Arthur Seaforth Blackburn on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 3rd Brigade was chosen as the

The 3rd Brigade was chosen as the

Blackburn, along with a group of four men, crawled forward to establish the source of the German machine gun fire, but all four of the men were killed, so he returned to his detachment. He went back to Robertson, who arranged support from trench mortars. Under the cover of this fire, Blackburn again went forward with some of his men, but another four were killed by machine gun fire. Another report to Robertson resulted in artillery support, and Blackburn was able to push forward another before being held up again, this time by German bombers. Under cover from friendly bombers, Blackburn and a sergeant crawled forward to reconnoitre, establishing that the Germans were holding a trench that ran at right angles to the one they were in. Blackburn then led his troops in the clearing of this trench, which was about long. During this fighting, four more men were killed, including the sergeant, but Blackburn and the remaining men were able to secure the trench and consolidate. Having captured the trench, Blackburn made another attempt to capture the strong point that was the source of the machine gun fire, but lost another five men. He, therefore, decided to hold the trench, which he did until 14:00, when he was relieved. By this time, forty of the seventy men that had been under his command during the day had been killed or wounded. Sometime that night, Blackburn took over command of D Company, but was relieved the following morning.

For his actions, Blackburn was recommended for the award of the

Blackburn, along with a group of four men, crawled forward to establish the source of the German machine gun fire, but all four of the men were killed, so he returned to his detachment. He went back to Robertson, who arranged support from trench mortars. Under the cover of this fire, Blackburn again went forward with some of his men, but another four were killed by machine gun fire. Another report to Robertson resulted in artillery support, and Blackburn was able to push forward another before being held up again, this time by German bombers. Under cover from friendly bombers, Blackburn and a sergeant crawled forward to reconnoitre, establishing that the Germans were holding a trench that ran at right angles to the one they were in. Blackburn then led his troops in the clearing of this trench, which was about long. During this fighting, four more men were killed, including the sergeant, but Blackburn and the remaining men were able to secure the trench and consolidate. Having captured the trench, Blackburn made another attempt to capture the strong point that was the source of the machine gun fire, but lost another five men. He, therefore, decided to hold the trench, which he did until 14:00, when he was relieved. By this time, forty of the seventy men that had been under his command during the day had been killed or wounded. Sometime that night, Blackburn took over command of D Company, but was relieved the following morning.

For his actions, Blackburn was recommended for the award of the  Blackburn was the first member of the 10th Battalion and first South Australian to be awarded the VC, and his VC was earned in the costliest battle in Australian history. He was discharged from hospital on 30 September, and attended an investiture at

Blackburn was the first member of the 10th Battalion and first South Australian to be awarded the VC, and his VC was earned in the costliest battle in Australian history. He was discharged from hospital on 30 September, and attended an investiture at

Blackburn returned to legal practice in early 1917, becoming a principal lawyer for the firm of Fenn and Hardy. In May 1917, Blackburn was elected as one of five vice-presidents of the Returned Soldiers' Association (RSA) in South Australia, which was led by the first commanding officer of the 10th Battalion, Weir. On 12 September, Blackburn was elected state president of the RSA. He was involved in the

Blackburn returned to legal practice in early 1917, becoming a principal lawyer for the firm of Fenn and Hardy. In May 1917, Blackburn was elected as one of five vice-presidents of the Returned Soldiers' Association (RSA) in South Australia, which was led by the first commanding officer of the 10th Battalion, Weir. On 12 September, Blackburn was elected state president of the RSA. He was involved in the  Blackburn was transferred from the 43rd Battalion to the 23rd Light Horse Regiment on 1 July 1928. In September and October 1928, Blackburn helped raise a volunteer force which was used to protect non-

Blackburn was transferred from the 43rd Battalion to the 23rd Light Horse Regiment on 1 July 1928. In September and October 1928, Blackburn helped raise a volunteer force which was used to protect non-

In mid-June, the battalion was committed to the

In mid-June, the battalion was committed to the  On the left flank of the Free French force was the Australian 2/3rd Infantry Battalion, attacking from the southwest towards the town of

On the left flank of the Free French force was the Australian 2/3rd Infantry Battalion, attacking from the southwest towards the town of  In the short lull after the fall of Damascus, Blackburn's men, less D Company, were scattered over a wide area of the central front supporting the infantry. Blackburn continued to visit his detachments, often displaying a disdainful attitude to incoming artillery fire which amazed his men. With the Vichy French stymied in the centre and the Allies unable to press forward from Damascus, the overall commander, now-Lieutenant General Lavarack, decided to put his main effort into the coastal push towards Beirut. D Company of the 2/3rd, split up among the various infantry battalions pushing up the coast road, fought at

In the short lull after the fall of Damascus, Blackburn's men, less D Company, were scattered over a wide area of the central front supporting the infantry. Blackburn continued to visit his detachments, often displaying a disdainful attitude to incoming artillery fire which amazed his men. With the Vichy French stymied in the centre and the Allies unable to press forward from Damascus, the overall commander, now-Lieutenant General Lavarack, decided to put his main effort into the coastal push towards Beirut. D Company of the 2/3rd, split up among the various infantry battalions pushing up the coast road, fought at

On 14 January 1942, following

On 14 January 1942, following  On 21 February, Blackburn was temporarily promoted to

On 21 February, Blackburn was temporarily promoted to  By 27 February, Blackburn had established his headquarters in

By 27 February, Blackburn had established his headquarters in

Brigadier

Brigadier is a military rank, the seniority of which depends on the country. In some countries, it is a senior rank above colonel, equivalent to a brigadier general or commodore, typically commanding a brigade of several thousand soldiers. In ...

Arthur Seaforth Blackburn, (25 November 1892 – 24 November 1960) was an Australian soldier, lawyer, politician, and recipient of the Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious award of the British honours system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British Armed Forces and may be awarded posthumously. It was previously ...

(VC), the highest award for valour in battle that could be awarded to a member of the Australian armed forces

The Australian Defence Force (ADF) is the military organisation responsible for the defence of the Commonwealth of Australia and its national interests. It consists of the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), Australian Army, Royal Australian Air Forc ...

at the time. A lawyer and part-time soldier prior to the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, Blackburn enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force in August 1914, and was assigned to the 10th Battalion. His unit landed at Anzac Cove, Gallipoli

The Gallipoli peninsula (; tr, Gelibolu Yarımadası; grc, Χερσόνησος της Καλλίπολης, ) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles ...

, on April 25, 1915, and he and another scout were credited with advancing the furthest inland on the day of the landing. Blackburn was later commissioned and, along with his battalion, spent the rest of the Gallipoli campaign fighting Ottoman forces.

The 10th Battalion was withdrawn from Gallipoli in November 1915, and after re-organising and training in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, sailed for the Western Front in late March 1916. It saw its first real fighting in France on 23 July during the Battle of Pozières

The Battle of Pozières (23 July – 3 September 1916) took place in northern France around the village of Pozières, during the Battle of the Somme. The costly fighting ended with the British in possession of the plateau north and east of the v ...

