Assassinated Pakistani Islamic Scholars on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Assassination is the

The word ''assassin'' may be derived from '' asasiyyin'' (Arabic: أَسَاسِيِّين, ʾasāsiyyīn) from أَسَاس (ʾasās, "foundation, basis") + ـِيّ (-iyy), meaning "people who are faithful to the foundation

The word ''assassin'' may be derived from '' asasiyyin'' (Arabic: أَسَاسِيِّين, ʾasāsiyyīn) from أَسَاس (ʾasās, "foundation, basis") + ـِيّ (-iyy), meaning "people who are faithful to the foundation

Assassination is one of the oldest tools of

Assassination is one of the oldest tools of

During the 16th and 17th centuries, international lawyers began to voice condemnation of assassinations of leaders.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, international lawyers began to voice condemnation of assassinations of leaders.

Most major powers repudiated Cold War assassination tactics, but many allege that was merely a smokescreen for political benefit and that covert and illegal training of assassins continues today, with Russia, Israel, the U.S.,

Most major powers repudiated Cold War assassination tactics, but many allege that was merely a smokescreen for political benefit and that covert and illegal training of assassins continues today, with Russia, Israel, the U.S.,

Assassination for military purposes has long been espoused:

Assassination for military purposes has long been espoused:

A

A

Iraqi insurgents using Austrian rifles from Iran

' –

Targeted killing is the intentional killing by a government or its agents of a civilian or "

Targeted killing is the intentional killing by a government or its agents of a civilian or "

Targeted killing is a necessary option

', Sofaer, Abraham D.,

Eben Kaplan, ''

One of the earliest forms of defense against assassins was employing

One of the earliest forms of defense against assassins was employing

Assassination in the United States: An Operational Study

'' – Fein, Robert A. & Vossekuil, Brian, ''

With the advent of gunpowder, ranged assassination via bombs or firearms became possible. One of the first reactions was simply to increase the guard, creating what at times might seem a small army trailing every leader. Another was to begin clearing large areas whenever a leader was present to the point that entire sections of a city might be shut down.

As the 20th century dawned, the prevalence and capability of assassins grew quickly, as did measures to protect against them. For the first time, armored cars or limousines were put into service for safer transport, with modern versions virtually invulnerable to

With the advent of gunpowder, ranged assassination via bombs or firearms became possible. One of the first reactions was simply to increase the guard, creating what at times might seem a small army trailing every leader. Another was to begin clearing large areas whenever a leader was present to the point that entire sections of a city might be shut down.

As the 20th century dawned, the prevalence and capability of assassins grew quickly, as did measures to protect against them. For the first time, armored cars or limousines were put into service for safer transport, with modern versions virtually invulnerable to

– Appendix 7, Report of the President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy, 1964 potential visitors would be forced through numerous different checks before being granted access to the official in question, and as communication became better and information technology more prevalent, it has become all but impossible for a would-be killer to get close enough to the personage at work or in private life to effect an attempt on their life, especially with the common use of The methods used for protection by famous people have sometimes evoked negative reactions by the public, with some resenting the separation from their officials or major figures. One example might be traveling in a car protected by a bubble of clear

The methods used for protection by famous people have sometimes evoked negative reactions by the public, with some resenting the separation from their officials or major figures. One example might be traveling in a car protected by a bubble of clear

Review

''

Notorious Assassinations

– slideshow by ''

"U.S. policy on assassinations"

from CNN.com/Law Center, November 4, 2002. See also

executive order

However, Executive Order 12333, which prohibited the CIA from assassinations, was relaxed by the George W. Bush administration. * (PDF)

Is the CIA Assassination Order of a US Citizen Legal?

– video by ''Democracy Now!'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Assassinate Attacks by method Killings by type Assassinations,

murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification (jurisprudence), justification or valid excuse (legal), excuse, especially the unlawful killing of another human with malice aforethought. ("The killing of another person wit ...

of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and l ...

, head of government

The head of government is the highest or the second-highest official in the executive branch of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presides over a cabinet, a gro ...

, politician

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking, a ...

, world leader

This is a list of current heads of state and heads of government. In some cases, mainly in presidential systems, there is only one leader being both head of state and head of government. In other cases, mainly in semi-presidential and parliament ...

, member of a royal family

A royal family is the immediate family of kings/queens, emirs/emiras, sultans/ sultanas, or raja/ rani and sometimes their extended family. The term imperial family appropriately describes the family of an emperor or empress, and the term ...

or CEO. The murder of a celebrity

Celebrity is a condition of fame and broad public recognition of a person or group as a result of the attention given to them by mass media. An individual may attain a celebrity status from having great wealth, their participation in sports ...

, activist

Activism (or Advocacy) consists of efforts to promote, impede, direct or intervene in social, political, economic or environmental reform with the desire to make changes in society toward a perceived greater good. Forms of activism range fro ...

, or artist

An artist is a person engaged in an activity related to creating art, practicing the arts, or demonstrating an art. The common usage in both everyday speech and academic discourse refers to a practitioner in the visual arts only. However, th ...

, though they may not have a direct role in matters of the state, may also sometimes be considered an assassination. An assassination may be prompted by political and military motives, or done for financial gain, to avenge a grievance

A grievance () is a wrong or hardship suffered, real or supposed, which forms legitimate grounds of complaint. In the past, the word meant the infliction or cause of hardship.

See also

* Complaint system

A complaint system (also known as a co ...

, from a desire to acquire fame or notoriety

Notorious means well known for a negative trait, characteristic, or action. It may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Notorious'' (1946 film), a thriller directed by Alfred Hitchcock

* ''Notorious'' (1992 film), a TV film re ...

, or because of a military, security, insurgent or secret police

Secret police (or political police) are intelligence, security or police agencies that engage in covert operations against a government's political, religious, or social opponents and dissidents. Secret police organizations are characteristic of a ...

group's command to carry out the assassination. Acts of assassination have been performed since ancient times

Ancient history is a time period from the beginning of writing and recorded human history to as far as late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the Sumerian cuneiform script. Ancient history cov ...

. A person who carries out an assassination is called an assassin or hitman.

Etymology

The word ''assassin'' may be derived from '' asasiyyin'' (Arabic: أَسَاسِيِّين, ʾasāsiyyīn) from أَسَاس (ʾasās, "foundation, basis") + ـِيّ (-iyy), meaning "people who are faithful to the foundation

The word ''assassin'' may be derived from '' asasiyyin'' (Arabic: أَسَاسِيِّين, ʾasāsiyyīn) from أَسَاس (ʾasās, "foundation, basis") + ـِيّ (-iyy), meaning "people who are faithful to the foundation f the faith

F, or f, is the sixth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''ef'' (pronounced ), and the plural is ''efs''.

Hist ...

"

''Assassin'' is often believed to derive from the word ''hashshashin

The Order of Assassins or simply the Assassins ( fa, حَشّاشین, Ḥaššāšīn, ) were a Nizārī Ismāʿīlī order and sect of Shīʿa Islam that existed between 1090 and 1275 CE. During that time, they lived in the mountains of P ...

'' (Arabic: حشّاشين, ħashshāshīyīn), and shares its etymological roots with ''hashish

Hashish ( ar, حشيش, ()), also known as hash, "dry herb, hay" is a drug made by compressing and processing parts of the cannabis plant, typically focusing on flowering buds (female flowers) containing the most trichomes. European Monitorin ...

'' ( or ; from Arabic: ').''The Assassins: a radical sect in Islam'' – Bernard Lewis, pp. 11–12 It referred to a group of Nizari Ismailis

The Nizaris ( ar, النزاريون, al-Nizāriyyūn, fa, نزاریان, Nezāriyān) are the largest segment of the Ismaili Muslims, who are the second-largest branch of Shia Islam after the Twelvers. Nizari teachings emphasize independent ...

known as the Order of Assassins

The Order of Assassins or simply the Assassins ( fa, حَشّاشین, Ḥaššāšīn, ) were a Nizārī Ismāʿīlī order and sect of Shīʿa Islam that existed between 1090 and 1275 CE. During that time, they lived in the mountains of P ...

who worked against various political targets.

