Aesculapian Snake on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Aesculapian snake (now ''Zamenis longissimus'', previously ''Elaphe longissima''), is a

''Z. longissimus'' hatches at around 30 cm (11.8 in). Adults are usually from 110 cm (43.3 in) to in total length (including tail), but can grow to , with the record size being . Expected body mass in adult Aesculapian snakes is from . It is dark, long, slender, and typically bronzy in colour, with smooth scales that give it a metallic sheen.

Juveniles can easily be confused with juvenile

''Z. longissimus'' hatches at around 30 cm (11.8 in). Adults are usually from 110 cm (43.3 in) to in total length (including tail), but can grow to , with the record size being . Expected body mass in adult Aesculapian snakes is from . It is dark, long, slender, and typically bronzy in colour, with smooth scales that give it a metallic sheen.

Juveniles can easily be confused with juvenile  Adults are much more uniform, sometimes being olive-yellow, brownish-green, sometimes almost black. Often in adults, there may be a more or less regular pattern of white-edged dorsal scales appearing as white freckles all over the body up to moiré-like structures in places, enhancing the shiny metallic appearance. Sometimes, especially when pale in colour, two darker longitudinal lines along the flanks can be visible. The belly is plain yellow to off-white, while the round iris has amber to ochre colouration. Melanistic,

Adults are much more uniform, sometimes being olive-yellow, brownish-green, sometimes almost black. Often in adults, there may be a more or less regular pattern of white-edged dorsal scales appearing as white freckles all over the body up to moiré-like structures in places, enhancing the shiny metallic appearance. Sometimes, especially when pale in colour, two darker longitudinal lines along the flanks can be visible. The belly is plain yellow to off-white, while the round iris has amber to ochre colouration. Melanistic,

The contiguous area of the previous

The contiguous area of the previous

The Aesculapian snake prefers forested, warm but not hot, moderately humid but not wet, hilly or rocky habitats with proper insolation and varied, not sparse vegetation that provides sufficient variation in local microclimates, helping the reptile with

The Aesculapian snake prefers forested, warm but not hot, moderately humid but not wet, hilly or rocky habitats with proper insolation and varied, not sparse vegetation that provides sufficient variation in local microclimates, helping the reptile with

Their main food source are rodents up to the size of rats (a 130 cm adult specimen has been reported to have overpowered a 200g rat) and other small mammals such as shrews and moles. They also eat birds as well as bird eggs and nestlings. They suffocate their prey by constriction, though harmless smaller mouthfuls may be eaten alive without constriction, or simply crushed on eating by jaws. Juveniles mainly eat lizards and arthropods, later small rodents. Other snakes and lizards are taken, but only found rarely in adult prey.

Predators include badgers and other mustelids, foxes, wild boar (mainly by digging up and decimating hatches and newborns), hedgehogs, and various birds of prey (though there are reports of adults successfully standing their ground against feathered attackers). Juveniles may be eaten by smooth snakes and other reptilivorous snakes. Also a threat mainly to juveniles and hatches are domestic animals such as cats, dogs, and chickens, and even rats may be dangerous to inactive adult specimens in hibernation. In areas of concurrent distribution, they are also preyed upon by introduced North American raccoons and east Asian

Their main food source are rodents up to the size of rats (a 130 cm adult specimen has been reported to have overpowered a 200g rat) and other small mammals such as shrews and moles. They also eat birds as well as bird eggs and nestlings. They suffocate their prey by constriction, though harmless smaller mouthfuls may be eaten alive without constriction, or simply crushed on eating by jaws. Juveniles mainly eat lizards and arthropods, later small rodents. Other snakes and lizards are taken, but only found rarely in adult prey.

