1890s on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 1890s (pronounced "eighteen-nineties") was a

The 1890s (pronounced "eighteen-nineties") was a

*

*

''

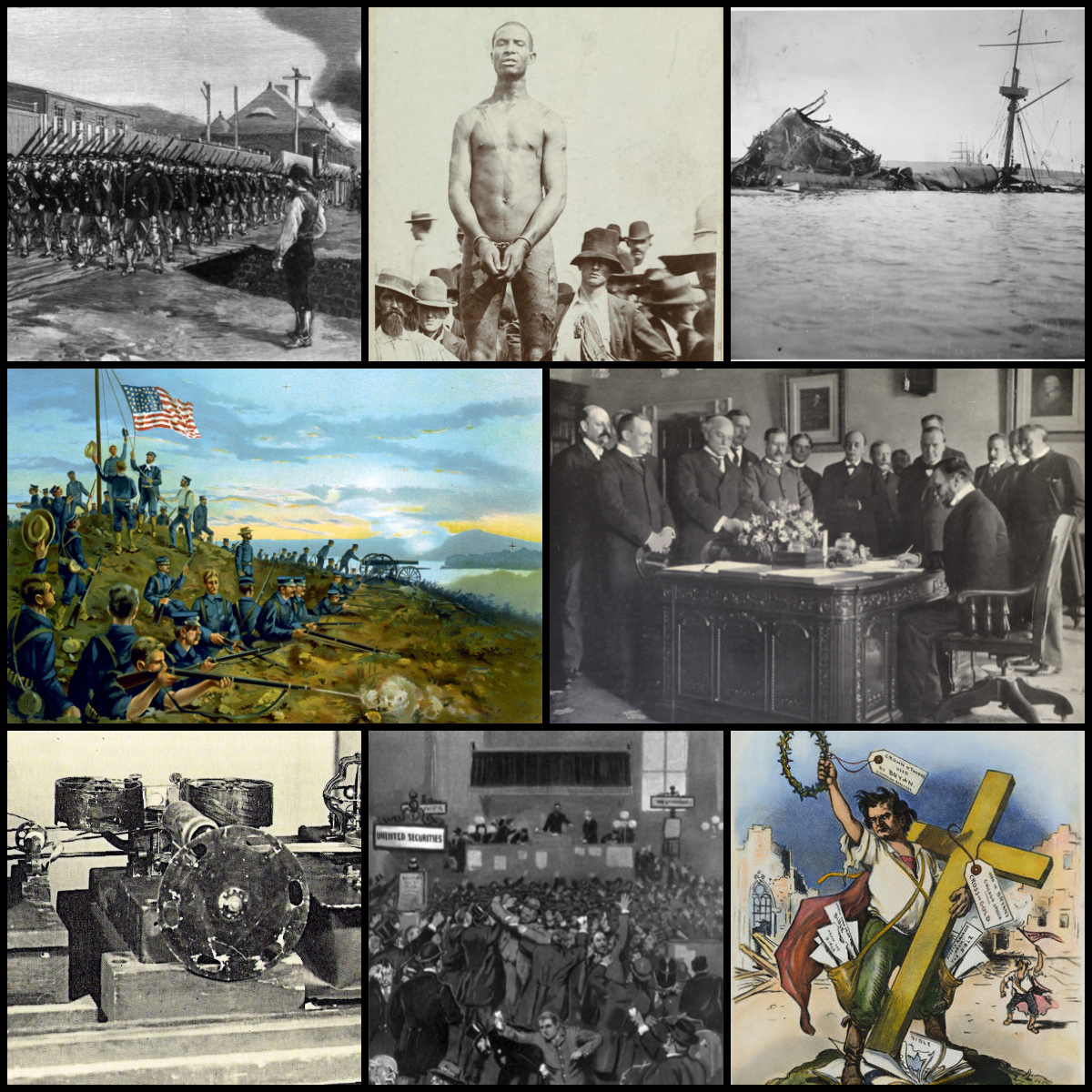

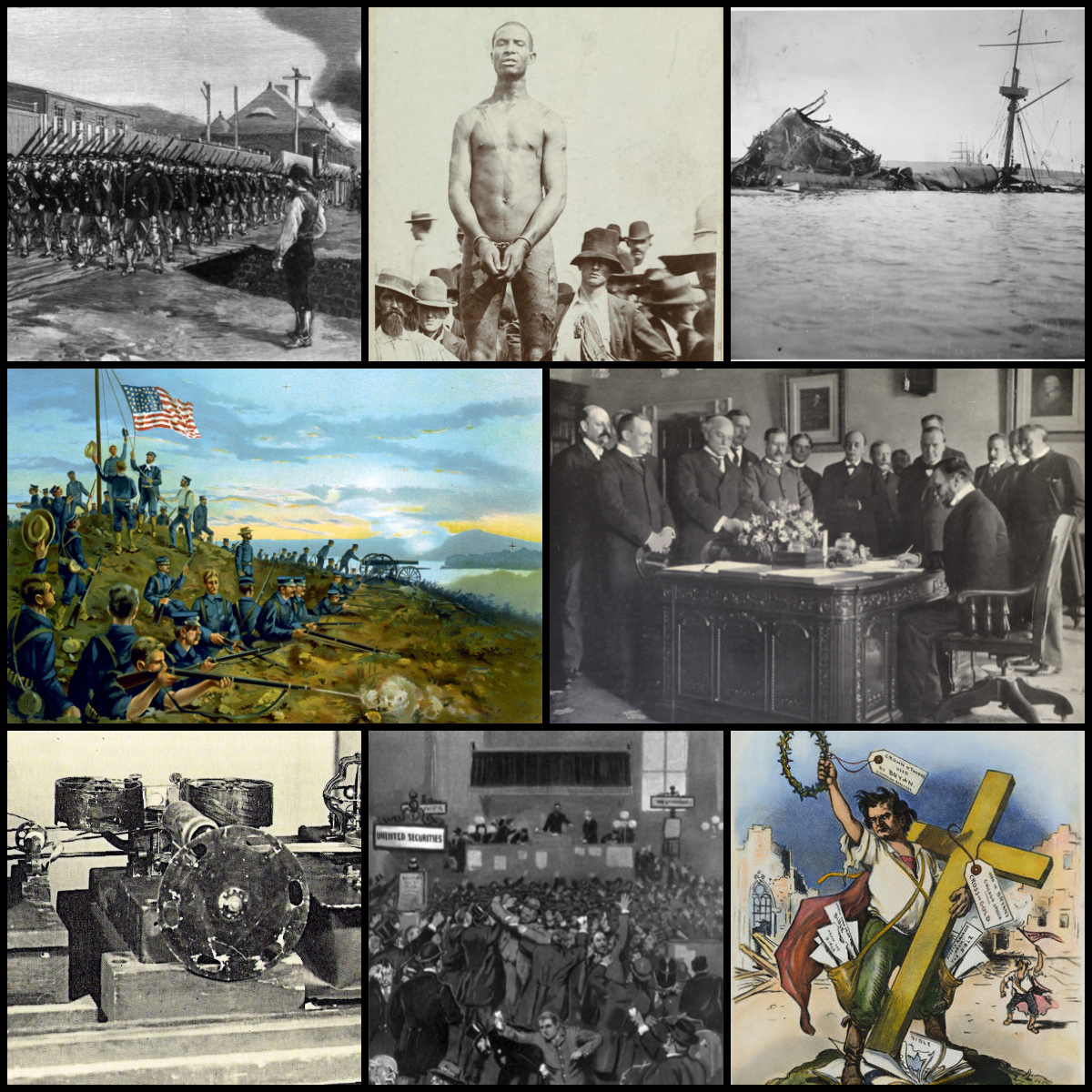

Troops Came Just In Time

' April 15, 1892''Wyoming Tails and Trails''

' January 6, 2004 They were also accompanied by surgeon Dr. Charles Penrose, who served as the group's doctor, as well as

Doukhobortsy and Religious Persecution in Russia

, 1900 (Doukhobor Genealogy Website) * 1896ŌĆō1898: The Philippine Revolution. The

* 1890: A split erupted in

* 1890: A split erupted in

* 1896ŌĆō1897: Leadville Colorado, Miners' Strike. The union local in the Leadville mining district was the Cloud City Miners' Union (CCMU), Local 33 of the

* 1896ŌĆō1897: Leadville Colorado, Miners' Strike. The union local in the Leadville mining district was the Cloud City Miners' Union (CCMU), Local 33 of the

* 1890s: Bike boom sweeps Europe and America with hundreds of bicycle manufacturers in the biggest bicycle craze to date.

* 1890: Cl├®ment Ader of Muret, France creates his Ader ├ēole. "Ader claimed that while he was aboard the Ader Eole he made a steam-engine powered low-level flight of approximately 160 feet on October 9, 1890, in the suburbs of Paris, from a level field on the estate of a friend." It was a powered and heavier-than-air flight, but is often discounted as a candidate for the first flying machine for two main reasons. "It was not capable of a prolonged flight (due to the use of a steam engine) and it lacked adequate provisions for full flight control.". His Ader Avion II and Ader Avion III had more complex designs but failed to take-off.

* 1891: Commercial production of automobiles began and was at an early stage. The first company formed exclusively to build automobiles was Panhard, Panhard et Levassor in

* 1890s: Bike boom sweeps Europe and America with hundreds of bicycle manufacturers in the biggest bicycle craze to date.