Founded by Hassan-i Sabbah

Hasan-i Sabbāh ( fa, حسن صباح) or Hassan as-Sabbāh ( ar, حسن بن الصباح الحميري, full name: Hassan bin Ali bin Muhammad bin Ja'far bin al-Husayn bin Muhammad bin al-Sabbah al-Himyari; c. 1050 – 12 June 1124) was the ...

, the Assassins were active in the fortress of Alamut

Alamut ( fa, الموت) is a region in Iran including western and eastern parts in the western edge of the Alborz (Elburz) range, between the dry and barren plain of Qazvin in the south and the densely forested slopes of the Mazandaran provinc ...

in Persia from the 8th to the 14th centuries, and later expanded into a de facto state by acquiring or building many scattered strongholds. The group killed members of the Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

, Seljuk Seljuk or Saljuq (سلجوق) may refer to:

* Seljuk Empire (1051–1153), a medieval empire in the Middle East and central Asia

* Seljuk dynasty (c. 950–1307), the ruling dynasty of the Seljuk Empire and subsequent polities

* Seljuk (warlord) (di ...

, Fatimid

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Ismaili Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east. The Fatimids, a dy ...

, and Christian Crusader elite for political and religious reasons.

Although it is commonly believed that Assassins were under the influence of hashish

Hashish ( ar, حشيش, ()), also known as hash, "dry herb, hay" is a drug made by compressing and processing parts of the cannabis plant, typically focusing on flowering buds (female flowers) containing the most trichomes. European Monitorin ...

during their killings or during their indoctrination, there is debate as to whether these claims have merit, with many Eastern writers and an increasing number of Western academics coming to believe that drug-taking was not the key feature behind the name.

The earliest known use of the verb "to assassinate" in printed English was by Matthew Sutcliffe

Matthew Sutcliffe (1550? – 1629) was an English clergyman, academic and lawyer. He became Dean of Exeter, and wrote extensively on religious matters as a controversialist. He served as chaplain to His Majesty King James I of England. He ...

in ''A Briefe Replie to a Certaine Odious and Slanderous Libel, Lately Published by a Seditious Jesuite'', a pamphlet printed in 1600, five years before it was used in ''Macbeth

''Macbeth'' (, full title ''The Tragedie of Macbeth'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It is thought to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the damaging physical and psychological effects of political ambition on those w ...

'' by William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

(1605).

Use in history

Ancient to medieval times

Assassination is one of the oldest tools of

Assassination is one of the oldest tools of power politics

Power politics is a theory in international relations which contends that distributions of power and national interests, or changes to those distributions, are fundamental causes of war and of system stability.

The concept of power politics pro ...

. It dates back at least as far as recorded history.

In the Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

, King Joash of Judah was assassinated by his own servants; Joab

Joab (Hebrew Modern: ''Yōʼav'', Tiberian: ''Yōʼāḇ'') the son of Zeruiah, was the nephew of King David and the commander of his army, according to the Hebrew Bible.

Name

The name Joab is, like many other Hebrew names, theophoric - derive ...

assassinated Absalom

Absalom ( he, ''ʾAḇšālōm'', "father of peace") was the third son of David, King of Israel with Maacah, daughter of Talmai, King of Geshur.

2 Samuel 14:25 describes him as the handsomest man in the kingdom. Absalom eventually rebelled ag ...

, King David

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

's son; and King Sennacherib

Sennacherib (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: or , meaning " Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Sargon II in 705BC to his own death in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynast ...

of Assyria was assassinated by his own sons.

Chanakya

Chanakya (Sanskrit: चाणक्य; IAST: ', ; 375–283 BCE) was an ancient Indian polymath who was active as a teacher, author, strategist, philosopher, economist, jurist, and royal advisor. He is traditionally identified as Kauṭilya o ...

(–283 BC) wrote about assassinations in detail in his political treatise ''Arthashastra

The ''Arthashastra'' ( sa, अर्थशास्त्रम्, ) is an Ancient Indian Sanskrit treatise on statecraft, political science, economic policy and military strategy. Kautilya, also identified as Vishnugupta and Chanakya, is ...

''. His student Chandragupta Maurya

Chandragupta Maurya (350-295 BCE) was a ruler in Ancient India who expanded a geographically-extensive kingdom based in Magadha and founded the Maurya dynasty. He reigned from 320 BCE to 298 BCE. The Maurya kingdom expanded to become an empi ...

, the founder of the Maurya Empire

The Maurya Empire, or the Mauryan Empire, was a geographically extensive Iron Age historical power in the Indian subcontinent based in Magadha, having been founded by Chandragupta Maurya in 322 BCE, and existing in loose-knit fashion until 1 ...

, later made use of assassinations against some of his enemies. Some famous assassination victims are Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος ; 382 – 21 October 336 BC) was the king ('' basileus'') of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia from 359 BC until his death in 336 BC. He was a member of the Argead dynasty, founders of the ...

(336 BC), the father of Alexander the Great, and Roman dictator Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

(44 BC). Emperors of Rome

The Roman emperors were the rulers of the Roman Empire from the granting of the name and title ''Augustus (title), Augustus'' to Augustus, Octavian by the Roman Senate in 27 BC onward. Augustus maintained a facade of Republican rule, rejecting mo ...

often met their end in this way, as did many of the Muslim Shia Imam

In Shia Islam, the Imamah ( ar, إمامة) is a doctrine which asserts that certain individuals from the lineage of the Islamic prophet Muhammad are to be accepted as leaders and guides of the ummah after the death of Muhammad. Imamah further ...

s hundreds of years later. Three successive Rashidun caliphs (Umar

ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb ( ar, عمر بن الخطاب, also spelled Omar, ) was the second Rashidun caliph, ruling from August 634 until his assassination in 644. He succeeded Abu Bakr () as the second caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate o ...

, Uthman Ibn Affan

Uthman ibn Affan ( ar, عثمان بن عفان, ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān; – 17 June 656), also spelled by Colloquial Arabic, Turkish and Persian rendering Osman, was a second cousin, son-in-law and notable companion of the Islamic proph ...

, and Ali ibn Abi Talib

ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib ( ar, عَلِيّ بْن أَبِي طَالِب; 600 – 661 CE) was the last of four Rightly Guided Caliphs to rule Islam (r. 656 – 661) immediately after the death of Muhammad, and he was the first Shia Imam. ...

) were assassinated in early civil conflicts between Muslims. The practice was also well known in ancient China, as in Jing Ke

Jing Ke (died 227 BC) was a ''youxia'' during the late Warring States period of Ancient China. As a retainer of Crown Prince Dan of the Yan state, he was infamous for his failed assassination attempt on King Zheng of the Qin state, who later beca ...

's failed assassination of Qin Qin may refer to:

Dynasties and states

* Qin (state) (秦), a major state during the Zhou Dynasty of ancient China

* Qin dynasty (秦), founded by the Qin state in 221 BC and ended in 206 BC

* Daqin (大秦), ancient Chinese name for the Roman Emp ...

king Ying Zheng

Qin Shi Huang (, ; 259–210 BC) was the founder of the Qin dynasty and the first emperor of a unified China. Rather than maintain the title of "king" ( ''wáng'') borne by the previous Shang and Zhou rulers, he ruled as the First Emperor ( ...

in 227 BC. Whilst many assassinations were performed by individuals or small groups, there were also specialized units who used a collective group of people to perform more than one assassination. The earliest were the sicarii

The Sicarii (Modern Hebrew: סיקריים ''siqariyim'') were a splinter group of the Jewish Zealots who, in the decades preceding Jerusalem's destruction in 70 CE, strongly opposed the Roman occupation of Judea and attempted to expel them and th ...

in 6 AD, who predated the Middle Eastern Assassins

An assassin is a person who commits targeted murder.