Predators include badgers and other mustelids, foxes, wild boar (mainly by digging up and decimating hatches and newborns), hedgehogs, and various birds of prey (though there are reports of adults successfully standing their ground against feathered attackers). Juveniles may be eaten by smooth snakes and other reptilivorous snakes. Also a threat mainly to juveniles and hatches are domestic animals such as cats, dogs, and chickens, and even rats may be dangerous to inactive adult specimens in hibernation. In areas of concurrent distribution, they are also preyed upon by introduced North American raccoons and east Asian

The Aesculapian Snake was first described by

The Aesculapian Snake was first described by

Available online

at the

Image:Rod of asclepius.png, The classical Rod of Aesculapius as a symbol of human medicine.

Image:Vetlogo.svg, The V-form as a symbol of veterinary medicine.

Image:Coupe_d'Hygie.svg, The Aesculapian Snake with the

File:Couleuvre Esculape59.JPG, Mounted specimen.

File:Couleuvre d'Escupage en déplacement.JPG, An adult traveling through a flower bed.

European Field Herping Community

{{Authority control Zamenis Reptiles described in 1768 Taxa named by Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti

species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of ...

of nonvenomous snake

Snakes are elongated, limbless, carnivorous reptiles of the suborder Serpentes . Like all other squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales. Many species of snakes have skulls with several more j ...

native to Europe, a member of the Colubrinae subfamily of the family

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Idea ...

Colubridae

Colubridae (, commonly known as colubrids , from la, coluber, 'snake') is a family of snakes. With 249 genera, it is the largest snake family. The earliest species of the family date back to the Oligocene epoch. Colubrid snakes are found on ev ...

. Growing up to in length, it is among the largest European snakes, similar in size to the four-lined snake (''Elaphe quatuorlineata

''Elaphe quatuorlineata'' (common names: four-lined snake, Bulgarian ratsnake) is a member of the family Colubridae. The four-lined snake is a non-venomous species and one of the largest of the European snakes.

Description

The species' common ...

'') and the Montpellier snake (''Malpolon monspessulanus

''Malpolon monspessulanus'', commonly known as the Montpellier snake, is a species of mildly venomous rear-fanged snake.

Geographic range

It is very common in Spain, Portugal and Northwest Africa, being also present in the southern Mediterranea ...

''). The Aesculapian snake has been of cultural and historical significance for its role in ancient Greek, Roman and Illyrian mythology

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of Narrative, narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or Origin myth, origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not Objectivity (philosophy), ...

and derived symbolism.

Description

''Z. longissimus'' hatches at around 30 cm (11.8 in). Adults are usually from 110 cm (43.3 in) to in total length (including tail), but can grow to , with the record size being . Expected body mass in adult Aesculapian snakes is from . It is dark, long, slender, and typically bronzy in colour, with smooth scales that give it a metallic sheen.

Juveniles can easily be confused with juvenile

''Z. longissimus'' hatches at around 30 cm (11.8 in). Adults are usually from 110 cm (43.3 in) to in total length (including tail), but can grow to , with the record size being . Expected body mass in adult Aesculapian snakes is from . It is dark, long, slender, and typically bronzy in colour, with smooth scales that give it a metallic sheen.

Juveniles can easily be confused with juvenile grass snake

The grass snake (''Natrix natrix''), sometimes called the ringed snake or water snake, is a Eurasian non- venomous colubrid snake. It is often found near water and feeds almost exclusively on amphibians.

Subspecies

Many subspecies are recogn ...

s (''Natrix natrix'') and barred grass snakes (''Natrix helvetica''), because juvenile Aesculapians also have a yellow collar on the neck that may persist for some time in younger adults. Juvenile ''Z. longissimus'' are light green or brownish-green with various darker patterns along the flanks and on the back. Two darker patches appear in the form of lines running on the top of the flanks. The head in juveniles also features several distinctive dark spots, one hoof-like on the back of the head in-between the yellow neck stripes, and two paired ones, with one horizontal stripe running from the eye and connecting to the neck marks, and one short vertical stripe connecting the eye with the fourth to fifth upper labial

In reptiles, the supralabial scales, also called upper-labials, are those scales that border the mouth opening along the upper jaw. They do not include the median scaleWright AH, Wright AA. 1957. Handbook of Snakes. Comstock Publishing Associates ( ...

scales.