* 1890: Cl├®ment Ader of Muret, France creates his Ader ├ēole. "Ader claimed that while he was aboard the Ader Eole he made a steam-engine powered low-level flight of approximately 160 feet on October 9, 1890, in the suburbs of Paris, from a level field on the estate of a friend." It was a powered and heavier-than-air flight, but is often discounted as a candidate for the first flying machine for two main reasons. "It was not capable of a prolonged flight (due to the use of a steam engine) and it lacked adequate provisions for full flight control.". His Ader Avion II and Ader Avion III had more complex designs but failed to take-off.

* 1891: Commercial production of automobiles began and was at an early stage. The first company formed exclusively to build automobiles was Panhard, Panhard et Levassor in  * 1893ŌĆō1894: The Kinetoscope, an early film, motion picture exhibition device invented by Thomas Edison and developed by William Kennedy Dickson, is introduced to the public. (It was in development since 1889 and a number of films had already been created for it). The premiere of the completed Kinetoscope was held not at the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago World's Fair, as originally scheduled, but at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences on May 9, 1893. The first film publicly shown on the system was ''Blacksmith Scene'' (aka ''Blacksmiths''); directed by Dickson and cinematography, shot by Heise, it was produced at the new Edison moviemaking studio, known as the Edison's Black Maria, Black Maria. Despite extensive promotion, a major display of the Kinetoscope, involving as many as twenty-five machines, never took place at the Chicago exposition. Kinetoscope production had been delayed in part because of Dickson's absence of more than eleven weeks early in the year with a nervous breakdown. On April 14, 1894, a public Kinetoscope parlor was opened by the Holland Bros. in New York City at 1155 Broadway, on the corner of 27th StreetŌĆöthe first commercial motion picture house. The venue had ten machines, set up in parallel rows of five, each showing a different movie. For 25 cents a viewer could see all the films in either row; half a dollar gave access to the entire bill. The machines were purchased from the new Kinetoscope Company, which had contracted with Edison for their production; the firm, headed by Norman C. Raff and Frank R. Gammon, included among its investors Andrew M. Holland, one of the entrepreneurial siblings, and Edison's former business chief, Alfred O. Tate. The ten films that comprise the first commercial movie program, all shot at the Black Maria, were descriptively titled: ''Barber Shop'', ''Bertoldi (mouth support)'' (Ena Bertoldi, a British vaudeville contortionist), ''Bertoldi (table contortion)'', ''Blacksmiths'', ''Roosters'' (some manner of cockfighting, cock fight), ''Highland Dance'', ''Horse Shoeing'', ''Sandow'' (Eugen Sandow, a German strongman), ''Trapeze'', and ''Wrestling''. As historian Charles Musser describes, a "profound transformation of American life and performance culture" had begun.

* 1894: Hiram Stevens Maxim completes his flying machine and was ready to use it. He built a long craft that weighed 3.5 tons, with a wingspan that was powered by two compound steam engines driving two propellers. In trials at Bexley in 1894 his machine rode on 1800 rails and was prevented from rising by outriggers underneath and wooden safety rails overhead, somewhat in the manner of a roller coaster. His goal in building this machine was not to soar freely, but to test if it would lift off the ground. During its test run all of the outriggers were engaged, showing that it had developed enough lift to take off, but in so doing it damaged the track; the "flight" was aborted in time to prevent disaster. The craft was almost certainly aerodynamically unstable and uncontrollable, which Maxim probably realized, because he subsequently abandoned work on it. "On the Maxim Biplane Test-Rig's third test run, on July 31, 1894, with Maxim and a crew of three aboard, it lifted with such force that it broke the reinforced restraining track and careened for some 200 yards, at times reaching an altitude of 2 or 3 feet above the damaged track. It was believed that a lifting force of some 10,000 pounds had likely been generated."

* 1894: Lawrence Hargrave of Greenwich, England successfully lifted himself off the ground under a train of four of his box kites at Stanwell Park, New South Wales, Stanwell Park beach, New South Wales, Australia on 12 November 1894. Aided by James Swain, the caretaker at his property, the kite line was moored via a spring balance to two sandbags. Hargrave carried an anemometer and inclinometer aloft to measure windspeed and the angle of the kite line. He rose in a wind speed of . This experiment was widely reported and established the box kite as a stable aerial platform

* 1895: Auguste and Louis Lumi├©re of Besan├¦on, Franche-Comt├®, France introduce cinematograph, a combination film camera, Movie projector, film projector and developer, to the public. Their first public screening of films at which admission was charged was held on December 28, 1895, at Salon Indien du Grand Caf├® in Paris. This history-making presentation featured ten short films, including their first film, ''Workers Leaving the Lumi├©re Factory, Sortie des Usines Lumi├©re ├Ā Lyon'' (''Workers Leaving the Lumi├©re Factory'').

* 1896: Samuel Pierpont Langley of Roxbury, Boston, Massachusetts, has two significant breakthroughs while testing his Langley Aerodromes, flying machines. In May, Aerodrome number 5 made "circular flights of 3,300 and 2,300 feet, at a maximum altitude of some 80 to 100 feet and at a speed of some 20 to 25 miles an hour". In November, Aerodrome number 6 "flew 4,200 feet, staying aloft over 1 minute.". The flights were powered (by a steam engine), but unmanned.

* 1896: Octave Chanute and Augustus Moore Herring co-design the Chanute-Herring Biplane. "Each 16-foot (4.9-meter) wing was covered with varnished silk. The pilot hung from two bars that ran down from the upper wings and passed under his arms. This plane was originally flown at Indiana Dunes State Park, Dune Park, Indiana, about sixty miles from Chanute's home in Chicago, as a triplane on August 29, 1896, but was found to be unwieldy. Chanute and Herring removed the lowest of the three wings, which vastly improved its gliding ability. In its flight on September 11, it flew 256 feet (78 meters)." It influenced the design of later aircraft, setting the pattern for a number of years.

* 1897: Carl Richard Nyberg of Arboga, Sweden starts constructing his Flugan, an early fixed-wing aircraft, outside his home in Liding├Č. Construction started in 1897 and he kept working on it until 1922. The craft only managed a few short jumps and Nyberg was often ridiculed, however several of his innovations are still in use. He was the first to test his design in a wind tunnel and the first to build a hangar. The reasons for failure include poor wing and propeller design and, allegedly, that he was afraid of heights.

* 1898: Wurlitzer builds the first coin-operated player piano.

* 1899: Gustave Whitehead, according to a witness who gave his report in 1934, made a very early motorized flight of about half a mile in Pittsburgh in April or May 1899. Louis Darvarich, a friend of Whitehead's, said they flew together at a height of in a Steam engine, steam-powered monoplane aircraft and crashed into a three-Storey, story building. Darvarich said he was stoking the boiler and was badly scalded in the accident, requiring several weeks in a hospital. This claim is not accepted by mainstream aviation historians including William F. Trimble.

* 1899: Percy Pilcher of Bath, Somerset dies in October, without having a chance to fly his early triplane. Pilcher had built a History of hang gliding, hang glider called ''The Bat'' which he flew for the first time in 1895. He then built more hang gliders ("The Beetle", "The Gull" and "The Hawk"), but had set his sights upon powered flight, which he hoped to achieve on his triplane. On 30 September 1899, having completed his triplane, he had intended to demonstrate it to a group of onlookers and potential sponsors in a field near Stanford Hall. However, days before, the engine crankshaft had broken and, so as not to disappoint his guests, he decided to fly the Hawk instead. The weather was stormy and rainy, but by 4 pm Pilcher decided the weather was good enough to fly. Whilst flying, the tail snapped and Pilcher plunged to the ground: he died two days later from his injuries with his triplane having never been publicly flown. In 2003, a research effort carried out at the School of Aeronautics at Cranfield University, commissioned by the BBC2 television series "Horizon (BBC TV series), Horizon", has shown that Pilcher's design was more or less workable, and had he been able to develop his engine, it is possible he would have succeeded in being the first to fly a heavier-than-air powered aircraft with some degree of control. Cranfield built a replica of Pilcher's aircraft and added the Wright brothers' innovation of wing-warping as a safety backup for roll control. Pilcher's original design did not include aerodynamic controls such as ailerons or elevator. After a very short initial test, the craft achieved a sustained flight of 1 minute and 25 seconds, compared to 59 seconds for the Wright Brothers' best flight at Kitty Hawk. This was achieved under dead calm conditions as an additional safety measure, whereas the Wrights flew in a 25 mph+ wind to achieve enough airspeed on their early attempts.

* 1899: Augustus Moore Herring introduces his biplane glider with a compressed-air engine. On October 11, 1899 (or 1898), Herring flew at Silver Beach Amusement Park in St. Joseph, Michigan. He reportedly covered a distance of . However, there are no known witnesses. On October 22, 1899 (or 1898) Herring took a second flight, covering in 8 to 10 seconds. This time the flight was covered by a newspaper reporter. It is often discounted as a candidate for the first flying machine for various reasons. The craft was difficult to steer, discounting it as controlled flight. While an aircraft outfitted with an engine, said engine could operate for "only 30 seconds at a time". The design was still recognizably a glider, introducing no innovations in that regard. It was also a "technological dead end", failing to influence the flying machines of the 20th century. It also attracted little press coverage, though possibly because the Michigan press was preoccupied with William McKinley, President of the United States visiting Three Oaks, Michigan, at about the same time.