Assassin may also refer to:

Origin of term

* Someone belonging to the medieval Persian Ismaili order of Assassins

Animals and insects

* Assassin bugs, a genus in the family ''Reduviida ...

and Japanese shinobi

A or was a covert agent or mercenary in feudal Japan. The functions of a ninja included reconnaissance, espionage, infiltration, deception, ambush, bodyguarding and their fighting skills in martial arts, including ninjutsu.Kawakami, pp. 21� ...

s by centuries.Ross, Jeffrey Ian, ''Religion and Violence: An Encyclopedia of Faith and Conflict from Antiquity to the Present'', Routledge (January 15, 2011), Chapter: Sicarii. 978-0765620484

Modern history

During the 16th and 17th centuries, international lawyers began to voice condemnation of assassinations of leaders.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, international lawyers began to voice condemnation of assassinations of leaders. Balthazar Ayala

Balthazar Ayala (1548–1584) was a military judge in the Habsburg Netherlands during the opening decades of the Eighty Years' War who wrote an influential treatise on the law of war.

Life

Ayala was born in Antwerp in 1548, the son of a Spanish c ...

has been described as "the first prominent jurist to condemn the use of assassination in foreign policy". Alberico Gentili

Alberico Gentili (14 January 155219 June 1608) was an Italian-English jurist, a tutor of Queen Elizabeth I, and a standing advocate to the Spanish Embassy in London, who served as the Regius professor of civil law at the University of Oxford ...

condemned assassinations in a 1598 publication where he appealed to the self-interest of leaders: (i) assassinations had adverse short-term consequences by arousing the ire of the assassinated leader's successor, and (ii) assassinations had the adverse long-term consequences of causing disorder and chaos. Hugo Grotius

Hugo Grotius (; 10 April 1583 – 28 August 1645), also known as Huig de Groot () and Hugo de Groot (), was a Dutch humanist, diplomat, lawyer, theologian, jurist, poet and playwright.

A teenage intellectual prodigy, he was born in Delft ...

's works on the law of war strictly forbade assassinations, arguing that killing was only permissible on the battlefield. In the modern world, the killing of important people began to become more than a tool in power struggles between rulers themselves and was also used for political symbolism, such as in the propaganda of the deed

Propaganda of the deed (or propaganda by the deed, from the French ) is specific political direct action meant to be exemplary to others and serve as a catalyst for revolution.

It is primarily associated with acts of violence perpetrated by pro ...

.M. Gillen 1972 ''Assassination of the Prime Minister: the shocking death of Spencer Perceval''. London: Sidgwick & Jackson .

In Japan, a group of assassins called the Four Hitokiri of the Bakumatsu

4 (four) is a number, numeral and digit. It is the natural number following 3 and preceding 5. It is the smallest semiprime and composite number, and is considered unlucky in many East Asian cultures.

In mathematics

Four is the smallest c ...

killed a number of people, including Ii Naosuke

was ''daimyō'' of Hikone (1850–1860) and also Tairō of the Tokugawa shogunate, Japan, a position he held from April 23, 1858, until his death, assassinated in the Sakuradamon Incident on March 24, 1860. He is most famous for signing the Ha ...

who was the head of administration for the Tokugawa shogunate, during the Boshin War

The , sometimes known as the Japanese Revolution or Japanese Civil War, was a civil war in Japan fought from 1868 to 1869 between forces of the ruling Tokugawa shogunate and a clique seeking to seize political power in the name of the Imperi ...

. Most of the assassinations in Japan were committed with bladed weaponry, a trait that was carried on into modern history. A video-record exists of the assassination of Inejiro Asanuma, using a sword.

In the United States, within 100 years, four presidents—Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

, James A. Garfield

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) was the 20th president of the United States, serving from March 4, 1881 until his death six months latertwo months after he was shot by an assassin. A lawyer and Civil War gene ...

, William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

and John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

—died at the hands of assassins. There have been at least 20 known attempts on U.S. presidents' lives.

