Anti-Scottish Sentiment on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anti-Scottish sentiment is disdain, discrimination, or hatred for

Accepted as fact with no evidence, such ideas were encouraged and printed as seen in ''

Accepted as fact with no evidence, such ideas were encouraged and printed as seen in ''

Stereotypes of Highland cannibalism lasted till the mid-18th century and were embraced by Lowland Scots Presbyterian and English political and anti- Jacobite propaganda, in reaction to a series of Jacobite uprisings, rebellions, in the British Isles between 1688 and 1746. The Jacobite uprisings themselves in reaction to the

Stereotypes of Highland cannibalism lasted till the mid-18th century and were embraced by Lowland Scots Presbyterian and English political and anti- Jacobite propaganda, in reaction to a series of Jacobite uprisings, rebellions, in the British Isles between 1688 and 1746. The Jacobite uprisings themselves in reaction to the

James Michie, gentle genius

Boris Johnson dubbed Michie "one of the most distinguished poets and translators of the 20th century" and referred to "Friendly Fire" as an example of how he wrote "whimsically, sometimes with bite." The term

Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

, the Scots or Scottish culture

The culture of Scotland refers to the patterns of human activity and symbolism associated with Scotland and the Scottish people. The Scottish flag is blue with a white saltire, and represents the cross of Saint Andrew.

Scots law

Scotland retain ...

. It may also include the persecution or oppression of the Scottish people as an ethnic group, or nation

A nation is a community of people formed on the basis of a combination of shared features such as language, history, ethnicity, culture and/or society. A nation is thus the collective identity of a group of people understood as defined by those ...

. It can also be referred to as Scotophobia or Albaphobia. See antonym Anglophobia.

Middle Ages

Much of the negative literature of the Middle Ages drew heavily on the writings fromGreek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

antiquity. The writings of Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

in particular dominated concepts of Scotland till the Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the Periodization, period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Eur ...

and drew on stereotypes perpetuating fictitious, as well as satirical accounts of the Kingdom of the Scots. The English Church and the propaganda of royal writs from 1337 to 1453 encouraged a barbarous image of the kingdom as it allied with England's enemy, the Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France ( fro, Reaume de France; frm, Royaulme de France; french: link=yes, Royaume de France) is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the medieval and early modern period. ...

, during the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a series of armed conflicts between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France during the Late Middle Ages. It originated from disputed claims to the French Crown, ...

. Medieval authors seldom visited Scotland but called on such accounts as "''common knowledge''", influencing the works of Boece's "''Scotorum Historiae''" (Paris 1527) and Camden's "''Brittania''" (London 1586) plagiarising and perpetuating negative attitudes. In the 16th century Scotland and particularly the Gaelic

Gaelic is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". As a noun it refers to the group of languages spoken by the Gaels, or to any one of the languages individually. Gaelic languages are spoken in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, and Ca ...

speaking Highlands

Highland is a broad term for areas of higher elevation, such as a mountain range or mountainous plateau.

Highland, Highlands, or The Highlands, may also refer to:

Places Albania

* Dukagjin Highlands

Armenia

* Armenian Highlands

Australia

*Sou ...

were characterised as lawless, savage and filled with wild Scots. As seen in Camden's account to promote an image of the nation as a wild and barbarous people:

They drank the bloud loodout of wounds of the slain: they establish themselves, by drinking one anothers bloud loodand suppose the great number of slaughters they commit, the more honour they winne inand so did theCamden's accounts were modified to compare the Highland Scots to the inhabitants of Ireland.''Travels to Terra Incognita: The Scottish Highlands and Hebrides in Early Modern Travellers' Accounts c. 1600 to 1800''. Martin Rackwitz. Waxmann Verlag 2007. p33, p94 Negative stereotypes flourished and by 1634, Austrian Martin Zeiller linked the origins of the Scots to the Scythians and in particular the Highlander to theScythians The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an Ancient Iranian peoples, ancient Eastern Iranian languages, Eastern * : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved f ...in old time. To this we adde ddthat these wild Scots, like as the Scythians, had for their principall weapons, bowes and arrows. Camden (1586)

Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe ...

based on their wild and Gothic-like appearance. Quoting the 4th-century Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus

Ammianus Marcellinus (occasionally Anglicisation, anglicised as Ammian) (born , died 400) was a Roman soldier and historian who wrote the penultimate major historical account surviving from Ancient history, antiquity (preceding Procopius). His w ...

