Adrian Carton de Wiart on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

At the end of the war Carton de Wiart was sent to

At the end of the war Carton de Wiart was sent to

Despite these handicaps, Carton de Wiart managed to move his forces over the mountains and down to

Despite these handicaps, Carton de Wiart managed to move his forces over the mountains and down to

Within a month of his arrival back in England, Carton de Wiart was summoned to spend a night at the prime minister's country home at

Within a month of his arrival back in England, Carton de Wiart was summoned to spend a night at the prime minister's country home at  He regularly flew out to India to liaise with British officials. His old friend, Richard O'Connor, had escaped from the Italian prisoner-of-war camp and was now in command of British troops in eastern India. The

He regularly flew out to India to liaise with British officials. His old friend, Richard O'Connor, had escaped from the Italian prisoner-of-war camp and was now in command of British troops in eastern India. The

A good part of Carton de Wiart's reporting had to do with the increasing power of the

A good part of Carton de Wiart's reporting had to do with the increasing power of the

"Carton de Wiart, Sir Adrian (1880–1963)"

rev. G. D. Sheffield, ''

Location of grave and VC medal

''(Co. Cork)'' *

* , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Carton de Wiart, Adrian 1880 births 1963 deaths People educated at The Oratory School Alumni of Balliol College, Oxford Military personnel from Brussels British Army personnel of the Second Boer War British World War I recipients of the Victoria Cross British Battle of the Somme recipients of the Victoria Cross British amputees British anti-communists British Army generals of World War II Polish generals British Army cavalry generals of World War I World War II prisoners of war held by Italy British escapees English Roman Catholics Escapees from Italian detention Companions of the Distinguished Service Order Companions of the Order of the Bath Companions of the Order of St Michael and St George Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire Recipients of the Virtuti Militari British World War II prisoners of war 4th Royal Irish Dragoon Guards officers Imperial Light Horse officers Somaliland Camel Corps officers British Army recipients of the Victoria Cross Belgian people of Irish descent Belgian emigrants to the United Kingdom Naturalised citizens of the United Kingdom British expatriates in Poland Military personnel from Cairo British Army lieutenant generals

