Arnold Bennett (politician) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

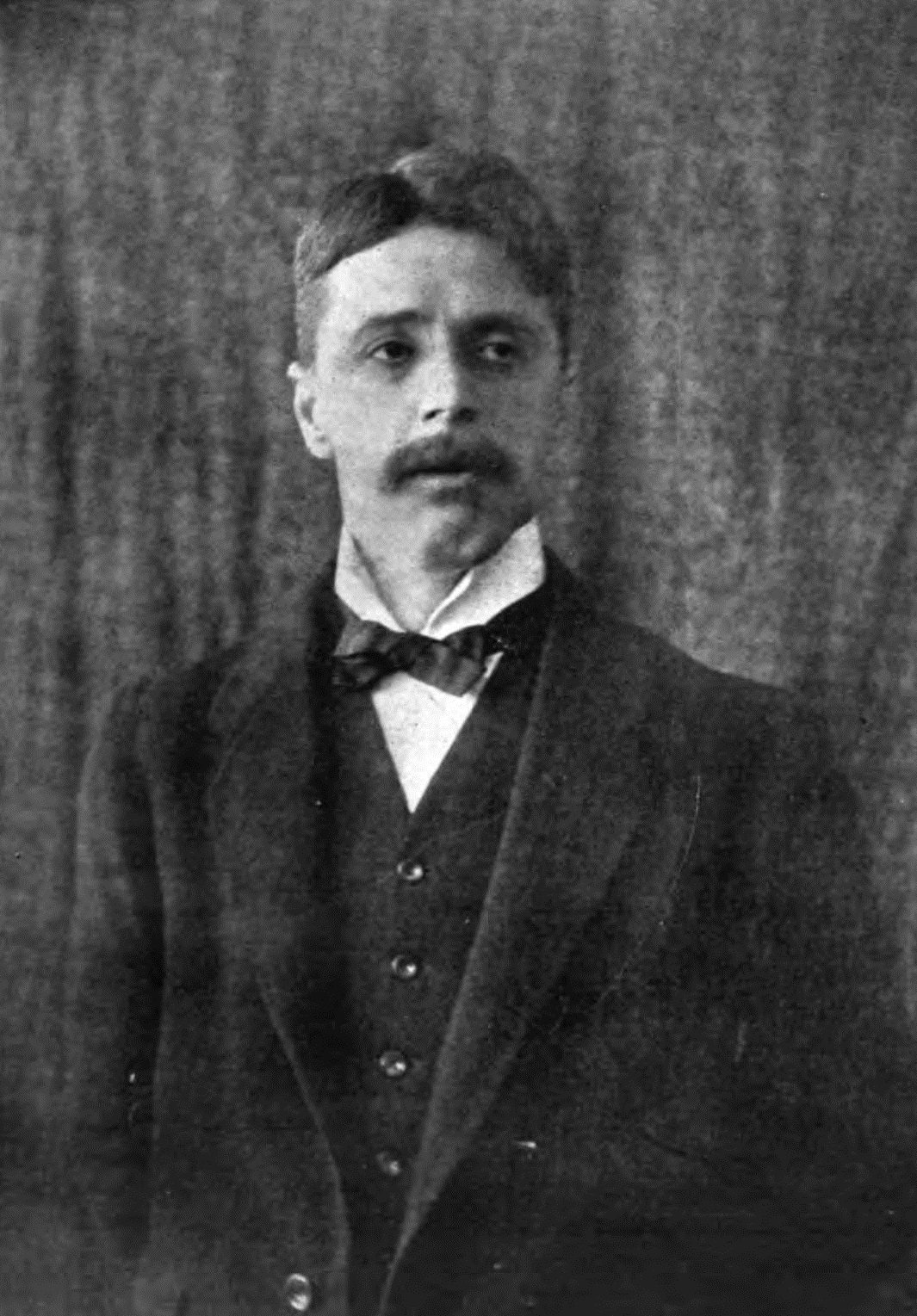

Enoch Arnold Bennett (27 May 1867 – 27 March 1931) was an English author, best known as a novelist who wrote prolifically. Between the 1890s and the 1930s he completed 34 novels, seven volumes of short stories, 13 plays (some in collaboration with other writers), and a daily journal totalling more than a million words. He wrote articles and stories for more than 100 newspapers and periodicals, worked in and briefly ran the Ministry of Information in the

"Stoke‐on‐Trent"

, ''The Oxford Guide to Literary Britain and Ireland'', Oxford University Press, 2008. Retrieved 30 May 2020 . He was the eldest child of the three sons and three daughters of Enoch Bennett (1843–1902) and his wife Sarah Ann, ''née'' Longson (1840–1914). Enoch Bennett's early career had been one of mixed fortunes: after an unsuccessful attempt to run a business making and selling pottery, he set up as a draper and pawnbroker in 1866. Four years later Enoch's father died, leaving him some money with which he

"Bennett, (Enoch) Arnold (1867–1931), writer"

, ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004. Retrieved 30 May 2020 The Bennetts were staunch Wesleyans, musical, cultured and sociable. Enoch Bennett had an authoritarian side, but it was a happy household, although a mobile one: as Enoch's success as a solicitor increased, the family moved, within the space of five years in the late 1870s and early 1880s, to four different houses in Hanley and the neighbouring Burslem. From 1877 to 1882, Bennett's schooling was at the Wedgwood Institute, Burslem, followed by a year at a

In the solicitors' office in London, Bennett became friendly with a young colleague, John Eland, who had a passion for books. Eland's friendship helped alleviate Bennett's innate shyness, which was exacerbated by a lifelong stammer. Together they explored the world of literature. Among the writers who impressed and influenced Bennett were George Moore,

In the solicitors' office in London, Bennett became friendly with a young colleague, John Eland, who had a passion for books. Eland's friendship helped alleviate Bennett's innate shyness, which was exacerbated by a lifelong stammer. Together they explored the world of literature. Among the writers who impressed and influenced Bennett were George Moore,

"Bennett, Arnold"

''The Oxford Companion to English Literature'', Oxford University Press, 2009

In 1905 Bennett became engaged to Eleanor Green, a member of an eccentric and capricious American family living in Paris, but at the last moment, after the wedding invitations had been sent out, she broke off the engagement and almost immediately married a fellow American. Drabble comments that Bennett was well rid of her, but it was a painful episode in his life. In early 1907 he met Marguerite Soulié (1874–1960), who soon became first a friend and then a lover. In May he was taken ill with a severe gastric complaint, and Marguerite moved into his flat to look after him. They became still closer, and in July 1907, shortly after his fortieth birthday, they were married at the

In 1905 Bennett became engaged to Eleanor Green, a member of an eccentric and capricious American family living in Paris, but at the last moment, after the wedding invitations had been sent out, she broke off the engagement and almost immediately married a fellow American. Drabble comments that Bennett was well rid of her, but it was a painful episode in his life. In early 1907 he met Marguerite Soulié (1874–1960), who soon became first a friend and then a lover. In May he was taken ill with a severe gastric complaint, and Marguerite moved into his flat to look after him. They became still closer, and in July 1907, shortly after his fortieth birthday, they were married at the

"Bennett, (Enoch) Arnold (1867–1931)"

, ''Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 1949. Retrieved 1 June 2020 Early in 1908 the couple moved from the rue d'Aumale to the Villa des Néfliers in Fontainebleau-Avon, about 40 miles (64 km) south-east of Paris. Lucas comments that the best of the novels written while in France – ''Whom God Hath Joined'' (1906), ''The Old Wives' Tale'' (1908), and ''

In 1921 Bennett and his wife

In 1921 Bennett and his wife

"Bennett, Arnold"

, ''The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature'', Oxford University Press, 2006. Retrieved 4 June 2020 From the start of his career, Bennett was aware of the appeal of regional fiction.

Bennett is remembered chiefly for his novels and short stories. The best known are set in, or feature people from, the six towns of the Potteries of his youth. He presented the region as "the Five Towns", which correspond closely with their originals: the real-life Burslem,

Bennett is remembered chiefly for his novels and short stories. The best known are set in, or feature people from, the six towns of the Potteries of his youth. He presented the region as "the Five Towns", which correspond closely with their originals: the real-life Burslem,

The literary

The literary

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, and wrote for the cinema in the 1920s. Sales of his books were substantial and he was the most financially successful British author of his day.

