The Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley occurred from the 6th to 4th centuries BCE, and saw the Persian

Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

take control of regions in the northwestern

Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

that predominantly comprise the territory of modern-day

Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

. The first of two main invasions was conducted around 535 BCE by the empire's founder,

Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia (; peo, 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 ), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, the first Persian empire. Schmitt Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Under his rule, the empire embraced ...

, who annexed the regions west of the

Indus River

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

that formed the eastern border of the Achaemenid Empire. Following Cyrus' death,

Darius the Great

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his d ...

established his dynasty and began to re-conquer former provinces and further expand the empire. Around 518 BCE, Persian armies under Darius crossed the

Himalayas

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over 100 ...

into

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

to initiate a second period of conquest by annexing regions up to the

Jhelum River

The Jhelum River (/dʒʰeːləm/) is a river in the northern Indian subcontinent. It originates at Verinag and flows through the Indian administered territory of Jammu and Kashmir, to the Pakistani-administered territory of Kashmir, and then ...

in

Punjab

Punjab (; Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising ...

.

The first secure epigraphic evidence through the

Behistun Inscription gives a date before or around 518 BCE. Achaemenid penetration into the Indian subcontinent occurred in stages, starting from northern parts of the Indus River and moving southward. The Indus Valley was formally incorporated into the Achaemenid Empire as the

satrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median and Achaemenid Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic empires.

The satrap served as viceroy to the king, though with consid ...

ies of

Gandāra

Gandāra, or Gadāra in Achaemenid inscriptions (Old Persian cuneiform: 𐎥𐎭𐎠𐎼, , also transliterated as since the nasal "n" before consonants was omitted in the Old Persian script, and simplified as or sometimes )Some sounds are o ...

,

Hindush

Hindush (Old Persian cuneiform: 𐏃𐎡𐎯𐎢𐏁, , transcribed as since the nasal "n" before consonants was omitted in the Old Persian script, and simplified as ) was a province of the Achaemenid Empire in lower Indus Valley established a ...

, and

Sattagydia

Sattagydia (Old Persian: 𐎰𐎫𐎦𐎢𐏁 ''Thataguš'', country of the "hundred cows") was one of the easternmost regions of the Achaemenid Empire, part of its Seventh tax district according to Herodotus, along with Gandārae, Dadicae and ...

, as mentioned in several Achaemenid-era Persian inscriptions.

Achaemenid rule over the Indus Valley decreased over successive rulers and formally ended around the time of the

Macedonian conquest of Persia under

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

. This gave rise to independent kings such as

Abisares

Abisares (or Abhisara; in Greek Ἀβισάρης), called Embisarus (Ἐμβίσαρος,) by Diodorus, was a king of Abhira descent whose territory lay in the river Hydaspes beyond the mountains. On his death in 325 Alexander appointed Abisare ...

,

Porus

Porus or Poros ( grc, Πῶρος ; 326–321 BC) was an ancient Indian king whose territory spanned the region between the Jhelum River (Hydaspes) and Chenab River (Acesines), in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent. He is only ment ...

(ruler of the region between the Jhelum and

Chenab

The Chenab River () is a major river that flows in India and Pakistan, and is one of the 5 major rivers of the Punjab region. It is formed by the union of two headwaters, Chandra and Bhaga, which rise in the upper Himalayas in the Lahaul regi ...

rivers),

Ambhi

Taxiles (in Greek Tαξίλης or Ταξίλας; lived 4th century BC) was the Greek chroniclers' name for the ruler who reigned over the tract between the Indus and the Jhelum (Hydaspes) Rivers in the Punjab region at the time of Alexander t ...

(ruler of the region between the Indus and Jhelum rivers with its capital at

Taxila

Taxila or Takshashila (; sa, तक्षशिला; pi, ; , ; , ) is a city in Punjab, Pakistan. Located in the Taxila Tehsil of Rawalpindi District, it lies approximately northwest of the Islamabad–Rawalpindi metropolitan area and ...

) as well as

s, or republics, which later confronted Alexander during his

Indian campaign around 323 BCE. The Achaemenid Empire set a precedence of governance through the use of satrapies, which was further implemented by Alexander's

Macedonian Empire

Macedonia (; grc-gre, Μακεδονία), also called Macedon (), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, and later the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by ...

, the

Indo-Scythians

Indo-Scythians (also called Indo-Sakas) were a group of nomadic Iranian peoples of Scythian origin who migrated from Central Asia southward into modern day Pakistan and Northwestern India from the middle of the 2nd century BCE to the 4th centur ...

, and the

Kushan Empire

The Kushan Empire ( grc, Βασιλεία Κοσσανῶν; xbc, Κυϸανο, ; sa, कुषाण वंश; Brahmi: , '; BHS: ; xpr, 𐭊𐭅𐭔𐭍 𐭇𐭔𐭕𐭓, ; zh, 貴霜 ) was a syncretic empire, formed by the Yuezhi, i ...

.

Background and invasion

For millennia, the northwestern part of India had maintained some level of

trade relations with the Near East. Finally, the

Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

underwent a considerable expansion, both east and west, during the reign of

Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia (; peo, 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 ), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, the first Persian empire. Schmitt Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Under his rule, the empire embraced ...

(c.600–530 BC), leading the dynasty to take a direct interest into the region of northwestern India.

;Cyrus the Great

The conquest is often thought to have started circa 535 BCE, during the time of

Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia (; peo, 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 ), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, the first Persian empire. Schmitt Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Under his rule, the empire embraced ...

(600-530 BCE). Cyrus probably went as far as the banks of the

Indus river

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

and organized the conquered territories under the Satrapy of ''Gandara'' (

Old Persian

Old Persian is one of the two directly attested Old Iranian languages (the other being Avestan language, Avestan) and is the ancestor of Middle Persian (the language of Sasanian Empire). Like other Old Iranian languages, it was known to its native ...

cuneiform:

𐎥𐎭𐎠𐎼, ''Gadāra'', also transliterated as ''Ga

ndāra'' since the nasal "n" before consonants was omitted in the Old Persian script, and simplified as ''Gandara'')

[Some sounds are omitted in the writing of Old Persian, and are shown with a raised lette]

Old Persian p.164

https://archive.org/stream/OldPersian#page/n23/mode/2up/ Old Persian p.13]. In particular Old Persian nasals such as "n" were omitted in writing before consonant

Old Persian p.17

https://archive.org/stream/OldPersian#page/n35/mode/2up/ Old Persian p.25] according to the

Behistun Inscription.

The Province was also referred to as ''

Paruparaesanna

Paropamisadae or Parapamisadae (Greek: Παροπαμισάδαι) was a satrapy of the Alexandrian Empire in modern Afghanistan and Pakistan, which largely coincided with the Achaemenid province of Parupraesanna. It consisted of the districts ...

'' (Greek: Parapamisadae) in the

Babylonian and

Elamite

Elamite, also known as Hatamtite and formerly as Susian, is an extinct language that was spoken by the ancient Elamites. It was used in what is now southwestern Iran from 2600 BC to 330 BC. Elamite works disappear from the archeological record ...

versions of the Behistun inscription.

[Perfrancesco Callieri]

INDIA ii. Historical Geography

Encyclopaedia Iranica, 15 December 2004. The geographical extent of this province was wider than the Indian

Gandhara

Gandhāra is the name of an ancient region located in the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent, more precisely in present-day north-west Pakistan and parts of south-east Afghanistan. The region centered around the Peshawar Vall ...

. Various accounts, such as those of

Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, wikt:Ξενοφῶν, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Anci ...

or

Ctesias

Ctesias (; grc-gre, Κτησίας; fl. fifth century BC), also known as Ctesias of Cnidus, was a Greek physician and historian from the town of Cnidus in Caria, then part of the Achaemenid Empire.

Historical events

Ctesias, who lived in the fi ...

, who wrote ''

Indica'', also suggest that Cyrus conquered parts of India.

[Tauqeer Ahmad, University of the Punjab, Lahore, South Asian Studies, A Research Journal of South Asian Studies, Vol. 27, No. 1, January–June 2012, pp. 221-23]

p.222

/ref> Another Indian Province was conquered named Sattagydia

Sattagydia (Old Persian: 𐎰𐎫𐎦𐎢𐏁 ''Thataguš'', country of the "hundred cows") was one of the easternmost regions of the Achaemenid Empire, part of its Seventh tax district according to Herodotus, along with Gandārae, Dadicae and ...

( 𐎰𐎫𐎦𐎢𐏁, ''Thataguš'') in the Behistun inscription. It was probably contiguous to Gandhara, but its actual location is uncertain. Fleming locates it between Arachosia

Arachosia () is the Hellenized name of an ancient satrapy situated in the eastern parts of the Achaemenid empire. It was centred around the valley of the Arghandab River in modern-day southern Afghanistan, and extended as far east as the In ...

and the middle Indus

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

. Fleming also mentions Maka Maka or MAKA may refer to:

* Maká, a Native American people in Paraguay

** Maká language, spoken by the Maká

* Maka (satrapy), a province of the Achaemenid Empire

* Maka, Biffeche, capital of the kingdom of Biffeche in pre-colonial Senegal

* M ...