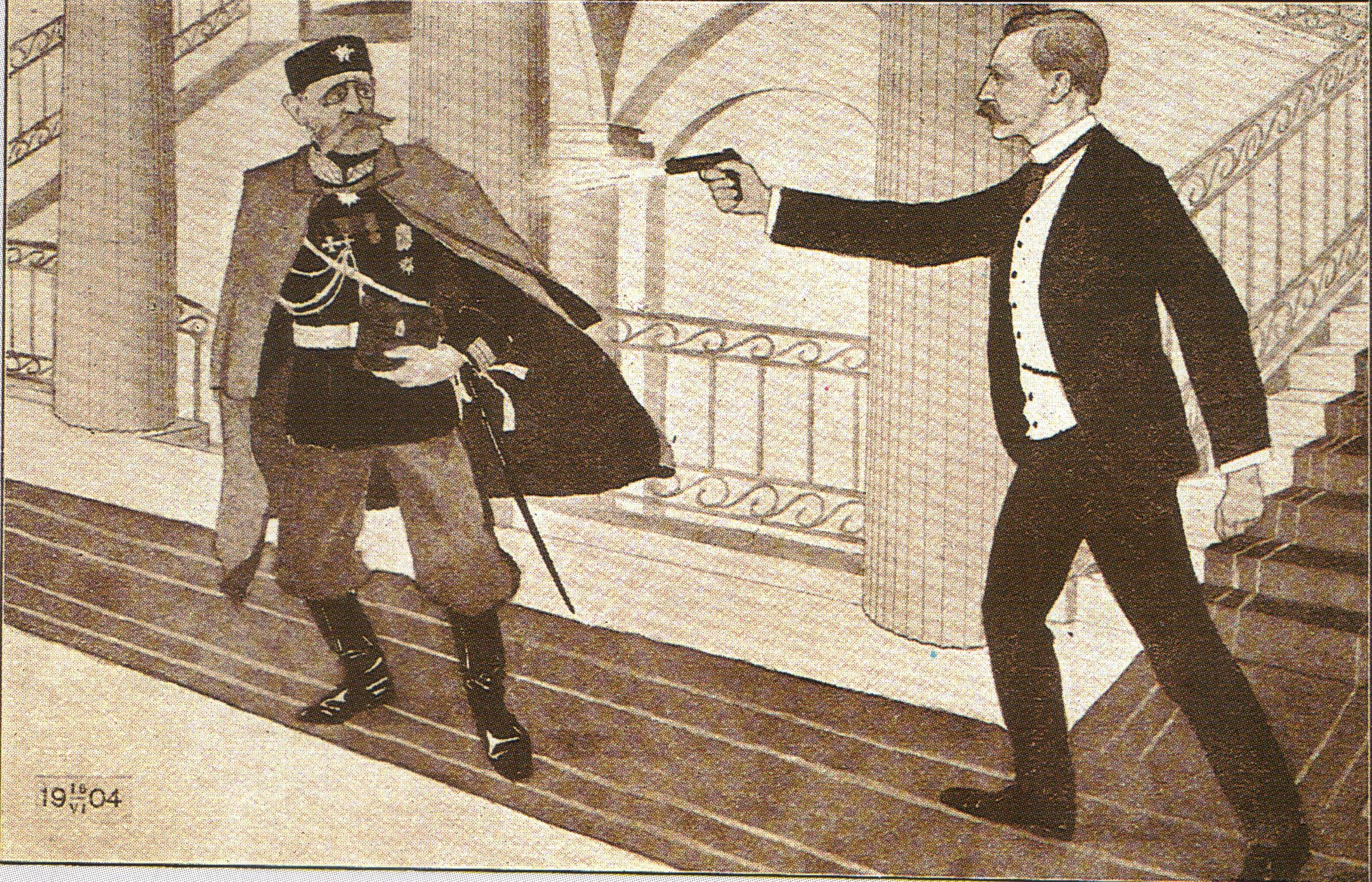

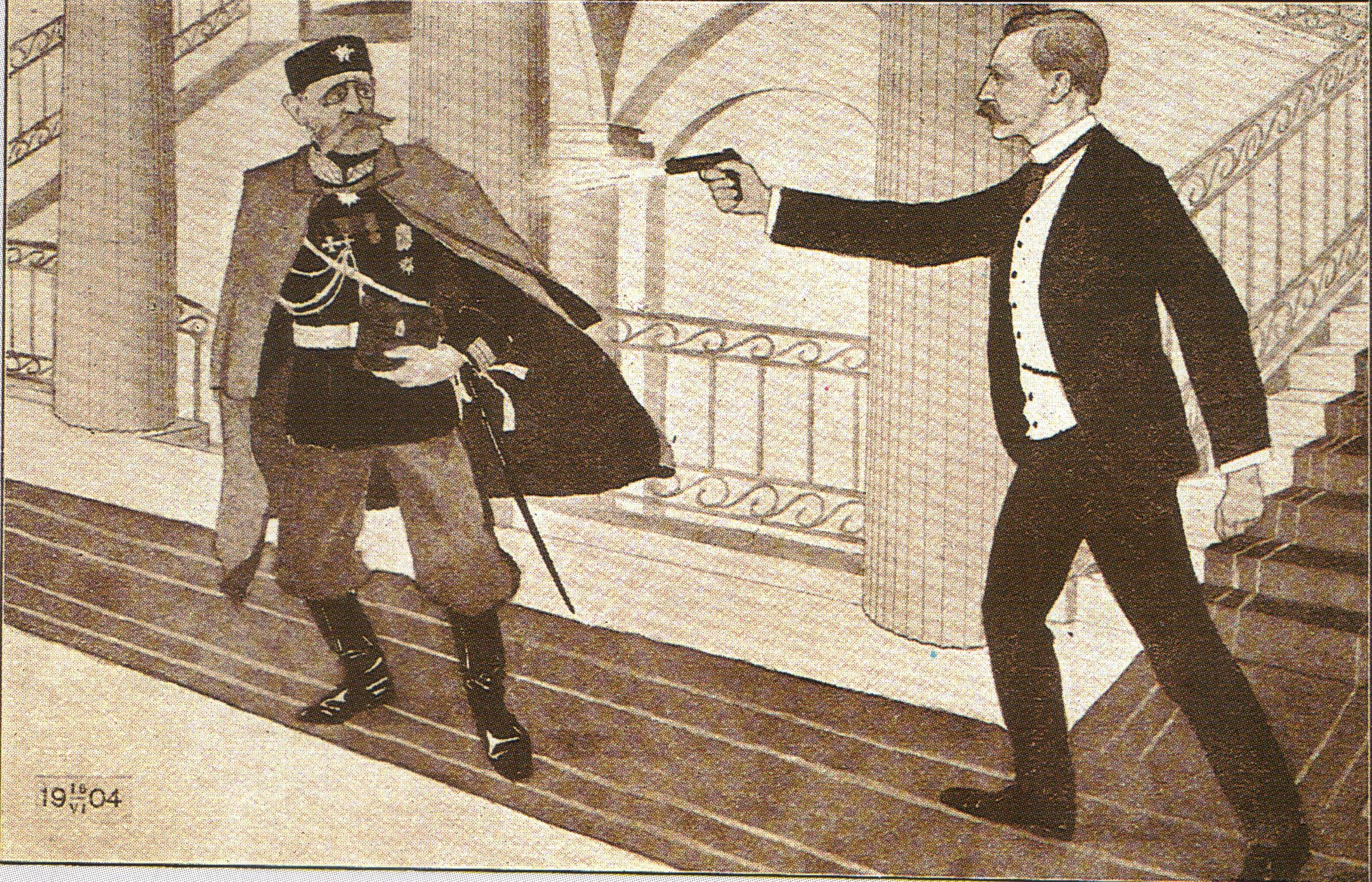

In Austria, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, were assassinated on 28 June 1914 by Bosnian Serb student Gavrilo Princip. They were shot at close range whil ...

and his wife Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg

Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg (; cs, Žofie Marie Josefína Albína hraběnka Chotková z Chotkova a Vojnína 1 March 1868 – 28 June 1914) was the wife of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne. Their assas ...

in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, carried out by Gavrilo Princip

Gavrilo Princip ( sr-Cyrl, Гаврило Принцип, ; 25 July 189428 April 1918) was a Bosnian Serb student who assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914.

Prin ...

, a Serbian nationalist, is blamed for igniting World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich ( ; ; 7 March 1904 – 4 June 1942) was a high-ranking German SS and police official during the Nazi era and a principal architect of the Holocaust.

He was chief of the Reich Security Main Office (inclu ...

died after an attack by British-trained Czechoslovak soldiers on behalf of the Czechoslovak government in exile in Operation Anthropoid

On 27 May 1942 in Prague, Reinhard Heydrichthe commander of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), acting governor of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, and a principal architect of the Holocaustwas attacked and wounded in an assassinatio ...

, and knowledge from decoded transmissions allowed the United States to carry out a targeted attack, killing Japanese Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

Isoroku Yamamoto

was a Marshal Admiral of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) and the commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet during World War II until he was killed.

Yamamoto held several important posts in the IJN, and undertook many of its changes and reor ...

while he was travelling by plane.

During the 1930s and 1940s, Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

's NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

carried out numerous assassinations outside of the Soviet Union, such as the killings of Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists

The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists ( uk, Організація українських націоналістів, Orhanizatsiya ukrayins'kykh natsionalistiv, abbreviated OUN) was a Ukrainian ultranationalist political organization estab ...

leader Yevhen Konovalets

Yevhen Mykhailovych Konovalets ( uk, Євген Михайлович Коновалець; June 14, 1891 – May 23, 1938), also anglicized as Eugene Konovalets, was a military commander of the Ukrainian National Republic army, veteran of the Uk ...

, Ignace Poretsky

Ignace Reiss (1899 – 4 September 1937) – also known as "Ignace Poretsky,"

"Ignatz Reiss,"

"Ludwig,"

"Ludwik", "Hans Eberhardt,"

"Steff Brandt,"

Nathan Poreckij,

and "Walter Scott (an officer of the U.S. military intelligence)" ...

, Fourth International

The Fourth International (FI) is a revolutionary socialist international organization consisting of followers of Leon Trotsky, also known as Trotskyists, whose declared goal is the overthrowing of global capitalism and the establishment of wor ...

secretary Rudolf Klement, Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

, and the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM

The Workers' Party of Marxist Unification ( es, Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista, POUM; ca, Partit Obrer d'Unificació Marxista) was a Spanish communist party formed during the Second Spanish Republic, Second Republic and mainly active a ...

) leadership in Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the north ...

. India's "Father of the Nation", Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

, was shot to death

This is a historical list of countries by firearm-related death rate per 100,000 population in the listed year.

Homicide figures may include justifiable homicides along with criminal homicides, depending upon jurisdiction and reporting standard ...

on January 30, 1948, by Nathuram Godse

Nathuram Vinayak Godse (19 May 1910 – 15 November 1949) was the assassin of Mahatma Gandhi. He was a Hindu nationalist from Maharashtra who shot Gandhi in the chest three times at point blank range at a multi-faith prayer meeting in Birla ...

.

The African-American civil rights activist, Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

, was assassinated

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have a ...

on April 4, 1968, at the Lorraine Motel (now the National Civil Rights Museum

The National Civil Rights Museum is a complex of museums and historic buildings in Memphis, Tennessee; its exhibits trace the history of the civil rights movement in the United States from the 17th century to the present. The museum is built aro ...

) in Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the seat of Shelby County in the southwest part of the state; it is situated along the Mississippi River. With a population of 633,104 at the 2020 U.S. census, Memphis is the second-mos ...

. Three years prior, another African-American civil rights activist, Malcolm X

Malcolm X (born Malcolm Little, later Malik el-Shabazz; May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965) was an American Muslim minister and human rights activist who was a prominent figure during the civil rights movement. A spokesman for the Nation of Is ...