Adults are much more uniform, sometimes being olive-yellow, brownish-green, sometimes almost black. Often in adults, there may be a more or less regular pattern of white-edged dorsal scales appearing as white freckles all over the body up to moiré-like structures in places, enhancing the shiny metallic appearance. Sometimes, especially when pale in colour, two darker longitudinal lines along the flanks can be visible. The belly is plain yellow to off-white, while the round iris has amber to ochre colouration. Melanistic,

Adults are much more uniform, sometimes being olive-yellow, brownish-green, sometimes almost black. Often in adults, there may be a more or less regular pattern of white-edged dorsal scales appearing as white freckles all over the body up to moiré-like structures in places, enhancing the shiny metallic appearance. Sometimes, especially when pale in colour, two darker longitudinal lines along the flanks can be visible. The belly is plain yellow to off-white, while the round iris has amber to ochre colouration. Melanistic, erythristic

Erythrism or erythrochroism refers to an unusual reddish pigmentation of an animal's hair, skin, feathers, or eggshells.

Causes of erythrism include:

* Genetic mutations which cause an absence of a normal pigment and/or excessive production of o ...

, and albinotic natural forms are known, as is a dark grey form.

Although there is no noticeable sexual dimorphism in colouration, males grow significantly longer than females, presumably because of the more significant energy input of the latter into the reproductive cycle. Maximum weight for German populations has been for males and for females ( Böhme 1993; Gomille 2002). Other distinctions, as in many snakes, include in males a relatively longer tail to total body length and a wider tail base.

Scale arrangement includes 23 dorsal scale

In snakes, the dorsal scales are the longitudinal series of plates that encircle the body, but do not include the ventral scales. Campbell JA, Lamar WW (2004). ''The Venomous Reptiles of the Western Hemisphere''. Ithaca and London: Comstock Publis ...

rows at midbody (rarely 19 or 21), 211-250 ventral scales

In snakes, the ventral scales or gastrosteges are the enlarged and transversely elongated scales that extend down the underside of the body from the neck to the anal scale. When counting them, the first is the anteriormost ventral scale that conta ...

, a divided anal scale

Anal may refer to:

Related to the anus

*Related to the anus of animals:

** Anal fin, in fish anatomy

** Anal vein, in insect anatomy

** Anal scale, in reptile anatomy

*Related to the human anus:

** Anal sex, a type of sexual activity involving ...

, and 60-91 paired subcaudal scales

In snakes, the subcaudal scales are the enlarged plates on the underside of the tail.Wright AH, Wright AA. 1957. Handbook of Snakes. Comstock Publishing Associates (7th printing, 1985). 1105 pp. . These scales may be either single or divided (pair ...

(Schultz 1996; Arnold

Arnold may refer to:

People

* Arnold (given name), a masculine given name

* Arnold (surname), a German and English surname

Places Australia

* Arnold, Victoria, a small town in the Australian state of Victoria

Canada

* Arnold, Nova Scotia

Uni ...

2002). Ventral scales are sharply angled where the underside meets the side of the body, which enhances the species' climbing ability.

Lifespan is estimated at 25 to 30 years.

Geographic range

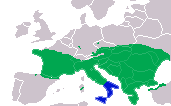

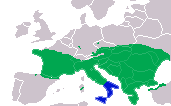

The contiguous area of the previous

The contiguous area of the previous nominotypical subspecies

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics ( morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all specie ...

, ''Zamenis longissimus longissimus'', which is now the only recognized monotypic

In biology, a monotypic taxon is a taxonomic group (taxon) that contains only one immediately subordinate taxon. A monotypic species is one that does not include subspecies or smaller, infraspecific taxa. In the case of genera, the term "unispec ...

form, covers most of France except in the north (up to about the latitude of Paris), the Spanish Pyrenees and the eastern side of the Spanish northern coast, Italy (except the south and Sicily), all of the Balkan peninsula down to Greece and Asia Minor and parts of Central and Eastern Europe up until about the 49th parallel in the eastern part of the range (Switzerland, Austria, South Moravia ( Podyjí/Thayatal in Austria) in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia, south Poland (mainly Bieszczady/ Bukovec Mountains in Slovakia), Romania, south-west Ukraine).