, part of the Battle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme ( French: Bataille de la Somme), also known as the Somme offensive, was a battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and French Third Republic against the German Empire. It took place bet ...

. It was during this battle that Blackburn's actions resulted in a recommendation for his award of the VC. Commanding 50 men, he led four separate sorties to drive the Germans from a strong point using hand grenades

A grenade is an explosive weapon typically thrown by hand (also called hand grenade), but can also refer to a shell (explosive projectile) shot from the muzzle of a rifle (as a rifle grenade) or a grenade launcher. A modern hand grenade ge ...

, capturing of trench. He was the first member of his battalion to be awarded the VC during World War I, and the first South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

n to receive the VC. He also fought in the Battle of Mouquet Farm

The Battle of Mouquet Farm, also known as the Fighting for Mouquet Farm was part of the Battle of the Somme and began during the Battle of Pozières (23 July – 3 September). The fighting began on 23 July with attacks by the British Reserve A ...

in August, before being evacuated to the United Kingdom and then Australia suffering from illness. He was medically discharged in early 1917.

Blackburn returned to legal practice and pursued a military career during the interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the World War I, First World War to the beginning of the World War II, Second World War. The in ...

, and served as a member of the South Australian parliament

The Parliament of South Australia is the bicameral legislature of the Australian state of South Australia. It consists of the 47-seat House of Assembly (lower house) and the 22-seat Legislative Council (upper house). General elections are held ...

in 1918–1921. He led the Returned Sailors' and Soldiers' Imperial League of Australia in South Australia for several years, and was appointed the coroner

A coroner is a government or judicial official who is empowered to conduct or order an inquest into Manner of death, the manner or cause of death, and to investigate or confirm the identity of an unknown person who has been found dead within th ...

for the city of Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The dem ...

, South Australia. After the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Blackburn was appointed to command the 2/3rd Machine Gun Battalion of the Second Australian Imperial Force

The Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF, or Second AIF) was the name given to the volunteer expeditionary force of the Australian Army in the Second World War. It was formed following the declaration of war on Nazi Germany, with an initial ...

, and led it during the Syria–Lebanon Campaign

The Syria–Lebanon campaign, also known as Operation Exporter, was the Allied invasion of Syria and Lebanon (then controlled by Vichy France) in June and July 1941, during the Second World War. The French had ceded autonomy to Syria in Septembe ...

against the Vichy French

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its terr ...

in 1941, during which he personally accepted the surrender of Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

. In early 1942, his battalion was withdrawn from the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

and played a role in the defence of Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's List ...

in the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, which ...

from the Japanese. Captured, Blackburn spent the rest of the war as a prisoner-of-war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

. After he was liberated in 1945, he returned to Australia and was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) for his services on Java in 1942.

Following the war, Blackburn was appointed as a conciliation commissioner of the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration

The Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration was an Australian court that operated from 1904 to 1956 with jurisdiction to hear and arbitrate interstate industrial disputes, and to make awards. It also had the judicial functions of in ...

until 1955 and in that year was made a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) for his services to the community. He died in 1960 and was buried with full military honours in the Australian Imperial Force section of the West Terrace Cemetery

The West Terrace Cemetery is South Australia's oldest cemetery, first appearing on Colonel William Light's 1837 plan of Adelaide. The site is located in Park 23 of the Adelaide Park Lands just south-west of the Adelaide city centre, between ...

, Adelaide. His Victoria Cross and other medals are displayed in the Hall of Valour at the Australian War Memorial

The Australian War Memorial is Australia's national memorial to the members of its armed forces and supporting organisations who have died or participated in wars involving the Commonwealth of Australia and some conflicts involving pe ...

.

Early life

Arthur Seaforth Blackburn was born on 25 November 1892 atWoodville, South Australia

Woodville is a suburb of Adelaide, situated about northwest of Adelaide city centre. It lies within the City of Charles Sturt. The postcode of Woodville is 5011. Woodville is bound by Cheltenham Parade to the west, Torrens Road to the north, Po ...

. He was the youngest child of Thomas Blackburn Thomas, Tom or Tommy Blackburn may refer to:

*Anthony Blackburn (born 1945), British vice-admiral and Equerry to the Royal Household, commonly known as Tom Blackburn

*Thomas Blackburn (entomologist) (1844–1912), Australian entomologist

*Thomas Bl ...

, an Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

canon

Canon or Canons may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Canon (fiction), the conceptual material accepted as official in a fictional universe by its fan base

* Literary canon, an accepted body of works considered as high culture

** Western can ...

and entomologist

Entomology () is the scientific study of insects, a branch of zoology. In the past the term "insect" was less specific, and historically the definition of entomology would also include the study of animals in other arthropod groups, such as arach ...

, and his second wife, Margaret Harriette Stewart, Browne. Arthur was initially educated at Pulteney Grammar School

Pulteney Grammar School is an independent, Anglican, co-educational, private day school. Founded in 1847 by members of the Anglican Church, it is the second oldest independent school in South Australia. Its campuses are located on South Terrace ...

. His mother died in 1904 at the age of 40. In 1906, he entered St Peter's College, Adelaide

, other_name = The Collegiate School of St Peter

, seal_image = St Peter's College, Adelaide Logo.svg

, seal_size = 150

, image = SPSC chapel and memorial hall.jpg

, image_size ...

, and this was followed by studies at the University of Adelaide

The University of Adelaide (informally Adelaide University) is a public research university located in Adelaide, South Australia. Established in 1874, it is the third-oldest university in Australia. The university's main campus is located on N ...

, where he completed a Bachelor of Laws

Bachelor of Laws ( la, Legum Baccalaureus; LL.B.) is an undergraduate law degree in the United Kingdom and most common law jurisdictions. Bachelor of Laws is also the name of the law degree awarded by universities in the People's Republic of Chi ...

in 1913, after being articled

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

to C.B.Hardy. During Blackburn's term as his articled clerk, on one occasion Hardy was assaulted by two men on the street, and despite his slight build, Blackburn intervened and chased them away. In 1911, compulsory military training had been introduced, and Arthur had joined the South Australian Scottish Regiment of the Citizen Military Forces

The Australian Army Reserve is a collective name given to the reserve units of the Australian Army. Since the Federation of Australia in 1901, the reserve military force has been known by many names, including the Citizens Forces, the Citizen ...

(CMF). He was called to the bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call to ...

on 13 December 1913. His half-brother

A sibling is a relative that shares at least one parent with the subject. A male sibling is a brother and a female sibling is a sister. A person with no siblings is an only child.

While some circumstances can cause siblings to be raised separat ...