, was assassinated at the Audubon Ballroom

The Audubon Theatre and Ballroom, generally referred to as the Audubon Ballroom, was a theatre and ballroom located at 3940 Broadway at West 165th Street in the Washington Heights neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City. It was built in 1912 a ...

on February 21, 1965.

Cold War and beyond

Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

, Paraguay, Chile, and other nations accused of engaging in such operations. After the Iranian Revolution

The Iranian Revolution ( fa, انقلاب ایران, Enqelâb-e Irân, ), also known as the Islamic Revolution ( fa, انقلاب اسلامی, Enqelâb-e Eslâmī), was a series of events that culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynas ...

of 1979, the new Islamic government of Iran began an international campaign of assassination that lasted into the 1990s. At least 162 killings in 19 countries have been linked to the senior leadership of the Islamic Republic of Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

. The campaign came to an end after the Mykonos restaurant assassinations

In the Mykonos restaurant assassinations ( fa, ترور رستوران میکونوس; also the "Mykonos Incident"), Iranian-Kurdish opposition leaders Sadegh Sharafkandi, Fattah Abdoli, Homayoun Ardalan and their translator Nouri Dehkordi, wer ...

because a German court publicly implicated senior members of the government and issued arrest warrants for Ali Fallahian

Ali Fallahian ( fa, علی فلاحیان , born 23 October 1949) is an Iranian politician and cleric. He served as intelligence minister from 1989 to 1997 under the presidency of Ali Akbar Rafsanjani.

Early life and education

Fallahian was b ...

, the head of Iranian intelligence. Evidence indicates that Fallahian's personal involvement and individual responsibility for the murders were far more pervasive than his current indictment record represents.

In India, Prime Ministers

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (; Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and a central figure of the Indian National Congress. She was elected as third prime minister of India in 1966 ...

and her son Rajiv Gandhi

Rajiv Gandhi (; 20 August 1944 – 21 May 1991) was an Indian politician who served as the sixth prime minister of India from 1984 to 1989. He took office after the 1984 assassination of his mother, then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, to beco ...

(neither of whom was related to Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

, who had himself been assassinated in 1948), were assassinated in 1984 and 1991 respectively in what were linked to separatist

Separatism is the advocacy of cultural, ethnic, tribal, religious, racial, governmental or gender separation from the larger group. As with secession, separatism conventionally refers to full political separation. Groups simply seeking greate ...

movements in Punjab

Punjab (; Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising ...

and northern Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, respectively.

In 1994, the assassination of Juvénal Habyarimana and Cyprien Ntaryamira

On the evening of 6 April 1994, the aircraft carrying Rwandan president Juvénal Habyarimana and Burundian president Cyprien Ntaryamira, both Hutu, was shot down with surface-to-air missiles as their jet prepared to land in Kigali, Rwanda. The ...

during the Rwandan Civil War

The Rwandan Civil War was a large-scale civil war in Rwanda which was fought between the Rwandan Armed Forces, representing the country's government, and the rebel Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) from 1October 1990 to 18 July 1994. The war arose ...

sparked the Rwandan genocide

The Rwandan genocide occurred between 7 April and 15 July 1994 during the Rwandan Civil War. During this period of around 100 days, members of the Tutsi minority ethnic group, as well as some moderate Hutu and Twa, were killed by armed Hutu ...

.

In Israel, Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin

Yitzhak Rabin (; he, יִצְחָק רַבִּין, ; 1 March 1922 – 4 November 1995) was an Israeli politician, statesman and general. He was the fifth Prime Minister of Israel, serving two terms in office, 1974–77, and from 1992 until h ...

was assassinated on November 4, 1995, by Yigal Amir

Yigal Amir ( he, יגאל עמיר; born May 31, 1970) is an Israeli right-wing extremist who assassinated former Prime Minister of Israel, Yitzhak Rabin. At the time of the assassination he was a law student at Bar-Ilan University. The assas ...

, who opposed the Oslo Accords

The Oslo Accords are a pair of agreements between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO): the Oslo I Accord, signed in Washington, D.C., in 1993;

. In Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

, the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri

Rafik is the given name of:

*Rafik Al-Hariri (1944–2005), business tycoon, former Prime Minister of Lebanon

*Rafik Bouderbal (born 1987), French-born Algerian player currently playing for ES Sétif in the Algerian Championnat National

*Rafik Deg ...

on February 14, 2005, prompted an investigation by the United Nations. The suggestion in the resulting ''Mehlis report

The Mehlis Report ...

'' that there was involvement by Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

prompted the Cedar Revolution

The Cedar Revolution ( ar, ثورة الأرز, ''thawrat al-arz'') or Independence Uprising ( ar, انتفاضة الاستقلال, ''intifāḍat al-istiqlāl'') was a chain of demonstrations in Lebanon (especially in the capital Beirut) trig ...

, which drove Syrian troops out of Lebanon.

In Japan, former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe

Shinzo Abe ( ; ja, 安倍 晋三, Hepburn romanization, Hepburn: , ; 21 September 1954 – 8 July 2022) was a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan and President of the Liberal Democratic Party (Japan), President of the Lib ...

was assassinated

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have a ...

on July 8, 2022, while delivering a campaign speech in Nara City

is the capital city of Nara Prefecture, Japan. As of 2022, Nara has an estimated population of 367,353 according to World Population Review, making it the largest city in Nara Prefecture and sixth-largest in the Kansai region of Honshu. Nara is ...

. Japanese state media reported about five hours later that he died in the hospital.

He was the victim of the murderer's personal grudge.

Further motivations

As a military and foreign policy doctrine

Assassination for military purposes has long been espoused:

Assassination for military purposes has long been espoused: Sun Tzu

Sun Tzu ( ; zh, t=孫子, s=孙子, first= t, p=Sūnzǐ) was a Chinese military general, strategist, philosopher, and writer who lived during the Eastern Zhou period of 771 to 256 BCE. Sun Tzu is traditionally credited as the author of ''The ...

, writing around 500 BC, argued in favor of using assassination in his book ''The Art of War

''The Art of War'' () is an ancient Chinese military treatise dating from the Late Spring and Autumn Period (roughly 5th century BC). The work, which is attributed to the ancient Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu ("Master Sun"), is com ...

''. Nearly 2000 years later, in his book ''The Prince

''The Prince'' ( it, Il Principe ; la, De Principatibus) is a 16th-century political treatise written by Italian diplomat and political theorist Niccolò Machiavelli as an instruction guide for new princes and royals. The general theme of ''The ...

'', Machiavelli also advises rulers to assassinate enemies whenever possible to prevent them from posing a threat. An army and even a nation might be based upon and around a particularly strong, canny, or charismatic leader, whose loss could paralyze the ability of both to make war.

For similar and additional reasons, assassination has also sometimes been used in the conduct of foreign policy

A State (polity), state's foreign policy or external policy (as opposed to internal or domestic policy) is its objectives and activities in relation to its interactions with other states, unions, and other political entities, whether bilaterall ...

. The costs and benefits of such actions are difficult to compute. It may not be clear whether the assassinated leader gets replaced with a more or less competent successor, whether the assassination provokes ire in the state in question, whether the assassination leads to souring domestic public opinion, and whether the assassination provokes condemnation from third-parties. One study found that perceptual biases held by leaders often negatively affect decision making in that area, and decisions to go forward with assassinations often reflect the vague hope that any successor might be better.

In both military and foreign policy assassinations, there is the risk that the target could be replaced by an even more competent leader or that such a killing (or a failed attempt) will "martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

" a leader and lead to greater support of their cause by showing the ruthlessness of the assassins. Faced with particularly brilliant leaders, that possibility has in various instances been risked, such as in the attempts to kill the Athenian Alcibiades

Alcibiades ( ; grc-gre, Ἀλκιβιάδης; 450 – 404 BC) was a prominent Athenian statesman, orator, and general. He was the last of the Alcmaeonidae, which fell from prominence after the Peloponnesian War. He played a major role in t ...

during the Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) was an ancient Greek war fought between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Greek world. The war remained undecided for a long time until the decisive intervention of th ...

