Archelon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

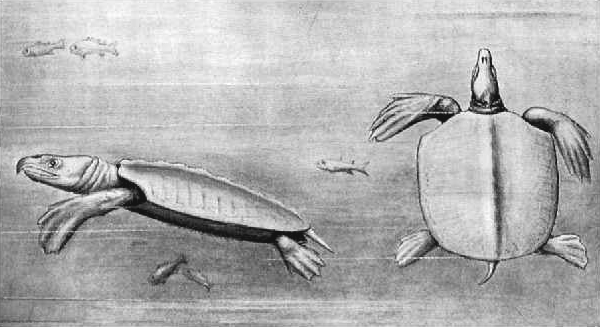

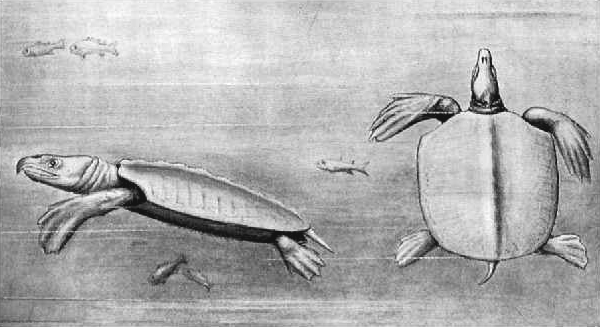

''Archelon'' is an extinct marine turtle from the

The

The  In 1900, Wieland described a second species, ''A. marshii'', from remains collected in 1898 by American paleontologist

In 1900, Wieland described a second species, ''A. marshii'', from remains collected in 1898 by American paleontologist

The

The

The holotype measures from head to tail, with the head measuring , the

The holotype measures from head to tail, with the head measuring , the  Five neck vertebrae were recovered from the holotype, and it probably had eight in total in life; they are X-shaped, procoelous–concave on the side towards the head and convex on the other–and their thick frame indicates strong neck muscles. Ten thoracic vertebrae were found, increasing in size until the sixth then rapidly decreasing, and they have little connection with the carapace. The three vertebrae of the sacrum are short and flat. It probably had eighteen tail vertebrae; the first eight to ten (probably in the same area as the carapace) had neural arches, whereas the remaining did not. Its tail likely had a wide range of mobility, and the tail is thought to have been able to bend at nearly a 90° angle horizontally.

Five neck vertebrae were recovered from the holotype, and it probably had eight in total in life; they are X-shaped, procoelous–concave on the side towards the head and convex on the other–and their thick frame indicates strong neck muscles. Ten thoracic vertebrae were found, increasing in size until the sixth then rapidly decreasing, and they have little connection with the carapace. The three vertebrae of the sacrum are short and flat. It probably had eighteen tail vertebrae; the first eight to ten (probably in the same area as the carapace) had neural arches, whereas the remaining did not. Its tail likely had a wide range of mobility, and the tail is thought to have been able to bend at nearly a 90° angle horizontally.

The humeri in the upper arms are proportionally massive, and the

The humeri in the upper arms are proportionally massive, and the

The neuralia and pleuralia form highly irregular and finger-like sutures where they meet, and one plate may have lain over the other plate while the bone was still developing and malleable. The neuralia and pleuralia–the bony portions of the carapace–are particularly thin, and the ribs, especially the first rib, and the

The neuralia and pleuralia form highly irregular and finger-like sutures where they meet, and one plate may have lain over the other plate while the bone was still developing and malleable. The neuralia and pleuralia–the bony portions of the carapace–are particularly thin, and the ribs, especially the first rib, and the

A turtle plastron, the underside, comprises, from head-most to tail-most, the epiplastron, the entoplastron, which is small and wedged in between the former and the hyoplastron, then, following, the hypoplastron, and finally the xiphiplastron. The plastron, as a whole, is thick, and measures, in a specimen described in 1898, in length. Unlike the carapace, it features striations throughout.

In protostegids, the epiplastron and entoplastron are fused together, forming a single unit called an "entepiplastron" or a "paraplastron." This entepiplastron is T-shaped, as opposed to the Y-shaped entoplastrons in other turtles. The top edge of the T rounds off except at the center which features a small projection. The outward side is slightly convex and bends somewhat away from the body. The two ends of the T flatten out, getting broader and thinner as they get farther from the center.

A thick, continuous ridge connects the hyoplastron, hypoplastron, and xiphiplastron. The hyoplastron features a large number of spines projecting around the circumference. The hyoplastron is slightly elliptical, and grows thinner as it gets farther from the center before the spines erupt. The spines grow thick and narrow towards their middle portion. The 7 to 9 spines projecting towards the head are short and triangular. The 6 middle spines are long and thin. The last 19 spines are flat. There are no marks indicating contact with the entepiplastron. The hypoplastron is similar to the hyoplastron, except it has more spines, a total of 54. The xiphiplastron is boomerang-shaped, a primitive characteristic in contrast to the straight ones seen in more modern turtles.

A turtle plastron, the underside, comprises, from head-most to tail-most, the epiplastron, the entoplastron, which is small and wedged in between the former and the hyoplastron, then, following, the hypoplastron, and finally the xiphiplastron. The plastron, as a whole, is thick, and measures, in a specimen described in 1898, in length. Unlike the carapace, it features striations throughout.

In protostegids, the epiplastron and entoplastron are fused together, forming a single unit called an "entepiplastron" or a "paraplastron." This entepiplastron is T-shaped, as opposed to the Y-shaped entoplastrons in other turtles. The top edge of the T rounds off except at the center which features a small projection. The outward side is slightly convex and bends somewhat away from the body. The two ends of the T flatten out, getting broader and thinner as they get farther from the center.

