Aletta Henriëtte Jacobs on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Aletta Henriëtte Jacobs (; 9 February 1854 – 10 August 1929) was a Dutch physician and women's suffrage activist. As the first woman officially to attend a Dutch university, she became one of the first female physicians in the Netherlands. In 1882, she founded the world's first birth control clinic and was a leader in both the Dutch and international women's movements. She led campaigns aimed at deregulating prostitution, improving women's working conditions, promoting peace and calling for women's right to vote.

Born in the mid-nineteenth century, Jacobs yearned to become a doctor like her father. Despite existing barriers, she fought to gain entry to higher education and graduated in 1879 with the first doctorate in medicine earned by a woman in the Netherlands. Providing medical services to women and children, she grew concerned over the health of working women, recognizing that as laws did not provide adequate protection for their health, their economic stability was compromised. She opened a free clinic to educate poor women about hygiene and child care and in 1882 expanded her services to include distribution of contraception information and devices. Though she continued to practice medicine until 1903, Jacobs increasingly turned her attention to activism with a view to improving women's lives.

From 1883, when Jacobs first challenged the authorities on women's right to vote, she strove throughout her life to change laws that limited women's access to equality. She was successful in her campaign to establish mandatory break laws in retail workers' employment and in attaining the vote for Dutch women in 1919. Involved in the international women's movement, Jacobs traveled throughout the world speaking about women's issues and documenting the socio-economic and political status of women. She was instrumental in the establishment of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom and an active participant in the peace movement. She is recognized internationally for her contributions to women's rights and status.

Aletta Henriëtte Jacobs was born on 9 February 1854 in Sappemeer, the Netherlands, to Anna de Jongh and Abraham Jacobs. She was the eighth of 11 children, born into a family of assimilated

Aletta Henriëtte Jacobs was born on 9 February 1854 in Sappemeer, the Netherlands, to Anna de Jongh and Abraham Jacobs. She was the eighth of 11 children, born into a family of assimilated  On 20 April 1871, Jacobs entered university, recognizing that other women's ability to pursue education would depend on her performance. When within months, news reached Jacobs' father that Thorbecke was mortally ill, Abraham insisted that his daughter be allowed to register without probation. On 30 May 1872, shortly after Thorbecke's death, Jacobs received the official notification of her admittance as a medical student. Despite periods of illness, she passed the preliminary part of her licensing examination on 12 April 1877 and the final test on 3 April 1878. Obtaining her state license to operate as a general practitioner in 1878, she began work on her doctoral thesis, ''Over localisatie van physiologische en pathologische verschijnselen in de groote hersenen'' (On the Localization of Physiological and Pathological Symptoms in the Cerebrum). At the time, the brain had not been studied much and brain physiology was an unusual choice for a dissertation. Graduating on 8 March 1879, Jacobs was the first woman to attend a Dutch university, as well as the first Dutch woman to receive a medical degree in the country, and the first to obtain a medical doctorate.

As news of her accomplishments appeared in newspapers throughout the country, Jacobs received numerous congratulatory letters. One came from a social reformer,

On 20 April 1871, Jacobs entered university, recognizing that other women's ability to pursue education would depend on her performance. When within months, news reached Jacobs' father that Thorbecke was mortally ill, Abraham insisted that his daughter be allowed to register without probation. On 30 May 1872, shortly after Thorbecke's death, Jacobs received the official notification of her admittance as a medical student. Despite periods of illness, she passed the preliminary part of her licensing examination on 12 April 1877 and the final test on 3 April 1878. Obtaining her state license to operate as a general practitioner in 1878, she began work on her doctoral thesis, ''Over localisatie van physiologische en pathologische verschijnselen in de groote hersenen'' (On the Localization of Physiological and Pathological Symptoms in the Cerebrum). At the time, the brain had not been studied much and brain physiology was an unusual choice for a dissertation. Graduating on 8 March 1879, Jacobs was the first woman to attend a Dutch university, as well as the first Dutch woman to receive a medical degree in the country, and the first to obtain a medical doctorate.

