A. Sibiryakov (icebreaker) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Alexander Sibiryakov'' (Russian ''Александр Сибиряков'') was a steamship that was built in Scotland in 1909 as ''Bellaventure'', and was originally a seal hunting ship in Newfoundland. In 1917 the Russian government bought her to be an

On 2 April 1914 ''Bellaventure'', commanded by Captain

On 2 April 1914 ''Bellaventure'', commanded by Captain

icebreaker

An icebreaker is a special-purpose ship or boat designed to move and navigate through ice-covered waters, and provide safe waterways for other boats and ships. Although the term usually refers to ice-breaking ships, it may also refer to smaller ...

. She served the RSFSR and Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

until 1942, when she was sunk by enemy action. The ship gave notable service in the Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

n Arctic during the 1930s.

The ship was recorded as ''Bellaventure'' until at least 1920. By 1927 she had been renamed ''Александр Сибиряков''. In the Latin alphabet

The Latin alphabet or Roman alphabet is the collection of letters originally used by the ancient Romans to write the Latin language. Largely unaltered with the exception of extensions (such as diacritics), it used to write English and th ...

her name was rendered ''Alexander Sibiriakov'' until at least 1935. This had been changed to ''Alexander Sibiryakov'' by 1939.

Building

In 1908 A Harvey & Co of St John's, Newfoundland ordered a pair of ships from shipbuilders inGlasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

, Scotland. D&W Henderson Ltd built ''Bellaventure'', launching her on 23 November 1908. Napier and Miller

Napier & Miller Ltd. (also Messrs Napier & Miller) were Scottish shipbuilders based at Old Kilpatrick, Glasgow, Scotland.

Company history

The company was founded in 1898 at a yard at Yoker. In 1906 it moved to a new site a few miles downriver at ...

built her sister ship ''Bonaventure'', launching her on 5 December 1908. Both ships were completed in January 1909.

''Bellaventure''s registered length was , her beam was , her depth was and her tonnage

Tonnage is a measure of the cargo-carrying capacity of a ship, and is commonly used to assess fees on commercial shipping. The term derives from the taxation paid on ''tuns'' or casks of wine. In modern maritime usage, "tonnage" specifically r ...

s were and . She had a single screw

A screw and a bolt (see '' Differentiation between bolt and screw'' below) are similar types of fastener typically made of metal and characterized by a helical ridge, called a ''male thread'' (external thread). Screws and bolts are used to f ...

, driven by a three-cylinder triple expansion engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be tr ...

that was rated at 347 NHP

Horsepower (hp) is a unit of measurement of power, or the rate at which work is done, usually in reference to the output of engines or motors. There are many different standards and types of horsepower. Two common definitions used today are the ...

.

''Bellaventure''s United Kingdom official number was 127684 and her code letters were TQNL. By 1914 she was equipped for wireless telegraphy

Wireless telegraphy or radiotelegraphy is transmission of text messages by radio waves, analogous to electrical telegraphy using cables. Before about 1910, the term ''wireless telegraphy'' was also used for other experimental technologies for ...

. Her call sign

In broadcasting and radio communications, a call sign (also known as a call name or call letters—and historically as a call signal—or abbreviated as a call) is a unique identifier for a transmitter station. A call sign can be formally assigne ...

was VOM.

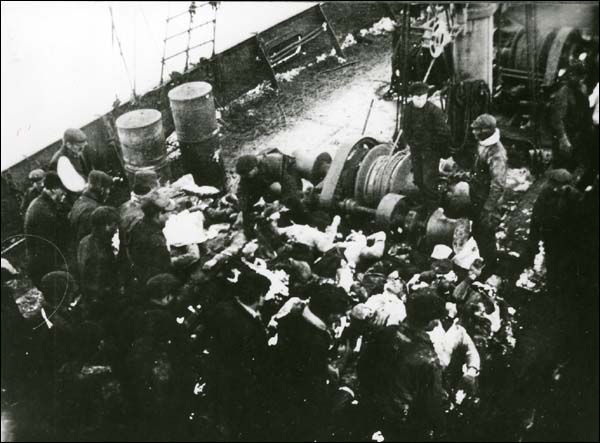

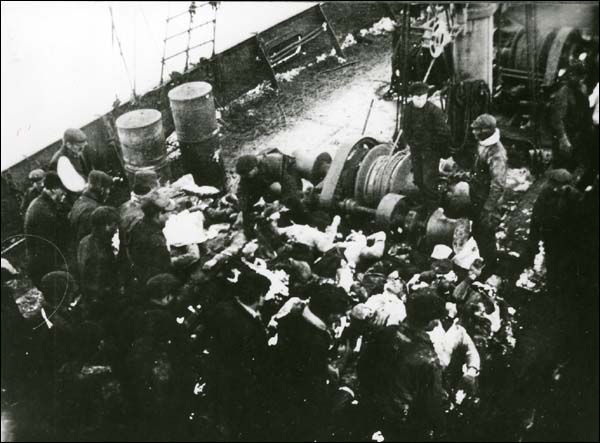

1914 Newfoundland Sealing Disaster

On 2 April 1914 ''Bellaventure'', commanded by Captain

On 2 April 1914 ''Bellaventure'', commanded by Captain Isaac Randell

Isaac Robert Randell (February 15, 1871 – January 15, 1942) was a mariner and politician in Newfoundland. He represented Trinity in the Newfoundland House of Assembly from 1923 to 1928.

The son of John Randell and Mary Fowlow, he was bor ...

, was off the northern coast of Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

taking part in a seal hunt. 132 hunters from another steamship, , had become lost in a storm on an ice floe. After 54 hours ''Bellaventure'' rescued the survivors and recovered 77 dead bodies. She sailed through the Narrows of St. John's, Newfoundland

St. John's is the capital and largest city of the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador, located on the eastern tip of the Avalon Peninsula on the island of Newfoundland.

The city spans and is the easternmost city in North America ...

, with her flags at half mast.

Bought by Russia

In 1917 the Russian government bought both ''Bellaventure'' and ''Bonaventure''. In 1919, in theNorth Russia intervention

The North Russia intervention, also known as the Northern Russian expedition, the Archangel campaign, and the Murman deployment, was part of the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War after the October Revolution. The intervention brought ...

in the Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

, United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

forces in Arkhangelsk

Arkhangelsk (, ; rus, Арха́нгельск, p=ɐrˈxanɡʲɪlʲsk), also known in English as Archangel and Archangelsk, is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. It lies o ...

took control of both ships, and Ellerman's Wilson Line was appointed to manage ''Bellaventure''.

Eventually the two ships were renamed ''Alexander Sibiryakov

Alexander Mikhaylovich Sibiryakov (russian: Алекса́ндр Миха́йлович Сибиряко́в) ( in Irkutsk – 1933) was a Russian gold mine and factories owner and explorer of Siberia.

Biography

Sibiryakov graduated from the Z ...

'' and ''Vladimir Rusanov

Vladimir Alexandrovich Rusanov (russian: Влади́мир Алекса́ндрович Руса́нов; – ca. 1913) was a Russian geologist and Arctic explorer.

Early life

Rusanov was born in a merchant's family in Oryol, Russia. His early ...

'', after two Russian arctic explorers.

Between the wars

''Alexander Sibiryakov'' made the first successful crossing of theNorthern Sea Route

The Northern Sea Route (NSR) (russian: Се́верный морско́й путь, ''Severnyy morskoy put'', shortened to Севморпуть, ''Sevmorput'') is a shipping route officially defined by Russian legislation as lying east of Nov ...

in a single navigation without wintering. This historic voyage, which had been Mikhail Lomonosov

Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov (; russian: Михаил (Михайло) Васильевич Ломоносов, p=mʲɪxɐˈil vɐˈsʲilʲjɪvʲɪtɕ , a=Ru-Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov.ogg; – ) was a Russian Empire, Russian polymath, s ...

's dream, was organized by the All-Union Arctic Institute (now called the Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute

, image =

, image_upright =

, alt =

, caption =

, latin_name =

, motto =

, founder =

, established =

, mission =

, focus = Researc ...

).

''Alexander Sibiryakov'' sailed on 28 June 1932 from the Krasny (previously Sobornoy) docks in Arkhangelsk

Arkhangelsk (, ; rus, Арха́нгельск, p=ɐrˈxanɡʲɪlʲsk), also known in English as Archangel and Archangelsk, is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. It lies o ...

, crossed the Kara Sea

The Kara Sea (russian: Ка́рское мо́ре, ''Karskoye more'') is a marginal sea, separated from the Barents Sea to the west by the Kara Strait and Novaya Zemlya, and from the Laptev Sea to the east by the Severnaya Zemlya archipelago. ...

and chose a northern, unexplored way around Severnaya Zemlya

Severnaya Zemlya (russian: link=no, Сéверная Земля́ (Northern Land), ) is a archipelago in the Russian high Arctic. It lies off Siberia's Taymyr Peninsula, separated from the mainland by the Vilkitsky Strait. This archipelago s ...

to the Laptev Sea

The Laptev Sea ( rus, мо́ре Ла́птевых, r=more Laptevykh; sah, Лаптевтар байҕаллара, translit=Laptevtar baỹğallara) is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. It is located between the northern coast of Siberia, th ...

. In September, after calling at Tiksi

Tiksi ( rus, Ти́кси, , ˈtʲiksʲɪ; sah, Тиксии, ''Tiksii'' – lit. ''a moorage place'') is an urban locality (an urban-type settlement) and the administrative center of Bulunsky District in the Sakha Republic, Russia, located o ...

and the mouth of the Kolyma

Kolyma (russian: Колыма́, ) is a region located in the Russian Far East. It is bounded to the north by the East Siberian Sea and the Arctic Ocean, and by the Sea of Okhotsk to the south. The region gets its name from the Kolyma River an ...

, the propeller shaft broke and the icebreaker drifted for 11 days. However, ''Alexander Sibiryakov'' crossed the Chukchi Sea

Chukchi Sea ( rus, Чуко́тское мо́ре, r=Chukotskoye more, p=tɕʊˈkotskəjə ˈmorʲɪ), sometimes referred to as the Chuuk Sea, Chukotsk Sea or the Sea of Chukotsk, is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. It is bounded on the west b ...

using improvised sails and arrived in the Bering Strait in October. ''Alexander Sibiryakov'' reached the Japanese port of Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of To ...

after 65 days, having covered more than in the Arctic seas. This was regarded as a heroic feat of Soviet polar seamen and Chief of Expedition Otto Schmidt

Otto Yulyevich Shmidt, be, Ота Юльевіч Шміт, Ota Juljevič Šmit (born Otto Friedrich Julius Schmidt; – 7 September 1956), better known as Otto Schmidt, was a Soviet scientist, mathematician, astronomer, geophysicist, statesm ...

and Captain Vladimir Voronin

Vladimir Voronin (; born 25 May 1941) is a Soviet and Moldovan politician. He was the third president of Moldova from 2001 until 2009 and has been the First Secretary of the Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova (PCRM) since 1994. H ...

were received with many honors at their return to Russia.

On 24 November 1936 ''Alexander Sibiryakov'' was stranded near Cape Menshikov in the Kara Sea

The Kara Sea (russian: Ка́рское мо́ре, ''Karskoye more'') is a marginal sea, separated from the Barents Sea to the west by the Kara Strait and Novaya Zemlya, and from the Laptev Sea to the east by the Severnaya Zemlya archipelago. ...

. She was refloated on 25 December 1936 and returned to service in June 1938.

Wartime service and sinking

In September 1941 the Soviet Navy requisitioned ''Alexander Sibiryakov''. She was given thepennant number

In the Royal Navy and other navies of Europe and the Commonwealth of Nations, ships are identified by pennant number (an internationalisation of ''pendant number'', which it was called before 1948). Historically, naval ships flew a flag that iden ...

LD-6. She continued in service, commanded by Captain Anatoli Kacharava. She was defensively armed, at first with several and guns. By 1942 one gun had been added.

On 25 August 1942 during Operation Wunderland

Operation Wunderland ("Wonderland") comprised a large-scale operation undertaken in summer 1942 by the German ''Kriegsmarine'' in the waters of the Northern Sea Route close to the Arctic Ocean. The Germans knew that many ships of the Soviet Navy ...

the Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official branches, along with the a ...

heavy cruiser

The heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range and high speed, armed generally with naval guns of roughly 203 mm (8 inches) in caliber, whose design parameters were dictated by the Washington Naval Tr ...

attacked her off the northwest shore of Russky Island

Russky Island (russian: Ру́сский о́стров, lit. ''Russian Island'') is an island in Peter the Great Gulf in the Sea of Japan, in Primorsky Krai, Russia. It is the largest island in the Eugénie Archipelago, separated from the M ...

in the Nordenskiöld Archipelago

The Nordenskiöld Archipelago or Nordenskjold Archipelago (russian: Архипелаг Норденшельда, Arkhipelag Nordenshel'da) is a large and complex cluster of islands in the eastern region of the Kara Sea. Its eastern limit lies ...

. Despite being heavily outgunned, ''Alexander Sibiryakov'' defended herself for an hour before ''Admiral Scheer'' sank her. ''Alexander Sibiryakov'' also sent a wireless telegraph

Wireless telegraphy or radiotelegraphy is transmission of text messages by radio waves, analogous to electrical telegraphy using cables. Before about 1910, the term ''wireless telegraphy'' was also used for other experimental technologies for ...

signal that warned east and west bound Allied convoys of the attacks, enabling them to avoid the area.

Most members of ''Alexander Sibiryakov''s crew were killed either in battle or when she sank. ''Admiral Scheer'' captured 22, including severely wounded Captain Kacharava. One crewman, stoker Pavel Vavilov, managed to reach Beluha Island and was rescued by a Soviet ship 34 or 35 days later. In total only 15 crew members survived the war. Soviet sources say 79 killed, 19 taken as prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

, and only 13 of them survived captivity.

When the Finnish icebreaker was handed over to the Soviet Union, she was renamed ''Sibiryakov''.

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Alexander Sibiriakov 1909 ships Arctic exploration vessels Chukchi Sea Icebreakers of the Soviet Union Kara Sea Maritime incidents in August 1942 Polar exploration by Russia and the Soviet Union Ships built on the River Clyde Shipwrecks in the Kara Sea Steamships of Canada Steamships of the Soviet Union World War II shipwrecks in the Arctic Ocean