Anatoly Vasilyevich Lunacharsky on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anatoly Vasilyevich Lunacharsky (russian: Анато́лий Васи́льевич Лунача́рский) (born Anatoly Aleksandrovich Antonov, – 26 December 1933) was a Russian

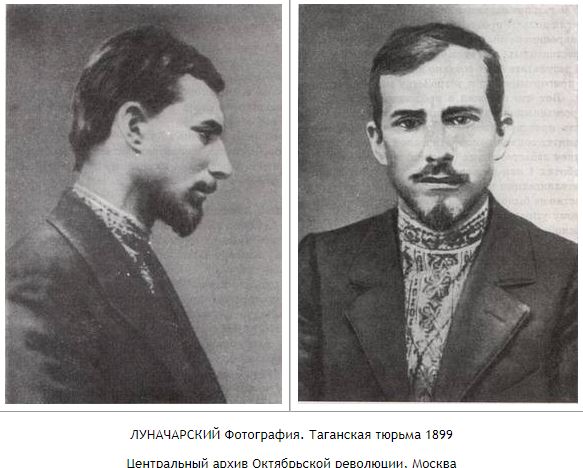

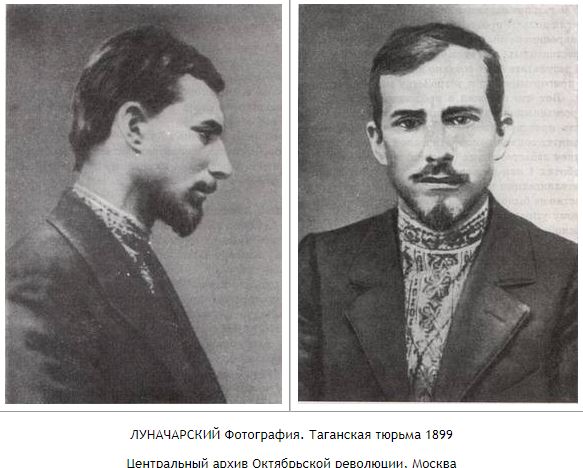

In 1899, Lunacharsky returned to Russia, where he and Vladimir Lenin's sister revived the Moscow Committee of the

In 1899, Lunacharsky returned to Russia, where he and Vladimir Lenin's sister revived the Moscow Committee of the

A week before the October Revolution, Lunacharsky convened and presided over a conference of proletarian cultural and educational organisations, at which the independent art movement Proletkult was launched, with Lunacharsky's former colleague, Bogdanov, as its leading figure. In October 1920, he clashed with Lenin, who insisted on bringing Proletkult under state control. But though he believed in encouraging factories to create literature or art, he did not share the hostility to "bourgeois" art forms exhibited by RAPP and other exponents of proletarian art.

In the week after the revolution, he invited everyone in Petrograd involved in cultural or artistic work to a meeting at Communist Party headquarters. Although the meeting was widely advertised, no more than seven people turned up, though they included Alexander Blok, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Vsevolod Meyerhold and Larissa Reissner.

A week before the October Revolution, Lunacharsky convened and presided over a conference of proletarian cultural and educational organisations, at which the independent art movement Proletkult was launched, with Lunacharsky's former colleague, Bogdanov, as its leading figure. In October 1920, he clashed with Lenin, who insisted on bringing Proletkult under state control. But though he believed in encouraging factories to create literature or art, he did not share the hostility to "bourgeois" art forms exhibited by RAPP and other exponents of proletarian art.

In the week after the revolution, he invited everyone in Petrograd involved in cultural or artistic work to a meeting at Communist Party headquarters. Although the meeting was widely advertised, no more than seven people turned up, though they included Alexander Blok, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Vsevolod Meyerhold and Larissa Reissner.

Lunacharsky's remains were returned to Moscow, where his urn was buried in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis, a rare privilege during the Soviet era. During the Great Purge of 1936–1938, Lunacharsky's name was erased from the Communist Party's history and his memoirs were banned. A revival came in the late 1950s and 1960s, with a surge of memoirs about Lunacharsky and many streets and organizations named or renamed in his honor. During that era, Lunacharsky was viewed by the Soviet

Lunacharsky's remains were returned to Moscow, where his urn was buried in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis, a rare privilege during the Soviet era. During the Great Purge of 1936–1938, Lunacharsky's name was erased from the Communist Party's history and his memoirs were banned. A revival came in the late 1950s and 1960s, with a surge of memoirs about Lunacharsky and many streets and organizations named or renamed in his honor. During that era, Lunacharsky was viewed by the Soviet  In the 1960s, his daughter Irina Lunacharsky helped revive his popularity. Several streets and institutions were named in his honor.