, in the area of Gedrosia

Gedrosia (; el, Γεδρωσία) is the Hellenization, Hellenized name of the part of coastal Balochistan that roughly corresponds to today's Makran. In books about Alexander the Great and his Diadochi, successors, the area referred to as Gedro ...

, as one of the Indian satrapies.Darius I

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his ...

was back in 518 BCE. The date of 518 BCE is given by the Behistun inscription, and is also often the one given for the secure occupation of Gandhara

Gandhāra is the name of an ancient region located in the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent, more precisely in present-day north-west Pakistan and parts of south-east Afghanistan. The region centered around the Peshawar Vall ...

in Punjab. Darius I later conquered an additional province that he calls ''"Hidūš"'' in his inscriptions (Old Persian cuneiform

Old Persian cuneiform is a semi-alphabetic cuneiform script that was the primary script for Old Persian. Texts written in this cuneiform have been found in Iran (Persepolis, Susa, Hamadan, Kharg Island), Armenia, Romania (Gherla), Turkey ( Van Fo ...

: 𐏃𐎡𐎯𐎢𐏁, ''H-i-du-u-š'', also transliterated as ''Hindūš'' since the nasal "n" before consonants was omitted in the Old Persian script, and simplified as ''Hindush''), corresponding to the Indus Valley

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

. The exact area of the Province of ''Hindush'' is uncertain. Some scholars have described it as the middle and lower

The exact area of the Province of ''Hindush'' is uncertain. Some scholars have described it as the middle and lower Indus Valley

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

and the approximate region of modern Sindh

Sindh (; ; ur, , ; historically romanized as Sind) is one of the four provinces of Pakistan. Located in the southeastern region of the country, Sindh is the third-largest province of Pakistan by land area and the second-largest province ...

, but there is no known evidence of Achaemenid presence in this region, and deposits of gold, which Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known f ...

says was produced in vast quantities by this Province, are also unknown in the Indus delta region.["The region was soon to appear as Hindūš in the Old Persian inscriptions... Transparent though the name appears at first sight, its location is not without problems. Foucher, Kent and many subsequent writers have identified Hindūš with its ethymological equivalent , Sind, thereby placing it on the lower Indus towards the delta. However, (...) no material evidence of Achaemenid activity in this region is so far available. (...) There seems no evidence at present of gold production in the Indus delta, so this detail seems to weight against the location of the Hindūš province in Sind. (...) The alternative location to Sind for an Achaemenid province of Hindūš is naturally at Taxila and in the West Punjab, where there are indications that a Persian satrapy may have existed, though no clear evidence of its name." in ] Alternatively, ''Hindush'' may have been the region of Taxila

Taxila or Takshashila (; sa, तक्षशिला; pi, ; , ; , ) is a city in Punjab, Pakistan. Located in the Taxila Tehsil of Rawalpindi District, it lies approximately northwest of the Islamabad–Rawalpindi metropolitan area and ...

and Western Punjab

Punjab (; Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising ...

, where there are indications that a Persian satrapy may have existed.Bhir Mound

The Bhir Mound ( ur, ) is an archaeological site in Taxila in the Punjab province of Pakistan. It contains some of the oldest ruins of Ancient Taxila, dated to sometime around the period 800-525 BC as its earliest layers bear "grooved" Red B ...

in Taxila

Taxila or Takshashila (; sa, तक्षशिला; pi, ; , ; , ) is a city in Punjab, Pakistan. Located in the Taxila Tehsil of Rawalpindi District, it lies approximately northwest of the Islamabad–Rawalpindi metropolitan area and ...

remains the "most plausible candidate for the capital of Achaemenid India", based on the fact that numerous pottery styles similar to those of the Achaemenids in the East have been found there, and that "there are no other sites in the region with Bhir Mound's potential".

According to Herodotus, Darius I sent the Greek explorer Scylax of Caryanda

Scylax of Caryanda ( el, Σκύλαξ ὁ Καρυανδεύς) was a Greek explorer and writer of the late 6th and early 5th centuries BCE. His own writings are lost, though occasionally cited or quoted by later Greek and Roman authors. The peri ...

to sail down the Indus river

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

, heading a team of spies, in order to explore the course of the Indus river. After a periplus of 30 months, Scylax is said to have returned to Egypt near the Red Sea, and the seas between the Near East and India were made use of by Darius.

Also according to Herodotus, the territories of Gandhara, Sattagydia, Dadicae and Aparytae formed the 7th province of the Achaemenid Empire for tax-payment purposes, while ''Indus'' (called ''Ἰνδός'', "Indos" in Greek sources) formed the 20th tax region.

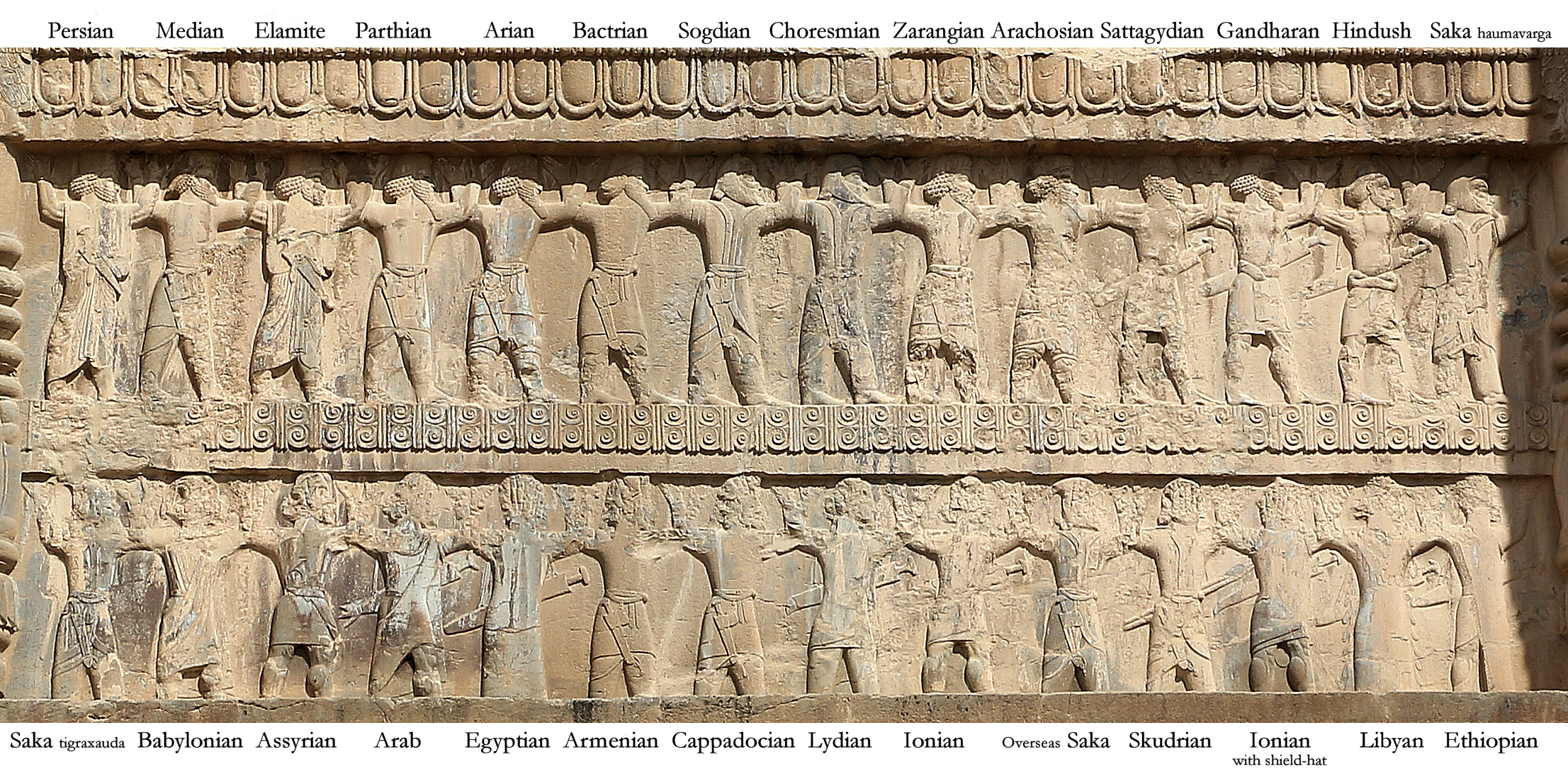

;Achaemenid army

Throughout its existence, the Achaemenid were constantly engaging in wars. Either through conquering new territories or by quelling rebellions throughout the empire. To fulfil this need, the Achaemenid Empire had to maintain a professional standing army which levied and employed personnel from all of its satraps and territories.

The Achaemenid army was not uniquely Persian. Rather it was composed of many different ethnicities that were part of the vast and diverse Achaemenid Empire. Herodotus gives a full list of the ethnicities of the Achaemenid army, in which are included

Throughout its existence, the Achaemenid were constantly engaging in wars. Either through conquering new territories or by quelling rebellions throughout the empire. To fulfil this need, the Achaemenid Empire had to maintain a professional standing army which levied and employed personnel from all of its satraps and territories.

The Achaemenid army was not uniquely Persian. Rather it was composed of many different ethnicities that were part of the vast and diverse Achaemenid Empire. Herodotus gives a full list of the ethnicities of the Achaemenid army, in which are included Bactrians

Bactria (; Bactrian: , ), or Bactriana, was an ancient region in Central Asia in Amu Darya's middle stream, stretching north of the Hindu Kush, west of the Pamirs and south of the Gissar range, covering the northern part of Afghanistan, southwe ...

, Sakas

The Saka (Old Persian: ; Kharosthi, Kharoṣṭhī: ; Egyptian language, Ancient Egyptian: , ; , Old Chinese, old , Pinyin, mod. , ), Shaka (Sanskrit (Brahmi script, Brāhmī): , , ; Sanskrit (Devanagari, Devanāgarī): , ), or Sacae (An ...

(Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an Ancient Iranian peoples, ancient Eastern Iranian languages, Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved f ...

), Parthia

Parthia ( peo, 𐎱𐎼𐎰𐎺 ''Parθava''; xpr, 𐭐𐭓𐭕𐭅 ''Parθaw''; pal, 𐭯𐭫𐭮𐭥𐭡𐭥 ''Pahlaw'') is a historical region located in northeastern Greater Iran. It was conquered and subjugated by the empire of the Med ...

ns, Sogdians :''This category lists articles related to historical Iranian peoples''

Historical

Peoples

Iranian

Iranian

Iranian

Iranian may refer to:

* Iran, a sovereign state

* Iranian peoples, the speakers of the Iranian languages. The term Iranic peoples ...

.[

] Ionians

The Ionians (; el, Ἴωνες, ''Íōnes'', singular , ''Íōn'') were one of the four major tribes that the Greeks considered themselves to be divided into during the ancient period; the other three being the Dorians, Aeolians, and Achae ...

(Greeks), Egyptians

Egyptians ( arz, المَصرِيُون, translit=al-Maṣriyyūn, ; arz, المَصرِيِين, translit=al-Maṣriyyīn, ; cop, ⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ, remenkhēmi) are an ethnic group native to the Nile, Nile Valley in Egypt. Egyptian ...

, Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

ns, etc.

Inscriptions and accounts

These events were recorded in the imperial inscriptions of the Achaemenids (the Behistun inscription and the Naqsh-i-Rustam inscription, as well as the accounts of Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known f ...

(483–431 BCE). The Greek Scylax of Caryanda, who had been appointed by Darius I to explore the Indian Ocean from the mouth of the Indus to Suez left an account, the ''Periplous'', of which fragments from secondary sources have survived. Hecataeus of Miletus

Hecataeus of Miletus (; el, Ἑκαταῖος ὁ Μιλήσιος; c. 550 BC – c. 476 BC), son of Hegesander, was an early Greek historian and geographer.

Biography

Hailing from a very wealthy family, he lived in Miletus, then under Per ...

(circa 500 BCE) also wrote about the "Indus Satrapies" of the Achaemenids.

Behistun inscription

The 'DB' Behistun inscription of Darius I

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his ...

(circa 510 BCE) mentions Gandara ( 𐎥𐎭𐎠𐎼, ''Gadāra'') and the adjacent territory of Sattagydia

Sattagydia (Old Persian: 𐎰𐎫𐎦𐎢𐏁 ''Thataguš'', country of the "hundred cows") was one of the easternmost regions of the Achaemenid Empire, part of its Seventh tax district according to Herodotus, along with Gandārae, Dadicae and ...

( 𐎰𐎫𐎦𐎢𐏁, ''Thataguš'') as part of the Achaemenid Empire:

From the dating of the Behistun inscription, it is possible to infer that the Achaemenids first conquered the areas of Gandara and Sattagydia circa 518 BCE.

Statue of Darius inscriptions

Hinduš is also mentioned as one of 24 subject countries of the Achaemenid Empire, illustrated with the drawing of a kneeling subject and a hieroglyphic

Egyptian hieroglyphs (, ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt, used for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with some 1,000 distinct characters.There were about 1,00 ...

cartridge reading 𓉔𓈖𓂧𓍯𓇌 (''h-n-d- wꜣ-y''), on the Egyptian Statue of Darius I, now in the National Museum of Iran

The National Museum of Iran ( fa, موزهٔ ملی ایران ) is located in Tehran, Iran. It is an institution formed of two complexes; the Museum of Ancient Iran and the Museum of Islamic Archaeology and Art of Iran, which were opened in 1937 ...

. Sattagydia also appears ( 𓐠𓂧𓎼𓍯𓍒, ''sꜣ-d-g- wꜣ-ḏꜣ'', Sattagydia), and probably Gandara ( 𓉔𓃭𓐍𓂧𓇌, ''h-rw-ḫ-d-y'', although this could be Arachosia

Arachosia () is the Hellenized name of an ancient satrapy situated in the eastern parts of the Achaemenid empire. It was centred around the valley of the Arghandab River in modern-day southern Afghanistan, and extended as far east as the In ...

), with their own illustrations.

Apadana Palace foundation tablets

Four identical foundation tablets of gold and silver, found in two deposition boxes in the foundations of the

Four identical foundation tablets of gold and silver, found in two deposition boxes in the foundations of the Apadana Palace

, native_name_lang =

, alternate_name =

, image = Gate of All Nations, Persepolis.jpg

, image_size =

, alt =

, caption = Ruins of the Gate of All Nations, Persepolis.

, map =

, map_type ...

, also contained an inscription by Darius I in Old Persian cuneiform

Old Persian cuneiform is a semi-alphabetic cuneiform script that was the primary script for Old Persian. Texts written in this cuneiform have been found in Iran (Persepolis, Susa, Hamadan, Kharg Island), Armenia, Romania (Gherla), Turkey ( Van Fo ...

, which describes the extent of his Empire in broad geographical terms, from the Indus valley

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

in the east to Lydia

Lydia (Lydian language, Lydian: 𐤮𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣𐤠, ''Śfarda''; Aramaic: ''Lydia''; el, Λυδία, ''Lȳdíā''; tr, Lidya) was an Iron Age Monarchy, kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient Ionia in the mod ...

in the west, and from the Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an Ancient Iranian peoples, ancient Eastern Iranian languages, Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved f ...

beyond Sogdia

Sogdia (Sogdian language, Sogdian: ) or Sogdiana was an ancient Iranian peoples, Iranian civilization between the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya, and in present-day Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. Sogdiana was also ...

in the north, to the African Kingdom of Kush

The Kingdom of Kush (; Egyptian language, Egyptian: 𓎡𓄿𓈙𓈉 ''kꜣš'', Akkadian language, Assyrian: ''Kûsi'', in LXX grc, Κυς and Κυσι ; cop, ''Ecōš''; he, כּוּשׁ ''Kūš'') was an ancient kingdom in Nubia, ce ...

in the south. This is known as the DPh inscription.

Naqsh-e Rustam inscription

The DSe inscriptionOld Persian cuneiform

Old Persian cuneiform is a semi-alphabetic cuneiform script that was the primary script for Old Persian. Texts written in this cuneiform have been found in Iran (Persepolis, Susa, Hamadan, Kharg Island), Armenia, Romania (Gherla), Turkey ( Van Fo ...

) also appears later as a Satrapy in the Naqsh-i-Rustam inscription at the end of the reign of Darius, who died in 486 BCE.Persepolis

, native_name_lang =

, alternate_name =

, image = Gate of All Nations, Persepolis.jpg

, image_size =

, alt =

, caption = Ruins of the Gate of All Nations, Persepolis.

, map =

, map_type ...

records ''Gadāra'' (Gandāra) along with ''Hiduš'' and ''Thataguš'' (Sattagydia

Sattagydia (Old Persian: 𐎰𐎫𐎦𐎢𐏁 ''Thataguš'', country of the "hundred cows") was one of the easternmost regions of the Achaemenid Empire, part of its Seventh tax district according to Herodotus, along with Gandārae, Dadicae and ...

) in the list of satrapies.

Strabo

The extent of Achaemenid territories is also affirmed by Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

in his "Geography" (Book XV), describing the Persian holdings along the Indus:

Achaemenid administration

The nature of the administration under the Achaemenids is uncertain. Even though the Indian provinces are called "satrapies" by convention, there is no evidence of there being any satraps in these provinces. When Alexander invaded the region, he did not encounter Achaemenid satraps in the Indian provinces, but local Indian rulers referred to as ''hyparchs'' ("Vice-Regents"), a term that connotes subordination to the Achaemenid rulers. The local rulers may have reported to the satraps of Bactria and Arachosia.

;Achaemenid lists of Provinces

Darius I listed three Indian provinces: ''

The nature of the administration under the Achaemenids is uncertain. Even though the Indian provinces are called "satrapies" by convention, there is no evidence of there being any satraps in these provinces. When Alexander invaded the region, he did not encounter Achaemenid satraps in the Indian provinces, but local Indian rulers referred to as ''hyparchs'' ("Vice-Regents"), a term that connotes subordination to the Achaemenid rulers. The local rulers may have reported to the satraps of Bactria and Arachosia.

;Achaemenid lists of Provinces

Darius I listed three Indian provinces: ''Sattagydia

Sattagydia (Old Persian: 𐎰𐎫𐎦𐎢𐏁 ''Thataguš'', country of the "hundred cows") was one of the easternmost regions of the Achaemenid Empire, part of its Seventh tax district according to Herodotus, along with Gandārae, Dadicae and ...

'' (''Thataguš)'', ''Gandāra

Gandāra, or Gadāra in Achaemenid inscriptions (Old Persian cuneiform: 𐎥𐎭𐎠𐎼, , also transliterated as since the nasal "n" before consonants was omitted in the Old Persian script, and simplified as or sometimes )Some sounds are o ...

'' (Gandhara) and '' Hidūš'' (Sind),Indus Valley

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

".Swat District

Swat District (, ps, سوات ولسوالۍ, ) is a district in the Malakand Division of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. With a population of 2,309,570 per the 2017 national census, Swat is the 15th-largest district of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa prov ...

in the north, Afghanistan in the West, the Indus River to the south east, and Kohat District

Kohat District ( ps, کوهاټ ولسوالۍ , ur, ) is a district in Kohat Division of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province in Pakistan. Kohat city is the capital of the district.

History Mughal era

From the early sixteenth century the history of Ko ...

in the south.Pushkalavati

Pushkalavati ( ps, پشکلاوتي; Urdu: ; Sanskrit: ; Prākrit: ; grc, Πευκελαῶτις ) or Pushkaravati (Sanskrit: ; Pāli: ), and later Shaikhan Dheri ( ps, شېخان ډېرۍ; ur, ), was the capital of the Gandhara kingdom, ...

. Archeological excavations of Pushkalavati were conducted by Mortimer Wheeler

Sir Robert Eric Mortimer Wheeler CH CIE MC TD (10 September 1890 – 22 July 1976) was a British archaeologist and officer in the British Army. Over the course of his career, he served as Director of both the National Museum of Wales an ...

in 1962 who discovered structures built during the Achaemenid period as well as artifacts.Hazara region

Hazara (Hindko: هزاره, Urdu: ) is a region in northeastern Pakistan, falling administratively within Hazara Division of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. It is dominated mainly by the Hindko-speaking Hindkowan people, who are the native ethni ...

to the north, the Indus River to the west, and the Jhelum River in the south and east. The satrapy's capital was Bhir Mound

The Bhir Mound ( ur, ) is an archaeological site in Taxila in the Punjab province of Pakistan. It contains some of the oldest ruins of Ancient Taxila, dated to sometime around the period 800-525 BC as its earliest layers bear "grooved" Red B ...

in Takshashila

Taxila or Takshashila (; sa, तक्षशिला; pi, ; , ; , ) is a city in Punjab, Pakistan. Located in the Taxila Tehsil of Rawalpindi District, it lies approximately northwest of the Islamabad–Rawalpindi metropolitan area and ...

(Taxila).John Marshall

John Marshall (September 24, 1755July 6, 1835) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the fourth Chief Justice of the United States from 1801 until his death in 1835. He remains the longest-serving chief justice and fourth-longes ...

between 1913 and 1934. Fortified structures and canals were found dating to the Achaemenid period, as well as ornamental jewelry.Darius III

Darius III ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; c. 380 – 330 BC) was the last Achaemenid King of Kings of Persia, reigning from 336 BC to his death in 330 BC.

Contrary to his predecessor Artaxerxes IV Arses, Dar ...

who was vanquished by Alexander at Gaugamela, suggesting that the Indians were under Achaemenid dominion at least until 338 BCE, date of the end of the reign of Artaxerxes III

Ochus ( grc-gre, Ὦχος ), known by his dynastic name Artaxerxes III ( peo, 𐎠𐎼𐎫𐎧𐏁𐏂𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ἀρταξέρξης), was King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 359/58 to 338 BC. He was the son and successor of A ...

, before the accession of Darius III, that is, less than 10 years before the campaigns of Alexander in the East and his victory at Gaugamela

The Battle of Gaugamela (; grc, Γαυγάμηλα, translit=Gaugámela), also called the Battle of Arbela ( grc, Ἄρβηλα, translit=Árbela), took place in 331 BC between the forces of the Army of Macedon under Alexander the Great a ...

. The last known appearance of Gandhara in name as an Achaemenid province is on the list of the tomb of Artaxerxes II

Arses ( grc-gre, Ἄρσης; 445 – 359/8 BC), known by his regnal name Artaxerxes II ( peo, 𐎠𐎼𐎫𐎧𐏁𐏂 ; grc-gre, Ἀρταξέρξης), was King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 405/4 BC to 358 BC. He was the son and suc ...

, circa 358 BCE, date of his burial.Ctesias of Cnidus

Ctesias (; grc-gre, Κτησίας; fl. fifth century BC), also known as Ctesias of Cnidus, was a Greek physician and historian from the town of Cnidus in Caria, then part of the Achaemenid Empire.

Historical events

Ctesias, who lived in the fi ...

related that the Persian king was receiving numerous gifts from the kings of "India" (''Hindūš'').mahouts

A mahout is an elephant rider, trainer, or keeper. Mahouts were used since antiquity for both civilian and military use. Traditionally, mahouts came from ethnic groups with generations of elephant keeping experience, with a mahout retaining h ...

making demonstrations of the elephant's strength at the Achaemenid court.

By about 380 BC, the Persian hold on the region was weakening, but the area continued to be a part of the Achaemenid Empire until Alexander's invasion.

Darius III

Darius III ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; c. 380 – 330 BC) was the last Achaemenid King of Kings of Persia, reigning from 336 BC to his death in 330 BC.

Contrary to his predecessor Artaxerxes IV Arses, Dar ...

(c. 380 – July 330 BC) still had Indian units in his army, albeit very few in comparison to his predecessors.war elephants

A war elephant was an elephant that was trained and guided by humans for combat. The war elephant's main use was to charge the enemy, break their ranks and instill terror and fear. Elephantry is a term for specific military units using elephant ...

at the Battle of Gaugamela

The Battle of Gaugamela (; grc, Γαυγάμηλα, translit=Gaugámela), also called the Battle of Arbela ( grc, Ἄρβηλα, translit=Árbela), took place in 331 BC between the forces of the Army of Macedon under Alexander the Great a ...

for his fight against Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

.Darius I

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his ...

(c.500 BCE)

File:Indian warriors (Sattagydian, Gandharan, Hindush) circa 480 BCE in the Naqsh-e Roastam reliefs of Xerxes I.jpg, Indian soldiers on the tomb of Xerxes I

Xerxes I ( peo, 𐎧𐏁𐎹𐎠𐎼𐏁𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ξέρξης ; – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, ruling from 486 to 465 BC. He was the son and successor of ...

(c.480 BCE)

File:Tomb of Artaxerxes I ethnicities Indians.jpg, Indian soldiers on the tomb of Artaxerxes I

Artaxerxes I (, peo, 𐎠𐎼𐎫𐎧𐏁𐏂𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ἀρταξέρξης) was the fifth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, from 465 to December 424 BC. He was the third son of Xerxes I.

He may have been the " Artasy ...

(c.430 BCE)

File:Tomb of Darius II Indians.jpg, Indian soldiers on the tomb of Darius II

Darius II ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ), also known by his given name Ochus ( ), was King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 423 BC to 405 or 404 BC.

Artaxerxes I, who died in 424 BC, was followed by h ...

(c.410 BCE)

File:Persepolis Tomb of Artaxerxes II Mnemon (r.404-358 BCE) Upper Relief Indian soldiers with labels.jpg, Indian soldiers on the tomb of Artaxerxes II

Arses ( grc-gre, Ἄρσης; 445 – 359/8 BC), known by his regnal name Artaxerxes II ( peo, 𐎠𐎼𐎫𐎧𐏁𐏂 ; grc-gre, Ἀρταξέρξης), was King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 405/4 BC to 358 BC. He was the son and suc ...

(c.370 BCE)

File:Artaxerxes III Indian soldiers.jpg, Indian soldiers on the tomb of Artaxerxes III

Ochus ( grc-gre, Ὦχος ), known by his dynastic name Artaxerxes III ( peo, 𐎠𐎼𐎫𐎧𐏁𐏂𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ἀρταξέρξης), was King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 359/58 to 338 BC. He was the son and successor of A ...

(c.340 BCE)

Indian tributes

Apadana Palace

The reliefs at the

The reliefs at the Apadana Palace

, native_name_lang =

, alternate_name =

, image = Gate of All Nations, Persepolis.jpg

, image_size =

, alt =

, caption = Ruins of the Gate of All Nations, Persepolis.

, map =

, map_type ...

in Persepolis

, native_name_lang =

, alternate_name =

, image = Gate of All Nations, Persepolis.jpg

, image_size =

, alt =

, caption = Ruins of the Gate of All Nations, Persepolis.

, map =

, map_type ...

describe tribute bearers from 23 satrapies visiting the Achaemenid court. These are located at the southern end of the Apadana Staircase. Among the foreigners the Arabs, the Thracians, the Bactrians, the Indians (from the Indus valley area), the Parthians, the Cappadocians, the Elamites or the Medians. The Indians from the Indus valley are bare-chested, except for their leader, and barefooted and wear the dhoti

The dhoti, also known as veshti, vetti, dhuti, mardani, chaadra, dhotar, jaiñboh, panchey, is a type of sarong, tied in a manner that outwardly resembles "loose trousers". It is a lower garment forming part of the ethnic costume for men in the I ...

. They bring baskets with vases inside, carry axes, and drive along a donkey. One man in the Indian procession carries a small but visibly heavy load of four jars on a yoke

A yoke is a wooden beam sometimes used between a pair of oxen or other animals to enable them to pull together on a load when working in pairs, as oxen usually do; some yokes are fitted to individual animals. There are several types of yoke, us ...

, suggesting that he was carrying some of the gold dust paid by the Indians as tribute to the Achaemenid court.["Furthermore the second member of Delegation XVIII is carrying four small but evidently heavy jars on a yoke, probably containing the gold dust which was the tribute paid by the Indians." in ]

According to the Naqsh-e Rustam inscription of Darius I

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his ...

(circa 490 BCE), there were three Achaemenid Satrapies in the subcontinent: Sattagydia, Gandara, Hidūš.

Tribute payments

The conquered area was the most fertile and populous region of the Achaemenid Empire. An amount of tribute was fixed according to the richness of each territory.

The conquered area was the most fertile and populous region of the Achaemenid Empire. An amount of tribute was fixed according to the richness of each territory.Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known f ...

(who makes several comments on India) published a list of tribute-paying nations, classifying them in 20 Provinces. The Province of ''Indos'' ( Ἰνδός, the Indus valley

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

) formed the 20th Province, and was the richest and most populous of the Achaemenid Provinces.

According to Herodotus, the "Indians" ('Ινδοι, ''Indoi'')), as separate from the Gandarei and the Sattagydians, formed the 20th taxation Province, and were required to supply gold dust in tribute to the Achaemenid central government for an amount of 360 Euboean talents (equivalent to about 8300 kg or 8.3 tons of gold annually, a volume of gold that would fit in a cube of side 75 cm). The territories of Gandara,

The territories of Gandara, Sattagydia

Sattagydia (Old Persian: 𐎰𐎫𐎦𐎢𐏁 ''Thataguš'', country of the "hundred cows") was one of the easternmost regions of the Achaemenid Empire, part of its Seventh tax district according to Herodotus, along with Gandārae, Dadicae and ...

, Dadicae (north-west of the Kashmir Valley

The Kashmir Valley, also known as the ''Vale of Kashmir'', is an intermontane valley concentrated in the Kashmir Division of the Indian- union territory of Jammu and Kashmir. The valley is bounded on the southwest by the Pir Panjal Range and ...

) and the Aparytae (Afridi

The Afrīdī ( ps, اپريدی ''Aprīdai'', plur. ''Aprīdī''; ur, آفریدی) are a Pashtun tribe present in Pakistan, with substantial numbers in Afghanistan. The Afridis are most dominant in Pakistan's Federally Administered Tribal ...

s) are named separately, and were aggregated together for taxation purposes, forming the 7th Achaemenid Province, and paying overall a much lower tribute of 170 talents together (about 5151 kg, or 5.1 tons of silver), hence only about 1.5% of the total revenues of the Achaemenid Empire:[ as well as war elephants such as those used at ]Gaugamela

The Battle of Gaugamela (; grc, Γαυγάμηλα, translit=Gaugámela), also called the Battle of Arbela ( grc, Ἄρβηλα, translit=Árbela), took place in 331 BC between the forces of the Army of Macedon under Alexander the Great a ...

.[ The Susa inscriptions of Darius explain that Indian ivory and teak were sold on Persian markets, and used in the construction of his palace.

]

Contribution to Achaemenid war efforts

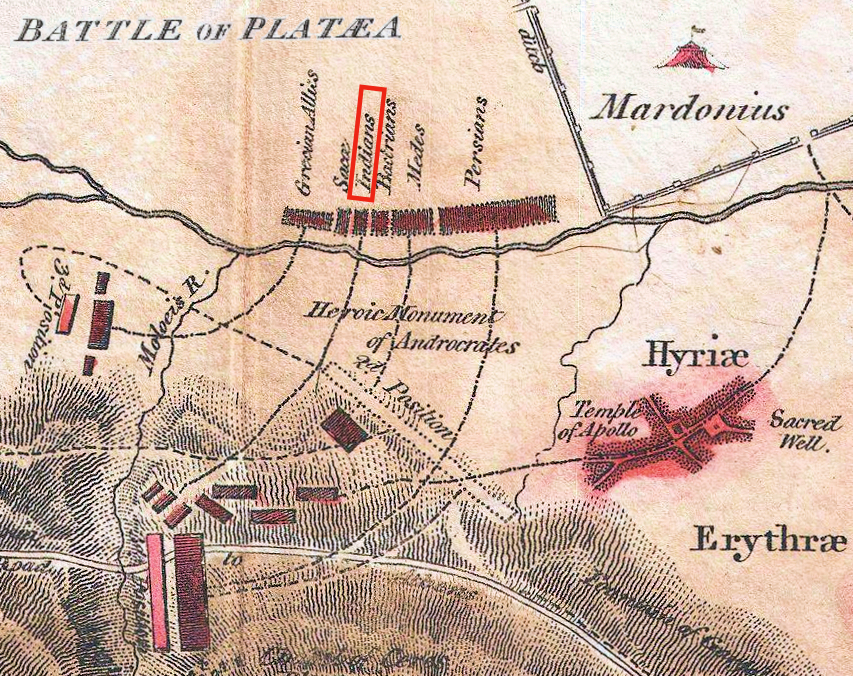

;Second Persian invasion of Greece (480-479 BCE)

Indians were employed in the Achaemenid army of Xerxes in the Second Persian invasion of Greece

The second Persian invasion of Greece (480–479 BC) occurred during the Greco-Persian Wars, as King Xerxes I of Persia sought to conquer all of Greece. The invasion was a direct, if delayed, response to the defeat of the first Persian invasion ...

(480-479 BCE). All troops were stationned in Sardis

Sardis () or Sardes (; Lydian: 𐤳𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣 ''Sfard''; el, Σάρδεις ''Sardeis''; peo, Sparda; hbo, ספרד ''Sfarad'') was an ancient city at the location of modern ''Sart'' (Sartmahmut before 19 October 2005), near Salihli, ...

, Lydia

Lydia (Lydian language, Lydian: 𐤮𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣𐤠, ''Śfarda''; Aramaic: ''Lydia''; el, Λυδία, ''Lȳdíā''; tr, Lidya) was an Iron Age Monarchy, kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient Ionia in the mod ...

, during the winter of 481-480 BCE to prepare for the invasion. In the spring of 480 BCE "Indian troops marched with Xerxes's army across the Hellespont

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

".Battle of Thermopylae

The Battle of Thermopylae ( ; grc, Μάχη τῶν Θερμοπυλῶν, label=Greek, ) was fought in 480 BC between the Achaemenid Persian Empire under Xerxes I and an alliance of Greek city-states led by Sparta under Leonidas I. Lasting o ...

in 480 BCE, and fighting as one of the main nations until the final Battle of Platea

The Battle of Plataea was the final land battle during the second Persian invasion of Greece. It took place in 479 BC near the city of Plataea in Boeotia, and was fought between an alliance of the Greek city-states (including Sparta, Athens, ...

in 479 BCE.["A Sindhu contingent formed a part of his army which invaded Greece and stormed the defile at Thermopylae in 480 BC, thus becoming the first ever force from India to fight on the continent of Europe. It, apparently, distinguished itself in battle because it was followed by another contingent which formed a part of the Persian army under Mardonius which lost the battle of Platea"] Herodotus also explains that the Indian cavalry under the Achaemenids had an equipment similar that of their foot soldiers:

The Gandharis had a different equipment, akin to that of the Bactrians:

;Destruction of Athens and Battle of Plataea (479 BCE)

After the first part of the campaign directly under the orders Xerxes I, the Indian troops are reported to have stayed in Greece as one of the 5 main nations among the 300,000 elite troops of General Mardonius. They fought in the last stages of the war, took part in the Destruction of Athens, but were finally vanquished at the

Herodotus also explains that the Indian cavalry under the Achaemenids had an equipment similar that of their foot soldiers:

The Gandharis had a different equipment, akin to that of the Bactrians:

;Destruction of Athens and Battle of Plataea (479 BCE)

After the first part of the campaign directly under the orders Xerxes I, the Indian troops are reported to have stayed in Greece as one of the 5 main nations among the 300,000 elite troops of General Mardonius. They fought in the last stages of the war, took part in the Destruction of Athens, but were finally vanquished at the Battle of Platea

The Battle of Plataea was the final land battle during the second Persian invasion of Greece. It took place in 479 BC near the city of Plataea in Boeotia, and was fought between an alliance of the Greek city-states (including Sparta, Athens, ...

: At the final

At the final Battle of Platea

The Battle of Plataea was the final land battle during the second Persian invasion of Greece. It took place in 479 BC near the city of Plataea in Boeotia, and was fought between an alliance of the Greek city-states (including Sparta, Athens, ...

in 479 BCE, Indians formed one of the main corps of Achaemenid troops (one of "the greatest of the nations").Bactrians

Bactria (; Bactrian: , ), or Bactriana, was an ancient region in Central Asia in Amu Darya's middle stream, stretching north of the Hindu Kush, west of the Pamirs and south of the Gissar range, covering the northern part of Afghanistan, southwe ...

and the Saka

The Saka ( Old Persian: ; Kharoṣṭhī: ; Ancient Egyptian: , ; , old , mod. , ), Shaka (Sanskrit ( Brāhmī): , , ; Sanskrit (Devanāgarī): , ), or Sacae (Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) were a group of nomadic Iranian peoples who hist ...

e, facing against the enemy Greek troops of "Hermione

Hermione may refer to:

People

* Hermione (given name), a female given name

* Hermione (mythology), only daughter of Menelaus and Helen in Greek mythology and original bearer of the name

Arts and literature

* ''Cadmus et Hermione'', an opera by ...

and Eretria

Eretria (; el, Ερέτρια, , grc, Ἐρέτρια, , literally 'city of the rowers') is a town in Euboea, Greece, facing the coast of Attica across the narrow South Euboean Gulf. It was an important Greek polis in the 6th and 5th centur ...

and Styra

Styra ( grc, τὰ Στύρα) was a town of ancient Euboea, on the west coast, north of Carystus, and nearly opposite the promontory of Cynosura in Attica. The town stood near the shore in the inner part of the bay, in the middle of which is the ...

and Chalcis

Chalcis ( ; Ancient Greek & Katharevousa: , ) or Chalkida, also spelled Halkida (Modern Greek: , ), is the chief town of the island of Euboea or Evia in Greece, situated on the Euripus Strait at its narrowest point. The name is preserved from ...

".Xerxes I

Xerxes I ( peo, 𐎧𐏁𐎹𐎠𐎼𐏁𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ξέρξης ; – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, ruling from 486 to 465 BC. He was the son and successor of ...

, Artaxerxes I

Artaxerxes I (, peo, 𐎠𐎼𐎫𐎧𐏁𐏂𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ἀρταξέρξης) was the fifth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, from 465 to December 424 BC. He was the third son of Xerxes I.

He may have been the " Artasy ...

and Darius II

Darius II ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ), also known by his given name Ochus ( ), was King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 423 BC to 405 or 404 BC.

Artaxerxes I, who died in 424 BC, was followed by h ...

, and at Persepolis

, native_name_lang =

, alternate_name =

, image = Gate of All Nations, Persepolis.jpg

, image_size =

, alt =

, caption = Ruins of the Gate of All Nations, Persepolis.

, map =

, map_type ...

on the tombs of Artaxerxes II

Arses ( grc-gre, Ἄρσης; 445 – 359/8 BC), known by his regnal name Artaxerxes II ( peo, 𐎠𐎼𐎫𐎧𐏁𐏂 ; grc-gre, Ἀρταξέρξης), was King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 405/4 BC to 358 BC. He was the son and suc ...

and Artaxerxes III

Ochus ( grc-gre, Ὦχος ), known by his dynastic name Artaxerxes III ( peo, 𐎠𐎼𐎫𐎧𐏁𐏂𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ἀρταξέρξης), was King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 359/58 to 338 BC. He was the son and successor of A ...

. The last Achaemenid ruler Darius III

Darius III ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; c. 380 – 330 BC) was the last Achaemenid King of Kings of Persia, reigning from 336 BC to his death in 330 BC.

Contrary to his predecessor Artaxerxes IV Arses, Dar ...

never had time to finish his own tomb due to his hasty defeat by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

, and therefore does not have such depictions.Bactria

Bactria (; Bactrian: , ), or Bactriana, was an ancient region in Central Asia in Amu Darya's middle stream, stretching north of the Hindu Kush, west of the Pamirs and south of the Gissar range, covering the northern part of Afghanistan, southwe ...

or Arachosia

Arachosia () is the Hellenized name of an ancient satrapy situated in the eastern parts of the Achaemenid empire. It was centred around the valley of the Arghandab River in modern-day southern Afghanistan, and extended as far east as the In ...

, who are also fully clothed.

The presence of the three ethnicities of Indian soldiers on all the tombs of the Achaemenid rulers after Darius, except for the last ruler

The presence of the three ethnicities of Indian soldiers on all the tombs of the Achaemenid rulers after Darius, except for the last ruler Darius III

Darius III ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; c. 380 – 330 BC) was the last Achaemenid King of Kings of Persia, reigning from 336 BC to his death in 330 BC.

Contrary to his predecessor Artaxerxes IV Arses, Dar ...

who was vanquished by Alexander at Gaugamela

The Battle of Gaugamela (; grc, Γαυγάμηλα, translit=Gaugámela), also called the Battle of Arbela ( grc, Ἄρβηλα, translit=Árbela), took place in 331 BC between the forces of the Army of Macedon under Alexander the Great a ...

, suggests that the Indians were under Achaemenid dominion at least until 338 BCE, the date of the end of the reign of Artaxerxes III

Ochus ( grc-gre, Ὦχος ), known by his dynastic name Artaxerxes III ( peo, 𐎠𐎼𐎫𐎧𐏁𐏂𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ἀρταξέρξης), was King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 359/58 to 338 BC. He was the son and successor of A ...

, before the accession of Darius III, that is, less than 10 years before the campaigns of Alexander in the East and his victory at Gaugamela.

;Indians at the Battle of Gaugamela (331 BCE)

According to Arrian

Arrian of Nicomedia (; Greek: ''Arrianos''; la, Lucius Flavius Arrianus; )

was a Greek historian, public servant, military commander and philosopher of the Roman period.

''The Anabasis of Alexander'' by Arrian is considered the best ...

, Indian troops were still deployed under Darius III at the Battle of Gaugamela

The Battle of Gaugamela (; grc, Γαυγάμηλα, translit=Gaugámela), also called the Battle of Arbela ( grc, Ἄρβηλα, translit=Árbela), took place in 331 BC between the forces of the Army of Macedon under Alexander the Great a ...

(331 BCE). He explains that Darius III "obtained the help of those Indians who bordered on the Bactrians, together with the Bactrians and Sogdianians themselves, all under the command of Bessus, the Satrap of Bactria". The Indians in questions were probably from the area of Gandara. Indian "hill-men" are also said by Arrian to have joined the Arachotians under Satrap Barsentes, and are thought to have been either the Sattagydians or the Hindush.

Fifteen Indian war elephants were also part of the army of Darius III at Gaugamela.[ They had specifically been brought from India. Still, it seems they did not participate to the final battle, probably because of fatigue.]Xerxes I

Xerxes I ( peo, 𐎧𐏁𐎹𐎠𐎼𐏁𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ξέρξης ; – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, ruling from 486 to 465 BC. He was the son and successor of ...

tomb.

Xerxes detail Gandharan head enhanced.jpg, Gandaran soldier (enhanced detail).

Xerxes detail Sattagydian.jpg,

Xerxes detail Sattagydian head enhanced.jpg, Sattagydian soldier (enhanced detail).

Xerxes_Hidush_warrior_480_BCE.jpg, Hindush soldier of the Achaemenid army, circa 480 BCE. Xerxes I

Xerxes I ( peo, 𐎧𐏁𐎹𐎠𐎼𐏁𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ξέρξης ; – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, ruling from 486 to 465 BC. He was the son and successor of ...

tomb.

Xerxes detail Hidush head enhanced.jpg, Hindush soldier (enhanced detail).

Greek and Achaemenid coinage

Coins found in the Chaman Hazouri hoard in

Coins found in the Chaman Hazouri hoard in Kabul

Kabul (; ps, , ; , ) is the capital and largest city of Afghanistan. Located in the eastern half of the country, it is also a municipality, forming part of the Kabul Province; it is administratively divided into 22 municipal districts. Acco ...

, the Shaikhan Dehri hoard in Pushkalavati

Pushkalavati ( ps, پشکلاوتي; Urdu: ; Sanskrit: ; Prākrit: ; grc, Πευκελαῶτις ) or Pushkaravati (Sanskrit: ; Pāli: ), and later Shaikhan Dheri ( ps, شېخان ډېرۍ; ur, ), was the capital of the Gandhara kingdom, ...

in Gandhara, near Charsadda

Chārsadda ( ps, چارسده; ; ur, ; ) is a town and headquarters of Charsadda District, in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan. , as well as in the Bhir Mound

The Bhir Mound ( ur, ) is an archaeological site in Taxila in the Punjab province of Pakistan. It contains some of the oldest ruins of Ancient Taxila, dated to sometime around the period 800-525 BC as its earliest layers bear "grooved" Red B ...

hoard in Taxila, have revealed numerous Achaemenid coins as well as many Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

coins from the 5th and 4th centuries BCE. These circulated in the area, at least as far as the Indus

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

during the reign of the Achaemenids, who were in control of the areas as far as Gandhara.[

]

Kabul and Bhir Mound hoards

The Kabul hoard

The Kabul hoard, also called the Chaman Hazouri, Chaman Hazouri or Tchamani-i Hazouri hoard, is a coin hoard discovered in the vicinity of Kabul, Afghanistan in 1933. The collection contained numerous Achaemenid coins as well as many Ancient Greec ...

, also called the Chaman Hazouri, Chaman Hazouri or Tchamani-i Hazouri hoard, is a coin hoard discovered in the vicinity of Kabul

Kabul (; ps, , ; , ) is the capital and largest city of Afghanistan. Located in the eastern half of the country, it is also a municipality, forming part of the Kabul Province; it is administratively divided into 22 municipal districts. Acco ...

, Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

. The hoard, discovered in 1933, contained numerous Achaemenid coins as well as many Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

coins from the 5th and 4th centuries BCE.[ Approximately one thousand coins were in the hoard.]coinage of India

The Coinage of India began anywhere between early 1st millennium BCE to the 6th century BCE, and consisted mainly of copper and silver coins in its initial stage.Allan & Stern (2008) The coins of this period were ''Karshapanas'' or ''Pana''. A ...

, since it is one of the very rare instances when punch-marked coins can actually be dated, due to their association with known and dated Greek and Achaemenid coins in the hoard. The hoard supports the view that punch-marked coins existed in 360 BCE, as suggested by literary evidence.

Daniel Schlumberger

Daniel Théodore Schlumberger (19 December 1904 – 21 October 1972) was a French archaeologist and Professor of Near Eastern Archaeology at the University of Strasbourg and later Princeton University.

Biography

After having been invited by ...

also considers that punch-marked bars, similar to the many punch-marked bars found in north-western India, initially originated in the Achaemenid Empire, rather than in the Indian heartland:

Modern numismatists now tend to consider the Achaemenid punch-marked coins as the precursors of the Indian punch-marked coins

Punch-marked coins, also known as ''Aahat coins'', are a type of early coinage of India, dating to between about the 6th and 2nd centuries BC. It was of irregular shape.

History

The study of the relative chronology of these coins has successful ...

.

Pushkalavati hoard

In 2007, a small coin hoard was discovered at the site of ancient Pushkalavati

Pushkalavati ( ps, پشکلاوتي; Urdu: ; Sanskrit: ; Prākrit: ; grc, Πευκελαῶτις ) or Pushkaravati (Sanskrit: ; Pāli: ), and later Shaikhan Dheri ( ps, شېخان ډېرۍ; ur, ), was the capital of the Gandhara kingdom, ...

(the Shaikhan Dehri hoard) near Charsada

Chārsadda ( ps, چارسده; ; ur, ; ) is a town and headquarters of Charsadda District, in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan. in Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

. The hoard contained a tetradrachm

The tetradrachm ( grc-gre, τετράδραχμον, tetrádrachmon) was a large silver coin that originated in Ancient Greece. It was nominally equivalent to four Greek drachma, drachmae. Over time the tetradrachm effectively became the standard ...

minted in Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

circa 500/490-485/0 BCE, typically used as a currency for trade in the Achaemenid Empire, together with a number of local types as well as silver cast ingots. The Athens coin is the earliest known example of its type to be found so far to the east.

According to Joe Cribb

Joe Cribb is a numismatist, specialising in Asian coinages, and in particular on coins of the Kushan Empire. His catalogues of Chinese silver currency ingots, and of ritual coins of Southeast Asia were the first detailed works on these subjects i ...

, these early Greek coins were at the origin of Indian punch-marked coins

Punch-marked coins, also known as ''Aahat coins'', are a type of early coinage of India, dating to between about the 6th and 2nd centuries BC. It was of irregular shape.

History

The study of the relative chronology of these coins has successful ...

, the earliest coins developed in India, which used minting technology derived from Greek coinage.

Influence of Achaemenid culture in the Indian subcontinent

Cultural exchanges: Taxila

Taxila

Taxila or Takshashila (; sa, तक्षशिला; pi, ; , ; , ) is a city in Punjab, Pakistan. Located in the Taxila Tehsil of Rawalpindi District, it lies approximately northwest of the Islamabad–Rawalpindi metropolitan area and ...

(site of Bhir Mound

The Bhir Mound ( ur, ) is an archaeological site in Taxila in the Punjab province of Pakistan. It contains some of the oldest ruins of Ancient Taxila, dated to sometime around the period 800-525 BC as its earliest layers bear "grooved" Red B ...

), the "most plausible candidate for the capital of Achaemenid India",Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

(XV, 1, 62), when Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

was in Taxila, one of his companions named Aristobulus Aristobulus or Aristoboulos may refer to:

*Aristobulus I (died 103 BC), king of the Hebrew Hasmonean Dynasty, 104–103 BC

*Aristobulus II (died 49 BC), king of Judea from the Hasmonean Dynasty, 67–63 BC

*Aristobulus III of Judea (53 BC–36 BC), ...

, noticed that in the city the dead were being fed to the vultures, a clear allusion to the presence of Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism is an Iranian religions, Iranian religion and one of the world's History of religion, oldest organized faiths, based on the teachings of the Iranian peoples, Iranian-speaking prophet Zoroaster. It has a Dualism in cosmology, du ...

. The renowned University of Taxila became the greatest learning centre in the region, and allowed for exchanges between people from various cultures.

;Followers of the Buddha

Several contemporaries, and close followers, of the Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a śramaṇa, wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was ...

are said to have studied in Achaemenid Taxila: King Pasenadi

Pasenadi ( pi, पसेनदि ; sa, प्रसेनजित् ; c. 6th century BCE) was an ruler of Kosala. Sāvatthī was his capital. He succeeded after . He was a prominent (lay follower) of Gautama Buddha, and built many Budd ...

of Kosala

The Kingdom of Kosala (Sanskrit: ) was an ancient Indian kingdom with a rich culture, corresponding to the area within the region of Awadh in present-day Uttar Pradesh to Western Odisha. It emerged as a janapada, small state during the late Ve ...

, a close friend of the Buddha, Bandhula, the commander of Pasedani's army, Aṅgulimāla

Aṅgulimāla ( Pāli language; lit. 'finger necklace') is an important figure in Buddhism, particularly within the Theravāda tradition. Depicted as a ruthless brigand who completely transforms after a conversion to Buddhism, he is seen as the ...

, a close follower of the Buddha, and Jivaka, court doctor at Rajagriha

Rajgir, meaning "The City of Kings," is a historic town in the district of Nalanda in Bihar, India. As the ancient seat and capital of the Haryanka dynasty, the Pradyota dynasty, the Brihadratha dynasty and the Mauryan Empire, as well as the d ...

and personal doctor of the Buddha. According to Stephen Batchelor Stephen Batchelor may refer to:

* Stephen Batchelor (author) (born 1953), Scottish-born author of books relating to Buddhism

*Stephen Batchelor (field hockey)

Stephen James "Steve" Batchelor (born 22 June 1961) is an English former field hockey ...

, the Buddha may have been influenced by the experiences and knowledge acquired by some of his closest followers in Taxila.

;Pāṇini

The 5th century BCE grammarian Pāṇini

, era = ;;6th–5th century BCE

, region = Indian philosophy

, main_interests = Grammar, linguistics

, notable_works = ' (Sanskrit#Classical Sanskrit, Classical Sanskrit)

, influenced=

, notable_ideas=Descript ...

lived in an Achaemenid environment.Shalatula

Śalātura was the birthplace of ancient South Asian Sanskrit grammarian Pāṇini who is considered to the oldest grammarian whose work has come down to modern times. In an inscription of Siladitya VII of Valabhi, he is called ''Śalāturiya'' ...

near Attock

Attock ( Punjabi and Urdu: ), formerly known as Campbellpur (), is a historical city located in the north of Pakistan's Punjab Province, not far from the country's capital Islamabad. It is the headquarters of the Attock District and is 61st larg ...

to the north-west of Taxila, in what was then a satrapy

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median and Achaemenid Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic empires.

The satrap served as viceroy to the king, though with consid ...

of the Achaemenid Empire following the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley, which technically made him a Persian subject.Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

met with the young Chandragupta while campaigning in the Punjab

Punjab (; Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising ...

.[

; : "The Mudrarakshasa further informs us that his Himalayan alliance gave Chandragupta a composite army ... Among these are mentioned the following : Sakas, Yavanas (probably Greeks), Kiratas, Kambojas, Parasikas and Bahlikas."

][

: "Among those who helped Chandragupta in his struggle against the Nandas, were the Sakas (Scythians), Yavanas (Greeks), and Parasikas (Persians)"

][

: "After Alexander's death, when Chandragupta marched on Magadha, Magada, it was with largely the Persian army that he won the throne of India. The testimony of the Mudrarakshasa is explicit on this point, and we have no reason to doubt its accuracy in matter[s] of this kind."

] The ''Sakas'' were Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an Ancient Iranian peoples, ancient Eastern Iranian languages, Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved f ...

, the ''Yavanas'' were Greeks, and the ''Parasikas'' were Persians.

Scientific knowledge

Astronomical and astrological knowledge was also probably transmitted to India from Babylon during the 5th century BCE as a consequence of the Achaemenid presence in the sub-continent. Babylonian astronomy was the first form of astronomy to fully develop and likely influenced other civilizations. The spread of knowledge may have hastened with the expansion of the Achaemenid Empire.

According to David Pingree, elements of Achaemenid scientific knowledge, particularly works on omens and astronomy, were adopted by India from the 5th century BCE:

Palatial art and architecture: Pataliputra

Various Indian artefacts tend to suggest some Perso-Hellenistic artistic influence in India, mainly felt during the time of the Mauryan Empire. The sculpture of the Masarh lion, found near the Maurya capital of Pataliputra, raises the question of the Achaemenid and Greek influence on the art of the Mauryan art, Maurya Empire, and on the western origins of stone carving in India. The lion is carved in Chunar stone, Chunar sandstone, like the Pillars of Ashoka, and its finish is polished, a feature of the Mauryan art, Maurya sculpture.

Various Indian artefacts tend to suggest some Perso-Hellenistic artistic influence in India, mainly felt during the time of the Mauryan Empire. The sculpture of the Masarh lion, found near the Maurya capital of Pataliputra, raises the question of the Achaemenid and Greek influence on the art of the Mauryan art, Maurya Empire, and on the western origins of stone carving in India. The lion is carved in Chunar stone, Chunar sandstone, like the Pillars of Ashoka, and its finish is polished, a feature of the Mauryan art, Maurya sculpture.Persepolis

, native_name_lang =

, alternate_name =

, image = Gate of All Nations, Persepolis.jpg

, image_size =

, alt =

, caption = Ruins of the Gate of All Nations, Persepolis.

, map =

, map_type ...

.[Page 88: "There is one fragmentary lion head from Masarh, Distt. Bhojpur, Bihar. It is carved out of Chunar sandstone and it also bears the typical Mauryan polish. But it is undoubtedly based on the Achaemenian idiom. The tubular or wick-like whiskers and highly decorated neck with long locks of the mane with one series arranged like sea waves is somewhat non-Indian in approach . But, to be exact, we have an example of a lion from a sculptural frieze from Persepolis of 5th century BCE in which it is overpowering a bull which may be compared with the Masarh lion."... Page 122: "This particular example of a foreign model gets added support from the male heads of foreigners from Patna city and Sarnath since they also prove beyond doubt that a section of the elite in the Gangetic Basin was of foreign origin. However, as noted earlier, this is an example of the late Mauryan period since this is not the type adopted in any Ashoka pillar. We are, therefore, visualizing a historical situation in India in which the West Asian influence on Indian art was felt more in the late Mauryan than in the early Mauryan period. The term West Asia in this context stands for Iran and Afghanistan, where the Sakas and Pahlavas had their basecamps for eastward movement. The prelude to future inroads of the Indo-Bactrians in India had after all started in the second century B.C."... in . Also ]

The Pataliputra palace with its pillared hall shows decorative influences of the Achaemenid palaces and Persepolis and may have used the help of foreign craftsmen. Mauryan rulers may have even imported craftsmen from abroad to build royal monuments. This may be the result of the formative influence of craftsmen employed from Persia following the disintegration of the Achaemenid Empire after the conquests of Alexander the Great.["The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c.6500 BCE-200 CE" Robin Coningham, Ruth Young Cambridge University Press, 31 aout 2015, p.41]

/ref> The Pataliputra capital, or also the Hellenistic friezes of the Rampurva capitals, Sankissa, and the Vajrasana, Bodh Gaya, diamond throne of Bodh Gaya are other examples.

The renowned Mauryan polish, especially used in the Pillars of Ashoka, may also have been a technique imported from the Achaemenid Empire.

File:Mauryan ruins of pillared hall at Kumrahar site of Pataliputra ASIEC 1912-13.jpg, Ruins of pillared hall at Kumrahar site at Pataliputra.

File:Kumhrar Maurya level ASIEC 1912-1913.jpg, Plan of the 80-column pillared hall in Pataliputra.

File:Pataliputra_capital,_Bihar_Museum,_Patna,_3rd_century_BCE.jpg, The Pataliputra capital, generally described as "Perso-Hellenistic".

File:Patna griffin.jpg, Griffin of Pataliputra.

File:Pataliputra lotus motif.jpg, Lotus motifs in Pataliputra.

Rock-cut architecture

The similarity of the 4th century BCE Lycian barrel-vaulted tombs, such as the tomb of Payava, in the western part of the Achaemenid Empire, with the Indian architectural design of the Chaitya (starting at least a century later from circa 250 BCE, with the Lomas Rishi caves in the Barabar caves, Barabar caves group), suggests that the designs of the Lycian rock-cut tombs travelled to India along the trade routes across the Achaemenid Empire.Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

.

Monumental columns: the Pillars of Ashoka

Regarding the Pillars of Ashoka, there has been much discussion of the extent of influence from Achaemenid Persia, since the column capitals supporting the roofs at Persepolis

, native_name_lang =

, alternate_name =

, image = Gate of All Nations, Persepolis.jpg

, image_size =

, alt =

, caption = Ruins of the Gate of All Nations, Persepolis.

, map =

, map_type ...

have similarities, and the "rather cold, hieratic style" of the Sarnath Lion Capital of Ashoka especially shows "obvious Achaemenid and Sargon II, Sargonid influence".

Hellenistic influence on Indian art, Hellenistic influence has also been suggested. In particular the abacus (architecture), abaci of some of the pillars (especially the Rampurva, Rampurva bull, the Sankissa, Sankissa elephant and the Allahabad pillar, Allahabad pillar capital) use bands of motifs, like the bead and reel pattern, the ovolo, the flame palmettes, Lotus flower, lotuses, which likely originated from Greek and Near-Eastern arts.[Buddhist Architecture, by Huu Phuoc Le, Grafikol, 201]

p.44

/ref> Such examples can also be seen in the remains of the Mauryan capital city of Pataliputra.

File:Rampurva_bull_capital_detail.jpg, Frieze of Rampurva capitals, alternating palmettes and Nelumbo nucifera, lotus .

File:Sankissa_elephant_abacus_detail.jpg, Frieze of Sankissa.

File:Diamond_Throne_Vajrasana_front_frieze.jpg, Frieze of the Vajrasana, Bodh Gaya, diamond throne of Bodh Gaya.

Aramaic language and script

The Aramaic language, official language of the Achaemenid Empire, started to be used in the Indian territories.

The Aramaic language, official language of the Achaemenid Empire, started to be used in the Indian territories.Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

and Afghanistan