Further isolated populations have been identified in western Germany ( Schlangenbad, Odenwald

The Odenwald () is a low mountain range in the German states of Hesse, Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg.

Location

The Odenwald is located between the Upper Rhine Plain with the Bergstraße and the ''Hessisches Ried'' (the northeastern se ...

, lower Salzach

The Salzach (Austrian: �saltsax ) is a river in Austria and Germany. It is in length and is a right tributary of the Inn, which eventually joins the Danube. Its drainage basin of comprises large parts of the Northern Limestone and Central ...

, plus one - near Passau - connected to the contiguous distribution area) and the northwest of the Czech Republic (near Karlovy Vary

Karlovy Vary (; german: Karlsbad, formerly also spelled ''Carlsbad'' in English) is a spa city in the Karlovy Vary Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 46,000 inhabitants. It lies on the confluence of the rivers Ohře and Teplá. It is ...

, the northernmost known current natural presence of the species). Also found in a separate enclave south of Greater Caucasus

The Greater Caucasus ( az, Böyük Qafqaz, Бөјүк Гафгаз, بيوک قافقاز; ka, დიდი კავკასიონი, ''Didi K’avk’asioni''; russian: Большой Кавказ, ''Bolshoy Kavkaz'', sometimes translat ...

along the Russian, Georgian and Turkish northeastern and eastern shores of the Black Sea.

Two further enclaves include the first around Lake Urmia

Lake Urmia;

az, اۇرمۇ گؤلۆ, script=Arab, italic=no, Urmu gölü;

ku, گۆلائوو رمیەیێ, Gola Ûrmiyeyê;

hy, Ուրմիա լիճ, Urmia lich;

arc, ܝܡܬܐ ܕܐܘܪܡܝܐ is an endorheic salt lake in Iran. The lake is ...

in northern Iran, and on the northern slopes of Mount Ararat

Mount Ararat or , ''Ararat''; or is a snow-capped and dormant compound volcano in the extreme east of Turkey. It consists of two major volcanic cones: Greater Ararat and Little Ararat. Greater Ararat is the highest peak in Turkey and the ...

in east Turkey, roughly halfway between the former and the Black Sea habitats. V.L. Laughlin hypothesized that parts of the species' geographical distribution may be the result of intentional placement and later release of these snakes by Romans from the temples of Asclepius

Asclepius (; grc-gre, Ἀσκληπιός ''Asklēpiós'' ; la, Aesculapius) is a hero and god of medicine in ancient Greek religion and mythology. He is the son of Apollo and Coronis, or Arsinoe, or of Apollo alone. Asclepius represen ...

, classical god of medicine, where they were important in the medical rituals and worship of the god.

The previously recognised subspecies ''Zamenis longissimus romanus'', found in southern Italy and Sicily, has been recently elevated to the status of a separate new species, ''Zamenis lineatus

The Italian Aesculapian snake (''Zamenis lineatus'') is a species of snake in the Colubridae family.

Geographic range

''Z. lineatus'' is endemic to southern Italy and Sicily. The northern limit of its geographical range is the Province of Caser ...

'' (Italian Aesculapian Snake). It is lighter in color, with a reddish-orange to glowing red iris.

The populations previously classified as ''Elaphe longissima'' living in south-east Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Azərbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental country located at the boundary of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is a part of th ...

and northern Iranian Hyrcanian forests were reclassified by Nilson and Andrén in 1984 to ''Elaphe persica'', now ''Zamenis persicus

The Persian ratsnake (''Zamenis persicus'') is a species of medium-sized nonvenomous snake in the family Colubridae. The species is endemic to Western Asia.