In 1971, Asteroid 2446 was named after Lunacharsky.

Some Soviet-built orchestral

In the 1960s, his daughter Irina Lunacharsky helped revive his popularity. Several streets and institutions were named in his honor.

In 1971, Asteroid 2446 was named after Lunacharsky.

Some Soviet-built orchestral

Works by Lunacharsky at Marxist internet archive

* Robert C Williams, 'From Positivism to Collectivism: Lunarcharsky and Proletarian Culture', in Williams, ''Artists in Revolution'', Indiana University Press, 1977

''Vasilisa the Wise''

(A play by Lunacharsky, in English) *

Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

revolutionary and the first Bolshevik Soviet People's Commissar (Narkompros) responsible for Ministry of Education as well as an active playwright, critic, essayist and journalist throughout his career.

Background

Lunacharsky was born on 23 or 24 November 1875 inPoltava

Poltava (, ; uk, Полтава ) is a city located on the Vorskla River in central Ukraine. It is the capital city of the Poltava Oblast (province) and of the surrounding Poltava Raion (district) of the oblast. Poltava is administratively ...

, Ukraine (then part of the Russian Empire) as the illegitimate child of Alexander Antonov and Alexandra Lunacharskaya, née Rostovtseva. His mother was then married to statesman Vasily Lunacharsky, a nobleman of Polish origin, whence Anatoly's surname and patronym. She later divorced Vasily Lunacharsky and married Antonov, but Anatoly kept his former name.

In 1890, at the age of 15, Lunacharsky became a Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

. From 1894, he studied at the University of Zurich under Richard Avenarius for two years without taking a degree. In Zürich he met European socialists, including Rosa Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg (; ; pl, Róża Luksemburg or ; 5 March 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a Polish and naturalised-German revolutionary socialist, Marxist philosopher and anti-war activist. Successively, she was a member of the Proletariat party, ...

and Leo Jogiches, and joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP; in , ''Rossiyskaya sotsial-demokraticheskaya rabochaya partiya (RSDRP)''), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party or the Russian Social Democratic Party, was a socialist pol ...

. He also lived for a time in France.

Early career

In 1899, Lunacharsky returned to Russia, where he and Vladimir Lenin's sister revived the Moscow Committee of the

In 1899, Lunacharsky returned to Russia, where he and Vladimir Lenin's sister revived the Moscow Committee of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP; in , ''Rossiyskaya sotsial-demokraticheskaya rabochaya partiya (RSDRP)''), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party or the Russian Social Democratic Party, was a socialist pol ...

(RSDLP), until they were betrayed by an informant and arrested. He was allowed to settle in Kyiv, but was arrested again after resuming his political activities, and after ten months in prison he was sent to Kaluga

Kaluga ( rus, Калу́га, p=kɐˈɫuɡə), a city and the administrative center of Kaluga Oblast in Russia, stands on the Oka River southwest of Moscow. Population:

Kaluga's most famous resident, the space travel pioneer Konstantin Tsiol ...

, where he joined a Marxist circle that included Alexander Bogdanov

Alexander Aleksandrovich Bogdanov (russian: Алекса́ндр Алекса́ндрович Богда́нов; – 7 April 1928), born Alexander Malinovsky, was a Russian and later Soviet physician, philosopher, science fiction writer, and B ...

and Vladimir Bazarov.

In February 1902, he was exiled to Kushinov village in Vologda, where he again shared his exile with Bogdanov, whose sister he married, and with the Legal Marxist

Legal Marxism was a Russian Marxist movement based on a particular interpretation of Marxist theory whose proponents were active in socialist circles between 1894 and 1901. The movement's primary theoreticians were Pyotr Struve, Nikolai Berdyaev, S ...