A thick, continuous ridge connects the hyoplastron, hypoplastron, and xiphiplastron. The hyoplastron features a large number of spines projecting around the circumference. The hyoplastron is slightly elliptical, and grows thinner as it gets farther from the center before the spines erupt. The spines grow thick and narrow towards their middle portion. The 7 to 9 spines projecting towards the head are short and triangular. The 6 middle spines are long and thin. The last 19 spines are flat. There are no marks indicating contact with the entepiplastron. The hypoplastron is similar to the hyoplastron, except it has more spines, a total of 54. The xiphiplastron is boomerang-shaped, a primitive characteristic in contrast to the straight ones seen in more modern turtles.

''Archelon'' probably had weaker arms, and thus less swimming power, than the leatherback sea turtle, and so did not frequent the open ocean as much, preferring shallower, calmer waters. This is indicated by the similarity of the humerus/arm and hand/arm ratios of it and cheloniids, which are known to have poor development of the limbs into flippers and a preference for shallow water. Conversely, the large flipper-to-carapace ratio of protostegids and the similarly large flipper spread, like that of the predatory cheloniid

''Archelon'' probably had weaker arms, and thus less swimming power, than the leatherback sea turtle, and so did not frequent the open ocean as much, preferring shallower, calmer waters. This is indicated by the similarity of the humerus/arm and hand/arm ratios of it and cheloniids, which are known to have poor development of the limbs into flippers and a preference for shallow water. Conversely, the large flipper-to-carapace ratio of protostegids and the similarly large flipper spread, like that of the predatory cheloniid

''Archelon'' inhabited the shallow

''Archelon'' inhabited the shallow

Oceans of Kansas Paleontology

{{Testudines Protostegidae Late Cretaceous turtles of North America Fossil taxa described in 1896 Prehistoric turtle genera Extinct turtles Monotypic prehistoric reptile genera

Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the younger of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''creta'', the ...

, and is the largest turtle ever to have been documented, with the biggest specimen measuring from head to tail and in body mass. It is known only from the Dakota Pierre Shale

The Pierre Shale is a geologic formation or series in the Upper Cretaceous which occurs east of the Rocky Mountains in the Great Plains, from Pembina Valley in Canada to New Mexico.

The Pierre Shale was described by Meek and Hayden in 1862 in th ...

and has one species, ''A. ischyros''. In the past, the genus also contained ''A. marshii'' and ''A. copei'', though these have been reassigned to '' Protostega'' and ''Microstega'', respectively. The genus was named in 1895 by American paleontologist George Reber Wieland based on a skeleton from South Dakota, who placed it into the extinct family

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its ...

Protostegidae

Protostegidae is a family of extinct marine turtles that lived during the Cretaceous period. The family includes some of the largest sea turtles that ever existed. The largest, '' Archelon'', had a head long. Like most sea turtles, they had fl ...

. The leatherback sea turtle

The leatherback sea turtle (''Dermochelys coriacea''), sometimes called the lute turtle or leathery turtle or simply the luth, is the largest of all living turtles and the heaviest non-crocodilian reptile, reaching lengths of up to and weights ...

(''Dermochelys coriacea'') was once thought to be its closest living relative, but now, Protostegidae is thought to be a completely separate lineage from any living sea turtle

Sea turtles (superfamily Chelonioidea), sometimes called marine turtles, are reptiles of the order Testudines and of the suborder Cryptodira. The seven existing species of sea turtles are the flatback, green, hawksbill, leatherback, loggerhead, ...

.

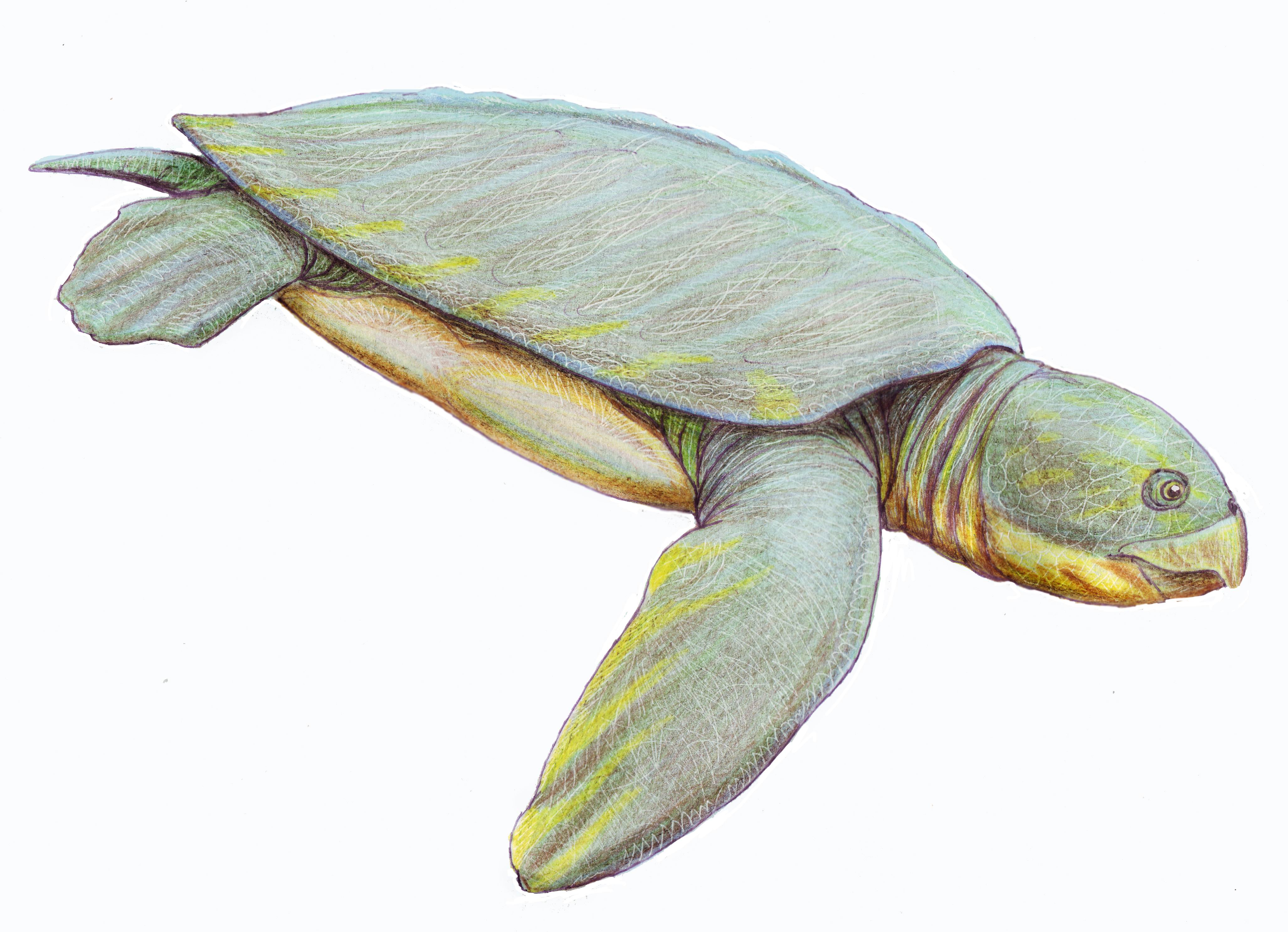

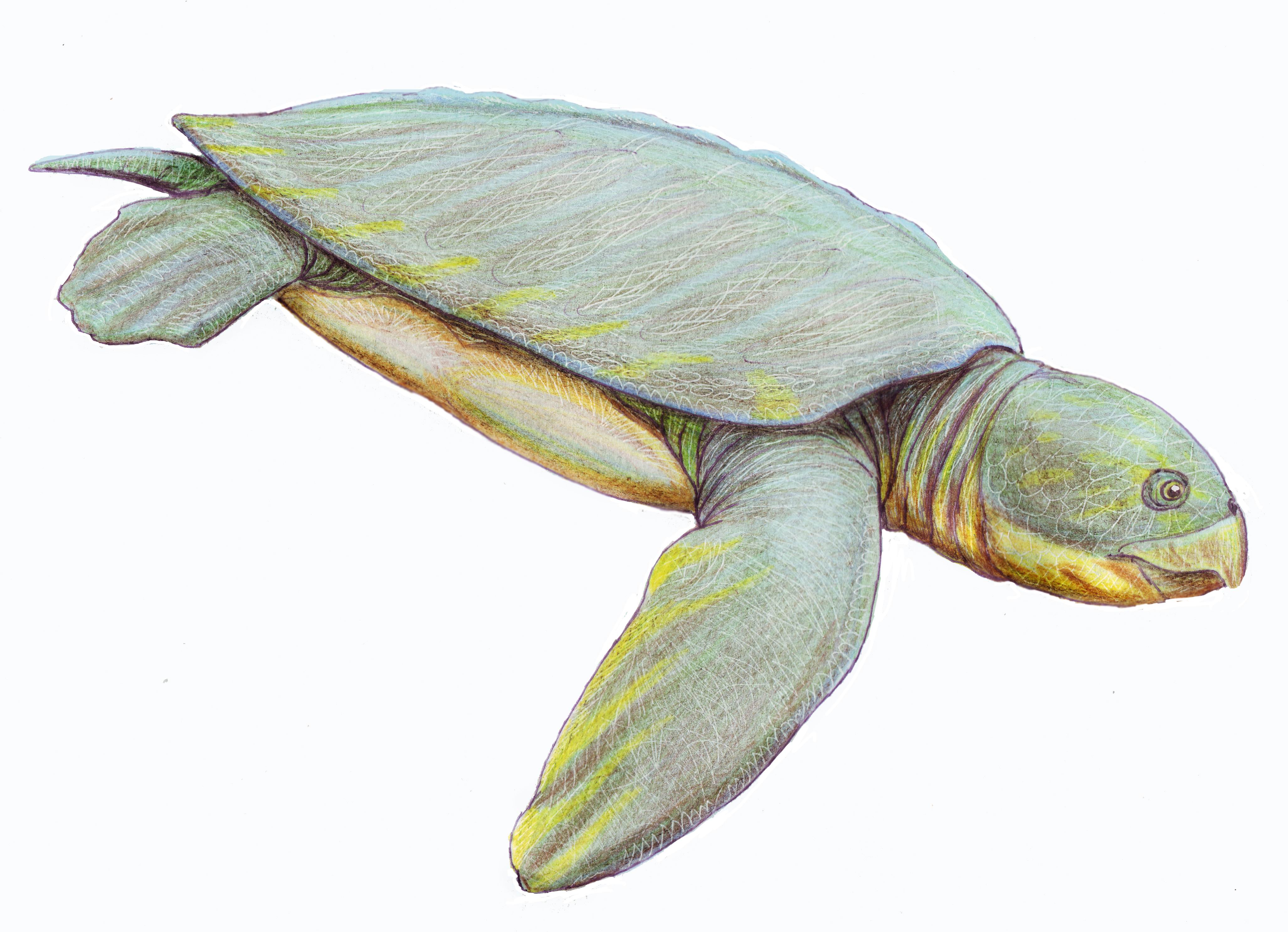

''Archelon'' had a leathery carapace

A carapace is a Dorsum (biology), dorsal (upper) section of the exoskeleton or shell in a number of animal groups, including arthropods, such as crustaceans and arachnids, as well as vertebrates, such as turtles and tortoises. In turtles and tor ...

