Apache Communications on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Apache () are a group of culturally related Native American tribes in the

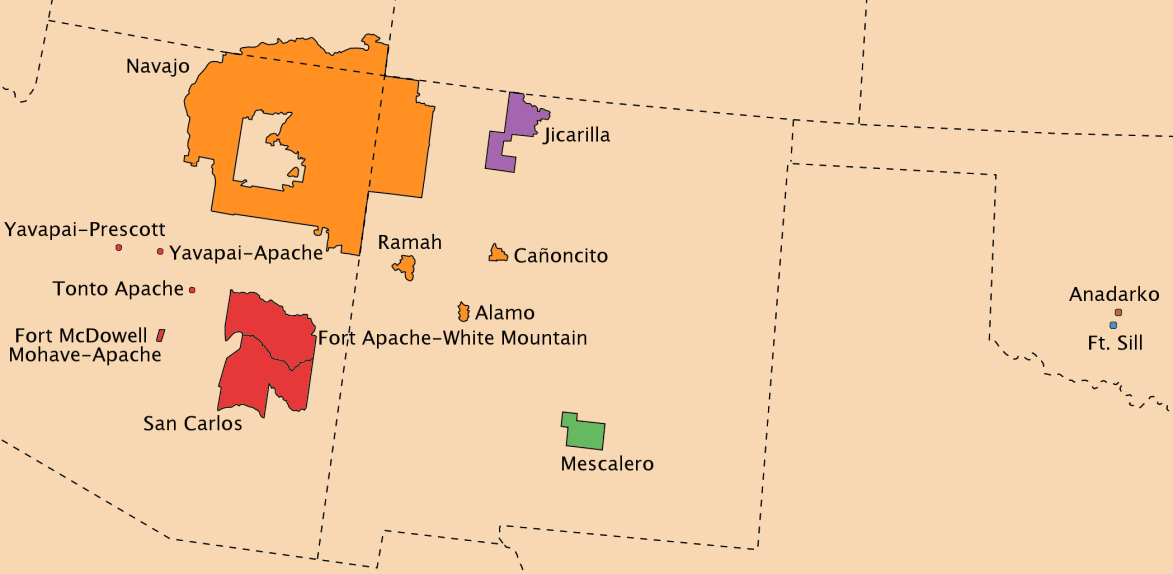

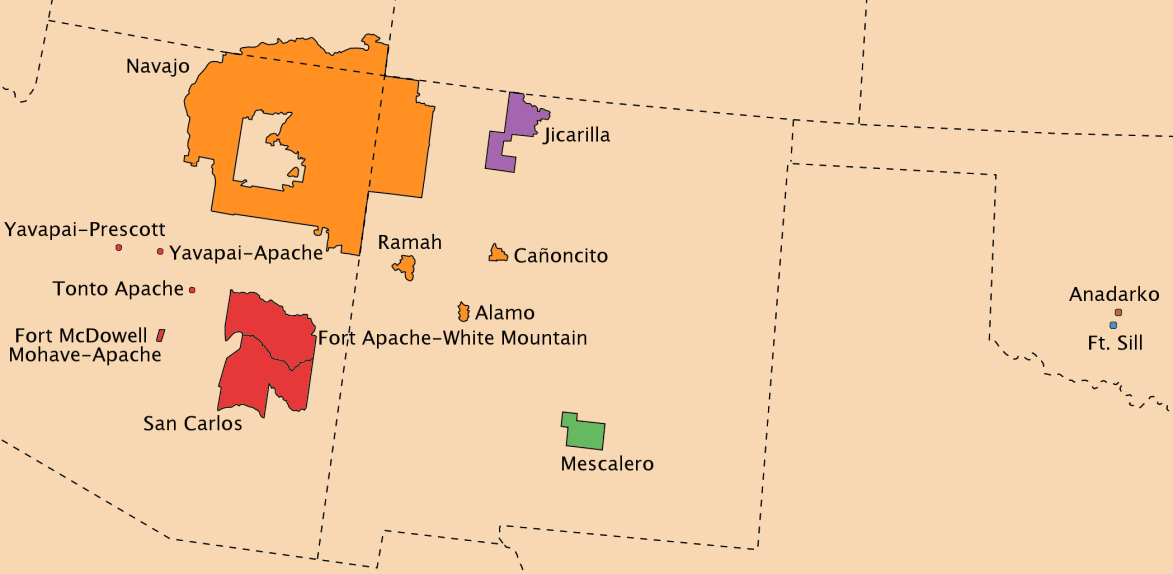

The following Apache tribes are federally recognized:

* Apache of Oklahoma"Tribal Governments by Area: Southern Plains."

The following Apache tribes are federally recognized:

* Apache of Oklahoma"Tribal Governments by Area: Southern Plains."

''National Congress of American Indians.'' Retrieved 7 March 2012. * Fort Sill Apache, Oklahoma *

''National Congress of American Indians.'' Retrieved 7 March 2012. New Mexico * Mescalero, New Mexico * San Carlos Apache,"Tribal Governments by Area: Western."

''National Congress of American Indians.'' Retrieved 7 March 2012. Arizona * Tonto Apache, Arizona *White Mountain Apache of the Fort Apache Reservation, Arizona * Yavapai-Apache, of the Camp Verde Reservation, Arizona The Jicarilla are headquartered in Dulce, New Mexico, while the Mescalero are headquartered in Mescalero, New Mexico. The Western Apache, located in Arizona, is divided into several reservations, which crosscut cultural divisions. The Western Apache reservations include the Fort Apache Indian Reservation,

Many of the historical names of Apache groups that were recorded by non-Apache are difficult to match to modern-day tribes or their subgroups. Over the centuries, many Spanish, French and English-speaking authors did not differentiate between Apache and other semi-nomadic non-Apache peoples who might pass through the same area. Most commonly, Europeans learned to identify the tribes by translating their exonym, what another group whom the Europeans encountered first called the Apache peoples. Europeans often did not learn what the peoples called themselves, their autonyms.

Many of the historical names of Apache groups that were recorded by non-Apache are difficult to match to modern-day tribes or their subgroups. Over the centuries, many Spanish, French and English-speaking authors did not differentiate between Apache and other semi-nomadic non-Apache peoples who might pass through the same area. Most commonly, Europeans learned to identify the tribes by translating their exonym, what another group whom the Europeans encountered first called the Apache peoples. Europeans often did not learn what the peoples called themselves, their autonyms.

While

While

Jicarilla primarily live in Northern New Mexico, Southern Colorado, and the Texas Panhandle. The term ''jicarilla'' comes from the Spanish word for "little gourd."

*

Jicarilla primarily live in Northern New Mexico, Southern Colorado, and the Texas Panhandle. The term ''jicarilla'' comes from the Spanish word for "little gourd."

*

Western Apache include Northern Tonto, Southern Tonto, Cibecue, White Mountain and San Carlos groups. While these subgroups spoke the same language and had kinship ties, Western Apaches considered themselves as separate from each other, according to Goodwin. Other writers have used this term to refer to all non-Navajo Apachean peoples living west of the Rio Grande (thus failing to distinguish the Chiricahua from the other Apacheans). Goodwin's formulation: "all those Apache peoples who have lived within the present boundaries of the state of Arizona during historic times with the exception of the Chiricahua, Warm Springs, and allied Apache, and a small band of Apaches known as the Apache Mansos, who lived in the vicinity of Tucson."

* Cibecue is a Western Apache group, according to Goodwin, from north of the Salt River between the Tonto and White Mountain Apache, consisting of Ceder Creek, Carrizo, and Cibecue (proper) bands.

* San Carlos. A Western Apache group that ranged closest to Tucson according to Goodwin. This group consisted of the Apache Peaks, Arivaipa, Pinal, San Carlos (proper) bands.

**

Western Apache include Northern Tonto, Southern Tonto, Cibecue, White Mountain and San Carlos groups. While these subgroups spoke the same language and had kinship ties, Western Apaches considered themselves as separate from each other, according to Goodwin. Other writers have used this term to refer to all non-Navajo Apachean peoples living west of the Rio Grande (thus failing to distinguish the Chiricahua from the other Apacheans). Goodwin's formulation: "all those Apache peoples who have lived within the present boundaries of the state of Arizona during historic times with the exception of the Chiricahua, Warm Springs, and allied Apache, and a small band of Apaches known as the Apache Mansos, who lived in the vicinity of Tucson."

* Cibecue is a Western Apache group, according to Goodwin, from north of the Salt River between the Tonto and White Mountain Apache, consisting of Ceder Creek, Carrizo, and Cibecue (proper) bands.

* San Carlos. A Western Apache group that ranged closest to Tucson according to Goodwin. This group consisted of the Apache Peaks, Arivaipa, Pinal, San Carlos (proper) bands.

**

The Apache and

The Apache and  The Spanish described Plains dogs as very white, with black spots, and "not much larger than water spaniels."Henderson Plains dogs were slightly smaller than those used for hauling loads by modern Inuit and northern First Nations people in Canada. Recent experiments show these dogs may have pulled loads up to 50 lb (20 kg) on long trips, at rates as high as two or three miles per hour (3 to 5 km/h). The Plains migration theory associates the Apache peoples with the

The Spanish described Plains dogs as very white, with black spots, and "not much larger than water spaniels."Henderson Plains dogs were slightly smaller than those used for hauling loads by modern Inuit and northern First Nations people in Canada. Recent experiments show these dogs may have pulled loads up to 50 lb (20 kg) on long trips, at rates as high as two or three miles per hour (3 to 5 km/h). The Plains migration theory associates the Apache peoples with the

All Apache peoples lived in extended family units (or ''family clusters''); they usually lived close together, with each nuclear family in separate dwellings. An extended family generally consisted of a husband and wife, their unmarried children, their married daughters, their married daughters' husbands, and their married daughters' children. Thus, the extended family is connected through a lineage of women who live together (that is, matrilocal residence), into which men may enter upon marriage (leaving behind his parents' family).

When a daughter married, a new dwelling was built nearby for her and her husband. Among the Navajo, residence rights are ultimately derived from a head mother. Although the Western Apache usually practiced matrilocal residence, sometimes the eldest son chose to bring his wife to live with his parents after marriage. All tribes practiced

All Apache peoples lived in extended family units (or ''family clusters''); they usually lived close together, with each nuclear family in separate dwellings. An extended family generally consisted of a husband and wife, their unmarried children, their married daughters, their married daughters' husbands, and their married daughters' children. Thus, the extended family is connected through a lineage of women who live together (that is, matrilocal residence), into which men may enter upon marriage (leaving behind his parents' family).

When a daughter married, a new dwelling was built nearby for her and her husband. Among the Navajo, residence rights are ultimately derived from a head mother. Although the Western Apache usually practiced matrilocal residence, sometimes the eldest son chose to bring his wife to live with his parents after marriage. All tribes practiced

The Chiricahua language has four words for

The Chiricahua language has four words for

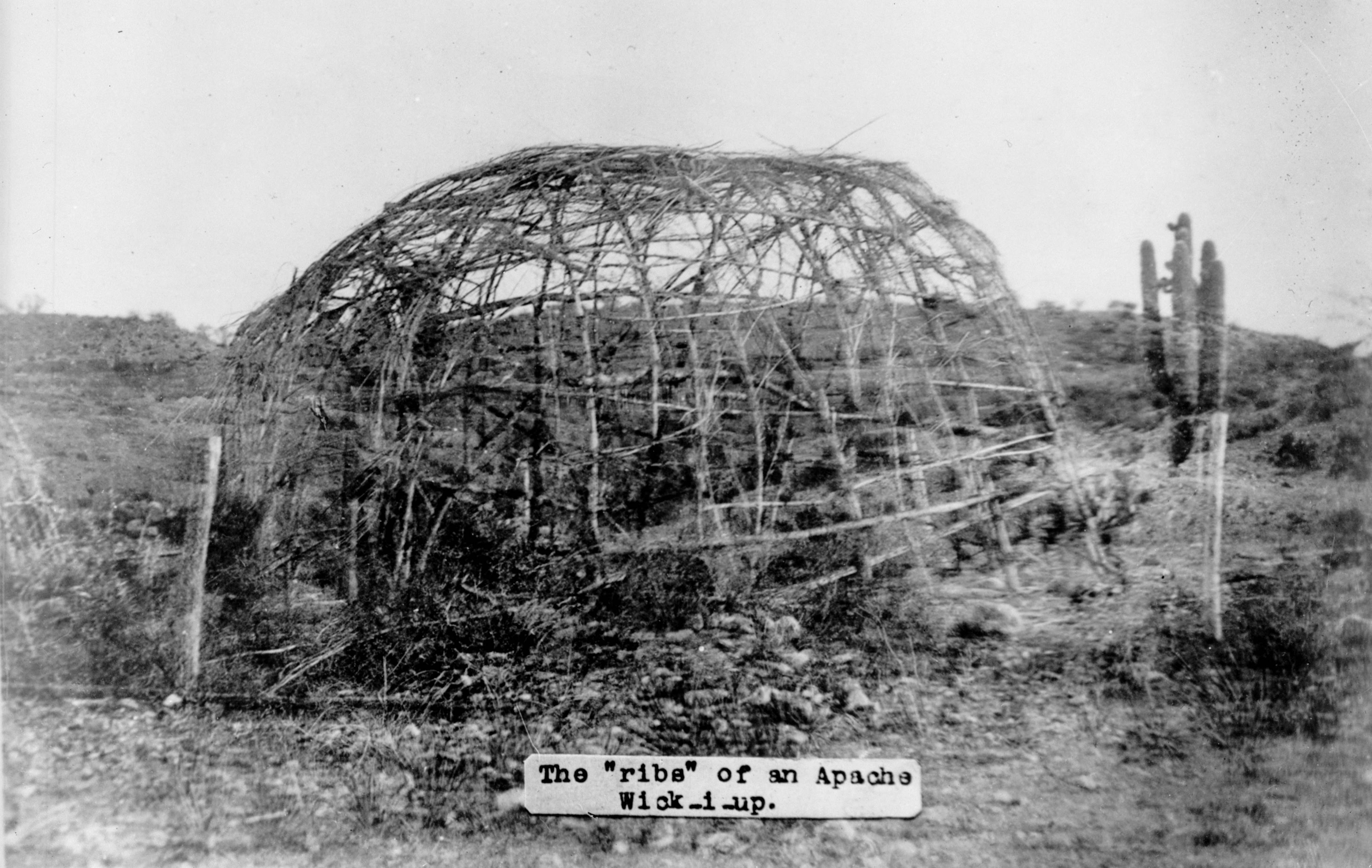

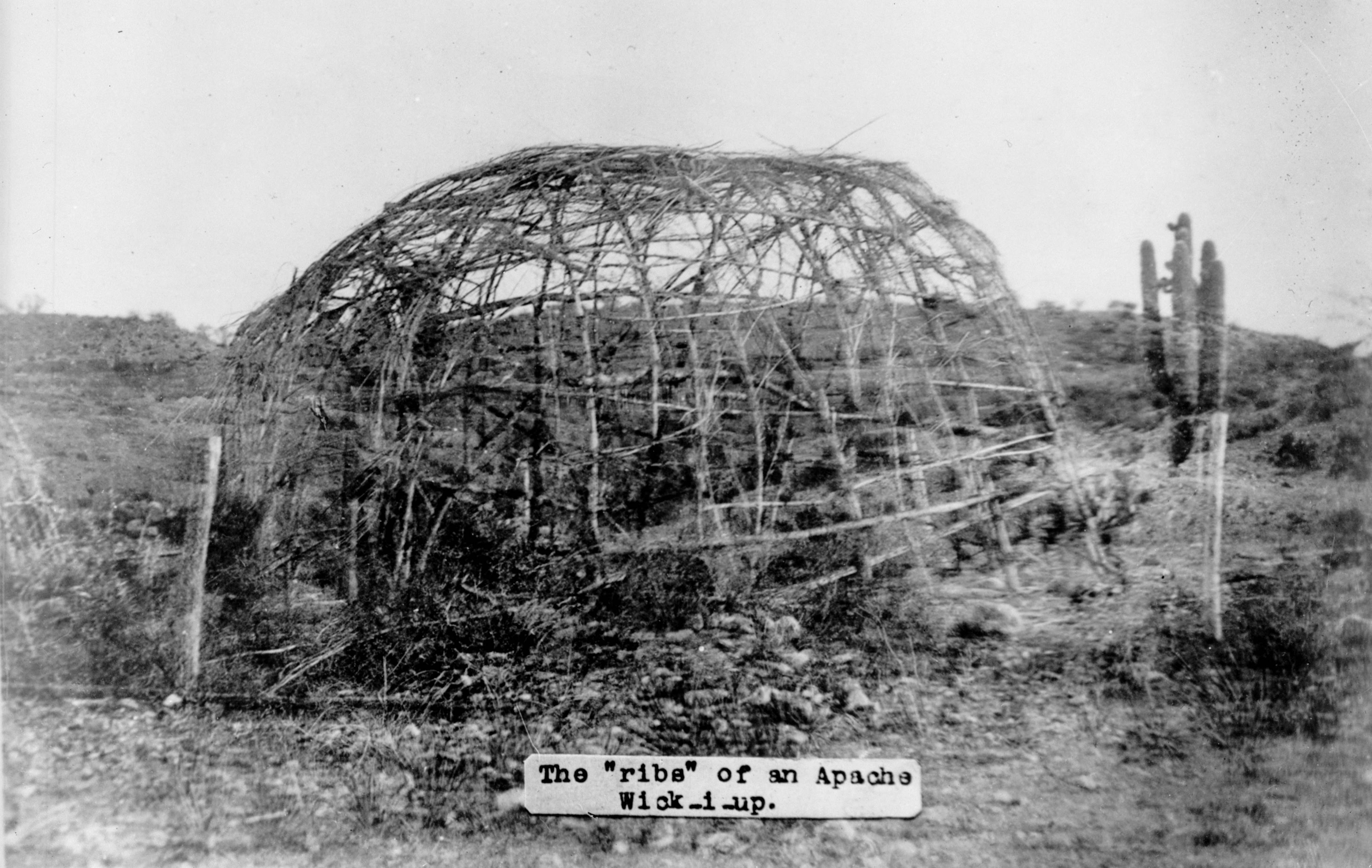

Apache lived in three types of houses. Teepees were common in the plains. Wickiups were common in the highlands; these were framed of wood held together with yucca fibers and covered in brush. If a family member died, the wickiup would be burned. Apache of the desert of northern Mexico lived in hogans, an earthen structure for keeping cool.

Below is a description of Chiricahua wickiups recorded by anthropologist Morris Opler:

Recent research has documented the archaeological remains of Chiricahua Apache wickiups as found on protohistoric and at historical sites, such as Canon de los Embudos where C.S. Fly photographed Geronimo, his people, and dwellings during surrender negotiations in 1886, demonstrating their unobtrusive and improvised nature."

Apache lived in three types of houses. Teepees were common in the plains. Wickiups were common in the highlands; these were framed of wood held together with yucca fibers and covered in brush. If a family member died, the wickiup would be burned. Apache of the desert of northern Mexico lived in hogans, an earthen structure for keeping cool.

Below is a description of Chiricahua wickiups recorded by anthropologist Morris Opler:

Recent research has documented the archaeological remains of Chiricahua Apache wickiups as found on protohistoric and at historical sites, such as Canon de los Embudos where C.S. Fly photographed Geronimo, his people, and dwellings during surrender negotiations in 1886, demonstrating their unobtrusive and improvised nature."

Apache people obtained food from four main sources:

* hunting wild animals,

* gathering wild plants,

* growing domesticated plants

* trading with or raiding neighboring tribes for livestock and agricultural products.

Particular types of foods eaten by a group depending upon their respective environment.

Apache people obtained food from four main sources:

* hunting wild animals,

* gathering wild plants,

* growing domesticated plants

* trading with or raiding neighboring tribes for livestock and agricultural products.

Particular types of foods eaten by a group depending upon their respective environment.

Hunting often had elaborate preparations, such as fasting and religious rituals performed by medicine men before and after the hunt. In Lipan culture, since deer were protected by Mountain Spirits, great care was taken in Mountain Spirit rituals to ensure smooth hunting. Slaughter follows religious guidelines (many of which are recorded in religious stories) prescribing cutting, prayers, and bone disposal. Southern Athabascan hunters often distributed successfully slaughtered game. For example, among the Mescalero a hunter was expected to share as much as half of his kill with a fellow hunter and needy people at the camp. Feelings of individuals about this practice spoke of social obligation and spontaneous generosity.

The most common hunting weapon before the introduction of European guns was the

Hunting often had elaborate preparations, such as fasting and religious rituals performed by medicine men before and after the hunt. In Lipan culture, since deer were protected by Mountain Spirits, great care was taken in Mountain Spirit rituals to ensure smooth hunting. Slaughter follows religious guidelines (many of which are recorded in religious stories) prescribing cutting, prayers, and bone disposal. Southern Athabascan hunters often distributed successfully slaughtered game. For example, among the Mescalero a hunter was expected to share as much as half of his kill with a fellow hunter and needy people at the camp. Feelings of individuals about this practice spoke of social obligation and spontaneous generosity.

The most common hunting weapon before the introduction of European guns was the

The gathering of plants and other food was primarily done by women. The men's job was usually to hunt animals such as deer, buffalo, and small game. However, men helped in certain gathering activities, such as of heavy agave crowns. Numerous plants were used as both food and medicine and in religious ceremonies. Other plants were used for only their religious or medicinal value.

In May, the Western Apache baked and dried agave crowns pounded into pulp and formed into rectangular cakes. At the end of June and beginning of July, saguaro, prickly pear, and cholla fruits were gathered. In July and August, mesquite beans, Spanish bayonet fruit, and

The gathering of plants and other food was primarily done by women. The men's job was usually to hunt animals such as deer, buffalo, and small game. However, men helped in certain gathering activities, such as of heavy agave crowns. Numerous plants were used as both food and medicine and in religious ceremonies. Other plants were used for only their religious or medicinal value.

In May, the Western Apache baked and dried agave crowns pounded into pulp and formed into rectangular cakes. At the end of June and beginning of July, saguaro, prickly pear, and cholla fruits were gathered. In July and August, mesquite beans, Spanish bayonet fruit, and

Apache Tribe of Oklahoma

archive of official website

Fort Sill Apache Tribe

official website

Jicarilla Apache Nation

official website

Mescalero Apache Tribe

official website

official website

White Mountain Apache Tribe

official website

Yavapai-Apache Nation

official website

Apache

Museum of Northern Arizona

Apache Indians

Texas State Historical Association

Apache Tribe of Oklahoma

Oklahoma Historical Society

Apache, Fort Sill

Oklahoma Historical Society

Apache, Lipan

Oklahoma Historical Society

Tonto Apache Tribe

Inter Tribal Council of Arizona {{authority control Native American tribes in Arizona Native American tribes in Colorado Native American tribes in New Mexico Native American tribes in Oklahoma Native American tribes in Texas

Southwestern United States

The Southwestern United States, also known as the American Southwest or simply the Southwest, is a geographic and cultural region of the United States that generally includes Arizona, New Mexico, and adjacent portions of California, Colorado, Ne ...

, which include the Chiricahua

Chiricahua ( ) is a band of Apache Native Americans.

Based in the Southern Plains and Southwestern United States, the Chiricahua (Tsokanende ) are related to other Apache groups: Ndendahe (Mogollon, Carrizaleño), Tchihende (Mimbreño), Sehende ...

, Jicarilla, Lipan, Mescalero, Mimbreño, Ndendahe (Bedonkohe or Mogollon and Nednhi or Carrizaleño and Janero), Salinero, Plains (Kataka or Semat or "Kiowa-Apache

The Plains Apache are a small Southern Athabaskan group who live on the Southern Plains of North America, in close association with the linguistically unrelated Kiowa Tribe. Today, they are centered in Southwestern Oklahoma and Northern Texas and ...

") and Western Apache ( Aravaipa, Pinaleño, Coyotero, Tonto). Distant cousins of the Apache are the Navajo

The Navajo (; British English: Navaho; nv, Diné or ') are a Native American people of the Southwestern United States.

With more than 399,494 enrolled tribal members , the Navajo Nation is the largest federally recognized tribe in the United ...

, with whom they share the Southern Athabaskan languages. There are Apache communities in Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw language, Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the nor ...

and Texas, and reservations in Arizona and New Mexico. Apache people have moved throughout the United States and elsewhere, including urban centers. The Apache Nations are politically autonomous, speak several different languages, and have distinct cultures.

Historically, the Apache homelands have consisted of high mountains, sheltered and watered valleys, deep canyons, deserts, and the southern Great Plains

The Great Plains (french: Grandes Plaines), sometimes simply "the Plains", is a broad expanse of flatland in North America. It is located west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, an ...

, including areas in what is now Eastern Arizona, Northern Mexico (Sonora

Sonora (), officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Sonora ( en, Free and Sovereign State of Sonora), is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the Administrative divisions of Mexico, Federal Entities of Mexico. The state is d ...

and Chihuahua Chihuahua may refer to:

Places

*Chihuahua (state), a Mexican state

**Chihuahua (dog), a breed of dog named after the state

**Chihuahua cheese, a type of cheese originating in the state

**Chihuahua City, the capital city of the state

**Chihuahua Mun ...

) and New Mexico, West Texas, and Southern Colorado. These areas are collectively known as Apacheria.

The Apache tribes fought the invading Spanish and Mexican peoples for centuries. The first Apache raids on Sonora

Sonora (), officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Sonora ( en, Free and Sovereign State of Sonora), is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the Administrative divisions of Mexico, Federal Entities of Mexico. The state is d ...

appear to have taken place during the late 17th century. In 19th-century confrontations during the American-Indian wars, the U.S. Army found the Apache to be fierce warriors and skillful strategists.

Contemporary tribes

The following Apache tribes are federally recognized:

* Apache of Oklahoma"Tribal Governments by Area: Southern Plains."

The following Apache tribes are federally recognized:

* Apache of Oklahoma"Tribal Governments by Area: Southern Plains."''National Congress of American Indians.'' Retrieved 7 March 2012. * Fort Sill Apache, Oklahoma *

Jicarilla Apache

Jicarilla Apache (, Jicarilla language: Jicarilla Dindéi), one of several loosely organized autonomous bands of the Eastern Apache, refers to the members of the Jicarilla Apache Nation currently living in New Mexico and speaking a Southern Athab ...

,"Tribal Governments by Area: Southwest."''National Congress of American Indians.'' Retrieved 7 March 2012. New Mexico * Mescalero, New Mexico * San Carlos Apache,"Tribal Governments by Area: Western."

''National Congress of American Indians.'' Retrieved 7 March 2012. Arizona * Tonto Apache, Arizona *White Mountain Apache of the Fort Apache Reservation, Arizona * Yavapai-Apache, of the Camp Verde Reservation, Arizona The Jicarilla are headquartered in Dulce, New Mexico, while the Mescalero are headquartered in Mescalero, New Mexico. The Western Apache, located in Arizona, is divided into several reservations, which crosscut cultural divisions. The Western Apache reservations include the Fort Apache Indian Reservation,

San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation

The San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation (Western Apache: Tsékʼáádn), in southeastern Arizona, United States, was established in 1872 as a reservation for the Chiricahua Apache tribe as well as surrounding Yavapai and Apache bands removed fro ...

, Yavapai-Apache Nation and Tonto-Apache Reservation.

The Chiricahua were divided into two groups after they were released from being prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

. The majority moved to the Mescalero Reservation and form, with the larger Mescalero political group, the Mescalero Apache Tribe of the Mescalero Apache Reservation, along with the Lipan Apache. The other Chiricahua are enrolled in the Fort Sill Apache Tribe of Oklahoma, headquartered in Apache, Oklahoma

Apache is a town in Caddo County, Oklahoma, United States. The population was 1,444 at the 2010 census.

History

Before opening the Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache Reservation on August 1, 1901, for unrestricted settlement by non-Indians, Land Lott ...

.

The Plains Apache

The Plains Apache are a small Southern Athabaskan group who live on the Southern Plains of North America, in close association with the linguistically unrelated Kiowa Tribe. Today, they are centered in Southwestern Oklahoma and Northern Texas an ...

are located in Oklahoma, headquartered around Anadarko, and are federally recognized as the Apache Tribe of Oklahoma.

Name

The people who are known today as ''Apache'' were first encountered by theconquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (, ; meaning 'conquerors') were the explorer-soldiers of the Spanish and Portuguese Empires of the 15th and 16th centuries. During the Age of Discovery, conquistadors sailed beyond Europe to the Americas, O ...

s of the Spanish crown

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

, and thus the term ''Apache'' has its roots in the Spanish language. The Spanish first used the term (Navajo) in the 1620s, referring to people in the Chama region east of the San Juan River. By the 1640s, they applied the term to southern Athabaskan peoples from the Chama on the east to the San Juan on the west. The ultimate origin is uncertain and lost to Spanish history.

Modern Apache people use the Spanish term to refer to themselves and tribal functions, and so does the US government. However, Apache language speakers also refer to themselves and their people in the Apache term meaning 'person' or 'people'. Distant cousins and Apache subgroup, the Navajo, in their language refer to themselves as the .

The first known written record in Spanish is by in 1598. The most widely accepted origin theory suggests ''Apache'' was borrowed and transliterated from the Zuni word meaning "Navajos" (the plural of "Navajo").Other Zuni words identifying specific Apache groups are "White Mountain Apache" and "San Carlos Apache" (Newman, pp. 32, 63, 65; de Reuse, p. 385). J. P. Harrington reports that can also be used to refer to the Apache in general.

Another theory suggests the term comes from Yavapai meaning "enemy". The Zuni and Yavapai sources are less certain because Oñate used the term before he had encountered any Zuni or Yavapai.de Reuse, p.385 A less likely origin may be from Spanish , meaning "raccoon".

The fame of the tribes' tenacity and fighting skills, probably bolstered by dime novels, was widely known among Europeans. In early 20th century Parisian society, the word ''Apache'' was adopted into French, essentially meaning an outlaw.

The term ''Apachean'' includes the related Navajo people

The Navajo (; British English: Navaho; nv, Diné or ') are a Native American people of the Southwestern United States.

With more than 399,494 enrolled tribal members , the Navajo Nation is the largest federally recognized tribe in the United ...

.

Difficulties in naming

Many of the historical names of Apache groups that were recorded by non-Apache are difficult to match to modern-day tribes or their subgroups. Over the centuries, many Spanish, French and English-speaking authors did not differentiate between Apache and other semi-nomadic non-Apache peoples who might pass through the same area. Most commonly, Europeans learned to identify the tribes by translating their exonym, what another group whom the Europeans encountered first called the Apache peoples. Europeans often did not learn what the peoples called themselves, their autonyms.

Many of the historical names of Apache groups that were recorded by non-Apache are difficult to match to modern-day tribes or their subgroups. Over the centuries, many Spanish, French and English-speaking authors did not differentiate between Apache and other semi-nomadic non-Apache peoples who might pass through the same area. Most commonly, Europeans learned to identify the tribes by translating their exonym, what another group whom the Europeans encountered first called the Apache peoples. Europeans often did not learn what the peoples called themselves, their autonyms.

While

While anthropologist

An anthropologist is a person engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropology is the study of aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms and ...

s agree on some traditional major subgrouping of Apaches, they have often used different criteria to name finer divisions, and these do not always match modern Apache groupings. Some scholars do not consider groups residing in what is now Mexico to be Apache. In addition, an Apache individual has different ways of identification with a group, such as a band or clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, clans may claim descent from founding member or apical ancestor. Clans, in indigenous societies, tend to be endogamous, meaning ...

, as well as the larger tribe or language grouping, which can add to the difficulties in an outsider comprehending the distinctions.

In 1900, the US government classified the members of the Apache tribe in the United States as Pinal Coyotero Pinal may refer to:

People

*Pinal or Pinaleño, a band of the Native American Apache tribe

*Silvia Pinal (born 1931), Mexican actress

*Pinal Shah (born 1987), Indian World Cup wicket-keeper

Places

*Pinal County, Arizona, United States

**Pinal ...

, Jicarilla, Mescalero, San Carlos, Tonto, and White Mountain Apache. The different groups were located in Arizona, New Mexico, and Oklahoma.

In the 1930s, the anthropologist Greenville Goodwin classified the Western Apache into five groups (based on his informants' views of dialect and cultural differences): White Mountain, Cibecue, San Carlos, North Tonto, and South Tonto. Since then, other anthropologists (e.g. Albert Schroeder

The Governing Body of Jehovah's Witnesses is the ruling council of Jehovah's Witnesses, based in the denomination's Warwick, New York, headquarters. The body formulates doctrines, oversees the production of written material for publications and ...

) consider Goodwin's classification inconsistent with pre-reservation cultural divisions. Willem de Reuse

Willem () is a Dutch and West FrisianRienk de Haan, ''Fryske Foarnammen'', Leeuwarden, 2002 (Friese Pers Boekerij), , p. 158. masculine given name. The name is Germanic, and can be seen as the Dutch equivalent of the name William in English, Gui ...

finds linguistic evidence supporting only three major groupings: White Mountain, San Carlos, and Dilzhe'e (Tonto). He believes San Carlos is the most divergent dialect, and that Dilzhe'e is a remnant, intermediate member of a dialect continuum that previously spanned from the Western Apache language to the Navajo.

John Upton Terrell classifies the Apache into western and eastern groups. In the western group, he includes Toboso, Cholome, Jocome, Sibolo or Cibola, Pelone, Manso, and Kiva or Kofa. He includes Chicame (the earlier term for Hispanized Chicano or New Mexicans of Spanish/ Hispanic and Apache descent) among them as having definite Apache connections or names which the Spanish associated with the Apache.

In a detailed study of New Mexico Catholic Church records, David M. Brugge identifies 15 tribal names which the Spanish used to refer to the Apache. These were drawn from records of about 1000 baptisms from 1704 to 1862.

List of names

The list below is based on Foster and McCollough (2001), Opler (1983b, 1983c, 2001), and de Reuse (1983). The term ''Apache'' refers to six major Apache-speaking groups: Chiricahua, Jicarilla, Lipan, Mescalero, Plains Apache, and Western Apache. Historically, the term was also used forComanche

The Comanche or Nʉmʉnʉʉ ( com, Nʉmʉnʉʉ, "the people") are a Native American tribe from the Southern Plains of the present-day United States. Comanche people today belong to the federally recognized Comanche Nation, headquartered in La ...

s, Mojaves, Hualapais, and Yavapais, none of whom speak Apache languages.

Chiricahua – Mimbreño – Ndendahe

*Chiricahua

Chiricahua ( ) is a band of Apache Native Americans.

Based in the Southern Plains and Southwestern United States, the Chiricahua (Tsokanende ) are related to other Apache groups: Ndendahe (Mogollon, Carrizaleño), Tchihende (Mimbreño), Sehende ...

historically lived in Southeastern Arizona. Chíshí (also Tchishi) is a Navajo

The Navajo (; British English: Navaho; nv, Diné or ') are a Native American people of the Southwestern United States.

With more than 399,494 enrolled tribal members , the Navajo Nation is the largest federally recognized tribe in the United ...

word meaning "Chiricahua, southern Apaches in general".

**Ch'úúkʾanén, true Chiricahua (Tsokanende, also Č'ók'ánéń, Č'ó·k'anén, Chokonni, Cho-kon-nen, Cho Kŭnĕ́, Chokonen) is the Eastern Chiricahua band identified by Morris Opler

Morris Edward Opler (May 3, 1907 – May 13, 1996), American anthropologist and advocate of Japanese American civil rights, was born in Buffalo, New York. He was the brother of Marvin Opler, an anthropologist and social psychiatrist.

Morris O ...

. The name is an autonym from the Chiricahua language.

**Gileño (also Apaches de Gila, Apaches de Xila, Apaches de la Sierra de Gila, Xileños, Gilenas, Gilans, Gilanians, Gila Apache, Gilleños) referred to several different Apache and non-Apache groups at different times. ''Gila'' refers to either the Gila River

The Gila River (; O'odham ima Keli Akimel or simply Akimel, Quechan: Haa Siʼil, Maricopa language: Xiil) is a tributary of the Colorado River flowing through New Mexico and Arizona in the United States. The river drains an arid watershed of n ...

or the Gila Mountains. Some of the Gila Apaches were probably later known as the Mogollon Apaches, a Central Apache sub-band, while others probably coalesced into the Chiricahua proper. But, since the term was used indiscriminately for all Apachean groups west of the Rio Grande (i.e. in southeast Arizona and western New Mexico), the reference in historical documents is often unclear. After 1722, Spanish documents start to distinguish between these different groups, in which case ''Apaches de Gila'' refers to the Western Apache living along the Gila River (synonymous with ''Coyotero''). American writers first used the term to refer to the Mimbres (another Central Apache subdivision).

* Mimbreño are the Tchihende, not a ''Chiricahua'' band but a central Apache division sharing the same language with the Chiricahua and the Mescalero divisions, the name being referred to a central Apache division improperly considered as a section of Opler's "''Eastern Chiricahua'' band", and to Albert Schroeder's ''Mimbres'', or ''Warm Springs'' and ''Copper Mines'' "Chiricahua" bands in southwestern New Mexico.

** Copper Mines Mimbreño (also Coppermine) were located on upper reaches of Gila River, New Mexico, having their center in the Pinos Altos area. (See also ''Gileño'' and ''Mimbreño''.)

** Warm Springs Mimbreño (also Warmspring) were located on upper reaches of Gila River, New Mexico, having their center in the Ojo Caliente area. (See also ''Gileño'' and ''Mimbreño''.)

* Ndendahe were a division comprising the Bedonkohe (Mogollon) group and the Nedhni (Carrizaleño and Janero) group, incorrectly called, sometimes, ''Southern Chirichua''.

** Mogollon was considered by Schroeder to be a separate pre-reservation Chiricahua band, while Opler considered the Mogollon to be part of his ''Eastern Chiricahua'' band in New Mexico.

** Nedhni were the southernest group of the Central Apache, having their center in the Carrizal (Carrizaleño) and Janos (Janero) areas, in the Mexican state of Chihuahua.

Jicarilla

Jicarilla primarily live in Northern New Mexico, Southern Colorado, and the Texas Panhandle. The term ''jicarilla'' comes from the Spanish word for "little gourd."

*

Jicarilla primarily live in Northern New Mexico, Southern Colorado, and the Texas Panhandle. The term ''jicarilla'' comes from the Spanish word for "little gourd."

*Carlana

''Carlana'' is a genus of freshwater fish in the family Characidae. It contains the single species ''Carlana eigenmanni'', which is found in Costa Rica, Nicaragua and Panama. The maximum standard length is .

''C. eigenmanni'' is found in fresh ...

(also Carlanes, Sierra Blanca) is Raton Mesa

Raton Mesa is the collective name of several mesas on the eastern side of Raton Pass in New Mexico and Colorado. The name Raton Mesa or Mesas has sometimes been applied to all the mesas that extend east for along the Colorado-New Mexico border f ...

in Southeastern Colorado. In 1726, they joined the Cuartelejo and Paloma, and by the 1730s, they lived with the Jicarilla. The Llanero band of the Jicarilla or the Dáchizh-ó-zhn Jicarilla (defined by James Mooney) might descendants of the Carlana, Cuartelejo, and Paloma. Parts of the group were called Lipiyanes or Llaneros. In 1812, the term ''Carlana'' was used to mean Jicarilla. The Flechas de Palo might have been a part of or absorbed by the Carlana (or Cuartelejo).

Lipan

Lipan (also Ypandis, Ypandes, Ipandes, Ipandi, Lipanes, Lipanos, Lipaines, Lapane, Lipanis, etc.) live in Western Texas today. They traveled from the Pecos River in Eastern New Mexico to the upper Colorado River, San Saba River and Llano River of central Texas across the Edwards Plateau southeast to the Gulf of Mexico. They were close allies of the Natagés. They were also called Plains Lipan (Golgahį́į́, Kó'l kukä'ⁿ, "Prairie Men"), not to be confused with ''Lipiyánes'' or ''Le Panis'' (French for the Pawnee). They were first mentioned in 1718 records as being near the newly established town of San Antonio, Texas. * Pelones ("Bald Ones") lived far from San Antonio and far to the northeast of the Ypandes near theRed River of the South

The Red River, or sometimes the Red River of the South, is a major river in the Southern United States. It was named for its reddish water color from passing through red-bed country in its watershed. It is one of several rivers with that name ...

of North-Central Texas, although able to field 800 warriors, more than the ''Ypandes'' and ''Natagés'' together, they were described as less warlike because they had fewer horses than the Plains Lipan, their population were estimated between 1,600 and 2,400 persons, were the ''Forest Lipan'' division (''Chishį́į́hį́į́'', ''Tcici'', ''Tcicihi'' – "People of the Forest", after 1760 the name Pelones was never used by the Spanish for any Texas Apache group, the Pelones had fled for the Comanche south and southwest, but never mixed up with the Plains Lipan division – retaining their distinct identity, so that Morris Opler

Morris Edward Opler (May 3, 1907 – May 13, 1996), American anthropologist and advocate of Japanese American civil rights, was born in Buffalo, New York. He was the brother of Marvin Opler, an anthropologist and social psychiatrist.

Morris O ...

was told by his Lipan informants in 1935 that their tribal name was "People of the Forest")

Mescalero

Mescaleros primarily live in Eastern New Mexico. *Faraones

Mescalero or Mescalero Apache ( apm, Naa'dahéńdé) is an Apache tribe of Southern Athabaskan–speaking Native Americans. The tribe is federally recognized as the Mescalero Apache Tribe of the Mescalero Apache Reservation, located in south-ce ...

(also Apaches Faraone, Paraonez, Pharaones, Taraones, or Taracones) is derived from Spanish ''Faraón'' meaning "Pharaoh." Before 1700, the name was vague. Between 1720 and 1726, it referred to Apache between the Rio Grande

The Rio Grande ( and ), known in Mexico as the Río Bravo del Norte or simply the Río Bravo, is one of the principal rivers (along with the Colorado River) in the southwestern United States and in northern Mexico.

The length of the Rio G ...

, the Pecos River

The Pecos River ( es, Río Pecos) originates in north-central New Mexico and flows into Texas, emptying into the Rio Grande. Its headwaters are on the eastern slope of the Sangre de Cristo mountain range in Mora County north of Pecos, New Mexico ...

, the area around Santa Fe, and the Conchos River. After 1726, ''Faraones'' only referred to the groups of the north and central parts of this region. The Faraones like were part of the modern-day Mescalero or merged with them. After 1814, the term ''Faraones'' disappeared and was replaced by ''Mescalero''.

* Sierra Blanca Mescaleros were a northern Mescalero group from the Sierra Blanca Mountains, who roamed in what is now eastern New Mexico and western Texas.

*Sacramento Mescalero

)

, image_map = Sacramento County California Incorporated and Unincorporated areas Sacramento Highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 250x200px

, map_caption = Location within Sacramento C ...

s were a northern Mescalero group from the Sacramento and Organ Mountains, who roamed in what is now eastern New Mexico and western Texas.

*Guadalupe Mescalero

Guadalupe or Guadeloupe may refer to:

Places Bolivia

* Guadalupe, Potosí Brazil

* Guadalupe, Piauí, a municipality in the state of Piauí

* Guadalupe, Rio de Janeiro, a neighbourhood in the city of Rio de Janeiro Colombia

* Guadalupe, A ...

s. were a northern Mescalero group from the Guadalupe Mountains, who roamed in what is now eastern New Mexico and western Texas.

* Limpia Mescaleros were a southern Mescalero group from the Limpia Mountains (later named as Davis Mountains) and roamed in what is now eastern New Mexico and western Texas.

*Natagés

Mescalero or Mescalero Apache ( apm, Naa'dahéńdé) is an Apache tribe of Southern Athabaskan–speaking Native Americans. The tribe is federally recognized as the Mescalero Apache Tribe of the Mescalero Apache Reservation, located in south-ce ...

(also ''Natagees'', ''Apaches del Natafé'', ''Natagêes'', ''Yabipais Natagé'', ''Natageses'', ''Natajes'') is a term used from 1726 to 1820 to refer to the Faraón, Sierra Blanca, and Siete Ríos Apaches of southeastern New Mexico. In 1745, the Natagé are reported to have consisted of the Mescalero (around El Paso and the Organ Mountains) and the Salinero (around Rio Salado), but these were probably the same group, were oft called by the Spanish and Apaches themselves ''true Apaches'', had had a considerable influence on the decision making of some bands of the Western Lipan in the 18th century. After 1749, the term became synonymous with Mescalero, which eventually replaced it.

Ethnobotany

A full list of documented plant uses by the Mescalero tribe can be found at http://naeb.brit.org/uses/tribes/11/ (which also includes the Chiricahua; 198 documented plant uses) and http://naeb.brit.org/uses/tribes/12/ (83 documented uses).Plains Apache

Plains Apache

The Plains Apache are a small Southern Athabaskan group who live on the Southern Plains of North America, in close association with the linguistically unrelated Kiowa Tribe. Today, they are centered in Southwestern Oklahoma and Northern Texas an ...

(Kiowa-Apache, Naisha, Naʼishandine) are headquartered in Southwest Oklahoma. Historically, they followed the Kiowa. Other names for them include Ná'įįsha, Ná'ęsha, Na'isha, Na'ishandine, Na-i-shan-dina, Na-ishi, Na-e-ca, Ną'ishą́, Nadeicha, Nardichia, Nadíisha-déna, Na'dí'į́shą́ʼ, Nądí'įįshąą, and Naisha.

* Querechos referred to by Coronado in 1541, possibly Plains Apaches, at times maybe Navajo. Other early Spanish might have also called them Vaquereo or Llanero.

Western Apache

Western Apache include Northern Tonto, Southern Tonto, Cibecue, White Mountain and San Carlos groups. While these subgroups spoke the same language and had kinship ties, Western Apaches considered themselves as separate from each other, according to Goodwin. Other writers have used this term to refer to all non-Navajo Apachean peoples living west of the Rio Grande (thus failing to distinguish the Chiricahua from the other Apacheans). Goodwin's formulation: "all those Apache peoples who have lived within the present boundaries of the state of Arizona during historic times with the exception of the Chiricahua, Warm Springs, and allied Apache, and a small band of Apaches known as the Apache Mansos, who lived in the vicinity of Tucson."

* Cibecue is a Western Apache group, according to Goodwin, from north of the Salt River between the Tonto and White Mountain Apache, consisting of Ceder Creek, Carrizo, and Cibecue (proper) bands.

* San Carlos. A Western Apache group that ranged closest to Tucson according to Goodwin. This group consisted of the Apache Peaks, Arivaipa, Pinal, San Carlos (proper) bands.

**

Western Apache include Northern Tonto, Southern Tonto, Cibecue, White Mountain and San Carlos groups. While these subgroups spoke the same language and had kinship ties, Western Apaches considered themselves as separate from each other, according to Goodwin. Other writers have used this term to refer to all non-Navajo Apachean peoples living west of the Rio Grande (thus failing to distinguish the Chiricahua from the other Apacheans). Goodwin's formulation: "all those Apache peoples who have lived within the present boundaries of the state of Arizona during historic times with the exception of the Chiricahua, Warm Springs, and allied Apache, and a small band of Apaches known as the Apache Mansos, who lived in the vicinity of Tucson."

* Cibecue is a Western Apache group, according to Goodwin, from north of the Salt River between the Tonto and White Mountain Apache, consisting of Ceder Creek, Carrizo, and Cibecue (proper) bands.

* San Carlos. A Western Apache group that ranged closest to Tucson according to Goodwin. This group consisted of the Apache Peaks, Arivaipa, Pinal, San Carlos (proper) bands.

**Arivaipa

The San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation (Western Apache: Tsékʼáádn), in southeastern Arizona, United States, was established in 1872 as a reservation for the Chiricahua Apache tribe as well as surrounding Yavapai and Apache bands removed fro ...

(also Aravaipa) is a band of the San Carlos Apache. Schroeder believes the Arivaipa were a separate people in pre-reservation times. ''Arivaipa'' is a Hispanized word from the O'odham language. The Arivaipa are known as ''Tsézhiné'' ("Black Rock") in the Western Apache language.

** Pinal (also ''Pinaleño''). One of the bands of the San Carlos group of Western Apache, described by Goodwin. Also used along with ''Coyotero'' to refer more generally to one of two major Western Apache divisions. Some Pinaleño were referred to as the ''Gila Apache''.

* Tonto. Goodwin divided into Northern Tonto and Southern Tonto groups, living in the north and west areas of the Western Apache groups according to Goodwin. This is north of Phoenix, north of the Verde River. Schroeder has suggested that the Tonto are originally Yavapais who assimilated Western Apache culture. Tonto is one of the major dialects of the Western Apache language. Tonto Apache speakers are traditionally bilingual in Western Apache and Yavapai. Goodwin's Northern Tonto consisted of Bald Mountain, Fossil Creek, Mormon Lake, and Oak Creek bands; Southern Tonto consisted of the Mazatzal band and unidentified "semi-bands".

* White Mountain are the easternmost group of the Western Apache, according to Goodwin, who included the Eastern White Mountain and Western White Mountain Apache.

** Coyotero refers to a southern pre-reservation White Mountain group of the Western Apache, but has also been used more widely to refer to the Apache in general, Western Apache, or an Apache band in the high plains of Southern Colorado to Kansas.

Ethnobotany

*A full list of 134 ethnobotany plant uses for Western Apache can be found at http://naeb.brit.org/uses/tribes/14/. *A full list of 165 ethnobotany plant uses for White Mountain Apache can be found at http://naeb.brit.org/uses/tribes/15/. *A full list of 14 ethnobotany plant uses for the San Carlos Apache can be found at http://naeb.brit.org/uses/tribes/13/.Other terms

* Llanero is a Spanish-language borrowing meaning "plains dweller". The name referred to several different groups who hunted buffalo on theGreat Plains

The Great Plains (french: Grandes Plaines), sometimes simply "the Plains", is a broad expanse of flatland in North America. It is located west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, an ...

. (See also ''Carlanas''.)

* Lipiyánes

Lipan Apache are a band of Apache, a Southern Athabaskan languages, Southern Athabaskan Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous people, who have lived in the Oasisamerica, Southwest and Southern Plains for centuries. At the time of Europe ...

(also Lipiyán, Lipillanes). A coalition of splinter groups of Nadahéndé (Natagés), Guhlkahéndé, and Lipan of the 18th century under the leadership of Picax-Ande-Ins-Tinsle ("Strong Arm"), who fought the Comanche on the Plains. This term is not to be confused with ''Lipan''.

History

Entry into the Southwest

The Apache and

The Apache and Navajo

The Navajo (; British English: Navaho; nv, Diné or ') are a Native American people of the Southwestern United States.

With more than 399,494 enrolled tribal members , the Navajo Nation is the largest federally recognized tribe in the United ...

tribal groups of the North American Southwest speak related languages of the Athabaskan

Athabaskan (also spelled ''Athabascan'', ''Athapaskan'' or ''Athapascan'', and also known as Dene) is a large family of indigenous languages of North America, located in western North America in three areal language groups: Northern, Pacific C ...

language family. Other Athabaskan-speaking people in North America continue to reside in Alaska, western Canada, and the Northwest Pacific Coast. Anthropological evidence suggests that the Apache and Navajo peoples lived in these same northern locales before migrating to the Southwest sometime between AD 1200 and 1500.

The Apaches' nomadic way of life complicates accurate dating, primarily because they constructed less substantial dwellings than other Southwestern groups. Since the early 21st century, substantial progress has been made in dating and distinguishing their dwellings and other forms of material culture. They left behind a more austere set of tools and material goods than other Southwestern cultures.

The Athabaskan-speaking group probably moved into areas that were concurrently occupied or recently abandoned by other cultures. Other Athabaskan speakers, perhaps including the Southern Athabaskan, adapted many of their neighbors' technology and practices in their own cultures. Thus sites where early Southern Athabaskans may have lived are difficult to locate and even more difficult to firmly identify as culturally Southern Athabaskan. Recent advances have been made in the regard in the far southern portion of the American Southwest.

There are several hypotheses about Apache migrations. One posits that they moved into the Southwest from the Great Plains. In the mid-16th century, these mobile groups lived in tents, hunted bison

Bison are large bovines in the genus ''Bison'' (Greek: "wild ox" (bison)) within the tribe Bovini. Two extant and numerous extinct species are recognised.

Of the two surviving species, the American bison, ''B. bison'', found only in North Ame ...

and other game, and used dogs to pull travois loaded with their possessions. Substantial numbers of the people and a wide range were recorded by the Spanish in the 16th century.

In April 1541, while traveling on the plains east of the Pueblo region, Francisco Coronado referred to the people as "dog nomads." He wrote:

The Spanish described Plains dogs as very white, with black spots, and "not much larger than water spaniels."Henderson Plains dogs were slightly smaller than those used for hauling loads by modern Inuit and northern First Nations people in Canada. Recent experiments show these dogs may have pulled loads up to 50 lb (20 kg) on long trips, at rates as high as two or three miles per hour (3 to 5 km/h). The Plains migration theory associates the Apache peoples with the

The Spanish described Plains dogs as very white, with black spots, and "not much larger than water spaniels."Henderson Plains dogs were slightly smaller than those used for hauling loads by modern Inuit and northern First Nations people in Canada. Recent experiments show these dogs may have pulled loads up to 50 lb (20 kg) on long trips, at rates as high as two or three miles per hour (3 to 5 km/h). The Plains migration theory associates the Apache peoples with the Dismal River culture

The Dismal River culture refers to a set of cultural attributes first seen in the Dismal River area of Nebraska in the 1930s by archaeologists William Duncan Strong, Waldo Rudolph Wedel and A. T. Hill. Also known as Dismal River aspect and Dismal ...

, an archaeological culture

An archaeological culture is a recurring assemblage of types of artifacts, buildings and monuments from a specific period and region that may constitute the material culture remains of a particular past human society. The connection between thes ...

known primarily from ceramics and house remains, dated 1675–1725, which has been excavated in Nebraska, eastern Colorado, and western Kansas.

Although the first documentary sources mention the Apache, and historians have suggested some passages indicate a 16th-century entry from the north, archaeological data indicate they were present on the plains long before this first reported contact.

A competing theory posits their migration south, through the Rocky Mountains, ultimately reaching the American Southwest by the 14th century or perhaps earlier. An archaeological material culture assemblage identified in this mountainous zone as ancestral Apache has been referred to as the "Cerro Rojo complex". This theory does not preclude arrival via a plains route as well, perhaps concurrently, but to date the earliest evidence has been found in the mountainous Southwest. The Plains Apache have a significant Southern Plains cultural influence.

When the Spanish arrived in the area, trade between the long established Pueblo peoples and the Southern Athabaskan was well established. They reported the Pueblo exchanged maize and woven cotton goods for bison meat, and hides and materials for stone tools. Coronado observed the Plains people wintering near the Pueblo in established camps. Later Spanish sovereignty over the area disrupted trade between the Pueblo and the diverging Apache and Navajo groups. The Apache quickly acquired horses, improving their mobility for quick raids on settlements. In addition, the Pueblo were forced to work Spanish mission lands and care for mission flocks; they had fewer surplus goods to trade with their neighbors.

In 1540, Coronado reported that the modern Western Apache area was uninhabited, although some scholars have argued that he simply did not see the American Indians. Other Spanish explorers first mention "Querechos" living west of the Rio Grande in the 1580s. To some historians, this implies the Apaches moved into their current Southwestern homelands in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. Other historians note that Coronado reported that Pueblo women and children had often been evacuated by the time his party attacked their dwellings, and that he saw some dwellings had been recently abandoned as he moved up the Rio Grande. This might indicate the semi-nomadic Southern Athabaskan had advance warning about his hostile approach and evaded encounter with the Spanish. Archaeologists are finding ample evidence of an early proto-Apache presence in the Southwestern mountain zone in the 15th century and perhaps earlier. The Apache presence on both the Plains and in the mountainous Southwest indicate that the people took multiple early migration routes.

Conflict with Mexico and the United States

In general, the recently arrived Spanish colonists, who settled in villages, and Apache bands developed a pattern of interaction over a few centuries. Both raided and traded with each other. Records of the period seem to indicate that relationships depended on the specific villages and bands: a band might be friends with one village and raid another. When war occurred, the Spanish would send troops; after a battle both sides would "sign a treaty" and go home. The traditional and sometimes treacherous relationships continued after the independence of Mexico in 1821. By 1835 Mexico had placed a bounty on Apache scalps (see scalping), but certain villages still traded with some bands. WhenJuan José Compà

''Juan'' is a given name

A given name (also known as a forename or first name) is the part of a personal name quoted in that identifies a person, potentially with a middle name as well, and differentiates that person from the other members ...

, the leader of the Copper Mines Mimbreño Apaches, was killed for bounty money in 1837, '' Mangas Coloradas'' (Red Sleeves) or ''Dasoda-hae'' (He just sits there) became the principal chief and war leader; also in 1837 Soldado Fiero

Soldado is a Spanish and Portuguese word meaning soldier. It may refer to:

Arts and media

*''El Soldado'', a 1634 play by Luis Quiñones de Benavente

*''El Soldado'', an 1892 play by Adolfo León Gómez

*"El Soldado", a song recorded by Barbarito ...

(a.k.a. Fuerte), leader of the Warm Springs Mimbreño Apaches, was killed by Mexican soldiers near Janos, and his son '' Cuchillo Negro'' (Black Knife) became the principal chief and war leader. They (being now Mangas Coloradas the first chief and Cuchillo Negro the second chief of the whole Tchihende or Mimbreño people) conducted a series of retaliatory raids against the Mexicans. By 1856, authorities in horse-rich Durango

Durango (), officially named Estado Libre y Soberano de Durango ( en, Free and Sovereign State of Durango; Tepehuán: ''Korian''; Nahuatl: ''Tepēhuahcān''), is one of the 31 states which make up the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico, situated in ...

would claim that Indian raids (mostly Comanche and Apache) in their state had taken nearly 6,000 lives, abducted 748 people, and forced the abandonment of 358 settlements over the previous 20 years.

When the United States went to war against Mexico in 1846, many Apache bands promised U.S. soldiers safe passage through their lands. When the U.S. claimed former territories of Mexico in 1846, ''Mangas Coloradas'' signed a peace treaty with the nation, respecting them as conquerors of the Mexicans' land. An uneasy peace with U.S. citizens held until the 1850s. An influx of gold miners into the Santa Rita Mountains led to conflict with the Apache. This period is sometimes called the Apache Wars

The Apache Wars were a series of armed conflicts between the United States Army and various Apache tribal confederations fought in the southwest between 1849 and 1886, though minor hostilities continued until as late as 1924. After the Mexic ...

.

United States' concept of a reservation __NOTOC__

Reservation may refer to: Places

Types of places:

* Indian reservation, in the United States

* Military base, often called reservations

* Nature reserve

Government and law

* Reservation (law), a caveat to a treaty

* Reservation in India, ...

had not been used by the Spanish, Mexicans or other Apache neighbors before. Reservations were often badly managed, and bands that had no kinship relationships were forced to live together. No fences existed to keep people in or out. It was common for a band to be allowed to leave for a short period of time. Other times a band would leave without permission, to raid, return to their homeland to forage, or to simply get away. The U.S. military usually had forts nearby to keep the bands on the reservations by finding and returning those who left. The reservation policies of the U.S. caused conflict and war with the various Apache bands who left the reservations for almost another quarter century.

War between the Apache peoples and Euro-Americans has led to a stereotypical focus on certain aspects of Apache cultures. These have often been distorted through misunderstanding of their cultures, as noted by anthropologist

An anthropologist is a person engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropology is the study of aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms and ...

Keith Basso

Keith Hamilton Basso (March 15, 1940 – August 4, 2013) was a cultural and linguistic anthropologist noted for his study of the Western Apaches, specifically those from the community of Cibecue, Arizona. Basso was professor emeritus of anthropolo ...

:

Forced removal

In 1875, United States military forced the removal of an estimated 1500 Yavapai andDilzhe'e Apache

The Tonto Apache (Dilzhę́’é, also Dilzhe'e, Dilzhe’eh Apache) is one of the groups of Western Apache people and a federally recognized tribe, the Tonto Apache Tribe of Arizona. The term is also used for their dialect, one of the three di ...

(better known as ''Tonto Apache'') from the Rio Verde Indian Reserve and its several thousand acres of treaty lands promised to them by the United States government. At the orders of Indian Commissioner L.E. Dudley, U.S. Army troops made the people, young and old, walk through winter-flooded rivers, mountain passes and narrow canyon trails to get to the Indian Agency at San Carlos, away. The trek killed several hundred people. The people were interned there for 25 years while white settlers took over their land. Only a few hundred ever returned to their lands. At the San Carlos reservation, the Buffalo soldiers of the 9th Cavalry Regiment—replacing the 8th Cavalry who were being stationed to Texas—guarded the Apaches from 1875 to 1881.

Beginning in 1879, an Apache uprising against the reservation system led to Victorio's War between Chief Victorio's band of Apaches and the 9th Cavalry.

Defeat

Most United States' histories of this era report that the final defeat of an Apache band took place when 5,000 US troops forcedGeronimo

Geronimo ( apm, Goyaałé, , ; June 16, 1829 – February 17, 1909) was a prominent leader and medicine man from the Bedonkohe band of the Ndendahe Apache people. From 1850 to 1886, Geronimo joined with members of three other Central Apache ba ...

's group of 30 to 50 men, women and children to surrender on September 4, 1886, at Skeleton Canyon, Arizona. The Army sent this band and the Chiricahua scouts who had tracked them to military confinement in Florida at Fort Pickens and, subsequently, Ft. Sill

Fort Sill is a United States Army post north of Lawton, Oklahoma, about 85 miles (136.8 km) southwest of Oklahoma City. It covers almost .

The fort was first built during the Indian Wars. It is designated as a National Historic Landmark ...

, Oklahoma.

Many books were written on the stories of hunting and trapping during the late 19th century. Many of these stories involve Apache raids and the failure of agreements with Americans and Mexicans. In the post-war era, the US government arranged for Apache children to be taken from their families for adoption by white Americans in assimilation programs.

Pre-reservation culture

Social organization

All Apache peoples lived in extended family units (or ''family clusters''); they usually lived close together, with each nuclear family in separate dwellings. An extended family generally consisted of a husband and wife, their unmarried children, their married daughters, their married daughters' husbands, and their married daughters' children. Thus, the extended family is connected through a lineage of women who live together (that is, matrilocal residence), into which men may enter upon marriage (leaving behind his parents' family).

When a daughter married, a new dwelling was built nearby for her and her husband. Among the Navajo, residence rights are ultimately derived from a head mother. Although the Western Apache usually practiced matrilocal residence, sometimes the eldest son chose to bring his wife to live with his parents after marriage. All tribes practiced

All Apache peoples lived in extended family units (or ''family clusters''); they usually lived close together, with each nuclear family in separate dwellings. An extended family generally consisted of a husband and wife, their unmarried children, their married daughters, their married daughters' husbands, and their married daughters' children. Thus, the extended family is connected through a lineage of women who live together (that is, matrilocal residence), into which men may enter upon marriage (leaving behind his parents' family).

When a daughter married, a new dwelling was built nearby for her and her husband. Among the Navajo, residence rights are ultimately derived from a head mother. Although the Western Apache usually practiced matrilocal residence, sometimes the eldest son chose to bring his wife to live with his parents after marriage. All tribes practiced sororate

Sororate marriage is a type of marriage in which a husband engages in marriage or sexual relations with the sister of his wife, usually after the death of his wife or if his wife has proven infertile. The opposite is levirate marriage.

From an a ...

and levirate marriages.

Apache men practiced varying degrees of "avoidance" of his wife's close relatives, a practice often most strictly observed by distance between mother-in-law and son-in-law. The degree of avoidance differed by Apache group. The most elaborate system was among the Chiricahua, where men had to use indirect polite speech toward and were not allowed to be within visual sight of the wife's female relatives, whom he had to avoid. His female Chiricahua relatives through marriage also avoided him.

Several extended families worked together as a "local group", which carried out certain ceremonies, and economic and military activities. Political control was mostly present at the local group level. Local groups were headed by a chief

Chief may refer to:

Title or rank

Military and law enforcement

* Chief master sergeant, the ninth, and highest, enlisted rank in the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Space Force

* Chief of police, the head of a police department

* Chief of the boa ...

, a male who had much influence due to his effectiveness and reputation. The position was not hereditary

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic inform ...

, and was often filled by members of different extended families. The chief's influence was as strong as he was evaluated to be—no group member was obliged to follow the chief. Western Apache criteria for a good chief included: industriousness, generosity, impartiality, forbearance, conscientiousness, and eloquence in language.

Many Apache peoples joined several local groups into " bands". Banding was strongest among the Chiricahua and Western Apache, and weak among the Lipan and Mescalero. The Navajo did not organize into bands, perhaps because of the requirements of the sheepherd

A shepherd or sheepherder is a person who tends, herds, feeds, or guards flocks of sheep. ''Shepherd'' derives from Old English ''sceaphierde (''sceap'' 'sheep' + ''hierde'' ' herder'). ''Shepherding is one of the world's oldest occupations, ...

ing economy. However, the Navajo did have "the outfit", a group of relatives that was larger than the extended family, but smaller than a local group community or a band.

On a larger level, Western Apache bands organized into what Grenville Goodwin

Grenville W. "Gren" Goodwin (1898 – 27 August 1951) was Mayor of Ottawa for several months in 1951. His hometown was Prescott, Ontario and he was an optometrist by profession. He moved to Ottawa in 1911. He served in France during World ...

called "groups". He reported five groups for the Western Apache: Northern Tonto, Southern Tonto, Cibecue, San Carlos, and White Mountain. The Jicarilla grouped their bands into " moieties", perhaps influenced by the northeastern Pueblo. The Western Apache and Navajo also had a system of matrilineal "clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, clans may claim descent from founding member or apical ancestor. Clans, in indigenous societies, tend to be endogamous, meaning ...

s" organized further into ''phratries

In ancient Greece, a phratry ( grc, φρᾱτρῐ́ᾱ, phrātríā, brotherhood, kinfolk, derived from grc, φρᾱ́τηρ, phrā́tēr, brother, links=no) was a group containing citizens in some city-states. Their existence is known in most I ...

'' (perhaps influenced by the western Pueblo).

The notion of " tribe" in Apache cultures is very weakly developed; essentially it was only a recognition "that one owed a modicum of hospitality to those of the same speech, dress, and customs." The six Apache tribes had political independence from each other and even fought against each other. For example, the Lipan once fought against the Mescalero.

Kinship systems

The Apache tribes have two distinctly different kinship term systems: a ''Chiricahua type'' and a ''Jicarilla type.'' The Chiricahua-type system is used by the Chiricahua, Mescalero, and Western Apache. The Western Apache system differs slightly from the other two systems, and has some similarities to the Navajo system. The Jicarilla type, which is similar to the Dakota– Iroquoiskinship systems

In anthropology, kinship is the web of social relationships that form an important part of the lives of all humans in all societies, although its exact meanings even within this discipline are often debated. Anthropologist Robin Fox says that ...

, is used by the Jicarilla, Navajo, Lipan, and Plains Apache. The Navajo system is more divergent among the four, having similarities with the Chiricahua-type system. The Lipan and Plains Apache systems are very similar.

=Chiricahua

= The Chiricahua language has four words for

The Chiricahua language has four words for grandparent

Grandparents, individually known as grandmother and grandfather, are the parents of a person's father or mother – paternal or maternal. Every sexually-reproducing living organism who is not a genetic chimera has a maximum of four genetic gra ...

: ''-chú''All kinship terms in Apache languages are inherently possessed, which means they must be preceded by a possessive prefix

A prefix is an affix which is placed before the Word stem, stem of a word. Adding it to the beginning of one word changes it into another word. For example, when the prefix ''un-'' is added to the word ''happy'', it creates the word ''unhappy'' ...

. This is signified by the preceding hyphen. "maternal grandmother", ''-tsúyé'' "maternal grandfather", ''-chʼiné'' "paternal grandmother", ''-nálé'' "paternal grandfather". Additionally, a grandparent's siblings are identified by the same word; thus, one's maternal grandmother, one's maternal grandmother's sisters, and one's maternal grandmother's brothers are all called ''-chú''. Furthermore, the grandchild terms are reciprocal, that is, one uses the same term to refer to their grandchild. For example, a person's maternal grandmother is called ''-chú'' and that grandmother also calls that granddaughter ''-chú'' (i.e. ''-chú'' can mean the child of either your own daughter or your sibling's daughter.)

Chiricahua cousins are not distinguished from siblings through kinship terms. Thus, the same word refers to either a sibling or a cousin (there are not separate terms for parallel-cousin and cross-cousin). The terms depend on the sex of the speaker (unlike the English terms ''brother'' and ''sister''): ''-kʼis'' "same-sex sibling or same-sex cousin", ''-´-ląh'' "opposite-sex sibling or opposite-sex cousin". This means if one is a male, then one's brother is called ''-kʼis'' and one's sister is called ''-´-ląh''. If one is a female, then one's brother is called ''-´-ląh'' and one's sister is called ''-kʼis''. Chiricahuas in a ''-´-ląh'' relationship observed great restraint and respect toward that relative; cousins (but not siblings) in a ''-´-ląh'' relationship may practice total ''avoidance''.

Two different words are used for each parent according to sex: ''-mááʼ'' "mother", ''-taa'' "father". Likewise, there are two words for a parent's child according to sex: ''-yáchʼeʼ'' "daughter", ''-gheʼ'' "son".

A parent's siblings are classified together regardless of sex: ''-ghúyé'' "maternal aunt or uncle (mother's brother or sister)", ''-deedééʼ'' "paternal aunt or uncle (father's brother or sister)". These two terms are reciprocal like the grandparent/grandchild terms. Thus, ''-ghúyé'' also refers to one's opposite-sex sibling's son or daughter (that is, a person will call their maternal aunt ''-ghúyé'' and that aunt will call them ''-ghúyé'' in return).

Ethnobotany A list of 198 ethnobotany plant uses for the Chiricahua can be found at http://naeb.brit.org/uses/tribes/11/, which also includes the Mescalero.

=Jicarilla

= Unlike the Chiricahua system, the Jicarilla have only two terms for grandparents according to sex: ''-chóó'' "grandmother", ''-tsóyéé'' "grandfather". They do not have separate terms for maternal or paternal grandparents. The terms are also used of a grandparent's siblings according to sex. Thus, ''-chóó'' refers to one's grandmother or one's grand-aunt (either maternal or paternal); ''-tsóyéé'' refers to one's grandfather or one's grand-uncle. These terms are not reciprocal. There is a single word for grandchild (regardless of sex): ''-tsóyí̱í̱''. There are two terms for each parent. These terms also refer to that parent's same-sex sibling: ''-ʼnííh'' "mother or maternal aunt (mother's sister)", ''-kaʼéé'' "father or paternal uncle (father's brother)". Additionally, there are two terms for a parent's opposite-sex sibling depending on sex: ''-daʼá̱á̱'' "maternal uncle (mother's brother)", ''-béjéé'' "paternal aunt (father's sister). Two terms are used for same-sex and opposite-sex siblings. These terms are also used for parallel-cousins: ''-kʼisé'' "same-sex sibling or same-sex parallel cousin (i.e. same-sex father's brother's child or mother's sister's child)", ''-´-láh'' "opposite-sex sibling or opposite parallel cousin (i.e. opposite-sex father's brother's child or mother's sister's child)". These two terms can also be used for cross-cousins. There are also three sibling terms based on the age relative to the speaker: ''-ndádéé'' "older sister", ''-´-naʼá̱á̱'' "older brother", ''-shdá̱zha'' "younger sibling (i.e. younger sister or brother)". Additionally, there are separate words for cross-cousins: ''-zeedń'' "cross-cousin (either same-sex or opposite-sex of speaker)", ''-iłnaaʼaash'' "male cross-cousin" (only used by male speakers). A parent's child is classified with their same-sex sibling's or same-sex cousin's child: ''-zhácheʼe'' "daughter, same-sex sibling's daughter, same-sex cousin's daughter", ''-gheʼ'' "son, same-sex sibling's son, same-sex cousin's son". There are different words for an opposite-sex sibling's child: ''-daʼá̱á̱'' "opposite-sex sibling's daughter", ''-daʼ'' "opposite-sex sibling's son".Housing

Apache lived in three types of houses. Teepees were common in the plains. Wickiups were common in the highlands; these were framed of wood held together with yucca fibers and covered in brush. If a family member died, the wickiup would be burned. Apache of the desert of northern Mexico lived in hogans, an earthen structure for keeping cool.

Below is a description of Chiricahua wickiups recorded by anthropologist Morris Opler:

Recent research has documented the archaeological remains of Chiricahua Apache wickiups as found on protohistoric and at historical sites, such as Canon de los Embudos where C.S. Fly photographed Geronimo, his people, and dwellings during surrender negotiations in 1886, demonstrating their unobtrusive and improvised nature."

Apache lived in three types of houses. Teepees were common in the plains. Wickiups were common in the highlands; these were framed of wood held together with yucca fibers and covered in brush. If a family member died, the wickiup would be burned. Apache of the desert of northern Mexico lived in hogans, an earthen structure for keeping cool.

Below is a description of Chiricahua wickiups recorded by anthropologist Morris Opler:

Recent research has documented the archaeological remains of Chiricahua Apache wickiups as found on protohistoric and at historical sites, such as Canon de los Embudos where C.S. Fly photographed Geronimo, his people, and dwellings during surrender negotiations in 1886, demonstrating their unobtrusive and improvised nature."

Food

Apache people obtained food from four main sources:

* hunting wild animals,

* gathering wild plants,

* growing domesticated plants

* trading with or raiding neighboring tribes for livestock and agricultural products.

Particular types of foods eaten by a group depending upon their respective environment.

Apache people obtained food from four main sources:

* hunting wild animals,

* gathering wild plants,

* growing domesticated plants

* trading with or raiding neighboring tribes for livestock and agricultural products.

Particular types of foods eaten by a group depending upon their respective environment.

Hunting

Hunting was done primarily by men, although there were sometimes exceptions depending on animal and culture (e.g. Lipan women could help in hunting rabbits and Chiricahua boys were also allowed to hunt rabbits). Hunting often had elaborate preparations, such as fasting and religious rituals performed by medicine men before and after the hunt. In Lipan culture, since deer were protected by Mountain Spirits, great care was taken in Mountain Spirit rituals to ensure smooth hunting. Slaughter follows religious guidelines (many of which are recorded in religious stories) prescribing cutting, prayers, and bone disposal. Southern Athabascan hunters often distributed successfully slaughtered game. For example, among the Mescalero a hunter was expected to share as much as half of his kill with a fellow hunter and needy people at the camp. Feelings of individuals about this practice spoke of social obligation and spontaneous generosity.

The most common hunting weapon before the introduction of European guns was the

Hunting often had elaborate preparations, such as fasting and religious rituals performed by medicine men before and after the hunt. In Lipan culture, since deer were protected by Mountain Spirits, great care was taken in Mountain Spirit rituals to ensure smooth hunting. Slaughter follows religious guidelines (many of which are recorded in religious stories) prescribing cutting, prayers, and bone disposal. Southern Athabascan hunters often distributed successfully slaughtered game. For example, among the Mescalero a hunter was expected to share as much as half of his kill with a fellow hunter and needy people at the camp. Feelings of individuals about this practice spoke of social obligation and spontaneous generosity.

The most common hunting weapon before the introduction of European guns was the bow and arrow

The bow and arrow is a ranged weapon system consisting of an elastic launching device (bow) and long-shafted projectiles ( arrows). Humans used bows and arrows for hunting and aggression long before recorded history, and the practice was comm ...

. Various hunting techniques were used. Some involved wearing animal head masks as a disguise. Whistles were sometimes used to lure animals closer. Another technique was the relay method where hunters positioned at various points would chase the prey in turns in order to tire the animal. A similar method involved chasing the prey down a steep cliff.

Eating certain animals was taboo. Although different cultures had different taboos, common examples included bears, peccaries, turkeys, fish, snakes, insects, owls, and coyotes. An example of taboo differences: the black bear was a part of the Lipan diet (although less common as buffalo, deer, or antelope), but the Jicarilla never ate bear because it was considered an evil animal. Some taboos were a regional phenomenon, such as fish, which was taboo throughout the southwest (e.g. in certain Pueblo cultures like the Hopi

The Hopi are a Native American ethnic group who primarily live on the Hopi Reservation in northeastern Arizona, United States. As of the 2010 census, there are 19,338 Hopi in the country. The Hopi Tribe is a sovereign nation within the Unite ...

and Zuni) and considered to resemble a snake (an evil animal) in physical appearance.

Western Apache hunted deer and pronghorns mostly in the ideal late fall. After the meat was smoked into jerky around November, they migrated from the farm sites in the mountains along stream banks to winter camps in the Salt, Black, Gila river

The Gila River (; O'odham ima Keli Akimel or simply Akimel, Quechan: Haa Siʼil, Maricopa language: Xiil) is a tributary of the Colorado River flowing through New Mexico and Arizona in the United States. The river drains an arid watershed of n ...

and even the Colorado River valleys.

The Chiricahua mostly hunted deer followed by pronghorn. Lesser game included cottontail rabbits (but not jack rabbits), opossum

Opossums () are members of the marsupial order Didelphimorphia () endemic to the Americas. The largest order of marsupials in the Western Hemisphere, it comprises 93 species in 18 genera. Opossums originated in South America and entered North ...

s, squirrels, surplus horses, surplus mules, ''wapiti'' (elk), wild cattle and wood rat

''Wood Rat'' is the 1st combination of the sexagenary cycle of the Chinese zodiac.

Years of the Wood Rat