, Charles Blackburn

Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Charles Bickerton Blackburn (22 April 1874 – 20 July 1972) was an Australian university chancellor and physician. Blackburn was born in Greenhithe, Kent, England, to the cleric and entomologist Thomas Blackburn (en ...

, became a prominent Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

doctor, served in the Australian Army Medical Corps

The Royal Australian Army Medical Corps (RAAMC) is the branch of the Australian Army responsible for providing medical care to Army personnel. The AAMC was formed in 1902 through the amalgamation of medical units of the various Australian coloni ...

in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, and later became a long-serving Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

of the University of Sydney

The University of Sydney (USYD), also known as Sydney University, or informally Sydney Uni, is a public research university located in Sydney, Australia. Founded in 1850, it is the oldest university in Australia and is one of the country's si ...

. Their father died in 1912. At the outbreak of World War I, Arthur was practising as a solicitor

A solicitor is a legal practitioner who traditionally deals with most of the legal matters in some jurisdictions. A person must have legally-defined qualifications, which vary from one jurisdiction to another, to be described as a solicitor and ...

in Adelaide with the firm of Nesbit and Nesbit, and was still serving in the CMF.

World War I

Gallipoli

On 19 August 1914, aged 21, Blackburn enlisted as aprivate

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* " In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorde ...

in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) and was assigned to the 10th Battalion, 3rd Brigade, 1st Division. The 10th Battalion underwent initial training at Morphettville

Morphettville is a suburb of Adelaide, South Australia in the City of Marion.

The northern part of the suburb is bounded by the Glenelg tram line, and fully occupied by the Morphettville Racecourse (horseracing track). The tram barn storage a ...

in Adelaide, South Australia, before embarking on at nearby Outer Harbor on 20 October. Sailing via Fremantle

Fremantle () () is a port city in Western Australia, located at the mouth of the Swan River in the metropolitan area of Perth, the state capital. Fremantle Harbour serves as the port of Perth. The Western Australian vernacular diminutive for ...

and Colombo

Colombo ( ; si, කොළඹ, translit=Koḷam̆ba, ; ta, கொழும்பு, translit=Koḻumpu, ) is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. According to the Brookings Institution, Colombo me ...

in Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, the ship arrived at Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, on 6 December. The troops went into camp near Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

. They trained there until 28 February 1915, when they moved to Alexandria. They embarked on on 1 March and a few days later arrived at the port of Mudros

Moudros ( el, Μούδρος) is a town and a former municipality on the island of Lemnos, North Aegean, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Lemnos, of which it is a municipal unit. It covers the entire eas ...

on the Greek island of Lemnos

Lemnos or Limnos ( el, Λήμνος; grc, Λῆμνος) is a Greek island in the northern Aegean Sea. Administratively the island forms a separate municipality within the Lemnos regional unit, which is part of the North Aegean region. The p ...

in the northeastern Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek language, Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish language, Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It ...

, where they remained aboard for the next seven weeks.

The 3rd Brigade was chosen as the

The 3rd Brigade was chosen as the covering force A covering force is a military force tasked with operating in conjunction with a larger force, with the role of providing a strong protective outpost line (including operating in advance of the main force), searching for and attacking enemy forces o ...

for the landing at Anzac Cove

The landing at Anzac Cove on Sunday, 25 April 1915, also known as the landing at Gaba Tepe and, to the Turks, as the Arıburnu Battle, was part of the amphibious invasion of the Gallipoli Peninsula by the forces of the British Empire, which ...

, Gallipoli

The Gallipoli peninsula (; tr, Gelibolu Yarımadası; grc, Χερσόνησος της Καλλίπολης, ) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles ...

, on 25 April, which marked the commencement of the Gallipoli campaign. The brigade embarked on the battleship and the destroyer , and after transferring to strings of rowing-boats initially towed by steam pinnaces, the battalion began rowing ashore at about 04:30. Blackburn was one of the battalion scouts, and among the first ashore.

Australia's World War I official war historian, Charles Bean

Charles Edwin Woodrow Bean (18 November 1879 – 30 August 1968), usually identified as C. E. W. Bean, was Australia's official war correspondent, subsequently its official war historian, who wrote six volumes and edited the remaining six of ...

, noted there was strong evidence that Blackburn, along with Lance Corporal

Lance corporal is a military rank, used by many armed forces worldwide, and also by some police forces and other uniformed organisations. It is below the rank of corporal, and is typically the lowest non-commissioned officer (NCO), usually equi ...

Philip Robin, probably made it further inland on the day of the landing than any other Australian soldiers whose movements are known, some . The 3rd Brigade covering force fell well short of its ultimate objective, the crest of a feature later known as "Scrubby Knoll", part of "Third (or Gun) Ridge", but Blackburn and Robin, who were sent ahead as scouts, got beyond it. Robin was killed in action three days after the landing. Later in life, Blackburn was modest and retiring about his and Robin's achievement, stating that it was "an absolute mystery" how they had survived, given the range at which they were being shot at and the men who were shot around them.

Blackburn participated in heavy fighting at the landing; by 30 April, the 10th Battalion had suffered 466 killed and wounded. He was soon promoted to lance corporal, and was placed in charge of the unit post office for one month shortly after his promotion. He was involved in subsequent trench warfare defending the beachhead

A beachhead is a temporary line created when a military unit reaches a landing beach by sea and begins to defend the area as other reinforcements arrive. Once a large enough unit is assembled, the invading force can begin advancing inland. The ...

, including the Turkish counter-attack of 19 May. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

on 4 August, and appointed as a platoon commander

{{unreferenced, date=February 2013

A platoon leader (NATO) or platoon commander (more common in Commonwealth militaries and the US Marine Corps) is the officer in charge of a platoon. This person is usually a junior officer – a second or firs ...

in A Company. Blackburn served at the front for the rest of the campaign, until the 10th Battalion was withdrawn to Lemnos in November, and subsequently back to Egypt. The battalion suffered over 700 casualties during the campaign, including 207 dead. The unit underwent re-organisation in Egypt, and on 20 February 1916, Blackburn was promoted to lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

. In early March, he was hospitalised for two weeks with neurasthenia

Neurasthenia (from the Ancient Greek νεῦρον ''neuron'' "nerve" and ἀσθενής ''asthenés'' "weak") is a term that was first used at least as early as 1829 for a mechanical weakness of the nerves and became a major diagnosis in North A ...

. The battalion sailed for France in late March, arriving in early April. By this time, Blackburn was posted to a platoon in D Company.

Western Front

Blackburn went on leave in France from 29 April to 7 May. The 10th Battalion entered the fighting on the Western Front in June, initially in the quietArmentières

Armentières (; vls, Armentiers) is a commune in the Nord department in the Hauts-de-France region in northern France. It is part of the Métropole Européenne de Lille.

The motto of the town is ''Pauvre mais fière'' (Poor but proud).

