Alternative Law In Ireland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Alternative legal systems began to be used by

Alternative legal systems began to be used by

The Whiteboys were oath-bound secret societies in rural Ireland since the 1760s. The Threshers originated in

The Whiteboys were oath-bound secret societies in rural Ireland since the 1760s. The Threshers originated in

The new

The new

Alternative legal systems began to be used by

Alternative legal systems began to be used by Irish nationalist

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cu ...

organizations during the 1760s as a means of opposing British rule in Ireland

British rule in Ireland spanned several centuries and involved British control of parts, or entirety, of the island of Ireland. British involvement in Ireland began with the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169. Most of Ireland gained indepen ...

. Groups which enforced different laws included the Whiteboys

The Whiteboys ( ga, na Buachaillí Bána) were a secret Irish agrarian organisation in 18th-century Ireland which defended tenant-farmer land-rights for subsistence farming. Their name derives from the white smocks that members wore in their ...

, Repeal Association

The Repeal Association was an Irish mass membership political movement set up by Daniel O'Connell in 1830 to campaign for a repeal of the Acts of Union of 1800 between Great Britain and Ireland.

The Association's aim was to revert Ireland to th ...

, Ribbonmen

Ribbonism, whose supporters were usually called Ribbonmen, was a 19th-century popular movement of poor Catholics in Ireland. The movement was also known as Ribandism. The Ribbonmen were active against landlords and their agents, and opposed "Ora ...

, Irish National Land League

The Irish National Land League (Irish: ''Conradh na Talún'') was an Irish political organisation of the late 19th century which sought to help poor tenant farmers. Its primary aim was to abolish landlordism in Ireland and enable tenant farmer ...

, Irish National League

The Irish National League (INL) was a nationalist political party in Ireland. It was founded on 17 October 1882 by Charles Stewart Parnell as the successor to the Irish National Land League after this was suppressed. Whereas the Land League h ...

, United Irish League

The United Irish League (UIL) was a nationalist political party in Ireland, launched 23 January 1898 with the motto ''"The Land for the People"''. Its objective to be achieved through agrarian agitation and land reform, compelling larger grazi ...

, Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Gri ...

, and the Irish Republic

The Irish Republic ( ga, Poblacht na hÉireann or ) was an unrecognised revolutionary state that declared its independence from the United Kingdom in January 1919. The Republic claimed jurisdiction over the whole island of Ireland, but by ...

during the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

. These alternative justice systems were connected to the agrarian protest movements which sponsored them and filled the gap left by the official authority, which never had the popular support or legitimacy which it needed to govern effectively. Opponents of British rule in Ireland sought to create an alternative system, based on Irish (rather than English) law, which would eventually supplant British authority.

Background

British law

The United Kingdom has four legal systems, each of which derives from a particular geographical area for a variety of historical reasons: English and Welsh law, Scots law, Northern Ireland law, and, since 2007, purely Welsh law (as a result of ...

, a chief means of enforcing British rule in Ireland

British rule in Ireland spanned several centuries and involved British control of parts, or entirety, of the island of Ireland. British involvement in Ireland began with the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169. Most of Ireland gained indepen ...

, was viewed as a foreign imposition rather than a legitimate authority. From the Anglo-Norman invasion to the beginning of the seventeenth century, common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omnipresen ...

coexisted with the indigenous Brehon law. The former predominated in English-controlled areas, and the latter in other regions; in some places, both systems coexisted. The law was written and court proceedings were held in English, at a time when Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

was the sole language of most Irish people. During the sixteenth century, the surrender and regrant

During the Tudor conquest of Ireland (c.1540–1603), "surrender and regrant" was the legal mechanism by which Irish clans were to be converted from a power structure rooted in clan and kin loyalties, to a late-feudal system under the English l ...

system was intended to co-opt Gaelic chieftains and replace Gaelic customs with English property law. The Penal Laws restricted the civil rights of Catholics until they were repealed during the 1830s. British land law enforced the property rights

The right to property, or the right to own property (cf. ownership) is often classified as a human right for natural persons regarding their possessions. A general recognition of a right to private property is found more rarely and is typically ...

of landowners, ignoring Irish customs such as tenant-right

Tenant-right is a term in the common law system expressing the right to compensation which a tenant has, either by custom or by law, against his landlord for improvements at the termination of his tenancy.

In England, it was governed for the most ...

. The magistrates' court

A magistrates' court is a lower court where, in several jurisdictions, all criminal proceedings start. Also some civil matters may be dealt with here, such as family proceedings.

Courts

* Magistrates' court (England and Wales)

* Magistrate's Cour ...

s were run by unpaid landlords and other members of the Protestant Ascendancy

The ''Protestant Ascendancy'', known simply as the ''Ascendancy'', was the political, economic, and social domination of Ireland between the 17th century and the early 20th century by a minority of landowners, Protestant clergy, and members of th ...

, rather than salaried civil servants. Trust in the judicial system was further eroded by the wrongful conviction and execution of Maolra Seoighe

Maolra Seoighe (English: ''Myles Joyce''), Cappancreha, County Galway, was a man who was wrongfully convicted and hanged on 15 December 1882. He was found guilty of the Maamtrasna Murders and was sentenced to death. The case was heard in English ...

, a monolingual Irish speaker who could not understand the court proceedings, for the 1882 Maamtrasna murders

Maolra Seoighe (English: ''Myles Joyce''), Cappancreha, County Galway, was a man who was wrongfully convicted and hanged on 15 December 1882. He was found guilty of the Maamtrasna Murders and was sentenced to death. The case was heard in English ...

. The British government never had the support or legitimacy it needed to effectively govern Ireland, which led to the emergence of alternative systems to fill that gap.

Unwritten law

The "unwritten law" or "unwritten agrarian code" was a deep-rooted idea among Irish smallholders that access to land for subsistence farming was a human right which superseded property rights and, regardless of titular ownership, the right to use land was hereditary and not based on the ability to pay rent. This concept had parallels in Brehon law, which did not recognize absolute property rights. Even a lord'sdemesne

A demesne ( ) or domain was all the land retained and managed by a lord of the manor under the feudal system for his own use, occupation, or support. This distinguished it from land sub-enfeoffed by him to others as sub-tenants. The concept or ...

technically belonged to his entire sept

A sept is a division of a family, especially of a Scottish or Irish family. The term is used in both Scotland and Ireland, where it may be translated as ''sliocht'', meaning "progeny" or "seed", which may indicate the descendants of a person ( ...

. It was based on the idea that the land of Ireland rightfully belonged to the Irish people, but had been stolen by English invaders who claimed it by the right of conquest

The right of conquest is a right of ownership to land after immediate possession via force of arms. It was recognized as a principle of international law that gradually deteriorated in significance until its proscription in the aftermath of Worl ...

. Therefore, Irish tenants viewed the landlord–tenant relationship as inherently illegitimate and sought to abolish it. In the code's early version, practiced by the Whiteboys

The Whiteboys ( ga, na Buachaillí Bána) were a secret Irish agrarian organisation in 18th-century Ireland which defended tenant-farmer land-rights for subsistence farming. Their name derives from the white smocks that members wore in their ...

secret society beginning in the 1760s, it had a reactionary

In political science, a reactionary or a reactionist is a person who holds political views that favor a return to the ''status quo ante'', the previous political state of society, which that person believes possessed positive characteristics abse ...

character which looked back to an era when there had supposedly been a reciprocal relationship between landlords and tenants. Later versions were friendly to capitalism, advocating a market economy

A market economy is an economic system in which the decisions regarding investment, production and distribution to the consumers are guided by the price signals created by the forces of supply and demand, where all suppliers and consumers ...

in land and agricultural products without the "alien" landlord class.

The idea of "unwritten law" was expressed and refined by the Young Ireland

Young Ireland ( ga, Éire Óg, ) was a political movement, political and cultural movement, cultural movement in the 1840s committed to an all-Ireland struggle for independence and democratic reform. Grouped around the Dublin weekly ''The Nati ...

activist James Fintan Lalor

James Fintan Lalor (in Irish, Séamas Fionntán Ó Leathlobhair) (10 March 1809 – 27 December 1849) was an Irish revolutionary, journalist, and “one of the most powerful writers of his day.” A leading member of the Irish Confederation (You ...

(1807–1849), who insisted that the Irish people had allodial title

Allodial title constitutes ownership of real property (land, buildings, and fixtures) that is independent of any superior landlord. Allodial title is related to the concept of land held "in allodium", or land ownership by occupancy and defens ...

to their own land. Lalor believed that a farmer had the first right to his crop for subsistence and seed, and only then could other claims be made on the harvest. Instead of landlords evicting tenants, Lalor preferred that the landlords—"strangers here and strangers everywhere, owning no country and owned by none"—be served with a writ of ejectment

Ejectment is a common law term for civil action to recover the possession of or title to land. It replaced the old real actions and the various possessory assizes (denoting county-based pleas to local sittings of the courts) where boundary disp ...

. Lalor advised the Irish people to refuse "obedience to usurped authority" and resist English law, instead setting up their own government and "refus ngALL rent to the present usurping proprietors". Lalor's writings were the basis of the agrarian code enforced by the Irish National Land League

The Irish National Land League (Irish: ''Conradh na Talún'') was an Irish political organisation of the late 19th century which sought to help poor tenant farmers. Its primary aim was to abolish landlordism in Ireland and enable tenant farmer ...

during the Land War

The Land War ( ga, Cogadh na Talún) was a period of agrarian agitation in rural Ireland (then wholly part of the United Kingdom) that began in 1879. It may refer specifically to the first and most intense period of agitation between 1879 and 18 ...

in the 1880s. The tenets of the unwritten law appeared in "speeches, resolutions, placards, boycotts ... threatening letters and acts of outrage".

Secret societies

The Whiteboys were oath-bound secret societies in rural Ireland since the 1760s. The Threshers originated in

The Whiteboys were oath-bound secret societies in rural Ireland since the 1760s. The Threshers originated in County Mayo

County Mayo (; ga, Contae Mhaigh Eo, meaning "Plain of the Taxus baccata, yew trees") is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. In the West Region, Ireland, West of Ireland, in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Conn ...

early in the nineteenth century and emphasized economic issues; its code regulated prices (including the price of potatoes), and demanded the reduction of the Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the second ...

's tithes

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash or cheques or more r ...

and the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

's fees. Ribbon societies were first organized by poor Catholics during the 1810s. They began in northern Ireland to combat the Protestant Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants, particularly those of Ulster Scots heritage. It also ...

, but later expanded into agrarian agitation and spread southward. The Molly Maguires

The Molly Maguires were an Irish 19th-century secret society active in Ireland, Liverpool and parts of the Eastern United States, best known for their activism among Irish-American and Irish immigrant coal miners in Pennsylvania. After a serie ...

, who appeared in the 1840s, were often confused with Ribbonmen. Whiteboys and Ribbonism became synonymous with agrarian violence in general, and the secret societies which practiced it. The secret societies tended to pop up during agricultural depressions, and vanish in good economic times.

According to American historian Kevin Kenny, the alternative law as understood by the rural poor is the most convincing explanation for the violence practiced by these societies. Rather than a civil war by the Irish against a supposedly alien landlord class, the violence was understood as retributive justice

Retributive justice is a theory of punishment that when an offender breaks the law, justice requires that they suffer in return, and that the response to a crime is proportional to the offence. As opposed to revenge, retribution—and thus retr ...

for violations of traditional landholding and land-use practices. The rural poor could be targets if they broke their oaths to the society or otherwise failed to act in solidarity with the unwritten law. Punishments ranged from digging up new pasture land in an effort to free it up for potato cultivation, tearing down fences on newly- enclosed areas, mutilating or killing livestock, to threats and attacks on landlords' agents and merchants judged to charge exorbitant prices. Murders occurred, but were rare.

Although these societies did not systematically enforce their version of the law via a court system, a person accused of violating the code could be tried by their local society ''in absentia

is Latin for absence. , a legal term, is Latin for "in the absence" or "while absent".

may also refer to:

* Award in absentia

* Declared death in absentia, or simply, death in absentia, legally declared death without a body

* Election in absen ...

''. According to Sir Thomas Larcom

Major-General Sir Thomas Aiskew Larcom, Bart, PC FRS (22 April 1801 – 15 June 1879) was a leading official in the early Irish Ordnance Survey. He later became a poor law commissioner, census commissioner and finally executive head of the B ...

, "There are in fact two codes of law in force and in antagonism—one the statute law enforced by judges and jurors, in which the people do not yet trust—the other a secret law, enforced by themselves—its agents the Ribbonmen and the bullet."

Repeal Association

In July 1843,Daniel O'Connell

Daniel O'Connell (I) ( ga, Dónall Ó Conaill; 6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847), hailed in his time as The Liberator, was the acknowledged political leader of Ireland's Roman Catholic majority in the first half of the 19th century. His mobilizat ...

announced that his mass-membership Repeal Association

The Repeal Association was an Irish mass membership political movement set up by Daniel O'Connell in 1830 to campaign for a repeal of the Acts of Union of 1800 between Great Britain and Ireland.

The Association's aim was to revert Ireland to th ...

(for the repeal of the Acts of Union 1800

The Acts of Union 1800 (sometimes incorrectly referred to as a single 'Act of Union 1801') were parallel acts of the Parliament of Great Britain and the Parliament of Ireland which united the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Irela ...

) would set up a court system as part of its plan to create an Irish government. The courts would be staffed by magistrates who had been dismissed for their pro-Repeal opinions, and supplemented by individuals nominated by Repeal clergy and Repeal Wardens. John Gray, owner of the ''Freeman's Journal

The ''Freeman's Journal'', which was published continuously in Dublin from 1763 to 1924, was in the nineteenth century Ireland's leading nationalist newspaper.

Patriot journal

It was founded in 1763 by Charles Lucas and was identified with radi ...

'', drew up a detailed plan for a national court system based on existing districts; three or more arbiters would adjudicate cases, based on a majority vote. No court fees would be charged, and those who agreed to attend the court would be dismissed from the Repeal Association if they did not obey a verdict. After arbiters were appointed, the courts began to function by the end of October 1843. Their popularity threatened British rule in Ireland; O'Connell was arrested and charged with three counts of conspiracy in connection with the tribunals.

The Repeal Association crumbled after the Great Famine (1845–1849), and the Ribbon Societies assumed its role as arbiters of land and wage disputes. Other arbitration courts were organized by local priests, who denied sacraments

A sacrament is a Christian rite that is recognized as being particularly important and significant. There are various views on the existence and meaning of such rites. Many Christians consider the sacraments to be a visible symbol of the real ...

to those who did not observe a verdict. Contemporary Conservative commentators said that the societies were an alternative justice system; their activities were legal, as long as they did not compel attendance.

Irish Republican Brotherhood

After the unsuccessful 1867Fenian Rising

The Fenian Rising of 1867 ( ga, Éirí Amach na bhFíníní, 1867, ) was a rebellion against British rule in Ireland, organised by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

After the suppression of the ''Irish People'' newspaper in September 1865 ...

, the Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB; ) was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland between 1858 and 1924.McGee, p. 15. Its counterpart in the United States ...

(a physical-force Irish republican group) formed a supreme council. Considering their "Irish Republic" the country's only legitimate authority, they passed a number of constitutions and laws. Violations were punished, and accused traitors were executed.

Land League

TheIrish National Land League

The Irish National Land League (Irish: ''Conradh na Talún'') was an Irish political organisation of the late 19th century which sought to help poor tenant farmers. Its primary aim was to abolish landlordism in Ireland and enable tenant farmer ...

(1879–1882) was a nationally-organized agrarian protest society which sought fair rent, free sale, and fixity of tenure

Free sale, fixity of tenure, and fair rent, also known as the Three Fs, were a set of demands first issued by the Tenant Right League in their campaign for land reform in Ireland from the 1850s. They were,

* Fair rent—meaning rent control: fo ...

for small farmers and, ultimately, peasant ownership of the land they worked. Some of its local branches established arbitration courts in 1880 and 1881. Cases were typically heard by the executive committee, which would summon both parties, call witnesses, examine evidence presented by the parties, make a judgment and assign a penalty for violations of the code. Juries would sometimes be called from local communities, and the plaintiff was occasionally the prosecutor. The courts were modeled on British courts and, according to ''Western News'', the Athenry

Athenry (; ) is a town in County Galway, Ireland, which lies east of Galway city. Some of the attractions of the medieval town are its town wall, Athenry Castle, its priory and its 13th century street-plan. The town is also well known by virtu ...

Land League court docket

Docket may refer to:

*Docket (court), the official schedule of proceedings in lawsuits pending in a court of law.

*Agenda (meeting) or docket, a list of meeting activities in the order in which they are to be taken up

*Receipt or tax invoice, a pr ...

exceeded that of its competing British court. American historian Donald Jordan emphasizes that despite their common-law trappings, the tribunals were essentially an extension of the local Land League branch and adjudicated violations of its own rules. The courts were described as a "shadow legal system" by British academic Frank Ledwidge. According to historian Charles Townshend

Charles Townshend (28 August 1725 – 4 September 1767) was a British politician who held various titles in the Parliament of Great Britain. His establishment of the controversial Townshend Acts is considered one of the key causes of the Ame ...

, the formation of courts was the "most unacceptable of all acts of defiance" committed by the Land League.

One of the League's main tactics was the boycott

A boycott is an act of nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organization, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for moral, social, political, or environmental reasons. The purpose of a boycott is to inflict som ...

, whose most common target was "land grabbers

Land grabbing is the contentious issue of large-scale land acquisitions: the buying or leasing of large pieces of land by domestic and transnational companies, governments, and individuals.

While used broadly throughout history, land grabbing as ...

". However, it did not invent the stratagem of ostracizing those who violated the rural code. Land League speakers (including Michael Davitt

Michael Davitt (25 March 184630 May 1906) was an Irish republican activist for a variety of causes, especially Home Rule and land reform. Following an eviction when he was four years old, Davitt's family migrated to England. He began his caree ...

) advocated that the tactic be used instead of violence on those who seized land which had been worked by evicted tenants. The word "boycott" was coined later that year, after the successful campaign against unpopular land agent Charles Boycott

Charles Cunningham Boycott (12 March 1832 – 19 June 1897) was an English land agent whose ostracism by his local community in Ireland gave the English language the verb "to boycott". He had served in the British Army 39th Foot, which ...

. Although Boycott was forced to leave the country, the boycott's overall effectiveness was disputed and may have been overestimated by contemporary observers. Consequences of the boycott were described by Lord Fitzwilliam

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or are ...

, a pro-landlord advocate, in 1882: "When a man is under the ban of the League no man may speak to him, no one may work for him; he may neither buy nor sell; he is not allowed to go to his ordinary place of worship or to send his children to school." The use of "intimidation" to enforce a boycott was criminalized that year in the Prevention of Crime Act.

In his 1892 book, ''Ireland under the Land League'', Charles Dalton Clifford Lloyd

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was " ...

described how the law's enforcement was difficult because many people refused to cooperate with the official justice system. Refusal to rent transportation equipment to the Royal Irish Constabulary

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC, ga, Constáblacht Ríoga na hÉireann; simply called the Irish Constabulary 1836–67) was the police force in Ireland from 1822 until 1922, when all of the country was part of the United Kingdom. A separate ...

(RIC) paralyzed the police in Kilmallock

Kilmallock () is a town in south County Limerick, Ireland, near the border with County Cork. There is a Dominican Priory in the town and King's Castle (or King John's Castle). The remains of medieval walls which encircled the settlement are sti ...

, and people turned to the Land League rather than magistrates to resolve disputes. If a person observed the official law, they were denounced for breaking the unwritten code. Lloyd complained that instead of petitioning the government for a change in the laws, "the Land League established laws of its own making, formed local committees for the government of districts, instituted into own local tribunals, passed its own judgements, executed its own sentences, and generally usurped the functions of the crown". Lloyd and other observers believed that the League was not just a competing government, but the only effective one in many parts of Ireland; a modern observer noted that "(t)here were areas of the country which simply could not be controlled by the British government." In 1881, Chief Secretary for Ireland William Edward Forster

William Edward Forster, PC, FRS (11 July 18185 April 1886) was an English industrialist, philanthropist and Liberal Party statesman. His supposed advocacy of the Irish Constabulary's use of lethal force against the National Land League earne ...

said that Land League law was ascendant:

Conservative jurist James Fitzjames Stephen

Sir James Fitzjames Stephen, 1st Baronet, KCSI (3 March 1829 – 11 March 1894) was an English lawyer, judge, writer, and philosopher. One of the most famous critics of John Stuart Mill, Stephen achieved prominence as a philosopher, law re ...

wrote that boycotts amounted to "usurpation of the functions of government", and should be considered "the modern representatives of the old conception of high treason". The government passed the Protection of Persons and Property Act 1881

The Protection of Persons and Property (Ireland) Act,The Act had no official short title. It was referred to as ''Protection of Persons and Property (Ireland) Act'', or with ''Person'' in the singular, and/or with ''(Ireland)'' omitted. also call ...

, which provided for the detention without trial of anyone suspected of treasonous activity or who tried to subvert the rule of law, to combat the underground state. Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

had previously refused to suspend ''habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, t ...

'', saying that a Coercion Act

A Coercion Act was an Act of Parliament that gave a legal basis for increased state powers to suppress popular discontent and disorder. The label was applied, especially in Ireland, to acts passed from the 18th to the early 20th century by the Ir ...

would only be justified if Land League agitation threatened not only individuals but the state itself.

National League

TheIrish National League

The Irish National League (INL) was a nationalist political party in Ireland. It was founded on 17 October 1882 by Charles Stewart Parnell as the successor to the Irish National Land League after this was suppressed. Whereas the Land League h ...

(1882–1910) was a more-moderate association which replaced the Land League after the latter was suppressed. The key provisions of the National League's code forbade paying rent without abatements, taking over land from which a tenant had been evicted, and purchasing their holding under the 1885 Ashbourne Act

The Purchase of Land (Ireland) Act 1885 ( 48 & 49 Vict. c.73), commonly known as the Ashbourne Act is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, passed by a Conservative Party government under Lord Salisbury. It extended the terms that had b ...

(except at a low price). Other forbidden activities included "participating in evictions, fraternizing with, or entering into, commerce with anyone who did; or working for, hiring, letting land from, or socializing with, boycotted person". The League enforced its code with informal tribunals, typically led by the leaders of local chapters. The National League's courts held their proceedings openly, and followed a common-law procedure. This was intended to uphold the League's image favouring the rule of law (Irish, rather than English law).

Contemporaries considered the National League a legitimate authority. One Home Rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wit ...

supporter, the Liberal parliamentary candidate Montague Cookson, said that home rule had already arrived: "The decrees of the Government of the Queen are set at naught in the three counties I have mentioned ork, Limerick, Clare while those of the League are instantly and implicitly obeyed." Magistrates and law-enforcement officials agreed with this assessment in their testimony to the Cowper Commission in 1886. According to historian Perry Curtis, the National League was "a self-constituted authority with powers parallel to those of the established government".

United Irish League

TheUnited Irish League

The United Irish League (UIL) was a nationalist political party in Ireland, launched 23 January 1898 with the motto ''"The Land for the People"''. Its objective to be achieved through agrarian agitation and land reform, compelling larger grazi ...

(1898–1910) was an agrarian protest organization based in Connacht

Connacht ( ; ga, Connachta or ), is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the west of Ireland. Until the ninth century it consisted of several independent major Gaelic kingdoms (Uí Fiachrach, Uí Briúin, Uí Maine, Conmhaícne, and Delbhn ...

, with branches throughout the country, which sought redistribution of land from graziers to smallholders and (later) compulsory purchase of land by tenants at favourable prices. After passage of the Land Purchase (Ireland) Act 1903

The Land Acts (officially Land Law (Ireland) Acts) were a series of measures to deal with the question of tenancy contracts and peasant proprietorship of land in Ireland in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Five such acts were introduced by ...

, the League campaigned for the sale of estates (including untenanted land) to tenants at low prices and the reduction of rent to the level of the annuities paid by new freeholders. The ''modus operandi

A ''modus operandi'' (often shortened to M.O.) is someone's habits of working, particularly in the context of business or criminal investigations, but also more generally. It is a Latin phrase, approximately translated as "mode (or manner) of op ...

'' of local UIL branches was to send young men to demand that graziers give up their land. If a compromise could not be reached, the grazier would be summoned to a meeting for his case to be considered. Refusal to attend resulted in the League's highest penalty: the boycott. UIL activists considered that grazing farms violated "unwritten law" because much of the land had been taken from evicted tenants; the fact that many graziers did not live on their holdings made it easier to brand them "land grabbers".

Local UIL branches acted as courts, claiming jurisdiction over all matters relating to land in their area. People accused of violating the League's code would be summoned to a meeting with the plaintiff and the board of the local UIL chapter; evidence would be heard, a verdict reached and punishment imposed. The procedure was very similar to that used by British petty session

Courts of petty session, established from around the 1730s, were local courts consisting of magistrates, held for each petty sessional division (usually based on the county divisions known as hundreds) in England, Wales, and Ireland. The session ...

s. The plaintiff typically acted as prosecutor, following a strict procedural code. Defendants were given sufficient notice to prepare a defence, and were allowed to appeal compensation demanded by plaintiffs. Decisions made by a parish court could be appealed to an executive court. In 56 of 117 cases examined by Irish historian Fergus Campbell, the verdict was to censure the defendant; this typically led to a boycott. The appearance of fairness and impartiality was essential to encourage parties to bring their grievances to UIL courts, and the branches strove to maintain that image. Decisions were published in local nationalist newspapers, allowing UIL leaders to be accountable for their rulings. Campbell found no case in which a UIL court wrongly convicted an innocent man.

Although the "law of the League" was partially derived from the central leadership's guidance and its 1900 constitution, local branches also pressured national leaders to include their own issues. The UIL's priorities shifted from anti-grazier agitation to land purchase. According to the police, their courts' verdicts were enforced by "boycotting, intimidation, and thinly veiled allusions in the Press". Police received reports of 684 boycotts and 1,128 cases of intimidation, about two-thirds of agrarian offences, between 1902 and 1908. Demonstrating the UIL courts' close connection to the concept of "unwritten law", the harshest penalties were reserved for "land-grabbers". After passage of the 1898 Local Government Act

Local Government Act (with its variations) is a stock short title used for legislation in Australia, Malaysia, New Zealand, Ireland and the United Kingdom, relating to local government.

The Bill for an Act with this short title may have been known ...

, which delegated some governmental powers to local elected councils, the UIL competed in local elections. It flew its flag over the court building if it was victorious, although such victories helped legitimize the British justice system.

The courts were central to UIL agitation, because they dictated the targets and manner of agitation. Between October 1899 and October 1900, over 120 cases were heard. The inspector general said in 1907, "The law of the land has been openly set aside and the unwritten law of the League is growing supreme." British historian Philip Bull described the UIL as a "proto-state".

Dáil Courts

The new

The new Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Gri ...

party put arbitration courts into its program after its 1917 Ardfheis

or ''ardfheis'' ( , ; "high assembly"; plural ''ardfheiseanna'') is the name used by many Irish political parties for their annual party conference. The term was first used by Conradh na Gaeilge, the Irish language cultural organisation, for i ...

, and established them throughout the country. According to party leader Arthur Griffith

Arthur Joseph Griffith ( ga, Art Seosamh Ó Gríobhtha; 31 March 1871 – 12 August 1922) was an Irish writer, newspaper editor and politician who founded the political party Sinn Féin. He led the Irish delegation at the negotiations that prod ...

, "It was the duty of every Irishman" to obey the arbitration courts rather than seek justice from British courts. The courts were favoured by Sinn Féin because they adhered to the principle of self-reliance in all matters, and arbitration between two parties in a dispute was legal and binding when the participants agreed to abide by a verdict. Unlike the agrarian-society courts, Sinn Féin's courts claimed jurisdiction over crime and enforced a written constitution.

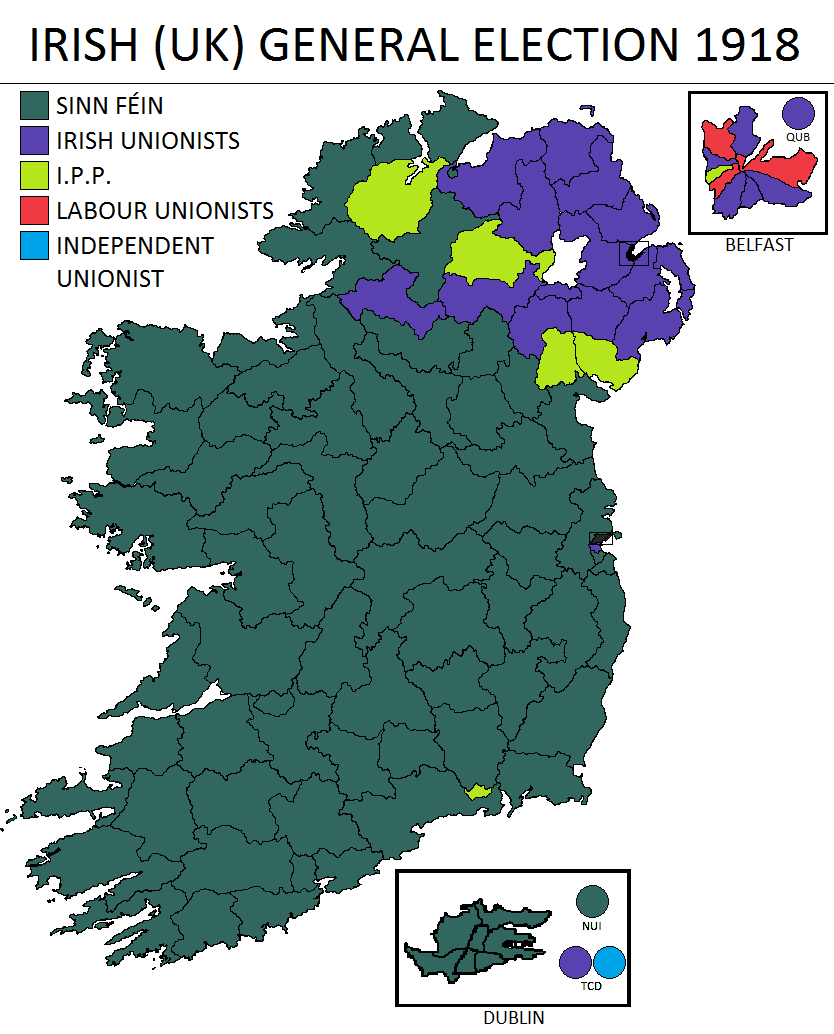

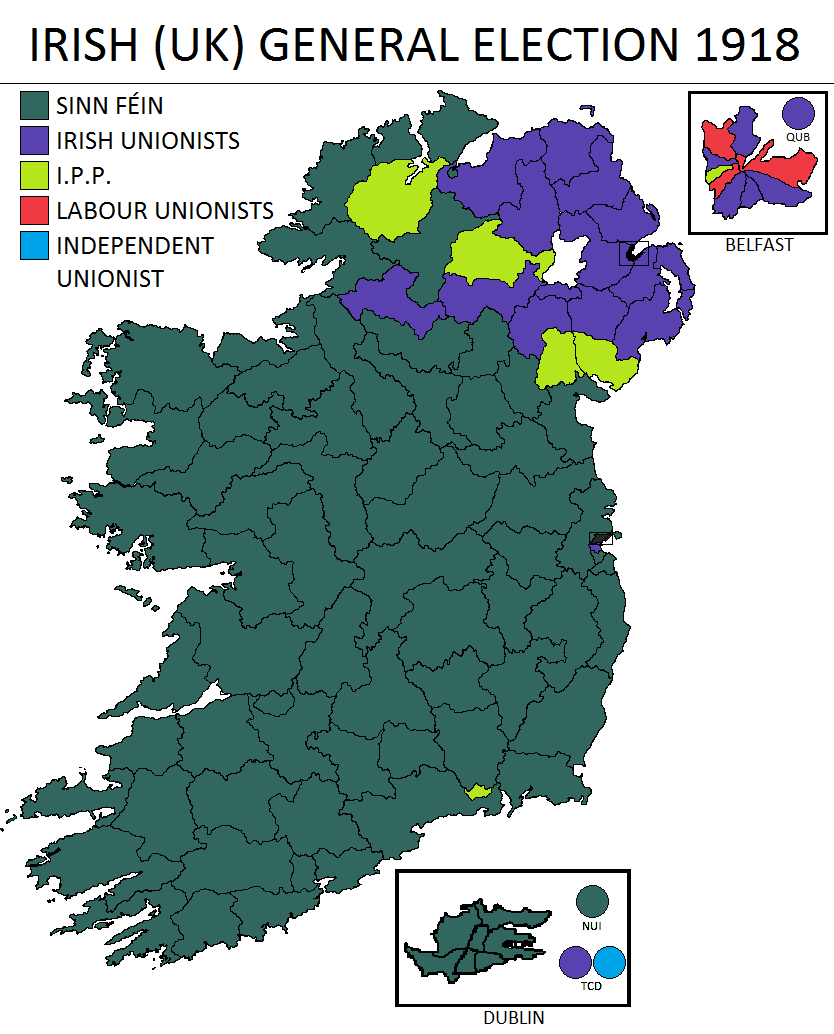

Adhering to the party's policy of abstentionism

Abstentionism is standing for election to a deliberative assembly while refusing to take up any seats won or otherwise participate in the assembly's business. Abstentionism differs from an election boycott in that abstentionists participate in ...

, Sinn Féin MPs who were elected in the 1918 general election refused to take their seats in Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bu ...

and set up the Dáil Éireann

Dáil Éireann ( , ; ) is the lower house, and principal chamber, of the Oireachtas (Irish legislature), which also includes the President of Ireland and Seanad Éireann (the upper house).Article 15.1.2º of the Constitution of Ireland read ...

, a rival parliament. In August 1919, during the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

, the Dáil announced the formation of a national court system for its nascent Irish Republic

The Irish Republic ( ga, Poblacht na hÉireann or ) was an unrecognised revolutionary state that declared its independence from the United Kingdom in January 1919. The Republic claimed jurisdiction over the whole island of Ireland, but by ...

. The system included local parish courts, district courts, and a court of appeal. Parish courts dealt with petty crime and civil cases under £10, providing inexpensive and convenient access to justice. Local judges were elected and all officials received a salary, which cost the state an estimated £113,000. The initial pretense of voluntary arbitration was dropped, and verdicts were enforced by the Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief tha ...

(IRA). The resulting system had a high level of local initiative, with the Dáil exercising very little power. Because the maintenance of British rule had come to rely so heavily on the police and courts to enforce its power, the rest of the Republic's apparatus would have been a "pitiful charade" if the Dáil Courts had not become popular.

Their operation was very similar to the British courts they replaced, and historian Mary Kotsonouris described them as "primarily concerned with the protection of property". The courts had a reputation for fairness, and even unionists respected their role in maintaining order. Known for their "conservative, almost reactionary character", they are "widely considered to be one of the greatest successes of the First Dáil

The First Dáil ( ga, An Chéad Dáil) was Dáil Éireann as it convened from 1919 to 1921. It was the first meeting of the unicameral parliament of the revolutionary Irish Republic. In the December 1918 election to the Parliament of the Unite ...

". According to Irish unionist peer Lord Dunraven,

The Dáil Courts also brought all subversive agrarian courts and IRA courts-martial, which had been operating in some areas after the withdrawal of the Royal Irish Constabulary

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC, ga, Constáblacht Ríoga na hÉireann; simply called the Irish Constabulary 1836–67) was the police force in Ireland from 1822 until 1922, when all of the country was part of the United Kingdom. A separate ...

, under the jurisdiction of the Dáil. The Dáil Courts refused to hear cases dealing with land issues, and in some cases the IRA was called in to remove squatters from private property. By 1921, those who used British courts were accused of "assisting the enemy in time of war". The IRA attacked everyone connected with the British judicial system, and declared that "every person in the pay of England (magistrates and jurors, etc.) will be deemed to have forfeited his life". Intimidation led many JPs to resign, and some RMs were assassinated. The RIC lost control of much of Ireland due to the Irish War of Independence, and rulings from British courts could not be enforced. Suppressed by the British government, the courts continued to operate underground. Their activity peaked during the July–December 1921 truce, when they were busy dealing with ratepayers who failed to pay taxes to the Republic.

As a result of the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty ( ga , An Conradh Angla-Éireannach), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the ...

, the British courts were turned over to the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between th ...

. Count Plunkett

George Noble Plunkett (3 December 1851 – 12 March 1948) was an Irish nationalist politician, museum director and biographer, who served as Minister for Fine Arts from 1921 to 1922, Minister for Foreign Affairs from 1919 to 1921 and Ceann Comha ...

requested a petition of ''habeas corpus'' for the detention without trial of his son, George

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Presiden ...

(an anti-Treaty guerilla), in 1922 after the split between Irish nationalists over the treaty. The judge, Diarmuid Crowley, ordered the younger Plunkett's release; however, Crowley was arrested by the Free State government. The Dáil court system was shut down and declared illegal after this incident, although a commission was appointed to iron out the loose ends in open cases. The courts were officially abolished by the Dáil Éireann Courts (Winding Up) Act 1923.

References

;Citations ;Sources * * * * * From an Oxford Handbooks reprint paginated 1–45, * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{Land War Irish law Agrarian politics Land reform in Ireland Irish nationalism