American culture on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The culture of the United States of America is primarily of Western, and European origin, yet its influences includes the cultures of

The European roots of the United States originate with the

The European roots of the United States originate with the

Lee Alan Dugatkin. University of Chicago Press, 2009. , . University of Chicago Press, 2009. Chapter x. Thomas Jefferson's '' Major cultural influences have been brought by historical immigration, especially from

Major cultural influences have been brought by historical immigration, especially from  American culture includes both conservative and liberal elements, scientific and religious competitiveness, political structures, risk taking and free expression, materialist and moral elements. Despite certain consistent ideological principles (e.g.

American culture includes both conservative and liberal elements, scientific and religious competitiveness, political structures, risk taking and free expression, materialist and moral elements. Despite certain consistent ideological principles (e.g.

Semi-distinct cultural

Semi-distinct cultural

Although the United States has no

Although the United States has no

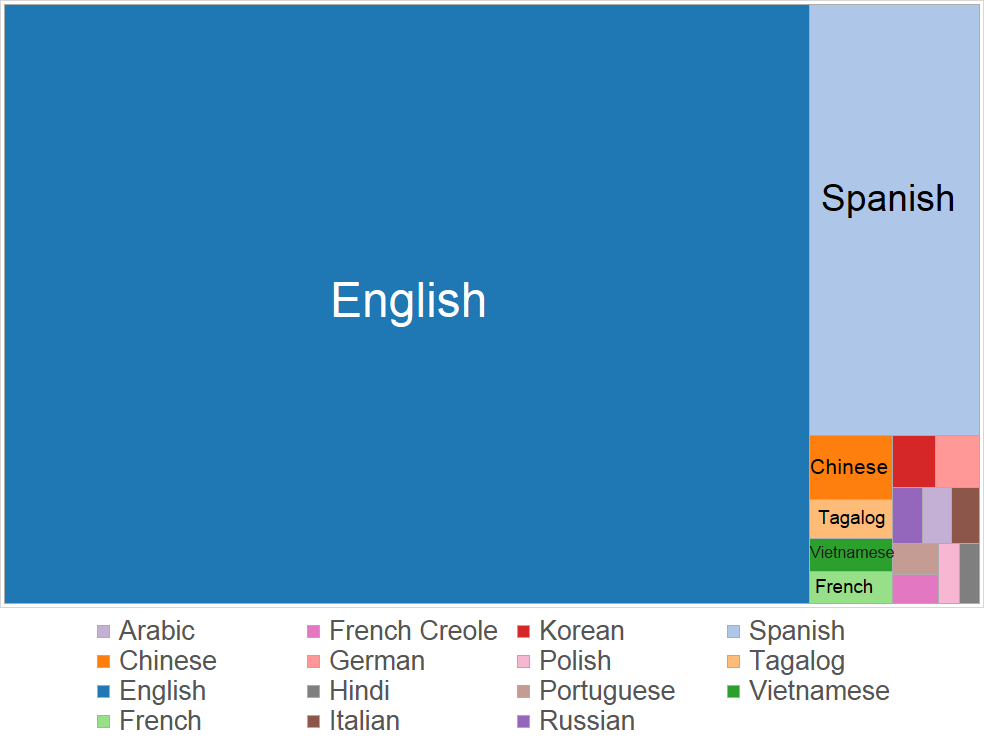

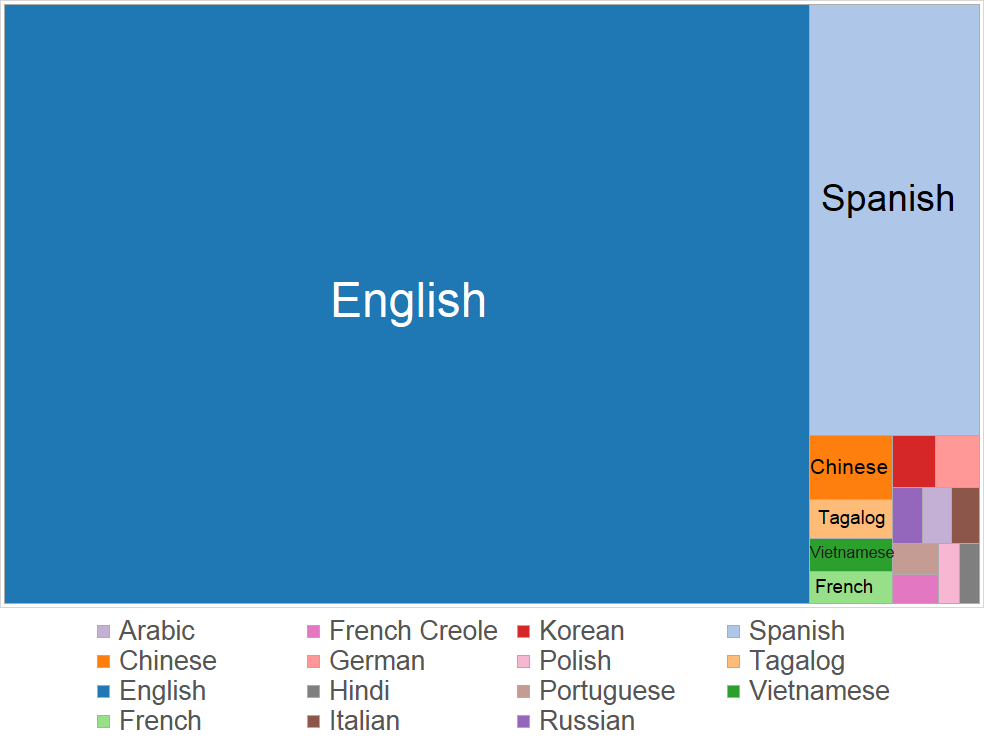

English-Speaking Ability of the Foreign-Born Population in the United States: 2012

" (revised). U.S. Census Bureau. This not only includes immigrants from countries such as

In the late-18th and early-19th centuries, American artists primarily painted landscapes and

In the late-18th and early-19th centuries, American artists primarily painted landscapes and

Architecture in the United States is regionally diverse and has been shaped by many external forces. U.S. architecture can therefore be said to be eclectic. Traditionally American architecture has influences from English architecture to Greco Roman architecture. The overriding theme of city American Architecture is modernity, as manifest in the skyscrapers of the 20th century, with domestic and residential architecture greatly varying according to local tastes and climate, rural American and

Architecture in the United States is regionally diverse and has been shaped by many external forces. U.S. architecture can therefore be said to be eclectic. Traditionally American architecture has influences from English architecture to Greco Roman architecture. The overriding theme of city American Architecture is modernity, as manifest in the skyscrapers of the 20th century, with domestic and residential architecture greatly varying according to local tastes and climate, rural American and

Theater of the United States is based in the Western tradition. The United States originated

Theater of the United States is based in the Western tradition. The United States originated

The cinema of the United States, also known as

The cinema of the United States, also known as

There is a regard for scientific advancement and technological innovation in American culture, resulting in the creation of many modern innovations. The great American inventors include

There is a regard for scientific advancement and technological innovation in American culture, resulting in the creation of many modern innovations. The great American inventors include  This propensity for application of scientific ideas continued throughout the 20th century with innovations that held strong international benefits. The twentieth century saw the arrival of the

This propensity for application of scientific ideas continued throughout the 20th century with innovations that held strong international benefits. The twentieth century saw the arrival of the  Throughout its history, American culture has made significant gains through the open immigration of accomplished scientists. Accomplished scientists include Scottish-American scientist

Throughout its history, American culture has made significant gains through the open immigration of accomplished scientists. Accomplished scientists include Scottish-American scientist

Education in the United States is and has historically been provided mainly by the government. Control and funding come from three levels: federal,

Education in the United States is and has historically been provided mainly by the government. Control and funding come from three levels: federal,

Among

Among  Most of the

Most of the

Mary Dyer of Rhode Island: The Quaker Martyr That Was Hanged on Boston

'' pp. 1–2. BiblioBazaar, LLC

Symbol of Enduring Freedom

, p. 19, Columbia Magazine, March 2010. Fifteen years later (1649), the

The United States observes holidays derived from events in

The United States observes holidays derived from events in

Fashion in the United States is eclectic and predominantly informal. While the diverse cultural roots of Americans are reflected in their clothing, particularly those of recent immigrants, cowboy hats and cowboy boot, boots, and leather motorcycle jackets are emblematic of specifically-American styles.

Jeans, Blue jeans were popularized as work clothes in the 1850s by merchant Levi Strauss, a German-Jewish immigrant in San Francisco, and adopted by many American teenagers a century later. They are worn in every state by people of all ages and social classes. Along with mass-marketed informal wear in general, blue jeans are arguably one of US culture's primary contributions to global fashion.

Though the informal dress is more common, certain professionals, such as bankers and lawyers, traditionally dress formally for work, and some occasions, such as weddings, funerals, dances, and some parties, typically call for formal wear.

Some cities and regions have specialties in certain areas. For example, Miami for swimwear, Boston and the general

Fashion in the United States is eclectic and predominantly informal. While the diverse cultural roots of Americans are reflected in their clothing, particularly those of recent immigrants, cowboy hats and cowboy boot, boots, and leather motorcycle jackets are emblematic of specifically-American styles.

Jeans, Blue jeans were popularized as work clothes in the 1850s by merchant Levi Strauss, a German-Jewish immigrant in San Francisco, and adopted by many American teenagers a century later. They are worn in every state by people of all ages and social classes. Along with mass-marketed informal wear in general, blue jeans are arguably one of US culture's primary contributions to global fashion.

Though the informal dress is more common, certain professionals, such as bankers and lawyers, traditionally dress formally for work, and some occasions, such as weddings, funerals, dances, and some parties, typically call for formal wear.

Some cities and regions have specialties in certain areas. For example, Miami for swimwear, Boston and the general

In the 1800s, colleges were encouraged to focus on intramural sports, particularly track and field, track, field, and, in the late 1800s, American football. Physical education was incorporated into primary school curriculums in the 20th century.

In the 1800s, colleges were encouraged to focus on intramural sports, particularly track and field, track, field, and, in the late 1800s, American football. Physical education was incorporated into primary school curriculums in the 20th century.

Baseball is the oldest of the major American team sports. Professional baseball dates from 1869 and had no close rivals in popularity until the 1960s. Though baseball is no longer the most popular sport, it is still referred to as "the national pastime." Also unlike the professional levels of the other popular spectator sports in the U.S., Major League Baseball teams play almost every day. The Major League Baseball Season (sports), regular season consists of each of the 30 teams playing 162 games from April to September. The season ends with the Major League Baseball postseason, postseason and World Series in October. Unlike most other major sports in the country, professional baseball draws most of its players from a Minor league baseball, "minor league" system, rather than from College sports in the United States, university athletics.

Baseball is the oldest of the major American team sports. Professional baseball dates from 1869 and had no close rivals in popularity until the 1960s. Though baseball is no longer the most popular sport, it is still referred to as "the national pastime." Also unlike the professional levels of the other popular spectator sports in the U.S., Major League Baseball teams play almost every day. The Major League Baseball Season (sports), regular season consists of each of the 30 teams playing 162 games from April to September. The season ends with the Major League Baseball postseason, postseason and World Series in October. Unlike most other major sports in the country, professional baseball draws most of its players from a Minor league baseball, "minor league" system, rather than from College sports in the United States, university athletics.

American football, known in the United States as simply "football," now attracts more television viewers than any other sport and is considered to be the most popular sport in the United States. The 32-team National Football League (NFL) is the most popular professional American football league.

The National Football League differs from the other three Major professional sports leagues in the United States and Canada, major pro sports leagues in that each of its 32 teams plays one game a week over 18 weeks, for a total of 17 games with one Bye (sports), bye week for each team. The National Football League regular season, NFL season lasts from September to December, ending with the National Football League playoffs, playoffs and Super Bowl in January and February.

Its championship game, the Super Bowl, has often been the highest rated television show, and it has an audience of over 100 million viewers annually.

College football also attracts audiences of millions. Some communities, particularly in rural areas, place great emphasis on their local high school football team. American football games usually include cheerleaders and marching bands, which aim to raise school spirit and entertain the crowd at halftime.

Basketball is another major sport, represented professionally by the National Basketball Association. It was invented in Springfield, Massachusetts in 1891, by Canadian-born physical education teacher James Naismith. College basketball is also popular, due in large part to the NCAA Men's Division I Basketball Championship, NCAA men's Division I basketball tournament in March, also known as "March Madness."

Ice hockey is the fourth leading professional team sport. Always a mainstay of Great Lakes and

American football, known in the United States as simply "football," now attracts more television viewers than any other sport and is considered to be the most popular sport in the United States. The 32-team National Football League (NFL) is the most popular professional American football league.

The National Football League differs from the other three Major professional sports leagues in the United States and Canada, major pro sports leagues in that each of its 32 teams plays one game a week over 18 weeks, for a total of 17 games with one Bye (sports), bye week for each team. The National Football League regular season, NFL season lasts from September to December, ending with the National Football League playoffs, playoffs and Super Bowl in January and February.

Its championship game, the Super Bowl, has often been the highest rated television show, and it has an audience of over 100 million viewers annually.

College football also attracts audiences of millions. Some communities, particularly in rural areas, place great emphasis on their local high school football team. American football games usually include cheerleaders and marching bands, which aim to raise school spirit and entertain the crowd at halftime.

Basketball is another major sport, represented professionally by the National Basketball Association. It was invented in Springfield, Massachusetts in 1891, by Canadian-born physical education teacher James Naismith. College basketball is also popular, due in large part to the NCAA Men's Division I Basketball Championship, NCAA men's Division I basketball tournament in March, also known as "March Madness."

Ice hockey is the fourth leading professional team sport. Always a mainstay of Great Lakes and  Lacrosse is a team sport of Native Americans in the United States, American and First Nations in Canada, Canadian Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Native American origin and is the fastest growing sport in the United States. Lacrosse is most popular in the East Coast area. National Lacrosse League, NLL and Major League Lacrosse, MLL are the national box lacrosse, box and outdoor lacrosse leagues, respectively, and have increased their following in recent years. Also, many of the top Division I college lacrosse teams draw upwards of 7–10,000 for a game, especially in the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and

Lacrosse is a team sport of Native Americans in the United States, American and First Nations in Canada, Canadian Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Native American origin and is the fastest growing sport in the United States. Lacrosse is most popular in the East Coast area. National Lacrosse League, NLL and Major League Lacrosse, MLL are the national box lacrosse, box and outdoor lacrosse leagues, respectively, and have increased their following in recent years. Also, many of the top Division I college lacrosse teams draw upwards of 7–10,000 for a game, especially in the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and

Homecoming is an annual tradition of the United States. People, towns, high schools and colleges come together, usually in late September or early October, to welcome back former residents and alumni. It is built around a central event, such as a banquet, a parade, and most often, a game of American football, or, on occasion, basketball, wrestling or ice hockey. When celebrated by schools, the activities vary. However, they usually consist of a football game, played on the school's home football field, activities for students and alumni, a parade featuring the school's marching band and sports teams, and the coronation of a Homecoming Queen.

American high schools commonly field football, basketball, baseball, softball, volleyball, soccer, golf, swimming, track and field, and cross-country teams as well.

Homecoming is an annual tradition of the United States. People, towns, high schools and colleges come together, usually in late September or early October, to welcome back former residents and alumni. It is built around a central event, such as a banquet, a parade, and most often, a game of American football, or, on occasion, basketball, wrestling or ice hockey. When celebrated by schools, the activities vary. However, they usually consist of a football game, played on the school's home football field, activities for students and alumni, a parade featuring the school's marching band and sports teams, and the coronation of a Homecoming Queen.

American high schools commonly field football, basketball, baseball, softball, volleyball, soccer, golf, swimming, track and field, and cross-country teams as well.

The cuisine of the United States is extremely diverse, owing to the vastness of the country, the relatively large population (1/3 of a billion people) and the number of native and immigrant influences. Mainstream American culinary arts are similar to those in other Western countries. Wheat and corn are the primary cereal grains. Traditional American cuisine uses ingredients such as turkey (bird), turkey, potatoes, sweet potatoes, maize, corn (maize), squash (plant), squash, and maple syrup, as well as indigenous foods employed by American Indians and early European settlers, African slaves, and their descendants.

Iconic American dishes such as apple pie, doughnut, donuts, fried chicken, pizza, hamburgers, and hot dogs derive from the recipes of various immigrants and domestic innovations. French fries, Mexican dishes such as burritos and tacos, and pasta dishes freely adapted from Italian sources are consumed.

The types of food served at home vary greatly and depend upon the region of the country and the family's own cultural heritage. Recent immigrants tend to eat food similar to that of their country of origin, and Americanization, Americanized versions of these cultural foods, such as American Chinese cuisine or Italian-American cuisine often eventually appear. Vietnamese cuisine, Korean cuisine and Thai cuisine in authentic forms are often readily available in large cities. German cuisine has a profound impact on American cuisine, especially mid-western cuisine; potatoes, noodles, roasts, stews, cakes, and other pastries are the most iconic ingredients in both cuisines. Dishes such as the hamburger, pot roast, baked ham, and hot dogs are examples of American dishes derived from German cuisine.

The cuisine of the United States is extremely diverse, owing to the vastness of the country, the relatively large population (1/3 of a billion people) and the number of native and immigrant influences. Mainstream American culinary arts are similar to those in other Western countries. Wheat and corn are the primary cereal grains. Traditional American cuisine uses ingredients such as turkey (bird), turkey, potatoes, sweet potatoes, maize, corn (maize), squash (plant), squash, and maple syrup, as well as indigenous foods employed by American Indians and early European settlers, African slaves, and their descendants.

Iconic American dishes such as apple pie, doughnut, donuts, fried chicken, pizza, hamburgers, and hot dogs derive from the recipes of various immigrants and domestic innovations. French fries, Mexican dishes such as burritos and tacos, and pasta dishes freely adapted from Italian sources are consumed.

The types of food served at home vary greatly and depend upon the region of the country and the family's own cultural heritage. Recent immigrants tend to eat food similar to that of their country of origin, and Americanization, Americanized versions of these cultural foods, such as American Chinese cuisine or Italian-American cuisine often eventually appear. Vietnamese cuisine, Korean cuisine and Thai cuisine in authentic forms are often readily available in large cities. German cuisine has a profound impact on American cuisine, especially mid-western cuisine; potatoes, noodles, roasts, stews, cakes, and other pastries are the most iconic ingredients in both cuisines. Dishes such as the hamburger, pot roast, baked ham, and hot dogs are examples of American dishes derived from German cuisine.

Different regions of the United States have their own cuisine and styles of cooking. The states of Louisiana and Mississippi, for example, are known for their Cajun cuisine, Cajun and Louisiana Creole cuisine, Creole cooking. Cajun and Creole cooking are influenced by French, Acadian, and Haitian cooking, although the dishes themselves are original and unique. Examples include Crawfish etouffee, Crawfish Étouffée, Red beans and rice, seafood or chicken gumbo, jambalaya, and boudin. Italian, German, Hungarian, and Chinese influences, traditional Native American, Caribbean, Mexican, and Greek dishes have also diffused into the general American repertoire. It is not uncommon for a "middle-class" family from "Middle America (United States), middle America" to eat, for example, restaurant pizza, home-made pizza, enchiladas con carne, chicken paprikash, Beef Stroganoff, beef stroganoff, and bratwurst with sauerkraut for dinner throughout a single week.

Soul food, mostly the same as food eaten by white southerners, developed by southern African slaves, and their free descendants, is popular around the South and among many

Different regions of the United States have their own cuisine and styles of cooking. The states of Louisiana and Mississippi, for example, are known for their Cajun cuisine, Cajun and Louisiana Creole cuisine, Creole cooking. Cajun and Creole cooking are influenced by French, Acadian, and Haitian cooking, although the dishes themselves are original and unique. Examples include Crawfish etouffee, Crawfish Étouffée, Red beans and rice, seafood or chicken gumbo, jambalaya, and boudin. Italian, German, Hungarian, and Chinese influences, traditional Native American, Caribbean, Mexican, and Greek dishes have also diffused into the general American repertoire. It is not uncommon for a "middle-class" family from "Middle America (United States), middle America" to eat, for example, restaurant pizza, home-made pizza, enchiladas con carne, chicken paprikash, Beef Stroganoff, beef stroganoff, and bratwurst with sauerkraut for dinner throughout a single week.

Soul food, mostly the same as food eaten by white southerners, developed by southern African slaves, and their free descendants, is popular around the South and among many

File:Thanksgiving Dinner Alc2.jpg, Traditional Thanksgiving dinner with turkey, dressing, sweet potatoes, and cranberry sauce

File:Quail 07 bg 041506.jpg, A cream-based New England chowder, traditionally made with clams and potatoes

File:Fried Chicken (Unsplash).jpg, Fried chicken, a southern dish consisting of chicken pieces that have been coated with seasoned flour or batter and deep fried

File:Jambalaya.jpg, Creole Jambalaya with shrimp, ham, tomato, and Andouille sausage

File:Flickr wordridden 3397801155--Chicken fried steak.jpg, Chicken Fried Steak (or Country Fried Steak)

File:California club pizza.jpg, California-style pizza, California club pizza with avocados and tomatoes

File:Hoagie Hero Sub Sandwich.jpg, A submarine sandwich, which includes a variety of Italian luncheon meats

File:Dennysbreakfast.jpg, American breakfast, American style breakfast with pancakes, maple syrup, breakfast sausage, sausage links, bacon strips, and fried eggs

File:Flint coney island.jpg, A hot dog sausage topped with beef chili, white onions and mustard

File:BBQ Pulled Pork.jpg, A barbecue Pulled pork, pulled-pork sandwich with a side of coleslaw

File:Apple cobbler.jpg, An apple cobbler dessert

Family arrangements in the United States reflect the nature of contemporary Society of the United States, American society. The nuclear family is an idealized version of what most people think when they think of family. The classic nuclear family is a man and a woman, united in marriage, with one or more biological children. Today, a person may grow up in a single-parent family, go on to marry and live in a childfree couple arrangement, then get divorced, live as a single for a couple of years, remarry, have children and live in a nuclear family arrangement.

Family arrangements in the United States reflect the nature of contemporary Society of the United States, American society. The nuclear family is an idealized version of what most people think when they think of family. The classic nuclear family is a man and a woman, united in marriage, with one or more biological children. Today, a person may grow up in a single-parent family, go on to marry and live in a childfree couple arrangement, then get divorced, live as a single for a couple of years, remarry, have children and live in a nuclear family arrangement.

Marriage laws are established by individual states. The typical wedding involves a couple proclaiming their commitment to one another in front of their close relatives and friends, often presided over by a religious figure such as a minister, priest, or rabbi, depending upon the faith of the couple. In traditional Christian ceremonies, the bride's father will "give away" (handoff) the bride to the groom. Secular weddings are also common, often presided over by a judge, Justice of the Peace, or other municipal officials. Same-sex marriage is legal in all states.

Divorce is the province of state governments, so divorce law varies from state to state. Prior to the 1970s, divorcing spouses had to allege that the other spouse was guilty of a crime or sin like abandonment or adultery; when spouses simply could not get along, lawyers were forced to manufacture "uncontested" divorces. The no-fault divorce revolution began in 1969 in California; New York and South Dakota were the No-fault divorce#The adoption of no-fault divorce laws by the other states, last states to begin allowing no-fault divorce. No-fault divorce on the grounds of "irreconcilable differences" is now available in all states. However, many states have recently required separation periods prior to a formal divorce decree.

State law provides for child support where children are involved, and sometimes for alimony. "Married adults now divorce two-and-a-half times as often as adults did 20 years ago and four times as often as they did 50 years ago... between 40% and 60% of ''new'' marriages will eventually end in divorce. The probability within... the first five years is 20%, and the probability of its ending within the first 10 years is 33%... Perhaps 25% of children (ages 16 and under) live with a stepparent." The median length for a marriage in the U.S. today is 11 years with 90% of all divorces being settled out of court.

Marriage laws are established by individual states. The typical wedding involves a couple proclaiming their commitment to one another in front of their close relatives and friends, often presided over by a religious figure such as a minister, priest, or rabbi, depending upon the faith of the couple. In traditional Christian ceremonies, the bride's father will "give away" (handoff) the bride to the groom. Secular weddings are also common, often presided over by a judge, Justice of the Peace, or other municipal officials. Same-sex marriage is legal in all states.

Divorce is the province of state governments, so divorce law varies from state to state. Prior to the 1970s, divorcing spouses had to allege that the other spouse was guilty of a crime or sin like abandonment or adultery; when spouses simply could not get along, lawyers were forced to manufacture "uncontested" divorces. The no-fault divorce revolution began in 1969 in California; New York and South Dakota were the No-fault divorce#The adoption of no-fault divorce laws by the other states, last states to begin allowing no-fault divorce. No-fault divorce on the grounds of "irreconcilable differences" is now available in all states. However, many states have recently required separation periods prior to a formal divorce decree.

State law provides for child support where children are involved, and sometimes for alimony. "Married adults now divorce two-and-a-half times as often as adults did 20 years ago and four times as often as they did 50 years ago... between 40% and 60% of ''new'' marriages will eventually end in divorce. The probability within... the first five years is 20%, and the probability of its ending within the first 10 years is 33%... Perhaps 25% of children (ages 16 and under) live with a stepparent." The median length for a marriage in the U.S. today is 11 years with 90% of all divorces being settled out of court.

Historically, Americans mainly lived in a rural environment, with a few important cities of moderate size.

American cities with housing prices near the national median have also been losing the Household income in the United States, middle income neighborhoods, those with median income between 80% and 120% of the metropolitan area's median household income. Here, the more affluent members of the middle-class, who are also often referred to as being professional or upper middle-class, have left in search of larger homes in more exclusive suburbs. This trend is largely attributed to the ''American middle-class#Middle-class squeeze, Middle-class squeeze'', which has caused a starker distinction between the American middle-class#statistical middle class, statistical middle class and the more privileged members of the American middle class, middle class. In more expensive areas such as California, however, another trend has been taking place where an influx of more affluent middle-class households has displaced those in the actual middle of society and converted former American middle-class#statistical middle class, middle-middle-class neighborhoods into Upper middle-class#American upper middle-class, upper-middle-class neighborhoods.

Historically, Americans mainly lived in a rural environment, with a few important cities of moderate size.

American cities with housing prices near the national median have also been losing the Household income in the United States, middle income neighborhoods, those with median income between 80% and 120% of the metropolitan area's median household income. Here, the more affluent members of the middle-class, who are also often referred to as being professional or upper middle-class, have left in search of larger homes in more exclusive suburbs. This trend is largely attributed to the ''American middle-class#Middle-class squeeze, Middle-class squeeze'', which has caused a starker distinction between the American middle-class#statistical middle class, statistical middle class and the more privileged members of the American middle class, middle class. In more expensive areas such as California, however, another trend has been taking place where an influx of more affluent middle-class households has displaced those in the actual middle of society and converted former American middle-class#statistical middle class, middle-middle-class neighborhoods into Upper middle-class#American upper middle-class, upper-middle-class neighborhoods.

The rise of suburbs and the need for workers to commute to cities brought about the popularity of automobiles. In 2001, 90% of Americans drove to work by car.Highlights of the 2001 National Household Travel Survey

The rise of suburbs and the need for workers to commute to cities brought about the popularity of automobiles. In 2001, 90% of Americans drove to work by car.Highlights of the 2001 National Household Travel Survey

, Bureau of Transportation Statistics, U.S. Department of Transportation, accessed May 21, 2006 Lower energy and land costs favor the production of relatively large, powerful cars. The culture in the 1950s and 1960s often catered to the automobile with motels and drive-in restaurants. Outside of the relatively few urban areas, it is considered a necessity for most Americans to own and drive cars. New York City is the only locality in the United States where more than half of all households do not own a car. In the 1950s and 1960s subcultures began to arise around the modification and racing of American automobiles and converting them into hot rods. Later, in the late-1960s and early-1970s Detroit manufacturers began making muscle cars and pony cars to cater to the needs of wealthier Americans seeking hot rod style, performance and appeal.

Though most Americans in the 21st century identify themselves as American middle class, middle class, American society and its culture are considerably fragmented. Social class, generally described as a combination of Educational attainment in the United States, educational attainment, Income in the United States, income and occupational prestige, is one of the greatest cultural influences in America. Nearly all cultural aspects of mundane interactions and consumer behavior in the U.S. are guided by a person's location within the country's Social structure of the United States, social structure.

Distinct lifestyles, consumption patterns and values are associated with different classes. Early sociologist-economist Thorstein Veblen, for example, said that those at the top of the societal hierarchy engage in conspicuous leisure and conspicuous consumption. American upper class, Upper class Americans commonly have elite Ivy League Educational attainment in the United States, educations and are traditionally members of exclusive clubs and fraternities with connections to high society (social class), high society, distinguished by their enormous incomes derived from their wealth in assets. The upper-class lifestyle and values often overlap with that of the Managerial Class, upper middle class, with main differences being higher attention to security and privacy in home life and high regard for philanthropy (i.e. the "Donor Class") and the arts. Due to their large wealth (inherited or accrued over a lifetime of investments) and lavish, leisurely lifestyles, the upper class are more prone to idleness. The upper middle-class, or the "working rich", commonly identify education and being cultured as prime values, similar to the upper class. Persons in this particular Social structure of the United States, social class tend to speak in a more direct manner that projects authority, knowledge and thus credibility. They often tend to engage in the consumption of so-called mass luxuries, such as designer label clothing. A strong preference for natural materials, organic foods, and a strong health consciousness tend to be prominent features of the upper middle-class. American middle-class individuals in general value expanding one's horizon, partially because they are more educated and can afford greater leisure and travel. Working-class individuals take great pride in doing what they consider to be "real work" and keep very close-knit kin networks that serve as a safeguard against frequent economic instability.

Though most Americans in the 21st century identify themselves as American middle class, middle class, American society and its culture are considerably fragmented. Social class, generally described as a combination of Educational attainment in the United States, educational attainment, Income in the United States, income and occupational prestige, is one of the greatest cultural influences in America. Nearly all cultural aspects of mundane interactions and consumer behavior in the U.S. are guided by a person's location within the country's Social structure of the United States, social structure.

Distinct lifestyles, consumption patterns and values are associated with different classes. Early sociologist-economist Thorstein Veblen, for example, said that those at the top of the societal hierarchy engage in conspicuous leisure and conspicuous consumption. American upper class, Upper class Americans commonly have elite Ivy League Educational attainment in the United States, educations and are traditionally members of exclusive clubs and fraternities with connections to high society (social class), high society, distinguished by their enormous incomes derived from their wealth in assets. The upper-class lifestyle and values often overlap with that of the Managerial Class, upper middle class, with main differences being higher attention to security and privacy in home life and high regard for philanthropy (i.e. the "Donor Class") and the arts. Due to their large wealth (inherited or accrued over a lifetime of investments) and lavish, leisurely lifestyles, the upper class are more prone to idleness. The upper middle-class, or the "working rich", commonly identify education and being cultured as prime values, similar to the upper class. Persons in this particular Social structure of the United States, social class tend to speak in a more direct manner that projects authority, knowledge and thus credibility. They often tend to engage in the consumption of so-called mass luxuries, such as designer label clothing. A strong preference for natural materials, organic foods, and a strong health consciousness tend to be prominent features of the upper middle-class. American middle-class individuals in general value expanding one's horizon, partially because they are more educated and can afford greater leisure and travel. Working-class individuals take great pride in doing what they consider to be "real work" and keep very close-knit kin networks that serve as a safeguard against frequent economic instability.

Working-class Americans and many of those in the middle class may also face occupation alienation. In contrast to upper-middle-class professionals who are mostly hired to conceptualize, supervise, and share their thoughts, many Americans have little autonomy or creative latitude in the workplace. As a result, white collar professionals tend to be significantly more satisfied with their work. In 2006, Elizabeth Warren presented her article entitled "The Middle Class on the Precipice", stating that individuals in the center of the income strata, who may still identify as middle class, have faced increasing economic insecurity, supporting the idea of a working-class majority.

Political behavior is affected by class; more affluent individuals are more likely to vote, and education and income affect whether individuals tend to vote for the Democratic or Republican party. Income in the United States, Income also had a significant impact on health as those with higher Income in the United States, incomes had better access to health care facilities, higher life expectancy, lower infant mortality rate and increased health consciousness. This is particularly noticeable with black voters who are often socially conservative, yet overwhelmingly vote Democratic.

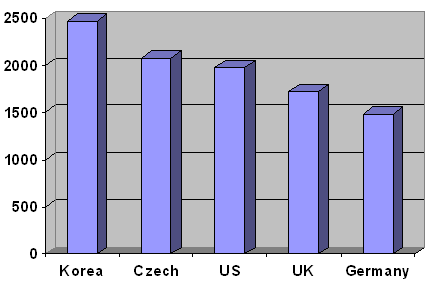

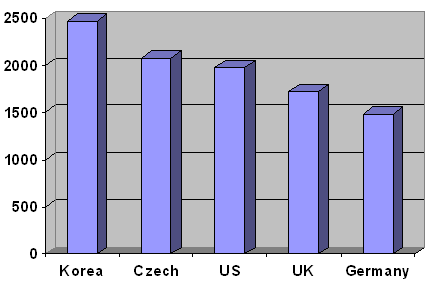

In the United States occupation is one of the prime factors of Social structure of the United States, social class and is closely linked to an individual's identity. The average workweek in the U.S. for those employed full-time was 42.9 hours long with 30% of the population working more than 40 hours a week. The Average American worker earned $16.64 an hour in the first two quarters of 2006. Overall Americans worked more than their counterparts in other developed post-industrial nations. While the average worker in Denmark enjoyed 30 days of vacation annually, the average American had 16 annual vacation days.

In 2000 the average American worked 1,978 hours per year, 500 hours more than the average German, yet 100 hours less than the average Czech Republic, Czech. Overall the U.S. labor force is one of the most productive in the world, largely due to its workers working more than those in any other post-industrial country (excluding South Korea). Americans generally hold working and being productive in high regard; being busy and working extensively may also serve as the means to obtain esteem.

Working-class Americans and many of those in the middle class may also face occupation alienation. In contrast to upper-middle-class professionals who are mostly hired to conceptualize, supervise, and share their thoughts, many Americans have little autonomy or creative latitude in the workplace. As a result, white collar professionals tend to be significantly more satisfied with their work. In 2006, Elizabeth Warren presented her article entitled "The Middle Class on the Precipice", stating that individuals in the center of the income strata, who may still identify as middle class, have faced increasing economic insecurity, supporting the idea of a working-class majority.

Political behavior is affected by class; more affluent individuals are more likely to vote, and education and income affect whether individuals tend to vote for the Democratic or Republican party. Income in the United States, Income also had a significant impact on health as those with higher Income in the United States, incomes had better access to health care facilities, higher life expectancy, lower infant mortality rate and increased health consciousness. This is particularly noticeable with black voters who are often socially conservative, yet overwhelmingly vote Democratic.

In the United States occupation is one of the prime factors of Social structure of the United States, social class and is closely linked to an individual's identity. The average workweek in the U.S. for those employed full-time was 42.9 hours long with 30% of the population working more than 40 hours a week. The Average American worker earned $16.64 an hour in the first two quarters of 2006. Overall Americans worked more than their counterparts in other developed post-industrial nations. While the average worker in Denmark enjoyed 30 days of vacation annually, the average American had 16 annual vacation days.

In 2000 the average American worked 1,978 hours per year, 500 hours more than the average German, yet 100 hours less than the average Czech Republic, Czech. Overall the U.S. labor force is one of the most productive in the world, largely due to its workers working more than those in any other post-industrial country (excluding South Korea). Americans generally hold working and being productive in high regard; being busy and working extensively may also serve as the means to obtain esteem.

Race in the United States is based on physical characteristics, such as skin color, and has played an essential part in shaping American society even before the nation's conception. Until the civil rights movement of the 1960s, racial minorities in the United States faced institutionalized discrimination and both social and economic marginalization. Today the U.S. Department of Commerce's Bureau of the Census recognizes four races, Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Native American, African American, Asian American, Asian and White American, White (European American). According to the U.S. government, Hispanic Americans do not constitute a race, but rather an ethnic group. During the 2000 U.S. Census, Whites made up 75.1% of the population; those who are Hispanic or Latino constituted the nation's prevalent minority with 12.5% of the population. African Americans made up 12.3% of the total population, 3.6% were Asian American and 0.7% were Native American.

The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution—ratified on December 6, 1865—abolished slavery in the United States. The northern states had outlawed slavery in their territory in the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth-century, though their industrial economies relied on raw materials produced by slaves. Following the Reconstruction period in the 1870s, racist legislation emerged in the Southern states named the Jim Crow laws that provided for legal segregation. Lynching was practiced throughout the U.S., including in the Northern states, until the 1930s, while continuing well into the civil rights movement in the South.

Chinese Americans were earlier marginalized as well during a significant proportion of U.S. history. Between 1882 and 1943 the United States instituted the Chinese Exclusion Act (United States), Chinese Exclusion Act barring all Chinese immigrants from entering the United States. During the Second World War, roughly 120,000 Japanese Americans, 62% of whom were U.S. citizens, were imprisoned in Japanese American internment, Japanese internment camps by the U.S. government following the attacks on Pearl Harbor, an American military base, by Japanese troops.

Due to exclusion from or marginalization by earlier mainstream society, there emerged a unique subculture among the racial minorities in the United States. During the 1920s, Harlem, New York became home to the Harlem Renaissance. Music styles such as

Race in the United States is based on physical characteristics, such as skin color, and has played an essential part in shaping American society even before the nation's conception. Until the civil rights movement of the 1960s, racial minorities in the United States faced institutionalized discrimination and both social and economic marginalization. Today the U.S. Department of Commerce's Bureau of the Census recognizes four races, Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Native American, African American, Asian American, Asian and White American, White (European American). According to the U.S. government, Hispanic Americans do not constitute a race, but rather an ethnic group. During the 2000 U.S. Census, Whites made up 75.1% of the population; those who are Hispanic or Latino constituted the nation's prevalent minority with 12.5% of the population. African Americans made up 12.3% of the total population, 3.6% were Asian American and 0.7% were Native American.

The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution—ratified on December 6, 1865—abolished slavery in the United States. The northern states had outlawed slavery in their territory in the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth-century, though their industrial economies relied on raw materials produced by slaves. Following the Reconstruction period in the 1870s, racist legislation emerged in the Southern states named the Jim Crow laws that provided for legal segregation. Lynching was practiced throughout the U.S., including in the Northern states, until the 1930s, while continuing well into the civil rights movement in the South.

Chinese Americans were earlier marginalized as well during a significant proportion of U.S. history. Between 1882 and 1943 the United States instituted the Chinese Exclusion Act (United States), Chinese Exclusion Act barring all Chinese immigrants from entering the United States. During the Second World War, roughly 120,000 Japanese Americans, 62% of whom were U.S. citizens, were imprisoned in Japanese American internment, Japanese internment camps by the U.S. government following the attacks on Pearl Harbor, an American military base, by Japanese troops.

Due to exclusion from or marginalization by earlier mainstream society, there emerged a unique subculture among the racial minorities in the United States. During the 1920s, Harlem, New York became home to the Harlem Renaissance. Music styles such as

Throughout most of the country's history before and after its independence, the majority race in the United States has been Caucasian—aided by historic restrictions on citizenship and immigration—and the largest racial minority has been African-Americans, most of whom are descended from slaves. This relationship has historically been the most important one since the founding of the United States. Slavery existed in the United States at the time of the country's formation in the 1770s. The U.S. banned the importation of slaves in 1808, and the Slavery in the United States#Domestic slave trade and forced migration, domestic slave trade, which broke up many families, became a major economic activity which lasted until the 1860s. Before the American Civil War, List of presidents of the United States who owned slaves, eight serving presidents had owned slaves, and almost four million black people remained Slavery in the United States, enslaved in the South. Slavery was partially abolished by the Emancipation Proclamation issued by the president Abraham Lincoln in 1862 for slaves in the Southeastern United States during the Civil War. Slavery was rendered illegal by the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Jim Crow Laws prevented full use of African American citizenship until the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed official or legal segregation in public places or limited access to minorities.

Throughout most of the country's history before and after its independence, the majority race in the United States has been Caucasian—aided by historic restrictions on citizenship and immigration—and the largest racial minority has been African-Americans, most of whom are descended from slaves. This relationship has historically been the most important one since the founding of the United States. Slavery existed in the United States at the time of the country's formation in the 1770s. The U.S. banned the importation of slaves in 1808, and the Slavery in the United States#Domestic slave trade and forced migration, domestic slave trade, which broke up many families, became a major economic activity which lasted until the 1860s. Before the American Civil War, List of presidents of the United States who owned slaves, eight serving presidents had owned slaves, and almost four million black people remained Slavery in the United States, enslaved in the South. Slavery was partially abolished by the Emancipation Proclamation issued by the president Abraham Lincoln in 1862 for slaves in the Southeastern United States during the Civil War. Slavery was rendered illegal by the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Jim Crow Laws prevented full use of African American citizenship until the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed official or legal segregation in public places or limited access to minorities.

Relations between white Americans and other racial or ethnic groups have been a constant source of tension. According to Professor Leland T. Saito: "Throughout the history of the United States, race has been used by whites for legitimizing and creating difference and social, economic and political exclusion." The Naturalization Act of 1790 limited U.S. citizenship to whites only. Relations between whites and Native Americans was a significant issue. A justification for the policy of conquest and subjugation of the Indigenous people emanated from the stereotyped perceptions of all Native Americans as "merciless Indian savages" (as described in the United States Declaration of Independence).

In 1882, in response to Chinese immigration due to the California Gold Rush, Gold Rush and the labor needed for the Transcontinental Railroad, the U.S. signed into law the Chinese Exclusion Act which banned immigration by Chinese people into the U.S. In the late 19th century, the growth of the Hispanic population in the U.S., fueled largely by Mexican immigration, generated debate over policies such as English as the official language and reform to immigration policies. The Immigration Act of 1924 established the National Origins Formula as the basis of U.S. immigration policy, largely to restrict immigration from Asia, Southern Europe, and Eastern Europe. According to the Office of the Historian of the U.S. Department of State, the purpose of the 1924 Act was "to preserve the ideal of U.S. homogeneity". In 1924, Indian-born Bhagat Singh Thind was twice denied citizenship as he was not deemed white. Marking a radical break from U.S. immigration policies of the past, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 opened entry to the U.S. to non-Germanic groups. This Act significantly altered the demographic mix in the U.S. as a result, creating a modern, diverse America.

A huge majority of Americans of all races disapprove of racism. Nevertheless, some Americans continue to hold negative racial/ethnic Stereotypes of groups within the United States, stereotypes about various racial and ethnic groups. Professor Imani Perry, of Princeton University, has argued that contemporary racism in the United States "is frequently unintentional or unacknowledged on the part of the actor", believing that racism mostly stems unconsciously from below the level of cognition.

Relations between white Americans and other racial or ethnic groups have been a constant source of tension. According to Professor Leland T. Saito: "Throughout the history of the United States, race has been used by whites for legitimizing and creating difference and social, economic and political exclusion." The Naturalization Act of 1790 limited U.S. citizenship to whites only. Relations between whites and Native Americans was a significant issue. A justification for the policy of conquest and subjugation of the Indigenous people emanated from the stereotyped perceptions of all Native Americans as "merciless Indian savages" (as described in the United States Declaration of Independence).

In 1882, in response to Chinese immigration due to the California Gold Rush, Gold Rush and the labor needed for the Transcontinental Railroad, the U.S. signed into law the Chinese Exclusion Act which banned immigration by Chinese people into the U.S. In the late 19th century, the growth of the Hispanic population in the U.S., fueled largely by Mexican immigration, generated debate over policies such as English as the official language and reform to immigration policies. The Immigration Act of 1924 established the National Origins Formula as the basis of U.S. immigration policy, largely to restrict immigration from Asia, Southern Europe, and Eastern Europe. According to the Office of the Historian of the U.S. Department of State, the purpose of the 1924 Act was "to preserve the ideal of U.S. homogeneity". In 1924, Indian-born Bhagat Singh Thind was twice denied citizenship as he was not deemed white. Marking a radical break from U.S. immigration policies of the past, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 opened entry to the U.S. to non-Germanic groups. This Act significantly altered the demographic mix in the U.S. as a result, creating a modern, diverse America.

A huge majority of Americans of all races disapprove of racism. Nevertheless, some Americans continue to hold negative racial/ethnic Stereotypes of groups within the United States, stereotypes about various racial and ethnic groups. Professor Imani Perry, of Princeton University, has argued that contemporary racism in the United States "is frequently unintentional or unacknowledged on the part of the actor", believing that racism mostly stems unconsciously from below the level of cognition.

It is customary for Americans to hold a Wake (ceremony), wake in a funeral home within a couple of days of the death of a loved one. The body of the deceased may be embalmed and dressed in fine clothing if there will be an open-casket Viewing (funeral), viewing. Traditional Jewish and Muslim practices include a ritual bath and no embalming. Friends, relatives and acquaintances gather, often from distant parts of the country, to "pay their last respects" to the deceased. Flowers are brought to the coffin and sometimes eulogy, eulogies, elegy, elegies, personal anecdotes or group prayers are recited. Otherwise, the attendees sit, stand or kneel in quiet contemplation or prayer. Kissing the corpse on the forehead is typical among Italian Americans and others. Condolences are also offered to the widow or widower and other close relatives.

It is customary for Americans to hold a Wake (ceremony), wake in a funeral home within a couple of days of the death of a loved one. The body of the deceased may be embalmed and dressed in fine clothing if there will be an open-casket Viewing (funeral), viewing. Traditional Jewish and Muslim practices include a ritual bath and no embalming. Friends, relatives and acquaintances gather, often from distant parts of the country, to "pay their last respects" to the deceased. Flowers are brought to the coffin and sometimes eulogy, eulogies, elegy, elegies, personal anecdotes or group prayers are recited. Otherwise, the attendees sit, stand or kneel in quiet contemplation or prayer. Kissing the corpse on the forehead is typical among Italian Americans and others. Condolences are also offered to the widow or widower and other close relatives.

A funeral may be held immediately afterward or the next day. The funeral ceremony varies according to religion and culture. American Catholics typically hold a Catholic funeral, funeral mass in a church, which sometimes takes the form of a Requiem mass. Jewish Americans may hold a service in a synagogue or temple. Pallbearers carry the coffin of the deceased to the hearse, which then proceeds in a procession to the place of final repose, usually a cemetery. The unique Jazz funeral of New Orleans features joyous and raucous music and dancing during the procession.

Mount Auburn Cemetery (founded in 1831) is known as "America's first garden cemetery." American cemetery, cemeteries created since are distinctive for their rural cemetery, park-like setting. Rows of grave (burial), graves are covered by lawns and are interspersed with trees and flowers. Headstones, mausoleums, statuary or simple plaques typically mark off the individual graves. Cremation is another common practice in the United States, though it is frowned upon by various religions. The ashes of the deceased are usually placed in an urn, which may be kept in a private house, or they are interred. Sometimes the ashes are released into the atmosphere. The "sprinkling" or "scattering" of the ashes may be part of an informal ceremony, often taking place at a scenic natural feature (a cliff, lake or mountain) that was favored by the deceased.

A funeral may be held immediately afterward or the next day. The funeral ceremony varies according to religion and culture. American Catholics typically hold a Catholic funeral, funeral mass in a church, which sometimes takes the form of a Requiem mass. Jewish Americans may hold a service in a synagogue or temple. Pallbearers carry the coffin of the deceased to the hearse, which then proceeds in a procession to the place of final repose, usually a cemetery. The unique Jazz funeral of New Orleans features joyous and raucous music and dancing during the procession.

Mount Auburn Cemetery (founded in 1831) is known as "America's first garden cemetery." American cemetery, cemeteries created since are distinctive for their rural cemetery, park-like setting. Rows of grave (burial), graves are covered by lawns and are interspersed with trees and flowers. Headstones, mausoleums, statuary or simple plaques typically mark off the individual graves. Cremation is another common practice in the United States, though it is frowned upon by various religions. The ashes of the deceased are usually placed in an urn, which may be kept in a private house, or they are interred. Sometimes the ashes are released into the atmosphere. The "sprinkling" or "scattering" of the ashes may be part of an informal ceremony, often taking place at a scenic natural feature (a cliff, lake or mountain) that was favored by the deceased.

American attitudes towards drugs and alcoholic beverages have evolved considerably throughout the country's history. In the 19th century, alcohol was readily available and consumed, and no laws restricted the use of other drugs. Attitudes on drug addiction started to change, resulting in the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act, Harrison Act, which eventually became proscriptive.

A movement to ban alcoholic beverages called the Temperance movement, emerged in the late 19th century. Several American Protestant religious groups and women's groups, such as the Women's Christian Temperance Union, supported the movement. In 1919, Prohibitionists succeeded in Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, amending the Constitution to prohibit the sale of alcohol. Although the Prohibition period did result in a 50% decrease in alcohol consumption, banning alcohol outright proved to be unworkable, as the previously legitimate distillery industry was replaced by criminal gangs that trafficked in alcohol. Prohibition Twenty-first Amendment to the United States Constitution, was repealed in 1933. States and localities retained the right to remain "dry", and to this day, dry county, a handful still do.

During the Vietnam War era, attitudes swung well away from prohibition. Commentators noted that an 18-year-old could be Conscription in the United States, drafted to war but could not buy a beer.

Since 1980, the trend has been toward greater restrictions on alcohol and drug use. The focus this time, however, has been to criminalize behaviors associated with alcohol, rather than attempt to prohibit consumption outright. New York was the first state to enact tough drunk-driving laws in 1980; since then all other states have followed suit. All states have also banned the purchase of alcoholic beverages by individuals under 21.

A "Just Say No to Drugs" movement replaced the more liberal ethos of the 1960s. This led to stricter drug laws and greater police latitude in drug cases. Drugs are, however, widely available, and 16% of Americans 12 and older used an illicit drug in 2012.

Since the 1990s, marijuana use has become increasingly tolerated in America, and a number of states allow the Medical cannabis in the United States, use of marijuana for medical purposes. In most states marijuana is still illegal without a medical prescription. Since the 2012 general election, voters in the District of Columbia and the states of Alaska, California, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, Nevada,

American attitudes towards drugs and alcoholic beverages have evolved considerably throughout the country's history. In the 19th century, alcohol was readily available and consumed, and no laws restricted the use of other drugs. Attitudes on drug addiction started to change, resulting in the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act, Harrison Act, which eventually became proscriptive.

A movement to ban alcoholic beverages called the Temperance movement, emerged in the late 19th century. Several American Protestant religious groups and women's groups, such as the Women's Christian Temperance Union, supported the movement. In 1919, Prohibitionists succeeded in Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, amending the Constitution to prohibit the sale of alcohol. Although the Prohibition period did result in a 50% decrease in alcohol consumption, banning alcohol outright proved to be unworkable, as the previously legitimate distillery industry was replaced by criminal gangs that trafficked in alcohol. Prohibition Twenty-first Amendment to the United States Constitution, was repealed in 1933. States and localities retained the right to remain "dry", and to this day, dry county, a handful still do.

During the Vietnam War era, attitudes swung well away from prohibition. Commentators noted that an 18-year-old could be Conscription in the United States, drafted to war but could not buy a beer.

Since 1980, the trend has been toward greater restrictions on alcohol and drug use. The focus this time, however, has been to criminalize behaviors associated with alcohol, rather than attempt to prohibit consumption outright. New York was the first state to enact tough drunk-driving laws in 1980; since then all other states have followed suit. All states have also banned the purchase of alcoholic beverages by individuals under 21.

A "Just Say No to Drugs" movement replaced the more liberal ethos of the 1960s. This led to stricter drug laws and greater police latitude in drug cases. Drugs are, however, widely available, and 16% of Americans 12 and older used an illicit drug in 2012.

Since the 1990s, marijuana use has become increasingly tolerated in America, and a number of states allow the Medical cannabis in the United States, use of marijuana for medical purposes. In most states marijuana is still illegal without a medical prescription. Since the 2012 general election, voters in the District of Columbia and the states of Alaska, California, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, Nevada,

Alexis de Tocqueville first noted, in 1835, the American attitude towards helping others in need. A 2011 Charities Aid Foundation study found that Americans were the first most willing to help a stranger and donate time and money in the world at 60%. Many low-level crimes are punished by assigning hours of "community service", a requirement that the offender perform volunteer work; some high schools also require community service to graduate. Since US citizens are required to attend jury duty, they can be jurors in legal proceedings.

Alexis de Tocqueville first noted, in 1835, the American attitude towards helping others in need. A 2011 Charities Aid Foundation study found that Americans were the first most willing to help a stranger and donate time and money in the world at 60%. Many low-level crimes are punished by assigning hours of "community service", a requirement that the offender perform volunteer work; some high schools also require community service to graduate. Since US citizens are required to attend jury duty, they can be jurors in legal proceedings.

From the time of its inception, the military played a decisive role in the history of the United States. A sense of national unity and identity was forged out of the victorious First Barbary War, Second Barbary War, and the War of 1812. Even so, the Founding Fathers of the United States, Founders were suspicious of a permanent military force and not until the outbreak of World War II did a large standing army become officially established. The National Security Act of 1947, adopted following World War II and during the onset of the Cold War, created the modern U.S. military framework; the Act merged previously Cabinet-level United States Department of War, Department of War and the United States Department of the Navy, Department of the Navy into the United States Department of Defense, National Military Establishment (renamed the Department of Defense in 1949), headed by the Secretary of Defense; and created the United States Department of the Air Force, Department of the Air Force and National Security Council.

The U.S. military is one of the largest militaries in terms of the number of personnel. It draws its manpower from a large pool of paid Volunteer military, volunteers; although Conscription in the United States, conscription has been used in the past in various times of both war and peace, it has not been used since 1972. As of 2011, the United States spends about $550 billion annually to fund its military forces, and appropriates approximately $160 billion to fund War on Terrorism, Overseas Contingency Operations. Put together, the United States constitutes roughly List of countries by military expenditures, 43 percent of the world's military expenditures. The U.S. armed forces as a whole possess large quantities of advanced and powerful equipment, along with widespread placement of forces around the world, giving them significant capabilities in both defense and power projection.

There is and has been a strong military culture among military veterans and currently serving military members.

From the time of its inception, the military played a decisive role in the history of the United States. A sense of national unity and identity was forged out of the victorious First Barbary War, Second Barbary War, and the War of 1812. Even so, the Founding Fathers of the United States, Founders were suspicious of a permanent military force and not until the outbreak of World War II did a large standing army become officially established. The National Security Act of 1947, adopted following World War II and during the onset of the Cold War, created the modern U.S. military framework; the Act merged previously Cabinet-level United States Department of War, Department of War and the United States Department of the Navy, Department of the Navy into the United States Department of Defense, National Military Establishment (renamed the Department of Defense in 1949), headed by the Secretary of Defense; and created the United States Department of the Air Force, Department of the Air Force and National Security Council.

The U.S. military is one of the largest militaries in terms of the number of personnel. It draws its manpower from a large pool of paid Volunteer military, volunteers; although Conscription in the United States, conscription has been used in the past in various times of both war and peace, it has not been used since 1972. As of 2011, the United States spends about $550 billion annually to fund its military forces, and appropriates approximately $160 billion to fund War on Terrorism, Overseas Contingency Operations. Put together, the United States constitutes roughly List of countries by military expenditures, 43 percent of the world's military expenditures. The U.S. armed forces as a whole possess large quantities of advanced and powerful equipment, along with widespread placement of forces around the world, giving them significant capabilities in both defense and power projection.

There is and has been a strong military culture among military veterans and currently serving military members.

The United States has the largest prison population in the world, and the List of countries by incarceration rate, highest per-capita incarceration rate. One out of every 5 people imprisoned across the world is incarcerated in the U.S. Zero tolerance policies in the U.S. has contributed to its mass incarceration, with people in positions of authority required to impose a pre-determined punishment regardless of individual culpability. This pre-determined punishment, whether mild or severe, is always meted out.

Laws in the U.S. limit how people can use public streets as pedestrians can be arrested for jaywalking—the action of walking across a street at a place where it is not allowed. Punishments for jaywalking range from a fine to imprisonment.

In the U.S. the legal drinking age is 21, the highest in the world, and anyone under 21 operating a vehicle with any type of blood alcohol count, ie. having one drink, will be punished regardless of whether or not they are physically impaired during driving.

The United States has the largest prison population in the world, and the List of countries by incarceration rate, highest per-capita incarceration rate. One out of every 5 people imprisoned across the world is incarcerated in the U.S. Zero tolerance policies in the U.S. has contributed to its mass incarceration, with people in positions of authority required to impose a pre-determined punishment regardless of individual culpability. This pre-determined punishment, whether mild or severe, is always meted out.

Laws in the U.S. limit how people can use public streets as pedestrians can be arrested for jaywalking—the action of walking across a street at a place where it is not allowed. Punishments for jaywalking range from a fine to imprisonment.

In the U.S. the legal drinking age is 21, the highest in the world, and anyone under 21 operating a vehicle with any type of blood alcohol count, ie. having one drink, will be punished regardless of whether or not they are physically impaired during driving.

Customs & Culture in the U.S.

American Culture Education

Life in the USA: The Complete Guide for Immigrants and Americans

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20110627175126/http://www.commoncensus.org/ CommonCensus Map Project] – Identifying geographic spheres of influence {{DEFAULTSORT:Culture Of The United States American culture, Society of the United States, American studies Arts in the United States Entertainment in the United States

Asian American

Asian Americans are Americans of Asian ancestry (including naturalized Americans who are immigrants from specific regions in Asia and descendants of such immigrants). Although this term had historically been used for all the indigenous peopl ...

, African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

, Latin American

Latin Americans ( es, Latinoamericanos; pt, Latino-americanos; ) are the citizens of Latin American countries (or people with cultural, ancestral or national origins in Latin America). Latin American countries and their diasporas are multi-e ...

, and Native American peoples and their culture

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups ...

s. The United States has its own distinct social and cultural characteristics, such as dialect

The term dialect (from Latin , , from the Ancient Greek word , 'discourse', from , 'through' and , 'I speak') can refer to either of two distinctly different types of linguistic phenomena:

One usage refers to a variety of a language that is ...

, music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspe ...

, arts

The arts are a very wide range of human practices of creative expression, storytelling and cultural participation. They encompass multiple diverse and plural modes of thinking, doing and being, in an extremely broad range of media. Both ...

, social habits, cuisine

A cuisine is a style of cooking characterized by distinctive ingredients, techniques and dishes, and usually associated with a specific culture or geographic region. Regional food preparation techniques, customs, and ingredients combine to ...

, and folklore

Folklore is shared by a particular group of people; it encompasses the traditions common to that culture, subculture or group. This includes oral traditions such as tales, legends, proverbs and jokes. They include material culture, rangin ...

. The United States is ethnically diverse as a result of large-scale European immigration

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not natives or where they do not possess citizenship in order to settle as permanent residents or naturalized citizens. Commuters, tourists, ...

throughout its history, its hundreds of indigenous tribes and cultures, and through African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ensl ...

slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

followed by emancipation

Emancipation generally means to free a person from a previous restraint or legal disability. More broadly, it is also used for efforts to procure economic and social rights, political rights or equality, often for a specifically disenfranch ...

. America is an anglophone

Speakers of English are also known as Anglophones, and the countries where English is natively spoken by the majority of the population are termed the ''Anglosphere''. Over two billion people speak English , making English the largest language ...

country with a legal system derived from English common law

English law is the common law legal system of England and Wales, comprising mainly criminal law and civil law, each branch having its own courts and procedures.

Principal elements of English law

Although the common law has, historically, be ...

.

Origins, development, and spread

The European roots of the United States originate with the

The European roots of the United States originate with the English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

and Spanish settlers of colonial North America during British and Spanish rule. The varieties of English people, as opposed to the other peoples on the British Isles, were the overwhelming majority ethnic group in the 17th century (population of the colonies in 1700 was 250,000) and were 47.9% of percent of the total population of 3.9 million. They constituted 60% of the whites at the first census in 1790 (%: 3.5 Welsh, 8.5 Scotch Irish, 4.3 Scots, 4.7 Irish, 7.2 German, 2.7 Dutch, 1.7 French and 2 Swedish). The English ethnic group contributed to the major cultural and social mindset and attitudes that evolved into the American character. Of the total population in each colony, they numbered from 30% in Pennsylvania to 85% in Massachusetts. Large non-English immigrant populations from the 1720s to 1775, such as the Germans (100,000 or more), Scotch Irish (250,000), added enriched and modified the English cultural substrate. The religious outlook was some versions of Protestantism (1.6% of the population were English, German and Irish Catholics).

Jeffersonian democracy

Jeffersonian democracy, named after its advocate Thomas Jefferson, was one of two dominant political outlooks and movements in the United States from the 1790s to the 1820s. The Jeffersonians were deeply committed to American republicanism, whic ...

was a foundational American cultural innovation, which is still a core part of the country's identity."Mr. Jefferson and the giant moose: natural history in early America"Lee Alan Dugatkin. University of Chicago Press, 2009. , . University of Chicago Press, 2009. Chapter x. Thomas Jefferson's ''

Notes on the State of Virginia

''Notes on the State of Virginia'' (1785) is a book written by the American statesman, philosopher, and planter Thomas Jefferson. He completed the first version in 1781 and updated and enlarged the book in 1782 and 1783. It originated in Jeffers ...

'' was perhaps the first influential domestic cultural critique by an American and was written in reaction to the views of some influential Europeans that America's native flora and fauna (including humans) were degenerate.

Major cultural influences have been brought by historical immigration, especially from

Major cultural influences have been brought by historical immigration, especially from Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

in much of the country, Ireland and Italy in the Northeast, Japan in Hawaii. Latin American culture is especially pronounced in former Spanish areas but has also been introduced by immigration, as have Asian American cultures (especially in the Northeast and West Coast regions). Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean ...

culture has been increasingly introduced by immigration and is pronounced in many urban areas. Since the abolition of slavery, the Caribbean has been the source of the earliest and largest Black immigrant group, a significant source of growth of the Black population in the U.S. and has made major cultural impacts in education, music, sports and entertainment.