Arctic coast of Russia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Arctic policy of Russia is the domestic and

The Arctic policy of Russia is the domestic and

On March 12, 1997, Russia ratified the

On March 12, 1997, Russia ratified the

Drifting station North Pole-38 was established in October 2010.

In July 2011 the icebreaker ''Rossiya'' and the research ship ''

Drifting station North Pole-38 was established in October 2010.

In July 2011 the icebreaker ''Rossiya'' and the research ship ''

Russia's economic interests in the Arctic are based on two things - natural resources and maritime transport.

The

Russia's economic interests in the Arctic are based on two things - natural resources and maritime transport.

The

Sanctions Dull Russia's Arctic Shipping Route

" ''The Maritime Executive'', 22 January 2015. Accessed: 23 January 2015. The

ŌĆ£RussiaŌĆÖs Strategy in the Arctic.

ŌĆØ Institute for Strategy, The Royal Danish Defence College. Copenhagen. March 2015. Web. 11 May 2017. In attempting to extract gas and oil in the Arctic region, Gazprom encounter harsh climate and the long lines of communication. So Gazprom requires large investments with high risk and a long investment horizon and is dependent on the energy prices continuing to be high so that the extraction is profitable. International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that the majority of the Arctic fields are not profitable if the world market price of oil is below 120 dollars per barrel. At the time of this writing (May 11, 2017), the price of Brent oil has fallen to around 50 dollars per barrel. Meanwhile, since Russian law only allows for the state energy companies Gazprom (mainly gas) and Rosneft (mainly oil) to extract oil and gas from the continental shelf ŌĆō but since these two firms do not have at their own disposal the necessary technological expertise ŌĆō they have entered into partnerships with a number of foreign firms. The Russian Government is also attempting to increase foreign investment in its Arctic resources. In August 2011

Russian Federation Policy for the Arctic to 2020

Lagutina M. Russian Arctic Policy in the 21st Century:From International to Transnational Cooperation? // Global Review. Winter 2013

* Kharlampieva, N. "The Transnational Arctic and Russia." In Energy Security and Geopolitics in the Arctic: Challenges and Opportunities in the 21st Century, edited by Hooman Peimani. Singapore: World Scientific, 2012

Konyshev, Valery & Sergunin, Alexander. The Arctic at the crossroads of geopolitical interests // Russian Politics and Law, 2012. ŌĆö Vol. 50, ŌĆö Ōä¢ 2. ŌĆö P. 34-54

Konyshev, Valery & Sergunin, Alexander: Is Russia a revisionist military power in the Arctic?

Defense & Security Analysis, September 2014.

Konyshev, Valery & Sergunin, Alexander. Russia in search of its Arctic strategy: between hard and soft power?

Polar Journal, April 2014.

Devyatkin, Pavel. Russia's Arctic Strategy: aimed at conflict or cooperation?

The Arctic Institute, February 2018. {{Energy in Russia

foreign policy

A State (polity), state's foreign policy or external policy (as opposed to internal or domestic policy) is its objectives and activities in relation to its interactions with other states, unions, and other political entities, whether bilaterall ...

of the Russian Federation

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

with respect to the Russian region of the Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

. The Russian region of the Arctic is defined in the "Russian Arctic Policy" as all Russian possessions located north of the Arctic Circle

The Arctic Circle is one of the two polar circles, and the most northerly of the five major circles of latitude as shown on maps of Earth. Its southern equivalent is the Antarctic Circle.

The Arctic Circle marks the southernmost latitude at w ...

. Approximately one-fifth of Russia's landmass is north of the Arctic Circle. Russia is one of five littoral

The littoral zone or nearshore is the part of a sea, lake, or river that is close to the shore. In coastal ecology, the littoral zone includes the intertidal zone extending from the high water mark (which is rarely inundated), to coastal areas ...

states bordering the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

. As of 2010, out of 4 million inhabitants of the Arctic, roughly 2 million lived in arctic Russia, making it the largest arctic country by population. However, in recent years Russia's Arctic population has been declining.

The main goals of Russia in its Arctic policy are to utilize its natural resources, protect its ecosystems

An ecosystem (or ecological system) consists of all the organisms and the physical environment with which they interact. These biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and energy flows. Energy enters the syste ...

, use the seas as a transportation system in Russia's interests, and ensure that it remains a zone of peace and cooperation.

Russia currently maintains a military presence in the Arctic and has plans to improve it, as well as strengthen the Border Guard/Coast Guard presence there. Using the Arctic for economic gain has been done by Russia for centuries for shipping and fishing. Russia has plans to exploit the large offshore resource deposits in the Arctic. The Northern Sea Route

The Northern Sea Route (NSR) (russian: ąĪąĄ╠üą▓ąĄčĆąĮčŗą╣ ą╝ąŠčĆčüą║ąŠ╠üą╣ ą┐čāčéčī, ''Severnyy morskoy put'', shortened to ąĪąĄą▓ą╝ąŠčĆą┐čāčéčī, ''Sevmorput'') is a shipping route officially defined by Russian legislation as lying east of Nov ...

is of particular importance to Russia for transportation, and the Russian Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, and ...

is considering projects for its development. The Security Council also stated a need for increasing investment in Arctic infrastructure.

Russia conducts extensive research in the Arctic region, notably the drifting ice station

A drifting ice station is a temporary or semi-permanent facility built on an ice floe. During the Cold War the Soviet Union and the United States maintained a number of stations in the Arctic Ocean on floes such as Fletcher's Ice Island for rese ...

s and the Arktika 2007

Arktika 2007 (russian: ąĀąŠčüčüąĖą╣čüą║ą░čÅ ą┐ąŠą╗čÅčĆąĮą░čÅ čŹą║čüą┐ąĄą┤ąĖčåąĖčÅ "ąÉčĆą║čéąĖą║ą░-2007") was a 2007 expedition in which Russia performed the first ever crewed descent to the ocean bottom at the North Pole, as part of research rela ...

expedition, which was the first to reach the seabed at the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Mag ...

. The research is partly aimed to back up Russia's territorial claims, specifically those related to Russia's extended continental shelf

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an island ...

in the Arctic Ocean.

History

On October 1, 1987, Soviet General SecretaryMikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 ŌĆō 30 August 2022) was a Soviet politician who served as the 8th and final leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

, delivered the Murmansk Initiative stating six goals of the Soviet Union's Arctic foreign policy: establish a nuclear-free zone in Northern Europe; reduce military activity in the Baltic, Northern, Norwegian and Greenland Seas; cooperate on resource development; form an international conference on Arctic scientific research coordination; cooperate in environmental protection and management; and open the Northern Sea Route.

Geography

The Russian Ministry of Economic Development has identified eight Arctic Support Zones along the Arctic coast of Russia on which funds and projects will be focused, with the aim of fostering the economic potential of theNorthern Sea Route

The Northern Sea Route (NSR) (russian: ąĪąĄ╠üą▓ąĄčĆąĮčŗą╣ ą╝ąŠčĆčüą║ąŠ╠üą╣ ą┐čāčéčī, ''Severnyy morskoy put'', shortened to ąĪąĄą▓ą╝ąŠčĆą┐čāčéčī, ''Sevmorput'') is a shipping route officially defined by Russian legislation as lying east of Nov ...

while ensuring that the Russian presence will not be limited to resource extraction

Extractivism is the process of extracting natural resources from the Earth to sell on the world market. It exists in an economy that depends primarily on the extraction or removal of natural resources that are considered valuable for exportation w ...

