Allied Landings In North Africa on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – 16 November 1942) was an

Planners identified Oran, Algiers and Casablanca as key targets. Ideally there would also be a landing at Tunis to secure Tunisia and facilitate the rapid interdiction of supplies traveling via Tripoli to

Planners identified Oran, Algiers and Casablanca as key targets. Ideally there would also be a landing at Tunis to secure Tunisia and facilitate the rapid interdiction of supplies traveling via Tripoli to

The Allies organised three amphibious task forces to simultaneously seize the key ports and airports in Morocco and Algeria, targeting

The Allies organised three amphibious task forces to simultaneously seize the key ports and airports in Morocco and Algeria, targeting  The Center Task Force, aimed at Oran, included the U.S. 2nd Battalion 509th Parachute Infantry Regiment, the

The Center Task Force, aimed at Oran, included the U.S. 2nd Battalion 509th Parachute Infantry Regiment, the

At Fedala, a small port with a large beach close to Casablanca, weather disrupted the landings. The landing beaches again came under French fire after daybreak. Patton landed at 08:00, and the beachheads were secured later in the day. The Americans surrounded the port of Casablanca by 10 November, and the city surrendered an hour before the final assault was due to take place. Casablanca was the principal French Atlantic naval base after German occupation of the European coast. The

At Fedala, a small port with a large beach close to Casablanca, weather disrupted the landings. The landing beaches again came under French fire after daybreak. Patton landed at 08:00, and the beachheads were secured later in the day. The Americans surrounded the port of Casablanca by 10 November, and the city surrendered an hour before the final assault was due to take place. Casablanca was the principal French Atlantic naval base after German occupation of the European coast. The

The Center Task Force was split between three beaches, two west of Oran and one east. Landings at the westernmost beach were delayed because of a French convoy which appeared while the minesweepers were clearing a path. Some delay and confusion, and damage to landing ships, was caused by the unexpected shallowness of water and sandbars; although periscope observations had been carried out, no reconnaissance parties had landed on the beaches to determine the local maritime conditions. This helped inform subsequent amphibious assaults—such as

The Center Task Force was split between three beaches, two west of Oran and one east. Landings at the westernmost beach were delayed because of a French convoy which appeared while the minesweepers were clearing a path. Some delay and confusion, and damage to landing ships, was caused by the unexpected shallowness of water and sandbars; although periscope observations had been carried out, no reconnaissance parties had landed on the beaches to determine the local maritime conditions. This helped inform subsequent amphibious assaults—such as

It quickly became clear that Giraud lacked the authority to take command of the French forces. He preferred to wait in Gibraltar for the results of the landing. However, Darlan in Algiers had such authority. Eisenhower, with the support of Roosevelt and Churchill, made an agreement with Darlan, recognizing him as French "High Commissioner" in North Africa. In return, Darlan ordered all French forces in North Africa to cease resistance to the Allies and to cooperate instead. The deal was made on 10 November, and French resistance ceased almost at once. The French troops in North Africa who were not already captured submitted to and eventually joined the Allied forces. Men from French North Africa would see much combat under the Allied banner as part of the

It quickly became clear that Giraud lacked the authority to take command of the French forces. He preferred to wait in Gibraltar for the results of the landing. However, Darlan in Algiers had such authority. Eisenhower, with the support of Roosevelt and Churchill, made an agreement with Darlan, recognizing him as French "High Commissioner" in North Africa. In return, Darlan ordered all French forces in North Africa to cease resistance to the Allies and to cooperate instead. The deal was made on 10 November, and French resistance ceased almost at once. The French troops in North Africa who were not already captured submitted to and eventually joined the Allied forces. Men from French North Africa would see much combat under the Allied banner as part of the

After the German and Italian occupation of Vichy France and their failed attempt to capture the French fleet at Toulon (Operation Lila), the French sided with the Allies, providing a third corps ( XIX Corps) for Anderson. Elsewhere, French warships, such as the battleship , rejoined the Allies.

On 9 November, Axis forces started to build up in French Tunisia, unopposed by the local French forces under General Barré. Wracked with indecision, Barré moved his troops into the hills and formed a defensive line from Teboursouk through

After the German and Italian occupation of Vichy France and their failed attempt to capture the French fleet at Toulon (Operation Lila), the French sided with the Allies, providing a third corps ( XIX Corps) for Anderson. Elsewhere, French warships, such as the battleship , rejoined the Allies.

On 9 November, Axis forces started to build up in French Tunisia, unopposed by the local French forces under General Barré. Wracked with indecision, Barré moved his troops into the hills and formed a defensive line from Teboursouk through  The Eighth Army (Lieutenant-General

The Eighth Army (Lieutenant-General

Vice Admiral

Vice Admiral

US I Armored Corps

US I Armored Corps

Major General

: Northern Attack Group (Mehedia) : Brig. Gen.

US II Corps

Major General Lloyd R. Fredendall, USA

Approx. 39,000 officers and enlisted : 1st Infantry Division (Maj. Gen. Terry Allen) :: 16th Infantry Regiment :: 18th Infantry Regiment ::

Allied Landing Forces

Major General

Approx. 33,000 officers and enlisted : British (approx. 23,000) :: 78th Infantry Division (Maj. Gen.

The Decision to Invade North Africa (TORCH)

part of

'' a publication of the United States Army Center of Military History

Algeria-French Morocco

a book in the ''U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II'' series of the United States Army Center of Military History

A detailed history of 8 November 1942

* [http://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-4621656,00.html (North African Jewish Resistance to Nazis and the Holocaust)]

The accord Franco-Américan of Messelmoun (in French)

Royal Engineers and Second World War (Operation Torch)

* [http://www.historynet.com/magazines/world_war_2/3026106.html Operation Torch: Allied Invasion of North Africa] article by Williamson Murray

Eisenhower's report on operation Torch

Operation TORCH Motion Pictures from the National Archives

Operation Torch

{{DEFAULTSORT:Torch, Operation 1942 in Gibraltar 1942 in Tunisia Algeria in World War II Amphibious operations involving the United Kingdom Amphibious operations involving the United States Amphibious operations of World War II Battles and operations of World War II Battles and operations of World War II involving France Battles and operations of World War II involving the United States Battles of World War II involving Canada Conflicts in 1942 Gibraltar in World War II Invasions by Australia Invasions by Canada Invasions by the Netherlands Invasions by the United States Military battles of Vichy France Military history of Algeria Military history of Canada during World War II Military history of Morocco Morocco in World War II Naval battles and operations of World War II involving the United Kingdom Naval battles of World War II involving Canada Naval battles of World War II involving Germany North African campaign November 1942 events Tunisia in World War II United States Army Rangers World War II invasions Land battles and operations of World War II involving the United Kingdom, Torch Battles and operations of World War II involving the United Kingdom, Torch Military operations of World War II

Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

invasion of French North Africa

French North Africa (french: Afrique du Nord française, sometimes abbreviated to ANF) is the term often applied to the territories controlled by France in the North African Maghreb during the colonial era, namely Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. In ...

during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of securing victory in North Africa while allowing American armed forces the opportunity to engage in the fight against Nazi Germany on a limited scale. It was the first mass involvement of US troops in the European–North African Theatre, and saw the first major airborne assault

Airborne forces, airborne troops, or airborne infantry are ground combat units carried by aircraft and airdropped into battle zones, typically by parachute drop or air assault. Parachute-qualified infantry and support personnel serving in air ...

carried out by the United States.

While the French colonies were formally aligned with Germany via Vichy France

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its ter ...

, the loyalties of the population were mixed. Reports indicated that they might support the Allies. American General Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

, supreme commander of the Allied forces in Mediterranean Theater of Operations

The Mediterranean Theater of Operations, United States Army (MTOUSA), originally called the North African Theater of Operations, United States Army (NATOUSA), was a military formation of the United States Army that supervised all U.S. Army forc ...

, planned a three-pronged attack on Casablanca

Casablanca, also known in Arabic as Dar al-Bayda ( ar, الدَّار الْبَيْضَاء, al-Dār al-Bayḍāʾ, ; ber, ⴹⴹⴰⵕⵍⴱⵉⴹⴰ, ḍḍaṛlbiḍa, : "White House") is the largest city in Morocco and the country's econom ...

(Western), Oran

Oran ( ar, وَهران, Wahrān) is a major coastal city located in the north-west of Algeria. It is considered the second most important city of Algeria after the capital Algiers, due to its population and commercial, industrial, and cultural ...

(Center) and Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques ...

(Eastern), then a rapid move on Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

to catch Axis forces (Afrika Korps

The Afrika Korps or German Africa Corps (, }; DAK) was the German expeditionary force in Africa during the North African Campaign of World War II. First sent as a holding force to shore up the Italian defense of its African colonies, the ...

) in North Africa from the west in conjunction with Allied advance from Egypt.

Operation Torch's Western Task Force encountered unexpected resistance and bad weather, but Casablanca, the principal French Atlantic naval base, was captured after a short siege. The Center Task Force suffered some damage to its ships when trying to land in shallow water but the French ships were sunk or driven off; Oran surrendered after bombardment by British battleships. The French Resistance

The French Resistance (french: La Résistance) was a collection of organisations that fought the German occupation of France during World War II, Nazi occupation of France and the Collaborationism, collaborationist Vichy France, Vichy régim ...

had successfully attempted a coup in Algiers and, even through the late alert raised in the Vichy forces, the Eastern Task Force met less opposition and were able to push inland and compel surrender on the first day.

The success of Torch caused Admiral François Darlan

Jean Louis Xavier François Darlan (7 August 1881 – 24 December 1942) was a French admiral and political figure. Born in Nérac, Darlan graduated from the ''École navale'' in 1902 and quickly advanced through the ranks following his service d ...

, commander of the Vichy French forces, who was in Algiers, to order co-operation with the Allies, in return for being installed as High Commissioner, with many other Vichy officials keeping their jobs. Darlan was assassinated soon afterwards, and the Free French

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exile ...

gradually came to dominate the government.

Background

TheAllies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

planned an Anglo-American invasion of French North Africa/Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ar, الْمَغْرِب, al-Maghrib, lit=the west), also known as the Arab Maghreb ( ar, المغرب العربي) and Northwest Africa, is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, ...

—Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

, Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

and Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

, territory nominally in the hands of the Vichy French

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its terr ...

government. With British forces advancing from Egypt, this would eventually allow the Allies to carry out a pincer operation against Axis forces in North Africa. The Vichy French had around 125,000 soldiers in the territories as well as coastal artillery, 210 operational but out-of-date tanks and about 500 aircraft, half of which were Dewoitine D.520

The Dewoitine D.520 was a French fighter aircraft that entered service in early 1940, shortly after the beginning of the Second World War.

The D.520 was designed in response to a 1936 requirement from the French Air Force for a fast, modern fi ...

fighters—equal to many British and U.S. fighters. These forces included 60,000 troops in Morocco, 15,000 in Tunisia, and 50,000 in Algeria, with coastal artillery, and a small number of tanks and aircraft. In addition, there were 10 or so warships and 11 submarines at Casablanca

Casablanca, also known in Arabic as Dar al-Bayda ( ar, الدَّار الْبَيْضَاء, al-Dār al-Bayḍāʾ, ; ber, ⴹⴹⴰⵕⵍⴱⵉⴹⴰ, ḍḍaṛlbiḍa, : "White House") is the largest city in Morocco and the country's econom ...

.

Political situation on the ground

The Allies believed that the Vichy FrenchArmistice Army

The Armistice Army or Vichy French Army (french: Armée de l'Armistice) was the common name for the armed forces of Vichy France permitted under the Armistice of 22 June 1940 after the French capitulation to Nazi Germany and Italy. It was off ...

would not fight, partly because of information supplied by the American Consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throug ...

Robert Daniel Murphy

Robert Daniel Murphy (October 28, 1894 – January 9, 1978) was an American diplomat. He served as the first United States Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs when the position was established during the Eisenhower administration.

E ...

in Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques ...

. The French were former members of the Allies and the American troops were instructed not to fire unless they were fired upon.

However, they harbored suspicions that the Vichy French Navy would bear a grudge over the actions of the British in June 1940 to prevent French ships being taken by the Germans; the attack on the French Navy in harbour at Mers-el-Kébir, near Oran, killed almost 1,300 French sailors.

An assessment of the sympathies of the French forces in North Africa was essential, and plans were made to secure their cooperation, rather than resistance. German support for the Vichy French came in the shape of air support. Several ''Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

'' bomber wings undertook anti-shipping strikes against Allied ports in Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques ...

and along the North African coast.

Operational command

The operation was originally scheduled to be led by GeneralJoseph Stilwell

Joseph Warren "Vinegar Joe" Stilwell (March 19, 1883 – October 12, 1946) was a United States Army general who served in the China Burma India Theater during World War II. An early American popular hero of the war for leading a column walking ...

, but he was reassigned after the Arcadia Conference The First Washington Conference, also known as the Arcadia Conference (ARCADIA was the code name used for the conference), was held in Washington, D.C., from December 22, 1941, to January 14, 1942. President Roosevelt of the United States and Prime ...

revealed his vitriolic Anglophobia

Anti-English sentiment or Anglophobia (from Latin ''Anglus'' "English" and Greek φόβος, ''phobos'', "fear") means opposition to, dislike of, fear of, hatred of, or the oppression and persecution of England and/or English people.''Oxford ...

and skepticism over the operation. Lt. General Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

was given command of the operation, and he set up his headquarters in Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

. The Allied Naval Commander of the Expeditionary Force was Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham; his deputy was Vice-Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay

Admiral Sir Bertram Home Ramsay, KCB, KBE, MVO (20 January 1883 – 2 January 1945) was a Royal Navy officer. He commanded the destroyer during the First World War. In the Second World War, he was responsible for the Dunkirk evacuation in ...

, who planned the amphibious landings.

Strategic debate among the Allies

Senior U.S. commanders remained strongly opposed to the landings and after the western AlliedCombined Chiefs of Staff

The Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS) was the supreme military staff for the United States and Britain during World War II. It set all the major policy decisions for the two nations, subject to the approvals of British Prime Minister Winston Churchil ...

(CCS) met in London on 30 July 1942, General George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the US Army under Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry ...

and Admiral Ernest King

Ernest Joseph King (23 November 1878 – 25 June 1956) was an American naval officer who served as Commander in Chief, United States Fleet (COMINCH) and Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) during World War II. As COMINCH-CNO, he directed the Un ...

declined to approve the plan. Marshall and other U.S. generals advocated the invasion of northern Europe later that year, which the British rejected. After Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

pressed for a landing in French North Africa in 1942, Marshall suggested instead to President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

that the U.S. abandon the Germany first Europe first, also known as Germany first, was the key element of the grand strategy agreed upon by the United States and the United Kingdom during World War II. According to this policy, the United States and the United Kingdom would use the prepon ...

strategy and take the offensive in the Pacific. Roosevelt said it would do nothing to help the Russians. With Marshall unable to persuade the British to change their minds, President Roosevelt gave a direct order that Torch was to have precedence over other operations and was to take place at the earliest possible date, one of only two direct orders he gave to military commanders during the war.

In conducting their planning, Allied military strategists needed to consider the political situation on the ground in North Africa, which was complex, as well as external diplomatic political aspects. The Americans had recognized Pétain and the Vichy government in 1940, whereas the British did not and had recognized General Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

's French National Committee

The French National Committee (french: Comité national français, CNF) was the coordinating body created by General Charles de Gaulle which acted as the government in exile of Free France from 1941 to 1943. The committee was the successor of ...

as a government-in-exile instead, and agreed to fund them. North Africa was part of France's colonial empire and nominally in support of Vichy, but that support was far from universal among the population.

Political events on the ground contributed to, and in some cases were even primary over, military aspects. The French population in North Africa were divided into three groups:

# Gaullists

Gaullism (french: link=no, Gaullisme) is a French political stance based on the thought and action of World War II French Resistance leader Charles de Gaulle, who would become the founding President of the Fifth French Republic. De Gaulle withd ...

De Gaulle was the rallying point for the French National Committee This comprised French refugees who escaped metropolitan France

Metropolitan France (french: France métropolitaine or ''la Métropole''), also known as European France (french: Territoire européen de la France) is the area of France which is geographically in Europe. This collective name for the European ...

rather than succumb to the German occupation

German-occupied Europe refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly occupied and civil-occupied (including puppet governments) by the military forces and the government of Nazi Germany at various times between 1939 an ...

, or those who stayed and joined the French Resistance

The French Resistance (french: La Résistance) was a collection of organisations that fought the German occupation of France during World War II, Nazi occupation of France and the Collaborationism, collaborationist Vichy France, Vichy régim ...

. One acolyte, General Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque

Philippe François Marie Leclerc de Hauteclocque (22 November 1902 – 28 November 1947) was a Free-French general during the Second World War. He became Marshal of France posthumously in 1952, and is known in France simply as le maréchal ...

, organized a fighting force and conducted raids in 1943 along a path from Lake Chad

Lake Chad (french: Lac Tchad) is a historically large, shallow, endorheic lake in Central Africa, which has varied in size over the centuries. According to the ''Global Resource Information Database'' of the United Nations Environment Programme, ...

to Tripoli and joined with General Bernard Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence and t ...

's British Eighth Army

The Eighth Army was an Allied field army formation of the British Army during the Second World War, fighting in the North African and Italian campaigns. Units came from Australia, British India, Canada, Czechoslovakia, Free French Forces, ...

on 25 January 1943.

# French Liberation Movement some Frenchmen living in North Africa and operating in secret under German surveillance organized an underground "French Liberation Movement", whose aim was to liberate France. General Henri Giraud

Henri Honoré Giraud (18 January 1879 – 11 March 1949) was a French general and a leader of the Free French Forces during the Second World War until he was forced to retire in 1944.

Born to an Alsatian family in Paris, Giraud graduated from ...

, recently escaped from Germany, later became its leader. The personal clash between and Giraud prevented the Free French Forces

__NOTOC__

The French Liberation Army (french: Armée française de la Libération or AFL) was the reunified French Army that arose from the merging of the Armée d'Afrique with the prior Free French Forces (french: Forces françaises libres, l ...

and the French Liberation Movement groups from unifying during the North African campaign (Torch).

# Loyal pro-Vichy French there were those who remained loyal to Marshal Philippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Pétain (24 April 1856 – 23 July 1951), commonly known as Philippe Pétain (, ) or Marshal Pétain (french: Maréchal Pétain), was a French general who attained the position of Marshal of France at the end of World ...

and believed collaboration with the Axis powers was the best method of ensuring the future of France. François Darlan

Jean Louis Xavier François Darlan (7 August 1881 – 24 December 1942) was a French admiral and political figure. Born in Nérac, Darlan graduated from the ''École navale'' in 1902 and quickly advanced through the ranks following his service d ...

was Pétain's designated successor.

American strategy in planning the attack had to take into account these complexities on the ground. The planners assumed that if the leaders were given Allied military support they would take steps to liberate themselves, and the U.S. embarked on detailed negotiations under American Consul General Robert Murphy in Rabat

Rabat (, also , ; ar, الرِّبَاط, er-Ribât; ber, ⵕⵕⴱⴰⵟ, ṛṛbaṭ) is the capital city of Morocco and the country's seventh largest city with an urban population of approximately 580,000 (2014) and a metropolitan populati ...

with the French Liberation Movement. Since Britain was already diplomatically and financially committed to , it was clear that negotiations with the French Liberation Movement would have to be conducted by the Americans, and the invasion as well. Because of divided loyalties among the groups on the ground their support was uncertain, and due to the need to maintain secrecy, detailed plans could not be shared with the French.

Allied plans

Planners identified Oran, Algiers and Casablanca as key targets. Ideally there would also be a landing at Tunis to secure Tunisia and facilitate the rapid interdiction of supplies traveling via Tripoli to

Planners identified Oran, Algiers and Casablanca as key targets. Ideally there would also be a landing at Tunis to secure Tunisia and facilitate the rapid interdiction of supplies traveling via Tripoli to Erwin Rommel

Johannes Erwin Eugen Rommel () (15 November 1891 – 14 October 1944) was a German field marshal during World War II. Popularly known as the Desert Fox (, ), he served in the ''Wehrmacht'' (armed forces) of Nazi Germany, as well as servi ...

's Afrika Korps

The Afrika Korps or German Africa Corps (, }; DAK) was the German expeditionary force in Africa during the North African Campaign of World War II. First sent as a holding force to shore up the Italian defense of its African colonies, the ...

forces in Italian Libya

Libya ( it, Libia; ar, ليبيا, Lībyā al-Īṭālīya) was a colony of the Fascist Italy located in North Africa, in what is now modern Libya, between 1934 and 1943. It was formed from the unification of the colonies of Italian Cyrenaica ...

. However, Tunis was much too close to the Axis airfields in Sicily and Sardinia for any hope of success. A compromise would be to land at Bône

Annaba ( ar, عنّابة, "Place of the Jujubes"; ber, Aânavaen), formerly known as Bon, Bona and Bône, is a seaport city in the northeastern corner of Algeria, close to the border with Tunisia. Annaba is near the small Seybouse River ...

in eastern Algeria, some closer to Tunis than Algiers. Limited resources dictated that the Allies could only make three landings and Eisenhower—who believed that any plan must include landings at Oran and Algiers—had two main options: either the western option, to land at Casablanca, Oran and Algiers and then make as rapid a move as possible to Tunis some east of Algiers once the Vichy opposition was suppressed; or the eastern option, to land at Oran, Algiers and Bône and then advance overland to Casablanca some west of Oran. He favored the eastern option because of the advantages it gave to an early capture of Tunis and also because the Atlantic swells off Casablanca presented considerably greater risks to an amphibious landing there than would be encountered in the Mediterranean.

The Combined Chiefs of Staff, however, were concerned that should Operation Torch precipitate Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

to abandon neutrality and join the Axis, the Straits of Gibraltar could be closed cutting the entire Allied force's lines of communication. They therefore chose the Casablanca option as the less risky since the forces in Algeria and Tunisia could be supplied overland from Casablanca (albeit with considerable difficulty) in the event of closure of the straits.

Marshall's opposition to Torch delayed the landings by almost a month, and his opposition to landings in Algeria led British military leaders to question his strategic ability; the Royal Navy controlled the Strait of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar ( ar, مضيق جبل طارق, Maḍīq Jabal Ṭāriq; es, Estrecho de Gibraltar, Archaic: Pillars of Hercules), also known as the Straits of Gibraltar, is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Medi ...

, and Spain was unlikely to intervene as Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War ...

was hedging his bets. The Morocco landings ruled out the early occupation of Tunisia. Marshall did convince the Allies to abandon the planned invasions of Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

and Tangier

Tangier ( ; ; ar, طنجة, Ṭanja) is a city in northwestern Morocco. It is on the Moroccan coast at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Spartel. The town is the cap ...

in preparation for the landings, which he maintained would lose the element of surprise and draw large Spanish military contingents in Spanish Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

and the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to the African mainland, they are west of Morocc ...

into the war. However, Harry Hopkins

Harry Lloyd Hopkins (August 17, 1890 – January 29, 1946) was an American statesman, public administrator, and presidential advisor. A trusted deputy to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Hopkins directed New Deal relief programs before servi ...

convinced President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

to agree to the general plan. Eisenhower told Patton that ''the past six weeks were the most trying of his life''. In Eisenhower's acceptance of landings in Algeria and Morocco, he pointed out that the decision removed the early capture of Tunis from the probable to only the remotely possible because of the extra time it would afford the Axis to move forces into Tunisia.

Intelligence gathering

In July 1941, Mieczysław Słowikowski (using the codename "''Rygor''"—Polish for "Rigor") set up " Agency Africa", one of the Second World War's most successful intelligence organizations. His Polish allies in these endeavors included Lt. Col.Gwido Langer

Lt. Col. Karol Gwido Langer (Žilina, Zsolna, Austria-Hungary, 2 September 1894 – 30 March 1948, Kinross, Scotland) was, from at least mid-1931, chief of the Polish General Staff's Biuro Szyfrów, Cipher Bureau, which from December 1932 decr ...

and Major Maksymilian Ciężki

Maksymilian Ciężki (; Samter, Province of Posen (now Szamotuły, Poland), 24 November 1898 – 9 November 1951 in London, England) was the head of the Polish Cipher Bureau's German section (''BS–4'') in the 1930s, during which time— ...

. The information gathered by the Agency was used by the Americans and British in planning the amphibious November 1942 Operation Torch landings in North Africa.

Preliminary contact with Vichy French

To gauge the feeling of the Vichy French forces, Murphy was appointed to the American consulate in Algeria. His covert mission was to determine the mood of the French forces and to make contact with elements that might support an Allied invasion. He succeeded in contacting several French officers, includingGeneral

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

Charles Mast

Emmanuel Charles Mast (7 January 1889 – 30 September 1977) was a major general who participated in the liberation of North Africa in 1942 and was Resident General of France in Tunisia between 1943 and 1947.

Prewar

He was the son of Miche ...

, the French commander-in-chief in Algiers.

These officers were willing to support the Allies but asked for a clandestine conference with a senior Allied General in Algeria. Major General Mark W. Clark

Mark Wayne Clark (May 1, 1896 – April 17, 1984) was a United States Army officer who saw service during World War I, World War II, and the Korean War. He was the youngest four-star general in the US Army during World War II.

During World War I ...

—one of Eisenhower's senior commanders—was dispatched to Cherchell

Cherchell (Arabic: شرشال) is a town on Algeria's Mediterranean coast, west of Algiers. It is the seat of Cherchell District in Tipaza Province. Under the names Iol and Caesarea, it was formerly a Roman colony and the capital of the k ...

in Algeria aboard the British submarine and met with these Vichy French officers on 21 October 1942.

With help from the Resistance, the Allies also succeeded in slipping French General Henri Giraud

Henri Honoré Giraud (18 January 1879 – 11 March 1949) was a French general and a leader of the Free French Forces during the Second World War until he was forced to retire in 1944.

Born to an Alsatian family in Paris, Giraud graduated from ...

out of Vichy France on HMS ''Seraph''—passing itself off as an American submarine—to Gibraltar, where Eisenhower had his headquarters, intending to offer him the post of commander in chief of French forces in North Africa after the invasion. However, Giraud would take no position lower than commander in chief of all the invading forces, a job already given to Eisenhower. When he was refused, he decided to remain "a spectator in this affair".

Battle

The Allies organised three amphibious task forces to simultaneously seize the key ports and airports in Morocco and Algeria, targeting

The Allies organised three amphibious task forces to simultaneously seize the key ports and airports in Morocco and Algeria, targeting Casablanca

Casablanca, also known in Arabic as Dar al-Bayda ( ar, الدَّار الْبَيْضَاء, al-Dār al-Bayḍāʾ, ; ber, ⴹⴹⴰⵕⵍⴱⵉⴹⴰ, ḍḍaṛlbiḍa, : "White House") is the largest city in Morocco and the country's econom ...

, Oran

Oran ( ar, وَهران, Wahrān) is a major coastal city located in the north-west of Algeria. It is considered the second most important city of Algeria after the capital Algiers, due to its population and commercial, industrial, and cultural ...

and Algiers. Successful completion of these operations was to be followed by an eastwards advance into Tunisia.

A Western Task Force (aimed at Casablanca) was composed of American units, with Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

George S. Patton

George Smith Patton Jr. (November 11, 1885 – December 21, 1945) was a general in the United States Army who commanded the Seventh United States Army in the Mediterranean Theater of World War II, and the Third United States Army in France ...

in command and Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

Henry Kent Hewitt

Henry Kent Hewitt (February 11, 1887 – September 15, 1972) was the United States Navy commander of amphibious operations in north Africa and southern Europe through World War II. He was born in Hackensack, New Jersey and graduated from the Unit ...

heading the naval operations. This Western Task Force consisted of the U.S. 3rd

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* Second#Sexagesimal divisions of calendar time and day, 1⁄60 of a ''second'', or 1⁄3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (d ...

and 9th Infantry Divisions, and two battalions from the U.S. 2nd Armored Division—35,000 troops in a convoy of over 100 ships. They were transported directly from the United States in the first of a new series of UG convoys

The UG convoys were a series of east-bound trans-Atlantic convoys from the United States to Gibraltar carrying food, ammunition, and military hardware to the United States Army in North Africa and southern Europe during World War II. These con ...

providing logistic support for the North African campaign.

The Center Task Force, aimed at Oran, included the U.S. 2nd Battalion 509th Parachute Infantry Regiment, the

The Center Task Force, aimed at Oran, included the U.S. 2nd Battalion 509th Parachute Infantry Regiment, the U.S. 1st Infantry Division

The 1st Infantry Division is a combined arms division of the United States Army, and is the oldest continuously serving division in the Regular Army. It has seen continuous service since its organization in 1917 during World War I. It was offi ...

, and the U.S. 1st Armored Division

The 1st Armored Division, nicknamed "Old Ironsides," is a combined arms division of the United States Army. The division is part of III Armored Corps and operates out of Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas. It was the first armored division of the ...

—a total of 18,500 troops. They sailed from the United Kingdom and were commanded by Major General Lloyd Fredendall

Lieutenant General Lloyd Ralston Fredendall (December 28, 1883 – October 4, 1963) was a senior officer of the United States Army who served during World War II. He is best known for his leadership failure during the Battle of Kasserine Pass, le ...

, the naval forces being commanded by Commodore Thomas Troubridge.

Torch was, for propaganda purposes, a landing by U.S. forces, supported by British warships and aircraft, under the belief that this would be more palatable to French public opinion, than an Anglo-American invasion. For the same reason, Churchill suggested that British soldiers might wear U.S. Army uniforms, and No.6 Commando did so. (Fleet Air Arm

The Fleet Air Arm (FAA) is one of the five fighting arms of the Royal Navy and is responsible for the delivery of naval air power both from land and at sea. The Fleet Air Arm operates the F-35 Lightning II for maritime strike, the AW159 Wil ...

aircraft did carry US "star" roundels during the operation, and two British destroyers flew the Stars and Stripes.) In reality, the Eastern Task Force—aimed at Algiers—was commanded by Lieutenant-General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

Kenneth Anderson and consisted of a brigade from the British 78th and the U.S. 34th Infantry Divisions, along with two British commando units ( No. 1 and No. 6 Commandos), together with the RAF Regiment providing 5 squadrons of infantry and 5 Light anti-aircraft flights, totalling 20,000 troops. During the landing phase, ground forces were to be commanded by U.S. Major General Charles W. Ryder

Major General Charles Wolcott Ryder CB (January 16, 1892 – August 17, 1960) was a senior United States Army officer who served with distinction in both World War I and World War II.

Early life and military career

Born in Topeka, Kansas in m ...

, Commanding General

The commanding officer (CO) or sometimes, if the incumbent is a general officer, commanding general (CG), is the officer in command of a military unit. The commanding officer has ultimate authority over the unit, and is usually given wide latitu ...

(CG) of the 34th Division and naval forces were commanded by Royal Navy Vice-Admiral Sir Harold Burrough.

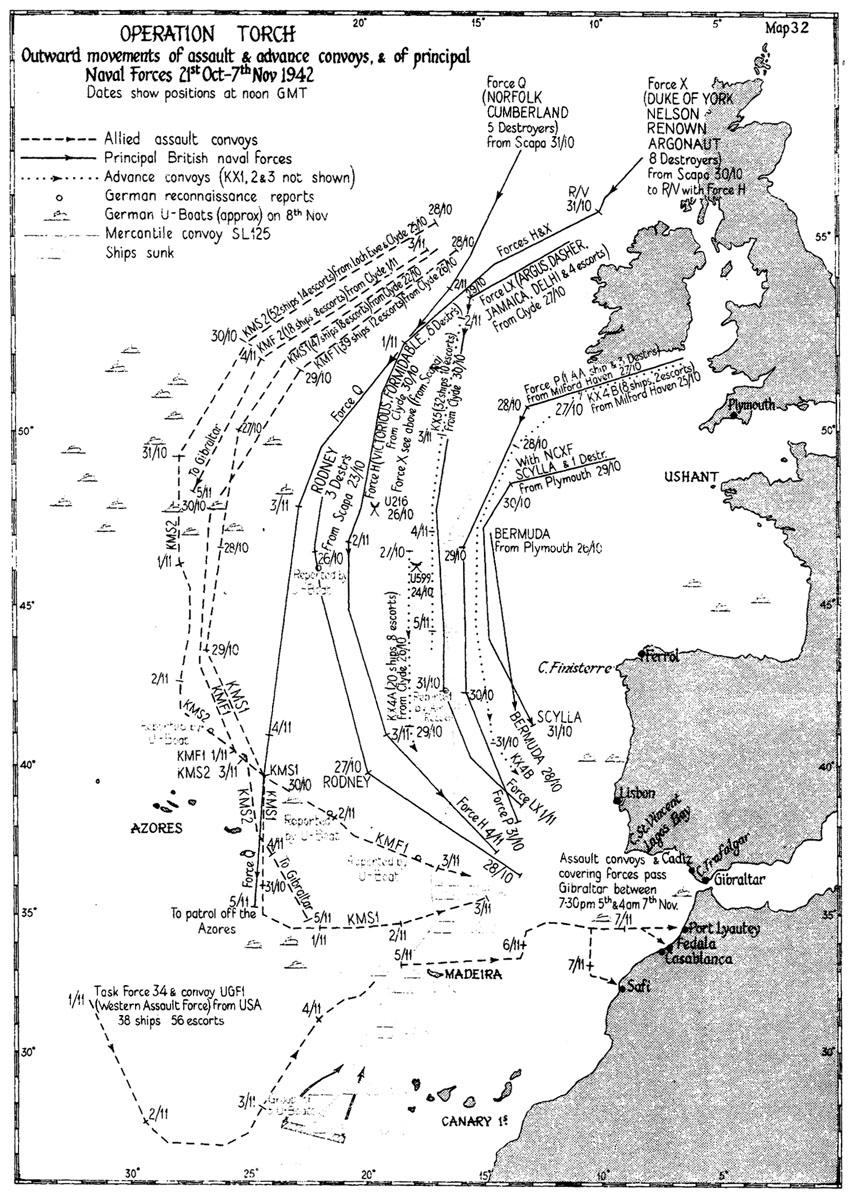

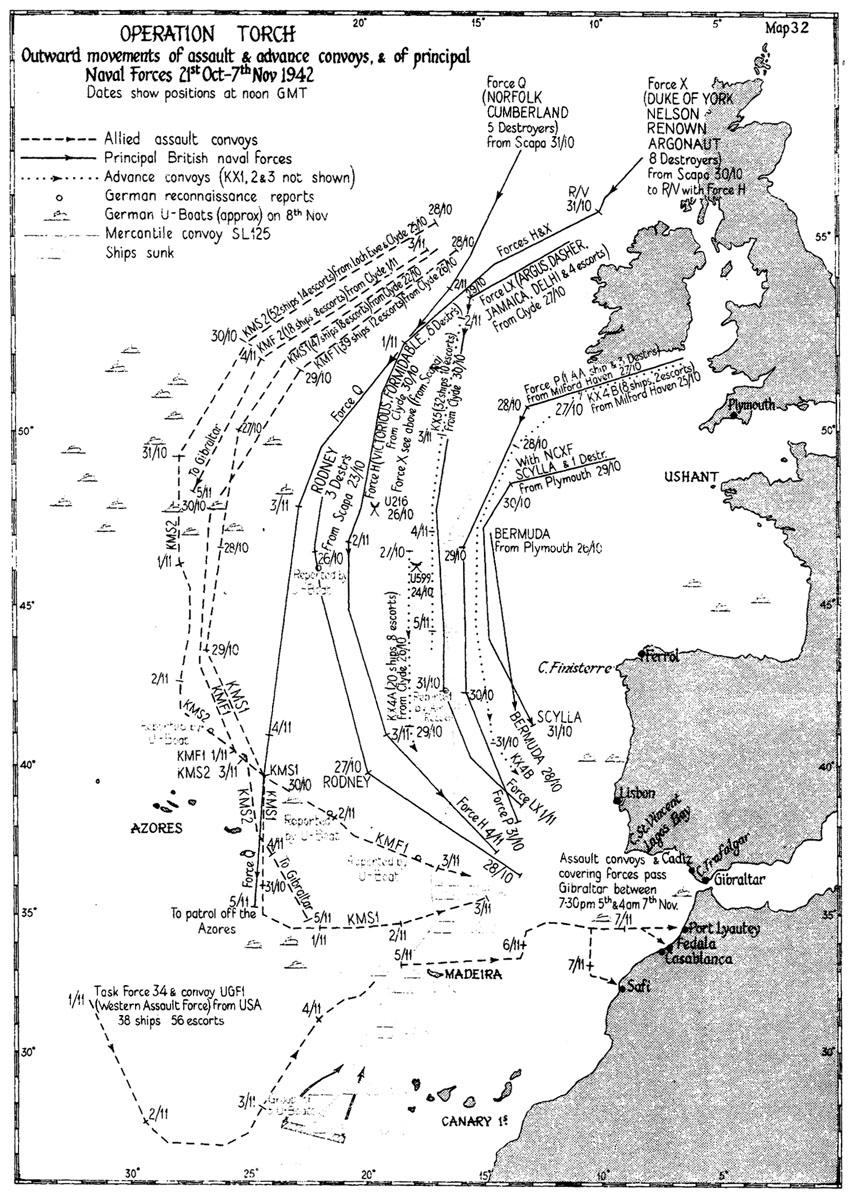

U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

s, operating in the eastern Atlantic area crossed by the invasion convoys, had been drawn away to attack trade convoy SL 125.

Aerial operations were split into two commands, with Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

aircraft under Air Marshal Sir William Welsh operating east of Cape Tenez in Algeria, and all United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

aircraft under Major General Jimmy Doolittle

James Harold Doolittle (December 14, 1896 – September 27, 1993) was an American military general and aviation pioneer who received the Medal of Honor for his daring raid on Japan during World War II. He also made early coast-to-coast flights ...

, who was under the direct command of Major General Patton, operating west of Cape Tenez. P-40s of the 33rd Fighter Group were launched from U.S. Navy escort carriers and landed at Port Lyautey

Kenitra ( ar, القُنَيْطَرَة, , , ; ber, ⵇⵏⵉⵟⵔⴰ, Qniṭra; french: Kénitra) is a city in north western Morocco, formerly known as Port Lyautey from 1932 to 1956. It is a port on the Sebou river, has a population in 201 ...

on 10 November. Additional air support was provided by the carrier , whose squadrons intercepted Vichy aircraft and bombed hostile ships.

Casablanca

The Western Task Force landed before daybreak on 8 November 1942, at three points in Morocco: Safi (Operation Blackstone

Operation Blackstone was a part of Operation Torch, the Allied landings in North Africa during World War II. The operation called for American amphibious troops to land at and capture the French-held port of Safi in French Morocco. The landings ...

), Fedala

Mohammedia ( ar, المحمدية, al-muḥammadiyya; ber, ⴼⴹⴰⵍⴰ, Fḍala), known until 1960 as Fedala, is a port city on the west coast of Morocco between Casablanca and Rabat in the region of Casablanca-Settat. It hosts the most impo ...

( Operation Brushwood, the largest landing with 19,000 men), and Mehdiya-Port Lyautey

Kenitra ( ar, القُنَيْطَرَة, , , ; ber, ⵇⵏⵉⵟⵔⴰ, Qniṭra; french: Kénitra) is a city in north western Morocco, formerly known as Port Lyautey from 1932 to 1956. It is a port on the Sebou river, has a population in 201 ...

( Operation Goalpost). Because it was hoped that the French would not resist, there were no preliminary bombardments. This proved to be a costly error as French defenses took a toll on American landing forces. On the night of 7 November, pro-Allied General Antoine Béthouart

Marie Émile Antoine Béthouart (17 December 1889 – 17 October 1982) was a French Army general who served during World War I and World War II.

Born in Dole, Jura, in the Jura Mountains, Béthouart graduated from Saint-Cyr military academy a ...

attempted a '' coup d'etat'' against the French command in Morocco, so that he could surrender to the Allies the next day. His forces surrounded the villa of General Charles Noguès

Charles Noguès (13 August 1876 – 20 April 1971) was a French general. He graduated from the École Polytechnique, and he was awarded the Grand Croix of the Legion of Honour in 1939.

Biography

On 20 March 1933, he became commander of the 1 ...

, the Vichy-loyal high commissioner. However, Noguès telephoned loyal forces, who stopped the coup. In addition, the coup attempt alerted Noguès to the impending Allied invasion, and he immediately bolstered French coastal defenses.

At Fedala, a small port with a large beach close to Casablanca, weather disrupted the landings. The landing beaches again came under French fire after daybreak. Patton landed at 08:00, and the beachheads were secured later in the day. The Americans surrounded the port of Casablanca by 10 November, and the city surrendered an hour before the final assault was due to take place. Casablanca was the principal French Atlantic naval base after German occupation of the European coast. The

At Fedala, a small port with a large beach close to Casablanca, weather disrupted the landings. The landing beaches again came under French fire after daybreak. Patton landed at 08:00, and the beachheads were secured later in the day. The Americans surrounded the port of Casablanca by 10 November, and the city surrendered an hour before the final assault was due to take place. Casablanca was the principal French Atlantic naval base after German occupation of the European coast. The Naval Battle of Casablanca

The Naval Battle of Casablanca was a series of naval engagements fought between United States Navy, American ships covering the Operation Torch, invasion of North Africa and Vichy France, Vichy French ships defending the Neutrality (international ...

resulted from a sortie of French cruisers, destroyers, and submarines opposing the landings. A cruiser, six destroyers, and six submarines were destroyed by American gunfire and aircraft. The incomplete French battleship —which was docked and immobile—fired on the landing force with her one working gun turret until disabled by the 16-inch calibre American naval gunfire of USS ''Massachusetts'', the first such heavy-calibre shells fired by the U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage of ...

anywhere in World War II. Many of her one ton shells didn't explode, linked to poor detonators, and aircraft bombers sank the Jean Bart. Two U.S. destroyers were damaged.

At Safi, the objective being capturing the port facilities to land the Western Task Force's medium tanks, the landings were mostly successful. The landings were begun without covering fire, in the hope that the French would not resist at all. However, once French coastal batteries opened fire, Allied warships returned fire. By the time the 3rd Battalion, 67th Armored Regiment

The 67th Armored Regiment is an armored regiment in the United States Army. The regiment was first formed in 1929 in the Regular Army as the 2nd Tank Regiment (Heavy) and redesignated as the 67th Infantry Regiment (Medium Tanks) in 1932. It fi ...

arrived, French snipers had pinned the assault troops (most of whom were in combat for the first time) on Safi's beaches. Most of the landings occurred behind schedule. Carrier aircraft destroyed a French truck convoy bringing reinforcements to the beach defenses. Safi surrendered on the afternoon of 8 November. By 10 November, the remaining defenders were pinned down, and the bulk of Harmon's forces raced to join the siege of Casablanca.

At Port-Lyautey, the landing troops were uncertain of their position, and the second wave was delayed. This gave the French defenders time to organize resistance, and the remaining landings were conducted under artillery bombardment. A former French pilot of the port onboard a US destroyer led her up the shallow river to take over the artillery battery, clearing the way to the air-base. With the assistance of carrier air support, the troops pushed ahead, and the objectives were captured.

Oran

The Center Task Force was split between three beaches, two west of Oran and one east. Landings at the westernmost beach were delayed because of a French convoy which appeared while the minesweepers were clearing a path. Some delay and confusion, and damage to landing ships, was caused by the unexpected shallowness of water and sandbars; although periscope observations had been carried out, no reconnaissance parties had landed on the beaches to determine the local maritime conditions. This helped inform subsequent amphibious assaults—such as

The Center Task Force was split between three beaches, two west of Oran and one east. Landings at the westernmost beach were delayed because of a French convoy which appeared while the minesweepers were clearing a path. Some delay and confusion, and damage to landing ships, was caused by the unexpected shallowness of water and sandbars; although periscope observations had been carried out, no reconnaissance parties had landed on the beaches to determine the local maritime conditions. This helped inform subsequent amphibious assaults—such as Operation Overlord

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allies of World War II, Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Front (World War II), Western Europe during World War II. The operat ...

—in which considerable weight was given to pre-invasion reconnaissance.

The U.S. 1st Ranger Battalion landed east of Oran and quickly captured the shore battery at Arzew

Arzew or Arzeu ( ar, أرزيو Berber; ) is a port city in Algeria, 25 miles (40 km) from Oran. It is the capital of Arzew District, Oran Province.

History

Antiquity

Like the rest of North Africa, the site of modern-day Arzew was orig ...

. An attempt was made to land U.S. infantry at the harbour directly, in order to quickly prevent destruction of the port facilities and scuttling of ships. Operation Reservist

Operation Reservist was an Allied military operation during the Second World War. Part of Operation Torch (the Allied invasion of North Africa), it was an attempted landing of troops directly into the harbour at Oran in Algeria.

Background

The ...

failed, as the two sloops

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular sa ...

were destroyed by crossfire from the French vessels there. The Vichy French naval fleet broke from the harbor and attacked the Allied invasion fleet but its ships were all sunk or driven ashore. The commander of Reservist, Captain Frederick Thornton Peters, was awarded the Victoria Cross for valour in pushing the attack through Oran harbour in the face of point blank fire. French batteries and the invasion fleet exchanged fire throughout 8–9 November, with French troops defending Oran and the surrounding area stubbornly; bombardment by the British battleships brought about Oran's surrender on 10 November.

Airborne landings

Torch was the first major airborne assault carried out by the United States. The 2nd Battalion, 509th Parachute Infantry Regiment, aboard 39C-47 Dakotas

The Douglas C-47 Skytrain or Dakota (RAF, RAAF, RCAF, RNZAF, and SAAF designation) is a military transport aircraft developed from the civilian Douglas DC-3 airliner. It was used extensively by the Allies during World War II and remained in ...

, flew all the way from Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

in England, over Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, to drop near Oran and capture airfields at Tafraoui

Tafraoui is a municipality in Oran Province, Algeria close to the city of Oran. There is an airport with the same name. Capturing Tafaraoui Airport was a part of Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – 16 November 1942) was ...

and La Sénia

La Sénia is a municipality in the ''comarca'' of Montsià in

Catalonia, Spain.

This town is located in a plain by the Sénia River at the western end of the Montsià county. The limestone massif of the Ports de Tortosa-Beseit rises a few mile ...

, respectively and south of Oran. The operation was marked by communicational and navigational problems owing to the anti-aircraft and beacon ship HMS ''Alynbank'' broadcasting on the wrong frequency. Poor weather over Spain and the extreme range caused the formation to scatter and forced 30 of the 37 air transports to land in the dry salt lake to the west of the objective. Of the other aircraft, one pilot became disoriented and landed his plane in Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

. Two others landed in French Morocco

The French protectorate in Morocco (french: Protectorat français au Maroc; ar, الحماية الفرنسية في المغرب), also known as French Morocco, was the period of French colonial rule in Morocco between 1912 to 1956. The prote ...

and three in Spanish Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

, where another Dakota dropped its paratroopers by mistake. A total of 67 American troops were interned by Franco

Franco may refer to:

Name

* Franco (name)

* Francisco Franco (1892–1975), Spanish general and dictator of Spain from 1939 to 1975

* Franco Luambo (1938–1989), Congolese musician, the "Grand Maître"

Prefix

* Franco, a prefix used when ref ...

's forces until February 1943. Tafraoui and La Sénia were eventually captured but the role played by the airborne forces in Operation Torch was minimal.

Algiers

Resistance and coup

As agreed at Cherchell, in the early hours of 8 November, the 400 mainly Jewish French Resistance fighters of theGéo Gras Group The Géo Gras Group was a French resistance movement that played a decisive role during Operation Torch, the British-American invasion of French North Africa during WWII.

Formed October 1940 in Algiers, the group recruited Jews and French Army offic ...

staged a coup in the city of Algiers. Starting at midnight, the force under the command of Henri d'Astier de la Vigerie Henri d'Astier de La Vigerie (11 September 1897 – 10 October 1952) was a French soldier, ''Résistance'' member, and conservative politician.

Life

Henri d'Astier was born in Villedieu-sur-Indre, a small village in the Indre département of cent ...

and José Aboulker

José Aboulker (5 March 1920 – 17 November 2009) was a French Algerian Jew and the leader of the anti-Nazi resistance in French Algeria in World War II. He received the U.S. Medal of Freedom, the Croix de Guerre, and was made a Compani ...

seized key targets, including the telephone exchange, radio station, governor's house and the headquarters of the 19th Corps.

Robert Murphy took some men and then drove to the residence of General Alphonse Juin

Alphonse Pierre Juin (16 December 1888 – 27 January 1967) was a senior French Army Army general (France), general who became Marshal of France. A graduate of the École Spéciale Militaire de Saint-Cyr, École Spéciale Militaire class of 1912, ...

, the senior French Army officer in North Africa. While they surrounded his house (making Juin a hostage) Murphy attempted to persuade him to side with the Allies. Juin was treated to a surprise: Admiral François Darlan

Jean Louis Xavier François Darlan (7 August 1881 – 24 December 1942) was a French admiral and political figure. Born in Nérac, Darlan graduated from the ''École navale'' in 1902 and quickly advanced through the ranks following his service d ...

—the commander of all French forces—was also in Algiers on a private visit. Juin insisted on contacting Darlan and Murphy was unable to persuade either to side with the Allies. In the early morning, the local Gendarmerie

Wrong info! -->

A gendarmerie () is a military force with law enforcement duties among the civilian population. The term ''gendarme'' () is derived from the medieval French expression ', which translates to " men-at-arms" (literally, ...

arrived and released Juin and Darlan.

Invasion

On 8 November 1942, the invasion commenced with landings on three beaches—two west of Algiers and one east. The landing forces were under the overall command of Major-GeneralCharles W. Ryder

Major General Charles Wolcott Ryder CB (January 16, 1892 – August 17, 1960) was a senior United States Army officer who served with distinction in both World War I and World War II.

Early life and military career

Born in Topeka, Kansas in m ...

, commanding general of the U.S. 34th Infantry Division. The 11th Brigade Group from the British 78th Infantry Division landed on the right hand beach; the US 168th Regimental Combat Team, from the 34th Infantry Division, supported by 6 Commando and most of 1 Commando, landed on the middle beach; and the US 39th Regimental Combat Team, from the US 9th Infantry Division, supported by the remaining 5 troops from 1 Commando, landed on the left hand beach. The 36th Brigade Group from the British 78th Infantry Division stood by in floating reserve. Though some landings went to the wrong beaches, this was immaterial because of the lack of French opposition. All the coastal batteries had been neutralized by the French Resistance and one French commander defected to the Allies. The only fighting took place in the port of Algiers, where in Operation Terminal

Operation Terminal was an Allied operation during World War II. Part of Operation Torch (the Allied invasion of French North Africa, 8 November 1942) it involved a direct landing of infantry into the Vichy French port of Algiers with the intention ...

, two British destroyers attempted to land a party of US Army Rangers directly onto the dock, to prevent the French destroying the port facilities and scuttling their ships. Heavy artillery fire prevented one destroyer from landing but the other was able to disembark before it too was driven back to sea. The US troops pushed quickly inland and General Juin surrendered the city to the Allies at 18:00.

Aftermath

Political results

It quickly became clear that Giraud lacked the authority to take command of the French forces. He preferred to wait in Gibraltar for the results of the landing. However, Darlan in Algiers had such authority. Eisenhower, with the support of Roosevelt and Churchill, made an agreement with Darlan, recognizing him as French "High Commissioner" in North Africa. In return, Darlan ordered all French forces in North Africa to cease resistance to the Allies and to cooperate instead. The deal was made on 10 November, and French resistance ceased almost at once. The French troops in North Africa who were not already captured submitted to and eventually joined the Allied forces. Men from French North Africa would see much combat under the Allied banner as part of the

It quickly became clear that Giraud lacked the authority to take command of the French forces. He preferred to wait in Gibraltar for the results of the landing. However, Darlan in Algiers had such authority. Eisenhower, with the support of Roosevelt and Churchill, made an agreement with Darlan, recognizing him as French "High Commissioner" in North Africa. In return, Darlan ordered all French forces in North Africa to cease resistance to the Allies and to cooperate instead. The deal was made on 10 November, and French resistance ceased almost at once. The French troops in North Africa who were not already captured submitted to and eventually joined the Allied forces. Men from French North Africa would see much combat under the Allied banner as part of the French Expeditionary Corps There have been several French Expeditionary Corps (French ''Corps expéditionnaire'' 'français'':

* Expeditionary Corps of the Orient 'Corps expéditionnaire d'Orient'', CEO(1915), during World War I

* Expeditionary Corps of the Dardanelles 'Co ...

(consisting of 112,000 troops in April 1944) in the Italian campaign, where Maghrebis (mostly Moroccans) made up over 60% of the unit's soldiers.

When Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

learned of Darlan's deal with the Allies, he immediately ordered the occupation of Vichy France and sent Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previous ...

troops to Tunisia.

The American press protested, immediately dubbing it the "Darlan Deal", pointing out that Roosevelt had made a brazen bargain with Hitler's puppets in France. If a main goal of Torch had originally been the liberation of North Africa, hours later that had been jettisoned in favor of safe passage through North Africa. Giraud ended up taking over the post when Darlan was assassinated six weeks later.

The Eisenhower/Darlan agreement meant that the officials appointed by the Vichy regime would remain in power in North Africa. No role was provided for Free France

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exile ...

, which was supposed to be France's government-in-exile and had taken charge in other French colonies. That deeply offended Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

, the head of Free France. It also offended much of the British and American public, who regarded all Vichy French as Nazi collaborators and Darlan as one of the worst. Eisenhower insisted, however, that he had no real choice if his forces were to move on against the Axis in Tunisia, rather than fight the French in Algeria and Morocco.

Though de Gaulle had no official power in Vichy North Africa, much of its population now publicly declared Free French allegiance, putting pressure on Darlan. On 24 December, Fernand Bonnier de La Chapelle

Fernand Bonnier de La Chapelle (4 November 1922 – 26 December 1942) was a royalist member of the French resistance during World War II. He assassinated Admiral of the Fleet François Darlan, the former chief of government of Vichy France and the ...

, a French resistance fighter and anti-fascist monarchist, assassinated Darlan. (Bonnier de La Chapelle was arrested on the spot and executed two days later.)

Giraud succeeded Darlan but, like him, replaced few of the Vichy officials. He even ordered the arrest of the leaders of the Algiers coup of 8 November, with no opposition from Murphy.

The French North African government gradually became active in the Allied war effort. The limited French troops in Tunisia did not resist German troops arriving by air; Admiral Esteva, the commander, obeyed orders to that effect from Vichy. The Germans took the airfields there and brought in more troops. The French troops withdrew to the west and, within a few days, began to skirmish against the Germans, encouraged by small American and British detachments who had reached the area. While that was of minimal military effect, it committed the French to the Allied side. Later, all French forces were withdrawn from action and properly reequipped by the Allies.

Giraud supported that but also preferred to maintain the old Vichy administration in North Africa. Under pressure from the Allies and de Gaulle's supporters, the French régime shifted, with Vichy officials gradually replaced and its more offensive decrees rescinded. In June 1943, Giraud and de Gaulle agreed to form the French Committee of National Liberation

The French Committee of National Liberation (french: Comité français de Libération nationale) was a provisional government of Free France formed by the French generals Henri Giraud and Charles de Gaulle to provide united leadership, organiz ...

(CFLN), with members from both the North African government and from de Gaulle's French National Committee

The French National Committee (french: Comité national français, CNF) was the coordinating body created by General Charles de Gaulle which acted as the government in exile of Free France from 1941 to 1943. The committee was the successor of ...

. In November 1943, de Gaulle became head of the CFLN and ''de jure'' head of government of France and was recognized by the U.S. and Britain.

In another political outcome of Torch (and at Darlan's orders), the previously-Vichyite government of French West Africa

French West Africa (french: Afrique-Occidentale française, ) was a federation of eight French colonial territories in West Africa: Mauritania, Senegal, French Sudan (now Mali), French Guinea (now Guinea), Ivory Coast, Upper Volta (now Burki ...

joined the Allies.

Military consequences

Toulon

One of the terms of theSecond Armistice at Compiègne

The Armistice of 22 June 1940 was signed at 18:36 near Compiègne, France, by officials of Nazi Germany and the Third French Republic. It did not come into effect until after midnight on 25 June.

Signatories for Germany included Wilhelm Keitel, ...

agreed to by the Germans was that the "zone libre

The ''zone libre'' (, ''free zone'') was a partition of the French metropolitan territory during World War II, established at the Second Armistice at Compiègne on 22 June 1940. It lay to the south of the demarcation line and was administered by ...

" of southern France

Southern France, also known as the South of France or colloquially in French language, French as , is a defined geographical area consisting of the regions of France that border the Atlantic Ocean south of the Marais Poitevin,Louis Papy, ''Le midi ...

would remain free of German occupation and governed by Vichy. The lack of determined resistance by the Vichy French to the Allied invasions of North Africa and the new policies of de Gaulle in North Africa convinced the Germans that France could not be trusted. Moreover, the Anglo-American presence in French North Africa invalidated the only real rationale for not occupying the whole of France since it was the only practical means to deny the Allies use of the French colonies. The Germans and the Italians immediately occupied southern France, and the German Army

The German Army (, "army") is the land component of the armed forces of Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German ''Bundeswehr'' together with the ''Marine'' (German Navy) and the ''Luftwaf ...

moved to seize the French fleet in the port of Toulon from 10 November. The naval strength of the Axis in the Mediterranean would have been greatly increased if the Germans had succeeded in seizing the French ships, but every important ship was scuttled at dock by the French Navy before the Germans could take them.

Tunisia

After the German and Italian occupation of Vichy France and their failed attempt to capture the French fleet at Toulon (Operation Lila), the French sided with the Allies, providing a third corps ( XIX Corps) for Anderson. Elsewhere, French warships, such as the battleship , rejoined the Allies.

On 9 November, Axis forces started to build up in French Tunisia, unopposed by the local French forces under General Barré. Wracked with indecision, Barré moved his troops into the hills and formed a defensive line from Teboursouk through

After the German and Italian occupation of Vichy France and their failed attempt to capture the French fleet at Toulon (Operation Lila), the French sided with the Allies, providing a third corps ( XIX Corps) for Anderson. Elsewhere, French warships, such as the battleship , rejoined the Allies.

On 9 November, Axis forces started to build up in French Tunisia, unopposed by the local French forces under General Barré. Wracked with indecision, Barré moved his troops into the hills and formed a defensive line from Teboursouk through Medjez el Bab

Majaz al Bab ( ar, مجاز الباب), also known as Medjez el Bab, or as Membressa under the Roman Empire, is a town in northern Tunisia. It is located at the intersection of roads GP5 and GP6, in the ''Plaine de la Medjerda''.

Commonwealth wa ...

and ordered that anyone trying to pass through the line would be shot. On 19 November, the German commander, Walter Nehring

Walther Nehring (15 August 1892 – 20 April 1983) was a German general in the Wehrmacht during World War II who commanded the Afrika Korps.

Early life

Nehring was born on 15 August 1892 in Stretzin, West Prussia. Nehring was the descendant of a ...

, demanded passage for his troops across the bridge at Medjez and was refused. The Germans attacked the poorly-equipped French units twice and were driven back. The French had suffered many casualties and lacking artillery and armour, Barré was forced to withdraw.

After consolidating in Algeria, the Allies began the Tunisia Campaign

The Tunisian campaign (also known as the Battle of Tunisia) was a series of battles that took place in Tunisia during the North African campaign of the World War II, Second World War, between Axis powers, Axis and Allies of World War II, Allied ...

. Elements of the First Army (Lieutenant-General Kenneth Anderson), came to within of Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

before a counterattack

A counterattack is a tactic employed in response to an attack, with the term originating in "war games". The general objective is to negate or thwart the advantage gained by the enemy during attack, while the specific objectives typically seek ...

at Djedeida

Djedeida is a town and commune in the Manouba Governorate, Tunisia. It is about 25 km west of Tunis. As of 2021 it had a population of 45,000.Erwin Rommel

Johannes Erwin Eugen Rommel () (15 November 1891 – 14 October 1944) was a German field marshal during World War II. Popularly known as the Desert Fox (, ), he served in the ''Wehrmacht'' (armed forces) of Nazi Germany, as well as servi ...

, retreating westward from Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya bo ...

, reached Tunisia.

The Eighth Army (Lieutenant-General

The Eighth Army (Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence and t ...

) advancing from the east, stopped around Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis may refer to:

Cities and other geographic units Greece

*Tripoli, Greece, the capital of Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in ...