AM broadcast band on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

AM broadcasting is

The person generally credited as the primary early developer of AM technology is Canadian-born inventor

The person generally credited as the primary early developer of AM technology is Canadian-born inventor

Part I

January 26, 1907, pages 49-51

Part II

February 2, 1907, pages 68-70, 79-80. An ''American Telephone Journal'' account of the December 21 alternator-transmitter demonstration included the statement that "It is admirably adapted to the transmission of news, music, etc. as, owing to the fact that no wires are needed, simultaneous transmission to many subscribers can be effected as easily as to a few", echoing the words of a handout distributed to the demonstration witnesses, which stated " adioTelephony is admirably adapted for transmitting news, stock quotations, music, race reports, etc. simultaneously over a city, on account of the fact that no wires are needed and a single apparatus can distribute to ten thousand subscribers as easily as to a few. It is proposed to erect stations for this purpose in the large cities here and abroad." However, other than two holiday transmissions reportedly made shortly after these demonstrations, Fessenden does not appear to have conducted any radio broadcasts for the general public, or to have even given additional thought about the potential of a regular broadcast service, and in a 1908 article providing a comprehensive review of the potential uses for his radiotelephone invention, he made no references to broadcasting. Because there was no way to amplify electrical currents at this time, modulation was usually accomplished by a carbon

/ref> AM radio offered the highest sound quality available in a home audio device prior to the introduction of the high-fidelity,

Following World War I, the number of stations providing a regular broadcasting service greatly increased, primarily due to advances in vacuum-tube technology. In response to ongoing activities, government regulators eventually codified standards for which stations could make broadcasts intended for the general public, for example, in the United States formal recognition of a "broadcasting service" came with the establishment of regulations effective December 1, 1921, and Canadian authorities created a separate category of "radio-telephone broadcasting stations" in April 1922. However, there were numerous cases of entertainment broadcasts being presented on a regular schedule before their formal recognition by government regulators. Some early examples include:

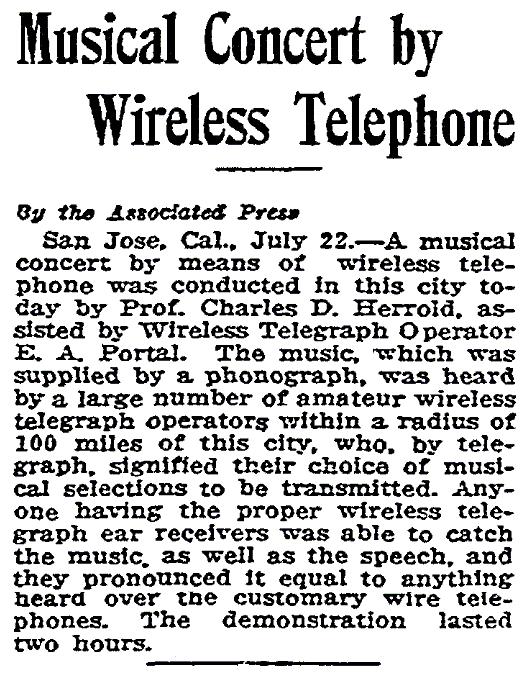

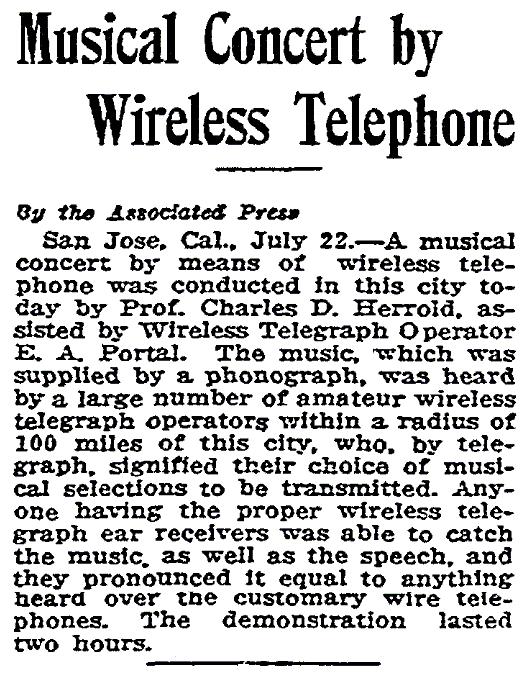

* July 21, 1912 The first person to transmit entertainment broadcasts on a regular schedule appears to have been Charles "Doc" Herrold, who inaugurated weekly programs, using an arc transmitter, from his Wireless School station in San Jose, California. The broadcasts continued until the station was shut down due to the entrance of the United States into World War I in April 1917.

* March 28, 1914 The Laeken station in Belgium, under the oversight of Robert Goldschmidt, inaugurated a weekly series of concerts, transmitted at 5:00 p.m. on Saturdays. These continued for about four months until July, and were ended by the start of World War I. In August 1914 the Laeken facilities were destroyed, to keep them from falling into the hands of invading German troops.

* November 1916 De Forest perfected "Oscillion" power vacuum tubes, capable of use in radio transmitters, and inaugurated daily broadcasts of entertainment and news from his New York "Highbridge" station, 2XG. This station also suspended operations in April 1917 due to the prohibition of civilian radio transmissions following the United States' entry into World War I. Its most publicized program was the broadcasting of election results for the Hughes-Wilson presidential election on November 7, 1916, with updates provided by wire from the ''

Following World War I, the number of stations providing a regular broadcasting service greatly increased, primarily due to advances in vacuum-tube technology. In response to ongoing activities, government regulators eventually codified standards for which stations could make broadcasts intended for the general public, for example, in the United States formal recognition of a "broadcasting service" came with the establishment of regulations effective December 1, 1921, and Canadian authorities created a separate category of "radio-telephone broadcasting stations" in April 1922. However, there were numerous cases of entertainment broadcasts being presented on a regular schedule before their formal recognition by government regulators. Some early examples include:

* July 21, 1912 The first person to transmit entertainment broadcasts on a regular schedule appears to have been Charles "Doc" Herrold, who inaugurated weekly programs, using an arc transmitter, from his Wireless School station in San Jose, California. The broadcasts continued until the station was shut down due to the entrance of the United States into World War I in April 1917.

* March 28, 1914 The Laeken station in Belgium, under the oversight of Robert Goldschmidt, inaugurated a weekly series of concerts, transmitted at 5:00 p.m. on Saturdays. These continued for about four months until July, and were ended by the start of World War I. In August 1914 the Laeken facilities were destroyed, to keep them from falling into the hands of invading German troops.

* November 1916 De Forest perfected "Oscillion" power vacuum tubes, capable of use in radio transmitters, and inaugurated daily broadcasts of entertainment and news from his New York "Highbridge" station, 2XG. This station also suspended operations in April 1917 due to the prohibition of civilian radio transmissions following the United States' entry into World War I. Its most publicized program was the broadcasting of election results for the Hughes-Wilson presidential election on November 7, 1916, with updates provided by wire from the ''

''The Electrical Experimenter'', January 1917, page 650. (archive.org) * April 17, 1919 Shortly after the end of World War I, F. S. McCullough at the Glenn L. Martin aviation plant in Cleveland, Ohio, began a weekly series of phonograph concerts. However, the broadcasts were soon suspended, due to interference complaints by the U.S. Navy. * November 6, 1919 The first scheduled (pre-announced in the press) Dutch radio broadcast was made by Nederlandsche Radio Industrie station

Because most longwave radio frequencies were used for international radiotelegraph communication, a majority of early broadcasting stations operated on mediumwave frequencies, whose limited range generally restricted them to local audiences. One method for overcoming this limitation, as well as a method for sharing program costs, was to create radio

Because most longwave radio frequencies were used for international radiotelegraph communication, a majority of early broadcasting stations operated on mediumwave frequencies, whose limited range generally restricted them to local audiences. One method for overcoming this limitation, as well as a method for sharing program costs, was to create radio

A second country which quickly adopted network programming was the United Kingdom, and its national network quickly became a prototype for a state-managed monopoly of broadcasting. A rising interest in radio broadcasting by the British public pressured the government to reintroduce the service, following its suspension in 1920. However, the government also wanted to avoid what it termed the "chaotic" U.S. experience of allowing large numbers of stations to operate with few restrictions. There were also concerns about broadcasting becoming dominated by the Marconi company. Arrangements were made for six large radio manufacturers to form a consortium, the

A second country which quickly adopted network programming was the United Kingdom, and its national network quickly became a prototype for a state-managed monopoly of broadcasting. A rising interest in radio broadcasting by the British public pressured the government to reintroduce the service, following its suspension in 1920. However, the government also wanted to avoid what it termed the "chaotic" U.S. experience of allowing large numbers of stations to operate with few restrictions. There were also concerns about broadcasting becoming dominated by the Marconi company. Arrangements were made for six large radio manufacturers to form a consortium, the