. A number of additional examples from World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

show how assassination was used as a tool:

* The assassination of Reinhard Heydrich

On 27 May 1942 in Prague, Reinhard Heydrichthe commander of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), acting governor of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, and a principal architect of the Holocaustwas attacked and wounded in an assassinatio ...

in Prague on May 27, 1942, by the British and Czechoslovak government-in-exile. That case illustrates the difficulty of comparing the benefits of a foreign policy goal (strengthening the legitimacy and influence of the Czechoslovak government-in-exile

The Czechoslovak government-in-exile, sometimes styled officially as the Provisional Government of Czechoslovakia ( cz, Prozatímní vláda Československa, sk, Dočasná vláda Československa), was an informal title conferred upon the Czechos ...

in London) against the possible costs resulting from an assassination (the Lidice massacre

The Lidice massacre was the complete destruction of the village of Lidice in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, now the Czech Republic, in June 1942 on orders from Adolf Hitler and the successor of the ''Reichsführer-SS'' Heinrich Himmler ...

).

* The American interception of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto

was a Marshal Admiral of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) and the commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet during World War II until he was killed.

Yamamoto held several important posts in the IJN, and undertook many of its changes and reor ...

's plane during World War II after his travel route had been decrypted.

* Operation Gaff During World War II, Operation Gaff was the parachuting of a six-man patrol of Special Air Service commandos into German-occupied France on Tuesday 25 July 1944, with the aim of killing or kidnapping German field marshal Erwin Rommel.

From March 1 ...

was a planned British commando raid to capture or kill the German field marshal Erwin Rommel

Johannes Erwin Eugen Rommel () (15 November 1891 – 14 October 1944) was a German field marshal during World War II. Popularly known as the Desert Fox (, ), he served in the ''Wehrmacht'' (armed forces) of Nazi Germany, as well as servi ...

, also known as "The Desert Fox".''Commando Extraordinary'' – Foley, Charles; Legion for the Survival of Freedom, 1992, page 155

Use of assassination has continued in more recent conflicts:

* During the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

, the US engaged in the Phoenix Program

The Phoenix Program ( vi, Chiến dịch Phụng Hoàng) was designed and initially coordinated by the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) during the Vietnam War, involving the American, Australian, and South Vietnamese militaries. ...

to assassinate Viet Cong

,

, war = the Vietnam War

, image = FNL Flag.svg

, caption = The flag of the Viet Cong, adopted in 1960, is a variation on the flag of North Vietnam. Sometimes the lower stripe was green.

, active ...

leaders and sympathizers. It killed between 6,000 and 41,000 people, with official "targets" of 1,800 per month.

* With the January 3, 2020 Baghdad International Airport airstrike, the US assassinated

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have a ...

the commander of Iran's Quds Force

The Quds Force ( fa, نیروی قدس, niru-ye qods, Jerusalem Force) is one of five branches of Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) specializing in unconventional warfare and military intelligence operations. U.S. Army's Iraq War ...

General Qasem Soleimani

Qasem Soleimani ( fa, قاسم سلیمانی, ; 11 March 19573January 2020) was an Iranian military officer who served in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). From 1998 until his assassination in 2020, he was the commander of the Quds F ...

and the commander of Iraq's Popular Mobilization Forces

The Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) ( ar, الحشد الشعبي ''al-Ḥashd ash-Shaʿbī''), also known as the People's Mobilization Committee (PMC) and the Popular Mobilization Units (PMU), is an Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, transli ...

Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis

Jamal Ja'far Muhammad Ali Al Ibrahim ( ar, جمال جعفر محمد علي آل إبراهيم ', 16 Nov 1954 – 2 January 2020), known by the kunya Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis ( ar, أبو مهدي المهندس, lit=Father of Mahdi, the Engine ...

, along with eight other high-ranking military personnel. The assassination of the military leaders was part of escalating tensions between the US and Iran and the American-led intervention in Iraq.

As a tool of insurgents

Insurgent groups have often employed assassination as a tool to further their causes. Assassinations provide several functions for such groups: the removal of specific enemies and as propaganda tools to focus the attention of media and politics on their cause. TheIrish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief tha ...

guerrillas in 1919 to 1921 killed many Royal Irish Constabulary

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC, ga, Constáblacht Ríoga na hÉireann; simply called the Irish Constabulary 1836–67) was the police force in Ireland from 1822 until 1922, when all of the country was part of the United Kingdom. A separate ...

Police intelligence officers during the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

. Michael Collins Michael Collins or Mike Collins most commonly refers to:

* Michael Collins (Irish leader) (1890–1922), Irish revolutionary leader, soldier, and politician

* Michael Collins (astronaut) (1930–2021), American astronaut, member of Apollo 11 and Ge ...

set up a special unit, the Squad, for that purpose, which had the effect of intimidating many policemen into resigning from the force. The Squad's activities peaked with the killing of 14 British agents in Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

on Bloody Sunday

Bloody Sunday may refer to:

Historical events Canada

* Bloody Sunday (1923), a day of police violence during a steelworkers' strike for union recognition in Sydney, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia

* Bloody Sunday (1938), police violence aga ...

in 1920.

The tactic was used again by the Provisional IRA

The Irish Republican Army (IRA; ), also known as the Provisional Irish Republican Army, and informally as the Provos, was an Irish republicanism, Irish republican paramilitary organisation that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland, fa ...

during the Troubles

The Troubles ( ga, Na Trioblóidí) were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it is sometimes described as an "i ...

in Northern Ireland (1969–1998). Killing Royal Ulster Constabulary

The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) was the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2001. It was founded on 1 June 1922 as a successor to the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC)Richard Doherty, ''The Thin Green Line – The History of the Royal ...

officers and assassination of unionist politicians was one of a number of methods used in the Provisional IRA campaign 1969–1997

From 1969 until 1997,Moloney, p. 472 the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) conducted an armed paramilitary campaign primarily in Northern Ireland and England, aimed at ending British rule in Northern Ireland in order to create a united Ir ...

. The IRA also attempted to assassinate British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. S ...

by bombing the Conservative Party Conference in a Brighton

Brighton () is a seaside resort and one of the two main areas of the City of Brighton and Hove in the county of East Sussex, England. It is located south of London.

Archaeological evidence of settlement in the area dates back to the Bronze A ...

hotel. Loyalist paramilitaries

Ulster loyalism is a strand of Ulster unionism associated with working class Ulster Protestants in Northern Ireland. Like other unionists, loyalists support the continued existence of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom, and oppose a uni ...

retaliated by killing Catholics at random and assassinating Irish nationalist

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cu ...

politicians.

Basque

Basque may refer to:

* Basques, an ethnic group of Spain and France

* Basque language, their language

Places

* Basque Country (greater region), the homeland of the Basque people with parts in both Spain and France

* Basque Country (autonomous co ...

separatists ETA

Eta (uppercase , lowercase ; grc, ἦτα ''ē̂ta'' or ell, ήτα ''ita'' ) is the seventh letter of the Greek alphabet, representing the close front unrounded vowel . Originally denoting the voiceless glottal fricative in most dialects, ...

in Spain assassinated many security and political figures since the late 1960s, notably the president of the government of Spain, Luis Carrero Blanco

Admiral-General Luis Carrero Blanco (4 March 1904 – 20 December 1973) was a Spanish Navy officer and politician. A long-time confidant and right-hand man of dictator Francisco Franco, Carrero served as the Prime Minister of Spain and i ...

, 1st Duke of Carrero-Blanco Grandee of Spain, in 1973. In the early 1990s, it also began to target academics, journalists and local politicians who publicly disagreed with it.