Geographic range

''Z. persicus'' is found in temperate northwestern Iran and Azerbaijan, ...

''.

According to fossil evidence, the species' area in the warmer Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the "Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

period (around 8000–5000 years ago) of Holocene

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene togeth ...

reached as far north as Denmark. Three specimens were collected in Denmark between 1810 and 1863 on the southern part of Zealand

Zealand ( da, Sjælland ) at 7,031 km2 is the largest and most populous island in Denmark proper (thus excluding Greenland and Disko Island, which are larger in size). Zealand had a population of 2,319,705 on 1 January 2020.

It is th ...

, presumably from a relict and now extinct population. The current northwestern Czech population now is considered an autochthonous remnant of that maximum distribution based on the results of genetic analyses (it is closest genetically to the Carpathian populations). This likely applies also to the German populations. There are also fossils showing that they had UK residency during earlier interglacial periods but were driven south afterwards with subsequent glacials; these repeated climate-caused contractions and extensions of range in Europe appear to have occurred multiple times over the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the '' Ice age'') is the geological epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was finally confirmed ...

.

Escaped populations in Great Britain

There are three populations of Aesculapian snake which derive from escapes in Great Britain. The oldest recorded of these is in the grounds and vicinity of the Welsh Mountain Zoo nearConwy

Conwy (, ), previously known in English as Conway, is a walled market town, community and the administrative centre of Conwy County Borough in North Wales. The walled town and castle stand on the west bank of the River Conwy, facing Deganwy o ...

in North Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

. This population had persisted and reproduced since at least the early 1970s, and in 2022 the population was estimated at 70 adults. A second, more recent population was reported in 2010 to be along the Regent's Canal

Regent's Canal is a canal across an area just north of central London, England. It provides a link from the Paddington Arm of the Grand Union Canal, north-west of Paddington Basin in the west, to the Limehouse Basin and the River Thames ...

near London Zoo

London Zoo, also known as ZSL London Zoo or London Zoological Gardens is the world's oldest scientific zoo. It was opened in London on 27 April 1828, and was originally intended to be used as a collection for scientific study. In 1831 or 1832, ...

, living on rats and thought to number a few dozen, limited by the scarcity of egg-laying sites. It is suspected this colony may have been there some years, undetected. It is not a harmful invasive species, and the population was thought likely to become extinct. In 2020, a third population was confirmed in Britain being present in Bridgend

Bridgend (; cy, Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr or just , meaning "the end of the bridge on the Ogmore") is a town in Bridgend County Borough in Wales, west of Cardiff and east of Swansea. The town is named after the medieval bridge over the River Og ...

, Wales. This population has persisted for approximately 20 years.

Habitat

The Aesculapian snake prefers forested, warm but not hot, moderately humid but not wet, hilly or rocky habitats with proper insolation and varied, not sparse vegetation that provides sufficient variation in local microclimates, helping the reptile with

The Aesculapian snake prefers forested, warm but not hot, moderately humid but not wet, hilly or rocky habitats with proper insolation and varied, not sparse vegetation that provides sufficient variation in local microclimates, helping the reptile with thermoregulation

Thermoregulation is the ability of an organism to keep its body temperature within certain boundaries, even when the surrounding temperature is very different. A thermoconforming organism, by contrast, simply adopts the surrounding temperature ...

. In most of their range they are typically found in relatively intact or fairly cultivated warmer temperate broadleaf forests including the more humid variety such as along river valleys and riverbeds (but not marshes) and forest steppe

A forest steppe is a temperate-climate ecotone and habitat type composed of grassland interspersed with areas of woodland or forest.