The period from the early 1920s through the 1940s is often called the "Golden Age of Radio". During this period AM radio was the main source of home entertainment, until it was replaced by television. For the first time entertainment was provided from outside the home, replacing traditional forms of entertainment such as oral storytelling and music from family members. New forms were created, including

The period from the early 1920s through the 1940s is often called the "Golden Age of Radio". During this period AM radio was the main source of home entertainment, until it was replaced by television. For the first time entertainment was provided from outside the home, replacing traditional forms of entertainment such as oral storytelling and music from family members. New forms were created, including

(fcc.gov) however overall there was limited adoption of AM stereo worldwide, and interest declined after 1990. With the continued migration of AM stations away from music to news, sports, and talk formats, receiver manufacturers saw little reason to adopt the more expensive stereo tuners, and thus radio stations have little incentive to upgrade to stereo transmission. In countries where the use of directional antennas is common, such as the United States, transmitter sites consisting of multiple towers often occupy large tracts of land that have significantly increased in value over the decades, to the point that the value of land exceeds that of the station itself. This sometimes results in the sale of the transmitter site, with the station relocating to a more distant shared site using significantly less power, or completely shutting down operations. The ongoing development of alternative transmission systems, including Digital Audio Broadcasting (DAB), satellite radio, and HD (digital) radio, continued the decline of the popularity of the traditional broadcast technologies. These new options, including the introduction of Internet streaming, particularly resulted in the reduction of shortwave transmissions, as international broadcasters found ways to reach their audiences more easily.

In 1961, the FCC adopted a single standard for FM stereo transmissions, which was widely credited with enhancing FM's popularity. Developing the technology for AM broadcasting in stereo was challenging due to the need to limit the transmissions to a 20 kHz bandwidth, while also making the transmissions backward compatible with existing non-stereo receivers. In 1990, the FCC authorized an AM stereo standard developed by Magnavox, but two years later revised its decision to instead approve four competing implementations, saying it would "let the marketplace decide" which was best. The lack of a common standard resulted in consumer confusion and increased the complexity and cost of producing AM stereo receivers. In 1993, the FCC again revised its policy, by selecting

In 1961, the FCC adopted a single standard for FM stereo transmissions, which was widely credited with enhancing FM's popularity. Developing the technology for AM broadcasting in stereo was challenging due to the need to limit the transmissions to a 20 kHz bandwidth, while also making the transmissions backward compatible with existing non-stereo receivers. In 1990, the FCC authorized an AM stereo standard developed by Magnavox, but two years later revised its decision to instead approve four competing implementations, saying it would "let the marketplace decide" which was best. The lack of a common standard resulted in consumer confusion and increased the complexity and cost of producing AM stereo receivers. In 1993, the FCC again revised its policy, by selecting

HD Radio is a digital audio broadcasting method developed by

HD Radio is a digital audio broadcasting method developed by

Despite the various actions, AM band audiences continued to contract, and the number of stations began to slowly decline. A 2009 FCC review reported that "The story of AM radio over the last 50 years has been a transition from being the dominant form of audio entertainment for all age groups to being almost non-existent to the youngest demographic groups. Among persons aged 12-24, AM accounts for only 4% of listening, while FM accounts for 96%. Among persons aged 25-34, AM accounts for only 9% of listening, while FM accounts for 91%. The median age of listeners to the AM band is 57 years old, a full generation older than the median age of FM listeners.""Report and Order: In the Matter of Amendment of Service and Eligibility Rules for FM Broadcast Translator Stations"

Despite the various actions, AM band audiences continued to contract, and the number of stations began to slowly decline. A 2009 FCC review reported that "The story of AM radio over the last 50 years has been a transition from being the dominant form of audio entertainment for all age groups to being almost non-existent to the youngest demographic groups. Among persons aged 12-24, AM accounts for only 4% of listening, while FM accounts for 96%. Among persons aged 25-34, AM accounts for only 9% of listening, while FM accounts for 91%. The median age of listeners to the AM band is 57 years old, a full generation older than the median age of FM listeners.""Report and Order: In the Matter of Amendment of Service and Eligibility Rules for FM Broadcast Translator Stations"

(MB Docket Mo. 07-172, RM-11338), June 29, 2009, pages 9642-9660. In 2009, the FCC made a major regulatory change, when it adopted a policy allowing AM stations to simulcast over FM translator stations. Translators had previously been available only to FM broadcasters, in order to increase coverage in fringe areas. Their assignment for use by AM stations was intended to approximate the station's daytime coverage, which in cases where the stations reduced power at night, often resulted in expanded nighttime coverage. Although the translator stations are not permitted to originate programming when the "primary" AM station is broadcasting, they are permitted to do so during nighttime hours for AM stations licensed for daytime-only operation."FCC OK's AM on FM Translators"

by FHH Law, June 30, 2009 (commlawblog.com). Prior to the adoption of the new policy, as of March 18, 2009 the FCC had issued 215 Special Temporary Authority grants for FM translators relaying AM stations. After creation of the new policy, by 2011 there were approximately 500 in operation, and as of 2020 approximately 2,800 of the 4,570 licensed AM stations were rebroadcasting on one or more FM translators."Special Report: AM Advocates Watch and Worry"

by Randy J. Stine, October 5, 2020 (radioworld.com) In 2009 the FCC stated that "We do not intend to allow these cross-service translators to be used as surrogates for FM stations". However, based on station slogans, especially in the case of recently adopted musical formats, in most cases the expectation is that listeners will primarily be tuning into the FM signal rather than the nominally "primary" AM station. A 2020 review noted that "for many owners, keeping their AM stations on the air now is pretty much just about retaining their FM translator footprint rather than keeping the AM on the air on its own merits".

"Digital Radio"

(fcc.gov) while

radio broadcasting

Radio broadcasting is transmission of audio (sound), sometimes with related metadata, by radio waves to radio receivers belonging to a public audience. In terrestrial radio broadcasting the radio waves are broadcast by a land-based radio ...

using amplitude modulation

Amplitude modulation (AM) is a modulation technique used in electronic communication, most commonly for transmitting messages with a radio wave. In amplitude modulation, the amplitude (signal strength) of the wave is varied in proportion to ...

(AM) transmissions. It was the first method developed for making audio radio transmissions, and is still used worldwide, primarily for medium wave

Medium wave (MW) is the part of the medium frequency (MF) radio band used mainly for AM radio broadcasting. The spectrum provides about 120 channels with more limited sound quality than FM stations on the FM broadcast band. During the daytime ...

(also known as "AM band") transmissions, but also on the longwave

In radio, longwave, long wave or long-wave, and commonly abbreviated LW, refers to parts of the radio spectrum with wavelengths longer than what was originally called the medium-wave broadcasting band. The term is historic, dating from the e ...

and shortwave radio

Shortwave radio is radio transmission using shortwave (SW) radio frequencies. There is no official definition of the band, but the range always includes all of the high frequency band (HF), which extends from 3 to 30 MHz (100 to 10 me ...

bands.

The earliest experimental AM transmissions began in the early 1900s. However, widespread AM broadcasting was not established until the 1920s, following the development of vacuum tube

A vacuum tube, electron tube, valve (British usage), or tube (North America), is a device that controls electric current flow in a high vacuum between electrodes to which an electric voltage, potential difference has been applied.

The type kn ...

receivers and transmitters. AM radio remained the dominant method of broadcasting for the next 30 years, a period called the "Golden Age of Radio

The Golden Age of Radio, also known as the old-time radio (OTR) era, was an era of radio in the United States where it was the dominant electronic home entertainment, entertainment medium. It began with the birth of commercial radio broadcastin ...

", until television broadcasting became widespread in the 1950s and received most of the programming previously carried by radio. Subsequently, AM radio's audiences have also greatly shrunk due to competition from FM (frequency modulation

Frequency modulation (FM) is the encoding of information in a carrier wave by varying the instantaneous frequency of the wave. The technology is used in telecommunications, radio broadcasting, signal processing, and Run-length limited#FM: .280. ...

) radio, Digital Audio Broadcasting

Digital radio is the use of digital technology to transmit or receive across the radio spectrum. Digital transmission by radio waves includes digital broadcasting, and especially digital audio radio services.

Types

In digital broadcasting syst ...

(DAB), satellite radio

Satellite radio is defined by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU)'s ITU Radio Regulations (RR) as a ''broadcasting-satellite service''. The satellite's signals are broadcast nationwide, across a much wider geographical area than ter ...

, HD (digital) radio, Internet radio

Online radio (also web radio, net radio, streaming radio, e-radio, IP radio, Internet radio) is a digital audio service transmitted via the Internet. Broadcasting on the Internet is usually referred to as webcasting since it is not transmitted ...

, music streaming service

A music streaming service is a type of streaming media service that focuses primarily on music, and sometimes other forms of digital audio content such as podcasts. These services are usually subscription-based services allowing users to stream d ...

s, and podcasting

A podcast is a program made available in digital format for download over the Internet. For example, an episodic series of digital audio or video files that a user can download to a personal device to listen to at a time of their choosing ...

.