* 1893ŌĆō1894: The Kinetoscope, an early film, motion picture exhibition device invented by Thomas Edison and developed by William Kennedy Dickson, is introduced to the public. (It was in development since 1889 and a number of films had already been created for it). The premiere of the completed Kinetoscope was held not at the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago World's Fair, as originally scheduled, but at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences on May 9, 1893. The first film publicly shown on the system was ''Blacksmith Scene'' (aka ''Blacksmiths''); directed by Dickson and cinematography, shot by Heise, it was produced at the new Edison moviemaking studio, known as the Edison's Black Maria, Black Maria. Despite extensive promotion, a major display of the Kinetoscope, involving as many as twenty-five machines, never took place at the Chicago exposition. Kinetoscope production had been delayed in part because of Dickson's absence of more than eleven weeks early in the year with a nervous breakdown. On April 14, 1894, a public Kinetoscope parlor was opened by the Holland Bros. in New York City at 1155 Broadway, on the corner of 27th StreetŌĆöthe first commercial motion picture house. The venue had ten machines, set up in parallel rows of five, each showing a different movie. For 25 cents a viewer could see all the films in either row; half a dollar gave access to the entire bill. The machines were purchased from the new Kinetoscope Company, which had contracted with Edison for their production; the firm, headed by Norman C. Raff and Frank R. Gammon, included among its investors Andrew M. Holland, one of the entrepreneurial siblings, and Edison's former business chief, Alfred O. Tate. The ten films that comprise the first commercial movie program, all shot at the Black Maria, were descriptively titled: ''Barber Shop'', ''Bertoldi (mouth support)'' (Ena Bertoldi, a British vaudeville contortionist), ''Bertoldi (table contortion)'', ''Blacksmiths'', ''Roosters'' (some manner of cockfighting, cock fight), ''Highland Dance'', ''Horse Shoeing'', ''Sandow'' (Eugen Sandow, a German strongman), ''Trapeze'', and ''Wrestling''. As historian Charles Musser describes, a "profound transformation of American life and performance culture" had begun.

* 1894: Hiram Stevens Maxim completes his flying machine and was ready to use it. He built a long craft that weighed 3.5 tons, with a wingspan that was powered by two compound steam engines driving two propellers. In trials at Bexley in 1894 his machine rode on 1800 rails and was prevented from rising by outriggers underneath and wooden safety rails overhead, somewhat in the manner of a roller coaster. His goal in building this machine was not to soar freely, but to test if it would lift off the ground. During its test run all of the outriggers were engaged, showing that it had developed enough lift to take off, but in so doing it damaged the track; the "flight" was aborted in time to prevent disaster. The craft was almost certainly aerodynamically unstable and uncontrollable, which Maxim probably realized, because he subsequently abandoned work on it. "On the Maxim Biplane Test-Rig's third test run, on July 31, 1894, with Maxim and a crew of three aboard, it lifted with such force that it broke the reinforced restraining track and careened for some 200 yards, at times reaching an altitude of 2 or 3 feet above the damaged track. It was believed that a lifting force of some 10,000 pounds had likely been generated."

* 1894: Lawrence Hargrave of Greenwich, England successfully lifted himself off the ground under a train of four of his box kites at Stanwell Park, New South Wales, Stanwell Park beach, New South Wales, Australia on 12 November 1894. Aided by James Swain, the caretaker at his property, the kite line was moored via a spring balance to two sandbags. Hargrave carried an anemometer and inclinometer aloft to measure windspeed and the angle of the kite line. He rose in a wind speed of . This experiment was widely reported and established the box kite as a stable aerial platform

* 1895: Auguste and Louis Lumi├©re of Besan├¦on, Franche-Comt├®, France introduce cinematograph, a combination film camera, Movie projector, film projector and developer, to the public. Their first public screening of films at which admission was charged was held on December 28, 1895, at Salon Indien du Grand Caf├® in Paris. This history-making presentation featured ten short films, including their first film, ''Workers Leaving the Lumi├©re Factory, Sortie des Usines Lumi├©re ├Ā Lyon'' (''Workers Leaving the Lumi├©re Factory'').

* 1896: Samuel Pierpont Langley of Roxbury, Boston, Massachusetts, has two significant breakthroughs while testing his Langley Aerodromes, flying machines. In May, Aerodrome number 5 made "circular flights of 3,300 and 2,300 feet, at a maximum altitude of some 80 to 100 feet and at a speed of some 20 to 25 miles an hour". In November, Aerodrome number 6 "flew 4,200 feet, staying aloft over 1 minute.". The flights were powered (by a steam engine), but unmanned.

* 1896: Octave Chanute and Augustus Moore Herring co-design the Chanute-Herring Biplane. "Each 16-foot (4.9-meter) wing was covered with varnished silk. The pilot hung from two bars that ran down from the upper wings and passed under his arms. This plane was originally flown at Indiana Dunes State Park, Dune Park, Indiana, about sixty miles from Chanute's home in Chicago, as a triplane on August 29, 1896, but was found to be unwieldy. Chanute and Herring removed the lowest of the three wings, which vastly improved its gliding ability. In its flight on September 11, it flew 256 feet (78 meters)." It influenced the design of later aircraft, setting the pattern for a number of years.

* 1897: Carl Richard Nyberg of Arboga, Sweden starts constructing his Flugan, an early fixed-wing aircraft, outside his home in Liding├Č. Construction started in 1897 and he kept working on it until 1922. The craft only managed a few short jumps and Nyberg was often ridiculed, however several of his innovations are still in use. He was the first to test his design in a wind tunnel and the first to build a hangar. The reasons for failure include poor wing and propeller design and, allegedly, that he was afraid of heights.

* 1898: Wurlitzer builds the first coin-operated player piano.

* 1899: Gustave Whitehead, according to a witness who gave his report in 1934, made a very early motorized flight of about half a mile in Pittsburgh in April or May 1899. Louis Darvarich, a friend of Whitehead's, said they flew together at a height of in a Steam engine, steam-powered monoplane aircraft and crashed into a three-Storey, story building. Darvarich said he was stoking the boiler and was badly scalded in the accident, requiring several weeks in a hospital. This claim is not accepted by mainstream aviation historians including William F. Trimble.

* 1899: Percy Pilcher of Bath, Somerset dies in October, without having a chance to fly his early triplane. Pilcher had built a History of hang gliding, hang glider called ''The Bat'' which he flew for the first time in 1895. He then built more hang gliders ("The Beetle", "The Gull" and "The Hawk"), but had set his sights upon powered flight, which he hoped to achieve on his triplane. On 30 September 1899, having completed his triplane, he had intended to demonstrate it to a group of onlookers and potential sponsors in a field near Stanford Hall. However, days before, the engine crankshaft had broken and, so as not to disappoint his guests, he decided to fly the Hawk instead. The weather was stormy and rainy, but by 4 pm Pilcher decided the weather was good enough to fly. Whilst flying, the tail snapped and Pilcher plunged to the ground: he died two days later from his injuries with his triplane having never been publicly flown. In 2003, a research effort carried out at the School of Aeronautics at Cranfield University, commissioned by the BBC2 television series "Horizon (BBC TV series), Horizon", has shown that Pilcher's design was more or less workable, and had he been able to develop his engine, it is possible he would have succeeded in being the first to fly a heavier-than-air powered aircraft with some degree of control. Cranfield built a replica of Pilcher's aircraft and added the Wright brothers' innovation of wing-warping as a safety backup for roll control. Pilcher's original design did not include aerodynamic controls such as ailerons or elevator. After a very short initial test, the craft achieved a sustained flight of 1 minute and 25 seconds, compared to 59 seconds for the Wright Brothers' best flight at Kitty Hawk. This was achieved under dead calm conditions as an additional safety measure, whereas the Wrights flew in a 25 mph+ wind to achieve enough airspeed on their early attempts.

* 1899: Augustus Moore Herring introduces his biplane glider with a compressed-air engine. On October 11, 1899 (or 1898), Herring flew at Silver Beach Amusement Park in St. Joseph, Michigan. He reportedly covered a distance of . However, there are no known witnesses. On October 22, 1899 (or 1898) Herring took a second flight, covering in 8 to 10 seconds. This time the flight was covered by a newspaper reporter. It is often discounted as a candidate for the first flying machine for various reasons. The craft was difficult to steer, discounting it as controlled flight. While an aircraft outfitted with an engine, said engine could operate for "only 30 seconds at a time". The design was still recognizably a glider, introducing no innovations in that regard. It was also a "technological dead end", failing to influence the flying machines of the 20th century. It also attracted little press coverage, though possibly because the Michigan press was preoccupied with William McKinley, President of the United States visiting Three Oaks, Michigan, at about the same time.Caroll Gray, "The Herring Powered Biplane Glider 1898"

/ref>

File:Oscar Wilde portrait by Napoleon Sarony - albumen.jpg, Oscar Wilde

File:Arthur Conan Doyle by Walter Benington, 1914.png, Arthur Conan Doyle

File:Rudyard Kipling (portrait).jpg, Rudyard Kipling

File:H.G. Wells by Beresford.jpg, H. G. Wells

File:Twain1909.jpg, Mark Twain

File:LewisCarrollSelfPhoto.jpg, Lewis Carroll

File:─īajkovskij ritratto seduto - Odessa (1893).gif, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Tchaikovsky

File:JohannesBrahms.jpg, Johannes Brahms

File:Strauss3.jpg, Richard Strauss

File:Paul Dukas 01.jpg, Paul Dukas

File:Claude Debussy ca 1908, foto av F├®lix Nadar.jpg, Claude Debussy

''The American Annual Cyclopedia and Register of Important Events of the Year'' 1893

''The American Annual Cyclopedia and Register of Important Events of the Year'' 1895

''The American Annual Cyclopedia and Register of Important Events of the Year'' 1896

*

Prices and Wages by Decade: 1890s

ĆöLibrary research guide shows average wages for various occupations and prices for common expenditures in the 1890s. Site hosted by the University of Missouri.

