Alan M. Turing on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Alan Mathison Turing (; 23 June 1912 – 7 June 1954) was an English mathematician,

Although

Although

On 4 September 1939, the day after the UK declared war on Germany, Turing reported to Bletchley Park, the wartime station of GC&CS.Copeland, 2006 p. 378. Like all others who came to Bletchley, he was required to sign the

On 4 September 1939, the day after the UK declared war on Germany, Turing reported to Bletchley Park, the wartime station of GC&CS.Copeland, 2006 p. 378. Like all others who came to Bletchley, he was required to sign the

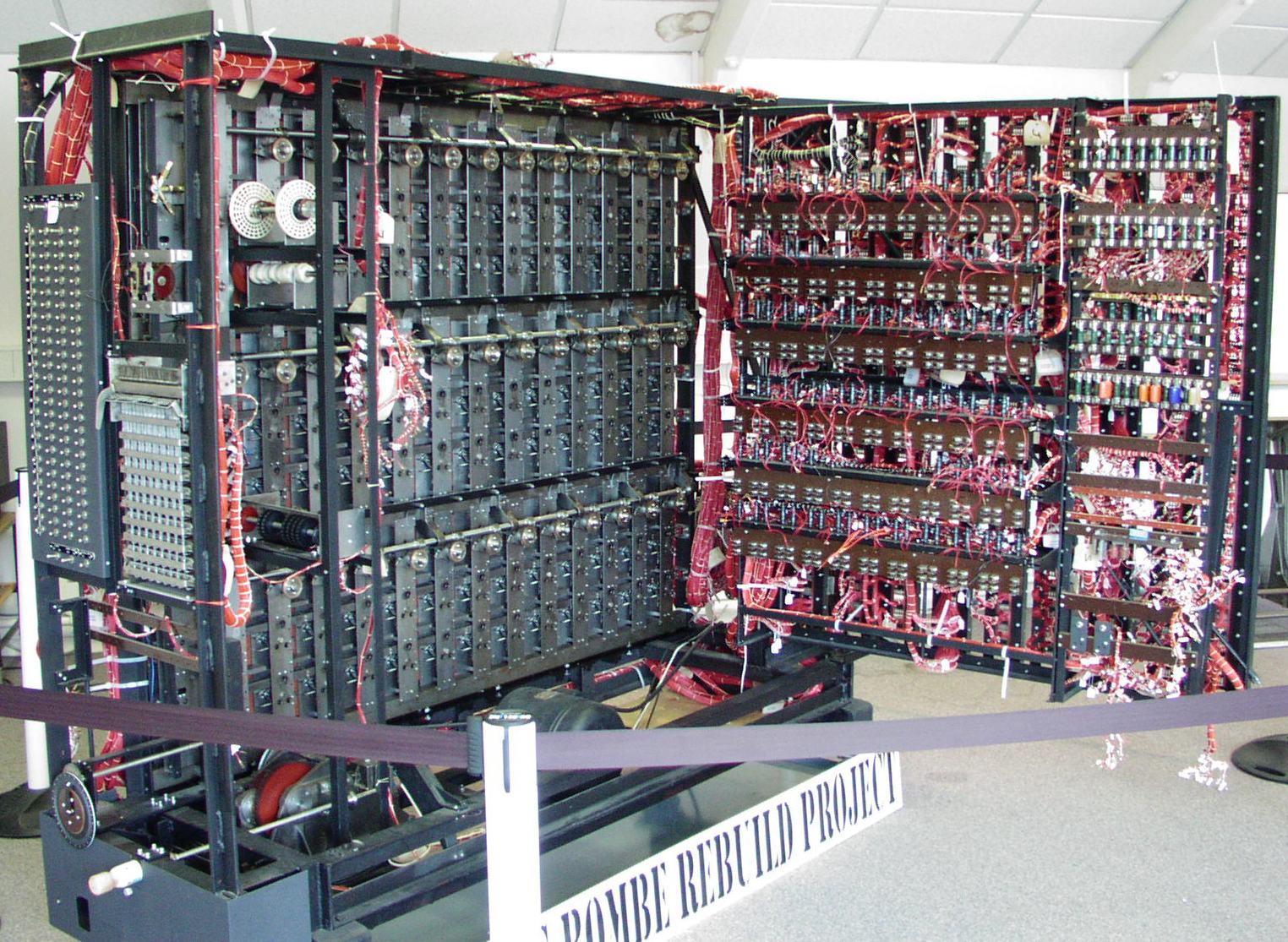

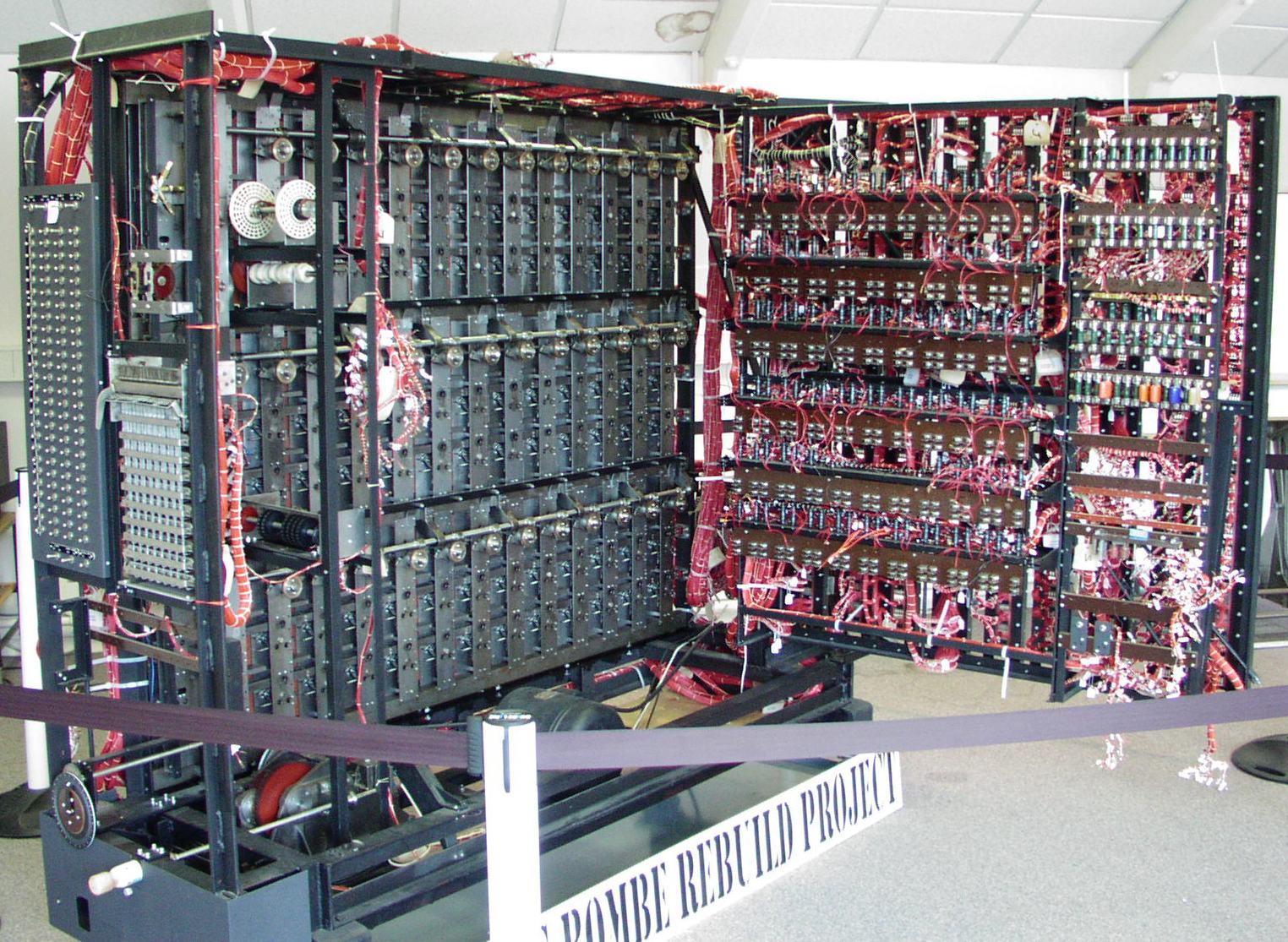

The bombe searched for possible correct settings used for an Enigma message (i.e., rotor order, rotor settings and plugboard settings) using a suitable '' crib'': a fragment of probable

The bombe searched for possible correct settings used for an Enigma message (i.e., rotor order, rotor settings and plugboard settings) using a suitable '' crib'': a fragment of probable

Between 1945 and 1947, Turing lived in

Between 1945 and 1947, Turing lived in

On 8 June 1954, at his house at 43 Adlington Road, Wilmslow, Turing's housekeeper found him dead. He had died the previous day at the age of 41. Cyanide poisoning was established as the cause of death. When his body was discovered, an apple lay half-eaten beside his bed, and although the apple was not tested for cyanide, it was speculated that this was the means by which Turing had consumed a fatal dose. An Inquests in England and Wales, inquest determined that he had committed suicide. Andrew Hodges and another biographer, David Leavitt, have both speculated that Turing was re-enacting a scene from the Walt Disney film ''Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937 film), Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs'' (1937), his favourite fairy tale. Both men noted that (in Leavitt's words) he took "an especially keen pleasure in the scene where the Wicked Queen immerses her apple in the poisonous brew". Turing's remains were cremated at Woking Crematorium on 12 June 1954, and his ashes were scattered in the gardens of the crematorium, just as his father's had been.

