Albert C. Smith (United States Army Officer) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Following the War, the 14th Armored Division was stationed in

Following the War, the 14th Armored Division was stationed in

Generals of World War II

{{DEFAULTSORT:Smith, Albert C. 1894 births 1974 deaths United States Army Cavalry Branch personnel People from Warrenton, Virginia United States Army generals United States Military Academy alumni United States Army Infantry Branch personnel United States Army Command and General Staff College alumni United States Army personnel of World War I United States Army Command and General Staff College faculty United States Military Academy faculty Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army) Recipients of the Silver Star Officers of the Legion of Honour Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1939–1945 (France) Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Military personnel from Virginia United States Army generals of World War II

Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

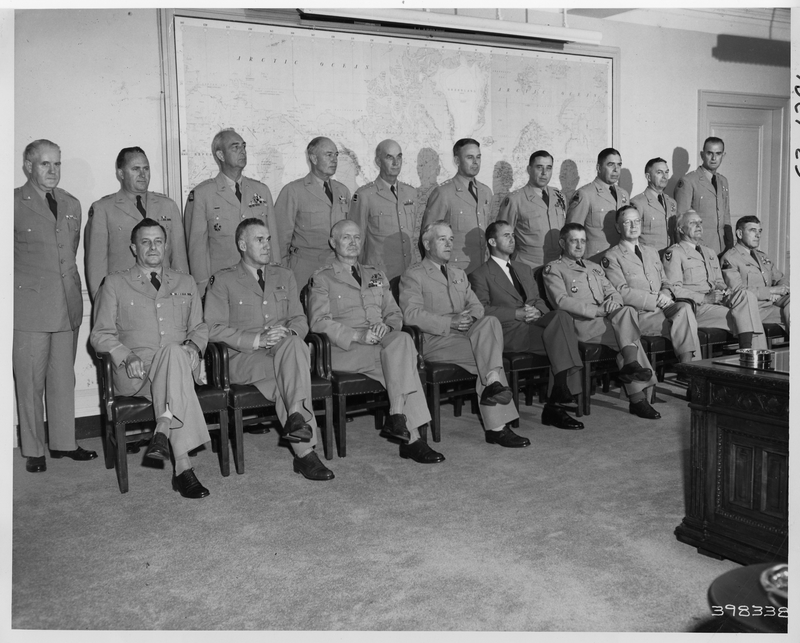

Albert Cowper Smith (June 5, 1894 – January 24, 1974) was an officer in the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare, land military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight Uniformed services of the United States, U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army o ...

. He is most noted for his service as Commanding General of the 14th Armored Division during the later part of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. Smith and his division liberated Prisoner-of-war camp

A prisoner-of-war camp (often abbreviated as POW camp) is a site for the containment of enemy fighters captured by a belligerent power in time of war.

There are significant differences among POW camps, internment camps, and military prisons. ...

s, Oflag XIII-B

Oflag XIII-B was a German Army World War II prisoner-of-war camp for officers ('' Offizierslager''), originally in the Langwasser district of Nuremberg. In 1943 it was moved to a site south of the town of Hammelburg in Lower Franconia, Bavaria, ...

and Stalag VII-A

Stalag VII-A (in full: ''Kriegsgefangenen-Mannschafts-Stammlager VII-A'') was the largest prisoner-of-war camp in Nazi Germany during World War II, located just north of the town of Moosburg in southern Bavaria. The camp covered an area of . It ser ...

in April 1945.

Following the war, Smith held several important assignments including several divisional commands or as acting Commanding General of the Fifth United States Army and completed his career as Chief of the Office of Military History in September 1955.

Early years

Albert C. Smith was born on June 5, 1894, inWarrenton, Virginia

Warrenton is a town in Fauquier County, Virginia, of which it is the seat of government. The population was 9,611 at the 2010 census, up from 6,670 at the 2000 census. The estimated population in 2019 was 10,027. It is at the junction of U.S. R ...