Born into a modest but upwardly mobile family in Hanley

Hanley is one of the six towns that, along with Burslem, Longton, Fenton, Tunstall and Stoke-upon-Trent, amalgamated to form the City of Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire, England.

Hanley is the ''de facto'' city centre, having long been the ...

, in the Staffordshire Potteries, Bennett was intended by his father, a solicitor

A solicitor is a legal practitioner who traditionally deals with most of the legal matters in some jurisdictions. A person must have legally-defined qualifications, which vary from one jurisdiction to another, to be described as a solicitor and ...

, to follow him into the legal profession. Bennett worked for his father, before moving to another law firm in London as a clerk, aged 21. He became assistant editor and then editor of a women's magazine, before becoming a full-time author in 1900. Always a devotee of French culture in general and French literature in particular, he moved to Paris in 1903; there the relaxed milieu helped him overcome his intense shyness, particularly with women. He spent ten years in France, marrying a Frenchwoman in 1907. In 1912 he moved back to England. He and his wife separated in 1921 and he spent the last years of his life with a new partner, an English actress. He died in 1931 of typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

, having unwisely drunk tap-water in France.

Many of Bennett's novels and short stories are set in a fictionalised version of the Staffordshire Potteries, which he called The Five Towns. He strongly believed that literature should be accessible to ordinary people, and he deplored literary cliques and élites. His books appealed to a wide public and sold in large numbers. For this reason, and for his adherence to realism, writers and supporters of the modernist school, notably Virginia Woolf

Adeline Virginia Woolf (; ; 25 January 1882 28 March 1941) was an English writer, considered one of the most important modernist 20th-century authors and a pioneer in the use of stream of consciousness as a narrative device.

Woolf was born i ...

, belittled him, and his fiction became neglected after his death. During his lifetime his journalistic "self-help" books sold in substantial numbers, and he was also a playwright; he did less well in the theatre than with novels, but achieved two considerable successes with ''Milestones

A milestone is a marker of distance along roads.

Milestone may also refer to:

Measurements

*Milestone (project management), metaphorically, markers of reaching an identifiable stage in any task or the project

*Software release life cycle state, s ...

'' (1912) and '' The Great Adventure'' (1913).

Studies by Margaret Drabble

Dame Margaret Drabble, Lady Holroyd, (born 5 June 1939) is an English biographer, novelist and short story writer.

Drabble's books include '' The Millstone'' (1965), which won the following year's John Llewellyn Rhys Memorial Prize, and ''Jer ...

(1974), John Carey (1992) and others have led to a re-evaluation of Bennett's work. His finest novels, including ''Anna of the Five Towns

''Anna of the Five Towns'' is a novel by Arnold Bennett, first published in 1902 and one of his best-known works.

Plot background

The plot centres on Anna Tellwright, daughter of a wealthy but miserly and dictatorial father, living in the P ...

'' (1902), ''The Old Wives' Tale

''The Old Wives' Tale'' is a novel by Arnold Bennett, first published in 1908. It deals with the lives of two very different sisters, Constance and Sophia Baines, following their stories from their youth, working in their mother's draper's sho ...

'' (1908), ''Clayhanger

The ''Clayhanger'' Family is a series of novels by Arnold Bennett, published between 1910 and 1918. Though the series is commonly referred to as a "trilogy", and the first three novels were published in a single volume, as ''The Clayhanger Famil ...

'' (1910) and ''Riceyman Steps

''Riceyman Steps'' is a novel by British novelist Arnold Bennett, first published in 1923 and winner of that year's James Tait Black Memorial Prize for fiction. It follows a year in the life of Henry Earlforward, a miserly second-hand bookshop ow ...

'' (1923), are now widely recognised as major works.

Life and career

Early years

Arnold Bennett was born on 27 May 1867 in Hanley, Staffordshire, now part ofStoke-on-Trent

Stoke-on-Trent (often abbreviated to Stoke) is a city and Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area in Staffordshire, England, with an area of . In 2019, the city had an estimated population of 256,375. It is the largest settlement ...

but then a separate town.Hahn, Daniel, and Nicholas Robins"Stoke‐on‐Trent"

, ''The Oxford Guide to Literary Britain and Ireland'', Oxford University Press, 2008. Retrieved 30 May 2020 . He was the eldest child of the three sons and three daughters of Enoch Bennett (1843–1902) and his wife Sarah Ann, ''née'' Longson (1840–1914). Enoch Bennett's early career had been one of mixed fortunes: after an unsuccessful attempt to run a business making and selling pottery, he set up as a draper and pawnbroker in 1866. Four years later Enoch's father died, leaving him some money with which he

articled

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

himself to a local law firm; in 1876 he qualified as a solicitor

A solicitor is a legal practitioner who traditionally deals with most of the legal matters in some jurisdictions. A person must have legally-defined qualifications, which vary from one jurisdiction to another, to be described as a solicitor and ...

.Lucas, John"Bennett, (Enoch) Arnold (1867–1931), writer"

, ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004. Retrieved 30 May 2020 The Bennetts were staunch Wesleyans, musical, cultured and sociable. Enoch Bennett had an authoritarian side, but it was a happy household, although a mobile one: as Enoch's success as a solicitor increased, the family moved, within the space of five years in the late 1870s and early 1880s, to four different houses in Hanley and the neighbouring Burslem. From 1877 to 1882, Bennett's schooling was at the Wedgwood Institute, Burslem, followed by a year at a

grammar school

A grammar school is one of several different types of school in the history of education in the United Kingdom and other English-speaking countries, originally a school teaching Latin, but more recently an academically oriented secondary school ...

in Newcastle-under-Lyme

Newcastle-under-Lyme ( RP: , ) is a market town and the administrative centre of the Borough of Newcastle-under-Lyme in Staffordshire, England. The 2011 census population of the town was 75,082, whilst the wider borough had a population of 1 ...

. He was good at Latin and better at French; he had an inspirational headmaster who gave him a love for French literature and the French language that lasted all his life. He did well academically and passed Cambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

examinations that could have led to an Oxbridge

Oxbridge is a portmanteau of Oxford and Cambridge, the two oldest, wealthiest, and most famous universities in the United Kingdom. The term is used to refer to them collectively, in contrast to other British universities, and more broadly to de ...

education, but his father had other plans. In 1883, aged 16, Bennett left school and began work – unpaid – in his father's office. He divided his time between uncongenial jobs, such as rent collecting, during the day, and studying for examinations in the evening. He began writing in a modest way, contributing light pieces to the local newspaper. He became adept in Pitman's shorthand, a skill much sought after in commercial offices, and on the strength of that he secured a post as a clerk at a firm of solicitors in Lincoln's Inn Fields

Lincoln's Inn Fields is the largest public square in London. It was laid out in the 1630s under the initiative of the speculative builder and contractor William Newton, "the first in a long series of entrepreneurs who took a hand in develo ...

, London. In March 1889, aged 21, he left for London and never returned to live in his native county.

First years in London

In the solicitors' office in London, Bennett became friendly with a young colleague, John Eland, who had a passion for books. Eland's friendship helped alleviate Bennett's innate shyness, which was exacerbated by a lifelong stammer. Together they explored the world of literature. Among the writers who impressed and influenced Bennett were George Moore,

In the solicitors' office in London, Bennett became friendly with a young colleague, John Eland, who had a passion for books. Eland's friendship helped alleviate Bennett's innate shyness, which was exacerbated by a lifelong stammer. Together they explored the world of literature. Among the writers who impressed and influenced Bennett were George Moore, Émile Zola

Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola (, also , ; 2 April 184029 September 1902) was a French novelist, journalist, playwright, the best-known practitioner of the literary school of naturalism, and an important contributor to the development of ...

, Honoré de Balzac, Guy de Maupassant

Henri René Albert Guy de Maupassant (, ; ; 5 August 1850 – 6 July 1893) was a 19th-century French author, remembered as a master of the short story form, as well as a representative of the Naturalist school, who depicted human lives, destin ...

, Gustave Flaubert

Gustave Flaubert ( , , ; 12 December 1821 – 8 May 1880) was a French novelist. Highly influential, he has been considered the leading exponent of literary realism in his country. According to the literary theorist Kornelije Kvas, "in Flauber ...

and Ivan Turgenev. He continued his own writing, and won a prize of twenty guineas from '' Tit-Bits'' in 1893 for his story 'The Artist's Model'; another short story, 'A Letter Home', was submitted successfully to ''The Yellow Book

''The Yellow Book'' was a British quarterly literary periodical that was published in London from 1894 to 1897. It was published at The Bodley Head Publishing House by Elkin Mathews and John Lane, and later by John Lane alone, and edited by th ...

