Academic Art on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Academic art, or academicism or academism, is a style of painting and sculpture produced under the influence of European

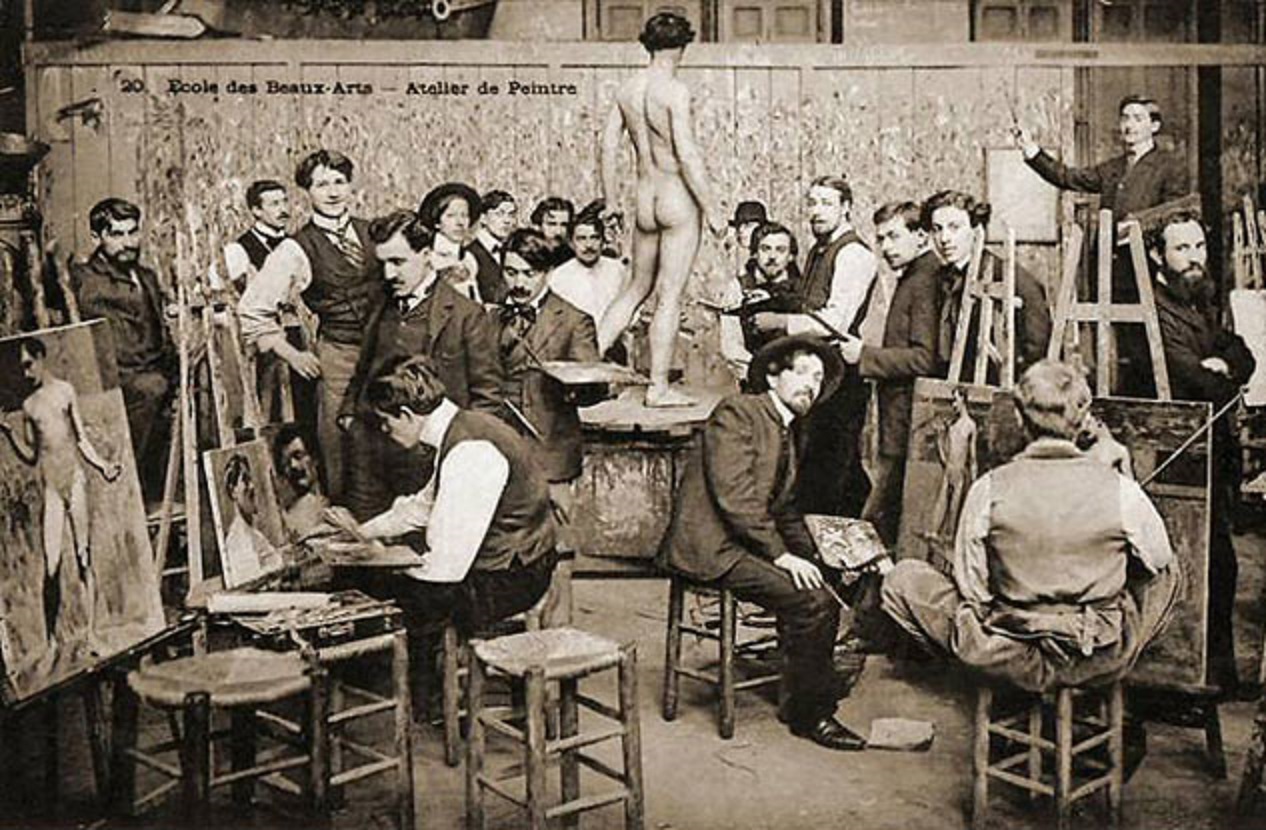

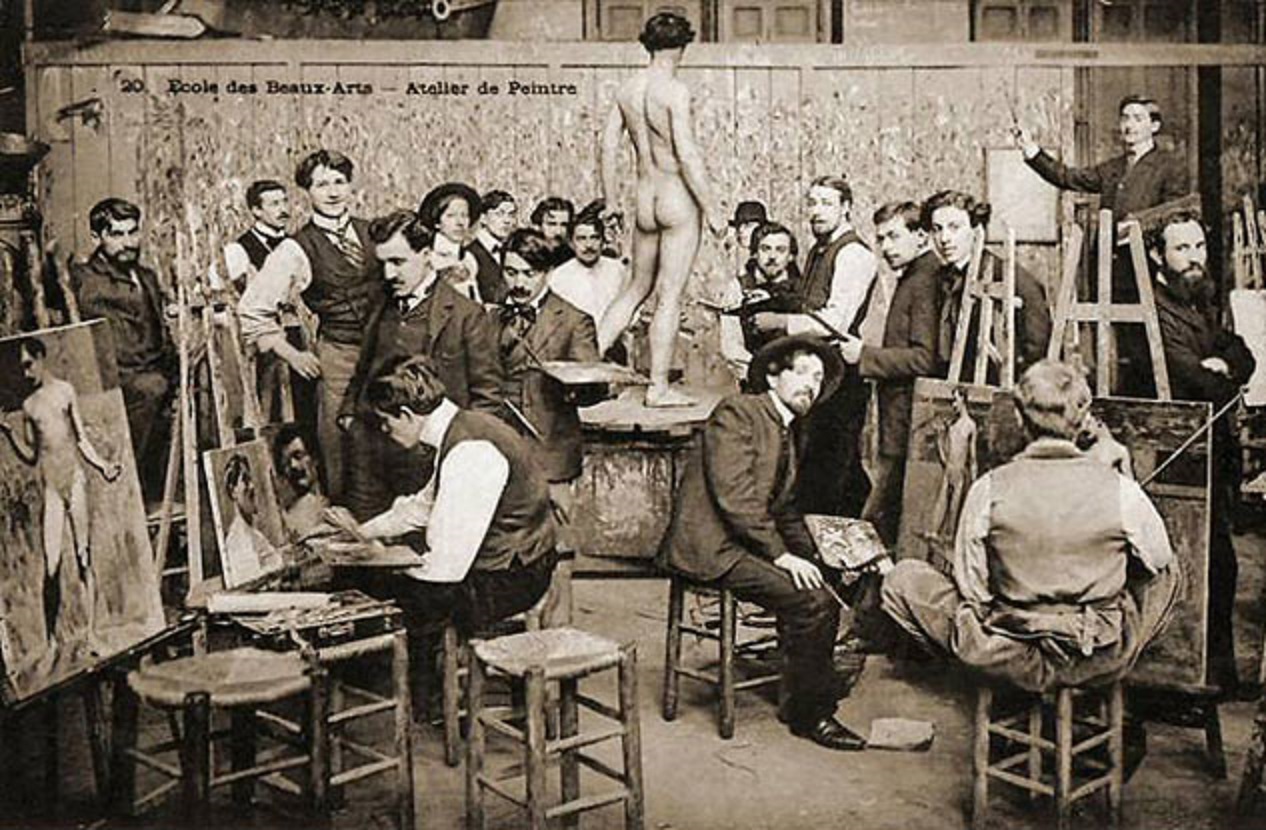

Young artists spent four years in rigorous training. In France, only students who passed an exam and carried a letter of reference from a noted professor of art were accepted at the academy's school, the École des Beaux-Arts. Drawings and paintings of the nude, called "académies," were the basic building blocks of academic art and the procedure for learning to make them was clearly defined. First, students copied prints after classical sculptures, becoming familiar with the principles of contour, light, and shade. The copy was believed crucial to the academic education; from copying works of past artists one would assimilate their methods of art making. To advance to the next step, and every successive one, students presented drawings for evaluation.

Young artists spent four years in rigorous training. In France, only students who passed an exam and carried a letter of reference from a noted professor of art were accepted at the academy's school, the École des Beaux-Arts. Drawings and paintings of the nude, called "académies," were the basic building blocks of academic art and the procedure for learning to make them was clearly defined. First, students copied prints after classical sculptures, becoming familiar with the principles of contour, light, and shade. The copy was believed crucial to the academic education; from copying works of past artists one would assimilate their methods of art making. To advance to the next step, and every successive one, students presented drawings for evaluation.

If approved, they would then draw from plaster casts of famous classical sculptures. Only after acquiring these skills were artists permitted entrance to classes in which a live model posed. Painting was not taught at the École des Beaux-Arts until after 1863. To learn to paint with a brush, the student first had to demonstrate proficiency in drawing, which was considered the foundation of academic painting. Only then could the pupil join the studio of an academician and learn how to paint. Throughout the entire process, competitions with a predetermined subject and a specific allotted period of time measured each student's progress.

The most famous art competition for students was the Prix de Rome. The winner of the Prix de Rome was awarded a fellowship to study at the Académie française's school at the Villa Medici in Rome for up to five years. To compete, an artist had to be of French nationality, male, under 30 years of age, and single. He had to have met the entrance requirements of the École and have the support of a well-known art teacher. The competition was grueling, involving several stages before the final one, in which 10 competitors were sequestered in studios for 72 days to paint their final history paintings. The winner was essentially assured a successful professional career.

As noted, a successful showing at the Salon was a seal of approval for an artist. Artists petitioned the hanging committee for optimal placement "on the line," or at eye level. After the exhibition opened, artists complained if their works were "skyed," or hung too high. The ultimate achievement for the professional artist was election to membership in the Académie française and the right to be known as an academician.

If approved, they would then draw from plaster casts of famous classical sculptures. Only after acquiring these skills were artists permitted entrance to classes in which a live model posed. Painting was not taught at the École des Beaux-Arts until after 1863. To learn to paint with a brush, the student first had to demonstrate proficiency in drawing, which was considered the foundation of academic painting. Only then could the pupil join the studio of an academician and learn how to paint. Throughout the entire process, competitions with a predetermined subject and a specific allotted period of time measured each student's progress.

The most famous art competition for students was the Prix de Rome. The winner of the Prix de Rome was awarded a fellowship to study at the Académie française's school at the Villa Medici in Rome for up to five years. To compete, an artist had to be of French nationality, male, under 30 years of age, and single. He had to have met the entrance requirements of the École and have the support of a well-known art teacher. The competition was grueling, involving several stages before the final one, in which 10 competitors were sequestered in studios for 72 days to paint their final history paintings. The winner was essentially assured a successful professional career.

As noted, a successful showing at the Salon was a seal of approval for an artist. Artists petitioned the hanging committee for optimal placement "on the line," or at eye level. After the exhibition opened, artists complained if their works were "skyed," or hung too high. The ultimate achievement for the professional artist was election to membership in the Académie française and the right to be known as an academician.

Academic art was first criticized for its use of idealism, by Realist artists such as Gustave Courbet, as being based on idealistic clichés and representing mythical and legendary motives while contemporary social concerns were being ignored. Another criticism by Realists was the " false surface" of paintings—the objects depicted looked smooth, slick, and idealized—showing no real texture. The Realist

Academic art was first criticized for its use of idealism, by Realist artists such as Gustave Courbet, as being based on idealistic clichés and representing mythical and legendary motives while contemporary social concerns were being ignored. Another criticism by Realists was the " false surface" of paintings—the objects depicted looked smooth, slick, and idealized—showing no real texture. The Realist

"From 'Riches to Rags to Riches'"

''ArtNews''. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

academies of art

The following is a list of notable art schools.

Accredited non-profit art and design colleges

* Adelaide Central School of Art

* Alberta College of Art and Design

* Art Academy of Cincinnati

* Art Center College of Design

* The Art Institut ...

. Specifically, academic art is the art and artists influenced by the standards of the French Académie des Beaux-Arts, which was practiced under the movements of Neoclassicism

Neoclassicism (also spelled Neo-classicism) was a Western cultural movement in the decorative and visual arts, literature, theatre, music, and architecture that drew inspiration from the art and culture of classical antiquity. Neoclassicism was ...

and Romanticism, and the art that followed these two movements in the attempt to synthesize both of their styles, and which is best reflected by the paintings of William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Thomas Couture, and Hans Makart. In this context it is often called "academism," "academicism," " art pompier" (pejoratively), and "eclecticism," and sometimes linked with " historicism" and "syncretism

Syncretism () is the practice of combining different beliefs and various school of thought, schools of thought. Syncretism involves the merging or religious assimilation, assimilation of several originally discrete traditions, especially in t ...

." Academic art is closely related to Beaux-Arts architecture, which developed in the same place and holds to a similar classicizing ideal.

The academies in history

The first academy of art was founded in Florence in Italy by Cosimo I de' Medici, on 13 January 1563, under the influence of the architect Giorgio Vasari who called it the ''Accademia e Compagnia delle Arti del Disegno'' (Academy and Company for the Arts of Drawing) as it was divided in two different operative branches. While the Company was a kind of corporation which every working artist in Tuscany could join, the Academy comprised only the most eminent artistic personalities of Cosimo's court, and had the task of supervising the whole artistic production of the Medicean state. In this Medicean institution students learned the "arti del disegno" (a term coined by Vasari) and heard lectures on anatomy and geometry. Another academy, the Accademia di San Luca (named after the patron saint of painters,St. Luke

Luke the Evangelist (Latin: '' Lucas''; grc, Λουκᾶς, '' Loukâs''; he, לוקאס, ''Lūqās''; arc, /ܠܘܩܐ לוקא, ''Lūqā’; Ge'ez: ሉቃስ'') is one of the Four Evangelists—the four traditionally ascribed authors of t ...

), was founded about a decade later in Rome. The Accademia di San Luca served an educational function and was more concerned with art theory than the Florentine one. In 1582 Annibale Carracci

Annibale Carracci (; November 3, 1560 – July 15, 1609) was an Italian painter and instructor, active in Bologna and later in Rome. Along with his brother and cousin, Annibale was one of the progenitors, if not founders of a leading strand of th ...

opened his very influential ''Academy of Desiderosi'' in Bologna without official support; in some ways this was more like a traditional artist's workshop, but that he felt the need to label it as an "academy" demonstrates the attraction of the idea at the time.

Accademia di San Luca later served as the model for the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture

The Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (; en, "Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture") was founded in 1648 in Paris, France. It was the premier art institution of France during the latter part of the Ancien Régime until it was abol ...

founded in France in 1648, and which later became the Académie des beaux-arts. The Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture was founded in an effort to distinguish artists "who were gentlemen practicing a liberal art" from craftsmen, who were engaged in manual labor. This emphasis on the intellectual component of artmaking had a considerable impact on the subjects and styles of academic art.

After the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture was reorganized in 1661 by Louis XIV whose aim was to control all the artistic activity in France, a controversy occurred among the members that dominated artistic attitudes for the rest of the century. This "battle of styles" was a conflict over whether Peter Paul Rubens or Nicolas Poussin

Nicolas Poussin (, , ; June 1594 – 19 November 1665) was the leading painter of the classical French Baroque style, although he spent most of his working life in Rome. Most of his works were on religious and mythological subjects painted for a ...

was a suitable model to follow. Followers of Poussin, called "poussinistes," argued that line (disegno) should dominate art, because of its appeal to the intellect, while followers of Rubens, called "rubenistes," argued that color (colore) should dominate art, because of its appeal to emotion.

The debate was revived in the early 19th century, under the movements of Neoclassicism

Neoclassicism (also spelled Neo-classicism) was a Western cultural movement in the decorative and visual arts, literature, theatre, music, and architecture that drew inspiration from the art and culture of classical antiquity. Neoclassicism was ...

typified by the artwork of Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres ( , ; 29 August 1780 – 14 January 1867) was a French Neoclassical painter. Ingres was profoundly influenced by past artistic traditions and aspired to become the guardian of academic orthodoxy against the ...

, and Romanticism typified by the artwork of Eugène Delacroix. Debates also occurred over whether it was better to learn art by looking at nature, or to learn by looking at the artistic masters of the past.

Academies using the French model formed throughout Europe, and imitated the teachings and styles of the French Académie. In England, this was the Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly in London. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its pur ...

. The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts founded in 1754, may be taken as a successful example in a smaller country, which achieved its aim of producing a national school and reducing the reliance on imported artists. The painters of the Danish Golden Age of roughly 1800-1850 were nearly all trained there, and many returned to teach and the history of the art of Denmark is much less marked by tension between academic art and other styles than is the case in other countries.

Women artists

One effect of the move to academies was to make training more difficult forwomen artists

The absence of women from the canon of Western culture, Western Art history, art has been a subject of inquiry and reconsideration since the early 1970s. Linda Nochlin's influential 1971 essay, "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?, Why ...

, who were excluded from most academies until the last half of the 19th century (1861 for the Royal Academy). This was partly because of concerns over the perceived impropriety presented by nudity. Special arrangements were sometimes made for female students until the 20th century.

Development of the academic style

Since the onset of the Poussiniste-Rubeniste debate, many artists worked between the two styles. In the 19th century, in the revived form of the debate, the attention and the aims of the art world became to synthesize the line ofNeoclassicism

Neoclassicism (also spelled Neo-classicism) was a Western cultural movement in the decorative and visual arts, literature, theatre, music, and architecture that drew inspiration from the art and culture of classical antiquity. Neoclassicism was ...

with the color of Romanticism. One artist after another was claimed by critics to have achieved the synthesis, among them Théodore Chassériau, Ary Scheffer

Ary Scheffer (10 February 179515 June 1858) was a Dutch-French Romantic painter. He was known mostly for his works based on literature, with paintings based on the works of Dante, Goethe, and Lord Byron, as well as religious subjects. He was als ...

, Francesco Hayez, Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, and Thomas Couture. William-Adolphe Bouguereau, a later academic artist, commented that the trick to being a good painter is seeing "color and line as the same thing."

Thomas Couture promoted the same idea in a book he authored on art method—arguing that whenever one said a painting had better color or better line it was nonsense, because whenever color appeared brilliant it depended on line to convey it, and vice versa; and that color was really a way to talk about the "value" of form.

Another development during this period included adopting historical styles in order to show the era in history that the painting depicted, called historicism. This is best seen in the work of Baron Jan August Hendrik Leys, a later influence on James Tissot. It's also seen in the development of the Neo-Grec style. Historicism is also meant to refer to the belief and practice associated with academic art that one should incorporate and conciliate the innovations of different traditions of art from the past.

The art world also grew to give increasing focus on allegory

As a literary device or artistic form, an allegory is a narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a hidden meaning with moral or political significance. Authors have used allegory th ...

in art. Theories of the importance of both line and color asserted that through these elements an artist exerts control over the medium to create psychological effects, in which themes, emotions, and ideas can be represented. As artists attempted to synthesize these theories in practice, the attention on the artwork as an allegorical or figurative vehicle was emphasized. It was held that the representations in painting and sculpture should evoke Platonic forms, or ideals, where behind ordinary depictions one would glimpse something abstract, some eternal truth. Hence, Keats' famous musing "Beauty is truth, truth beauty." The paintings were desired to be an "idée," a full and complete idea. Bouguereau

William-Adolphe Bouguereau (; 30 November 1825 – 19 August 1905) was a French academic painter. In his realistic genre paintings, he used mythological themes, making modern interpretations of classical subjects, with an emphasis on the female ...

is known to have said that he wouldn't paint "a war," but would paint "War." Many paintings by academic artists are simple nature allegories with titles like ''Dawn'', ''Dusk'', ''Seeing'', and ''Tasting'', where these ideas are personified by a single nude figure, composed in such a way as to bring out the essence of the idea.

The trend in art was also towards greater idealism, which is contrary to realism, in that the figures depicted were made simpler and more abstract—idealized—in order to be able to represent the ideals they stood in for. This would involve both generalizing forms seen in nature, and subordinating them to the unity and theme of the artwork.

Because history and mythology were considered as plays or dialectic

Dialectic ( grc-gre, διαλεκτική, ''dialektikḗ''; related to dialogue; german: Dialektik), also known as the dialectical method, is a discourse between two or more people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing ...

s of ideas, a fertile ground for important allegory, using themes from these subjects was considered the most serious form of painting. A hierarchy of genres, originally created in the 17th century, was valued, where history painting

History painting is a genre in painting defined by its subject matter rather than any artistic style or specific period. History paintings depict a moment in a narrative story, most often (but not exclusively) Greek and Roman mythology and Bible ...

—classical, religious, mythological, literary, and allegorical subjects—was placed at the top, next genre painting

Genre painting (or petit genre), a form of genre art, depicts aspects of everyday life by portraying ordinary people engaged in common activities. One common definition of a genre scene is that it shows figures to whom no identity can be attached ...

, then portraiture, still-life

A still life (plural: still lifes) is a work of art depicting mostly inanimate subject matter, typically commonplace objects which are either natural (food, flowers, dead animals, plants, rocks, shells, etc.) or man-made (drinking glasses, boo ...

, and landscape

A landscape is the visible features of an area of land, its landforms, and how they integrate with natural or man-made features, often considered in terms of their aesthetic appeal.''New Oxford American Dictionary''. A landscape includes the ...

. History painting was also known as the "grande genre." Paintings of Hans Makart are often larger than life historical dramas, and he combined this with a historicism in decoration to dominate the style of 19th century Vienna culture. Paul Delaroche is a typifying example of French history painting.

All of these trends were influenced by the theories of the philosopher Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (; ; 27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a German philosopher. He is one of the most important figures in German idealism and one of the founding figures of modern Western philosophy. His influence extends a ...

, who held that history was a dialectic

Dialectic ( grc-gre, διαλεκτική, ''dialektikḗ''; related to dialogue; german: Dialektik), also known as the dialectical method, is a discourse between two or more people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing ...

of competing ideas, which eventually resolved in synthesis.

Towards the end of the 19th century, academic art had saturated European society. Exhibitions were held often, with the most popular exhibition being the Paris Salon

The Salon (french: Salon), or rarely Paris Salon (French: ''Salon de Paris'' ), beginning in 1667 was the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Between 1748 and 1890 it was arguably the greatest annual or biennial art ...

and beginning in 1903, the Salon d'Automne. These salons were large scale events that attracted crowds of visitors, both native and foreign. As much a social affair as an artistic one, 50,000 people might visit on a single Sunday, and as many as 500,000 could see the exhibition during its two-month run. Thousands of pictures were displayed, hung from just below eye level all the way up to the ceiling in a manner now known as "Salon style." A successful showing at the salon was a seal of approval for an artist, making his work saleable to the growing ranks of private collectors. Bouguereau

William-Adolphe Bouguereau (; 30 November 1825 – 19 August 1905) was a French academic painter. In his realistic genre paintings, he used mythological themes, making modern interpretations of classical subjects, with an emphasis on the female ...

, Alexandre Cabanel and Jean-Léon Gérôme were leading figures of this art world.

During the reign of academic art, the paintings of the Rococo era, previously held in low favor, were revived to popularity, and themes often used in Rococo art such as Eros and Psyche were popular again. The academic art world also admired Raphael, for the ideality of his work, in fact preferring him over Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (; 6 March 1475 – 18 February 1564), known as Michelangelo (), was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was insp ...

.

Academic art in Poland

Art in Poland refers to all forms of visual art in or associated with Poland.

Nineteenth century

Polish art has often reflected European trends while maintaining its unique character.

The Kraków school of history painting developed by Ja ...

flourished under Jan Matejko

Jan Alojzy Matejko (; also known as Jan Mateyko; 24 June 1838 – 1 November 1893) was a Poles, Polish painting, painter, a leading 19th-century exponent of history painting, known for depicting nodal events from Polish history. His works includ ...

, who established the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts

The Jan Matejko Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków ( pl, Akademia Sztuk Pięknych im. Jana Matejki w Krakowie, usually abbreviated to ''ASP''), is a public institution of higher education located in the centre of Kraków, Poland. It is the oldest Pol ...

. Many of these works can be seen in the

Gallery of 19th-Century Polish Art at Sukiennice in Kraków.

Academic art not only held influence in Western Europe and the United States, but also extended its influence to other countries. The artistic environment of Greece, for instance, was dominated by techniques from Western academies from the 17th century onward: this was first evident in the activities of the Ionian School, and later became especially pronounced with the dawn of the Munich School. This was also true for Latin American nations, which, because their revolutions were modeled on the French Revolution, sought to emulate French culture. An example of a Latin American academic artist is Ángel Zárraga of Mexico.

Academic training

Young artists spent four years in rigorous training. In France, only students who passed an exam and carried a letter of reference from a noted professor of art were accepted at the academy's school, the École des Beaux-Arts. Drawings and paintings of the nude, called "académies," were the basic building blocks of academic art and the procedure for learning to make them was clearly defined. First, students copied prints after classical sculptures, becoming familiar with the principles of contour, light, and shade. The copy was believed crucial to the academic education; from copying works of past artists one would assimilate their methods of art making. To advance to the next step, and every successive one, students presented drawings for evaluation.

Young artists spent four years in rigorous training. In France, only students who passed an exam and carried a letter of reference from a noted professor of art were accepted at the academy's school, the École des Beaux-Arts. Drawings and paintings of the nude, called "académies," were the basic building blocks of academic art and the procedure for learning to make them was clearly defined. First, students copied prints after classical sculptures, becoming familiar with the principles of contour, light, and shade. The copy was believed crucial to the academic education; from copying works of past artists one would assimilate their methods of art making. To advance to the next step, and every successive one, students presented drawings for evaluation.

Criticism and legacy

Academic art was first criticized for its use of idealism, by Realist artists such as Gustave Courbet, as being based on idealistic clichés and representing mythical and legendary motives while contemporary social concerns were being ignored. Another criticism by Realists was the " false surface" of paintings—the objects depicted looked smooth, slick, and idealized—showing no real texture. The Realist

Academic art was first criticized for its use of idealism, by Realist artists such as Gustave Courbet, as being based on idealistic clichés and representing mythical and legendary motives while contemporary social concerns were being ignored. Another criticism by Realists was the " false surface" of paintings—the objects depicted looked smooth, slick, and idealized—showing no real texture. The Realist Théodule Ribot

Théodule-Augustin Ribot (August 8, 1823September 11, 1891) was a French realist painter and printmaker.

He was born in Saint-Nicolas-d'Attez, and studied at the École des Arts et Métiers de Châlons before moving to Paris in 1845. There he ...

worked against this by experimenting with rough, unfinished textures in his painting.

Stylistically, the Impressionists, who advocated quickly painting outdoors exactly what the eye sees and the hand puts down, criticized the finished and idealized painting style. Although academic painters began a painting by first making drawings and then painting oil sketches

An oil sketch or oil study is an artwork made primarily in oil paint in preparation for a larger, finished work. Originally these were created as preparatory studies or modelli, especially so as to gain approval for the design of a larger commissi ...

of their subject, the high polish they gave to their drawings seemed to the Impressionists tantamount to a lie. After the oil sketch, the artist would produce the final painting with the academic "fini," changing the painting to meet stylistic standards and attempting to idealize the images and add perfect detail. Similarly, perspective is constructed geometrically on a flat surface and is not really the product of sight; Impressionists disavowed the devotion to mechanical techniques.

Realists and Impressionists also defied the placement of still-life and landscape at the bottom of the hierarchy of genres. It is important to note that most Realists and Impressionists and others among the early avant-garde who rebelled against academism were originally students in academic ateliers

An atelier () is the private workshop or studio of a professional artist in the fine or decorative arts or an architect, where a principal master and a number of assistants, students, and apprentices can work together producing fine art or v ...

. Claude Monet, Gustave Courbet, Édouard Manet, and even Henri Matisse were students under academic artists.

As modern art

Modern art includes artistic work produced during the period extending roughly from the 1860s to the 1970s, and denotes the styles and philosophies of the art produced during that era. The term is usually associated with art in which the tradi ...

and its avant-garde gained more power, academic art was further denigrated, and seen as sentimental, clichéd, conservative, non-innovative, bourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. They ...

, and "styleless." The French referred derisively to the style of academic art as '' L'art Pompier'' (''pompier'' means "fireman") alluding to the paintings of Jacques-Louis David

Jacques-Louis David (; 30 August 1748 – 29 December 1825) was a French painter in the Neoclassicism, Neoclassical style, considered to be the preeminent painter of the era. In the 1780s, his cerebral brand of history painting marked a change in ...

(who was held in esteem by the academy) which often depicted soldiers wearing fireman-like helmets. The paintings were called "grandes machines" which were said to have manufactured false emotion through contrivances and tricks.

This denigration of academic art reached its peak through the writings of art critic Clement Greenberg who stated that all academic art is " kitsch." Other artists, such as the Symbolist painters and some of the Surrealists

Surrealism is a cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists depicted unnerving, illogical scenes and developed techniques to allow the unconscious mind to express itself. Its aim was, according to l ...

, were kinder to the tradition. As painters who sought to bring imaginary vistas to life, these artists were more willing to learn from a strongly representational tradition. Once the tradition had come to be looked on as old-fashioned, the allegorical nudes and theatrically posed figures struck some viewers as bizarre and dreamlike.

With the goals of Postmodernism

Postmodernism is an intellectual stance or Rhetorical modes, mode of discourseNuyen, A.T., 1992. The Role of Rhetorical Devices in Postmodernist Discourse. Philosophy & Rhetoric, pp.183–194. characterized by philosophical skepticism, skepticis ...

in giving a fuller, more sociological and pluralistic account of history, academic art has been brought back into history books and discussion. Since the early 1990s, academic art has even experienced a limited resurgence through the Classical Realist atelier movement. Additionally, the art is gaining a broader appreciation by the public at large, and whereas academic paintings once would only fetch a few hundreds of dollars in auctions, some now fetch millions.Esterow, Milton (1 January 2011)"From 'Riches to Rags to Riches'"

''ArtNews''. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

Major artists

References

Further reading

* ''Art and the Academy in the Nineteenth Century''. (2000). Denis, Rafael Cardoso & Trodd, Colin (Eds). Rutgers University Press. * ''L'Art-Pompier''. (1998). Lécharny, Louis-Marie, Que sais-je?, Presses Universitaires de France. * ''L'Art pompier: immagini, significati, presenze dell'altro Ottocento francese (1860–1890)''. (1997). Luderin, Pierpaolo, Pocket library of studies in art, Olschki.External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Academic Art 19th century in art Art movements