, he describes the Scots as descendants of the tribes of the British Isles who were unruly trouble makers. With a limited amount of information, the Medieval geographer embellished such tales, including, less favourable assertions that the ancestors of Scottish people were cannibals. A spurious accusation proposed by Saint Jerome

Jerome (; la, Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was a Christian priest, confessor, theologian, and historian; he is comm ...

's tales of Scythian atrocities was adapted to lay claims as evidence of cannibalism in Scotland. Despite the fact that there is no evidence of the ancestors of the Scots in ancient Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

, moreover St. Jerome's text was a mistranslation of Attacotti

The Attacotti (variously spelled ''Atticoti'', ''Attacoti'', ''Atecotti'', ''Atticotti'', ''Atecutti'', etc.) were a people who despoiled Roman Britain between 364 and 368, along with the Scoti, Picts, Saxons, Roman military deserters and the i ...

, another tribe in Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the period in classical antiquity when large parts of the island of Great Britain were under occupation by the Roman Empire. The occupation lasted from AD 43 to AD 410. During that time, the territory conquered was ...

, the myth of cannibalism was attributed to the people of Scotland:

What shall I t. Jeromesay of other nations – how when I was in Gaul as a youth I saw the Scots, a British race, eating human flesh, and how, when these men came upon the forests upon herds of swine and sheep, and cattle, they would cut off the buttocks of the shepherds and paps of the woman and hold these for their greatest delicasy.

Accepted as fact with no evidence, such ideas were encouraged and printed as seen in ''

Accepted as fact with no evidence, such ideas were encouraged and printed as seen in ''De Situ Britanniae

''The Description of Britain'', also known by its Latin name ' ("On the Situation of Britain"), was a literary forgery perpetrated by Charles Bertram on the historians of England. It purported to be a 15th-century manuscript by the English monk R ...

'' a fictitious account of the peoples and places of Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the period in classical antiquity when large parts of the island of Great Britain were under occupation by the Roman Empire. The occupation lasted from AD 43 to AD 410. During that time, the territory conquered was ...

. It was published in 1757, after having been made available in London in 1749. Accepted as genuine for more than one hundred years, it was virtually the only source of information for northern Britain (i.e., modern Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

) for the time period, and historians eagerly incorporated its spurious information into their own accounts of history. The Attacotti's homeland was specified as just north of the Firth of Clyde

The Firth of Clyde is the mouth of the River Clyde. It is located on the west coast of Scotland and constitutes the deepest coastal waters in the British Isles (it is 164 metres deep at its deepest). The firth is sheltered from the Atlantic ...

, near southern Loch Lomond

Loch Lomond (; gd, Loch Laomainn - 'Lake of the Elms'Richens, R. J. (1984) ''Elm'', Cambridge University Press.) is a freshwater Scottish loch which crosses the Highland Boundary Fault, often considered the boundary between the lowlands of Ce ...

, in the region of Dunbartonshire

Dunbartonshire ( gd, Siorrachd Dhùn Breatann) or the County of Dumbarton is a historic county, lieutenancy area and registration county in the west central Lowlands of Scotland lying to the north of the River Clyde. Dunbartonshire borders P ...

. This information was combined with legitimate historical mentions of the Attacotti to produce inaccurate histories and to make baseless conjectures. For example, Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon (; 8 May 173716 January 1794) was an English historian, writer, and member of parliament. His most important work, ''The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'', published in six volumes between 1776 and 1788, is k ...

combined ''De Situ Britanniae'' with St. Jerome's description of the Attacotti by musing on the possibility that a 'race of cannibals' had once dwelt in the neighbourhood of Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

.

These views were echoed in the works of Dutch, French and German authors. Nicolaus Hieronymus Gundling proposed that the exotic appearance and cannibalism of the Scottish people made them akin to the savages of Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

. Even as late as the mid-18th century, German authors likened Scotland and its ancient population to the exotic tribes of the South Seas. With the close political ties of the Franco-Scottish alliance in the late Medieval period, before William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's ''Macbeth

''Macbeth'' (, full title ''The Tragedie of Macbeth'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It is thought to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the damaging physical and psychological effects of political ambition on those w ...

