Alfred Pippard on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Alfred John Sutton Pippard

A few months after the start of

A few months after the start of

/ref>

Upon arriving at Cardiff Pippard set about modernising the department and attracting research opportunities. Pippard's most important research client was the

Upon arriving at Cardiff Pippard set about modernising the department and attracting research opportunities. Pippard's most important research client was the

/ref> In 1951 he was appointed by Hugh Dalton, the Minister of Local Government and Planning, to investigate pollution in the

MBE Mbe may refer to:

* Mbé, a town in the Republic of the Congo

* Mbe Mountains Community Forest, in Nigeria

* Mbe language, a language of Nigeria

* Mbe' language, language of Cameroon

* ''mbe'', ISO 639 code for the extinct Molala language

Molal ...

FRS (6 April 1891 – 2 November 1969) was a British civil engineer and academic. Pippard was the son of a carpenter and joiner

A joiner is an artisan and tradesperson who builds things by joining pieces of wood, particularly lighter and more ornamental work than that done by a carpenter, including furniture and the "fittings" of a house, ship, etc. Joiners may work in ...

and spent much of his early life helping his father on construction sites. Initially supposed to follow his father into the family business, Pippard instead decided to study for a bachelor's degree

A bachelor's degree (from Middle Latin ''baccalaureus'') or baccalaureate (from Modern Latin ''baccalaureatus'') is an undergraduate academic degree awarded by colleges and universities upon completion of a course of study lasting three to six ...

in civil engineering at the University of Bristol

, mottoeng = earningpromotes one's innate power (from Horace, ''Ode 4.4'')

, established = 1595 – Merchant Venturers School1876 – University College, Bristol1909 – received royal charter

, type ...

, supporting himself with an Exhibition award. Pippard worked for a Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

based consulting engineer and for the Pontypridd and Rhondda Valley Joint Water Board in his early career. He also completed his master's degree during this period.

At the start of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

Pippard joined the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

Air Department

The Air Department of the British Admiralty later succeeded briefly by the Air Section followed by the Air Division was established prior to World War I by Winston Churchill to administer the Royal Naval Air Service.

History

In 1908, the Bri ...

where he studied aircraft stresses. After the war he joined an aeronautical engineering

Aerospace engineering is the primary field of engineering concerned with the development of aircraft and spacecraft. It has two major and overlapping branches: aeronautical engineering and astronautical engineering. Avionics engineering is sim ...

consultancy with many of his colleagues and was involved in accident investigation cases. He gained his Doctorate of Science

Doctor of Science ( la, links=no, Scientiae Doctor), usually abbreviated Sc.D., D.Sc., S.D., or D.S., is an academic research degree awarded in a number of countries throughout the world. In some countries, "Doctor of Science" is the degree used f ...

from Bristol in 1920 and took up the chair in Civil Engineering at University College, Cardiff

, latin_name =

, image_name = Shield of the University of Cardiff.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms of Cardiff University

, motto = cy, Gwirionedd, Undod a Chytgord

, mottoeng = Truth, Unity and Concord

, established = 1 ...

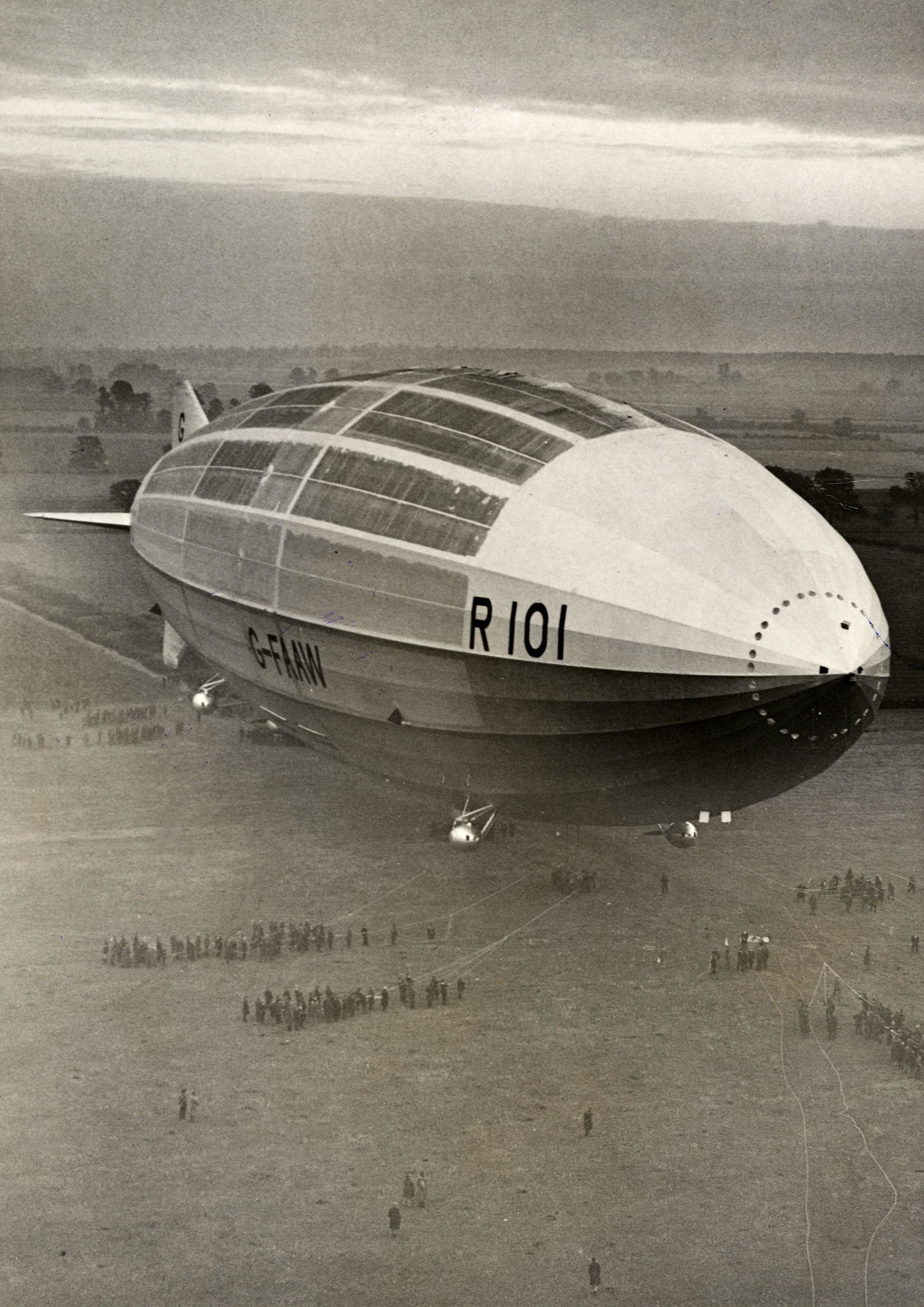

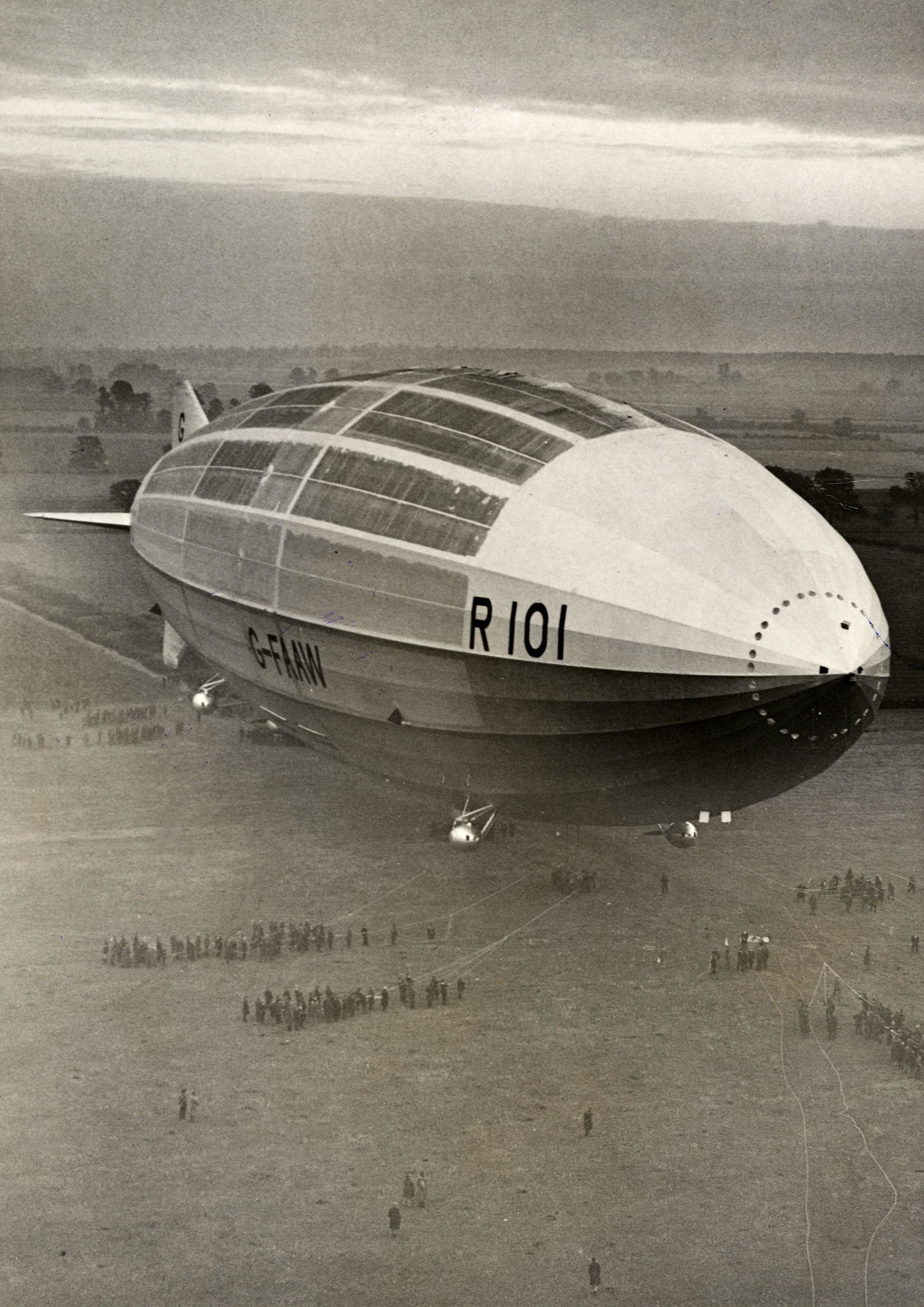

in 1922. This began a long career in academia at Cardiff, Bristol and Imperial College during which he was responsible for the analysis of the methods used in the design of the R100

His Majesty's Airship R100 was a privately designed and built British rigid airship made as part of a two-ship competition to develop a commercial airship service for use on British Empire routes as part of the Imperial Airship Scheme. The ot ...

and R101 airships. The public enquiry into the latter's crash, which ended British participation in airship development, found no faults with Pippard's work but he withdrew from the field of aeronautical engineering – feeling keenly the loss of several of his friends amongst the 48 dead.

During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

Pippard was a member of the Civil Defence Research Committee which met at Princes Risborough and continued his teaching at Imperial College. Pippard was a member of the council of the Institution of Civil Engineers

The Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) is an independent professional association for civil engineers and a charitable body in the United Kingdom. Based in London, ICE has over 92,000 members, of whom three-quarters are located in the UK, whi ...

for fifteen years and was their president for the 1958-9 session. During his later career he chaired the fifteen-year investigation into pollution in the Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

tideway

The Tideway is a part of the River Thames in England which is subject to tides. This stretch of water is downstream from Teddington Lock. The Tideway comprises the upper Thames Estuary including the Pool of London.

Tidal activity

Depending on ...

the length of which he was criticised for by the press. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathemat ...

in 1954 and was pro-rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

of Imperial college for the next year. He retired in 1956 and began a lecture tour of the United States and received honorary degrees from Bristol, Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1. ...

and Brunel Universities.

Early life and training

Alfred John Sutton Pippard was born on 6 April 1891 inYeovil

Yeovil ( ) is a town and civil parish in the district of South Somerset, England. The population of Yeovil at the last census (2011) was 45,784. More recent estimates show a population of 48,564. It is close to Somerset's southern border with ...

and was the son of Alfred Pippard, a carpenter, joiner

A joiner is an artisan and tradesperson who builds things by joining pieces of wood, particularly lighter and more ornamental work than that done by a carpenter, including furniture and the "fittings" of a house, ship, etc. Joiners may work in ...

and devout Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compe ...

. His family had a strong connection with the construction industry and included masons, stonecutters and plasterer

A plasterer is a tradesman or tradesperson who works with plaster, such as forming a layer of plaster on an interior wall or plaster decorative moldings on ceilings or walls. The process of creating plasterwork, called plastering, has been ...

s. The elder Alfred was a renowned craftsman and worked on Yeovil Post Office, the offices of the Western Gazette

The ''Western Gazette'' is a regional newspaper, published every Thursday in Yeovil, Somerset, England.

In 2012, Local World acquired owners Northcliffe Media from Daily Mail and General Trust. Trinity Mirror took control of Local Worl ...

, Yeovil Girls' High School, a bank in Weymouth and several private houses, often working as his own architect and drawing up the plans. During his youth the younger Alfred helped his father on several building sites.

Alfred attended several kindergarten

Kindergarten is a preschool educational approach based on playing, singing, practical activities such as drawing, and social interaction as part of the transition from home to school. Such institutions were originally made in the late 18th ce ...

schools before progressing to Yeovil School after which it was presumed that he would enter into the family business. However he particularly enjoyed his studies and wished to further them, to that end he applied to study at the Merchant Venturers College (which would become the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Bristol

, mottoeng = earningpromotes one's innate power (from Horace, ''Ode 4.4'')

, established = 1595 – Merchant Venturers School1876 – University College, Bristol1909 – received royal charter

, type ...

in 1909). He spent one year working for a local architect and engineer and studying for the London Matriculation exam which he passed in the summer of 1908 and started at the college in the autumn of that year.

During the Easter vacation of his first year at Bristol Pippard's father died and the family was put under great financial strain. With three siblings still at school it was only Pippard's winning of the Proctor Baker Exhibition with the accompanying payment of his tuition fees that allowed him to continue his studies. He graduated from Bristol with first class honours

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a grading structure for undergraduate degrees or bachelor's degrees and integrated master's degrees in the United Kingdom. The system has been applied (sometimes with significant variati ...

in 1911.

Apprenticeship

The laws of theInstitution of Civil Engineers

The Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) is an independent professional association for civil engineers and a charitable body in the United Kingdom. Based in London, ICE has over 92,000 members, of whom three-quarters are located in the UK, whi ...

(ICE) at the time required prospective members to undertake articled work for two years for a corporate member and Pippard arranged to work for Mr Cotterell of Bristol, the father of one of his friends who he had undertaken work for with his father as a joiner. However the family finances were still poor and his mother could not afford to provide him with his keep for two years and pay the premium that all apprenticeships entailed. Fortunately the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851

The Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851 is an institution founded in 1850 to administer the international exhibition of 1851, officially called the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations. The Great Exhibition was held ...

had just started an industrial bursary

A bursary is a monetary award made by any educational institution or funding authority to individuals or groups. It is usually awarded to enable a student to attend school, university or college when they might not be able to, otherwise. Some awa ...

scheme and invited applications from universities across the country. Bristol University submitted Pippard's name and he was accepted as one of ten successful applicants from across the country.

With the financial security provided by the bursary Pippard began work at Cotterell's offices in 1911. One of his first jobs was to design the steelwork for a warehouse in Bristol on which he gave a talk to the local students association of the ICE in 1913 for which he was awarded the Miller Prize and a set of drawing instruments which he used for the rest of his life. He completed his apprenticeship in 1913 and obtained a position as assistant engineer to the Pontypridd and Rhondda Valley Joint Water Board, he did not enjoy this routine work and disliked his district. To continue his interest in civil engineering he began a Master of Science

A Master of Science ( la, Magisterii Scientiae; abbreviated MS, M.S., MSc, M.Sc., SM, S.M., ScM or Sc.M.) is a master's degree in the field of science awarded by universities in many countries or a person holding such a degree. In contrast t ...

dissertation on masonry dam

Masonry dams are dams made out of masonrymainly stone and brick, sometimes joined with mortar. They are either the gravity or the arch-gravity type. The largest masonry dam in the World is Nagarjunasagar Dam , Andhra Pradesh & Telangana, in Ind ...

s which he wrote at evenings and weekends. This was submitted to his alma mater in April 1914, was approved and he subsequently received his MSc.

He began repaying his mother's financial assistance in 1915 and deeply regretted her death in 1921 before he could make any substantial contribution to her retirement.

Admiralty Air Department

A few months after the start of

A few months after the start of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

Pippard resigned from the water board with the intention of helping the war effort. His poor eyesight barred him from a commission in the Royal Engineers so he entered his name of a register organised by the Institution of Civil Engineers to place their members in appropriate wartime jobs. Pippard's name was brought to the attention of HC Watts, who was a university classmate and a member of the technical section of the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

Air Department

The Air Department of the British Admiralty later succeeded briefly by the Air Section followed by the Air Division was established prior to World War I by Winston Churchill to administer the Royal Naval Air Service.

History

In 1908, the Bri ...

. Pippard accepted a post as a technical advisor to the director of the department in January 1915.

Pippard's work with the department was to analyse stresses in airframes to ensure that they could survive the rigours of aerial combat, the work was of great importance to the war effort and he often found himself working for ten to twelve hours at a time. In December 1917 he married Olive Field, also from Yeovil, and they moved into a flat together at Earls Court

Earl's Court is a district of Kensington in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in West London, bordering the rail tracks of the West London line and District line that separate it from the ancient borough of Fulham to the west, the ...

, London. He was appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

in the New Year Honours of 1918. Pippard joined an engineering consultancy in 1919 which was set up by Alec Ogilvie

''For the businessman, see Alec Ogilvie (businessman).''

Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander "Alec" Ogilvie CBE (8 June 1882 – 18 June 1962) was an early British aviation pioneer, a friend of the Wright Brothers and only the seventh British person ...

, an Air Department engineer, and several colleagues. Later that year Pippard and JL Pritchard, another colleague, wrote ''Aeroplane Structures'' which became a standard reference for aeronautical engineers

Aeronautics is the science or art involved with the study, design, and manufacturing of air flight–capable machines, and the techniques of operating aircraft and rockets within the atmosphere. The British Royal Aeronautical Society identifies ...

and was revised in 1935. For this work, amongst others, he was awarded a Doctorate of Science

Doctor of Science ( la, links=no, Scientiae Doctor), usually abbreviated Sc.D., D.Sc., S.D., or D.S., is an academic research degree awarded in a number of countries throughout the world. In some countries, "Doctor of Science" is the degree used f ...

by Bristol University in 1920. The firm was awarded several accident investigation contracts such as investigating the failure of the Tarrant Tabor

The Tarrant Tabor was a British triplane bomber designed towards the end of the First World War and was briefly the world's largest aircraft. It crashed, with fatalities, on its first flight.

Development

The Tabor was the first and only aircraft ...

triplane

A triplane is a fixed-wing aircraft equipped with three vertically stacked wing planes. Tailplanes and canard foreplanes are not normally included in this count, although they occasionally are.

Design principles

The triplane arrangement m ...

and the R38 airship disaster but was unable to win many large contracts due to the military and large aeronautical firms controlling the market. Pippard preferred his work as a visiting lecturer at Imperial College, London

Imperial College London (legally Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine) is a public research university in London, United Kingdom. Its history began with Prince Albert, consort of Queen Victoria, who developed his vision for a c ...

which he had started in 1919 and applied, and was accepted, for the chair of engineering at University College, Cardiff

, latin_name =

, image_name = Shield of the University of Cardiff.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms of Cardiff University

, motto = cy, Gwirionedd, Undod a Chytgord

, mottoeng = Truth, Unity and Concord

, established = 1 ...

in 1922. He also wrote a series of scripts for radio broadcasts, including two made for schools.AIM25 archive material/ref>

Academic life

Upon arriving at Cardiff Pippard set about modernising the department and attracting research opportunities. Pippard's most important research client was the

Upon arriving at Cardiff Pippard set about modernising the department and attracting research opportunities. Pippard's most important research client was the Aeronautical Research Committee

The Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (ACA) was a UK agency founded on 30 April 1909, to undertake, promote, and institutionalize aeronautical research. In 1919 it was renamed the Aeronautical Research Committee, later becoming the Aeronautical ...

which agreed to pay the salary of a full-time assistant from January 1924. During this time Pippard and his assistant, John Baker, worked on proving the methods used to analyse airship frames which were proposed for use on the R100

His Majesty's Airship R100 was a privately designed and built British rigid airship made as part of a two-ship competition to develop a commercial airship service for use on British Empire routes as part of the Imperial Airship Scheme. The ot ...

and R101

R101 was one of a pair of British rigid airships completed in 1929 as part of a British government programme to develop civil airships capable of service on long-distance routes within the British Empire. It was designed and built by an Air Mi ...

airship

An airship or dirigible balloon is a type of aerostat or lighter-than-air aircraft that can navigate through the air under its own power. Aerostats gain their lift from a lifting gas that is less dense than the surrounding air.

In early ...

s. In 1928 Pippard was invited to take over the chair of civil engineering at Bristol University which he accepted.

At Bristol Pippard implemented many of the modernising methods he has developed at Cardiff and continued his work on the R100 and R101. He took part in the first test flight of the R101 but due to political pressure for quick development he was unable to finish his structural report before the R101 crashed on her final test flight on 5 October 1930, spelling the end for airship development in the United Kingdom. The public enquiry found that there were no faults with the airship's structure or the design methods employed by Pippard. However Pippard was so affected by the episode, particularly as several of his friends were among the 48 dead, that he withdrew from the field of aeronautical engineering and thereafter concentrated on civil engineering. He moved to Imperial College in London in 1933 and took over the running of the civil engineering department there where he actively encouraged a more research centric teaching method. This attitude was demonstrated in a paper presented to the Royal Aeronautical Society

The Royal Aeronautical Society, also known as the RAeS, is a British multi-disciplinary professional institution dedicated to the global aerospace community. Founded in 1866, it is the oldest aeronautical society in the world. Members, Fellows, ...

in 1935 in which he states that "University years should be devoted to the study of engineering science with as little emphasis as possible on the practical interests of the work". Pippard himself remained involved with the department's research, being particularly interested in the structural aspects of dams. For example, he recognised the importance of soil mechanics very early on, arranged lectures by Karl von Terzaghi in 1939 and supported Alec W. Skempton, that later doyen of British soil mechanics.

Pippard was also influential in the career of Letitia Chitty

Letitia Chitty (15 July 1897 – 29 September 1982) was an English engineer who became a respected structural analytical engineer, achieving several firsts for women engineers, including becoming the first female fellow of the Royal Aeronautica ...

, recruiting the then promising mathematician to work at the Admiralty Air Department during World War I, an experience that prompted her to switch to engineering. She later joined Pippard at Imperial College working on aircraft and airship structural analysis projects.

Second World War

In April 1939, predicting the approaching war, Pippard joined the Civil Defence Research Committee at the invitation ofSir John Anderson

John Anderson, 1st Viscount Waverley, (8 July 1882 – 4 January 1958) was a Scottish civil servant and politician who is best known for his service in the War Cabinet during the Second World War, for which he was nicknamed the "Home Front Pr ...

, Lord Privy Seal and minister in charge of air raid precautions. At the outbreak of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

on 3 September 1939 he was assigned to the research and experiments section located in Princes Risborough. The section had little work to do and Pippard found himself bored, especially compared to his frantic work with the Air Department during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. Fortunately the government's decision to allow university students to complete their degrees before compulsory national service

National service is the system of voluntary government service, usually military service. Conscription is mandatory national service. The term ''national service'' comes from the United Kingdom's National Service (Armed Forces) Act 1939.

The ...

meant that Pippard could spend four days of his week lecturing at Imperial College whilst remaining a member of the committee, a practice he continued for the rest of the war.

Post-war

Pippard was elected to the council of theInstitution of Civil Engineers

The Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) is an independent professional association for civil engineers and a charitable body in the United Kingdom. Based in London, ICE has over 92,000 members, of whom three-quarters are located in the UK, whi ...

in 1944 in which he continued to sit for the next fifteen years, advocating an increased academic presence in that body. His dedication to the institution led to his election as president for the 1958-9 session.

In 1946 he introduced concrete and soil mechanics lecturers to the staff of Imperial College for the first time.Imperial College biography/ref> In 1951 he was appointed by Hugh Dalton, the Minister of Local Government and Planning, to investigate pollution in the

Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

tideway

The Tideway is a part of the River Thames in England which is subject to tides. This stretch of water is downstream from Teddington Lock. The Tideway comprises the upper Thames Estuary including the Pool of London.

Tidal activity

Depending on ...

. This was a highly complex task which involved fifteen years of detailed investigation for which he was, perhaps unfairly, ridiculed in the press. Pippard was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathemat ...

in 1954 and became pro-rector (assistant to the rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

) of Imperial College the next year. After a year in this capacity Pippard retired in September 1956.

Retirement

Upon retirement Pippard began a series of visiting lectures atNorthwestern University

Northwestern University is a private research university in Evanston, Illinois. Founded in 1851, Northwestern is the oldest chartered university in Illinois and is ranked among the most prestigious academic institutions in the world.

Charte ...

in Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rockf ...

, United States. During his time in the US Pippard also delivered lectures at Berkeley

Berkeley most often refers to:

*Berkeley, California, a city in the United States

**University of California, Berkeley, a public university in Berkeley, California

* George Berkeley (1685–1753), Anglo-Irish philosopher

Berkeley may also refer ...

, Purdue, Harvard and Urbana. Upon returning from America he took on the duties of the president of the Institution of Civil Engineers, which included a two-month visit to South Africa. In 1966 Pippard was awarded honorary degrees from both Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

and Birmingham Universities and from Brunel University

Brunel University London is a public research university located in the Uxbridge area of London, England. It was founded in 1966 and named after the Victorian engineer and pioneer of the Industrial Revolution, Isambard Kingdom Brunel. In June ...

in 1968. Pippard continued to write on the theory of structures throughout his retirement and over the course of his life authored (or co-author

Collaborative writing, or collabwriting is a method of group work that takes place in the workplace and in the classroom. Researchers expand the idea of collaborative writing beyond groups working together to complete a writing task. Collaboration ...

ed) more than 80 academic papers

Academic publishing is the subfield of publishing which distributes academic research and scholarship. Most academic work is published in academic journal articles, books or thesis, theses. The part of academic written output that is not forma ...

and six books. Towards the end of his life he began writing an autobiography which remained unfinished on his death. Pippard died in Putney

Putney () is a district of southwest London, England, in the London Borough of Wandsworth, southwest of Charing Cross. The area is identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London.

History

Putney is an ancient paris ...

, London on 2 November 1969 and the memorial service was held at St. Margaret's Church in Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

.

References

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Pippard, Alfred 1891 births 1969 deaths People from Yeovil People educated at Yeovil School English civil engineers Presidents of the Institution of Civil Engineers Fellows of the Royal Society Members of the Order of the British Empire Academics of Cardiff University Academics of Imperial College London Alumni of the University of Bristol Deans of the City and Guilds College