Lieutenant-General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

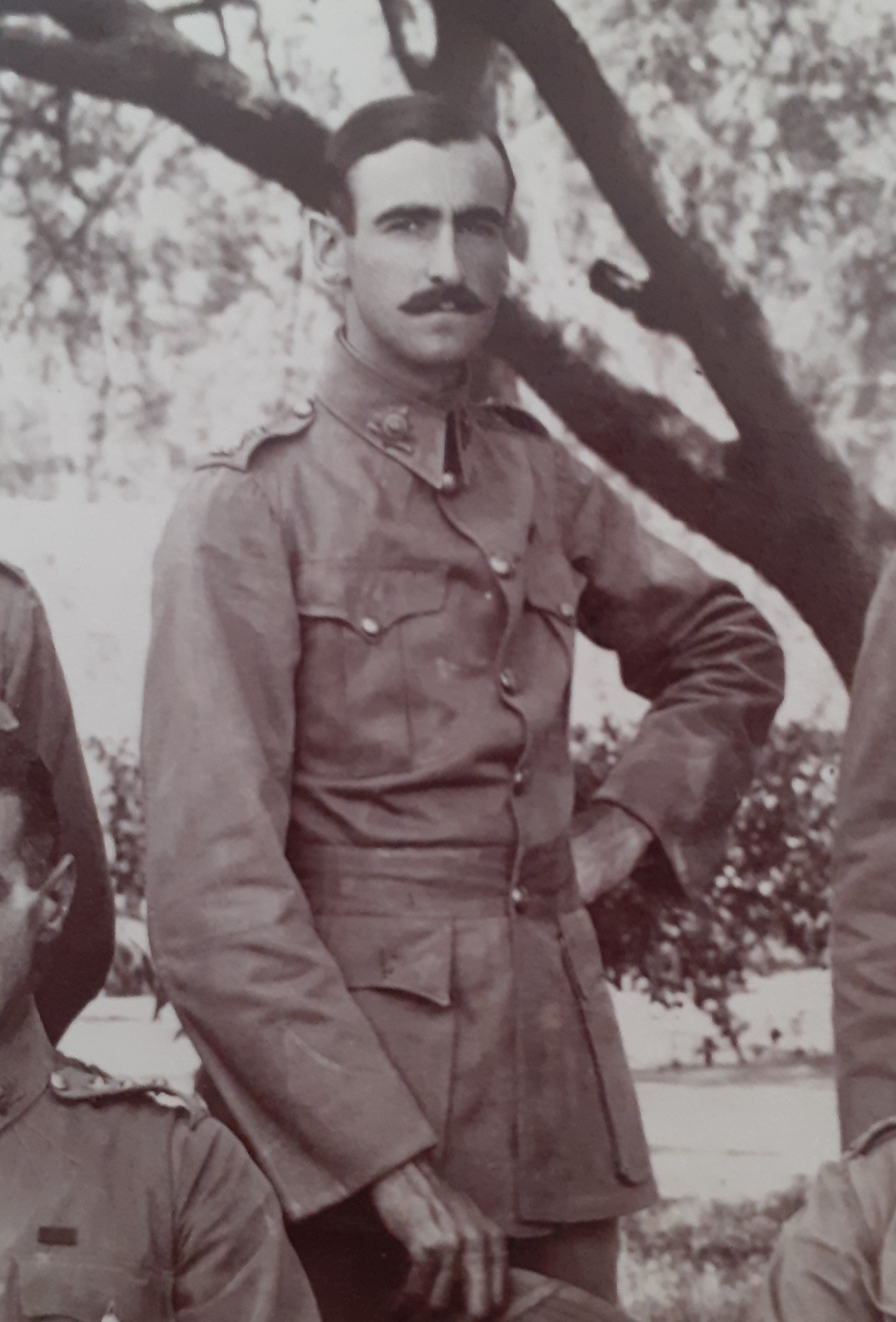

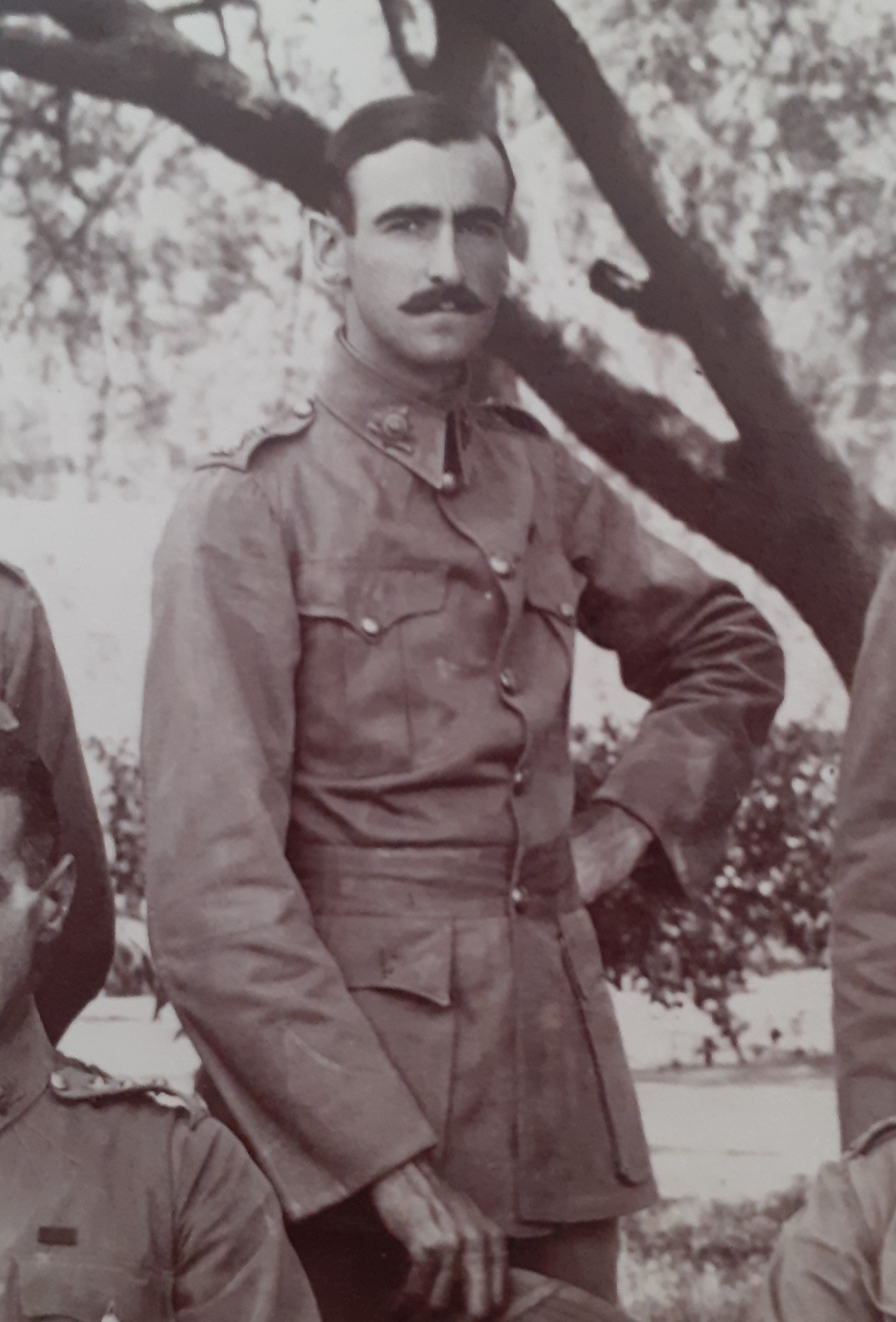

Sir Adrian Paul Ghislain Carton de Wiart, (; 5 May 1880 – 5 June 1963) was a British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

officer born of Belgian and Irish parents. He was awarded the Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious award of the British honours system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British Armed Forces and may be awarded posthumously. It was previously ...

, the highest military decoration awarded for valour "in the face of the enemy" in various Commonwealth countries. He served in the Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sou ...

, First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, and Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. He was shot in the face, head, stomach, ankle, leg, hip, and ear; was blinded in his left eye; survived two plane crashes; tunnelled out of a prisoner-of-war camp

A prisoner-of-war camp (often abbreviated as POW camp) is a site for the containment of enemy fighters captured by a belligerent power in time of war.

There are significant differences among POW camps, internment camps, and military prisons. P ...

; and tore off his own fingers when a doctor declined to amputate them. Describing his experiences in the First World War, he wrote, "Frankly I had enjoyed the war."

After returning home from service (including a period as a prisoner-of-war) in the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, he was sent to China as Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

's personal representative. While ''en route'' he attended the Cairo Conference

The Cairo Conference (codenamed Sextant) also known as the First Cairo Conference, was one of the 14 summit meetings during World War II that occurred on November 22–26, 1943. The Conference was held in Cairo, Egypt, between the United Kingdo ...

.

In his memoirs, Carton de Wiart wrote, "Governments may think and say as they like, but force cannot be eliminated, and it is the only real and unanswerable power. We are told that the pen is mightier than the sword

"The pen is mightier than the sword" is a metonymic adage, created by English author Edward Bulwer-Lytton in 1839, indicating that the written word is more effective than violence as a means of social or political change.

Under some interpretati ...

, but I know which of these weapons I would choose." Carton de Wiart was thought to be a model for the character of Brigadier Ben Ritchie-Hook in Evelyn Waugh

Arthur Evelyn St. John Waugh (; 28 October 1903 – 10 April 1966) was an English writer of novels, biographies, and travel books; he was also a prolific journalist and book reviewer. His most famous works include the early satires ''Decli ...

's trilogy ''Sword of Honour

The ''Sword of Honour'' is a trilogy of novels by Evelyn Waugh which loosely parallel Waugh's experiences during the Second World War. Published by Chapman & Hall from 1952 to 1961, the novels are: ''Men at Arms'' (1952); ''Officers and Gentl ...

''. The ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'' described him thus: "With his black eyepatch and empty sleeve, Carton de Wiart looked like an elegant pirate, and became a figure of legend."Williams, ODNB

Early life

Background

Carton de Wiart was born into anaristocratic

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At the time of the word's ...

family in Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

, on 5 May 1880, eldest son of Léon Constant Ghislain Carton de Wiart (1854–1915) and Ernestine Wenzig (1860–1886). By his contemporaries, he was widely believed to be an illegitimate son of King Leopold II of the Belgians. He spent his early days in Belgium and in England. The 'loss of his mother' when he was six prompted his father to move the family to Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

so his father could practise at Egypt's mixed courts. It was widely assumed by biographers that his mother had died in 1886; however, his parents had in fact divorced in that year and his mother remarried Demosthenes Gregory Cuppa later in 1886. His father was a lawyer and magistrate, as well as a director

Director may refer to:

Literature

* ''Director'' (magazine), a British magazine

* ''The Director'' (novel), a 1971 novel by Henry Denker

* ''The Director'' (play), a 2000 play by Nancy Hasty

Music

* Director (band), an Irish rock band

* ''D ...

of the Cairo Electric Railways and Heliopolis Oases Company

The Cairo Electric Railways & Heliopolis Oases Company ( ar, شركة سكك حديد مصر الكهربائية و واحات عين شمس), is the original name of the ''Heliopolis Company for Housing and Development'' ( ar, شركة مصر ...

and was well connected in Egyptian governmental circles. Adrian Carton de Wiart learned to speak Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

.

Carton de Wiart was a Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

. In 1891, his English stepmother sent him to a boarding school

A boarding school is a school where pupils live within premises while being given formal instruction. The word "boarding" is used in the sense of "room and board", i.e. lodging and meals. As they have existed for many centuries, and now exten ...

in England, the Roman Catholic Oratory School, founded by John Henry Newman

John Henry Newman (21 February 1801 – 11 August 1890) was an English theologian, academic, intellectual, philosopher, polymath, historian, writer, scholar and poet, first as an Anglican ministry, Anglican priest and later as a Catholi ...

. From there, he went to Balliol College, Oxford

Balliol College () is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. One of Oxford's oldest colleges, it was founded around 1263 by John I de Balliol, a landowner from Barnard Castle in County Durham, who provided the f ...

, but left to join the British Army at the time of the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

around 1899, where he entered under the false name of "Trooper Carton", claiming to be 25 years old. His real age was no more than 20.

