Abbot Of Reculver on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

St Mary's Church, Reculver, was founded in the 7th century as either a minster or a

St Mary's Church, Reculver, was founded in the 7th century as either a minster or a

The first church known to have existed at Reculver was founded in 669, when King

The first church known to have existed at Reculver was founded in 669, when King  Ten years after the foundation of the church, in 679, King

Ten years after the foundation of the church, in 679, King  By the early 9th century the monastery had become "extremely wealthy", but from then on it appears in records as "essentially a piece of property". For most of the period from 764 to 825 Kent was under the control of kings of

By the early 9th century the monastery had become "extremely wealthy", but from then on it appears in records as "essentially a piece of property". For most of the period from 764 to 825 Kent was under the control of kings of

Reculver may have remained home to a religious community into the 10th century, despite its vulnerability to Viking attacks. It is possible that the abbot and community of Reculver took refuge from the Vikings in Canterbury, as the abbess and community of Lyminge did in 804. A monk of Reculver named Ymar was recorded as a saint in the early 15th century by

Reculver may have remained home to a religious community into the 10th century, despite its vulnerability to Viking attacks. It is possible that the abbot and community of Reculver took refuge from the Vikings in Canterbury, as the abbess and community of Lyminge did in 804. A monk of Reculver named Ymar was recorded as a saint in the early 15th century by

The high cross described by Leland had been removed from the church by 1784. Archaeologists examined what was believed to be the base of a 7th-century cross in 1878 and the 1920s, and it has been suggested that the monastery at Reculver was originally built around it. The Reculver cross has been compared with the Anglo-Saxon

The high cross described by Leland had been removed from the church by 1784. Archaeologists examined what was believed to be the base of a 7th-century cross in 1878 and the 1920s, and it has been suggested that the monastery at Reculver was originally built around it. The Reculver cross has been compared with the Anglo-Saxon

When Leland visited Reculver in 1540, he noted that the coastline to the north had receded to within little more than a quarter of a mile (402 m) of the "Towne

When Leland visited Reculver in 1540, he noted that the coastline to the north had receded to within little more than a quarter of a mile (402 m) of the "Towne

The demolition of this "shrine of early Christendom", and

The demolition of this "shrine of early Christendom", and

The first archaeological report on the then demolished church of St Mary was published by George Dowker in 1878. He described finding the foundations of the apsidal chancel and of the columns that formed part of the triple chancel arch, and noted that the original floor of the church was of concrete, or ''

The first archaeological report on the then demolished church of St Mary was published by George Dowker in 1878. He described finding the foundations of the apsidal chancel and of the columns that formed part of the triple chancel arch, and noted that the original floor of the church was of concrete, or ''

The design of the twin towers, spires and west front of

The design of the twin towers, spires and west front of

St Mary's Church, Reculver, was founded in the 7th century as either a minster or a

St Mary's Church, Reculver, was founded in the 7th century as either a minster or a monastery

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone ( hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer whi ...

on the site of a Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

fort at Reculver

Reculver is a village and coastal resort about east of Herne Bay on the north coast of Kent in south-east England.

It is in the ward of the same name, in the City of Canterbury district of Kent.

Reculver once occupied a strategic location ...

, which was then at the north-eastern extremity of Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

in south-eastern England. In 669, the site of the fort was given for this purpose by King Ecgberht of Kent

Ecgberht I (also spelled Egbert) (died 4 July 673) was a King of Kent (664-673), succeeding his father Eorcenberht.

He may have still been a child when he became king following his father's death on 14 July 664, because his mother Seaxburh was ...

to a priest named Bassa, beginning a connection with Kentish kings that led to King Eadberht II Eadberht is an Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of th ...

of Kent being buried there in the 760s, and the church becoming very wealthy by the beginning of the 9th century. From the early 9th century to the 11th the church was treated as essentially a piece of property, with control passing between kings of Mercia

la, Merciorum regnum

, conventional_long_name=Kingdom of Mercia

, common_name=Mercia

, status=Kingdom

, status_text=Independent kingdom (527–879) Client state of Wessex ()

, life_span=527–918

, era= Heptarchy

, event_start=

, date_start=

, ...

, Wessex

la, Regnum Occidentalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the West Saxons

, common_name = Wessex

, image_map = Southern British Isles 9th century.svg

, map_caption = S ...

and England and the archbishops of Canterbury. Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

attacks may have extinguished the church's religious community in the 9th century, although an early 11th-century record indicates that the church was then in the hands of a dean

Dean may refer to:

People

* Dean (given name)

* Dean (surname), a surname of Anglo-Saxon English origin

* Dean (South Korean singer), a stage name for singer Kwon Hyuk

* Dean Delannoit, a Belgian singer most known by the mononym Dean

Titles

* ...

accompanied by monk

A monk (, from el, μοναχός, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedica ...

s. By the time of Domesday Book

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manus ...

, completed in 1086, St Mary's was serving as a parish church

A parish church (or parochial church) in Christianity is the church which acts as the religious centre of a parish. In many parts of the world, especially in rural areas, the parish church may play a significant role in community activities, ...

.

The original building, which incorporated stone and tiles scavenged from the Roman fort, was a simple one consisting only of a nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

and an apsidal

In architecture, an apse (plural apses; from Latin 'arch, vault' from Ancient Greek 'arch'; sometimes written apsis, plural apsides) is a semicircular recess covered with a hemispherical vault or semi-dome, also known as an ''exedra''. In ...

chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may terminate in an apse.

Ov ...

, with a small room, or porticus

A porticus, in church architecture and archaeology, is usually a small room in a church. Commonly, porticus form extensions to the north and south sides of a church, giving the building a cruciform plan. They may function as chapels, rudimentary ...

, built out from each of the church's northern and southern sides where the nave and chancel met. The church was much altered and expanded during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, including the addition of twin towers in the 12th century; the last addition, in the 15th century, was of north and south porches leading into the nave. This expansion coincided with a long period of prosperity for the settlement of Reculver: the settlement's decline led to the church's decay and, following unsuccessful attempts to prevent the erosion

Erosion is the action of surface processes (such as water flow or wind) that removes soil, rock, or dissolved material from one location on the Earth's crust, and then transports it to another location where it is deposited. Erosion is dis ...

of the adjacent coastline, the building was almost completely demolished in 1809.

The church's remains were preserved by the intervention of Trinity House

"Three In One"

, formation =

, founding_location = Deptford, London, England

, status = Royal Charter corporation and registered charity

, purpose = Maintenance of lighthouses, buoys and beacons

, he ...

in 1810, since the towers had long been important as a landmark for shipping: preservation was achieved through the first effective effort to protect the cliff on which the church then stood from further erosion. Some materials from the structure were incorporated into a replacement church, also dedicated to St Mary, built at Hillborough in the same parish. Much of the rest was used for the building of a new harbour wall at Margate

Margate is a seaside town on the north coast of Kent in south-east England. The town is estimated to be 1.5 miles long, north-east of Canterbury and includes Cliftonville, Garlinge, Palm Bay and Westbrook.

The town has been a significan ...

, known as Margate Pier. Other, surviving remnants include fragments of a high cross of stone that once stood inside the church, and two stone columns from a triple arch between the nave and chancel: the columns formed part of the original church and were still in place when demolition began. The cross fragments and columns are now kept in Canterbury Cathedral, and are among features that have led to the church being described as an exemplar An exemplar is a person, a place, an object, or some other entity that serves as a predominant example of a given concept (e.g. "The heroine became an ''exemplar'' in courage to the children"). It may also refer to:

* Exemplar, a well-known scienc ...

of Anglo-Saxon church architecture and sculpture

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable ...

.

Origins

The first church known to have existed at Reculver was founded in 669, when King

The first church known to have existed at Reculver was founded in 669, when King Ecgberht of Kent

Ecgberht I (also spelled Egbert) (died 4 July 673) was a King of Kent (664-673), succeeding his father Eorcenberht.

He may have still been a child when he became king following his father's death on 14 July 664, because his mother Seaxburh was ...

gave land there to Bassa the priest for this purpose.; ; ; . The author of the '' Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' "clearly considered this to be a significant event", and it may be that King Ecgberht's intention in founding a church at Reculver was to create an ecclesiastical centre with a strong English element, to counterbalance domination of the Canterbury Church by Archbishop Theodore

Theodore may refer to:

Places

* Theodore, Alabama, United States

* Theodore, Australian Capital Territory

* Theodore, Queensland, a town in the Shire of Banana, Australia

* Theodore, Saskatchewan, Canada

* Theodore Reservoir, a lake in Sask ...

, from Tarsus, now in Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula in ...

, Abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the male head of a monastery in various Western religious traditions, including Christianity. The office may also be given as an honorary title to a clergyman who is not the head of a monastery. The ...

Hadrian of St Augustine's, from North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, probably Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika ( ar, برقة, Barqah, grc-koi, Κυρηναϊκή ��παρχίαKurēnaïkḗ parkhíā}, after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between ...

, and their equally "non-native followers." Historians vary over whether to call the church a minster or a monastery

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone ( hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer whi ...

– thus Susan Kelly uses the former term, but Nicholas Brooks uses the latter, commenting that:

The foundation of this church, sited within the remains of the Roman fort of ''Regulbium

Regulbium was the name of an ancient Roman fort of the Saxon Shore in the vicinity of the modern English resort of Reculver in Kent. Its name derives from the local Brythonic language, meaning "great headland" (*''Rogulbion'').

History

The f ...

'', exemplifies the "widespread practice n Anglo-Saxon Englandof re-using Roman walled places for major churches"; the new church was built "almost completely from demolished Roman structures". The building formed a nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

measuring by and an apsidal

In architecture, an apse (plural apses; from Latin 'arch, vault' from Ancient Greek 'arch'; sometimes written apsis, plural apsides) is a semicircular recess covered with a hemispherical vault or semi-dome, also known as an ''exedra''. In ...

chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may terminate in an apse.

Ov ...

, which was externally polygonal but internally round, and was separated from the nave by a triple arch formed by two columns made of limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

from Marquise, in the Pas-de-Calais region of northern France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

. The arches were formed using Roman tiles, but the columns were made for the church rather than being Roman in origin, and their form has been attributed to late-Roman and early Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

architectural influences, probably transmitted via the contemporary architecture of Merovingian

The Merovingian dynasty () was the ruling family of the Franks from the middle of the 5th century until 751. They first appear as "Kings of the Franks" in the Roman army of northern Gaul. By 509 they had united all the Franks and northern Gauli ...

France. Around the inside of the apse was a stone bench, and two small rooms, or porticus

A porticus, in church architecture and archaeology, is usually a small room in a church. Commonly, porticus form extensions to the north and south sides of a church, giving the building a cruciform plan. They may function as chapels, rudimentary ...

, forming rudimentary transept

A transept (with two semitransepts) is a transverse part of any building, which lies across the main body of the building. In cruciform churches, a transept is an area set crosswise to the nave in a cruciform ("cross-shaped") building wi ...

s were built out from the north and south sides of the church where the nave met the chancel, from which they could be accessed. The presence of a stone bench around the inside of the apse has been attributed to influence from the Syrian Church, at a time when its followers were being displaced. The walls of the church were rendered inside and out, giving them a plain appearance and hiding the masonry.

Ten years after the foundation of the church, in 679, King

Ten years after the foundation of the church, in 679, King Hlothhere

Hlothhere ( ang, Hloþhere; died 6 February 685) was a King of Kent who ruled from 673 to 685.

Hlothhere succeeded his brother Ecgberht I in 673. His parents were Eorcenberht of Kent and Seaxburh of Ely, the daughter of Anna of East Anglia. In ...

of Kent granted lands at Sturry

Sturry is a village on the Great Stour river situated northeast of Canterbury in Kent. Its large civil parish incorporates several hamlets and, until April 2019, the former mining village of Hersden.

Geography

Sturry lies at the old Roman jun ...

, about south-west of Reculver, and at Sarre, in the western part of the Isle of Thanet

The Isle of Thanet () is a peninsula forming the easternmost part of Kent, England. While in the past it was separated from the mainland by the Wantsum Channel, it is no longer an island.

Archaeological remains testify to its settlement in an ...

, across the Wantsum Channel

The Wantsum Channel was a strait separating the Isle of Thanet from the north-eastern extremity of the English county of Kent and connecting the English Channel and the Thames Estuary. It was a major shipping route when Britain was part of the Rom ...

to the east, to Abbot Berhtwald and his "monastery". The grant was made at Reculver, and the charter in which it was recorded was probably written by a Reculver scribe. The grant of Sarre in particular is significant:

In the original, 7th-century charter recording this grant, Reculver is referred to as a ''civitas'', or city, but this is probably a reference to either its Roman past or the church's monastic status, rather than a large population centre. In 692 Reculver's abbot Berhtwald was elected Archbishop of Canterbury, from which position he probably offered Reculver patronage and support. Bede, writing no more than 40 years later, described Berhtwald as having been well educated in the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts ...

and experienced in ecclesiastical and monastic affairs, but in terms indicating that Berhtwald was not a scholar.

Further charters show that the monastery at Reculver continued to benefit from Kentish kings in the 8th century, under abbots Heahberht ( fl. 748x762), Deneheah (fl. 760) and Hwitred (fl. 784), acquiring lands in Higham and Sheldwich and exemption from the toll due on one ship at Fordwich

Fordwich is a market town and a civil parish in east Kent, England, on the River Stour, northeast of Canterbury.

It is the smallest community by population in Britain with a town council. Its population increased by 30 between 2001 and 2011.

...

, and King Eadberht II Eadberht is an Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of th ...

of Kent was buried in the church in the 760s. Properties belonging to Reculver in the 7th and 8th centuries are indicated in passing by otherwise unrelated records, such as the estate at Higham, land probably in the High Weald area of Kent, from which iron may have been sourced for use or sale at or on behalf of Reculver, and an unidentified property named ''Dunwaling land'' in the district of Eastry

Eastry is a civil parish in Kent, England, around southwest of Sandwich. It was voted "Kent Village of the Year 2005".

The name is derived from the Old English ''Ēast- rige'', meaning "eastern province" (c.f. '' Sūþ-rige'' "southern provinc ...

. Such records also identify other abbots of Reculver, namely Æthelmær (fl. 699), Bære (fl. 761x764), Æthelheah (fl. 803), Dudeman (fl. 805), Beornwine (fl. 811x826), Baegmund (fl. 832x839), Daegmund (fl. 825x883) and Beornhelm (fl. 867x905).

By the early 9th century the monastery had become "extremely wealthy", but from then on it appears in records as "essentially a piece of property". For most of the period from 764 to 825 Kent was under the control of kings of

By the early 9th century the monastery had become "extremely wealthy", but from then on it appears in records as "essentially a piece of property". For most of the period from 764 to 825 Kent was under the control of kings of Mercia

la, Merciorum regnum

, conventional_long_name=Kingdom of Mercia

, common_name=Mercia

, status=Kingdom

, status_text=Independent kingdom (527–879) Client state of Wessex ()

, life_span=527–918

, era= Heptarchy

, event_start=

, date_start=

, ...

, beginning with Offa (757–96), who treated Kent as part of his patrimony: he may also have claimed direct control of Reculver, as he did with similar churches in other areas. In 811 control of the monastery appears to have been in the hands of Archbishop Wulfred

Wulfred (died 24 March 832) was an Anglo-Saxon Archbishop of Canterbury in medieval England. Nothing is known of his life prior to 803, when he attended a church council, but he was probably a nobleman from Middlesex. He was elected archbishop ...

of Canterbury, who is recorded as having deprived it of some of its land. But by 817 Reculver was in the hands of King Coenwulf of Mercia

Coenwulf (; also spelled Cenwulf, Kenulf, or Kenwulph; la, Coenulfus) was the King of Mercia from December 796 until his death in 821. He was a descendant of King Pybba, who ruled Mercia in the early 7th century. He succeeded Ecgfrith, the son ...

(796–821), together with the nunnery at Minster-in-Thanet

Minster, also known as Minster-in-Thanet, is a village and civil parish in the Thanet District of Kent, England. It is the site of Minster in Thanet Priory. The village is west of Ramsgate (which is the post town) and to the north east of Cant ...

, through which he would also have had strategically lucrative control of the Wantsum Channel: Coenwulf had by then secured a privilege from Pope Leo III that gave him the right to "dispose of his ... monasteries in nglandat will". In that year a "monumental showdown" began between Archbishop Wulfred and King Coenwulf over the control of monasteries, featuring Reculver and Minster-in-Thanet in particular. The dispute over Reculver continued until 821, when Wulfred "made a humiliating submission to oenwulf, surrendering to him an estate of 300 hides, possibly at Eynsham in Oxfordshire, and paying a fine of £120, to secure the return of Reculver and Minster-in-Thanet. The record of the dispute indicates that Wulfred continued to be denied control of Reculver and Minster-in-Thanet after 821 by Cwoenthryth

Cwenthryth (also Quendreda, ang, Cwēnþrȳð) was a princess of Mercia, an Anglo-Saxon kingdom in central England, who lived in the early 9th century.

She was the daughter of Coenwulf of Mercia and the sister of Saint Kenelm and also the siste ...

, Coenwulf's heir and abbess of Minster-in-Thanet, until a final settlement was reached at a synod at ''Clofesho'' in 825.

From 825 control of Kent fell to the kings of Wessex

la, Regnum Occidentalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the West Saxons

, common_name = Wessex

, image_map = Southern British Isles 9th century.svg

, map_caption = S ...

, and a compromise was reached between Archbishop Ceolnoth

Ceolnoth or Ceolnoþ (; died 870) was a medieval English Archbishop of Canterbury. Although later chroniclers stated he had previously held ecclesiastical office in Canterbury, there is no contemporary evidence of this, and his first appearance i ...

and King Egbert

Egbert is a name that derives from old Germanic words meaning "bright edge", such as that of a blade. Anglo-Saxon variant spellings include Ecgberht () and Ecgbert. German variant spellings include Ekbert and Ecbert.

People with the first name Mid ...

in 838, confirmed by his son Æthelwulf in 839, recognising Egbert and Æthelwulf as lay lords and protectors of monasteries and reserving spiritual lordship, particularly over election of abbots and abbesses, to bishops. One copy of the record of this agreement was preserved either at Reculver or at Lyminge. A factor leading to this abandonment of Wulfred's strict policy may have been the increasing intensity of Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

attacks, which had begun in Kent in the late 8th century and had seen the ravaging of the Isle of Sheppey

The Isle of Sheppey is an island off the northern coast of Kent, England, neighbouring the Thames Estuary, centred from central London. It has an area of . The island forms part of the local government district of Swale. ''Sheppey'' is derive ...

in 835. An army of Vikings spent the winter of 851 on the Isle of Thanet and the same occurred on the Isle of Sheppey in 855. Reculver, like most of the Kentish monasteries, lay in an exposed coastal location, and would have presented an obvious target for Vikings in search of treasure. By the 10th century the monastery at Reculver had ceased to be an important church in Kent and, together with its territory, it was in the hands of the kings of Wessex alone. In a charter of 949 King Eadred

Eadred (c. 923 – 23 November 955) was King of the English from 26 May 946 until his death. He was the younger son of Edward the Elder and his third wife Eadgifu, and a grandson of Alfred the Great. His elder brother, Edmund, was killed try ...

of England gave Reculver back to the archbishops of Canterbury, at which time the estate included Hoath and Herne, land at Sarre, in Thanet, and land at Chilmington, about south-west of Reculver.

Monastery to parish church

Reculver may have remained home to a religious community into the 10th century, despite its vulnerability to Viking attacks. It is possible that the abbot and community of Reculver took refuge from the Vikings in Canterbury, as the abbess and community of Lyminge did in 804. A monk of Reculver named Ymar was recorded as a saint in the early 15th century by

Reculver may have remained home to a religious community into the 10th century, despite its vulnerability to Viking attacks. It is possible that the abbot and community of Reculver took refuge from the Vikings in Canterbury, as the abbess and community of Lyminge did in 804. A monk of Reculver named Ymar was recorded as a saint in the early 15th century by Thomas Elmham

Thomas Elmham (1364in or after 1427) was an English chronicler.

Life

Thomas Elmham was probably born at North Elmham in Norfolk. He may have been the Thomas Elmham who was a scholar at King's Hall, Cambridge from 1389 to 1394. He became a Bened ...

, who found the name in a martyrology

A martyrology is a catalogue or list of martyrs and other saints and beati arranged in the calendar order of their anniversaries or feasts. Local martyrologies record exclusively the custom of a particular Church. Local lists were enriched by n ...

, and wrote that Ymar was buried in St John's Church, Margate

Margate is a seaside town on the north coast of Kent in south-east England. The town is estimated to be 1.5 miles long, north-east of Canterbury and includes Cliftonville, Garlinge, Palm Bay and Westbrook.

The town has been a significan ...

: Ymar was probably killed by Vikings in the 10th century, and hence regarded as a martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

. The Church in East Kent

Kent is a traditional county in South East England with long-established human occupation.

Prehistoric Kent

Kent has been occupied since the Lower Palaeolithic as finds from the quarries at Fordwich and Swanscombe attest. The Swanscombe sku ...

seems broadly to have "preserved its primary ... character against all the odds", but evidence for the monastery at Reculver is lacking: by the 11th century the monastery had "dropped out of sight entirely". The last abbot is recorded as ''Wenredus'': although it is unknown when he was abbot, it must have been after 890 – possibly 905 – when the name of Abbot Beornhelm last appears in Anglo-Saxon charters. The church was last described as a monastery in about 1030, when it was governed by a dean

Dean may refer to:

People

* Dean (given name)

* Dean (surname), a surname of Anglo-Saxon English origin

* Dean (South Korean singer), a stage name for singer Kwon Hyuk

* Dean Delannoit, a Belgian singer most known by the mononym Dean

Titles

* ...

named Givehard and was home to monks, two of whom are named as Fresnot and Tancrad: these names indicate the presence of a religious community from the European continent, probably Flemings

The Flemish or Flemings ( nl, Vlamingen ) are a Germanic peoples, Germanic ethnic group native to Flanders, Belgium, who speak Dutch language, Dutch. Flemish people make up the majority of Belgians, at about 60%.

"''Flemish''" was historically ...

. This may have been nothing more than a temporary "resurgence of communal life at Reculver, at least for a period in the earlier eleventh century. ... erhapsthe old minster ... was provided as a refuge for a body of foreign clerics".

By 1066 the monastery had become a parish church, with no baptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost ...

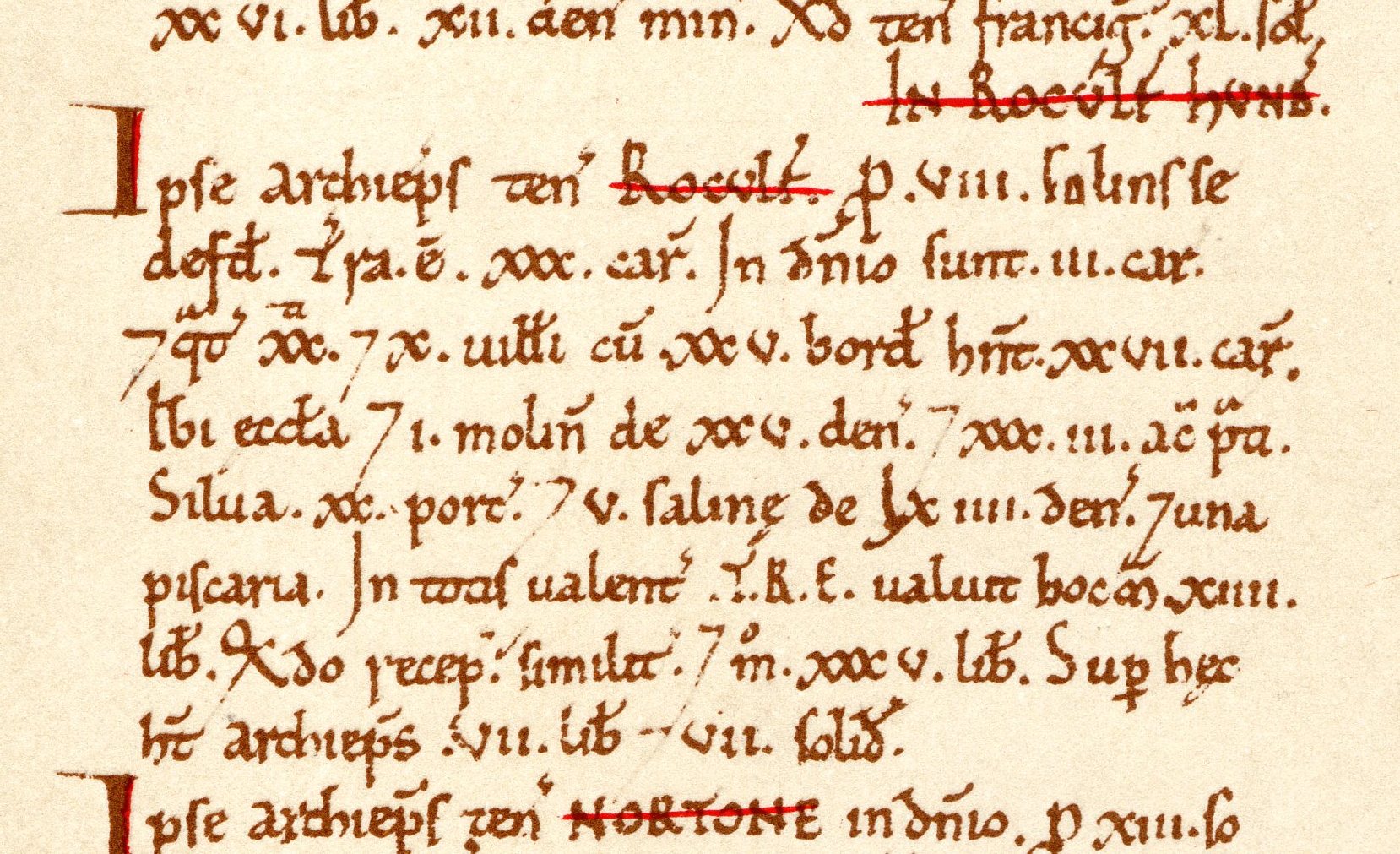

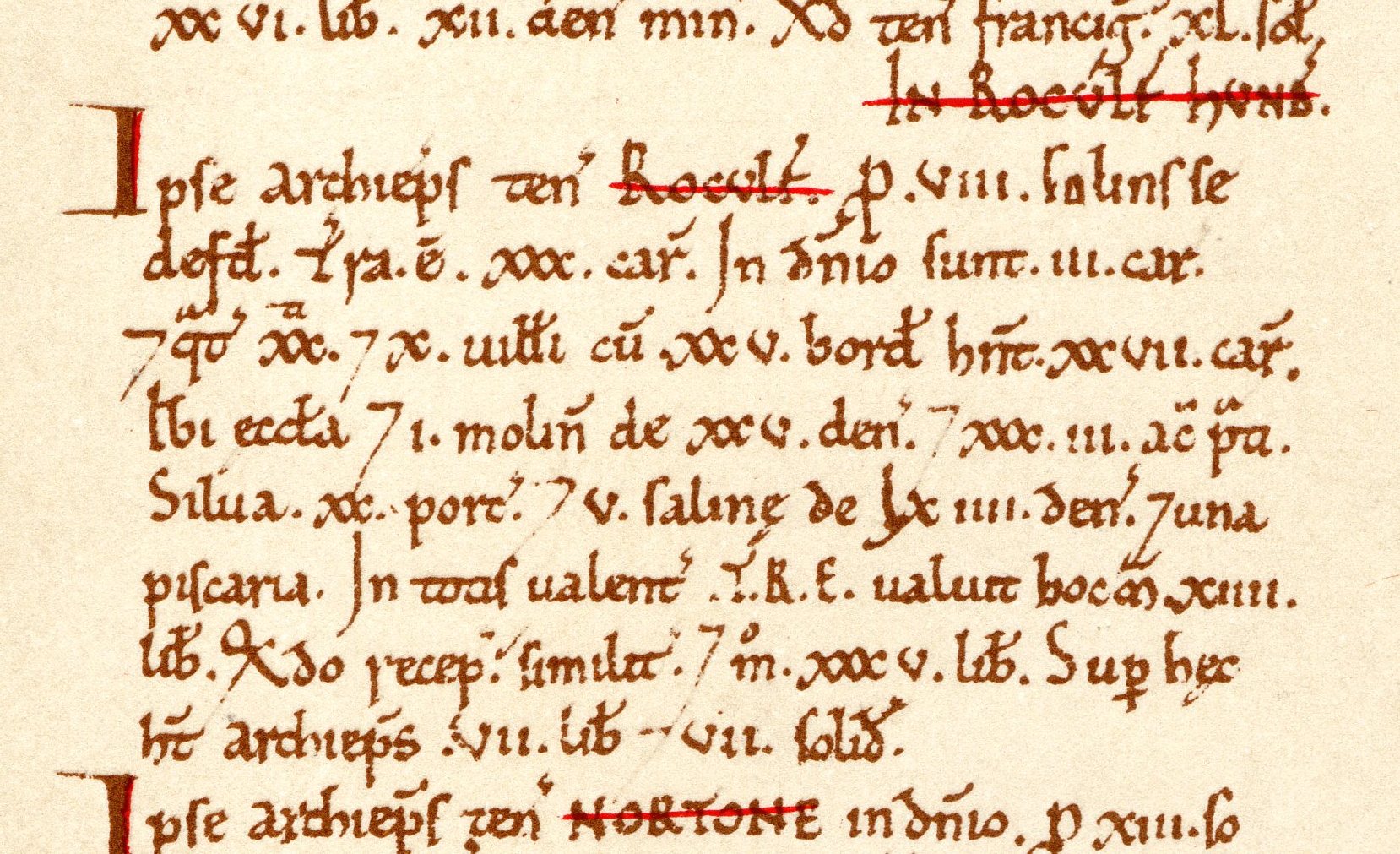

al function. In 1086, Reculver was listed in Domesday Book

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manus ...

among lands belonging to the archbishop of Canterbury: in practice, however, it must previously have been lost to him again, since William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first House of Normandy, Norman List of English monarchs#House of Norman ...

is recorded as having returned it to the archbishop, along with other churches and properties, at his death, which occurred in 1087. The value of the manor of Reculver in 1066 is given as £14, but in 1086 it was worth a total of £42.7s. (£42.35): this can be compared with, for example, the £20 due to the archbishop from the manor of Maidstone

Maidstone is the largest town in Kent, England, of which it is the county town. Maidstone is historically important and lies 32 miles (51 km) east-south-east of London. The River Medway runs through the centre of the town, linking it wi ...

, and £50 from the borough

A borough is an administrative division in various English-speaking countries. In principle, the term ''borough'' designates a self-governing walled town, although in practice, official use of the term varies widely.

History

In the Middle A ...

of Sandwich

A sandwich is a food typically consisting of vegetables, sliced cheese or meat, placed on or between slices of bread, or more generally any dish wherein bread serves as a container or wrapper for another food type. The sandwich began as a po ...

. Included in the Domesday account for Reculver, as well as the church, farmland, a mill, salt pans and a fishery, are 90 villeins

A villein, otherwise known as ''cottar'' or '' crofter'', is a serf tied to the land in the feudal system. Villeins had more rights and social status than those in slavery, but were under a number of legal restrictions which differentiated them ...

and 25 bordars

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

: these numbers can be multiplied four or five times to account for dependents, as they only represent "adult male heads of households".

By the 13th century Reculver parish provided an ecclesiastical benefice of "exceptional wealth", which led to disputes between lay and Church interests. In 1291 the ''Taxatio'' of Pope Nicholas IV put the total income due to the rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

and vicar

A vicar (; Latin: '' vicarius'') is a representative, deputy or substitute; anyone acting "in the person of" or agent for a superior (compare "vicarious" in the sense of "at second hand"). Linguistically, ''vicar'' is cognate with the English pre ...

of Reculver at about £130. Included in the parish were chapels of ease

A chapel of ease (or chapel-of-ease) is a church building other than the parish church, built within the bounds of a parish for the attendance of those who cannot reach the parish church conveniently.

Often a chapel of ease is deliberately bu ...

at St Nicholas-at-Wade

St Nicholas-at-Wade (or St Nicholas) is both a village and a civil parish in the Thanet District of Kent, England. The parish had a recorded population of 782 at the 2001 Census, increasing to 852 at the 2011 census. The village of Sarre is part ...

and All Saints' Church, Shuart, both on the Isle of Thanet, and at Hoath and Herne. The parish was broken up in 1310 by Robert Winchelsey

Robert Winchelsey (or Winchelsea; c. 1245 – 11 May 1313) was an English Catholic theologian and Archbishop of Canterbury. He studied at the universities of Paris and Oxford, and later taught at both. Influenced by Thomas Aquinas, he was a s ...

, archbishop of Canterbury from 1294 to 1313, who created parishes from Reculver's chapelries at Herne and, on the Isle of Thanet, St Nicholas-at-Wade and Shuart, in response to the difficulties posed by the distance between them and their mother church at Reculver, and a "steady increase in population", which Winchelsey estimated at more than 3,000. At this time Shuart became part of St Nicholas-at-Wade parish, and its church was later demolished. However, St Mary's Church, Reculver, continued to receive payments from the parishes of Herne and St Nicholas-at-Wade in the 19th century as a "token of subjection to Reculver", as well as for the repair of St Mary's Church, and the parish retained a perpetual curacy

Perpetual curate was a class of resident parish priest or incumbent curate within the United Church of England and Ireland (name of the combined Anglican churches of England and Ireland from 1800 to 1871). The term is found in common use mainly du ...

at Hoath until 1960.

Enlargement and decline

Enlargement

The church building was considerably enlarged over time. The outer walls of the north and south porticus were extended westwards to enclose the nave in the 8th century, forming a series of rooms, including chapels on both northern and southern sides, and a porch across the western side. The towers were added as part of an extension with a new west front in the late 12th century, when the internal walls of the rooms added in the 8th century were demolished, creatingaisle

An aisle is, in general, a space for walking with rows of non-walking spaces on both sides. Aisles with seating on both sides can be seen in airplanes, certain types of buildings, such as churches, cathedrals, synagogues, meeting halls, par ...

s on the north and south sides of the nave. In the 13th century the original apse was demolished and the chancel more than doubled in size, incorporating a triple east window of lancets with columns of Purbeck Marble, and in the 15th century north and south porches were added to the nave. At some point in the same period, according to J. Russell Larkby, a sundial was added to the south wall of the south tower, about from the ground. A chantry

A chantry is an ecclesiastical term that may have either of two related meanings:

# a chantry service, a Christian liturgy of prayers for the dead, which historically was an obiit, or

# a chantry chapel, a building on private land, or an area i ...

in the church was endowed in 1354 in memory of Alicia de Brouke, and two more were endowed in 1371 by Thomas Niewe, a former vicar of Reculver. These chantries were suppressed in the reign of Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

, in 1548 or very early in 1549. The towers were topped with spire

A spire is a tall, slender, pointed structure on top of a roof of a building or tower, especially at the summit of church steeples. A spire may have a square, circular, or polygonal plan, with a roughly conical or pyramidal shape. Spires a ...

s by 1414, since they are shown in an illustrated map drawn by Thomas Elmham in or before that year, and the north tower held a ring of bells

A "ring of bells" is the name bell ringers give to a set of bells hung for English full circle ringing. The term "peal of bells" is often used, though peal also refers to a change ringing performance of more than about 5,000 changes.

By ri ...

, accessed by a spiral staircase

Stairs are a structure designed to bridge a large vertical distance between lower and higher levels by dividing it into smaller vertical distances. This is achieved as a diagonal series of horizontal platforms called steps which enable passage ...

. The addition of the towers, "an extraordinary investment ... for a parish church", and the extent to which the church was enlarged in the Middle Ages, suggest that "a thriving township must have developed nearby." Despite all the building work, the church retained many prominent Anglo-Saxon features, and one in particular roused John Leland to "an enthusiasm which he seldom displayed" when he visited Reculver in 1540:

The high cross described by Leland had been removed from the church by 1784. Archaeologists examined what was believed to be the base of a 7th-century cross in 1878 and the 1920s, and it has been suggested that the monastery at Reculver was originally built around it. The Reculver cross has been compared with the Anglo-Saxon

The high cross described by Leland had been removed from the church by 1784. Archaeologists examined what was believed to be the base of a 7th-century cross in 1878 and the 1920s, and it has been suggested that the monastery at Reculver was originally built around it. The Reculver cross has been compared with the Anglo-Saxon Ruthwell Cross

The Ruthwell Cross is a stone Anglo-Saxon cross probably dating from the 8th century, when the village of Ruthwell, now in Scotland, was part of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria.

It is the most famous and elaborate Anglo-Saxon monumental ...

– an open-air preaching cross

A preaching cross is a Christian cross sometimes surmounting a pulpit, which is erected outdoors to designate a preaching place.

In Britain and Ireland, many free-standing upright crosses – or high crosses – were erected. Some of these c ...

in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland – and traces of paint on fragments of the Reculver cross show that its details were once multicoloured. Later, stylistic assessments indicate that the cross, carved from a re-used Roman column, probably dates from the 8th century or the 9th, and that the stone believed to have been the base may have been the foundation for the original, 7th-century altar

An altar is a table or platform for the presentation of religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. Altars are found at shrines, temples, churches, and other places of worship. They are used particularly in paga ...

. Leland also reported a wall painting

A mural is any piece of graphic artwork that is painted or applied directly to a wall, ceiling or other permanent substrate. Mural techniques include fresco, mosaic, graffiti and marouflage.

Word mural in art

The word ''mural'' is a Spanish ...

of an unidentified bishop, on the north side of the church under an arch. Another Anglo-Saxon item Leland found in the church was a gospel book

A Gospel Book, Evangelion, or Book of the Gospels (Greek: , ''Evangélion'') is a codex or bound volume containing one or more of the four Gospels of the Christian New Testament – normally all four – centering on the life of Jesus of Nazareth ...

: this was

In its final form, the church consisted of a nave long by wide, with north and south aisles of the same length and wide, and a chancel long by wide. Including the spires, the towers were high, the surviving towers alone reaching . The towers measure square internally, and are connected internally by a gallery that was about above the floor of the nave. The overall length of the church was , and the breadth of the west front, which also survives, is .

Decline

When Leland visited Reculver in 1540, he noted that the coastline to the north had receded to within little more than a quarter of a mile (402 m) of the "Towne

When Leland visited Reculver in 1540, he noted that the coastline to the north had receded to within little more than a quarter of a mile (402 m) of the "Towne hich

Ij ( fa, ايج, also Romanized as Īj; also known as Hich and Īch) is a village in Golabar Rural District, in the Central District of Ijrud County, Zanjan Province, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also ...

at this tyme asbut Village lyke". Soon after, in 1576, William Lambarde

William Lambarde (18 October 1536 – 19 August 1601) was an English antiquarian, writer on legal subjects, and politician. He is particularly remembered as the author of ''A Perambulation of Kent'' (1576), the first English county history; ''E ...

described Reculver as "poore and simple". In 1588 there were 165 communicants – people in Reculver parish taking part in services of holy communion at the church – and in 1640 there were 169, but a map of about 1630 shows that the church then stood only about from the shore. In January 1658 the local justices of the peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or ''puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission ( letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the sa ...

were petitioned concerning "encroachments of the sea ... hat hadsince Michaelmas last 9 September 1657encroached on the land near six rods ], and will doubtless do more harm". The village's failure to support two "beer shops" in the 1660s points clearly to a declining population, and the village was mostly abandoned around the end of the 18th century, its residents moving to Hillborough, about south-west of Reculver but within Reculver parish.

The decline of the settlement led to the decline of the church. In 1776 Thomas Philipot described it as "full of solitude, and languished into decay". In 1787 John Pridden noticed that the roofline of the nave must have been lowered at some time, judging by the tops of the east and west walls, and the fact that the tops of the two windows over the west door were at that time filled in with brick; he also noted that the roof had been repaired in 1775 by A. Sayer, churchwarden

A churchwarden is a lay official in a parish or congregation of the Anglican Communion or Catholic Church, usually working as a part-time volunteer. In the Anglican tradition, holders of these positions are ''ex officio'' members of the parish b ...

, these details appearing embossed on replacement lead. But he described the church as "a weather-beaten building ... mouldering away by the fury of the elements", and a letter to ''The Gentleman's Magazine

''The Gentleman's Magazine'' was a monthly magazine founded in London, England, by Edward Cave in January 1731. It ran uninterrupted for almost 200 years, until 1922. It was the first to use the term '' magazine'' (from the French ''magazine ...

'' in 1809 said that it was then somewhat dilapidated, with "trifling ... repairs such as have only tended to obliterate its once-harmonizing beauties."

Destruction

In the autumn of 1807 a northerly storm combined with a high tide to bring erosion of the cliff on which the church stood to within the churchyard, destroying "ten yards .1 mof the wall around the churchyard, not ten yards from the foundation of the church". Sea defences had been in place since at least 1783, but although they had been costly to build their design had led to further undermining of the cliff. Two further schemes were devised by Sir Thomas Page and John Rennie to preserve the cliff by means of new sea defences, Rennie's being estimated to cost £8,277. Instead, at avestry

A vestry was a committee for the local secular and ecclesiastical government for a parish in England, Wales and some English colonies which originally met in the vestry or sacristy of the parish church, and consequently became known colloquiall ...

meeting on 12 January 1808, and at the instigation of the vicar, Christopher Naylor, it was decided that the church should be demolished. The decision was reached by vote among eight of the leading residents of Reculver and Hoath, including the vicar: the votes were evenly split, so the vicar used his casting vote

A casting vote is a vote that someone may exercise to resolve a tied vote in a deliberative body. A casting vote is typically by the presiding officer of a council, legislative body, committee, etc., and may only be exercised to break a deadlock ...

in favour of demolition. Naylor applied to the Archbishop of Canterbury, Charles Manners-Sutton

Charles Manners-Sutton (17 February 1755 – 21 July 1828; called Charles Manners before 1762) was a bishop in the Church of England who served as Archbishop of Canterbury from 1805 to 1828.

Life

Manners-Sutton was the fourth son of Lord G ...

, for permission to demolish, arguing that "in all human probability the parishioners ould Ould is an English surname and an Arabic name ( ar, ولد). In some Arabic dialects, particularly Hassaniya Arabic, ولد (the patronymic, meaning "son of") is transliterated as Ould. Most Mauritanians have patronymic surnames.

Notable p ...

shortly be deprived of a place for the interment of their dead." The archbishop commissioned neighbouring clergy and landowners to assess the situation, and they reported in March 1809 that the church should be demolished "to save the materials for the erection of another church."

Demolition was begun in September 1809 using gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). Th ...

, in what has been described as "an act of vandalism for which there can be few parallels even in the blackest records of the nineteenth century":

The demolition of this "shrine of early Christendom", and

The demolition of this "shrine of early Christendom", and exemplar An exemplar is a person, a place, an object, or some other entity that serves as a predominant example of a given concept (e.g. "The heroine became an ''exemplar'' in courage to the children"). It may also refer to:

* Exemplar, a well-known scienc ...

of Anglo-Saxon church architecture and sculpture

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable ...

, was otherwise thorough, and it is now represented only by the ruins on the site, material incorporated into a replacement parish church at Hillborough,; fragments of the cross, and the two stone columns that had been part of the church's triple arch. The columns and fragments of the cross are on display in Canterbury Cathedral. Two thousand ton

Ton is the name of any one of several units of measure. It has a long history and has acquired several meanings and uses.

Mainly it describes units of weight. Confusion can arise because ''ton'' can mean

* the long ton, which is 2,240 pounds

...

s of stone from the demolished church were sold and incorporated into the harbour wall at Margate, known as Margate Pier, which was completed in 1815, and more than 40 tons of lead was stripped from the church and sold for £900. In 1810 Trinity House

"Three In One"

, formation =

, founding_location = Deptford, London, England

, status = Royal Charter corporation and registered charity

, purpose = Maintenance of lighthouses, buoys and beacons

, he ...

bought what was left of the structure from the parish for £100, to ensure that the towers were preserved as a navigational aid, and built the first groyne

A groyne (in the U.S. groin) is a rigid hydraulic structure built perpendicularly from an ocean shore (in coastal engineering) or a river bank, interrupting water flow and limiting the movement of sediment. It is usually made out of wood, concre ...

s, designed to protect the cliff on which the ruins stand. The spires had both been destroyed by storms by 1819, when Trinity House replaced them with similarly shaped, open structures, topped by wind vanes. These structures remained until they were removed some time after 1928. The ruins of the church, and the site of the Roman fort within which it was built, are now in the care of English Heritage, and the sea defences around Reculver are maintained by the Environment Agency.

Archaeology

The first archaeological report on the then demolished church of St Mary was published by George Dowker in 1878. He described finding the foundations of the apsidal chancel and of the columns that formed part of the triple chancel arch, and noted that the original floor of the church was of concrete, or ''

The first archaeological report on the then demolished church of St Mary was published by George Dowker in 1878. He described finding the foundations of the apsidal chancel and of the columns that formed part of the triple chancel arch, and noted that the original floor of the church was of concrete, or ''opus signinum

''Opus signinum'' ('cocciopesto' in modern Italian) is a building material used in ancient Rome. It is made of tiles broken up into very small pieces, mixed with mortar, and then beaten down with a rammer. Pliny the Elder in his '' Natural Histor ...

'', more than thick. The floor had previously been described in 1782, prior to the church's demolition, as polished smooth and finished in red, a sample having been taken with difficulty using a pickaxe. Within the floor Dowker also found what he believed was the foundation for the stone cross described by Leland, and noted that the concrete floor appeared to have been laid around it. The floor of the chancel appeared to have been raised by about when the chancel was extended in the Early English period, and had been covered with encaustic tile

Encaustic tiles are ceramic tiles in which the pattern or figure on the surface is not a product of the glaze but of different colors of clay. They are usually of two colours but a tile may be composed of as many as six. The pattern appears inla ...

s. Dowker also reported hearing from a Mr Holmans about the existence of a large, circular burial vault at the east end of the chancel, containing coffins arranged in a circle.

Further excavations were undertaken in the 1920s by C. R. Peers, who found that the nave of the original church had external doors on the north, south and west sides, and that the chancel had doors leading into the north and south porticus, which in turn had external doors on their eastern sides. Regarding the concrete floor described by Dowker, Peers noted that the surface consisted of a thin layer of pounded brick, and believed that it was of the same date as the stone that Dowker described as the foundation for the stone cross. Excavations also revealed steps leading down to the burial vault reported by Dowker, although Peers did not refer to either the steps or the vault in his report. Extensions of the porticus to the west and around the original west front were dated to no more than 100 years after the church was first built, and Peers observed that these extensions had been given the same type of floor as the original church. Drawing comparisons with the 7th-century chapel of St Peter-on-the-Wall

The Chapel of St Peter-on-the-Wall, Bradwell-on-Sea, is a Christian church dating from the years 660-662 and among the oldest largely intact churches in England. It is in regular use by the nearby Othona Community, in addition to Church of Engl ...

at Bradwell-on-Sea

Bradwell-on-Sea is a village and civil parish in Essex, England. The village is on the Dengie peninsula. It is located about north-northeast of Southminster and is east from the county town of Chelmsford. The village is in the District of Mal ...

, in Essex, and the abbey of St Augustine at Canterbury, Peers suggested that the original church at Reculver probably had windows set high in the northern and southern walls of the nave. Areas of wall found by archaeologists but now missing above ground are marked on the site by strips of concrete edged with flint.

The church was found to have been free-standing, so any other monastic buildings must have stood apart. In 1966, archaeologists discovered the foundations of what they identified as probably a medieval building, rectangular and on an east-west axis, with its eastern wall aligned with that of the church precinct, which it pre-dated. Extending over and in contact with the western end of a Roman bath house, it stood a few yards east of the south-eastern corner of the 13th-century chancel. This building was not recorded by William Boys, who drew a plan of the Roman fort and the church in 1781. Otherwise no such buildings have been found, but they may all have been in the area to the north of the church, which has been lost to the sea. In this connection Peers noted that the cloister

A cloister (from Latin ''claustrum'', "enclosure") is a covered walk, open gallery, or open arcade running along the walls of buildings and forming a quadrangle or garth. The attachment of a cloister to a cathedral or church, commonly against a ...

s of the early Canterbury churches of St Augustine's and Christ Church were both on their northern sides, and that St Augustine's had also been free-standing in the 7th century. A building that stood west-northwest of the church may have had an Anglo-Saxon doorway and the dimensions of an Anglo-Saxon church, and had "the appearance of having been part of some monastic erection". It was demolished after the sea weakened its foundations during storms in the winter of 1782. Leland reported another building outside the churchyard, where it was believed that a parish church had stood while the main church at Reculver was still a monastery: this building, formerly a chapel dedicated to St James, was later known as the "chapel-house", and stood in the north-eastern corner of the fort until it collapsed into the sea on 13 October 1802. Peers noted further that it seems to have had brick arches.

St John's Cathedral, Parramatta

The design of the twin towers, spires and west front of

The design of the twin towers, spires and west front of St John's Cathedral :''This list is for St. John the Evangelist Cathedrals. For St. John the Baptist Cathedrals, see St. John the Baptist Cathedral (disambiguation)''

St. John's Cathedral, St. John Cathedral, or Cathedral of St. John, or other variations on the name ...

, Parramatta

Parramatta () is a suburb and major Central business district, commercial centre in Greater Western Sydney, located in the state of New South Wales, Australia. It is located approximately west of the Sydney central business district on the ban ...

, in Sydney, Australia, which were added in 1817–1819, is based on those of St Mary's Church at Reculver. Efforts to save St Mary's Church were under way when Governor Lachlan Macquarie and his wife Elizabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sch ...

left England for Australia in 1809. Elizabeth Macquarie asked John Watts, the governor's aide-de-camp from 1814 to 1819, to design the towers for St John's Cathedral, and these, together with its west front, are the oldest remaining parts of an Anglican church in Australia, and are on the oldest site of continuous Christian worship there. In 1990 a stone from St Mary's Church was presented to St John's Cathedral by the Historic Building and Monuments Commission for England, now English Heritage.

References

Footnotes

Notes

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Saint Mary's Church, Reculver 7th-century church buildings in England Anglo-Saxon monastic houses Archaeological sites in Kent Church ruins in England Monasteries in Kent Buildings and structures demolished in 1809 Demolished churches in England Churches completed in 669