Philosopher Jack Copeland has questioned various aspects of the coroner's historical verdict. He suggested an alternative explanation for the cause of Turing's death: the accidental inhalation of cyanide fumes from an apparatus used to electroplating, electroplate gold onto spoons. The potassium cyanide was used to Gold#Commercial chemistry, dissolve the gold. Turing had such an apparatus set up in his tiny spare room. Copeland noted that the autopsy findings were more consistent with inhalation than with ingestion of the poison. Turing also habitually ate an apple before going to bed, and it was not unusual for the apple to be discarded half-eaten. Furthermore, Turing had reportedly borne his legal setbacks and hormone treatment (which had been discontinued a year previously) "with good humour" and had shown no sign of despondency before his death. He even set down a list of tasks that he intended to complete upon returning to his office after the holiday weekend. Turing's mother believed that the ingestion was accidental, resulting from her son's careless storage of laboratory chemicals. Biographer Andrew Hodges theorised that Turing arranged the delivery of the equipment to deliberately allow his mother plausible deniability with regard to any suicide claims.

On 8 June 1954, at his house at 43 Adlington Road, Wilmslow, Turing's housekeeper found him dead. He had died the previous day at the age of 41. Cyanide poisoning was established as the cause of death. When his body was discovered, an apple lay half-eaten beside his bed, and although the apple was not tested for cyanide, it was speculated that this was the means by which Turing had consumed a fatal dose. An Inquests in England and Wales, inquest determined that he had committed suicide. Andrew Hodges and another biographer, David Leavitt, have both speculated that Turing was re-enacting a scene from the Walt Disney film ''Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937 film), Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs'' (1937), his favourite fairy tale. Both men noted that (in Leavitt's words) he took "an especially keen pleasure in the scene where the Wicked Queen immerses her apple in the poisonous brew". Turing's remains were cremated at Woking Crematorium on 12 June 1954, and his ashes were scattered in the gardens of the crematorium, just as his father's had been.

Philosopher Jack Copeland has questioned various aspects of the coroner's historical verdict. He suggested an alternative explanation for the cause of Turing's death: the accidental inhalation of cyanide fumes from an apparatus used to electroplating, electroplate gold onto spoons. The potassium cyanide was used to Gold#Commercial chemistry, dissolve the gold. Turing had such an apparatus set up in his tiny spare room. Copeland noted that the autopsy findings were more consistent with inhalation than with ingestion of the poison. Turing also habitually ate an apple before going to bed, and it was not unusual for the apple to be discarded half-eaten. Furthermore, Turing had reportedly borne his legal setbacks and hormone treatment (which had been discontinued a year previously) "with good humour" and had shown no sign of despondency before his death. He even set down a list of tasks that he intended to complete upon returning to his office after the holiday weekend. Turing's mother believed that the ingestion was accidental, resulting from her son's careless storage of laboratory chemicals. Biographer Andrew Hodges theorised that Turing arranged the delivery of the equipment to deliberately allow his mother plausible deniability with regard to any suicide claims.

It has been suggested that Turing's belief in fortune-telling may have caused his depressed mood. As a youth, Turing had been told by a fortune-teller that he would be a genius. In mid-May 1954, shortly before his death, Turing again decided to consult a fortune-teller during a day-trip to Lytham St Annes, St Annes-on-Sea with the Greenbaum family. According to the Greenbaums' daughter, Barbara:

It has been suggested that Turing's belief in fortune-telling may have caused his depressed mood. As a youth, Turing had been told by a fortune-teller that he would be a genius. In mid-May 1954, shortly before his death, Turing again decided to consult a fortune-teller during a day-trip to Lytham St Annes, St Annes-on-Sea with the Greenbaum family. According to the Greenbaums' daughter, Barbara:

Turing was appointed an officer of the Order of the British Empire in 1946. He was also elected a List of Fellows of the Royal Society elected in 1951, Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1951.