Second Boer War

Carton de Wiart was wounded in the stomach and groin in South Africa early in the Second Boer War and was invalided home. His father was furious when he learned his son had abandoned his studies, but allowed his son to remain in the army. After another brief period at Oxford, whereAubrey Herbert

Colonel The Honourable Aubrey Nigel Henry Molyneux Herbert (3 April 1880 – 26 September 1923), of Pixton Park in Somerset and of Teversal, in Nottinghamshire, was a British soldier, diplomat, traveller, and intelligence officer associat ...

was among his friends, he was given a commission in the Second Imperial Light Horse

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imperial, Nebraska

* Imperial, Pennsylvania

* Imperial, Texas ...

. He saw action in South Africa again, and on 14 September 1901 was given a regular commission as a second lieutenant in the 4th Dragoon Guards. Carton de Wiart was transferred to India in 1902. He enjoyed sports, especially shooting and pig sticking

Boar hunting is the practice of hunting wild boar, feral pigs, warthogs, and peccaries. Boar hunting was historically a dangerous exercise due to the tusked animal's ambush tactics as well as its thick hide and dense bones rendering them difficul ...

.

Character, interests and life in the Edwardian army

Carton de Wiart's serious wound in the Boer War instilled in him a strong desire for physical fitness and he ran, jogged, walked, and played sports on a regular basis. In male company he was "a delightful character and must hold the world record for bad language." After his regiment was transferred to South Africa he was promoted to supernumerarylieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

on 16 July 1904 and appointed an aide-de-camp to the Commander-in-Chief, Sir Henry Hildyard

General Sir Henry John Thoroton Hildyard (5 July 1846 – 25 July 1916) was a British Army officer who saw active service in the Anglo-Egyptian War of 1882 and the Second Boer War. He was General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, South Africa, fr ...

, the following July. He describes this period lasting up to 1914 as his "Heyday", the title of Chapter 3 of his autobiography. His light duties as aide-de-camp gave him time for polo

Polo is a ball game played on horseback, a traditional field sport and one of the world's oldest known team sports. The game is played by two opposing teams with the objective of scoring using a long-handled wooden mallet to hit a small hard ...

, another of his interests. By 1907, although Carton de Wiart had now served in the British Army for eight years, he had remained a Belgian subject. On 13 September of that year, he took the oath of allegiance to Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria an ...

and was formally naturalised as a British subject.

In 1908 he married Countess Friederike Maria Karoline Henriette Rosa Sabina Franziska Fugger von Babenhausen (1887 Klagenfurt

Klagenfurt am WörtherseeLandesgesetzblatt 2008 vom 16. Jänner 2008, Stück 1, Nr. 1: ''Gesetz vom 25. Oktober 2007, mit dem die Kärntner Landesverfassung und das Klagenfurter Stadtrecht 1998 geändert werden.'/ref> (; ; sl, Celovec), usually ...

– 1949 Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

), eldest daughter of Karl, 5th Fürst

' (, female form ', plural '; from Old High German ', "the first", a translation of the Latin ') is a German word for a ruler and is also a princely title. ' were, since the Middle Ages, members of the highest nobility who ruled over states of ...

(Prince) von Fugger-Babenhausen and Princess Eleonora zu Hohenlohe-Bartenstein und Jagstberg of Klagenfurt, Austria. They had two daughters, the elder of whom Anita (born 1909, deceased) was the maternal grandmother of the war correspondent Anthony Loyd

Anthony William Vivian Loyd (born 12 September 1966) is an English journalist and noted war correspondent, best known for his 1999 book ''My War Gone By, I Miss It So''. He gained prominence in February 2019 when he tracked down a British Islami ...

(born 1966).

Carton de Wiart was already well connected in European circles, his two closest cousins being Count Henri Carton de Wiart

:''This article uses a Belgium, Belgian surname: the surname is Carton de Wiart, not Wiart.''

Henry Victor Marie Ghislain, Count Carton de Wiart (31 January 1869 – 6 May 1951) was the prime minister of Belgium from 20 November 1920 to 6 May 192 ...

, Prime Minister of Belgium

german: Premierminister von Belgien

, insignia = State Coat of Arms of Belgium.svg

, insigniasize = 100px

, insigniacaption = Coat of arms

, insigniaalt =

, flag = Government ...

from 1920 to 1921, and Baron Edmond Carton de Wiart, political secretary to the King of Belgium and director of La Société Générale de Belgique. While on leave, he travelled extensively throughout central Europe, using his Catholic aristocratic connections to shoot at country estates in Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

, Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

, and Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

. Following his return to England, he rode with the famous Duke of Beaufort's Hunt

The Duke of Beaufort's Hunt, also called the Beaufort and Beaufort Hunt, is one of the oldest and largest of the fox hunting packs in England.(Sohelmay)

History

Hunting with hounds in the area dates back to 1640, primarily deer but also foxes, ...

where he met, among others, the future field marshal, Sir Henry Maitland Wilson, and the future air marshal, Sir Edward Ellington

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Edward Leonard Ellington, (30 December 1877 – 13 June 1967) was a senior officer in the Royal Air Force. He served in the First World War as a staff officer and then as director-general of military aeronaut ...

. He was promoted to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

on 26 February 1910. The Duke of Beaufort

Duke of Beaufort (), a title in the Peerage of England, was created by Charles II in 1682 for Henry Somerset, 3rd Marquess of Worcester, a descendant of Charles Somerset, 1st Earl of Worcester, legitimised son of Henry Beaufort, 3rd Duke of So ...

was the honorary colonel of the Royal Gloucestershire Hussars

The Royal Gloucestershire Hussars was a volunteer yeomanry regiment which, in the 20th century, became part of the British Army Reserve. It traced its origins to the First or Cheltenham Troop of Gloucestershire Gentleman and Yeomanry raised in ...

, and from 1 January 1912 until his departure for Somaliland in 1914 Carton de Wiart served as the regiment's adjutant

Adjutant is a military appointment given to an officer who assists the commanding officer with unit administration, mostly the management of human resources in an army unit. The term is used in French-speaking armed forces as a non-commission ...

.

First World War

Somaliland Campaign

When the First World War broke out, Carton de Wiart was en route toBritish Somaliland

British Somaliland, officially the Somaliland Protectorate ( so, Dhulka Maxmiyada Soomaalida ee Biritishka), was a British Empire, British protectorate in present-day Somaliland. During its existence, the territory was bordered by Italian Soma ...

where a low-level war was underway against the followers of Dervish leader Mohammed bin Abdullah, called the "Mad Mullah" by the British. Carton de Wiart had been seconded to the Somaliland Camel Corps

The Somaliland Camel Corps (SCC) was a Rayid unit of the British Army based in British Somaliland. It lasted from the early 20th century until 1944.

Beginnings and the Dervish rebellion

In 1888, after signing successive treaties with the then r ...

. A staff officer with the corps was Hastings Ismay

Hastings Lionel Ismay, 1st Baron Ismay (21 June 1887 – 17 December 1965), was a diplomat and General (United Kingdom), general in the British Indian Army who was the first Secretary General of NATO. He also was Winston Churchill's chief mil ...

, later Lord Ismay, Churchill's military advisor. In an attack upon an enemy fort at Shimber Berris, Carton de Wiart was shot twice in the face, losing his eye and also a portion of his ear. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a military decoration of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly of other parts of the Commonwealth, awarded for meritorious or distinguished service by officers of the armed forces during wartime, typ ...

(DSO) on 15 May 1915.

Western Front

In February 1915, he embarked on a steamer for France. Carton de Wiart took part in the fighting on the Western Front, commanding successively three infantry battalions and a brigade. He was wounded seven more times in the war, losing his left hand in 1915 and pulling off his fingers when a doctor declined to remove them. He was shot through the skull and ankle at theBattle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme ( French: Bataille de la Somme), also known as the Somme offensive, was a battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and French Third Republic against the German Empire. It took place bet ...