Locations

Forest steppe primarily occurs in a belt of forest steppes across northern Eurasia from the easter ...

s. Frequented locations include places such as forest clearings in succession, shrublands at the edges of forests and forest/field ecotone

An ecotone is a transition area between two biological communities, where two communities meet and integrate. It may be narrow or wide, and it may be local (the zone between a field and forest) or regional (the transition between forest and gras ...

s, woods interspersed with meadows etc. However, they generally do not avoid human presence, being often found in places such as gardens and sheds, and even prefer habitats such as old walls and stonewalls, derelict buildings and ruins that offer a variety of hiding and basking places. The synanthropic aspect appears to be more pronounced in northernmost parts of the range where they are dependent on human structures for food, warmth and hatching grounds. They avoid open plains and agricultural deserts.

In the south their range seems to coincide with the borderline between deciduous broadleaf forests and Mediterranean shrublands, with the latter presumably too dry for the species. In the north their line of presence appears temperature-limited.

Diet and predators

Their main food source are rodents up to the size of rats (a 130 cm adult specimen has been reported to have overpowered a 200g rat) and other small mammals such as shrews and moles. They also eat birds as well as bird eggs and nestlings. They suffocate their prey by constriction, though harmless smaller mouthfuls may be eaten alive without constriction, or simply crushed on eating by jaws. Juveniles mainly eat lizards and arthropods, later small rodents. Other snakes and lizards are taken, but only found rarely in adult prey.

Predators include badgers and other mustelids, foxes, wild boar (mainly by digging up and decimating hatches and newborns), hedgehogs, and various birds of prey (though there are reports of adults successfully standing their ground against feathered attackers). Juveniles may be eaten by smooth snakes and other reptilivorous snakes. Also a threat mainly to juveniles and hatches are domestic animals such as cats, dogs, and chickens, and even rats may be dangerous to inactive adult specimens in hibernation. In areas of concurrent distribution, they are also preyed upon by introduced North American raccoons and east Asian

Their main food source are rodents up to the size of rats (a 130 cm adult specimen has been reported to have overpowered a 200g rat) and other small mammals such as shrews and moles. They also eat birds as well as bird eggs and nestlings. They suffocate their prey by constriction, though harmless smaller mouthfuls may be eaten alive without constriction, or simply crushed on eating by jaws. Juveniles mainly eat lizards and arthropods, later small rodents. Other snakes and lizards are taken, but only found rarely in adult prey.

Predators include badgers and other mustelids, foxes, wild boar (mainly by digging up and decimating hatches and newborns), hedgehogs, and various birds of prey (though there are reports of adults successfully standing their ground against feathered attackers). Juveniles may be eaten by smooth snakes and other reptilivorous snakes. Also a threat mainly to juveniles and hatches are domestic animals such as cats, dogs, and chickens, and even rats may be dangerous to inactive adult specimens in hibernation. In areas of concurrent distribution, they are also preyed upon by introduced North American raccoons and east Asian raccoon dog

The common raccoon dog (''Nyctereutes procyonoides''), also called the Chinese or Asian raccoon dog, is a small, heavy-set, fox-like canid native to East Asia. Named for its raccoon-like face markings, it is most closely related to foxes. Common ...

s.

Behaviour

The snakes are active by day. In the warmer months of the year, they come out in late afternoon or early morning. They are very good climbers capable of ascending even vertical, branchless tree trunks. The snakes have been observed at heights of and even in trees, and foraging in the roofs of buildings. Observed optimum temperature for activity in German populations is (Heimes 1988) and they are rarely recorded below or above , other observations for Ukrainian populations (Ščerbak et Ščerban 1980) put minimum activity temperature from and optimum to . Above around they try to avoid exposure to direct sunlight and cease activity with more extreme heat. The snakes will exhibit a degree of activity even during hibernation, moving around to keep a body temperature near and occasionally emerging to bask on sunny days. The average home range for French populations has been calculated at , however males will travel longer distances of up to to find females during the mating season and females to find suitable hatching sites to lay eggs. The Aesculapian snakes are deemed secretive and not always easy to find even in areas of positive presence, or found in surprising contexts. In contact with humans, they can be rather tame, possibly due to their cryptic coloration keeping them hidden within their natural environment. They usually disappear and hide, but if cornered they may sometimes stand their ground and try to intimidate their opponent, sometimes with a chewing-like movement of the mouth and occasionally biting. It has been speculated that the species may be actually more prevalent than thought due to spending a significant part of its time in tree canopy, however no reliable data exist as to what part that would be. In France it is said to be the only snake species that occurs inside dense, shadowy forests with minimum undergrowth, presumably because of using foliage for basking and foraging. In other parts of the range it has been reported to only use the canopy on a more substantial basis in largely uninhabited areas, such as the natural beech forests of the East Slovak and UkrainianCarpathians