.

The eight zones are Kola

KOLA (99.9 FM) is a commercial radio station licensed to Redlands, California, and broadcasting to the Riverside-San Bernardino-Inland Empire radio market. It is owned by the Anaheim Broadcasting Corporation and it airs a classic hits radio form ...

, Arkhangelsk

Arkhangelsk (, ; rus, ąÉčĆčģą░╠üąĮą│ąĄą╗čīčüą║, p=╔Ér╦łxan╔Ī╩▓╔¬l╩▓sk), also known in English as Archangel and Archangelsk, is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. It lies o ...

, Nenets, Vorkuta

Vorkuta (russian: ąÆąŠčĆą║čāčéą░╠ü; kv, ąÆė¦čĆą║čāčéą░, ''V├Črkuta''; Nenets for "the abundance of bears", "bear corner") is a coal-mining town in the Komi Republic, Russia, situated just north of the Arctic Circle in the Pechora coal basin at ...

, Yamal-Nenets, Taimyr-Turukhan, North Yakutia and Chukotka. In the North Yakutia area, the project includes reconstruction of the Tiksi

Tiksi ( rus, ąóąĖ╠üą║čüąĖ, , ╦łt╩▓iks╩▓╔¬; sah, ąóąĖą║čüąĖąĖ, ''Tiksii'' ŌĆō lit. ''a moorage place'') is an urban locality (an urban-type settlement) and the administrative center of Bulunsky District in the Sakha Republic, Russia, located o ...

sea port and the port of Zelenomysky. In the Arkhangelsk zone, this will include the construction of the .

Exploration

The first recorded voyage to the Russian Arctic was by theNovgorod

Veliky Novgorod ( rus, links=no, ąÆąĄą╗ąĖą║ąĖą╣ ąØąŠą▓ą│ąŠčĆąŠą┤, t=Great Newtown, p=v╩▓╔¬╦łl╩▓ik╩▓╔¬j ╦łnov╔Ī╔Ör╔Öt), also known as just Novgorod (), is the largest city and administrative centre of Novgorod Oblast, Russia. It is one of the ol ...

ian Uleb in 1032, in which he discovered the Kara Sea

The Kara Sea (russian: ąÜą░╠üčĆčüą║ąŠąĄ ą╝ąŠ╠üčĆąĄ, ''Karskoye more'') is a marginal sea, separated from the Barents Sea to the west by the Kara Strait and Novaya Zemlya, and from the Laptev Sea to the east by the Severnaya Zemlya archipelago. ...

. From the 11th to the 16th centuries, Russian coastal dwellers of the White Sea

The White Sea (russian: ąæąĄą╗ąŠąĄ ą╝ąŠčĆąĄ, ''B├®loye m├│re''; Karelian and fi, Vienanmeri, lit. Dvina Sea; yrk, ąĪčŹčĆą░ą║ąŠ čÅą╝╩╝, ''Serako yam'') is a southern inlet of the Barents Sea located on the northwest coast of Russia. It is su ...

, or pomors

Pomors or Pomory ( rus, ą┐ąŠą╝ąŠ╠üčĆčŗ, p=p╔É╦łmor╔©, ''seasiders'') are an ethnographic group descended from Russian settlers, primarily from Veliky Novgorod, living on the White Sea coasts and the territory whose southern border lies on a wa ...

, gradually explored other parts of the Arctic coastline, going as far as the Ob and Yenisey

The Yenisey (russian: ąĢąĮąĖčüąĄ╠üą╣, ''Yenis├®y''; mn, ąōąŠčĆą╗ąŠą│ ą╝ė®čĆė®ąĮ, ''Gorlog m├Čr├Čn''; Buryat: ąōąŠčĆą╗ąŠą│ ą╝ę»čĆ菹Į, ''Gorlog m├╝ren''; Tuvan: ąŻą╗čāą│-ąźąĄą╝, ''Ulu─¤-Hem''; Khakas: ąÜąĖą╝ čüčāęō, ''Kim su─¤''; Ket: ėāčāą║ ...

rivers, establishing trading posts in Mangazeya

Mangazeya (russian: ą£ą░ąĮą│ą░ąĘąĄ╠üčÅ) was a Northwest Siberian trans-Ural trade colony and later city in the 17th century. Founded in 1600 by Cossacks from Tobolsk, it was situated on the Taz River, between the lower courses of the Ob and Yen ...

. Continuing the search of fur

Fur is a thick growth of hair that covers the skin of mammals. It consists of a combination of oily guard hair on top and thick underfur beneath. The guard hair keeps moisture from reaching the skin; the underfur acts as an insulating blanket t ...

s and walrus

The walrus (''Odobenus rosmarus'') is a large pinniped, flippered marine mammal with a discontinuous distribution about the North Pole in the Arctic Ocean and subarctic seas of the Northern Hemisphere. The walrus is the only living species in ...

and mammoth

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus'', one of the many genera that make up the order of trunked mammals called proboscideans. The various species of mammoth were commonly equipped with long, curved tusks and, ...

ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mammals is ...

, the Siberian Cossacks

Siberian Cossacks were Cossacks who settled in the Siberian region of Russia from the end of the 16th century, following Yermak Timofeyevich's Russian conquest of Siberia, conquest of Siberia. In early periods, practically the whole Russian popula ...

under Mikhail Stadukhin

Mikhail Vasilyevich Stadukhin (russian: ą£ąĖčģą░ąĖą╗ ąÆą░čüąĖą╗čīąĄą▓ąĖčć ąĪčéą░ą┤čāčģąĖąĮ) (died 1666) was a Russian explorer of far northeast Siberia, one of the first to reach the Kolyma, Anadyr, Penzhina and Gizhiga Rivers and the northern Se ...

reached the Kolyma River

The Kolyma ( rus, ąÜąŠą╗čŗą╝ą░, p=k╔Öl╔©╦łma; sah, ąźą░ą╗čŗą╝ą░, translit=Khalyma) is a river in northeastern Siberia, whose basin covers parts of the Sakha Republic, Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, and Magadan Oblast of Russia.

The Kolyma is frozen ...

by 1644. Ivan Moskvitin discovered the Sea of Okhotsk

The Sea of Okhotsk ( rus, ą×čģąŠ╠üčéčüą║ąŠąĄ ą╝ąŠ╠üčĆąĄ, Oh├│tskoye m├│re ; ja, Ńé¬ŃāøŃā╝ŃāäŃ黵ĄĘ, Oh┼Źtsuku-kai) is a marginal sea of the western Pacific Ocean. It is located between Russia's Kamchatka Peninsula on the east, the Kuril Islands ...

in 1639 and Fedot Alekseyev Popov

Fedot Alekseyevich Popov (russian: ążąĄą┤ąŠčé ąÉą╗ąĄą║čüąĄąĄą▓ąĖčć ą¤ąŠą┐ąŠą▓, also Fedot Alekseyev, russian: ążąĄą┤ąŠčé ąÉą╗ąĄą║čüąĄąĄą▓; nickname Kholmogorian, russian: ąźąŠą╗ą╝ąŠą│ąŠčĆąĄčå, for his place of birth (Kholmogory, Arkhangelsk Oblast ...

and Semyon Dezhnyov

Semyon Ivanovich Dezhnyov ( rus, ąĪąĄą╝čæąĮ ąśą▓ą░╠üąĮąŠą▓ąĖčć ąöąĄąČąĮčæą▓, p=s╩▓╔¬╦łm╩▓╔Ąn ╔¬╦łvan╔Öv╩▓╔¬t╔Ģ d╩▓╔¬╦ł╩Én╩▓╔Ąf; sometimes spelled Dezhnyov; c. 1605 ŌĆō 1673) was a Russian explorer of Siberia and the first European to sail through t ...

discovered the Bering Strait in 1648, with Dezhnyov establishing a permanent Russian settlement near the present day Anadyr Anadyr may refer to:

*Anadyr (town), a town and the administrative center of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia

*Anadyr District

*Anadyr Estuary

*Anadyr (river), a river in Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia

*Anadyr Highlands

*Anadyr Lowlands

*Operati ...