'', where it featured in 1895 alongside contributions from Henry James

Henry James ( – ) was an American-British author. He is regarded as a key transitional figure between literary realism and literary modernism, and is considered by many to be among the greatest novelists in the English language. He was the ...

and other well-known writers.

In 1894 Bennett resigned from the law firm and became assistant editor of the magazine ''Woman''. The salary, £150 a year, was £50 less than he was earning as a clerk, but the post left him much more free time to write his first novel. For the magazine he wrote under a range of female pen-names such as "Barbara" and "Cecile". As his biographer Margaret Drabble

Dame Margaret Drabble, Lady Holroyd, (born 5 June 1939) is an English biographer, novelist and short story writer.

Drabble's books include '' The Millstone'' (1965), which won the following year's John Llewellyn Rhys Memorial Prize, and ''Jer ...

puts it:

The informal office life of the magazine suited Bennett, not least because it brought him into lively female company, and he began to be a little more relaxed with young women. He continued work on his novel and wrote short stories and articles. He was modest about his literary talent: he wrote to a friend, "I have no inward assurance that I could ever do anything more than mediocre viewed strictly as art – very mediocre", but he knew he could "turn out things which would be read with zest, & about which the man in the street would say to friends 'Have you read so & so in the ''What-is-it''?" He was happy to write for popular journals like ''Hearth and Home'' or for the highbrow '' The Academy''.

His debut novel, ''A Man from the North'', completed in 1896, was published two years later, by John Lane, whose reader, John Buchan

John Buchan, 1st Baron Tweedsmuir (; 26 August 1875 – 11 February 1940) was a Scottish novelist, historian, and Unionist politician who served as Governor General of Canada, the 15th since Canadian Confederation.

After a brief legal career ...

, recommended it for publication. It elicited a letter of praise from Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Poles in the United Kingdom#19th century, Polish-British novelist and short story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in t ...

and was well and widely reviewed, but Bennett's profits from the sale of the book were less than the cost of having it typed.

In 1896 Bennett was promoted to be editor of ''Woman''; by then he had set his sights on a career as a full-time author, but he served as editor for four years. During that time he wrote two popular books, described by the critic John Lucas as " pot-boilers": ''Journalism for Women'' (1898) and ''Polite Farces for the Drawing Room'' (1899). He also began work on a second novel, ''Anna of the Five Towns

''Anna of the Five Towns'' is a novel by Arnold Bennett, first published in 1902 and one of his best-known works.

Plot background

The plot centres on Anna Tellwright, daughter of a wealthy but miserly and dictatorial father, living in the P ...

'', the five towns being Bennett's lightly fictionalised version of the Staffordshire Potteries, where he grew up.Birch, Dinah (ed)."Bennett, Arnold"

''The Oxford Companion to English Literature'', Oxford University Press, 2009

Freelance; Paris

In 1900 Bennett resigned his post at ''Woman'', and left London to set up house at Trinity Hall Farm, near the village ofHockliffe

Hockliffe is a village and civil parish in Bedfordshire on the crossroads of the A5 road which lies upon the course of the Roman road known as Watling Street and the A4012 and B5704 roads.

It is about four miles east of Leighton Buzzard. Near ...

in Bedfordshire, where he made a home not only for himself but for his parents and younger sister. He completed ''Anna of the Five Towns'' in 1901; it was published the following year, as was its successor, ''The Grand Babylon Hotel

''The Grand Babylon Hotel'' is a novel by Arnold Bennett, published in January 1902, about the mysterious disappearance of a German prince. It originally appeared as a serial in the ''Golden Penny''. The titular Grand Babylon was modelled on the ...

''. The latter, an extravagant story of crime in high society, sold 50,000 copies in hardback and was almost immediately translated into four languages. By this stage he was confident enough in his abilities to tell a friend:

In January 1902 Enoch Bennett died, after a decline into dementia. His widow chose to move back to Burslem, and Bennett's sister married shortly afterwards. With no dependants, Bennett − always a devotee of French culture − decided to move to Paris; he took up residence there in March 1903.Pound, p. 127 Biographers have speculated on his precise reasons for doing so. Drabble suggests that perhaps "he was hoping for some kind of liberation. He was thirty-five and unmarried"; Lucas writes that it was almost certainly Bennett's desire to be recognised as a serious artist that prompted his move; according to his friend and colleague Frank Swinnerton

Frank Arthur Swinnerton (12 August 1884 – 6 November 1982) was an English novelist, critic, biographer and essayist.

He was the author of more than 50 books, and as a publisher's editor helped other writers including Aldous Huxley and Lytton S ...

, Bennett was following in the footsteps of George Moore by going to live in "the home of modern realism";Swinnerton (1950), p. 14 in the view of the biographer Reginald Pound

Reginald Pound (11 November 1894 – 20 May 1991) was an English journalist and biographer. He began contributing to newspapers and magazines during the First World War, while serving in the army. After the war he freelanced - his clients includ ...

it was "to begin his career as a man of the world". The 9th arrondissement of Paris was Bennett's home for the next five years, first in the rue de Calais, near the Place Pigalle, and then the more upmarket rue d'Aumale.

Life in Paris evidently helped Bennett overcome much of his remaining shyness with women. His journals for his early months in Paris mention a young woman identified as "C" or "Chichi", who was a chorus girl; the journals – or at least the cautiously selected extracts published since his death – do not record the precise nature of the relationship, but the two spent a considerable amount of time together.

In a restaurant where he dined frequently a trivial incident in 1903 gave Bennett the germ of an idea for the novel generally regarded as his masterpiece. A grotesque old woman came in and caused a fuss; the beautiful young waitress laughed at her, and Bennett was struck by the thought that the old woman had once been as young and lovely as the waitress. From this grew the story of two contrasting sisters in ''The Old Wives' Tale

''The Old Wives' Tale'' is a novel by Arnold Bennett, first published in 1908. It deals with the lives of two very different sisters, Constance and Sophia Baines, following their stories from their youth, working in their mother's draper's sho ...

''. He did not begin work on that novel until 1907, before which he wrote ten others, some "sadly undistinguished", in the view of his biographer Kenneth Young. Throughout his career, Bennett interspersed his best novels with some that his biographers and others have labelled pot-boilers.

Marriage; Fontainebleau and US visit

In 1905 Bennett became engaged to Eleanor Green, a member of an eccentric and capricious American family living in Paris, but at the last moment, after the wedding invitations had been sent out, she broke off the engagement and almost immediately married a fellow American. Drabble comments that Bennett was well rid of her, but it was a painful episode in his life. In early 1907 he met Marguerite Soulié (1874–1960), who soon became first a friend and then a lover. In May he was taken ill with a severe gastric complaint, and Marguerite moved into his flat to look after him. They became still closer, and in July 1907, shortly after his fortieth birthday, they were married at the

In 1905 Bennett became engaged to Eleanor Green, a member of an eccentric and capricious American family living in Paris, but at the last moment, after the wedding invitations had been sent out, she broke off the engagement and almost immediately married a fellow American. Drabble comments that Bennett was well rid of her, but it was a painful episode in his life. In early 1907 he met Marguerite Soulié (1874–1960), who soon became first a friend and then a lover. In May he was taken ill with a severe gastric complaint, and Marguerite moved into his flat to look after him. They became still closer, and in July 1907, shortly after his fortieth birthday, they were married at the Mairie

In local government, a city hall, town hall, civic centre (in the UK or Australia), guildhall, or a municipal building (in the Philippines), is the chief administrative building of a city, town, or other municipality. It usually houses ...

of the 9th arrondissement. The marriage was childless.Swinnerton, Frank"Bennett, (Enoch) Arnold (1867–1931)"

, ''Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 1949. Retrieved 1 June 2020 Early in 1908 the couple moved from the rue d'Aumale to the Villa des Néfliers in Fontainebleau-Avon, about 40 miles (64 km) south-east of Paris. Lucas comments that the best of the novels written while in France – ''Whom God Hath Joined'' (1906), ''The Old Wives' Tale'' (1908), and ''

Clayhanger

The ''Clayhanger'' Family is a series of novels by Arnold Bennett, published between 1910 and 1918. Though the series is commonly referred to as a "trilogy", and the first three novels were published in a single volume, as ''The Clayhanger Famil ...