instead of the hard shell seen in sea turtles. The carapace may have featured a row of small ridges, each peaking at in height. It had an especially hooked beak and its jaws were adept at crushing, so it probably ate hard-shelled crustacea

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean gro ...

ns and mollusk

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is e ...

s while slowly moving over the seafloor. However, its beak may have been adapted for shearing

Sheep shearing is the process by which the woollen fleece of a sheep is cut off. The person who removes the sheep's wool is called a '' shearer''. Typically each adult sheep is shorn once each year (a sheep may be said to have been "shorn" or ...

flesh, and ''Archelon'' was likely able to produce powerful strokes necessary for open-ocean travel. It inhabited the northern Western Interior Seaway

The Western Interior Seaway (also called the Cretaceous Seaway, the Niobraran Sea, the North American Inland Sea, and the Western Interior Sea) was a large inland sea that split the continent of North America into two landmasses. The ancient sea, ...

, a mild to cool area dominated by plesiosaur

The Plesiosauria (; Greek: πλησίος, ''plesios'', meaning "near to" and ''sauros'', meaning "lizard") or plesiosaurs are an order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared ...

s, hesperornithiform seabirds, and mosasaur

Mosasaurs (from Latin ''Mosa'' meaning the 'Meuse', and Greek ' meaning 'lizard') comprise a group of extinct, large marine reptiles from the Late Cretaceous. Their first fossil remains were discovered in a limestone quarry at Maastricht on th ...

s. It may have gone extinct due to the shrinking of the seaway, increased egg and hatchling predation, and cooling climate.

Taxonomy

Research history

The

The holotype specimen

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of several ...

, YPM 3000, was collected from the Late Campanian

The Campanian is the fifth of six ages of the Late Cretaceous Epoch on the geologic timescale of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS). In chronostratigraphy, it is the fifth of six stages in the Upper Cretaceous Series. Campanian ...

-age Pierre Shale

The Pierre Shale is a geologic formation or series in the Upper Cretaceous which occurs east of the Rocky Mountains in the Great Plains, from Pembina Valley in Canada to New Mexico.

The Pierre Shale was described by Meek and Hayden in 1862 in th ...

of South Dakota along the Cheyenne River

The Cheyenne River ( lkt, Wakpá Wašté; "Good River"), also written ''Chyone'', referring to the Cheyenne people who once lived there, is a tributary of the Missouri River in the U.S. states of Wyoming and South Dakota. It is approximately 2 ...

in Custer County by American paleontologist George Reber Wieland in 1895, and described by him the following year based on a mostly complete skeleton excluding the skull. He named it ''Archelon ischyros'', genus name from the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

- (-) 'first/early', () 'turtle', and species name from () 'mighty' or 'powerful'. Wieland placed it into the family

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its ...

''Protostegidae

Protostegidae is a family of extinct marine turtles that lived during the Cretaceous period. The family includes some of the largest sea turtles that ever existed. The largest, '' Archelon'', had a head long. Like most sea turtles, they had fl ...

'', which included at the time the smaller '' Protostega'' and ''Protosphargis

''Protosphargis'' is an extinct genus of sea turtle from the Upper Cretaceous of Italy. It was first named by Capellini in 1884.

Sources

''Protosphargis''at the Paleobiology Database

The Paleobiology Database is an online resource for infor ...

''. The latter is now in the family Cheloniidae

Cheloniidae is a family of typically large marine turtles that are characterised by their common traits such as, having a flat streamlined wide and rounded shell and almost paddle-like flippers for their forelimbs. They are the only sea turtles t ...

. A second specimen, a skull, was discovered in 1897 in the same region.

In 1900, Wieland described a second species, ''A. marshii'', from remains collected in 1898 by American paleontologist

In 1900, Wieland described a second species, ''A. marshii'', from remains collected in 1898 by American paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh

Othniel Charles Marsh (October 29, 1831 – March 18, 1899) was an American professor of Paleontology in Yale College and President of the National Academy of Sciences. He was one of the preeminent scientists in the field of paleontology. Among h ...

, to whom the species name

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

refers, on the basis that the shell underside ( plastron) was thicker and the humeri

The humerus (; ) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extremity consists of a round ...

were straighter. However, in 1909, Wieland reclassified it as ''Protostega marshii''. In 1902, a third, mostly complete specimen was collected also along the Cheyenne River. In 1953, Swiss paleontologist Rainer Zangerl split Protostegidae into two families: Chelospharginae and Protosteginae; to the former was assigned '' Chelosphargis'' and ''Calcarichelys'', and the latter ''Archelon'' and ''Protostega''. In the same study, the Kansas ''Protostega copei'', which was first described by Wieland in 1909 and named in honor of Edward Drinker Cope

Edward Drinker Cope (July 28, 1840 – April 12, 1897) was an American zoologist, paleontologist, comparative anatomist, herpetologist, and ichthyologist. Born to a wealthy Quaker family, Cope distinguished himself as a child prodigy interested ...

who first erected the family Protostegidae, was moved to the genus ''Archelon'' as ''A. copei''. In 1998, ''A. copei'' was moved to the new genus ''Microstega'' as ''M. copei''. In 1992, a fourth and the largest specimen to date, nicknamed "Brigitta", was discovered in Oglala Lakota County, South Dakota

Oglala Lakota County (known as Shannon County until May 2015) is a county in southwestern South Dakota, United States. The population was 13,672 at the 2020 census. Oglala Lakota County does not have a functioning county seat; Hot Springs in ne ...

and resides in the Natural History Museum Vienna.