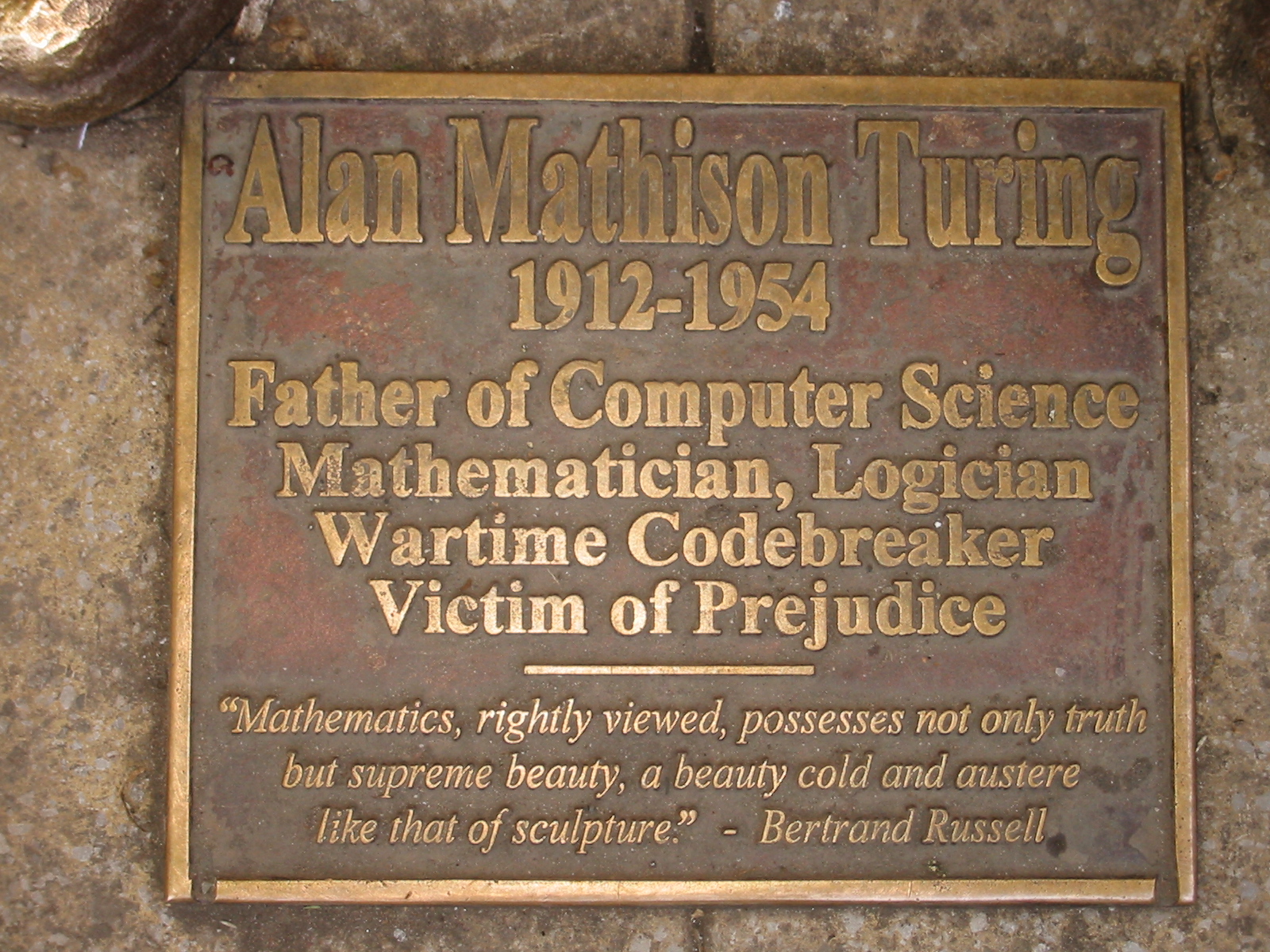

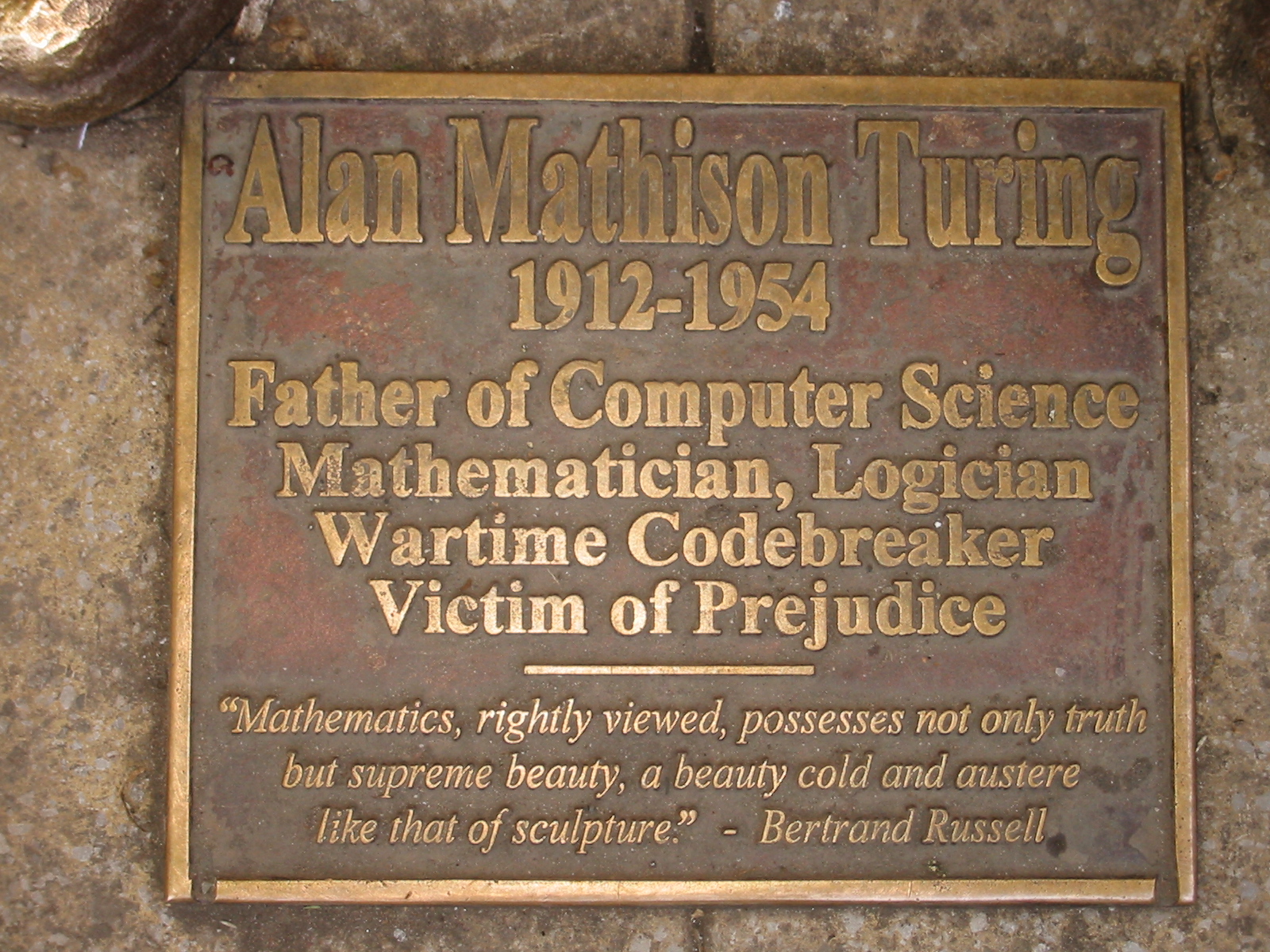

Turing has been honoured in various ways in Manchester, the city where he worked towards the end of his life. In 1994, a stretch of the A6010 road (the Manchester city intermediate ring road) was named "Alan Turing Way". A bridge carrying this road was widened, and carries the name Alan Turing Bridge. A Alan Turing Memorial, statue of Turing was unveiled in Manchester on 23 June 2001 in Sackville Park, between the University of Manchester building on Whitworth Street and Canal Street, Manchester, Canal Street. The memorial statue depicts the "father of computer science" sitting on a bench at a central position in the park. Turing is shown holding an apple. The cast bronze bench carries in relief the text 'Alan Mathison Turing 1912–1954', and the motto 'Founder of Computer Science' as it could appear if encoded by an Enigma machine: 'IEKYF ROMSI ADXUO KVKZC GUBJ'. However, the meaning of the coded message is disputed, as the 'u' in 'computer' matches up with the 'u' in 'ADXUO'. As a letter encoded by an enigma machine cannot appear as itself, the actual message behind the code is uncertain.

Turing was appointed an officer of the Order of the British Empire in 1946. He was also elected a List of Fellows of the Royal Society elected in 1951, Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1951.

Turing has been honoured in various ways in Manchester, the city where he worked towards the end of his life. In 1994, a stretch of the A6010 road (the Manchester city intermediate ring road) was named "Alan Turing Way". A bridge carrying this road was widened, and carries the name Alan Turing Bridge. A Alan Turing Memorial, statue of Turing was unveiled in Manchester on 23 June 2001 in Sackville Park, between the University of Manchester building on Whitworth Street and Canal Street, Manchester, Canal Street. The memorial statue depicts the "father of computer science" sitting on a bench at a central position in the park. Turing is shown holding an apple. The cast bronze bench carries in relief the text 'Alan Mathison Turing 1912–1954', and the motto 'Founder of Computer Science' as it could appear if encoded by an Enigma machine: 'IEKYF ROMSI ADXUO KVKZC GUBJ'. However, the meaning of the coded message is disputed, as the 'u' in 'computer' matches up with the 'u' in 'ADXUO'. As a letter encoded by an enigma machine cannot appear as itself, the actual message behind the code is uncertain.

A plaque at the statue's feet reads 'Father of computer science, mathematician, logician, wartime codebreaker, victim of prejudice'. There is also a Bertrand Russell quotation: "Mathematics, rightly viewed, possesses not only truth, but supreme beauty—a beauty cold and austere, like that of sculpture." The sculptor buried his own old Amstrad computer under the plinth as a tribute to "the godfather of all modern computers".

In 1999, ''Time (magazine), Time'' magazine named Turing as one of the Time 100: The Most Important People of the Century, 100 Most Important People of the 20th century and stated, "The fact remains that everyone who taps at a keyboard, opening a spreadsheet or a word-processing program, is working on an incarnation of a Turing machine."

A blue plaque was unveiled at King's College, Cambridge on the centenary of his birth on 23 June 2012 and is now installed at the college's Keynes Building on King's Parade. A high steel sculpture, designed in Turing's honour by Sir Antony Gormley, is planned to be installed at King's College, but Historic England deemed the sculpture too abstract for the setting, saying that it "would result in harm, of a less than substantial nature, to the significance of the listed buildings and landscape, and by extension the conservation area."

On 25 March 2021, the Bank of England publicly unveiled the design for a new Bank of England £50 note, £50 note, featuring Turing's portrait, before its official issue on 23 June, Turing's birthday. Turing was selected as the new face of the note in 2019 following a public nomination process.

A plaque at the statue's feet reads 'Father of computer science, mathematician, logician, wartime codebreaker, victim of prejudice'. There is also a Bertrand Russell quotation: "Mathematics, rightly viewed, possesses not only truth, but supreme beauty—a beauty cold and austere, like that of sculpture." The sculptor buried his own old Amstrad computer under the plinth as a tribute to "the godfather of all modern computers".

In 1999, ''Time (magazine), Time'' magazine named Turing as one of the Time 100: The Most Important People of the Century, 100 Most Important People of the 20th century and stated, "The fact remains that everyone who taps at a keyboard, opening a spreadsheet or a word-processing program, is working on an incarnation of a Turing machine."

A blue plaque was unveiled at King's College, Cambridge on the centenary of his birth on 23 June 2012 and is now installed at the college's Keynes Building on King's Parade. A high steel sculpture, designed in Turing's honour by Sir Antony Gormley, is planned to be installed at King's College, but Historic England deemed the sculpture too abstract for the setting, saying that it "would result in harm, of a less than substantial nature, to the significance of the listed buildings and landscape, and by extension the conservation area."

On 25 March 2021, the Bank of England publicly unveiled the design for a new Bank of England £50 note, £50 note, featuring Turing's portrait, before its official issue on 23 June, Turing's birthday. Turing was selected as the new face of the note in 2019 following a public nomination process.

''Konrad Zuse und die Schweiz. Wer hat den Computer erfunden? Charles Babbage, Alan Turing und John von Neumann''

Oldenbourg Verlag, München 2012, XXVI, 224 Seiten, * * * * * * * * * ** in * * * * * * * * * * * * * Petzold, Charles (2008). "The Annotated Turing: A Guided Tour through Alan Turing's Historic Paper on Computability and the Turing Machine". Indianapolis: Wiley Publishing. * Smith, Roger (1997). ''Fontana History of the Human Sciences''. London: Fontana. * * Weizenbaum, Joseph (1976). ''Computer Power and Human Reason''. London: W.H. Freeman. * and * Turing's mother, who survived him by many years, wrote this 157-page biography of her son, glorifying his life. It was published in 1959, and so could not cover his war work. Scarcely 300 copies were sold (Sara Turing to Lyn Newman, 1967, Library of St John's College, Cambridge). The six-page foreword by Lyn Irvine includes reminiscences and is more frequently quoted. It was re-published by Cambridge University Press in 2012, to honour the centenary of his birth, and included a new foreword by Martin Davis (mathematician), Martin Davis, as well as a never-before-published memoir by Turing's older brother John F. Turing. * This 1986 Hugh Whitemore play tells the story of Turing's life and death. In the original West End and Broadway runs, Derek Jacobi played Turing and he recreated the role in a 1997 television film based on the play made jointly by the BBC and WGBH-TV, WGBH, Boston. The play is published by Amber Lane Press, Oxford, ASIN: B000B7TM0Q * Williams, Michael R. (1985) ''A History of Computing Technology'', Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, *

Oral history interview with Nicholas C. Metropolis

Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota. Metropolis was the first director of computing services at Los Alamos National Laboratory; topics include the relationship between Turing and

How Alan Turing Cracked The Enigma Code

Imperial War Museums

Alan Turing Year

CiE 2012: Turing Centenary Conference

Science in the Making

Alan Turing's papers in the Royal Society's archives

Alan Turing

site maintained by Andrew Hodges including

short biography

AlanTuring.net – Turing Archive for the History of Computing

by Jack Copeland

The Turing Archive

nbsp;– contains scans of some unpublished documents and material from the King's College, Cambridge archive