.

After Peter I Peter I may refer to:

Religious hierarchs

* Saint Peter (c. 1 AD ŌĆō c. 64ŌĆō88 AD), a.k.a. Simon Peter, Simeon, or Simon, apostle of Jesus

* Pope Peter I of Alexandria (died 311), revered as a saint

* Peter I of Armenia (died 1058), Catholico ...

took the throne, Russia began to develop a navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval warfare, naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral zone, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and ...

and use it to continue its Arctic exploration. Vitus Bering

Vitus Jonassen Bering (baptised 5 August 1681 ŌĆō 19 December 1741),All dates are here given in the Julian calendar, which was in use throughout Russia at the time. also known as Ivan Ivanovich Bering, was a Danish cartographer and explorer in ...

explored Kamchatka

The Kamchatka Peninsula (russian: ą┐ąŠą╗čāąŠčüčéčĆąŠą▓ ąÜą░ą╝čćą░čéą║ą░, Poluostrov Kamchatka, ) is a peninsula in the Russian Far East, with an area of about . The Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Okhotsk make up the peninsula's eastern and wes ...

in 1728, while Bering's aides Ivan Fyodorov and Mikhail Gvozdev

Mikhail Spiridonovich Gvozdev (russian: ą£ąĖčģą░ąĖ╠üą╗ ąĪą┐ąĖčĆąĖą┤ąŠ╠üąĮąŠą▓ąĖčć ąōą▓ąŠ╠üąĘą┤ąĄą▓; ŌĆō after 1759) was a Russian military geodesist and a commander of the expedition to northern Alaska in 1732, when the Alaskan shore was sighte ...

discovered Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: ąÉą╗čÅčüą║ą░, Alyaska; ale, Alax╠ésxax╠é; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, An├Īaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., ...

in 1732. The Great Northern Expedition

The Great Northern Expedition (russian: ąÆąĄą╗ąĖą║ą░čÅ ąĪąĄą▓ąĄčĆąĮą░čÅ čŹą║čüą┐ąĄą┤ąĖčåąĖčÅ) or Second Kamchatka Expedition (russian: ąÆč鹊čĆą░čÅ ąÜą░ą╝čćą░čéčüą║ą░čÅ čŹą║čüą┐ąĄą┤ąĖčåąĖčÅ) was one of the largest exploration enterprises in hi ...

, which lasted from 1733 to 1743, was one of the largest exploration enterprises in history, organized and led by Vitus Bering

Vitus Jonassen Bering (baptised 5 August 1681 ŌĆō 19 December 1741),All dates are here given in the Julian calendar, which was in use throughout Russia at the time. also known as Ivan Ivanovich Bering, was a Danish cartographer and explorer in ...

, Aleksei Chirikov

Aleksei Ilyich Chirikov (russian: ąÉą╗ąĄą║čüąĄ╠üą╣ ąśą╗čīąĖ╠üčć ą¦ąĖ╠üčĆąĖą║ąŠą▓; 1703 ŌĆō November 14, 1748) was a Russian navigator and captain who, along with Vitus Bering, was the first Russian to reach the northwest coast of North America. H ...

and a number of other major explorers. A party of the expedition personally led by Bering and Chirikov discovered southern Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: ąÉą╗čÅčüą║ą░, Alyaska; ale, Alax╠ésxax╠é; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, An├Īaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., ...

, the Aleutian Islands

The Aleutian Islands (; ; ale, Unangam Tanangin,ŌĆØLand of the Aleuts", possibly from Chukchi language, Chukchi ''aliat'', "island"), also called the Aleut Islands or Aleutic Islands and known before 1867 as the Catherine Archipelago, are a cha ...

and the Commander Islands

The Commander Islands, Komandorski Islands, or Komandorskie Islands (russian: ąÜąŠą╝ą░ąĮą┤ąŠ╠üčĆčüą║ąĖąĄ ąŠčüčéčĆąŠą▓ą░╠ü, ''Komandorskiye ostrova'') are a series of treeless, sparsely populated Russian islands in the Bering Sea located about ea ...

,

while the parties led by Stepan Malygin

Stepan Gavrilovich Malygin () (unknown-1 August 1764) was a Russian Arctic explorer.

Malygin studied at the Moscow School of Mathematics and Navigation from 1711 to 1717. After his graduation, Malygin began his career as a naval cadet and was ...

, Dmitry Ovtsyn

Dmitry Leontiyevich Ovtsyn () (unknown - after 1757) was a Russian hydrographer and Arctic explorer. The Ovtsyn family is one of the oldest Russian noble families, originating from the descendants of Rurik, the Murom princes.

Ovtsyn's biography ...

, Fyodor Minin, Semyon Chelyuskin

Semyon Ivanovich Chelyuskin (; c. 1700 ŌĆō 1764) was a Russian polar explorer and naval officer.

Chelyuskin graduated from the Navigation School in Moscow. He first became a deputy navigator while serving in the Baltic Fleet (1726) and later pr ...

, Vasily Pronchischev, Khariton Laptev

Khariton Prokofievich Laptev (russian: ąźą░čĆąĖč鹊ąĮ ą¤čĆąŠą║ąŠčäčīąĄą▓ąĖčć ąøą░ą┐č鹥ą▓) (1700ŌĆō1763) was a Russian naval officer and Arctic explorer.

Khariton Laptev was born in a gentry family in the village of Pokarevo near Velikiye Luki (in ...

and Dmitry Laptev

Dmitry Yakovlevich Laptev (russian: ąöą╝ąĖčéčĆąĖą╣ ą»ą║ąŠą▓ą╗ąĄą▓ąĖčć ąøą░ą┐č鹥ą▓) (1701 - ) was a Russian Arctic explorer and Vice Admiral (1762). The Dmitry Laptev Strait is named in his honor and the Laptev Sea is named in honor of him and ...

mapped most of the Arctic coastline of Russia (from the White Sea in Europe to the mouth of Kolyma River in Asia). The expedition resulted in 62 large maps and charts of the Arctic region.

Territorial claims

Modern Russian territorial claims to the Arctic officially date back to April 15, 1926, when the Soviet Union claimed land between 32┬░04'35"E and 168┬░49'30"W. However, this claim specifically only applied toislands

An island (or isle) is an isolated piece of habitat that is surrounded by a dramatically different habitat, such as water. Very small islands such as emergent land features on atolls can be called islets, skerries, cays or keys. An island ...

and lands within this region. The first maritime boundary between Russia and Norway, from the Varangerfjord

The Varangerfjord ( en, Varanger Fjord; russian: ąÆą░čĆą░ąĮą│ąĄčĆ-čäčīąŠčĆą┤, ąÆą░čĆčÅąČčüą║ąĖą╣ ąĘą░ą╗ąĖą▓; fi, Varanginvuono; sme, V├Īrjavuonna) is the easternmost fjord in Norway, north of Finland. The fjord is located in Troms og Finnmark co ...

, was signed in 1957. However, tensions resurfaced after both countries made continental shelf claims in the 1960s.

Informal talks began in the 1970s about determining a boundary in the Barents Sea to settle differing claims, as Russia wanted the boundary to be a line running straight north from the mainland, more than what it had. On September 15, 2010, Foreign Ministers Jonas Gahr St├Ėre

Jonas Gahr St├Ėre (; born 25 August 1960) is a Norwegian politician who has served as the prime minister of Norway since 2021 and has been Leader of the Labour Party since 2014. He served under Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg as Minister of For ...

and Sergei Lavrov

Sergey Viktorovich Lavrov (russian: ąĪąĄčĆą│ąĄą╣ ąÆąĖą║č鹊čĆąŠą▓ąĖčć ąøą░ą▓čĆąŠą▓, ; born 21 March 1950) is a Russian diplomat and politician who has served as the Foreign Minister of Russia since 2004.

Lavrov served as the Permanent Represe ...

, of Norway and Russia respectively, signed a treaty that effectively divided the disputed territory in half between the two countries, and also agreed to co-manage resources in that region where they overlap national sectors.

The two countries had already been co-managing fisheries

Fishery can mean either the enterprise of raising or harvesting fish and other aquatic life; or more commonly, the site where such enterprise takes place ( a.k.a. fishing ground). Commercial fisheries include wild fisheries and fish farms, both ...

in the Barents since the 1978 Grey Zone Agreement, which has been renewed annually since it was signed.

On March 12, 1997, Russia ratified the

On March 12, 1997, Russia ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), also called the Law of the Sea Convention or the Law of the Sea Treaty, is an international agreement that establishes a legal framework for all marine and maritime activities. , 167 c ...

(UNCLOS), which allowed countries to make claims to extended continental shelves

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an island ...

.

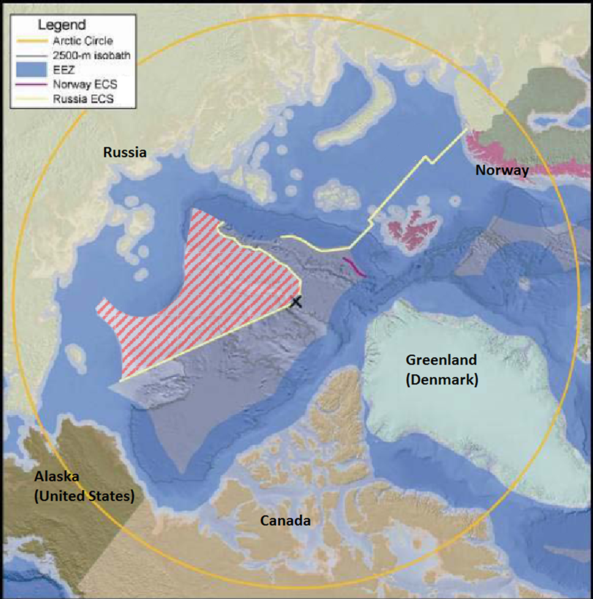

In accordance with UNCLOS, Russia submitted a claim to an extended continental shelf

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an island ...

beyond its 200-mile (320 km) exclusive economic zone on December 20, 2001, to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), also called the Law of the Sea Convention or the Law of the Sea Treaty, is an international agreement that establishes a legal framework for all marine and maritime activities. , 167 c ...

(CLCS). Russia claimed that two underwater mountain chains - the Lomonosov

Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov (; russian: ą£ąĖčģą░ąĖą╗ (ą£ąĖčģą░ą╣ą╗ąŠ) ąÆą░čüąĖą╗čīąĄą▓ąĖčć ąøąŠą╝ąŠąĮąŠčüąŠą▓, p=m╩▓╔¬x╔É╦łil v╔É╦łs╩▓il╩▓j╔¬v╩▓╔¬t╔Ģ , a=Ru-Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov.ogg; ŌĆō ) was a Russian Empire, Russian polymath, s ...

and Mendeleev

Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev (sometimes transliterated as Mendeleyev or Mendeleef) ( ; russian: links=no, ąöą╝ąĖčéčĆąĖą╣ ąśą▓ą░ąĮąŠą▓ąĖčć ą£ąĄąĮą┤ąĄą╗ąĄąĄą▓, tr. , ; 8 February Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._27_January.html" ;"title="O ...

ridges - within the Russian sector of the Arctic were extensions of the Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelago a ...

n continent and thus part of the Russian continental shelf. The UN CLCS neither validated nor invalidated the claim but requested Russia to submit additional data to substantiate its claim.

Russia planned to submit additional data to the CLCS in 2012.

In August 2007, a Russian expedition named Arktika 2007

Arktika 2007 (russian: ąĀąŠčüčüąĖą╣čüą║ą░čÅ ą┐ąŠą╗čÅčĆąĮą░čÅ čŹą║čüą┐ąĄą┤ąĖčåąĖčÅ "ąÉčĆą║čéąĖą║ą░-2007") was a 2007 expedition in which Russia performed the first ever crewed descent to the ocean bottom at the North Pole, as part of research rela ...

, led by Artur Chilingarov

Artur Nikolayevich Chilingarov (russian: ąÉčĆčéčāčĆ ąØąĖą║ąŠą╗ą░ąĄą▓ąĖčć ą¦ąĖą╗ąĖąĮą│ą░čĆąŠą▓; born 25 September 1939) is an Armenian-Russian polar explorer. He is a corresponding member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, he was awarded the t ...

, planted a Russian flag on the seabed at the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Mag ...

.

This was done in the course of scientific research to substantiate Russia's 2001 extended continental shelf claim submission. Rock, mud, water, and plant samples at the seabed were collected and brought back to Russia for scientific study. The Natural Resources Ministry of Russia announced that the bottom samples collected from the expedition are similar to those found on continental shelves. Russia is using this to substantiate its claim that the Lomonosov Ridge in its sector is a continuation of the continental shelf that extends from Russia, and that Russia has a legitimate claim to that seabed.

The United States and Canada dismissed the flag planting as purely symbolic and legally meaningless.

Russia's Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov

Sergey Viktorovich Lavrov (russian: ąĪąĄčĆą│ąĄą╣ ąÆąĖą║č鹊čĆąŠą▓ąĖčć ąøą░ą▓čĆąŠą▓, ; born 21 March 1950) is a Russian diplomat and politician who has served as the Minister of Foreign Affairs (Russia), Foreign Minister of Russia since 2004.

...

agreed, telling reporters: "The aim of this expedition is not to stake Russia's claim but to show that our shelf reaches to the North Pole." He also confirmed that Arctic territory issues "can be tackled solely on the basis of international law, the International Convention on the Law of the Sea and in the framework of the mechanisms that have in accordance with it been created for determining the borders of states which have a continental shelf." In another interview Sergey Lavrov said: "I was amazed by my Canadian counterpartŌĆÖs statement that we are planting flags around. WeŌĆÖre not throwing flags around. We just do what other discoverers did. The purpose of the expedition is not to stake whatever rights of Russia, but to prove that our shelf extends to the North Pole. By the way the flag on the Moon, it was the same".

Foreign Ministers and other officials representing Canada, Denmark, Norway, Russia, and the United States met in Ilulissat, Greenland

Ilulissat, formerly Jakobshavn or Jacobshaven, is the municipal seat and largest town of the Avannaata municipalities of Greenland, municipality in western Greenland, located approximately north of the Arctic Circle. With the population of 4,6 ...

in May 2008, at the Arctic Ocean Conference

The inaugural Arctic Ocean Conference was held in Ilulissat (Greenland) on 27-29 May 2008. Canada, Denmark, Norway, Russia and the United States discussed key issues relating to the Arctic Ocean.Office The meeting was significant because of its pl ...

and announced the Ilulissat Declaration. Among other things the declaration stated that any demarcation issues in the Arctic should be resolved on a bilateral basis between contesting parties.

An example of such bilateral agreement was achieved between Russia and Norway in 2010.

Military

Part of Russia's current Arctic policy includes maintaining a military presence in the region. In 2014, theNorthern Fleet Joint Strategic Command (Russia)

The Northern Fleet Joint Strategic Command (russian: ą×ą▒čŖąĄą┤ąĖąĮčæąĮąĮąŠąĄ čüčéčĆą░č鹥ą│ąĖč湥čüą║ąŠąĄ ą║ąŠą╝ą░ąĮą┤ąŠą▓ą░ąĮąĖąĄ ┬½ąĪąĄą▓ąĄčĆąĮčŗą╣ čäą╗ąŠčé┬╗), is one of the five military districts of the Russian Armed Forces, with its jur ...

was established. The Russian Northern Fleet

Severnyy flot

, image = Great emblem of the Northern Fleet.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Northern Fleet's great emblem

, start_date = June 1, 1733; Sov ...

, the largest of the four Russian Navy fleets, is headquartered in Severomorsk

Severomorsk (russian: ąĪąĄą▓ąĄčĆąŠą╝ąŠ╠üčĆčüą║), known as Vayenga () until April 18, 1951, is a closed town in Murmansk Oblast, Russia. Severomorsk is the main administrative base of the Russian Northern Fleet. The town is located on the coast ...

, in the Kola Gulf on the Barents Sea.

The Northern Fleet encompasses two-thirds of Russia's total naval power, and has close to 80 operational ships. As of 2013, this included approximately 35 submarines, six missile cruisers, and the flagship '' Petr Velikiy'' (Peter the Great), a nuclear-powered guided missile cruiser. In 2012 the Russian Navy resumed naval patrols of the Northern Sea Route, marked by a 2,000 mile patrol of the Russian Arctic by ten ships led by an icebreaker and the ''Petr Velikiy''.

The Russian Military

The Armed Forces of the Russian Federation (, ), commonly referred to as the Russian Armed Forces, are the military forces of Russia. In terms of active-duty personnel, they are the world's fifth-largest military force, with at least two m ...

also reportedly announced in June 2008 that it would increase the operational radius of its Northern Fleet

Severnyy flot

, image = Great emblem of the Northern Fleet.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Northern Fleet's great emblem

, start_date = June 1, 1733; Sov ...

submarines.

The first nuclear icebreaker

A nuclear-powered icebreaker is an icebreaker with an Nuclear marine propulsion, onboard nuclear power plant that produces power for the vessel's propulsion system. , Russia is the only country that builds and operates nuclear-powered icebreakers ...

, the ''Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 ŌĆō 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

'', began operating in the Northern Sea Route in July 1960. A total of ten nuclear-powered civilian vessels, including nine icebreaker

An icebreaker is a special-purpose ship or boat designed to move and navigate through ice-covered waters, and provide safe waterways for other boats and ships. Although the term usually refers to ice-breaking ships, it may also refer to smaller ...

s, have been built in Russia. Three of these have been decommissioned, including the ''Lenin''.

Besides its six nuclear icebreakers, Russia also has 19 diesel polar icebreakers.

Its nuclear icebreaker fleet includes the ''50 Let Pobedy

''50 Let Pobedy'' (russian: 50 ą╗ąĄčé ą¤ąŠą▒ąĄą┤čŗ; "50 Years of Victory", referring to the anniversary of victory of the Soviet Union in World War II) is a Russian nuclear-powered icebreaker.

History

Construction on project no. 10521 started ...

'' (50 Years of Victory), the largest nuclear icebreaker in the world. There are currently plans to build six more icebreakers, as well as plans to build a $33 billion year-round Arctic port.

On September 28, 2011, President Medvedev lifted the ban on the privatization

Privatization (also privatisation in British English) can mean several different things, most commonly referring to moving something from the public sector into the private sector. It is also sometimes used as a synonym for deregulation when ...

of the nuclear icebreaker fleet with decree No. 1256. This repeal will allow Atomflot

FSUE Atomflot (russian: ążąōąŻą¤ ┬½ąÉč鹊ą╝čäą╗ąŠčé┬╗) is a Russian company and service base that maintains the world's only fleet of nuclear-powered icebreakers. Atomflot is part of the Rosatom group, and is based in the city of Murmansk.

, the ...

, the state company

A state-owned enterprise (SOE) is a Government, government entity which is established or nationalised by the ''national government'' or ''provincial government'' by an executive order or an act of legislation in order to earn Profit (econom ...

that owns the fleet, to be at least partially owned by private investors. The government is expected to retain a controlling share in the company.

Russia says that it has military units specifically trained for Arctic combat. On October 4, 2010, Russian Navy commander Admiral Vladimir Vysotsky

Vladimir Semyonovich Vysotsky ( rus, links=no, ąÆą╗ą░ą┤ąĖą╝ąĖčĆ ąĪąĄą╝čæąĮąŠą▓ąĖčć ąÆčŗčüąŠčåą║ąĖą╣, p=vl╔É╦łd╩▓im╩▓╔¬r s╩▓╔¬╦łm╩▓╔Ąn╔Öv╩▓╔¬t╔Ģ v╔©╦łsotsk╩▓╔¬j; 25 January 1938 ŌĆō 25 July 1980), was a Soviet singer-songwriter, poet, and actor ...

was quoted as saying: "We are observing the penetration of a host of states which . . . are advancing their interests very intensively, in every possible way, in particular China," and that Russia would "not give up a single inch" in the Arctic.

Russian Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov announced plans on July 16, 2011, for the creation of two brigades that would be stationed in the Arctic.

Russia's Arctic policy statement, approved by President Medvedev on September 18, 2008, called for the establishment of improved military forces in the Arctic to "ensure military security" in that region, as well as the strengthening of existing border guards

A border guard of a country is a national security agency that performs border security. Some of the national border guard agencies also perform coast guard (as in Germany, Italy or Ukraine) and rescue service duties.

Name and uniform

In diff ...

in the area.

Research

Russia has conducted research in the Arctic for decades. The country is the only one that uses drift stations- research facilities seasonally deployed ondrift ice

Drift ice, also called brash ice, is sea ice that is not attached to the shoreline or any other fixed object (shoals, grounded icebergs, etc.).Lepp├żranta, M. 2011. The Drift of Sea Ice. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. Unlike fast ice, which is "fasten ...

- and also has other research stations in its Arctic zone. The first drift station, North Pole-1

North Pole-1 (russian: ąĪąĄą▓ąĄčĆąĮčŗą╣ ą┐ąŠą╗čÄčü-1) was the world's first Soviet manned drifting station in the Arctic Ocean, primarily used for research.

North Pole-1 was established on 21 May 1937 and officially opened on 6 June, some from ...

, was established on May 21, 1937, by the Soviet Union. Russian research has focused on the Arctic seabed, marine life, meteorology, exploration, and natural resources, among other topics. Recent research has also been focusing on studying the Lomonosov Ridge to collect evidence that could strengthen Russian territorial claims to the seabed in that region within the Russian sector of the Arctic.

Drifting station North Pole-38 was established in October 2010.

In July 2011 the icebreaker ''Rossiya'' and the research ship ''

Drifting station North Pole-38 was established in October 2010.

In July 2011 the icebreaker ''Rossiya'' and the research ship ''Akademik Fyodorov

RV ''Akademik Fedorov'' (russian: ąÉą║ą░ą┤ąĄą╝ąĖą║ ążčæą┤ąŠčĆąŠą▓) is a Russian scientific diesel-electric research vessel, the flagship of the Russian polar research fleet. It was built in Rauma, Finland for the Soviet Union and completed on ...

'' began conducting seismic studies north of Franz Josef Land

, native_name =

, image_name = Map of Franz Josef Land-en.svg

, image_caption = Map of Franz Josef Land

, image_size =

, map_image = Franz Josef Land location-en.svg

, map_caption = Location of Franz Josef ...

to find evidence to back up Russia's territorial claims in the Arctic. The ''Akademik Fyodorov'' and the icebreaker '' Yamal'' went on a similar mission the year before.

The Lena-2011 expedition, a joint Russian-German project headed by J├Črn Thiede

J├Črn is a locality situated in Skellefte├ź Municipality, V├żsterbotten County, Sweden with 797 inhabitants in 2010. Vladimir Lenin made his last stop in Sweden at the railway station

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means ...

, left for the Laptev Sea

The Laptev Sea ( rus, ą╝ąŠ╠üčĆąĄ ąøą░╠üą┐č鹥ą▓čŗčģ, r=more Laptevykh; sah, ąøą░ą┐č鹥ą▓čéą░čĆ ą▒ą░ą╣ęĢą░ą╗ą╗ą░čĆą░, translit=Laptevtar baß╗╣─¤allara) is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. It is located between the northern coast of Siberia, th ...

and the Lena River

The Lena (russian: ąøąĄ╠üąĮą░, ; evn, ąĢą╗čÄąĄąĮčŹ, ''Eljune''; sah, ė©ą╗ę»ė®ąĮčŹ, ''├¢l├╝├Čne''; bua, ąŚę»ą╗čģčŹ, ''Z├╝lkhe''; mn, ąŚę»ą╗ą│čŹ, ''Z├╝lge'') is the easternmost of the three great Siberian rivers that flow into the Arctic Ocean ...

in the summer of 2011. It was to study Siberian climate and climate change, as well as gather information about the Russian continental shelf.

The head of the expedition, who is also the chairman of the European Arctic Commission, expressed confidence that Russia will gather the evidence needed to confirm its claim to additional parts of the Arctic shelf.

In 2011, research stations under construction included one on Samoylovsky Island, which was planned to be completed by mid-2012 and will focus on researching shelf zone permafrost

Permafrost is ground that continuously remains below 0 ┬░C (32 ┬░F) for two or more years, located on land or under the ocean. Most common in the Northern Hemisphere, around 15% of the Northern Hemisphere or 11% of the global surface ...

,

and one on the Svalbard Islands

Svalbard ( , ), also known as Spitsbergen, or Spitzbergen, is a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. North of mainland Europe, it is about midway between the northern coast of Norway and the North Pole. The islands of the group range ...

, which was anticipated to be finished in 2013 and will focus on geophysical, hydrological, and geological research.

Over the summer of 2015, Russia built a large Federal Security Service (Russ. FSB) Border Guard base on Alexandra Land

Alexandra Land (russian: ąŚąĄą╝ą╗čÅ ąÉą╗ąĄą║čüą░ąĮą┤čĆčŗ, ''Zemlya Aleksandry'') is a large island located in Franz Josef Land, Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russian Federation. Not counting detached and far-lying Victoria Island, it is the westernmost i ...

island of the Franz Joseph Land archipelago, expanding on an already established airbase called Nagurskoye

Nagurskoye (russian: ąØą░ą│čā╠üčĆčüą║ąŠąĄ; also written as Nagurskoye, or Nagurskaja) is an airfield in Alexandra Land in Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia located north of Murmansk. It is an extremely remote Arctic base and Russia's northernmost mi ...

, above the 80th parallel. The new complex is made of multiple inter-connected buildings and can house a company of 150 soldiers for up to 18 months without the need of re-supply.

Economy

Russia's economic interests in the Arctic are based on two things - natural resources and maritime transport.

The

Russia's economic interests in the Arctic are based on two things - natural resources and maritime transport.

The Northern Sea Route

The Northern Sea Route (NSR) (russian: ąĪąĄ╠üą▓ąĄčĆąĮčŗą╣ ą╝ąŠčĆčüą║ąŠ╠üą╣ ą┐čāčéčī, ''Severnyy morskoy put'', shortened to ąĪąĄą▓ą╝ąŠčĆą┐čāčéčī, ''Sevmorput'') is a shipping route officially defined by Russian legislation as lying east of Nov ...

, in use for centuries and officially defined by Russian legislation, is an Arctic shipping

Freight transport, also referred as ''Freight Forwarding'', is the physical process of transporting Commodity, commodities and merchandise goods and cargo. The term shipping originally referred to transport by sea but in American English, it h ...

lane that stretches from the Barents Sea to the Bering Strait through Arctic waters. Travel along Northern Sea Route takes only one-third the distance needed to go through the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, ┘é┘Ä┘å┘Äž¦ž®┘Å ┘▒┘äž│┘Å┘æ┘ł┘Ä┘Ŗ┘Æž│┘É, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

, without as high a risk of pirates

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

.

The route is currently open for up to eight weeks a year, and studies are predicting that climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warmingŌĆöthe ongoing increase in global average temperatureŌĆöand its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to E ...

will lead to further reduction in Arctic ice, which can lead to greater use of the route.

Even when "open" this route is not totally ice free and requires Russian icebreaker and navigational support to ensure safety of passage. Currently of goods are transported along the Northern Sea Route every year. Traffic through the Route is expected to increase tenfold by 2020, and six tankers have already gone through in 2010. The Russian government estimates that annual cargo traffic could reach 85 million metric tons,

and shipping along the Route could account for a quarter of cargo between Europe and Asia by 2030.

However, using the Northern Sea Route extensively will require vast expansion of Russia's current infrastructure in the Arctic, especially ports

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Ham ...

and naval vessels

A naval ship is a military ship (or sometimes boat, depending on classification) used by a navy. Naval ships are differentiated from civilian ships by construction and purpose. Generally, naval ships are damage resilient and armed with w ...

. In August 2011 Nikolai Patrushev

Nikolai Platonovich Patrushev (russian: ąØąĖą║ąŠą╗ą░╠üą╣ ą¤ą╗ą░č鹊╠üąĮąŠą▓ąĖčć ą¤ą░╠üčéčĆčāčłąĄą▓; born 11 July 1951) is a Russian politician, security officer and intelligence officer who has served as the secretary of the Security Council of ...

, Secretary of Russia's Security Council, stated that the poor condition of infrastructure in the Arctic hinders development there, reducing the attractiveness of the region's resources for development. The infrastructure is worse in the eastern part of Russia, which also contains more resources. Recent economic sanctions imposed on Russia have additionally weakened the NSR's viability for foreign investors and in 2014 the overall number of voyages across the passage has fallen dramatically from 71 to 53.Sanctions Dull Russia's Arctic Shipping Route

" ''The Maritime Executive'', 22 January 2015. Accessed: 23 January 2015. The

Yamal Peninsula

The Yamal Peninsula (russian: ą┐ąŠą╗čāąŠčüčéčĆąŠą▓ ą»ą╝ą░ą╗, poluostrov Yamal) is located in the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug of northwest Siberia, Russia. It extends roughly 700 km (435 mi) and is bordered principally by the Kara ...

, home to Russia's biggest natural gas reserves, was connected to the rest of Russia by Gazprom

PJSC Gazprom ( rus, ąōą░ąĘą┐čĆąŠą╝, , ╔Ī╔Éz╦łprom) is a Russian majority state-owned multinational energy corporation headquartered in the Lakhta Center in Saint Petersburg. As of 2019, with sales over $120 billion, it was ranked as the larges ...

through the creation of the ObskayaŌĆōBovanenkovo Line

The ObskayaŌĆōBovanenkovo Line is a railway line in northern Russia, built and owned and operated by Gazprom. It was opened for traffic in 2010 and was built for the gas fields around Bovanenkovo on the Yamal Peninsula, the Yamal project. In Fe ...

, which opened in 2010. This was part of Gazprom's Yamal project

Yamal project, also referred to as Yamal megaproject, is a long-term plan to exploit and bring to the markets the vast natural gas reserves in the Yamal Peninsula, Russia. Administratively, the project is located in the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Ok ...

to develop natural gas resources in the Yamal Peninsula. Russian Railways

Russian Railways (russian: link=no, ą×ąÉą× ┬½ąĀąŠčüčüąĖą╣čüą║ąĖąĄ ąČąĄą╗ąĄąĘąĮčŗąĄ ą┤ąŠčĆąŠą│ąĖ┬╗ (ą×ąÉą× ┬½ąĀą¢ąö┬╗), OAO Rossiyskie zheleznye dorogi (OAO RZhD)) is a Russian fully state-owned vertically integrated railway company, both manag ...

plans to connect Indiga, which is being considered as a prime location for the construction of a deepwater port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Ham ...

, and Amderma

Amderma (russian: ąÉą╝ą┤ąĄčĆą╝ą░, lit. ''a walrus rookery'' in Nenets) is a rural locality (a settlement) in Zapolyarny District of Nenets Autonomous Okrug, Russia, located on the coast of Kara Sea, near the Vaygach Island, from Naryan-Mar, t ...

, site of the Amderma Airport

Amderma Airport is a former interceptor base in Arctic Russia, near Novaya Zemlya, located 4 km west of Amderma (ąÉą╝ą┤ąĄčĆą╝ą░). It is a simple airfield built on a spit along the ocean, with some tarmac space.

The facility's prime purpos ...

, to its railway system by 2030. Prime Minister Putin also announced that a year-round port would be constructed on the Yamal Peninsula

The Yamal Peninsula (russian: ą┐ąŠą╗čāąŠčüčéčĆąŠą▓ ą»ą╝ą░ą╗, poluostrov Yamal) is located in the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug of northwest Siberia, Russia. It extends roughly 700 km (435 mi) and is bordered principally by the Kara ...

.

But so far, Russia's concentration on production of oil and gas on the Yamal Peninsula met with huge challenges.

Staun, J├ĖrgenŌĆ£RussiaŌĆÖs Strategy in the Arctic.

ŌĆØ Institute for Strategy, The Royal Danish Defence College. Copenhagen. March 2015. Web. 11 May 2017. In attempting to extract gas and oil in the Arctic region, Gazprom encounter harsh climate and the long lines of communication. So Gazprom requires large investments with high risk and a long investment horizon and is dependent on the energy prices continuing to be high so that the extraction is profitable. International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that the majority of the Arctic fields are not profitable if the world market price of oil is below 120 dollars per barrel. At the time of this writing (May 11, 2017), the price of Brent oil has fallen to around 50 dollars per barrel. Meanwhile, since Russian law only allows for the state energy companies Gazprom (mainly gas) and Rosneft (mainly oil) to extract oil and gas from the continental shelf ŌĆō but since these two firms do not have at their own disposal the necessary technological expertise ŌĆō they have entered into partnerships with a number of foreign firms. The Russian Government is also attempting to increase foreign investment in its Arctic resources. In August 2011

Rosneft

PJSC Rosneft Oil Company ( stylized as ROSNEFT) is a Russian Vertical integration, integrated energy company headquartered in Moscow. Rosneft specializes in the exploration, Extraction of petroleum, extraction, production, refining, Petroleum t ...

, a Russian government-operated oil company, signed a deal with ExxonMobil

ExxonMobil Corporation (commonly shortened to Exxon) is an American multinational oil and gas corporation headquartered in Irving, Texas. It is the largest direct descendant of John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil, and was formed on November 30, ...

in which Rosneft received some of Exxon's global oil assets in exchange for the joint development of Russian Arctic resources by both companies.

This agreement includes a $3.2 billion hydrocarbon exploration

Hydrocarbon exploration (or oil and gas exploration) is the search by petroleum geologists and geophysicists for deposits of hydrocarbons, particularly petroleum and natural gas, in the Earth using petroleum geology.

Exploration methods

Vis ...

of the Kara and Black seas (although the Black Sea is not in the Arctic),

as well as the joint development of ice-resistant drilling platforms and other Arctic technologies. This deal followed a failed attempt at a similar cooperation between Rosneft and BP in May. Chevron

Chevron (often relating to V-shaped patterns) may refer to:

Science and technology

* Chevron (aerospace), sawtooth patterns on some jet engines

* Chevron (anatomy), a bone

* ''Eulithis testata'', a moth

* Chevron (geology), a fold in rock lay ...

is currently in talks with Rosneft about jointly developing Arctic resources.

Russia is the only country in the world planning to use floating nuclear power plants. The ''Akademik Lomonosov

''Akademik Lomonosov'' (russian: ąÉą║ą░ą┤ąĄą╝ąĖą║ ąøąŠą╝ąŠąĮąŠčüąŠą▓) is a non-self-propelled power barge that operates as the first Russian floating nuclear power station. The ship was named after Russian Academy of Sciences, academician Mikhai ...

'', expected to go into operation in 2012, will be one of eight plants that will provide power to Russian coastal cities. There are plans for these plants to also provide power to large gas rig

A drilling rig is an integrated system that drills wells, such as oil or water wells, or holes for piling and other construction purposes, into the earth's subsurface. Drilling rigs can be massive structures housing equipment used to drill wat ...

s in the Arctic Ocean in the future.

The Prirazlomnoye field

Prirazlomnoye field is an Arctic offshore oilfield located in the Pechora Sea, south of Novaya Zemlya, Russia, the first commercial offshore oil development in the Russian Arctic sector. The field development is based on the single stationary P ...

, an offshore oilfield in the Pechora Sea

Pechora Sea (russian: link=no, ą¤ąĄč湊╠üčĆčüą║ąŠąĄ ą╝ąŠ╠üčĆąĄ, or Pechorskoye More), is a sea at the northwest of Russia, the southeastern part of the Barents Sea

The Barents Sea ( , also ; no, Barentshavet, ; russian: ąæą░čĆąĄąĮčåąĄą▓ąŠ ...

that will include up to 40 wells, is currently under construction and drilling is expected to start in early 2012. It will be the world's first ice-resistant oil platform

An oil platform (or oil rig, offshore platform, oil production platform, and similar terms) is a large structure with facilities to extract and process petroleum and natural gas that lie in rock formations beneath the seabed. Many oil platfor ...

and will also be the first offshore Arctic platform.

Russia wants to establish its Arctic possessions as a major resource base by 2020. As climate change makes the Arctic areas more accessible, Russia, along with other countries, is looking to use the Arctic to increase its energy resource production.

According to the U.S. Geological Survey, there are of oil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturated ...

and of natural gas

Natural gas (also called fossil gas or simply gas) is a naturally occurring mixture of gaseous hydrocarbons consisting primarily of methane in addition to various smaller amounts of other higher alkanes. Low levels of trace gases like carbo ...

north of the Arctic Circle.

Overall, about 10% of the world's petroleum resources are estimated to be in the Arctic. The dominant portion of offshore Arctic hydrocarbon (oil and gas), as reflected in the USGS studies, is located within the current uncontested Exclusive Economic Zones of the five nations bordering the Arctic.

In September 2013, Gazprom's oil drilling activities in the Arctic have drawn protests from environmental groups particularly Greenpeace. Greenpeace has opposed oil drilling in the Arctic on the grounds that oil drilling would cause damage to the Arctic ecosystem and that there are no safety plans in place to prevent oil spills.

On September 18, the Greenpeace vessel ''MV Arctic Sunrise

''Arctic Sunrise'' is an ice-strengthened vessel operated by Greenpeace. The vessel was built in Norway in 1975 and has a gross tonnage of 949, a length of and a maximum speed of . She is classified by Det Norske Veritas as a "1A1 icebreaker" (t ...

'' staged a protest and attempted to board Gazprom's Prirazlomnaya platform. In response, the Russian Coast Guard

The Coast Guard of the Border Service of the FSB (russian: ąæąĄčĆąĄą│ąŠą▓ą░čÅ ąŠčģčĆą░ąĮą░ ą¤ąŠą│čĆą░ąĮąĖčćąĮąŠą╣ čüą╗čāąČą▒čŗ ążąĪąæ ąĀąŠčüčüąĖąĖ, Beregovaya okhrana Pogranichnoy sluzhby FSB Rossii), previously known as the Maritime Units of the ...

seized control of the ship, and arrested the activists. Phil Radford

Philip David Radford (born January 2, 1976) is an American activist who served as the executive director of Greenpeace USA. He is the founder and President of Progressive Power Lab, an organization that incubates companies and non-profits that bu ...

, executive director of Greenpeace USA, stated that the arrest of the Arctic 30 is the stiffest response that Greenpeace

Greenpeace is an independent global campaigning network, founded in Canada in 1971 by Irving Stowe and Dorothy Stowe, immigrant environmental activists from the United States. Greenpeace states its goal is to "ensure the ability of the Earth t ...

has encountered from a government since the bombing of the Rainbow Warrior in 1985 by the "action" branch of the French foreign intelligence services, the Direction g├®n├®rale de la s├®curit├® ext├®rieure (DGSE).

Earlier in August 2012, Greenpeace had also staged similar protests against the same oil rig.

The Russian government has intended to charge the Greenpeace activists with piracy, which carries a maximum penalty of fifteen years of imprisonment. Thirty members of the crew of "Arctic Sunrise" have been detained for 48 hours by authorities in Murmansk. The crew members come from 19 countries. Several members were arrested after having assaulted the Prirazlomnaya drill rig in the Pechora Sea.Interfax-AVN Moscow Online (English) 0825 GMT 25 September 2013

See also

*Arctic Cooperation and Politics

Arctic cooperation and politics are partially coordinated via the Arctic Council, composed of the eight Arctic nations: the United States, Canada, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Russia, and Denmark with Greenland and the Faroe Islands. The domi ...

*Arctic Council

The Arctic Council is a high-level intergovernmental forum that addresses issues faced by the Arctic governments and the indigenous people of the Arctic. At present, eight countries exercise sovereignty over the lands within the Arctic Circle, ...

* Arctic five

*Extreme North (Russia)

The Extreme North or Far North (russian: ąÜčĆą░ą╣ąĮąĖą╣ ąĪąĄą▓ąĄčĆ, ąöą░ą╗čīąĮąĖą╣ ąĪąĄą▓ąĄčĆ) is a large part of Russia located mainly north of the Arctic Circle and boasting enormous mineral and natural resources. Its total area is about , ...

*Continental shelf of Russia

The continental shelf of Russia (also called the Russian continental shelf or the Arctic shelf in the Arctic region) is a continental shelf adjacent to the Russian Federation. Geologically, the extent of the shelf is defined as the entirety of the ...

*Chief Directorate of the Northern Sea Route

The Chief Directorate of the Northern Sea Route (russian: ąōą╗ą░ą▓ąĮąŠąĄ ąŻą┐čĆą░ą▓ą╗ąĄąĮąĖąĄ ąĪąĄą▓ąĄčĆąĮąŠą│ąŠ ą£ąŠčĆčüą║ąŠą│ąŠ ą¤čāčéąĖ , translit=Glavnoe upravlenie Severnogo morskogo puti), also known as Glavsevmorput or GUSMP (russian: ąōąŻą ...

*Greenpeace Arctic Sunrise ship case

On 18 September 2013, Greenpeace activists attempted to scale the Prirazlomnaya drilling platform, as part of a protest against Arctic oil production.

The following day, on 19 September 2013, Russian authorities seized the Greenpeace ship the '' ...

References

External links

Russian Federation Policy for the Arctic to 2020

Literature

Lagutina M. Russian Arctic Policy in the 21st Century:From International to Transnational Cooperation? // Global Review. Winter 2013

* Kharlampieva, N. "The Transnational Arctic and Russia." In Energy Security and Geopolitics in the Arctic: Challenges and Opportunities in the 21st Century, edited by Hooman Peimani. Singapore: World Scientific, 2012

Konyshev, Valery & Sergunin, Alexander. The Arctic at the crossroads of geopolitical interests // Russian Politics and Law, 2012. ŌĆö Vol. 50, ŌĆö Ōä¢ 2. ŌĆö P. 34-54

Konyshev, Valery & Sergunin, Alexander: Is Russia a revisionist military power in the Arctic?

Defense & Security Analysis, September 2014.

Konyshev, Valery & Sergunin, Alexander. Russia in search of its Arctic strategy: between hard and soft power?

Polar Journal, April 2014.

Devyatkin, Pavel. Russia's Arctic Strategy: aimed at conflict or cooperation?

The Arctic Institute, February 2018. {{Energy in Russia

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

Foreign relations of Russia

International relations

Politics of Russia