The Carpathian Mountains or Carpathians () are a range of mountains forming an arc across Central Europe. Roughly long, it is the third-longest European mountain range after the Ural Mountains, Urals at and the Scandinavian Mountains at . The ...

, with similar characteristics.

Reproduction

Minimum length of individuals entering the reproductive cycle has been reported at 85–100 cm, which corresponds to sexual maturity age of about 4–6 years. Breeding occurs annually after hibernation in spring, typically from mid-May to mid-June. In this time the snakes actively seek each other and mating begins. Rival males engage in ritual fights the aim of which is to pin down the opponent's head with one's own or coils of one's body; biting may occur but is not typical. The actual courtship takes the form of an elegant dance between the male and female, with anterior portions of the bodies raised in an S-shape and the tails entwined. The male may also grasp the female's head with its jaw (Lotze 1975). 4 to 6 weeks after about 10 eggs are laid (extremes are from 2 to 20, with 5–11 on average) in a moist, warm spot where organic decomposition occurs, usually under hay piles, in rotting wood piles, heaps of manure or leaf mold, old tree stumps and similar places. Particularly in the northern parts of the range, preferred hatching grounds often are used by multiple females and are also shared with grass snakes. The eggs incubate for around 8 (6 to 10) weeks before hatching.Taxonomy

Apart from the recent taxonomic changes, there are currently four recognised phylogeographically traceable genetic lines in the species: the Westernhaplotype

A haplotype ( haploid genotype) is a group of alleles in an organism that are inherited together from a single parent.

Many organisms contain genetic material ( DNA) which is inherited from two parents. Normally these organisms have their DNA or ...

, Adriatic haplotype, the Danube haplotype and Eastern haplotype.

The status of the Iranian enclave population remains unclear due to its specific morphological characteristics (smaller length, scale arrangement, darker underbelly), probably pending reclassification.

History

The Aesculapian Snake was first described by

The Aesculapian Snake was first described by Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti

Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti (4 December 1735, Vienna – 17 February 1805, Vienna) was an Austrian naturalist and zoologist of Italian origin.

Laurenti is considered the auctor of the class Reptilia ( reptiles) through his authorship of ' (176 ...

in 1768 as ''Natrix longissima'', later it was also known as ''Coluber longissimus'' and for the most part of its history as ''Elaphe longissima''. The current scientific name of the species based on revisions of the large genus ''Elaphe'' is ''Zamenis longissimus''. ''Zamenis'' is from Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

''ζαμενής'' Wagler, J. (1830). ''Natürliches System der Amphibien : mit vorangehender Classification der Säugethiere und Vögel : ein Beitrag zur vergleichenden Zoologie.'' (''Zamenis'', new genus, p. 188)Available online

at the

Biodiversity Heritage Library

The Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL) is the world’s largest open access digital library for biodiversity literature and archives. BHL operates as worldwide consortiumof natural history, botanical, research, and national libraries working toge ...