Quiz: Victorian Etiquette

ŌĆō Educational Game, In the style of Monty Python

1890s

1890s

''Booknotes'' interview with H. W. Brands

on ''The Reckless Decade: America in the 1890s'', February 25, 1996 {{Authority control 1890s, 1890s decade overviews

The 1890s (pronounced "eighteen-nineties") was a

The 1890s (pronounced "eighteen-nineties") was a decade

A decade () is a period of ten years. Decades may describe any ten-year period, such as those of a person's life, or refer to specific groupings of calendar years.

Usage

Any period of ten years is a "decade". For example, the statement that "du ...

of the Gregorian calendar

The Gregorian calendar is the calendar used in most parts of the world. It was introduced in October 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII as a modification of, and replacement for, the Julian calendar. The principal change was to space leap years dif ...

that began on January 1, 1890, and ended on December 31, 1899.

In the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, the 1890s were marked by a severe economic depression

An economic depression is a period of carried long-term economical downturn that is result of lowered economic activity in one major or more national economies. Economic depression maybe related to one specific country were there is some economic ...

sparked by the Panic of 1893

The Panic of 1893 was an economic depression in the United States that began in 1893 and ended in 1897. It deeply affected every sector of the economy, and produced political upheaval that led to the political realignment of 1896 and the pres ...

. This economic crisis would help bring about the end of the so-called "Gilded Age

In United States history, the Gilded Age was an era extending roughly from 1877 to 1900, which was sandwiched between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was a time of rapid economic growth, especially in the Northern and Weste ...

", and coincided with numerous industrial strikes in the industrial workforce. From 1926 the period was sometimes referred to as the "Mauve

Mauve (, ; , ) is a pale purple color named after the mallow flower (French: ''mauve''). The first use of the word ''mauve'' as a color was in 1796ŌĆō98 according to the ''Oxford English Dictionary'', but its use seems to have been rare befo ...

Decade", because William Henry Perkin

Sir William Henry Perkin (12 March 1838 ŌĆō 14 July 1907) was a British chemist and entrepreneur best known for his serendipitous discovery of the first commercial synthetic organic dye, mauveine, made from aniline. Though he failed in trying ...

's aniline dye (discovered in London in 1856) allowed the widespread use of that color in fashion

Fashion is a form of self-expression and autonomy at a particular period and place and in a specific context, of clothing, footwear, lifestyle, accessories, makeup, hairstyle, and body posture. The term implies a look defined by the fashion in ...

in the late 1850s and early 1860s.

In France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

the 1890s formed the core of the so-called ''Belle ├ēpoque

The Belle ├ēpoque or La Belle ├ēpoque (; French for "Beautiful Epoch") is a period of French and European history, usually considered to begin around 1871ŌĆō1880 and to end with the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Occurring during the era ...

''.

In the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

the 1890s epitomised the late Victorian period

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardian ...

.

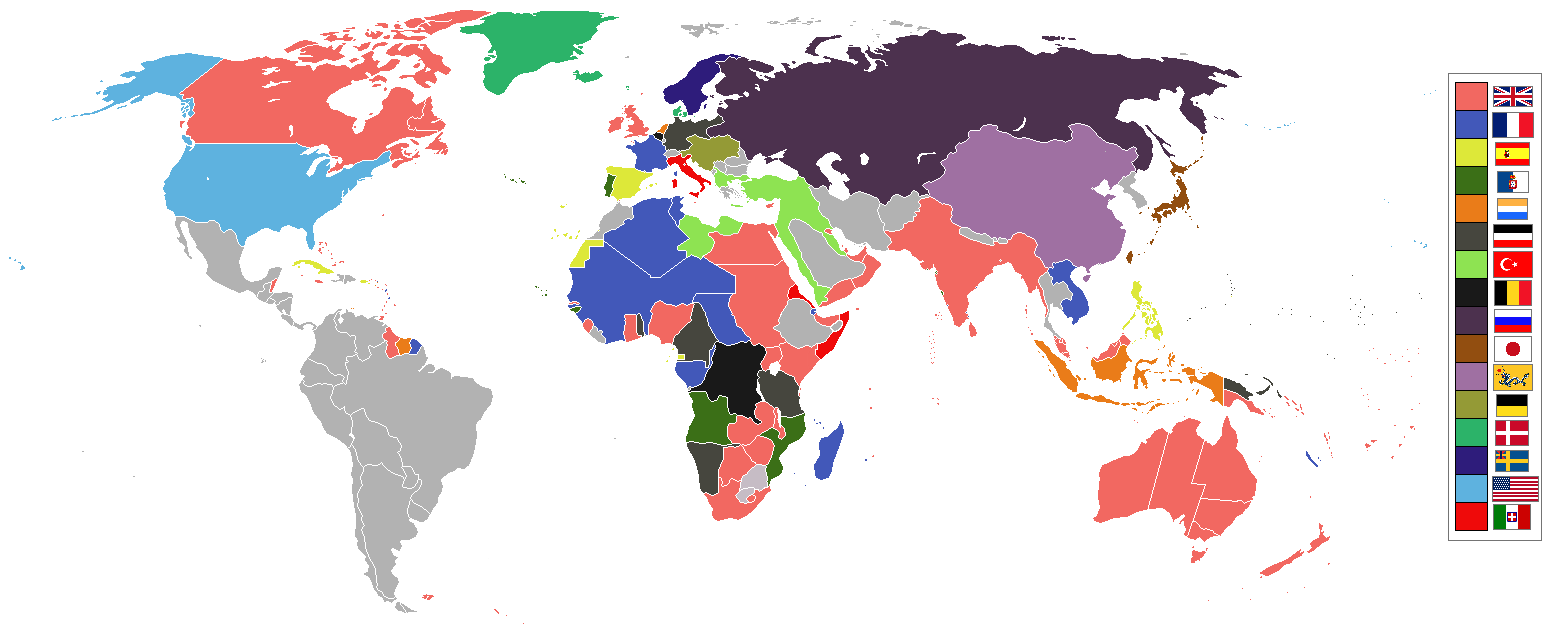

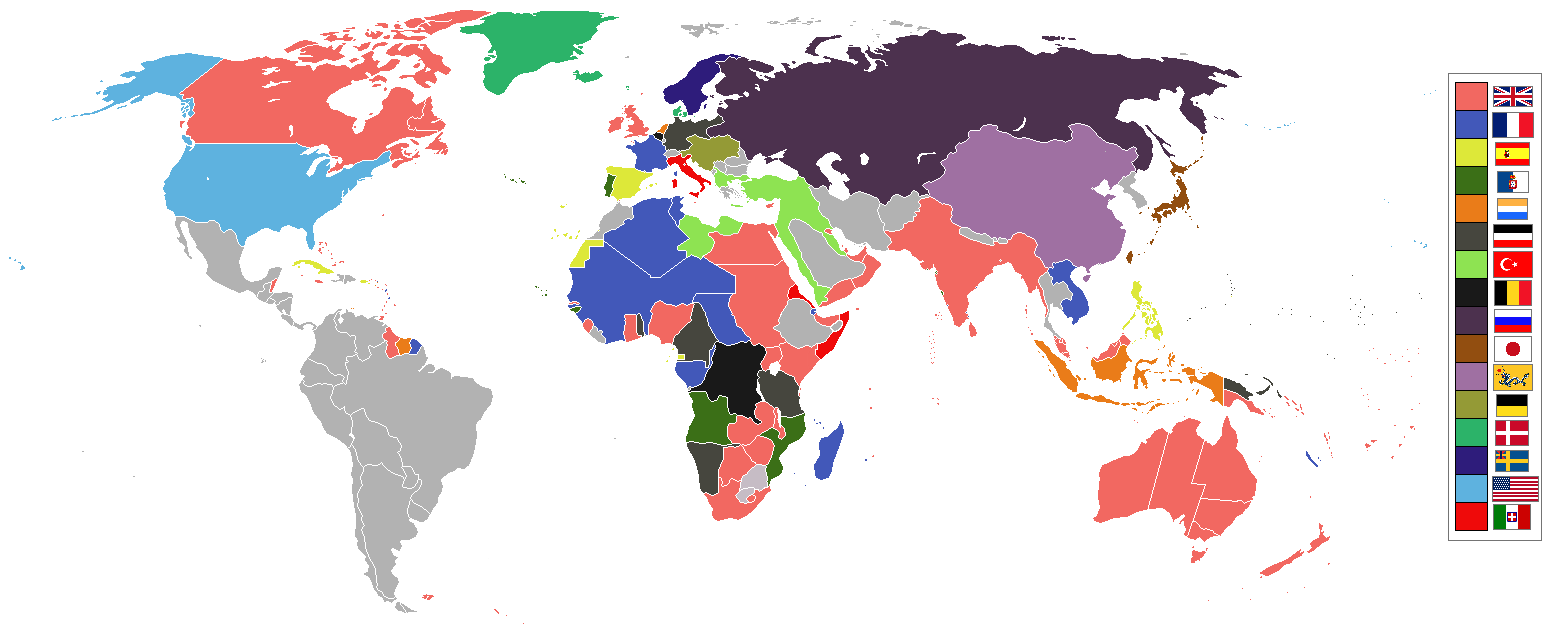

Map

Politics and wars

Wars

*

* First Franco-Dahomean War

The First Franco-Dahomean War was fought in 1890 between France, led by General Alfred-Am├®d├®e Dodds, and Dahomey under King B├®hanzin.