'', English Elizabethan theatre dramatised the Scots and Scottish culture as comical, alien, dangerous and uncivilised. In comparison to the manner of Frenchmen who spoke a form of English,''Macbeth'' by William Shakespeare. A. R. Braunmuller p9 Cambridge University Press, 1997 Scots were used in material for comedies; including Robert Greene's James IV in a fictitious English invasion of Scotland satirising the long Medieval wars with Scotland. English fears and hatred were deeply rooted in the contemporary fabric of society, drawing upon stereotypes as seen in Raphael Holinshed

Raphael Holinshed ( – before 24 April 1582) was an English chronicler, who was most famous for his work on ''The Chronicles of England, Scotlande, and Irelande'', commonly known as ''Holinshed's Chronicles''. It was the "first complete printe ...

's ''Chronicles

Chronicles may refer to:

* ''Books of Chronicles'', in the Bible

* Chronicle, chronological histories

* ''The Chronicles of Narnia'', a novel series by C. S. Lewis

* ''Holinshed's Chronicles'', the collected works of Raphael Holinshed

* '' The Idh ...

" ''and politically edged material such as George Chapman

George Chapman (Hitchin, Hertfordshire, – London, 12 May 1634) was an English dramatist, translator and poet. He was a classical scholar whose work shows the influence of Stoicism. Chapman has been speculated to be the Rival Poet of Shak ...

's ''Eastward Hoe

''Eastward Hoe'' or ''Eastward Ho!'' is an early Jacobean-era stage play written by George Chapman, Ben Jonson and John Marston. The play was first performed at the Blackfriars Theatre by a company of boy actors known as the Children of the ...

'' in 1605, offended King James with its anti-Scottish satire, resulting in the imprisonment of the playwright. Despite this, the play was never banned or suppressed. Authors such as Claude Jordan de Colombier in 1697 plagiarised earlier works, Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also called the Catholic Reformation () or the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation. It began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) a ...

propaganda associated the Scots and particularly Highland Gaelic-speakers as barbarians from the north who wore nothing but animal skins. Confirming old stereotypes relating back to Roman and Greek philosophers in the idea that "dark forces" from northern Europe (soldiers from Denmark, Sweden, Netherlands, France and Scotland) acquired a reputation as fierce warriors. With Lowland

Upland and lowland are conditional descriptions of a plain based on elevation above sea level. In studies of the ecology of freshwater rivers, habitats are classified as upland or lowland.

Definitions

Upland and lowland are portions of ...

soldiers along the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

and Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

, as well as Highland

Highlands or uplands are areas of high elevation such as a mountainous region, elevated mountainous plateau or high hills. Generally speaking, upland (or uplands) refers to ranges of hills, typically from up to while highland (or highlands) is ...

mercenaries wearing the distinctive Scottish kilt

A kilt ( gd, fèileadh ; Irish: ''féileadh'') is a garment resembling a wrap-around knee-length skirt, made of twill woven worsted wool with heavy pleats at the sides and back and traditionally a tartan pattern. Originating in the Scottish Hi ...

, became synonymous with that of wild, rough and fierce fighting men.

However, the fact that Scots had married into every royal house in Europe who had also married into the Scottish royal house indicates that the supposed anti-Scottish sentiment there has been exaggerated as opposed to in England where the wars and raids in Northern England increased anti-Scottish sentiment. An increase in the English anti-Scottish sentiments after the Jacobite uprisings and the anti-Scottish bills of parliament are clearly shown in comments by leaders in English such as Samuel Johnson, whose anti-Scottish remarks such as that "in those times nothing had been written in the Earse .e. Scots Gaeliclanguage" is well known.

Anti-Highlander and anti-Jacobite sentiment

Stereotypes of Highland cannibalism lasted till the mid-18th century and were embraced by Lowland Scots Presbyterian and English political and anti- Jacobite propaganda, in reaction to a series of Jacobite uprisings, rebellions, in the British Isles between 1688 and 1746. The Jacobite uprisings themselves in reaction to the

Stereotypes of Highland cannibalism lasted till the mid-18th century and were embraced by Lowland Scots Presbyterian and English political and anti- Jacobite propaganda, in reaction to a series of Jacobite uprisings, rebellions, in the British Isles between 1688 and 1746. The Jacobite uprisings themselves in reaction to the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

of 1688, were aimed at returning James VII of Scotland and II of England, and later his descendants of the House of Stuart

The House of Stuart, originally spelt Stewart, was a royal house of Scotland, England, Ireland and later Great Britain. The family name comes from the office of High Steward of Scotland, which had been held by the family progenitor Walter fi ...

. Anti-Jacobite predominantly anti-Highland propaganda of the 1720s includes publications such as the London ''Newgate Calendar

''The Newgate Calendar'', subtitled ''The Malefactors' Bloody Register'', was a popular work of improving literature in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Originally a monthly bulletin of executions, produced by the Keeper of Newgate Prison in Lo ...

'' a popular monthly bulletin of executions, produced by the keeper of Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey Street just inside the City of London, England, originally at the site of Newgate, a gate in the Roman London Wall. Built in the 12th century and demolished in 1904, t ...

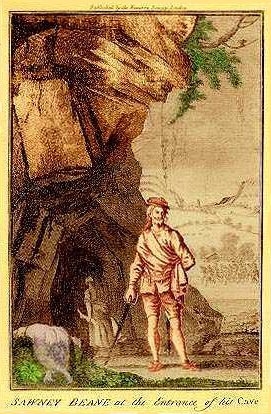

in London. One Newgate publication created the legend of Sawney Bean

Alexander "Sawney" Bean was said to be the head of a 45-member clan in Scotland in the 16th century that murdered and cannibalized over 1,000 people in 25 years. According to legend, Bean and his clan members were eventually caught by a search ...

, the head of a forty-eight strong clan of incest

Incest ( ) is human sexual activity between family members or close relatives. This typically includes sexual activity between people in consanguinity (blood relations), and sometimes those related by affinity (marriage or stepfamily), adoption ...

ual, lawless and cannibalistic family in Galloway

Galloway ( ; sco, Gallowa; la, Gallovidia) is a region in southwestern Scotland comprising the historic counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire. It is administered as part of the council area of Dumfries and Galloway.

A native or i ...

. Although based on fiction, the family were reported by the Calendar to have murdered and cannibalised over one thousand victims. Along with the Bible and John Bunyan

John Bunyan (; baptised 30 November 162831 August 1688) was an English writer and Puritan preacher best remembered as the author of the Christian allegory ''The Pilgrim's Progress,'' which also became an influential literary model. In addition ...

's ''The Pilgrim's Progress

''The Pilgrim's Progress from This World, to That Which Is to Come'' is a 1678 Christian allegory written by John Bunyan. It is regarded as one of the most significant works of theological fiction in English literature and a progenitor of ...

'', the Calendar was famously in the top three works most likely to be found in the average home and the Calendar's title was appropriated by other publications, who put out biographical chapbook

A chapbook is a small publication of up to about 40 pages, sometimes bound with a saddle stitch.

In early modern Europe a chapbook was a type of printed street literature. Produced cheaply, chapbooks were commonly small, paper-covered bookle ...

s. With the intent to create a work of fiction to demonstrate the superiority of the Protestant mercantile establishment in contrast to the 'savage pro-Jacobite uncivilised Highland Gaels'.

From 1701 to 1720 a sustained Whig campaign of anti-Jacobite pamphleteering across Britain and Ireland sought to halt Jacobitism as a political force and undermine the claim of James II and VII to the British throne. In 1705 Lowland Scots Protestant Whig politicians in the Scottish parliament voted to sustain a status quo and to award financial incentives of £4,800 to each writer having served the interests of the nation.Steele. M. (1981) ''Anti-Jacobite Pamphleteering, 1701 – 1720'' Such measures had the opposite effect and furthered the Scots towards the cause, enabling Jacobitism to flourish as a sustaining political presence in Scotland. Pro-Jacobite writings and pamphleteers e.g. Walter Harries and William Sexton were liable to imprisonment of for producing in the eyes of the government seditious

Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that tends toward rebellion against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent toward, or insurrection against, establ ...

or scurrilous tracts and all copies or works were seized or destroyed. Anti-Jacobite Pamphleteering, as an example ''An Address to All True Englishmen'' routed a sustained propaganda war with Scotland's pro-Stuart supporters ensued and British Whig campaigners pushed a pro-Saxon and the anti-Highlander nature of Williamite satire resulting in a backlash by pro-Jacobite pamphleteers.

From 1720 Lowland Scots Presbyterian Whiggish literature sought to remove the Highland Jacobite, being beyond the pale, or an enemy of John Bull

John Bull is a national personification of the United Kingdom in general and England in particular, especially in political cartoons and similar graphic works. He is usually depicted as a stout, middle-aged, country-dwelling, jolly and matter- ...

or a unified Britain and Ireland as seen in Thomas Page's ''The Use of the Highland Broadsword'' published in 1746."Contextualising Western Martial Arts The case of Thomas Page's The Use of the Highland Broadsword". 2007 By Bethan Jenkins cited in http://www.sirwilliamhope.org/Library/Articles/Jenkins/Contextualising.php Propaganda of the time included the minting of anti-Jacobite or anti-Highlander medals, and political cartoons to promote the Highland Scots as a barbaric and backward people,''The myth of the Jacobite clans'' by Murray Pittock p9 similar in style to the 19th-century depiction of the Irish as being backward or barbaric, in Lowland Scottish publications such as ''The Economist

''The Economist'' is a British weekly newspaper printed in demitab format and published digitally. It focuses on current affairs, international business, politics, technology, and culture. Based in London, the newspaper is owned by The Econo ...

''. Plays like William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's Scottish play ''Macbeth'', was popularised and considered a pro-British, pro- Hanoverian and anti- Jacobite play. Prints such as ''Sawney in The Boghouse'', itself a reference to the tale of Sawney Bean, depicted the Highland Scots as too stupid to use a lavatory and gave a particularly 18th-century edge to traditional depictions of cannibalism.''The myth of the Jacobite clans'' by Murray Pittock p10 The Highland Scots people were promoted as brutish thugs, figures of ridicule and no match for the "civilised" Lowland Scots supporters of the Protestant Hanovarians. They were feminised as a parody of the female disguise used by Bonny Prince Charlie in his escape, and as savage warriors that needed the guiding hand of the industrious Lowland Scots Protestants to render them civilised.

Depictions included the Highland Scots Jacobites as ill-dressed and ill-fed, loutish and verminous usually in league with the French''The myth of the Jacobite clans'' by Murray Pittock as can be seen in William Hogarth

William Hogarth (; 10 November 1697 – 26 October 1764) was an English painter, engraver, pictorial satirist, social critic, editorial cartoonist and occasional writer on art. His work ranges from realistic portraiture to comic strip-like s ...

's 1748 painting The Gate of Calais

''The Gate of Calais'' or ''O, the Roast Beef of Old England'' is a 1748 painting by William Hogarth, reproduced as a print from an engraving the next year. Hogarth produced the painting directly after his return from France, where he had been ...

with a Highlander exile sits slumped against the wall, his strength sapped by the poor French fare – a raw onion and a crust of bread. Political cartoons in 1762 depict the Prime Minister, Lord Bute (accused of being a Jacobite sympathiser), as a poor John Bull

John Bull is a national personification of the United Kingdom in general and England in particular, especially in political cartoons and similar graphic works. He is usually depicted as a stout, middle-aged, country-dwelling, jolly and matter- ...

depicted with a bulls head with crooked horns ridden by Jacobite Scots taking bribes from a French monkey Anti- Jacobite sentiment was captured in a verse appended to various songs, including in its original form as an anti-Jacobite song Ye Jacobites By Name, God save the King

"God Save the King" is the national anthem, national and/or royal anthem of the United Kingdom, most of the Commonwealth realms, their territories, and the British Crown Dependencies. The author of the tune is unknown and it may originate in ...

with a prayer for the success of Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, ordinarily senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army and as such few persons are appointed to it. It is considered as ...

George Wade

Field Marshal George Wade (1673 – 14 March 1748) was a British Army officer who served in the Nine Years' War, War of the Spanish Succession, Jacobite rising of 1715 and War of the Quadruple Alliance before leading the construction of bar ...

's army which attained some short-term use debatably in the late 18th century. This song was widely adopted and was to become the national anthem of Britain now known as "God Save the Queen

"God Save the King" is the national and/or royal anthem of the United Kingdom, most of the Commonwealth realms, their territories, and the British Crown Dependencies. The author of the tune is unknown and it may originate in plainchant, bu ...

" (but never since sung with that verse).

:Lord, grant that Marshal Wade,

:May by thy mighty aid,

:Victory bring.

:May he sedition hush,

:And like a torrent rush,

:Rebellious Scots to crush,

:God save the King.

The 1837 article and other sources make it clear that this verse was not used soon after 1745, and certainly before the song became accepted as the British national anthem in the 1780s and 1790s. On the opposing side, Jacobite beliefs were demonstrated in an alternative verse used during the same period, attacking Lowland Scots Presbyterianism:

: God bless the prince, I pray,

: God bless the prince, I pray,

: Charlie I mean;

: That Scotland we may see

: Freed from vile Presbyt'ry,

: Both George

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Presid ...

and his Feckie,

: Ever so, Amen.

Modern day

In 2007 a number of Scottish MPs warned of increasing anti-Scottish sentiment in England, citing the increased tension overDevolution

Devolution is the statutory delegation of powers from the central government of a sovereign state to govern at a subnational level, such as a regional or local level. It is a form of administrative decentralization. Devolved territories h ...

, the West Lothian question

The West Lothian question, also known as the English question, is a political issue in the United Kingdom. It concerns the question of whether MPs from Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales who sit in the House of Commons should be able to vote ...

and the Barnett formula

The Barnett formula is a mechanism used by the Treasury in the United Kingdom to automatically adjust the amounts of public expenditure allocated to Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales to reflect changes in spending levels allocated to publi ...

as causes.

There have been a number of attacks on Scots in England in recent years. In 2004 a Scottish former soldier was attacked by a gang of children and teenagers with bricks and bats, allegedly for having a Scottish accent. In Aspatria, Cumbria, a group of Scottish schoolgirls say they received anti-Scottish taunts and foul language from a group of teenage girls during a carnival parade. An English football supporter was banned for life for shouting "Kill all the Jocks" before attacking Scottish football fans. One Scottish woman says she was forced to move from her home in England because of anti-Scottish feeling, while another had a haggis thrown through her front window. In 2008 a student nurse from London was fined for assault and hurling anti-Scottish abuse at police while drunk during the T in the Park

T in the Park festival was a major Scottish music festival that was held annually from 1994 to 2016. It was named after its main sponsor, Tennents. The event was held at Strathclyde Park, Lanarkshire, until 1996. It then moved to the disused ...

festival in Kinross

Kinross (, gd, Ceann Rois) is a burgh in Perth and Kinross, Scotland, around south of Perth and around northwest of Edinburgh. It is the traditional county town of the historic county of Kinross-shire.

History

Kinross's origins are connect ...

.

In the media

In June 2019, an anti-Scottish poem titled "Friendly Fire" was recirculated on the internet, leading to criticism ofBoris Johnson

Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson (; born 19 June 1964) is a British politician, writer and journalist who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2019 to 2022. He previously served as F ...

. The poem was written by James Michie

James Michie (24 June 1927 – 30 October 2007) was an English poet, translator and editor.

Michie was born in Weybridge, Surrey, the son of a banker and the younger brother of Donald Michie, a researcher in artificial intelligence.

The texts ...

and published in The Spectator

''The Spectator'' is a weekly British magazine on politics, culture, and current affairs. It was first published in July 1828, making it the oldest surviving weekly magazine in the world.

It is owned by Frederick Barclay, who also owns ''The ...

magazine in 2004 by Johnson, who was editor of the magazine at the time. The poem reads:''The Scotch – what a verminous race!'' ''Canny, pushy, chippy, they're all over the place,'' ''Battening off us with false bonhomie,'' ''Polluting our stock, undermining our economy.'' ''Down with sandy hair and knobbly knees!'' ''Suppress the tartan dwarves and the Wee Frees!'' ''Ban the kilt, the skean-dhu and the sporran'' ''As provocatively, offensively foreign!'' ''It's time Hadrian’s Wall was refortified'' ''To pen them in a ghetto on the other side.'' ''I would go further. The nation'' ''Deserves not merely isolation'' ''But comprehensive extermination.'' ''We must not flinch from a solution.'' ''(I await legal prosecution.)''In a 2007 obituary title

James Michie, gentle genius

Boris Johnson dubbed Michie "one of the most distinguished poets and translators of the 20th century" and referred to "Friendly Fire" as an example of how he wrote "whimsically, sometimes with bite." The term

Scottish mafia

The Scottish mafia, Scottish Labour mafia, tartan mafia, Scottish Raj, or Caledonian mafia was a term used in the politics of England from the mid 1960s, until the collapse in the number of Scottish Labour MPs at the 2015 United Kingdom general ...

is a pejorative term used to refer to a group of Scottish Labour Party politicians and broadcasters who are believed to have had undue influence over the governance of England

There has not been a government of England since 1707 when the Kingdom of England ceased to exist as a sovereign state, as it merged with the Kingdom of Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.constitutional arrangement allowing Scottish MPs to vote on English matters, but not the other way around. The termed had found usage in the UK press and in parliamentary debates. Members of this group include

Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He previously served as Leader of th ...

, Gordon Brown

James Gordon Brown (born 20 February 1951) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 2007 to 2010. He previously served as Chance ...

, Alistair Darling

Alistair Maclean Darling, Baron Darling of Roulanish, (born 28 November 1953) is a British politician who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer under Prime Minister Gordon Brown from 2007 to 2010. A member of the Labour Party, he was a Member ...

, Charles Falconer, Derry Irvine, Michael Martin and John Reid.

An edition of the BBC satirical show '' Have I Got News for You'' aired on 26 April 2013 prompted over 100 complaints to the BBC and Ofcom

The Office of Communications, commonly known as Ofcom, is the government-approved regulatory and competition authority for the broadcasting, telecommunications and postal industries of the United Kingdom.

Ofcom has wide-ranging powers acros ...

for its perceived anti-Scottish stance during a section discussing Scottish independence

Scottish independence ( gd, Neo-eisimeileachd na h-Alba; sco, Scots unthirldom) is the idea of Scotland as a sovereign state, independent from the United Kingdom, and refers to the political movement that is campaigning to bring it about.

S ...

. Panelist Paul Merton

Paul James Martin (born 9 July 1957), known under the stage name Paul Merton, is an English writer, actor, comedian and radio and television presenter.

Known for his improvisation skill, Merton's humour is rooted in deadpan, surreal and someti ...

had suggested Mars bar

Mars, commonly known as Mars bar, is the name of two varieties of chocolate bar produced by Mars, Incorporated. It was first manufactured in 1932 in Slough, England by Forrest Mars, Sr. The bar consists of caramel and nougat coated with mi ...

s would become the currency of a post-independence Scotland, while guest host Ray Winstone

Raymond Andrew Winstone (; born 19 February 1957) is an English television, stage and film actor with a career spanning five decades. Having worked with many prominent directors, including Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg, Winstone is perha ...

added, "To be fair the Scottish economy has its strengths – its chief exports being oil, whisky, tartan and tramps."

In July 2006, former editor of '' The Sun'' Kelvin MacKenzie

Kelvin Calder MacKenzie (born 22 October 1946) is an English media executive and a former newspaper editor. He became editor of '' The Sun'' in 1981, by which time the publication was established as Britain's largest circulation newspaper. Aft ...

,who is of Scottish descent himself; his grandfather hailed from Stirling

Stirling (; sco, Stirlin; gd, Sruighlea ) is a city in central Scotland, northeast of Glasgow and north-west of Edinburgh. The market town, surrounded by rich farmland, grew up connecting the royal citadel, the medieval old town with its me ...

,) wrote a column referring to Scots as 'Tartan

Tartan ( gd, breacan ) is a patterned cloth consisting of criss-crossed, horizontal and vertical bands in multiple colours. Tartans originated in woven wool, but now they are made in other materials. Tartan is particularly associated with Sc ...

Tosspots' and mocking the fact that Scotland has a lower life expectancy than the rest of the U.K. MacKenzie's column provoked a storm of Scottish protest and was heavily condemned by numerous commentators including Scottish MPs and MSPs. In October 2007, MacKenzie appeared on the BBC's ''Question Time

A question time in a parliament occurs when members of the parliament ask questions of government ministers (including the prime minister), which they are obliged to answer. It usually occurs daily while parliament is sitting, though it can be ca ...

'' TV programme and launched another attack on Scotland, claiming that:

Quotations

* "The noblest prospect which a Scotchman ever sees, is the high road that leads to England." –Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

See also

*Scottish cringe

The Scottish cringe is a cultural cringe relating to Scotland, and claimed to exist by politicians and commentators.

These cultural commentators claim that a sense of Inferiority complex, cultural inferiority is felt by many Scots, particularly i ...

* Scottish national identity

Scottish national identity is a term referring to the sense of national identity, as embodied in the shared and characteristic culture, languages and traditions, of the Scottish people.

Although the various dialects of Gaelic, the Scots lan ...

References

Sources

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Anti-Scottish Sentiment Anti-British sentiment Scottish Scottish society