Nikolai Berdyaev

Nikolai Alexandrovich Berdyaev (; russian: Никола́й Алекса́ндрович Бердя́ев; – 24 March 1948) was a Russian Empire, Russian philosopher, theologian, and Christian existentialism, Christian existentialist who e ...

and the Socialist Revolutionary terrorist Boris Savinkov

Boris Viktorovich Savinkov (Russian: Бори́с Ви́кторович Са́винков; 31 January 1879 – 7 May 1925) was a Russian writer and revolutionary. As one of the leaders of the Fighting Organisation, the paramilitary win ...

among others. After the first issue of Lenin's newspaper '' Iskra'' had reached Vologda, Bogdanov and Lunacharsky organised a Marxist circle that distributed illegal literature, while he also legally wrote theatre criticism for a local liberal newspaper. In March 1903, the governor of Vologda ordered Lunacharsky to be transferred further north, to Totma, where they were the only political exiles.

In 1903, the RSDLP split between the Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, and the Mensheviks. Lunacharsky, who by now had ended his period in exile and was back in Kyiv, originally believed that the split was unnecessary and joined the 'conciliators', who hoped to bring the two sides together, but he was converted to Bolshevism by Bogdanov. In 1904, he moved to Geneva and became one of Lenin's most active collaborators and an editor of the first exclusively Bolshevik newspaper, '' Vpered''. According to Nadezhda Krupskaya:

Lunacharsky returned to Russia after the outbreak of the 1905 Revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

. In Moscow he co-edited the journal ''Novaya zhizn'' and other Bolshevik publications, which could be published legally, and gave lectures on art and literature. Arrested during a workers' meeting, he spent a month in Kresty Prison.

Soon after his release, he faced "extremely serious" charges, and fled abroad, via Finland, in March 1906. In 1907, he attended the International Socialist Congress held in Stuttgart

Stuttgart (; Swabian: ; ) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Baden-Württemberg. It is located on the Neckar river in a fertile valley known as the ''Stuttgarter Kessel'' (Stuttgart Cauldron) and lies an hour from the ...

.

Vpered

In 1908, when the Bolsheviks split between Lenin's supporters and Alexander Bogdanov's followers, Lunacharsky supported his brother-in-law Bogdanov in setting up a new '' Vpered''. During this period, he wrote a two-volume work on the relationship between Marxism and religion, ''Religion and Socialism'' (1908, 1911), declaring that god should be interpreted as "humanity in the future". This earned him the description "god builder". Like many contemporary socialists (including Bogdanov), Lunacharsky was influenced by the empirio-criticism philosophy ofErnst Mach

Ernst Waldfried Josef Wenzel Mach ( , ; 18 February 1838 – 19 February 1916) was a Moravian-born Austrian physicist and philosopher, who contributed to the physics of shock waves. The ratio of one's speed to that of sound is named the Mach ...

and Avenarius. Lenin opposed Machism as a form of subjective idealism and strongly criticised its proponents in his book '' Materialism and Empirio-criticism'' (1908).

In 1909, Lunacharsky joined Bogdanov and Maxim Gorky at the latter's villa on the island of Capri

Capri ( , ; ; ) is an island located in the Tyrrhenian Sea off the Sorrento Peninsula, on the south side of the Gulf of Naples in the Campania region of Italy. The main town of Capri that is located on the island shares the name. It has been ...

, where they started a school for Russian socialist workers. In 1910, Bogdanov, Lunacharsky, Mikhail Pokrovsky

Mikhail Nikolayevich Pokrovsky (russian: Михаи́л Никола́евич Покро́вский; – April 10, 1932) was a Russian Marxist historian, Bolshevik revolutionary and a public and political figure. One of the earliest professio ...

and their supporters moved the school to Bologna, where they continued teaching classes through 1911. In 1911, Lunacharsky moved to Paris, where he started his own Circle of Proletarian Culture.

World War I

After the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Lunacharsky adopted an internationalist antiwar position, which put him on a course of convergence with Lenin and Leon Trotsky. In 1915, Lunacharsky and Pavel Lebedev-Poliansky restarted the social democratic newspaper ''Vpered'' with an emphasis on proletarian culture.Bernice Glatzer Rosenthal, ''New Myth, New World: From Nietzsche to Stalinism'', Pennsylvania State University, 2002, p.85 From 1915, he also worked for the daily newspaper '' Nashe Slovo'', sometimes acting as peacemaker between the two editors, Trotsky and the Menshevik internationalistJulius Martov

Julius Martov or L. Martov (Ма́ртов; born Yuliy Osipovich Tsederbaum; 24 November 1873 – 4 April 1923) was a politician and revolutionary who became the leader of the Mensheviks in early 20th-century Russia. He was arguably the closes ...