Geogra ...

sector of the front line. While in this area, Blackburn was selected as a member of a special raiding party led by Captain Bill McCann

Lieutenant Colonel William Francis James McCann, (19 April 1892 – 14 December 1957) was an Australian soldier of World War I, a barrister, and a prominent figure in the military and ex-service community of South Australia during the ...

. In the early hours of 23 July, the 10th Battalion was committed to its first significant action on the Western Front during the Battle of Pozières

The Battle of Pozières (23 July – 3 September 1916) took place in northern France around the village of Pozières, during the Battle of the Somme. The costly fighting ended with the British in possession of the plateau north and east of the v ...

, part of the Battle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme ( French: Bataille de la Somme), also known as the Somme offensive, was a battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and French Third Republic against the German Empire. It took place bet ...

. Initially, A Company under McCann were sent forward to assist the 9th Battalion, which was involved in a bomb (hand grenade

A grenade is an explosive weapon typically thrown by hand (also called hand grenade), but can also refer to a shell (explosive projectile) shot from the muzzle of a rifle (as a rifle grenade) or a grenade launcher. A modern hand grenade genera ...

) fight over the O.G.1 trench system. Held up by heavy machine gun fire and bombs, McCann, who had been wounded in the head, reported to the commanding officer

The commanding officer (CO) or sometimes, if the incumbent is a general officer, commanding general (CG), is the officer in command of a military unit. The commanding officer has ultimate authority over the unit, and is usually given wide latitu ...

(CO) of the 9th Battalion, Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

James Robertson, that more help was needed. About 05:30, a detachment of 50 men based on 16 Platoon, D Company, 10th Battalion, was then sent forward under Blackburn to drive the Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

out of a section of trench. Blackburn, finding that A Company had suffered heavy casualties, immediately led his men in rushing a barricade across the trench. Breaking it down, and using bombs, they pushed the Germans back. Beyond this point, preceding artillery bombardments had almost obliterated the trench, and forward movement was exposed to heavy machine gun fire.

Blackburn, along with a group of four men, crawled forward to establish the source of the German machine gun fire, but all four of the men were killed, so he returned to his detachment. He went back to Robertson, who arranged support from trench mortars. Under the cover of this fire, Blackburn again went forward with some of his men, but another four were killed by machine gun fire. Another report to Robertson resulted in artillery support, and Blackburn was able to push forward another before being held up again, this time by German bombers. Under cover from friendly bombers, Blackburn and a sergeant crawled forward to reconnoitre, establishing that the Germans were holding a trench that ran at right angles to the one they were in. Blackburn then led his troops in the clearing of this trench, which was about long. During this fighting, four more men were killed, including the sergeant, but Blackburn and the remaining men were able to secure the trench and consolidate. Having captured the trench, Blackburn made another attempt to capture the strong point that was the source of the machine gun fire, but lost another five men. He, therefore, decided to hold the trench, which he did until 14:00, when he was relieved. By this time, forty of the seventy men that had been under his command during the day had been killed or wounded. Sometime that night, Blackburn took over command of D Company, but was relieved the following morning.

For his actions, Blackburn was recommended for the award of the

Blackburn, along with a group of four men, crawled forward to establish the source of the German machine gun fire, but all four of the men were killed, so he returned to his detachment. He went back to Robertson, who arranged support from trench mortars. Under the cover of this fire, Blackburn again went forward with some of his men, but another four were killed by machine gun fire. Another report to Robertson resulted in artillery support, and Blackburn was able to push forward another before being held up again, this time by German bombers. Under cover from friendly bombers, Blackburn and a sergeant crawled forward to reconnoitre, establishing that the Germans were holding a trench that ran at right angles to the one they were in. Blackburn then led his troops in the clearing of this trench, which was about long. During this fighting, four more men were killed, including the sergeant, but Blackburn and the remaining men were able to secure the trench and consolidate. Having captured the trench, Blackburn made another attempt to capture the strong point that was the source of the machine gun fire, but lost another five men. He, therefore, decided to hold the trench, which he did until 14:00, when he was relieved. By this time, forty of the seventy men that had been under his command during the day had been killed or wounded. Sometime that night, Blackburn took over command of D Company, but was relieved the following morning.

For his actions, Blackburn was recommended for the award of the Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious award of the British honours system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British Armed Forces and may be awarded posthumously. It was previously ...

(VC), the highest award for gallantry

Gallantry may refer to:

* military courage or bravery

* Chivalry

* Warrior ethos

* Knightly Piety Knightly Piety refers to a specific strand of Christian belief espoused by knights during the Middle Ages. The term comes from ''Ritterfrömmigkei ...

in battle that could be awarded to a member of the Australian armed forces

The Australian Defence Force (ADF) is the military organisation responsible for the defence of the Commonwealth of Australia and its national interests. It consists of the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), Australian Army, Royal Australian Air Forc ...

at the time. Describing his actions in a letter to a friend, the normally retiring Blackburn said it was, "the biggest bastard of a job I have ever struck". In recommending him for the VC, his commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Stanley Price Weir, observed, "Matters looked anything but cheerful for Lieutenant Blackburn and his men, but Blackburn lost neither his heart nor his head".

The 10th Battalion was relieved from its positions at Pozières in the late evening of 25 July, having suffered 327 casualties in three days. Blackburn was temporarily promoted to the rank of captain on 1 August, due to the heavy losses. The battalion spent the next three weeks in rest areas, but returned to the fighting during the Battle of Mouquet Farm

The Battle of Mouquet Farm, also known as the Fighting for Mouquet Farm was part of the Battle of the Somme and began during the Battle of Pozières (23 July – 3 September). The fighting began on 23 July with attacks by the British Reserve A ...

on 19–23 August, incurring another 335 casualties from the 620 that were committed to the fighting. Following this battle, the 10th Battalion went into rest camp in Belgium, and on 8 September, Blackburn reported sick with pleurisy

Pleurisy, also known as pleuritis, is inflammation of the membranes that surround the lungs and line the chest cavity (pleurae). This can result in a sharp chest pain while breathing. Occasionally the pain may be a constant dull ache. Other sy ...

and was evacuated to the 3rd London General Hospital. He relinquished his temporary rank upon evacuation, and was placed on the seconded

In deliberative bodies a second to a proposed motion is an indication that there is at least one person besides the mover that is interested in seeing the motion come before the meeting. It does not necessarily indicate that the seconder favors th ...

list. Blackburn's VC citation was published on 9 September, and read:

Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a London royal residence and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and royal hospitality. It ...

on 4 October to receive his VC from King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Que ...

. The same day, McCann received the Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level pre-1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth countries.

The MC i ...

for his own actions at Pozières that immediately preceded those of Blackburn. Blackburn embarked at Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

for Australia aboard the hospital ship ''Karoola'' on 16 October for six months' rest, arriving home via Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

on 3 December. The train he arrived on was met by the state premier, Crawford Vaughan

Crawford Vaughan (14 July 1874 – 15 December 1947) was an Australian politician, and the Premier of South Australia from 1915 to 1917. He was a member of the South Australian House of Assembly from 1905 to 1918, representing Torrens (19 ...

, but he declined to speak to the assembled crowd about his exploits. The following day he was fêted by the staff and students of St Peter's College.

He married Rose Ada Kelly at the St Peter's College chapel on 22 March 1917; they had two sons and two daughters. Their sons were Richard

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Frankish language, Old Frankish and is a Compound (linguistics), compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic language, Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' an ...

and Robert; Richard also became a lawyer and eventually became an eminent jurist, chief justice of the Supreme Court of the Australian Capital Territory

The Supreme Court of the Australian Capital Territory is the highest court of the Australian Capital Territory (ACT). It has unlimited jurisdiction within the territory in Civil law (common law), civil matters and hears the most serious Criminal ...

and chancellor of the Australian National University

The Australian National University (ANU) is a public research university located in Canberra, the capital of Australia. Its main campus in Acton encompasses seven teaching and research colleges, in addition to several national academies and ...

. His daughter Margaret married Jim Forbes, who became a long-serving federal government minister, and his other daughter Rosemary

''Salvia rosmarinus'' (), commonly known as rosemary, is a shrub with fragrant, evergreen, needle-like leaves and white, pink, purple, or blue flowers, native plant, native to the Mediterranean Region, Mediterranean region. Until 2017, it was kn ...

became a literary editor A literary editor is an editor in a newspaper, magazine or similar publication who deals with aspects concerning literature and books, especially reviews.

, author, and adviser to the South Australian government

The Government of South Australia, also referred to as the South Australian Government, SA Government or more formally, His Majesty’s Government, is the Australian state democratic administrative authority of South Australia. It is modelled o ...

on women's affairs. Blackburn was discharged from the AIF on medical grounds on 10 April 1917, as he was classified as too ill to return to the fighting. He was awarded an invalid soldier's pension. In addition to his VC, Blackburn also received the 1914–15 Star

The 1914–15 Star is a campaign medal of the British Empire which was awarded to officers and men of British and Imperial forces who served in any theatre of the First World War against the Central European Powers during 1914 and 1915. The me ...

, British War Medal

The British War Medal is a campaign medal of the United Kingdom which was awarded to officers and men of British and Imperial forces for service in the First World War. Two versions of the medal were produced. About 6.5 million were struck in si ...

and Victory Medal for his service in World War I. His brothers Harry and John also served in the AIF during the war.

Between the wars

Blackburn returned to legal practice in early 1917, becoming a principal lawyer for the firm of Fenn and Hardy. In May 1917, Blackburn was elected as one of five vice-presidents of the Returned Soldiers' Association (RSA) in South Australia, which was led by the first commanding officer of the 10th Battalion, Weir. On 12 September, Blackburn was elected state president of the RSA. He was involved in the

Blackburn returned to legal practice in early 1917, becoming a principal lawyer for the firm of Fenn and Hardy. In May 1917, Blackburn was elected as one of five vice-presidents of the Returned Soldiers' Association (RSA) in South Australia, which was led by the first commanding officer of the 10th Battalion, Weir. On 12 September, Blackburn was elected state president of the RSA. He was involved in the 1917 Australian conscription referendum

The 1917 Australian plebiscite was held on 20 December 1917. It contained one question.

* ''Are you in favour of the proposal of the Commonwealth Government for reinforcing the Australian Imperial Force oversea?''

Background

The 1917 plebisci ...

campaign, advocating in favour of conscription. As RSA president, he was involved in advocating for returned soldiers, and navigated a contentious period in the organisation's history. He also led the fundraising for a soldiers' memorial to be built in Adelaide. In January 1918, he was re-elected unopposed as president.

Despite his push for the RSA to remain independent of politics, in early April 1918, Blackburn successfully contested the three-member South Australian House of Assembly

The House of Assembly, or lower house, is one of the two chambers of the Parliament of South Australia. The other is the Legislative Council. It sits in Parliament House in the state capital, Adelaide.

Overview

The House of Assembly was creat ...

seat of Sturt as a National Party candidate, and on 6 April he was elected first of the three with 19.2 per cent of the vote. As a parliamentarian, Blackburn's speeches were generally about issues affecting those still serving overseas, as well as returned soldiers. A notable exception was his successful motion in favour of a profit-sharing

Profit sharing is various incentive plans introduced by businesses that provide direct or indirect payments to employees that depend on company's profitability in addition to employees' regular salary and bonuses. In publicly traded companies th ...

system for industrial employees. He advocated several radical ideas in his time as a parliamentarian, including removing all single men from the state public service so they would be free to enlist. He was also criticised in Parliament for not paying due attention to important legislation regarding ex-soldiers. This criticism even extended to attacks from another AIF man, Bill Denny, from the opposition Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also simply known as Labor, is the major centre-left political party in Australia, one of two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-right Liberal Party of Australia. The party forms the f ...

(ALP). According to his biographer Andrew Faulkner, his time in Parliament showed Blackburn to be a man of few words, but his words were chosen well and delivered with authority.

On 29 August 1918, he was appointed a justice of the peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or ''puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission ( letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the sa ...

, and in November, he became a Freemason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

with the St Peter's Collegiate Lodge. In July 1919, the Returned Sailors' and Soldiers' Imperial League of Australia (RSSILA), which had succeeded the RSA, held its annual congress in Adelaide. Among the motions that Blackburn moved was one calling on the federal government to ensure that a suitable headstone was erected over the grave of every sailor and soldier killed during the war. He also railed against delays in the deferred pay of dead soldiers being paid to their widows.

In January 1920, Blackburn was re-elected as state president of the RSSILA, although this was the first time he was opposed for the post, and he only won narrowly. By this time he had built the state branch of the organisation to 17,000 members. During that year, he hosted visits by two notables; Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, ordinarily senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army and as such few persons are appointed to it. It is considered as ...

William Birdwood

Field Marshal William Riddell Birdwood, 1st Baron Birdwood, (13 September 1865 – 17 May 1951) was a British Army officer. He saw active service in the Second Boer War on the staff of Lord Kitchener. He saw action again in the First World War ...

, and the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

, who later became King Edward VIII

Edward VIII (Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David; 23 June 1894 – 28 May 1972), later known as the Duke of Windsor, was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Empire and Emperor of India from 20 January 1 ...

. In accordance with normal procedures, while serving in the AIF, Blackburn had been appointed an honorary lieutenant in the CMF on 20 February 1916 on the Reserve of Officers List. This appointment was made substantive on 1 October 1920, still on the Reserve of Officers List. Continuing to practise law while a member of Parliament made for a heavy workload, and Blackburn did not seek re-election in 1921. In the same year he relinquished his role as state president of RSSILA, but he continued to be a fierce advocate for returned soldiers.

On 30 October 1925, Blackburn was transferred as a lieutenant from the Reserve of Officers List to the part-time 43rd Battalion of the CMF. In the same year, along with McCann, he formed the legal firm Blackburn and McCann, continuing the association they had during the fighting at Pozières. On 21 February 1927, Blackburn was promoted to captain, still serving with the 43rd Battalion. In early 1928, Blackburn became a foundation member of the Legacy Club of Adelaide, established to assist the dependents of deceased ex-servicemen; he later became its second president. In this role, he created a Junior Legacy Club for teenage sons of men who had died, which conducted activities such as camps and sports.

Blackburn was transferred from the 43rd Battalion to the 23rd Light Horse Regiment on 1 July 1928. In September and October 1928, Blackburn helped raise a volunteer force which was used to protect non-

Blackburn was transferred from the 43rd Battalion to the 23rd Light Horse Regiment on 1 July 1928. In September and October 1928, Blackburn helped raise a volunteer force which was used to protect non-union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

labour in an industrial dispute on the wharves at Port Adelaide

Port Adelaide is a port-side region of Adelaide, approximately northwest of the Adelaide CBD. It is also the namesake of the City of Port Adelaide Enfield council, a suburb, a federal and state electoral division and is the main port for the ...

and Outer Harbor. Initially called the "Essential Services Maintenance Volunteers" (ESMV) then the "Citizen's Defence Brigade", the men of this organisation, armed with government-issued rifles and bayonets, were deployed by the South Australia Police

South Australia Police (SAPOL) is the police force of the Australian state of South Australia. SAPOL is an independent statutory agency of the Government of South Australia directed by the Commissioner of Police, who reports to the Minister for ...

to intervene in the dispute between union and non-union labour on the docks. There was no fighting between the force and the strikers, and the dispute was resolved by early October.

Following the amalgamation of light horse regiments, Blackburn was transferred to the 18th/23rd Light Horse Regiment on 1 July 1930, and to the 18th Light Horse (Machine Gun) Regiment on 1 October of the same year. In 1933, Blackburn became the coroner

A coroner is a government or judicial official who is empowered to conduct or order an inquest into Manner of death, the manner or cause of death, and to investigate or confirm the identity of an unknown person who has been found dead within th ...

of the city of Adelaide, a position he held for fourteen years, with leave of absence during his World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

service. In this role, he was criticised for refusing to offer public explanations for his decisions not to hold inquests; it was criticism he ignored. The ALP attacked Blackburn's decision-making as coroner, according to Faulkner, this was probably influenced by his involvement with the ESMV in 1928 and his alignment with conservative politics. They were joined by the editor of ''The News'', who ran several editorials criticising Blackburn. In his role, Blackburn often dealt with deaths of returned soldiers, and murders committed by them. On 6 May 1935, Blackburn was awarded the King George V Silver Jubilee Medal

The King George V Silver Jubilee Medal is a commemorative medal, instituted to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the accession of King George V.

Issue

This medal was awarded as a personal souvenir by King George V to commemorate his Silver J ...

. He was promoted to major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

on 15 January 1937, still with the same regiment, and in the same year was awarded the King George VI Coronation Medal

The King George VI Coronation Medal was a commemorative medal, instituted to celebrate the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth.

Issue

This medal was awarded as a personal souvenir of King George VI's coronation. It was awarded to th ...

. On 1 July 1939, a few months before the outbreak of World War II, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and appointed to command the 18th Light Horse (Machine Gun) Regiment.

World War II

Blackburn stopped practising law in 1940, and on 20 June was appointed to raise and command the 2/3rd Machine Gun Battalion, part of theSecond Australian Imperial Force

The Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF, or Second AIF) was the name given to the volunteer expeditionary force of the Australian Army in the Second World War. It was formed following the declaration of war on Nazi Germany, with an initial ...

raised for service overseas during World War II. He was one of only three Australian World War I VC recipients to volunteer for overseas service in World War II. Eleven of the officers selected by Blackburn for his new unit were former officers of the 18th Light Horse (Machine Gun) Regiment, including the battalion second-in-command, Major Sid Reed, who was to prove valuable in moderating Blackburn's temper at times. The unit was raised in four different states; headquarters and A Company in South Australia, B Company in Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

, C Company in Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

and D Company in Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to th ...

. It concentrated in Adelaide on 31 October, after which Blackburn moulded the separately raised companies into one organisation. Multi-day route marches featured strongly in their training; Blackburn invariably marched at the front of his battalion. After undergoing training, the battalion entrained for Sydney where it embarked on on 10 April 1941. The battalion sailed for the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

via Colombo, where they had ten days' leave, and disembarked in Egypt on 14 May. Upon arrival, the battalion was assigned to the 7th Division in Palestine, where it underwent further training at a camp just north of Gaza.

Syria–Lebanon campaign

In mid-June, the battalion was committed to the

In mid-June, the battalion was committed to the Syria–Lebanon campaign

The Syria–Lebanon campaign, also known as Operation Exporter, was the Allied invasion of Syria and Lebanon (then controlled by Vichy France) in June and July 1941, during the Second World War. The French had ceded autonomy to Syria in Septembe ...

against the Vichy French

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its terr ...

in the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon

The Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon (french: Mandat pour la Syrie et le Liban; ar, الانتداب الفرنسي على سوريا ولبنان, al-intidāb al-fransi 'ala suriya wa-lubnān) (1923−1946) was a League of Nations mandate foun ...

. Due to the involvement of Vichy French and Free French

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exile ...

troops on opposite sides, the campaign was politically sensitive and as a result of heavy censorship not widely reported in Australia at the time; the nature of the fighting, where it was reported, was also played down as the Vichy forces outnumbered the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

and were also better equipped. The Allied plan involved four axes of attack, with the 7th Division committed mainly to the coastal drive on Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

in Lebanon and the central thrusts towards Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

in Syria. Blackburn initially divided his time between divisional headquarters in Palestine and the front, while three companies of the 2/3rd, along with a battery of anti-tank guns

Anti-tank warfare originated from the need to develop technology and tactics to destroy tanks during World War I. Since the Triple Entente deployed the first tanks in 1916, the German Empire developed the first anti-tank weapons. The first devel ...

, were the only divisional reserve

Reserve or reserves may refer to:

Places

* Reserve, Kansas, a US city

* Reserve, Louisiana, a census-designated place in St. John the Baptist Parish

* Reserve, Montana, a census-designated place in Sheridan County

* Reserve, New Mexico, a US vi ...

.

The 2/3rd were fully committed on 15 June, when the commander of I Corps I Corps, 1st Corps, or First Corps may refer to:

France

* 1st Army Corps (France)

* I Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* I Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French A ...

, the Australian Major General John Lavarack

Lieutenant General Sir John Dudley Lavarack, (19 December 1885 – 4 December 1957) was an Australian Army officer who was Governor of Queensland from 1 October 1946 to 4 December 1957, the first Australian-born governor of that state.