, through the hip at the Battle of Passchendaele

The Third Battle of Ypres (german: link=no, Dritte Flandernschlacht; french: link=no, Troisième Bataille des Flandres; nl, Derde Slag om Ieper), also known as the Battle of Passchendaele (), was a campaign of the First World War, fought by t ...

, through the leg at Cambrai

Cambrai (, ; pcd, Kimbré; nl, Kamerijk), formerly Cambray and historically in English Camerick or Camericke, is a city in the Nord (French department), Nord Departments of France, department and in the Hauts-de-France Regions of France, regio ...

, and through the ear at Arras

Arras ( , ; pcd, Aro; historical nl, Atrecht ) is the prefecture of the Pas-de-Calais Departments of France, department, which forms part of the regions of France, region of Hauts-de-France; before the regions of France#Reform and mergers of ...

. He went to the Sir Douglas Shield's Nursing Home to recover from his injuries.

Victoria Cross

Carton de Wiart received theVictoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious award of the British honours system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British Armed Forces and may be awarded posthumously. It was previously ...

(VC), the highest award for gallantry in combat that can be awarded to British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

forces, in 1916. He was 36 years old, and a temporary lieutenant-colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colonel. ...

in the 4th Dragoon Guards (Royal Irish), British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

, attached to the Gloucestershire Regiment

The Gloucestershire Regiment, commonly referred to as the Glosters, was a line infantry regiment of the British Army from 1881 until 1994. It traced its origins to Colonel Gibson's Regiment of Foot, which was raised in 1694 and later became the ...

, commanding the 8th Battalion, when the following events took place on 2/3 July 1916 at La Boiselle

Ovillers-la-Boisselle is a commune in the Somme department in Hauts-de-France in northern France.

Geography

The commune of Ovillers-la-Boisselle is situated northeast of Amiens and extends to the north and south of the D 929 Albert–Bapaume r ...

, France, as recorded in the official citation:

His Victoria Cross is displayed at the National Army Museum

The National Army Museum is the British Army's central museum. It is located in the Chelsea district of central London, adjacent to the Royal Hospital Chelsea, the home of the "Chelsea Pensioners". The museum is a non-departmental public body. ...

, Chelsea.

1916–1918

Carton de Wiart was promoted to temporary major in March 1916. He subsequently attained the rank of temporary lieutenant colonel on 18 July, wasbrevetted

In many of the world's military establishments, a brevet ( or ) was a warrant giving a commissioned officer a higher rank title as a reward for gallantry or meritorious conduct but may not confer the authority, precedence, or pay of real rank. ...

to major on 1 January 1917 and was promoted to temporary brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

on 12 January 1917. He was appointed an Officer of the Order of the Crown of Belgium in April 1917. On 3 June 1917, Carton de Wiart was brevetted to lieutenant-colonel. On 18 July, he was promoted to the substantive rank of major in the Dragoon Guards. He was awarded the Belgian Croix de Guerre

The ''Croix de Guerre'' (, ''Cross of War'') is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was first awa ...

in March 1918, and was appointed a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George IV, George IV, Prince of Wales, while he was acting as prince regent for his father, George III, King George III.

...

in the King's Birthday Honours List in June.

Three days before the end of the war, on 8 November, Carton de Wiart was given command of a brigade with the rank of temporary brigadier general. A S Bullock gives a vivid first-hand description of his arrival: 'Cold shivers went down the back of everyone in the brigade, for he had an unsurpassed record as a fire eater, missing no chance of throwing the men under his command into whatever fighting happened to be going.' Bullock recalls how the battalion looked 'very much the worse for wear' when they paraded for the brigadier general's inspection. He arrived 'on a lively cob with his cap tilted at a rakish angle, and a shade over the place where one of his eyes had been'. He was also missing two limbs and had eleven wound stripes. Bullock, the first man in line for the inspection, notes that Carton de Wiart, despite having only one eye, ordered him to get his bootlace changed.

Post First World War era and the Polish mission

At the end of the war Carton de Wiart was sent to

At the end of the war Carton de Wiart was sent to Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

as second in command of the British-Poland Military Mission under General Louis Botha

Louis Botha (; 27 September 1862 – 27 August 1919) was a South African politician who was the first prime minister of the Union of South Africa – the forerunner of the modern South African state. A Boer war hero during the Second Boer War, ...

. Carton de Wiart was appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath

Companion may refer to:

Relationships Currently

* Any of several interpersonal relationships such as friend or acquaintance

* A domestic partner, akin to a spouse

* Sober companion, an addiction treatment coach

* Companion (caregiving), a caregive ...

in the 1919 King's Birthday Honours List. After a brief period, he replaced General Botha in the mission to Poland.

Poland desperately needed support, as it was engaged with Bolshevik Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

in the Polish-Soviet War, the Ukrainians

Ukrainians ( uk, Українці, Ukraintsi, ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. They are the seventh-largest nation in Europe. The native language of the Ukrainians is Ukrainian language, Ukrainian. The majority ...

in the Polish-Ukrainian War, the Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

ns in the Polish-Lithuanian War, and the Czechs

The Czechs ( cs, Češi, ; singular Czech, masculine: ''Čech'' , singular feminine: ''Češka'' ), or the Czech people (), are a West Slavic ethnic group and a nation native to the Czech Republic in Central Europe, who share a common ancestry, c ...

in the Czech-Polish border conflicts. There he met Ignacy Jan Paderewski

Ignacy Jan Paderewski (; – 29 June 1941) was a Polish pianist and composer who became a spokesman for Polish independence. In 1919, he was the new nation's Prime Minister and foreign minister during which he signed the Treaty of Versaill ...

, the pianist and premier, Marshal Józef Piłsudski

), Vilna Governorate, Russian Empire (now Lithuania)

, death_date =

, death_place = Warsaw, Poland

, constituency =

, party = None (formerly PPS)

, spouse =

, children = Wan ...

, the Chief of State and military commander, and General Maxime Weygand

Maxime Weygand (; 21 January 1867 – 28 January 1965) was a French military commander in World War I and World War II.

Born in Belgium, Weygand was raised in France and educated at the Saint-Cyr military academy in Paris. After graduating in 1 ...

, head of the French military mission

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with France ...

in mid-1920. One of his tasks soon after his arrival was to attempt to make peace between the Poles and the Ukrainian nationalists under Simon Petlyura

Symon Vasylyovych Petliura ( uk, Си́мон Васи́льович Петлю́ра; – May 25, 1926) was a Ukrainian politician and journalist. He became the Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, Ukrainian Army and the President ...

. The Ukrainians were besieging the city of Lwów

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in western Ukraine, and the seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is one of the main cultural centres of Ukraine ...

(; ). The discussions were unsuccessful.

From there he went on to Paris to report on Polish conditions to the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

and to General Sir Henry Wilson

Field Marshal Sir Henry Hughes Wilson, 1st Baronet, (5 May 1864 – 22 June 1922) was one of the most senior British Army staff officers of the First World War and was briefly an Irish unionist politician.

Wilson served as Commandant of the St ...

