A Child of Our Time on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''A Child of Our Time'' is a secular

''A Child of Our Time'' is a secular

Having found his subject, Tippett sought advice on the preparation of the text from T. S. Eliot, whom he had met recently through a mutual friend, Francis Morley.Tippett 1994, pp. 50–51 The musicologist Michael Steinberg comments that, given his anti-Semitism, Eliot may have been an inappropriate choice of collaborator, though Tippett considered the poet his spiritual and artistic mentor, and felt that his counsel would be crucial. Tippett writes: "I plucked up courage and asked him if he would write it. Eliot said he would consider the matter as long as I provided him with a precise scheme of musical sections and an exact indication of the numbers and kinds of words for each stage". When Tippett produced his detailed draft, Eliot advised the composer to write his own libretto, suggesting that his own superior poetry would either distract attention from the music, or otherwise would be "swallowed up by it". Either way, there would be a mismatch. Tippett accepted this advice; henceforth, he records, he always wrote his own texts.

Tippett resolved that his work would be an

Having found his subject, Tippett sought advice on the preparation of the text from T. S. Eliot, whom he had met recently through a mutual friend, Francis Morley.Tippett 1994, pp. 50–51 The musicologist Michael Steinberg comments that, given his anti-Semitism, Eliot may have been an inappropriate choice of collaborator, though Tippett considered the poet his spiritual and artistic mentor, and felt that his counsel would be crucial. Tippett writes: "I plucked up courage and asked him if he would write it. Eliot said he would consider the matter as long as I provided him with a precise scheme of musical sections and an exact indication of the numbers and kinds of words for each stage". When Tippett produced his detailed draft, Eliot advised the composer to write his own libretto, suggesting that his own superior poetry would either distract attention from the music, or otherwise would be "swallowed up by it". Either way, there would be a mismatch. Tippett accepted this advice; henceforth, he records, he always wrote his own texts.

Tippett resolved that his work would be an

Chorus: "A star rises in midwinter"

# The Narrator (bass solo): "And a time came"

# Double Chorus of Persecutors and Persecuted: "Away with them!"

# The Narrator (bass solo): "Where they could, they fled"

# Chorus of the Self-righteous: "We cannot have them in our Empire"

# The Narrator (bass solo): "And the boy's mother wrote"

# Scena: The Mother (soprano), the Uncle and Aunt (bass and alto), and the Boy (tenor): "O my son!"

# A Spiritual (chorus and soli): " Nobody knows the trouble I see"

# Scena: Duet (bass and alto): "The boy becomes desperate"

# The Narrator (bass solo): "They took a terrible vengeance"

# Chorus: The Terror: "Burn down their houses!"

# The Narrator (bass solo): "Men were ashamed"

# A Spiritual of Anger (chorus and bass solo): " Go down, Moses"

# The Boy Sings in his Prison (tenor solo): "My dreams are all shattered"

# The Mother (soprano solo): "What have I done to you, my son?"

# Alto solo: "The dark forces rise"

# A Spiritual (chorus and soprano solo): "O by and by"

Part III

# Chorus: "The cold deepens"

# Alto solo: "The soul of man"

# Scena (bass solo and chorus): "The words of wisdom"

# General Ensemble (chorus and soli): "I would know my shadow and my light"

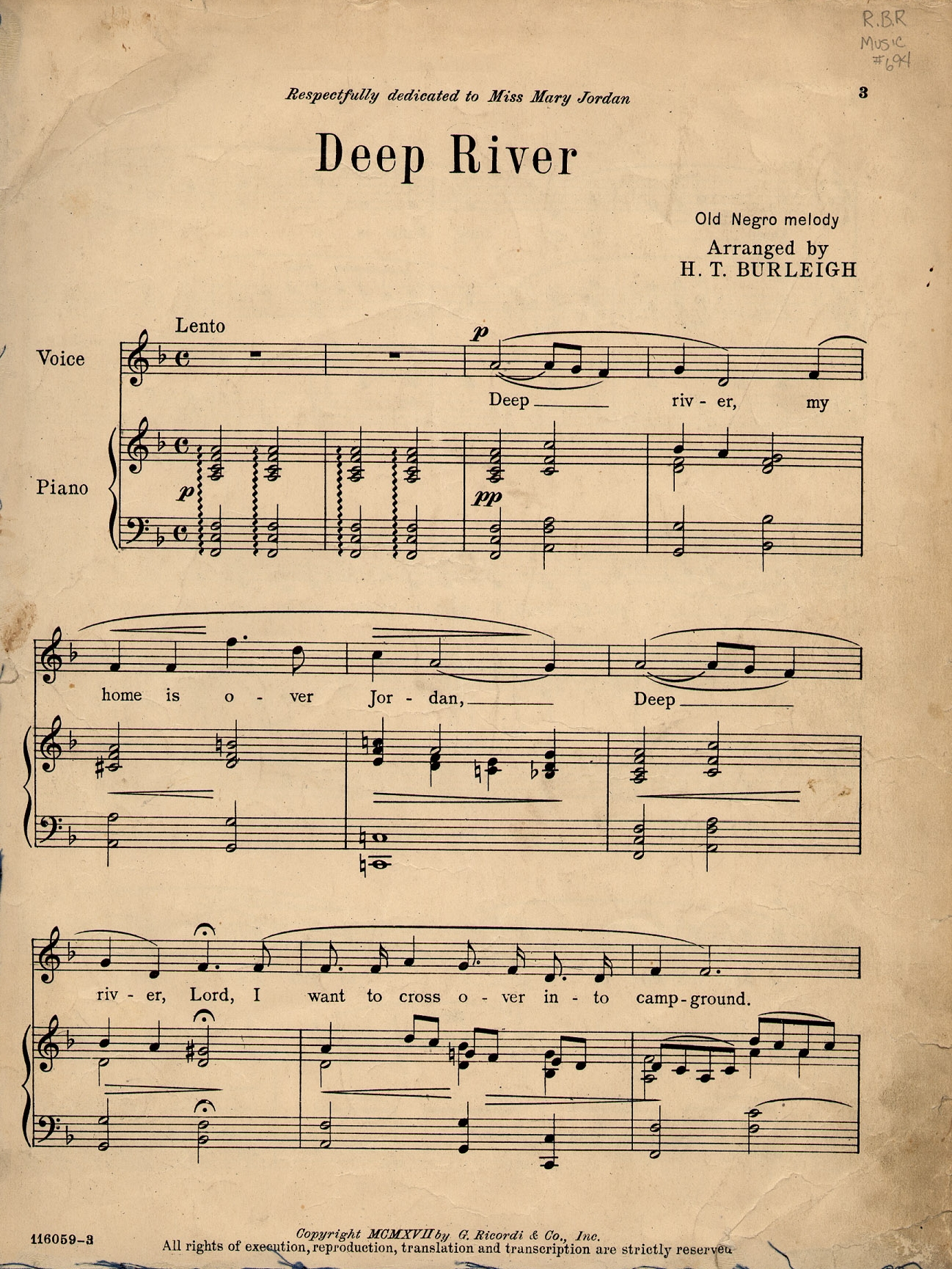

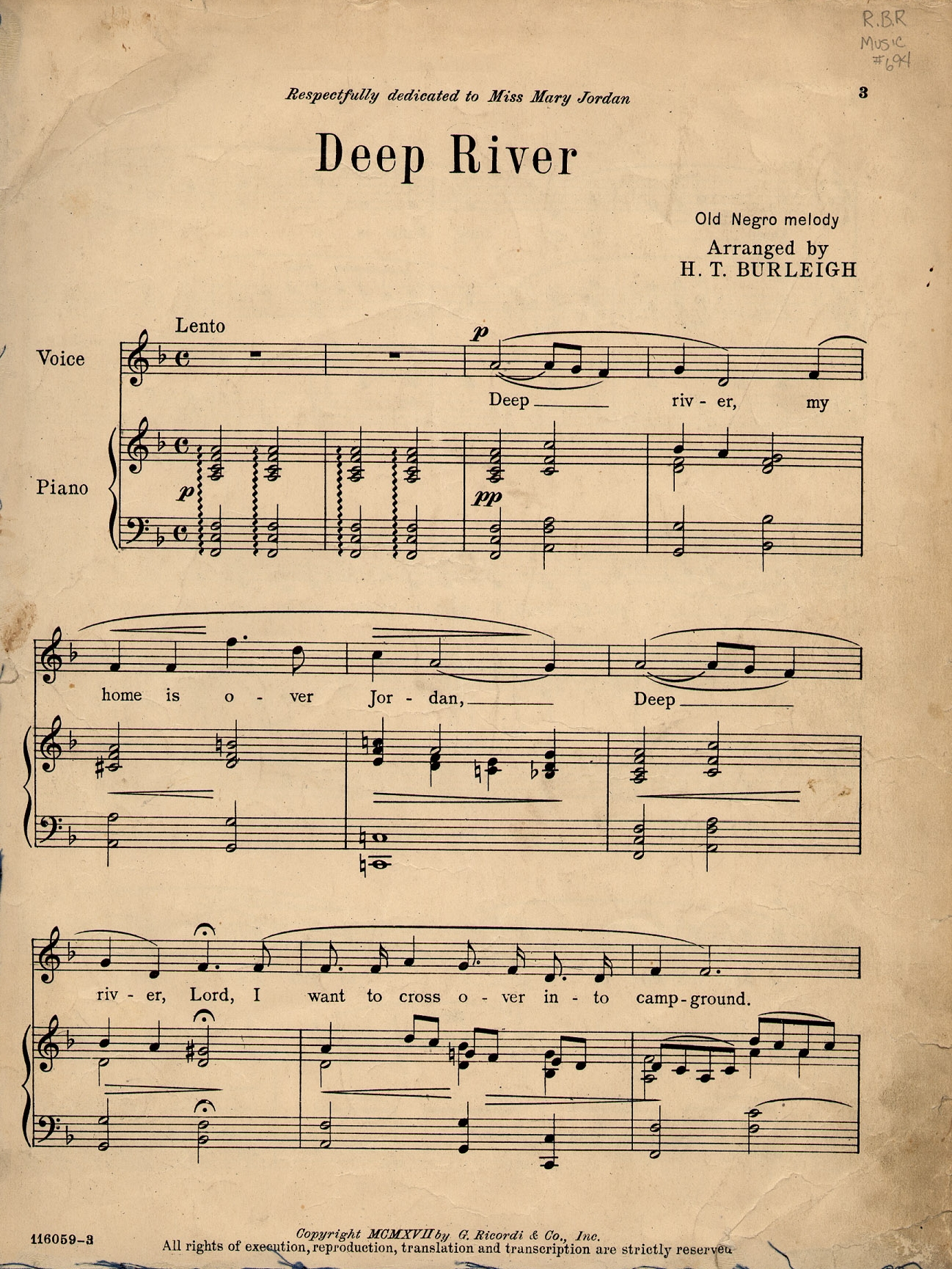

# A Spiritual (chorus and soli): " Deep river"

's director of music, to arrange a broadcast performance of the work. This took place on 10 January 1945 shortly after which, in February, Tippett conducted the work at the

Kemp describes Tippett's central problem in composing ''A Child of Our Time'' as integrating the language of the spirituals with his own musical style. Tippett was, in Kemp's view, entirely successful in this respect; "O by and by", he says, sounds as if it could almost have been composed by Tippett. To assist the process of integration the composer had obtained recordings of American singing groups, especially the Hall Johnson Choir, which provided him with a three-part model for determining the relationships between solo voices and chorus in the spirituals: chorus, soloists, chorus.Kemp, p. 172 Tippett's instructions in the score specify that "the spirituals should not be thought of as congregational hymns, but as integral parts of the Oratorio; nor should they be sentimentalised but sung with a strong underlying beat and slightly 'swung'".

The brief orchestral prelude to Part I introduces the two contrasting moods which pervade the entire work. Kemp likens the opening "snarling trumpet triad" to "a descent into Hades", but it is answered immediately by a gently mournful phrase in the strings. In general the eight numbers which comprise this first part each have, says Gloag, their own distinct texture and harmonic identity, often in a disjunctive relationship with each other, although the second and third numbers are connected by an orchestral "interludium". From among the diverse musical features Steinberg draws attention to rhythms in the chorus "When Shall The Usurer's City Cease" that illustrate Tippett's knowledge of and feel for the English

Kemp describes Tippett's central problem in composing ''A Child of Our Time'' as integrating the language of the spirituals with his own musical style. Tippett was, in Kemp's view, entirely successful in this respect; "O by and by", he says, sounds as if it could almost have been composed by Tippett. To assist the process of integration the composer had obtained recordings of American singing groups, especially the Hall Johnson Choir, which provided him with a three-part model for determining the relationships between solo voices and chorus in the spirituals: chorus, soloists, chorus.Kemp, p. 172 Tippett's instructions in the score specify that "the spirituals should not be thought of as congregational hymns, but as integral parts of the Oratorio; nor should they be sentimentalised but sung with a strong underlying beat and slightly 'swung'".

The brief orchestral prelude to Part I introduces the two contrasting moods which pervade the entire work. Kemp likens the opening "snarling trumpet triad" to "a descent into Hades", but it is answered immediately by a gently mournful phrase in the strings. In general the eight numbers which comprise this first part each have, says Gloag, their own distinct texture and harmonic identity, often in a disjunctive relationship with each other, although the second and third numbers are connected by an orchestral "interludium". From among the diverse musical features Steinberg draws attention to rhythms in the chorus "When Shall The Usurer's City Cease" that illustrate Tippett's knowledge of and feel for the English

Libretto (on pp. 10–11)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Child Of Our Time, A 1941 compositions Compositions by Michael Tippett Kristallnacht Works about the Holocaust Oratorios

''A Child of Our Time'' is a secular

''A Child of Our Time'' is a secular oratorio

An oratorio () is a large musical composition for orchestra, choir, and soloists. Like most operas, an oratorio includes the use of a choir, soloists, an instrumental ensemble, various distinguishable characters, and arias. However, opera is mus ...

by the British composer Michael Tippett

Sir Michael Kemp Tippett (2 January 1905 – 8 January 1998) was an English composer who rose to prominence during and immediately after the Second World War. In his lifetime he was sometimes ranked with his contemporary Benjamin Britten ...

(1905–1998), who also wrote the libretto

A libretto (Italian for "booklet") is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or Musical theatre, musical. The term ''libretto'' is also sometimes used to refer to the t ...

. Composed between 1939 and 1941, it was first performed at the Adelphi Theatre

The Adelphi Theatre is a West End theatre, located on the Strand in the City of Westminster, central London. The present building is the fourth on the site. The theatre has specialised in comedy and musical theatre, and today it is a receiv ...

, London, on 19 March 1944. The work was inspired by events that affected Tippett profoundly: the assassination in 1938 of a German diplomat by a young Jewish refugee, and the Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

government's reaction in the form of a violent pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russia ...

against its Jewish population: Kristallnacht

() or the Night of Broken Glass, also called the November pogrom(s) (german: Novemberpogrome, ), was a pogrom against Jews carried out by the Nazi Party's (SA) paramilitary and (SS) paramilitary forces along with some participation from ...

. Tippett's oratorio deals with these incidents in the context of the experiences of oppressed people generally, and carries a strongly pacifist message of ultimate understanding and reconciliation. The text's recurrent themes of shadow and light reflect the Jungian

Analytical psychology ( de , Analytische Psychologie, sometimes translated as analytic psychology and referred to as Jungian analysis) is a term coined by Carl Jung, a Swiss psychiatrist, to describe research into his new "empirical science" ...

psychoanalysis which Tippett underwent in the years immediately before writing the work.

The oratorio uses a traditional three-part format based on that of Handel's ''Messiah'', and is structured in the manner of Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the '' Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suites; keyboard w ...

's Passions. The work's most original feature is Tippett's use of African-American spirituals

Spirituals (also known as Negro spirituals, African American spirituals, Black spirituals, or spiritual music) is a genre of Christian music that is associated with Black Americans, which merged sub-Saharan African cultural heritage with the e ...

, which carry out the role allocated by Bach to chorale

Chorale is the name of several related musical forms originating in the music genre of the Lutheran chorale:

* Hymn tune of a Lutheran hymn (e.g. the melody of "Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme"), or a tune in a similar format (e.g. one of the t ...

s. Tippett justified this innovation on the grounds that these songs of oppression possess a universality absent from traditional hymns. ''A Child of Our Time'' was well received on its first performance, and has since been performed all over the world in many languages. A number of recorded versions are available, including one conducted by Tippett when he was 86 years old.

Background and conception

Michael Tippett

Sir Michael Kemp Tippett (2 January 1905 – 8 January 1998) was an English composer who rose to prominence during and immediately after the Second World War. In his lifetime he was sometimes ranked with his contemporary Benjamin Britten ...

was born in London in 1905, to well-to-do though unconventional parents. His father, a lawyer and businessman, was a freethinker

Freethought (sometimes spelled free thought) is an epistemological viewpoint which holds that beliefs should not be formed on the basis of authority, tradition, revelation, or dogma, and that beliefs should instead be reached by other methods ...

, his mother a writer and suffragette

A suffragette was a member of an activist women's organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner "Votes for Women", fought for the right to vote in public elections in the United Kingdom. The term refers in particular to members ...

. He received piano lessons as a child, but first showed his musical prowess while a pupil at Stamford School in Lincolnshire, between 1920 and 1922. Although the school's formal music curriculum was slight, Tippett received private piano tuition from Frances Tinkler, a noted local teacher whose most distinguished pupil had been Malcolm Sargent

Sir Harold Malcolm Watts Sargent (29 April 1895 – 3 October 1967) was an English conductor, organist and composer widely regarded as Britain's leading conductor of choral works. The musical ensembles with which he was associated include ...

, himself a former pupil at Stamford. Tippett's chance purchase in a local bookshop of Stanford

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is considere ...

's book ''Musical Composition'' led to his determination to be a composer, and in April 1923 he was accepted as a student at the Royal College of Music

The Royal College of Music is a music school, conservatoire established by royal charter in 1882, located in South Kensington, London, UK. It offers training from the Undergraduate education, undergraduate to the Doctorate, doctoral level in a ...

(RCM). Here he studied composition, first under Charles Wood (who died in 1926) and later, less successfully, with Charles Kitson. He also studied conducting, first under Sargent and later under Adrian Boult

Sir Adrian Cedric Boult, CH (; 8 April 1889 – 22 February 1983) was an English conductor. Brought up in a prosperous mercantile family, he followed musical studies in England and at Leipzig, Germany, with early conducting work in London ...

. He left the RCM in December 1928, but after two years spent unsuccessfully attempting to launch his career as a composer, he returned to the college in 1930 for a further period of study, principally under the professor of counterpoint

In music, counterpoint is the relationship between two or more musical lines (or voices) which are harmonically interdependent yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. It has been most commonly identified in the European classical tradi ...

, R. O. Morris.

In the economically depressed 1930s Tippett adopted a strongly left-wing political stance, and became increasingly involved with the unemployed, both through his participation in the North Yorkshire work camps, and as founder of the South London Orchestra made up of out-of-work musicians. He was briefly a member of the British Communist Party

The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was the largest communist organisation in Britain and was founded in 1920 through a merger of several smaller Marxist groups. Many miners joined the CPGB in the 1926 general strike. In 1930, the CPGB ...

in 1935, but his sympathies were essentially Trotskyist

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a rev ...

, inimical to the Stalinist

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist-Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the theory o ...

orientation of his local party, and he soon left. In 1935 he embraced pacifism, but by this time he was becoming overtaken by a range of emotional problems and uncertainties, largely triggered by the break-up of an intense relationship with the painter Wilfred Franks. In addition to these personal difficulties he became anxious that the political situation in Europe was leading inexorably towards war. After meeting the Jungian psychoanalyst John Layard

John Willoughby Layard (27 November 1891 – 26 November 1974) was an English anthropologist and psychologist.

Early life

Layard was born in London, son of the essayist and literary writer George Somes Layard and his wife Eleanor. He grew up ...

, Tippett underwent a period of therapy which included self-analysis of his dreams. According to Tippett's biographer Geraint Lewis, the outcome of this process was a "rebirth, confirming for Tippett the nature of his homosexuality while ... strengthening his destiny as a creative artist at the possible expense of personal relationships". The encounter with Layard led Tippett to a lifelong interest in the work and teaching of Carl Jung

Carl Gustav Jung ( ; ; 26 July 1875 – 6 June 1961) was a Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who founded analytical psychology. Jung's work has been influential in the fields of psychiatry, anthropology, archaeology, literature, philo ...

, an influence carried through into many of his subsequent compositions.

In the mid-to-late 1930s several of Tippett's early works were published, including his String Quartet No. 1, Sonata No. 1 for piano, and Concerto for Double String Orchestra. Among his unpublished output in these years were two works for voice: the ballad opera The ballad opera is a genre of English stage entertainment that originated in the early 18th century, and continued to develop over the following century and later. Like the earlier '' comédie en vaudeville'' and the later ''Singspiel'', its dist ...

''Robin Hood

Robin Hood is a legendary heroic outlaw originally depicted in English folklore and subsequently featured in literature and film. According to legend, he was a highly skilled archer and swordsman. In some versions of the legend, he is depic ...

'', written for performance at the Yorkshire work camps, and ''A Song of Liberty'' based on William Blake

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his life, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual art of the Romantic Age. ...

's "The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

''The Marriage of Heaven and Hell'' is a book by the English poet and printmaker William Blake. It is a series of texts written in imitation of biblical prophecy but expressing Blake's own intensely personal Romantic and revolutionary beliefs ...

". As his self-confidence increased, Tippett felt increasingly driven to write a work of overt political protest. In his search for a subject he first considered the Dublin Easter Rising

The Easter Rising ( ga, Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the a ...

of 1916: he may have been aware that Benjamin Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten (22 November 1913 – 4 December 1976, aged 63) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, other ...

had written incidental music to Montagu Slater

Charles Montagu Slater (23 September 1902 – 19 December 1956) was an English poet, novelist, playwright, journalist, critic and librettist.

Life

One of five children, Slater was born in the small mining port of Millom, Cumberland facing L ...

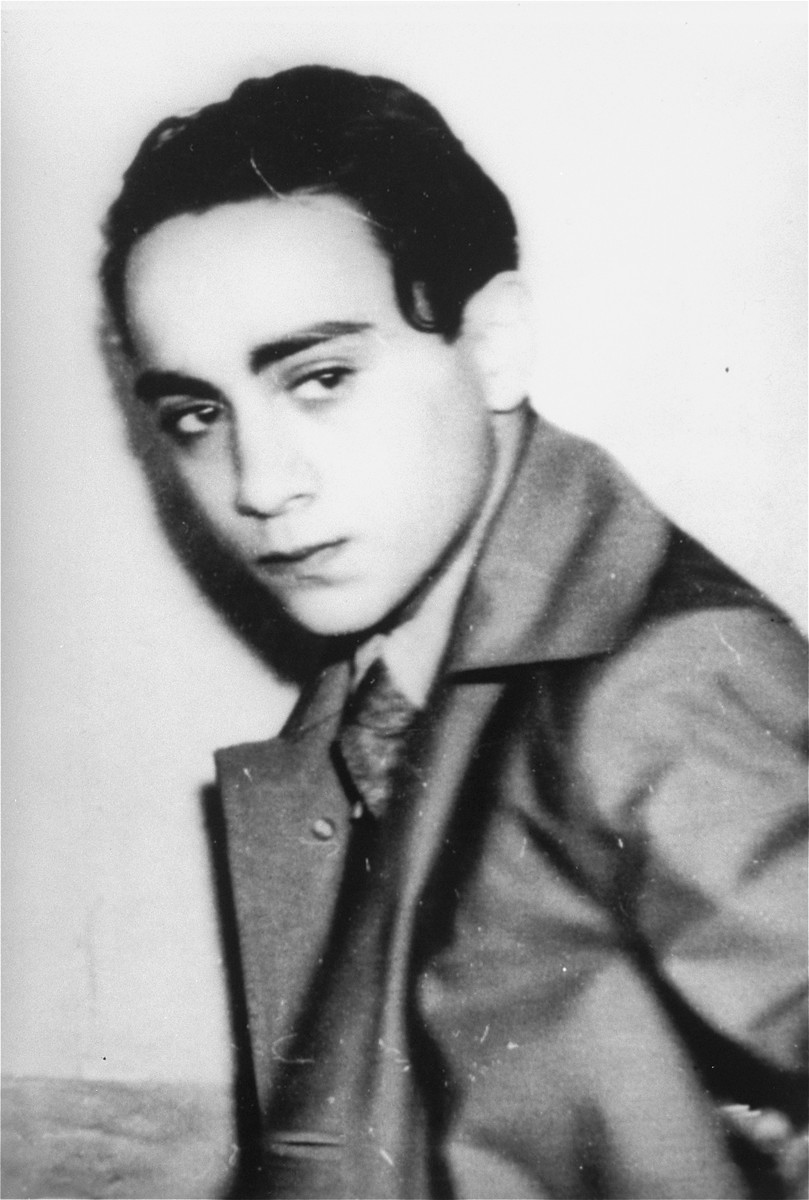

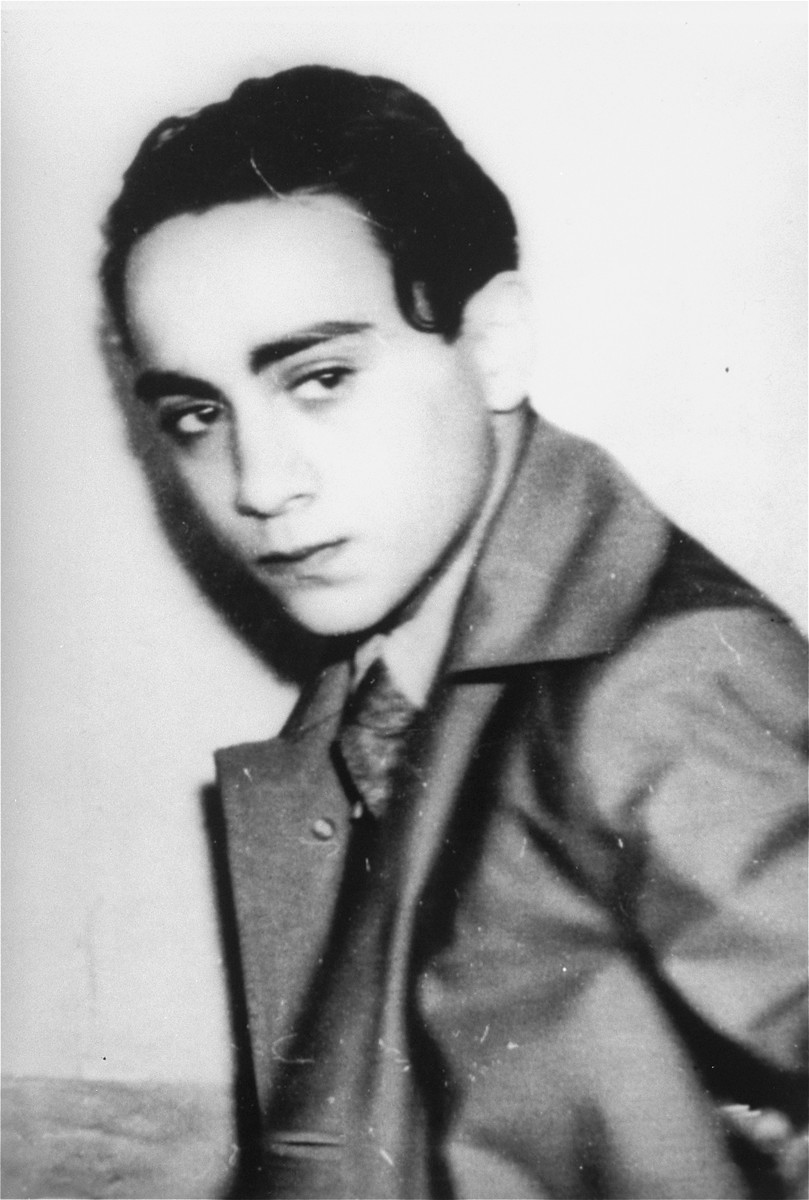

's play ''Easter 1916''. However, events towards the end of 1938 turned his attention away from Irish matters.Whittall, p. 71 Tippett had made several visits to Germany, and had acquired a love for its literature and culture. He became increasingly distressed by reports of events in that country and, in particular the persecution of its Jewish population.Steinberg, pp. 284–85 In November 1938 the assassination in Paris of a German diplomat, Ernst vom Rath

Ernst Eduard vom Rath (3 June 1909 – 9 November 1938) was a member of the German nobility, a Nazi Party member, and German Foreign Office diplomat. He is mainly remembered for his assassination in Paris in 1938 by a Polish Jews, Jewish teena ...

, by Herschel Grynszpan

Herschel Feibel Grynszpan (Yiddish: הערשל פײַבל גרינשפּאן; German: ''Hermann Grünspan''; 28 March 1921 – last rumoured to be alive 1945, declared dead 1960) was a Polish-Jewish expatriate born and raised in Weimar Germany ...

, a 17-year-old Jewish refugee, precipitated the "Kristallnacht

() or the Night of Broken Glass, also called the November pogrom(s) (german: Novemberpogrome, ), was a pogrom against Jews carried out by the Nazi Party's (SA) paramilitary and (SS) paramilitary forces along with some participation from ...

" pogrom across Germany. Over several days of violence synagogues were burned, Jewish homes and businesses attacked and destroyed, thousands of Jews were arrested, and some Jews were stoned or beaten to death. Reports from Germany of these events affected Tippett profoundly, and became the inspiration for his first large-scale dramatic work.

Creation

Libretto

Having found his subject, Tippett sought advice on the preparation of the text from T. S. Eliot, whom he had met recently through a mutual friend, Francis Morley.Tippett 1994, pp. 50–51 The musicologist Michael Steinberg comments that, given his anti-Semitism, Eliot may have been an inappropriate choice of collaborator, though Tippett considered the poet his spiritual and artistic mentor, and felt that his counsel would be crucial. Tippett writes: "I plucked up courage and asked him if he would write it. Eliot said he would consider the matter as long as I provided him with a precise scheme of musical sections and an exact indication of the numbers and kinds of words for each stage". When Tippett produced his detailed draft, Eliot advised the composer to write his own libretto, suggesting that his own superior poetry would either distract attention from the music, or otherwise would be "swallowed up by it". Either way, there would be a mismatch. Tippett accepted this advice; henceforth, he records, he always wrote his own texts.

Tippett resolved that his work would be an

Having found his subject, Tippett sought advice on the preparation of the text from T. S. Eliot, whom he had met recently through a mutual friend, Francis Morley.Tippett 1994, pp. 50–51 The musicologist Michael Steinberg comments that, given his anti-Semitism, Eliot may have been an inappropriate choice of collaborator, though Tippett considered the poet his spiritual and artistic mentor, and felt that his counsel would be crucial. Tippett writes: "I plucked up courage and asked him if he would write it. Eliot said he would consider the matter as long as I provided him with a precise scheme of musical sections and an exact indication of the numbers and kinds of words for each stage". When Tippett produced his detailed draft, Eliot advised the composer to write his own libretto, suggesting that his own superior poetry would either distract attention from the music, or otherwise would be "swallowed up by it". Either way, there would be a mismatch. Tippett accepted this advice; henceforth, he records, he always wrote his own texts.

Tippett resolved that his work would be an oratorio

An oratorio () is a large musical composition for orchestra, choir, and soloists. Like most operas, an oratorio includes the use of a choir, soloists, an instrumental ensemble, various distinguishable characters, and arias. However, opera is mus ...

rather than an opera

Opera is a form of theatre in which music is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by singers. Such a "work" (the literal translation of the Italian word "opera") is typically a collaboration between a composer and a librett ...

. He chose the title from ', a contemporary protest novel by the Austro-Hungarian writer, Ödön von Horváth

Edmund Josef von Horváth (9 December 1901, Sušak, Rijeka, Austria-Hungary – 1 June 1938, Paris France) was an Austro-Hungarian playwright and novelist who wrote in German, and went by the name of ''nom de guerre'' Ödön von Horváth. He was ...

. The text that Tippett prepared follows the three-part structure used in Handel's ''Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of ''mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach'' ...

'', in which Part I is prophetic and preparatory, Part II narrative and epic, Part III meditative and metaphysical. In ''A Child of Our Time'' the general condition of oppression is defined in the first part, the narrative elements are confined to the second part, while the third part contains interpretation and reflection on a possible healing.Kemp, p. 157 Tippett perceived the work as a general depiction of man's inhumanity to man, and wanted Grynszpan's tragedy to stand for the oppressed everywhere. To preserve the universality of the work, Tippett avoids all use of proper names for people and places: thus, Paris is "a great city", Grynszpan becomes "the boy", the soprano

A soprano () is a type of classical female singing voice and has the highest vocal range of all voice types. The soprano's vocal range (using scientific pitch notation) is from approximately middle C (C4) = 261 Hz to "high A" (A5) = 880&n ...

is "the boy's mother", vom Rath is "the official". In addition to the broad themes of human oppression, Tippett's personal devastation at the end of his relationship with Wilfred Franks is woven into the libretto. At the time Tippett was writing the text, he was consumed by the break-up with Franks and felt "unable to come to terms with either the wretchedness of the separation or the emotional turmoil it let loose." As Tippett sought healing from his pain, Franks became a prominent figure in his Jungian dream analysis uring the first half of 1939 and the composer explained the image of Franks's shining face "appeared transformed in the alto aria in Part 3 of A Child of Our Time."

Commentators have identified numerous works as textual influences, including Eliot's ''Murder in the Cathedral

''Murder in the Cathedral'' is a verse drama by T. S. Eliot, first performed in 1935, that portrays the assassination of Archbishop Thomas Becket in Canterbury Cathedral during the reign of Henry II in 1170. Eliot drew heavily on the writin ...

'' and ''Ash Wednesday

Ash Wednesday is a holy day of prayer and fasting in many Western Christian denominations. It is preceded by Shrove Tuesday and falls on the first day of Lent (the six weeks of penitence before Easter). It is observed by Catholics in the Rom ...

'', Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as treat ...

's ''Faust

Faust is the protagonist of a classic German legend based on the historical Johann Georg Faust ( 1480–1540).

The erudite Faust is highly successful yet dissatisfied with his life, which leads him to make a pact with the Devil at a crossroads ...

'' and Wilfred Owen

Wilfred Edward Salter Owen MC (18 March 1893 – 4 November 1918) was an English poet and soldier. He was one of the leading poets of the First World War. His war poetry on the horrors of trenches and gas warfare was much influenced by ...

's poem "The Seed". Tippett's biographer Ian Kemp equates the ending of the oratorio to the closing pages of Part I of John Bunyan

John Bunyan (; baptised 30 November 162831 August 1688) was an English writer and Puritan preacher best remembered as the author of the Christian allegory ''The Pilgrim's Progress,'' which also became an influential literary model. In addition ...

's ''Pilgrim's Progress

''The Pilgrim's Progress from This World, to That Which Is to Come'' is a 1678 Christianity, Christian allegory written by John Bunyan. It is regarded as one of the most significant works of theological fiction in English literature and a prog ...

'', in which Christian and Hopeful end their journey by crossing a deep and wide river to reach their heavenly home. The influence of Jungian themes is evident in the recurrent images of darkness and light, and the recognition and balancing of opposites.Steinberg, p. 286 In a recent analysis of the work, Richard Rodda finds ''A Child of Our Time'' "rooted in the essential dialectic of human life that Tippett so prized in Jung's philosophy—winter/spring, darkness/light, evil/good, reason/pity, dreams/reality, loneliness/fellowship, the man of destiny/the child of our time".

Composition

Tippett completed his Jungian psychoanalysis on 31 August 1939. Three days later, on the day that Britain declared war on Germany, he began composing ''A Child of Our Time''. His grounding in the traditions of European music guided him instinctively towards the Passions ofBach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the '' Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suites; keyboard w ...

as his basic musical model. Thus the building blocks of the work are familiar: recitatives, arias, choruses and ensembles, with a male soloist acting as a narrator and the chorus as full participants in the action. Tippett also introduced two other formal number types: the operatic scena and the orchestral interlude, the latter allowing time for reflection on significant events. Tippett wished to punctuate his work with an equivalent to the congregation chorales which recur in Bach's Passions; however, he wanted his work to speak to atheists, agnostics and Jews as well as to Christians. He considered briefly whether folk-songs, or even Jewish hymns, could provide an alternative, but rejected these because he felt that, like the chorales, they lacked universality. A solution was suggested to him when he heard on the radio a rendering of the spiritual "Steal away

"Steal Away" ("Steal Away to Jesus") is an American Negro spiritual. The song is well known by variations of the chorus:

Songs such as "Steal Away to Jesus", "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot", "Wade in the Water" and the " Gospel Train" are songs with ...

". In particular he was struck by the power of the words "The trumpet sounds within-a my soul". This led him to recognise spirituals as carrying an emotional significance far beyond their origin as slave songs in 19th-century America and as representing the oppressed everywhere.

Having found his substitute for the chorales, Tippett wrote off to America for a collection of spirituals. When this arrived, "I saw that there was one for every key situation in the oratorio". He chose five: "Steal Away

"Steal Away" ("Steal Away to Jesus") is an American Negro spiritual. The song is well known by variations of the chorus:

Songs such as "Steal Away to Jesus", "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot", "Wade in the Water" and the " Gospel Train" are songs with ...

"; "Nobody Knows the Trouble I See, Lord"; "Go Down, Moses"; "O, By and By"; and "Deep River". The first, fourth and fifth of these are placed at the ends of the oratorio's three parts, "Deep River" as the finale expressing, according to Tippett, the hope of a fresh spring after a long, dark winter. Kenneth Gloag, in his detailed analysis of the oratorio, writes: "As well as constructing the pathway through the dramatic narrative, the five spirituals also combine to provide moments of focus and repose ... giving shape to both the musical and literary dimensions of the work". Tippett felt that the work encapsulated all his current political, moral and psychological preoccupations.

Synopsis and structure

According to Tippett's description, "Part I of the work deals with the general state of oppression in our time. Part II presents the particular story of a young man's attempt to seek justice by violence and the catastrophic consequences; and Part III considers the moral to be drawn, if any." He later extended his summary to the following: *Part I: The general state of affairs in the world today as it affects all individuals, minorities, classes or races that are felt to be outside the ruling conventions. Man at odds with his Shadow (i.e. the dark side of personality). *Part II: The "Child of Our Time" appears, enmeshed in the drama of his personal fate and the elemental social forces of our day. The drama is because the forces which drive the young man prove stronger than the good advice of his uncle and aunt, as it always was and always will be. *Part III: The significance of this drama and the possible healing that would come from Man's acceptance of his Shadow in relation to his Light. Part I # Chorus: "The world turns on its dark side" # The Argument (alto

The musical term alto, meaning "high" in Italian (Latin: ''altus''), historically refers to the contrapuntal part higher than the tenor and its associated vocal range. In 4-part voice leading alto is the second-highest part, sung in choruses by ...

solo): "Man has measured the heavens", followed by an orchestral Interludium

# Scena (chorus and alto solo): "Is evil then good?"

# The Narrator ( bass solo): "Now in each nation there were some cast out"

# Chorus of the Oppressed: "When shall the usurer's city cease?"

# Tenor

A tenor is a type of classical music, classical male singing human voice, voice whose vocal range lies between the countertenor and baritone voice types. It is the highest male chest voice type. The tenor's vocal range extends up to C5. The lo ...

solo: "I have no money for my bread"

# Soprano solo: "How can I cherish my man?"

# A Spiritual (chorus and soli): "Steal Away

"Steal Away" ("Steal Away to Jesus") is an American Negro spiritual. The song is well known by variations of the chorus:

Songs such as "Steal Away to Jesus", "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot", "Wade in the Water" and the " Gospel Train" are songs with ...

"

Part II

# Conscientious objector

After the outbreak of war in September 1939, Tippett joined thePeace Pledge Union

The Peace Pledge Union (PPU) is a non-governmental organisation that promotes pacifism, based in the United Kingdom. Its members are signatories to the following pledge: "War is a crime against humanity. I renounce war, and am therefore determine ...

—with which he had been informally associated since 1935—and applied for registration as a conscientious objector, although his case was not considered by the tribunal until February 1942. In October 1940 he became director of music at Morley College

Morley College is a specialist adult education and further education college in London, England. The college has three main campuses, one in Waterloo on the South Bank, and two in West London namely in North Kensington and in Chelsea, the lat ...

,Kemp, pp. 40–41 where the previous April he had conducted the South London Orchestra in the premiere of his Concerto for Double String Orchestra. After completing the composition of ''A Child of Our Time'' in 1941, Tippett worked on other projects, feeling that the oratorio's pacifist message was out of touch with the prevailing national mood. Walter Goehr

Walter Goehr (; 28 May 19034 December 1960) was a German composer and conductor.

Biography

Goehr was born in Berlin, where he studied with Arnold Schoenberg and embarked on a conducting career, before being forced as a Jew to seek employment outs ...

, who conducted the Morley College orchestra, advised delaying its first performance until a more propitious time. In February 1942 Tippett was assigned by the tribunal to non-combative military duties. Following his appeal, this was changed to service either with Air Raid Precautions

Air Raid Precautions (ARP) refers to a number of organisations and guidelines in the United Kingdom dedicated to the protection of civilians from the danger of air raids. Government consideration for air raid precautions increased in the 1920s an ...

(ARP), with the fire service

A fire department (American English) or fire brigade (Commonwealth English), also known as a fire authority, fire district, fire and rescue, or fire service in some areas, is an organization that provides fire prevention and fire suppression se ...

or on the land. He felt obliged to refuse these directions, and as a result was sentenced in June 1943 to three months' imprisonment, of which he served two months before his early release for good behaviour.

Performance history and reception

Premiere

After his release from prison in August 1943, with encouragement from Britten and the youthful music criticJohn Amis

John Preston Amis (17 June 1922 – 1 August 2013) was a British broadcaster, classical music critic, music administrator, and writer. He was a frequent contributor for ''The Guardian'' and to BBC radio and television music programming.

Life a ...

, Tippett began to make arrangements for the oratorio's first performance.Kemp, pp. 52–53 Goehr agreed to conduct, but overrode the composer's initial view that Morley College's orchestra could handle the work and insisted that professionals were needed. Tippett records that "somehow or other the money was scraped together to engage the London Philharmonic Orchestra

The London Philharmonic Orchestra (LPO) is one of five permanent symphony orchestras based in London. It was founded by the conductors Sir Thomas Beecham and Malcolm Sargent in 1932 as a rival to the existing London Symphony and BBC Symphony ...

".Tippett 1994, pp. 156–57 Morley College Choir

Morley College Choir was founded by Gustav Holst, during the period he was teaching music at Morley College. The choir was led for many years by Michael Tippett, who conducted the ensemble for the first-ever recording of Thomas Tallis' Spem in Aliu ...

's choral forces were augmented by the London Regional Civil Defence Choir. Britten's connection with Sadler's Wells Opera

English National Opera (ENO) is an opera company based in London, resident at the London Coliseum in St Martin's Lane. It is one of the two principal opera companies in London, along with The Royal Opera. ENO's productions are sung in English. ...

brought three soloists to the project: Joan Cross

Joan Cross (7 September 1900 – 12 December 1993) was an English soprano, closely associated with the operas of Benjamin Britten. She also sang in the Italian and German operatic repertoires. She later became a musical administrator, taking on ...

(soprano), Peter Pears

Sir Peter Neville Luard Pears ( ; 22 June 19103 April 1986) was an English tenor. His career was closely associated with the composer Benjamin Britten, his personal and professional partner for nearly forty years.

Pears' musical career started ...

(tenor), and Roderick Lloyd (bass). The fourth singer, Margaret MacArthur (alto), came from Morley College. The premiere was arranged for 19 March 1944, at London's Adelphi Theatre

The Adelphi Theatre is a West End theatre, located on the Strand in the City of Westminster, central London. The present building is the fourth on the site. The theatre has specialised in comedy and musical theatre, and today it is a receiv ...

. Before this event Amis introduced the work in an article for the February 1944 issue of ''The Musical Times

''The Musical Times'' is an academic journal of classical music edited and produced in the United Kingdom and currently the oldest such journal still being published in the country.

It was originally created by Joseph Mainzer in 1842 as ''Mainze ...

'', in which he predicted a noteworthy musical occasion: "The general style of the oratorio is simple and direct, and the music will, I think, have an immediate effect on both audience and performers".

Later writers would state that ''A Child of Our Time'' placed Tippett in the first rank of the composers of his generation, and most of the early reviews were favourable. Among these, ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

''s critic called the work "strikingly original in conception and execution", and wrote that Tippett had succeeded quite remarkably in writing an effective tract for the times. A second ''Times'' review, written a few days after the premiere, suggested that the oratorio had articulated a key contemporary question: "How is the conflict of the inevitable with the intolerable to be resolved?" It pointed to the hope expressed in the final spiritual, "Deep River", and concluded that despite some weak passages the work created a successful partnership between art and philosophy. William Glock

Sir William Frederick Glock, CBE (3 May 190828 June 2000) was a British music critic and musical administrator who was instrumental in introducing the Continental avant-garde, notably promoting the career of Pierre Boulez.

Biography

Glock was bo ...

in ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the w ...

'' was laudatory: "The most moving and important work by an English composer for many years". Glock found that the spirituals suited the themes of the oratorio perfectly, and had been arranged "with a profound sense of beauty".

In ''The Musical Times'' Edwin Evans praised Tippett's text: "simple and direct ... he has wisely resisted any temptation to use quasi-biblical or 'Pilgrim's Progress' language." Evans was uncertain whether the music was truly reflective of the words: "the emotion seemed singularly cool under the provocations described in the text". Unlike Glock, Evans was unconvinced by the case for the inclusion of the spirituals: " e peculiar poignancy they have in their traditional form tends to evaporate in their new environment". Eric Blom, in ''Music & Letters

''Music & Letters'' is an academic journal published quarterly by Oxford University Press with a focus on musicology. The journal sponsors the Music & Letters Trust, twice-yearly cash awards of variable amounts to support research in the music fie ...

'', thought the idea of using spirituals "brilliant", and the analogy with Bach's chorales convincing. Blom was less enthusiastic about the text, which he found "very terse and bald – rather poor, really"—though he thought this preferable to the pomposities such as those that characterise libretti written for Handel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel (; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque composer well known for his operas, oratorios, anthems, concerti grossi, and organ concertos. Handel received his training i ...

. In his autobiography, Tippett makes only muted references to the premiere, noting that the event "had some mixed reviews", but in a letter to his friend Francesca Allinson he professed himself delighted with the breadth of response to the work: "It's got over not only to the ordinary listeners but even to the intellectuals like átyásSeiber, who has written to me of some of the 'lovely texture of some of the numbers'".

Early performances

The generally positive reception of the premiere persuadedArthur Bliss

Sir Arthur Edward Drummond Bliss (2 August 189127 March 1975) was an English composer and conductor.

Bliss's musical training was cut short by the First World War, in which he served with distinction in the army. In the post-war years he qu ...

, then serving as the BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...Royal Albert Hall

The Royal Albert Hall is a concert hall on the northern edge of South Kensington, London. One of the UK's most treasured and distinctive buildings, it is held in trust for the nation and managed by a registered charity which receives no govern ...

. The radio broadcast had been heard by Howard Hartog, a music writer and publisher who just after the war was in Occupied Germany

Germany was already de facto occupied by the Allies from the real fall of Nazi Germany in World War II on 8 May 1945 to the establishment of the East Germany on 7 October 1949. The Allies (United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and Franc ...

, attempting to re-establish the North German Radio Symphony Orchestra

The NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchestra (german: NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchester) is a German radio orchestra. Affiliated with the '' Norddeutscher Rundfunk'' (NDR; North German Broadcasting), the orchestra is based at the Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg ...

in Hamburg. As part of this endeavour he decided to mount a performance of ''A Child of Our Time'', with Hans Schmidt-Isserstedt

Hans Schmidt-Isserstedt (5 May 190028 May 1973) was a German conductor and composer. After studying at several music academies, he worked in German opera houses between 1923 and 1945, first as a répétiteur and then in increasingly senior conduc ...

conducting. Because of his pacifism and record as a conscientious objector, Tippett was not allowed into the occupied zone and thus missed the performance. However, in 1947 he was able to travel to Budapest where his friend, the Hungarian composer Mátyás Seiber

Mátyás György Seiber (; 4 May 190524 September 1960) was a Hungarian-born British composer who lived and worked in the United Kingdom from 1935 onwards. His work linked many diverse musical influences, from the Hungarian tradition of Bartó ...

, had organised a performance by Hungarian Radio Hungarian may refer to:

* Hungary, a country in Central Europe

* Kingdom of Hungary, state of Hungary, existing between 1000 and 1946

* Hungarians, ethnic groups in Hungary

* Hungarian algorithm, a polynomial time algorithm for solving the assignm ...

. The local singers' problems with the English text meant that the work was sung in Hungarian, which Tippett, who conducted, described as "a very odd experience".Tippett 1994, p. 192

In the early 1950s Tippett attended a performance of the oratorio at the Radio Hall in Brussels, after which members of the audience expressed to him their gratitude for the work which, they said, exactly represented their wartime experiences. In December 1952 he travelled to Turin for a radio performance, conducted by Herbert von Karajan

Herbert von Karajan (; born Heribert Ritter von Karajan; 5 April 1908 – 16 July 1989) was an Austrian conductor. He was principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic for 34 years. During the Nazi era, he debuted at the Salzburg Festival, wit ...

and with operatic stars Elisabeth Schwarzkopf

Dame Olga Maria Elisabeth Friederike Schwarzkopf, (9 December 19153 August 2006) was a German-born Austro-British soprano. She was among the foremost singers of lieder, and is renowned for her performances of Viennese operetta, as well as the op ...

and Nicolai Gedda

Harry Gustaf Nikolai Gädda, known professionally as Nicolai Gedda (11 July 1925 – 8 January 2017), was a Swedish operatic tenor. Debuting in 1951, Gedda had a long and successful career in opera until the age of 77 in June 2003, when he made h ...

among the soloists. He records that during the rehearsals the bass soloist, Mario Petri

Mario Petri (21 January 1922 – 26 January 1985) was an Italian operatic bass-baritone particularly associated with Mozart and Rossini roles.

Life and career

Petri was born in Perugia and began his career after World War II, making his stage d ...

, had problems singing his recitatives, and that despite some coaching from the composer, was still "at sea" during the performance. Karajan asked Tippett if he would object to an extra interval in Part II, to which Tippett replied that he would mind very much. Karajan nevertheless imposed the break, thus presenting a four-part version of the work.

Wider audience

In May 1962 ''A Child of Our Time'' received its Israel premiere in Tel Aviv.Steinberg, p. 287 Tippett says that this performance was delayed because for a while there were local objections to the word "Jesus" in the text. When it came about, among the audience was Herschel Grynszpan's father who, Tippett wrote, was "manifestly touched by the work his son's precipitate action 25 years earlier had inspired." The performance, by theKol Yisrael

''Kol Yisrael'' or ''Kol Israel'' ( lit. "Voice of Israel", also "Israel Radio") is Israel's public domestic and international radio service. It operated as a division of the Israel Broadcasting Service from 1951 to 1965, the Israel Broadcasti ...

Orchestra with the Tel Aviv Chamber Choir, was acclaimed by the audience of 3000, but received mixed reviews from the press. ''The Times'' report noted contrasting opinions from two leading Israeli newspapers. The correspondent for ''Haaretz

''Haaretz'' ( , originally ''Ḥadshot Haaretz'' – , ) is an Israeli newspaper. It was founded in 1918, making it the longest running newspaper currently in print in Israel, and is now published in both Hebrew and English in the Berliner f ...

'' had expressed disappointment: "Every tone is unoriginal, and the work repeats old effects in a most conventional manner". Conversely, according to the ''Times'' report, '' HaBokers critic had "found that the composition had moved everyone to the depths of his soul ... no Jewish composer had ever written anything so sublime on the theme of the Holocaust."

Despite its successes in Europe ''A Child of Our Time'' did not reach the United States until 1965, when it was performed during the Aspen Music Festival, with the composer present. In his memoirs Tippett mentions another performance on that American tour, at a women's college in Baltimore, in which the male chorus and soloists were black Catholic ordinands from a local seminary. The first significant American presentations of the work came a decade later: at Cleveland in 1977 where Prince Charles

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person to ...

, who was visiting, delayed his departure so that he could attend, and at Carnegie Hall

Carnegie Hall ( ) is a concert venue in Midtown Manhattan in New York City. It is at 881 Seventh Avenue (Manhattan), Seventh Avenue, occupying the east side of Seventh Avenue between West 56th Street (Manhattan), 56th and 57th Street (Manhatta ...

, New York, where Colin Davis

Sir Colin Rex Davis (25 September 1927 – 14 April 2013) was an English conductor, known for his association with the London Symphony Orchestra, having first conducted it in 1959. His repertoire was broad, but among the composers with whom h ...

conducted the Boston Symphony Orchestra

The Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) is an American orchestra based in Boston, Massachusetts. It is the second-oldest of the five major American symphony orchestras commonly referred to as the " Big Five". Founded by Henry Lee Higginson in 1881, ...

and the Tanglewood Festival Chorus. Reviewing this performance for ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', Donal Henahan

Donal Henahan (February 28, 1921 – August 19, 2012) was an American music critic and journalist who had lengthy associations with the ''Chicago Daily News'' and ''The New York Times''. With the ''Times'' he won the annual Pulitzer Prize for ...

was unconvinced that the work's "sincerity and unimpeachable intentions add dup to important music". The spirituals were sung with passion and fervour, but the rest was "reminiscent of a familiar pious sermon" in which the words were only intermittently intelligible. Meanwhile, the work had achieved its African debut, where in 1975 Tippett observed a performance with an improvised orchestra which incorporated the Zambian Police Band. The Zambian president, Kenneth Kaunda

Kenneth David Kaunda (28 April 1924 – 17 June 2021), also known as KK, was a Zambian politician who served as the first President of Zambia from 1964 to 1991. He was at the forefront of the struggle for independence from British rule. Dissat ...

, was present, and entertained the composer afterwards.

Later performances

In October 1999, in the year following Tippett's death, ''A Child of Our Time'' received a belatedNew York Philharmonic

The New York Philharmonic, officially the Philharmonic-Symphony Society of New York, Inc., globally known as New York Philharmonic Orchestra (NYPO) or New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra, is a symphony orchestra based in New York City. It is ...

premiere, at the Avery Fisher Hall

David Geffen Hall is a concert hall in New York City's Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts complex on Manhattan's Upper West Side. The 2,200-seat auditorium opened in 1962, and is the home of the New York Philharmonic.

The facility, desi ...

. The ''New York Times'' reviewer, Paul Griffiths, expressed some astonishment that this was the orchestra's first attempt at the work. As part of the celebrations for the centenary of the composer's birth in January 2005, English National Opera

English National Opera (ENO) is an opera company based in London, resident at the London Coliseum in St Martin's Lane. It is one of the two principal opera companies in London, along with The Royal Opera. ENO's productions are sung in English ...

staged a dramatised performance of the work, directed by Jonathan Kent—coincidentally, the first performance fell in the week of the 60th anniversary of the liberation of the death camps at Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It con ...

. Anna Picard, writing in ''The Independent

''The Independent'' is a British online newspaper. It was established in 1986 as a national morning printed paper. Nicknamed the ''Indy'', it began as a broadsheet and changed to tabloid format in 2003. The last printed edition was publis ...

'', recognised the work's sincerity but found the dramatisation of its pacifist message wholly inappropriate: "Do we really need to see a dozen well-fed actors and singers stripped and led into a smoking pit in order to understand the Holocaust?" Anthony Holden

Anthony Holden (born 22 May 1947) is an English writer, broadcaster and critic, particularly known as a biographer of artists including Shakespeare, Tchaikovsky, the essayist Leigh Hunt, the opera librettist Lorenzo Da Ponte and the actor Laure ...

in ''The Observer'' was more positive, commenting that "If you must stage a work intended for concert performance ... it is hard to imagine a more effective version than Kent's, shot through with heavy symbolism of which Tippett would surely have approved." Nevertheless, Holden found the overall result "super-solemn, lurching between the over-literalistic and the portentous". The 2005 Holocaust Days of Remembrance (1–8 May) were marked at the Kennedy Center

The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts (formally known as the John F. Kennedy Memorial Center for the Performing Arts, and commonly referred to as the Kennedy Center) is the United States National Cultural Center, located on the Potom ...

in Washington DC by a special performance of ''A Child of Our time'', in which the Washington Chorus was directed by Robert Shafer. The piece was performed at the BBC Proms 2016 on 23 July by the BBC National Orchestra and Chorus of Wales.

''A Child of Our Time'' has survived periods of indifference, particularly in America, to be ranked alongside Britten's ''War Requiem

The ''War Requiem'', Op. 66, is a large-scale setting of the Requiem composed by Benjamin Britten mostly in 1961 and completed in January 1962. The ''War Requiem'' was performed for the consecration of the new Coventry Cathedral, which was b ...

'' as one of the most frequently performed large-scale choral works of the post-Second World War period. According to Meirion Bowen, Tippett's long-time companion and a champion of his music, the work's particular quality is its universal message, with which audiences all over the world have identified. In his notes accompanying the performance at the 2010 Grant Park Music Festival

The Grant Park Music Festival (formerly the Grant Park Concerts) is a ten-week classical music concert series held annually in Chicago, Illinois, United States. It features the Grant Park Symphony Orchestra and Grant Park Chorus along with guest ...

in Chicago, Richard E. Rodda summarises the work's continuing appeal: " deals with issues as timeless as civilization itself—man's inhumanity to man, the place of the individual who confronts ruthless power ... the need for learning the lessons of history and for compassion and understanding and honesty and equality in our dealings with each other, whatever our differences may be. Tippett's ''Child'' still speaks profoundly to us in our own deeply troubled time".

Music

Kemp describes Tippett's central problem in composing ''A Child of Our Time'' as integrating the language of the spirituals with his own musical style. Tippett was, in Kemp's view, entirely successful in this respect; "O by and by", he says, sounds as if it could almost have been composed by Tippett. To assist the process of integration the composer had obtained recordings of American singing groups, especially the Hall Johnson Choir, which provided him with a three-part model for determining the relationships between solo voices and chorus in the spirituals: chorus, soloists, chorus.Kemp, p. 172 Tippett's instructions in the score specify that "the spirituals should not be thought of as congregational hymns, but as integral parts of the Oratorio; nor should they be sentimentalised but sung with a strong underlying beat and slightly 'swung'".

The brief orchestral prelude to Part I introduces the two contrasting moods which pervade the entire work. Kemp likens the opening "snarling trumpet triad" to "a descent into Hades", but it is answered immediately by a gently mournful phrase in the strings. In general the eight numbers which comprise this first part each have, says Gloag, their own distinct texture and harmonic identity, often in a disjunctive relationship with each other, although the second and third numbers are connected by an orchestral "interludium". From among the diverse musical features Steinberg draws attention to rhythms in the chorus "When Shall The Usurer's City Cease" that illustrate Tippett's knowledge of and feel for the English

Kemp describes Tippett's central problem in composing ''A Child of Our Time'' as integrating the language of the spirituals with his own musical style. Tippett was, in Kemp's view, entirely successful in this respect; "O by and by", he says, sounds as if it could almost have been composed by Tippett. To assist the process of integration the composer had obtained recordings of American singing groups, especially the Hall Johnson Choir, which provided him with a three-part model for determining the relationships between solo voices and chorus in the spirituals: chorus, soloists, chorus.Kemp, p. 172 Tippett's instructions in the score specify that "the spirituals should not be thought of as congregational hymns, but as integral parts of the Oratorio; nor should they be sentimentalised but sung with a strong underlying beat and slightly 'swung'".

The brief orchestral prelude to Part I introduces the two contrasting moods which pervade the entire work. Kemp likens the opening "snarling trumpet triad" to "a descent into Hades", but it is answered immediately by a gently mournful phrase in the strings. In general the eight numbers which comprise this first part each have, says Gloag, their own distinct texture and harmonic identity, often in a disjunctive relationship with each other, although the second and third numbers are connected by an orchestral "interludium". From among the diverse musical features Steinberg draws attention to rhythms in the chorus "When Shall The Usurer's City Cease" that illustrate Tippett's knowledge of and feel for the English madrigal

A madrigal is a form of secular vocal music most typical of the Renaissance (15th–16th c.) and early Baroque (1600–1750) periods, although revisited by some later European composers. The polyphonic madrigal is unaccompanied, and the number o ...

. What Kemp describes as "one of the supreme moments in Tippett's music" occurs towards the end of the Part, as the soprano's aria melts into the spiritual "Steal away": "a ransitionso poignant as to set off that instant shock of recognition that floods the eyes with emotion ... although the soprano continues to grieve in a floating melisma

Melisma ( grc-gre, μέλισμα, , ; from grc, , melos, song, melody, label=none, plural: ''melismata'') is the singing of a single syllable of text while moving between several different notes in succession. Music sung in this style is referr ...

, the spiritual comes as a relief as well as a release".

Because of its large number (17) of generally short components, Part II is the most diffuse of the three parts, texturally and harmonically. The narrative is driven largely by alternating choruses and comments from the Narrator, with two brief operatic scenas in which the four soloists participate. Kemp finds in one of the choruses an allusion to "Sei gegrüsset" from Bach's ''St John Passion

The ''Passio secundum Joannem'' or ''St John Passion'' (german: Johannes-Passion, link=no), BWV 245, is a Passion or oratorio by Johann Sebastian Bach, the older of the surviving Passions by Bach. It was written during his first year as direc ...

'', and hears traces of Elgar

Sir Edward William Elgar, 1st Baronet, (; 2 June 1857 – 23 February 1934) was an English composer, many of whose works have entered the British and international classical concert repertoire. Among his best-known compositions are orchestr ...

in the soprano's solo "O my son!" which begins the first scena. The narrative climax is reached with the "Spiritual of Anger": "Go Down, Moses", which Tippett arranges in the form of a chorale. This is followed by three short meditations from tenor, soprano and alto soloists, before a possible redemption is glimpsed in the spiritual which ends the Part, "O by and by", with a soprano descant which Steinberg describes as "ecstatic". Part III consists of only five numbers, each rather more extensive than most of those in the earlier sections of the oratorio. The Part has, on the whole, a greater unity than its predecessors. The musical and emotional climax to the whole work is the penultimate ensemble: "I Would Know my Shadow and my Light". Kemp writes: "The whole work has been leading to this moment ... the ensemble flows into a rapturous wordless benediction eforea modulation leads into 'Deep River'". In this final spiritual, for the first time the full vocal and instrumental resources are deployed. The oratorio ends quietly, on an extended ''pianissimo'' "Lord".

The total vocal and instrumental resources required for the oratorio are a SATB

SATB is an initialism that describes the scoring of compositions for choirs, and also choirs (or consorts) of instruments. The initials are for the voice types: S for soprano, A for alto, T for tenor and B for bass.

Choral music

Four-part harm ...

chorus with soprano, alto, tenor and bass soloists, and an orchestra comprising two flutes, two oboes, English horn, two clarinets, two bassoons, contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, timpani, cymbals and strings. According to the vocal score, the approximate duration of the work is 66 minutes.Tippett 1944, pp. ii–ivSteinberg, p. 280

Recordings

The first recording of ''A Child of Our Time'' was issued in 1958, and remained the only available version for 17 years.Sir Colin Davis

Sir Colin Rex Davis (25 September 1927 – 14 April 2013) was an English conductor, known for his association with the London Symphony Orchestra, having first conducted it in 1959. His repertoire was broad, but among the composers with whom h ...

made the first of his three recordings of the work in 1975. Tippett himself, at the age of 86, conducted a recording of the work with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra

The City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra (CBSO) is a British orchestra based in Birmingham, England. It is the resident orchestra at Symphony Hall: a B:Music Venue in Birmingham, which has been its principal performance venue since 1991. Its a ...

and Chorus in 1991.

Notes and references

Notes Citations Bibliography * * * * * * *Further reading

*External links

* Richard Smith, ''An introduction to Michael Tippett's 'A Child of Our Time, documentary,Libretto (on pp. 10–11)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Child Of Our Time, A 1941 compositions Compositions by Michael Tippett Kristallnacht Works about the Holocaust Oratorios