Alexandre Dumas, père on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Alexandre Dumas (, ; ; born Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie (), 24 July 1802 – 5 December 1870), also known as Alexandre Dumas père (where '' '' is

Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie (later known as Alexandre Dumas) was born in 1802 in

Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie (later known as Alexandre Dumas) was born in 1802 in

While working for Louis-Philippe, Dumas began writing articles for magazines and plays for the theatre. As an adult, he used his slave grandmother's surname of Dumas, as his father had done as an adult. His first play, ''Henry III and His Courts'', produced in 1829 when he was 27 years old, met with acclaim. The next year, his second play, ''Christine'', was equally popular. These successes gave him sufficient income to write full-time.

In 1830, Dumas participated in the

While working for Louis-Philippe, Dumas began writing articles for magazines and plays for the theatre. As an adult, he used his slave grandmother's surname of Dumas, as his father had done as an adult. His first play, ''Henry III and His Courts'', produced in 1829 when he was 27 years old, met with acclaim. The next year, his second play, ''Christine'', was equally popular. These successes gave him sufficient income to write full-time.

In 1830, Dumas participated in the

Dumas's novels were so popular that they were soon translated into English and other languages. His writing earned him a great deal of money, but he was frequently insolvent, as he spent lavishly on women and sumptuous living. (Scholars have found that he had a total of 40 mistresses.) In 1846, he had built a country house outside Paris at

Dumas's novels were so popular that they were soon translated into English and other languages. His writing earned him a great deal of money, but he was frequently insolvent, as he spent lavishly on women and sumptuous living. (Scholars have found that he had a total of 40 mistresses.) In 1846, he had built a country house outside Paris at

in ''Encyclopedia of American Poetry: The Nineteenth Century'', ed. by Eric L. Haralson, pp. 294–296 (1998) () Along with

On 5 December 1870, Dumas died at the age of 68 of natural causes, possibly a heart attack. At his death in December 1870, Dumas was buried at his birthplace of

On 5 December 1870, Dumas died at the age of 68 of natural causes, possibly a heart attack. At his death in December 1870, Dumas was buried at his birthplace of  In 1970, upon the centenary of his death, the

In 1970, upon the centenary of his death, the

accessed 4 November 2018. Researchers have continued to find Dumas works in archives, including the five-act play ''

''iForum'', University of Montreal, 30 September 2004, accessed 11 August 2012. Frank Wild Reed (1874–1953), a In June 2005, Dumas's last novel, '' The Knight of Sainte-Hermine'', was published in France featuring the Battle of Trafalgar. Dumas described a fictional character killing Lord Nelson (Nelson was shot and killed by an unknown sniper). Writing and publishing the novel serially in 1869, Dumas had nearly finished it before his death. It was the third part of the Sainte-Hermine trilogy.

Claude Schopp, a Dumas scholar, noticed a letter in an archive in 1990 that led him to discover the unfinished work. It took him years to research it, edit the completed portions, and decide how to treat the unfinished part. Schopp finally wrote the final two-and-a-half chapters, based on the author's notes, to complete the story. Published by Éditions Phébus, it sold 60,000 copies, making it a best seller. Translated into English, it was released in 2006 as ''

In June 2005, Dumas's last novel, '' The Knight of Sainte-Hermine'', was published in France featuring the Battle of Trafalgar. Dumas described a fictional character killing Lord Nelson (Nelson was shot and killed by an unknown sniper). Writing and publishing the novel serially in 1869, Dumas had nearly finished it before his death. It was the third part of the Sainte-Hermine trilogy.

Claude Schopp, a Dumas scholar, noticed a letter in an archive in 1990 that led him to discover the unfinished work. It took him years to research it, edit the completed portions, and decide how to treat the unfinished part. Schopp finally wrote the final two-and-a-half chapters, based on the author's notes, to complete the story. Published by Éditions Phébus, it sold 60,000 copies, making it a best seller. Translated into English, it was released in 2006 as ''

#The Dove - the sequel to Richelieu and His Rivals

#The Dove - the sequel to Richelieu and His Rivals

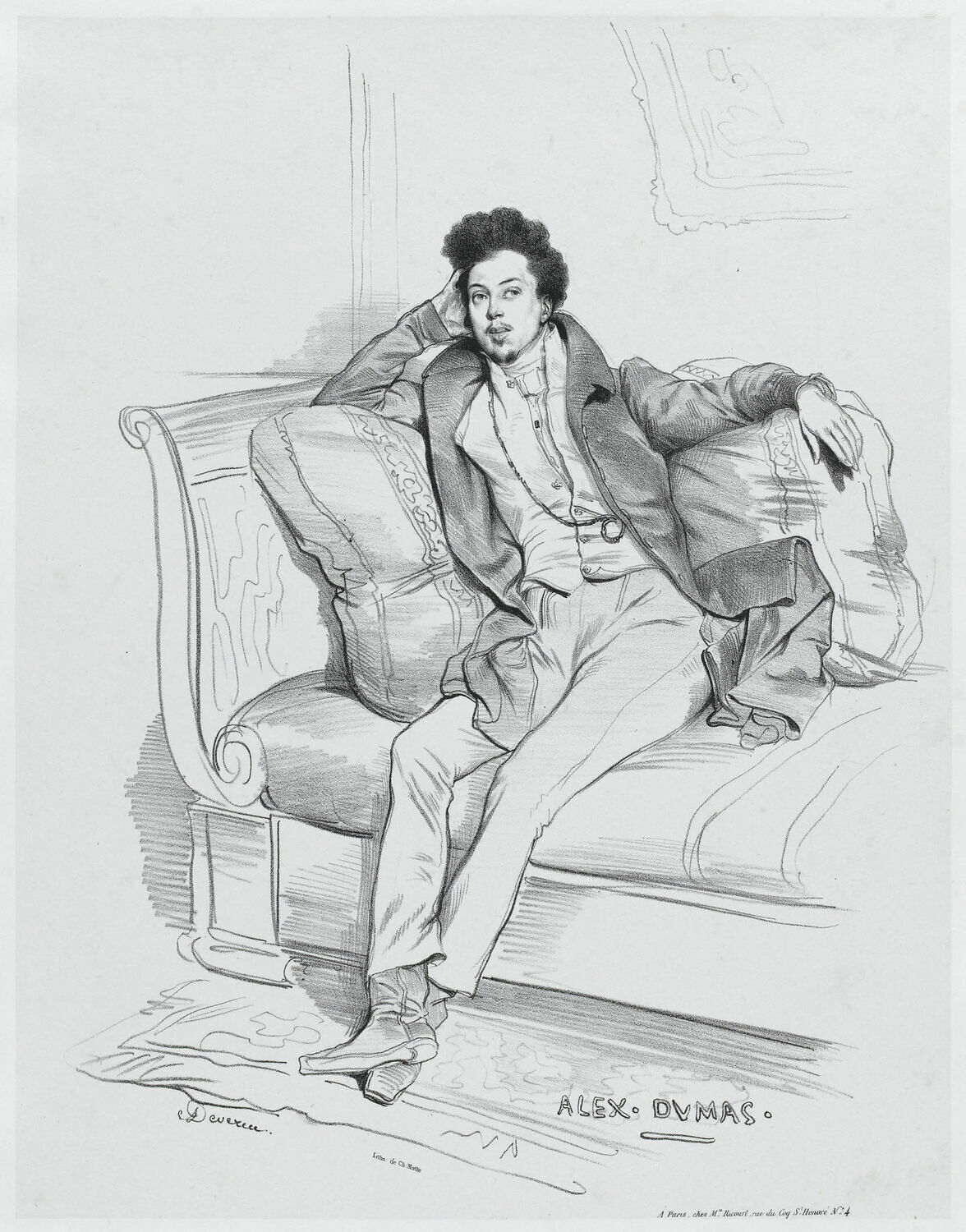

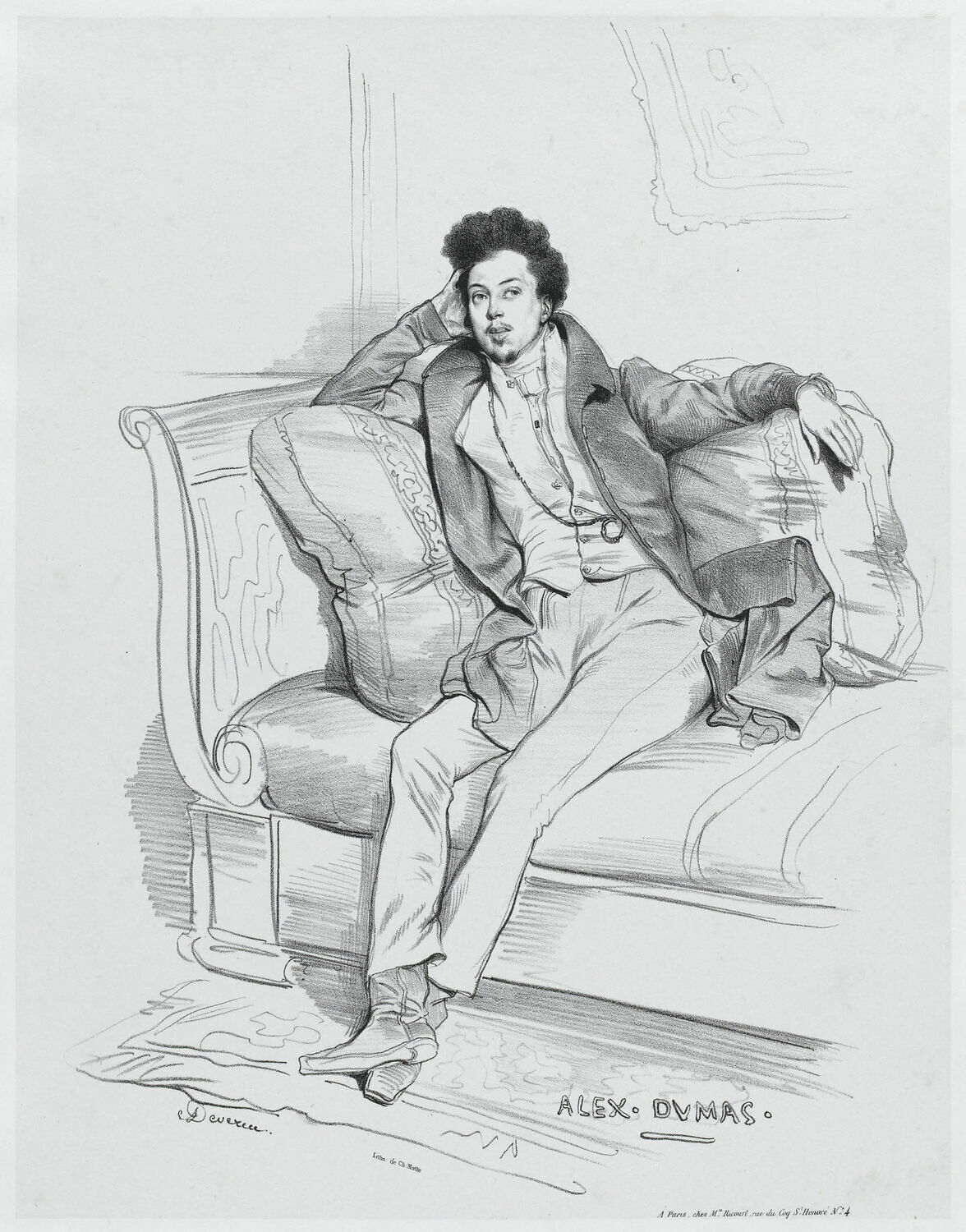

File:Alexandre Dumas 8.jpg, Dumas in about 1832

File:Alexandre Dumas 1.jpg, Dumas

File:Alexandre Dumas 7.jpg, Dumas in his library, by

''Herald Sun'': Lost Dumas play discovered

Lost Dumas novel hits bookshelves

Dumas' Works

text, concordances and frequency lists

The Alexandre Dumas père website

with a complete bibliography and notes about many of the works

* *

Alexandre Dumas et compagnie

: Freely downloadable works of Alexandre Dumas in PDF format (text mode)

Alexandre Dumas Collection

at the

Alejandro Dumas Vida y Obras

First Spanish Website about Alexandre Dumas and his works. * Rafferty, Terrence

ttps://www.nytimes.com/ ''The New York Times'' 20 August 2006 (a review of the new translation of ''The Three Musketeers'', ) * *

The Reed Dumas collection

held at Auckland Libraries

Alexandre Dumas' ''A Masked Ball'' audiobook with video at YouTube

Alexandre Dumas' ''A Masked Ball'' audiobook at Libsyn

* posthumous article i

November 17, 1883 {{DEFAULTSORT:Dumas, Alexandre 1802 births 1870 deaths People from Aisne French people of Haitian descent 19th-century French novelists 19th-century French dramatists and playwrights French historical novelists French fantasy writers French food writers French Freemasons French writers exiled in Belgium French memoirists French Roman Catholics Writers from Hauts-de-France Writers about Russia Burials at the Panthéon, Paris 19th-century memoirists Dumas family

French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

for 'father', to distinguish him from his son Alexandre Dumas fils

Alexandre Dumas (; 27 July 1824 – 27 November 1895) was a French author and playwright, best known for the romantic novel '' La Dame aux Camélias'' (''The Lady of the Camellias''), published in 1848, which was adapted into Giuseppe Verdi' ...

), was a French writer. His works have been translated into many languages and he is one of the most widely read French authors. Many of his historical novels of adventure were originally published as serials, including ''The Count of Monte Cristo

''The Count of Monte Cristo'' (french: Le Comte de Monte-Cristo) is an adventure novel written by French author Alexandre Dumas (''père'') completed in 1844. It is one of the author's more popular works, along with '' The Three Musketeers''. L ...

'', '' The Three Musketeers'', '' Twenty Years After'' and '' The Vicomte of Bragelonne: Ten Years Later''. His novels have been adapted since the early twentieth century into nearly 200 films.

Prolific in several genres, Dumas began his career by writing plays, which were successfully produced from the first. He also wrote numerous magazine articles

Article often refers to:

* Article (grammar), a grammatical element used to indicate definiteness or indefiniteness

* Article (publishing), a piece of nonfictional prose that is an independent part of a publication

Article may also refer to:

...

and travel books; his published works totalled 100,000 pages. In the 1840s, Dumas founded the Théâtre Historique in Paris.

His father, General Thomas-Alexandre Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie, was born in the French colony of Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1804. The name derives from the Spanish main city in the island, Santo Domingo, which came to ref ...

(present-day Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

) to Alexandre Antoine Davy de la Pailleterie, a French nobleman, and Marie-Cessette Dumas, an African slave. At age 14, Thomas-Alexandre was taken by his father to France, where he was educated in a military academy and entered the military for what became an illustrious career.

Dumas's father's aristocratic rank helped young Alexandre acquire work with Louis-Philippe, Duke of Orléans, then as a writer, a career which led to early success. Decades later, after the election of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte in 1851, Dumas fell from favour and left France for Belgium, where he stayed for several years, then moved to Russia for a few years before going to Italy. In 1861, he founded and published the newspaper ''L'Indépendent'', which supported Italian unification

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

, before returning to Paris in 1864.

Though married, in the tradition of Frenchmen of higher social class, Dumas had numerous affairs (allegedly as many as 40). He was known to have had at least four illegitimate children, although twentieth-century scholars believe it was seven. He acknowledged and assisted his son, Alexandre Dumas

Alexandre Dumas (, ; ; born Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie (), 24 July 1802 – 5 December 1870), also known as Alexandre Dumas père (where '' '' is French for 'father', to distinguish him from his son Alexandre Dumas fils), was a French writer. ...

, to become a successful novelist and playwright. They are known as Alexandre Dumas ('father') and Alexandre Dumas ('son'). Among his affairs, in 1866, Dumas had one with Adah Isaacs Menken

Adah Isaacs Menken (June 15, 1835August 10, 1868) was an American actress, painter and poet, and was the highest earning actress of her time.Palmer, Pamela Lynn"Adah Isaacs Menken" ''Handbook of Texas Online,'' published by the Texas State Histor ...

, an American actress who was less than half his age and at the height of her career.

The English playwright Watts Phillips

Watts Phillips (16 November 1825 – 2 December 1874) was an English illustrator, novelist and playwright best known for his play ''The Dead Heart'', which served as a model for Charles Dickens' '' A Tale of Two Cities''.

In a memoir, his sister ...

, who knew Dumas in his later life, described him as "the most generous, large-hearted being in the world. He also was the most delightfully amusing and egotistical creature on the face of the earth. His tongue was like a windmill – once set in motion, you never knew when he would stop, especially if the theme was himself."

Early life

Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie (later known as Alexandre Dumas) was born in 1802 in

Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie (later known as Alexandre Dumas) was born in 1802 in Villers-Cotterêts

Villers-Cotterêts () is a commune in the Aisne department in Hauts-de-France, France. It is notable as the signing-place in 1539 of the '' Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts'' discontinuing the use of Latin in official French documents, and as ...

in the department of Aisne, in Picardy

Picardy (; Picard and french: Picardie, , ) is a historical territory and a former administrative region of France. Since 1 January 2016, it has been part of the new region of Hauts-de-France. It is located in the northern part of France.

Hist ...

, France. He had two older sisters, Marie-Alexandrine (born 1794) and Louise-Alexandrine (1796–1797). Their parents were Marie-Louise Élisabeth Labouret, the daughter of an innkeeper, and Thomas-Alexandre Dumas.

Thomas-Alexandre had been born in the French colony of Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1804. The name derives from the Spanish main city in the island, Santo Domingo, which came to ref ...

(now Haiti), the mixed-race

Mixed race people are people of more than one race or ethnicity. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mixed race people in a variety of contexts, including ''multiethnic'', ''polyethnic'', occasionally ''bi-eth ...

, natural son of the marquis Alexandre Antoine Davy de la Pailleterie (Antoine), a French nobleman

The French nobility (french: la noblesse française) was a privileged social class in France from the Middle Ages until its abolition on June 23, 1790 during the French Revolution.

From 1808 to 1815 during the First Empire the Emperor Napol ...

and ''général commissaire'' in the artillery of the colony, and Marie-Cessette Dumas, an enslaved woman of Afro-Caribbean

Afro-Caribbean people or African Caribbean are Caribbean people who trace their full or partial ancestry to Sub-Saharan Africa. The majority of the modern African-Caribbeans descend from Africans taken as slaves to colonial Caribbean via the ...

ancestry. The two extant primary documents that state a racial identity for Marie-Cessette Dumas refer to her as a "négresse

Négresse is a mountain of Savoie, France. It lies in the Bauges range. It has an elevation of 1,720 metres above sea level.

Mountains of the Alps

Mountains of Savoie

{{Savoie-geo-stub ...

" (a black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white ha ...

woman) as opposed to a " mulâtresse" (a woman of visible mixed race).Letter from M. de Chauvinault, former royal prosecutor in Jérémie, Saint Domingue, to the Count de Maulde, 3 June 1776, privately held by Gilles Henry. Note: It says Dumas's father (then known as Antoine de l’Isle) “bought from a certain Monsieur de Mirribielle a negress named Cesette at an exorbitant price,” then, after living with her for some years, “sold... the negress Cezette” along with her two daughters "to a... baron from Nantes." Original French: "il achetais d’un certain Monsieur de Mirribielle une negresse nommée Cesette à un prix exhorbitant"; "qu’il a vendu à son depart avec les negres cupidon, la negresse cezette et les enfants à un sr barron originaire de nantes." (The spelling of her name varies within the letter.)Judgment in a dispute between Alexandre Dumas (named as Thomas Rethoré) and his father’s widow, Marie Retou Davy de la Pailleterie, Archives Nationale de France, LX465. His mother's name is Marie-Cesette Dumas (spelled "Cezette") and referred to as “Marie Cezette, negress, mother of Mr. Rethoré” (“Marie Cezette negresse mere dud. udit Udit is an Indian masculine given name that may refer to:

*Udit Narayan, Bollywood playback singer

*Udit Narayan (politician) (born 1960), Fijian politician of Indian descent

*Udit Narayan Singh (1770–1835), Indian monarch

*Udit Patel (born 1984 ...

S. Rethoré”) It is not known whether Marie-Cessette was born in Saint-Domingue or in Africa, nor is it known from which African people her ancestors came. What is known is that, sometime after becoming estranged from his brothers, Antoine purchased Marie-Cessette and her daughter (by a previous relationship) for "an exorbitant amount" and made Marie-Cessette his concubine. Thomas-Alexandre was the only son born to them, but two or three daughters were also born, of whom two daughters survived until their father sold them in 1775.

In 1775, following the death of both his brothers, Antoine left Saint-Domingue for France in order to claim the family estates and the title of Marquis. Shortly before his departure, he sold his long-time concubine Marie-Cessette and two of his own daughters born to her (Adolphe and Jeanette), as also Marie-Cessette oldest daughter Marie-Rose (whose father was a different man) to a Baron who had recently came from Nantes

Nantes (, , ; Gallo: or ; ) is a city in Loire-Atlantique on the Loire, from the Atlantic coast. The city is the sixth largest in France, with a population of 314,138 in Nantes proper and a metropolitan area of nearly 1 million inhabit ...

to settle in Saint Domingue. Antoine however retained ownership of Thomas-Alexandre (his only natural son) and took the boy with him to France. In that country, Thomas-Alexandre received his freedom and a sparse education at a military school, adequate to enable him to join the French army, there being no question of the mixed-race boy being accepted as his father's heir. Thomas-Alexandre did well in the Army and was promoted to general by the age of 31, the first soldier of Afro-Antilles origin to reach that rank in the French army.

The family surname was never bestowed upon Thomas-Alexandre, who therefore used "Dumas" as his surname. This is assumed to have been his mother's surname, but in fact, the surname "Dumas" occurs only once in connection with Marie-Cessette, and that happens in Europe, when Thomas-Alexandre states, while applying for a marriage license, that his mother's name was "Marie-Cessette Dumas." Some scholars have suggested that Thomas-Alexandre devised the surname "Dumas" for himself when he felt the need for one, and that he attributed it to his mother when convenient. "Dumas" means "of the farm" (''du mas''), perhaps signifying only that Marie-Cessette belonged to the farm property.

Career

While working for Louis-Philippe, Dumas began writing articles for magazines and plays for the theatre. As an adult, he used his slave grandmother's surname of Dumas, as his father had done as an adult. His first play, ''Henry III and His Courts'', produced in 1829 when he was 27 years old, met with acclaim. The next year, his second play, ''Christine'', was equally popular. These successes gave him sufficient income to write full-time.

In 1830, Dumas participated in the

While working for Louis-Philippe, Dumas began writing articles for magazines and plays for the theatre. As an adult, he used his slave grandmother's surname of Dumas, as his father had done as an adult. His first play, ''Henry III and His Courts'', produced in 1829 when he was 27 years old, met with acclaim. The next year, his second play, ''Christine'', was equally popular. These successes gave him sufficient income to write full-time.

In 1830, Dumas participated in the Revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

that ousted Charles X

Charles X (born Charles Philippe, Count of Artois; 9 October 1757 – 6 November 1836) was King of France from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830. An uncle of the uncrowned Louis XVII and younger brother to reigning kings Louis XVI and L ...

and replaced him with Dumas's former employer, the Duke of Orléans

Duke of Orléans (french: Duc d'Orléans) was a French royal title usually granted by the King of France to one of his close relatives (usually a younger brother or son), or otherwise inherited through the male line. First created in 1344 by King ...

, who ruled as Louis-Philippe, the Citizen King. Until the mid-1830s, life in France remained unsettled, with sporadic riots by disgruntled Republicans and impoverished urban workers seeking change. As life slowly returned to normal, the nation began to industrialise. An improving economy combined with the end of press censorship made the times rewarding for Alexandre Dumas's literary skills.

After writing additional successful plays, Dumas switched to writing novels. Although attracted to an extravagant lifestyle and always spending more than he earned, Dumas proved to be an astute marketer. As newspapers were publishing many serial novels. His first serial novel was ''La Comtesse de Salisbury; Édouard III'' (July-September 1836). In 1838, Dumas rewrote one of his plays as a successful serial novel, ''Le Capitaine Paul''. He founded a production studio, staffed with writers who turned out hundreds of stories, all subject to his personal direction, editing, and additions. From 1839 to 1841, Dumas, with the assistance of several friends, compiled ''Celebrated Crimes'', an eight-volume collection of essays on famous criminals and crimes from European history. He featured Beatrice Cenci, Martin Guerre

Martin Guerre, a French peasant of the 16th century, was at the centre of a famous case of imposture. Several years after Martin Guerre had left his wife, child and village, a man claiming to be him appeared. He lived with Guerre's wife and s ...

, Cesare and Lucrezia Borgia, as well as more recent events and criminals, including the cases of the alleged murderers Karl Ludwig Sand

Karl Ludwig Sand (Wunsiedel, Upper Franconia (then in Prussia), 5 October 1795 – Mannheim, 20 May 1820) was a German university student and member of a liberal Burschenschaft (student association). He was executed in 1820 for the murder of the ...

and Antoine François Desrues, who were executed

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the State (polity), state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to ...

. Dumas collaborated with Augustin Grisier, his fencing

Fencing is a group of three related combat sports. The three disciplines in modern fencing are the foil, the épée, and the sabre (also ''saber''); winning points are made through the weapon's contact with an opponent. A fourth discipline, ...

master, in his 1840 novel, ''The Fencing Master *''The Fencing Master'' may also refer to: The Fencing Master (Dumas novel), a nineteenth century novel by Alexandre Dumas

''The Fencing Master'' (1988) is a novel by Arturo Pérez-Reverte set in Spain at the middle of the 19th century. Amid the p ...

''. The story is written as Grisier's account of how he came to witness the events of the Decembrist revolt

The Decembrist Revolt ( ru , Восстание декабристов, translit = Vosstaniye dekabristov , translation = Uprising of the Decembrists) took place in Russia on , during the interregnum following the sudden death of Emperor Al ...

in Russia. The novel was eventually banned in Russia by Czar Nicholas I, and Dumas was prohibited from visiting the country until after the Czar's death. Dumas refers to Grisier with great respect in ''The Count of Monte Cristo

''The Count of Monte Cristo'' (french: Le Comte de Monte-Cristo) is an adventure novel written by French author Alexandre Dumas (''père'') completed in 1844. It is one of the author's more popular works, along with '' The Three Musketeers''. L ...

'', '' The Corsican Brothers'', and in his memoirs.

Dumas depended on numerous assistants and collaborators, of whom Auguste Maquet was the best known. It was not until the late twentieth century that his role was fully understood. Dumas wrote the short novel ''Georges Georges may refer to:

Places

*Georges River, New South Wales, Australia

*Georges Quay (Dublin)

* Georges Township, Fayette County, Pennsylvania

Other uses

* Georges (name)

* ''Georges'' (novel), a novel by Alexandre Dumas

* "Georges" (song), a 19 ...

'' (1843), which uses ideas and plots later repeated in ''The Count of Monte Cristo''. Maquet took Dumas to court to try to get authorial recognition and a higher rate of payment for his work. He was successful in getting more money, but not a by-line.

Le Port-Marly

Le Port-Marly () is a commune in the outer western suburbs of Paris, France. It is located in the Yvelines department

Department may refer to:

* Departmentalization, division of a larger organization into parts with specific responsibility

...

, the large Château de Monte-Cristo, with an additional building for his writing studio. It was often filled with strangers and acquaintances who stayed for lengthy visits and took advantage of his generosity. Two years later, faced with financial difficulties, he sold the entire property.

Dumas wrote in a wide variety of genres and published a total of 100,000 pages in his lifetime. He also made use of his experience, writing travel books after taking journeys, including those motivated by reasons other than pleasure. Dumas travelled to Spain, Italy, Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG),, is a country in Central Europe. It is the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany lies between the Baltic and North Sea to the north and the Alps to the sou ...

, England and French Algeria

French Algeria (french: Alger to 1839, then afterwards; unofficially , ar, الجزائر المستعمرة), also known as Colonial Algeria, was the period of French colonisation of Algeria. French rule in the region began in 1830 with the ...

. After King Louis-Philippe was ousted in a revolt, Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte was elected president. As Bonaparte disapproved of the author, Dumas fled in 1851 to Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

, Belgium, which was also an effort to escape his creditors. In about 1859, he moved to Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eigh ...

, where French was the second language of the elite and his writings were enormously popular. Dumas spent two years in Russia and visited St. Petersburg, Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

, Kazan

Kazan ( ; rus, Казань, p=kɐˈzanʲ; tt-Cyrl, Казан, ''Qazan'', IPA: ɑzan is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Tatarstan in Russia. The city lies at the confluence of the Volga and the Kazanka rivers, covering ...

, Astrakhan

Astrakhan ( rus, Астрахань, p=ˈastrəxənʲ) is the largest city and administrative centre of Astrakhan Oblast in Southern Russia. The city lies on two banks of the Volga, in the upper part of the Volga Delta, on eleven islands of ...

, Baku, and Tbilisi

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), is the capital and the largest city of Georgia, lying on the banks of the Kura River with a population of approximately 1.5 million p ...

, before leaving to seek different adventures. He published travel books about Russia.

In March 1861, the kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia was proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to an institutional referendum to abandon the monarchy and ...

was proclaimed, with Victor Emmanuel II as its king. Dumas travelled there and for the next three years participated in the movement for Italian unification

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

. He founded and led a newspaper, ''Indipendente''. While there, he befriended Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as ''Gioxeppe Gaibado''. In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as ''Jousé'' or ''Josep''. 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, patr ...

, whom he had long admired and with whom he shared a commitment to liberal republican principles as well as membership within Freemasonry

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

. Returning to Paris in 1864, he published travel books about Italy.

Despite Dumas's aristocratic background and personal success, he had to deal with discrimination related to his mixed-race ancestry. In 1843, he wrote a short novel, ''Georges Georges may refer to:

Places

*Georges River, New South Wales, Australia

*Georges Quay (Dublin)

* Georges Township, Fayette County, Pennsylvania

Other uses

* Georges (name)

* ''Georges'' (novel), a novel by Alexandre Dumas

* "Georges" (song), a 19 ...

'', that addressed some of the issues of race and the effects of colonialism. His response to a man who insulted him about his partial African ancestry has become famous. Dumas said:

Personal life

On 1 February 1840, Dumas married actress Ida Ferrier (born Marguerite-Joséphine Ferrand) (1811–1859). They did not have any children together. Dumas had numerous liaisons with other women; the scholar Claude Schopp lists nearly 40 mistresses. He is known to have fathered at least four children by them: * Alexandre Dumas, (1824–1895), son of Marie-Laure-Catherine Labay (1794–1868), a dressmaker. He became a successful novelist and playwright. * Marie-Alexandrine Dumas (1831–1878), daughter of Belle Krelsamer (1803–1875), an actress. * Henry Bauër (1851–1915), son of Anna Bauër, a German of Jewish faith, wife of Karl-Anton Bauër, an Austrian commercial agent living in Paris. * Micaëlla-Clélie-Josepha-Élisabeth Cordier (born 1860), daughter of Emélie Cordier, an actress. About 1866, Dumas had an affair withAdah Isaacs Menken

Adah Isaacs Menken (June 15, 1835August 10, 1868) was an American actress, painter and poet, and was the highest earning actress of her time.Palmer, Pamela Lynn"Adah Isaacs Menken" ''Handbook of Texas Online,'' published by the Texas State Histor ...

, a well-known American actress. She had performed her sensational role in ''Mazeppa Mazepa or Mazeppa is the surname of Ivan Mazepa, a Ukrainian hetman made famous worldwide by a poem by Lord Byron. It may refer to:

Artistic works Poems

* "Mazeppa" (poem) (1819), a dramatic poem by Lord Byron

* "Mazeppa", a poem by Victor Hugo, ...

'' in London. In Paris, she had a sold-out run of '' Les Pirates de la Savanne'' and was at the peak of her success.Dorsey Kleitz, "Adah Isaacs Menken"in ''Encyclopedia of American Poetry: The Nineteenth Century'', ed. by Eric L. Haralson, pp. 294–296 (1998) () Along with

Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

, Charles Baudelaire

Charles Pierre Baudelaire (, ; ; 9 April 1821 – 31 August 1867) was a French poet who also produced notable work as an essayist and art critic. His poems exhibit mastery in the handling of rhyme and rhythm, contain an exoticism inherited ...

, Gérard de Nerval, Eugène Delacroix

Ferdinand Victor Eugène Delacroix ( , ; 26 April 1798 – 13 August 1863) was a French Romantic artist regarded from the outset of his career as the leader of the French Romantic school.Noon, Patrick, et al., ''Crossing the Channel: British ...

and Honoré de Balzac

Honoré de Balzac ( , more commonly , ; born Honoré Balzac;Jean-Louis Dega, La vie prodigieuse de Bernard-François Balssa, père d'Honoré de Balzac : Aux sources historiques de La Comédie humaine, Rodez, Subervie, 1998, 665 p. 20 May 179 ...

, Dumas was a member of the Club des Hashischins

The Club des Hashischins (sometimes also spelled Club des Hashishins or Club des Hachichins, "Club of the Hashish-Eaters") was a Parisian group dedicated to the exploration of drug-induced experiences, notably with hashish.Levinthal, C. F. (2012) ...

, which met monthly to take hashish

Hashish ( ar, حشيش, ()), also known as hash, "dry herb, hay" is a cannabis (drug), drug made by compressing and processing parts of the cannabis plant, typically focusing on flowering buds (female flowers) containing the most trichomes. Eu ...

at a hotel in Paris. Dumas's ''The Count of Monte Cristo

''The Count of Monte Cristo'' (french: Le Comte de Monte-Cristo) is an adventure novel written by French author Alexandre Dumas (''père'') completed in 1844. It is one of the author's more popular works, along with '' The Three Musketeers''. L ...

'' contains several references to hashish.

Death and legacy

On 5 December 1870, Dumas died at the age of 68 of natural causes, possibly a heart attack. At his death in December 1870, Dumas was buried at his birthplace of

On 5 December 1870, Dumas died at the age of 68 of natural causes, possibly a heart attack. At his death in December 1870, Dumas was buried at his birthplace of Villers-Cotterêts

Villers-Cotterêts () is a commune in the Aisne department in Hauts-de-France, France. It is notable as the signing-place in 1539 of the '' Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts'' discontinuing the use of Latin in official French documents, and as ...

in the department of Aisne. His death was overshadowed by the Franco-Prussian War. Changing literary fashions decreased his popularity. In the late twentieth century, scholars such as Reginald Hamel and Claude Schopp have caused a critical reappraisal and new appreciation of his art, as well as finding lost works.

In 1970, upon the centenary of his death, the

In 1970, upon the centenary of his death, the Paris Métro

The Paris Métro (french: Métro de Paris ; short for Métropolitain ) is a rapid transit system in the Paris metropolitan area, France. A symbol of the city, it is known for its density within the capital's territorial limits, uniform architec ...

named a station in his honour. His country home outside Paris, the Château de Monte-Cristo, has been restored and is open to the public as a museum.Château de Monte-Cristo Museum Opening Hoursaccessed 4 November 2018. Researchers have continued to find Dumas works in archives, including the five-act play ''

The Gold Thieves

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the m ...

,'' found in 2002 by the scholar in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France

The Bibliothèque nationale de France (, 'National Library of France'; BnF) is the national library of France, located in Paris on two main sites known respectively as ''Richelieu'' and ''François-Mitterrand''. It is the national reposito ...

. It was published in France in 2004 by Honoré-Champion.French Studies: "Quebecer discovers an unpublished manuscript by Alexandre Dumas"''iForum'', University of Montreal, 30 September 2004, accessed 11 August 2012. Frank Wild Reed (1874–1953), a

New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 List of islands of New Zealand, smaller islands. It is the ...

pharmacist who never visited France, amassed the greatest collection of books and manuscripts relating to Dumas outside France. The collection contains about 3,350 volumes, including some 2,000 sheets in Dumas's handwriting and dozens of French, Belgian and English first editions. The collection was donated to Auckland Libraries after his death. Reed wrote the most comprehensive bibliography of Dumas.

In 2002, for the bicentenary of Dumas's birth, French President Jacques Chirac

Jacques René Chirac (, , ; 29 November 193226 September 2019) was a French politician who served as President of France from 1995 to 2007. Chirac was previously Prime Minister of France from 1974 to 1976 and from 1986 to 1988, as well as ...

held a ceremony honouring the author by having his ashes re-interred at the mausoleum of the Panthéon of Paris, where many French luminaries were buried. When Chirac ordered the transfer to the mausoleum, villagers in Dumas's hometown of Villers-Cotterets were initially opposed, arguing that Dumas laid out in his memoirs that he wanted to be buried there. The village eventually bowed to the government's decision, and Dumas's body was exhumed from its cemetery and put into a new coffin in preparation for the transfer. The proceedings were televised: the new coffin was draped in a blue velvet cloth and carried on a caisson flanked by four mounted Republican Guards costumed as the four Musketeer

A musketeer (french: mousquetaire) was a type of soldier equipped with a musket. Musketeers were an important part of early modern warfare particularly in Europe as they normally comprised the majority of their infantry. The musketeer was a pre ...

s. It was transported through Paris to the Panthéon. In his speech, Chirac said:

With you, we were D'Artagnan, Monte Cristo, or Balsamo, riding along the roads of France, touring battlefields, visiting palaces and castles—with you, we dream.Chirac acknowledged the racism that had existed in France and said that the re-interment in the Pantheon had been a way of correcting that wrong, as Alexandre Dumas was enshrined alongside fellow great authors

Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

and Émile Zola

Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola (, also , ; 2 April 184029 September 1902) was a French novelist, journalist, playwright, the best-known practitioner of the literary school of naturalism, and an important contributor to the development of ...

. Chirac noted that although France has produced many great writers, none has been so widely read as Dumas. His novels have been translated into nearly 100 languages. In addition, they have inspired more than 200 motion pictures.

In June 2005, Dumas's last novel, '' The Knight of Sainte-Hermine'', was published in France featuring the Battle of Trafalgar. Dumas described a fictional character killing Lord Nelson (Nelson was shot and killed by an unknown sniper). Writing and publishing the novel serially in 1869, Dumas had nearly finished it before his death. It was the third part of the Sainte-Hermine trilogy.

Claude Schopp, a Dumas scholar, noticed a letter in an archive in 1990 that led him to discover the unfinished work. It took him years to research it, edit the completed portions, and decide how to treat the unfinished part. Schopp finally wrote the final two-and-a-half chapters, based on the author's notes, to complete the story. Published by Éditions Phébus, it sold 60,000 copies, making it a best seller. Translated into English, it was released in 2006 as ''

In June 2005, Dumas's last novel, '' The Knight of Sainte-Hermine'', was published in France featuring the Battle of Trafalgar. Dumas described a fictional character killing Lord Nelson (Nelson was shot and killed by an unknown sniper). Writing and publishing the novel serially in 1869, Dumas had nearly finished it before his death. It was the third part of the Sainte-Hermine trilogy.

Claude Schopp, a Dumas scholar, noticed a letter in an archive in 1990 that led him to discover the unfinished work. It took him years to research it, edit the completed portions, and decide how to treat the unfinished part. Schopp finally wrote the final two-and-a-half chapters, based on the author's notes, to complete the story. Published by Éditions Phébus, it sold 60,000 copies, making it a best seller. Translated into English, it was released in 2006 as ''The Last Cavalier

''The Knight of Sainte-Hermine'' (published in France in 2005 under the title ''Le Chevalier de Sainte-Hermine'', and translated to English under the title ''The Last Cavalier'') is an unfinished historical novel by Alexandre Dumas, believed to ...

,'' and has been translated into other languages.

Schopp has since found additional material related to the Sainte-Hermine saga. Schopp combined them to publish the sequel ''Le Salut de l'Empire'' in 2008.

Works

Fiction

Christian history

* ''Acté of Corinth; or, The convert of St. Paul. a tale of Greece and Rome.'' (1839), a novel about Rome, Nero, and early Christianity. * ''Isaac Laquedem

The Wandering Jew is a mythical immortal man whose legend began to spread in Europe in the 13th century. In the original legend, a Jew who taunted Jesus on the way to the Crucifixion was then cursed to walk the Earth until the Second Coming. Th ...

'' (1852–53, incomplete)

Adventure

Alexandre Dumas wrote numerous stories and historical chronicles of adventure. They included the following: * ''The Countess of Salisbury'' (''La Comtesse de Salisbury; Édouard III'', 1836), his first serial novel published in volume in 1839. * ''Captain Paul'' (''Le Capitaine Paul'', 1838) * ''Othon the Archer'' (''Othon l'archer'' 1840) * '' Captain Pamphile'' (''Le Capitaine Pamphile'', 1839) * ''The Fencing Master *''The Fencing Master'' may also refer to: The Fencing Master (Dumas novel), a nineteenth century novel by Alexandre Dumas

''The Fencing Master'' (1988) is a novel by Arturo Pérez-Reverte set in Spain at the middle of the 19th century. Amid the p ...

'' (''Le Maître d'armes'', 1840)

* ''Castle Eppstein; The Spectre Mother'' (''Chateau d'Eppstein; Albine'', 1843)

* '' Amaury'' (1843)

* '' The Corsican Brothers'' (''Les Frères Corses'', 1844)

* '' The Black Tulip'' (''La Tulipe noire'', 1850)

* ''Olympe de Cleves'' (1851–52)

* ''Catherine Blum'' (1853–54)

* ''The Mohicans of Paris'' (', 1854)

* ''Salvator'' (''Salvator. Suite et fin des Mohicans de Paris'', 1855–1859)

* ''The Last Vendee, or the She-Wolves of Machecoul'' (''Les louves de Machecoul'', 1859), a romance (not about werewolves).

* '' La Sanfelice'' (1864), set in Naples in 1800.

* ''Pietro Monaco, sua moglie Maria Oliverio ed i loro complici'', (1864), an appendix to ''Ciccilla'' by Peppino Curcio Peppino may refer to:

Given name:

* Peppino D'Agostino, Italian guitarist

*Peppino De Filippo (1903–1980), Italian actor

*Peppino di Capri (born 1939), Italian popular music singer, songwriter and pianist

*Peppino Gagliardi (born 1940), Itali ...

.

* ''The Prussian Terror'' (''La Terreur Prussienne'', 1867), set during the Seven Weeks' War.

Fantasy

* ''The Nutcracker'' (''Histoire d'un casse-noisette'', 1844): a revision of Hoffmann's story ''The Nutcracker and the Mouse King

"The Nutcracker and the Mouse King" (german: Nussknacker und Mausekönig) is a story written in 1816 by Prussian author E. T. A. Hoffmann, in which young Marie Stahlbaum's favorite Christmas toy, the Nutcracker, comes alive and, after defeati ...

'', later set by composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic music, Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer Music of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, whose music would make a lasting impressi ...

to music for a ballet also called ''The Nutcracker

''The Nutcracker'' ( rus, Щелкунчик, Shchelkunchik, links=no ) is an 1892 two-act ballet (""; russian: балет-феерия, link=no, ), originally choreographed by Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov with a score by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaiko ...

''.

* ''The Pale Lady'' (1849) A vampire tale about a Polish woman who is adored by two very different brothers.

* '' The Wolf Leader'' (''Le Meneur de loups'', 1857). One of the first werewolf

In folklore, a werewolf (), or occasionally lycanthrope (; ; uk, Вовкулака, Vovkulaka), is an individual that can shapeshift into a wolf (or, especially in modern film, a therianthropic hybrid wolf-like creature), either purposel ...

novels ever written.

In addition, Dumas wrote many series of novels:

Monte Cristo

# ''Georges Georges may refer to:

Places

*Georges River, New South Wales, Australia

*Georges Quay (Dublin)

* Georges Township, Fayette County, Pennsylvania

Other uses

* Georges (name)

* ''Georges'' (novel), a novel by Alexandre Dumas

* "Georges" (song), a 19 ...

'' (1843): The protagonist of this novel is a man of mixed race, a rare allusion to Dumas's own African ancestry.

# ''The Count of Monte Cristo

''The Count of Monte Cristo'' (french: Le Comte de Monte-Cristo) is an adventure novel written by French author Alexandre Dumas (''père'') completed in 1844. It is one of the author's more popular works, along with '' The Three Musketeers''. L ...

'' (''Le Comte de Monte-Cristo'', 1844–46)

Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached ...

# ''The Conspirators

In the English language, a conspirator is a party to a conspiracy. In a criminal conspiracy, each alleged party is a "co-conspirator".

Conspirator(s) may refer to:

Books

* ''The Conspirators'' (novel), 1843 French historical novel by Alexandre D ...

'' (''Le chevalier d'Harmental'', 1843) adapted by Paul Ferrier for an 1896 opéra comique

''Opéra comique'' (; plural: ''opéras comiques'') is a genre of French opera that contains spoken dialogue and arias. It emerged from the popular '' opéras comiques en vaudevilles'' of the Fair Theatres of St Germain and St Laurent (and to a l ...

by Messager.

# '' The Regent's Daughter'' (''Une Fille du régent'', 1845). Sequel to ''The Conspirators''.

''The D'Artagnan Romances''

'' The d'Artagnan Romances'': # '' The Three Musketeers'' (''Les Trois Mousquetaires'', 1844) # '' Twenty Years After'' (''Vingt ans après'', 1845) # '' The Vicomte de Bragelonne'', sometimes called ''Ten Years Later'' (''Le Vicomte de Bragelonne, ou Dix ans plus tard'', 1847). When published in English, it was usually split into three parts: ''The Vicomte de Bragelonne'', ''Louise de la Valliere'', and '' The Man in the Iron Mask'', of which the last part is the best known.=Related books

= # ''Louis XIV and His Century'' (''Louis XIV et son siècle'', 1844) # '' The Women's War'' (''La Guerre des Femmes'', 1845): follows Baron des Canolles, a naïve Gascon soldier who falls in love with two women. # ''The Count of Moret; The Red Sphinx; or, Richelieu and His Rivals'' (''Le Comte de Moret; Le Sphinx Rouge'', 1865–66) - #The Dove - the sequel to Richelieu and His Rivals

#The Dove - the sequel to Richelieu and His Rivals

The Valois romances

The Valois were the royal house of France from 1328 to 1589, and many Dumas romances cover their reign. Traditionally, the so-called "Valois Romances" are the three that portray the Reign of Queen Marguerite, the last of the Valois. Dumas, however, later wrote four more novels that cover this family and portray similar characters, starting with François orFrancis I Francis I or Francis the First may refer to:

* Francesco I Gonzaga (1366–1407)

* Francis I, Duke of Brittany (1414–1450), reigned 1442–1450

* Francis I of France (1494–1547), King of France, reigned 1515–1547

* Francis I, Duke of Saxe ...

, his son Henry II, and Marguerite and François II

Francis II (french: François II; 19 January 1544 – 5 December 1560) was King of France from 1559 to 1560. He was also King consort of Scotland as a result of his marriage to Mary, Queen of Scots, from 1558 until his death in 1560.

He ...

, sons of Henry II and Catherine de' Medici

Catherine de' Medici ( it, Caterina de' Medici, ; french: Catherine de Médicis, ; 13 April 1519 – 5 January 1589) was an Florentine noblewoman born into the Medici family. She was Queen of France from 1547 to 1559 by marriage to King ...

.

# '' La Reine Margot'', also published as ''Marguerite de Valois'' (1845)

# ''La Dame de Monsoreau

''La Dame de Monsoreau'' is a historical novel by Alexandre Dumas, père published in 1846. It owes its name to the counts who owned the famous château de Montsoreau. The novel is concerned with fraternal royal strife at the court of Henri III

...

'' (1846) (later adapted as a short story titled "Chicot the Jester")

# ''The Forty-Five Guardsmen

''The Forty-Five Guardsmen'' (''Les Quarante-cinq'' in French) is a historical novel by Alexandre Dumas, written between 1847 and 1848 in collaboration with Auguste Maquet. Set in 1585 and 1586 during the French Wars of Religion, it is the thi ...

'' (1847) (''Les Quarante-cinq'')

# '' Ascanio'' (1843). Written in collaboration with Paul Meurice, it is a romance of Francis I Francis I or Francis the First may refer to:

* Francesco I Gonzaga (1366–1407)

* Francis I, Duke of Brittany (1414–1450), reigned 1442–1450

* Francis I of France (1494–1547), King of France, reigned 1515–1547

* Francis I, Duke of Saxe ...

(1515–1547), but the main character is Italian artist Benvenuto Cellini. The opera '' Ascanio'' was based on this novel.

# '' The Two Dianas'' (''Les Deux Diane'', 1846), is a novel about Gabriel, comte de Montgomery, who mortally wounded King Henry II and was lover to his daughter, Diana de Castro. Although published under Dumas's name, it was wholly or mostly written by Paul Meurice.

# ''The Page of the Duke of Savoy

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things that are already or about to be mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in ...

'', (1855) is a sequel to ''The Two Dianas'' (1846), and it covers the struggle for supremacy between the Guises and Catherine de Médicis, the Florentine mother of the last three Valois kings of France (and wife of Henry II). The main character in this novel is Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy.

# ''The Horoscope: a romance of the reign of François II'' (1858), covers François II, who reigned for one year (1559–60) and died at the age of 16.

The Marie Antoinette romances

TheMarie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette Josèphe Jeanne (; ; née Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last queen of France before the French Revolution. She was born an archduchess of Austria, and was the penultimate child ...

romances comprise eight novels. The unabridged versions (normally 100 chapters or more) comprise only five books (numbers 1, 3, 4, 7 and 8); the short versions (50 chapters or less) number eight in total:

# ''Joseph Balsamo'' (''Mémoires d'un médecin: Joseph Balsamo'', 1846–48) (a.k.a. ''Memoirs of a Physician'', '' Cagliostro'', '' Madame Dubarry'', ''The Countess Dubarry'', or ''The Elixir of Life''). ''Joseph Balsamo'' is about 1000 pages long, and is usually published in two volumes in English translations: Vol 1. ''Joseph Balsamo'' and Vol 2. ''Memoirs of a Physician''. The long unabridged version includes the contents of book two, Andrée de Taverney; the short abridged versions usually are divided in ''Balsamo'' and ''Andrée de Taverney'' as completely different books.

# ''Andrée de Taverney'', or ''The Mesmerist's Victim''

# '' The Queen's Necklace'' (''Le Collier de la Reine'', (1849−1850)

# ''Ange Pitou'' (1853) (a.k.a. ''Storming the Bastille'' or ''Six Years Later''). From this book, there are also long unabridged versions which include the contents of book five, but there are many short versions that treat "The Hero of the People" as a separated volume.

# ''The Hero of the People''

# ''The Royal Life Guard or The Flight of the Royal Family.''

# ''The Countess de Charny'' (''La Comtesse de Charny'', 1853–1855). As with other books, there are long unabridged versions which include the contents of book six; but many short versions that leave contents in ''The Royal Life Guard'' as a separate volume.

# '' Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge'' (1845) (a.k.a. ''The Knight of the Red House'', or ''The Knight of Maison-Rouge'')

The Sainte-Hermine trilogy

:# ''The Companions of Jehu

''The Companions of Jehu'' (French: ''Les Compagnons de Jéhu'') is a historical adventure novel by the French writer Alexandre Dumas first published in 1857. It is inspired by the story of the Companions of Jehu, a group of Royalist vigilante ...

'' (''Les Compagnons de Jehu'', 1857)

:#''The Whites and the Blues

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things that are already or about to be mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in En ...

'' (''Les Blancs et les Bleus'', 1867)

:# '' The Knight of Sainte-Hermine'' (''Le Chevalier de Sainte-Hermine'', 1869). Dumas's last novel, unfinished at his death, was completed by scholar Claude Schopp and published in 2005. It was published in English in 2008 as ''The Last Cavalier''.

Robin Hood

# ''The Prince of Thieves'' (''Le Prince des voleurs'', 1872, posthumously). AboutRobin Hood

Robin Hood is a legendary heroic outlaw originally depicted in English folklore and subsequently featured in literature and film. According to legend, he was a highly skilled archer and swordsman. In some versions of the legend, he is de ...

(and the inspiration for the 1948 film '' The Prince of Thieves'').

# ''Robin Hood the Outlaw'' (''Robin Hood le proscrit'', 1873, posthumously). Sequel to ''Le Prince des voleurs''

Drama

Although best known now as a novelist, Dumas first earned fame as a dramatist. His ''Henri III et sa cour'' (1829) was the first of the greatRomantic

Romantic may refer to:

Genres and eras

* The Romantic era, an artistic, literary, musical and intellectual movement of the 18th and 19th centuries

** Romantic music, of that era

** Romantic poetry, of that era

** Romanticism in science, of that e ...

historical dramas produced on the Paris stage, preceding Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

's more famous ''Hernani Hernani may refer to:

*Hernani, Eastern Samar, a municipality in Eastern Samar, Philippines

*Hernani, Gipuzkoa, a town in Gipuzkoa, Basque Autonomous Community, Spain

* ''Hernani'' (drama), a Romantic drama by Victor Hugo

*Hernani CRE, a Spanish ru ...

'' (1830). Produced at the Comédie-Française

The Comédie-Française () or Théâtre-Français () is one of the few state theatre

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real ...

and starring the famous Mademoiselle Mars

Mademoiselle Mars (pseudonym of Anne Françoise Hyppolyte Boutet Salvetat; 9 February 1779 – 20 March 1847), French actress, was born in Paris, the natural daughter of the actor-author named Monvel (Jacques Marie Boutet) (1745–1812) and Jean ...

, Dumas's play was an enormous success and launched him on his career. It had fifty performances over the next year, extraordinary at the time. Dumas's works included:

* ''The Hunter and the Lover'' (1825)

* ''The Wedding and the Funeral'' (1826)

* ''Henry III and his court'' (1829)

* ''Christine – Stockholm, Fontainebleau, and Rome'' (1830)

* ''Napoleon Bonaparte or Thirty Years of the History of France'' (1831)

* ''Antony'' (1831)a drama with a contemporary Byronic herois considered the first non-historical Romantic drama. It starred Mars' great rival Marie Dorval.

* ''Charles VII at the Homes of His Great Vassals'' (''Charles VII chez ses grands vassaux'', 1831). This drama was adapted by the Russian composer César Cui

César Antonovich Cui ( rus, Це́зарь Анто́нович Кюи́, , ˈt͡sjezərʲ ɐnˈtonəvʲɪt͡ɕ kʲʊˈi, links=no, Ru-Tsezar-Antonovich-Kyui.ogg; french: Cesarius Benjaminus Cui, links=no, italic=no; 13 March 1918) was a Rus ...

for his opera '' The Saracen''.

* ''Teresa'' (1831)

* ''La Tour de Nesle'' (1832), a historical melodrama

* ''The Memories of Anthony'' (1835)

* ''The Chronicles of France: Isabel of Bavaria'' (1835)

* '' Kean'' (1836), based on the life of the notable late English actor Edmund Kean. Frédérick Lemaître

Antoine Louis Prosper "Frédérick" Lemaître (28 July 1800 – 26 January 1876) was a French actor and playwright, one of the most famous players on the celebrated Boulevard du Crime.

Biography

Lemaître, the son of an architect, was bo ...

played him in the production.

* ''Caligula'' (1837)

* ''Miss Belle-Isle'' (1837)

* ''The Young Ladies of Saint-Cyr'' (1843)

* ''The Youth of Louis XIV'' (1854)

* ''The Son of the Night – The Pirate'' (1856) (with Gérard de Nerval, Bernard Lopez, and Victor Sejour)

* ''The Gold Thieves

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the m ...

'' (after 1857): an unpublished five-act play. It was discovered in 2002 by the Canadian scholar Reginald Hamel, who was researching in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France

The Bibliothèque nationale de France (, 'National Library of France'; BnF) is the national library of France, located in Paris on two main sites known respectively as ''Richelieu'' and ''François-Mitterrand''. It is the national reposito ...

. The play was published in France in 2004 by Honoré-Champion. Hamel said that Dumas was inspired by a novel written in 1857 by his mistress Célèste de Mogador.

Dumas wrote many plays and adapted several of his novels as dramas. In the 1840s, he founded the Théâtre Historique, located on the Boulevard du Temple in Paris. The building was used after 1852 by the Opéra National

This is a glossary list of opera genres, giving alternative names.

"Opera" is an Italian word (short for "opera in musica"); it was not at first ''commonly'' used in Italy (or in other countries) to refer to the genre of particular works. Most ...

(established by Adolphe Adam in 1847). It was renamed the Théâtre Lyrique

The Théâtre Lyrique was one of four opera companies performing in Paris during the middle of the 19th century (the other three being the Opéra, the Opéra-Comique, and the Théâtre-Italien). The company was founded in 1847 as the Opér ...

in 1851.

Nonfiction

Dumas was a prolific writer of nonfiction. He wrote journal articles on politics and culture and books on French history. His lengthy ''Grand Dictionnaire de cuisine'' (''Great Dictionary of Cuisine'') was published posthumously in 1873. A combination of encyclopaedia and cookbook, it reflects Dumas's interests as both a gourmet and an expert cook. An abridged version (the ''Petit Dictionnaire de cuisine'', or ''Small Dictionary of Cuisine'') was published in 1883. He was also known for his travel writing. These books included: * ''Impressions de voyage: En Suisse'' (''Travel Impressions: In Switzerland'', 1834) * ''Une Année à Florence'' (''A Year inFlorence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

'', 1841)

* ''De Paris à Cadix'' (''From Paris to Cadiz'', 1847)

* ''Montevideo, ou une nouvelle Troie'', 1850 ('' The New Troy''), inspired by the Great Siege of Montevideo

The Great Siege of Montevideo ( es, Gran Sitio de Montevideo), named as ''Sitio Grande'' in Uruguayan historiography, was the siege suffered by the city of Montevideo between 1843 and 1851 during the Uruguayan Civil War.Walter Rela (1998). ...

* ''Le Journal de Madame Giovanni'' (''The Journal of Madame Giovanni'', 1856)

* ''Travel Impressions in the Kingdom of Napoli/Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

Trilogy'':

* ''Impressions of Travel in Sicily'' (''Le Speronare (Sicily – 1835)'', 1842

* ''Captain Arena'' (''Le Capitaine Arena (Italy – Aeolian Islands

The Aeolian Islands ( ; it, Isole Eolie ; scn, Ìsuli Eoli), sometimes referred to as the Lipari Islands or Lipari group ( , ) after their largest island, are a volcanic archipelago in the Tyrrhenian Sea north of Sicily, said to be named a ...

and Calabria – 1835)'', 1842

* ''Impressions of Travel in Naples'' (''Le Corricolo (Rome – Naples – 1833)'', 1843

* ''Travel Impressions in Russia – Le Caucase Original edition: Paris 1859''

* ''Adventures in Czarist Russia, or From Paris to Astrakhan

Astrakhan ( rus, Астрахань, p=ˈastrəxənʲ) is the largest city and administrative centre of Astrakhan Oblast in Southern Russia. The city lies on two banks of the Volga, in the upper part of the Volga Delta, on eleven islands of ...

'' (''Impressions de voyage: En Russie; De Paris à Astrakan: Nouvelles impressions de voyage (1858)'', 1859–1862

* ''Voyage to the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia (country), Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range ...

'' (''Le Caucase: Impressions de voyage; suite de En Russie (1859)'', 1858–1859

* ''The Bourbons of Naples'' ( it, I Borboni di Napoli, 1862) (7 volumes published by Italian newspaper ''L'Indipendente'', whose director was Dumas himself).

Dumas Society

French historian Alain Decaux founded the "Société des Amis d'Alexandre Dumas" (The Society of Friends of Alexandre Dumas) in 1971. its president is Claude Schopp. The purpose in creating this society was to preserve the Château de Monte-Cristo, where the society is currently located. The other objectives of the Society are to bring together fans of Dumas, to develop cultural activities of the Château de Monte-Cristo, and to collect books, manuscripts, autographs and other materials on Dumas.Tribute

On 28 August 2020,Google

Google LLC () is an American Multinational corporation, multinational technology company focusing on Search Engine, search engine technology, online advertising, cloud computing, software, computer software, quantum computing, e-commerce, ar ...

celebrated Dumas with a Google Doodle.

Images

Maurice Leloir

Maurice Leloir (1 November 1853 – 7 October 1940) was a French illustrator, watercolourist, draftsman, printmaker, writer and collector.

Biography

Leloir was the son, and pupil, of painter and watercolorist Héloïse Suzanne Colin, daughte ...

File:Alexandre Dumas 4.jpg, Dumas in 1860

File:DUMAS PERE.jpg, Dumas, cliché by Charles Reutlinger

File:Gill - Dumas Père.jpg, Dumas by Gill

File:Alexandre Dumas & Adah Isaacs Menken.jpg, Alexandre Dumas and Adah Isaacs Menken

Adah Isaacs Menken (June 15, 1835August 10, 1868) was an American actress, painter and poet, and was the highest earning actress of her time.Palmer, Pamela Lynn"Adah Isaacs Menken" ''Handbook of Texas Online,'' published by the Texas State Histor ...

, 1866

See also

* Illegitimacy in fiction * Afro European * Museum Alexandre DumasReferences

Sources

* * * * * * * * *External links

* * * * *''Herald Sun'': Lost Dumas play discovered

Lost Dumas novel hits bookshelves

Dumas' Works

text, concordances and frequency lists

The Alexandre Dumas père website

with a complete bibliography and notes about many of the works

* *

Alexandre Dumas et compagnie

: Freely downloadable works of Alexandre Dumas in PDF format (text mode)

Alexandre Dumas Collection

at the

Harry Ransom Center

The Harry Ransom Center (until 1983 the Humanities Research Center) is an archive, library and museum at the University of Texas at Austin, specializing in the collection of literary and cultural artifacts from the Americas and Europe for the pu ...

at the University of Texas at Austin

The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin, UT, or Texas) is a public research university in Austin, Texas. It was founded in 1883 and is the oldest institution in the University of Texas System. With 40,916 undergraduate students, 11,075 ...

Alejandro Dumas Vida y Obras

First Spanish Website about Alexandre Dumas and his works. * Rafferty, Terrence

ttps://www.nytimes.com/ ''The New York Times'' 20 August 2006 (a review of the new translation of ''The Three Musketeers'', ) * *

The Reed Dumas collection

held at Auckland Libraries

Alexandre Dumas' ''A Masked Ball'' audiobook with video at YouTube

Alexandre Dumas' ''A Masked Ball'' audiobook at Libsyn

* posthumous article i

November 17, 1883 {{DEFAULTSORT:Dumas, Alexandre 1802 births 1870 deaths People from Aisne French people of Haitian descent 19th-century French novelists 19th-century French dramatists and playwrights French historical novelists French fantasy writers French food writers French Freemasons French writers exiled in Belgium French memoirists French Roman Catholics Writers from Hauts-de-France Writers about Russia Burials at the Panthéon, Paris 19th-century memoirists Dumas family