. Lloyd George was not sympathetic to Poland and, much to Carton de Wiart's annoyance, Britain sent next to no military supplies. Then he went back to Poland and many more front line adventures, this time in the Bolshevik zone, where the situation was grave and Warsaw threatened. During this time he had significant interaction with the nuntius

An apostolic nuncio ( la, nuntius apostolicus; also known as a papal nuncio or simply as a nuncio) is an ecclesiastical diplomat, serving as an envoy or a permanent diplomatic representative of the Holy See to a state or to an international org ...

(dean of the Vatican diplomatic corps) Cardinal Achille Ratti, later Pius XI

Pope Pius XI ( it, Pio XI), born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti (; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939), was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to his death in February 1939. He was the first sovereign of Vatican City from ...

, who wanted Carton de Wiart's advice as to whether to evacuate the diplomatic corps from Warsaw. The diplomats moved to Poznań

Poznań () is a city on the River Warta in west-central Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business centre, and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint John ...

, but the Italians remained in Warsaw along with Ratti.

From all these affairs, Carton de Wiart developed a sympathy with the Poles and supported their claims to eastern Galicia. This caused disagreement with Lloyd George at their next meeting, but was appreciated by the Poles. At one time during his Warsaw stay he was a second in a duel between Polish members of the Mysliwski Club, the other second being Baron Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim

Baron Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim (, ; 4 June 1867 – 27 January 1951) was a Finnish military leader and statesman. He served as the military leader of the Whites in the Finnish Civil War of 1918, as Regent of Finland (1918–1919), as comma ...

, later commander-in-chief of Finnish armies in World War II and President of Finland. Norman Davies

Ivor Norman Richard Davies (born 8 June 1939) is a Welsh-Polish historian, known for his publications on the history of Europe, Poland and the United Kingdom. He has a special interest in Central and Eastern Europe and is UNESCO Professor at ...

reports that he was "compromised in a gun-running operation from Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

using stolen wagon-lits".

He became close to the Polish leader, Marshal Piłsudski. After an aircraft crash occasioning a brief period in Lithuanian captivity, he went back to England to report, this time to the Secretary of State for War

The Secretary of State for War, commonly called War Secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The Secretary of State for War headed the War Office and ...

, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

. He passed on to Churchill Piłsudski's prediction that the White Russian offensive under General Anton Denikin

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (russian: Анто́н Ива́нович Дени́кин, link= ; 16 December Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_December.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New St ...

directed at Moscow would fail. It did shortly thereafter. Churchill was more sympathetic to Polish needs than Lloyd George and succeeded, over Lloyd George's objections, in sending some materiel

Materiel (; ) refers to supplies, equipment, and weapons in military supply-chain management, and typically supplies and equipment in a commercial supply chain context.

In a military context, the term ''materiel'' refers either to the specifi ...

to Poland.

On 27 July 1920, Carton de Wiart was appointed an aide-de-camp to the king, and brevetted to colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

. He was active in August 1920, when the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

were at the gates of Warsaw. While out on his observation train, he was attacked by a group of Red cavalry, and fought them off with his revolver from the footplate of his train, at one point falling on the track and re-boarding quickly.

When the Poles won the war, the British Military Mission was wound up. Carton de Wiart was promoted to temporary brigadier general and also appointed to the local rank of major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

on 1 January. He was promoted to the substantive rank of colonel on 21 June 1922, with seniority from 27 July 1920 and relinquished his local rank of major general on 1 April 1923, going on half-pay as a colonel at the same time. Carton de Wiart officially retired from the army on 19 December, with the honorary rank of major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

.

Polish gentleman (1924–1939)

His last Polish aide de camp was Prince Karol Mikołaj Radziwiłł, member of theRadziwiłł family

The House of Radziwiłł (; lt, Radvila; be, Радзівіл, Radzivił; german: link=no, Radziwill) is a powerful magnate family originating from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and later also prominent in the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland.

...

who inherited a large estate in eastern Poland when the communists killed his uncle. They became friends and Carton de Wiart was given the use of a large estate called Prostyń, in the Pripet Marshes

__NOTOC__

The Pinsk Marshes ( be, Пінскія балоты, ''Pinskiya baloty''), also known as the Pripet Marshes ( be, Прыпяцкія балоты, ''Prypiackija baloty''), the Polesie Marshes, and the Rokitno Marshes, are a vast natural ...

, a wetland area larger than Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

and surrounded by water and forests. In this location Carton de Wiart spent the rest of the interwar years. In his memoirs he said "In my fifteen years in the marshes I did not waste one day without hunting".

After 15 years, Carton de Wiart's peaceful Polish life was interrupted by the looming war, when he was recalled in July 1939 and appointed to his old job, as head of the British Military Mission to Poland. Poland was attacked by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

on 1 September and on 17 September the Soviets

Soviet people ( rus, сове́тский наро́д, r=sovyétsky naród), or citizens of the USSR ( rus, гра́ждане СССР, grázhdanye SSSR), was an umbrella demonym for the population of the Soviet Union.

Nationality policy in th ...

allied with Germany attacked Poland from the east. Soon Soviet forces overran Prostyń and Carton de Wiart lost all his guns, fishing rods, clothing, and furniture. They were packed up by the Soviets and stored in the Minsk Museum, but destroyed by the Germans in later fighting. He never saw the area again, but as he said "they did not manage to take my memories".

Second World War

Polish campaign (1939)

Carton de Wiart met with the Polish commander-in-chief,Marshal of Poland

Marshal of Poland ( pl, Marszałek Polski) is the highest rank in the Polish Army. It has been granted to only six officers. At present, Marshal is equivalent to a Field Marshal or General of the Army (OF-10) in other NATO armies.

History

To ...

Edward Rydz-Śmigły

Marshal Edward Rydz-Śmigły (11 March 1886 – 2 December 1941; nom de guerre ''Śmigły, Tarłowski, Adam Zawisza''), also called Edward Śmigły-Rydz, was a Polish politician, statesman, Marshal of Poland and Commander-in-Chief of Poland's ...

, in late August 1939 and formed a rather low opinion of his capabilities. He strongly urged Rydz-Śmigły to pull Polish forces back beyond the Vistula River

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in ...

, but was unsuccessful. The other advice he offered, to have the seagoing units of the Polish fleet leave the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

, was, after much argument, finally adopted. This fleet made a significant contribution to the Allied cause, especially the several modern destroyers and submarines.

As Polish resistance weakened, Carton de Wiart evacuated his mission from Warsaw along with the Polish government. Together with the Polish commander Rydz-Śmigły, Carton de Wiart made his way with the rest of the British Mission to the Romanian border with both the Germans and the Soviets in pursuit. His car convoy was attacked by the Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

on the road, and the wife of one of his aides

Aides may refer to:

* AIDES, a French non-governmental organization assisting people with HIV/AIDS

* ''Aides'' (skipper), a genus of skippers of family Hesperiidae

* Aides (tax), a French customs duty during the time of Louis XIV

* Hades, a Gree ...

was killed. He was in danger of arrest in Romania and got out by aircraft on 21 September with a false passport, just in time as the pro-Allied Romanian prime minister, Armand Calinescu

Armand refer to:

People

* Armand (name), list of people with this name

*Armand (photographer) (1901–1963), Armenian photographer

*Armand (singer) (1946–2015), Dutch protest singer

*Sean Armand (born 1991), American basketball player

*Armand, ...

, was assassinated that day.