Background

At the close of the 19th century, European powers were busy conquering and colonising much o ...

(1890)

* Second Franco-Dahomean War

The Second Franco-Dahomean War, which raged from 1892 to 1894, was a major conflict between France, led by General Alfred-Am├®d├®e Dodds, and Dahomey under King B├®hanzin. The French emerged triumphant and incorporated Dahomey into their gro ...

(1892ŌĆō1894)

* First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 1894 ŌĆō 17 April 1895) was a conflict between China and Japan primarily over influence in Korea. After more than six months of unbroken successes by Japanese land and naval forces and the loss of the po ...

(1894ŌĆō1895)

* First Italo-Ethiopian War

The First Italo-Ethiopian War, lit. ''Abyssinian War'' was fought between Italy and Ethiopia from 1895 to 1896. It originated from the disputed Treaty of Wuchale, which the Italians claimed turned Ethiopia into an Italian protectorate. Full-sc ...

(1895ŌĆō1896)

* Greco-Turkish War (1897)

The Greco-Turkish War of 1897 or the Ottoman-Greek War of 1897 ( or ), also called the Thirty Days' War and known in Greece as the Black '97 (, ''Mauro '97'') or the Unfortunate War ( el, ╬æŽäŽģŽć╬«Žé ŽĆŽī╬╗╬Ą╬╝╬┐Žé, Atychis polemos), was a w ...

* SpanishŌĆōAmerican War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

(1898)

* PhilippineŌĆōAmerican War

The PhilippineŌĆōAmerican War or FilipinoŌĆōAmerican War ( es, Guerra filipina-estadounidense, tl, Digmaang PilipinoŌĆōAmerikano), previously referred to as the Philippine Insurrection or the Tagalog Insurgency by the United States, was an arm ...

(1899ŌĆō1902)

* Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the AngloŌĆōBoer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

(1899ŌĆō1902)

Wars and Conflicts

* 1890: Wounded Knee Massacre inSouth Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota people, Lakota and Dakota peo ...

. On December 29, 1890, 365 troops of the US 7th Cavalry, supported by four Hotchkiss gun

The Hotchkiss gun can refer to different products of the Hotchkiss arms company starting in the late 19th century. It usually refers to the 1.65-inch (42 mm) light mountain gun; there were also a navy (47 mm) and a 3-inch (76&nbs ...

s, surrounded an encampment of Miniconjou (Lakota

Lakota may refer to:

*Lakota people, a confederation of seven related Native American tribes

*Lakota language, the language of the Lakota peoples

Place names

In the United States:

*Lakota, Iowa

*Lakota, North Dakota, seat of Nelson County

*Lakota ...

) and Hunkpapa Sioux (Lakota) near Wounded Knee Creek

Wounded Knee Creek is a tributary of the White River, approximately 100 miles (160 km) long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed March 30, 2011 in Oglala Lakota County, ...

, South Dakota. The Army had orders to escort the Sioux to the railroad for transport to Omaha, Nebraska

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest cit ...

. One day earlier, the Sioux had been cornered and agreed to turn themselves in at the Pine Ridge Agency

The Pine Ridge Indian Reservation ( lkt, Waz├Ł Ah├Ī┼ŗha┼ŗ Oy├Ī┼ŗke), also called Pine Ridge Agency, is an Oglala Lakota Indian reservation located entirely within the U.S. state of South Dakota. Originally included within the territory of the Gr ...

in South Dakota. They were the last of the Sioux to do so. In the process of disarming the Sioux, a deaf tribesman named Black Coyote could not hear the order to give up his rifle and was reluctant to do so. A scuffle over Black Coyote's rifle escalated into an all-out battle, with those few Sioux warriors who still had weapons shooting at the 7th Cavalry, and the 7th Cavalry opening fire indiscriminately from all sides, killing men, women, and children, as well as some of their own fellow troopers. The 7th Cavalry quickly suppressed the Sioux fire, and the surviving Sioux fled, but US cavalrymen pursued and killed many who were unarmed. By the time it was over, about 146 men, women, and children of the Lakota Sioux had been killed. Twenty-five troopers also died, some believed to have been the victims of friendly fire

In military terminology, friendly fire or fratricide is an attack by belligerent or neutral forces on friendly troops while attempting to attack enemy/hostile targets. Examples include misidentifying the target as hostile, cross-fire while eng ...

as the shooting took place at point-blank range

Point-blank range is any distance over which a certain firearm can hit a target without the need to compensate for bullet drop, and can be adjusted over a wide range of distances by sighting in the firearm. If the bullet leaves the barrel paral ...

in chaotic conditions. Around 150 Lakota are believed to have fled the chaos, with an unknown number later dying from hypothermia

Hypothermia is defined as a body core temperature below in humans. Symptoms depend on the temperature. In mild hypothermia, there is shivering and mental confusion. In moderate hypothermia, shivering stops and confusion increases. In severe h ...

. The incident is noteworthy as the engagement in military history in which the most Medals of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valor. Th ...

have been awarded in the military history of the United States. This was the last tribe to be invaded which broke the backbone of the American Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, were fought by European governments and colonists in North America, and later by the United States and Canadian governments and American and Canadian settle ...

and the American Frontier

The American frontier, also known as the Old West or the Wild West, encompasses the geography, history, folklore, and culture associated with the forward wave of United States territorial acquisitions, American expansion in mainland North Amer ...

.

* 1891: Chilean Civil War fought from January to September. Jos├® Manuel Balmaceda

Jos├® Manuel Emiliano Balmaceda Fern├Īndez (; July 19, 1840 ŌĆō September 19, 1891) served as the 10th President of Chile from September 18, 1886, to August 29, 1891. Balmaceda was part of the Castilian-Basque aristocracy in Chile. While he wa ...

, President of Chile, and the Chilean Army loyal to him face Jorge Montt

Jorge Montt ├ülvarez (; April 26, 1845 ŌĆō October 8, 1922) was a vice admiral in the Chilean Navy and president of Chile from 1891 to 1896.L.S. Rowe, "Passing of a Great Figure in Chilean History." ''Bulletin Pan American Union'' 55 (1922): ...

's Junta

Junta may refer to:

Government and military

* Junta (governing body) (from Spanish), the name of various historical and current governments and governing institutions, including civil ones

** Military junta, one form of junta, government led by ...

. The latter was formed by an alliance between the National Congress of Chile

The National Congress of Chile ( es, Congreso Nacional de Chile) is the legislative branch of the government of the Republic of Chile.

The National Congress of Chile was founded on July 4, 1811. It is a bicameral legislature composed of the Cham ...

and the Chilean Navy.

* 1892: The Johnson County War

The Johnson County War, also known as the War on Powder River and the Wyoming Range War, was a range conflict that took place in Johnson County, Wyoming from 1889 to 1893. The conflict began when cattle companies started ruthlessly persecuting ...

in Wyoming

Wyoming () is a U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the south ...

. Actually this range war

A range war or range conflict is a type of usually violent conflict, most commonly in the 19th and early 20th centuries in the American West. The subject of these conflicts was control of "open range", or range land freely used for cattle grazing, ...

took place in April 1892 in Johnson County, Natrona County

Natrona County is a county in the U.S. state of Wyoming. As of the 2020 United States Census, the population was 79,955, making it the second-most populous county in Wyoming. Its county seat is Casper.

Natrona County comprises the Casper, WY ...

and Converse County

Converse County is a county located in the U.S. state of Wyoming. As of the 2020 United States Census, the population was 13,751. Its county seat is Douglas.

History

Converse County was created in 1888 by the legislature of the Wyoming Territor ...

. The combatants were the Wyoming Stock Growers Association The Wyoming Stock Growers Association (WSGA) is an American cattle organization started in 1872 among Wyoming cattle ranchers to standardize and organize the cattle industry but quickly grew into a political force that has been called "the de facto ...

(the WSGA) and the Northern Wyoming Farmers and Stock Growers' Association (NWFSGA). WSGA was an older organization, comprising some of the state's wealthiest and most popular residents. It held a great deal of political sway in the state and region. A primary function of the WSGA was to organize the cattle industry by scheduling roundups and cattle shipments. The NWFSGAA was a group of smaller Johnson County ranchers led by a local settler named Nate Champion

Nathan D. Champion (September 29, 1857 – April 9, 1892) ŌĆö known as Nate Champion ŌĆö was a key figure in the Johnson County War of April 1892. Falsely accused by a wealthy Wyoming cattlemen's association of being a rustler, Champion was t ...

. They had recently formed their organization in order to compete with the WSGA. The WSGA "blacklisted" the NWFSGA and told them to stop all operations, but the NWFSGA refused the powerful WSGA's orders to disband and instead made public their plans to hold their own roundup in the spring of 1892.Burt, Nathaniel 1991 ''Wyoming'' Compass American Guides, Inc p.159 The WSGA, under the direction of Frank Wolcott

Frank Wolcott (1840–1910) was an officer in the Union Army, a law man and a rancher.