Alan Turing Papers

– University of Manchester Library, Manchester *

Sherborne School Archives

– holds papers relating to Turing's time at Sherborne School

Alan Turing plaques

recorded on openplaques.org

Alan Turing

archive on New Scientist {{DEFAULTSORT:Turing, Alan Mathison Alan Turing, 1912 births 1954 suicides 20th-century English mathematicians 20th-century atheists 20th-century English philosophers Academics of the University of Manchester Academics of the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology Alumni of King's College, Cambridge Artificial intelligence researchers Bayesian statisticians Bletchley Park people British anti-fascists British cryptographers British people of World War II Computability theorists Computer designers English atheists English computer scientists English inventors English logicians English male long-distance runners English people of Irish descent English people of Scottish descent Fellows of King's College, Cambridge Fellows of the Royal Society Former Protestants Foreign Office personnel of World War II Gay academics Gay scientists Gay sportsmen GCHQ people History of artificial intelligence History of computing in the United Kingdom LGBT-related suicides LGBT mathematicians LGBT philosophers LGBT scientists from the United Kingdom LGBT sportspeople from England LGBT track and field athletes Officers of the Order of the British Empire People educated at Sherborne School People from Maida Vale People from Wilmslow People convicted for homosexuality in the United Kingdom People who have received posthumous pardons Princeton University alumni Recipients of British royal pardons Theoretical biologists Theoretical computer scientists Deaths by cyanide poisoning Suicides by cyanide poisoning Suicides in England

computer scientist

A computer scientist is a person who is trained in the academic study of computer science.

Computer scientists typically work on the theoretical side of computation, as opposed to the hardware side on which computer engineers mainly focus ( ...

, logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premis ...

ian, cryptanalyst

Cryptanalysis (from the Greek ''kryptós'', "hidden", and ''analýein'', "to analyze") refers to the process of analyzing information systems in order to understand hidden aspects of the systems. Cryptanalysis is used to breach cryptographic se ...

, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. Turing was highly influential in the development of theoretical computer science

Theoretical computer science (TCS) is a subset of general computer science and mathematics that focuses on mathematical aspects of computer science such as the theory of computation, lambda calculus, and type theory.

It is difficult to circumsc ...

, providing a formalisation of the concepts of algorithm

In mathematics and computer science, an algorithm () is a finite sequence of rigorous instructions, typically used to solve a class of specific problems or to perform a computation. Algorithms are used as specifications for performing ...

and computation

Computation is any type of arithmetic or non-arithmetic calculation that follows a well-defined model (e.g., an algorithm).

Mechanical or electronic devices (or, historically, people) that perform computations are known as '' computers''. An esp ...

with the Turing machine

A Turing machine is a mathematical model of computation describing an abstract machine that manipulates symbols on a strip of tape according to a table of rules. Despite the model's simplicity, it is capable of implementing any computer algor ...

, which can be considered a model of a general-purpose computer

A computer is a machine that can be programmed to automatically carry out sequences of arithmetic or logical operations (computation). Modern digital electronic computers can perform generic sets of operations known as programs. These progr ...

. He is widely considered to be the father of theoretical computer science and artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence (AI) is intelligence—perceiving, synthesizing, and inferring information—demonstrated by machines, as opposed to intelligence displayed by animals and humans. Example tasks in which this is done include speech r ...

.

Born in Maida Vale

Maida Vale ( ) is an affluent residential district consisting of the northern part of Paddington in West London, west of St John's Wood and south of Kilburn. It is also the name of its main road, on the continuous Edgware Road. Maida Vale is ...

, London, Turing was raised in southern England

Southern England, or the South of England, also known as the South, is an area of England consisting of its southernmost part, with cultural, economic and political differences from the Midlands and the North. Officially, the area includes G ...

. He graduated at King's College, Cambridge

King's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Formally The King's College of Our Lady and Saint Nicholas in Cambridge, the college lies beside the River Cam and faces out onto King's Parade in the centre of the cit ...

, with a degree in mathematics. Whilst he was a fellow

A fellow is a concept whose exact meaning depends on context.

In learned or professional societies, it refers to a privileged member who is specially elected in recognition of their work and achievements.

Within the context of higher education ...

at Cambridge, he published a proof demonstrating that some purely mathematical yes–no questions can never be answered by computation and defined a Turing machine

A Turing machine is a mathematical model of computation describing an abstract machine that manipulates symbols on a strip of tape according to a table of rules. Despite the model's simplicity, it is capable of implementing any computer algor ...

, and went on to prove that the halting problem

In computability theory, the halting problem is the problem of determining, from a description of an arbitrary computer program and an input, whether the program will finish running, or continue to run forever. Alan Turing proved in 1936 that a ...

for Turing machines is undecidable. In 1938, he obtained his PhD from the Department of Mathematics at Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the n ...

. During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, Turing worked for the Government Code and Cypher School

Government Communications Headquarters, commonly known as GCHQ, is an intelligence and security organisation responsible for providing signals intelligence (SIGINT) and information assurance (IA) to the government and armed forces of the Unit ...

(GC&CS) at Bletchley Park

Bletchley Park is an English country house and estate in Bletchley, Milton Keynes (Buckinghamshire) that became the principal centre of Allied code-breaking during the Second World War. The mansion was constructed during the years following ...

, Britain's codebreaking

Cryptanalysis (from the Greek ''kryptós'', "hidden", and ''analýein'', "to analyze") refers to the process of analyzing information systems in order to understand hidden aspects of the systems. Cryptanalysis is used to breach cryptographic se ...

centre that produced Ultra

adopted by British military intelligence in June 1941 for wartime signals intelligence obtained by breaking high-level encrypted enemy radio and teleprinter communications at the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park ...

intelligence. For a time he led Hut 8

Hut 8 was a section in the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park (the British World War II codebreaking station, located in Buckinghamshire) tasked with solving German naval (Kriegsmarine) Enigma messages. The section was l ...

, the section that was responsible for German naval cryptanalysis. Here, he devised a number of techniques for speeding the breaking of German cipher

In cryptography, a cipher (or cypher) is an algorithm for performing encryption or decryption—a series of well-defined steps that can be followed as a procedure. An alternative, less common term is ''encipherment''. To encipher or encode i ...

s, including improvements to the pre-war Polish bomba method, an electromechanical

In engineering, electromechanics combines processes and procedures drawn from electrical engineering and mechanical engineering. Electromechanics focuses on the interaction of electrical and mechanical systems as a whole and how the two system ...

machine that could find settings for the Enigma machine. Turing played a crucial role in cracking intercepted coded messages that enabled the Allies to defeat the Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

in many crucial engagements, including the Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allied naval blocka ...

.

After the war, Turing worked at the National Physical Laboratory, where he designed the Automatic Computing Engine

The Automatic Computing Engine (ACE) was a British early electronic serial stored-program computer designed by Alan Turing. It was based on the earlier Pilot ACE. It led to the MOSAIC computer, the Bendix G-15, and other computers.

Ba ...

(ACE), one of the first designs for a stored-program computer. In 1948, Turing joined Max Newman

Maxwell Herman Alexander Newman, FRS, (7 February 1897 – 22 February 1984), generally known as Max Newman, was a British mathematician and codebreaker. His work in World War II led to the construction of Colossus, the world's first operatio ...

's Computing Machine Laboratory, at the Victoria University of Manchester

The Victoria University of Manchester, usually referred to as simply the University of Manchester, was a university in Manchester, England. It was founded in 1851 as Owens College. In 1880, the college joined the federal Victoria University. Afte ...

, where he helped develop the Manchester computers

The Manchester computers were an innovative series of stored-program electronic computers developed during the 30-year period between 1947 and 1977 by a small team at the University of Manchester, under the leadership of Tom Kilburn. They inclu ...

and became interested in mathematical biology

Mathematical and theoretical biology, or biomathematics, is a branch of biology which employs theoretical analysis, mathematical models and abstractions of the living organisms to investigate the principles that govern the structure, development a ...

. He wrote a paper on the chemical basis of morphogenesis

Morphogenesis (from the Greek ''morphê'' shape and ''genesis'' creation, literally "the generation of form") is the biological process that causes a cell, tissue or organism to develop its shape. It is one of three fundamental aspects of deve ...

and predicted oscillating

Oscillation is the repetitive or periodic variation, typically in time, of some measure about a central value (often a point of equilibrium) or between two or more different states. Familiar examples of oscillation include a swinging pendulum ...

chemical reaction

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the chemical transformation of one set of chemical substances to another. Classically, chemical reactions encompass changes that only involve the positions of electrons in the forming and break ...

s such as the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction

A Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction, or BZ reaction, is one of a class of reactions that serve as a classical example of non-equilibrium thermodynamics, resulting in the establishment of a nonlinear chemical oscillator. The only common element i ...

, first observed in the 1960s. Despite these accomplishments, Turing was never fully recognised in Britain during his lifetime because much of his work was covered by the Official Secrets Act

An Official Secrets Act (OSA) is legislation that provides for the protection of state secrets and official information, mainly related to national security but in unrevised form (based on the UK Official Secrets Act 1911) can include all info ...

.

Turing was prosecuted in 1952 for homosexual acts

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to peop ...