.

After the February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and somet ...

of 1917, Lunacharsky left his family in Switzerland and returned to Russia on a sealed train - though not the same train that Lenin had used earlier. Like other internationalist social democrats returning from abroad, he briefly joined the Mezhraiontsy before they merged with the Bolsheviks in July–August 1917. He was also cultural editor of ''Novaya Zhizn'', until forced against his will to sever this connection, because the paper took an anti-Bolshevik line.

Even before he formally joined the Bolsheviks, he proved to be one of their most popular and effective orators, often sharing a platform with Trotsky. He was arrested with Trotsky on 22 July 1917, on a charge of inciting the " July Days" riots, and was held in Kresty prison until September.

People's Commissariat for Education (Narkompros)

After the October Revolution of 1917, Lunacharsky was appointed head of the People's Commissariat for Education (Narkompros) in the first Soviet government. On 15 November, after eight days in this post, he resigned in protest over a rumour that the Bolsheviks had bombardedSt Basil's Cathedral

The Cathedral of Vasily the Blessed ( rus, Собо́р Васи́лия Блаже́нного, Sobór Vasíliya Blazhénnogo), commonly known as Saint Basil's Cathedral, is an Orthodox church in Red Square of Moscow, and is one of the most pop ...

on Red Square while they were storming the Kremlin

The Kremlin ( rus, Московский Кремль, r=Moskovskiy Kreml', p=ˈmɐˈskofskʲɪj krʲemlʲ, t=Moscow Kremlin) is a fortified complex in the center of Moscow founded by the Rurik dynasty, Rurik dynasty. It is the best known of th ...

, but after two days he withdrew his resignation. After the creation of the Soviet Union, he was People's Commissar for Enlightenment, which was a function devolved to the union republics, for the Russian Federation only.

Lunacharsky opposed the decision in 1918 to transfer Russia's capital to Moscow and stayed for a year in Petrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

(now Saint Petersburg) and left the running of his commissariat to his deputy, Mikhail Pokrovsky

Mikhail Nikolayevich Pokrovsky (russian: Михаи́л Никола́евич Покро́вский; – April 10, 1932) was a Russian Marxist historian, Bolshevik revolutionary and a public and political figure. One of the earliest professio ...

.

Education

On 10 November 1917, Lunacharsky signed a decree making school education a state monopoly at local government level and said that his department would not claim central power over schools. In December, he ordered church schools to be brought under the jurisdiction of local soviets. He faced determined opposition from the teachers' union. In February 1918, the fourth month of a teachers' strike, he ordered all teachers to report to their local soviets and to stand for re-election to their jobs. In March, he reluctantly disbanded the union and sequestered its funds. Largely because of the opposition from teachers, he had to abandon his scheme for local autonomy. He also believed in polytechnic schools, in which children could learn a range of basic skills, including manual skills, with specialist training beginning in late adolescence. All children were to have the same education and would automatically qualify for higher education, but opposition from Trotsky and others later compelled him to agree that specialist education would begin in secondary schools. In July 1918, he proposed that all university lecturers should be elected for seven-year terms, irrespective of their academic qualifications, that all courses would be free, and that institutions would be run by elected councils made of staff and students. His ideas were vigorously opposed by academics. In June 1919, ''The New York Times'' decried Lunacharsky's efforts in education in an article entitled "Reds Are Ruining Children of Russia". It claimed that he was instilling a "system of calculated moral depravity ..in one of the most diabolical of all measures conceived by the Bolshevik rulers of Russia".Culture

A week before the October Revolution, Lunacharsky convened and presided over a conference of proletarian cultural and educational organisations, at which the independent art movement Proletkult was launched, with Lunacharsky's former colleague, Bogdanov, as its leading figure. In October 1920, he clashed with Lenin, who insisted on bringing Proletkult under state control. But though he believed in encouraging factories to create literature or art, he did not share the hostility to "bourgeois" art forms exhibited by RAPP and other exponents of proletarian art.

In the week after the revolution, he invited everyone in Petrograd involved in cultural or artistic work to a meeting at Communist Party headquarters. Although the meeting was widely advertised, no more than seven people turned up, though they included Alexander Blok, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Vsevolod Meyerhold and Larissa Reissner.

A week before the October Revolution, Lunacharsky convened and presided over a conference of proletarian cultural and educational organisations, at which the independent art movement Proletkult was launched, with Lunacharsky's former colleague, Bogdanov, as its leading figure. In October 1920, he clashed with Lenin, who insisted on bringing Proletkult under state control. But though he believed in encouraging factories to create literature or art, he did not share the hostility to "bourgeois" art forms exhibited by RAPP and other exponents of proletarian art.

In the week after the revolution, he invited everyone in Petrograd involved in cultural or artistic work to a meeting at Communist Party headquarters. Although the meeting was widely advertised, no more than seven people turned up, though they included Alexander Blok, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Vsevolod Meyerhold and Larissa Reissner.

Art

Lunacharsky directed some of the great experiments in public arts after the Revolution, such as the agit-trains and agit-boats that circulated over all Russia spreading Revolution and revolutionary arts. He also gave support to constructivism's experiments and the initiatives such as theROSTA Windows

ROSTA Posters (also known as ROSTA Windows, russian: Окна РОСТА, ROSTA being an acronym for the Russian Telegraph Agency, the state news agency from 1918 to 1935) were a propagandistic medium of communication used in the Soviet Union to ...

, revolutionary posters designed and written by Mayakovsky, Rodchenko and others. With his encouragement, 36 new art galleries were opened in 1918-21.

Cinema

Mayakovsky stimulated his interest in cinema, then a new art form. Lunacharsky wrote an "agit-comedy", which was filmed in the streets of Petrograd for the first anniversary of the Bolshevik revolution. Soon afterwards, he nationalised the film industry and founded the State Film School. In 1920, he told George Lansbury: "So far, cinemas are not much use owing to shortage of materials. ... When these difficulties are removed ... the story of humanity will be told in pictures".Theatre

In the early 1920s, theatre appears to have been the art form to which Lunacharsky attached the greatest importance. In 1918, when most Bolsheviks despised experimental art, Lunacharsky praised Mayakovsky's play Mystery-Bouffe, directed by Meyerhold, which he described as "original, powerful and beautiful". But his main interest was not experimental theatre. During the civil war, he wrote two symbolic dramas, ''The Magi'' and ''Ivan Goes to Heaven'', and a historical drama ''Oliver Cromwell.'' In July 1919, he took personal charge of the theatre administration from Olga Kameneva, with the intention of reviving realism on stage. Lunacharsky was associated with the establishment of theBolshoi Drama Theater

Tovstonogov Bolshoi Drama Theater (russian: Большой драматический театр имени Г. А. Товстоногова; literally ''Tovstonogov Great Drama Theater''), formerly known as Gorky Bolshoi Drama Theater (russian: ...

in 1919, working with Maxim Gorky, Alexander Blok and Maria Andreyeva. He also played a part in persuading the Moscow Art Theatre

The Moscow Art Theatre (or MAT; russian: Московский Художественный академический театр (МХАТ), ''Moskovskiy Hudojestvenny Akademicheskiy Teatr'' (МHАТ)) was a theatre company in Moscow. It was f ...

(MAT) and its renowned directors Konstantin Stanislavski

Konstantin Sergeyevich Stanislavski ( Alekseyev; russian: Константин Сергеевич Станиславский, p=kənstɐnʲˈtʲin sʲɪrˈgʲejɪvʲɪtɕ stənʲɪˈslafskʲɪj; 7 August 1938) was a seminal Russian Soviet Fe ...

and Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko to end their opposition to the regime and resume productions. In January 1922 he protested vigorously after Lenin had ordered that the Bolshoi Ballet

The Bolshoi Ballet is an internationally renowned classical ballet company based at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow, Russia. Founded in 1776, the Bolshoi is among the world's oldest ballet companies. In the early 20th century, it came to internatio ...

was to be closed, and succeeded in keeping it open.

In 1923 he launched a ''Back to Ostrovsky'' movement to mark the centenary of Russia's first great playwright. He was also personally involved in the decision to allow the MAT to stage Mikhail Bulgakov

Mikhail Afanasyevich Bulgakov ( rus, links=no, Михаил Афанасьевич Булгаков, p=mʲɪxɐˈil ɐfɐˈnasʲjɪvʲɪtɕ bʊlˈɡakəf; – 10 March 1940) was a Soviet writer, medical doctor, and playwright active in the fir ...

's first play, ''The Days of the Turbins

''The Days of the Turbins'' (russian: Дни Турбиных, translit=Dni Turbinykh) is a four-act play by Mikhail Bulgakov based upon his novel ''The White Guard''.

It was written in 1925 and premiered on 5 October 1926 in Moscow Art Theatr ...

'' (usually known by its original title, '' The White Guard'')

Literature

Despite his belief in 'proletarian' literature, Lunacharsky also defended writers who were not experimental, nor even sympathetic to the Bolsheviks. He also helpedBoris Pasternak

Boris Leonidovich Pasternak (; rus, Бори́с Леони́дович Пастерна́к, p=bɐˈrʲis lʲɪɐˈnʲidəvʲɪtɕ pəstɛrˈnak; 30 May 1960) was a Russian poet, novelist, composer and literary translator. Composed in 1917, Pa ...

. In 1924, Pasternak's wife wrote to his cousin saying "so far, Lunacharsky has never refused to see Borya".

Music

Lunacharsky was the first Bolshevik to recognise the value of the composer Sergei Prokofiev, whom he met in April 1918, after the premiere of his '' Classical Symphony''. In 1926, he wrote "the freshness and rich imagination characteristic of Prokofiev attest to his exceptional talent". He arranged a passport that allowed Prokofiev to leave Russia, then in July 1925 he persuaded theCentral Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, – TsK KPSS was the executive leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, acting between sessions of Congress. According to party statutes, the committee direct ...

to invite Prokofiev, Igor Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor, later of French (from 1934) and American (from 1945) citizenship. He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the ...

, and the pianist Alexander Borovsky

Alexander Borovsky (Borowsky) (1889-1968), a Russian-American pianist, was born in Mitau, Russia. His first piano teacher was his mother, a pupil of Vasily Safonov. He completed his studies at the St. Petersburg Conservatory in 1912 with a gold med ...

to return to Russia. Stravinsky and Borovsky rejected the offer, but Prokofiev was given permission to come and go freely while Lunacharsky was in office. In February 1927, he sat with Prokofiev during the first Russian performance of The Love for Three Oranges, which he compared to "a glass of champagne, all sparkling and frothy".

In 1929, Lunacharsky supported a change in the Russian alphabet

The Russian alphabet (russian: ру́сский алфави́т, russkiy alfavit, , label=none, or russian: ру́сская а́збука, russkaya azbuka, label=none, more traditionally) is the script used to write the Russian language. I ...

from Cyrillic to Latin.

Personality

Though he was influential in setting Soviet policy on culture and education, particularly in the early years while Lenin was alive, Lunacharsky was not a powerful figure. Trotsky described him as "a man always easily infected by the moods of those around him, imposing in appearance and voice, eloquent in a declamatory way, none too reliable, but often irreplaceable." But Ilya Ehrenburg wrote: "I was struck by something different: he was not a poet, he was engrossed in political activity, but an extraordinary love of art burned in him", and Nikolai Sukhanov, who knew him well, wrote thatLater career

Lunacharsky avoided taking sides when the Communist Party split after Lenin's death, but he almost became embroiled in the split by accident by publishing his selection of ''Revolutionary Silhouettes'' in 1923, which included portraits of Trotsky,Grigory Zinoviev

Grigory Yevseyevich Zinoviev, . Transliterated ''Grigorii Evseevich Zinov'ev'' according to the Library of Congress system. (born Hirsch Apfelbaum, – 25 August 1936), known also under the name Ovsei-Gershon Aronovich Radomyslsky (russian: Ов ...

, and Martov

Julius Martov or L. Martov (Ма́ртов; born Yuliy Osipovich Tsederbaum; 24 November 1873 – 4 April 1923) was a politician and revolutionary who became the leader of the Mensheviks in early 20th-century Russia. He was arguably the closes ...

, but failed to mention Stalin. Later, he offended Trotsky by saying at an event in the Bolshoi Theatre to commemorate the second anniversary of Lenin's death, that "they" (he did not say who) were willing to offer Trotsky "a crown on a velvet cushion" and "hail him as Lev I".

After about 1927, he was losing control over cultural policy to Stalinists like Leopold Averbakh

Leopold Leonidovich Averbakh (Russian: Леопо́льд Леони́дович Аверба́х; 8 March, 1903 Saratov – 14 August, 1937, Moscow) was a Soviet literary critic, who was the head of the Russian Association of Proletarian Writers ...

. After he was removed from office, in 1929, Lunacharsky was appointed to the Learned Council of the Soviet Union Central Executive Committee. He also became an editor for the Literature Encyclopedia (published 1929–1939).

Lunacharsky represented the Soviet Union at the League of Nations from 1930 through 1932.

In 1933, he was appointed ambassador

An ambassador is an official envoy, especially a high-ranking diplomat who represents a state and is usually accredited to another sovereign state or to an international organization as the resident representative of their own government or sov ...

to Spain, a post he never assumed, as he died ''en route''.

Death

Lunacharsky died at 58 on 26 December 1933 in Menton, France, while traveling to Spain to take up the post of Soviet ambassador there, as the conflict that became the Spanish Civil War appeared increasingly inevitable.

Personal life

In 1902, he married Anna Alexandrovna Malinovskaya,Alexander Bogdanov

Alexander Aleksandrovich Bogdanov (russian: Алекса́ндр Алекса́ндрович Богда́нов; – 7 April 1928), born Alexander Malinovsky, was a Russian and later Soviet physician, philosopher, science fiction writer, and B ...

's sister. They had one child, a daughter named Irina Lunacharsky. In 1922, he met Natalya Rozenel Natalya (russian: Наталья) is the Russian form of the female given name Natalia.

The name Natasha (russian: link=no, Наташа), being originally a diminutive form of Natalya, became an independent name outside the Russian-speaking state ...

, an actress at the Maly Theatre The Maly Theatre, or Mali Theatre, may refer to one of several different theatres:

* The Maly Theatre (Moscow), also known as The State Academic Maly Theatre of Russia, in Moscow (founded in 1756 and given its own building in 1824)

* The Maly Theat ...

. He left his family and married her. Sergei Prokofiev, who met her in 1927, described her as "one of his most recent wives", and as "a beautiful woman from the front, much less beautiful if you looked at her predatory profile". He claimed that Lunacharsky had previously been the lover of the ballerina Inna Chernetskaya

Elena Alexandra Apostoleanu (born 16 October 1986), known professionally as Inna (stylized in all caps), is a Romanian singer. Born in Mangalia and raised in Neptun, Romania, Neptun, she studied political science at Ovidius University before ...

.

Lunacharsky was known as an art connoisseur and a critic. Besides Marxist dialectics, he had been interested in philosophy since he was a student. For instance, he was fond of the ideas of Johann Gottlieb Fichte

Johann Gottlieb Fichte (; ; 19 May 1762 – 29 January 1814) was a German philosopher who became a founding figure of the philosophical movement known as German idealism, which developed from the theoretical and ethical writings of Immanuel Kan ...

, Frederich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his care ...

and Richard Avenarius. He could read six modern languages and two dead ones. Lunacharsky corresponded with H. G. Wells, Bernard Shaw and Romain Rolland. He met numerous other famous cultural figures such as Rabindranath Tagore and Nicholas Roerich.

Lunacharsky once described Nadezhda Krupskaya

Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya ( rus, links=no, Надежда Константиновна Крупская, p=nɐˈdʲeʐdə kənstɐnˈtʲinəvnə ˈkrupskəjə; 27 February 1939) was a Russian revolutionary and the wife of Vladimir Lenin ...

as the "soul of Narkompros".

Friends included Igor Moiseyev.

Legacy

Lunacharsky's remains were returned to Moscow, where his urn was buried in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis, a rare privilege during the Soviet era. During the Great Purge of 1936–1938, Lunacharsky's name was erased from the Communist Party's history and his memoirs were banned. A revival came in the late 1950s and 1960s, with a surge of memoirs about Lunacharsky and many streets and organizations named or renamed in his honor. During that era, Lunacharsky was viewed by the Soviet

Lunacharsky's remains were returned to Moscow, where his urn was buried in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis, a rare privilege during the Soviet era. During the Great Purge of 1936–1938, Lunacharsky's name was erased from the Communist Party's history and his memoirs were banned. A revival came in the late 1950s and 1960s, with a surge of memoirs about Lunacharsky and many streets and organizations named or renamed in his honor. During that era, Lunacharsky was viewed by the Soviet intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the in ...

as an educated, refined and tolerant Soviet politician.

In the 1960s, his daughter Irina Lunacharsky helped revive his popularity. Several streets and institutions were named in his honor.

In 1971, Asteroid 2446 was named after Lunacharsky.

Some Soviet-built orchestral

In the 1960s, his daughter Irina Lunacharsky helped revive his popularity. Several streets and institutions were named in his honor.

In 1971, Asteroid 2446 was named after Lunacharsky.

Some Soviet-built orchestral harp

The harp is a stringed musical instrument that has a number of individual strings running at an angle to its soundboard; the strings are plucked with the fingers. Harps can be made and played in various ways, standing or sitting, and in orche ...

s also bear the name of Lunacharsky, presumably in his honor. These concert pedal harps were produced in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg, Russia).

''The New York Times'' dubbed Nikolai Gubenko, last culture commissar of the Soviet Union, "the first arts professional since Anatoly V. Lunacharsky" because he seemed to "identify" with Lunacharsky.

Works

Lunacharsky was also a prolific writer. He wrote literary essays on the works of several writers, including Alexander Pushkin, George Bernard Shaw andMarcel Proust

Valentin Louis Georges Eugène Marcel Proust (; ; 10 July 1871 – 18 November 1922) was a French novelist, critic, and essayist who wrote the monumental novel ''In Search of Lost Time'' (''À la recherche du temps perdu''; with the previous Eng ...

. However, his most notable work is his memoirs, ''Revolutionary Silhouettes'', which describe anecdotes and Lunacharsky's general impressions of Lenin, Leon Trotsky and eight other revolutionaries. Trotsky reacted to some of Lunacharsky's opinions in his own autobiography, ''My Life My Life may refer to:

Autobiographies

* ''Mein Leben'' (Wagner) (''My Life''), by Richard Wagner, 1870

* ''My Life'' (Clinton autobiography), by Bill Clinton, 2004

* ''My Life'' (Meir autobiography), by Golda Meir, 1973

* ''My Life'' (Mosley a ...

''.

In the 1920s, Lunacharsky produced Lyubov Popova's ''The Locksmith and the Chancellor'' at the Comedy Theater.

Some of his works include:

* ''Outlines of a Collective Philosophy'' (1909)

* ''Self-Education of the Workers: The Cultural Task of the Struggling Proletariat'' (1918)

* ''Three Plays'' (1923)

* ''Revolutionary Silhouettes'' (1923)

* ''Theses on the Problems of Marxist Criticism'' (1928)

* ''Vladimir Mayakovsky, Innovator'' (1931)

* ''George Bernard Shaw'' (1931)

* ''Maxim Gorky'' (1932)

* ''On Literature and Art'' (1965)

See also

*God-Building

God-Building is an idea proposed by some prominent early Marxists in the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. Inspired by Auguste Comte's Religion of Humanity, the concept had some precedent in the French Revolutio ...

* New Soviet man

* Working-class culture

* Proletkult

* Proletarian literature

* Proletarian novel

References

Further reading

Works by Lunacharsky at Marxist internet archive

* Robert C Williams, 'From Positivism to Collectivism: Lunarcharsky and Proletarian Culture', in Williams, ''Artists in Revolution'', Indiana University Press, 1977

''Vasilisa the Wise''

(A play by Lunacharsky, in English) *

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Lunacharsky, Anatoli Vasilevich 1875 births 1933 deaths Politicians from Poltava People from Poltavsky Uyezd Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members Old Bolsheviks Mezhraiontsy Russian Constituent Assembly members People's commissars and ministers of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic Ambassadors of the Soviet Union to Spain Full Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences Soviet art critics Soviet literary critics Russian art critics Russian journalists Russian communists Russian atheists Russian memoirists Cervantists Russian revolutionaries Russian Marxist writers Burials at the Kremlin Wall Necropolis