Biography

Early life

Wolcott was born December 13, 1840 in Canandaigua, New York. He served in the Union Army in the Civil War, and was promoted to the ...

(WSGA Member and large North Platte

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north'' is ...

rancher), hired a group of skilled gunmen with the intention of eliminating alleged rustlers in Johnson County and break up the NWFSGA.Inventory of the Johnson County War Collection''

Texas A&M University

Texas A&M University (Texas A&M, A&M, or TAMU) is a public, land-grant, research university in College Station, Texas. It was founded in 1876 and became the flagship institution of the Texas A&M University System in 1948. As of late 2021, T ...

ŌĆō Cushing Memorial Library" Twenty three gunmen from the Paris, Texas

Paris is a city and county seat of Lamar County, Texas, United States. Located in Northeast Texas at the western edge of the Piney Woods, the population of the city was 24,171 in 2020.

History

Present-day Lamar County was part of Red River Co ...

, region and four cattle detectives from the WSGA were hired, as well as Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the CanadaŌĆōUnited States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyom ...

frontiersman George Dunning who would later turn against the group. A cadre of WSGA and Wyoming dignitaries also joined the expedition, including State Senator Bob Tisdale, state water commissioner W. J. Clarke, as well as W. C. Irvine and Hubert Teshemacher, both instrumental in organizing Wyoming's statehood four years earlier.''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' Troops Came Just In Time

' April 15, 1892''Wyoming Tails and Trails''

' January 6, 2004 They were also accompanied by surgeon Dr. Charles Penrose, who served as the group's doctor, as well as

Asa Mercer

Asa Shinn Mercer (June 6, 1839 ŌĆō August 10, 1917) was the first president of the Territorial University of Washington and a member of the Washington State Senate.

He is remembered primarily for his role in three milestones of the old American ...

, the editor of the WSGA's newspaper, and a newspaper reporter for the '' Chicago Herald'', Sam T. Clover, whose lurid first-hand accounts later appeared in the eastern newspapers.

* 1893: The Leper War on Kaua╩╗i

The Leper War on Kauai also known as the Koolau Rebellion, Battle of Kalalau or the short name, the Leper War. Following the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii, the stricter government enforced the 1865 "Act to Prevent the Spread of Leprosy" ca ...

in the island of Kauai

Kauai, () anglicized as Kauai ( ), is geologically the second-oldest of the main Hawaiian Islands (after Ni╩╗ihau). With an area of 562.3 square miles (1,456.4 km2), it is the fourth-largest of these islands and the 21st largest island ...

. The Provisional Government of Hawaii

The Provisional Government of Hawaii (abbr.: P.G.; Hawaiian: ''Aupuni Kūikawā o Hawaiʻi'') was proclaimed after the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 17, 1893, by the 13-member Committee of Safety under the leadership of its ch ...

under Sanford B. Dole

Sanford Ballard Dole (April 23, 1844 ŌĆō June 9, 1926) was a lawyer and jurist from the Hawaiian Islands. He lived through the periods when Hawaii was a Kingdom of Hawaii, kingdom, Provisional Government of Hawaii, protectorate, Republic of Hawa ...

passes a law which would forcibly relocate lepers

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease (HD), is a long-term infection by the bacteria ''Mycobacterium leprae'' or ''Mycobacterium lepromatosis''. Infection can lead to damage of the nerves, respiratory tract, skin, and eyes. This nerve damag ...

to the Leprosy Colony of Kalawao

Kalawao () is a location on the eastern side of the Kalaupapa Peninsula of the island of Molokai, in Hawaii, which was the site of Hawaii's leper colony between 1866 and the early 20th century. Thousands of people in total came to the island to l ...

on the Kalaupapa peninsula

Kalawao County ( haw, Kalana o Kalawao) is a county in the U.S. state of Hawaii. It is the smallest county in the 50 states by land area and the second-smallest county by population, after Loving County, Texas. The county encompasses the Kala ...

. When Kaluaikoolau, a leper, resisted arrest by a deputy sheriff and killed the man, Dole reacted by sending armed militia against the lepers of Kalalau Valley

The Kalalau Valley is located on the northwest side of the island of Kauai in the state of Hawaii. The valley is located in the N─ü Pali Coast State Park and houses the Kalalau Beach. The N─ü Pali Coast is rugged and is inaccessible to aut ...

. Kaluaikoolau reportedly foiled or killed some of his pursuers. But the conflict ended with the evacuation of the area in July, 1893. The main source for the event is a 1906 publication by Kahikina Kelekona (John Sheldon), preserving the story as told by Piilani, Kaluaikoolau's widow.

* 1893ŌĆō1894: Enid-Pond Creek Railroad War in the Oklahoma Territory

The Territory of Oklahoma was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 2, 1890, until November 16, 1907, when it was joined with the Indian Territory under a new constitution and admitted to the Union as th ...

. Effectively a county seat war

A county seat war is an American phenomenon that occurred mainly in the Old West as it was being settled and county lines determined. Incidents elsewhere, such as in southeastern Ohio and West Virginia, have also been recorded. As new towns s ...

. The Rock Island Railroad Company had invested in the townships of Enid and Pond Creek following an announcement by the United States Department of the Interior

The United States Department of the Interior (DOI) is one of the executive departments of the U.S. federal government headquartered at the Main Interior Building, located at 1849 C Street NW in Washington, D.C. It is responsible for the mana ...

that the two would become county seats. The Department of the Interior decided to create an Enid and Pond Creek at another location, free of company influence. Resulting in two Enids and two Pond Creeks vying for becoming county seats, starting in September, 1893. Rock Island refused to have its trains stop at "Government Enid". They would pass by without taking passengers. Frustrated Enid residents "turned to acts of violence". Some were regularly shooting

Shooting is the act or process of discharging a projectile from a ranged weapon (such as a gun, bow, crossbow, slingshot, or blowpipe). Even the acts of launching flame, artillery, darts, harpoons, grenades, rockets, and guided missiles can ...

at the trains. Others were damaging trestle

ATLAS-I (Air Force Weapons Lab Transmission-Line Aircraft Simulator), better known as Trestle, was a unique electromagnetic pulse (EMP) generation and testing apparatus built between 1972 and 1980 during the Cold War at Sandia National Laborato ...

s and rail tracks

A railway track (British English and UIC terminology) or railroad track (American English), also known as permanent way or simply track, is the structure on a railway or railroad consisting of the rails, fasteners, railroad ties (sleepers, ...

, setting up train accidents. Only government intervention stopped the conflict in September, 1894.

* 1893ŌĆō1897: War of Canudos

The War of Canudos (, , 1895ŌĆō1898) was a conflict between the First Brazilian Republic and the residents of Canudos in the northeastern state of Bahia. It was waged in the aftermath of the abolition of slavery in Brazil (1888) and the overthr ...

, a conflict between the state of Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

and a group of some 30,000 settlers under Ant├┤nio Conselheiro

Ant├┤nio Conselheiro, in English "Anthony the Counselor", real name Ant├┤nio Vicente Mendes Maciel (March 13, 1830 ŌĆō September 22, 1897) was a Brazilian religious leader, preacher, and founder of the village of Canudos, the scene of the War of ...

who had founded their own community in the northeastern state of Bahia

Bahia ( , , ; meaning "bay") is one of the 26 Federative units of Brazil, states of Brazil, located in the Northeast Region, Brazil, Northeast Region of the country. It is the fourth-largest Brazilian state by population (after S├Żo Paulo (sta ...

, named Canudos

Canudos is a municipality in the northeast region of Bahia, Brazil. The original town, since flooded by the Cocorob├│ Dam, was the scene of violent clashes between peasants and republican police in the 1890s.

The municipality contains part of th ...

. After a number of unsuccessful attempts at military suppression, it came to a brutal end in October 1897, when a large Brazilian army force overran the village and killed most of the inhabitants. The conflict started with Conselheiro and his jagun├¦o

A Jagun├¦o (), from the Portuguese ''zarguncho'' (a weapon of African origin, similar to a short lance or ''chuzo''), is an armed hand or bodyguard, usually hired by plantation owners and "colonels" in the backlands of Brazil, especially in Nort ...

s (landless peasants) of this "remote and arid" area protesting against the payment of taxes to the distant government of Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after S├Żo Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

. They founded their own self-sufficient village, soon joined by others in search of a "Promised Land

The Promised Land ( he, ūöūÉū©ūź ūöū×ūĢūæūśūŚū¬, translit.: ''ha'aretz hamuvtakhat''; ar, žŻž▒žČ ž¦┘ä┘ģ┘Ŗž╣ž¦ž», translit.: ''ard al-mi'ad; also known as "The Land of Milk and Honey"'') is the land which, according to the Tanakh (the Hebrew ...

". By 1895, they refused requests by Rodrigues Lima, Governor of Bahia and Jeronimo Thome da Silva, Archbishop of S├Żo Salvador da Bahia

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdi ...

to start obeying the laws of the Brazilian state and the rules of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. In 1896, a military expedition under Lieutenant Manuel da Silva Pires Ferreira was sent to pacify them. It was instead attacked, defeated and forced to retreat. Increasingly stronger military forces were sent against Canudos, only to meet with fierce resistance and suffering heavy casualties. In October 1897, Canudos finally fell to the Brazilian military forces. "Those jagun├¦os who were not killed in combat were taken prisoner and summarily executed (by beheading) by the army".

* 1894: The Donghak Peasant Revolution

The Donghak Peasant Revolution (), also known as the Donghak Peasant Movement (), Donghak Rebellion, Peasant Revolt of 1894, Gabo Peasant Revolution, and a variety of Donghak Peasant Revolution#Role played by Donghak, other names, was an armed ...

in Joseon

Joseon (; ; Middle Korean: ļÉ┤ßćóŃĆ»ņģśŃĆ« DyŪÆw sy├®on or ļÉ┤ßćóŃĆ»ņģśŃĆ» DyŪÆw sy─øon), officially the Great Joseon (; ), was the last dynastic kingdom of Korea, lasting just over 500 years. It was founded by Yi Seong-gye in July 1392 and re ...

Korea. The uprising started in Gobu during February 1894, with the peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasants ...

class

Class or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used differentl ...

protesting against the political corruption

Political corruption is the use of powers by government officials or their network contacts for illegitimate private gain.

Forms of corruption vary, but can include bribery, lobbying, extortion, cronyism, nepotism, parochialism, patronage, in ...

of local government officials. The revolution was named after Donghak

Donghak (formerly spelled Tonghak; ) was an academic movement in Korean Neo-Confucianism founded in 1860 by Choe Je-u. The Donghak movement arose as a reaction to seohak (), and called for a return to the "Way of Heaven". While Donghak originat ...

, a Korean religion stressing "the equality

Equality may refer to:

Society

* Political equality, in which all members of a society are of equal standing

** Consociationalism, in which an ethnically, religiously, or linguistically divided state functions by cooperation of each group's elite ...

of all human beings". The forces of Emperor Gojong

Gojong (; 8 September 1852 ŌĆō 21 January 1919) was the monarch of Korea from 1864 to 1907. He reigned as the last King of Joseon from 1864 to 1897, and as the first Emperor of Korea from 1897 until his forced abdication in 1907. He is known ...

failed in their attempt to suppress the revolt, with initial skirmishes giving way to major conflicts. The Korean government requested assistance from the Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent fo ...

. Japanese troops, armed with "rifle

A rifle is a long-barreled firearm designed for accurate shooting, with a barrel that has a helical pattern of grooves ( rifling) cut into the bore wall. In keeping with their focus on accuracy, rifles are typically designed to be held with ...

s and artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

", managed to suppress the revolution. With Korea being a tributary state

A tributary state is a term for a pre-modern state in a particular type of subordinate relationship to a more powerful state which involved the sending of a regular token of submission, or tribute, to the superior power (the suzerain). This tok ...

to Qing Dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

China, the Japanese military presence was seen as a provocation. The resulting conflict over dominance of Korea would become the First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 1894 ŌĆō 17 April 1895) was a conflict between China and Japan primarily over influence in Korea. After more than six months of unbroken successes by Japanese land and naval forces and the loss of the po ...

. In part, the government of Emperor Meiji

, also called or , was the 122nd emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession. Reigning from 13 February 1867 to his death, he was the first monarch of the Empire of Japan and presided over the Meiji era. He was the figur ...

was acting to prevent expansion by the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

or any other great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

towards Korea. Viewing such an expansion as a direct threat to Japanese national security

National security, or national defence, is the security and defence of a sovereign state, including its citizens, economy, and institutions, which is regarded as a duty of government. Originally conceived as protection against military atta ...

.

* 1895: The Doukhobor

The Doukhobours or Dukhobors (russian: ą┤čāčģąŠą▒ąŠčĆčŗ / ą┤čāčģąŠą▒ąŠčĆčåčŗ, dukhobory / dukhobortsy; ) are a Spiritual Christian ethnoreligious group of Russian origin. They are one of many non-Orthodox ethno-confessional faiths in Russia an ...

s, a pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaign ...

Christian sect of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

, attempt to resist a number of laws and regulations forced on them by the Russian government. They are mostly active in the South Caucasus

The South Caucasus, also known as Transcaucasia or the Transcaucasus, is a geographical region on the border of Eastern Europe and Western Asia, straddling the southern Caucasus Mountains. The South Caucasus roughly corresponds to modern Arme ...

, where universal military conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

was introduced in 1887 and was still controversial. They also refuse to swear an oath of allegiance

An oath of allegiance is an oath whereby a subject or citizen acknowledges a duty of allegiance and swears loyalty to a monarch or a country. In modern republics, oaths are sworn to the country in general, or to the country's constitution. For ...

to Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Pola ...

, the new Russian Emperor. Under further instructions from their exiled leader Peter Vasilevich Verigin

Peter Vasilevich Verigin (russian: ą¤čæčéčĆ ąÆą░čüąĖą╗čīąĄą▓ąĖčć ąÆąĄčĆąĖą│ąĖąĮ) often known as Peter "the Lordly" Verigin ( - October 29, 1924) was a Russian philosopher, activist, and leader of the Community Doukhobors in Canada.

Biography

I ...

, as a sign of absolute pacifism, the Doukhobors of the three Governorates of Transcaucasia made the decision to destroy their weapon

A weapon, arm or armament is any implement or device that can be used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime, law enforcement, s ...

s. As the Doukhobors assembled to burn them on the night of June 28/29 (July 10/11, Gregorian calendar

The Gregorian calendar is the calendar used in most parts of the world. It was introduced in October 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII as a modification of, and replacement for, the Julian calendar. The principal change was to space leap years dif ...

) 1895, with the singing of psalms and spiritual songs, arrests and beatings by government Cossacks

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, koz├Īkok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, ą║ąŠąĘą░╠üą║ąĖ, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: ą║ą░ąĘą░ą║ąĖ╠ü or ...

followed. Soon, Cossacks were billeted in many of the Large Party Doukhobors' villages, and over 4,000 of their original residents were dispersed through villages in other parts of Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

. Many of those died of starvation and exposure.John AshworthDoukhobortsy and Religious Persecution in Russia

, 1900 (Doukhobor Genealogy Website) * 1896ŌĆō1898: The Philippine Revolution. The

Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, Rep├║blica de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, part of the Spanish East Indies

The Spanish East Indies ( es , Indias orientales espa├▒olas ; fil, Silangang Indiyas ng Espanya) were the overseas territories of the Spanish Empire in Asia-Pacific, Asia and Oceania from 1565 to 1898, governed for the Spanish Crown from Mexico C ...

, attempt to secede from the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio espa├▒ol), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarqu├Ła Hisp├Īnica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarqu├Ła Cat├│lica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

. The Philippine Revolution began in August 1896, upon the discovery of the anti-colonial

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on independence m ...

secret organization

A secret society is a club or an organization whose activities, events, inner functioning, or membership are concealed. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence a ...

''Katipunan

The Katipunan, officially known as the Kataastaasan, Kagalanggalangang Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan or Kataastaasan Kagalang-galang na Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan (KKK; en, Supreme and Honorable Association of the Children of the Nation ...

'' by the Spanish authorities. The ''Katipunan'', led by Andr├®s Bonifacio

Andr├®s Bonifacio y de Castro (, ; November 30, 1863May 10, 1897) was a Filipino Freemason and revolutionary leader. He is often called "The Father of the Philippine Revolution", and considered one of the national heroes of the Philippines ...

, was a secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

ist movement and shadow government spread throughout much of the islands whose goal was independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

from Spain through armed revolt. In a mass gathering in Caloocan

Caloocan, officially the City of Caloocan ( fil, Lungsod ng Caloocan; ), is a 1st class highly urbanized city in Metropolitan Manila, Philippines. According to the 2020 census, it has a population of 1,661,584 people making it the fourth-most ...

, the ''Katipunan'' leaders organized themselves into a revolutionary government and openly declared a nationwide armed revolution. Bonifacio called for a simultaneous coordinated attack on the capital Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populate ...

. This attack failed, but the surrounding provinces also rose up in revolt. In particular, rebels in Cavite

Cavite, officially the Province of Cavite ( tl, Lalawigan ng Kabite; Chavacano: ''Provincia de Cavite''), is a province in the Philippines located in the Calabarzon region in Luzon. Located on the southern shores of Manila Bay and southwest ...

led by Emilio Aguinaldo

Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy (: March 22, 1869February 6, 1964) was a Filipino revolutionary, statesman, and military leader who is the youngest president of the Philippines (1899ŌĆō1901) and is recognized as the first president of the Philippine ...

won early victories. A power struggle among the revolutionaries led to Bonifacio's execution in 1897, with command shifting to Aguinaldo who led his own revolutionary government. That year, a truce was officially reached with the Pact of Biak-na-Bato

The Pact of Biak-na-Bato, signed on December 15, 1897, created a truce between Spanish colonial Governor-General Fernando Primo de Rivera and the revolutionary leader Emilio Aguinaldo to end the Philippine Revolution. Aguinaldo and his fellow re ...

and Aguinaldo was exiled to Hong Kong, though hostilities between rebels and the Spanish government never actually ceased.* In 1898, with the outbreak of the SpanishŌĆōAmerican War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

, Aguinaldo unofficially allied with the United States, returned to the Philippines and resumed hostilities against the Spaniards. By June, the rebels had conquered nearly all Spanish-held ground within the Philippines with the exception of Manila. Aguinaldo thus declared independence from Spain and the First Philippine Republic

The Philippine Republic ( es, Rep├║blica Filipina), now officially known as the First Philippine Republic, also referred to by historians as the Malolos Republic, was established in Malolos, Bulacan during the Philippine Revolution against ...

was established. However, neither Spain nor the United States recognized Philippine independence. Spanish rule in the islands only officially ended with the 1898 Treaty of Paris

The Treaty of Peace between the United States of America and the Kingdom of Spain, commonly known as the Treaty of Paris of 1898 ( fil, Kasunduan sa Paris ng 1898; es, Tratado de Par├Łs de 1898), was a treaty signed by Spain and the United Stat ...

, wherein Spain ceded the Philippines and other territories to the United States. The PhilippineŌĆōAmerican War

The PhilippineŌĆōAmerican War or FilipinoŌĆōAmerican War ( es, Guerra filipina-estadounidense, tl, Digmaang PilipinoŌĆōAmerikano), previously referred to as the Philippine Insurrection or the Tagalog Insurgency by the United States, was an arm ...

broke out shortly afterward.

* 1897: The Lattimer massacre

The Lattimer massacre was the violent deaths of at least 19 unarmed striking immigrant anthracite miners at the Lattimer mine near Hazleton, Pennsylvania, United States, on September 10, 1897.Anderson, John W. ''Transitions: From Eastern Europ ...

. The violent deaths of 19 unarmed striking immigrant anthracite

Anthracite, also known as hard coal, and black coal, is a hard, compact variety of coal that has a submetallic luster. It has the highest carbon content, the fewest impurities, and the highest energy density of all types of coal and is the hig ...

coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when dea ...

miners at the Lattimer mine near Hazleton, Pennsylvania

Hazleton is a city in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 29,963 at the 2020 census. Hazleton is the second largest city in Luzerne County. It was incorporated as a borough on January 5, 1857, and as a city on Decembe ...

, on September 10, 1897.Anderson, John W. ''Transitions: From Eastern Europe to Anthracite Community to College Classroom.'' Bloomington, Ind.: iUniverse, 2005. Miller, Randall M. and Pencak, William. ''Pennsylvania: A History of the Commonwealth.'' State College, Penn.: Penn State Press, 2003. The miners, mostly of Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

*Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin screenwr ...

, Slovak, and Lithuanian

Lithuanian may refer to:

* Lithuanians

* Lithuanian language

* The country of Lithuania

* Grand Duchy of Lithuania

* Culture of Lithuania

* Lithuanian cuisine

* Lithuanian Jews as often called "Lithuanians" (''Lita'im'' or ''Litvaks'') by other Jew ...

ethnicity, were shot and killed by a Luzerne County

Luzerne County is a county in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of , of which is land and is water. It is Northeastern Pennsylvania's second-largest county by total area. As of ...

sheriff's posse

Posse is a shortened form of posse comitatus, a group of people summoned to assist law enforcement. The term is also used colloquially to mean a group of friends or associates.

Posse may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Posse'' (1975 ...

. Scores more workers were wounded.Estimates of the number of wounded are inexact. They range from a low of 17 wounded (Duwe, Grant. ''Mass Murder in the United States: A History.'' Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2007. ) to a high of 49 (DeLeon, Clark. ''Pennsylvania Curiosities: Quirky Characters, Roadside Oddities & Other Offbeat Stuff.'' 3rd rev. ed. Guilford, Conn.: Globe Pequot, 2008. ). Other estimates include 30 wounded (Lewis, Ronald L. ''Welsh Americans: A History of Assimilation in the Coalfields.'' Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 2008. ), 32 wounded (Anderson, ''Transitions: From Eastern Europe to Anthracite Community to College Classroom,'' 2005; Berger, Stefan; Croll, Andy; and Laporte, Norman. ''Towards A Comparative History of Coalfield Societies.'' Aldershot, Hampshire, UK: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2005. ; Campion, Joan. ''Smokestacks and Black Diamonds: A History of Carbon County, Pennsylvania.'' Easton, Penn.: Canal History and Technology Press, 1997. ), 35 wounded (Foner, Philip S. ''First Facts of American Labor: A Comprehensive Collection of Labor Firsts in the United States.'' New York: Holmes & Meier, 1984. ; Miller and Pencak, ''Pennsylvania: A History of the Commonwealth,'' 2003; Derks, Scott. ''Working Americans, 1880ŌĆō2006: Volume VII: Social Movements.'' Amenia, N.Y.: Grey House Publishing, 2006. ), 38 wounded (Weir, Robert E. and Hanlan, James P. ''Historical Encyclopedia of American Labor, Vol. 1.'' Santa Barbara, Calif.: Greenwood Press, 2004. ), 39 wounded (Long, Priscilla

Priscilla Long (born 1943) is an American writer and political activist. She co-founded a Boston consciousness raising group that contributed to Bread and Roses. A longtime anti-war activist,

Long was arrested in the 1963 Gwynn Oak Park sit-i ...

. '' Where the Sun Never Shines: A History of America's Bloody Coal Industry.'' Minneapolis: Paragon House, 1989. ; Novak, Michael. ''The Guns of Lattimer.'' Reprint ed. New York: Transaction Publishers, 1996. ), and 40 wounded (Beers, Paul B. ''The Pennsylvania Sampler: A Biography of the Keystone State and Its People.'' Mechanicsburg, Penn.: Stackpole Books, 1970). The Lattimer massacre was a turning point in the history of the United Mine Workers

The United Mine Workers of America (UMW or UMWA) is a North American labor union best known for representing coal miners. Today, the Union also represents health care workers, truck drivers, manufacturing workers and public employees in the Unit ...

(UMW).

* 1898: The Bava Beccaris massacre

The Bava Beccaris massacre, named after the Italian General Fiorenzo Bava Beccaris, was the repression of widespread food riots in Milan, Italy, on 6ŌĆō10 May 1898. In Italy the suppression of these demonstrations is also known as ''Fatti di Magg ...

in Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

, Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to ...

. On May 5, 1898, workers organized a strike

Strike may refer to:

People

*Strike (surname)

Physical confrontation or removal

*Strike (attack), attack with an inanimate object or a part of the human body intended to cause harm

*Airstrike, military strike by air forces on either a suspected ...

to demonstrate against the government of Antonio Starabba, Marchese di Rudinì

Antonio Starrabba (o Starabba), Marquess of Rudinì (16 April 18397 August 1908) was an Italian statesman, Prime Minister of Italy between 1891 and 1892 and from 1896 until 1898.

Biography Early life and patriotic activities

He was born in Pal ...

, Prime Minister of Italy, holding it responsible for the general increase of prices and for the famine that was affecting the country. The first blood was shed that day at Pavia

Pavia (, , , ; la, Ticinum; Medieval Latin: ) is a town and comune of south-western Lombardy in northern Italy, south of Milan on the lower Ticino river near its confluence with the Po. It has a population of c. 73,086. The city was the capit ...

, when the son of the mayor of Milan was killed while attempting to halt the troops marching against the crowd. After a protest in Milan the following day, the government declared a state of siege

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to be able to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state du ...

in the city. Infantry, cavalry and artillery were brought into the city and General Fiorenzo Bava Beccaris

Fiorenzo Bava Beccaris (; 17 March 1831 ŌĆō 8 April 1924) was an Italian general, especially remembered for his brutal repression of riots in Milan in 1898, known as the Bava Beccaris massacre.

Biography

Fiorenzo Bava Beccaris was born in Fossa ...

ordered his troops to fire on demonstrators. According to the government, there were 118 dead and 450 wounded. The opposition claimed 400 dead and more than 2,000 injured people. Filippo Turati

Filippo Turati (; 26 November 1857 ŌĆō 29 March 1932) was an Italian sociologist, criminologist, poet and socialist politician.

Early life

Born in Canzo, province of Como, he graduated in law at the University of Bologna in 1877, and participa ...

, one of the founder of the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a socialist and later social-democratic political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parties of the country.

Founded in Genoa in 1892, ...

, was arrested and accused of inspiring the riots.

* 1898: The VouletŌĆōChanoine Mission

The VouletŌĆōChanoine Mission or Central African-Chad Mission (french: mission Afrique Centrale-Tchad) was a French military expedition sent out from Senegal in 1898 to conquer the Chad Basin and unify all French territories in West Africa. This ...

a disastrous French military expedition sent out from Senegal

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: ׿ģ׿½×ż▓׿½×ż║׿óןä׿ż×żŁ (Senegaali); Arabic: ž¦┘äž│┘åž║ž¦┘ä ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''R├®ewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : ׿ł×ż½×ż▓׿Ż×żóןä׿▓׿Ż×żŁ × ...

to conquer the Chad Basin

The Chad Basin is the largest endorheic basin in Africa, centered on Lake Chad. It has no outlet to the sea and contains large areas of semi-arid desert and savanna. The drainage basin is roughly coterminous with the sedimentary basin of the sam ...

and unify all French territories in West Africa. The expedition descended into wanton violence against the local population and ended in sedition on the part of the commanders.

* 1898: The Battle of Sugar Point

The Battle of Sugar Point, or the Battle of Leech Lake, was fought on October 5, 1898 between the 3rd U.S. Infantry and members of the Pillager Band of Chippewa Indians in a failed attempt to apprehend Pillager Ojibwe Bugonaygeshig ("Old Bug" or ...

takes place in the northeast shore of Leech Lake

Leech Lake is a lake located in north central Minnesota, United States. It is southeast of Bemidji, located mainly within the Leech Lake Indian Reservation, and completely within the Chippewa National Forest. It is used as a reservoir. The lake ...

, Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over to ...

. "Old Bug" (Bugonaygeshig