AM transmissions are much more susceptible to interference than FM or digital

Digital usually refers to something using discrete digits, often binary digits.

Technology and computing Hardware

*Digital electronics, electronic circuits which operate using digital signals

**Digital camera, which captures and stores digital i ...

signals, and often have lower audio fidelity. Thus, AM broadcasters tend to specialise in spoken-word formats, such as talk radio

Talk radio is a radio format containing discussion about topical issues and consisting entirely or almost entirely of original spoken word content rather than outside music. Most shows are regularly hosted by a single individual, and often featur ...

, all news

All-news radio is a radio format devoted entirely to the discussion and broadcast of news.

All-news radio is available in both local and syndicated forms, and is carried on both major US satellite radio networks. All-news stations can run the ...

and sports

Sport pertains to any form of competitive physical activity or game that aims to use, maintain, or improve physical ability and skills while providing enjoyment to participants and, in some cases, entertainment to spectators. Sports can, th ...

, with music formats primarily for FM and digital stations.

History

Early broadcasting development

The idea of broadcasting — the unrestricted transmission of signals to a widespread audience — dates back to the founding period of radio development, even though the earliest radio transmissions, originally known as "Hertzian radiation" and "wireless telegraphy", usedspark-gap transmitter

A spark-gap transmitter is an obsolete type of radio transmitter which generates radio waves by means of an electric spark."Radio Transmitters, Early" in Spark-gap transmitters were the first type of radio transmitter, and were the main type use ...

s that could only transmit the dots-and-dashes of Morse code

Morse code is a method used in telecommunication to encode text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code is named after Samuel Morse, one of ...

. In October 1898 a London publication, ''The Electrician'', noted that "there are rare cases where, as Dr. liverLodge once expressed it, it might be advantageous to 'shout' the message, spreading it broadcast to receivers in all directions". However, it was recognized that this would involve significant financial issues, as that same year ''The Electrician'' also commented "did not Prof. Lodge forget that no one wants to pay for shouting to the world on a system by which it would be impossible to prevent non-subscribers from benefiting gratuitously?"

On January 1, 1902, Nathan Stubblefield

Nathan Beverly Stubblefield (November 22, 1860 – March 28, 1928) was an American inventor best known for his wireless telephone work. Self-described as a "practical farmer, fruit grower and electrician",

gave a short-range "wireless telephone" demonstration, that included simultaneously broadcasting speech and music to seven locations throughout Murray, Kentucky. However, this was transmitted using induction

Induction, Inducible or Inductive may refer to:

Biology and medicine

* Labor induction (birth/pregnancy)

* Induction chemotherapy, in medicine

* Induced stem cells, stem cells derived from somatic, reproductive, pluripotent or other cell t ...

rather than radio signals, and although Stubblefield predicted that his system would be perfected so that "it will be possible to communicate with hundreds of homes at the same time", and "a single message can be sent from a central station to all parts of the United States", he was unable to overcome the inherent distance limitations of this technology.

The earliest public radiotelegraph broadcasts were provided as government services, beginning with daily time signals inaugurated on January 1, 1905, by a number of U.S. Navy stations. In Europe, signals transmitted from a station located on the Eiffel tower

The Eiffel Tower ( ; french: links=yes, tour Eiffel ) is a wrought-iron lattice tower on the Champ de Mars in Paris, France. It is named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built the tower.

Locally nicknamed "'' ...

were received throughout much of Europe. In both the United States and France this led to a small market of receiver lines geared for jewelers who needed accurate time to set their clocks, including the Ondophone in France, and the De Forest RS-100 Jewelers Time Receiver in the United States

The ability to pick up time signal broadcasts, in addition to Morse code weather reports and news summaries, also attracted the interest of amateur radio

Amateur radio, also known as ham radio, is the use of the radio frequency spectrum for purposes of non-commercial exchange of messages, wireless experimentation, self-training, private recreation, radiosport, contesting, and emergency communic ...

enthusiasts.

Early amplitude modulation (AM) transmitter technologies

It was immediately recognized that, much like the telegraph had preceded the invention of the telephone, the ability to make audio radio transmissions would be a significant technical advance. Despite this knowledge, it still took two decades to perfect the technology needed to make quality audio transmissions. In addition, the telephone had rarely been used for distributing entertainment, outside of a few "telephone newspaper Telephone Newspapers, introduced in the 1890s, transmitted news and entertainment to subscribers over telephone lines. They were the first example of electronic broadcasting, although only a few were established, most commonly in European cities. Th ...

" systems, most of which were established in Europe. With this in mind, most early radiotelephone

A radiotelephone (or radiophone), abbreviated RT, is a radio communication system for conducting a conversation; radiotelephony means telephony by radio. It is in contrast to '' radiotelegraphy'', which is radio transmission of telegrams (mes ...

development envisioned that the device would be more profitably developed as a "wireless telephone" for personal communication, or for providing links where regular telephone lines could not be run, rather than for the uncertain finances of broadcasting.

The person generally credited as the primary early developer of AM technology is Canadian-born inventor

The person generally credited as the primary early developer of AM technology is Canadian-born inventor Reginald Fessenden

Reginald Aubrey Fessenden (October 6, 1866 – July 22, 1932) was a Canadian-born inventor, who did a majority of his work in the United States and also claimed U.S. citizenship through his American-born father. During his life he received hundre ...

. The original spark-gap radio transmitters were impractical for transmitting audio, since they produced discontinuous pulses known as "damped wave

Damping is an influence within or upon an oscillatory system that has the effect of reducing or preventing its oscillation. In physical systems, damping is produced by processes that dissipate the energy stored in the oscillation. Examples inc ...

s". Fessenden realized that what was needed was a new type of radio transmitter that produced steady "undamped" (better known as "continuous wave

A continuous wave or continuous waveform (CW) is an electromagnetic wave of constant amplitude and frequency, typically a sine wave, that for mathematical analysis is considered to be of infinite duration. It may refer to e.g. a laser or particle ...

") signals, which could then be "modulated" to reflect the sounds being transmitted.

Fessenden's basic approach was disclosed in U.S. Patent 706,737, which he applied for on May 29, 1901, and was issued the next year. It called for the use of a high-speed alternator

An alternator is an electrical generator that converts mechanical energy to electrical energy in the form of alternating current. For reasons of cost and simplicity, most alternators use a rotating magnetic field with a stationary armature.Go ...

(referred to as "an alternating-current dynamo") that generated "pure sine waves" and produced "a continuous train of radiant waves of substantially uniform strength", or, in modern terminology, a continuous-wave (CW) transmitter. Fessenden began his research on audio transmissions while doing developmental work for the United States Weather Service on Cobb Island, Maryland. Because he did not yet have a continuous-wave transmitter, initially he worked with an experimental "high-frequency spark" transmitter, taking advantage of the fact that the higher the spark rate, the closer a spark-gap transmission comes to producing continuous waves. He later reported that, in the fall of 1900, he successfully transmitted speech over a distance of about 1.6 kilometers (one mile), which appears to have been the first successful audio transmission using radio signals. However, at this time the sound was far too distorted to be commercially practical. For a time he continued working with more sophisticated high-frequency spark transmitters, including versions that used compressed air, which began to take on some of the characteristics of arc-transmitters. Fessenden attempted to sell this form of radiotelephone for point-to-point communication, but was unsuccessful.

Alternator transmitter

Fessenden's work with high-frequency spark transmissions was only a temporary measure. His ultimate plan for creating an audio-capable transmitter was to redesign an electricalalternator

An alternator is an electrical generator that converts mechanical energy to electrical energy in the form of alternating current. For reasons of cost and simplicity, most alternators use a rotating magnetic field with a stationary armature.Go ...

, which normally produced alternating current of at most a few hundred ( Hz), to increase its rotational speed and so generate currents of tens-of-thousands Hz, thus producing a steady continuous-wave transmission when connected to an aerial. The next step, adopted from standard wire-telephone practice, was to insert a simple carbon microphone

The carbon microphone, also known as carbon button microphone, button microphone, or carbon transmitter, is a type of microphone, a transducer that converts sound to an electrical audio signal. It consists of two metal plates separated by granu ...

into the transmission line, to modulate the carrier wave

In telecommunications, a carrier wave, carrier signal, or just carrier, is a waveform (usually sinusoidal) that is modulated (modified) with an information-bearing signal for the purpose of conveying information. This carrier wave usually has a ...

signal to produce AM audio transmissions. However, it would take many years of expensive development before even a prototype alternator-transmitter would be ready, and a few years beyond that for high-power versions to become available.

Fessenden worked with General Electric

General Electric Company (GE) is an American multinational conglomerate founded in 1892, and incorporated in New York state and headquartered in Boston. The company operated in sectors including healthcare, aviation, power, renewable energ ...

's (GE) Ernst F. W. Alexanderson, who in August 1906 delivered an improved model which operated at a transmitting frequency of approximately 50 kHz, although at low power. The alternator-transmitter achieved the goal of transmitting quality audio signals, but the lack of any way to amplify the signals meant they were somewhat weak. On December 21, 1906, Fessenden made an extensive demonstration of the new alternator-transmitter at Brant Rock, Massachusetts, showing its utility for point-to-point wireless telephony, including interconnecting his stations to the wire telephone network. As part of the demonstration, speech was transmitted 18 kilometers (11 miles) to a listening site at Plymouth, Massachusetts."Experiments and Results in Wireless Telephony" by John Grant, ''The American Telephone Journal''Part I

January 26, 1907, pages 49-51

Part II

February 2, 1907, pages 68-70, 79-80. An ''American Telephone Journal'' account of the December 21 alternator-transmitter demonstration included the statement that "It is admirably adapted to the transmission of news, music, etc. as, owing to the fact that no wires are needed, simultaneous transmission to many subscribers can be effected as easily as to a few", echoing the words of a handout distributed to the demonstration witnesses, which stated " adioTelephony is admirably adapted for transmitting news, stock quotations, music, race reports, etc. simultaneously over a city, on account of the fact that no wires are needed and a single apparatus can distribute to ten thousand subscribers as easily as to a few. It is proposed to erect stations for this purpose in the large cities here and abroad." However, other than two holiday transmissions reportedly made shortly after these demonstrations, Fessenden does not appear to have conducted any radio broadcasts for the general public, or to have even given additional thought about the potential of a regular broadcast service, and in a 1908 article providing a comprehensive review of the potential uses for his radiotelephone invention, he made no references to broadcasting. Because there was no way to amplify electrical currents at this time, modulation was usually accomplished by a carbon

microphone

A microphone, colloquially called a mic or mike (), is a transducer that converts sound into an electrical signal. Microphones are used in many applications such as telephones, hearing aids, public address systems for concert halls and public ...

inserted directly in the antenna wire. This meant that the full transmitter power flowed through the microphone, and even using water cooling, the power handling ability of the microphones severely limited the power of the transmissions. Ultimately only a small number of large and powerful Alexanderson alternator

An Alexanderson alternator is a rotating machine invented by Ernst Alexanderson in 1904 for the generation of high-frequency alternating current for use as a radio transmitter. It was one of the first devices capable of generating the continuou ...

s would be developed. However, they would be almost exclusively used for long-range radiotelegraph communication, and occasionally for radiotelephone experimentation, but were never used for general broadcasting.

Arc transmitters

Almost all of the continuous wave AM transmissions made prior to 1915 were made by versions of thearc converter

The arc converter, sometimes called the arc transmitter, or Poulsen arc after Danish engineer Valdemar Poulsen who invented it in 1903, was a variety of spark transmitter used in early wireless telegraphy. The arc converter used an electric arc to ...

transmitter, which had been initially developed by Valdemar Poulsen

Valdemar Poulsen (23 November 1869 – 23 July 1942) was a Danish engineer who made significant contributions to early radio technology. He developed a magnetic wire recorder called the telegraphone in 1898 and the first continuous wave radio ...

in 1903. Arc transmitters worked by producing a pulsating electrical arc in an enclosed hydrogen atmosphere. They were much more compact than alternator transmitters, and could operate on somewhat higher transmitting frequencies. However, they suffered from some of the same deficiencies. The lack of any means to amplify electrical currents meant that, like the alternator transmitters, modulation was usually accomplished by a microphone inserted directly in the antenna wire, which again resulted in overheating issues, even with the use of water-cooled microphones. Thus, transmitter powers tended to be limited. The arc was also somewhat unstable, which reduced audio quality. Experimenters who used arc transmitters for their radiotelephone research included Ernst Ruhmer

Ernst Walter Ruhmer (15 April 1878 – 8 April 1913) was a German physicist. He was best known for investigating practical applications making use of the light-sensitivity properties of selenium, which he employed in developing wireless telephony u ...

, Quirino Majorana

Quirino Majorana (28 October 1871 – 31 July 1957) was an Italian experimental physicist who investigated a wide range of phenomena during his long career as professor of physics at the Universities of Rome, Turin (1916–1921), and Bologna (192 ...

, Charles "Doc" Herrold, and Lee de Forest

Lee de Forest (August 26, 1873 – June 30, 1961) was an American inventor and a fundamentally important early pioneer in electronics. He invented the first electronic device for controlling current flow; the three-element "Audion" triode va ...

.

Vacuum tube transmitters

Advances invacuum tube

A vacuum tube, electron tube, valve (British usage), or tube (North America), is a device that controls electric current flow in a high vacuum between electrodes to which an electric voltage, potential difference has been applied.

The type kn ...

technology (called "valves" in British usage), especially after around 1915, revolutionized radio technology. Vacuum tube devices could be used to amplify electrical currents, which overcame the overheating issues of needing to insert microphones directly in the transmission antenna circuit. Vacuum tube transmitters also provided high-quality AM signals, and could operate on higher transmitting frequencies than alternator and arc transmitters. Non-governmental radio transmissions were prohibited in many countries during World War I, but AM radiotelephony technology advanced greatly due to wartime research, and after the war the availability of tubes sparked a great increase in the number of amateur radio stations experimenting with AM transmission of news or music. Vacuum tubes remained the central technology of radio for 40 years, until transistor

upright=1.4, gate (G), body (B), source (S) and drain (D) terminals. The gate is separated from the body by an insulating layer (pink).

A transistor is a semiconductor device used to Electronic amplifier, amplify or electronic switch, switch e ...

s began to dominate in the late 1950s, and are still used in the highest power broadcast transmitters.

Receivers

Unlike telegraph and telephone systems, which used completely different types of equipment, most radio receivers were equally suitable for both radiotelegraph and radiotelephone reception. In 1903 and 1904 theelectrolytic detector

The electrolytic detector, or liquid barretter, was a type of detector (demodulator) used in early radio receivers. First used by Canadian radio researcher Reginald Fessenden in 1903, it was used until about 1913, after which it was superseded b ...

and thermionic diode

A diode is a two-terminal electronic component that conducts current primarily in one direction (asymmetric conductance); it has low (ideally zero) resistance in one direction, and high (ideally infinite) resistance in the other.

A diode ...

(Fleming valve

The Fleming valve, also called the Fleming oscillation valve, was a thermionic valve or vacuum tube invented in 1904 by English physicist John Ambrose Fleming as a detector for early radio receivers used in electromagnetic wireless telegraphy. ...

) were invented by Reginald Fessenden

Reginald Aubrey Fessenden (October 6, 1866 – July 22, 1932) was a Canadian-born inventor, who did a majority of his work in the United States and also claimed U.S. citizenship through his American-born father. During his life he received hundre ...

and John Ambrose Fleming

Sir John Ambrose Fleming FRS (29 November 1849 – 18 April 1945) was an English electrical engineer and physicist who invented the first thermionic valve or vacuum tube, designed the radio transmitter with which the first transatlantic rad ...

, respectively. Most important, in 1904–1906 the crystal detector

A crystal detector is an obsolete electronic component used in some early 20th century radio receivers that consists of a piece of crystalline mineral which rectifies the alternating current radio signal. It was employed as a detector (demod ...

, the simplest and cheapest AM detector, was developed by G. W. Pickard. Homemade crystal radio

A crystal radio receiver, also called a crystal set, is a simple radio receiver, popular in the early days of radio. It uses only the power of the received radio signal to produce sound, needing no external power. It is named for its most impo ...

s spread rapidly during the next 15 years, providing ready audiences for the first radio broadcasts. One limitation of crystals sets was the lack of amplifying the signals, so listeners had to use earphone

Headphones are a pair of small loudspeaker drivers worn on or around the head over a user's ears. They are electroacoustic transducers, which convert an electrical signal to a corresponding sound. Headphones let a single user listen to an au ...

s, and it required the development of vacuum-tube receivers before loudspeaker

A loudspeaker (commonly referred to as a speaker or speaker driver) is an electroacoustic transducer that converts an electrical audio signal into a corresponding sound. A ''speaker system'', also often simply referred to as a "speaker" or " ...

s could be used. The dynamic cone loudspeaker, invented in 1924, greatly improved audio frequency response

In signal processing and electronics, the frequency response of a system is the quantitative measure of the magnitude and phase of the output as a function of input frequency. The frequency response is widely used in the design and analysis of sy ...

over the previous horn speakers, allowing music to be reproduced with good fidelity.McNicol, Donald (1946) ''Radio's Conquest of Space'', p. 336-340/ref> AM radio offered the highest sound quality available in a home audio device prior to the introduction of the high-fidelity,

long-playing

The LP (from "long playing" or "long play") is an analog sound storage medium, a phonograph record format characterized by: a speed of rpm; a 12- or 10-inch (30- or 25-cm) diameter; use of the "microgroove" groove specification; and a ...

record in the late 1940s.

Listening habits changed in the 1960s due to the introduction of the revolutionary transistor radio

A transistor radio is a small portable radio receiver that uses transistor-based circuitry. Following the invention of the transistor in 1947—which revolutionized the field of consumer electronics by introducing small but powerful, convenien ...

, (Regency TR-1, the first transistor radio released December 1954) which was made possible by the invention of the transistor

upright=1.4, gate (G), body (B), source (S) and drain (D) terminals. The gate is separated from the body by an insulating layer (pink).

A transistor is a semiconductor device used to Electronic amplifier, amplify or electronic switch, switch e ...

in 1948. (The transistor was invented at Bell labs and released in June 1948). Their compact size — small enough to fit in a shirt pocket — and lower power requirements, compared to vacuum tubes, meant that for the first time radio receivers were readily portable. The transistor radio became the most widely used communication device in history, with billions manufactured by the 1970s. Radio became a ubiquitous "companion medium" which people could take with them anywhere they went.

Early experimental broadcasts

The demarcation between what is considered "experimental" and "organized" broadcasting is largely arbitrary. Listed below are some of the early AM radio broadcasts, which, due to their irregular schedules and limited purposes, can be classified as "experimental": * Christmas Eve 1906 Until the early 1930s, it was generally accepted thatLee de Forest

Lee de Forest (August 26, 1873 – June 30, 1961) was an American inventor and a fundamentally important early pioneer in electronics. He invented the first electronic device for controlling current flow; the three-element "Audion" triode va ...

's series of demonstration broadcasts begun in 1907 were the first transmissions of music and entertainment by radio. However, in 1932 an article prepared by Samuel M. Kintner, a former associate of Reginald Fessenden, asserted that Fessenden had actually conducted two earlier broadcasts. This claim was based solely on information included in a January 29, 1932, letter that Fessenden had sent to Kintner. (Fessenden subsequently died five months before Kintner's article appeared). In his letter, Fessenden reported that, on the evening of December 24, 1906 (Christmas Eve

Christmas Eve is the evening or entire day before Christmas Day, the festival commemorating the birth of Jesus. Christmas Day is observed around the world, and Christmas Eve is widely observed as a full or partial holiday in anticipation ...

), he had made the first of two broadcasts of music and entertainment to a general audience, using the alternator-transmitter at Brant Rock, Massachusetts. Fessenden remembered producing a short program that included playing a phonograph record, followed by his playing the violin and singing, and closing with a bible reading. He also stated that a second short program was broadcast on December 31 (New Year's Eve

In the Gregorian calendar, New Year's Eve, also known as Old Year's Day or Saint Sylvester's Day in many countries, is the evening or the entire day of the last day of the year, on 31 December. The last day of the year is commonly referred to ...

). The intended audience for both transmissions was primarily shipboard radio operators along the Atlantic seaboard. Fessenden claimed these two programs had been widely publicized in advance, with the Christmas Eve broadcast heard "as far down" as Norfolk, Virginia, while the New Year Eve's broadcast had been received in the West Indies. However, extensive efforts to verify Fessenden's claim during both the 50th and 100th anniversaries of the claimed broadcasts, which included reviewing ships' radio log accounts and other contemporary sources, have so far failed to confirm that these reported holiday broadcasts actually took place.

* 1907-1912 Lee de Forest conducted multiple test broadcasts beginning in 1907, and was widely quoted promoting the potential of organized radio broadcasting. Using a series of arc transmitters, he made his first entertainment broadcast in February 1907, transmitting electronic telharmonium

The Telharmonium (also known as the Dynamophone) was an early electrical organ, developed by Thaddeus Cahill c. 1896 and patented in 1897.

, filed 1896-02-04.

The electrical signal from the Telharmonium was transmitted over wires; it was hear ...

music from his Parker Building laboratory station in New York City. This was followed by tests that included, in the fall, Eugenia Farrar

Eugenia Farrar (1875—1966), whose full name was Ada Eugenia Hildegard von Boos Farrar, was a mezzo-soprano singer and philanthropist. She was born in Sweden and lived most of her life in New York City. In the fall of 1907 she gave what is comm ...

singing "I Love You Truly

"I Love You Truly" is a parlor song written by Carrie Jacobs-Bond. Since its publication in 1901 it has been sung at weddings, recorded by numerous artists over many decades, and heard on film and television.

History

Carrie Jacobs-Bond began to ...

" and "Just Awearyin' for You

"Just Awearyin' for You" is a parlor song, one of that genre's all-time hits.

The lyrics were written by Frank Lebby Stanton and published in his ''Songs of the Soil'' (1894). The tune was composed by Carrie Jacobs-Bond#Personal life, Carrie ...

". Additional promotional events in New York included live performances by famous Metropolitan Opera stars such as Mariette Mazarin and Enrico Caruso

Enrico Caruso (, , ; 25 February 1873 – 2 August 1921) was an Italian operatic first lyrical tenor then dramatic tenor. He sang to great acclaim at the major opera houses of Europe and the Americas, appearing in a wide variety of roles (74) ...

. He also broadcast phonograph music from the Eiffel Tower

The Eiffel Tower ( ; french: links=yes, tour Eiffel ) is a wrought-iron lattice tower on the Champ de Mars in Paris, France. It is named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built the tower.

Locally nicknamed "'' ...

in Paris. His company equipped the U.S. Navy's Great White Fleet

The Great White Fleet was the popular nickname for the group of United States Navy battleships which completed a journey around the globe from December 16, 1907 to February 22, 1909 by order of President Theodore Roosevelt. Its mission was t ...

with experimental arc radiotelephones for their 1908 around-the-world cruise, and the operators broadcast phonograph music as the ships entered ports like San Francisco and Honolulu.

* June 1910 In a June 23, 1910, notarized letter that was published in a catalog produced by the Electro Importing Company of New York, Charles "Doc" Herrold reported that, using one of that company's spark coils to create a "high frequency spark" transmitter, he had successfully broadcast "wireless phone concerts to local amateur wireless men". Herrold lived in San Jose, California.

* 1913 Robert Goldschmidt began experimental radiotelephone transmissions from the Laeken station, near Brussels, Belgium, and by March 13, 1914 the tests had been heard as far away as the Eiffel Tower in Paris.''"De la T.S.F. au Congo-Belge et de l'école pratique de Laeken aux concerts radiophoniques"'' (Wireless in the Belgian Congo and from the Laeken Training School to Radio Concerts) by Bruno Brasseur, ''Cahiers d'Histoire de la Radiodiffusion'', Number 118, October-December 2013.

* 1914-1919 "University of Wisconsin electrical engineering Professor Edward Bennett sets up a personal radio transmitter on campus and in June 1915 is issued an Experimental radio station license with the call sign 9XM. Activities included regular Morse Code broadcasts of weather forecasts and sending game reports for a Wisconsin-Ohio State basketball game on February 17, 1917.

* January 15, 1920 Broadcasting in the United Kingdom began with impromptu news and phonograph music over 2MT, the 15 kW experimental tube transmitter at Marconi's factory in Chelmsford

Chelmsford () is a city in the City of Chelmsford district in the county of Essex, England. It is the county town of Essex and one of three cities in the county, along with Southend-on-Sea and Colchester. It is located north-east of London a ...

, Essex, at a frequency of 120 kHz. On June 15, 1920, the ''Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper and news websitePeter Wilb"Paul Dacre of the Daily Mail: The man who hates liberal Britain", ''New Statesman'', 19 December 2013 (online version: 2 January 2014) publish ...

'' newspaper sponsored the first scheduled British radio concert, by the famed Australian opera diva Nellie Melba

Dame Nellie Melba (born Helen Porter Mitchell; 19 May 186123 February 1931) was an Australian operatic dramatic coloratura soprano (three octaves). She became one of the most famous singers of the late Victorian era and the early 20th century, ...

. This transmission was heard throughout much of Europe, including in Berlin, Paris, The Hague, Madrid, Spain, and Sweden. Chelmsford continued broadcasting concerts with noted performers. A few months later, in spite of burgeoning popularity, the government ended the broadcasts, due to complaints that the station's longwave signal was interfering with more important communication, in particular military aircraft radio.

Organized broadcasting

Following World War I, the number of stations providing a regular broadcasting service greatly increased, primarily due to advances in vacuum-tube technology. In response to ongoing activities, government regulators eventually codified standards for which stations could make broadcasts intended for the general public, for example, in the United States formal recognition of a "broadcasting service" came with the establishment of regulations effective December 1, 1921, and Canadian authorities created a separate category of "radio-telephone broadcasting stations" in April 1922. However, there were numerous cases of entertainment broadcasts being presented on a regular schedule before their formal recognition by government regulators. Some early examples include:

* July 21, 1912 The first person to transmit entertainment broadcasts on a regular schedule appears to have been Charles "Doc" Herrold, who inaugurated weekly programs, using an arc transmitter, from his Wireless School station in San Jose, California. The broadcasts continued until the station was shut down due to the entrance of the United States into World War I in April 1917.

* March 28, 1914 The Laeken station in Belgium, under the oversight of Robert Goldschmidt, inaugurated a weekly series of concerts, transmitted at 5:00 p.m. on Saturdays. These continued for about four months until July, and were ended by the start of World War I. In August 1914 the Laeken facilities were destroyed, to keep them from falling into the hands of invading German troops.

* November 1916 De Forest perfected "Oscillion" power vacuum tubes, capable of use in radio transmitters, and inaugurated daily broadcasts of entertainment and news from his New York "Highbridge" station, 2XG. This station also suspended operations in April 1917 due to the prohibition of civilian radio transmissions following the United States' entry into World War I. Its most publicized program was the broadcasting of election results for the Hughes-Wilson presidential election on November 7, 1916, with updates provided by wire from the ''

Following World War I, the number of stations providing a regular broadcasting service greatly increased, primarily due to advances in vacuum-tube technology. In response to ongoing activities, government regulators eventually codified standards for which stations could make broadcasts intended for the general public, for example, in the United States formal recognition of a "broadcasting service" came with the establishment of regulations effective December 1, 1921, and Canadian authorities created a separate category of "radio-telephone broadcasting stations" in April 1922. However, there were numerous cases of entertainment broadcasts being presented on a regular schedule before their formal recognition by government regulators. Some early examples include:

* July 21, 1912 The first person to transmit entertainment broadcasts on a regular schedule appears to have been Charles "Doc" Herrold, who inaugurated weekly programs, using an arc transmitter, from his Wireless School station in San Jose, California. The broadcasts continued until the station was shut down due to the entrance of the United States into World War I in April 1917.

* March 28, 1914 The Laeken station in Belgium, under the oversight of Robert Goldschmidt, inaugurated a weekly series of concerts, transmitted at 5:00 p.m. on Saturdays. These continued for about four months until July, and were ended by the start of World War I. In August 1914 the Laeken facilities were destroyed, to keep them from falling into the hands of invading German troops.

* November 1916 De Forest perfected "Oscillion" power vacuum tubes, capable of use in radio transmitters, and inaugurated daily broadcasts of entertainment and news from his New York "Highbridge" station, 2XG. This station also suspended operations in April 1917 due to the prohibition of civilian radio transmissions following the United States' entry into World War I. Its most publicized program was the broadcasting of election results for the Hughes-Wilson presidential election on November 7, 1916, with updates provided by wire from the ''New York American

:''Includes coverage of New York Journal-American and its predecessors New York Journal, The Journal, New York American and New York Evening Journal''

The ''New York Journal-American'' was a daily newspaper published in New York City from 1937 t ...

'' offices. An estimated 7,000 radio listeners as far as 200 miles (320 kilometers) from New York heard election returns interspersed with patriotic music."Election Returns Flashed by Radio to 7,000 Amateurs"''The Electrical Experimenter'', January 1917, page 650. (archive.org) * April 17, 1919 Shortly after the end of World War I, F. S. McCullough at the Glenn L. Martin aviation plant in Cleveland, Ohio, began a weekly series of phonograph concerts. However, the broadcasts were soon suspended, due to interference complaints by the U.S. Navy. * November 6, 1919 The first scheduled (pre-announced in the press) Dutch radio broadcast was made by Nederlandsche Radio Industrie station

PCGG

PCGG (also known as the Dutch Concerts station) was a radio station located at The Hague in the Netherlands, which began broadcasting a regular schedule of entertainment programmes on 6 November 1919. The station was established by engineer Hanso ...

at The Hague, which began regular concerts broadcasts. It found it had a large audience outside the Netherlands, mostly in the UK. (Rather than true AM signals, at least initially this station used a form of narrowband FM, which required receivers to be slightly detuned to receive the signals using slope detection.)

* Late 1919 De Forest's New York station, 2XG, returned to the airwaves in late 1919 after having to suspend operations during World War I. The station continued to operate until early 1920, when it was shut down because the transmitter had been moved to a new location without permission.

* May 20, 1920 Experimental Canadian Marconi station XWA (later CFCF, deleted in 2010 as CINW) in Montreal began regular broadcasts, and claims status as the first commercial broadcaster in the world.

* June 1920 De Forest transferred 2XG's former transmitter to San Francisco, California, where it was relicensed as 6XC, the "California Theater station". By June 1920 the station began transmitting daily concerts. De Forest later stated that this was the "first radio-telephone station devoted solely" to broadcasting to the public.

* August 20, 1920 On this date the ''Detroit News

''The Detroit News'' is one of the two major newspapers in the U.S. city of Detroit, Michigan. The paper began in 1873, when it rented space in the rival ''Detroit Free Press'' building. ''The News'' absorbed the ''Detroit Tribune'' on Februar ...

'' began daily transmissions over station 8MK (later WWJ), located in the newspaper's headquarters building. The newspaper began extensively publicizing station operations beginning on August 31, 1920, with a special program featuring primary election returns. Station management later claimed the title of being where "commercial radio broadcasting began".

* November 2, 1920 Beginning on October 17, 1919, Westinghouse engineer Frank Conrad

Frank Conrad (May 4, 1874 – December 10, 1941) was an electrical engineer, best known for radio development, including his work as a pioneer broadcaster. He worked for the Westinghouse Electrical and Manufacturing Company in East Pittsburgh, P ...

began broadcasting recorded and live music on a semi-regular schedule from his home station, 8XK in Wilkinsburg, Pennsylvania. This inspired his employer to begin its own ambitious service at the company's headquarters in East Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Operations began, initially with the call sign 8ZZ, with an election night program featuring election returns on November 2, 1920. As KDKA, the station adopted a daily schedule beginning on December 21, 1920. This station is another contender for the title of "first commercial station".

* January 3, 1921 University of Wisconsin - Regular schedule of voice broadcasts begin; 9XM is the first radio station in the United States to provide the weather forecast by voice (Jan. 3). In September, farm market broadcasts are added. On Nov. 1, 9XM carries the first live broadcast of a symphony orchestra -- the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra from the UW Armory using a single microphone.

Radio networks

Because most longwave radio frequencies were used for international radiotelegraph communication, a majority of early broadcasting stations operated on mediumwave frequencies, whose limited range generally restricted them to local audiences. One method for overcoming this limitation, as well as a method for sharing program costs, was to create radio

Because most longwave radio frequencies were used for international radiotelegraph communication, a majority of early broadcasting stations operated on mediumwave frequencies, whose limited range generally restricted them to local audiences. One method for overcoming this limitation, as well as a method for sharing program costs, was to create radio networks

Network, networking and networked may refer to:

Science and technology

* Network theory, the study of graphs as a representation of relations between discrete objects

* Network science, an academic field that studies complex networks

Mathematics

...

, linking stations together with telephone lines to provide a nationwide audience.

United States

In the U.S., theAmerican Telephone and Telegraph Company

AT&T Inc. is an American multinational telecommunications holding company headquartered at Whitacre Tower in Downtown Dallas, Texas. It is the world's largest telecommunications company by revenue and the third largest provider of mobile tel ...

(AT&T) was the first organization to create a radio network, and also to promote commercial advertising, which it called "toll" broadcasting. Its flagship station, WEAF (now WFAN) in New York City, sold blocks of airtime to commercial sponsors that developed entertainment shows containing commercial messages. AT&T held a monopoly on quality telephone lines, and by 1924 had linked 12 stations in Eastern cities into a "chain". The Radio Corporation of America

The RCA Corporation was a major American electronics company, which was founded as the Radio Corporation of America in 1919. It was initially a patent trust owned by General Electric (GE), Westinghouse, AT&T Corporation and United Fruit Comp ...

(RCA), General Electric

General Electric Company (GE) is an American multinational conglomerate founded in 1892, and incorporated in New York state and headquartered in Boston. The company operated in sectors including healthcare, aviation, power, renewable energ ...

and Westinghouse organized a competing network around its own flagship station, RCA's WJZ (now WABC) in New York City, but were hampered by AT&T's refusal to lease connecting lines or allow them to sell airtime. In 1926 AT&T sold its radio operations to RCA, which used them to form the nucleus of the new NBC

The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) is an Television in the United States, American English-language Commercial broadcasting, commercial television network, broadcast television and radio network. The flagship property of the NBC Enterta ...

network. By the 1930s, most of the major radio stations in the country were affiliated with networks owned by two companies, NBC and CBS

CBS Broadcasting Inc., commonly shortened to CBS, the abbreviation of its former legal name Columbia Broadcasting System, is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the CBS Entertainmen ...

. In 1934, a third national network, the Mutual Radio Network

The Mutual Broadcasting System (commonly referred to simply as Mutual; sometimes referred to as MBS, Mutual Radio or the Mutual Radio Network) was an American commercial radio network in operation from 1934 to 1999. In the golden age of U.S. rad ...

was formed as a cooperative owned by its stations.

United Kingdom

A second country which quickly adopted network programming was the United Kingdom, and its national network quickly became a prototype for a state-managed monopoly of broadcasting. A rising interest in radio broadcasting by the British public pressured the government to reintroduce the service, following its suspension in 1920. However, the government also wanted to avoid what it termed the "chaotic" U.S. experience of allowing large numbers of stations to operate with few restrictions. There were also concerns about broadcasting becoming dominated by the Marconi company. Arrangements were made for six large radio manufacturers to form a consortium, the

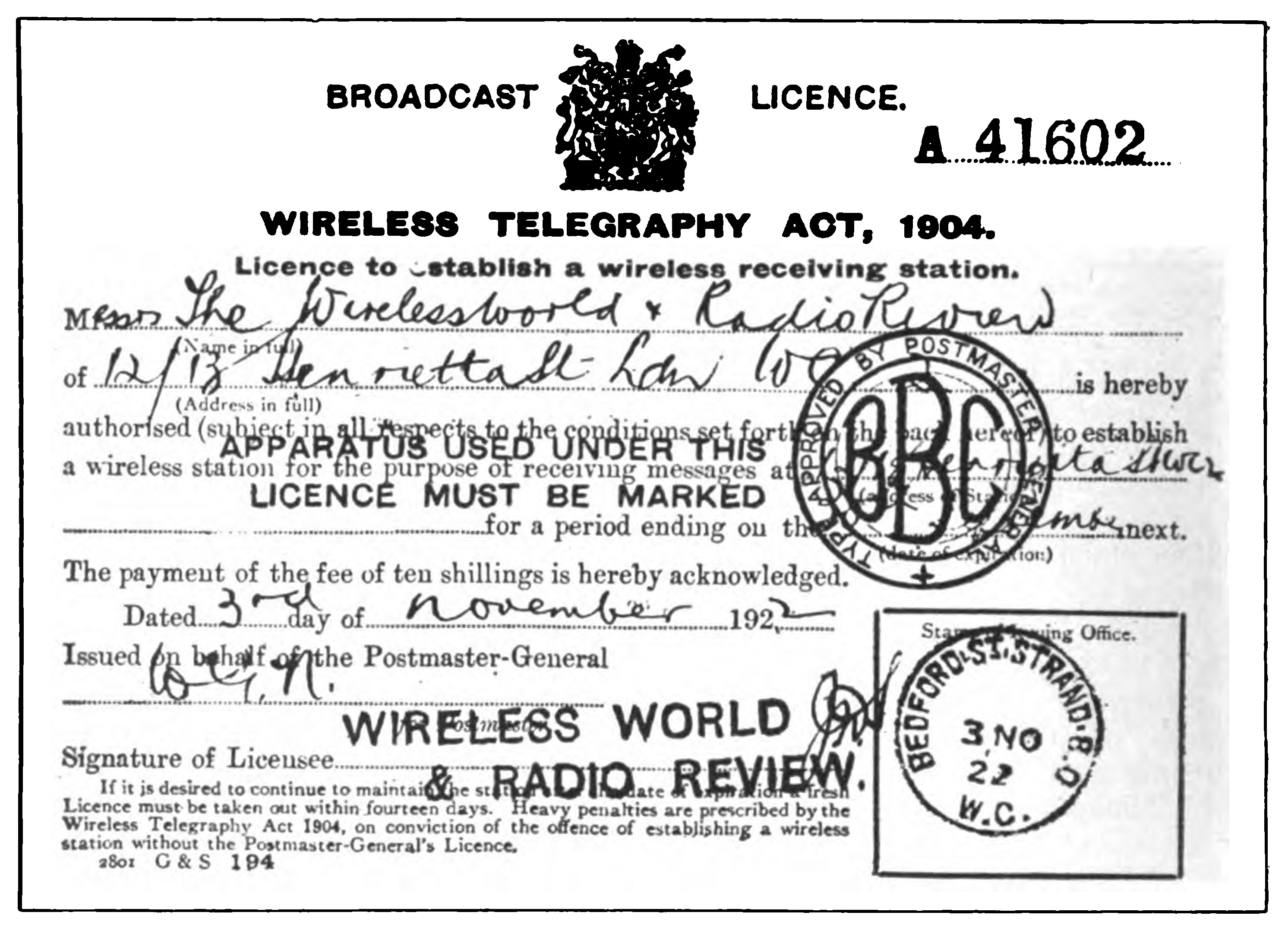

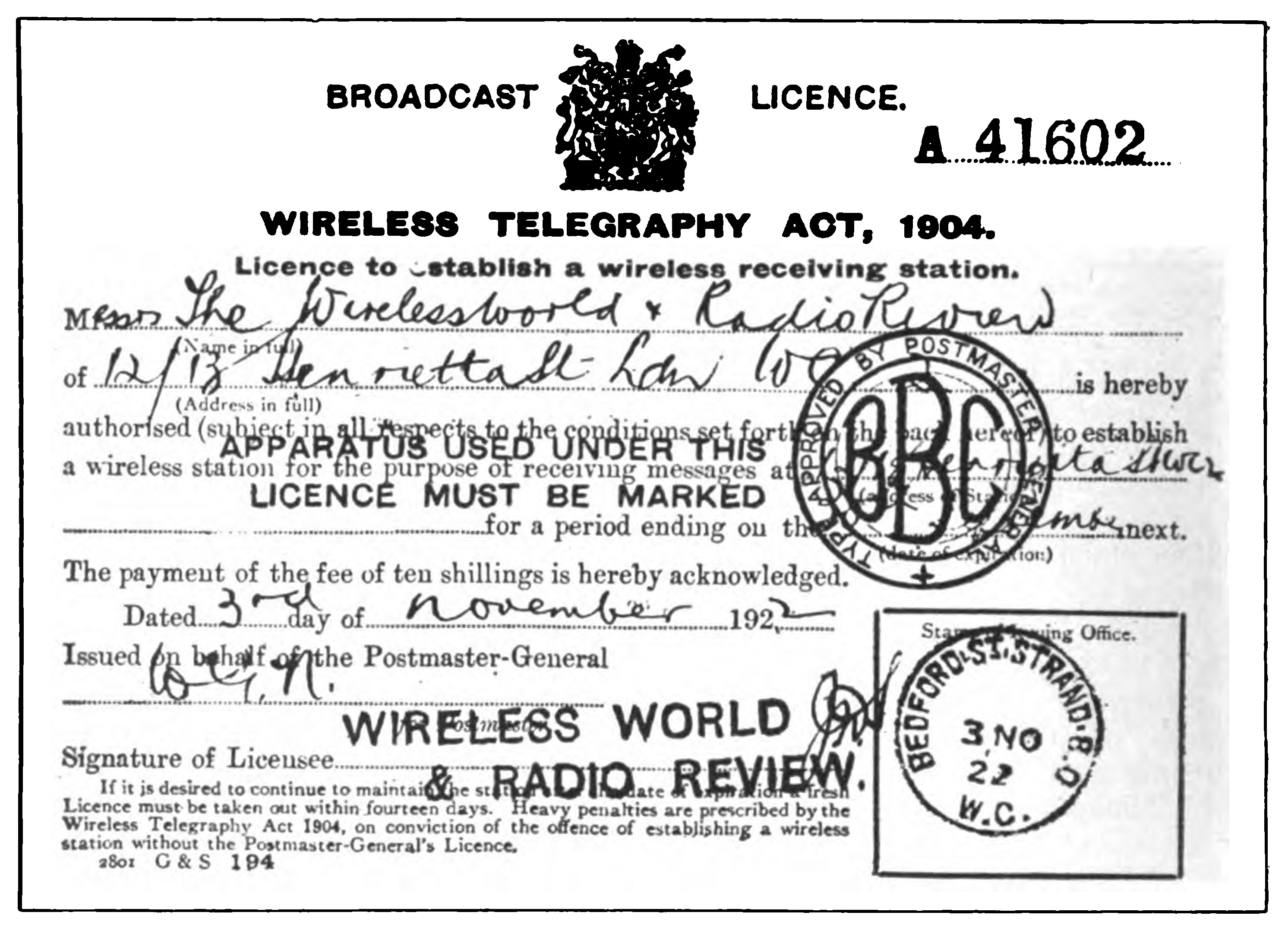

A second country which quickly adopted network programming was the United Kingdom, and its national network quickly became a prototype for a state-managed monopoly of broadcasting. A rising interest in radio broadcasting by the British public pressured the government to reintroduce the service, following its suspension in 1920. However, the government also wanted to avoid what it termed the "chaotic" U.S. experience of allowing large numbers of stations to operate with few restrictions. There were also concerns about broadcasting becoming dominated by the Marconi company. Arrangements were made for six large radio manufacturers to form a consortium, the British Broadcasting Company

The British Broadcasting Company Ltd. (BBC) was a short-lived British commercial broadcasting company formed on 18 October 1922 by British and American electrical companies doing business in the United Kingdom. Licensed by the British Genera ...

(BBC), established on 18 October 1922, which was given a monopoly on broadcasting. This enterprise was supported by a tax on radio sets sales, plus an annual license fee on receivers, collected by the Post Office. Initially the eight stations were allowed regional autonomy. In 1927, the original broadcasting organization was replaced by a government chartered British Broadcasting Corporation #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

. an independent nonprofit supported solely by a 10 shilling receiver license

A television licence or broadcast receiving licence is a payment required in many countries for the reception of Television broadcasting, television broadcasts, or the possession of a television set where some broadcasts are funded in full or ...

fee. A mixture of populist and high brow programmes were carried by the National

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, ce ...

and Regional

In geography, regions, otherwise referred to as zones, lands or territories, are areas that are broadly divided by physical characteristics (physical geography), human impact characteristics (human geography), and the interaction of humanity and t ...

networks.

"Golden Age of Radio"

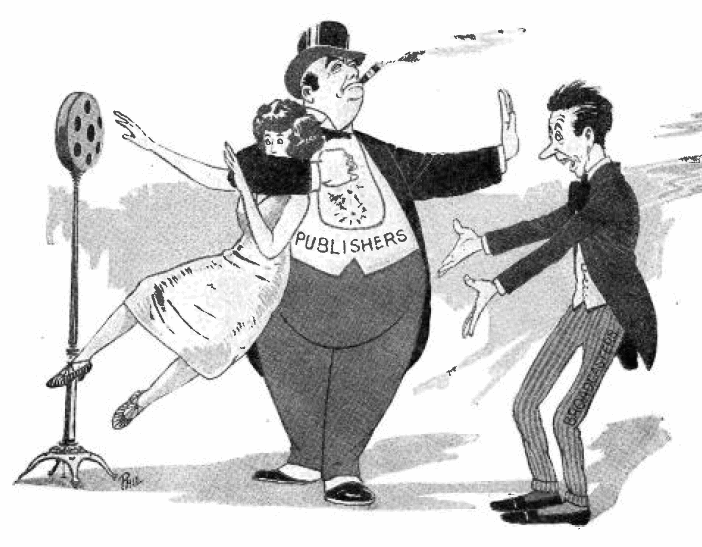

The period from the early 1920s through the 1940s is often called the "Golden Age of Radio". During this period AM radio was the main source of home entertainment, until it was replaced by television. For the first time entertainment was provided from outside the home, replacing traditional forms of entertainment such as oral storytelling and music from family members. New forms were created, including

The period from the early 1920s through the 1940s is often called the "Golden Age of Radio". During this period AM radio was the main source of home entertainment, until it was replaced by television. For the first time entertainment was provided from outside the home, replacing traditional forms of entertainment such as oral storytelling and music from family members. New forms were created, including radio play

Radio drama (or audio drama, audio play, radio play, radio theatre, or audio theatre) is a dramatized, purely acoustic performance. With no visual component, radio drama depends on dialogue, music and sound effects to help the listener imagine t ...

s, mystery serials, soap opera

A soap opera, or ''soap'' for short, is a typically long-running radio or television serial, frequently characterized by melodrama, ensemble casts, and sentimentality. The term "soap opera" originated from radio dramas originally being sponsored ...

s, quiz show

A game show is a genre of broadcast viewing entertainment (radio, television, internet, stage or other) where contestants compete for a reward. These programs can either be participatory or demonstrative and are typically directed by a host, sh ...

s, variety hours, situation comedies

A sitcom, a portmanteau of situation comedy, or situational comedy, is a genre of comedy centered on a fixed set of characters who mostly carry over from episode to episode. Sitcoms can be contrasted with sketch comedy, where a troupe may use new ...

and children's show

Children's television series (or children's television shows) are television programs designed for children, normally scheduled for broadcast during the morning and afternoon when children are awake. They can sometimes run during the early evenin ...

s. Radio news, including remote reporting, allowed listeners to be vicariously present at notable events.

Radio greatly eased the isolation of rural life. Political officials could now speak directly to millions of citizens. One of the first to take advantage of this was American president Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, who became famous for his fireside chats

The fireside chats were a series of evening radio addresses given by Franklin D. Roosevelt, the 32nd President of the United States, between 1933 and 1944. Roosevelt spoke with familiarity to millions of Americans about recovery from the Great De ...

during the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

. However, broadcasting also provided the means to use propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

as a powerful government tool, and contributed to the rise of fascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

and communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

ideologies.

Decline in popularity

In the 1940s two new broadcast media,FM radio

FM broadcasting is a method of radio broadcasting using frequency modulation (FM). Invented in 1933 by American engineer Edwin Armstrong, wide-band FM is used worldwide to provide high fidelity sound over broadcast radio. FM broadcasting is cap ...

and television

Television, sometimes shortened to TV, is a telecommunication medium for transmitting moving images and sound. The term can refer to a television set, or the medium of television transmission. Television is a mass medium for advertisin ...

, began to provide extensive competition with the established broadcasting services. The AM radio industry suffered a serious loss of audience and advertising revenue, and coped by developing new strategies. Network broadcasting gave way to format

Format may refer to:

Printing and visual media

* Text formatting, the typesetting of text elements

* Paper formats, or paper size standards

* Newspaper format, the size of the paper page

Computing

* File format, particular way that informatio ...

broadcasting: instead of broadcasting the same programs all over the country, stations individually adopted specialized formats which appealed to different audiences, such as regional and local news, sports, "talk" programs, and programs targeted at minorities. Instead of live music, most stations began playing less expensive recorded music.

In the late 1970s, spurred by the exodus of musical programming to FM stations, the AM radio industry in the United States developed technology for broadcasting in stereo

Stereophonic sound, or more commonly stereo, is a method of sound reproduction that recreates a multi-directional, 3-dimensional audible perspective. This is usually achieved by using two independent audio channels through a configuration ...

. Other nations adopted AM stereo, most commonly choosing Motorola's C-QUAM, and in 1993 the United States also made the C-QUAM system its standard, after a period allowing four different standards to compete. The selection of a single standard improved acceptance of AM stereo,"AM Stereo Broadcasting"(fcc.gov) however overall there was limited adoption of AM stereo worldwide, and interest declined after 1990. With the continued migration of AM stations away from music to news, sports, and talk formats, receiver manufacturers saw little reason to adopt the more expensive stereo tuners, and thus radio stations have little incentive to upgrade to stereo transmission. In countries where the use of directional antennas is common, such as the United States, transmitter sites consisting of multiple towers often occupy large tracts of land that have significantly increased in value over the decades, to the point that the value of land exceeds that of the station itself. This sometimes results in the sale of the transmitter site, with the station relocating to a more distant shared site using significantly less power, or completely shutting down operations. The ongoing development of alternative transmission systems, including Digital Audio Broadcasting (DAB), satellite radio, and HD (digital) radio, continued the decline of the popularity of the traditional broadcast technologies. These new options, including the introduction of Internet streaming, particularly resulted in the reduction of shortwave transmissions, as international broadcasters found ways to reach their audiences more easily.

AM band revitalization efforts in the United States

The FM broadcast band was established in 1941 in the United States, and at the time some suggested that the AM band would soon be eliminated. In 1948 wide-band FM's inventor,Edwin H. Armstrong

Edwin Howard Armstrong (December 18, 1890 – February 1, 1954) was an American electrical engineer and inventor, who developed FM (frequency modulation) radio and the superheterodyne receiver system. He held 42 patents and received numerous awar ...

, predicted that "The broadcasters will set up FM stations which will parallel, carry the same program, as over their AM stations... eventually the day will come, of course, when we will no longer have to build receivers capable of receiving both types of transmission, and then the AM transmitters will disappear." However, FM stations actually struggled for many decades, and it wasn't until 1978 that FM listenership surpassed that of AM stations. Since then the AM band's share of the audience has continued to decline.

Fairness Doctrine repeal

The elimination of theFairness Doctrine

The fairness doctrine of the United States Federal Communications Commission (FCC), introduced in 1949, was a policy that required the holders of broadcast licenses both to present controversial issues of public importance and to do so in a manne ...

requirement in 1987 meant that talk shows, which were commonly carried by AM stations, could adopt a more focused presentation on controversial topics, without the distraction of having to provide airtime for any contrasting opinions. In addition, satellite distribution made it possible for programs to be economically carried on a national scale. The introduction of nationwide talk shows, most prominently Rush Limbaugh

Rush Hudson Limbaugh III ( ; January 12, 1951 – February 17, 2021) was an American conservative political commentator who was the host of '' The Rush Limbaugh Show'', which first aired in 1984 and was nationally syndicated on AM and FM r ...

's beginning in 1988, was sometimes credited with "saving AM radio". However, these stations tended to attract older listeners who were of lesser interest to advertisers, and AM radio's audience share continued to erode.

AM stereo and AMAX standards

In 1961, the FCC adopted a single standard for FM stereo transmissions, which was widely credited with enhancing FM's popularity. Developing the technology for AM broadcasting in stereo was challenging due to the need to limit the transmissions to a 20 kHz bandwidth, while also making the transmissions backward compatible with existing non-stereo receivers. In 1990, the FCC authorized an AM stereo standard developed by Magnavox, but two years later revised its decision to instead approve four competing implementations, saying it would "let the marketplace decide" which was best. The lack of a common standard resulted in consumer confusion and increased the complexity and cost of producing AM stereo receivers. In 1993, the FCC again revised its policy, by selecting