The Red Brigades

The Red Brigades ( it, Brigate Rosse , often abbreviated BR) was a far-left Marxist–Leninist armed organization operating as a terrorist and guerrilla group based in Italy responsible for numerous violent incidents, including the abduction ...

in Italy carried out assassinations of political figures and, to a lesser extent, so did the Red Army Faction

The Red Army Faction (RAF, ; , ),See the section "Name" also known as the Baader–Meinhof Group or Baader–Meinhof Gang (, , active 1970–1998), was a West German far-left Marxist-Leninist urban guerrilla group founded in 1970.

The ...

in Germany in the 1970s and the 1980s.

In the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

, communist insurgents routinely assassinated government officials and individual civilians deemed to offend or rival the revolutionary movement. Such attacks, along with widespread military activity by insurgent bands, almost brought the Ngo Dinh Diem

Ngô Đình Diệm ( or ; ; 3 January 1901 – 2 November 1963) was a South Vietnamese politician. He was the final prime minister of the State of Vietnam (1954–1955), and then served as the first president of South Vietnam (Republic of ...

regime to collapse before the US intervened.

Psychology

A major study about assassination attempts in the US in the second half of the 20th century came to the conclusion that most prospective assassins spend copious amounts of time planning and preparing for their attempts. Assassinations are thus rarely "impulsive" actions. However, about 25% of the actual attackers were found to bedelusion

A delusion is a false fixed belief that is not amenable to change in light of conflicting evidence. As a pathology, it is distinct from a belief based on false or incomplete information, confabulation, dogma, illusion, hallucination, or some o ...

al, a figure that rose to 60% with "near-lethal approachers" (people apprehended before reaching their targets). That shows that while mental instability plays a role in many modern assassinations, the more delusional attackers are less likely to succeed in their attempts. The report also found that around two-thirds of attackers had previously been arrested, not necessarily for related offenses; 44% had a history of serious depression, and 39% had a history of substance abuse.

Techniques

Modern methods

With the advent of effectiveranged weaponry

A ranged weapon is any weapon that can engage targets beyond hand-to-hand distance, i.e. at distances greater than the physical reach of the user holding the weapon itself. The act of using such a weapon is also known as shooting. It is someti ...

and later firearms

A firearm is any type of gun designed to be readily carried and used by an individual. The term is legally defined further in different countries (see Legal definitions).

The first firearms originated in 10th-century China, when bamboo tubes c ...

, the position of an assassination target was more precarious. Bodyguards were no longer enough to deter determined killers, who no longer needed to engage directly or even to subvert the guard to kill the leader in question. Moreover, the engagement of targets at greater distances dramatically increased the chances for assassins to survive since they could quickly flee the scene. The first heads of government to be assassinated with a firearm were James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray

James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray (c. 1531 – 23 January 1570) was a member of the House of Stewart as the illegitimate son of King James V of Scotland, James V of Scotland. A supporter of his half-sister Mary, Queen of Scots, he was the regent ...

, the regent of Scotland, in 1570, and William the Silent

William the Silent (24 April 153310 July 1584), also known as William the Taciturn (translated from nl, Willem de Zwijger), or, more commonly in the Netherlands, William of Orange ( nl, Willem van Oranje), was the main leader of the Dutch Re ...

, the Prince of Orange of the Netherlands, in 1584. Gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). ...

and other explosives also allowed the use of bombs or even greater concentrations of explosives for deeds requiring a larger touch.

Explosives, especially the car bomb

A car bomb, bus bomb, lorry bomb, or truck bomb, also known as a vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (VBIED), is an improvised explosive device designed to be detonated in an automobile or other vehicles.

Car bombs can be roughly divided ...

, become far more common in modern history, with grenades

A grenade is an explosive weapon typically thrown by hand (also called hand grenade), but can also refer to a shell (explosive projectile) shot from the muzzle of a rifle (as a rifle grenade) or a grenade launcher. A modern hand grenade gene ...

and remote-triggered land mines also used, especially in the Middle East and the Balkans; the initial attempt on Archduke Franz Ferdinand

Archduke Franz Ferdinand Carl Ludwig Joseph Maria of Austria, (18 December 1863 – 28 June 1914) was the heir presumptive to the throne of Austria-Hungary. His assassination in Sarajevo was the most immediate cause of World War I.

F ...

's life was with a grenade. With heavy weapons, the rocket-propelled grenade

A rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) is a shoulder-fired missile weapon that launches rockets equipped with an explosive warhead. Most RPGs can be carried by an individual soldier, and are frequently used as anti-tank weapons. These warheads are a ...

(RPG) has become a useful tool given the popularity of armored cars (discussed below), and Israeli forces have pioneered the use of aircraft-mounted missiles, as well as the innovative use of explosive devices.

A

A sniper

A sniper is a military/paramilitary marksman who engages targets from positions of concealment or at distances exceeding the target's detection capabilities. Snipers generally have specialized training and are equipped with high-precision r ...

with a precision rifle is often used in fictional assassinations. However, certain pragmatic difficulties attend long-range shooting, including finding a hidden shooting position with a clear line of sight, detailed advance knowledge of the intended victim's travel plans, the ability to identify the target at long range, and the ability to score a first-round lethal hit at long range, which is usually measured in hundreds of meters. A dedicated sniper rifle

A sniper rifle is a high-precision, long-range rifle. Requirements include accuracy, reliability, mobility, concealment and optics for anti-personnel, anti-materiel and surveillance uses of the military sniper. The modern sniper rifle is a por ...

is also expensive, often costing thousands of dollars because of the high level of precision machining and handfinishing required to achieve extreme accuracy.Iraqi insurgents using Austrian rifles from Iran

' –

The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was fo ...

, Tuesday February 13, 2007

Despite their comparative disadvantages, handguns are more easily concealable and so are much more commonly used than rifles. Of the 74 principal incidents evaluated in a major study about assassination attempts in the US in the second half of the 20th century, 51% were undertaken by a handgun, 30% with a rifle or shotgun, 15% used knives, and 8% explosives (the use of multiple weapons/methods was reported in 16% of all cases).

In the case of state-sponsored assassination, poisoning can be more easily denied. Georgi Markov

Georgi Ivanov Markov ( bg, Георги Иванов Марков ; 1 March 1929 – 11 September 1978) was a Bulgarian dissident writer. He originally worked as a novelist, screenwriter and playwright in his native country, the People's Repub ...

, a dissident from Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

, was assassinated by ricin

Ricin ( ) is a lectin (a carbohydrate-binding protein) and a highly potent toxin produced in the seeds of the castor oil plant, ''Ricinus communis''. The median lethal dose (LD50) of ricin for mice is around 22 micrograms per kilogram of body ...

poisoning. A tiny pellet containing the poison was injected into his leg through a specially designed umbrella

An umbrella or parasol is a folding canopy supported by wooden or metal ribs that is usually mounted on a wooden, metal, or plastic pole. It is designed to protect a person against rain or sunlight. The term ''umbrella'' is traditionally used ...

. Widespread allegations involving the Bulgarian government and the KGB

The KGB (russian: links=no, lit=Committee for State Security, Комитет государственной безопасности (КГБ), a=ru-KGB.ogg, p=kəmʲɪˈtʲet ɡəsʊˈdarstvʲɪn(ː)əj bʲɪzɐˈpasnəsʲtʲɪ, Komitet gosud ...

have not led to any legal results. However, after the fall of the Soviet Union, it was learned that the KGB had developed an umbrella that could inject ricin pellets into a victim, and two former KGB agents who defected stated that the agency assisted in the murder. The CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

made several attempts to assassinate Fidel Castro, many of the schemes involving poisoning his cigars. In the late 1950s, the KGB assassin Bohdan Stashynsky

Bohdan Mykolayovych Stashynsky ( uk, Богда́н Микола́йович Сташи́нський, born 4 November 1931) is a former Soviet spy who assassinated the Ukrainian nationalist leaders Lev Rebet and Stepan Bandera in the late 1950s ...

killed Ukrainian nationalist leaders Lev Rebet

Lev Rebet (March 3, 1912 – October 12, 1957) was a Ukrainian political writer and anti-communist during World War II. He was a key cabinet member in the Ukrainian government (backed by Stepan Bandera's faction of OUN) which proclaimed independ ...

and Stepan Bandera

Stepan Andriyovych Bandera ( uk, Степа́н Андрі́йович Банде́ра, Stepán Andríyovych Bandéra, ; pl, Stepan Andrijowycz Bandera; 1 January 1909 – 15 October 1959) was a Ukrainian far-right leader of the radical, terr ...

with a spray gun that fired a jet of poison gas from a crushed cyanide

Cyanide is a naturally occurring, rapidly acting, toxic chemical that can exist in many different forms.