. He accepted hormone treatment with DES, a procedure commonly referred to as chemical castration

Chemical castration is castration via anaphrodisiac drugs, whether to reduce libido and sexual activity, to treat cancer, or otherwise. Unlike surgical castration, where the gonads are removed through an incision in the body,

, as an alternative to prison. Turing died on 7 June 1954, 16 days before his 42nd birthday, from cyanide poisoning

Cyanide poisoning is poisoning that results from exposure to any of a number of forms of cyanide. Early symptoms include headache, dizziness, fast heart rate, shortness of breath, and vomiting. This phase may then be followed by seizures, s ...

. An inquest determined his death as a suicide, but it has been noted that the known evidence is also consistent with accidental poisoning.

Following a public campaign in 2009, the British Prime Minister Gordon Brown

James Gordon Brown (born 20 February 1951) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 2007 to 2010. He previously served as Chance ...

made an official public apology on behalf of the British government for "the appalling way uringwas treated". Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

granted a posthumous pardon in 2013. The term "Alan Turing law

The "Alan Turing law" is an informal term for the law in the United Kingdom, contained in the Policing and Crime Act 2017, which serves as an amnesty law to pardon men who were cautioned or convicted under historical legislation that outla ...

" is now used informally to refer to a 2017 law in the United Kingdom that retroactively pardoned men cautioned or convicted under historical legislation that outlawed homosexual acts.

Turing has an extensive legacy with statues of him and many things named after him, including an annual award for computer science innovations. He appears on the current Bank of England £50 note, which was released on 23 June 2021, to coincide with his birthday. A 2019 BBC series, as voted by the audience, named him the greatest person of the 20th century.

Early life and education

Family

Turing was born inMaida Vale

Maida Vale ( ) is an affluent residential district consisting of the northern part of Paddington in West London, west of St John's Wood and south of Kilburn. It is also the name of its main road, on the continuous Edgware Road. Maida Vale is ...

, London, while his father, Julius Mathison Turing (1873–1947), was on leave from his position with the Indian Civil Service

The Indian Civil Service (ICS), officially known as the Imperial Civil Service, was the higher civil service of the British Empire in India during British rule in the period between 1858 and 1947.

Its members ruled over more than 300 million ...

(ICS) of the British Raj government at Chatrapur

Chhatrapur (also spelt as Chhatarpur) is a town and a Notified Area Council since 1955 in Ganjam district in the state of Odisha, India. It is the district headquarters town of Ganjam district. Chhatrapur is a Tehsil / Block (CD) in the Ganja ...

, then in the Madras Presidency

The Madras Presidency, or the Presidency of Fort St. George, also known as Madras Province, was an administrative subdivision (presidency) of British India. At its greatest extent, the presidency included most of southern India, including th ...

and presently in Odisha

Odisha (English: , ), formerly Orissa ( the official name until 2011), is an Indian state located in Eastern India. It is the 8th largest state by area, and the 11th largest by population. The state has the third largest population of Sc ...

state, in India. Turing's father was the son of a clergyman, the Rev. John Robert Turing, from a Scottish family of merchants that had been based in the Netherlands and included a baronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14th ...

. Turing's mother, Julius's wife, was Ethel Sara Turing (; 1881–1976), daughter of Edward Waller Stoney, chief engineer of the Madras Railways. The Stoneys were a Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

Anglo-Irish gentry

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest c ...

family from both County Tipperary

County Tipperary ( ga, Contae Thiobraid Árann) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster and the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region. The county is named afte ...

and County Longford

County Longford ( gle, Contae an Longfoirt) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Leinster. It is named after the town of Longford. Longford County Council is the local authority for the county. The population of the county was ...

, while Ethel herself had spent much of her childhood in County Clare

County Clare ( ga, Contae an Chláir) is a county in Ireland, in the Southern Region and the province of Munster, bordered on the west by the Atlantic Ocean. Clare County Council is the local authority. The county had a population of 118,817 ...

. Julius and Ethel married on 1 October 1907 at Batholomew's church on Clyde Road, in Dublin.

Julius's work with the ICS brought the family to British India, where his grandfather had been a general in the Bengal Army

The Bengal Army was the army of the Bengal Presidency, one of the three presidencies of British India within the British Empire.

The presidency armies, like the presidencies themselves, belonged to the East India Company (EIC) until the Govern ...

. However, both Julius and Ethel wanted their children to be brought up in Britain, so they moved to Maida Vale

Maida Vale ( ) is an affluent residential district consisting of the northern part of Paddington in West London, west of St John's Wood and south of Kilburn. It is also the name of its main road, on the continuous Edgware Road. Maida Vale is ...

, London, where Alan Turing was born on 23 June 1912, as recorded by a blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom and elsewhere to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving as a historical marker. The term i ...

on the outside of the house of his birth, later the Colonnade Hotel Not to be confused with the Colonnade Hotel (Seattle) in Washington

The Colonnade Hotel (previously known as The Esplanade hotel) is a 4-star London hotel with 43 rooms, of which three are suites. The hotel is located opposite Warwick Avenue U ...

. Turing had an elder brother, John (the father of Sir John Dermot Turing, 12th Baronet of the Turing baronets).

Turing's father's civil service commission was still active and during Turing's childhood years, his parents travelled between Hastings

Hastings () is a large seaside town and borough in East Sussex on the south coast of England,

east to the county town of Lewes and south east of London. The town gives its name to the Battle of Hastings, which took place to the north-west a ...

in the United Kingdom and India, leaving their two sons to stay with a retired Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

couple. At Hastings, Turing stayed at Baston Lodge, Upper Maze Hill, St Leonards-on-Sea

St Leonards-on-Sea (commonly known as St Leonards) is a town and seaside resort in the Borough of Hastings in East Sussex, England. It has been part of the borough since the late 19th century and lies to the west of central Hastings. The origina ...

, now marked with a blue plaque. The plaque was unveiled on 23 June 2012, the centenary of Turing's birth.

Very early in life, Turing showed signs of the genius that he was later to display prominently. His parents purchased a house in Guildford

Guildford ()

is a town in west Surrey, around southwest of central London. As of the 2011 census, the town has a population of about 77,000 and is the seat of the wider Borough of Guildford, which had around inhabitants in . The name "Guildf ...

in 1927, and Turing lived there during school holidays. The location is also marked with a blue plaque.

School

Turing's parents enrolled him at St Michael's, a primary school at 20 Charles Road,St Leonards-on-Sea

St Leonards-on-Sea (commonly known as St Leonards) is a town and seaside resort in the Borough of Hastings in East Sussex, England. It has been part of the borough since the late 19th century and lies to the west of central Hastings. The origina ...

, from the age of six to nine. The headmistress recognised his talent, noting that she has "...had clever boys and hardworking boys, but Alan is a genius."

Between January 1922 and 1926, Turing was educated at Hazelhurst Preparatory School, an independent school in the village of Frant

Frant is a village and civil parish in the Wealden District of East Sussex, England, on the Kentish border about three miles (5 km) south of Royal Tunbridge Wells.

When the iron industry was at its height, much of the village was owne ...

in Sussex (now East Sussex

East Sussex is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South East England on the English Channel coast. It is bordered by Kent to the north and east, West Sussex to the west, and Surrey to the north-west. The largest settlement in East ...

). In 1926, at the age of 13, he went on to Sherborne School

(God and My Right)

, established = 705 by Aldhelm,

re-founded by King Edward VI 1550

, closed =

, type = Public school Independent, boarding school

, religion = Church of England

, president =

, chair_label = Chairman of the governors ...

, a boarding independent school in the market town of Sherborne

Sherborne is a market town and civil parish in north west Dorset, in South West England. It is sited on the River Yeo, on the edge of the Blackmore Vale, east of Yeovil. The parish includes the hamlets of Nether Coombe and Lower Clatcombe. T ...

in Dorset, where he boarded at Westcott House. The first day of term coincided with the 1926 General Strike

The 1926 general strike in the United Kingdom was a general strike that lasted nine days, from 4 to 12 May 1926. It was called by the General Council of the Trades Union Congress (TUC) in an unsuccessful attempt to force the British governmen ...

, in Britain, but Turing was so determined to attend that he rode his bicycle unaccompanied from Southampton

Southampton () is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire, S ...

to Sherborne, stopping overnight at an inn.

Turing's natural inclination towards mathematics and science did not earn him respect from some of the teachers at Sherborne, whose definition of education placed more emphasis on the classics. His headmaster wrote to his parents: "I hope he will not fall between two stools. If he is to stay at public school, he must aim at becoming ''educated''. If he is to be solely a ''Scientific Specialist'', he is wasting his time at a public school". Despite this, Turing continued to show remarkable ability in the studies he loved, solving advanced problems in 1927 without having studied even elementary calculus

Calculus, originally called infinitesimal calculus or "the calculus of infinitesimals", is the mathematics, mathematical study of continuous change, in the same way that geometry is the study of shape, and algebra is the study of generalizati ...

. In 1928, aged 16, Turing encountered Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theor ...

's work; not only did he grasp it, but it is possible that he managed to deduce Einstein's questioning of Newton's laws of motion

Newton's laws of motion are three basic laws of classical mechanics that describe the relationship between the motion of an object and the forces acting on it. These laws can be paraphrased as follows:

# A body remains at rest, or in moti ...

from a text in which this was never made explicit.