In 2002, a fifth specimen, a partial skeleton, was discovered from the Pierre Shale of North Dakota along the Sheyenne River

The Sheyenne River is one of the major tributaries of the Red River of the North, meandering U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed June 8, 2011 across eastern North Dakota, Uni ...

near Cooperstown

Cooperstown is a village in and county seat of Otsego County, New York, United States. Most of the village lies within the town of Otsego, but some of the eastern part is in the town of Middlefield. Located at the foot of Otsego Lake in the C ...

.

Evolution

The

The sister group

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and t ...

of Protostegidae has, in the past, been considered to be Dermochelyidae

Dermochelyidae is a family of turtles which has seven extinct genera and one extant genus, including the largest living sea turtles.

Classification of known genera

The following list of dermochelyid species was published by Hirayama and Tong in ...

, and thus their closest living relative would have been the dermochelyid leatherback sea turtle

The leatherback sea turtle (''Dermochelys coriacea''), sometimes called the lute turtle or leathery turtle or simply the luth, is the largest of all living turtles and the heaviest non-crocodilian reptile, reaching lengths of up to and weights ...

(''Dermochelys coriacea''). However, phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

studies conclude that protostegids represent a completely separate, ancient ( basal) lineage that originated in the Late Jurassic

The Late Jurassic is the third epoch of the Jurassic Period, and it spans the geologic time from 163.5 ± 1.0 to 145.0 ± 0.8 million years ago (Ma), which is preserved in Upper Jurassic strata.Owen 1987.

In European lithostratigraphy, the name ...

, removing the family from the superfamily

SUPERFAMILY is a database and search platform of structural and functional annotation for all proteins and genomes. It classifies amino acid sequences into known structural domains, especially into SCOP superfamilies. Domains are functional, str ...

Chelonioidea

Sea turtles (superfamily Chelonioidea), sometimes called marine turtles, are reptiles of the order Testudines and of the suborder Cryptodira. The seven existing species of sea turtles are the flatback, green, hawksbill, leatherback, loggerhead, ...

which includes all sea turtles. In this model, ''Archelon'' does not share a marine ancestor with any sea turtle.

Description

The holotype measures from head to tail, with the head measuring , the

The holotype measures from head to tail, with the head measuring , the neck

The neck is the part of the body on many vertebrates that connects the head with the torso. The neck supports the weight of the head and protects the nerves that carry sensory and motor information from the brain down to the rest of the body. In ...

, the thoracic vertebra

In vertebrates, thoracic vertebrae compose the middle segment of the vertebral column, between the cervical vertebrae and the lumbar vertebrae. In humans, there are twelve thoracic vertebrae and they are intermediate in size between the cervical ...

e , the sacrum

The sacrum (plural: ''sacra'' or ''sacrums''), in human anatomy, is a large, triangular bone at the base of the spine that forms by the fusing of the sacral vertebrae (S1S5) between ages 18 and 30.

The sacrum situates at the upper, back part ...

, and the tail

The tail is the section at the rear end of certain kinds of animals’ bodies; in general, the term refers to a distinct, flexible appendage to the torso. It is the part of the body that corresponds roughly to the sacrum and coccyx in mammals, r ...

. The largest specimen, Brigitta, measures around from head to tail and from flipper to flipper, and, in life, weighed around . Skulls of ''Archelon'' measured at up to .

''Archelon'' had a distinctly elongated and narrow head. It had a defined hooked beak which was probably covered in a sheath in life, reminiscent of the beaks of birds of prey

Birds of prey or predatory birds, also known as raptors, are hypercarnivorous bird species that actively hunt and feed on other vertebrates (mainly mammals, reptiles and other smaller birds). In addition to speed and strength, these predators ...

. However, in the back, the cutting edge of the beak is dull compared to sea turtles. Much of the length of the head derives from the elongated premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammal has b ...

e–which is the front part of the beak in this animal–and maxilla

The maxilla (plural: ''maxillae'' ) in vertebrates is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The t ...

e. The jugal bone

The jugal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians and birds. In mammals, the jugal is often called the malar or zygomatic. It is connected to the quadratojugal and maxilla, as well as other bones, which may vary by species.

Anato ...

s, the cheek bones, due to the elongate head, do not project as far as they do in other turtles. The nostrils are elongated and rest on the top of the skull, slightly posited forward, and are unusually horizontal compared to sea turtles. The jugal bone

The jugal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians and birds. In mammals, the jugal is often called the malar or zygomatic. It is connected to the quadratojugal and maxilla, as well as other bones, which may vary by species.

Anato ...

s (cheekbones) are rounded as opposed to triangular in sea turtles. The articular bone

The articular bone is part of the lower jaw of most vertebrates, including most jawed fish, amphibians, birds and various kinds of reptiles, as well as ancestral mammals.

Anatomy

In most vertebrates, the articular bone is connected to two ...

, which formed the jaw joint, was probably heavily encased in cartilage

Cartilage is a resilient and smooth type of connective tissue. In tetrapods, it covers and protects the ends of long bones at the joints as articular cartilage, and is a structural component of many body parts including the rib cage, the neck an ...

. The jaw probably moved in a hammering motion.

Five neck vertebrae were recovered from the holotype, and it probably had eight in total in life; they are X-shaped, procoelous–concave on the side towards the head and convex on the other–and their thick frame indicates strong neck muscles. Ten thoracic vertebrae were found, increasing in size until the sixth then rapidly decreasing, and they have little connection with the carapace. The three vertebrae of the sacrum are short and flat. It probably had eighteen tail vertebrae; the first eight to ten (probably in the same area as the carapace) had neural arches, whereas the remaining did not. Its tail likely had a wide range of mobility, and the tail is thought to have been able to bend at nearly a 90° angle horizontally.

Five neck vertebrae were recovered from the holotype, and it probably had eight in total in life; they are X-shaped, procoelous–concave on the side towards the head and convex on the other–and their thick frame indicates strong neck muscles. Ten thoracic vertebrae were found, increasing in size until the sixth then rapidly decreasing, and they have little connection with the carapace. The three vertebrae of the sacrum are short and flat. It probably had eighteen tail vertebrae; the first eight to ten (probably in the same area as the carapace) had neural arches, whereas the remaining did not. Its tail likely had a wide range of mobility, and the tail is thought to have been able to bend at nearly a 90° angle horizontally.

The humeri in the upper arms are proportionally massive, and the

The humeri in the upper arms are proportionally massive, and the radii

In classical geometry, a radius ( : radii) of a circle or sphere is any of the line segments from its center to its perimeter, and in more modern usage, it is also their length. The name comes from the latin ''radius'', meaning ray but also the ...

and ulna

The ulna (''pl''. ulnae or ulnas) is a long bone found in the forearm that stretches from the elbow to the smallest finger, and when in anatomical position, is found on the medial side of the forearm. That is, the ulna is on the same side of t ...

e of the forearms are short and compact, indicating the animal had strong flippers in life. The flippers would have had a spread of between , though most likely the more conservative estimate. Stretch marks on the limb bones indicate fast growth, with similarities to the leatherback sea turtle, the fastest growing turtle known, whose juveniles have an average growth rate of per year.

Carapace

The carapace comprises on either side eight neuralia–the plates closest to the midline–and nine pleuralia–the plates that connect the midline to the ribs. The plates of the carapace are mostly uniform in dimensions, with the exception of the two pairs of plates corresponding to the eighth thoracic vertebra which are smaller than the others, and the pygal plate closest to the tail which is larger. ''Archelon'' has ten pairs of ribs, and, like the leatherback sea turtle but unlike other sea turtles, the first rib does not meet the first pleural. As in sea turtles, the first rib is noticeably shorter than the second, in this case, three quarters of the length. The second to fifth ribs project at a right angle from the midline, and, in the holotype, each measure in length. A rib increases in thickness in the vertical directiondistal

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position pro ...

ly, as it gets farther from the midline, and the ribs are relatively larger and more well-developed than those of sea turtles. The second to fifth ribs, in the holotype, originate with a thickness of and terminate with around in thickness.

The neuralia and pleuralia form highly irregular and finger-like sutures where they meet, and one plate may have lain over the other plate while the bone was still developing and malleable. The neuralia and pleuralia–the bony portions of the carapace–are particularly thin, and the ribs, especially the first rib, and the

The neuralia and pleuralia form highly irregular and finger-like sutures where they meet, and one plate may have lain over the other plate while the bone was still developing and malleable. The neuralia and pleuralia–the bony portions of the carapace–are particularly thin, and the ribs, especially the first rib, and the shoulder girdle

The shoulder girdle or pectoral girdle is the set of bones in the appendicular skeleton which connects to the arm on each side. In humans it consists of the clavicle and scapula; in those species with three bones in the shoulder, it consists of t ...

are unusually heavy and may have had to carry extra stress

Stress may refer to:

Science and medicine

* Stress (biology), an organism's response to a stressor such as an environmental condition

* Stress (linguistics), relative emphasis or prominence given to a syllable in a word, or to a word in a phrase ...

to compensate, a condition seen in ancient ancestral turtles. ''Archelon'' has osteosclerotic structures, where the bone is dense and heavy, which probably served as ballast

Ballast is material that is used to provide stability to a vehicle or structure. Ballast, other than cargo, may be placed in a vehicle, often a ship or the gondola of a balloon or airship, to provide stability. A compartment within a boat, ship, ...

s in life similar to the limb bones of whales and other open-ocean animals.

The carapace, in life, probably featured a row of ridges along the midline over the chest

The thorax or chest is a part of the anatomy of humans, mammals, and other tetrapod animals located between the neck and the abdomen. In insects, crustaceans, and the extinct trilobites, the thorax is one of the three main divisions of the crea ...

region, perhaps totaling in seven ridges, with each ridge peaking at either . In the absence of firmly jointed neck and pleural plates, the skin over the carapace was probably thick, strong, and leathery in order to compensate and properly support the shoulder girdle. This leathery carapace is also seen in the leatherback sea turtle. The spongy makeup is similar to the bones seen in open-ocean going vertebrates such as dolphins or ichthyosaur

Ichthyosaurs (Ancient Greek for "fish lizard" – and ) are large extinct marine reptiles. Ichthyosaurs belong to the order known as Ichthyosauria or Ichthyopterygia ('fish flippers' – a designation introduced by Sir Richard Owen in 1842, altho ...

s, and was probably also an adaptation to reduce overall weight.

Plastron

Paleobiology

''Archelon'' was anobligate carnivore

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose food and energy requirements derive from animal tissues (mainly muscle, fat and other so ...

. The thick plastron indicates the animal probably spent a lot of time on the soft, muddy seafloor, likely a slow-moving bottom feeder

A bottom feeder is an aquatic animal that feeds on or near the bottom of a body of water. Biologists often use the terms ''benthos''—particularly for invertebrates such as shellfish, crabs, crayfish, sea anemones, starfish, snails, bri ...

. According to American paleontologist Samuel Wendell Williston

Samuel Wendell Williston (July 10, 1852 – August 30, 1918) was an American educator, entomologist, and paleontologist who was the first to propose that birds developed flight cursorially (by running), rather than arboreally (by leaping from tr ...

, the jaws were adapted for crushing, implying the turtle ate large mollusk

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is e ...

s and crustacea

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean gro ...

ns. In 1914, he suggested that the abundant, thin-shelled, bottom-dwelling Cretaceous bivalve

Bivalvia (), in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class of marine and freshwater molluscs that have laterally compressed bodies enclosed by a shell consisting of two hinged parts. As a group, bival ...

s–some exceeding in diameter–would have easily been able to sustain ''Archelon''. However, these were probably absent in the central Western Interior Seaway by the Early Campanian. Conversely, the beak may have been adapted for shearing

Sheep shearing is the process by which the woollen fleece of a sheep is cut off. The person who removes the sheep's wool is called a '' shearer''. Typically each adult sheep is shorn once each year (a sheep may be said to have been "shorn" or ...

flesh. It might have been able to target larger fish and reptiles, as well as, similar to the leatherback sea turtle, soft-bodied creatures such as squid

True squid are molluscs with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight arms, and two tentacles in the superorder Decapodiformes, though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also called squid despite not strictly fitting t ...

and jellyfish

Jellyfish and sea jellies are the informal common names given to the medusa-phase of certain gelatinous members of the subphylum Medusozoa, a major part of the phylum Cnidaria. Jellyfish are mainly free-swimming marine animals with umbrella- ...

. However, it is possible the sharp beak was used only in combat against other ''Archelon''. The nautilus '' Eutrephoceras dekayi'' was found in great number near an ''Archelon'' specimen, and may have been a potential food source. ''Archelon'' may have also occasionally scavenged off the surface water.

''Archelon'' probably had weaker arms, and thus less swimming power, than the leatherback sea turtle, and so did not frequent the open ocean as much, preferring shallower, calmer waters. This is indicated by the similarity of the humerus/arm and hand/arm ratios of it and cheloniids, which are known to have poor development of the limbs into flippers and a preference for shallow water. Conversely, the large flipper-to-carapace ratio of protostegids and the similarly large flipper spread, like that of the predatory cheloniid

''Archelon'' probably had weaker arms, and thus less swimming power, than the leatherback sea turtle, and so did not frequent the open ocean as much, preferring shallower, calmer waters. This is indicated by the similarity of the humerus/arm and hand/arm ratios of it and cheloniids, which are known to have poor development of the limbs into flippers and a preference for shallow water. Conversely, the large flipper-to-carapace ratio of protostegids and the similarly large flipper spread, like that of the predatory cheloniid loggerhead sea turtle

The loggerhead sea turtle (''Caretta caretta'') is a species of oceanic turtle distributed throughout the world. It is a marine reptile, belonging to the family Cheloniidae. The average loggerhead measures around in carapace length when fully ...

(''Caretta caretta''), combined with a broad body, indicate they could have pursued active prey, though they probably could not have sustained high speeds. Overall, it may have been a moderately-good swimmer, capable of open-ocean travel.

''Archelon'', like other marine turtles, probably would have had to have come onshore to nest; like other turtles, it probably dug out a hollow in the sand, laid several dozens of eggs, and took no part in child rearing. The right lower flipper of the holotype is missing, and stunted growth of remaining flipper bone indicates this occurred early in life. It may have been the result of attempted predation by a bird while a hatchling and trying to escape to the sea, bitten off by some large predator such as a mosasaur

Mosasaurs (from Latin ''Mosa'' meaning the 'Meuse', and Greek ' meaning 'lizard') comprise a group of extinct, large marine reptiles from the Late Cretaceous. Their first fossil remains were discovered in a limestone quarry at Maastricht on th ...

or a ''Xiphactinus

''Xiphactinus'' (from Latin and Greek for " sword-ray") is an extinct genus of large (Shimada, Kenshu, and Michael J. Everhart. "Shark-bitten Xiphactinus audax (Teleostei: Ichthyodectiformes) from the Niobrara Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) of Kansas. ...

'', or was crushed off by larger adults while herding on the shore. However, the latter is unlikely as juveniles probably did not frequent the coasts even during breeding season. Brigitta is estimated to have lived to 100 years, and may have died while partially covered in mud brumating–a state of dormancy–on the ocean floor. However, the longstanding belief that marine turtles brumate underwater like freshwater turtles may be incorrect given the high surfacing-frequency needed to prevent drowning.

Paleoecology

''Archelon'' inhabited the shallow

''Archelon'' inhabited the shallow Western Interior Seaway

The Western Interior Seaway (also called the Cretaceous Seaway, the Niobraran Sea, the North American Inland Sea, and the Western Interior Sea) was a large inland sea that split the continent of North America into two landmasses. The ancient sea, ...

