Abattoir on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

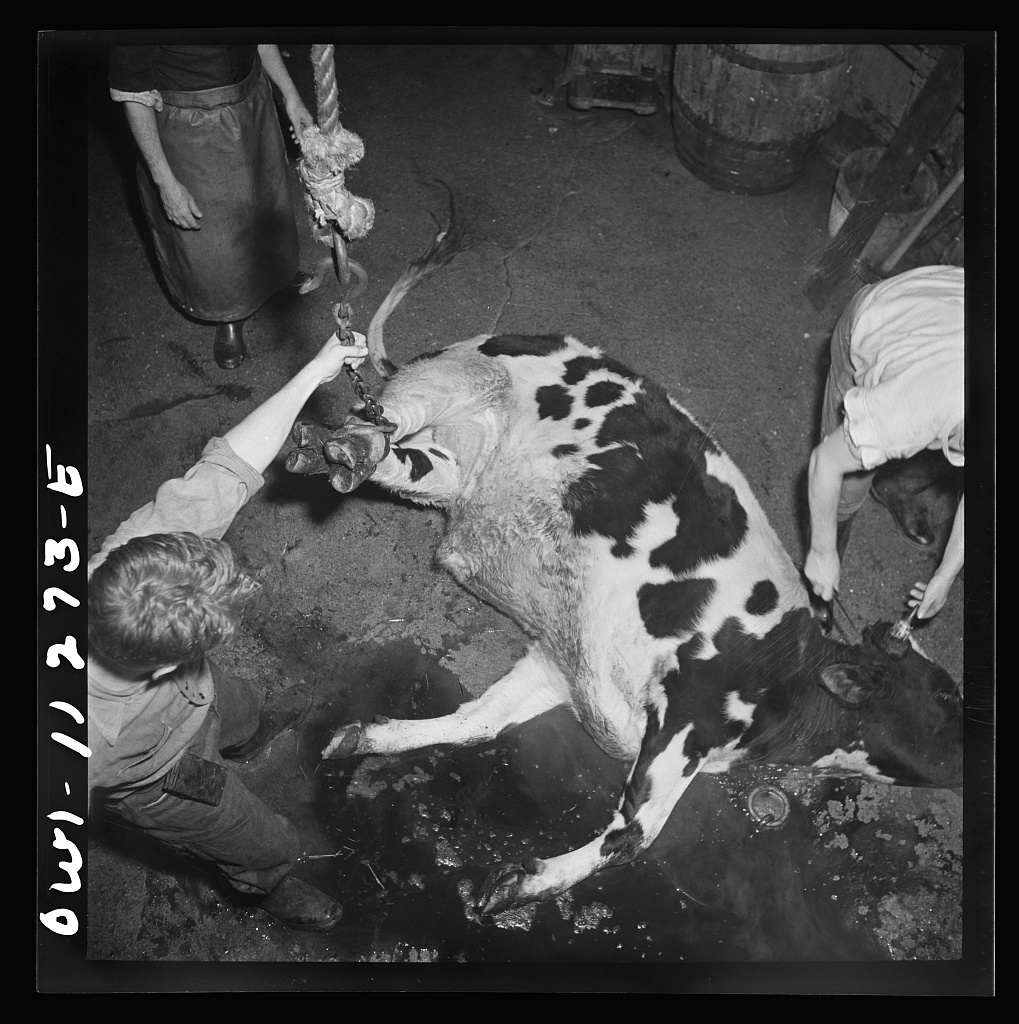

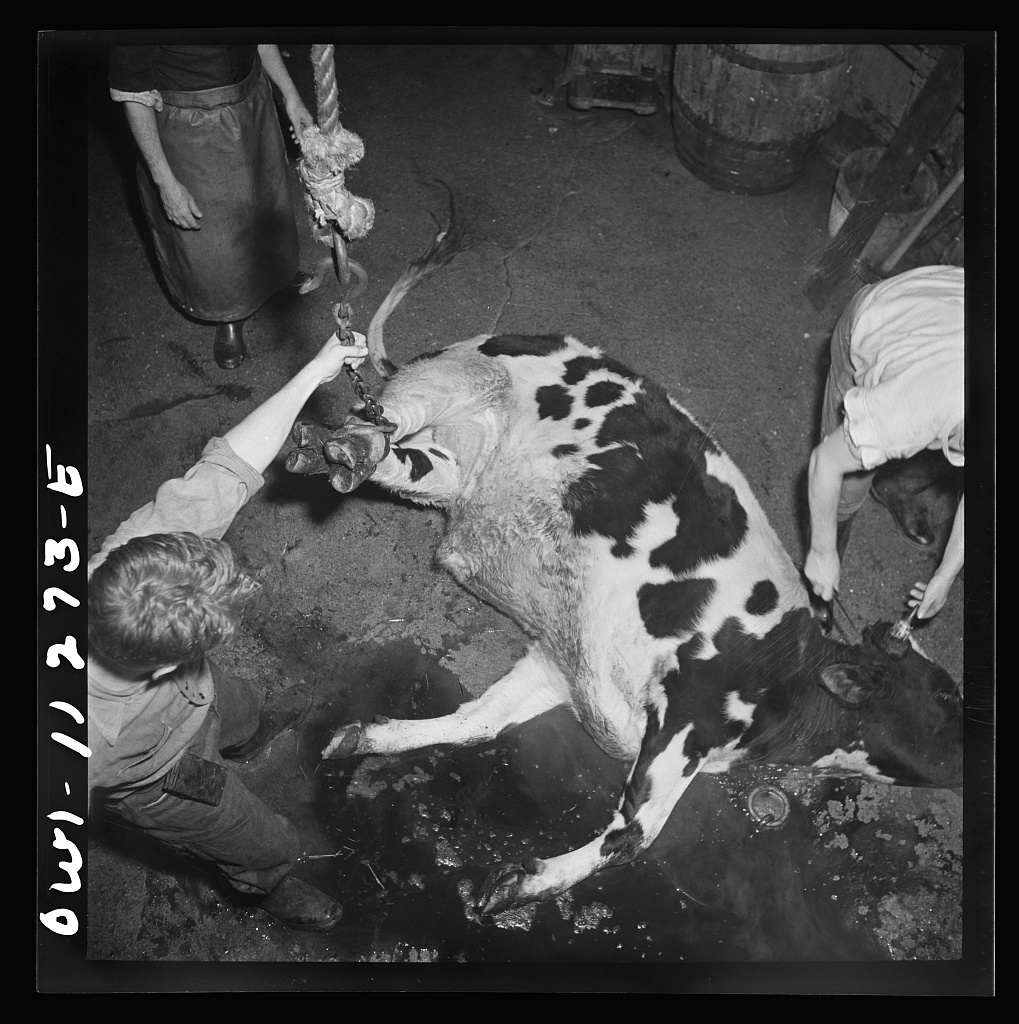

A slaughterhouse, also called abattoir (), is a facility where animals are slaughtered to provide food. Slaughterhouses supply meat, which then becomes the responsibility of a packaging facility.

Slaughterhouses that produce meat that is not intended for human consumption are sometimes referred to as ''knacker's yards'' or ''knackeries''. This is where animals are slaughtered that are not fit for human consumption or that can no longer work on a farm, such as retired work horses.

Slaughtering animals on a large scale poses significant issues in terms of logistics,

A slaughterhouse, also called abattoir (), is a facility where animals are slaughtered to provide food. Slaughterhouses supply meat, which then becomes the responsibility of a packaging facility.

Slaughterhouses that produce meat that is not intended for human consumption are sometimes referred to as ''knacker's yards'' or ''knackeries''. This is where animals are slaughtered that are not fit for human consumption or that can no longer work on a farm, such as retired work horses.

Slaughtering animals on a large scale poses significant issues in terms of logistics,

''Melbourne Abattoirs Act 1850'' (NSW)

"confined the slaughtering of animals to prescribed public abattoirs, while at the same time prohibiting the killing of sheep, lamb, pigs or goats at any other place within the city limits". Animals were shipped alive to British ports from Ireland, from Europe and from the colonies and slaughtered in large abattoirs at the ports. Conditions were often very poor. Attempts were also made throughout the British Empire to reform the practice of slaughter itself, as the methods used came under increasing criticism for causing undue pain to the animals. The eminent physician, Benjamin Ward Richardson, spent many years in developing more humane methods of slaughter. He brought into use no fewer than fourteen possible anesthetics for use in the slaughterhouse and even experimented with the use of electric current at the

In the latter part of the 20th century, the layout and design of most U.S. slaughterhouses was influenced by the work of

In the latter part of the 20th century, the layout and design of most U.S. slaughterhouses was influenced by the work of

The standards and regulations governing slaughterhouses vary considerably around the world. In many countries the slaughter of animals is regulated by custom and tradition rather than by law. In the non-Western world, including the

The standards and regulations governing slaughterhouses vary considerably around the world. In many countries the slaughter of animals is regulated by custom and tradition rather than by law. In the non-Western world, including the

, Humane Farming Association. Retrieved March 8, 2008. The HFA alleges that workers are required to kill up to 1,100 hogs an hour and end up taking their frustration out on the animals. Eisnitz interviewed one worker, who had worked in ten slaughterhouses, about pig production. He told her:

Slaughterhouse designer Temple Grandin's official site

detailing her design principles, as well as many of the regulations affecting slaughter in the United States.

Grandin's listing of various surveys, 1996–2011, US, Canada and Australia {{Authority control Livestock Animal rights Agricultural buildings Meat industry Slaughter methods

A slaughterhouse, also called abattoir (), is a facility where animals are slaughtered to provide food. Slaughterhouses supply meat, which then becomes the responsibility of a packaging facility.

Slaughterhouses that produce meat that is not intended for human consumption are sometimes referred to as ''knacker's yards'' or ''knackeries''. This is where animals are slaughtered that are not fit for human consumption or that can no longer work on a farm, such as retired work horses.

Slaughtering animals on a large scale poses significant issues in terms of logistics,

A slaughterhouse, also called abattoir (), is a facility where animals are slaughtered to provide food. Slaughterhouses supply meat, which then becomes the responsibility of a packaging facility.

Slaughterhouses that produce meat that is not intended for human consumption are sometimes referred to as ''knacker's yards'' or ''knackeries''. This is where animals are slaughtered that are not fit for human consumption or that can no longer work on a farm, such as retired work horses.

Slaughtering animals on a large scale poses significant issues in terms of logistics, animal welfare

Animal welfare is the well-being of non-human animals. Formal standards of animal welfare vary between contexts, but are debated mostly by animal welfare groups, legislators, and academics. Animal welfare science uses measures such as longevity ...

, and the environment, and the process must meet public health

Public health is "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private, communities and individuals". Analyzing the det ...

requirements. Due to public aversion in different cultures, determining where to build slaughterhouses is also a matter of some consideration.

Frequently, animal rights

Animal rights is the philosophy according to which many or all sentient animals have moral worth that is independent of their utility for humans, and that their most basic interests—such as avoiding suffering—should be afforded the sa ...

groups raise concerns about the methods of transport to and from slaughterhouses, preparation prior to slaughter, animal herding, and the killing itself.

History

Until modern times, the slaughter of animals generally took place in a haphazard and unregulated manner in diverse places. Early maps of London show numerous stockyards in the periphery of the city, where slaughter occurred in the open air or under cover such aswet markets

A wet market (also called a public market or a traditional market) is a marketplace selling fresh foods such as meat, fish as food, fish, greengrocer, produce and other consumption-oriented shelf life, perishable goods in a non-supermarket sett ...

. A term for such open-air slaughterhouses was ''shambles'', and there are streets named "The Shambles

The Shambles is a historic street in York, England, featuring preserved medieval buildings, some dating back as far as the fourteenth century. The street is narrow with many timber-framed buildings with jettied floors that overhang the street b ...

" in some English and Irish towns (e.g., Worcester

Worcester may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Worcester, England, a city and the county town of Worcestershire in England

** Worcester (UK Parliament constituency), an area represented by a Member of Parliament

* Worcester Park, London, Engla ...

, York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

, Bandon) which got their name from having been the site on which butchers killed and prepared animals for consumption. Fishamble Street

Fishamble Street (; ) is a street in Dublin, Ireland within the old city walls.

Location

The street joins Wood Quay at the Fish Slip near Fyan's Castle. It originally ran from Castle Street to Essex Quay until the creation of Lord Edward Stre ...

, Dublin was formerly a ''fish-shambles''. Sheffield had 183 slaughterhouses in 1910, and it was estimated that there were 20,000 in England and Wales.

Reform movement

The slaughterhouse emerged as a coherent institution in the 19th century. A combination of health and social concerns, exacerbated by the rapidurbanisation

Urbanization (or urbanisation) refers to the population shift from rural to urban areas, the corresponding decrease in the proportion of people living in rural areas, and the ways in which societies adapt to this change. It is predominantly the ...

experienced during the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

, led social reform

A reform movement or reformism is a type of social movement that aims to bring a social or also a political system closer to the community's ideal. A reform movement is distinguished from more radical social movements such as revolutionary move ...

ers to call for the isolation, sequester and regulation of animal slaughter. As well as the concerns raised regarding hygiene and disease, there were also criticisms of the practice on the grounds that the effect that killing had, both on the butchers and the observers, "educate the men in the practice of violence and cruelty, so that they seem to have no restraint on the use of it." An additional motivation for eliminating private slaughter was to impose a careful system of regulation for the "morally dangerous" task of putting animals to death.

As a result of this tension, meat markets within the city were closed and abattoirs built outside city limits. An early framework for the establishment of public slaughterhouses was put in place in Paris in 1810, under the reign of the Emperor Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

. Five areas were set aside on the outskirts of the city and the feudal privileges of the guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometimes ...

s were curtailed.

As the meat requirements of the growing number of residents in London steadily expanded,

the meat markets both within the city and beyond attracted increasing levels of public disapproval. Meat had been traded at Smithfield Market

Smithfield, properly known as West Smithfield, is a district located in Central London, part of Farringdon Without, the most westerly ward of the City of London, England.

Smithfield is home to a number of City institutions, such as St Bartho ...

as early as the 10th century. By 1726, it was regarded as "without question, the greatest in the world", by Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, trader, journalist, pamphleteer and spy. He is most famous for his novel ''Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its ...

. By the middle of the 19th century, in the course of a single year 220,000 head of cattle and 1,500,000 sheep would be "violently forced into an area of five acres, in the very heart of London, through its narrowest and most crowded thoroughfares".

By the early 19th century, pamphlets were being circulated arguing in favor of the removal of the livestock market and its relocation outside of the city due to the extremely low hygienic conditions as well as the brutal treatment of the cattle. In 1843, the ''Farmer's Magazine'' published a petition signed by bankers, salesmen, aldermen, butchers and local residents against the expansion of the livestock market. The Town Police Clauses Act 1847

The Town Police Clauses Act 1847 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom (10 & 11 Vict c. 89). The statute remains in force in both the United Kingdom (except Scotland) and the Republic of Ireland, and is frequently used by local coun ...

created a licensing and registration system, though few slaughter houses were closed.

An Act of Parliament

Acts of Parliament, sometimes referred to as primary legislation, are texts of law passed by the Legislature, legislative body of a jurisdiction (often a parliament or council). In most countries with a parliamentary system of government, acts of ...

was eventually passed in 1852. Under its provisions, a new cattle-market was constructed in Copenhagen Fields, Islington

Islington () is a district in the north of Greater London, England, and part of the London Borough of Islington. It is a mainly residential district of Inner London, extending from Islington's High Street to Highbury Fields, encompassing the ar ...

. The new Metropolitan Cattle Market

The Metropolitan Cattle Market (later Caledonian Market), just off the Caledonian Road in the parish of Islington (now the London Borough of Islington) was built by the City of London Corporation and was opened in June 1855 by Prince Albert. ...

was also opened in 1855, and West Smithfield was left as waste ground for about a decade, until the construction of the new market began in the 1860s under the authority of the 1860 Metropolitan Meat and Poultry Market Act. The market was designed by architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

Sir Horace Jones and was completed in 1868.

A cut and cover

A tunnel is an underground passageway, dug through surrounding soil, earth or rock, and enclosed except for the entrance and exit, commonly at each end. A pipeline is not a tunnel, though some recent tunnels have used immersed tube cons ...

railway tunnel was constructed beneath the market to create a triangular junction with the railway between Blackfriars Blackfriars, derived from Black Friars, a common name for the Dominican Order of friars, may refer to:

England

* Blackfriars, Bristol, a former priory in Bristol

* Blackfriars, Canterbury, a former monastery in Kent

* Blackfriars, Gloucester, a f ...

and King's Cross. This allowed animals to be transported into the slaughterhouse by train and the subsequent transfer of animal carcasses to the Cold Store building, or direct to the meat market via lifts.

At the same time, the first large and centralized slaughterhouse in Paris was constructed in 1867 under the orders of Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

at the Parc de la Villette

The Parc de la Villette is the third-largest park in Paris, in area, located at the northeastern edge of the city in the 19th arrondissement. The park houses one of the largest concentrations of cultural venues in Paris, including the Cité de ...

and heavily influenced the subsequent development of the institution throughout Europe.

Regulation and expansion

These slaughterhouses were regulated by law to ensure good standards of hygiene, the prevention of the spread of disease and the minimization of needless animal cruelty. The slaughterhouse had to be equipped with a specialized water supply system to effectively clean the operating area of blood and offal. Veterinary scientists, notably George Fleming and John Gamgee, campaigned for stringent levels of inspection to ensure that epizootics such asrinderpest

Rinderpest (also cattle plague or steppe murrain) was an infectious viral disease of cattle, domestic buffalo, and many other species of even-toed ungulates, including gaurs, buffaloes, large antelope, deer, giraffes, wildebeests, and warthogs ...

(a devastating outbreak of the disease covered all of Britain in 1865) would not be able to spread. By 1874, three meat inspectors were appointed for the London area, and the Public Health Act 1875 required local authorities to provide central slaughterhouses (they were only given powers to close unsanitary slaughterhouses in 1890). Yet the appointment of slaughterhouse inspectors and the establishment of centralised abattoirs took place much earlier in the British colonies, such as the colonies of New South Wales and Victoria, and in Scotland where 80% of cattle were slaughtered in public abattoirs by 1930. In Victoria th''Melbourne Abattoirs Act 1850'' (NSW)

"confined the slaughtering of animals to prescribed public abattoirs, while at the same time prohibiting the killing of sheep, lamb, pigs or goats at any other place within the city limits". Animals were shipped alive to British ports from Ireland, from Europe and from the colonies and slaughtered in large abattoirs at the ports. Conditions were often very poor. Attempts were also made throughout the British Empire to reform the practice of slaughter itself, as the methods used came under increasing criticism for causing undue pain to the animals. The eminent physician, Benjamin Ward Richardson, spent many years in developing more humane methods of slaughter. He brought into use no fewer than fourteen possible anesthetics for use in the slaughterhouse and even experimented with the use of electric current at the

Royal Polytechnic Institution

, mottoeng = The Lord is our Strength

, type = Public

, established = 1838: Royal Polytechnic Institution 1891: Polytechnic-Regent Street 1970: Polytechnic of Central London 1992: University of Westminster

, endowment = £5.1 million ...

. As early as 1853, he designed a lethal chamber that would gas animals to death relatively painlessly, and he founded the Model Abattoir Society in 1882 to investigate and campaign for humane methods of slaughter.

The invention of refrigeration

The term refrigeration refers to the process of removing heat from an enclosed space or substance for the purpose of lowering the temperature.International Dictionary of Refrigeration, http://dictionary.iifiir.org/search.phpASHRAE Terminology, ht ...

and the expansion of transportation networks by sea and rail allowed for the safe exportation of meat around the world. Additionally, meat-packing millionaire Philip Danforth Armour

Philip Danforth Armour Sr. (16 May 1832 – 6 January 1901) was an American meatpacking industrialist who founded the Chicago-based firm of Armour & Company. Born on an upstate New York farm, he made $8,000 in the California gold rush, 185 ...

's invention of the "disassembly line" greatly increased the productivity and profit margin of the meat packing industry

The meat-packing industry (also spelled meatpacking industry or meat packing industry) handles the slaughtering, processing, packaging, and distribution of meat from animals such as cattle, pigs, sheep and other livestock. Poultry is generally no ...

: "according to some, animal slaughtering became the first mass-production

Mass production, also known as flow production or continuous production, is the production of substantial amounts of standardized products in a constant flow, including and especially on assembly lines. Together with job production and bat ...

industry in the United States." This expansion has been accompanied by increased concern about the physical and mental conditions of the workers along with controversy over the ethical and environmental implications of slaughtering animals for meat.

The Edinburgh abattoir, which was built in 1910, had well lit laboratories, hot and cold water, gas, microscopes and equipment for cultivating organisms. The English 1924 Public Health (Meat) Regulations required notification of slaughter to enable inspection of carcasses and enabled inspected carcasses to be marked.

The development of slaughterhouses was linked with industrial expansion of by-products. By 1932 the British by-product industry was worth about £97 million a year, employing 310,000 people. The Aberdeen slaughterhouse sent hooves to Lancashire to make glue, intestines to Glasgow for sausages and hides to the Midland tanneries.

In January 1940 the British government took over the 16,000 slaughterhouses and by 1942 there were only 779.

Design

In the latter part of the 20th century, the layout and design of most U.S. slaughterhouses was influenced by the work of

In the latter part of the 20th century, the layout and design of most U.S. slaughterhouses was influenced by the work of Temple Grandin

Mary Temple Grandin (born August 29, 1947) is an American academic and animal behaviorist. She is a prominent proponent for the humane treatment of livestock for slaughter and the author of more than 60 scientific papers on animal behavior. Gra ...

. She suggested that reducing the stress of animals being led to slaughter may help slaughterhouse operators improve efficiency and profit. In particular she applied an understanding of animal psychology

Comparative psychology refers to the scientific study of the behavior and mental processes of non-human animals, especially as these relate to the phylogenetic history, adaptive significance, and development of behavior. Research in this area addr ...

to design pens

A pen is a common writing instrument that applies ink to a surface, usually paper, for writing or drawing. Early pens such as reed pens, quill pens, dip pens and ruling pens held a small amount of ink on a nib or in a small void or cavity whi ...

and corral

A pen is an enclosure for holding livestock. It may also perhaps be used as a term for an enclosure for other animals such as pets that are unwanted inside the house. The term describes types of enclosures that may confine one or many animal ...

s which funnel a herd of animals arriving at a slaughterhouse into a single file ready for slaughter. Her corrals employ long sweeping curves Why does a curved chute and round crowd pen work better than a straight one? As the animals go around the curve, they think they are going back to where they came from. The animals can not see people and other moving objects at the end of the chute. It takes advantage of the natural circling behaviour of cattle and sheep. Some of the design principles that are taught are the use of solid sides on chutes and crowd pens to prevent animals from seeing out with their wide-angle vision and layout of curved chutes and round crowd pens. Some people believe the animals can smell or hear death, however, and these may be area that need improvement, such as the use of scent masking agents or acoustical barriers. As well, some animals in some situations may grow to learn that after their fellows are corralled in that area, their fellows never return. An improvement could be made by detouring off some of the animals so that they return to the pack (after the odors and sounds are masked so they will return untraumatized). A circular crowd pen and a curved chute reduced the time spent moving cattle by up to 50% (Vowles and Hollier, 1982 owles, W. J., and T. J. Hollier. 1982. The influence of yard design on the movement of animals. Proc. Aust. Soc. Anim. Prod. 14:597. so that each animal is prevented from seeing what lies ahead and just concentrates on the hind quarters of the animal in front of it. This design – along with the design elements of solid sides, solid crowd gate, and reduced noise at the end point – work together to encourage animals forward in the chute and to not reverse direction. Cattle will move more easily through a curved race.

Solid sides which prevent the cattle from seeing people and other distractions outside the fence should be installed on the chutes (races) and the crowd pen which leads up to the single file chute. The use of solid sides is especially important in slaughter plants, truck loading ramps, and other places where there is much activity outside the fence. Solid sides are essential in slaughter plants to block the animal's view of people and equipment.

A curved chute (race) with solid sides at a ranch facility. It works better than a straight chute because cattle think they are going back to where they came from. The outer fence is solid to prevent the cattle from seeing distractions outside the fence... The facility must be located in a pasture that has no nearby equipment, moving vehicles or extra people, or put inside a building that has solid side walls. In many facilities, adding solid fences will improve animal movement...

Solid sides in these areas help prevent cattle from becoming agitated when they see activity outside the fence – such as people. Cattle tend to be calmer in a chute with solid sides.

Cattle move more easily through the curved race system because they can not see people and other distractions ahead.Mobile design

Beginning in 2008 the Local Infrastructure for Local Agriculture, a non-profit committed to revitalizing opportunities for "small farmers and strengthening the connection between local supply and demand", constructed a mobile slaughterhouse facility in efforts for small farmers to process meat quickly and cost effectively. Named the Modular Harvest System, or M.H.S., it receivedUSDA

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is the federal executive department responsible for developing and executing federal laws related to farming, forestry, rural economic development, and food. It aims to meet the needs of com ...

approval in 2010. The M.H.S. consists of three separate trailers: One for slaughtering, one for consumable body parts, and one for other body parts. Preparation of individual cuts is done at a butchery or other meat preparation facility.

International variations

Arab world

The Arab world ( ar, اَلْعَالَمُ الْعَرَبِيُّ '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, refers to a vast group of countries, mainly located in Western A ...

, the Indian sub-continent, etc., both forms of meat are available: one which is produced in modern mechanized slaughterhouses, and the other from local butcher

A butcher is a person who may Animal slaughter, slaughter animals, dress their flesh, sell their meat, or participate within any combination of these three tasks. They may prepare standard cuts of meat and poultry for sale in retail or wholesal ...

shops.

In some communities animal slaughter and permitted species may be controlled by religious law

Religious law includes ethical and moral codes taught by religious traditions. Different religious systems hold sacred law in a greater or lesser degree of importance to their belief systems, with some being explicitly antinomian whereas others ...

s, most notably ''halal

''Halal'' (; ar, حلال, ) is an Arabic word that translates to "permissible" in English. In the Quran, the word ''halal'' is contrasted with ''haram'' (forbidden). This binary opposition was elaborated into a more complex classification kno ...

'' for Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

s and ''kashrut'' for Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""Th ...

ish communities. This can cause conflicts with national regulations when a slaughterhouse adhering to the rules of religious preparation is located in some Western countries

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania.

. In Jewish law, captive bolts and other methods of pre-slaughter paralysis are generally not permissible, due to it being forbidden for an animal to be stunned prior to slaughter. Various halal food authorities have more recently permitted the use of a recently developed fail-safe system of head-only stunning where the shock is non-fatal, and where it is possible to reverse the procedure and revive the animal after the shock. The use of electronarcosis

Electronarcosis, also called electric stunning or electrostunning, is a profound stupor produced by passing an electric current through the brain. Electronarcosis may be used as a form of electrotherapy in treating certain mental illnesses in hu ...

and other methods of dulling the sensing has been approved by the Egyptian Fatwa Committee. This allows these entities to continue their religious techniques while keeping accordance to the national regulations.

In some societies, traditional cultural and religious aversion to slaughter led to prejudice against the people involved. In Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

, where the ban on slaughter of livestock for food was lifted in the late 19th century, the newly found slaughter industry drew workers primarily from villages of ''burakumin

is a name for a low-status social group in Japan. It is a term for ethnic Japanese people with occupations considered as being associated with , such as executioners, undertakers, slaughterhouse workers, butchers, or tanners.

During Japan's ...

'', who traditionally worked in occupations relating to death (such as executioners and undertakers). In some parts of western Japan, prejudice faced by current and former residents of such areas (''burakumin'' "hamlet people") is still a sensitive issue. Because of this, even the Japanese word for "slaughter" (屠殺 ''tosatsu'') is deemed politically incorrect

''Political correctness'' (adjectivally: ''politically correct''; commonly abbreviated ''PC'') is a term used to describe language, policies, or measures that are intended to avoid offense or disadvantage to members of particular groups in socie ...

by some pressure group

Advocacy groups, also known as interest groups, special interest groups, lobbying groups or pressure groups use various forms of advocacy in order to influence public opinion and ultimately policy. They play an important role in the develop ...

s as its inclusion of the kanji

are the logographic Chinese characters taken from the Chinese family of scripts, Chinese script and used in the writing of Japanese language, Japanese. They were made a major part of the Japanese writing system during the time of Old Japanese ...

for "kill" (殺) supposedly portrays those who practice it in a negative manner.

Some countries have laws that exclude specific animal species or grades of animal from being slaughtered for human consumption, especially those that are taboo food

Some people do not eat various specific foods and beverages in conformity with various religious, cultural, legal or other societal prohibitions. Many of these prohibitions constitute taboos. Many food taboos and other prohibitions forbid the mea ...

. The former Indian Prime Minister

The prime minister of India (IAST: ) is the head of government of the Republic of India. Executive authority is vested in the prime minister and their chosen Council of Ministers, despite the president of India being the nominal head of the ...

Atal Bihari Vajpayee

Atal Bihari Vajpayee (; 25 December 1924 – 16 August 2018) was an Indian politician who served three terms as the 10th prime minister of India, first for a term of 13 days in 1996, then for a period of 13 months fr ...

suggested in 2004 introducing legislation banning the slaughter of cows throughout India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, as Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

holds cows as sacred and considers their slaughter unthinkable and offensive. This was often opposed on grounds of religious freedom. The slaughter of cows and the importation of beef into the nation of Nepal

Nepal (; ne, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mai ...

are strictly forbidden.

Freezing works

Refrigeration technology allowed meat from the slaughterhouse to be preserved for longer periods. This led to the concept as the slaughterhouse as a freezing works. Prior to this, canning was an option. Freezing works are common in New Zealand, Australia and South Africa. In countries where meat is exported for a substantial profit the freezing works were built near docks, or near transport infrastructure. Mobile poultry processing units (MPPUs) follow the same principles, but typically require only one trailer and, in much of the United States, may legally operate under USDA exemptions not available to red meat processors. Several MPPUs have been in operation since before 2010, under various models of operation and ownership.Law

Most countries have laws in regard to the treatment of animals in slaughterhouses. In theUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, there is the Humane Slaughter Act

The Humane Slaughter Act, or the Humane Methods of Livestock Slaughter Act (P.L. 85-765; 7 U.S.C. 1901 et seq.), is a United States federal law designed to decrease suffering of livestock during slaughter. It was approved on August 27, 1958. T ...

of 1958, a law requiring that all swine, sheep, cattle, and horses be stunned unconscious with application of a stunning device by a trained person before being hoisted up on the line. There is some debate over the enforcement of this act. This act, like those in many countries, exempts slaughter in accordance to religious law, such as kosher

(also or , ) is a set of dietary laws dealing with the foods that Jewish people are permitted to eat and how those foods must be prepared according to Jewish law. Food that may be consumed is deemed kosher ( in English, yi, כּשר), fro ...

shechita

In Judaism, ''shechita'' (anglicized: ; he, ; ; also transliterated ''shehitah, shechitah, shehita'') is slaughtering of certain mammals and birds for food according to ''kashrut''.

Sources

states that sheep and cattle should be slaughtered ...

and dhabiha halal. Most strict interpretations of kashrut require that the animal be fully sensible when its carotid artery Carotid artery may refer to:

* Common carotid artery, often "carotids" or "carotid", an artery on each side of the neck which divides into the external carotid artery and internal carotid artery

* External carotid artery, an artery on each side of t ...

is cut.

The novel ''The Jungle

''The Jungle'' is a 1906 novel by the American journalist and novelist Upton Sinclair. Sinclair's primary purpose in describing the meat industry and its working conditions was to advance socialism in the United States. However, most readers we ...

'' presented a fictionalized account of unsanitary conditions in slaughterhouses and the meatpacking industry during the 1800s. This led directly to an investigation commissioned directly by President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

, and to the passage of the Meat Inspection Act

The Federal Meat Inspection Act of 1906 (FMIA) is an American law that makes it illegal to adulterate or misbrand meat and meat products being sold as food, and ensures that meat and meat products are slaughtered and processed under strictly r ...

and the Pure Food and Drug Act

The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, also known as Dr. Wiley's Law, was the first of a series of significant consumer protection laws which was enacted by Congress in the 20th century and led to the creation of the Food and Drug Administration. ...

of 1906, which established the Food and Drug Administration

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a List of United States federal agencies, federal agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is respon ...

. A much larger body of regulation deals with the public health and worker safety regulation and inspection.

Animal welfare concerns

In 1997, Gail Eisnitz, chief investigator for the Humane Farming Association (HFA), released the book ''Slaughterhouse''. Within, she unveils the interviews of slaughterhouse workers in the U.S. who say that, because of the speed with which they are required to work, animals are routinely skinned while apparently alive and still blinking, kicking and shrieking. Eisnitz argues that this is not only cruel to the animals but also dangerous for the human workers, as cows weighing several thousands of pounds thrashing around in pain are likely to kick out and debilitate anyone working near them. This would imply that certain slaughterhouses throughout the country are not following the guidelines and regulations spelled out by the ''Humane Slaughter Act

The Humane Slaughter Act, or the Humane Methods of Livestock Slaughter Act (P.L. 85-765; 7 U.S.C. 1901 et seq.), is a United States federal law designed to decrease suffering of livestock during slaughter. It was approved on August 27, 1958. T ...

'', requiring all animals to be put down and thus insusceptible to pain by some form, typically electronarcosis, before undergoing any form of violent action.

According to the HFA, Eiznitz interviewed slaughterhouse workers representing over two million hours of experience, who, without exception, told her that they have beaten, strangled, boiled and dismembered animals alive or have failed to report those who do. The workers described the effects the violence has had on their personal lives, with several admitting to being physically abusive or taking to alcohol and other drugs."HFA Exposé Uncovers Federal Crimes", Humane Farming Association. Retrieved March 8, 2008. The HFA alleges that workers are required to kill up to 1,100 hogs an hour and end up taking their frustration out on the animals. Eisnitz interviewed one worker, who had worked in ten slaughterhouses, about pig production. He told her:

Animal rights activists

The animal rights (AR) movement, sometimes called the animal liberation, animal personhood, or animal advocacy movement, is a social movement that seeks an end to the rigid moral and legal distinction drawn between human and non-human animals, ...

, anti-speciesists, vegetarians

Vegetarianism is the practice of abstaining from the consumption of meat (red meat, poultry, seafood, insects, and the flesh of any other animal). It may also include abstaining from eating all by-products of animal slaughter.

Vegetarianism ma ...

and vegans

Veganism is the practice of abstaining from the use of animal product—particularly in diet—and an associated philosophy that rejects the commodity status of animals. An individual who follows the diet or philosophy is known as a vegan. D ...

are prominent critics of slaughterhouses and have created events such as the march to close all slaughterhouses to voice concerns about the conditions in slaughterhouses and ask for their abolition. Some have argued that humane animal slaughter is impossible.

Worker exploitation concerns

American slaughterhouse workers are three times more likely to suffer serious injury than the average American worker.NPR

National Public Radio (NPR, stylized in all lowercase) is an American privately and state funded nonprofit media organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., with its NPR West headquarters in Culver City, California. It differs from other ...

reports that pig and cattle slaughterhouse workers are nearly seven times more likely to suffer repetitive strain injuries than average. ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' reports that on average there are two amputations a week involving slaughterhouse workers in the United States. On average, one employee of Tyson Foods

Tyson Foods, Inc. is an American multinational corporation, based in Springdale, Arkansas, that operates in the food industry. The company is the world's second-largest processor and marketer of chicken, beef, and pork after JBS S.A. It annually ...

, the largest meat producer in America, is injured and amputates a finger or limb per month. The Bureau of Investigative Journalism reported that over a period of six years, in the UK 78 slaughter workers lost fingers, parts of fingers or limbs, more than 800 workers had serious injuries, and at least 4,500 had to take more than three days off after accidents. In a 2018 study in the Italian Journal of Food Safety, slaughterhouse workers are instructed to wear ear protectors to protect their hearing from the loud noises in the facility. A 2004 study in the ''Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine'' found that "excess risks were observed for mortality from all causes, all cancers, and lung cancer" in workers employed in the New Zealand meat processing industry.

Working at slaughterhouses often leads to a high amount of psychological trauma. A 2016 study in ''Organization'' indicates, "Regression analyses of data from 10,605 Danish workers across 44 occupations suggest that slaughterhouse workers consistently experience lower physical and psychological well-being along with increased incidences of negative coping behavior." In her thesis submitted to and approved by University of Colorado, Anna Dorovskikh states that slaughterhouse workers are "at risk of Perpetration-Inducted Traumatic Stress, which is a form of posttraumatic stress disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental and behavioral disorder that can develop because of exposure to a traumatic event, such as sexual assault, warfare, traffic collisions, child abuse, domestic violence, or other threats on ...

and results from situations where the concerning subject suffering from PTSD was a causal participant in creating the traumatic situation." A 2009 study by criminologist Amy Fitzgerald indicates, "slaughterhouse employment increases total arrest rates, arrests for violent crimes, arrests for rape, and arrests for other sex offenses in comparison with other industries." As authors from the PTSD Journal explain, "These employees are hired to kill animals, such as pigs and cows that are largely gentle creatures. Carrying out this action requires workers to disconnect from what they are doing and from the creature standing before them. This emotional dissonance can lead to consequences such as domestic violence, social withdrawal, anxiety, drug and alcohol abuse, and PTSD."

Starting in the 1980s, Cargill

Cargill, Incorporated, is a privately held American global food corporation based in Minnetonka, Minnesota, and incorporated in Wilmington, Delaware. Founded in 1865, it is the largest privately held corporation in the United States in ter ...

, Conagra Brands

Conagra Brands, Inc. (formerly ConAgra Foods) is an American Fast-moving consumer goods, consumer packaged goods holding company headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. Conagra makes and sells products under various brand names that are available in ...

, Tyson Foods and other large food companies moved most slaughterhouse operations to rural areas of the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

which were more hostile to unionization efforts. Slaughterhouses in the United States commonly illegally employ and exploit underage workers and illegal immigrants. In 2010, Human Rights Watch

Human Rights Watch (HRW) is an international non-governmental organization, headquartered in New York City, that conducts research and advocacy on human rights. The group pressures governments, policy makers, companies, and individual human r ...

described slaughterhouse line work in the United States as a human rights crime. In a report by Oxfam America

Oxfam is a British-founded confederation of 21 independent charitable organizations focusing on the alleviation of global poverty, founded in 1942 and led by Oxfam International.

History

Founded at 17 Broad Street, Oxford, as the Oxford Co ...

, slaughterhouse workers were observed not being allowed breaks, were often required to wear diapers, and were paid below minimum wage.

See also

* Animal–industrial complex *Continuous inspection

Continuous inspection (carcass-by-carcass inspection) is the USDA’s meat and poultry

Poultry () are domesticated birds kept by humans for their eggs, their meat or their feathers. These birds are most typically members of the superord ...

* Controlled-atmosphere killing

Inert gas asphyxiation is a form of asphyxiation which results from breathing a physiologically inert gas in the absence of oxygen, or a hypoxia (medical), low amount of oxygen, rather than atmospheric air (which is composed largely of nitrogen and ...

(CAK)

* Cultured meat

Cultured meat (also known by other names) is meat produced by culturing animal cells ''in vitro''. It is a form of cellular agriculture.

Cultured meat is produced using tissue engineering techniques pioneered in regenerative medicine. Jason M ...

* Dog meat

Dog meat is the flesh and other edible parts derived from dogs. Historically, human consumption of dog meat has been recorded in many parts of the world. During the 19th century westward movement in the United States, ''mountainmen'', native ...

* Meat cutter

A meat cutter prepares primal cuts into a variety of smaller cuts intended for sale in a retail environment. The duties of a meat cutter largely overlap those of the butcher, but butchers tend to specialize in pre-sale processing (reducing carcas ...

* Meat processing

The meat-packing industry (also spelled meatpacking industry or meat packing industry) handles the slaughtering, processing, packaging, and distribution of meat from animals such as cattle, pigs, sheep and other livestock. Poultry is generally no ...

* Pig slaughter

Pig slaughter is the work of slaughtering domestic pigs which is both a common economic activity as well as a traditional feast in some European and Asian countries.

Agriculture

Pig slaughter is an activity performed to obtain pig meat (pork). ...

* Pig scalder

A pig scalder is a tool that was used to soften the skin of a pig after it had been killed to remove the hair from its skin. Because people rarely slaughter and process their own pigs anymore, pig scalders are seldom used for domestic use.

Moder ...

* Weasand clip

References

External links

*Slaughterhouse designer Temple Grandin's official site

detailing her design principles, as well as many of the regulations affecting slaughter in the United States.

Grandin's listing of various surveys, 1996–2011, US, Canada and Australia {{Authority control Livestock Animal rights Agricultural buildings Meat industry Slaughter methods