As news of her accomplishments appeared in newspapers throughout the country, Jacobs received numerous congratulatory letters. One came from a social reformer,

From her work with poor women, Jacobs recognized that repeated pregnancies, year after year, was not only impacting mothers' health, but causing high rates of

From her work with poor women, Jacobs recognized that repeated pregnancies, year after year, was not only impacting mothers' health, but causing high rates of

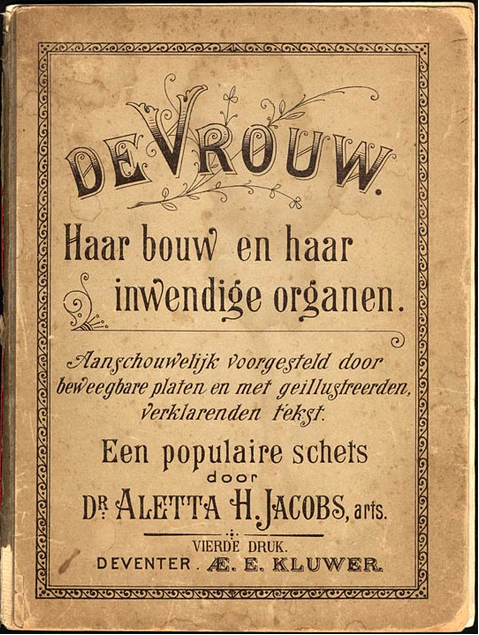

Between 1880 and during most of the 1890s, Jacobs devoted her time to her medical practice and radical politics, publishing articles and traveling with Gerritsen. She published articles in the ''Sociaal Weekblad'' defending the use of contraception and highlighting the problems retail workers experienced. In 1894, she published a campaign in several newspapers about the health of shop workers and the following year wrote an article on prostitution and sexually transmitted disease for the newspaper ''Amsterdammer''. Her position focused on health education rather than moral judgment. In 1897, Jacobs published ''De Vrouw: Haar bouw en haar inwendige organen'' (The Woman: Her construction and her internal organs), which was an innovative text describing a woman's anatomy and complete reproductive system, with movable illustrative plates accompanied by explanatory texts. The volume was republished six times between its initial appearance and 1921.

Jacobs published ''Vrouwenbelangen: Drie vraagstukken van aktuelen aard'' (Women's interests: Three current issues) in 1899, which discussed economic independence for women, voluntary

Between 1880 and during most of the 1890s, Jacobs devoted her time to her medical practice and radical politics, publishing articles and traveling with Gerritsen. She published articles in the ''Sociaal Weekblad'' defending the use of contraception and highlighting the problems retail workers experienced. In 1894, she published a campaign in several newspapers about the health of shop workers and the following year wrote an article on prostitution and sexually transmitted disease for the newspaper ''Amsterdammer''. Her position focused on health education rather than moral judgment. In 1897, Jacobs published ''De Vrouw: Haar bouw en haar inwendige organen'' (The Woman: Her construction and her internal organs), which was an innovative text describing a woman's anatomy and complete reproductive system, with movable illustrative plates accompanied by explanatory texts. The volume was republished six times between its initial appearance and 1921.

Jacobs published ''Vrouwenbelangen: Drie vraagstukken van aktuelen aard'' (Women's interests: Three current issues) in 1899, which discussed economic independence for women, voluntary

In 1903, Jacobs became president of the

In 1903, Jacobs became president of the  In 1914, shortly after the start of World War I, Jacobs promoted holding the

In 1914, shortly after the start of World War I, Jacobs promoted holding the

Jacobs left Amsterdam and moved to The Hague after the suffrage fight was won in 1919. Thanks to the international reputation she had gained from the suffrage movement, Jacobs' role as a pioneer of contraception was drawn on by birth control activists in the United States, such as

Jacobs left Amsterdam and moved to The Hague after the suffrage fight was won in 1919. Thanks to the international reputation she had gained from the suffrage movement, Jacobs' role as a pioneer of contraception was drawn on by birth control activists in the United States, such as

Jacobs died on 10 August 1929 in Baarn, at the , while on holiday. After her cremation, her ashes were placed in the Broese van Groenou family mausoleum in Loenen op de Veluwe until 1931, when they were placed with her husband's ashes in the in Driehuis. The following year, Bernard Premsela opened a contraception advice center in Amsterdam named in her honor. In the Netherlands, there are numerous awards and institutes which bear her name, such as the Aletta Jacobs Prize granted by the University of Groningen and a college in Hoogezand-Sappemeer. There is a