(BHL). "angry", "irritable", "fierce", ''longissimus'' comes from Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

and means "longest"; the snake is one of the longest over its range. The common name of the species — "Aesculape" in French and its equivalents in other languages — refers to the classical god of healing (Greek Asclepius

Asclepius (; grc-gre, Ἀσκληπιός ''Asklēpiós'' ; la, Aesculapius) is a hero and god of medicine in ancient Greek religion and mythology. He is the son of Apollo and Coronis, or Arsinoe, or of Apollo alone. Asclepius represen ...

and later Roman Aesculapius) whose temples the snake was encouraged around. It is surmised that the typical depiction of the god with his snake-entwined staff features the species. Later from these, modern symbols developed of the medical professions as used in a number of variations today. The species, along with four-lined snakes, is carried in an annual religious procession in Cocullo in central Italy, which is of separate origin and was later made part of the Catholic calendar.

Bowl of Hygieia

The Bowl of Hygieia is one of the symbols of pharmacology, and along with the Rod of Asclepius it is one of the most ancient and important symbols related to medicine in western countries. Hygieia was the Greek goddess of health, hygiene, cleanl ...

as a symbol of pharmacology

Pharmacology is a branch of medicine, biology and pharmaceutical sciences concerned with drug or medication action, where a drug may be defined as any artificial, natural, or endogenous (from within the body) molecule which exerts a biochemi ...

.

Conservation

Though the Aesculapian snake occupies a relatively broad range and is not endangered as a species, it is thought to be in general decline largely due to anthropic disturbances. The snake is especially vulnerable in fringe parts and northern areas of its distribution where, given the historic retreat as a result of climatic changes since the Holocene climatic optimum, local populations remain isolated both from each other and from the main distribution centers, with no exchange of genetic material and no reinforcement through migration as a result. In such areas active local protection is due. The snake has been classified as Critically Endangered in the GermanRed List

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, also known as the IUCN Red List or Red Data Book, founded in 1964, is the world's most comprehensive inventory of the global conservation status of biolog ...

of endangered species. In most other countries including France, Switzerland, Austria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria, Poland, Ukraine and Russia it is also under protection status.

Among the key concerns is human-caused habitat destruction, with a series of respective recommendations concerning forestry

Forestry is the science and craft of creating, managing, planting, using, conserving and repairing forests, woodlands, and associated resources for human and environmental benefits. Forestry is practiced in plantations and natural stands. ...

and agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled peop ...

as to the protection through non-intervention of the species' core distribution centers, including targeted protection of potential hatching and hibernation places like old growth zones and fringe ecotones near woodland areas.

A significant threat also are roads both in terms of new construction and rising traffic, with a risk of further fragmentation of populations and loss of genetic exchange.

Gallery

See also

* List of reptiles of Italy *List of snake genera

List of snakes refers to a variety of different articles and different criteria. these are listed below.

Lists General lists

*General lists:

** Snake#Taxonomy

** List of reptile genera#Order Squamata

**List of snakes by common name

** List of sn ...

*List of reptiles of Europe

This is a list of reptiles of Europe. It includes all reptiles currently found in Europe. It does not include species found only in captivity or extinct in Europe, except where there is some doubt about this, nor (with few exceptions) does it cur ...

References

*''This page uses translations from respective articles in German, French, Russian and Polish Wikipedias.''Further reading

* Arnold EN, Burton JA (1978). ''A Field Guide to the Reptiles and Amphibians of Britain and Europe''. London: Collins. 272 pp. + Plates 1-40. . (''Elaphe longissima'', pp. 199–200 + Plate 36 + Map 112 on p. 266). * Boulenger GA (1894). ''Catalogue of the Snakes in the British Museum (Natural History). Volume II., Containing the Conclusion of the Colubridæ Aglyphæ.'' London: Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History). (Taylor and Francis, printers). xi + 382 pp. + Plates I-XX. (''Coluber longissimus'', pp. 52–54). * Laurenti JN (1768). ''Specimen medicum, exhibens synopsin reptilium emendatam cum experimentis circa venena et antidota reptilium austricorum.'' Vienna: "Joan. Thom. Nob. de Trattnern". 214 pp. + Plates I-V. (''Natrix longissima'', new species, p. 74). (inLatin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

).

External links

European Field Herping Community

{{Authority control Zamenis Reptiles described in 1768 Taxa named by Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti