Artaud I, Count Of Forez on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

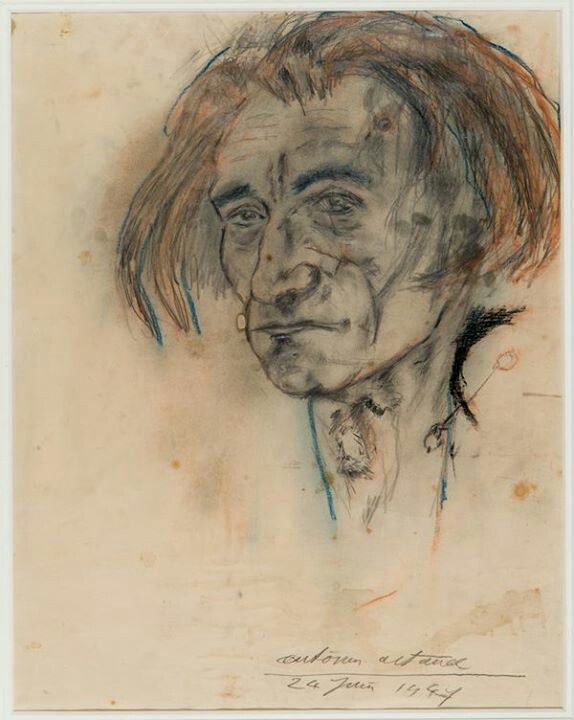

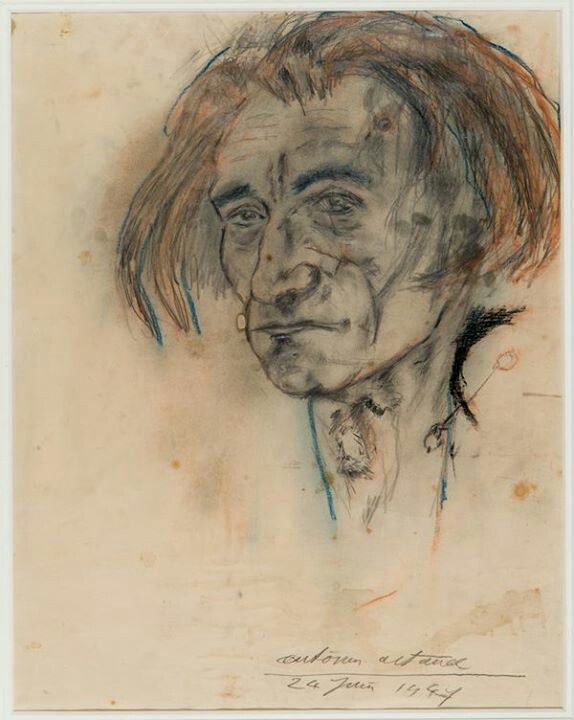

Antoine Marie Joseph Paul Artaud, better known as Antonin Artaud (; 4 September 1896 – 4 March 1948), was a French writer, poet, dramatist, visual artist, essayist, actor and theatre director. He is widely recognized as a major figure of the European

Artaud also had an active career in the cinema working as a critic, actor, and writer. Artaud's performance as

Artaud also had an active career in the cinema working as a critic, actor, and writer. Artaud's performance as

avant-garde

The avant-garde (; In 'advance guard' or ' vanguard', literally 'fore-guard') is a person or work that is experimental, radical, or unorthodox with respect to art, culture, or society.John Picchione, The New Avant-garde in Italy: Theoretical ...

. In particular, he had a profound influence on twentieth-century theatre

Twentieth-century theatre describes a period of great change within the theatrical culture of the 20th century, mainly in Europe and North America. There was a widespread challenge to long-established rules surrounding theatrical representation; ...

through his conceptualization of the Theatre of Cruelty

The Theatre of Cruelty (french: Théâtre de la Cruauté, also french: Théâtre cruel) is a form of theatre generally associated with Antonin Artaud. Artaud, who was briefly a member of the surrealist movement, outlined his theories in ''The Theat ...

. Known for his raw, surreal and transgressive work, his texts explored themes from the cosmologies of ancient cultures, philosophy, the occult, mysticism

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight in u ...

and indigenous Mexican and Balinese practices.

Early life

Antonin Artaud was born inMarseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Franc ...

, to Euphrasie Nalpas and Antoine-Roi Artaud. His parents were first cousins—his grandmothers were sisters from Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

(modern day İzmir

İzmir ( , ; ), also spelled Izmir, is a metropolitan city in the western extremity of Anatolia, capital of the province of the same name. It is the third most populous city in Turkey, after Istanbul and Ankara and the second largest urban agglo ...

, Turkey). His paternal grandmother, Catherine Chilé, was raised in Marseille, where she married Marius Artaud, a Frenchman. His maternal grandmother, Mariette Chilé, grew up in Smyrna, where she married Louis Nalpas, a local ship chandler

A ship chandler is a retail dealer who specializes in providing supplies or equipment for ships.

Synopsis

For traditional sailing ships, items that could be found in a chandlery

include sail-cloth, rosin, turpentine, tar, pitch, linseed oil, ...

. He was, throughout his life, greatly affected by his Greek ancestry.

Euphrasie gave birth to nine children, but four were stillborn and two others died in childhood. Artaud was diagnosed with meningitis

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges. The most common symptoms are fever, headache, and neck stiffness. Other symptoms include confusion or ...

at age five, a disease which had no cure at the time. Biographer David Shafer points out, "given the frequency of such misdiagnoses, coupled with the absence of a treatment (and consequent near-minimal survival rate) and the symptoms he had, it's unlikely that Artaud actually contracted it."

From 1907 to 1914, Artaud attended the Collége Sacré-Coeur. Here he began reading works by Arthur Rimbaud

Jean Nicolas Arthur Rimbaud (, ; 20 October 1854 – 10 November 1891) was a French poet known for his transgressive and surreal themes and for his influence on modern literature and arts, prefiguring surrealism. Born in Charleville, he starte ...

, Stéphane Mallarmé

Stéphane Mallarmé ( , ; 18 March 1842 – 9 September 1898), pen name of Étienne Mallarmé, was a French poet and critic. He was a major French symbolist poet, and his work anticipated and inspired several revolutionary artistic schools of ...

, and Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; Edgar Poe; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic. Poe is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales of mystery and the macabre. He is wide ...

and founded a private literary magazine in collaboration with his friends. At the end of college he started to noticeably withdraw from social life and "destroyed most of his written work and gave away his books.":3 Distressed, his parents arranged for him to see a psychiatrist.:25

Over the next five years Artaud was admitted to a series of sanatoria

A sanatorium (from Latin '' sānāre'' 'to heal, make healthy'), also sanitarium or sanitorium, are antiquated names for specialised hospitals, for the treatment of specific diseases, related ailments and convalescence. Sanatoriums are often ...

.:163 There was a pause in his treatment in 1916, when Artaud was conscripted

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day und ...

into the French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (french: Armée de Terre, ), is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces. It is responsible to the Government of France, along with the other components of the Armed For ...

.:26 He was discharged due to "an unspecified health reason" (Artaud would later claim it was "due to sleepwalking", while his mother ascribed it to his "nervous condition").:4 In May 1919, the director of the sanatorium prescribed laudanum for Artaud, precipitating a lifelong addiction to that and other opiate

An opiate, in classical pharmacology, is a substance derived from opium. In more modern usage, the term ''opioid'' is used to designate all substances, both natural and synthetic, that bind to opioid receptors in the brain (including antagonis ...

s.:162 In March 1921, Artaud moved to Paris where he was put under the psychiatric care of Dr Édouard Toulouse who took him in as a boarder.:29

Career

Theatrical apprenticeships

In Paris, Artaud worked with a number of celebrated French "teacher-directors". This includedJacques Copeau

Jacques Copeau (; 4 February 1879 – 20 October 1949) was a French theatre director, producer, actor, and dramatist. Before he founded the Théâtre du Vieux-Colombier in Paris, he wrote theatre reviews for several Parisian journals, work ...

, André Antoine

André Antoine (31 January 185823 October 1943) was a French actor, theatre manager, film director, author, and critic who is considered the father of modern mise en scène in France.

Biography

André Antoine was a clerk at the Paris Gas Utilit ...

, Georges and Ludmilla Pitoëff

Ludmilla Pitoëff (December 25, 1896 – September 15, 1951) was a Russian-born French stage actress. She also appeared in London and New York, as well as in some films.

Biography

Born in Tiflis, Russia on December 25, 1896, she married Georg ...

, Charles Dullin

Charles Dullin (; 8 May 1885 – 11 December 1949) was a French actor, theater manager and director.

Career

Dullin began his career as an actor in melodrama:185 In 1908, he started his first troupe with Saturnin Fabre, the ''Théâtre de Foir ...

, Firmin Gémier

Firmin Gémier (1869-1933) was a French actor and director. Internationally, he is most famous for originating the role of Père Ubu in Alfred Jarry’s play ''Ubu Roi''. He is known as the principle architect of the popular theatre movement in Fr ...

and Lugné Poe. Lugné Poe, who gave Artaud his first work in a professional theatre, would later describe Artaud as "a painter lost in the midst of actors". His core theatrical training was as part of Dullin's troupe, ''Théâtre de l'Atelier'', which he joined in 1921.:345 Artaud remained a member for eighteen months.:345

As a member of Dullin's troupe, Artaud trained for 10 to 12 hours a day. Originally Artaud was a strong proponent of Dullin's teaching, stating: "Hearing Dullin teach I feel that I'm rediscovering ancient secrets and a whole forgotten mystique of production.":351 In particular, they shared a strong interest in east Asian theater, specifically performance traditions from Bali and Japan.:10 Dullin, however, did not think Western theater should be adopting the language and style of east Asian theatre. Instead he promoted a theatre of transposition; for Dullin, "To want to impose on our Western theater rules of a theatre of a long tradition which has its own symbolic language would be a great mistake."

Artaud came to disagree with many of Dullin's teachings.:352 Their final disagreement was over his performance of the Emperor Charlemagne in Alexandre Arnoux's ''Huon de Bordeaux'' and he left the troupe in 1923.:22 He would join the Pitoëff's troupe in 1923, remaining with them through the next year when he would put more focus on his work in the cinema.:15-16

Literary career

In 1923, Artaud mailed some of his poems to the journal ''La Nouvelle Revue Française

LA most frequently refers to Los Angeles, the second largest city in the United States.

La, LA, or L.A. may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

* La (musical note), or A, the sixth note

* "L.A.", a song by Elliott Smith on ''Figur ...

'' (NRF); they were rejected, but the author of the poems intrigued the NRF's editor, Jacques Rivière

Jacques Rivière (15 July 1886 – 14 February 1925) was a French " man of letters" — a writer, critic and editor who was "a major force in the intellectual life of France in the period immediately following World War I". He edited the ...

, who requested a meeting. After meeting via post they continued their relationship. The compilation of these letters into an epistolary

Epistolary means "in the form of a letter or letters", and may refer to:

* Epistolary ( la, epistolarium), a Christian liturgical book containing set readings for church services from the New Testament Epistles

* Epistolary novel

* Epistolary poem ...

work, ''Correspondance avec Jacques Rivière'', was Artaud's first major publication.:45 Artaud would continue to publish some of his most important work in the ''NRF'', including the "First Manifesto for a Theatre of Cruelty

The Theatre of Cruelty (french: Théâtre de la Cruauté, also french: Théâtre cruel) is a form of theatre generally associated with Antonin Artaud. Artaud, who was briefly a member of the surrealist movement, outlined his theories in ''The Theat ...

" (1932) and "Theatre and the plague" (1933).:105 He would draw from these publications when putting together ''The Theatre and Its Double

''The Theatre and Its Double'' (''Le Théâtre et son Double'') is a collection of essays by French poet and playwright Antonin Artaud. It contains his most famous works on the theatre, including his manifestos for a Theatre of Cruelty.

Compos ...

''.:105

Work in the cinema

Artaud also had an active career in the cinema working as a critic, actor, and writer. Artaud's performance as

Artaud also had an active career in the cinema working as a critic, actor, and writer. Artaud's performance as Jean-Paul Marat

Jean-Paul Marat (; born Mara; 24 May 1743 – 13 July 1793) was a French political theorist, physician, and scientist. A journalist and politician during the French Revolution, he was a vigorous defender of the ''sans-culottes'', a radical ...

in Abel Gance

Abel Gance (; born Abel Eugène Alexandre Péréthon; 25 October 188910 November 1981) was a French film director and producer, writer and actor. A pioneer in the theory and practice of montage, he is best known for three major silent films: ''J ...

's ''Napoléon'' (1927) used exaggerated movements to convey the fire of Marat's personality. He also played the monk Massieu in Carl Theodor Dreyer

Carl Theodor Dreyer (; 3 February 1889 – 20 March 1968), commonly known as Carl Th. Dreyer, was a Danish film director and screenwriter. Widely considered one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, his movies are noted for their emotional aus ...

's ''The Passion of Joan of Arc

''The Passion of Joan of Arc'' (french: link=no, La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc) is a 1928 French silent historical film based on the actual record of the trial of Joan of Arc. The film was directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer and stars Renée Jeanne ...

'' (1928).:17 He wrote a number of film scenarios, ten of which have survived.:23 Only one of Artaud's scenarios was produced, '' The Seashell and the Clergyman'' (1928). Directed by Germaine Dulac

Germaine Dulac (; born Charlotte Elisabeth Germaine Saisset-Schneider; 17 November 1882 – 20 July 1942)Flitterman-Lewis 1996 was a French filmmaker, film theorist, journalist and critic. She was born in Amiens and moved to Paris in early child ...

, many critics and scholars consider it to be the first surrealist film.

Association with surrealists

Artaud was briefly associated with the surrealists, before being expelled byAndré Breton

André Robert Breton (; 19 February 1896 – 28 September 1966) was a French writer and poet, the co-founder, leader, and principal theorist of surrealism. His writings include the first ''Surrealist Manifesto'' (''Manifeste du surréalisme'') o ...

in 1927.:21 This was in part due to the Surrealists increasing affiliation with the Communist Party in France.:274 As Ros Murray notes, "Artaud was not into politics at all, writing things like: ''I shit on Marxism''. Additionally, "Breton was becoming very anti-theatre because he saw theatre as being bourgeois and anti-revolutionary." In "The Manifesto for an Abortive Theatre" (1926/27), written for the Theatre Alfred Jarry

The Theatre Alfred Jarry was founded in January 1926 by Antonin Artaud with Robert Aron and Roger Vitrac, in Paris, France. It was influenced by Surrealism and Theatre of the Absurd, and was foundational to Artaud's theory of the Theatre of Cru ...

, Artaud makes a direct attack on the surrealists, whom he calls "bog-paper revolutionaries" that would "make us believe that to produce theatre today is a counter-revolutionary endeavour".:24 He declares they are "bowing down to Communism",:25 which is "a lazy man's revolution",:24 and calls for a more "essential metamorphosis" of society.:25

Théâtre Alfred Jarry (1926–1929)

(For more details, including a full list of productions, see Théâtre Alfred Jarry) In 1926, Artaud, Robert Aron and the expelled surrealistRoger Vitrac Roger Vitrac (; 17 November 1899 – 22 January 1952) was a French surrealist playwright and poet.

Early life

Roger Vitrac was born in Pinsac on 17 November 1899, before his family moved to Paris in 1910.:527 As a young man, he was influenced b ...

founded the Théâtre Alfred Jarry (TAJ). They staged four productions between June 1927 and January 1929. The Theatre was extremely short-lived, but was attended by an enormous range of European artists, including Arthur Adamov

Arthur Adamov (23 August 1908 – 15 March 1970) was a playwright, one of the foremost exponents of the Theatre of the Absurd.

Early life

Adamov (originally Adamian) was born in Kislovodsk in the Terek Oblast of the Russian Empire to a wealthy A ...

, André Gide

André Paul Guillaume Gide (; 22 November 1869 – 19 February 1951) was a French author and winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature (in 1947). Gide's career ranged from its beginnings in the Symbolism (arts), symbolist movement, to the advent o ...

, and Paul Valéry

Ambroise Paul Toussaint Jules Valéry (; 30 October 1871 – 20 July 1945) was a French poet, essayist, and philosopher. In addition to his poetry and fiction (drama and dialogues), his interests included aphorisms on art, history, letters, mus ...

.:249

At the Paris Colonial Exposition (1931)

In 1931, Artaud sawBalinese dance

Balinese dance ( id, Tarian Bali; ban, ᬇᬕᬾᬮᬦ᭄ᬩᬮᬶ) is an ancient dance tradition that is part of the religious and artistic expression among the Balinese people of Bali island, Indonesia. Balinese dance is dynamic, angula ...

performed at the Paris Colonial Exposition

The Paris Colonial Exhibition (or "''Exposition coloniale internationale''", International Colonial Exhibition) was a six-month colonial exhibition held in Paris, France, in 1931 that attempted to display the diverse cultures and immense resour ...

. Although Artaud misunderstood much of what he saw, it influenced many of his ideas for theatre.:26 Adrian Curtin has noted the significance of the Balinese use of music and sound, stating that Artaud was struck by "the 'hypnotic' rhythms of the gamelan ensemble, its range of percussive effects, the variety of timbres that the musicians produced, and – most importantly, perhaps – the way in which the dancers' movements interacted dynamically with the musical elements instead of simply functioning as a type of background accompaniment."

The Cenci (1935)

In 1935, Artaud staged an original adaptation ofPercy Bysshe Shelley

Percy Bysshe Shelley ( ; 4 August 17928 July 1822) was one of the major English Romantic poets. A radical in his poetry as well as in his political and social views, Shelley did not achieve fame during his lifetime, but recognition of his achie ...

's ''The Cenci

''The Cenci, A Tragedy, in Five Acts'' (1819) is a verse drama in five acts by Percy Bysshe Shelley written in the summer of 1819, and inspired by a real Italian family, the House of Cenci (in particular, Beatrice Cenci, pronounced CHEN-chee). ...

'' at the Théâtre des Folies-Wagram

The Théâtre des Folies-Wagram was a theatre in Paris which operated from 1928 until 1964. From late 1935 it was known as the Théâtre de l'Étoile. Located at 35 Avenue de Wagram in the 17th arrondissement, the theatre saw the premieres of nume ...

in Paris.:250 The drama was Artaud's only chance to stage a Theatre of Cruelty production, and he emphasised its cruelty and violence, in particular "its themes of incest, revenge and familial murder".:21 In the play's stage directions, Artaud describes the opening scene as "suggestive of extreme atmospheric turbulence, with wind-blown drapes, waves of suddenly amplified sound, and crowds of figures engaged in "furious orgy", accompanied by "a chorus of church bells", as well as the presence of numerous large mannequins. Scholar Adrian Curtin has argued for the importance of the "sonic aspects of the production, which did not merely support the action but motivated it obliquely".:251 While Shelley's version of ''The Cenci'' conveyed the motivations and anguish of the Cenci's daughter Beatrice with her father through monologues, Artaud was much more concerned with conveying the menacing nature of the Cenci's presence and the reverberations of their incest relationship though physical discordance, as if an invisible "force-field" surrounded them.

Jane Goodall writes of ''The Cenci,'' The predominance of action over reflection accelerates the development of events...the monologues...are cut in favor of sudden, jarring transitions...so that a spasmodic effect is created. Extreme fluctuations in pace, pitch, and tone heighten sensory awareness intensify ... the here and now of performance.:119''The Cenci'' was a commercial failure, although it employed innovative sound effects—including the first theatrical use of the electronic instrument the

Ondes Martenot

The ondes Martenot ( ; , "Martenot waves") or ondes musicales ("musical waves") is an early electronic musical instrument. It is played with a keyboard or by moving a ring along a wire, creating "wavering" sounds similar to a theremin. A player ...

—and had a set designed by Balthus

Balthasar Klossowski de Rola (February 29, 1908 – February 18, 2001), known as Balthus, was a Polish-French modern artist. He is known for his erotically charged images of pubescent girls, but also for the refined, dreamlike quality of his image ...

.

Travels and institutionalization

Journey to Mexico

In 1935 Artaud decided to go to Mexico, where he was convinced there was "a sort of deep movement in favour of a return to civilisation before Cortez".:11 The Mexican Legation in Paris gave him a travel grant, and he left for Mexico in January 1936, "where he would arrive one month later".:29-30 In 1936 he met his first Mexican-Parisian friend, the painterFederico Cantú Federico (; ) is a given name and surname. It is a form of Frederick, most commonly found in Spanish, Portuguese and Italian.

People with the given name Federico

Artists

* Federico Ágreda, Venezuelan composer and DJ.

* Federico Aguilar Alcuaz, ...

, when Cantú gave lectures on the decadence of Western civilization. Artaud also studied and lived with the Tarahumaran people and participated in peyote

The peyote (; ''Lophophora williamsii'' ) is a small, spineless cactus which contains psychoactive alkaloids, particularly mescaline. ''Peyote'' is a Spanish word derived from the Nahuatl (), meaning "caterpillar cocoon", from a root , "to gl ...

rites, his writings about which were later released in a volume called ''Voyage to the Land of the Tarahumara'',:14 published in English under the title ''The Peyote Dance'' (1976). The content of this work closely resembles the poems of his later days, concerned primarily with the supernatural

Supernatural refers to phenomena or entities that are beyond the laws of nature. The term is derived from Medieval Latin , from Latin (above, beyond, or outside of) + (nature) Though the corollary term "nature", has had multiple meanings si ...

. Artaud also recorded his horrific withdrawal from heroin upon entering the land of the Tarahumaras. Having deserted his last supply of the drug at a mountainside, he literally had to be hoisted onto his horse and soon resembled, in his words, "a giant, inflamed gum". Artaud would return to opiates later in life.

Ireland and repatriation to France

In 1937, Artaud returned to France, where his friend René Thomas gave him a walking-stick of knotted wood that Artaud believed contained magical powers and was the 'most sacred relic of the Irish church, the '' Bachall Ísu'', or "Staff of Jesus".:32 Artaud traveled to Ireland, landing atCobh

Cobh ( ,), known from 1849 until 1920 as Queenstown, is a seaport town on the south coast of County Cork, Ireland. With a population of around 13,000 inhabitants, Cobh is on the south side of Great Island in Cork Harbour and home to Ireland's ...

and travelling to Galway

Galway ( ; ga, Gaillimh, ) is a City status in Ireland, city in the West Region, Ireland, West of Ireland, in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Connacht, which is the county town of County Galway. It lies on the River Corrib between Lo ...

, possibly in an effort to return the staff.:33 Speaking very little English and no Gaelic whatsoever, he was unable to make himself understood.:33 He would not have been admitted at Cobh, according to Irish government documents, except that he carried a letter of introduction from the Paris embassy. Most of his trip was spent in a hotel room he was unable to pay for. He was forcibly removed from the grounds of Milltown House, a Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

community, when he refused to leave. Before deportation he was briefly confined in the notorious Mountjoy Prison

Mountjoy Prison ( ga, Príosún Mhuinseo), founded as Mountjoy Gaol and nicknamed ''The Joy'', is a medium security men's prison located in Phibsborough in the centre of Dublin, Ireland.

The current prison Governor is Edward Mullins.

History

...

.:152 According to Irish Government papers he was deported as "a destitute and undesirable alien". On his return trip by ship, Artaud believed he was being attacked by two crew members, and he retaliated; he was put in a straitjacket

A straitjacket is a garment shaped like a jacket with long sleeves that surpass the tips of the wearer's fingers. Its most typical use is restraining people who may cause harm to themselves or others. Once the wearer slides their arms into the ...

and he was involuntarily retained by the police upon his return to France.:34

His return from Ireland brought about the beginning of the final phase of Artaud's life, which was spent in different asylums. It was at this time that his best known work ''The Theatre and Its Double'' (1938) was published.:34 This book contained the two manifestos of the Theatre of Cruelty

The Theatre of Cruelty (french: Théâtre de la Cruauté, also french: Théâtre cruel) is a form of theatre generally associated with Antonin Artaud. Artaud, who was briefly a member of the surrealist movement, outlined his theories in ''The Theat ...

. There, "he proposed a theatre that was in effect a return to magic and ritual and he sought to create a new theatrical language of totem and gesture – a language of space devoid of dialogue that would appeal to all the senses." "Words say little to the mind," Artaud wrote, "compared to space thundering with images and crammed with sounds." He proposed "a theatre in which violent physical images crush and hypnotize the sensibility of the spectator seized by the theatre as by a whirlwind of higher forces." He considered formal theatres with their proscenium arches and playwrights with their scripts "a hindrance to the magic of genuine ritual".:6

In Rodez

In 1943, when France was occupied by the Germans and Italians,Robert Desnos

Robert Desnos (; 4 July 1900 – 8 June 1945) was a French poet who played a key role in the Surrealist movement of his day.

Biography

Robert Desnos was born in Paris on 4 July 1900, the son of a licensed dealer in game and poultry at the '' H ...

arranged to have Artaud transferred to the psychiatric hospital

Psychiatric hospitals, also known as mental health hospitals, behavioral health hospitals, are hospitals or wards specializing in the treatment of severe mental disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, dissociative ...

in Rodez

Rodez ( or ; oc, Rodés, ) is a small city and commune in the South of France, about 150 km northeast of Toulouse. It is the prefecture of the department of Aveyron, region of Occitania (formerly Midi-Pyrénées). Rodez is the seat of the ...

, well inside Vichy

Vichy (, ; ; oc, Vichèi, link=no, ) is a city in the Allier Departments of France, department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of central France, in the historic province of Bourbonnais.

It is a Spa town, spa and resort town and in World ...

territory, where he was put under the charge of Dr. Gaston Ferdière. At Rodez Artaud underwent therapy including electroshock treatments and art therapy.:194 The doctor believed that Artaud's habits of crafting magic spells, creating astrology

Astrology is a range of Divination, divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of Celestial o ...

charts, and drawing disturbing images were symptoms of mental illness

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitti ...

. Artaud, at his peak began lashing out at others. Artaud denounced the electroshock treatments and consistently pleaded to have them suspended, while also ascribing to them "the benefit of having returned him to his name and to his self mastery".:196 Scholar Alexandra Lukes points out that "the 'recovery' of his name" might have been "a gesture to appease his doctors" conception of what constitutes health".:196 It was during this time that Artaud began writing and drawing again, after a long dormant period. In 1946, Ferdière released Artaud to his friends, who placed him in the psychiatric clinic at Ivry-sur-Seine

Ivry-sur-Seine () is a commune in the Val-de-Marne department in the southeastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the centre of Paris.

Paris's main Asian district, the Quartier Asiatique in the 13th arrondissement, borders the ...

.

Final years

At Ivry-sur-Seine Artaud's friends encouraged him to write and interest in his work was rekindled. He visited aVincent van Gogh

Vincent Willem van Gogh (; 30 March 185329 July 1890) was a Dutch Post-Impressionism, Post-Impressionist painter who posthumously became one of the most famous and influential figures in Western art history. In a decade, he created about 2 ...

exhibition at the Orangerie in Paris and wrote the study ''Van Gogh le suicidé de la société'' Van Gogh, The Man Suicided by Society" in 1947, the French magazine K published it.:8 In 1949, the essay would be first of Artaud's to be translated in a United States based publication, the influential literary magazine ''Tiger's Eye''.:8

'

He recorded '' (To Have Done With the Judgment of God)'' on 22–29 November 1947. The work remained true to his vision for the theatre of cruelty, using "screams, rants and vocal shudders" to forward his vision.:1 Wladimir Porché, the Director of French Radio, shelved the work the day before its scheduled airing on 2 February 1948. This was partly for itsscatological

In medicine and biology, scatology or coprology is the study of feces.

Scatological studies allow one to determine a wide range of biological information about a creature, including its diet (and thus where it has been), health and diseases s ...

, anti-American

Anti-Americanism (also called anti-American sentiment) is prejudice, fear, or hatred of the United States, its government, its foreign policy, or Americans in general.

Political scientist Brendon O'Connor at the United States Studies Centr ...

, and anti-religious references and pronouncements, but also because of its general randomness, with a cacophony of xylophonic sounds mixed with various percussion

A percussion instrument is a musical instrument that is sounded by being struck or scraped by a beater including attached or enclosed beaters or rattles struck, scraped or rubbed by hand or struck against another similar instrument. Exc ...

elements. While remaining true to his Theatre of Cruelty and reducing powerful emotions and expressions into audible sounds, Artaud had utilized various, somewhat alarming cries, screams, grunts, onomatopoeia

Onomatopoeia is the process of creating a word that phonetically imitates, resembles, or suggests the sound that it describes. Such a word itself is also called an onomatopoeia. Common onomatopoeias include animal noises such as ''oink'', ''m ...

, and glossolalia

Speaking in tongues, also known as glossolalia, is a practice in which people utter words or speech-like sounds, often thought by believers to be languages unknown to the speaker. One definition used by linguists is the fluid vocalizing of sp ...

.

As a result, Fernand Pouey, the director of dramatic and literary broadcasts for French radio, assembled a panel to consider the broadcast of ' Among approximately 50 artists, writers, musicians, and journalists present for a private listening on 5 February 1948 were Jean Cocteau

Jean Maurice Eugène Clément Cocteau (, , ; 5 July 1889 – 11 October 1963) was a French poet, playwright, novelist, designer, filmmaker, visual artist and critic. He was one of the foremost creatives of the su ...

, Paul Éluard

Paul Éluard (), born Eugène Émile Paul Grindel (; 14 December 1895 – 18 November 1952), was a French poet and one of the founders of the Surrealist movement.

In 1916, he chose the name Paul Éluard, a matronymic borrowed from his maternal ...

, Raymond Queneau

Raymond Queneau (; 21 February 1903 – 25 October 1976) was a French novelist, poet, critic, editor and co-founder and president of Oulipo ('' Ouvroir de littérature potentielle''), notable for his wit and cynical humour.

Biography

Queneau w ...

, Jean-Louis Barrault

Jean-Louis Bernard Barrault (; 8 September 1910 – 22 January 1994) was a French actor, director and mime artist who worked on both screen and stage.

Biography

Barrault was born in Le Vésinet in France in 1910. His father was 'a Burgundia ...

, René Clair

René Clair (11 November 1898 – 15 March 1981), born René-Lucien Chomette, was a French filmmaker and writer. He first established his reputation in the 1920s as a director of silent films in which comedy was often mingled with fantasy. He wen ...

, Jean Paulhan

Jean Paulhan (2 December 1884 – 9 October 1968) was a French writer, literary critic and publisher, director of the literary magazine ''Nouvelle Revue Française'' (NRF) from 1925 to 1940 and from 1946 to 1968. He was a member (Seat 6, 1963–68 ...

, Maurice Nadeau, Georges Auric

Georges Auric (; 15 February 1899 – 23 July 1983) was a French composer, born in Lodève, Hérault, France. He was considered one of ''Les Six'', a group of artists informally associated with Jean Cocteau and Erik Satie. Before he turned 20 he ...

, Claude Mauriac, and René Char. Porché refused to broadcast it even though the panel were almost unanimously in favor of Artaud's work. Pouey left his job and the show was not heard again until 23 February 1948, at a private performance at Théâtre Washington. The work's first public broadcast would not take place until 8 July 1964, when the Los Angeles-based public radio station KPFK played an illegal copy provided by the artist Jean-Jacques Lebel

Jean-Jacques Lebel (born in Paris on June 30, 1936) is a French artist. His father was also a poet, translator, poetry publisher, political activist, art collector, and art historian. Besides his heterogeneous artworks and poetry, Lebel is also k ...

.:1 The first French radio broadcast of ' occurred 20 years after its original production.

Death

In January 1948, Artaud was diagnosed withcolorectal cancer

Colorectal cancer (CRC), also known as bowel cancer, colon cancer, or rectal cancer, is the development of cancer from the colon or rectum (parts of the large intestine). Signs and symptoms may include blood in the stool, a change in bowel m ...

. He died shortly afterwards, on 4 March 1948 in a psychiatric clinic in Ivry-sur-Seine

Ivry-sur-Seine () is a commune in the Val-de-Marne department in the southeastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the centre of Paris.

Paris's main Asian district, the Quartier Asiatique in the 13th arrondissement, borders the ...

, a commune in the southeastern suburbs of Paris. He was found by the gardener of the estate seated alone at the foot of his bed holding a shoe, and it was suspected that he died from a lethal dose of the drug chloral hydrate

Chloral hydrate is a geminal diol with the formula . It is a colorless solid. It has limited use as a sedative and hypnotic pharmaceutical drug. It is also a useful laboratory chemical reagent and precursor. It is derived from chloral (trichl ...

, although it is unknown whether he was aware of its lethality.

Legacy and influence

Artaud has had a profound influence on theatre,avant-garde art

The avant-garde (; In 'advance guard' or 'vanguard', literally 'fore-guard') is a person or work that is experimental, radical, or unorthodox with respect to art, culture, or society.John Picchione, The New Avant-garde in Italy: Theoretical D ...

, literature, psychiatry and other disciplines.

Theatre and Performance

Artaud's has exerted a strong influence on the development of experimental theatre and performance art. His ideas helped inspire a movement away from the dominant role of language and rationalism in performance practice. Many of his works were not produced for the public until after his death. For instance, Spurt of Blood (1925) was not produced until 1964, whenPeter Brook

Peter Stephen Paul Brook (21 March 1925 – 2 July 2022) was an English theatre and film director. He worked first in England, from 1945 at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre, from 1947 at the Royal Opera House, and from 1962 for the Royal Shak ...

and Charles Marowitz staged it as part of their "Theatre of Cruelty" season at the Royal Shakespeare Company

The Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) is a major British theatre company, based in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England. The company employs over 1,000 staff and produces around 20 productions a year. The RSC plays regularly in London, St ...

. Artists such Karen Finley, Spalding Gray

Spalding Gray (June 5, 1941 – January 11, 2004) was an American actor, novelist, playwright, screenwriter and performance artist. He is best known for the autobiographical monologues that he wrote and performed for the theater in the 1980s and ...

, Liz LeCompte, Richard Foreman

Richard Foreman (born June 10, 1937 in New York City) is an American avant-garde playwright and the founder of the Ontological-Hysteric Theater.

Achievements and awards

Foreman has written, directed and designed over fifty of his own plays, b ...

, Charles Marowitz

Charles Marowitz (26 January 1934 – 2 May 2014) was an American critic, theatre director, and playwright, regular columnist on Swans Commentary. He collaborated with Peter Brook at the Royal Shakespeare Company, and later founded and direct ...

, Sam Shepard

Samuel Shepard Rogers III (November 5, 1943 – July 27, 2017) was an American actor, playwright, author, screenwriter, and director whose career spanned half a century. He won 10 Obie Awards for writing and directing, the most by any write ...

, Joseph Chaikin

Joseph Chaikin (September 16, 1935 – June 22, 2003) was an American theatre director, actor, playwright, and pedagogue.

Early life and education

The youngest of five children, Chaikin was born to a poor Jewish family living in the Borough Pa ...

, and more all named Artaud as one of their influences.

His influence can be seen in:

* Barrault's adaptation of Kafka's ''The Trial

''The Trial'' (german: Der Process, link=no, previously , and ) is a novel written by Franz Kafka in 1914 and 1915 and published posthumously on 26 April 1925. One of his best known works, it tells the story of Josef K., a man arrested and p ...

'' (1947).

* The Theatre of the Absurd

The Theatre of the Absurd (french: théâtre de l'absurde ) is a post–World War II designation for particular plays of absurdist fiction written by a number of primarily European playwrights in the late 1950s. It is also a term for the style of ...

, particularly the works of Jean Genet

Jean Genet (; – ) was a French novelist, playwright, poet, essayist, and political activist. In his early life he was a vagabond and petty criminal, but he later became a writer and playwright. His major works include the novels ''The Thief's ...

and Samuel Beckett

Samuel Barclay Beckett (; 13 April 1906 – 22 December 1989) was an Irish novelist, dramatist, short story writer, theatre director, poet, and literary translator. His literary and theatrical work features bleak, impersonal and tragicomic expe ...

.

* Peter Brook's production of ''Marat/Sade

''The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade'' (german: Die Verfolgung und Ermordung Jean Paul Marats dargestellt durch die Schauspielgrupp ...

'' in 1964, which was performed in New York and Paris, as well as London.

* The Living Theatre

The Living Theatre is an American theatre company founded in 1947 and based in New York City. It is the oldest experimental theatre group in the United States. For most of its history it was led by its founders, actress Judith Malina and painter/po ...

.

* In the winter of 1968, Williams College offered a dedicated intersession class in Artaudian theatre, resulting in a week-long "Festival of Cruelty," under the direction of Keith Fowler

Keith Franklin Fowler (born February 23, 1939) is an American actor, director, producer, and educator. He is a professor emeritus of drama and former head of directing in the Drama Department of the Claire Trevor School of the Arts of the Univer ...

. The Festival included productions of ''The Jet of Blood, All Writing is Pig Shit'', and several original ritualized performances, one based on the Texas Tower killings and another created as an ensemble catharsis called ''The Resurrection of Pig Man''.

* In Canada, playwright Gary Botting

Gary Norman Arthur Botting (born 19 July 1943) is a Canadian legal scholar and criminal defense lawyer as well as a poet, playwright, novelist, and critic of literature and religion, in particular Jehovah's Witnesses. The author of 40 published b ...

created a series of Artaudian "happenings" from ''The Aeolian Stringer'' to ''Zen Rock Festival'', and produced a dozen plays with an Artaudian theme, including ''Prometheus Re-Bound''.

* Charles Marowitz's play ''Artaud at Rodez'' is about the relationship between Artaud and Dr. Ferdière during Artaud's confinement at the psychiatric hospital in Rodez; the play was first performed in 1976 at the Teatro a Trastavere in Rome.

* The writer and actor Tim Dalgleish wrote and produced the play ''The Life and Theatre of Antonin Artaud'' (1999) for the English physical theatre company Bare Bones. The play told Artaud's story from his early years of aspiration when he wished to be part of the establishment, through to his final years as a suffering, iconoclastic outsider.

Philosophy

Artaud also had a significant influence on philosophers.:22Gilles Deleuze

Gilles Louis René Deleuze ( , ; 18 January 1925 – 4 November 1995) was a French philosopher who, from the early 1950s until his death in 1995, wrote on philosophy, literature, film, and fine art. His most popular works were the two volu ...

and Félix Guattari

Pierre-Félix Guattari ( , ; 30 April 1930 – 29 August 1992) was a French psychoanalyst, political philosopher, semiotician, social activist, and screenwriter. He co-founded schizoanalysis with Gilles Deleuze, and ecosophy with Arne Næss, ...

, borrowed Artaud's phrase "the body without organs" to describe their conception of the virtual dimension of the body and, ultimately, the basic substratum of reality in their ''Capitalism and Schizophrenia

''Capitalism and Schizophrenia'' (french: Capitalisme et Schizophrénie) is a two-volume theoretical work by the French authors Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, respectively a philosopher and a psychoanalyst. Its volumes are ''Anti-Oedipus'' ...

''. Philosopher Jacques Derrida

Jacques Derrida (; ; born Jackie Élie Derrida; See also . 15 July 1930 – 9 October 2004) was an Algerian-born French philosopher. He developed the philosophy of deconstruction, which he utilized in numerous texts, and which was developed t ...

provided one of the key philosophical treatments of Artaud's work through his concept of "''parole soufflée''". Feminist scholar Julia Kristeva also drew on Artaud for her theorisation of "subject in process".:22-3

Literature

PoetAllen Ginsberg

Irwin Allen Ginsberg (; June 3, 1926 – April 5, 1997) was an American poet and writer. As a student at Columbia University in the 1940s, he began friendships with William S. Burroughs and Jack Kerouac, forming the core of the Beat Gener ...

claimed Artaud's work, specifically "To Have Done with the Judgement of God", had a tremendous influence on his most famous poem "Howl

Howl most often refers to:

*Howling, an animal vocalization in many canine species

*Howl (poem), a 1956 poem by Allen Ginsberg

Howl may also refer to:

Film

* ''The Howl'', a 1970 Italian film

* ''Howl'' (2010 film), a 2010 American arthouse b ...

". The Latin American dramatic novel ''Yo-Yo Boing!

''Yo-Yo Boing!'' (1998) is a postmodern novel in English, Spanish, and Spanglish by Puerto Rican author Giannina Braschi. The cross-genre work is a structural hybrid of poetry, political philosophy, musical, manifesto, treatise, memoir, an ...

'' by Giannina Braschi

Giannina Braschi (born February 5, 1953) is a Puerto Rican poet, novelist, dramatist, and scholar. Her notable works include ''Empire of Dreams'' (1988), ''Yo-Yo Boing!'' (1998) ''and United States of Banana'' (2011).

Braschi writes cross-genr ...

includes a debate between artists and poets concerning the merits of Artaud's "multiple talents" in comparison to the singular talents of other French writers.

Music

The bandBauhaus

The Staatliches Bauhaus (), commonly known as the Bauhaus (), was a German art school operational from 1919 to 1933 that combined crafts and the fine arts.Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 4th edn., 200 ...

included a song about the playwright, called "Antonin Artaud", on their album ''Burning from the Inside

''Burning from the Inside'' is the fourth studio album by English gothic rock band Bauhaus (band), Bauhaus, released in 1983 by record label Beggars Banquet Records, Beggars Banquet.

Recording and production

During the recording of the album, ...

''. Influential Argentine

Argentines (mistakenly translated Argentineans in the past; in Spanish (masculine) or (feminine)) are people identified with the country of Argentina. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Argentines, s ...

hard rock band Pescado Rabioso

Pescado Rabioso (Rabid Fish) were an Argentinian rock band led by Argentine musician Luis Alberto Spinetta from 1971 to 1973. Initially a trio accompanied by drummer Black Amaya and bassist Osvaldo "Bocón" Frascino, they became a quartet with the ...

recorded an album titled ''Artaud

Antoine Marie Joseph Paul Artaud, better known as Antonin Artaud (; 4 September 1896 – 4 March 1948), was a French writer, poet, dramatist, visual artist, essayist, actor and theatre director. He is widely recognized as a major figure of the E ...

''. Their leader Luis Alberto Spinetta

Luis Alberto Spinetta (23 January 1950 – 8 February 2012), nicknamed "El Flaco" (Spanish for "skinny"), was an Argentine singer, guitarist, composer and poet. One of the most influential Rock music, rock musicians of Argentina, he is regarded ...

wrote the lyrics partly basing them on Artaud's writings. Composer John Zorn

John Zorn (born September 2, 1953) is an American composer, conductor, saxophonist, arranger and producer who "deliberately resists category". Zorn's avant-garde and experimental approaches to composition and improvisation are inclusive of jaz ...

has written many works inspired by and dedicated to Artaud, including seven CDs: "Astronome

''Astronome'' is an album by American musician John Zorn featuring the "Moonchild Trio" of Joey Baron, Mike Patton and Trevor Dunn. It is the second album by the trio, following '' Moonchild: Songs Without Words''.

Theater director Richard Forem ...

", " Moonchild: Songs Without Words", "Six Litanies for Heliogabalus

''Six Litanies for Heliogabalus'' is an album by John Zorn. It is the third album to feature the "Moonchild Trio" of Mike Patton, Joey Baron and Trevor Dunn, following '' Moonchild: Songs Without Words'' (2005) and ''Astronome'' (2006) and the ...

", "The Crucible

''The Crucible'' is a 1953 play by American playwright Arthur Miller. It is a dramatized and partially fictionalized story of the Salem witch trials that took place in the Massachusetts Bay Colony during 1692–93. Miller wrote the play as a ...

", "Ipsissimus

''Ipsissimus'' is an album by John Zorn. It is the fifth album to feature the "Moonchild Trio" of Mike Patton, Joey Baron and Trevor Dunn, following '' Astronome'' (2006), '' Moonchild: Songs Without Words'' (2006), '' Six Litanies for Heliog ...

", " Templars: In Sacred Blood" and "The Last Judgment", a monodrama for voice and orchestra inspired by Artaud's late drawings "La Machine de l'être" (2000), "Le Momo" (1999) for violin and piano, and "Suppots et Suppliciations" (2012) for full orchestra.

Film

Filmmaker E. Elias Merhige, during an interview by writer Scott Nicolay, cited Artaud as a key influence for the experimental film '' Begotten''.Filmography

Bibliography

Selected works

French

English translation

Critical and biographic works

In English

Books *Barber, Stephen. ''Antonin Artaud: Blows and Bombs'' (Faber and Faber: London, 1993) *Bradnock, Lucy. ''No More Masterpieces: Modern Art After Artaud'' (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021). * Deleuze, Gilles andFélix Guattari

Pierre-Félix Guattari ( , ; 30 April 1930 – 29 August 1992) was a French psychoanalyst, political philosopher, semiotician, social activist, and screenwriter. He co-founded schizoanalysis with Gilles Deleuze, and ecosophy with Arne Næss, ...

. ''Anti-Oedipus

''Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia'' (french: Capitalisme et schizophrénie. L'anti-Œdipe) is a 1972 book by French authors Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, the former a philosopher and the latter a psychoanalyst. It is the first vol ...

: Capitalism and Schizophrenia

''Capitalism and Schizophrenia'' (french: Capitalisme et Schizophrénie) is a two-volume theoretical work by the French authors Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, respectively a philosopher and a psychoanalyst. Its volumes are ''Anti-Oedipus'' ...

''. Trans. R. Hurley, H. Seem, and M. Lane. (New York: Viking Penguin, 1977).

*Esslin, Martin. ''Antonin Artaud''. London: John Calder, 1976.

*Greene, Naomi. ''Antonin Artaud: Poet Without Words''. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1971).

*Goodall, Jane. ''Artaud and the Gnostic Drama.'' Oxford: Clarendon Press; Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

*Jamieson, Lee. ''Antonin Artaud: From Theory to Practice'' (Greenwich Exchange: London, 2007) .

*Jannarone, Kimberly. ''Artaud and His Doubles'' (Ann Arbor, MI, University of Michigan Press, 2010).

*Knapp, Bettina. ''Antonin Artaud: Man of Vision''. (Athens, OH: Swallow Press, 1980).

*Morris, Blake. ''Antonin Artaud'' (London: Routledge, 2022).

*Plunka, Gene A. (ed). ''Antonin Artaud and the Modern Theater''. (Cranbury: Associated University Presses. 1994).

*Rose, Mark. ''The Actor and His Double: Mime and Movement for the Theatre of Cruelty''. (Actor Training Research Institute, 1986).

*Shafer, David. ''Antonin Artaud''. (London: Reaktion Books, 2016)

Articles and chapters

* Bataille, George. "Surrealism Day to Day". In ''The Absence of Myth: Writings on Surrealism''. Trans. Michael Richardson. London: Verso, 1994. 34–47.

* Bersani, Leo. "Artaud, Defecation, and Birth". In ''A Future for Astyanax: Character and Desire in Literature''. Boston: Little, Brown, 1976.

* Blanchot, Maurice. "Cruel Poetic Reason (the rapacious need for flight)". In ''The Infinite Conversation''. Trans. Susan Hanson. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993. 293–297.

* Deleuze, Gilles. "Thirteenth Series of the Schizophrenic and the Little Girl". In ''The Logic of Sense''. Trans. Mark Lester with Charles Stivale. Ed. Constantin V. Boundas. New York: Columbia University Press, 1990. 82–93.

* Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari

Pierre-Félix Guattari ( , ; 30 April 1930 – 29 August 1992) was a French psychoanalyst, political philosopher, semiotician, social activist, and screenwriter. He co-founded schizoanalysis with Gilles Deleuze, and ecosophy with Arne Næss, ...

. "28 November 1947: How Do You Make Yourself a Body Without Organs?". In ''A Thousand Plateaus

''A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia'' (french: link=no, Mille plateaux) is a 1980 book by the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze and the French psychoanalyst Félix Guattari. It is the second and final volume of their collaborativ ...

: Capitalism and Schizophrenia''. Trans. Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987. 149–166.

*Derrida, Jacques

Jacques Derrida (; ; born Jackie Élie Derrida; See also . 15 July 1930 – 9 October 2004) was an Algerian-born French philosopher. He developed the philosophy of deconstruction, which he utilized in numerous texts, and which was developed t ...

. "The Theatre of Cruelty" and "La Parole Souffle". In ''Writing and Difference''. Trans. Alan Bass. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978.

*Ferdière, Gaston. "I Looked after Antonin Artaud". In ''Artaud at Rodez''. Marowitz, Charles (1977). pp. 103–112. London: Marion Boyars. .

*Innes, Christopher. "Antonin Artaud and the Theatre of Cruelty". In ''Avant-Garde Theatre 1892–1992'' (London: Routledge, 1993).

*Jannarone, Kimberly. "The Theater Before Its Double: Artaud Directs in the Alfred Jarry Theater", ''Theatre Survey'' 46.2 (November 2005), 247–273.

*Koch, Stephen. "On Artaud." ''Tri-Quarterly'', no. 6 (Spring 1966): 29–37.

*Pireddu, Nicoletta. "The mark and the mask: psychosis in Artaud's alphabet of cruelty," ''Arachnē: An International Journal of Language and Literature'' 3 (1), 1996: 43–65.

*Rainer, Friedrich. "The Deconstructed Self in Artaud and Brecht: Negation of Subject and Antitotalitarianism", ''Forum for Modern Language Studies'', 26:3 (July 1990): 282–297.

* Shattuck, Roger. "Artaud Possessed". In ''The Innocent Eye''. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1984. 169–186.

* Sontag, Susan. "Approaching Artaud". In ''Under the Sign of Saturn''. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1980. 13–72. lso printed as Introduction to ''Antonin Artaud: Selected Writings'', ed. Sontag.*Ward, Nigel "Fifty-one Shocks of Artaud", ''New Theatre Quarterly'' Vol. XV, Part 2 (NTQ58 May 1999): 123–128

In French

*Blanchot, Maurice. "Artaud" (November 1956, no. 47): 873–881. *Brau, Jean-Louis. ''Antonin Artaud''. Paris: La Table Ronde, 1971. *, 1969 * Florence de Mèredieu, ''Antonin Artaud, Portraits et Gris-gris'', Paris: Blusson, 1984, new edition with additions, 2008. * Florence de Mèredieu, ''Antonin Artaud, Voyages'', Paris: Blusson, 1992. * Florence de Mèredieu, ''Antonin Artaud, de l'ange'', Paris: Blusson, 1992. * Florence de Mèredieu, ''Sur l'électrochoc, le cas Antonin Artaud'', Paris: Blusson, 1996. * Florence de Mèredieu, ''C'était Antonin Artaud'', biography, Fayard, 2006. * Florence de Mèredieu, ''La Chine d'Antonin Artaud / Le Japon d'Antonin Artaud'', Paris: Blusson, 2006. * Florence de Mèredieu, ''L'Affaire Artaud'', journal ethnographique, Paris: Fayard, 2009. * Florence de Mèredieu, ''Antonin Artaud dans la guerre, de Verdun à Hitler. L'hygiène mentale'', Paris: Blusson, 2013. * Florence de Mèredieu, ''Vincent van Gogh, Antonin Artaud. Ciné-roman. Ciné-peinture'', Paris: Blusson, 2014. * Florence de Mèredieu, ''BACON, ARTAUD, VINCI. Une blessure magnifique'', Paris: Blusson, 2019. *Virmaux, Alain. ''Antonin Artaud et le théâtre''. Paris: Seghers, 1970. *Virmaux, Alain and Odette. ''Artaud: un bilan critique''. Paris: Belfond, 1979. *Virmaux, Alain and Odette. ''Antonin Artaud: qui êtes-vous?'' Lyon: La Manufacture, 1986.In German

*Seegers, U. ''Alchemie des Sehens. Hermetische Kunst im 20. Jahrhundert. Antonin Artaud, Yves Klein, Sigmar Polke'' (Köln: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2003).References

External links

* * * an anachronistic film account of Artaud's life. {{DEFAULTSORT:Artaud, Antonin 1896 births 1948 deaths 20th-century French dramatists and playwrights 20th-century French male actors 20th-century French poets 20th-century male writers Deaths from cancer in France Deaths from colorectal cancer French acting theorists French artists French male film actors French male poets French male silent film actors French male stage actors French military personnel of World War I French people of Greek descent French surrealist writers Male actors from Marseille Modern artists Modernist theatre People with schizophrenia Poètes maudits Prix Sainte-Beuve winners Surrealist dramatists and playwrights Surrealist poets Theatre practitioners Writers from Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur