All Saints' Church, Shuart on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

All Saints' Church, Shuart (), in the north-west of the

All Saints' Church, Shuart (), in the north-west of the

The place-name "Shuart" is from the

The place-name "Shuart" is from the

Thomas Elmham's map of the Isle of Thanet, drawn in the early 15th century, shows the church with its tower, but a map of 1596 by Philip Symonson, which shows churches "as they actually appeared", shows a church without a tower. Examination of the church's foundations indicates that it was probably a ruin by the middle of the 15th century and was demolished, but was replaced by a smaller structure, without a tower, up to 20 years later. It may be that material from All Saints' Church was used in the construction of a new clerestory for the nave of St Nicholas' church in the late 15th century, and the medieval baptismal font now in Reculver's parish church of St Mary the Virgin at Hillborough probably came from All Saints'. By 1630 there was no church: in that year, the vicar and

Thomas Elmham's map of the Isle of Thanet, drawn in the early 15th century, shows the church with its tower, but a map of 1596 by Philip Symonson, which shows churches "as they actually appeared", shows a church without a tower. Examination of the church's foundations indicates that it was probably a ruin by the middle of the 15th century and was demolished, but was replaced by a smaller structure, without a tower, up to 20 years later. It may be that material from All Saints' Church was used in the construction of a new clerestory for the nave of St Nicholas' church in the late 15th century, and the medieval baptismal font now in Reculver's parish church of St Mary the Virgin at Hillborough probably came from All Saints'. By 1630 there was no church: in that year, the vicar and

All Saints' Church, Shuart (), in the north-west of the

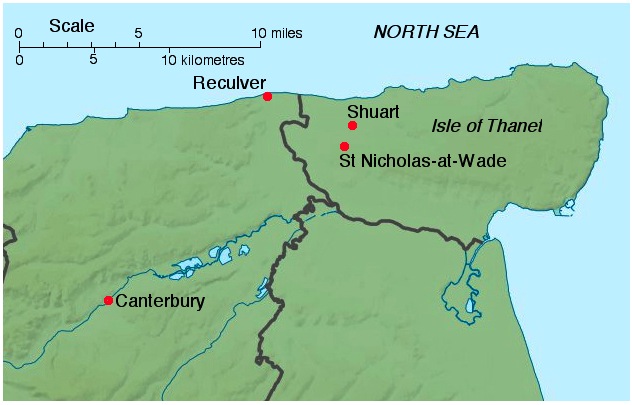

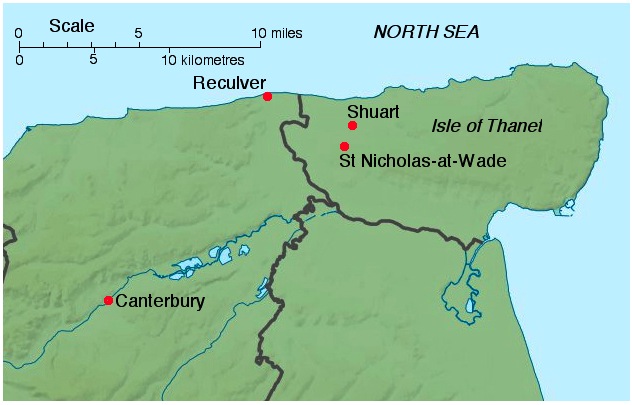

All Saints' Church, Shuart (), in the north-west of the Isle of Thanet

The Isle of Thanet () is a peninsula forming the easternmost part of Kent, England. While in the past it was separated from the mainland by the Wantsum Channel, it is no longer an island.

Archaeological remains testify to its settlement in anc ...

, Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

, in the south-east of England, was established in the Anglo-Saxon period

Anglo-Saxon England or Early Medieval England, existing from the 5th to the 11th centuries from the end of Roman Britain until the Norman conquest in 1066, consisted of various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms until 927, when it was united as the Kingdom of ...

as a chapel of ease

A chapel of ease (or chapel-of-ease) is a church architecture, church building other than the parish church, built within the bounds of a parish for the attendance of those who cannot reach the parish church conveniently.

Often a chapel of ea ...

for the parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one or m ...

of St Mary's Church, Reculver

St Mary's Church, Reculver, was founded in the 7th century as either a minster or a monastery on the site of a Roman fort at Reculver, which was then at the north-eastern extremity of Kent in south-eastern England. In 669, the site of the for ...

, which was centred on the north-eastern corner of mainland Kent, adjacent to the island. The Isle of Thanet was then separated from the mainland by the sea, which formed a strait

A strait is an oceanic landform connecting two seas or two other large areas of water. The surface water generally flows at the same elevation on both sides and through the strait in either direction. Most commonly, it is a narrow ocean channe ...

known as the Wantsum Channel

The Wantsum Channel was a strait separating the Isle of Thanet from the north-eastern extremity of the English county of Kent and connecting the English Channel and the Thames Estuary. It was a major shipping route when Britain was part of the Rom ...

. The last church on the site was demolished by the early 17th century, and there is nothing remaining above ground to show that a church once stood there.

The area of the Isle of Thanet where All Saints' Church stood had been settled since the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

, and land in the west of the Isle of Thanet was given to the church at Reculver in the 7th century. All Saints' Church remained a chapel of ease for the parish of Reculver until the early 14th century, when the parish was broken up to form separate parishes for Herne and St Nicholas-at-Wade

St Nicholas-at-Wade (or St Nicholas) is both a village and a civil parish in the Thanet District of Kent, England. The parish had a recorded population of 782 at the 2001 Census, increasing to 852 at the 2011 census. The village of Sarre is part ...

. The area served by All Saints' was merged with that of St Nicholas-at-Wade, which became the centre of a new parish with All Saints' as its chapel. The churches of All Saints and St Nicholas continued to have a junior relationship with the parish of Reculver, making annual payments to the church there.

All Saints' originally consisted of a nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

and chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may terminate in an apse.

Ove ...

, to which a sanctuary

A sanctuary, in its original meaning, is a sacred place, such as a shrine. By the use of such places as a haven, by extension the term has come to be used for any place of safety. This secondary use can be categorized into human sanctuary, a sa ...

was added in the first building phase. The church was extended on three occasions between the 10th and 14th centuries – a period of population growth – to include an aisle

An aisle is, in general, a space for walking with rows of non-walking spaces on both sides. Aisles with seating on both sides can be seen in airplanes, certain types of buildings, such as churches, cathedrals, synagogues, meeting halls, parl ...

d nave, a western tower and a northern chapel; its windows featured stained glass

Stained glass is coloured glass as a material or works created from it. Throughout its thousand-year history, the term has been applied almost exclusively to the windows of churches and other significant religious buildings. Although tradition ...

. The church was abandoned in the 15th century, presumably because the parish could no longer support two churches. It was demolished, and virtually all of its masonry removed, some of which may have been used in improvements to the church of St Nicholas. The settlement of Shuart remained as an area of local administration into the 17th century, but it is now regarded as a deserted medieval village. There were no visible remains of All Saints' Church by 1723, although land there remained as glebe

Glebe (; also known as church furlong, rectory manor or parson's close(s))McGurk 1970, p. 17 is an area of land within an ecclesiastical parish used to support a parish priest. The land may be owned by the church, or its profits may be reserved ...

belonging to the parish of St Nicholas. The site of All Saints' Church was excavated by archaeologists

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

between 1978 and 1979. The main structure had been robbed of its materials leaving only the foundations, from which the archaeologists were able to interpret the history of the building's construction and its form. Among the foundations were discovered numerous stone carvings, floor tile

Tiles are usually thin, square or rectangular coverings manufactured from hard-wearing material such as ceramic, stone, metal, baked clay, or even glass. They are generally fixed in place in an array to cover roofs, floors, walls, edges, or o ...

s, remnants of stained glass, and several disturbed graves.

Origin

The place-name "Shuart" is from the

The place-name "Shuart" is from the Anglo-Saxon language

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th cen ...

and means a skirted, or cut-off, piece of land. The earliest evidence of human settlement at Shuart dates to the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

; a rectangular Bronze Age enclosure lies a little to the north of the site of All Saints' Church, and a collection of objects from that period, known as the "Shuart Hoard", was found south-west of the site in the 1980s. Occupation continued through the Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

and the Roman period. Structures, pottery and glass dating to these times have been found nearby, as well as human burials and cremations.

The site's history in the Anglo-Saxon period

Anglo-Saxon England or Early Medieval England, existing from the 5th to the 11th centuries from the end of Roman Britain until the Norman conquest in 1066, consisted of various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms until 927, when it was united as the Kingdom of ...

begins with the division of the Isle of Thanet

The Isle of Thanet () is a peninsula forming the easternmost part of Kent, England. While in the past it was separated from the mainland by the Wantsum Channel, it is no longer an island.

Archaeological remains testify to its settlement in anc ...

into eastern and western parts during the 7th century. The division is attributed in medieval sources to the route taken by a tame female deer that was set free to run across the island by Æbbe, founder and first abbess

An abbess (Latin: ''abbatissa''), also known as a mother superior, is the female superior of a community of Catholic nuns in an abbey.

Description

In the Catholic Church (both the Latin Church and Eastern Catholic), Eastern Orthodox, Coptic ...

of the double monastery

A double monastery (also dual monastery or double house) is a monastery combining separate communities of monks and of nuns, joined in one institution to share one church and other facilities. The practice is believed to have started in the East ...

at Minster-in-Thanet

Minster, also known as Minster-in-Thanet, is a village and civil parish in the Thanet District of Kent, England. It is the site of Minster in Thanet Priory. The village is west of Ramsgate (which is the post town) and to the north east of Cant ...

, thereby marking out its endowment. The route was circuitous, beginning on the north side of the island at Westgate-on-Sea

Westgate-on-Sea is a seaside town and civil parish on the north-east coast of Kent, England. It is within the Thanet local government district and borders the larger seaside resort of Margate. Its two sandy beaches have remained a popular touri ...

and ending on the south side at Sheriff's Court, halfway between Minster-in-Thanet and Monkton, which are about apart. While land to the east of this route was given to Æbbe for her monastery, which was in existence by 678, land to the west, described broadly as ''Westanea'', or "the western part of the island", was given to the monastery at Reculver by King Hlothhere of Kent

Hlothhere ( ang, Hloþhere; died 6 February 685) was a King of Kent who ruled from 673 to 685.

Hlothhere succeeded his brother Ecgberht I in 673. His parents were Eorcenberht of Kent and Seaxburh of Ely, the daughter of Anna of East Anglia. I ...

in 679. This division of the island is apparent in Domesday Book

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manusc ...

, which was compiled in 1086, and remained an important feature in the early 15th century, when it was included prominently in a map of the island drawn up by Thomas Elmham

Thomas Elmham (1364in or after 1427) was an English chronicler.

Life

Thomas Elmham was probably born at North Elmham in Norfolk. He may have been the Thomas Elmham who was a scholar at King's Hall, Cambridge from 1389 to 1394. He became a Bened ...

. According to Edward Hasted

Edward Hasted (20 December 1732 OS (31 December 1732 NS) – 14 January 1812) was an English antiquarian and pioneering historian of his ancestral home county of Kent. As such, he was the author of a major county history, ''The History and T ...

the division was still marked in 1800 by "a bank, or lynch, which goes quite across the island, and is commonly called St. Mildred's lynch."

The monastery at Reculver had been established in 669, and developed as the centre of a "large estate, a manor and a parish". By the early 9th century it had become "extremely wealthy", but it then came under the control of the archbishops of Canterbury. By the 10th century the church and its estate appear to have fallen into royal hands, since King Eadred

Eadred (c. 923 – 23 November 955) was King of the English from 26 May 946 until his death. He was the younger son of Edward the Elder and his third wife Eadgifu, and a grandson of Alfred the Great. His elder brother, Edmund, was killed try ...

of England gave them in 949 to Christ Church, Canterbury, now known as Canterbury Cathedral

Canterbury Cathedral in Canterbury, Kent, is one of the oldest and most famous Christian structures in England. It forms part of a World Heritage Site. It is the cathedral of the Archbishop of Canterbury, currently Justin Welby, leader of the ...

. The Anglo-Saxon charter recording the gift shows that the Reculver estate still included land in the west of the Isle of Thanet at that time. Two slightly earlier charters give a more complicated picture: in 943, King Edmund I

Edmund I or Eadmund I (920/921 – 26 May 946) was King of the English from 27 October 939 until his death in 946. He was the elder son of King Edward the Elder and his third wife, Queen Eadgifu, and a grandson of King Alfred the Great. After ...

of England gave land at St Nicholas-at-Wade

St Nicholas-at-Wade (or St Nicholas) is both a village and a civil parish in the Thanet District of Kent, England. The parish had a recorded population of 782 at the 2001 Census, increasing to 852 at the 2011 census. The village of Sarre is part ...

to a layman, and in the next year he gave the same layman land at Monkton, by means of a charter recording that land to the west and north of Monkton – evidently at Sarre – was nonetheless still regarded as belonging to Reculver, rather than to either the archbishop or the king. However, while Edmund I's mother Eadgifu The name Eadgifu, sometimes Latinized as ''Ediva'' or ''Edgiva'', may refer to:

* Eadgifu of Kent (died c. 966), third wife of king Edward the Elder, King of Wessex

* Eadgifu of Wessex (902 – after 955), wife of King Charles the Simple

* Eadgifu, ...

gave lands in Kent, including Monkton, to Christ Church in 961, all of the documents recording these transactions entered the Christ Church archive; and, if the land that Christ Church acquired on the Isle of Thanet in the 10th century was the same as the "Liberty" shown on Thomas Elmham's map from the early 15th century, then the site of All Saints' Church, Shuart, must have been included. Neither Shuart nor St Nicholas-at-Wade are mentioned by name in Domesday Book; but they may have been included in the entry for Reculver, which was then recorded as a hundred

100 or one hundred (Roman numeral: C) is the natural number following 99 and preceding 101.

In medieval contexts, it may be described as the short hundred or five score in order to differentiate the English and Germanic use of "hundred" to de ...

in its own right, and was held entirely by the archbishop of Canterbury, but for a portion held from him by a tenant. An analysis of the archbishop's holdings in Domesday Book concludes that All Saints' was among them.

Church and community

A church dedicated to All Saints was established at Shuart some time between 679 and the 10th century. Although the status of the church at Reculver asmother church

Mother church or matrice is a term depicting the Christian Church as a mother in her functions of nourishing and protecting the believer. It may also refer to the primary church of a Christian denomination or diocese, i.e. a cathedral or a metro ...

for the area dates from the 7th century, and may have led to the establishment of a church at Shuart then, this chapel might equally have been a development in response to acquisition of land in the area by Christ Church, Canterbury, in the mid-900s. Examination of the building's archaeological remains has failed to provide a more precise date, but a church stood at Shuart for about 100 years or more before the establishment of a nearby church at St Nicholas-at-Wade, since the earliest church there was "almost certainly built in the late 11th century".

First church

The original church of All Saints was a rectangular building aligned on an east-west axis, measuring by . It consisted of a westernnave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

and an eastern chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may terminate in an apse.

Ove ...

, with a sanctuary

A sanctuary, in its original meaning, is a sacred place, such as a shrine. By the use of such places as a haven, by extension the term has come to be used for any place of safety. This secondary use can be categorized into human sanctuary, a sa ...

added to the eastern end of the chancel in the first phase of building. The chancel was about long, and the nave was small, taking up only about of the building's overall length. They were connected by a recessed passageway about long but only about across at its narrowest, the foundations for which suggest a heavy structure, perhaps including a vaulted

In architecture, a vault (French ''voûte'', from Italian ''volta'') is a self-supporting arched form, usually of stone or brick, serving to cover a space with a ceiling or roof. As in building an arch, a temporary support is needed while ring ...

ceiling. The size of the community this church was originally built to serve is unknown, although Domesday Book records the presence of 90 villeins

A villein, otherwise known as ''cottar'' or '' crofter'', is a serf tied to the land in the feudal system. Villeins had more rights and social status than those in slavery, but were under a number of legal restrictions which differentiated them ...

and 25 bordars

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

in the manor of Reculver in 1086, which included land on the Isle of Thanet, but consisted mainly of land in mainland Kent. Those numbers can be multiplied four or five times to account for dependants, since they only represent adult male heads of households; Domesday Book does not say where in the manor they lived.

Expansion

A second phase of building was undertaken between the 10th and 11th centuries, in which the church was enlarged. The west wall was demolished, allowing the nave to be extended to the west by , and the passageway between it and the chancel was opened out and replaced with a lighter chancel arch. A third phase followed in the 12th century, when the nave was rebuilt as a much larger structure with north and southaisle

An aisle is, in general, a space for walking with rows of non-walking spaces on both sides. Aisles with seating on both sides can be seen in airplanes, certain types of buildings, such as churches, cathedrals, synagogues, meeting halls, parl ...

s, each lined by four columns, and measuring about wide by long. A tower about square was added to the western end of the church either at this time or in a fourth phase of building carried out in the 13th century. This fourth phase involved the installation of new windows featuring stained glass

Stained glass is coloured glass as a material or works created from it. Throughout its thousand-year history, the term has been applied almost exclusively to the windows of churches and other significant religious buildings. Although tradition ...

, especially at the eastern end of the nave, comparable to the ''grisaille

Grisaille ( or ; french: grisaille, lit=greyed , from ''gris'' 'grey') is a painting executed entirely in shades of grey or of another neutral greyish colour. It is particularly used in large decorative schemes in imitation of sculpture. Many g ...

'' glass still in the south transept

A transept (with two semitransepts) is a transverse part of any building, which lies across the main body of the building. In cruciform churches, a transept is an area set crosswise to the nave in a cruciform ("cross-shaped") building wi ...

of York Minster

The Cathedral and Metropolitical Church of Saint Peter in York, commonly known as York Minster, is the cathedral of York, North Yorkshire, England, and is one of the largest of its kind in Northern Europe. The minster is the seat of the Arch ...

that dates from about 1240. A chapel was also added to the north side of the church, measuring about wide by long, with an altar

An altar is a table or platform for the presentation of religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. Altars are found at shrines, temples, churches, and other places of worship. They are used particularly in paga ...

at its eastern end, and paved with tiles about square. Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

floor tiles were also installed in the church, probably in the 15th century.

The expansion of the church coincided with a period of growth in the population of Reculver parish as a whole, which had expanded to more than 3,000 people by the late 13th century. The first record to mention All Saints' explicitly dates from 1284, when the community it served complained to the archbishop of Canterbury that the vicar

A vicar (; Latin: ''vicarius'') is a representative, deputy or substitute; anyone acting "in the person of" or agent for a superior (compare "vicarious" in the sense of "at second hand"). Linguistically, ''vicar'' is cognate with the English pref ...

of Reculver had failed to provide a chaplain

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a Minister (Christianity), minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a laity, lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secularity, secular institution (such as a hosp ...

to celebrate daily mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different elementar ...

. In 1296 the archbishop settled a dispute concerning a duty to pay for repairs to the church, specifying that this was owed by owners of property on and around part of "North Street". In 1310 Archbishop Robert Winchelsey

Robert Winchelsey (or Winchelsea; c. 1245 – 11 May 1313) was an English Catholic theologian and Archbishop of Canterbury. He studied at the universities of Paris and Oxford, and later taught at both. Influenced by Thomas Aquinas, he was a s ...

of Canterbury established St Nicholas-at-Wade as a separate parish, with All Saints' Church as its chapel, served by a vicar and an assistant priest. According to the document by which that was done, the population of the parish of Reculver had grown so large that the provision of a single vicar had become inadequate. While Thanet was then still an island separated from the rest of Kent by the Wantsum Channel

The Wantsum Channel was a strait separating the Isle of Thanet from the north-eastern extremity of the English county of Kent and connecting the English Channel and the Thames Estuary. It was a major shipping route when Britain was part of the Rom ...

, the new arrangement was also prompted by the inconvenience posed by the distance between these chapels on the Isle of Thanet and their mother church at Reculver. However, the document specified that the vicar of the new parish of St Nicholas-at-Wade had to pay £3.3s.4d (£3.17) annually to the vicar of Reculver "as a sign of subjection". The vicar also had to go to Reculver "in procession" with his assistant priest and his parishioners every year on Whit Monday

Whit Monday or Pentecost Monday, also known as Monday of the Holy Spirit, is the holiday celebrated the day after Pentecost, a moveable feast in the Christian liturgical calendar. It is moveable because it is determined by the date of Easter. I ...

– the eighth day after Easter

Easter,Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the '' Book of Common Prayer''; "Easter Sunday", used by James Ussher''The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4'') and Samuel Pepys''The Diary of Samuel ...

– as well as being present at Reculver for the Nativity of the Virgin Mary, the patron saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholicism, Anglicanism, or Eastern Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, clan, family, or perso ...

of Reculver, on 8 September. The visits to Reculver continued in the mid-16th century, when they were recorded by John Leland, and the parish of St Nicholas-at-Wade was still making annual payments to Reculver in the 19th century. Archbishop Winchelsey's instructions also set out relative values for the parishes of Reculver and St Nicholas-at-Wade, in allocating dues for taxes known as "clerical tenths". Reculver was liable for 12s.1d (60.5p), compared to St Nicholas-at-Wade's liability of 11s.4d (57p). The first vicar of St Nicholas-at-Wade was named by Archbishop Winchelsey as Andrew de Grantesete.

Decline

Thomas Elmham's map of the Isle of Thanet, drawn in the early 15th century, shows the church with its tower, but a map of 1596 by Philip Symonson, which shows churches "as they actually appeared", shows a church without a tower. Examination of the church's foundations indicates that it was probably a ruin by the middle of the 15th century and was demolished, but was replaced by a smaller structure, without a tower, up to 20 years later. It may be that material from All Saints' Church was used in the construction of a new clerestory for the nave of St Nicholas' church in the late 15th century, and the medieval baptismal font now in Reculver's parish church of St Mary the Virgin at Hillborough probably came from All Saints'. By 1630 there was no church: in that year, the vicar and

Thomas Elmham's map of the Isle of Thanet, drawn in the early 15th century, shows the church with its tower, but a map of 1596 by Philip Symonson, which shows churches "as they actually appeared", shows a church without a tower. Examination of the church's foundations indicates that it was probably a ruin by the middle of the 15th century and was demolished, but was replaced by a smaller structure, without a tower, up to 20 years later. It may be that material from All Saints' Church was used in the construction of a new clerestory for the nave of St Nicholas' church in the late 15th century, and the medieval baptismal font now in Reculver's parish church of St Mary the Virgin at Hillborough probably came from All Saints'. By 1630 there was no church: in that year, the vicar and churchwarden

A churchwarden is a lay official in a parish or congregation of the Anglican Communion or Catholic Church, usually working as a part-time volunteer. In the Anglican tradition, holders of these positions are ''ex officio'' members of the parish b ...

s of St Nicholas-at-Wade reported the existence of glebe

Glebe (; also known as church furlong, rectory manor or parson's close(s))McGurk 1970, p. 17 is an area of land within an ecclesiastical parish used to support a parish priest. The land may be owned by the church, or its profits may be reserved ...

of called "Allhallows close, in part of which antiently stood the chapel of All Saints, or Alhallows"; and, in 1723, antiquarian John Lewis

John Robert Lewis (February 21, 1940 – July 17, 2020) was an American politician and civil rights activist who served in the United States House of Representatives for from 1987 until his death in 2020. He participated in the 1960 Nashville ...

wrote that the church was "now so entirely demolished, with all the fences around it, that there are no marks of either of them."

The decline of All Saints' Church and the community of Shuart may have begun with the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

of 1348–9. Further, this decline coincides with the closing of the adjacent Wantsum Channel. This channel had been a preferred route for sea-borne trade between England and continental Europe in medieval times, probably providing "a large part of the early prosperity of Kent", besides supporting a local industry collecting salt, but it was progressively blocked by silt

Silt is granular material of a size between sand and clay and composed mostly of broken grains of quartz. Silt may occur as a soil (often mixed with sand or clay) or as sediment mixed in suspension with water. Silt usually has a floury feel when ...

. While tax records of the 15th century show that the inhabitants of Shuart had then included men of the Cinque Port

The Confederation of Cinque Ports () is a historic group of coastal towns in south-east England – predominantly in Kent and Sussex, with one outlier ( Brightlingsea) in Essex. The name is Old French, meaning "five harbours", and alludes to t ...

of Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidstone ...

, shipping through the Wantsum Channel had ceased by about the end of the 15th century, and the northern section adjacent to Shuart was merely a creek by the middle of the 16th century. The abandonment of the church presumably arose through the cost of keeping two churches – All Saints and St Nicholas – in what had become a "remote, rural parish". Shuart continued to be represented in tax records in the 17th century: in 1624 it was assessed as a "vill

Vill is a term used in English history to describe the basic rural land unit, roughly comparable to that of a parish, manor, village or tithing.

Medieval developments

The vill was the smallest territorial and administrative unit—a geographical ...

" at the rate of £4.6s.4d (£4.32) for the archaic taxes known as "fifteenths and tenths" – this rate had been fixed in 1334, and may be compared with the rate for St Nicholas-at-Wade of £10.7s (£10.35) – and Shuart appears as a borgh, or tithing

A tithing or tything was a historic English legal, administrative or territorial unit, originally ten hides (and hence, one tenth of a hundred). Tithings later came to be seen as subdivisions of a manor or civil parish. The tithing's leader or s ...

, in records of the Hearth Tax

A hearth tax was a property tax in certain countries during the medieval and early modern period, levied on each hearth, thus by proxy on wealth. It was calculated based on the number of hearths, or fireplaces, within a municipal area and is ...

for 1673. However, the parish as a whole was in decline. In 1563 the parish of St Nicholas-at-Wade was the second smallest on the Isle of Thanet by number of households, having only 33, and by 1800 there were "not ... near so many". By 1723 the settlement of Shuart was a matter of historical record only. John Lewis wrote then that seems as if anciently a Vill or Town belonged to he chapel of All Saints, and the only building recorded by Lewis was a "good farm house". The farmhouse was built in the late 17th century and still stands, but otherwise today Shuart is considered a deserted medieval village.

Excavation

The site of All Saints' Church, Shuart, was recorded onOrdnance Survey

, nativename_a =

, nativename_r =

, logo = Ordnance Survey 2015 Logo.svg

, logo_width = 240px

, logo_caption =

, seal =

, seal_width =

, seal_caption =

, picture =

, picture_width =

, picture_caption =

, formed =

, preceding1 =

, di ...

maps in the 19th century, and was confirmed in the mid-20th century through aerial photography

Aerial photography (or airborne imagery) is the taking of photographs from an aircraft or other airborne platforms. When taking motion pictures, it is also known as aerial videography.

Platforms for aerial photography include fixed-wing airc ...

by Kenneth St Joseph

John Kenneth Sinclair St Joseph, (13 November 1912 – 11 March 1994) was a British archaeologist, geologist and Royal Air Force (RAF) veteran who pioneered the use of aerial photography as a method of archaeological research in Britain and Irel ...

. On the north side of a road between Shuart Farm and Nether Hale Farm, the site is on farmland now owned by St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge founded by the House of Tudor, Tudor matriarch Lady Margaret Beaufort. In constitutional terms, the college is a charitable corpo ...

, and was excavated with the college's permission by the Thanet Archaeological Unit between 1978 and 1979.

The only surviving part of the main structure was its foundations of rammed chalk

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock. It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed deep under the sea by the compression of microscopic plankton that had settled to the sea floor. Chalk ...

, which nonetheless allowed a construction history to be developed, but various elements of the structure were also found. These included mortar flooring, glazed floor tile

Tiles are usually thin, square or rectangular coverings manufactured from hard-wearing material such as ceramic, stone, metal, baked clay, or even glass. They are generally fixed in place in an array to cover roofs, floors, walls, edges, or o ...

s, green sandstone, Caen stone

Caen stone (french: Pierre de Caen) is a light creamy-yellow Jurassic limestone quarried in north-western France near the city of Caen. The limestone is a fine grained oolitic limestone formed in shallow water lagoons in the Bathonian Age about ...

, Quarr stone from the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Isle of ...

and stained glass. Among stone fragments were numerous carvings, including "two small delicately carved pieces of foliage which are certainly twelfth-century work". Fragments of mortar showing the imprint of barnacles were found among the rubble in the foundation trenches, indicating that some of the stone used in the structure had been fetched from the shoreline. A number of graves were also discovered, one of which had been covered by an unmarked stone, but they had been robbed and filled with rubble containing fragments of human bone. Two of the graves had been dug between the demolition of the church and the construction of a smaller, short-lived replacement in the 15th century. While virtually all of the building's structure had been robbed, presumably for use elsewhere, much of what remained had been destroyed by plough

A plough or plow ( US; both ) is a farm tool for loosening or turning the soil before sowing seed or planting. Ploughs were traditionally drawn by oxen and horses, but in modern farms are drawn by tractors. A plough may have a wooden, iron or ...

ing.

References

Footnotes

Notes

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{Good article Archaeological sites in Kent Former churches in Kent