, as the son of Eugene Albert and Blanch Baker Smith. Following the graduation from the Gordon Military Institute in Barnesville, Georgia

Barnesville is a city in Lamar County, Georgia, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 6,755, up from 5,972 at the 2000 census. The city is the county seat of Lamar County.

Barnesville was once dubbed the "Buggy Capi ...

, he sought for an appointment to the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

at West Point, New York

West Point is the oldest continuously occupied military post in the United States. Located on the Hudson River in New York, West Point was identified by General George Washington as the most important strategic position in America during the Ame ...

, but it was hard to come by, so he entered the Virginia Polytechnic Institute

Virginia Tech (formally the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University and informally VT, or VPI) is a public land-grant research university with its main campus in Blacksburg, Virginia. It also has educational facilities in six re ...

in Blacksburg, Virginia

Blacksburg is an incorporated town in Montgomery County, Virginia, United States, with a population of 44,826 at the 2020 census. Blacksburg, as well as the surrounding county, is dominated economically and demographically by the presence of ...

, instead.

Smith completed almost three years there and finally received an appointment to West Point in June 1913. He was a member of the class which produced more than 55 future general officers, including two Army Chiefs of Staff

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

Joseph L. Collins and Matthew B. Ridgway. Other classmates include: Clare H. Armstrong, Aaron Bradshaw Jr., Mark W. Clark

Mark Wayne Clark (May 1, 1896 – April 17, 1984) was a United States Army officer who saw service during World War I, World War II, and the Korean War. He was the youngest four-star general in the US Army during World War II.

During World War I ...

, John T. Cole, Norman D. Cota, John M. Devine, William W. Eagles, Theodore L. Futch, Charles H. Gerhardt, Augustus M. Gurney

Augustus Milton Gurney (February 18, 1895 – April 10, 1967) was an officer in the United States Army with the rank of brigadier general during World War II. A graduate of the United States Military Academy, he served mostly in the staff positio ...

, Ernest N. Harmon, William Kelly Harrison Jr., Robert W. Hasbrouck

Robert W. Hasbrouck (February 2, 1896 - August 19, 1985) was a career officer in the United States Army. He attained the rank of major general and was a recipient of numerous awards and decorations, including the Army Distinguished Service Medal, ...

, Frederick A. Irving, Laurence B. Keiser, Charles S. Kilburn, Bryant E. Moore, Daniel Noce, Onslow S. Rolfe, Herbert N. Schwarzkopf, George D. Wahl, Raymond E. S. Williamson, and George H. Weems.

He graduated with Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University o ...

degree on April 20, 1917, shortly following the American entry into World War I

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, p ...

and was commissioned second lieutenant in the Cavalry Branch. Smith completed his basic training at Fort Sam Houston

Fort Sam Houston is a U.S. Army post in San Antonio, Texas.

"Fort Sam Houston, TX • About Fort Sam Houston" (overview),

US Army, 2007, webpageSH-Army.

Known colloquially as "Fort Sam," it is named for the U.S. Senator from Texas, U.S. Represen ...

, Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

, while attached to 3rd Cavalry Regiment and was promoted to the permanent rank of first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a ...

on May 15, 1917, and to the temporary rank of captain on August 5 that year. He embarked for France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

in October 1917 and his regiment was tasked with the operation of three major horse remount depots. The three squadrons were charged with the purchase of horses, mules and forage, the care, conditioning, and training of remounts before issue, and the distribution and issue of remounts to the American Expeditionary Force.

Smith was later transferred to the headquarters, U.S. First Army under General John J. Pershing and became Secretary of the General Staff, VII Corps 7th Corps, Seventh Corps, or VII Corps may refer to:

* VII Corps (Grande Armée), a corps of the Imperial French army during the Napoleonic Wars

* VII Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German Army prior to and during World War I

* VII ...

under Major generals Omar Bundy

Major General Omar Bundy (June 17, 1861 – January 20, 1940) was a career United States Army officer who was a veteran of the American Indian Wars, Spanish–American War, Philippine–American War, Pancho Villa Expedition, and World War I.

