Antonious on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anthony the Great ( grc-gre, Ἀντώνιος ''Antṓnios''; ar, القديس أنطونيوس الكبير; la, Antonius; ; c. 12 January 251 – 17 January 356), was a Christian monk from Egypt, revered since his death as a saint. He is distinguished from other saints named Anthony, such as , by various epithets: , , , , , and . For his importance among the

For five or six years he devoted himself to the instruction and organization of the great body of monks that had grown up around him; but then he once again withdrew into the inner desert that lay between the Nile and the Red Sea, near the shore of which he fixed his abode on a mountain (

For five or six years he devoted himself to the instruction and organization of the great body of monks that had grown up around him; but then he once again withdrew into the inner desert that lay between the Nile and the Red Sea, near the shore of which he fixed his abode on a mountain (

Anthony had been secretly buried on the mountain-top where he had chosen to live. His remains were reportedly discovered in 361, and transferred to

Anthony had been secretly buried on the mountain-top where he had chosen to live. His remains were reportedly discovered in 361, and transferred to

Desert Fathers

The Desert Fathers or Desert Monks were early Christian hermits and ascetics, who lived primarily in the Scetes desert of the Roman province of Egypt

, conventional_long_name = Roman Egypt

, common_name = Egypt

, subdivision = Province

, na ...

and to all later Christian monasticism

Christian monasticism is the devotional practice of Christians who live ascetic and typically cloistered lives that are dedicated to Christian worship. It began to develop early in the history of the Christian Church, modeled upon scriptural e ...

, he is also known as the . His feast day is celebrated on 17 January among the Orthodox

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pa ...

and Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

churches and on Tobi ToBI (; an abbreviation of tones and break indices) is a set of conventions for transcribing and annotating the prosody of speech. The term "ToBI" is sometimes used to refer to the conventions used for describing American English specifically, whic ...

22 in the Coptic calendar

The Coptic calendar, also called the Alexandrian calendar, is a liturgical calendar used by the Coptic Orthodox Church and also used by the farming populace in Egypt. It was used for fiscal purposes in Egypt until the adoption of the Gregoria ...

.

The biography of Anthony's life by Athanasius of Alexandria

Athanasius I of Alexandria, ; cop, ⲡⲓⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ ⲁⲑⲁⲛⲁⲥⲓⲟⲩ ⲡⲓⲁⲡⲟⲥⲧⲟⲗⲓⲕⲟⲥ or Ⲡⲁⲡⲁ ⲁⲑⲁⲛⲁⲥⲓⲟⲩ ⲁ̅; (c. 296–298 – 2 May 373), also called Athanasius the Great, ...

helped to spread the concept of Christian monasticism

Monasticism (from Ancient Greek , , from , , 'alone'), also referred to as monachism, or monkhood, is a religious way of life in which one renounces worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual work. Monastic life plays an important role ...

, particularly in Western Europe via its Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

translations. He is often erroneously considered the first Christian monk, but as his biography and other sources make clear, there were many ascetics before him. Anthony was, however, among the first known to go into the wilderness (about AD 270), which seems to have contributed to his renown. Accounts of Anthony enduring supernatural temptation during his sojourn in the Eastern Desert

The Eastern Desert (Archaically known as Arabia or the Arabian Desert) is the part of the Sahara desert that is located east of the Nile river. It spans of North-Eastern Africa and is bordered by the Nile river to the west and the Red Sea and ...

of Egypt inspired the depiction of his temptations in visual art and literature.

Anthony is appealed to against infectious diseases, particularly skin diseases. In the past, many such afflictions, including ergotism, erysipelas

Erysipelas () is a relatively common bacterial infection of the superficial layer of the skin ( upper dermis), extending to the superficial lymphatic vessels within the skin, characterized by a raised, well-defined, tender, bright red rash, t ...

, and shingles

Shingles, also known as zoster or herpes zoster, is a viral disease characterized by a painful skin rash with blisters in a localized area. Typically the rash occurs in a single, wide mark either on the left or right side of the body or face. ...

, were referred to as ''Saint Anthony's fire''.

''Life of Anthony''

Most of what is known about Anthony comes from the ''Life of Anthony''. Written in Greek around 360 byAthanasius of Alexandria

Athanasius I of Alexandria, ; cop, ⲡⲓⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ ⲁⲑⲁⲛⲁⲥⲓⲟⲩ ⲡⲓⲁⲡⲟⲥⲧⲟⲗⲓⲕⲟⲥ or Ⲡⲁⲡⲁ ⲁⲑⲁⲛⲁⲥⲓⲟⲩ ⲁ̅; (c. 296–298 – 2 May 373), also called Athanasius the Great, ...

, it depicts Anthony as an illiterate and holy man who through his existence in a primordial landscape has an absolute connection to the divine truth, which always is in harmony with that of Athanasius as the biographer.

A continuation of the genre of secular Greek biography, it became his most widely read work. Sometime before 374 it was translated into Latin by Evagrius of Antioch Evagrius of Antioch was a claimant to the See of Antioch from 388 to 392. He succeeded Paulinus and had the support of the Eustathian party, and was a rival to Flavian during the so-called Meletian schism.

History

After Paulinus' death in 388 ...

. The Latin translation helped the ''Life'' become one of the best known works of literature in the Christian world, a status it would hold through the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

.

Translated into several languages, it became something of a best seller in its day and played an important role in the spreading of the ascetic

Asceticism (; from the el, ἄσκησις, áskesis, exercise', 'training) is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from sensual pleasures, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their p ...

ideal in Eastern and Western Christianity. It later served as an inspiration to Christian monastics in both the East and the West, and helped to spread the concept of Christian monasticism, particularly in Western Europe via its Latin translations.

Many stories are also told about Anthony in the ''Sayings of the Desert Fathers

The ''Sayings of the Desert Fathers'' ( la, Apophthegmata Patrum Aegyptiorum; el, ἀποφθέγματα τῶν πατέρων, translit=Apophthégmata tōn Patérōn) is the name given to various textual collections consisting of stories and ...

''.

Anthony probably spoke only his native language, Coptic

Coptic may refer to:

Afro-Asia

* Copts, an ethnoreligious group mainly in the area of modern Egypt but also in Sudan and Libya

* Coptic language, a Northern Afro-Asiatic language spoken in Egypt until at least the 17th century

* Coptic alphabet ...

, but his sayings were spread in a Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

translation. He himself dictated letters in Coptic, seven of which are extant.

Life

Early years

Anthony was born in Koma inLower Egypt

Lower Egypt ( ar, مصر السفلى '; ) is the northernmost region of Egypt, which consists of the fertile Nile Delta between Upper Egypt and the Mediterranean Sea, from El Aiyat, south of modern-day Cairo, and Dahshur. Historically, ...

to wealthy landowner parents. When he was about 20 years old, his parents died and left him with the care of his unmarried sister. Shortly thereafter, he decided to follow the gospel exhortation in Matthew 19

Matthew 19 is the nineteenth chapter in the Gospel of Matthew in the New Testament section of the Christian Bible.Halley, Henry H. ''Halley's Bible Handbook'': an Abbreviated Bible Commentary, 23rd edition, Zondervan Publishing House, 1962 The b ...

: 21, "If you want to be perfect, go, sell what you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasures in heaven." Anthony gave away some of his family's lands to his neighbors, sold the remaining property, and donated the funds to the poor. He then left to live an ascetic

Asceticism (; from the el, ἄσκησις, áskesis, exercise', 'training) is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from sensual pleasures, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their p ...

life, placing his sister with a group of Christian virgins.

Hermit

For the next fifteen years, Anthony remained in the area, spending the first years as the disciple of another localhermit

A hermit, also known as an eremite (adjectival form: hermitic or eremitic) or solitary, is a person who lives in seclusion. Eremitism plays a role in a variety of religions.

Description

In Christianity, the term was originally applied to a Ch ...

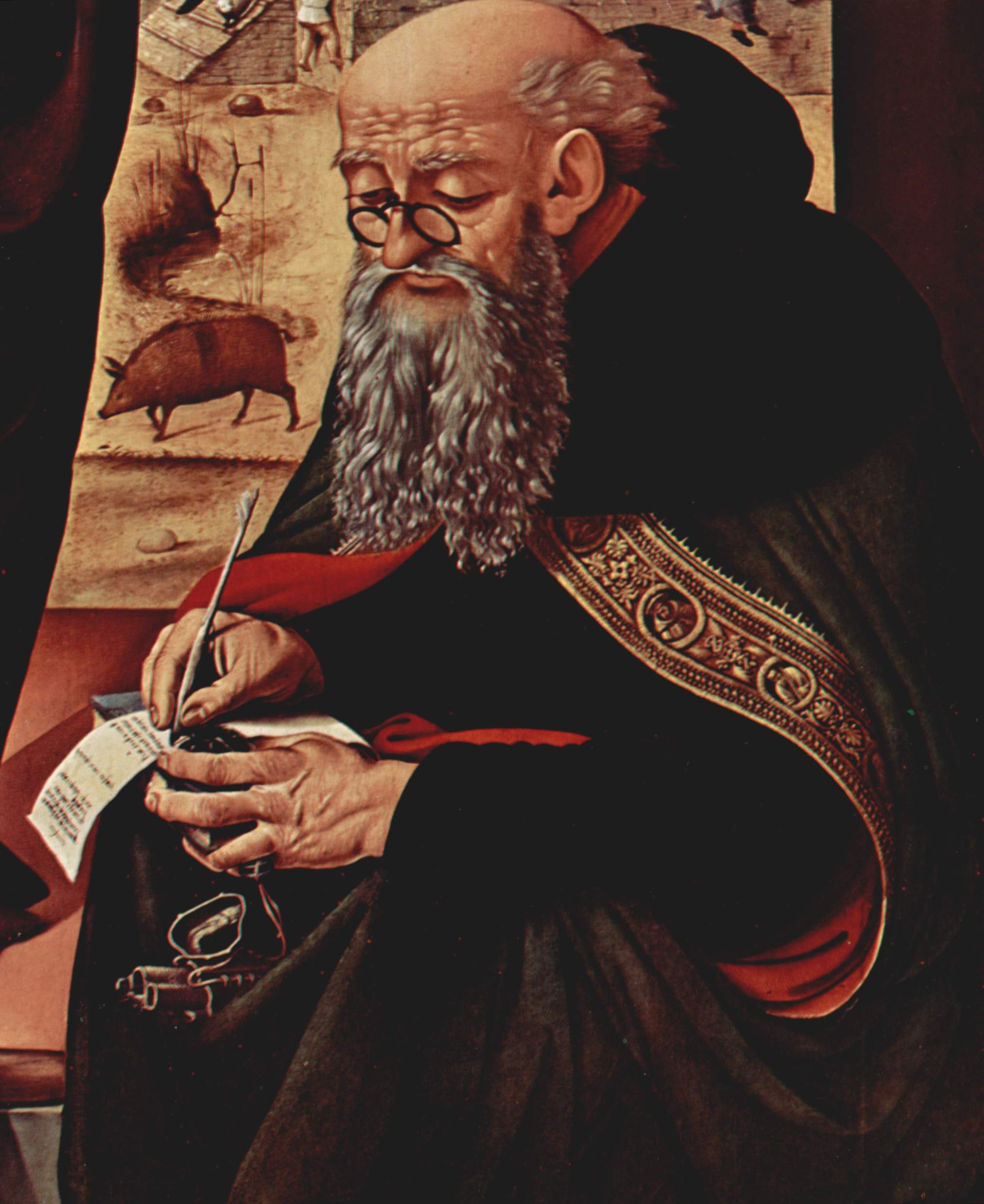

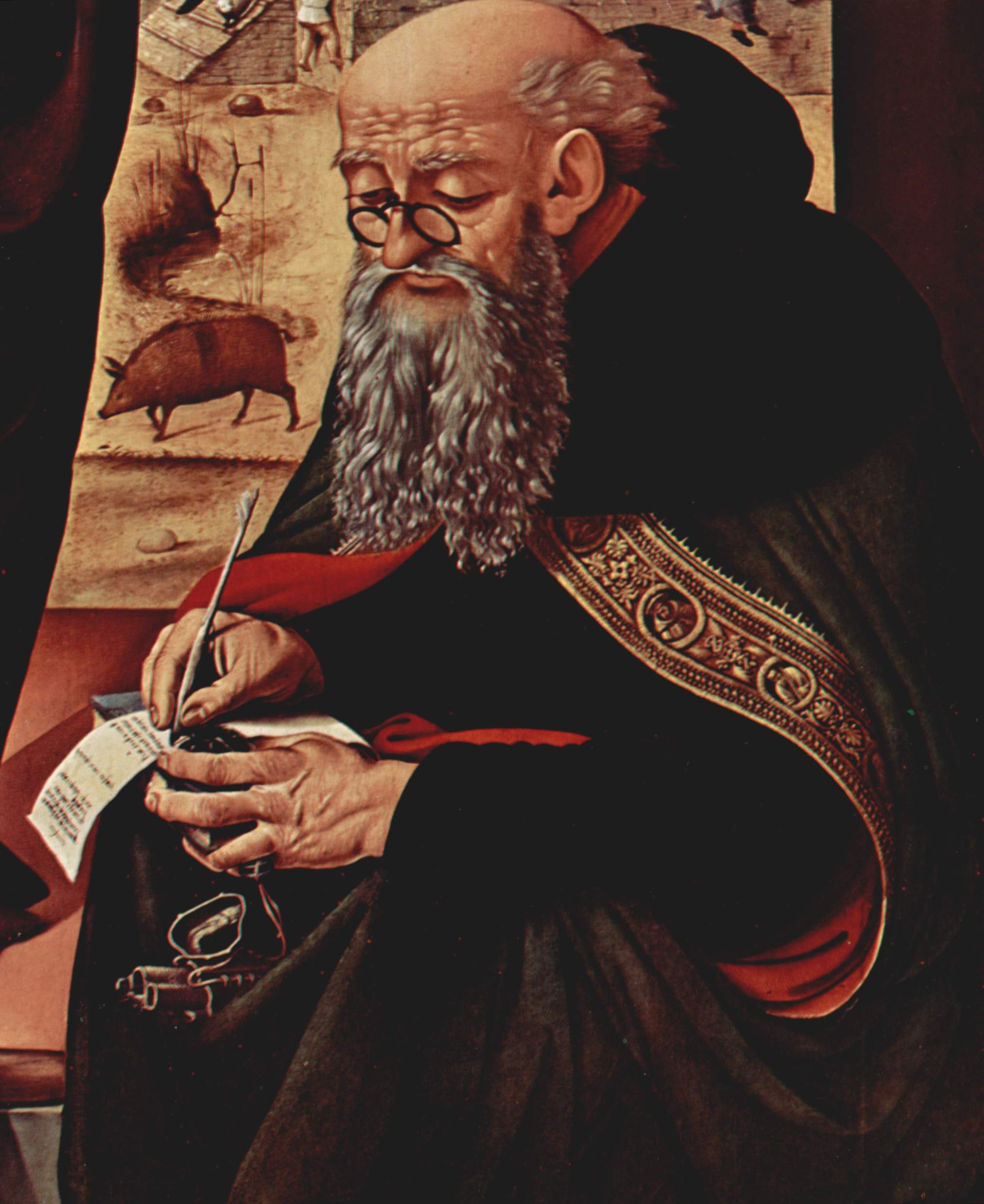

. There are various legends that he worked as a swineherd

A swineherd is a person who raises and herds pigs as livestock.

Swineherds in literature

* In the New Testament are mentioned shepherd of pigs, mentioned in the Pig (Gadarene) the story shows Jesus exorcising a demon or demons from a man and a ...

during this period.

According to the ''Temptation of Saint Anthony'' (1878) by Félicien Rops

Félicien Victor Joseph Rops (7 July 1833 – 23 August 1898) was a Belgian artist associated with Symbolism and the Parisian Fin-de Siecle. He was a painter, illustrator, caricaturist and a prolific and innovative print maker, particularly in ...

:

. Christian ascetics such as Thecla

Thecla ( grc, Θέκλα, ) was a saint of the early Christian Church, and a reported follower of Paul the Apostle. The earliest record of her life comes from the ancient apocryphal ''Acts of Paul and Thecla''.

Church tradition

The ''Acts of ...

had likewise retreated to isolated locations at the outskirts of cities. Anthony is notable for having decided to surpass this tradition and headed out into the desert proper. He left for the alkaline Nitrian Desert

The Nitrian Desert is a desert region in northwestern Egypt, lying between Alexandria and Cairo west of the Nile Delta. It is known for its history of Christian monasticism."Nitrian Desert", in F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone, eds., ''The Oxfor ...

(later the location of the noted monasteries of Nitria, Kellia

Kellia ("the Cells"), referred to as "the innermost desert", was a 4th-century Egyptian Christian monastic community spread out over many square kilometers in the Nitrian Desert about 40 miles south of Alexandria. It was one of three centers of ...

, and Scetis

Wadi El Natrun (Arabic: "Valley of Natron"; Coptic: , "measure of the hearts") is a depression in northern Egypt that is located below sea level and below the Nile River level. The valley contains several alkaline lakes, natron-rich salt dep ...

) on the edge of the Western Desert about west of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

. He remained there for 13 years.

Anthony maintained a very strict ascetic diet. He ate only bread, salt and water and never meat or wine. He ate at most only once a day and sometimes fasted

Fasting is the abstention from eating and sometimes drinking. From a purely physiological context, "fasting" may refer to the metabolic status of a person who has not eaten overnight (see "Breakfast"), or to the metabolic state achieved after co ...

through two or four days.

According to Athanasius

Athanasius I of Alexandria, ; cop, ⲡⲓⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ ⲁⲑⲁⲛⲁⲥⲓⲟⲩ ⲡⲓⲁⲡⲟⲥⲧⲟⲗⲓⲕⲟⲥ or Ⲡⲁⲡⲁ ⲁⲑⲁⲛⲁⲥⲓⲟⲩ ⲁ̅; (c. 296–298 – 2 May 373), also called Athanasius the Great, ...

, the devil fought Anthony by afflicting him with boredom, laziness, and the phantoms of women, which he overcame by the power of prayer, providing a theme for Christian art

Christian art is sacred art which uses subjects, themes, and imagery from Christianity. Most Christian groups use or have used art to some extent, including early Christian art and architecture and Christian media.

Images of Jesus and narrative ...

. After that, he moved to one of the tombs near his native village. There it was that the ''Life'' records those strange conflicts with demons in the shape of wild beasts, who inflicted blows upon him, and sometimes left him nearly dead.

After fifteen years of this life, at the age of thirty-five, Anthony determined to withdraw from the habitations of men and retire in absolute solitude. He went into the desert to a mountain by the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

called Pispir (now Der-el-Memun), opposite Arsinoë. There he lived strictly enclosed in an old abandoned Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

fort for some 20 years. Food was thrown to him over the wall. He was at times visited by pilgrims, whom he refused to see; but gradually a number of would-be disciples established themselves in caves and in huts around the mountain. Thus a colony of ascetics was formed, who begged Anthony to come forth and be their guide in the spiritual life. Eventually, he yielded to their importunities and, about the year 305, emerged from his retreat. To the surprise of all, he appeared to be not emaciated, but healthy in mind and body. For five or six years he devoted himself to the instruction and organization of the great body of monks that had grown up around him; but then he once again withdrew into the inner desert that lay between the Nile and the Red Sea, near the shore of which he fixed his abode on a mountain (

For five or six years he devoted himself to the instruction and organization of the great body of monks that had grown up around him; but then he once again withdrew into the inner desert that lay between the Nile and the Red Sea, near the shore of which he fixed his abode on a mountain (Mount Colzim

Mount Colzim (or ''Qulzum'', ''Qalzam'', or ''Qolozum''), also known as the Inner Mountain of Saint Anthony, is a mountain in Red Sea Governorate, Egypt. It was the final residency of Anthony the Great from about AD 311, when he was 62 years of a ...

) where still stands the monastery that bears his name, Der Mar Antonios. Here he spent the last forty-five years of his life, in a seclusion, not so strict as Pispir, for he freely saw those who came to visit him, and he used to cross the desert to Pispir with considerable frequency. Amid the Diocletian Persecutions, around 311 Anthony went to Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

and was conspicuous visiting those who were imprisoned.

Father of Monks

Anthony was not the first ascetic or hermit, but he may properly be called the "Father of Monasticism" in Christianity, as he organized his disciples into a community and later, following the spread of Athanasius's hagiography, was the inspiration for similar communities throughout Egypt and elsewhere.Macarius the Great

Macarius of Egypt, ''Osios Makarios o Egyptios''; cop, ⲁⲃⲃⲁ ⲙⲁⲕⲁⲣⲓ. (c. 300 – 391) was a Christian monk and hermit. He is also known as Macarius the Elder or Macarius the Great.

Life

St. Macarius was born in Lower Egypt. ...

was a disciple of Anthony. Visitors traveled great distances to see the celebrated holy man. Anthony is said to have spoken to those of a spiritual disposition, leaving the task of addressing the more worldly visitors to Macarius. Macarius later founded a monastic community in the Scetic desert.

The fame of Anthony spread and reached Emperor Constantine

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterranea ...

, who wrote to him requesting his prayers. The brethren were pleased with the Emperor's letter, but Anthony was not overawed and wrote back exhorting the Emperor and his sons not to esteem this world but remember the next.

The stories of the meeting of Anthony and Paul of Thebes

Paul of Thebes (; , ''Paûlos ho Thēbaîos''; ; c. 227 – c. 341), commonly known as Paul the First Hermit or Paul the Anchorite, was an Egyptian saint regarded as the first Christian hermit, who was claimed to have lived alone in the deser ...

, the raven

A raven is any of several larger-bodied bird species of the genus ''Corvus''. These species do not form a single taxonomic group within the genus. There is no consistent distinction between "crows" and "ravens", common names which are assigned t ...

who brought them bread, Anthony being sent to fetch the cloak given him by "Athanasius the bishop" to bury Paul's body in, and Paul's death before he returned, are among the familiar legends of the ''Life''. However, belief in the existence of Paul seems to have existed quite independently of the ''Life''.

In 338, he left the desert temporarily to visit Alexandria to help refute the teachings of Arius

Arius (; grc-koi, Ἄρειος, ; 250 or 256 – 336) was a Cyrenaic presbyter, ascetic, and priest best known for the doctrine of Arianism. His teachings about the nature of the Godhead in Christianity, which emphasized God the Father's un ...

.

Final days

When Anthony sensed his death approaching, he commanded his disciples to give his staff toMacarius of Egypt

Macarius of Egypt, ''Osios Makarios o Egyptios''; cop, ⲁⲃⲃⲁ ⲙⲁⲕⲁⲣⲓ. (c. 300 – 391) was a Christian monk and hermit. He is also known as Macarius the Elder or Macarius the Great.

Life

St. Macarius was born in Lower Egypt. ...

, and to give one sheepskin

Sheepskin is the Hide (skin), hide of a Domestic sheep, sheep, sometimes also called lambskin. Unlike common leather, sheepskin is Tanning (leather), tanned with the Wool, fleece intact, as in a Fur, pelt.Delbridge, Arthur, "The Macquarie Dictiona ...

cloak to Athanasius of Alexandria

Athanasius I of Alexandria, ; cop, ⲡⲓⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ ⲁⲑⲁⲛⲁⲥⲓⲟⲩ ⲡⲓⲁⲡⲟⲥⲧⲟⲗⲓⲕⲟⲥ or Ⲡⲁⲡⲁ ⲁⲑⲁⲛⲁⲥⲓⲟⲩ ⲁ̅; (c. 296–298 – 2 May 373), also called Athanasius the Great, ...

and the other sheepskin cloak to Serapion of Thmuis

Serapion of Nitria, (; ) Serapion of Thmuis, also spelled Sarapion, or Serapion the Scholastic was an early Christian monk and bishop of Thmuis in Lower Egypt (modern-day Tell el-Timai), born in the 4th century. He is notable for fighting along ...

, his disciple. Anthony was interred, according to his instructions, in a grave next to his cell.

Temptation

Accounts of Anthony enduring preternatural temptation during his sojourn in the Eastern Desert of Egypt inspired the often-repeated subject of the temptation of St. Anthony in Western art and literature. Anthony is said to have faced a series of preternaturaltemptation

Temptation is a desire to engage in short-term urges for enjoyment that threatens long-term goals.Webb, J.R. (Sep 2014). Incorporating Spirituality into Psychology of temptation: Conceptualization, measurement, and clinical implications. Sp ...

s during his pilgrimage to the desert. The first to report on the temptation was his contemporary Athanasius of Alexandria

Athanasius I of Alexandria, ; cop, ⲡⲓⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ ⲁⲑⲁⲛⲁⲥⲓⲟⲩ ⲡⲓⲁⲡⲟⲥⲧⲟⲗⲓⲕⲟⲥ or Ⲡⲁⲡⲁ ⲁⲑⲁⲛⲁⲥⲓⲟⲩ ⲁ̅; (c. 296–298 – 2 May 373), also called Athanasius the Great, ...

. It is possible these events, like the paintings, are full of rich metaphor or in the case of the animals of the desert, perhaps a vision or dream. Emphasis on these stories, however, did not really begin until the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

when the psychology of the individual became of greater interest.

Some of the stories included in Anthony's biography are perpetuated now mostly in paintings, where they give an opportunity for artists to depict their more lurid or bizarre interpretations. Many artists, including Martin Schongauer

Martin Schongauer (c. 1450–53, Colmar – 2 February 1491, Breisach), also known as Martin Schön ("Martin beautiful") or Hübsch Martin ("pretty Martin") by his contemporaries, was an Alsatian engraver and painter. He was the most important ...

, Hieronymus Bosch

Hieronymus Bosch (, ; born Jheronimus van Aken ; – 9 August 1516) was a Dutch/Netherlandish painter from Brabant. He is one of the most notable representatives of the Early Netherlandish painting school. His work, generally oil on oa ...

, Dorothea Tanning

Dorothea Margaret Tanning (25 August 1910 – 31 January 2012) was an American painter, printmaker, sculptor, writer, and poet. Her early work was influenced by Surrealism.

Biography

Dorothea Tanning was born and raised in Galesburg, Illin ...

, Max Ernst

Max Ernst (2 April 1891 – 1 April 1976) was a German (naturalised American in 1948 and French in 1958) painter, sculptor, printmaker, graphic artist, and poet. A prolific artist, Ernst was a primary pioneer of the Dada movement and Surrealism ...

, Leonora Carrington

Mary Leonora Carrington (6 April 191725 May 2011) was a British-born Mexican artist, surrealist painter, and novelist. She lived most of her adult life in Mexico City and was one of the last surviving participants in the surrealist movement of ...

and Salvador Dalí

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, Marquess of Dalí of Púbol (; ; ; 11 May 190423 January 1989) was a Spanish Surrealism, surrealist artist renowned for his technical skill, precise draftsmanship, and the striking and bizarr ...

, have depicted these incidents from the life of Anthony; in prose, the tale was retold and embellished by Gustave Flaubert

Gustave Flaubert ( , , ; 12 December 1821 – 8 May 1880) was a French novelist. Highly influential, he has been considered the leading exponent of literary realism in his country. According to the literary theorist Kornelije Kvas, "in Flauber ...

in '' The Temptation of Saint Anthony''.

The satyr and the centaur

Anthony was on a journey in the desert to findPaul of Thebes

Paul of Thebes (; , ''Paûlos ho Thēbaîos''; ; c. 227 – c. 341), commonly known as Paul the First Hermit or Paul the Anchorite, was an Egyptian saint regarded as the first Christian hermit, who was claimed to have lived alone in the deser ...

, who according to his dream was a better Hermit than he.''Vitae Patrum'', Book 1a- Collected from Jerome. Ch. VI Anthony had been under the impression that he was the first person to ever dwell in the desert; however, due to the dream, Anthony was called into the desert to find his "better", Paul. On his way there, he ran into two creatures in the forms of a centaur

A centaur ( ; grc, κένταυρος, kéntauros; ), or occasionally hippocentaur, is a creature from Greek mythology with the upper body of a human and the lower body and legs of a horse.

Centaurs are thought of in many Greek myths as being ...

and a satyr

In Greek mythology, a satyr ( grc-gre, :wikt:σάτυρος, σάτυρος, sátyros, ), also known as a silenus or ''silenos'' ( grc-gre, :wikt:Σειληνός, σειληνός ), is a male List of nature deities, nature spirit with ears ...

. Although chroniclers sometimes postulated they might have been living beings, Western theology considers them to have been demon

A demon is a malevolent supernatural entity. Historically, belief in demons, or stories about demons, occurs in religion, occultism, literature, fiction, mythology, and folklore; as well as in media such as comics, video games, movies, ani ...

s.

While traveling through the desert, Anthony first found the centaur, a "creature of mingled shape, half horse half-man," whom he asked about directions. The creature tried to speak in an unintelligible language, but ultimately pointed with his hand the way desired, and then ran away and vanished from sight. It was interpreted as a demon trying to terrify him, or alternately a creature engendered by the desert.

Anthony found next the satyr, "a manikin with hooked snout, horned forehead, and extremities like goats's feet." This creature was peaceful and offered him fruits, and when Anthony asked who he was, the satyr replied, "I'm a mortal being and one of those inhabitants of the desert whom the Gentiles, deluded by various forms of error, worship under the names of Fauns

The faun (, grc, φαῦνος, ''phaunos'', ) is a half-human and half-goat mythological creature appearing in Greek and Roman mythology.

Originally fauns of Roman mythology were spirits (genii) of rustic places, lesser versions of their c ...

, Satyrs

In Greek mythology, a satyr ( grc-gre, σάτυρος, sátyros, ), also known as a silenus or ''silenos'' ( grc-gre, σειληνός ), is a male nature spirit with ears and a tail resembling those of a horse, as well as a permanent, exag ...

, and Incubi

An incubus is a demon in male form in folklore that seeks to have sexual intercourse with sleeping women; the corresponding spirit in female form is called a succubus. In medieval Europe, union with an incubus was supposed by some to result in ...

. I am sent to represent my tribe. We pray you in our behalf to entreat the favor of your Lord and ours, who, we have learnt, came once to save the world, and 'whose sound has gone forth into all the earth.'" Upon hearing this, Anthony was overjoyed and rejoiced over the glory of Christ. He condemned the city of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

for worshipping monsters instead of God while beasts like the satyr spoke about Christ.

Silver and gold

Another time Anthony was travelling in the desert and found a plate of silver coins in his path.Demons in the cave

Once, Anthony tried to hide in a cave to escape the demons that plagued him. There were so many little demons in the cave though, that Anthony's servant had to carry him out because they had beaten him to death. When the hermits were gathered to Anthony's corpse to mourn his death, Anthony was revived. He demanded that his servants take him back to that cave where the demons had beaten him. When he got there he called out to the demons, and they came back as wild beasts to rip him to shreds. All of a sudden a bright light flashed, and the demons ran away. Anthony knew that the light must have come from God, and he asked God where he was before when the demons attacked him. God replied, "I was here but I would see and abide to see thy battle, and because thou hast mainly fought and well maintained thy battle, I shall make thy name to be spread through all the world."Veneration

Anthony had been secretly buried on the mountain-top where he had chosen to live. His remains were reportedly discovered in 361, and transferred to

Anthony had been secretly buried on the mountain-top where he had chosen to live. His remains were reportedly discovered in 361, and transferred to Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

. Some time later, they were taken from Alexandria to Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, so that they might escape the destruction being perpetrated by invading Saracen

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

Saracen ( ) was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek and Latin writings, to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Romans as Arabia Pe ...

s. In the eleventh century, the Byzantine emperor

This is a list of the Byzantine emperors from the foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD, which marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, to its fall to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as le ...

gave them to the French Count

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility. Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty''. New York: ...

Jocelin. Jocelin had them transferred to La-Motte-Saint-Didier, later renamed. There, Jocelin undertook to build a church to house the remains, but died before the church was even started. The building was finally erected in 1297 and became a centre of veneration and pilgrimage, known as Saint-Antoine-l'Abbaye

Saint-Antoine-l'Abbaye (), also Saint-Antoine-en-Viennois, is a commune in the Isère department in southeastern France. On 31 December 2015, the former commune of Dionay was merged into Saint-Antoine-l'Abbaye.ergotism, which became known as "St. Anthony's Fire". He was credited by two local noblemen of assisting them in recovery from the disease. They then founded the  Veneration of Anthony in the East is more restrained. There are comparatively few icons and paintings of him. He is, however, regarded as the "first master of the desert and the pinnacle of holy monks", and there are monastic communities of the Maronite, Chaldean, and Orthodox churches which state that they follow his monastic rule. During the

Veneration of Anthony in the East is more restrained. There are comparatively few icons and paintings of him. He is, however, regarded as the "first master of the desert and the pinnacle of holy monks", and there are monastic communities of the Maronite, Chaldean, and Orthodox churches which state that they follow his monastic rule. During the

"Anthony Adverse", TCM

/ref> The novel ''The Einstein Prophecy'' by Robert Masello revolves around the recovery of Saint Anthony's

"Spiritual Considerations on the Life of Saint Antony the Great"

is a manuscript, from 1864, in Arabic, that is a translation of a Latin work about the life of Saint Anthony

at th

Christian Iconography

website

from Caxton's translation of the Golden Legend

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Anthony The Great 356 deaths 3rd-century Egyptian people 4th-century Egyptian people Saints from Roman Egypt Egyptian hermits Egyptian centenarians Egyptian Christian monks 3rd-century Christian saints 4th-century Christian saints 3rd-century Romans 4th-century Romans 4th-century Christian theologians Angelic visionaries 4th-century Christian monks 3rd-century Christian monks 4th-century writers Antonii 250s births Anglican saints Men centenarians Diocletianic Persecution Desert Fathers Philokalia

Hospital Brothers of St. Anthony

The Hospital Brothers of Saint Anthony, Order of Saint Anthony or Canons Regular of Saint Anthony of Vienne (''Canonici Regulares Sancti Antonii'', or CRSAnt), also Antonines or Antonites, were a Roman Catholic congregation founded in c. 1095, wi ...

in honor of him, who specialized in nursing the victims of skin diseases.

He is venerated especially by the Order of Saint Paul the First Hermit

The Order of Saint Paul the First Hermit ( lat, Ordo Fratrum Sancti Pauli Primi Eremitæ; abbreviated OSPPE), commonly called the Pauline Fathers, is a monastic order of the Roman Catholic Church founded in Hungary during the 13th century.

Thi ...

for his close association with St. Paul of Thebes

Paul of Thebes (; , ''Paûlos ho Thēbaîos''; ; c. 227 – c. 341), commonly known as Paul the First Hermit or Paul the Anchorite, was an Egyptian saint regarded as the first Christian hermit, who was claimed to have lived alone in the deser ...

after whom they take their name. In the ''Life of St. Paul the First Hermit'', by St. Jerome, it is recorded that it was St. Anthony that found St. Paul towards the end of his life and without whom it is doubtful he would be known.

Veneration of Anthony in the East is more restrained. There are comparatively few icons and paintings of him. He is, however, regarded as the "first master of the desert and the pinnacle of holy monks", and there are monastic communities of the Maronite, Chaldean, and Orthodox churches which state that they follow his monastic rule. During the

Veneration of Anthony in the East is more restrained. There are comparatively few icons and paintings of him. He is, however, regarded as the "first master of the desert and the pinnacle of holy monks", and there are monastic communities of the Maronite, Chaldean, and Orthodox churches which state that they follow his monastic rule. During the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

, Anthony, along with Quirinus of Neuss

Quirinus of Neuss (german: Quirin, Quirinus), sometimes called ''Quirinus of Rome'' (which is the name shared by Saint Quirinus of Tegernsee, another martyr) is venerated as a martyr and saint of the Catholic Church, Catholic and Eastern Orthodox ...

, Cornelius and Hubertus

Hubertus or Hubert ( 656 – 30 May 727 A.D.) was a Christian saint who became the first bishop of Liège in 708 A.D. He is the patron saint of hunters, mathematicians, opticians and metalworkers. Known as the "Apostle of the Ardennes", he was ...

, was venerated as one of the Four Holy Marshals

The Four Holy Marshals (''Vier Marschälle Gottes'' or just ''Vier Marschälle'') are four saints venerated in the Rhineland, especially at Cologne, Liège, Aachen, and Eifel. They are conceived as standing particularly close to throne of Go ...

(''Vier Marschälle Gottes'') in the Rhineland

The Rhineland (german: Rheinland; french: Rhénanie; nl, Rijnland; ksh, Rhingland; Latinised name: ''Rhenania'') is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly its middle section.

Term

Historically, the Rhinelands ...

.

Anthony is remembered

Recall in memory refers to the mental process of retrieval of information from the past. Along with encoding (memory), encoding and storage (memory), storage, it is one of the three core processes of memory. There are three main types of recall: ...

in the Anglican Communion

The Anglican Communion is the third largest Christian communion after the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches. Founded in 1867 in London, the communion has more than 85 million members within the Church of England and other ...

with a Lesser Festival Lesser Festivals are a type of observance in the Anglican Communion, including the Church of England, considered to be less significant than a Principal Feast, Principal Holy Day, or Festival, but more significant than a Commemoration. Whereas Princ ...

on 17 January

Events Pre-1600

*38 BC – Octavian divorces his wife Scribonia and marries Livia Drusilla, ending the fragile peace between the Second Triumvirate and Sextus Pompey.

* 1362 – Saint Marcellus' flood kills at least 25,000 people on ...

.

Legacy

Though Anthony himself did not organize or create a monastery, a community grew around him based on his example of living anascetic

Asceticism (; from the el, ἄσκησις, áskesis, exercise', 'training) is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from sensual pleasures, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their p ...

and isolated life. Athanasius' biography helped propagate Anthony's ideals. Athanasius writes, "For monks, the life of Anthony is a sufficient example of asceticism

Asceticism (; from the el, ἄσκησις, áskesis, exercise', 'training) is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from sensual pleasures, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their p ...

.

His story influenced the conversion of Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Af ...

and John Chrysostom

John Chrysostom (; gr, Ἰωάννης ὁ Χρυσόστομος; 14 September 407) was an important Early Church Father who served as archbishop of Constantinople. He is known for his homilies, preaching and public speaking, his denunciat ...

.

Coptic literature

Examples of purelyCoptic literature

Coptic literature is the body of writings in the Coptic language of Egypt, the last stage of the indigenous Egyptian language. It is written in the Coptic alphabet. The study of the Coptic language and literature is called Coptology.

Definition

...

are the works of Anthony and Pachomius

Pachomius (; el, Παχώμιος ''Pakhomios''; ; c. 292 – 9 May 348 AD), also known as Saint Pachomius the Great, is generally recognized as the founder of Christian cenobitic monasticism. Copts, Coptic churches celebrate his feast day on ...

, who only spoke Coptic, and the sermons and preachings of Shenouda the Archmandrite, who chose to only write in Coptic. The earliest original writings in Coptic language

Coptic (Bohairic Coptic: , ) is a language family of closely related dialects, representing the most recent developments of the Egyptian language, and historically spoken by the Copts, starting from the third-century AD in Roman Egypt. Coptic ...

were the letters by Anthony. During the 3rd and 4th centuries many ecclesiastics and monks wrote in Coptic.

In popular literature

The main character in theHervey Allen

William Hervey Allen Jr. (December 8, 1889 – December 28, 1949) was an American educator, poet, and writer. He is best known for his work ''Anthony Adverse (novel), Anthony Adverse'' (made into a Anthony Adverse, 1936 movie of the same name), r ...

novel ''Anthony Adverse

''Anthony Adverse'' is a 1936 American epic historical drama film directed by Mervyn LeRoy and starring Fredric March and Olivia de Havilland. The screenplay by Sheridan Gibney draws elements of its plot from eight of the nine books in Herve ...

'', and the 1936 film of the same name, is an abandoned child who is placed in a foundling wheel

A baby hatch or baby box is a place where people (typically mothers) can bring babies, usually newborn, and abandon them anonymously in a safe place to be found and cared for. This kind of arrangement was common in the Middle Ages and in the 18t ...

on the saint's feast day, and given the name Anthony in his honor./ref> The novel ''The Einstein Prophecy'' by Robert Masello revolves around the recovery of Saint Anthony's

ossuary

An ossuary is a chest, box, building, well, or site made to serve as the final resting place of human skeletal remains. They are frequently used where burial space is scarce. A body is first buried in a temporary grave, then after some years the ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. Much of the mythology surrounding Saint Anthony's time in the Sahara

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

desert is used as the basis for the conflict the protagonists face after opening the ossuary.

See also

*Mount Colzim

Mount Colzim (or ''Qulzum'', ''Qalzam'', or ''Qolozum''), also known as the Inner Mountain of Saint Anthony, is a mountain in Red Sea Governorate, Egypt. It was the final residency of Anthony the Great from about AD 311, when he was 62 years of a ...

, Anthony's "Inner mountain"

* Coptic Saints

Early church historians, writers, and fathers testified to the numerous Copt martyrs. Tertullian, 3rd century North African lawyer wrote "If the martyrs of the whole world were put on one arm of the balance and the martyrs of Egypt on the other, ...

* Abba Anoub of Scetis

* Chariton the Confessor

Chariton the Confessor (Greek: Χαρίτων; mid-3rd century, Iconium, Asia Minor – c. 350, Judaean desert) was a Christian saint. His remembrance day is September 28.

Life Sources

We know about his ''vita'' from the 6th-century "Life of Cha ...

(mid-3rd century – c. 350), contemporary monk in the Judaean desert

* Desert Fathers

The Desert Fathers or Desert Monks were early Christian hermits and ascetics, who lived primarily in the Scetes desert of the Roman province of Egypt

, conventional_long_name = Roman Egypt

, common_name = Egypt

, subdivision = Province

, na ...

and Desert Mothers

Desert Mothers is a neologism, coined in feminist theology in analogy to Desert Fathers, for the ''ammas'' or female Christian ascetics living in the desert of Egypt, Palestine, and Syria in the 4th and 5th centuries AD. They typically lived in ...

, early Christian hermits, ascetics, and monks who lived mainly in the Scetes desert of Egypt beginning around the third century AD

* Abba Or of Nitria

* Hilarion

Hilarion the Great (291–371) was an anchorite who spent most of his life in the desert according to the example of Anthony the Great (c. 251–356). While St Anthony is considered to have established Christian monasticism in the Egyptian d ...

(291–371), anchorite and saint considered by some to be the founder of Palestinian monasticism

* Monastery of Saint Anthony

The Monastery of Saint Anthony is a Coptic Orthodox monastery standing in an oasis in the Eastern Desert of Egypt, in the southern part of the Suez Governorate. Hidden deep in the Red Sea Mountains, it is located southeast of Cairo. The Monas ...

, Egypt

* Pachomius the Great

Pachomius (; el, Παχώμιος ''Pakhomios''; ; c. 292 – 9 May 348 AD), also known as Saint Pachomius the Great, is generally recognized as the founder of Christian cenobitic monasticism. Coptic churches celebrate his feast day on 9 May, ...

(c. 292 – 348), Egyptian saint generally recognized as the founder of Christian cenobitic monasticism

* Patron saints of ailments, illness and dangers

This is a list of patron saints of ailments, illnesses, and dangers.

A

* Abd-al-Masih – sterile women (in Syria)

*Abel of Reims – patron of the blind and the lame

* Abhai – venomous reptiles

*Agapitus of Palestrina – invoked against c ...

* Paul of Thebes

Paul of Thebes (; , ''Paûlos ho Thēbaîos''; ; c. 227 – c. 341), commonly known as Paul the First Hermit or Paul the Anchorite, was an Egyptian saint regarded as the first Christian hermit, who was claimed to have lived alone in the deser ...

(c. 226/7 – c. 341), known as "Paul, the First Hermit", who preceded both Anthony and Chariton

* St. Anthony Hall

St. Anthony Hall or the Fraternity of Delta Psi is an American fraternity and literary society. Its first chapter was founded at Columbia University on , the Calendar of saints, feast day of Anthony the Great, Saint Anthony the Great. The frater ...

, American fraternity and literary society

* Saint Anthony the Great, patron saint archive

* Serapion of Nitria

Serapion of Nitria or Serapion of Thmuis (; ) was an early Christian monasticism, Christian monk in Nitria (monastic site), Nitria, Egypt (region), Lower Egypt, born in the third century AD. He was a companion of Anthony the Great, the abbot of ...

, disciple of Anthony

* Pitirim of Porphyry, disciple of Anthony

Notes

References

* *External links

"Spiritual Considerations on the Life of Saint Antony the Great"

is a manuscript, from 1864, in Arabic, that is a translation of a Latin work about the life of Saint Anthony

at th

Christian Iconography

website

from Caxton's translation of the Golden Legend

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Anthony The Great 356 deaths 3rd-century Egyptian people 4th-century Egyptian people Saints from Roman Egypt Egyptian hermits Egyptian centenarians Egyptian Christian monks 3rd-century Christian saints 4th-century Christian saints 3rd-century Romans 4th-century Romans 4th-century Christian theologians Angelic visionaries 4th-century Christian monks 3rd-century Christian monks 4th-century writers Antonii 250s births Anglican saints Men centenarians Diocletianic Persecution Desert Fathers Philokalia