Norwegian campaign (1940)

Recalled to a special appointment in the army in the autumn of 1939, Carton de Wiart reverted to his former rank of colonel. He was granted the rank of acting major general on 28 November. After a brief stint in command of the 61st Division in the English Midlands, Carton de Wiart was summoned in April 1940 to take charge of a hastily drawn together Anglo-French force to occupyNamsos

( sma, Nåavmesjenjaelmie) is a municipality in Trøndelag county, Norway. It is part of the Namdalen region. The administrative centre of the municipality is the town of Namsos. Some of the villages in the municipality include Bangsund, Kl ...

, a small town in middle Norway. His orders were to take the city of Trondheim

Trondheim ( , , ; sma, Tråante), historically Kaupangen, Nidaros and Trondhjem (), is a city and municipality in Trøndelag county, Norway. As of 2020, it had a population of 205,332, was the third most populous municipality in Norway, and ...

, 125 miles (200 km) to the south, in conjunction with a naval attack and an advance from the south by troops landed at Åndalsnes

is a town in Rauma Municipality in Møre og Romsdal county, Norway. Åndalsnes is in the administrative center of Rauma Municipality. It is located along the Isfjorden, at the mouth of the river Rauma, at the north end of the Romsdalen valley. ...

. He flew to Namsos to reconnoitre the location before the troops arrived. When his Short Sunderland

The Short S.25 Sunderland is a British flying boat patrol bomber, developed and constructed by Short Brothers for the Royal Air Force (RAF). The aircraft took its service name from the town (latterly, city) and port of Sunderland in North East ...

flying boat landed, it was attacked by a German fighter and his aide was wounded and had to be evacuated. After the French Alpine troops landed (without their transport mules and missing straps for their skis), the Luftwaffe bombed and destroyed the town of Namsos.

Despite these handicaps, Carton de Wiart managed to move his forces over the mountains and down to

Despite these handicaps, Carton de Wiart managed to move his forces over the mountains and down to Trondheimsfjord

The Trondheim Fjord or Trondheimsfjorden (), an inlet of the Norwegian Sea, is Norway's third-longest fjord at long. It is located in the west-central part of the country in Trøndelag county, and it stretches from the municipality of Ørland in ...

, where they were shelled by German destroyers. They had no artillery to challenge the German ships. It soon became apparent that the whole Norwegian campaign was fast becoming a failure. The naval attack on Trondheim, the reason for the Namsos landing, did not happen and his troops were exposed without guns, transport, air cover, or skis in a foot and a half of snow. They were being attacked by German ski troops, machine gunned and bombed from the air, and the German Navy was landing troops to his rear. He recommended withdrawal but was asked to hold his position for political reasons, which he did.

After orders and counterorders from London, the decision to evacuate was made. However, on the date set to evacuate the troops, the ships did not appear. The next night a naval force finally arrived, led through the fog by Lord Louis Mountbatten

Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979) was a British naval officer, colonial administrator and close relative of the British royal family. Mountbatten, who was of Germa ...

. The transports successfully evacuated the entire force amid heavy bombardment by the Germans, resulting in the sinking of two destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s: the French and British . Carton de Wiart arrived back at the British naval base of Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow viewed from its eastern end in June 2009

Scapa Flow (; ) is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray,S. C. George, ''Jutland to Junkyard'', 1973. South Ronaldsay and ...

in the Orkney Islands

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

on 5 May 1940, his 60th birthday.

Northern Ireland

Carton de Wiart was posted back to the command of the 61st Division, which was soon transferred toNorthern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

as a defence against invasion. However, following the arrival of Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Pownall as Commander-in-Chief in Northern Ireland, Carton de Wiart was told that he was too old to command a division on active duty.

British military mission to Yugoslavia (1941)

Advanced to temporary major-general on 28 November 1940, he remained inactive very briefly, as he was appointed as head of the British-Yugoslavian Military Mission on 5 April 1941. Hitler was preparing to invade the country and the Yugoslavs asked for British help. Carton de Wiart travelled in aVickers Wellington

The Vickers Wellington was a British twin-engined, long-range medium bomber. It was designed during the mid-1930s at Brooklands in Weybridge, Surrey. Led by Vickers-Armstrongs' chief designer Rex Pierson; a key feature of the aircraft is its g ...

bomber to Belgrade, Serbia

Belgrade ( , ;, ; names in other languages) is the capital and largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and the crossroads of the Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. Nearly 1,166,763 millio ...

to negotiate with the Yugoslavian government. After refuelling in Malta, the aircraft left for Cairo with enemy territory to the north and south. Both engines failed off the coast of Italian-controlled Libya, and the plane crash-landed in the sea about a mile from land. Carton de Wiart was knocked unconscious, but the cold water made him regain consciousness. When the plane broke up and sank, he and the rest aboard were forced to swim to shore. They were captured by the Italian authorities.

Prisoner of war in Italy (1941–1943)

Carton de Wiart was a high-profile prisoner. After four months at the Villa Orsini atSulmona

Sulmona ( nap, label= Abruzzese, Sulmóne; la, Sulmo; grc, Σουλμῶν, Soulmôn) is a city and ''comune'' of the province of L'Aquila in Abruzzo, Italy. It is located in the Valle Peligna, a plain once occupied by a lake that disappeared in ...

, he was transferred to a special prison for senior officers at Castello di Vincigliata. There were a number of senior officer prisoners here due to the successes achieved by Rommel

Johannes Erwin Eugen Rommel () (15 November 1891 – 14 October 1944) was a German field marshal during World War II. Popularly known as the Desert Fox (, ), he served in the ''Wehrmacht'' (armed forces) of Nazi Germany, as well as servi ...

in North Africa early in 1941. Carton de Wiart made friends, especially with General Sir Richard O'Connor, The 6th Earl of Ranfurly and Lieutenant-General Philip Neame

Lieutenant General Sir Philip Neame, (12 December 1888 – 28 April 1978) was a senior British Army officer and a recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Common ...

, VC.

In letters to his wife, Lord Ranfurly described Carton de Wiart in captivity as "a delightful character" and said he "must hold the record for bad language." Ranfurly was "endlessly amused by him. He really is a nice person – superbly outspoken." The four were committed to escaping. He made five attempts, including seven months tunnelling. Once Carton de Wiart evaded capture for eight days disguised as an Italian peasant (he was in northern Italy, could not speak Italian, and was 62 years old, with an eye patch, one empty sleeve and multiple injuries and scars).

Then, in a surprising development, Carton de Wiart was taken from prison in August 1943 and driven to Rome. The Italian government was secretly planning to leave the war and wanted Carton de Wiart to send the message to the British Army about a peace treaty with the UK. Carton de Wiart was to accompany an Italian negotiator, General , to Lisbon to meet Allied contacts to negotiate the surrender. To keep the mission secret, Carton de Wiart was told he needed civilian clothes. Distrusting Italian tailors, he stated that " ehad no objection provided edid not resemble a gigolo

A gigolo () is a male escort or social companion who is supported by a person in a continuing relationship, often living in her residence or having to be present at her beck and call.

The term ''gigolo'' usually implies a man who adopts a lifest ...

." In ''Happy Odyssey'', he described the resultant suit as being "as good as anything that ever came out of Savile Row

Savile Row (pronounced ) is a street in Mayfair, central London. Known principally for its traditional bespoke tailoring for men, the street has had a varied history that has included accommodating the headquarters of the Royal Geographical ...

." When they reached Lisbon, Carton de Wiart was released and made his way to England, reaching there on 28 August 1943.

China mission (1943–1947)

Within a month of his arrival back in England, Carton de Wiart was summoned to spend a night at the prime minister's country home at

Within a month of his arrival back in England, Carton de Wiart was summoned to spend a night at the prime minister's country home at Chequers

Chequers ( ), or Chequers Court, is the country house of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. A 16th-century manor house in origin, it is located near the village of Ellesborough, halfway between Princes Risborough and Wendover in Bucking ...

. Churchill informed him that he was to be sent to China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

as his personal representative. He was granted the rank of acting lieutenant-general on 9 October, and left by air for India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

on 18 October 1943. Anglo-Chinese relations were difficult in World War II as the Kuomintang had long called for the end of British extraterritorial rights in China together with the return of Hong Kong, neither proposal being welcome to Churchill. In early 1942, Churchill had to ask Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

to send Chinese troops to help the British hold Burma from the Japanese, and following the Japanese conquest of Burma the X Force

X Force was the name given to the portion of the National Revolutionary Army's Chinese Expeditionary Force that retreated from Burma into India in 1942. Chiang Kai-shek sent troops into Burma from Yunnan in 1942 to assist the British in hold ...

of five Chinese divisions had ended up in eastern India.Fenby, Jonathan ''Chiang Kai-Shek China's Generalissimo and the Nation He Lost'', New York: Carroll & Graf, 2004 page 373. Churchill was unhappy with having the X Force defend India as it weakened the prestige of the Raj, and in an attempt to improve relations with China, the prime minister felt a soldier with experience of diplomacy such as Carton de Wiart would be the best man to be his personal representative in China.

As his accommodation in China was not ready, Carton de Wiart spent time in India gaining an understanding of the situation in China, especially being briefed by a genuine ''tai-pan

A tai-pan (,Andrew J. Moody, "Transmission Languages and Source Languages of Chinese Borrowings in English", ''American Speech'', Vol. 71, No. 4 (Winter, 1996), pp. 414-415. literally "top class"汉英词典 — ''A Chinese-English Dictionary' ...

'', John Keswick

Sir John Henry Keswick, KCMG (1906–1982) was an influential Scottish businessman in China and Hong Kong. He was the tai-pan of the Jardine, Matheson & Co., the leading British trading firm in the Far East, and had established friendship with ...

, head of the great China trading empire Jardine Matheson

Jardine Matheson Holdings Limited (also known as Jardines) is a Hong Kong-based Bermuda-domiciled British multinational conglomerate. It has a primary listing on the London Stock Exchange and secondary listings on the Singapore Exchange and ...

. He met the Viceroy, Field Marshal Viscount Wavell and General Sir Claude Auchinleck

Field Marshal Sir Claude John Eyre Auchinleck, (21 June 1884 – 23 March 1981), was a British Army commander during the Second World War. He was a career soldier who spent much of his military career in India, where he rose to become Commande ...

, the Commander-in-Chief in India. He also met Orde Wingate

Major General Orde Charles Wingate, (26 February 1903 – 24 March 1944) was a senior British Army officer known for his creation of the Chindit deep-penetration missions in Japanese-held territory during the Burma Campaign of the Second World ...

." Before arriving in China, Carton de Wiart attended the 1943 Cairo Conference organized by Churchill, U.S President Roosevelt

Roosevelt may refer to:

*Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919), 26th U.S. president

* Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882–1945), 32nd U.S. president

Businesses and organisations

* Roosevelt Hotel (disambiguation)

* Roosevelt & Son, a merchant bank

* Rooseve ...

and Chinese Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

."

When in Cairo, he took the opportunity to renew his acquaintance with Hermione, Countess of Ranfurly

Hermione, Countess of Ranfurly (13 November 1913 – 11 February 2001; née Llewellyn) was a British author and aristocrat who is best known for her war memoir ''To War with Whitaker, To War With Whitaker: The Wartime Diaries of the Countess of ...

, the wife of his friend from prisoner-of-war days, Dan Ranfurly. Carton de Wiart was one of the few to be able to work with the notoriously difficult commander of US forces in the China-Burma-India Theatre, U.S Army General Joseph Stilwell

Joseph Warren "Vinegar Joe" Stilwell (March 19, 1883 – October 12, 1946) was a United States Army general who served in the China Burma India Theater during World War II. An early American popular hero of the war for leading a column walking ...

." He arrived in the headquarters of the Nationalist Chinese Government, Chungking

Chongqing ( or ; ; Sichuanese pronunciation: , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), alternately romanized as Chungking (), is a municipality in Southwest China. The official abbreviation of the city, "" (), was approved by the State Counc ...

(Chongqing), in early December 1943. For the next three years, he was to be involved in a host of reporting, diplomatic and administrative duties in the remote wartime capital. Carton de Wiart became a great admirer of the Chinese people. He wrote that, when he was appointed as Churchill's personal representative to Chiang Kai-shek in China, he imagined a country "full of whimsical little people with quaint customs who carved lovely jade ornaments and worshiped their grandmothers". Once stationed in China, however, he wrote: 'Two things struck me forcibly: the first was the amount of sheer hard work the people were doing, and the second their cheerfulness in doing it.'

He regularly flew out to India to liaise with British officials. His old friend, Richard O'Connor, had escaped from the Italian prisoner-of-war camp and was now in command of British troops in eastern India. The

He regularly flew out to India to liaise with British officials. His old friend, Richard O'Connor, had escaped from the Italian prisoner-of-war camp and was now in command of British troops in eastern India. The Governor of Bengal

The Governor was the chief colonial administrator in the Bengal presidency, originally the "Presidency of Fort William" and later "Bengal province".

In 1644, Gabriel Boughton procured privileges for the East India Company which permitted them to ...

, the Australian Richard Casey, became a good friend.

On 9 October 1944, Carton de Wiart was promoted to temporary lieutenant-general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

and to the war substantive rank of major-general. Carton de Wiart returned home in December 1944 to report to the War Cabinet

A war cabinet is a committee formed by a government in a time of war to efficiently and effectively conduct that war. It is usually a subset of the full executive cabinet of ministers, although it is quite common for a war cabinet to have senior ...

on the Chinese situation. He was appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established ...

(KBE) in the 1945 New Year Honours

The 1945 New Year Honours were appointments by many of the Commonwealth realms of King George VI to various orders and honours to reward and highlight good works by citizens of those countries. They were announced on 1 January 1945 for the British ...

. Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Mini ...

, when he became head of the Labour Government in June 1945, asked Carton de Wiart to stay on in China.

South East Asia

Carton de Wiart was assigned to a tour of the Burma Front, and after meeting Admiral SirJames Somerville

Admiral of the Fleet Sir James Fownes Somerville, (17 July 1882 – 19 March 1949) was a Royal Navy officer. He served in the First World War as fleet wireless officer for the Mediterranean Fleet where he was involved in providing naval supp ...

, Commander-in-Chief of the British Eastern Fleet

The East Indies Station was a formation and command of the British Royal Navy. Created in 1744 by the Admiralty, it was under the command of the Commander-in-Chief, East Indies.

Even in official documents, the term ''East Indies Station'' was ...

, he was given a front seat on the bridge of the battleship for the bombardment of Sabang in the Netherlands East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, which ...

in 1945, including air battles between Japanese fighters and British carrier aircraft.

A good part of Carton de Wiart's reporting had to do with the increasing power of the

A good part of Carton de Wiart's reporting had to do with the increasing power of the Chinese Communists

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Ci ...

. The journalist and historian Max Hastings

Sir Max Hugh Macdonald Hastings (; born 28 December 1945) is a British journalist and military historian, who has worked as a foreign correspondent for the BBC, editor-in-chief of ''The Daily Telegraph'', and editor of the ''Evening Standard' ...

writes: "De Wiart despised all Communists on principle, denounced Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the founder of the People's Republic of China (PRC) ...

as 'a fanatic', and added: 'I cannot believe he means business'. He told the British cabinet that there was no conceivable alternative to Chiang as ruler of China." He met Mao Zedong at dinner and had a memorable exchange with him, interrupting his propaganda speech to criticise him for holding back from fighting the Japanese for domestic political reasons. Mao was briefly stunned, and then laughed.

After the Japanese surrender in August 1945, Carton de Wiart flew to Singapore to participate in the formal surrender. After a visit to Peking

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

, he moved to Nanking

Nanjing (; , Mandarin pronunciation: ), alternately romanized as Nanking, is the capital of Jiangsu province of the People's Republic of China. It is a sub-provincial city, a megacity, and the second largest city in the East China region. T ...

, the now-liberated Nationalist capital, accompanied by Julian Amery

Harold Julian Amery, Baron Amery of Lustleigh, (27 March 1919 – 3 September 1996) was a British Conservative Party politician, who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) for 39 of the 42 years between 1950 and 1992. He was appointed to the Pr ...

, the British Prime Minister's Personal Representative to Chiang. A visit to Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.468 ...

to meet General Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was C ...

came at the end of his tenure. He was now 66 and ready to retire, despite the offer of a job by Chiang. Carton de Wiart retired in October 1947, with the honorary rank of lieutenant-general.

Retirement and death

En route home viaFrench Indochina

French Indochina (previously spelled as French Indo-China),; vi, Đông Dương thuộc Pháp, , lit. 'East Ocean under French Control; km, ឥណ្ឌូចិនបារាំង, ; th, อินโดจีนฝรั่งเศส, ...

, Carton de Wiart stopped in Rangoon

Yangon ( my, ရန်ကုန်; ; ), formerly spelled as Rangoon, is the capital of the Yangon Region and the largest city of Myanmar (also known as Burma). Yangon served as the capital of Myanmar until 2006, when the military government ...

as a guest of the army commander. Coming down stairs, he slipped on coconut matting, fell down, broke several vertebrae, and knocked himself unconscious. He was admitted to Rangoon Hospital where he was treated. His wife died in 1949. In 1951, at the age of 71, he married Ruth Myrtle Muriel Joan McKechnie, a divorcee known as Joan Sutherland, 23 years his junior (born in late 1903, she died 13 January 2006 at the age of 102.) They settled at Aghinagh House, Killinardrish, County Cork

County Cork ( ga, Contae Chorcaí) is the largest and the southernmost county of Ireland, named after the city of Cork, the state's second-largest city. It is in the province of Munster and the Southern Region. Its largest market towns are ...

, Ireland.

Carton de Wiart died at the age of 83 on 5 June 1963. He left no papers. He and his wife Joan are buried in Caum Churchyard just off the main Macroom road. The grave site is just outside the actual graveyard wall on the grounds of his own home, Aghinagh House. Carton de Wiart's will was valued at probate

Probate is the judicial process whereby a will is "proved" in a court of law and accepted as a valid public document that is the true last testament of the deceased, or whereby the estate is settled according to the laws of intestacy in the sta ...

in Ireland at £4,158 and in England at £3,496.

Publications

* ''Happy Odyssey: The Memoirs of Lieutenant-General Sir Adrian Carton de Wiart'', Jonathan Cape, 1950.Awards and decorations

Carton de Wiart was the recipient of several awards:In popular culture

Carton de Wiart is the subject of the 2022 song "The Unkillable Soldier" by Swedish heavy metal bandSabaton

A sabaton or solleret is part of a knight's body armor that covers the foot.

History

Fourteenth and fifteenth century sabatons typically end in a tapered point well past the actual toes of the wearer's foot, following fashionable shoe shapes o ...

on their album ''The War to End all Wars

"The war to end war" (also "The war to end all wars"; originally from the 1914 book '' The War That Will End War'' by H. G. Wells) is a term for the First World War of 1914–1918. Originally an idealistic slogan, it is now mainly used sardonic ...

''.

See also

*Jack Churchill

John Malcolm Thorpe Fleming Churchill, (16 September 1906 – 8 March 1996) was a British Army officer who fought in the Second World War with a longbow, a Scottish broadsword, and a bagpipe. Nicknamed "Fighting Jack Churchill" and "Mad Jack" ...

, another notably eccentric British soldier

References

Sources

* * *Further reading

* Boatner, Mark, (1999), ''The Biographical Dictionary of World War II'', Presidio Press, Novato, California. * Buzzell, Nora (1997), ''The Register of the Victoria Cross'', This England. * Davies, Norman, (2003) ''White Eagle, Red Star: The Polish-Soviet War 1919–1920'', Pimlico Edition, London. * Davies, Norman, (2003) ''The Miracle on the Vistula"'', Pimlico Edition, London. * Doherty, Richard; Truesdale, David, (2000) ''Irish Winners of the Victoria Cross'' * Foot, M.R.D. & Langley, J.M., ''MI9 Escape & Evasion 1939–45'', The Bodley Head, 1979, 365 pages * Gliddon, Gerald (1994), ''VCs of the First World War – The Somme''. * Hargest, Brigadier, James C.B.E., D.S.O. M.C., ''Farewell Campo 12'', Michael Joseph Ltd, 1945, 184 pages contains a sketch map of Castello Vincigliata page 85, route of capture and escape 'Sidi Azir – London (inside front cover),(no index) * Harvey, David, (1999), ''Monuments to Courage''. * Leeming, John F (1951) ''Always To-Morrow'', George G Harrap & Co. Ltd, London, 188p, Illustrated with photographs and maps * Neame, Sir Philip Lt-Gen. V.C., K.B.E., C.B., D.S.O., ''Playing with Strife'', The Autobiography of a Soldier, George G Harrap & Co. Ltd, 1947, 353 pages, (written whilst a POW, the best narrative of Vincigliata as Campo PG12, contains a scale plan of Castello di Vincigliata, and photographs taken by the author just after the war) * Williams, E. T"Carton de Wiart, Sir Adrian (1880–1963)"

rev. G. D. Sheffield, ''

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'', Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print books ...

, 2004, . Online version retrieved on 6 February 2009.

External links

*Location of grave and VC medal

''(Co. Cork)'' *

* , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Carton de Wiart, Adrian 1880 births 1963 deaths People educated at The Oratory School Alumni of Balliol College, Oxford Military personnel from Brussels British Army personnel of the Second Boer War British World War I recipients of the Victoria Cross British Battle of the Somme recipients of the Victoria Cross British amputees British anti-communists British Army generals of World War II Polish generals British Army cavalry generals of World War I World War II prisoners of war held by Italy British escapees English Roman Catholics Escapees from Italian detention Companions of the Distinguished Service Order Companions of the Order of the Bath Companions of the Order of St Michael and St George Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire Recipients of the Virtuti Militari British World War II prisoners of war 4th Royal Irish Dragoon Guards officers Imperial Light Horse officers Somaliland Camel Corps officers British Army recipients of the Victoria Cross Belgian people of Irish descent Belgian emigrants to the United Kingdom Naturalised citizens of the United Kingdom British expatriates in Poland Military personnel from Cairo British Army lieutenant generals