A n ...

and William G. Haan. While in this capacity, he took part in the Meuse-Argonne offensive and following the Armistice, Smith participated in the occupation of the Rhineland, while stationed at the corps headquarters in the town of Wittlich

The town of Wittlich (; Moselle Franconian: ''Wittlech'') is the seat of the Bernkastel-Wittlich district in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. Its historic town centre and the beauty of the surrounding countryside make the town a centre for tourism i ...

.

He was later ordered to Montabaur

Montabaur () is a town and the district seat of the Westerwaldkreis in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. At the same time, it is also the administrative centre of the ''Verbandsgemeinde'' of Montabaur – a kind of collective municipality – to w ...

and assumed duty as Aide-de-Camp to the commanding general, 1st Infantry Division, Edward F. McGlachlin. Smith remained in this capacity until September 1919, when he was ordered back to the United States.

Interwar period

Upon his return stateside, Smith was reverted to his permanent rank of first lieutenant and attached to the14th Cavalry Regiment

The 14th Cavalry Regiment is a cavalry regiment of the United States Army. It has two squadrons that provide reconnaissance, surveillance, and target acquisition for Stryker brigade combat teams. Constituted in 1901, it has served in conflicts ...

at Fort Sam Houston

Fort Sam Houston is a U.S. Army post in San Antonio, Texas.

"Fort Sam Houston, TX • About Fort Sam Houston" (overview),

US Army, 2007, webpageSH-Army.

Known colloquially as "Fort Sam," it is named for the U.S. Senator from Texas, U.S. Represen ...

, Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

. He remained with that outfit until November that year and joined the headquarters of Southern Army Department for duty in the Plans and Training Division. While in this capacity, Smith was promoted again to Captain on April 13, 1920, and finally left this assignment in January 1921 in order to rejoin 14th Cavalry at Fort Des Moines, Iowa

Iowa () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wisconsin to the northeast, Illinois to th ...

.

After several months in Iowa, Smith was transferred to the staff of United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

at West Point, New York

West Point is the oldest continuously occupied military post in the United States. Located on the Hudson River in New York, West Point was identified by General George Washington as the most important strategic position in America during the Ame ...

, and served as an Instructor in the Department of Natural and Experimental Philosophy until September 1926, when he entered the Army Cavalry School at Fort Riley

Fort Riley is a United States Army installation located in North Central Kansas, on the Kansas River, also known as the Kaw, between Junction City and Manhattan. The Fort Riley Military Reservation covers 101,733 acres (41,170 ha) in Ge ...

, Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to th ...

. He graduated in June 1927 and joined 13th Cavalry Regiment located at Fort Riley. His tenure with 13th Cavalry lasted until April 1929, when he returned to the United States Military Academy at West Point as Assistant Professor in the Department of Natural and Experimental Philosophy. Smith was promoted to major on October 1, 1932.

In August 1934, Smith entered the Army Command and General Staff School

The United States Army Command and General Staff College (CGSC or, obsolete, USACGSC) at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, is a graduate school for United States Army and sister service officers, interagency representatives, and international military ...

at Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., and the oldest perma ...

, Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to th ...

, and graduated from the two-year course in June 1936. He then remained at the School as an Instructor until July 1940. During that period, he witnessed the development of Armoured warfare

Armoured warfare or armored warfare (mechanized forces, armoured forces or armored forces) (American English; see spelling differences), is the use of armored fighting vehicles in modern warfare. It is a major component of modern methods of ...

doctrine in the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare, land military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight Uniformed services of the United States, U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army o ...

and gradual mechanization of Cavalry units.

His old 13th Cavalry Regiment was mechanized in mid-June 1940, redesignated 13th Armored Regiment and Smith joined him as newly promoted lieutenant colonel and Regimental Intelligence officer. He served in this capacity under Colonel Raymond E. McQuillin until November that year and then assumed duty as Plans and Training officer of the Armored Force Replacement Training Center at Fort Knox, Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

.

World War II

In April 1941, Smith was transferred toPine Camp

Fort Drum is a U.S. Army military reservation and a census-designated place (CDP) in Jefferson County, on the northern border of New York, United States. The population of the CDP portion of the base was 12,955 at the 2010 census. It is home t ...

, New York and joined the headquarters of newly activated 4th Armored Division under Major General John S. Wood as Assistant Chief of Staff for Operations (G-3).

Smith was promoted to the temporary rank of brigadier general on September 10, 1942, and joined the recently activated 14th Armored Division, commanded by Major General Vernon Prichard

Major General Vernon Edwin "Prich" Prichard (January 25, 1892 − July 10, 1949) was an American football quarterback and United States Army officer. He played college football with Army and was selected as a first-team All-American in 1914. He b ...

, at Camp Chaffee, Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the O ...

. While there, he was appointed Commander of Divisional Combat command A, a combined brigade size unit of tanks, armored infantry, armored field artillery battalions and engineer units.

He commanded his combat command during an intensive period of training and then during the Tennessee maneuvers from November 1943 until January 1944. In September 1944 Smith succeeded Major General Prichard, who was sent to command the 1st Armored Division on the Italian front, in command of the division and embarked for the European Theater

The European theatre of World War II was one of the two main theatres of combat during World War II. It saw heavy fighting across Europe for almost six years, starting with Germany's invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939 and ending with the ...

(ETO) by mid-October 1944. The 14th Armored Division landed at Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fra ...

in southern France on October 29 and within two weeks some of its elements were ordered to the defensive positions along the Franco-Italian frontier.

In mid-November 1944, the division took part in the drive through the Vosges Mountains

The Vosges ( , ; german: Vogesen ; Franconian and gsw, Vogese) are a range of low mountains in Eastern France, near its border with Germany. Together with the Palatine Forest to the north on the German side of the border, they form a single ...

and participated in the heavy combats at Gertwiller, Benfeld, and Barr Barr may refer to:

Places

* Barr (placename element), element of place names meaning 'wooded hill', 'natural barrier'

* Barr, Ayrshire, a village in Scotland

* Barr Building (Washington, DC), listed on the US National Register of Historic Places

...

. Smith and his division subsequently took part in the Operation Nordwind

Operation Northwind (german: Unternehmen Nordwind) was the last major Nazi Germany, German offensive of World War II on the Western Front (World War II), Western Front. Northwind was launched to support the German Ardennes offensive campaign in ...

, major German offensive in Rhineland-Palatinate

Rhineland-Palatinate ( , ; german: link=no, Rheinland-Pfalz ; lb, Rheinland-Pfalz ; pfl, Rhoilond-Palz) is a western state of Germany. It covers and has about 4.05 million residents. It is the ninth largest and sixth most populous of the ...

, Alsace

Alsace (, ; ; Low Alemannic German/ gsw-FR, Elsàss ; german: Elsass ; la, Alsatia) is a cultural region and a territorial collectivity in eastern France, on the west bank of the upper Rhine next to Germany and Switzerland. In 2020, it had ...

and Lorraine

Lorraine , also , , ; Lorrain: ''Louréne''; Lorraine Franconian: ''Lottringe''; german: Lothringen ; lb, Loutrengen; nl, Lotharingen is a cultural and historical region in Northeastern France, now located in the administrative region of Gra ...

. The major fighting between January 1 and 8 occurred in the Vosges Mountains and two combat commands of the division were in almost continuous action against the German thrusts. With the failure of his attack in the Vosges, the enemy attempted to break through to Hagenau and threaten Strasbourg and the Saverne Gap by attacks at Hatten

Hatten is a municipality in Oldenburg, in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated southeast of Oldenburg, on the North-West edge of the Wildeshausen Geest Nature Park.

Activities

Tourism endeavours emphasise the recreational and sporting opport ...

and Rittershoffen, two small villages located side by side on the Alsatian Plain. However, this, the strongest attack of Operation Nordwind, was halted by the 14th Armored Division in the fierce defensive Battle of Hatten-Rittershoffen which ranged from January 9 to 21, 1945.

With advancement into the heart of Germany, Smith and his division liberated Oflag XIII-B

Oflag XIII-B was a German Army World War II prisoner-of-war camp for officers ('' Offizierslager''), originally in the Langwasser district of Nuremberg. In 1943 it was moved to a site south of the town of Hammelburg in Lower Franconia, Bavaria, ...

and Stalag XIII-C

Stalag XIII-C was a German Army World War II prisoner-of-war camp ('' Stammlager'') built on what had been the training camp at Hammelburg, Lower Franconia, Bavaria, Germany.

Camp history

Hammelburg was a large German Army training camp, set up ...

, Prisoner-of-war camp

A prisoner-of-war camp (often abbreviated as POW camp) is a site for the containment of enemy fighters captured by a belligerent power in time of war.

There are significant differences among POW camps, internment camps, and military prisons. ...

s at Hammelburg

Hammelburg is a town in Bavaria, Germany. It sits in the district of Bad Kissingen, in Lower Franconia. It lies on the river Franconian Saale, 25 km west of Schweinfurt. Hammelburg is the oldest winegrowing town (''Weinstadt'') in Francon ...

, Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

on April 6, 1945, and another POW camp, Stalag VII-A

Stalag VII-A (in full: ''Kriegsgefangenen-Mannschafts-Stammlager VII-A'') was the largest prisoner-of-war camp in Nazi Germany during World War II, located just north of the town of Moosburg in southern Bavaria. The camp covered an area of . It ser ...

near Moosburg

Moosburg an der Isar (Central Bavarian: ''Mooschbuag on da Isa'') is a town in the ''Landkreis'' Freising of Bavaria, Germany.

The oldest town between Regensburg and Italy, it lies on the river Isar at an altitude of 421 m (1381 ft). ...

on April 29. On May 2 and 3, the 14th Armored liberated several sub-camps of the Dachau concentration camp. Upon entering the towns of Mühldorf and Ampfing

Ampfing is a municipality in the district of Mühldorf in Bavaria in Germany, and a name of a small town of the same name.

History

The Battle of Mühldorf was fought on 28 September 1322 between Bavaria and Austria in Ampfing Heath. The Bavaria ...

, units of the division discovered three large forced labor camps containing thousands of Polish and Soviet civilians. Units also liberated two additional camps nearby holding Jewish prisoners.

Smith was responsible for the liberation of some 200,000 Allied prisoners of war from German prison camps. Among those liberated were approximately 20,000 American soldiers, sailors and airmen, as well as an estimated 40,000 troops from Great Britain and the Commonwealth.

For his service during World War II, Smith was decorated with the Army Distinguished Service Medal, Silver Star, Bronze Star Medal or Army Commendation Medal

The Commendation Medal is a mid-level United States military decoration presented for sustained acts of heroism or meritorious service. Each branch of the United States Armed Forces issues its own version of the Commendation Medal, with a fifth ...

. He was also decorated with Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon ...

and Croix de Guerre with Palm by the Government of France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

.

Postwar service

Following the War, the 14th Armored Division was stationed in

Following the War, the 14th Armored Division was stationed in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, where it participated in the occupation duty until the beginning of August 1945, when it was ordered back to the United States for deactivation. The 14th Armored was deactivated at Camp Patrick Henry

Camp may refer to:

Outdoor accommodation and recreation

* Campsite or campground, a recreational outdoor sleeping and eating site

* a temporary settlement for nomads

* Camp, a term used in New England, Northern Ontario and New Brunswick to descri ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, on September 16, 1945, and Smith was ordered to Fort Jackson, South Carolina

)'' Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, and assumed command of 30th Infantry Division.

Smith supervised the demobilization of the troops until December 1945, when 30th Division was deactivated and he was reverted to his peacetime rank of colonel ordered to Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, for duty as President of War Department Board for Selection of Regular Army Officers. While in this capacity, he was shortly thereafter promoted again to Brigadier general and ordered to the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, where he assumed duty as Assistant Division Commander, 86th Infantry Division.

While in this capacity, Smith served as deputy to Major General Harry Hazlett

Harry Fouts Hazlett (April 17, 1884 – September 27, 1960) was a career officer in the U.S. Army. Prior to that he was an American football coach for the Canton Professionals-Bulldogs of the "Ohio League", which was the direct predecessor to th ...

and participated in the repatriation of Japanese prisoners of war on Leyte

Leyte ( ) is an island in the Visayas group of islands in the Philippines. It is eighth-largest and sixth-most populous island in the Philippines, with a total population of 2,626,970 as of 2020 census.

Since the accessibility of land has be ...

until February 1947. He was subsequently ordered to Japan and joined the headquarters of 24th Infantry Division under Major General James A. Lester as assistant division commander. The division was stationed on Kyushu and maintained order during the occupation duties.

Smith was promoted again to major general on January 24, 1948, and succeeded general Lester as division commander. He departed the division by the end of April 1949 and returned to the United States for duty as commanding general of 2nd Armored Division at Fort Hood

Fort Hood is a United States Army post located near Killeen, Texas. Named after Confederate General John Bell Hood, it is located halfway between Austin and Waco, about from each, within the U.S. state of Texas. The post is the headquarter ...

, Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

. Following the outbreak of the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

, Smith's division was tasked with the training of replacement units for combat.

He was sent to Fort Sam Houston

Fort Sam Houston is a U.S. Army post in San Antonio, Texas.

"Fort Sam Houston, TX • About Fort Sam Houston" (overview),

US Army, 2007, webpageSH-Army.

Known colloquially as "Fort Sam," it is named for the U.S. Senator from Texas, U.S. Represen ...

, Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

, in November 1950 and assumed duty as Deputy Commander, Fifth United States Army under Lieutenant General Stephen J. Chamberlin

Stephen Jones Chamberlin (23 December 1889 – 23 October 1971) was a lieutenant general in the United States Army who served during World War II as General of the Army Douglas MacArthur's Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3, the staff officer in cha ...

. Upon the retirement of general Chamberlin in December 1951, Smith assumed his duties and served as Acting general of Fifth Army until July 1952, when new commanding general, William B. Kean relieved him.

Smith then resumed his duties as deputy commander and remained in that capacity until February 1953, when he was ordered to Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, for duty as Chief of the Office of Military History. He retired on September 30, 1955, after 38 years of active service.

Death

Following his retirement, Smith settled inWashington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, and died of kidney failure at Walter Reed Army Medical Center

The Walter Reed Army Medical Center (WRAMC)known as Walter Reed General Hospital (WRGH) until 1951was the United States Army, U.S. Army's flagship medical center from 1909 to 2011. Located on in the Washington, D.C., District of Columbia, it se ...

on January 24, 1974, aged 79. He was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

. His wife, Mary Gorman Smith (1897-1987) is buried beside him. They had two sons: Albert Jr. and Robert (Colonel, USMA 1944).

Decorations

Here is Major general Smith´s ribbon bar:References

External links

Generals of World War II

{{DEFAULTSORT:Smith, Albert C. 1894 births 1974 deaths United States Army Cavalry Branch personnel People from Warrenton, Virginia United States Army generals United States Military Academy alumni United States Army Infantry Branch personnel United States Army Command and General Staff College alumni United States Army personnel of World War I United States Army Command and General Staff College faculty United States Military Academy faculty Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army) Recipients of the Silver Star Officers of the Legion of Honour Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1939–1945 (France) Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Military personnel from Virginia United States Army generals of World War II