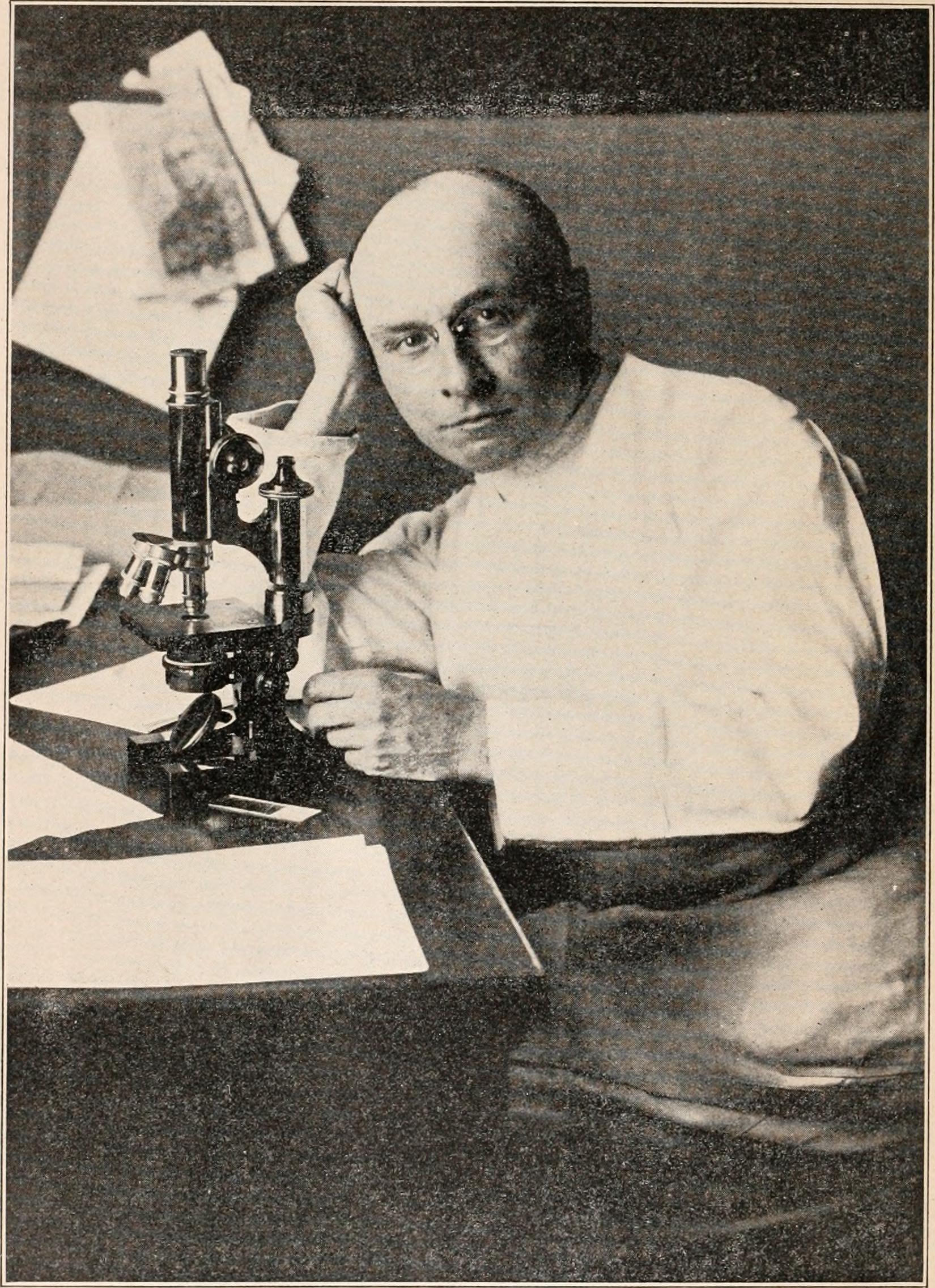

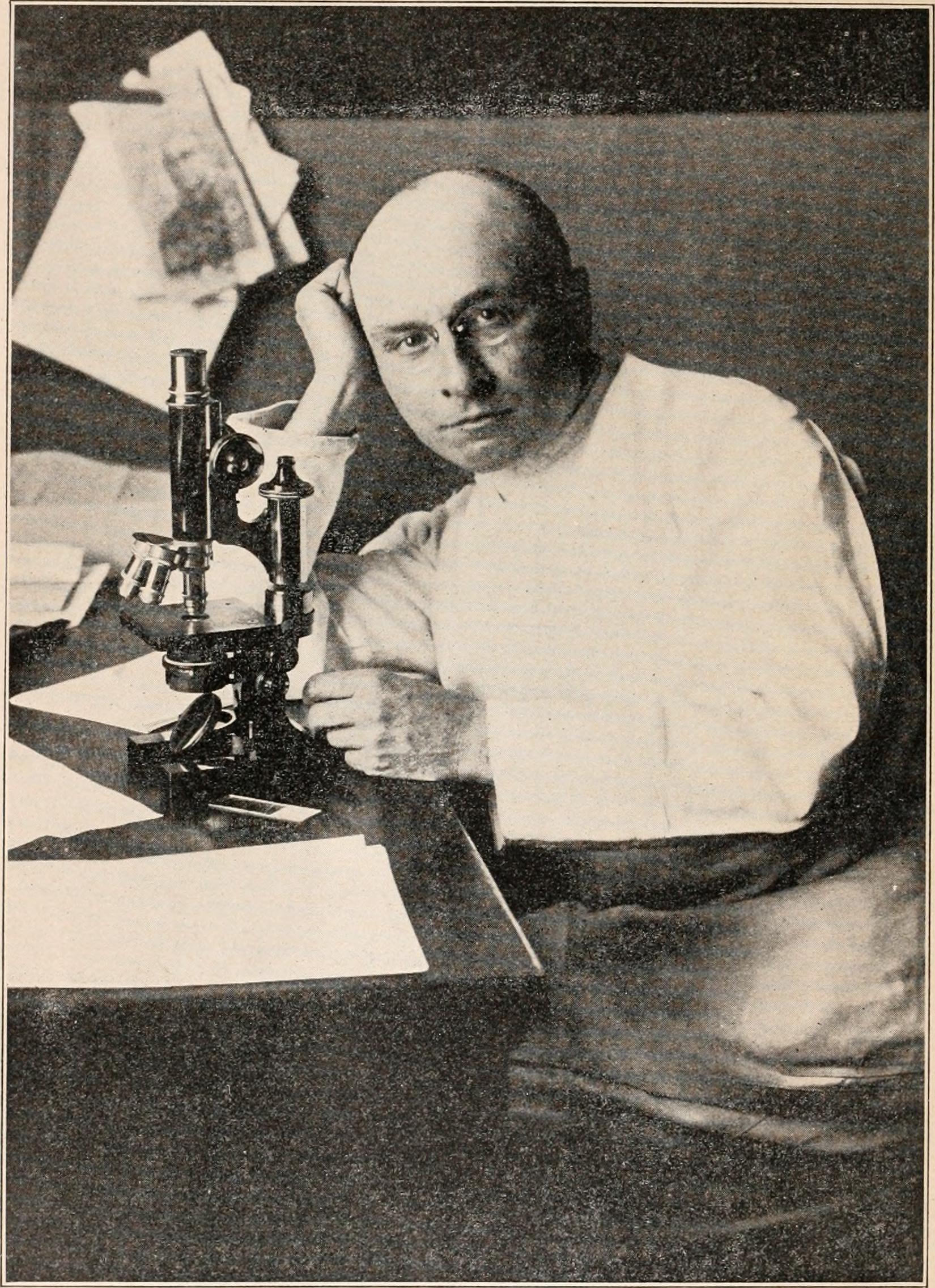

Alexis Carrel on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Alexis Carrel (; 28 June 1873 – 5 November 1944) was a French surgeon and biologist who was awarded the

Alexis Carrel (; 28 June 1873 – 5 November 1944) was a French surgeon and biologist who was awarded the

''Alexis Carrel, Pioneer Surgeon''

Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina.(see Reggiano (2002) as well as Caillois, p. 107) A

''The Voyage to Lourdes''

describing his experience, although it was not published until four years after his death. This was a detriment to his career and reputation among his fellow doctors, and feeling he had no future in academic medicine in France, he emigrated to Canada with the intention of farming and raising cattle. After a brief period, he accepted an appointment at the University of Chicago and, two years later, at the Rockefeller Institute of Medical Research.

In 1935, Carrel published a book titled ''L'Homme, cet inconnu'' (''Man, the Unknown''), which became a best-seller. In the book, he attempted to outline a comprehensive account of what is known and more importantly unknown of the human body and human life "in light of discoveries in biology, physics, and medicine", to elucidate problems of the modern world, and to provide possible routes to a better life for human beings.

For Carrel, the fundamental problem was that:

In 1935, Carrel published a book titled ''L'Homme, cet inconnu'' (''Man, the Unknown''), which became a best-seller. In the book, he attempted to outline a comprehensive account of what is known and more importantly unknown of the human body and human life "in light of discoveries in biology, physics, and medicine", to elucidate problems of the modern world, and to provide possible routes to a better life for human beings.

For Carrel, the fundamental problem was that:

In 1937, Carrel joined Jean Coutrot's ''Centre d'Etudes des Problèmes Humains'' - Coutrot's aim was to develop what he called an "economic humanism" through "collective thinking." In 1941, through connections to the cabinet of Vichy France president

In 1937, Carrel joined Jean Coutrot's ''Centre d'Etudes des Problèmes Humains'' - Coutrot's aim was to develop what he called an "economic humanism" through "collective thinking." In 1941, through connections to the cabinet of Vichy France president

''L'Homme, cet inconnu d'Alexis Carrel (1935). Anatomie d'un succès, analyse d'un échec''

Paris, Classiques Garnier, « Littérature, Histoire, Politique, 38 », 2019. * Feuerwerker, Elie. ''Alexis Carrel et l'eugénisme.'' Le Monde, 1er Juillet 1986. * Bonnafé, Lucien and Tort, Patrick. ''L'Homme, cet inconnu? Alexis Carrel, Jean-Marie le Pen et les chambres a gaz'' Editions Syllepse, 1996. * David Zane Mairowitz. "''Fascism à la mode: in France, the far right presses for national purity''", Harper's Magazine; 10/1/1997 * Berman, Paul. ''Terror and Liberalism'' W. W. Norton, 2003. * Walther, Rudolph. ''Die seltsamen Lehren des Doktor Carrel''

''DIE ZEIT'', 31.07.2003 Nr. 32

* Terrenoire, Gwen, CNRS. ''Eugenics in France (1913–1941) : a review of research findings'' Joint Programmatic Commission UNESCO-ONG Science and Ethics, 24 March 2003

Comité de Liaison ONG-UNESCO

Borghi L. (2015) "Heart Matters. The Collaboration Between Surgeons and Engineers in the Rise of Cardiac Surgery". In: Pisano R. (eds) A Bridge between Conceptual Frameworks. History of Mechanism and Machine Science, vol 27. Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 53–68

Research Foundation entitled to Alexis Carrel

* ''Time'', 16 October 1944

''Time'', 13 November 1944 {{DEFAULTSORT:Carrel, Alexis 1873 births 1944 deaths French eugenicists Converts to Roman Catholicism from atheism or agnosticism French Nobel laureates Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine French Roman Catholics French collaborators with Nazi Germany Chevaliers of the Légion d'honneur Members of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences Corresponding Members of the Russian Academy of Sciences (1917–1925) Corresponding Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences Honorary Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences People from Sainte-Foy-lès-Lyon French vascular surgeons History of transplant surgery Rockefeller University people 20th-century French physicians

Alexis Carrel (; 28 June 1873 – 5 November 1944) was a French surgeon and biologist who was awarded the

Alexis Carrel (; 28 June 1873 – 5 November 1944) was a French surgeon and biologist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine ( sv, Nobelpriset i fysiologi eller medicin) is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute, Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or ...

in 1912 for pioneering vascular suturing techniques. He invented the first perfusion pump with Charles A. Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. On May 20–21, 1927, Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, a distance o ...

opening the way to organ transplantation

Organ transplantation is a medical procedure in which an organ (anatomy), organ is removed from one body and placed in the body of a recipient, to replace a damaged or missing organ. The donor and recipient may be at the same location, or organ ...

. His positive description of a miraculous healing he witnessed during a pilgrimage earned him scorn of some of his colleagues. This prompted him to relocate to the United States, where he lived most of his life. He had a leading role in implementing eugenic policies in Vichy France.Sade, Robert M. MD''Alexis Carrel, Pioneer Surgeon''

Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina.(see Reggiano (2002) as well as Caillois, p. 107) A

Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfre ...

laureate in 1912, Alexis Carrel was also elected twice, in 1924 and 1927, as an honorary member of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR.

Biography

Born in Sainte-Foy-lès-Lyon, Rhône, Carrel was raised in a devout Catholic family and was educated byJesuits

The Society of Jesus ( la, Societas Iesu; abbreviation: SJ), also known as the Jesuits (; la, Iesuitæ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

, though he had become an agnostic by the time he became a university student. He was a pioneer in transplantology and thoracic surgery. Alexis Carrel was also a member of learned societies in the U.S., Spain, Russia, Sweden, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Vatican City, Germany, Italy and Greece and received honorary doctorates from Queen's University of Belfast, Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the n ...

, California, New York, Brown University and Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manha ...

.

In 1902, he was claimed to have witnessed the miraculous cure of Marie Bailly at Lourdes, made famous in part because she named Carrel as a witness of her cure. After the notoriety surrounding the event, Carrel could not obtain a hospital appointment because of the pervasive anticlericalism in the French university system at the time. In 1903, he emigrated to Montreal, Canada, but soon relocated to Chicago, Illinois, to work for Hull Laboratory. While there he collaborated with American physician Charles Claude Guthrie in work on vascular suture and the transplantation of blood vessels and organs as well as the head, and Carrel was awarded the 1912 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine ( sv, Nobelpriset i fysiologi eller medicin) is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute, Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or ...

for these efforts.

In 1906, he joined the newly formed Rockefeller Institute of Medical Research in New York where he spent the rest of his career.Reggiani There he did significant work on tissue cultures with pathologist Montrose Thomas Burrows. In the 1930s, Carrel and Charles Lindbergh became close friends not only because of the years they worked together but also because they shared personal, political, and social views. Lindbergh initially sought out Carrel to see if his sister-in-law's heart, damaged by rheumatic fever, could be repaired. When Lindbergh saw the crudeness of Carrel's machinery, he offered to build new equipment for the scientist. Eventually they built the first perfusion pump, an invention instrumental to the development of organ transplantation and open heart surgery. Lindbergh considered Carrel his closest friend, and said he would preserve and promote Carrel's ideals after his death.

Due to his close proximity with Jacques Doriot's fascist Parti Populaire Français

The French Popular Party (french: Parti populaire français) was a French fascist and anti-semitic political party led by Jacques Doriot before and during World War II. It is generally regarded as the most collaborationist party of France.

...

(PPF) during the 1930s and his role in implementing eugenics policies during Vichy France, he was accused after the Liberation of collaboration, but died before the trial.

In his later life he returned to his Catholic roots. In 1939, he met with Trappist monk Alexis Presse on a recommendation. Although Carrel was skeptical about meeting with a priest, Presse ended up having a profound influence on the rest of Carrel's life. In 1942, he said "I believe in the existence of God, in the immortality of the soul, in Revelation and in all the Catholic Church teaches." He summoned Presse to administer the Catholic Sacraments on his death bed in November 1944.

For much of his life, Carrel and his wife spent their summers on the , which they owned. After he and Lindbergh became close friends, Carrel persuaded him to also buy a neighboring island, the Ile Illiec

Ile may refer to:

* iLe, a Puerto Rican singer

* Ile District (disambiguation), multiple places

* Ilé-Ifẹ̀, an ancient Yoruba city in south-western Nigeria

* Interlingue (ISO 639:ile), a planned language

* Isoleucine, an amino acid

* Another ...

, where the Lindberghs often resided in the late 1930s.

Contributions to science

Vascular suture

Carrel was a young surgeon in 1894, when the French president Sadi Carnot was assassinated with a knife. Carnot bled to death due to severing of his portal vein, and surgeons who treated the president felt that the vein could not be successfully reconnected. This left a deep impression on Carrel, and he set about developing new techniques for suturing blood vessels. The technique of "triangulation", using three stay-sutures as traction points in order to minimize damage to the vascular wall during suturing, was inspired by sewing lessons he took from an embroideress and is still used today. Julius Comroe wrote: "Between 1901 and 1910, Alexis Carrel, using experimental animals, performed every feat and developed every technique known to vascular surgery today." He had great success in reconnecting arteries and veins, and performing surgical grafts, and this led to his Nobel Prize in 1912.Wound antisepsis

DuringWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

(1914–1918), Carrel and the English chemist Henry Drysdale Dakin developed the Carrel–Dakin method Dakin's solution is a dilute solution of sodium hypochlorite (0.4% to 0.5%) and other stabilizing ingredients, traditionally used as an antiseptic, e.g. to cleanse wounds in order to prevent infection.Jeffrey M. Levine (2013): "Dakin’s Solution ...

of treating wounds based on chlorine (Dakin's solution) which, preceding the development of antibiotics, was a major medical advance in the care of traumatic wounds. For this, Carrel was awarded the Légion d'honneur

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon B ...

. Carrel also advocated the use of wound debridement (cutting away necrotic or otherwise damaged tissue) and irrigation of wounds. His method of wound irrigation involved flushing the tissues with a high volume of antiseptic fluid so that dirt and other contaminants would be washed away (this is known today as "mechanical irrigation.") The World War I era Rockefeller War Demonstration Hospital

Rockefeller Demonstration Hospital, also known as Rockefeller base hospital and United States Army Auxiliary Hospital No. 1 was a World War One era field hospital designed, located and operated by Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research ...

(United States Army Auxiliary Hospital No. 1) was created, in part, to promote the Carrel–Dakin method:

"The war demonstration hospital of the Rockefeller Institute was planned as a school in which to teach military surgeons the principles of and art of applying the Carrel-Dakin treatment."

Organ transplants

Carrel co-authored a book with pilotCharles A. Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. On May 20–21, 1927, Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, a distance o ...

, ''The Culture of Organs'', and worked with Lindbergh in the mid-1930s to create the "perfusion pump," which allowed living organs to exist outside the body during surgery. The advance is said to have been a crucial step in the development of open-heart surgery

Cardiac surgery, or cardiovascular surgery, is surgery on the heart or great vessels performed by cardiac surgeons. It is often used to treat complications of ischemic heart disease (for example, with coronary artery bypass grafting); to corr ...

and organ transplants, and to have laid the groundwork for the artificial heart, which became a reality decades later. Some critics of Lindbergh claimed that Carrel overstated Lindbergh's role to gain media attention, but other sources say Lindbergh played an important role in developing the device. Both Lindbergh and Carrel appeared on the cover of ''Time'' magazine on 13 June 1938.

Cellular senescence

Carrel was also interested in the phenomenon of senescence, or aging. He claimed that all cells continued to grow indefinitely, and this became a dominant view in the early 20th century. page 24. Carrel started an experiment on 17 January 1912, where he placed tissue cultured from anembryo

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male sperm ...

nic chicken heart in a stoppered Pyrex flask of his own design. He maintained the living culture for over 20 years with regular supplies of nutrient. This was longer than a chicken's normal lifespan. The experiment, which was conducted at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, attracted considerable popular and scientific attention.

Carrel's experiment was never successfully replicated, and in the 1960s Leonard Hayflick and Paul Moorhead

Paul may refer to:

*Paul (given name), a given name (includes a list of people with that name)

*Paul (surname), a list of people

People

Christianity

*Paul the Apostle (AD c.5–c.64/65), also known as Saul of Tarsus or Saint Paul, early Chris ...

proposed that differentiated cells can undergo only a limited number of divisions before dying. This is known as the Hayflick limit, and is now a pillar of biology.

It is not certain how Carrel obtained his anomalous results. Leonard Hayflick suggests that the daily feeding of nutrient was continually introducing new living cells to the alleged immortal culture. J. A. Witkowski has argued that, while "immortal" strains of visibly mutated cells have been obtained by other experimenters, a more likely explanation is deliberate introduction of new cells into the culture, possibly without Carrel's knowledge.

Honors

In 1972, the Swedish Post Office honored Carrel with a stamp that was part of its Nobel stamp series. In 1979, the lunar crater Carrel was named after him as a tribute to his scientific breakthroughs. In February 2002, as part of celebrations of the 100th anniversary of Charles Lindbergh's birth, the Medical University of South Carolina at Charleston established the Lindbergh-Carrel Prize, given to major contributors to "development of perfusion and bioreactor technologies for organ preservation and growth". Michael DeBakey and nine other scientists received the prize, a bronze statuette created for the event by the Italian artist C. Zoli and named "Elisabeth" after Elisabeth Morrow, sister of Lindbergh's wife Anne Morrow, who died from heart disease. It was in fact Lindbergh's disappointment that contemporary medical technology could not provide an artificial heart pump which would allow for heart surgery on her that led to Lindbergh's first contact with Carrel.Alexis Carrel and Lourdes

In 1902, Alexis B went from being a skeptic of the visions and miracles reported at Lourdes to being a believer in spiritual cures after experiencing a healing of Marie Bailly that he could not explain. The Catholic journal ''Le nouvelliste'' reported that she named him as the prime witness of her cure. Alexis Carrel refused to discount a supernatural explanation and steadfastly reiterated his beliefs, even writing the boo''The Voyage to Lourdes''

describing his experience, although it was not published until four years after his death. This was a detriment to his career and reputation among his fellow doctors, and feeling he had no future in academic medicine in France, he emigrated to Canada with the intention of farming and raising cattle. After a brief period, he accepted an appointment at the University of Chicago and, two years later, at the Rockefeller Institute of Medical Research.

''Man, the Unknown'' (1935, 1939)

In 1935, Carrel published a book titled ''L'Homme, cet inconnu'' (''Man, the Unknown''), which became a best-seller. In the book, he attempted to outline a comprehensive account of what is known and more importantly unknown of the human body and human life "in light of discoveries in biology, physics, and medicine", to elucidate problems of the modern world, and to provide possible routes to a better life for human beings.

For Carrel, the fundamental problem was that:

In 1935, Carrel published a book titled ''L'Homme, cet inconnu'' (''Man, the Unknown''), which became a best-seller. In the book, he attempted to outline a comprehensive account of what is known and more importantly unknown of the human body and human life "in light of discoveries in biology, physics, and medicine", to elucidate problems of the modern world, and to provide possible routes to a better life for human beings.

For Carrel, the fundamental problem was that:

n cannot follow modern civilization along its present course, because they are degenerating. They have been fascinated by the beauty of the sciences of inert matter. They have not understood that their body and consciousness are subjected to natural laws, more obscure than, but as inexorable as, the laws of the sidereal world. Neither have they understood that they cannot transgress these laws without being punished. They must, therefore, learn the necessary relations of the cosmic universe, of their fellow men, and of their inner selves, and also those of their tissues and their mind. Indeed, man stands above all things. Should he degenerate, the beauty of civilization, and even the grandeur of the physical universe, would vanish. ... Humanity's attention must turn from the machines of the world of inanimate matter to the body and the soul of man, to the organic and mental processes which have created the machines and the universe of Newton and Einstein.Carrel advocated, in part, that mankind could better itself by following the guidance of an elite group of intellectuals, and by incorporating eugenics into the social framework. He argued for an aristocracy springing from individuals of potential, writing:

We must single out the children who are endowed with high potentialities, and develop them as completely as possible. And in this manner give to the nation a non-hereditary aristocracy. Such children may be found in all classes of society, although distinguished men appear more frequently in distinguished families than in others. The descendants of the founders of American civilization may still possess the ancestral qualities. These qualities are generally hidden under the cloak of degeneration. But this degeneration is often superficial. It comes chiefly from education, idleness, lack of responsibility and moral discipline. The sons of very rich men, like those of criminals, should be removed while still infants from their natural surroundings. Thus separated from their family, they could manifest their hereditary strength. In the aristocratic families of Europe there are also individuals of great vitality. The issue of the Crusaders is by no means extinct. The laws of genetics indicate the probability that the legendary audacity and love of adventure can appear again in the lineage of the feudal lords. It is possible also that the offspring of the great criminals who had imagination, courage, and judgment, of the heroes of the French or Russian Revolutions, of the high-handed business men who live among us, might be excellent building stones for an enterprising minority. As we know, criminality is not hereditary if not united with feeble-mindedness or other mental or cerebral defects. High potentialities are rarely encountered in the sons of honest, intelligent, hard-working men who have had ill luck in their careers, who have failed in business or have muddled along all their lives in inferior positions. Or among peasants living on the same spot for centuries. However, from such people sometimes spring artists, poets, adventurers, saints. A brilliantly gifted and well-known New York family came from peasants who cultivated their farm in the south of France from the time of Charlemagne to that of Napoleon.Carrel advocated for euthanasia for criminals, and the criminally insane, specifically endorsing the use of gassing:

(t)he conditioning of petty criminals with the whip, or some more scientific procedure, followed by a short stay in hospital, would probably suffice to insure order. Those who have murdered, robbed while armed with automatic pistol or machine gun, kidnapped children, despoiled the poor of their savings, misled the public in important matters, should be humanely and economically disposed of in small euthanasic institutions supplied with proper gasses. A similar treatment could be advantageously applied to the insane, guilty of criminal acts.Otherwise he endorsed voluntary positive eugenics. He wrote:

We have mentioned that natural selection has not played its part for a long while. That many inferior individuals have been conserved through the efforts of hygiene and medicine. But we cannot prevent the reproduction of the weak when they are neither insane nor criminal. Or destroy sickly or defective children as we do the weaklings in a litter of puppies. The only way to obviate the disastrous predominance of the weak is to develop the strong. Our efforts to render normal the unfit are evidently useless. We should, then, turn our attention toward promoting the optimum growth of the fit. By making the strong still stronger, we could effectively help the weak; For the herd always profits by the ideas and inventions of the elite. Instead of leveling organic and mental inequalities, we should amplify them and construct greater men.He continued: Carrel's endorsement of euthanasia of the criminal and insane was published in the mid-1930s, prior to the implementation of death camps and gas chambers in

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. In the 1936 German introduction of his book, at the publisher's request, he added the following praise of the Nazi regime which did not appear in the editions in other languages:

(t)he German government has taken energetic measures against the propagation of the defective, the mentally diseased, and the criminal. The ideal solution would be the suppression of each of these individuals as soon as he has proven himself to be dangerous.

French Foundation for the Study of Human Problems

In 1937, Carrel joined Jean Coutrot's ''Centre d'Etudes des Problèmes Humains'' - Coutrot's aim was to develop what he called an "economic humanism" through "collective thinking." In 1941, through connections to the cabinet of Vichy France president

In 1937, Carrel joined Jean Coutrot's ''Centre d'Etudes des Problèmes Humains'' - Coutrot's aim was to develop what he called an "economic humanism" through "collective thinking." In 1941, through connections to the cabinet of Vichy France president Philippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Pétain (24 April 1856 – 23 July 1951), commonly known as Philippe Pétain (, ) or Marshal Pétain (french: Maréchal Pétain), was a French general who attained the position of Marshal of France at the end of Worl ...

(specifically, French industrial physicians André Gros and Jacques Ménétrier) he went on to advocate for the creation of the French Foundation for the Study of Human Problems ( which was created by decree of the Vichy regime in 1941, and where he served as "regent".

The foundation was at the origin of the 11 October 1946, law, enacted by the Provisional Government of the French Republic (GPRF), which institutionalized the field of occupational medicine. It worked on demographics (Robert Gessain, Paul Vincent, Jean Bourgeois-Pichat), on economics

Economics () is the social science that studies the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interactions of economic agents and how economies work. Microeconomics analy ...

, ( François Perroux), on nutrition (Jean Sutter), on habitation (Jean Merlet) and on the first opinion polls (Jean Stoetzel). "The foundation was chartered as a public institution under the joint supervision of the ministries of finance and public health. It was given financial autonomy and a budget of forty million francs—roughly one franc per inhabitant—a true luxury considering the burdens imposed by the German Occupation on the nation's resources. By way of comparison, the whole Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) was given a budget of fifty million francs."

The Foundation made many positive accomplishments during its time. It promoted the 16 December 1942 Act which established the prenuptial certificate, which was required before marriage, and was aimed at insuring the good health of the spouses, in particular in regard to sexually transmitted diseases (STD) and "life hygiene". The institute also established the ', which could be used to record students' grades in the French secondary schools, and thus classify and select them according to scholastic performance.

According to Gwen Terrenoire, writing in ''Eugenics in France (1913–1941) : a review of research findings'', "The foundation was a pluridisciplinary centre that employed around 300 researchers (mainly statisticians, psychologists, physicians) from the summer of 1942 to the end of the autumn of 1944. After the liberation of Paris, Carrel was suspended by the Minister of Health; he died in November 1944, but the Foundation itself was "purged", only to reappear in a short time as the Institut national d'études démographiques (INED) that is still active."Gwen Terrenoire, "Eugenics in France (1913–1941) a review of research findings", Joint Programmatic Commission UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. I ...

-ONG Science and Ethics, 2003 Although Carrel himself was dead most members of his team did move to the INED, which was led by demographist

Demography () is the statistical study of populations, especially human beings.

Demographic analysis examines and measures the dimensions and dynamics of populations; it can cover whole societies or groups defined by criteria such as edu ...

Alfred Sauvy

Alfred Sauvy (31 October 1898 – 30 October 1990) was a demographer, anthropologist and historian of the French economy. Sauvy coined the term Third World ("Tiers Monde") in reference to countries that were unaligned with either the Communis ...

, who coined the expression "Third World

The term "Third World" arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the Nor ...

". Others joined Robert Debré's "Institut national d'hygiène

An institute is an organisational body created for a certain purpose. They are often research organisations ( research institutes) created to do research on specific topics, or can also be a professional body.

In some countries, institutes ca ...

" (National Hygiene Institute), which later became the INSERM.

See also

* HeLaNotes

References

Citations

Cited sources

* * * * * * *Further reading

* * Etienne Lepicard''L'Homme, cet inconnu d'Alexis Carrel (1935). Anatomie d'un succès, analyse d'un échec''

Paris, Classiques Garnier, « Littérature, Histoire, Politique, 38 », 2019. * Feuerwerker, Elie. ''Alexis Carrel et l'eugénisme.'' Le Monde, 1er Juillet 1986. * Bonnafé, Lucien and Tort, Patrick. ''L'Homme, cet inconnu? Alexis Carrel, Jean-Marie le Pen et les chambres a gaz'' Editions Syllepse, 1996. * David Zane Mairowitz. "''Fascism à la mode: in France, the far right presses for national purity''", Harper's Magazine; 10/1/1997 * Berman, Paul. ''Terror and Liberalism'' W. W. Norton, 2003. * Walther, Rudolph. ''Die seltsamen Lehren des Doktor Carrel''

''DIE ZEIT'', 31.07.2003 Nr. 32

* Terrenoire, Gwen, CNRS. ''Eugenics in France (1913–1941) : a review of research findings'' Joint Programmatic Commission UNESCO-ONG Science and Ethics, 24 March 2003

Comité de Liaison ONG-UNESCO

Borghi L. (2015) "Heart Matters. The Collaboration Between Surgeons and Engineers in the Rise of Cardiac Surgery". In: Pisano R. (eds) A Bridge between Conceptual Frameworks. History of Mechanism and Machine Science, vol 27. Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 53–68

External links

* including the Nobel Lecture on December 11, 1912 ''Suture of Blood-Vessels and Transplantation of Organs''Research Foundation entitled to Alexis Carrel

* ''Time'', 16 October 1944

''Time'', 13 November 1944 {{DEFAULTSORT:Carrel, Alexis 1873 births 1944 deaths French eugenicists Converts to Roman Catholicism from atheism or agnosticism French Nobel laureates Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine French Roman Catholics French collaborators with Nazi Germany Chevaliers of the Légion d'honneur Members of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences Corresponding Members of the Russian Academy of Sciences (1917–1925) Corresponding Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences Honorary Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences People from Sainte-Foy-lès-Lyon French vascular surgeons History of transplant surgery Rockefeller University people 20th-century French physicians