Early l ...

, committed the divisional reserve to secure a bridge across the Jordan River

The Jordan River or River Jordan ( ar, نَهْر الْأُرْدُنّ, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn'', he, נְהַר הַיַּרְדֵּן, ''Nəhar hayYardēn''; syc, ܢܗܪܐ ܕܝܘܪܕܢܢ ''Nahrāʾ Yurdnan''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Shariea ...

and thwart a major Vichy French counter-stroke that threatened to derail the campaign. This involved a blacked-out night-time drive of at relatively high speed over rough and treacherous roads to the bridge; Blackburn drove in advance of his force. On arrival, he was ordered to detach one of his companies north to block the road from Metulla

Metula ( he, מְטֻלָּה) is a town in the Northern District of Israel. Metula is located next to the northern border with Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the L ...

. Blackburn then led A Company on another drive before returning to check on the dispositions of his remaining troops at the bridge, near which he established his headquarters. Also on the 15th, D Company was detached from the battalion to support the coastal advance, and remained so throughout the campaign.

During the day a British staff officer arrived and directed Blackburn to send a company, two anti-tank guns and two armoured cars loaded with ammunition to Quneitra

, ''Qunayṭrawi'' or ''Qunayṭirawi''

, population_density_metro_sq_mi =

, population_urban =

, population_density_urban_km2 =

, population_density_urban_sq_mi =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_bla ...

, which Blackburn understood to have surrendered to the Vichy French. Blackburn baulked at this further splitting of his force, but when the order was confirmed by higher headquarters, early on 16 June he sent the scratch force of around 200 men north. The force took up positions on a ridge overlooking the town, but soon gathered intelligence that 1,500 Vichy French were holding the town, supported by numerous tanks and armoured cars. Blackburn, very concerned about his vanguard

The vanguard (also called the advance guard) is the leading part of an advancing military formation. It has a number of functions, including seeking out the enemy and securing ground in advance of the main force.

History

The vanguard derives fr ...

, decided to go forward to the ridge himself to check on dispositions. In the meantime, the company commander in that location tried to coax the Vichy French tanks to within range of his anti-tank guns, to no avail. Prior to Blackburn's arrival, a British battery of Ordnance QF 25-pounder

The Ordnance QF 25-pounder, or more simply 25-pounder or 25-pdr, was the major British field gun and howitzer during the Second World War. Its calibre is 3.45-inch (87.6 mm). It was introduced into service just before the war started, combin ...

field guns arrived. In a further effort to draw out the Vichy French, Blackburn personally drove his staff car forward and round in circles in an exposed position, but again the Vichy French did not take the bait. Late in the day, a battalion of British infantry arrived and, under covering fire from the machine gunners, attacked and captured the town; the 25-pounders knocked out three Vichy French armoured cars. Blackburn's advance force had made a significant contribution to stopping the Vichy French counter-stroke.

Blackburn's area of responsibility was briefly expanded to include all the routes east of the Jordan as far as Quneitra. To cover this he was allocated squadrons of light tanks and Bren carriers, as well as a British dressing station

A field hospital is a temporary hospital or mobile medical unit that takes care of casualties on-site before they can be safely transported to more permanent facilities. This term was initially used in military medicine (such as the Mobile A ...

to handle casualties. On 19 June his force was ordered forward towards Damascus. This involved a drive to Sheikh Meskine then a journey north, which took nearly two days due to the state of the roads. Meanwhile, Blackburn was recalled to Rosh Pinna

Rosh Pina or Rosh Pinna ( he, רֹאשׁ פִּנָּה, lit. ''Cornerstone'') is a local council in the Korazim Plateau in the Upper Galilee on the eastern slopes of Mount Kna'an in the Northern District of Israel. It was established as Gei ...

in Palestine to receive orders from the commander of the Damascus front, Major General John Fullerton Evetts

Lieutenant General Sir John Fullerton Evetts CB, CBE, MC (30 June 1891 – 21 December 1988) was a senior British Army officer.

Early life and First World War

Born in 1891 in Naini Tal, West Bengal, India, John Fullerton Evetts was educated a ...

of the British 6th Infantry Division 6th Division may refer to:

Infantry divisions

* 6th Division (Australia)

* 6th Division (Austria)

*6th (United Kingdom) Division

* Finnish 6th Division (Winter War)

*Finnish 6th Division (Continuation War)

* 6th Division (Reichswehr)

* 6th Divisi ...

, who directed him to assist the "weary and disheartened" Free French forward to Damascus. To achieve this task, his force was trimmed to a reinforced company of the 2/3rd and five anti-tank guns, totalling around 400 men. Blackburn arrived at Free French headquarters on 20 June, where he was told that their attack had faltered about south of Damascus.

On the left flank of the Free French force was the Australian 2/3rd Infantry Battalion, attacking from the southwest towards the town of

On the left flank of the Free French force was the Australian 2/3rd Infantry Battalion, attacking from the southwest towards the town of Mezze

Meze or mezza (, ) is a selection of small dishes served as appetizers in the Levantine cuisine, Levant, Turkish cuisine, Turkey, Greek cuisine, Greece, the Balkan cuisine, Balkans, the Caucasian cuisine, Caucasus and Iranian cuisine, Iran. It i ...

to the west of Damascus. The planned Free French attack was scheduled to go forward at 17:00, but they did not move. Blackburn again drove forward, but the Free French again refused to budge. To get the attack moving, Blackburn ordered one platoon of machine gunners forward to a trench about closer to Damascus. The Vichy French did not fire on them, and the couple of Vichy French tanks that appeared were engaged with Boys anti-tank rifle

The Boys anti-tank rifle (officially Rifle, Anti-Tank, .55in, Boys, and sometimes incorrectly spelled "Boyes"), is a British anti-tank rifle used during the Second World War. It was often nicknamed the "elephant gun" by its users due to its si ...

s. The Senegal

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: 𞤅𞤫𞤲𞤫𞤺𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Senegaali); Arabic: السنغال ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''Réewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 � ...

ese Free French troops then came forward to the Australian-held trench. Blackburn then ordered the rest of his men forward. This process, of the Australian machine gunners advancing and the Free French following, was repeated by Blackburn until the forward troops had advanced a total of and reached the outskirts of Damascus. In the latter stages, the Vichy French began to respond with small arms and artillery, and their tanks and snipers forced a halt for the night.

In the meantime, the 2/3rd Infantry Battalion had captured Vichy French positions to the west of Damascus and cut the road to Beirut. In the morning of 21 June, the Free French began to advance; Blackburn's machine gunners supported them and protected their right flank in case of a Vichy French counter-attack from the east. About 11:00 a Vichy French column emerged from Damascus led by a car bearing a white flag. After some discussions, Blackburn accompanied the Vichy French and Free French back into the city, where Blackburn, as the senior Allied commander present, accepted the surrender. Meanwhile, the Vichy French thrust towards Metulla had not reached A Company, and on 16 June the company was ordered forward into support positions for an attack by the 2/2nd Pioneer Battalion on a fort at Merdjayoun. Over several days, the pioneers, fighting as infantry, and the 2/25th Battalion were pitted against the well-held Vichy French positions, until the defenders withdrew on the night of 23 June.

