanese cities. The

war in the European theatre concluded when Germany

surrendered on 8 May 1945, and the Allies turned their full attention to the

Pacific War. By July 1945, the Allies'

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

had produced two types of atomic bombs: "

Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) is the codename for the type of nuclear bomb the United States detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons ever used in warfare, the fir ...

", a

plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibi ...

implosion-type nuclear weapon

Nuclear weapon designs are physical, chemical, and engineering arrangements that cause the physics package of a nuclear weapon to detonate. There are three existing basic design types:

* pure fission weapons, the simplest and least technically ...

; and "

Little Boy

"Little Boy" was the type of atomic bomb dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 during World War II, making it the first nuclear weapon used in warfare. The bomb was dropped by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress ''Enola Gay'' p ...

", an

enriched uranium

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (238U ...

gun-type fission weapon

Gun-type fission weapons are fission-based nuclear weapons whose design assembles their fissile material into a supercritical mass by the use of the "gun" method: shooting one piece of sub-critical material into another. Although this is someti ...

. The

509th Composite Group

The 509th Composite Group (509 CG) was a unit of the United States Army Air Forces created during World War II and tasked with the operational deployment of nuclear weapons. It conducted the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, in ...

of the

United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

was trained and equipped with the specialized

Silverplate

Silverplate was the code reference for the United States Army Air Forces' participation in the Manhattan Project during World War II. Originally the name for the aircraft modification project which enabled a B-29 Superfortress bomber to drop a ...

version of the

Boeing B-29 Superfortress, and deployed to

Tinian

Tinian ( or ; old Japanese name: 天仁安島, ''Tenian-shima'') is one of the three principal islands of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. Together with uninhabited neighboring Aguiguan, it forms Tinian Municipality, one of the ...

in the

Mariana Islands. The Allies called for the unconditional surrender of the

Imperial Japanese armed forces

The Imperial Japanese Armed Forces (IJAF) were the combined military forces of the Japanese Empire. Formed during the Meiji Restoration in 1868,"One can date the 'restoration' of imperial rule from the edict of 3 January 1868." p. 334. they ...

in the

Potsdam Declaration

The Potsdam Declaration, or the Proclamation Defining Terms for Japanese Surrender, was a statement that called for the surrender of all Japanese armed forces during World War II. On July 26, 1945, United States President Harry S. Truman, Uni ...

on 26 July 1945, the alternative being "prompt and utter destruction". The Japanese government ignored the ultimatum.

The consent of the United Kingdom was obtained for the bombing, as was required by the

Quebec Agreement, and orders were issued on 25 July by

General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

Thomas Handy, the acting

Chief of Staff of the United States Army

The chief of staff of the Army (CSA) is a statutory position in the United States Army held by a general officer. As the highest-ranking officer assigned to serve in the Department of the Army, the chief is the principal military advisor and ...

, for atomic bombs to be used against Hiroshima,

Kokura

is an ancient castle town and the center of Kitakyushu, Japan, guarding the Straits of Shimonoseki between Honshu and Kyushu with its suburb Moji. Kokura is also the name of the penultimate station on the southbound San'yō Shinkansen li ...

,

Niigata, and Nagasaki. These targets were chosen because they were large urban areas that also held militarily significant facilities. On 6 August, a Little Boy was dropped on Hiroshima, to which

Prime Minister Suzuki reiterated the Japanese government's commitment to ignore the Allies' demands and fight on. Three days later, a Fat Man was dropped on Nagasaki. Over the next two to four months, the

effects of the atomic bombings killed between 90,000 and 146,000 people in Hiroshima and 39,000 and 80,000 people in Nagasaki; roughly half occurred on the first day. For months afterward, many people continued to die from the effects of burns,

radiation sickness, and injuries, compounded by illness and malnutrition. Though Hiroshima had a sizable military garrison, most of the dead were civilians.

Japan surrendered to the Allies on 15 August, six days after the

Soviet Union's declaration of war and the bombing of Nagasaki. The Japanese government signed the

instrument of surrender on 2 September, effectively

ending the war. Scholars have extensively studied the effects of the bombings on the social and political character of subsequent world history and

popular culture

Popular culture (also called mass culture or pop culture) is generally recognized by members of a society as a set of practices, beliefs, artistic output (also known as, popular art or mass art) and objects that are dominant or prevalent in a ...

, and there is still

much debate concerning the ethical and legal justification for the bombings. Supporters believe that the atomic bombings were necessary to bring a swift end to the war with minimal casualties; critics dispute how the Japanese government was brought to surrender, and highlight the moral and ethical implications of nuclear weapons and the deaths caused to civilians.

Background

Pacific War

In 1945, the

Pacific War between the

Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of Japan, 1947 constitu ...

and the

Allies entered its fourth year. Most Japanese military units fought fiercely, ensuring that the Allied victory would come at an enormous cost. The 1.25 million battle casualties incurred in total by the United States in

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

included both

military personnel

Military personnel are members of the state's armed forces. Their roles, pay, and obligations differ according to their military branch (army, navy, marines, air force, space force, and coast guard), rank (officer, non-commissioned officer, or ...

killed in action and

wounded in action

Wounded in Action (WIA) describes combatants who have been wounded while fighting in a combat zone during wartime, but have not been killed. Typically, it implies that they are temporarily or permanently incapable of bearing arms or continuing ...

. Nearly one million of the casualties occurred during the last year of the war, from June 1944 to June 1945. In December 1944, American battle casualties hit an all-time monthly high of 88,000 as a result of the German

Ardennes Offensive

The Battle of the Bulge, also known as the Ardennes Offensive, was the last major German offensive campaign on the Western Front during World War II. The battle lasted from 16 December 1944 to 28 January 1945, towards the end of the war in ...

. America's reserves of manpower were running out. Deferments for groups such as agricultural workers were tightened, and there was consideration of drafting women. At the same time, the public was becoming war-weary, and demanding that long-serving servicemen be sent home.

In the Pacific, the Allies

returned to the Philippines,

recaptured Burma, and

invaded Borneo. Offensives were undertaken to reduce the Japanese forces remaining in

Bougainville,

New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torr ...

and the Philippines. In April 1945, American forces

landed on Okinawa, where heavy fighting continued until June. Along the way, the ratio of Japanese to American casualties dropped from five to one in the Philippines to two to one on Okinawa. Although some Japanese soldiers were

taken prisoner, most fought until they were killed or committed

suicide. Nearly 99 percent of the 21,000 defenders of

Iwo Jima were killed. Of the 117,000 Okinawan and Japanese troops defending

Okinawa

is a prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest city ...

in April to June 1945, 94 percent were killed; 7,401 Japanese soldiers surrendered, an unprecedentedly large number.

As the Allies advanced towards Japan, conditions became steadily worse for the Japanese people. Japan's merchant fleet declined from 5,250,000

gross tons

Gross tonnage (GT, G.T. or gt) is a nonlinear measure of a ship's overall internal volume. Gross tonnage is different from gross register tonnage. Neither gross tonnage nor gross register tonnage should be confused with measures of mass or weig ...

in 1941 to 1,560,000 tons in March 1945, and 557,000 tons in August 1945. Lack of raw materials forced the Japanese war economy into a steep decline after the middle of 1944. The civilian economy, which had slowly deteriorated throughout the war, reached disastrous levels by the middle of 1945. The loss of shipping also affected the fishing fleet, and the 1945 catch was only 22 percent of that in 1941. The 1945 rice harvest was the worst since 1909, and hunger and malnutrition became widespread. U.S. industrial production was overwhelmingly superior to Japan's. By 1943, the U.S. produced almost 100,000 aircraft a year, compared to Japan's production of 70,000 for the entire war. In February 1945, Prince

Fumimaro Konoe advised

Emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereignty, sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), ...

Hirohito that defeat was inevitable, and urged him to abdicate.

Preparations to invade Japan

Even before the

surrender of Nazi Germany on 8 May 1945, plans were underway for the largest operation of the Pacific War,

Operation Downfall, the Allied invasion of Japan. The operation had two parts:

Operation Olympic

Operation Downfall was the proposed Allied plan for the invasion of the Japanese home islands near the end of World War II. The planned operation was canceled when Japan surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ...

and

Operation Coronet. Set to begin in October 1945, Olympic involved a series of landings by the U.S.

Sixth Army intended to capture the southern third of the southernmost main Japanese island,

Kyūshū. Operation Olympic was to be followed in March 1946 by Operation Coronet, the capture of the

Kantō Plain

The is the largest plain in Japan, and is located in the Kantō region of central Honshū. The total area of 17,000 km2 covers more than half of the region extending over Tokyo, Saitama Prefecture, Kanagawa Prefecture, Chiba Prefecture, ...

, near Tokyo on the main Japanese island of

Honshū by the U.S.

First

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

,

Eighth and

Tenth Armies, as well as a

Commonwealth Corps

The Commonwealth Corps was the name given to a proposed British Commonwealth army formation, which was scheduled to take part in the planned Allied invasion of Japan during 1945 and 1946. The corps was never formed, however, as the Japanese surr ...

made up of Australian, British and Canadian divisions. The target date was chosen to allow for Olympic to complete its objectives, for troops to be redeployed from Europe, and the

Japanese winter to pass.

Japan's geography made this invasion plan obvious to the Japanese; they were able to predict the Allied invasion plans accurately and thus adjust their defensive plan,

Operation Ketsugō, accordingly. The Japanese planned an all-out defense of Kyūshū, with little left in reserve for any subsequent defense operations. Four veteran divisions were withdrawn from the

Kwantung Army

''Kantō-gun''

, image = Kwantung Army Headquarters.JPG

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Kwantung Army headquarters in Hsinking, Manchukuo

, dates = April ...

in

Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

in March 1945 to strengthen the forces in Japan, and 45 new divisions were activated between February and May 1945. Most were immobile formations for coastal defense, but 16 were high quality mobile divisions. In all, there were 2.3 million

Japanese Army troops prepared to defend the home islands, backed by a

civilian militia of 28 million men and women. Casualty predictions varied widely, but were extremely high. The Vice Chief of the

Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff

The was the highest organ within the Imperial Japanese Navy. In charge of planning and operations, it was headed by an Admiral headquartered in Tokyo.

History

Created in 1893, the Navy General Staff took over operational (as opposed to adminis ...

,

Vice Admiral Takijirō Ōnishi, predicted up to 20 million Japanese deaths.

On 15 June 1945, a study by the Joint War Plans Committee, who provided planning information to the

Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, that advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and the ...

, estimated that Olympic would result in 130,000 to 220,000 U.S. casualties, with U.S. dead in the range from 25,000 to 46,000. Delivered on 15 June 1945, after insight gained from the Battle of Okinawa, the study noted Japan's inadequate defenses due to the very effective sea blockade and the American firebombing campaign. The

Chief of Staff of the United States Army

The chief of staff of the Army (CSA) is a statutory position in the United States Army held by a general officer. As the highest-ranking officer assigned to serve in the Department of the Army, the chief is the principal military advisor and ...

,

General of the Army George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Chief of Staff of the US Army under Pre ...

, and the Army Commander in Chief in the Pacific, General of the Army

Douglas MacArthur, signed documents agreeing with the Joint War Plans Committee estimate.

The Americans were alarmed by the Japanese buildup, which was accurately tracked through

Ultra

adopted by British military intelligence in June 1941 for wartime signals intelligence obtained by breaking high-level encrypted enemy radio and teleprinter communications at the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park. ' ...

intelligence.

Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Henry L. Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 – October 20, 1950) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. Over his long career, he emerged as a leading figure in U.S. foreign policy by serving in both Republican and D ...

was sufficiently concerned about high American estimates of probable casualties to commission his own study by

Quincy Wright and

William Shockley

William Bradford Shockley Jr. (February 13, 1910 – August 12, 1989) was an American physicist and inventor. He was the manager of a research group at Bell Labs that included John Bardeen and Walter Brattain. The three scientists were jointl ...

. Wright and Shockley spoke with Colonels

James McCormack

James McCormack, Jr. (8 November 1910 – 3 January 1975) was a United States Army officer who served in World War II, and was later the first Director of Military Applications of the United States Atomic Energy Commission.

A 1932 graduate of ...

and

Dean Rusk

David Dean Rusk (February 9, 1909December 20, 1994) was the United States Secretary of State from 1961 to 1969 under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, the second-longest serving Secretary of State after Cordell Hull from the F ...

, and examined casualty forecasts by

Michael E. DeBakey and Gilbert Beebe. Wright and Shockley estimated the invading Allies would suffer between 1.7 and 4 million casualties in such a scenario, of whom between 400,000 and 800,000 would be dead, while Japanese fatalities would have been around 5 to 10 million.

Marshall began contemplating the use of a weapon that was "readily available and which assuredly can decrease the cost in American lives":

poison gas

Many gases have toxic properties, which are often assessed using the LC50 (median lethal dose) measure. In the United States, many of these gases have been assigned an NFPA 704 health rating of 4 (may be fatal) or 3 (may cause serious or perman ...

. Quantities of

phosgene,

mustard gas,

tear gas

Tear gas, also known as a lachrymator agent or lachrymator (), sometimes colloquially known as "mace" after the early commercial aerosol, is a chemical weapon that stimulates the nerves of the lacrimal gland in the eye to produce tears. In ...

and

cyanogen chloride

Cyanogen chloride is a highly toxic chemical compound with the formula CNCl. This linear, triatomic pseudohalogen is an easily condensed colorless gas. More commonly encountered in the laboratory is the related compound cyanogen bromide, a room-te ...

were moved to

Luzon

Luzon (; ) is the largest and most populous island in the Philippines. Located in the northern portion of the Philippines archipelago, it is the economic and political center of the nation, being home to the country's capital city, Manila, as ...

from stockpiles in Australia and New Guinea in preparation for Operation Olympic, and MacArthur ensured that

Chemical Warfare Service

The Chemical Corps is the branch of the United States Army tasked with defending against chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) weapons. The Chemical Warfare Service was established on 28 June 1918, combining activities that un ...

units were trained in their use. Consideration was also given to using

biological weapons

A biological agent (also called bio-agent, biological threat agent, biological warfare agent, biological weapon, or bioweapon) is a bacterium, virus, protozoan, parasite, fungus, or toxin that can be used purposefully as a weapon in bioterrorism ...

against Japan.

Air raids on Japan

While the United States had developed plans for an air campaign against Japan prior to the Pacific War, the capture of Allied bases in the western Pacific in the first weeks of the conflict meant that this offensive did not begin until mid-1944 when the long-ranged

Boeing B-29 Superfortress became ready for use in combat.

Operation Matterhorn

Operation Matterhorn was a military operation of the United States Army Air Forces in World War II for the strategic bombing of Japanese forces by B-29 Superfortresses based in India and China. Targets included Japan itself, and Japanese bases ...

involved India-based B-29s staging through bases around

Chengdu

Chengdu (, ; simplified Chinese: 成都; pinyin: ''Chéngdū''; Sichuanese pronunciation: , Standard Chinese pronunciation: ), alternatively romanized as Chengtu, is a sub-provincial city which serves as the capital of the Chinese pro ...

in China to make a series of raids on strategic targets in Japan. This effort failed to achieve the strategic objectives that its planners had intended, largely because of logistical problems, the bomber's mechanical difficulties, the vulnerability of Chinese staging bases, and the extreme range required to reach key Japanese cities.

Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

Haywood S. Hansell determined that

Guam

Guam (; ch, Guåhan ) is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost point and territory of the United States (reckoned from the geographic cent ...

,

Tinian

Tinian ( or ; old Japanese name: 天仁安島, ''Tenian-shima'') is one of the three principal islands of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. Together with uninhabited neighboring Aguiguan, it forms Tinian Municipality, one of the ...

, and

Saipan in the

Mariana Islands would better serve as B-29 bases, but they were in Japanese hands. Strategies were shifted to accommodate the air war, and the

islands were captured between June and August 1944. Air bases were developed, and B-29 operations commenced from the Marianas in October 1944. These bases were easily resupplied by cargo ships. The

XXI Bomber Command

The XXI Bomber Command was a unit of the Twentieth Air Force in the Mariana Islands for strategic bombing during World War II.

The command was established at Smoky Hill Army Air Field, Kansas on 1 March 1944. After a period of organization an ...

began missions against Japan on 18 November 1944. The early attempts to bomb Japan from the Marianas proved just as ineffective as the China-based B-29s had been. Hansell continued the practice of conducting so-called high-altitude

precision bombing

Precision bombing refers to the attempted aerial bombing of a target with some degree of accuracy, with the aim of maximising target damage or limiting collateral damage. An example would be destroying a single building in a built up area causing ...

, aimed at key industries and transportation networks, even after these tactics had not produced acceptable results. These efforts proved unsuccessful due to logistical difficulties with the remote location, technical problems with the new and advanced aircraft, unfavorable weather conditions, and enemy action.

Hansell's successor,

Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

Curtis LeMay

Curtis Emerson LeMay (November 15, 1906 – October 1, 1990) was an American Air Force general who implemented a controversial strategic bombing campaign in the Pacific theater of World War II. He later served as Chief of Staff of the U.S. Air ...

, assumed command in January 1945 and initially continued to use the same precision bombing tactics, with equally unsatisfactory results. The attacks initially targeted key industrial facilities but much of the Japanese manufacturing process was carried out in small workshops and private homes. Under pressure from

United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

(USAAF) headquarters in Washington, LeMay changed tactics and decided that low-level

incendiary raids against Japanese cities were the only way to destroy their production capabilities, shifting from precision bombing to

area bombardment

In military aviation, area bombardment (or area bombing) is a type of aerial bombardment in which bombs are dropped over the general area of a target. The term "area bombing" came into prominence during World War II.

Area bombing is a form of st ...

with incendiaries. Like most

strategic bombing during World War II, the aim of the air offensive against Japan was to destroy the enemy's war industries, kill or disable civilian employees of these industries, and

undermine civilian morale.

Over the next six months, the XXI Bomber Command under LeMay firebombed 64 Japanese cities. The

firebombing of Tokyo

The was a series of firebombing air raids by the United States Army Air Force during the Pacific campaigns of World War II. Operation Meetinghouse, which was conducted on the night of 9–10 March 1945, is the single most destructive bombing ...

, codenamed ''Operation Meetinghouse'', on 9–10 March killed an estimated 100,000 people and destroyed of the city and 267,000 buildings in a single night. It was the deadliest bombing raid of the war, at a cost of 20 B-29s shot down by flak and fighters. By May, 75 percent of bombs dropped were incendiaries designed to burn down Japan's "paper cities". By mid-June, Japan's six largest cities had been devastated. The end of the

fighting on Okinawa

The , codenamed Operation Iceberg, was a major battle of the Pacific War fought on the island of Okinawa Island, Okinawa by United States Army (USA) and United States Marine Corps (USMC) forces against the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA). The init ...

that month provided airfields even closer to the Japanese mainland, allowing the bombing campaign to be further escalated. Aircraft flying from Allied

aircraft carriers and the

Ryukyu Islands

The , also known as the or the , are a chain of Japanese islands that stretch southwest from Kyushu to Taiwan: the Ōsumi, Tokara, Amami, Okinawa, and Sakishima Islands (further divided into the Miyako and Yaeyama Islands), with Yona ...

also regularly struck targets in Japan during 1945 in preparation for Operation Downfall. Firebombing switched to smaller cities, with populations ranging from 60,000 to 350,000. According to

Yuki Tanaka, the U.S. fire-bombed over a hundred Japanese towns and cities. These raids were devastating.

The Japanese military was unable to stop the Allied attacks and the country's

civil defense preparations proved inadequate. Japanese fighters and anti-aircraft guns had difficulty engaging bombers flying at high altitude. From April 1945, the Japanese interceptors also had to face American fighter escorts based on

Iwo Jima and Okinawa. That month, the

Imperial Japanese Army Air Service

The Imperial Japanese Army Air Service (IJAAS) or Imperial Japanese Army Air Force (IJAAF; ja, 大日本帝國陸軍航空部隊, Dainippon Teikoku Rikugun Kōkūbutai, lit=Greater Japan Empire Army Air Corps) was the aviation force of the Im ...

and

Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service stopped attempting to intercept the air raids to preserve fighter aircraft to counter the expected invasion. By mid-1945 the Japanese only occasionally scrambled aircraft to intercept individual B-29s conducting reconnaissance sorties over the country, to conserve supplies of fuel. In July 1945, the Japanese had of

avgas stockpiled for the invasion of Japan. About had been consumed in the home islands area in April, May and June 1945. While the Japanese

military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

decided to resume attacks on Allied bombers from late June, by this time there were too few operational fighters available for this change of tactics to hinder the Allied air raids.

Atomic bomb development

The discovery of

nuclear fission by German chemists

Otto Hahn

Otto Hahn (; 8 March 1879 – 28 July 1968) was a German chemist who was a pioneer in the fields of radioactivity and radiochemistry. He is referred to as the father of nuclear chemistry and father of nuclear fission. Hahn and Lise Meitner ...

and

Fritz Strassmann

Friedrich Wilhelm Strassmann (; 22 February 1902 – 22 April 1980) was a German chemist who, with Otto Hahn in December 1938, identified the element barium as a product of the bombardment of uranium with neutrons. Their observation was the ke ...

in 1938, and its theoretical explanation by

Lise Meitner and

Otto Frisch, made the development of an atomic bomb a theoretical possibility. Fears that a

German atomic bomb project would develop atomic weapons first, especially among scientists who were refugees from Nazi Germany and other fascist countries, were expressed in the

Einstein–Szilard letter in 1939. This prompted preliminary research in the United States in late 1939. Progress was slow until the arrival of the British

MAUD Committee report in late 1941, which indicated that only 5 to 10 kilograms of isotopically enriched

uranium-235

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exi ...

were needed for a bomb instead of tons of natural uranium and a

neutron moderator like

heavy water.

The 1943

Quebec Agreement merged the nuclear weapons projects of the United Kingdom and Canada,

Tube Alloys

Tube Alloys was the research and development programme authorised by the United Kingdom, with participation from Canada, to develop nuclear weapons during the Second World War. Starting before the Manhattan Project in the United States, the ...

and the

Montreal Laboratory, with the

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, under the direction of Major General

Leslie R. Groves, Jr., of the

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

, colors =

, anniversaries = 16 June (Organization Day)

, battles =

, battles_label = Wars

, website =

, commander1 = ...

. Groves appointed

J. Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist. A professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley, Oppenheimer was the wartime head of the Los Alamos Laboratory and is oft ...

to organize and head the project's

Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and operated by the University of California during World War II. Its mission was to design and build the first atomic bombs. Ro ...

in

New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ke ...

, where bomb design work was carried out. Two types of bombs were eventually developed, both named by

Robert Serber

Robert Serber (March 14, 1909 – June 1, 1997) was an American physicist who participated in the Manhattan Project. Serber's lectures explaining the basic principles and goals of the project were printed and supplied to all incoming scientific st ...

.

Little Boy

"Little Boy" was the type of atomic bomb dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 during World War II, making it the first nuclear weapon used in warfare. The bomb was dropped by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress ''Enola Gay'' p ...

was a

gun-type fission weapon

Gun-type fission weapons are fission-based nuclear weapons whose design assembles their fissile material into a supercritical mass by the use of the "gun" method: shooting one piece of sub-critical material into another. Although this is someti ...

that used

uranium-235

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exi ...

, a rare

isotope

Isotopes are two or more types of atoms that have the same atomic number (number of protons in their nuclei) and position in the periodic table (and hence belong to the same chemical element), and that differ in nucleon numbers (mass numb ...

of uranium separated at the

Clinton Engineer Works

The Clinton Engineer Works (CEW) was the production installation of the Manhattan Project that during World War II produced the enriched uranium used in the 1945 bombing of Hiroshima, as well as the first examples of reactor-produced pluton ...

at

Oak Ridge, Tennessee. The other, known as a

Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) is the codename for the type of nuclear bomb the United States detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons ever used in warfare, the fir ...

device, was a more powerful and efficient, but more complicated,

implosion-type nuclear weapon

Nuclear weapon designs are physical, chemical, and engineering arrangements that cause the physics package of a nuclear weapon to detonate. There are three existing basic design types:

* pure fission weapons, the simplest and least technically ...

that used

plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibi ...

created in

nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat fr ...

s at

Hanford, Washington

Hanford was a small agricultural community in Benton County, Washington, United States. It and White Bluffs were depopulated in 1943 in order to make room for the nuclear production facility known as the Hanford Site. The town was located in what ...

.

There was a

Japanese nuclear weapon program

The Japanese program to develop nuclear weapons was conducted during World War II. Like the German nuclear weapons program, it suffered from an array of problems, and was ultimately unable to progress beyond the laboratory stage before the ato ...

, but it lacked the human, mineral and financial resources of the Manhattan Project, and never made much progress towards developing an atomic bomb.

Preparations

Organization and training

The

509th Composite Group

The 509th Composite Group (509 CG) was a unit of the United States Army Air Forces created during World War II and tasked with the operational deployment of nuclear weapons. It conducted the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, in ...

was constituted on 9 December 1944, and activated on 17 December 1944, at

Wendover Army Air Field, Utah, commanded by

Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge o ...

Paul Tibbets

Paul Warfield Tibbets Jr. (23 February 1915 – 1 November 2007) was a brigadier general in the United States Air Force. He is best known as the aircraft captain who flew the B-29 Superfortress known as the ''Enola Gay'' (named after his moth ...

.

Tibbets was assigned to organize and command a

combat group to develop the means of delivering an atomic weapon against targets in Germany and Japan. Because the flying squadrons of the group consisted of both bomber and transport aircraft, the group was designated as a "composite" rather than a "bombardment" unit. Working with the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos, Tibbets selected Wendover for his training base over

Great Bend, Kansas

Great Bend is a city in and the county seat of Barton County, Kansas, United States. It is named for its location at the point where the course of the Arkansas River bends east then southeast. As of the 2020 census, the population of the ci ...

, and

Mountain Home, Idaho, because of its remoteness. Each bombardier completed at least 50 practice drops of inert or conventional explosive

pumpkin bomb

Pumpkin bombs were conventional aerial bombs developed by the Manhattan Project and used by the United States Army Air Forces against Japan during World War II. It was a close replication of the Fat Man plutonium bomb with the same ballistic an ...

s and Tibbets declared his group combat-ready.

On 5 April 1945, the

code name Operation Centerboard was assigned. The officer responsible for its allocation in the

War Department War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War (1789–1947)

See also

* War Office, a former department of the British Government

* Ministry of defence

* Ministry of War

* Ministry of Defence

* D ...

's Operations Division was not cleared to know any details of it. The first bombing was later codenamed Operation Centerboard I, and the second, Operation Centerboard II.

The 509th Composite Group had an authorized strength of 225 officers and 1,542 enlisted men, almost all of whom eventually deployed to Tinian. In addition to its authorized strength, the 509th had attached to it on Tinian 51 civilian and military personnel from

Project Alberta

Project Alberta, also known as Project A, was a section of the Manhattan Project which assisted in delivering the first nuclear weapons in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II.

Project Alberta was formed in March 1 ...

, known as the 1st Technical Detachment. The 509th Composite Group's

393d Bombardment Squadron 393rd or 393d may refer to:

*393d Bomb Squadron (393 BS) is part of the 509th Bomb Wing at Whiteman Air Force Base, Missouri

*393d Bombardment Group, inactive United States Air Force unit

*393d Bombardment Squadron (Medium) (1942), inactive United ...

was equipped with 15

Silverplate

Silverplate was the code reference for the United States Army Air Forces' participation in the Manhattan Project during World War II. Originally the name for the aircraft modification project which enabled a B-29 Superfortress bomber to drop a ...

B-29s. These aircraft were specially adapted to carry nuclear weapons, and were equipped with

fuel-injected engines, Curtiss Electric

reversible-pitch propellers, pneumatic actuators for rapid opening and closing of bomb bay doors and other improvements.

The ground support echelon of the 509th Composite Group moved by rail on 26 April 1945, to its port of embarkation at

Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest regio ...

, Washington. On 6 May the support elements sailed on the SS ''Cape Victory'' for the Marianas, while group materiel was shipped on the SS ''Emile Berliner''. The ''Cape Victory'' made brief port calls at

Honolulu

Honolulu (; ) is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, which is in the Pacific Ocean. It is an unincorporated county seat of the consolidated City and County of Honolulu, situated along the southeast coast of the island ...

and

Eniwetok

Enewetak Atoll (; also spelled Eniwetok Atoll or sometimes Eniewetok; mh, Ānewetak, , or , ; known to the Japanese as Brown Atoll or Brown Island; ja, ブラウン環礁) is a large coral atoll of 40 islands in the Pacific Ocean and with i ...

but the passengers were not permitted to leave the dock area. An advance party of the air echelon, consisting of 29 officers and 61 enlisted men, flew by C-54 to

North Field on Tinian, between 15 and 22 May. There were also two representatives from Washington, D.C.,

Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

Thomas Farrell, the deputy commander of the Manhattan Project, and

Rear Admiral William R. Purnell

Rear Admiral William Reynolds Purnell (6 September 1886 – 3 March 1955) was an officer in the United States Navy who served in World War I and World War II. A 1908 graduate of the United States Naval Academy, he captained destroyers during Wo ...

of the Military Policy Committee, who were on hand to decide higher policy matters on the spot. Along with Captain

William S. Parsons, the commander of Project Alberta, they became known as the "Tinian Joint Chiefs".

Choice of targets

In April 1945, Marshall asked Groves to nominate specific targets for bombing for final approval by himself and Stimson. Groves formed a Target Committee, chaired by himself, that included Farrell, Major John A. Derry,

Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge o ...

William P. Fisher, Joyce C. Stearns and

David M. Dennison from the USAAF; and scientists

John von Neumann

John von Neumann (; hu, Neumann János Lajos, ; December 28, 1903 – February 8, 1957) was a Hungarian-American mathematician, physicist, computer scientist, engineer and polymath. He was regarded as having perhaps the widest cove ...

,

Robert R. Wilson

Robert Rathbun Wilson (March 4, 1914 – January 16, 2000) was an American physicist known for his work on the Manhattan Project during World War II, as a sculptor, and as an architect of the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab), ...

and

William Penney

William George Penney, Baron Penney, (24 June 19093 March 1991) was an English mathematician and professor of mathematical physics at the Imperial College London and later the rector of Imperial College London. He had a leading role in the d ...

from the Manhattan Project. The Target Committee met in Washington on 27 April; at Los Alamos on 10 May, where it was able to talk to the scientists and technicians there; and finally in Washington on 28 May, where it was briefed by Tibbets and

Commander Frederick Ashworth from Project Alberta, and the Manhattan Project's scientific advisor,

Richard C. Tolman.

The Target Committee nominated five targets:

Kokura

is an ancient castle town and the center of Kitakyushu, Japan, guarding the Straits of Shimonoseki between Honshu and Kyushu with its suburb Moji. Kokura is also the name of the penultimate station on the southbound San'yō Shinkansen li ...

(now

Kitakyushu), the site of one of Japan's largest munitions plants;

Hiroshima, an embarkation port and industrial center that was the site of a major military headquarters;

Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of T ...

, an urban center for aircraft manufacture, machine tools, docks, electrical equipment and oil refineries;

Niigata, a port with industrial facilities including steel and aluminum plants and an oil refinery; and

Kyoto

Kyoto (; Japanese language, Japanese: , ''Kyōto'' ), officially , is the capital city of Kyoto Prefecture in Japan. Located in the Kansai region on the island of Honshu, Kyoto forms a part of the Keihanshin, Keihanshin metropolitan area along wi ...

, a major industrial center. The target selection was subject to the following criteria:

* The target was larger than in diameter and was an important target in a large city.

* The

blast wave

In fluid dynamics, a blast wave is the increased pressure and flow resulting from the deposition of a large amount of energy in a small, very localised volume. The flow field can be approximated as a lead shock wave, followed by a self-similar sub ...

would create effective damage.

* The target was unlikely to be attacked by August 1945.

These cities were largely untouched during the nightly bombing raids, and the Army Air Forces agreed to leave them off the target list so accurate assessment of the damage caused by the atomic bombs could be made. Hiroshima was described as "an important army depot and port of embarkation in the middle of an urban industrial area. It is a good radar target and it is such a size that a large part of the city could be extensively damaged. There are adjacent hills which are likely to produce a focusing effect which would considerably increase the blast damage. Due to rivers it is not a good

incendiary target."

The Target Committee stated that "It was agreed that psychological factors in the target selection were of great importance. Two aspects of this are (1) obtaining the greatest psychological effect against Japan and (2) making the initial use sufficiently spectacular for the importance of the weapon to be internationally recognized when publicity on it is released.... Kyoto has the advantage of the people being more highly intelligent and hence better able to appreciate the significance of the weapon. Hiroshima has the advantage of being such a size and with possible focussing from nearby mountains that a large fraction of the city may be destroyed. The

Emperor's palace in Tokyo has a greater fame than any other target but is of least strategic value."

, a Japan expert for the

U.S. Army Intelligence Service, was incorrectly said to have prevented the bombing of Kyoto.

In his autobiography, Reischauer specifically refuted this claim:

On 30 May, Stimson asked Groves to remove Kyoto from the target list due to its historical, religious and cultural significance, but Groves pointed to its military and industrial significance. Stimson then approached

President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

about the matter. Truman agreed with Stimson, and Kyoto was temporarily removed from the target list. Groves attempted to restore Kyoto to the target list in July, but Stimson remained adamant. On 25 July,

Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest Cities of Japan, city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole Nanban trade, port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hi ...

was put on the target list in place of Kyoto. It was a major military port, one of Japan's largest shipbuilding and repair centers, and an important producer of naval ordnance.

Proposed demonstration

In early May 1945, the

Interim Committee was created by Stimson at the urging of leaders of the Manhattan Project and with the approval of Truman to advise on matters pertaining to

nuclear energy. During the meetings on 31 May and 1 June, scientist

Ernest Lawrence

Ernest Orlando Lawrence (August 8, 1901 – August 27, 1958) was an American nuclear physicist and winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939 for his invention of the cyclotron. He is known for his work on uranium-isotope separation fo ...

had suggested giving the Japanese a non-combat demonstration.

Arthur Compton later recalled that:

The possibility of a demonstration was raised again in the

Franck Report issued by physicist

James Franck

James Franck (; 26 August 1882 – 21 May 1964) was a German physicist who won the 1925 Nobel Prize for Physics with Gustav Hertz "for their discovery of the laws governing the impact of an electron upon an atom". He completed his doctorate i ...

on 11 June and the Scientific Advisory Panel rejected his report on 16 June, saying that "we can propose no technical demonstration likely to bring an end to the war; we see no acceptable alternative to direct military use." Franck then took the report to Washington, D.C., where the Interim Committee met on 21 June to re-examine its earlier conclusions; but it reaffirmed that there was no alternative to the use of the bomb on a military target.

Like Compton, many U.S. officials and scientists argued that a demonstration would sacrifice the shock value of the atomic attack, and the Japanese could deny the atomic bomb was lethal, making the mission less likely to produce surrender. Allied

prisoners of war might be moved to the demonstration site and be killed by the bomb. They also worried that the bomb might be a failure, as the Trinity test was that of a stationary device, not an air-dropped bomb. In addition, although more bombs were in production, only two would be available at the start of August, and they cost billions of dollars, so using one for a demonstration would be expensive.

Leaflets

For several months, the U.S. had warned civilians of potential air raids by dropping more than 63 million leaflets across Japan. Many Japanese cities suffered terrible damage from aerial bombings; some were as much as 97 percent destroyed. LeMay thought that leaflets would increase the psychological impact of bombing, and reduce the international stigma of area-bombing cities. Even with the warnings,

Japanese opposition to the war remained ineffective. In general, the Japanese regarded the leaflet messages as truthful, with many Japanese choosing to leave major cities. The leaflets caused such concern that the government ordered the arrest of anyone caught in possession of a leaflet.

Leaflet texts were prepared by recent Japanese prisoners of war because they were thought to be the best choice "to appeal to their compatriots".

In preparation for dropping an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, the Oppenheimer-led

Scientific Panel of the Interim Committee decided against a demonstration bomb and against a special leaflet warning. Those decisions were implemented because of the uncertainty of a successful detonation and also because of the wish to maximize

shock in the leadership. No warning was given to Hiroshima that a new and much more destructive bomb was going to be dropped. Various sources gave conflicting information about when the last leaflets were dropped on Hiroshima prior to the atomic bomb.

Robert Jay Lifton wrote that it was 27 July, and Theodore H. McNelly wrote that it was 30 July. The USAAF history noted that eleven cities were targeted with leaflets on 27 July, but Hiroshima was not one of them, and there were no leaflet sorties on 30 July. Leaflet sorties were undertaken on 1 and 4 August. Hiroshima may have been leafleted in late July or early August, as survivor accounts talk about a delivery of leaflets a few days before the atomic bomb was dropped. Three versions were printed of a leaflet listing 11 or 12 cities targeted for firebombing; a total of 33 cities listed. With the text of this leaflet reading in Japanese "...we cannot promise that only these cities will be among those attacked..."

Hiroshima was not listed.

Consultation with Britain and Canada

In 1943, the United States and the United Kingdom signed the

Quebec Agreement, which stipulated that nuclear weapons would not be used against another country without mutual consent. Stimson therefore had to obtain British permission. A meeting of the

Combined Policy Committee, which included one Canadian representative, was held at

the Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense. It was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As a symbol of the U.S. military, the phrase ''The Pentagon'' is often used as a meton ...

on 4 July 1945.

Field Marshal Sir

Henry Maitland Wilson

Field Marshal Henry Maitland Wilson, 1st Baron Wilson, (5 September 1881 – 31 December 1964), also known as Jumbo Wilson, was a senior British Army officer of the 20th century. He saw active service in the Second Boer War and then during the ...

announced that the British government concurred with the use of nuclear weapons against Japan, which would be officially recorded as a decision of the Combined Policy Committee. As the release of information to third parties was also controlled by the Quebec Agreement, discussion then turned to what scientific details would be revealed in the press announcement of the bombing. The meeting also considered what Truman could reveal to

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

, the leader of the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, at the upcoming

Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris P ...

, as this also required British concurrence.

Orders for the attack were issued to General

Carl Spaatz on 25 July under the signature of General

Thomas T. Handy, the acting chief of staff, since Marshall was at the Potsdam Conference with Truman. It read:

That day, Truman noted in his diary that:

Potsdam Declaration

The 16 July success of the

Trinity Test

Trinity was the code name of the first detonation of a nuclear weapon. It was conducted by the United States Army at 5:29 a.m. on July 16, 1945, as part of the Manhattan Project. The test was conducted in the Jornada del Muerto desert abo ...

in the

New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ke ...

desert exceeded expectations. On 26 July, Allied leaders issued the

Potsdam Declaration

The Potsdam Declaration, or the Proclamation Defining Terms for Japanese Surrender, was a statement that called for the surrender of all Japanese armed forces during World War II. On July 26, 1945, United States President Harry S. Truman, Uni ...

, which outlined the terms of surrender for Japan. The declaration was presented as an

ultimatum

An ultimatum (; ) is a demand whose fulfillment is requested in a specified period of time and which is backed up by a threat to be followed through in case of noncompliance (open loop). An ultimatum is generally the final demand in a series ...

and stated that without a surrender, the Allies would attack Japan, resulting in "the inevitable and complete destruction of the Japanese armed forces and just as inevitably the utter devastation of the Japanese homeland". The atomic bomb was not mentioned in the communiqué.

On 28 July, Japanese papers reported that the declaration had been rejected by the Japanese government. That afternoon,

Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

Kantarō Suzuki

Baron was a Japanese general and politician. He was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy, member and final leader of the Imperial Rule Assistance Association and Prime Minister of Japan from 7 April to 17 August 1945.

Biography

Early l ...

declared at a press conference that the Potsdam Declaration was no more than a rehash (''yakinaoshi'') of the

Cairo Declaration, that the government intended to ignore it (''

mokusatsu'', "kill by silence"), and that Japan would fight to the end. The statement was taken by both Japanese and foreign papers as a clear rejection of the declaration. Emperor Hirohito, who was waiting for a Soviet reply to non-committal Japanese peace feelers, made no move to change the government position. Japan's willingness to surrender remained conditional on the preservation of the ''

kokutai

is a concept in the Japanese language translatable as " system of government", "sovereignty", "national identity, essence and character", "national polity; body politic; national entity; basis for the Emperor's sovereignty; Japanese constitu ...

'' (Imperial institution and national

polity), assumption by the Imperial Headquarters of responsibility for disarmament and demobilization, no occupation of the

Japanese Home Islands

The Japanese archipelago (Japanese: 日本列島, ''Nihon rettō'') is a group of 6,852 islands that form the country of Japan, as well as the Russian island of Sakhalin. It extends over from the Sea of Okhotsk in the northeast to the East Chin ...

, Korea or

Formosa, and delegation of the punishment of war criminals to the Japanese government.

At Potsdam, Truman agreed to a request from

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

that Britain be represented when the atomic bomb was dropped.

William Penney

William George Penney, Baron Penney, (24 June 19093 March 1991) was an English mathematician and professor of mathematical physics at the Imperial College London and later the rector of Imperial College London. He had a leading role in the d ...

and

Group Captain Leonard Cheshire

Geoffrey Leonard Cheshire, Baron Cheshire, (7 September 1917 – 31 July 1992) was a highly decorated Royal Air Force (RAF) pilot and group captain during the Second World War, and a philanthropist.

Among the honours Cheshire received as ...

were sent to Tinian, but found that LeMay would not let them accompany the mission. All they could do was send a strongly worded signal to Wilson.

Bombs

The Little Boy bomb, except for the uranium payload, was ready at the beginning of May 1945. There were two uranium-235 components, a hollow cylindrical projectile and a cylindrical target insert. The projectile was completed on 15 June, and the target insert on 24 July. The projectile and eight bomb pre-assemblies (partly assembled bombs without the powder charge and fissile components) left

Hunters Point Naval Shipyard

The Hunters Point Naval Shipyard was a United States Navy shipyard in San Francisco, California, located on of waterfront at Hunters Point in the southeast corner of the city.

Originally, Hunters Point was a commercial shipyard established ...

, California, on 16 July aboard the

cruiser , and arrived on Tinian on 26 July. The target insert followed by air on 30 July, accompanied by Commander

Francis Birch from Project Alberta. Responding to concerns expressed by the 509th Composite Group about the possibility of a B-29 crashing on takeoff, Birch had modified the Little Boy design to incorporate a removable breech plug that would permit the bomb to be armed in flight.

The first

plutonium core, along with its

polonium

Polonium is a chemical element with the symbol Po and atomic number 84. Polonium is a chalcogen. A rare and highly radioactive metal with no stable isotopes, polonium is chemically similar to selenium and tellurium, though its metallic character ...

-

beryllium

Beryllium is a chemical element with the symbol Be and atomic number 4. It is a steel-gray, strong, lightweight and brittle alkaline earth metal. It is a divalent element that occurs naturally only in combination with other elements to form m ...

urchin initiator, was transported in the custody of Project Alberta courier

Raemer Schreiber in a magnesium field carrying case designed for the purpose by

Philip Morrison

Philip Morrison (November 7, 1915 – April 22, 2005) was a professor of physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He is known for his work on the Manhattan Project during World War II, and for his later work in quantum physi ...

. Magnesium was chosen because it does not act as a

neutron reflector

A neutron reflector is any material that reflects neutrons. This refers to elastic scattering rather than to a specular reflection. The material may be graphite, beryllium, steel, tungsten carbide, gold, or other materials. A neutron reflector ...

. The core departed from

Kirtland Army Air Field on a

C-54 transport aircraft of the 509th Composite Group's

320th Troop Carrier Squadron

The 320th Troop Carrier Squadron is an inactive United States Air Force unit. It was activated on 17 December 1944, and inactivated on 19 August 1946 at Roswell Army Air Field, New Mexico. The squadron was later consolidated with the 302d Transp ...

on 26 July, and arrived at North Field 28 July. Three Fat Man high-explosive pre-assemblies, designated F31, F32, and F33, were picked up at Kirtland on 28 July by three B-29s, two from the 393d Bombardment Squadron plus one from the 216th Army Air Force Base Unit, and transported to North Field, arriving on 2 August.

Hiroshima

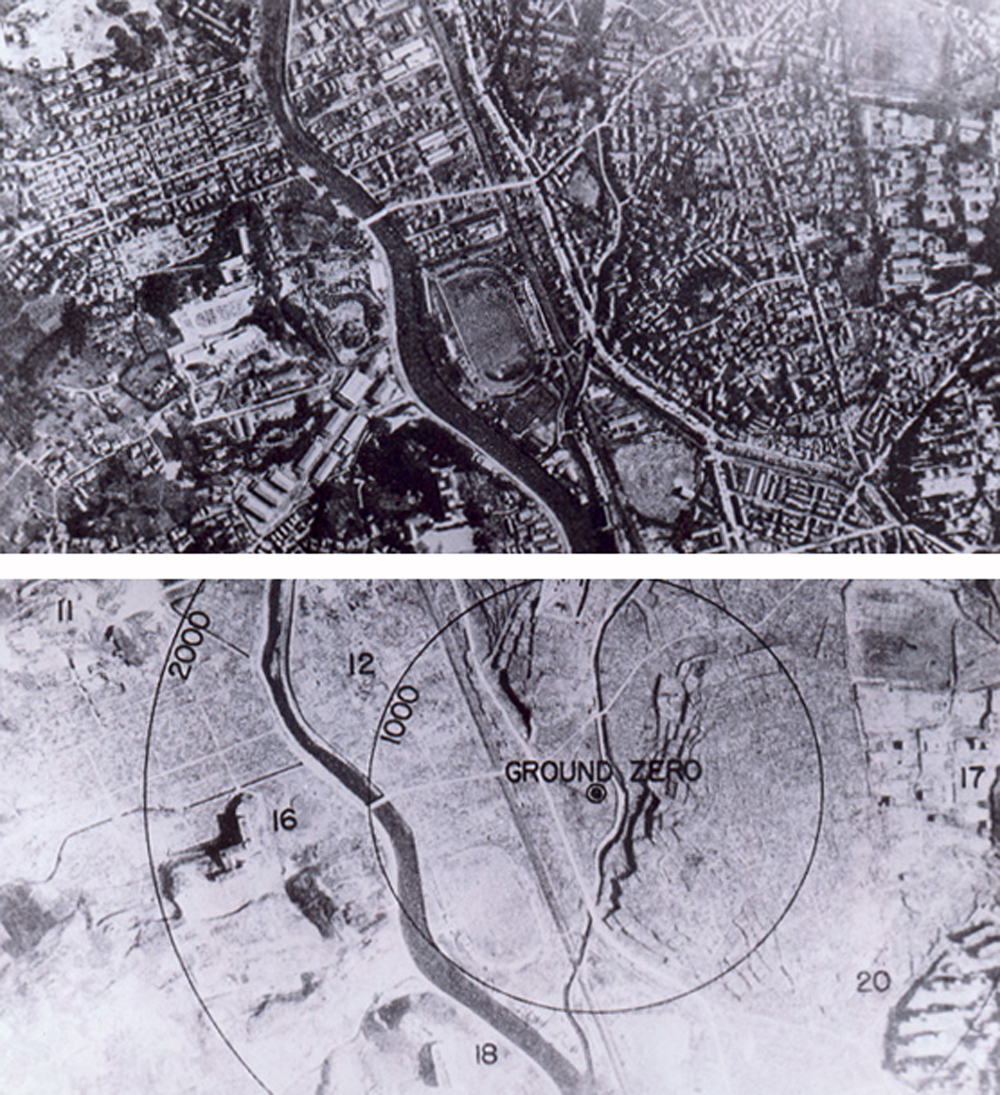

Hiroshima during World War II

At the time of its bombing, Hiroshima was a city of industrial and military significance. A number of military units were located nearby, the most important of which was the headquarters of

Field Marshal Shunroku Hata

was a field marshal ('' gensui'') in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II. He was the last surviving Japanese military officer with a marshal's rank. Hata was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to life imprisonment in 1948, but was ...

's

Second General Army, which commanded the defense of all of southern Japan, and was located in

Hiroshima Castle

, sometimes called , is a castle in Hiroshima, Japan that was the residence of the '' daimyō'' (feudal lord) of the Hiroshima Domain. The castle was originally constructed in the 1590s, but was destroyed by the atomic bombing on August 6, 1945. ...

. Hata's command consisted of some 400,000 men, most of whom were on Kyushu where an Allied invasion was correctly anticipated. Also present in Hiroshima were the headquarters of the

59th Army, the

5th Division In military terms, 5th Division may refer to:

Infantry divisions

* 5th Division (Australia)

*5th Division (People's Republic of China)

* 5th Division (Colombia)

*Finnish 5th Division (Continuation War)

* 5th Light Cavalry Division (France)

*5th Mo ...

and the

224th Division, a recently formed mobile unit. The city was defended by five batteries of 70 mm and 80 mm (2.8 and 3.1 inch)

anti-aircraft guns

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based, ...

of the 3rd Anti-Aircraft Division, including units from the 121st and 122nd Anti-Aircraft Regiments and the 22nd and 45th Separate Anti-Aircraft Battalions. In total, an estimated 40,000 Japanese military personnel were stationed in the city.

Hiroshima was a supply and logistics base for the Japanese military.

The city was a communications center, a key port for shipping, and an assembly area for troops. It supported a large war industry, manufacturing parts for planes and boats, for bombs, rifles, and handguns. The center of the city contained several

reinforced concrete buildings and lighter structures. Outside the center, the area was congested by a dense collection of small timber workshops set among Japanese houses. A few larger industrial plants lay near the outskirts of the city. The houses were constructed of timber with tile roofs, and many of the industrial buildings were also built around timber frames. The city as a whole was highly susceptible to fire damage. It was the second largest city in Japan after Kyoto that was still undamaged by air raids, primarily because it lacked the aircraft manufacturing industry that was the XXI Bomber Command's priority target. On 3 July, the Joint Chiefs of Staff placed it off limits to bombers, along with Kokura, Niigata and Kyoto.

The population of Hiroshima had reached a peak of over 381,000 earlier in the war but prior to the atomic bombing, the population had steadily decreased because of a

systematic evacuation ordered by the Japanese government. At the time of the attack, the population was approximately 340,000–350,000.

Residents wondered why Hiroshima had been spared destruction by firebombing. Some speculated that the city was to be saved for U.S. occupation headquarters, others thought perhaps their relatives in Hawaii and California had petitioned the U.S. government to avoid bombing Hiroshima. More realistic city officials had ordered buildings torn down to create long, straight

firebreak

A firebreak or double track (also called a fire line, fuel break, fireroad and firetrail in Australia) is a gap in vegetation or other combustible material that acts as a barrier to slow or stop the progress of a bushfire or wildfire. A firebre ...

s. These continued to be expanded and extended up to the morning of 6 August 1945.

Bombing of Hiroshima

Hiroshima was the primary target of the first atomic bombing mission on 6 August, with Kokura and Nagasaki as alternative targets. The 393d Bombardment Squadron B-29 ''

Enola Gay'', named after Tibbets's mother and piloted by Tibbets, took off from North Field,

Tinian

Tinian ( or ; old Japanese name: 天仁安島, ''Tenian-shima'') is one of the three principal islands of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. Together with uninhabited neighboring Aguiguan, it forms Tinian Municipality, one of the ...

, about six hours' flight time from Japan. ''Enola Gay'' was accompanied by two other B-29s: ''

The Great Artiste

''The Great Artiste'' was a U.S. Army Air Forces Silverplate B-29 bomber (B-29-40-MO 44-27353, Victor number 89), assigned to the 393d Bomb Squadron, 509th Composite Group. The aircraft was named for its bombardier, Captain Kermit Beahan ...

'', commanded by Major

Charles Sweeney

Charles William Sweeney (December 27, 1919 – July 16, 2004) was an officer in the United States Army Air Forces during World War II and the pilot who flew '' Bockscar'' carrying the Fat Man atomic bomb to the Japanese city of Nagasaki on Aug ...

, which carried instrumentation, and a then-nameless aircraft later called ''

Necessary Evil

A necessary evil is an evil that someone believes must be done or accepted because it is necessary to achieve a better outcome—especially because possible alternative courses of action or inaction are expected to be worse. It is the "lesser evi ...

'', commanded by Captain George Marquardt. ''Necessary Evil'' was the

photography aircraft.

After leaving Tinian, the aircraft made their way separately to Iwo Jima to rendezvous with Sweeney and Marquardt at 05:55 at , and set course for Japan. The aircraft arrived over the target in clear visibility at . Parsons, who was in command of the mission, armed the bomb in flight to minimize the risks during takeoff. He had witnessed four B-29s crash and burn at takeoff, and feared that a nuclear explosion would occur if a B-29 crashed with an armed Little Boy on board. His assistant,

Second Lieutenant Morris R. Jeppson, removed the safety devices 30 minutes before reaching the target area.

During the night of 5–6 August, Japanese early warning radar detected the approach of numerous American aircraft headed for the southern part of Japan. Radar detected 65 bombers headed for

Saga, 102 bound for

Maebashi

is the capital city of Gunma Prefecture, in the northern Kantō region of Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 335,352 in 151,171 households, and a population density of 1100 persons per km2. The total area of the city is . It ...

, 261 en route to

Nishinomiya

270px, Nishinomiya City Hall

270px, Aerial view of Nishinomiya city center

270px, Hirota Shrine

is a city located in Hyōgo Prefecture, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 484,368 in 218948 households and a population density of ...

, 111 headed for

Ube and 66 bound for

Imabari

270px, Imabari City Hall

270px, Aerial view of Imabari city center

is a city in Ehime Prefecture, Japan. It is the second largest city in Ehime Prefecture. , the city had an estimated population of 152,111 in 75947 households and a population ...

. An alert was given and radio broadcasting stopped in many cities, among them Hiroshima. The all-clear was sounded in Hiroshima at 00:05. About an hour before the bombing, the air raid alert was sounded again, as ''Straight Flush'' flew over the city. It broadcast a short message which was picked up by ''Enola Gay''. It read: "Cloud cover less than 3/10th at all altitudes. Advice: bomb primary." The all-clear was sounded over Hiroshima again at 07:09.

At 08:09, Tibbets started his bomb run and handed control over to his bombardier, Major

Thomas Ferebee

Thomas Wilson Ferebee (November 9, 1918 – March 16, 2000) was the bombardier aboard the B-29 Superfortress, ''Enola Gay'', which dropped the atomic bomb "Little Boy" on Hiroshima in 1945.

Biography

Thomas Wilson Ferebee was born on a far ...

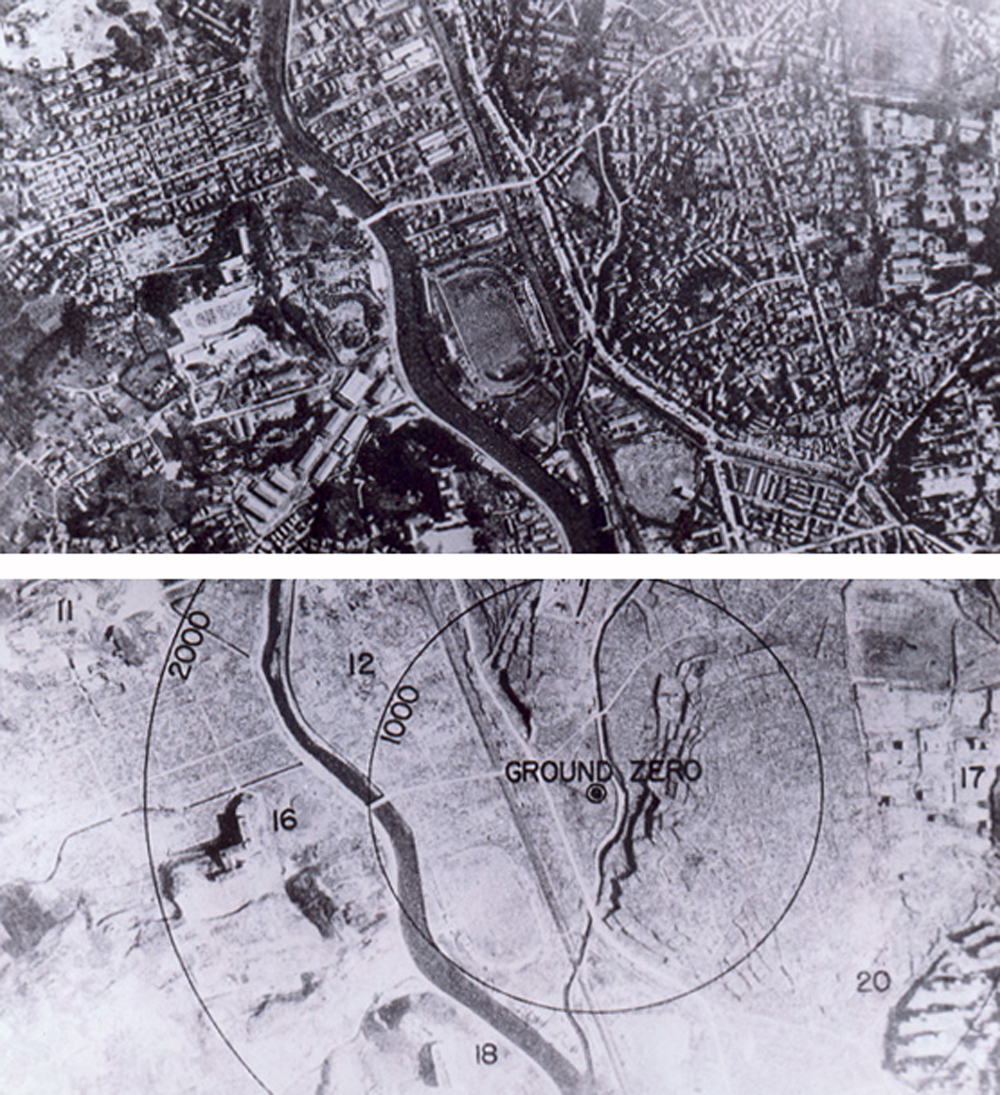

. The release at 08:15 (Hiroshima time) went as planned, and the Little Boy containing about of uranium-235 took 44.4 seconds to fall from the aircraft flying at about to a detonation height of about above the city.

[ describes how various values were recorded for the B-29's altitude at the moment of bomb release over Hiroshima. The strike report said , the official history said , Parson's log entry was , and the navigator's log was —the latter possibly an error transposing two digits. A later calculation using the indicated atmospheric pressure arrived at the figure of . Similarly, several values have been reported as the altitude of the Little Boy bomb at the moment of detonation. Published sources vary in the range of above the city. The device was set to explode at , but this was approximate. Malik uses the figure of plus or minus , determined after data review by . Radar returns from the tops of multistory buildings near the hypocenter may have triggered the detonation at a somewhat higher altitude than planned. Kerr et al. (2005) found that a detonation altitude of , plus or minus , gave the best fit for all the measurement discrepancies.] ''Enola Gay'' traveled before it felt the shock waves from the blast.

Due to

crosswind

A crosswind is any wind that has a perpendicular component to the line or direction of travel. This affects the aerodynamics of many forms of transport. Moving non-parallel to the wind's direction creates a crosswind component on the object and th ...

, the bomb missed the

aiming point {{Unreferenced, date=April 2007

In field artillery, the accuracy of indirect fire depends on the use of aiming points. In air force terminology the aiming point (or A.P.) refers to holding the intersection of the cross hairs on a bombsight when fixe ...

, the

Aioi Bridge

The is an unusual "T"-shaped three-way bridge in Hiroshima, Japan. The original bridge, constructed in 1932, was the aiming point {{Unreferenced, date=April 2007

In field artillery, the accuracy of indirect fire depends on the use of aiming po ...

, by approximately and detonated directly over

Shima Surgical Clinic. It released the equivalent energy of . The weapon was

considered very inefficient, with only 1.7 percent of its material fissioning.

The radius of total destruction was about , with resulting fires across .

''Enola Gay'' stayed over the target area for two minutes and was away when the bomb detonated. Only Tibbets, Parsons, and Ferebee knew of the nature of the weapon; the others on the bomber were only told to expect a blinding flash and given black goggles. "It was hard to believe what we saw", Tibbets told reporters, while Parsons said "the whole thing was tremendous and awe-inspiring... the men aboard with me gasped 'My God'." He and Tibbets compared the shockwave to "a close burst of

ack-ack fire".

Events on the ground