In chemistry, a cyanide () is a chemical compound that contains a functional group. This group, known as the cyano group, consists of ...

ampule, making their deaths look like heart attacks. A 2006 case in the UK concerned the assassination of Alexander Litvinenko who was given a lethal dose of radioactive polonium

Polonium is a chemical element with the symbol Po and atomic number 84. Polonium is a chalcogen. A rare and highly radioactive metal with no stable isotopes, polonium is chemically similar to selenium and tellurium, though its metallic character ...

-210, possibly passed to him in aerosol form sprayed directly onto his food. Litvinenko, a former KGB agent, had been granted asylum in the UK in 2000 after he had cited persecution in Russia. Shortly before his death, he issued a statement accusing Russian President Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin; (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer who holds the office of president of Russia. Putin has served continuously as president or prime minister since 1999: as prime min ...

of involvement in his assassination. Putin, a former KGB officer, denied any involvement in Litvinenko's death.

Targeted killing

Targeted killing is the intentional killing by a government or its agents of a civilian or "

Targeted killing is the intentional killing by a government or its agents of a civilian or "unlawful combatant

An unlawful combatant, illegal combatant or unprivileged combatant/belligerent is a person who directly engages in armed conflict in violation of the laws of war and therefore is claimed not to be protected by the Geneva Conventions.

The Internati ...

" who is not in the government's custody. The target is a person asserted to be taking part in an armed conflict or terrorism, by bearing arms or otherwise, who has thereby lost the immunity from being targeted that he would otherwise have under the Third Geneva Convention

The Third Geneva Convention, relative to the treatment of prisoners of war, is one of the four treaties of the Geneva Conventions. The Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War was first adopted in 1929, but significantl ...

. Note that it is a different term and concept from that of "targeted violence", as used by specialists who study violence.

On the other hand, Georgetown University Law Center

The Georgetown University Law Center (Georgetown Law) is the law school of Georgetown University, a private research university in Washington, D.C. It was established in 1870 and is the largest law school in the United States by enrollment and ...

Professor Gary D. Solis

Gary Dean Solis (born June 5, 1941) is a veteran of the U.S. Marine Corps and an adjunct professor of law who teaches the laws of war at the Georgetown University Law Center and the George Washington University Law School.

He attended San Diego S ...

, in his 2010 book ''The Law of Armed Conflict: International Humanitarian Law in War'', wrote, "Assassinations and targeted killings are very different acts." The use of the term "assassination" is opposed, as it denotes murder (unlawful killing), but the terrorists are targeted in self-defense, which is thus viewed as a killing but not a crime (justifiable homicide

The concept of justifiable homicide in criminal law is a defense to culpable homicide (criminal or negligent homicide). Generally, there is a burden of production of exculpatory evidence in the legal defense of justification. In most countri ...

).Targeted killing is a necessary option

', Sofaer, Abraham D.,

Hoover Institution

The Hoover Institution (officially The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace; abbreviated as Hoover) is an American public policy think tank and research institution that promotes personal and economic liberty, free enterprise, and ...

, March 26, 2004 Abraham D. Sofaer

Abraham David Sofaer (born May 6, 1938) is an American attorney and jurist who served as a United States federal judge, United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York and legal adviser to th ...

, former federal judge for the US District Court for the Southern District of New York

The United States District Court for the Southern District of New York (in case citations, S.D.N.Y.) is a federal trial court whose geographic jurisdiction encompasses eight counties of New York State. Two of these are in New York City: New ...

, wrote on the subject:

When people call a targeted killing an "assassination", they are attempting to preclude debate on the merits of the action. Assassination is widely defined as murder, and is for that reason prohibited in the United States ... U.S. officials may not kill people merely because their policies are seen as detrimental to our interests... But killings in self-defense are no more "assassinations" in international affairs than they are murders when undertaken by our police forces against domestic killers. Targeted killings in self-defense have been authoritatively determined by the federal government to fall outside the assassination prohibition.Author and former U.S. Army Captain Matthew J. Morgan argued that "there is a major difference between assassination and targeted killing... targeted killing snot synonymous with assassination. Assassination... constitutes an illegal killing." Similarly,

Amos Guiora

Amos N. Guiora is an Israeli-American professor of law at S. J. Quinney College of Law, University of Utah, specializing in institutional complicity, enabling culture, and sexual assaults. Guiora’s scholarship explores institutional complicity ...

, a professor of law at the University of Utah

The University of Utah (U of U, UofU, or simply The U) is a public research university in Salt Lake City, Utah. It is the flagship institution of the Utah System of Higher Education. The university was established in 1850 as the University of De ...

, wrote, "Targeted killing is... not an assassination." Steve David

Steve David (born 11 March 1951 in Point Fortin, Trinidad) is a Trinidadian former North American Soccer League and international football player.

Club career

David began his professional career with Police in Trinidad and Tobago. In 1974, he ...

, Professor of International Relations at Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private university, private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hem ...

, wrote, "There are strong reasons to believe that the Israeli policy of targeted killing is not the same as assassination." Syracuse Law Professor William Banks and GW Law Professor Peter Raven-Hansen wrote, "Targeted killing of terrorists is... not unlawful and would not constitute assassination." Rory Miller writes: "Targeted killing... is not 'assassination.'" Associate Professor Eric Patterson and Teresa Casale wrote, "Perhaps most important is the legal distinction between targeted killing and assassination."

On the other hand, the American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1920 "to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States". T ...

also states on its website, "A program of targeted killing far from any battlefield, without charge or trial, violates the constitutional guarantee of due process

Due process of law is application by state of all legal rules and principles pertaining to the case so all legal rights that are owed to the person are respected. Due process balances the power of law of the land and protects the individual pers ...

. It also violates international law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

, under which lethal force may be used outside armed conflict zones only as a last resort to prevent imminent threats, when non-lethal means are not available. Targeting people who are suspected of terrorism for execution, far from any war zone, turns the whole world into a battlefield."

Yael Stein, the research director of B'Tselem

B'Tselem ( he, בצלם, , " in the image of od) is a Jerusalem-based non-profit organization whose stated goals are to document human rights violations in the Israeli-occupied Palestinian territories, combat any denial of the existence of su ...

, the Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories, also stated in her article "By Any Name Illegal and Immoral: Response to 'Israel's Policy of Targeted Killing'":

The argument that this policy affords the public a sense of revenge and retribution could serve to justify acts both illegal and immoral. Clearly, lawbreakers ought to be punished. Yet, no matter how horrific their deeds, as the targeting of Israeli civilians indeed is, they should be punished according to the law. David's arguments could, in principle, justify the abolition of formal legal systems altogether.Targeted killing has become a frequent tactic of the United States and Israel in their fight against terrorism."Q&A: Targeted Killings"

Eben Kaplan, ''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', January 25, 2006. Retrieved October 8, 2010. The tactic can raise complex questions and lead to contentious disputes as to the legal basis for its application, who qualifies as an appropriate "hit list" target, and what circumstances must exist before the tactic may be used. Opinions range from people considering it a legal form of self-defense that reduces terrorism to people calling it an extrajudicial killing that lacks due process and leads to further violence. Methods used have included firing Hellfire missile

The AGM-114 Hellfire is an air-to-ground missile (AGM) first developed for anti-armor use, later developed for precision drone strikes against other target types, especially high-value targets. It was originally developed under the name '' Heli ...

s from Predator