Christopher Morcom

At Sherborne, Turing formed a significant friendship with fellow pupil Christopher Collan Morcom (13 July 1911 – 13 February 1930), who has been described as Turing's "first love". Their relationship provided inspiration in Turing's future endeavours, but it was cut short by Morcom's death, in February 1930, from complications ofbovine tuberculosis

Bovines ( subfamily Bovinae) comprise a diverse group of 10 genera of medium to large-sized ungulates, including cattle, bison, African buffalo, water buffalos, and the four-horned and spiral-horned antelopes. The evolutionary relationship betw ...

, contracted after drinking infected cow's milk some years previously.

The event caused Turing great sorrow. He coped with his grief by working that much harder on the topics of science and mathematics that he had shared with Morcom. In a letter to Morcom's mother, Frances Isobel Morcom (née Swan), Turing wrote:

Turing's relationship with Morcom's mother continued long after Morcom's death, with her sending gifts to Turing, and him sending letters, typically on Morcom's birthday. A day before the third anniversary of Morcom's death (13 February 1933), he wrote to Mrs. Morcom:

Some have speculated that Morcom's death was the cause of Turing's atheism

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

and materialism

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism which holds matter to be the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical material ...

. Apparently, at this point in his life he still believed in such concepts as a spirit, independent of the body and surviving death. In a later letter, also written to Morcom's mother, Turing wrote:

University and work on computability

After Sherborne, Turing studied as an undergraduate from 1931 to 1934 atKing's College, Cambridge

King's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Formally The King's College of Our Lady and Saint Nicholas in Cambridge, the college lies beside the River Cam and faces out onto King's Parade in the centre of the cit ...

, where he was awarded first-class honours in mathematics. In 1935, at the age of 22, he was elected a Fellow

A fellow is a concept whose exact meaning depends on context.

In learned or professional societies, it refers to a privileged member who is specially elected in recognition of their work and achievements.

Within the context of higher education ...

of King's College on the strength of a dissertation in which he proved a version of the central limit theorem

In probability theory, the central limit theorem (CLT) establishes that, in many situations, when independent random variables are summed up, their properly normalized sum tends toward a normal distribution even if the original variables thems ...

. Unknown to Turing, this version of the theorem had already been proven, in 1922, by Jarl Waldemar Lindeberg

Jarl Waldemar Lindeberg (4 August 1876, Helsinki – 24 December 1932, Helsinki) was a Finnish mathematician known for work on the central limit theorem.

Life and work

Lindeberg was son of a teacher at the Helsinki Polytechnical Institute and a ...

. Despite this, the committee found Turing's methods original and so regarded the work worthy of consideration for the fellowship. Abram Besicovitch

Abram Samoilovitch Besicovitch (or Besikovitch) (russian: link=no, Абра́м Само́йлович Безико́вич; 23 January 1891 – 2 November 1970) was a Russian mathematician, who worked mainly in England. He was born in Berdyansk ...

's report for the committee went so far as to say that if Turing's work had been published before Lindeberg's, it would have been "an important event in the mathematical literature of that year".

In 1936, Turing published his paper "On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem

Turing's proof is a proof by Alan Turing, first published in January 1937 with the title "On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the ". It was the second proof (after Church's theorem) of the negation of Hilbert's ; that is, the conjecture ...

". It was published in the ''Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society'' journal in two parts, the first on 30 November and the second on 23 December. In this paper, Turing reformulated Kurt Gödel

Kurt Friedrich Gödel ( , ; April 28, 1906 – January 14, 1978) was a logician, mathematician, and philosopher. Considered along with Aristotle and Gottlob Frege to be one of the most significant logicians in history, Gödel had an imm ...

's 1931 results on the limits of proof and computation, replacing Gödel's universal arithmetic-based formal language with the formal and simple hypothetical devices that became known as Turing machine

A Turing machine is a mathematical model of computation describing an abstract machine that manipulates symbols on a strip of tape according to a table of rules. Despite the model's simplicity, it is capable of implementing any computer algor ...

s. The ''Entscheidungsproblem

In mathematics and computer science, the ' (, ) is a challenge posed by David Hilbert and Wilhelm Ackermann in 1928. The problem asks for an algorithm that considers, as input, a statement and answers "Yes" or "No" according to whether the stat ...

'' (decision problem) was originally posed by German mathematician David Hilbert in 1928. Turing proved that his "universal computing machine" would be capable of performing any conceivable mathematical computation if it were representable as an algorithm

In mathematics and computer science, an algorithm () is a finite sequence of rigorous instructions, typically used to solve a class of specific problems or to perform a computation. Algorithms are used as specifications for performing ...

. He went on to prove that there was no solution to the ''decision problem'' by first showing that the halting problem

In computability theory, the halting problem is the problem of determining, from a description of an arbitrary computer program and an input, whether the program will finish running, or continue to run forever. Alan Turing proved in 1936 that a ...

for Turing machines is undecidable: it is not possible to decide algorithmically whether a Turing machine will ever halt. This paper has been called "easily the most influential math paper in history".

Although

Although Turing's proof

Turing's proof is a proof by Alan Turing, first published in January 1937 with the title "On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the ". It was the second proof (after Church's theorem) of the negation of Hilbert's ; that is, the conjecture ...

was published shortly after Alonzo Church

Alonzo Church (June 14, 1903 – August 11, 1995) was an American mathematician, computer scientist, logician, philosopher, professor and editor who made major contributions to mathematical logic and the foundations of theoretical computer scie ...

's equivalent proof using his lambda calculus

Lambda calculus (also written as ''λ''-calculus) is a formal system in mathematical logic for expressing computation based on function abstraction and application using variable binding and substitution. It is a universal model of computation t ...

, Turing's approach is considerably more accessible and intuitive than Church's. It also included a notion of a 'Universal Machine' (now known as a universal Turing machine

In computer science, a universal Turing machine (UTM) is a Turing machine that can simulate an arbitrary Turing machine on arbitrary input. The universal machine essentially achieves this by reading both the description of the machine to be simu ...

), with the idea that such a machine could perform the tasks of any other computation machine (as indeed could Church's lambda calculus). According to the Church–Turing thesis

In computability theory, the Church–Turing thesis (also known as computability thesis, the Turing–Church thesis, the Church–Turing conjecture, Church's thesis, Church's conjecture, and Turing's thesis) is a thesis about the nature of co ...

, Turing machines and the lambda calculus are capable of computing anything that is computable. John von Neumann

John von Neumann (; hu, Neumann János Lajos, ; December 28, 1903 – February 8, 1957) was a Hungarian-American mathematician, physicist, computer scientist, engineer and polymath. He was regarded as having perhaps the widest cove ...

acknowledged that the central concept of the modern computer was due to Turing's paper. To this day, Turing machines are a central object of study in theory of computation

In theoretical computer science and mathematics, the theory of computation is the branch that deals with what problems can be solved on a model of computation, using an algorithm, how efficiently they can be solved or to what degree (e.g., ...

.

From September 1936 to July 1938, Turing spent most of his time studying under Church at Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the n ...

, in the second year as a Jane Eliza Procter Visiting Fellow. In addition to his purely mathematical work, he studied cryptology and also built three of four stages of an electro-mechanical binary multiplier. In June 1938, he obtained his PhD from the Department of Mathematics at Princeton; his dissertation, '' Systems of Logic Based on Ordinals'', introduced the concept of ordinal logic and the notion of relative computing, in which Turing machines are augmented with so-called oracles

An oracle is a person or agency considered to provide wise and insightful counsel or prophetic predictions, most notably including precognition of the future, inspired by deities. As such, it is a form of divination.

Description

The word '' ...

, allowing the study of problems that cannot be solved by Turing machines. John von Neumann wanted to hire him as his postdoctoral assistant, but he went back to the United Kingdom.

Career and research

When Turing returned to Cambridge, he attended lectures given in 1939 byLudwig Wittgenstein

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein ( ; ; 26 April 1889 – 29 April 1951) was an Austrian- British philosopher who worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language. He is cons ...

about the foundations of mathematics

Foundations of mathematics is the study of the philosophical and logical and/or algorithmic basis of mathematics, or, in a broader sense, the mathematical investigation of what underlies the philosophical theories concerning the nature of mathe ...

. The lectures have been reconstructed verbatim, including interjections from Turing and other students, from students' notes. Turing and Wittgenstein argued and disagreed, with Turing defending formalism

Formalism may refer to:

* Form (disambiguation)

* Formal (disambiguation)

* Legal formalism, legal positivist view that the substantive justice of a law is a question for the legislature rather than the judiciary

* Formalism (linguistics)

* Scien ...

and Wittgenstein propounding his view that mathematics does not discover any absolute truths, but rather invents them.

Cryptanalysis

During the Second World War, Turing was a leading participant in the breaking of German ciphers atBletchley Park

Bletchley Park is an English country house and estate in Bletchley, Milton Keynes (Buckinghamshire) that became the principal centre of Allied code-breaking during the Second World War. The mansion was constructed during the years following ...

. The historian and wartime codebreaker Asa Briggs

Asa Briggs, Baron Briggs (7 May 1921 – 15 March 2016) was an English historian. He was a leading specialist on the Victorian era, and the foremost historian of broadcasting in Britain. Briggs achieved international recognition during his lon ...

has said, "You needed exceptional talent, you needed genius at Bletchley and Turing's was that genius."