Jacobs died on 10 August 1929 in Baarn, at the , while on holiday. After her cremation, her ashes were placed in the Broese van Groenou family mausoleum in Loenen op de Veluwe until 1931, when they were placed with her husband's ashes in the in Driehuis. The following year, Bernard Premsela opened a contraception advice center in Amsterdam named in her honor. In the Netherlands, there are numerous awards and institutes which bear her name, such as the Aletta Jacobs Prize granted by the University of Groningen and a college in Hoogezand-Sappemeer. There is a

Short historical film showing Aletta Jacobs in Berlin in 1915

on her peace mission with Jane Addams and Alice Hamilton. * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Jacobs, Aletta 1854 births 1929 deaths 19th-century Dutch physicians Dutch feminists Dutch Jews Dutch pacifists Dutch obstetricians Dutch suffragists Dutch women physicians Free-thinking Democratic League politicians Jewish feminists Jewish pacifists Jewish physicians People from Hoogezand-Sappemeer University of Groningen alumni Women's International League for Peace and Freedom people 20th-century Dutch physicians 20th-century women physicians 19th-century women physicians 19th-century Dutch women 20th-century Dutch women Jewish suffragists

Early life and education (1854–1879)

Aletta Henriëtte Jacobs was born on 9 February 1854 in Sappemeer, the Netherlands, to Anna de Jongh and Abraham Jacobs. She was the eighth of 11 children, born into a family of assimilated

Aletta Henriëtte Jacobs was born on 9 February 1854 in Sappemeer, the Netherlands, to Anna de Jongh and Abraham Jacobs. She was the eighth of 11 children, born into a family of assimilated Jewish heritage

Jewish culture is the culture of the Jewish people, from its formation in ancient times until the current age. Judaism itself is not a faith-based religion, but an orthoprax and Ethnoreligious group, ethnoreligion, pertaining to deed, practic ...

. Her father was a doctor from whom she developed an interest from a young age in the field of medicine. She attended the village school and learned needlecrafts, completing her education in 1867. At the time, there were no educational opportunities for women apart from finishing school

A finishing school focuses on teaching young women social graces and upper-class cultural rites as a preparation for entry into society. The name reflects that it follows on from ordinary school and is intended to complete the education, wit ...

s. She enrolled in one and attended for two weeks, but found it to be "idiotic" and a waste of time. To continue her education, Jacobs worked as an apprentice dressmaker and studied at home, where her mother taught her French and German. In addition, her father taught her Greek and Latin.

Wanting to become a doctor like her father, Jacobs faced challenges, as higher education in 19th-century Netherlands was not open to women students. A family friend, the hygienist Levy Ali Cohen, encouraged Jacobs to become a pharmacy assistant, after learning in 1869 that a woman had been allowed to take the examination. She prepared for the test, studying with her father; her brother Sam, who was a pharmacist; and Cohen, and passed in July 1870, earning a diploma. She was encouraged by Cohen and Samuel Siegmund Rosenstein

Samuel Siegmund Rosenstein (20 February 1832 in Berlin – 31 January 1906 in The Hague) was a German physician.

He was the son of Rabbi Elhanan Rosenstein. He studied philosophy and medicine at the University of Berlin, receiving his medica ...

, rector of the University of Groningen, to continue her studies for two years in preparation for the entry examination for university. She received permission from J.W.A. Renssen, the director of the (National Higher Secondary School) in Sappemeer to listen to classes, becoming the first Dutch woman to attend high school. Learning that a male student who had passed his pharmacy examination was admitted to the university on the basis of his diploma, Jacobs wrote secretly to the chair of the Council of Ministers of the Netherlands, Johan Rudolph Thorbecke. She requested permission to begin her university studies prior to taking the entrance examination and was granted provisional approval by Thorbecke to attend as a one-year probationary student.

On 20 April 1871, Jacobs entered university, recognizing that other women's ability to pursue education would depend on her performance. When within months, news reached Jacobs' father that Thorbecke was mortally ill, Abraham insisted that his daughter be allowed to register without probation. On 30 May 1872, shortly after Thorbecke's death, Jacobs received the official notification of her admittance as a medical student. Despite periods of illness, she passed the preliminary part of her licensing examination on 12 April 1877 and the final test on 3 April 1878. Obtaining her state license to operate as a general practitioner in 1878, she began work on her doctoral thesis, ''Over localisatie van physiologische en pathologische verschijnselen in de groote hersenen'' (On the Localization of Physiological and Pathological Symptoms in the Cerebrum). At the time, the brain had not been studied much and brain physiology was an unusual choice for a dissertation. Graduating on 8 March 1879, Jacobs was the first woman to attend a Dutch university, as well as the first Dutch woman to receive a medical degree in the country, and the first to obtain a medical doctorate.

As news of her accomplishments appeared in newspapers throughout the country, Jacobs received numerous congratulatory letters. One came from a social reformer,

On 20 April 1871, Jacobs entered university, recognizing that other women's ability to pursue education would depend on her performance. When within months, news reached Jacobs' father that Thorbecke was mortally ill, Abraham insisted that his daughter be allowed to register without probation. On 30 May 1872, shortly after Thorbecke's death, Jacobs received the official notification of her admittance as a medical student. Despite periods of illness, she passed the preliminary part of her licensing examination on 12 April 1877 and the final test on 3 April 1878. Obtaining her state license to operate as a general practitioner in 1878, she began work on her doctoral thesis, ''Over localisatie van physiologische en pathologische verschijnselen in de groote hersenen'' (On the Localization of Physiological and Pathological Symptoms in the Cerebrum). At the time, the brain had not been studied much and brain physiology was an unusual choice for a dissertation. Graduating on 8 March 1879, Jacobs was the first woman to attend a Dutch university, as well as the first Dutch woman to receive a medical degree in the country, and the first to obtain a medical doctorate.

As news of her accomplishments appeared in newspapers throughout the country, Jacobs received numerous congratulatory letters. One came from a social reformer, Carel Victor Gerritsen

Carel Victor Gerritsen (2 February 1850 – 5 July 1905) was a Dutch politician known for his radical views. The husband of Aletta Jacobs, he was a proponent of open government, fair wages and birth control. He served as an alderman in Amsterdam ...

, who encouraged her and made introductions on her behalf to other women physicians. Despite her father's disapproval, Jacobs and Gerritsen began a correspondence, though they would not meet for several years. After her graduation, she contributed to her education by observing women physicians at various London hospitals, including the Great Ormond Street Hospital, London School of Medicine for Women and New Hospital for Women, where she met Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, the first woman medical practitioner in England, and her sister, Millicent Garrett Fawcett. Both women were deeply involved in the fight for women's suffrage as well as other social issues, including birth control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

. She also met like-minded social reformers, including Annie Besant

Annie Besant ( Wood; 1 October 1847 – 20 September 1933) was a British socialist, theosophist, freemason, women's rights activist, educationist, writer, orator, political party member and philanthropist.

Regarded as a champion of human f ...

, Charles Bradlaugh, Charles Robert

Charles I, also known as Charles Robert ( hu, Károly Róbert; hr, Karlo Robert; sk, Karol Róbert; 128816 July 1342) was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1308 to his death. He was a member of the Capetian House of Anjou and the only son of ...

and George Drysdale, as well as Alice Vickery

Alice Vickery (also known as A. Vickery Drysdale and A. Drysdale Vickery; 1844 – 12 January 1929) was an English physician, campaigner for women's rights, and the first British woman to qualify as a chemist and pharmacist. She and her life ...

, who influenced her ideas on social reform.

Early career (1879–1887)

Returning to the Netherlands in September 1879 to attend a medical conference in Amsterdam, Jacobs received so many requests for medical services that she decided not to return to England, but instead opened an independent practice on the Herengracht canal to treat women patients. Her clinic, on the corner of and was located in the Werkmansbond building. She was assisted byCornélie Huygens

Cornélie Lydie Huygens (13 June 1848 – 31 October 1902) was a Dutch writer, social democrat and feminist.

Biography

Huygens was born on 13 June 1848 in Haarlemmerliede. She was the daughter of Gerard William Otto Huygens and Cornelia Adelaide ...

in treating women and children, as women were not permitted to treat men. She grew increasingly concerned about the needs of working-class women and the poor conditions in which they lived and worked, realizing that impoverished women lacked knowledge of hygiene and child care. She began running biweekly clinics to advise them, but demand was so great she had to expand the sessions.

From her work with poor women, Jacobs recognized that repeated pregnancies, year after year, was not only impacting mothers' health, but causing high rates of

From her work with poor women, Jacobs recognized that repeated pregnancies, year after year, was not only impacting mothers' health, but causing high rates of infant mortality

Infant mortality is the death of young children under the age of 1. This death toll is measured by the infant mortality rate (IMR), which is the probability of deaths of children under one year of age per 1000 live births. The under-five morta ...

. Her contact with prostitutes led her to learn about and study sexually transmitted diseases, of which she had not previously been aware. In developing solutions for these women, Jacobs became convinced that reliable contraception would alleviate suffering and economic hardship resulting from too many children. Furthermore, it would improve the social welfare of society at large, preventing overpopulation. After reading an article by on occlusive pessaries, Jacobs wrote to him, embarking on a lengthy correspondence. Convinced that diaphragms would help her patients, she performed a clinical trial across a mixed sampling of her clients. Finding the trial was successful, she introduced the method of birth control (still widely known to English speakers as the ''Dutch Cap'') in the Netherlands and began counseling women on its use.

In 1882, Jacobs founded the first birth control clinic in the Netherlands and the first clinic in the world devoted solely to disseminating information on the topic. In her twice weekly clinics for the poor, which were well-attended, she provided birth control information and a contraceptive device – ''Dutch pessary,'' free of charge. This practice was widely criticized by other physicians, including Catharine van Tussenbroek

Catharine van Tussenbroek (4 August 1852 – 5 May 1925) was a Dutch physician and feminist. She was the second woman to qualify as a physician in the Netherlands and the first physician to confirm evidence of the ovarian type of ectopic pregnan ...

, the second Dutch woman to earn a medical degree. Physicians who argued against contraception maintained that it interfered with the "divine plan", encouraged extramarital sex, and would have a negative impact on fecundity and national growth. They saw unwanted pregnancy and venereal disease as apt punishment for sin.

In 1883, as the Parliamentary elections ensued, Jacobs learned from the liberal politician Samuel van Houten

Samuel van Houten (17 February 1837 – 14 October 1930) was a Dutch liberal politician and philosopher, who served as Minister of the Interior from 1894 to 1897.

Early life

Van Houten was born in Groningen into a wealthy Mennonite family. Hi ...

that women were not explicitly banned from voting, and she wrote a letter to the mayor and city council of Amsterdam, questioning why she was not included on the voter registration list. She included her evidence that she met all the requirements of a voter. She received a reply that while a narrow interpretation might indicate that women were not barred, custom required that she would need to challenge whether women were entitled to civil rights and full citizenship. Jacobs appealed the decision to the Amsterdam District Court, which replied that women were not citizens. She then appealed to the Supreme Court, which ruled that as taxes for married women and children were paid by their husbands and fathers, the law was clear that women were not citizens entitled to vote, ignoring the fact that Jacobs paid taxes as an unmarried woman. By 1884, Jacobs' relationship with Gerritsen had turned into a romance and the couple entered into a free marriage

Free may refer to:

Concept

* Freedom, having the ability to do something, without having to obey anyone/anything

* Freethought, a position that beliefs should be formed only on the basis of logic, reason, and empiricism

* Emancipate, to proc ...

, though until 1886, Gerritsen lived in Amersfoort.

Jacobs joined the Neo-Malthusian League of Holland and along with her husband, continued working to improve social conditions among the country's poor and working classes. In addition to her work in hygiene and contraception, beginning in 1886, Jacobs campaigned for retail establishments to provide employees with benches where they could rest when they were not attending to customers. At the time it was common for female employees to spend more than 10 hours standing, causing major health and gynecological problems. Two decades later the matter of breaks was regulated in a law.

Advised by a member of the Supreme Court that she might win a second appeal on women's suffrage, Jacobs initially considered continuing the fight, but in 1885 an amendment to the constitution was proposed by Minister Jan Heemskerk to add the word "man" to the electoral provisions. The Constitution of 1887, when it was adopted, explicitly granted voting rights only to male residents.

Activism (1888–1903)

In 1888, Gerritsen was involved in the founding of the progressive liberal Electoral Association Amsterdam and was elected to the City Council of Amsterdam. He strongly supported universal suffrage, compulsory education and social reforms, such as the establishment of minimum wages and maximum working hours. In 1892 he helped found theRadical League

The Radical League ( nl, Radicale Bond) was a progressive liberal political party in the Netherlands from its founding in 1892 until it merged with the left wing of the Liberal Union to form the Free-thinking Democratic League in 1901.

History

...

, the first Dutch political party to admit women. He and Jacobs were both actively involved in the party, which besides universal suffrage advocated for separation of church and state. In part because they wanted to have children, the coupled decided to formalize their marriage and were legally wed on 28 April 1892. On 9 September 1893, Jacobs, who retained her own name after marriage, went into labor and delivered a son; however, the baby lived only one day because of careless treatment by the midwife during the birth. Though she was one of the founders of the Vereeniging voor Vrouwenkiesrecht

The Vereeniging voor Vrouwenkiesrecht (Association for Women's Suffrage) was a women's rights organization active in the Netherlands from 1894 to 1919. It was devoted to women's suffrage. It was the main women's suffrage movement in the Netherland ...

(Society for Women's Suffrage) in 1894, she was unable to attend the founding meeting because of surgery following her child's birth. Around the same time, she closed her free clinics to the poor.

family planning

Family planning is the consideration of the number of children a person wishes to have, including the choice to have no children, and the age at which they wish to have them. Things that may play a role on family planning decisions include marita ...

and regulating prostitution

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in Sex work, sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, n ...

. In the three articles, she argued in favor of the economic and political independence of women, as well as women's rights to plan their family size as a means of economic independence. In the third article, she criticized state regulation of prostitution, in part because they required prostitutes to register and undergo medical examination. She believed targeting sex workers without addressing the misconduct of their clients would be ineffective in combating the spread of venereal diseases. She attended the 1899 International Council of Women's 2nd Congress, held in London. It had a profound effect on her, and she began to consider focusing all of her efforts into securing voting rights for women, as a path to eliminate barriers to women in other areas. By 1900, the VvVk (Society for Women's Suffrage) had around 20,000 members.

At the turn of the twentieth century in May 1900, together with Arnold Aletrino, Jacobs co-founded the ''Nederlandsche Vereeniging tot Bevordering der Belangen van Verpleegsters en Verplegers'' (Dutch Society to promote the interests of male and female nurses), bent on improving socio-economic opportunities for nurses. Between 1902 and 1912, she wrote articles on international nursing and served as an editor for ''Nosokomos'', the society's journal. Beginning in 1900, Jacobs published translations of feminist theory, such as ''Women and Economics'' by Charlotte Perkins Gilman and ''Women and Labor'' by Olive Schreiner (1910). In 1901, she and Gerritsen left the Radical League and joined the founders of the Vrijzinnig Democratische Bond

The Free-thinking Democratic League ( nl, Vrijzinnig Democratische Bond, VDB) was a progressive liberal political party in the Netherlands. Established in 1901, it played a relatively large role in Dutch politics, supplying one Prime Minister, Wi ...

(Free-thinking Democratic League). (She continued to be associated with the league, serving on its board from 1921 through 1927.) Jacobs also regularly published articles in ''Sociaal Weekblad'' addressing women's working conditions and was finally rewarded in 1903 when the National Bureau for Women's Work published a preliminary draft law to reform working conditions. Jacobs retired from her medical practice in 1903, thereafter devoting her time to women's suffrage, financing her efforts from the sale of her private library.

Women's suffrage (1903–1919)

In 1903, Jacobs became president of the

In 1903, Jacobs became president of the Vereeniging voor Vrouwenkiesrecht

The Vereeniging voor Vrouwenkiesrecht (Association for Women's Suffrage) was a women's rights organization active in the Netherlands from 1894 to 1919. It was devoted to women's suffrage. It was the main women's suffrage movement in the Netherland ...

, holding the post for the next 16 years. In 1904, she traveled with her husband to Berlin to attend the Congress of the International Council of Women (ICW) and joined with the suffragists who broke off from the ICW at the conference to form the International Woman Suffrage Alliance (IWSA). As soon as the conference was over, the couple traveled to the United States and made a cross-country tour. Together they wrote ''Brieven uit en over Amerika'' (Letters from and about America), which was published in 1906. During their travels, Gerritsen became ill and died in 1905 from cancer. After recovering from a depression caused by her loss, Jacobs resumed her suffrage work in 1906, touring with Carrie Chapman Catt through the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

.

Jacobs spearheaded the organization of the 1908 IWSA Congress, the first to be held in the Netherlands. It took place in June in Amsterdam bringing international delegates to the city, spurring growth of the Dutch suffrage movement. In 1910, she traveled to South Africa, invited by activists who called on her organizational services.

She toured from Cape Town to Johannesburg making speeches on suffrage, as well as hygiene, sanitation, prostitution and venereal diseases, while calling for universal sex education. In 1911, after the IWSA conference in Stockholm

Stockholm () is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in Sweden by population, largest city of Sweden as well as the List of urban areas in the Nordic countries, largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people liv ...

, Jacobs and Catt embarked on a 16-month tour to evaluate women's legal and social positions and encourage women to struggle for pertinent improvements. The trip took them to "South Africa, the Middle East, India, Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, which ...

, Burma, the Philippines, China and Japan". Jacobs financed the trip by writing articles about their adventures for the newspaper ''De Telegraaf''.

In 1914, shortly after the start of World War I, Jacobs promoted holding the

In 1914, shortly after the start of World War I, Jacobs promoted holding the International Women's Congress

International is an adjective (also used as a noun) meaning "between nations".

International may also refer to:

Music Albums

* ''International'' (Kevin Michael album), 2011

* ''International'' (New Order album), 2002

* ''International'' (The T ...

in The Hague, given the country's neutrality. Intended as a forum for women from throughout the world to meet and discuss opposition to war, the meeting was chaired by the pacifist Jane Addams from Chicago. Coordinated by Jacobs, Mia Boissevain

Maria (Mia) Boissevain (1878–1959) was a Dutch malacologist and feminist.

Life

Boissevain was the youngest of nine children. Her father was a shipowner from a rich Huguenot merchant family and her mother was the daughter of a lawyer.

Educati ...

, and Rosa Manus

Rosette Susanna "Rosa" Manus ( was born 20 August 1881 and died either at Auschwitz or Ravensbruck in 1942. She was a Jewish Dutch pacifist and female suffragist and was involved in women's movements and anti-war movements. She served as the ...

, the conference, which opened on 28 April 1915, was attended by 1,136 participants from both neutral and non- belligerent nations, and resulted in the establishment of an organization which would become the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF). Jacobs became the vice-president of both the international organization and the Dutch chapter of WILPF. After the conference closed on 3 May 1915, Addams and Jacobs, along with Chrystal Macmillan, Rosika Schwimmer and Mien van Wulfften Palthe-Broese van Groenou and others, formed two delegations of women who were dispatched to meet European heads of state over the next several months. The women secured agreement from reluctant Foreign Ministers, who overall felt that such a body would be ineffective. Nevertheless, they agreed to participate, or not impede creation of a neutral mediating body, if other nations agreed and if US President Woodrow Wilson would initiate a body. In the midst of the war, Wilson refused.

In 1917 Dutch women obtained the right to stand in elections, though they could not vote. Jacobs stood as a candidate for the Vrijzinnig Democratische Bond in the election of 1918 and though she received more votes than any other woman candidate, she was not elected. Along with MP Henri Marchant, in 1918 Jacobs founded the journal, ''De opbouw, Democratisch Tijdschrift'' (The building, Democratic Magazine) in which she wrote several articles between 1918 and 1924. Marchant introduced a women's suffrage bill which was adopted in 1919, and signed by Queen Wilhelmina on 18 September 1919. Shortly thereafter, Jacobs resigned from the presidency of the Vereeniging voor Vrouwenkiesrecht.

Later life (1919–1924)

Jacobs left Amsterdam and moved to The Hague after the suffrage fight was won in 1919. Thanks to the international reputation she had gained from the suffrage movement, Jacobs' role as a pioneer of contraception was drawn on by birth control activists in the United States, such as

Jacobs left Amsterdam and moved to The Hague after the suffrage fight was won in 1919. Thanks to the international reputation she had gained from the suffrage movement, Jacobs' role as a pioneer of contraception was drawn on by birth control activists in the United States, such as Margaret Sanger

Margaret Higgins Sanger (born Margaret Louise Higgins; September 14, 1879September 6, 1966), also known as Margaret Sanger Slee, was an American birth control activist, sex educator, writer, and nurse. Sanger popularized the term "birth control ...

. Between 1922 and 1923, Jacobs served on the advisory board of the Voluntary Parenthood League The Voluntary Parenthood League (VPL) was an organization that advocated for contraception during the birth control movement in the United States. The VPL was founded in 1919 by Mary Dennett. The VPL was a rival organization to Margaret Sanger' ...

, established by Mary Dennett. The following year, she was the guest of honor at the VPL's annual conference held in New York City.

Having lost most of her money in poor investments, Jacobs was supported by her friend Mien van Wulfften Palthe-Broese van Groenou. Between 1923 and 1924, she worked on her autobiography, at her home on 46 Van Aerssenstraat, refusing offers from family friends to reside with them, so that she could spread out her clippings and journals in her own home. After completing her autobiography she lived with the Broese van Groenou family. She continued to attend the conferences of the International Council of Women, International Alliance of Women and WILPF until her death.

Death and legacy

planetoid

According to the International Astronomical Union (IAU), a minor planet is an astronomical object in direct orbit around the Sun that is exclusively classified as neither a planet nor a comet. Before 2006, the IAU officially used the term ''mino ...

named after her and a plaque with her image is displayed on her former house in Amsterdam at 15 Tesselschadestraat. Between 11 August 2009 and 28 January 2013 the Atria Institute on gender equality and women's history was known as the ''Aletta Institute for Women's History'', in her honor. Her personal papers are a part of the collections of the institute. Her life was adapted into film in 1995 as '' Aletta Jacobs: Het Hoogste Streven'' (The Highest Aspiration).

In 1903, when she retired, Jacobs sold her collection of 2,000 books, magazines and pamphlets on women's history to the John Crerar Library in Chicago. The Crerar Library added English language volumes to her collection which mainly contained titles in Dutch, French and German, doubling the collection size. In 1954, the University of Kansas bought the ''Gerritsen Collection

The Gerritsen Collection (also known as the Gerritsen Collection of Aletta H. Jacobs or the Gerritsen Collection of Women's History) is a diverse collection of women's archival materials and feminist records covering fifteen languages and over 4,7 ...

'', which has volumes dating from the 16th century, but mainly focuses on women of the 19th and early-20th centuries. In particular, the collection contains works on anti-feminist views, education of women, the legal status of women throughout history, prostitution, sexual relations, suffrage, women's economic and employment history, and is considered a significant resource for primary materials of women's studies.

At a time when married women were typically forced to relinquish their names and employment, Jacobs retained her own identity and continued to work outside her home, inspiring others to follow suit. Her pioneering birth control clinic preceded both Margaret Sanger's and Marie Stopes

Marie Charlotte Carmichael Stopes (15 October 1880 – 2 October 1958) was a British author, palaeobotanist and campaigner for eugenics and women's rights. She made significant contributions to plant palaeontology and coal classification, ...

's clinics in the United States and England by more than three decades and her role in the contraception movement was influential in helping those women who followed in her footsteps, in establishing clinics throughout Europe and the United States by the time of her death. Her campaigns regarding working conditions for women and the right to vote were successful in changing Dutch law, and her work in the peace movement led to the establishment of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. In assessing her own career, Jacobs wrote a letter to Catt in 1928:

See also

* List of peace activists * List of suffragists and suffragettesSelected works

* * * * * * * * * English version: ''Memories; My Life as an International Leader in Health, Suffrage, and Peace'' translated by Annie Wright Translations & edited by Harriet Feinberg. The Feminist Press at CUNY, 1996.Notes

References

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Short historical film showing Aletta Jacobs in Berlin in 1915

on her peace mission with Jane Addams and Alice Hamilton. * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Jacobs, Aletta 1854 births 1929 deaths 19th-century Dutch physicians Dutch feminists Dutch Jews Dutch pacifists Dutch obstetricians Dutch suffragists Dutch women physicians Free-thinking Democratic League politicians Jewish feminists Jewish pacifists Jewish physicians People from Hoogezand-Sappemeer University of Groningen alumni Women's International League for Peace and Freedom people 20th-century Dutch physicians 20th-century women physicians 19th-century women physicians 19th-century Dutch women 20th-century Dutch women Jewish suffragists