Damour

Damour ( ar, الدامور) is a Lebanese Christian town that is south of Beirut. The name of the town is derived from the name of the Phoenician god Damoros who symbolized immortality ( in Arabic). Damour also remained the capital of Mount ...

in early July, before the Vichy French requested an armistice in mid-July. The battalion suffered 43 casualties during the campaign; nine dead and 34 wounded. At the end of July, Blackburn left the battalion to join the Allied Control Commission

Following the termination of hostilities in World War II, the Allies were in control of the defeated Axis countries. Anticipating the defeat of Germany and Japan, they had already set up the European Advisory Commission and a proposed Far Eastern ...

for Syria in Beirut, responsible, among other functions, for the repatriation of French prisoners-of-war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war ...

(POW). He seconded several officers from the 2/3rd to help him, and travelled widely around Syria, and even managed a brief crossing into Turkey. He became involved in trying to arbitrate in the fractious relationship between the captured Vichy French and the Free French who wanted to recruit them, but the Free French were largely unsuccessful in this endeavour, with only 5,700 of the remaining fit 28,000 Vichy soldiers joining their cause.

In the aftermath of the campaign, the 2/3rd stayed on as part of the Allied occupation force established in Syria and Lebanon to defend against a possible drive south by Axis forces through the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historically ...

. The battalion defended a position northeast of Beirut, around Bikfaya

Bikfaya ( ar, بكفيا, also spelled Bickfaya, Beckfayya, or Bekfaya) is a town in the Matn District region of Mount Lebanon. Its stone houses with red-tiled roofs resting amidst pine and oak forests make Bikfaya one of the most sought-after sub ...

initially, but was moved around to various locations including Aleppo

)), is an adjective which means "white-colored mixed with black".

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_caption =

, image_map1 =

...

on the Turkish border throughout the remainder of 1941. They endured a bitter cold and snowy winter at Fih near Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis may refer to:

Cities and other geographic units Greece

*Tripoli, Greece, the capital of Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in ...

, which was punctuated by leave drafts to Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( he, תֵּל־אָבִיב-יָפוֹ, translit=Tēl-ʾĀvīv-Yāfō ; ar, تَلّ أَبِيب – يَافَا, translit=Tall ʾAbīb-Yāfā, links=no), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the G ...

. By this time, Blackburn had returned to the battalion after a stint as president of a court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

and another inquiry, where his legal skills were put to good use. At Christmas, Blackburn's son, Richard

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Frankish language, Old Frankish and is a Compound (linguistics), compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic language, Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' an ...

, visited him, on leave from the 9th Division Cavalry Regiment, which was in Palestine.

Java

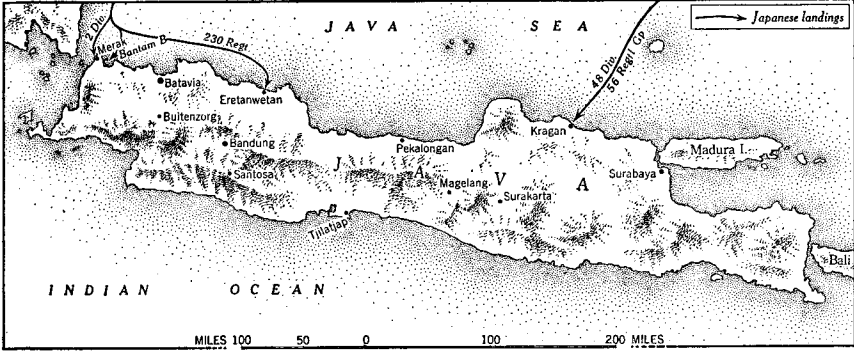

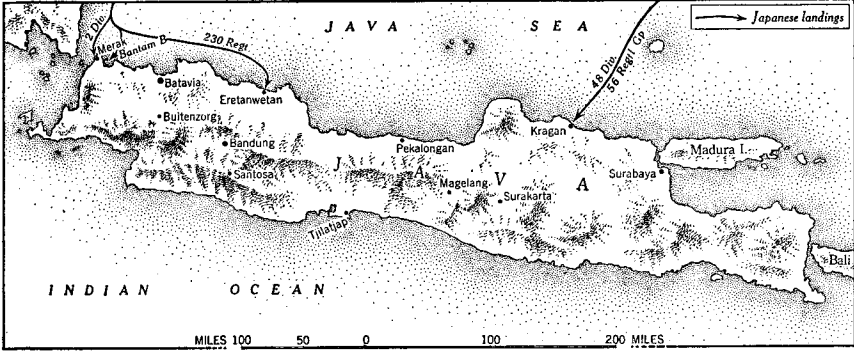

On 14 January 1942, following

On 14 January 1942, following Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

's entry into the war, the 2/3rd left Fih and travelled south into Palestine. On 1 February, the battalion, less one company and with no machine guns or vehicles, left the Middle East on . Also on ''Orcades'' were the 2/2nd Pioneer Battalion, engineers of the 2/6th Field Company, elements of the 2/2nd Anti-Aircraft Regiment and 2/1st Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, the 105th General Transport Company, 2/2nd Casualty Clearing Station, and sundry others. The ship, rated for 2,000 passengers, was loaded with 3,400. Blackburn, as senior officer on board, was appointed as the commander of the embarked troops, and ensured that the soldiers were kept busy with air raid and lifeboat drills, physical training and lectures. On 10 February, the ship departed Colombo, escorted by British, and later, Australian warships.

Blackburn received orders to put 2,000 of his men ashore at Oosthaven on Sumatra

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent i ...

in the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, which ...

to help defend an airfield near Palembang

Palembang () is the capital city of the Indonesian province of South Sumatra. The city proper covers on both banks of the Musi River on the eastern lowland of southern Sumatra. It had a population of 1,668,848 at the 2020 Census. Palembang ...

, about north of the port. These men were to be known as "Boostforce". This was in accordance with a plan that involved the 6th and 7th Divisions defending Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's List ...

and Sumatra respectively. Due to a lack of small arms

A firearm is any type of gun designed to be readily carried and used by an individual. The term is legally defined further in different countries (see Legal definitions).

The first firearms originated in 10th-century China, when bamboo tubes c ...

, some of the troops were equipped with weapons from ''Orcades'' armoury

An arsenal is a place where arms and ammunition are made, maintained and repaired, stored, or issued, in any combination, whether privately or publicly owned. Arsenal and armoury (British English) or armory (American English) are most ...