; the muddy, oxygen-depleted seafloor was probably, on average, no more than below the surface, and average water temperature may have been in the Campanian. The Late Cretaceous Dakotas were submerged in the Northern Inland Subprovince, an area characterized by moderate to cool temperatures, with an abundance of plesiosaur

The Plesiosauria (; Greek: πλησίος, ''plesios'', meaning "near to" and ''sauros'', meaning "lizard") or plesiosaurs are an order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared ...

s, hesperornithiform seabirds, and mosasaurs, particularly ''Platecarpus

''Platecarpus'' ("flat wrist") is an extinct genus of aquatic lizards belonging to the mosasaur family, living around 84–81 million years ago during the middle Santonian to early Campanian, of the Late Cretaceous period. Fossils have been found ...

''. There is no fossil evidence for vertebrate migration between the northern and southern provinces. Though sharks were generally more common in the southern province, several sharks are known from the Pierre Shale, including ''Squalus

''Squalus'' is a genus of dogfish sharks in the family Squalidae. Commonly known as spurdogs, these sharks are characterized by smooth dorsal fin spines, teeth in upper and lower jaws similar in size, caudal peduncle with lateral keels; upper pr ...

'', ''Squalicorax

''Squalicorax'', commonly known as the crow shark, is a genus of extinct lamniform shark known to have lived during the Cretaceous period. The genus had a global distribution in the Late Cretaceous epoch. Multiple species within this genus are c ...

'', ''Pseudocorax

''Pseudocorax'' is an extinct genus of mackerel sharks that lived during the Late Cretaceous. It contains six valid species that have been found in Europe, the Middle East, North Africa, and North America. It was formerly assigned to the family ...

'', and ''Cretolamna

''Cretalamna'' is a genus of extinct otodontid shark that lived from the latest Early Cretaceous to Eocene epoch (about 103 to 46 million years ago). It is considered by many to be the ancestor of the largest sharks to have ever lived, ''Otodu ...

''. Other large predatory fish include ichthyodectids such as ''Xiphactinus''. The Pierre Shale's invertebrate assemblage includes a variety of mollusks, namely ammonite

Ammonoids are a group of extinct marine mollusc animals in the subclass Ammonoidea of the class Cephalopoda. These molluscs, commonly referred to as ammonites, are more closely related to living coleoids (i.e., octopuses, squid and cuttlefish) ...

s–from the Pierre Shale '' Placenticeras placenta'', '' Scaphites nodosus'', ''Didymoceras

''Didymoceras'' is an extinct genus of ammonite cephalopod from the Late Cretaceous epoch (approximately 76 Ma). It is one of the most bizarrely shaped genera, with a shell that spirals upwards into a loose, hooked tip. It is thought to have drif ...

'', and '' Baculites ovatus''–bivalves–such as the giant ''Inoceramus

''Inoceramus'' (Greek: translation "strong pot") is an extinct genus of fossil marine pteriomorphian bivalves that superficially resembled the related winged pearly oysters of the extant genus '' Pteria''. They lived from the Early Jurassic ...

''– the squid-like belemnites, and nautilus

The nautilus (, ) is a pelagic marine mollusc of the cephalopod family Nautilidae. The nautilus is the sole extant family of the superfamily Nautilaceae and of its smaller but near equal suborder, Nautilina.

It comprises six living species in t ...

.

As the seaway progressively migrated southward, it is possible ''Archelon'' was unable to migrate with it. The increasing threat of egg or hatchling predation by new marine or mammalian species may have led to the extinction of ''Archelon'', and the disappearance of gigantic protostegids seems to have coincided with the increasing size of dermochelyids. Protostegidae is more-or-less absent in Maastrichtian

The Maastrichtian () is, in the ICS geologic timescale, the latest age (uppermost stage) of the Late Cretaceous Epoch or Upper Cretaceous Series, the Cretaceous Period or System, and of the Mesozoic Era or Erathem. It spanned the interval from ...

deposits, the latest Cretaceous, and probably died off due to a cooling trend which other turtles were able to survive due to some thermoregulatory

Thermoregulation is the ability of an organism to keep its body temperature within certain boundaries, even when the surrounding temperature is very different. A thermoconforming organism, by contrast, simply adopts the surrounding temperature ...

capabilities. Average water temperature may have decreased to depending on estimated CO2 levels. However, some Maastrichtian-age Kansas Pierre Shale fossils may have been eroded millions of years ago, and it is possible ''Archelon'' survived well into the Maastrichtian.

See also

*''Stupendemys

''Stupendemys'' is an extinct genus of freshwater side-necked turtle, belonging to the family Podocnemididae. It is the largest freshwater turtle known to have existed, with a carapace over 2 meters long. Its fossils have been found in norther ...

''

*''Psephophorus

''Psephophorus'' is an extinct genus of sea turtle that lived from the Oligocene to the Pliocene. Its remains have been found in Europe, Africa, North America, and New Zealand. It was first named by Hermann von Meyer in 1847, and contains seve ...

''

*''Atlantochelys

''Atlantochelys'' is an extinct genus of sea turtle from the Upper Cretaceous of New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state o ...

''

*Largest prehistoric animals

The largest prehistoric animals include both vertebrate and invertebrate species. Many of them are described below, along with their typical range of size (for the general dates of extinction, see the link to each). Many species mentioned might ...

References

Cited text

*Further reading

* Hay, O. P. 1908. The fossil turtles of North America. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Publication No. 75, 568 pp, 113 pl. * Wieland, G. R. 1902. Notes on the Cretaceous turtles, ''Toxochelys'' and ''Archelon'', with a classification of the marine Testudinata. American Journal of Science, Series 4, 14:95-108, 2 text-figs.External links

Oceans of Kansas Paleontology

{{Testudines Protostegidae Late Cretaceous turtles of North America Fossil taxa described in 1896 Prehistoric turtle genera Extinct turtles Monotypic prehistoric reptile genera