'' (1910) – "justly established Bennett as a major exponent of realistic fiction". In addition to these, Bennett published lighter novels such as '' The Card'' (1911). His output of literary journalism included articles for T. P. O'Connor

Thomas Power O'Connor (5 October 1848 – 18 November 1929), known as T. P. O'Connor and occasionally as Tay Pay (mimicking his own pronunciation of the initials ''T. P.''), was an Irish nationalist politician and journalist who served as a ...

's ''T. P.'s Weekly

Thomas Power O'Connor (5 October 1848 – 18 November 1929), known as T. P. O'Connor and occasionally as Tay Pay (mimicking his own pronunciation of the initials ''T. P.''), was an Irish nationalist politician and journalist who served as a ...

'' and the left-wing ''The New Age

''The New Age'' was a British weekly magazine (1894–1938), inspired by Fabian socialism, and credited as a major influence on literature and the arts during its heyday from 1907 to 1922, when it was edited by Alfred Richard Orage. It published ...

''; his pieces for the latter, published under a pen-name, were concise literary essays aimed at "the general cultivated reader", a form taken up by a later generation of writers including J. B. Priestley and V. S. Pritchett

Sir Victor Sawdon Pritchett (also known as VSP; 16 December 1900 – 20 March 1997) was a British writer and literary critic.

Pritchett was known particularly for his short stories, collated in a number of volumes. His non-fiction works incl ...

.

In 1911 Bennett made a financially rewarding visit to the US, which he later recorded in his 1912 book '' Those United States''. Crossing the Atlantic aboard the ''Lusitania

Lusitania (; ) was an ancient Iberian Roman province located where modern Portugal (south of the Douro river) and

a portion of western Spain (the present Extremadura and the province of Salamanca) lie. It was named after the Lusitani or Lusita ...

'', he visited not only New York and Boston but also Chicago, Indianapolis, Washington and Philadelphia in a tour that was described by US publisher George Doran as "one of continuous triumph": in the first three days of his stay in New York he was interviewed 26 times by journalists. While rival E.P. Dutton

E. P. Dutton was an American book publishing company. It was founded as a book retailer in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1852 by Edward Payson Dutton. Since 1986, it has been an imprint of Penguin Group.

Creator

Edward Payson Dutton (January 4, ...

had secured rights to such Bennett novels as ''Hilda Lessways'' and ''the Card'' (retitled ''Denry the Audacious''), Doran, who travelled everywhere with Bennett while in America, was the publisher of Bennett’s wildly successful ‘pocket philosophies’ '' How to Live on Twenty-Four Hours a Day'' and ''Mental Efficiency.'' Of these books the influential critic Willard Huntington Wright

S. S. Van Dine (also styled S.S. Van Dine) is the pseudonym used by American art critic Willard Huntington Wright (October 15, 1888 – April 11, 1939) when he wrote detective novels. Wright was active in avant-garde cultural circles in pre-Wor ...

wrote that Bennett had "turned preacher and a jolly good preacher he is". While in the US Bennett also sold the serial rights of his forthcoming novel, ''The Price of Love'' (1913–14), to '' Harpers'' for £2,000, eight essays to ''Metropolitan

Metropolitan may refer to:

* Metropolitan area, a region consisting of a densely populated urban core and its less-populated surrounding territories

* Metropolitan borough, a form of local government district in England

* Metropolitan county, a typ ...

'' magazine for a total of £1,200, and the American rights of a successor to ''Clayhanger'' for £3,000.

During his ten years in France he had gone from a moderately well-known writer enjoying modest sales to outstanding success. Swinnerton comments that in addition to his large sales, Bennett's critical prestige was at its zenith.

Return to England

In 1912, after an extended stay at the Hotel Californie in Cannes, during which time he wrote ''The Regent'', a light-hearted sequel to ''The Card'', Bennett and his wife moved from France to England. Initially they lived in Putney, but "determined to become an English country landowner", he boughtComarques

This is a list of the 42 ''comarques'' (singular ''comarca'', , ) into which Catalonia is divided. A ''Comarcas of Spain, comarca'' is a group of municipalities of Catalonia, municipalities, roughly equivalent to a county in the US or a district ...

, an early-18th-century country house at Thorpe-le-Soken, Essex, and moved there in February 1913. Among his early concerns, once back in England, was to succeed as a playwright. He had dabbled previously but his inexperience showed. ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' thought his 1911 comedy ''The Honeymoon'', staged in the West End with a starry cast, had "one of the most amusing first acts we have ever seen", but fell flat in the other two acts."Royalty Theatre", ''The Times'', 7 October 1911, p. 8 In the same year Bennett met the playwright Edward Knoblauch

Edward Knoblock (born Edward Gustavus Knoblauch; 7 April 1874 – 19 July 1945) was a playwright and novelist, originally American and later a naturalised British citizen. He wrote numerous plays, often at the rate of two or three a year, of whic ...

(later Knoblock) and they collaborated on ''Milestones

A milestone is a marker of distance along roads.

Milestone may also refer to:

Measurements

*Milestone (project management), metaphorically, markers of reaching an identifiable stage in any task or the project

*Software release life cycle state, s ...

'', the story of the generations of a family seen in 1860, 1885 and 1912. The combination of Bennett's narrative gift and Knoblauch's practical experience proved a success."Drama", ''The Athenaeum'', 9 March 1912, p. 291 The play was strongly cast, received highly favourable notices, ran for more than 600 performances in London and over 200 in New York, and made Bennett a great deal of money. His next play, '' The Great Adventure'' (1913), a stage version of his novel ''Buried Alive'' (1908), was similarly successful.Wearing, p. 327

Bennett's attitude to the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

was that British politicians had been at fault in failing to prevent it, but that once it had become inevitable it was right that Britain should join its allies against the Germans. He concentrated his attention on journalism, aiming to inform and encourage the public in Britain and allied and neutral countries. He served on official and unofficial committees, and in 1915 he was invited to visit France to see conditions at the front and write about them for readers at home. The collected impressions appeared in a book called ''Over There'' (1915). He was still writing novels, however: ''These Twain'', the third in his Clayhanger trilogy, was published in 1916 and in 1917 he completed a sequel, ''The Roll Call'', which ends with its hero, George Cannon, enlisting in the army. Wartime London was the setting for Bennett's ''The Pretty Lady'' (1918), about a high-class French ''cocotte'': although well reviewed, because of its subject-matter the novel provoked "a Hades of a row" and some booksellers refused to sell it.

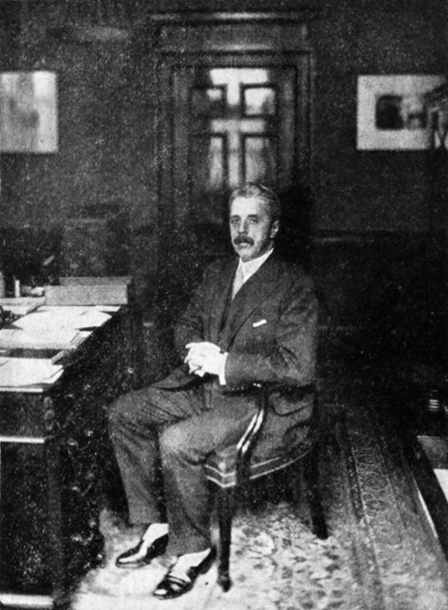

When Lord Beaverbrook

William Maxwell Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook (25 May 1879 – 9 June 1964), generally known as Lord Beaverbrook, was a Canadian-British newspaper publisher and backstage politician who was an influential figure in British media and politics o ...

became Minister of Information in February 1918 he appointed Bennett to take charge of propaganda in France. Beaverbrook fell ill in October 1918 and made Bennett director of propaganda, in charge of the whole ministry for the last weeks of the war. At the end of 1918 Bennett was offered, but declined, a knighthood

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

in the new Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established ...

instituted by George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

Born duri ...

.Pound, p. 279 The offer was renewed some time later, and again Bennett refused it. One of his closest associates at the time suspected that he was privately hoping for the more prestigious Order of Merit

The Order of Merit (french: link=no, Ordre du Mérite) is an order of merit for the Commonwealth realms, recognising distinguished service in the armed forces, science, art, literature, or for the promotion of culture. Established in 1902 by K ...

.

As the war was ending, Bennett returned to his theatrical interests, although not primarily as a playwright. In November 1918 he became chairman, with Nigel Playfair as managing director, of the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith

The Lyric Theatre, also known as the Lyric Hammersmith, is a theatre on Lyric Square, off King Street, Hammersmith, London.

. Among their productions were ''Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

'' by John Drinkwater, and '' The Beggar's Opera'', which, in Swinnerton's phrase, "caught different moods of the post-war spirit", and ran for 466 and 1,463 performances respectively.

Last years

In 1921 Bennett and his wife

In 1921 Bennett and his wife legally separated

Legal separation (sometimes judicial separation, separate maintenance, divorce ', or divorce from bed-and-board) is a legal process by which a married couple may formalize a separation while remaining legally married. A legal separation is gra ...

. They had been drifting apart for some years and Marguerite had taken up with Pierre Legros, a young French lecturer. Bennett sold Comarques and lived in London for the rest of his life, first in a flat near Bond Street

Bond Street in the West End of London links Piccadilly in the south to Oxford Street in the north. Since the 18th century the street has housed many prestigious and upmarket fashion retailers. The southern section is Old Bond Street and the l ...

in the West End, on which he had taken a lease during the war. For much of the 1920s he was widely known to be the highest-paid literary journalist in England, contributing a weekly column to Beaverbrook's ''Evening Standard

The ''Evening Standard'', formerly ''The Standard'' (1827–1904), also known as the ''London Evening Standard'', is a local free daily newspaper in London, England, published Monday to Friday in tabloid format.

In October 2009, after be ...

'' under the title 'Books and Persons'; according to Frank Swinnerton

Frank Arthur Swinnerton (12 August 1884 – 6 November 1982) was an English novelist, critic, biographer and essayist.

He was the author of more than 50 books, and as a publisher's editor helped other writers including Aldous Huxley and Lytton S ...

these articles were "extraordinarily successful and influential ... and made a number of new reputations". By the end of his career, Bennett had contributed to more than 100 newspapers, magazines and other publications. He continued to write novels and plays as assiduously as before the war.

Swinnerton writes, "Endless social engagements; inexhaustible patronage of musicians, actors, poets, and painters; the maximum of benevolence to friends and strangers alike, marked the last ten years of his life". Hugh Walpole, James Agate and Osbert Sitwell were among those who testified to Bennett's generosity. Sitwell recalled a letter Bennett wrote in the 1920s:

In 1922 Bennett met and fell in love with an actress, Dorothy Cheston (1891–1977). Together they set up home in Cadogan Square

Cadogan Square () is a residential square in Knightsbridge, London, that was named after Earl Cadogan. Whilst it is mainly a residential area, some of the properties are used for diplomatic and educational purposes (notably Hill House School). ...

, where they stayed until moving in 1930 to Chiltern Court, Baker Street

Chiltern Court, Baker Street, London, is a large block of flats at the street's northern end, facing Regent's Park and Marylebone Road. It was built between 1927 and 1929 above the Baker Street tube station by the Metropolitan Railway. Originally ...

. As Marguerite would not agree to a divorce, Bennett was unable to marry Dorothy, and in September 1928, having become pregnant, she changed her name by deed poll

A deed poll (plural: deeds poll) is a legal document binding on a single person or several persons acting jointly to express an intention or create an obligation. It is a deed, and not a contract because it binds only one party (law), party.

Et ...

to Dorothy Cheston Bennett.Drabble, p. 308 The following April she gave birth to the couple's only child, Virginia Mary (1929–2003). She continued to appear as an actress, and produced and starred in a revival of ''Milestones'' which was well reviewed, but had only a moderate run.Drabble, p. 335 Bennett had mixed feelings about her continuing stage career, but did not seek to stop it.

During a holiday in France with Dorothy in January 1931, Bennett twice drank tap-water – not, at the time, a safe thing to do there. On his return home he was taken ill; influenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptoms ...

was diagnosed at first, but the illness was typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

; after several weeks of unsuccessful treatment he died in his flat at Chiltern Court on 27 March 1931, aged 63.

Bennett was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium and his ashes were interred in Burslem Cemetery in his mother's grave. A memorial service was held on 31 March 1931 at St Clement Danes

St Clement Danes is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London. It is situated outside the Royal Courts of Justice on the Strand. Although the first church on the site was reputedly founded in the 9th century by the Danes, the current ...

, London, attended by leading figures from journalism, literature, music, politics and theatre, and, in Pound's words, many men and women who at the end of the service "walked out into a London that for them would never be the same again".

Works

From the outset, Bennett believed in the "democratisation of art which it is surely the duty of the minority to undertake". He admired some of the modernist writers of his time, but strongly disapproved of their conscious appeal to a small élite and their disdain for the general reader. Bennett believed that literature should be inclusive, accessible by ordinary people.Koenigsberger, Kurt"Bennett, Arnold"

, ''The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature'', Oxford University Press, 2006. Retrieved 4 June 2020 From the start of his career, Bennett was aware of the appeal of regional fiction.

Anthony Trollope

Anthony Trollope (; 24 April 1815 – 6 December 1882) was an English novelist and civil servant of the Victorian era. Among his best-known works is a series of novels collectively known as the '' Chronicles of Barsetshire'', which revolves ar ...

, George Eliot and Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy (2 June 1840 – 11 January 1928) was an English novelist and poet. A Victorian realist in the tradition of George Eliot, he was influenced both in his novels and in his poetry by Romanticism, including the poetry of William Word ...

had created and sustained their own locales, and Bennett did the same with his Five Towns, drawing on his experiences as a boy and young man. As a realistic writer he followed the examples of the authors he admired – above all George Moore, but also Balzac, Flaubert and Maupassant among French writers, and Dostoevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (, ; rus, Фёдор Михайлович Достоевский, Fyódor Mikháylovich Dostoyévskiy, p=ˈfʲɵdər mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪdʑ dəstɐˈjefskʲɪj, a=ru-Dostoevsky.ogg, links=yes; 11 November 18219 ...

, Turgenev and Tolstoy among Russians. In writing about the Five Towns Bennett aimed to portray the experiences of ordinary people coping with the norms and constraints of the communities in which they lived. J. B. Priestley considered that the next influence on Bennett's fiction was his time in London in the 1890s, "engaged in journalism and ingenious pot-boiling of various kinds".''Quoted'' in Howarth, pp. 11–12

Novels and short stories

Bennett is remembered chiefly for his novels and short stories. The best known are set in, or feature people from, the six towns of the Potteries of his youth. He presented the region as "the Five Towns", which correspond closely with their originals: the real-life Burslem,

Bennett is remembered chiefly for his novels and short stories. The best known are set in, or feature people from, the six towns of the Potteries of his youth. He presented the region as "the Five Towns", which correspond closely with their originals: the real-life Burslem, Hanley

Hanley is one of the six towns that, along with Burslem, Longton, Fenton, Tunstall and Stoke-upon-Trent, amalgamated to form the City of Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire, England.

Hanley is the ''de facto'' city centre, having long been the ...

, Longton Longton may refer to several places:

* Longton, Kansas, United States

* Longton, Lancashire, United Kingdom

* Longton, Staffordshire, United Kingdom

See also

* Longtan (disambiguation)

* Longtown (disambiguation) Longtown may refer to several plac ...

, Stoke

Stoke is a common place name in the United Kingdom.

Stoke may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

The largest city called Stoke is Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire. See below.

Berkshire

* Stoke Row, Berkshire

Bristol

* Stoke Bishop

* Stok ...

and Tunstall become Bennett's Bursley, Hanbridge, Longshaw, Knype and Turnhill. These "Five Towns" make their first appearance in Bennett's fiction in ''Anna of the Five Towns

''Anna of the Five Towns'' is a novel by Arnold Bennett, first published in 1902 and one of his best-known works.

Plot background

The plot centres on Anna Tellwright, daughter of a wealthy but miserly and dictatorial father, living in the P ...

'' (1902) and are the setting for further novels including ''Leonora'' (1903), ''Whom God Hath Joined'' (1906), ''The Old Wives' Tale'' (1908) and the Clayhanger

The ''Clayhanger'' Family is a series of novels by Arnold Bennett, published between 1910 and 1918. Though the series is commonly referred to as a "trilogy", and the first three novels were published in a single volume, as ''The Clayhanger Famil ...

trilogy – ''Clayhanger'' (1910), ''Hilda Lessways'' (1911) and ''These Twain'' (1916) – as well as for dozens of short stories. Bennett's fiction portrays the Five Towns with what ''The Oxford Companion to English Literature'' calls "an ironic but affectionate detachment, describing provincial life and culture in documentary detail, and creating many memorable characters". In later life Bennett said that the writer George Moore was "the father of all my Five Towns books" as it was reading Moore's 1885 novel ''A Mummer's Wife'', set in the Potteries, that "opened my eyes to the romantic nature of the district I had blindly inhabited for over twenty years".

It was not only locations on which Bennett drew for his fiction. Many of his characters are discernibly based on real people in his life. His Lincoln's Inn friend John Eland was a source for Mr Aked in Bennett's first novel, ''A Man from the North'' (1898); ''A Great Man'' (1903) contains a character with echoes of his Parisienne friend Chichi; Darius Clayhanger's early life is based on that of a family friend and Bennett himself is seen in Edwin in ''Clayhanger''. He has been criticised for making literary use in that novel of the distressing details of his father's decline into senility, but in Pound's view, in committing the details to paper Bennett was unburdening himself of painful memories.

''These Twain'' is Bennett's "last extended study of Five Towns life". The novels he wrote in the 1920s are largely set in London and thereabouts: ''Riceyman Steps

''Riceyman Steps'' is a novel by British novelist Arnold Bennett, first published in 1923 and winner of that year's James Tait Black Memorial Prize for fiction. It follows a year in the life of Henry Earlforward, a miserly second-hand bookshop ow ...

'' (1923), for instance, generally regarded as the best of Bennett's post-war novels, was set in Clerkenwell

Clerkenwell () is an area of central London, England.

Clerkenwell was an ancient parish from the mediaeval period onwards, and now forms the south-western part of the London Borough of Islington.

The well after which it was named was redisco ...

: it was awarded the James Tait Black novel prize for 1923, "the first prize for a book I ever had," Bennett noted in his journal on 18 October 1924. His ''Lord Raingo'' (1926), described by Dudley Barker as "one of the finest of political novels in the language", benefited from Bennett's own experience in the Ministry of Information and his subsequent friendship with Beaverbrook: John Lucas states that "As a study of what goes on in the corridors of power 'Lord Raingo''has few equals". And Bennett's final – and longest – novel, '' Imperial Palace'' (1930), is set in a grand London hotel reminiscent of the Savoy

Savoy (; frp, Savouè ; french: Savoie ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps.

Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south.

Savo ...

, whose directors assisted him in his preliminary research.

Bennett usually gave his novels subtitles; the most frequent was "A fantasia on modern themes", individual books were called "A frolic" or "A melodrama", but he was sparing with the label "A novel" which he used for only a few of his books – for instance ''Anna of the Five Towns'', ''Leonora'', ''Sacred and Profane Love'', ''The Old Wives' Tale'', ''The Pretty Lady'' (1918) and ''Riceyman Steps''. Literary critics have followed Bennett in dividing his novels into groups. The literary scholar Kurt Koenigsberger proposes three categories. In the first are the long narratives – "freestanding, monumental artefacts" – ''Anna of the Five Towns'', ''The Old Wives' Tale'', ''Clayhanger'' and ''Riceyman Steps'', which "have been held in high critical regard since their publication". Koenigsberger writes that the "Fantasias" such as ''The Grand Babylon Hotel'' (1902), ''Teresa of Watling Street'' (1904) and '' The City of Pleasure'' (1907), have "mostly passed from public attention along with the 'modern' conditions they exploit". His third group includes "Idyllic Diversions" or "Stories of Adventure", including ''Helen with the High Hand'' (1910), ''The Card'' (1911), and ''The Regent'' (1913), which "have sustained some enduring critical and popular interest, not least for their amusing treatment of cosmopolitanism and provinciality".

Bennett published 96 short stories in seven volumes between 1905 and 1931. His ambivalence about his native town is vividly seen in "The Death of Simon Fuge" in the collection ''The Grim Smile of the Five Towns'' (1907), judged by Lucas the finest of all the stories. His chosen locations ranged widely, including Paris and Venice as well as London and the Five Towns. As with his novels, he would sometimes give a story a label, calling "The Matador of the Five Towns" (1912) "a tragedy" and "Jock-at-a-Venture" from the same collection "a frolic". The short stories, particularly those in ''Tales of the Five Towns'' (1905), ''The Grim Smile of the Five Towns'' (1907), and ''The Matador of the Five Towns'' contain some of the most striking examples of Bennett's concern for realism, with an unflinching narrative focus on what Lucas calls "the drab, the squalid, and the mundane". In 2010 and 2011 two further volumes of Bennett's hitherto uncollected short stories were published: they range from his earliest work written in the 1890s, some under the pseudonym Sarah Volatile, to US magazine commissions from the late 1920s.

Stage and screen

In 1931 the critic Graham Sutton, looking back at Bennett's career in the theatre, contrasted his achievements as a playwright with those as a novelist, suggesting that Bennett was a complete novelist but a not-entirely-complete dramatist. His plays were clearly those of a novelist: "He tends to lengthy speeches. Sometimes he overwrites a part, as though distrusting the actor. He is more interested in what his people are than in what they visibly do. He 'thinks nowt' of mere slickness of plot."Sutton, Graham. "The Plays of Arnold Bennett", ''The Bookman'', December 1931, p. 165 Bennett's lack of a theatrical grounding showed in the uneven construction of some of his plays, such as his 1911 comedy ''The Honeymoon'', which played for 125 performances from October 1911. The highly successful ''Milestones'' was seen as impeccably constructed, but the credit for that was given to his craftsmanlike collaborator, Edward Knoblauch (Bennett being credited with the inventive flair of the piece). By far his most successful solo effort in the theatre was ''The Great Adventure'', based on his 1908 novel '' Buried Alive'', which ran in the West End for 674 performances, from March 1913 to November 1914. Sutton praised its "new strain of impish and sardonic fantasy" and rated it a much finer play than ''Milestones''. After the First World War, Bennett wrote two plays on metaphysical questions, ''Sacred and Profane Love'' (1919, adapted from his novel) and ''Body and Soul'' (1922), which made little impression. '' The Saturday Review'' praised the "shrewd wit" of the former, but thought it "false in its essentials ... superficial in its accidentals". Of the latter, the critic Horace Shipp wondered "how the author of ''Clayhanger'' and ''The Old Wives' Tale'' could write such third-rate stuff". Bennett had more success in a final collaboration withEdward Knoblock

Edward Knoblock (born Edward Gustavus Knoblauch; 7 April 1874 – 19 July 1945) was a playwright and novelist, originally American and later a naturalised British citizen. He wrote numerous plays, often at the rate of two or three a year, of whic ...

(as Knoblauch had become during the war) with ''Mr Prohack'' (1927), a comedy based on his 1922 novel; one critic wrote "I could have enjoyed the play had it run to double its length", but even so he judged the middle act weaker than the outer two. Sutton concludes that Bennett's ''forte'' was character, but that the competence of his technique was variable. The plays are seldom revived, although some have been adapted for television.

Bennett wrote two opera libretti

A libretto (Italian for "booklet") is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or musical. The term ''libretto'' is also sometimes used to refer to the text of major litu ...

for the composer Eugene Goossens: ''Judith'' (one act, 1929) and ''Don Juan'' (four acts, produced in 1937 after the writer's death). There were comments that Goossens's music lacked tunes and Bennett's libretti were too wordy and literary. The critic Ernest Newman

Ernest Newman (30 November 1868 – 7 July 1959) was an English music critic and musicologist. ''Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians'' describes him as "the most celebrated British music critic in the first half of the 20th century." His ...

defended both works, finding Bennett's libretto for Judith "a drama told simply and straightforwardly" and ''Don Juan'' "the best thing that English opera has so far produced … the most dramatic and stageworthy", but though politely received, both operas vanished from the repertory after a few performances.

Bennett took a keen interest in the cinema, and in 1920 wrote ''The Wedding Dress'', a scenario for a silent movie, at the request of Jesse Lasky of the Famous Players

Famous Players Limited Partnership, DBA Famous Players, is a Canadian-based subsidiary of Cineplex Entertainment. As an independent company, it existed as a film exhibitor and cable television service provider. Famous Players operated numerous m ...

film company. It was never made, though Bennett wrote a full-length treatment, assumed to be lost until his daughter Virginia found it in a drawer in her Paris home in 1983; subsequently the script was sold to the Potteries Museum and Art Gallery

The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery is in Bethesda Street, Hanley, one of the six towns of Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire. Admission is free.

One of the four local authority museums in the city, the other three being Gladstone Pottery Museum, ...

and was finally published in 2013. In 1928 Bennett wrote the scenario for the silent film ''Piccadilly

Piccadilly () is a road in the City of Westminster, London, to the south of Mayfair, between Hyde Park Corner in the west and Piccadilly Circus in the east. It is part of the A4 road that connects central London to Hammersmith, Earl's Court, ...

'', directed by E. A. Dupont

Ewald André Dupont (25 December 1891 – 12 December 1956) was a German film director, one of the pioneers of the German film industry. He was often credited as E. A. Dupont.

Early career

A newspaper columnist in 1916, Dupont became a screenwri ...

and starring Anna May Wong

Wong Liu Tsong (January 3, 1905 – February 3, 1961), known professionally as Anna May Wong, was an American actress, considered the first Chinese-American movie star in Hollywood, as well as the first Chinese-American actress to gain intern ...

, described by the British Film Institute

The British Film Institute (BFI) is a film and television charitable organisation which promotes and preserves film-making and television in the United Kingdom. The BFI uses funds provided by the National Lottery to encourage film production, ...

as "one of the true greats of British silent films". In 1929, the year the film came out, Bennett was in discussion with a young Alfred Hitchcock

Sir Alfred Joseph Hitchcock (13 August 1899 – 29 April 1980) was an English filmmaker. He is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in the history of cinema. In a career spanning six decades, he directed over 50 featur ...

to script a silent film, ''Punch and Judy'', which foundered on artistic disagreements and Bennett's refusal to see the film as a "talkie" rather than silent. His original scenario, acquired by Pennsylvania State University

The Pennsylvania State University (Penn State or PSU) is a Public university, public Commonwealth System of Higher Education, state-related Land-grant university, land-grant research university with campuses and facilities throughout Pennsylvan ...

, was published in the UK in 2012.

Journalism and self-help books

Bennett published more than two dozen non-fiction books, among which eight could be classified as "self-help": the most enduring is '' How to Live on 24 Hours a Day'' (1908), which is still in print and has been translated into several languages. Other "self-help" volumes include ''How to Become an Author'' (1903), ''The Reasonable Life'' (1907), '' Literary Taste: How to Form It'' (1909), ''The Human Machine'' (1908), ''Mental Efficiency'' (1911), ''The Plain Man and his Wife'' (1913), ''Self and Self-Management'' (1918) and ''How to Make the Best of Life'' (1923). They were, says Swinnerton, "written for small fees and with a real desire to assist the ignorant". According to the Harvard academic Beth Blum, these books "advance less scientific versions of the argument for mental discipline espoused by William James". In his biography of Bennett Patrick, Donovan argues that in the US "the huge appeal to the ordinary readers" of his self-help books "made his name stand out vividly from other English writers across the massive, fragmented American market."Donovan, p. 99 As Bennett put it to his London-based agent J. B. Pinker, these "pocket philosophies are just the sort of book for the American public". However, ''How to Live on 24 Hours'' was aimed initially at "the legions of clerks and typists and other meanly paid workers caught up in the explosion of British office jobs around the turn of the century … they offered a strong message of hope from somebody who so well understood their lives". Bennett never lost his journalistic instincts, and throughout his life sought and responded to newspaper and magazine commissions with varying degrees of enthusiasm: "from the start of the 1890s right up to the week of his death there would never be a period when he was not churning out copy for newspapers and magazines". In a journal entry at the end of 1908, for instance, he noted that he had written "over sixty newspaper articles" that year; in 1910 the figure was "probably about 80 other articles". While living in Paris he was a regular contributor to ''T. P.'s Weekly''; later he reviewed for ''The New Age

''The New Age'' was a British weekly magazine (1894–1938), inspired by Fabian socialism, and credited as a major influence on literature and the arts during its heyday from 1907 to 1922, when it was edited by Alfred Richard Orage. It published ...

'' under the pseudonym Jacob Tonson and was associated with the ''New Statesman

The ''New Statesman'' is a British political and cultural magazine published in London. Founded as a weekly review of politics and literature on 12 April 1913, it was at first connected with Sidney and Beatrice Webb and other leading members ...

'' as not only a writer but also a director.

Journals

Inspired by the ''Journal des Goncourt

The Goncourt Journal was a diary written in collaboration by the brothers Edmond and Jules de Goncourt from 1850 up to Jules' death in 1870, and then by Edmond alone up to a few weeks before his own death in 1896. It forms an unrivalled and enti ...

'', Bennett kept a journal throughout his adult life. Swinnerton says that it runs to a million words; it has not been published in full. Edited extracts were issued in three volumes, in 1932 and 1933. According to Hugh Walpole, the editor, Newman Flower

Sir Walter Newman Flower (8 July 1879 – 12 March 1964) was an English publisher and author. He transformed the fortunes of the publishing house Orion Publishing Group, Cassell & Co, and later became its proprietor. As an author, he published stu ...

, "was so appalled by much of what he found in the journals that he published only brief extracts, and those the safest".Lyttelton and Hart-Davis, p. 176 Whatever Flower censored, the extracts he selected were not always "the safest": he let some defamatory remarks through, and in 1935 he, the publishers and printers had to pay an undisclosed sum to the plaintiff in one libel suit and £2,500 in another.

Critical reputation

Novels and short stories

The literary

The literary modernists

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

of his day deplored Bennett's books, and those of his well-known contemporaries H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells"Wells, H. G."

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

"Arnold Bennett"

''The Diner's Dictionary'', Oxford University Press, 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2020 by the chef"Marcus Wareing's omelette Arnold Bennett"

. ''Delicious''

"Easy Omelette Arnold Bennett"

, Delia Online; an

"Savoy Grill Arnold Bennett Omelette Recipe"

, Gordon Ramsay Restaurants. All retrieved 3 June 2020 and a variant remains on the menu at the Savoy Grill.

Website of the Arnold Bennett Society

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bennett, Arnold 1867 births 1931 deaths 19th-century British short story writers 19th-century English novelists 20th-century British short story writers 20th-century English diarists 20th-century English dramatists and playwrights 20th-century English novelists 20th-century English screenwriters Alumni of the University of London British propagandists English crime fiction writers English expatriates in France English male dramatists and playwrights English male novelists English opera librettists English self-help writers Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn James Tait Black Memorial Prize recipients People from Hanley, Staffordshire Victorian novelists Deaths from typhoid fever Infectious disease deaths in England Burials in Staffordshire

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

John Galsworthy

John Galsworthy (; 14 August 1867 – 31 January 1933) was an English novelist and playwright. Notable works include ''The Forsyte Saga'' (1906–1921) and its sequels, ''A Modern Comedy'' and ''End of the Chapter''. He won the Nobel Prize i ...

. Of the three, Bennett drew the most opprobrium from modernists such as Virginia Woolf

Adeline Virginia Woolf (; ; 25 January 1882 28 March 1941) was an English writer, considered one of the most important modernist 20th-century authors and a pioneer in the use of stream of consciousness as a narrative device.

Woolf was born i ...

, Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an expatriate American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a Fascism, fascist collaborator in Italy during World War II. His works ...

and Wyndham Lewis who regarded him as representative of an outmoded and rival literary culture.Howarth, p. 5; and Drabble p. 289 There was a strong element of class-consciousness and snobbery in the modernists' attitude: Woolf accused Bennett of having "a shopkeeper's view of literature" and in her essay " Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown" accused Bennett, Galsworthy and Wells of ushering in an "age when character disappeared or was mysteriously engulfed".

In a 1963 study of Bennett, James Hepburn summed up and dissented from the prevailing views of the novels, listing three related evaluative positions taken individually or together by almost all Bennett's critics: that his Five Towns novels are generally superior to his other work, that he and his art declined after ''The Old Wives' Tale'' or ''Clayhanger'', and that there is a sharp and clear distinction between the good and bad novels. Hepburn countered that one of the novels most frequently praised by literary critics is ''Riceyman Steps'' (1923) set in Clerkenwell, London, and dealing with material imagined rather than observed by the author. On the third point he commented that although received wisdom was that ''The Old Wives' Tale'' and ''Clayhanger'' are good and ''Sacred and Profane Love'' and ''Lillian'' are bad, there was little consensus about which other Bennett novels were good, bad or indifferent. He instanced ''The Pretty Lady'' (1918), on which critical opinion ranged from "cheap and sensational" ... "sentimental melodrama" to "a great novel". Lucas (2004) considers it "a much underrated study of England during the war years, especially in its sensitive feeling for the destructive frenzy that underlay much apparently good-hearted patriotism".

In 1974 Margaret Drabble

Dame Margaret Drabble, Lady Holroyd, (born 5 June 1939) is an English biographer, novelist and short story writer.

Drabble's books include '' The Millstone'' (1965), which won the following year's John Llewellyn Rhys Memorial Prize, and ''Jer ...

published ''Arnold Bennett'', a literary biography. In the foreword she demurred at the critical dismissal of Bennett:

Writing in the 1990s the literary critic John Carey called for a reappraisal of Bennett in his book ''The Intellectuals and the Masses'' (1992):

In 2006 Koenigsberger commented that one reason why Bennett's novels had been sidelined, apart from "the exponents of modernism who recoiled from his democratising aesthetic programme", was his attitude to gender. His books include the pronouncements "the average man has more intellectual power than the average woman" and "women as a sex love to be dominated"; Koenigsberger nevertheless praises Bennett's "sensitive and oft-praised portrayals of female figures in his fiction".

Lucas concludes his study with the comment that Bennett's realism may be limited by his cautious assumption that things are as they are and will not change. Nevertheless, in Lucas's view, successive generations of reader have admired Bennett's best work, and future generations are certain to do so.

Crime fiction

Bennett dabbled in crime fiction, in ''The Grand Babylon Hotel'' and ''The Loot of Cities'' (1905). In ''Queen's Quorum'' (1951), a survey of crime fiction, Ellery Queen listed the latter among the 100 most important works in the genre. This collection of stories recounts the adventures of a millionaire who commits crimes to achieve his idealistic ends. Although it was "one of his least known works," it was nevertheless "of unusual interest, both as an example of Arnold Bennett's early work and as an early example of dilettante detectivism".Legacy

Arnold Bennett Society

The Society was founded in 1954 "to promote the study and appreciation of the life, works and times not only of Arnold Bennett himself but also of other provincial writers, with particular relationship to North Staffordshire". In 2021 its president was Denis Eldin, Bennett's grandson; among the vice-presidents was Margaret Drabble. In 2017 the society instituted an annual Arnold Bennett Prize as part of author's 150th anniversary celebrations, to be awarded to an author who was born, lives or works in North Staffordshire and has published a book in the relevant year, or to the author of a book which features the region. In 2017 John Lancaster won the award for his poetry collection ''Potters: A Division of Labour''. Subsequent winners have been Jan Edwards for her novel ''Winter Downs'' (2018),Charlotte Higgins

Charlotte Higgins, (born 6 September 1972) is a British writer and journalist.

Early life and education

Higgins was born in Stoke-on-Trent, the daughter of a doctor and a nurse, and received her secondary education at a local independent scho ...

for ''Red Thread: On Mazes and Labyrinths'' (2019) and Lisa Blower for her story collection ''It's Gone Dark Over Bill's Mother's'' (2020). The prize was not awarded in 2021 because of the Covid-19 situation, but in 2022 it was won by John Pye, a former detective inspector turned crime writer, for his novel ''Where the Silent Screams Are Loudest.'' The prize in 2023 went to Philip Nanney Williams for his book ''Adams: Britain's Oldest Potting Dynasty''.

Plaques and statuary

Bennett has been commemorated by several plaques. Hugh Walpole unveiled one at Comarques in 1931, and in the same year another was placed at Bennett's birthplace in Hanley. A plaque to and bust of Bennett were unveiled in Burslem in 1962, and there areblue plaques

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom and elsewhere to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving as a historical marker. The term i ...

commemorating him at the house in Cadogan Square where he lived from 1923 to 1930 and on the house in Cobridge

Cobridge is an area of Stoke-on-Trent, in the City of Stoke-on-Trent district, in the county of Staffordshire, England. Cobridge was marked on the 1775 Yates map as 'Cow Bridge' and was recorded in Ward records (1843) as Cobridge Gate.

Cobrid ...

where he lived in his youth. The southern Baker Street entrance of Chiltern Court has a plaque to Bennett on the left and another to H. G. Wells on the right. A blue plaque has been placed on the wall of Bennett's home in Fontainebleau.

There is a two-metre-high bronze statue of Bennett outside The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery in Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, unveiled on 27 May 2017 during the events marking the 150th anniversary of his birth.

Archives

There are substantial archives of Bennett's papers and artworks, including drafts, diaries, letters, photographs and watercolours, at The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery in Stoke-on-Trent and at Keele University. Other Bennett papers are held byUniversity College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = ...

, the British Library

The British Library is the national library of the United Kingdom and is one of the largest libraries in the world. It is estimated to contain between 170 and 200 million items from many countries. As a legal deposit library, the British ...

, Staffordshire University's Special Collections and, in the US, Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

and Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wor ...

universities and the Berg Collection in the New York Public Library

The New York Public Library (NYPL) is a public library system in New York City. With nearly 53 million items and 92 locations, the New York Public Library is the second largest public library in the United States (behind the Library of Congress ...

.

Omelettes

Bennett shares with the composerGioachino Rossini

Gioachino Antonio Rossini (29 February 1792 – 13 November 1868) was an Italian composer who gained fame for his 39 operas, although he also wrote many songs, some chamber music and piano pieces, and some sacred music. He set new standards f ...

, the singer Nellie Melba and some other celebrities the distinction of having a well-known dish named in his honour. An omelette Arnold Bennett is one that incorporates smoked

Smoking is the process of flavoring, browning, cooking, or preserving food by exposing it to smoke from burning or smoldering material, most often wood. Meat, fish, and ''lapsang souchong'' tea are often smoked.

In Europe, alder is the tradi ...

haddock

The haddock (''Melanogrammus aeglefinus'') is a saltwater ray-finned fish from the family Gadidae, the true cods. It is the only species in the monotypic genus ''Melanogrammus''. It is found in the North Atlantic Ocean and associated seas where ...

, hard cheese (typically Cheddar), and cream. It was created at the Savoy Grill in London for Bennett, who was an ''habitué'',Ayto, John"Arnold Bennett"

''The Diner's Dictionary'', Oxford University Press, 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2020 by the chef

Jean Baptiste Virlogeux

Jean Baptiste Virlogeux (1885–1958) was a French chef. He was the chef at the Savoy Hotel in London during the 1930s and later was the head chef of The Dorchester for 10 years, where he catered to the likes of Prince Philip and Elizabeth II.

Ref ...

. It remains a British classic; cooks from Marcus Wareing to Delia Smith and Gordon Ramsay

Gordon James Ramsay (; born ) is a British chef, restaurateur, television personality and writer. His restaurant group, Gordon Ramsay Restaurants, was founded in 1997 and has been awarded 17 Michelin stars overall; it currently holds a tot ...

have published their recipes for it,. ''Delicious''

"Easy Omelette Arnold Bennett"

, Delia Online; an

"Savoy Grill Arnold Bennett Omelette Recipe"

, Gordon Ramsay Restaurants. All retrieved 3 June 2020

Notes, references and sources

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

*Shapcott, John (2017). ''Arnold Bennett Companion, Vol. II''. Leek, Staffs: Churnet Valley Books. *Squillace, Robert (1997). ''Modernism, Modernity and Arnold Bennett'' (Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press 1997).External links

Works

* * * * *Other

Website of the Arnold Bennett Society

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bennett, Arnold 1867 births 1931 deaths 19th-century British short story writers 19th-century English novelists 20th-century British short story writers 20th-century English diarists 20th-century English dramatists and playwrights 20th-century English novelists 20th-century English screenwriters Alumni of the University of London British propagandists English crime fiction writers English expatriates in France English male dramatists and playwrights English male novelists English opera librettists English self-help writers Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn James Tait Black Memorial Prize recipients People from Hanley, Staffordshire Victorian novelists Deaths from typhoid fever Infectious disease deaths in England Burials in Staffordshire