From September 1938, Turing worked part-time with the Government Code and Cypher School

Government Communications Headquarters, commonly known as GCHQ, is an intelligence and security organisation responsible for providing signals intelligence (SIGINT) and information assurance (IA) to the government and armed forces of the Unit ...

(GC&CS), the British codebreaking organisation. He concentrated on cryptanalysis of the Enigma cipher machine used by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, together with Dilly Knox

Alfred Dillwyn "Dilly" Knox, CMG (23 July 1884 – 27 February 1943) was a British classics scholar and papyrologist at King's College, Cambridge and a codebreaker. As a member of the Room 40 codebreaking unit he helped decrypt the Zimmerm ...

, a senior GC&CS codebreaker. Soon after the July 1939 meeting near Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is official ...

at which the Polish Cipher Bureau gave the British and French details of the wiring of Enigma machine's rotors and their method of decrypting Enigma machine's messages, Turing and Knox developed a broader solution. The Polish method relied on an insecure indicator

Indicator may refer to:

Biology

* Environmental indicator of environmental health (pressures, conditions and responses)

* Ecological indicator of ecosystem health (ecological processes)

* Health indicator, which is used to describe the health o ...

procedure that the Germans were likely to change, which they in fact did in May 1940. Turing's approach was more general, using crib-based decryption for which he produced the functional specification of the bombe

The bombe () was an electro-mechanical device used by British cryptologists to help decipher German Enigma-machine-encrypted secret messages during World War II. The US Navy and US Army later produced their own machines to the same functiona ...

(an improvement on the Polish Bomba).

On 4 September 1939, the day after the UK declared war on Germany, Turing reported to Bletchley Park, the wartime station of GC&CS.Copeland, 2006 p. 378. Like all others who came to Bletchley, he was required to sign the

On 4 September 1939, the day after the UK declared war on Germany, Turing reported to Bletchley Park, the wartime station of GC&CS.Copeland, 2006 p. 378. Like all others who came to Bletchley, he was required to sign the Official Secrets Act

An Official Secrets Act (OSA) is legislation that provides for the protection of state secrets and official information, mainly related to national security but in unrevised form (based on the UK Official Secrets Act 1911) can include all info ...

, in which he agreed not to disclose anything about his work at Bletchley, with severe legal penalties for violating the Act.

Specifying the bombe was the first of five major cryptanalytical advances that Turing made during the war. The others were: deducing the indicator procedure used by the German navy; developing a statistical procedure dubbed ''Banburismus

Banburismus was a cryptanalytic process developed by Alan Turing at Bletchley Park in Britain during the Second World War. It was used by Bletchley Park's Hut 8 to help break German ''Kriegsmarine'' (naval) messages enciphered on Enigma machine ...

'' for making much more efficient use of the bombes; developing a procedure dubbed '' Turingery'' for working out the cam settings of the wheels of the Lorenz SZ 40/42 (''Tunny'') cipher machine and, towards the end of the war, the development of a portable secure voice

Secure voice (alternatively secure speech or ciphony) is a term in cryptography for the encryption of voice communication over a range of communication types such as radio, telephone or IP.

History

The implementation of voice encryption dat ...

scrambler at Hanslope Park

Hanslope Park is located about half a mile south-east of the village of Hanslope in the City of Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, England. Once the manorial estate of the village, it is now owned by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Of ...

that was codenamed ''Delilah''.

By using statistical techniques to optimise the trial of different possibilities in the code breaking process, Turing made an innovative contribution to the subject. He wrote two papers discussing mathematical approaches, titled ''The Applications of Probability to Cryptography'' and ''Paper on Statistics of Repetitions'', which were of such value to GC&CS and its successor GCHQ

Government Communications Headquarters, commonly known as GCHQ, is an intelligence and security organisation responsible for providing signals intelligence (SIGINT) and information assurance (IA) to the government and armed forces of the Uni ...

that they were not released to the UK National Archives until April 2012, shortly before the centenary of his birth. A GCHQ mathematician, "who identified himself only as Richard," said at the time that the fact that the contents had been restricted under the Official Secrets Act for some 70 years demonstrated their importance, and their relevance to post-war cryptanalysis:

Turing had a reputation for eccentricity at Bletchley Park. He was known to his colleagues as "Prof" and his treatise on Enigma was known as the "Prof's Book". According to historian Ronald Lewin, Jack Good, a cryptanalyst who worked with Turing, said of his colleague:

Peter Hilton recounted his experience working with Turing in Hut 8

Hut 8 was a section in the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park (the British World War II codebreaking station, located in Buckinghamshire) tasked with solving German naval (Kriegsmarine) Enigma messages. The section was l ...

in his "Reminiscences of Bletchley Park" from ''A Century of Mathematics in America:''

Hilton echoed similar thoughts in the Nova PBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcaster and non-commercial, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly funded nonprofit organization and the most prominent provider of ed ...

documentary ''Decoding Nazi Secrets''.

While working at Bletchley, Turing, who was a talented long-distance runner

Long-distance running, or endurance running, is a form of continuous running over distances of at least . Physiologically, it is largely aerobic in nature and requires stamina as well as mental strength.

Within endurance running comes two d ...

, occasionally ran the to London when he was needed for meetings, and he was capable of world-class marathon standards. Turing tried out for the 1948 British Olympic team, but he was hampered by an injury. His tryout time for the marathon was only 11 minutes slower than British silver medallist Thomas Richards' Olympic race time of 2 hours 35 minutes. He was Walton Athletic Club's best runner, a fact discovered when he passed the group while running alone. When asked why he ran so hard in training he replied:

Due to the problems of counterfactual history

Counterfactual history (also virtual history) is a form of historiography that attempts to answer the '' What if?'' questions that arise from counterfactual conditions. As a method of intellectual enquiry, counterfactual history explores histo ...

, it is hard to estimate the precise effect Ultra intelligence had on the war. However, official war historian Harry Hinsley

Sir Francis Harry Hinsley, (26 November 1918 – 16 February 1998) was an English historian and cryptanalyst. He worked at Bletchley Park during the Second World War and wrote widely on the history of international relations and British Inte ...

estimated that this work shortened the war in Europe by more than two years and saved over 14 million lives. Transcript of a lecture given on Tuesday 19 October 1993 at Cambridge University

At the end of the war, a memo was sent to all those who had worked at Bletchley Park, reminding them that the code of silence dictated by the Official Secrets Act did not end with the war but would continue indefinitely. Thus, even though Turing was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

(OBE) in 1946 by King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of I ...

for his wartime services, his work remained secret for many years.

Bombe

Within weeks of arriving at Bletchley Park, Turing had specified an electromechanical machine called thebombe

The bombe () was an electro-mechanical device used by British cryptologists to help decipher German Enigma-machine-encrypted secret messages during World War II. The US Navy and US Army later produced their own machines to the same functiona ...

, which could break Enigma more effectively than the Polish '' bomba kryptologiczna'', from which its name was derived. The bombe, with an enhancement suggested by mathematician Gordon Welchman

William Gordon Welchman (15 June 1906 – 8 October 1985) was a British mathematician. During World War II, he worked at Britain's secret codebreaking centre, "Station X" at Bletchley Park, where he was one of the most important contributors. ...

, became one of the primary tools, and the major automated one, used to attack Enigma-enciphered messages.

The bombe searched for possible correct settings used for an Enigma message (i.e., rotor order, rotor settings and plugboard settings) using a suitable '' crib'': a fragment of probable

The bombe searched for possible correct settings used for an Enigma message (i.e., rotor order, rotor settings and plugboard settings) using a suitable '' crib'': a fragment of probable plaintext

In cryptography, plaintext usually means unencrypted information pending input into cryptographic algorithms, usually encryption algorithms. This usually refers to data that is transmitted or stored unencrypted.

Overview

With the advent of com ...

. For each possible setting of the rotors (which had on the order of 1019 states, or 1022 states for the four-rotor U-boat variant), the bombe performed a chain of logical deductions based on the crib, implemented electromechanically.

The bombe detected when a contradiction had occurred and ruled out that setting, moving on to the next. Most of the possible settings would cause contradictions and be discarded, leaving only a few to be investigated in detail. A contradiction would occur when an enciphered letter would be turned back into the same plaintext letter, which was impossible with the Enigma. The first bombe was installed on 18 March 1940.

Action This Day

By late 1941, Turing and his fellow cryptanalystsGordon Welchman

William Gordon Welchman (15 June 1906 – 8 October 1985) was a British mathematician. During World War II, he worked at Britain's secret codebreaking centre, "Station X" at Bletchley Park, where he was one of the most important contributors. ...

, Hugh Alexander and Stuart Milner-Barry were frustrated. Building on the work of the Poles, they had set up a good working system for decrypting Enigma signals, but their limited staff and bombes meant they could not translate all the signals. In the summer, they had considerable success, and shipping losses had fallen to under 100,000 tons a month; however, they badly needed more resources to keep abreast of German adjustments. They had tried to get more people and fund more bombes through the proper channels, but had failed.

On 28 October they wrote directly to Winston Churchill explaining their difficulties, with Turing as the first named. They emphasised how small their need was compared with the vast expenditure of men and money by the forces and compared with the level of assistance they could offer to the forces. As Andrew Hodges, biographer of Turing, later wrote, "This letter had an electric effect." Churchill wrote a memo to General Ismay, which read: "ACTION THIS DAY. Make sure they have all they want on extreme priority and report to me that this has been done." On 18 November, the chief of the secret service reported that every possible measure was being taken. The cryptographers at Bletchley Park did not know of the Prime Minister's response, but as Milner-Barry recalled, "All that we did notice was that almost from that day the rough ways began miraculously to be made smooth." More than two hundred bombes were in operation by the end of the war.

Hut 8 and the naval Enigma

Turing decided to tackle the particularly difficult problem of German naval Enigma "because no one else was doing anything about it and I could have it to myself". In December 1939, Turing solved the essential part of the navalindicator

Indicator may refer to:

Biology

* Environmental indicator of environmental health (pressures, conditions and responses)

* Ecological indicator of ecosystem health (ecological processes)

* Health indicator, which is used to describe the health o ...

system, which was more complex than the indicator systems used by the other services.

That same night, he also conceived of the idea of ''Banburismus

Banburismus was a cryptanalytic process developed by Alan Turing at Bletchley Park in Britain during the Second World War. It was used by Bletchley Park's Hut 8 to help break German ''Kriegsmarine'' (naval) messages enciphered on Enigma machine ...

'', a sequential statistical technique (what Abraham Wald

Abraham Wald (; hu, Wald Ábrahám, yi, אברהם וואַלד; – ) was a Jewish Hungarian mathematician who contributed to decision theory, geometry, and econometrics and founded the field of statistical sequential analysis. One o ...

later called sequential analysis

In statistics, sequential analysis or sequential hypothesis testing is statistical analysis where the sample size is not fixed in advance. Instead data are evaluated as they are collected, and further sampling is stopped in accordance with a p ...

) to assist in breaking the naval Enigma, "though I was not sure that it would work in practice, and was not, in fact, sure until some days had actually broken." For this, he invented a measure of weight of evidence that he called the ''ban

Ban, or BAN, may refer to:

Law

* Ban (law), a decree that prohibits something, sometimes a form of censorship, being denied from entering or using the place/item

** Imperial ban (''Reichsacht''), a form of outlawry in the medieval Holy Roman ...

''. ''Banburismus'' could rule out certain sequences of the Enigma rotors, substantially reducing the time needed to test settings on the bombes. Later this sequential process of accumulating sufficient weight of evidence using decibans (one tenth of a ban) was used in Cryptanalysis of the Lorenz cipher

Cryptanalysis of the Lorenz cipher was the process that enabled the British to read high-level German army messages during World War II. The British Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park decrypted many communications betwe ...

.

Turing travelled to the United States in November 1942 and worked with US Navy cryptanalysts on the naval Enigma and bombe construction in Washington; he also visited their Computing Machine Laboratory in Dayton, Ohio

Dayton () is the sixth-largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Montgomery County. A small part of the city extends into Greene County. The 2020 U.S. census estimate put the city population at 137,644, while Greater ...

.

Turing's reaction to the American bombe design was far from enthusiastic:

During this trip, he also assisted at Bell Labs

Nokia Bell Labs, originally named Bell Telephone Laboratories (1925–1984),

then AT&T Bell Laboratories (1984–1996)

and Bell Labs Innovations (1996–2007),

is an American industrial research and scientific development company owned by mult ...

with the development of secure speech

Secure voice (alternatively secure speech or ciphony) is a term in cryptography for the encryption of voice communication over a range of communication types such as radio, telephone or IP.

History

The implementation of voice encryption date ...

devices. He returned to Bletchley Park in March 1943. During his absence, Hugh Alexander had officially assumed the position of head of Hut 8, although Alexander had been ''de facto'' head for some time (Turing having little interest in the day-to-day running of the section). Turing became a general consultant for cryptanalysis at Bletchley Park.

Alexander wrote of Turing's contribution:

Turingery

In July 1942, Turing devised a technique termed '' Turingery'' (or jokingly ''Turingismus'') for use against theLorenz cipher

The Lorenz SZ40, SZ42a and SZ42b were German rotor stream cipher machines used by the German Army during World War II. They were developed by C. Lorenz AG in Berlin. The model name ''SZ'' was derived from ''Schlüssel-Zusatz'', meaning ''cip ...

messages produced by the Germans' new ''Geheimschreiber'' (secret writer) machine. This was a teleprinter

A teleprinter (teletypewriter, teletype or TTY) is an electromechanical device that can be used to send and receive typed messages through various communications channels, in both point-to-point (telecommunications), point-to-point and point- ...

rotor cipher attachment codenamed ''Tunny'' at Bletchley Park. Turingery was a method of ''wheel-breaking'', i.e., a procedure for working out the cam settings of Tunny's wheels. He also introduced the Tunny team to Tommy Flowers

Thomas Harold Flowers MBE (22 December 1905 – 28 October 1998) was an English engineer with the British General Post Office. During World War II, Flowers designed and built Colossus, the world's first programmable electronic computer, to hel ...

who, under the guidance of Max Newman

Maxwell Herman Alexander Newman, FRS, (7 February 1897 – 22 February 1984), generally known as Max Newman, was a British mathematician and codebreaker. His work in World War II led to the construction of Colossus, the world's first operatio ...

, went on to build the Colossus computer

Colossus was a set of computers developed by British codebreakers in the years 1943–1945 to help in the cryptanalysis of the Lorenz cipher. Colossus used thermionic valves (vacuum tubes) to perform Boolean and counting operations. Colossus ...

, the world's first programmable digital electronic computer, which replaced a simpler prior machine (the Heath Robinson

William Heath Robinson (31 May 1872 – 13 September 1944) was an English cartoonist, illustrator and artist, best known for drawings of whimsically elaborate machines to achieve simple objectives.

In the UK, the term "Heath Robinson contr ...

), and whose superior speed allowed the statistical decryption techniques to be applied usefully to the messages. Some have mistakenly said that Turing was a key figure in the design of the Colossus computer. Turingery and the statistical approach of Banburismus undoubtedly fed into the thinking about cryptanalysis of the Lorenz cipher

Cryptanalysis of the Lorenz cipher was the process that enabled the British to read high-level German army messages during World War II. The British Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park decrypted many communications betwe ...

, but he was not directly involved in the Colossus development.

Delilah

Following his work atBell Labs

Nokia Bell Labs, originally named Bell Telephone Laboratories (1925–1984),

then AT&T Bell Laboratories (1984–1996)

and Bell Labs Innovations (1996–2007),

is an American industrial research and scientific development company owned by mult ...

in the US, Turing pursued the idea of electronic enciphering of speech in the telephone system. In the latter part of the war, he moved to work for the Secret Service's Radio Security Service (later HMGCC

His Majesty's Government Communications Centre (HMGCC) is an organisation which provides electronics and software to support the communication needs of the British Government. Based at Hanslope Park, near Milton Keynes in Buckinghamshire, it is ...

) at Hanslope Park

Hanslope Park is located about half a mile south-east of the village of Hanslope in the City of Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, England. Once the manorial estate of the village, it is now owned by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Of ...

. At the park, he further developed his knowledge of electronics with the assistance of engineer Donald Bayley. Together they undertook the design and construction of a portable secure voice

Secure voice (alternatively secure speech or ciphony) is a term in cryptography for the encryption of voice communication over a range of communication types such as radio, telephone or IP.

History

The implementation of voice encryption dat ...

communications machine codenamed ''Delilah

Delilah ( ; , meaning "delicate";Gesenius's ''Hebrew-Chaldee Lexicon'' ar, دليلة, Dalīlah; grc, label=Greek, Δαλιδά, Dalidá) is a woman mentioned in the sixteenth chapter of the Book of Judges in the Hebrew Bible. She is loved b ...

''. The machine was intended for different applications, but it lacked the capability for use with long-distance radio transmissions. In any case, Delilah was completed too late to be used during the war. Though the system worked fully, with Turing demonstrating it to officials by encrypting and decrypting a recording of a Winston Churchill speech, Delilah was not adopted for use. Turing also consulted with Bell Labs on the development of SIGSALY

SIGSALY (also known as the X System, Project X, Ciphony I, and the Green Hornet) was a secure speech system used in World War II for the highest-level Allied communications. It pioneered a number of digital communications concepts, including the ...

, a secure voice system that was used in the later years of the war.

Early computers and the Turing test

Between 1945 and 1947, Turing lived in

Between 1945 and 1947, Turing lived in Hampton

Hampton may refer to:

Places Australia

*Hampton bioregion, an IBRA biogeographic region in Western Australia

* Hampton, New South Wales

*Hampton, Queensland, a town in the Toowoomba Region

*Hampton, Victoria

Canada

*Hampton, New Brunswick

*Ham ...

, London, while he worked on the design of the ACE

An ace is a playing card, die or domino with a single pip. In the standard French deck, an ace has a single suit symbol (a heart, diamond, spade, or club) located in the middle of the card, sometimes large and decorated, especially in the ca ...

(Automatic Computing Engine) at the National Physical Laboratory (NPL). He presented a paper on 19 February 1946, which was the first detailed design of a stored-program computer

A stored-program computer is a computer that stores program instructions in electronically or optically accessible memory. This contrasts with systems that stored the program instructions with plugboards or similar mechanisms.

The definition ...

. Von Neumann Von Neumann may refer to:

* John von Neumann (1903–1957), a Hungarian American mathematician

* Von Neumann family

* Von Neumann (surname), a German surname

* Von Neumann (crater), a lunar impact crater

See also

* Von Neumann algebra

* Von Neu ...