1838 Jesuit slave sale on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

On June 19, 1838, the

Beginning in 1800, there were instances of the Jesuit plantation managers freeing individual slaves or permitting slaves to purchase their freedom. As early as 1814, the trustees of the Corporation of Roman Catholic Clergymen discussed

Beginning in 1800, there were instances of the Jesuit plantation managers freeing individual slaves or permitting slaves to purchase their freedom. As early as 1814, the trustees of the Corporation of Roman Catholic Clergymen discussed

The articles of agreement listed each of the slaves being sold by name. More than half were younger than 20, and nearly a third were not yet 10 years old. The agreement provided that 51 slaves would be sent to the port of

The articles of agreement listed each of the slaves being sold by name. More than half were younger than 20, and nearly a third were not yet 10 years old. The agreement provided that 51 slaves would be sent to the port of

Almost immediately, the sale, which was one of the largest slave sales in the history of the United States, became a scandal among American Catholics. Many Maryland Jesuits were outraged by the sale, which they considered to be immoral, and many of them wrote graphic, emotional accounts of the sale to Roothaan.

Almost immediately, the sale, which was one of the largest slave sales in the history of the United States, became a scandal among American Catholics. Many Maryland Jesuits were outraged by the sale, which they considered to be immoral, and many of them wrote graphic, emotional accounts of the sale to Roothaan.

The 1838 slave sale returned to the public's awareness in the mid-2010s. In 2013, Georgetown began planning to renovate the adjacent Ryan, Mulledy, and Gervase Halls, which together served as the university's Jesuit residence until the opening of a new residence in 2003. After the Jesuits vacated the buildings, Ryan and Mulledy Halls lay vacant, while Gervase Hall was put to other use. In 2014, renovation began on Ryan and Mulledy Halls to convert them into a student residence.

With work complete, in August 2015, university president

The 1838 slave sale returned to the public's awareness in the mid-2010s. In 2013, Georgetown began planning to renovate the adjacent Ryan, Mulledy, and Gervase Halls, which together served as the university's Jesuit residence until the opening of a new residence in 2003. After the Jesuits vacated the buildings, Ryan and Mulledy Halls lay vacant, while Gervase Hall was put to other use. In 2014, renovation began on Ryan and Mulledy Halls to convert them into a student residence.

With work complete, in August 2015, university president

Georgetown Slavery ArchiveJesuit Plantation ProjectSlavery, History, Memory, and Reconciliation ProjectGeorgetown Memory ProjectGU272 Memory ProjectGU272 Descendants AssociationVideo of Isaac Hawkins Hall dedication ceremony from C-SPAN

{{Authority control June 1838 events 1838 in Maryland 1838 in Louisiana 1838 in Washington, D.C. Slave trade in the United States History of slavery in Louisiana History of slavery in Maryland History of slavery in the District of Columbia History of slavery in Virginia Georgetown University History of colleges and universities in Washington, D.C. African-American Roman Catholicism Society of Jesus in the United States Catholicism and slavery

Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

Province of the Society of Jesus

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

agreed to sell 272 slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

to two Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

planters, Henry Johnson and Jesse Batey, for $115,000 (equivalent to approximately $ in ). This sale was the culmination of a contentious and long-running debate among the Maryland Jesuits over whether to keep, sell, or free

Free may refer to:

Concept

* Freedom, having the ability to do something, without having to obey anyone/anything

* Freethought, a position that beliefs should be formed only on the basis of logic, reason, and empiricism

* Emancipate, to procur ...

their slaves, and whether to focus on their rural estates or on their growing urban mission

Mission (from Latin ''missio'' "the act of sending out") may refer to:

Organised activities Religion

*Christian mission, an organized effort to spread Christianity

*Mission (LDS Church), an administrative area of The Church of Jesus Christ of ...

s, including their schools.

In 1836, the Jesuit Superior General, Jan Roothaan

Jan Philipp Roothaan (23 November 1785 – 8 May 1853) was a Dutch Jesuit, elected twenty-first Superior-General of the Society of Jesus.

Early life and formation

He was born to a once-Calvinist family emigrated from Frankfurt to Amsterdam, wher ...

, authorized the provincial superior to carry out the sale on three conditions: the slaves must be permitted to practice their Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

faith, their families must not be separated, and the proceeds of the sale must be used only to support Jesuits in training. It soon became clear that Roothaan's conditions had not been fully met. The Jesuits ultimately received payment many years late and never received the full $115,000. Only 206 of the 272 slaves were actually delivered because the Jesuits permitted the elderly and those with spouses living nearby and not owned by Jesuits to remain in Maryland.

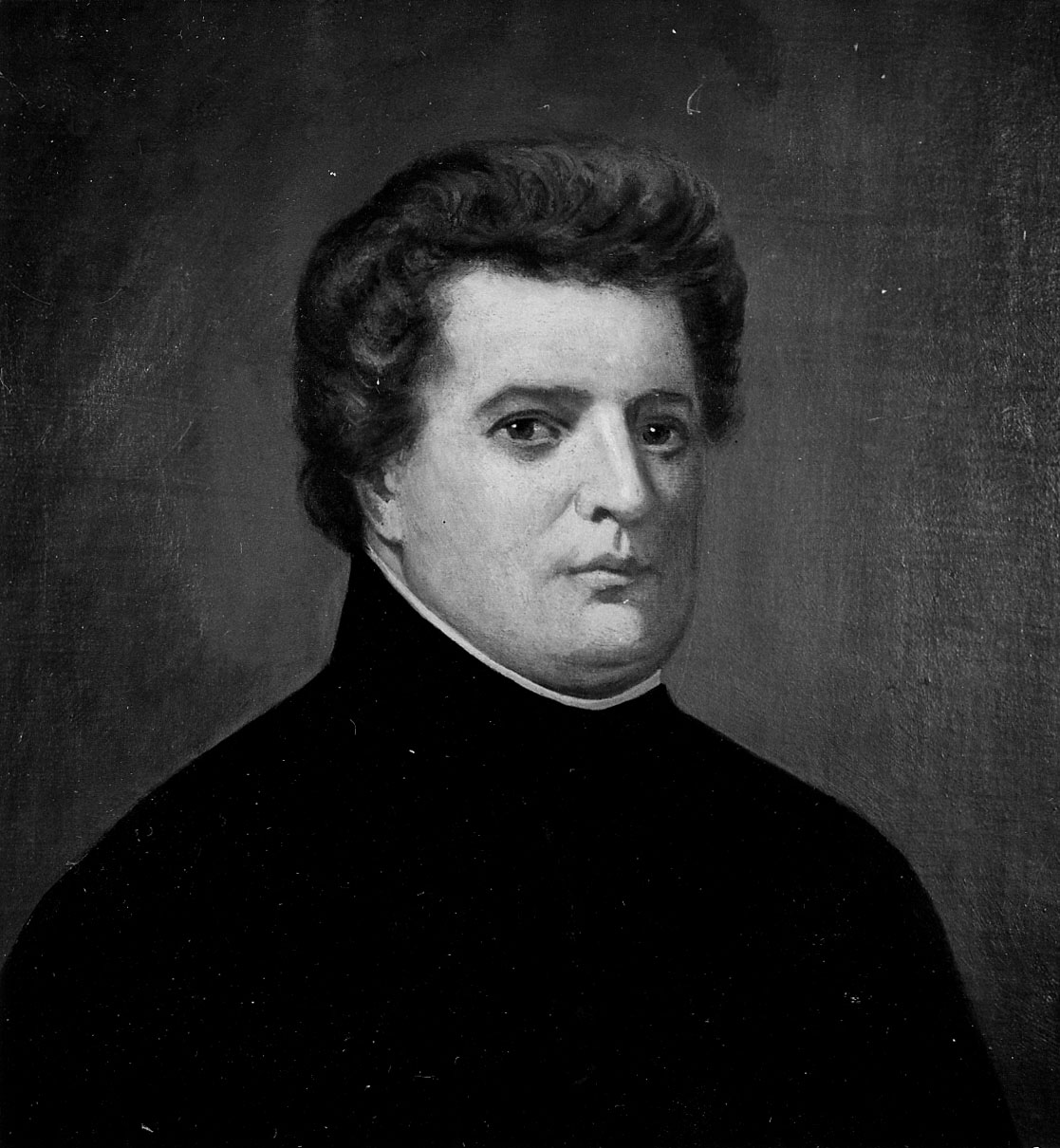

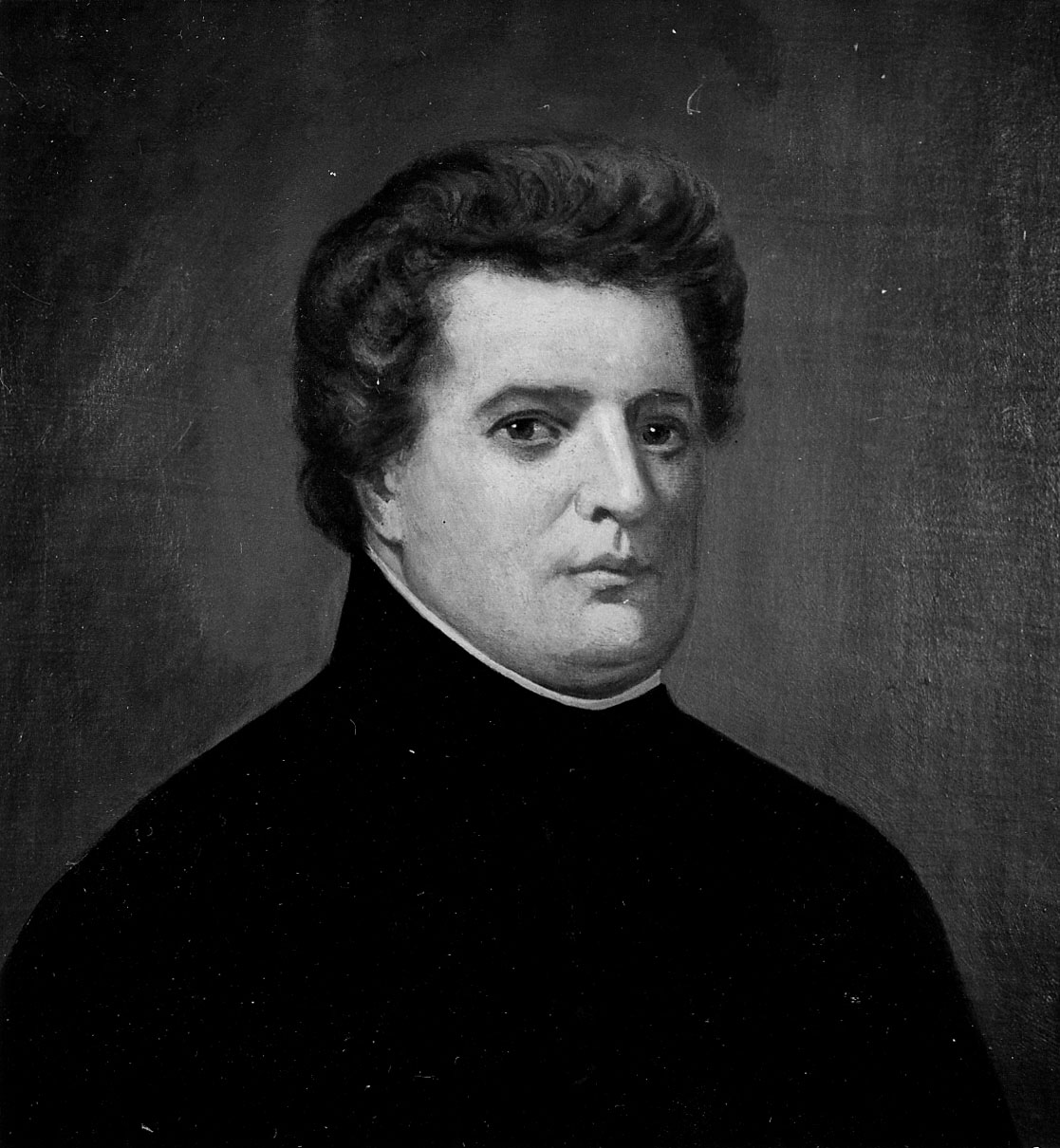

The sale prompted immediate outcry from fellow Jesuits. Some wrote emotional letters to Roothaan denouncing the morality of the sale. Eventually, Roothaan removed Thomas Mulledy

Thomas F. Mulledy ( ; August 12, 1794 – July 20, 1860) was an American Catholic priest and Jesuit who became the president of Georgetown College, a founder of the College of the Holy Cross, and a Jesuit provincial superior. His brother, ...

as provincial superior for disobeying orders and promoting scandal, exiling him to Nice

Nice ( , ; Niçard: , classical norm, or , nonstandard, ; it, Nizza ; lij, Nissa; grc, Νίκαια; la, Nicaea) is the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative c ...

for several years. Despite coverage of the Maryland Jesuits' slave ownership and the 1838 sale in academic literature, news of these facts came as a surprise to the public in 2015, prompting a study of Georgetown University

Georgetown University is a private university, private research university in the Georgetown (Washington, D.C.), Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. Founded by Bishop John Carroll (archbishop of Baltimore), John Carroll in 1789 as Georg ...

's and Jesuits' historical relationship with slavery. Georgetown and the College of the Holy Cross

The College of the Holy Cross is a private, Jesuit liberal arts college in Worcester, Massachusetts, about 40 miles (64 km) west of Boston. Founded in 1843, Holy Cross is the oldest Catholic college in New England and one of the oldest ...

renamed buildings, and the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States

Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States is the collaborating body of the five provincial superiors of the Society of Jesus in Canada, the United States, Belize, and Haiti. The conference includes the Canada Province (which includes Ha ...

pledged to raise $100 million for the descendants of slaves owned by the Jesuits.

Background

Emergence of Jesuit manors

TheSociety of Jesus

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

, whose members are known as Jesuits, established its first presence in the Mid-Atlantic region of the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

alongside the first settlers of the British Province of Maryland, which had been founded as a Catholic colony and refuge. Three Jesuits traveled aboard ''The Ark'' and ''The Dove'' on Lord Baltimore's voyage to settle Maryland in 1634. The Jesuits became substantial landowners in the colony, receiving land patent

A land patent is a form of letters patent assigning official ownership of a particular tract of land that has gone through various legally-prescribed processes like surveying and documentation, followed by the letter's signing, sealing, and publi ...

s from Lord Baltimore in 1636 and bequest

A bequest is property given by will. Historically, the term ''bequest'' was used for personal property given by will and ''deviser'' for real property. Today, the two words are used interchangeably.

The word ''bequeath'' is a verb form for the act ...

s from Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

settlers of Maryland, as well as purchasing some land. As the sole ministers of Catholicism in Maryland at the time, the Jesuit estates became the centers of Catholicism. From these estates, the Jesuits traveled the countryside on horseback, administering the sacrament

A sacrament is a Christianity, Christian Rite (Christianity), rite that is recognized as being particularly important and significant. There are various views on the existence and meaning of such rites. Many Christians consider the sacraments ...

s and catechizing the Catholic laity

In religious organizations, the laity () consists of all members who are not part of the clergy, usually including any non-ordained members of religious orders, e.g. a nun or a lay brother.

In both religious and wider secular usage, a layperson ...

. They also established schools on their lands.

Much of this land was put to use as plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

s, the revenue from which financed the Jesuits' ministries. While the plantations were initially worked by indentured servant

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an " indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment ...

s, as the institution of indentured servitude began to fade away in Maryland, African slave

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

s replaced indentured servants as the primary workers on the plantations. Many of these slaves were gifted to the Jesuits, while others were purchased. The first record of slaves working Jesuit plantations in Maryland dates to 1711, but it is likely that there were slave laborers on the plantations a generation

A generation refers to all of the people born and living at about the same time, regarded collectively. It can also be described as, "the average period, generally considered to be about 20–30 years, during which children are born and gr ...

before then. When the Society of Jesus was suppressed worldwide by Pope Clement XIV

Pope Clement XIV ( la, Clemens XIV; it, Clemente XIV; 31 October 1705 – 22 September 1774), born Giovanni Vincenzo Antonio Ganganelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 May 1769 to his death in Sep ...

in 1773, ownership of the plantations was transferred from the Jesuits' Maryland Mission to the newly established Corporation of Roman Catholic Clergymen. Several of the Jesuits' slaves unsuccessfully attempted to sue for their freedom in the courts in the 1790s.

By 1824, the Jesuit plantations totaled more than in Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, and in eastern Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

. These consisted primarily of the plantations of White Marsh in Prince George's County

)

, demonym = Prince Georgian

, ZIP codes = 20607–20774

, area codes = 240, 301

, founded date = April 23

, founded year = 1696

, named for = Prince George of Denmark

, leader_title = Executive

, leader_name = Angela D. Alsobrook ...

, St. Inigoes and Newtown Manor in St. Mary's County St. Mary's County may refer to:

* St. Mary's County, Maryland

*St. Mary's County, Utah Territory

There are 29 counties in the U.S. state of Utah. There were originally seven counties established under the provisional State of Deseret in 1849: ...

, St. Thomas Manor in Charles County

Charles County is a county in Southern Maryland. As of the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census, the population was 166,617. The county seat is La Plata, Maryland, La Plata. The county was named for Charles Calvert, 3rd Baron Baltimore, Charle ...

, and Bohemia Manor in Cecil County

Cecil County () is a county located in the U.S. state of Maryland at the northeastern corner of the state, bordering both Pennsylvania and Delaware. As of the 2020 census, the population was 103,725. The county seat is Elkton. The county was ...

. The main crops grown were tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

and corn

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. Th ...

.

Due to these extensive landholdings, the Catholic superiors at the ''Propaganda Fide'' in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

had come to view the American Jesuits negatively, believing they lived lavishly like manorial lords. In reality, by the early 19th century, the Jesuit plantations were in such a state of mismanagement that the Jesuit Superior General in Rome, Tadeusz Brzozowski, sent Irish Jesuit Peter Kenney

Peter James Kenney (1779–1841) was an Irish Jesuit priest. He founded Clongowes Wood College and was also rector of the Jesuits in Ireland. A gifted administrator, Kenney made two trips to the United States, where he established Maryland as ...

to review the operations of the Maryland Mission as a canonical visitor in 1820. In addition to becoming physically dilapidated, all but one of the plantations had fallen into debt. On some plantations, the majority of slaves did not work because they were too young or old. The condition of slaves on the plantations varied over time, as did the condition of the Jesuits living with them. Kenney found the slaves facing arbitrary discipline, a meager diet, pastoral neglect, and engaging in vice

A vice is a practice, behaviour, or habit generally considered immoral, sinful, criminal, rude, taboo, depraved, degrading, deviant or perverted in the associated society. In more minor usage, vice can refer to a fault, a negative character tra ...

. By the 1830s, however, their physical and religious conditions had improved considerably.

One of the Maryland Jesuits' institutions, Georgetown College

Georgetown College is a private Christian college in Georgetown, Kentucky. Chartered in 1829, Georgetown was the first Baptist college west of the Appalachian Mountains.

The college offers 38 undergraduate degrees and a Master of Arts in educat ...

(later known as Georgetown University), also rented slaves. While the school did own a small number of slaves over its early decades, its main relationship with slavery was the leasing of slaves to work on campus, a practice that continued past the 1838 slave sale.

Debate over the slavery question

Beginning in 1800, there were instances of the Jesuit plantation managers freeing individual slaves or permitting slaves to purchase their freedom. As early as 1814, the trustees of the Corporation of Roman Catholic Clergymen discussed

Beginning in 1800, there were instances of the Jesuit plantation managers freeing individual slaves or permitting slaves to purchase their freedom. As early as 1814, the trustees of the Corporation of Roman Catholic Clergymen discussed manumit

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that t ...

ting all their slaves and abolishing slavery on the Jesuit plantations, though in 1820, they decided against universal manumission. In 1830, the new Superior General, Jan Roothaan

Jan Philipp Roothaan (23 November 1785 – 8 May 1853) was a Dutch Jesuit, elected twenty-first Superior-General of the Society of Jesus.

Early life and formation

He was born to a once-Calvinist family emigrated from Frankfurt to Amsterdam, wher ...

, returned Kenney to the United States, specifically to address the question of whether the Jesuits should divest themselves of their rural plantations altogether, which by this time had almost completely paid down their debt.

While Roothaan decided in 1831, based on the advice of the Maryland Mission superior

Superior may refer to:

*Superior (hierarchy), something which is higher in a hierarchical structure of any kind

Places

*Superior (proposed U.S. state), an unsuccessful proposal for the Upper Peninsula of Michigan to form a separate state

*Lake ...

, Francis Dzierozynski, that the Jesuits should maintain and improve their plantations rather than sell them, Kenney and his advisors (Thomas Mulledy

Thomas F. Mulledy ( ; August 12, 1794 – July 20, 1860) was an American Catholic priest and Jesuit who became the president of Georgetown College, a founder of the College of the Holy Cross, and a Jesuit provincial superior. His brother, ...

, William McSherry

William McSherry (July 19, 1799December 18, 1839) was an American Catholic priest and Jesuit who became the president of Georgetown College and a Jesuit provincial superior. The son of Irish immigrants, McSherry was educated at Georgetown C ...

, and Stephen Dubuisson) wrote to Roothaan in 1832 about the growing public opposition to slavery in the United States, and strongly urged Roothaan to allow the Jesuits to gradually free their slaves. Mulledy in particular felt that the plantations were a drain on the Maryland Jesuits; he urged selling the plantations as well as the slaves, believing the Jesuits were only able to support either their estates or their schools in growing urban areas: Georgetown College in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

and St. John's College in Frederick, Maryland

Frederick is a city in and the county seat of Frederick County, Maryland. It is part of the Baltimore–Washington Metropolitan Area. Frederick has long been an important crossroads, located at the intersection of a major north–south Native ...

.

Mulledy and McSherry became increasingly vocal in their opposition to Jesuit slave ownership. While they continued to support gradual emancipation, they believed that this option was becoming increasingly untenable, as the Maryland public's concern grew about the expanding number of free blacks. The two feared that because the public would not accept additional manumitted blacks, the Jesuits would be forced to sell their slaves ''en masse''.

The Maryland Jesuits, having been elevated from a mission

Mission (from Latin ''missio'' "the act of sending out") may refer to:

Organised activities Religion

*Christian mission, an organized effort to spread Christianity

*Mission (LDS Church), an administrative area of The Church of Jesus Christ of ...

to the status of a province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or sovereign state, state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''Roman province, provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire ...

in 1833, held their first general congregation

The General Congregation is an assembly of the Jesuit representatives from all parts of the world, and serves as the highest authority in the Society of Jesus

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption ...

in 1835, where they considered again what to do with their plantations. The province was sharply divided, with the American-born Jesuits supporting a sale and the missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Tho ...

European Jesuits opposing on the basis that it was immoral both to sell their patrimonial lands and to materially and morally harm the slaves by selling them into the Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion in the Southern United States. The term was first used to describe the states most dependent on plantations and slavery prior to the American Civil War. Following the war ...

, where they did not want to go. At the congregation, the senior Jesuits in Maryland voted six to four to proceed with a sale of the slaves, and Dubuisson submitted to the Superior General a summary of the moral and financial arguments on either side of the debate.

Meanwhile, in order to fund the province's operations, McSherry, as the first provincial superior of the Maryland Province, began selling small groups of slaves to planters in Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

in 1835, arguing that it was not possible to sell the slaves to local planters and that the buyers had assured him that they would not mistreat the slaves and would permit them to practice their Catholic faith.

The sale

In October 1836, Roothaan officially authorized the Maryland Jesuits to sell their slaves, so long as three conditions were satisfied: the slaves were to be permitted to practice their Catholic faith, their families were not to be separated, and the proceeds of the sale had to be used to support Jesuits in training, rather than to pay down debts. McSherry delayed selling the slaves because theirmarket value

Market value or OMV (Open Market Valuation) is the price at which an asset would trade in a competitive auction setting. Market value is often used interchangeably with ''open market value'', ''fair value'' or ''fair market value'', although the ...

had greatly diminished as a result of the Panic of 1837

The Panic of 1837 was a financial crisis in the United States that touched off a major depression, which lasted until the mid-1840s. Profits, prices, and wages went down, westward expansion was stalled, unemployment went up, and pessimism abound ...

, and because he was searching for a buyer who would agree to these conditions. In October of that year, Mulledy succeeded McSherry, who was dying, as provincial superior.

Mulledy quickly made arrangements to carry out the sale. He located two Louisiana planters who were willing to purchase the slaves: Henry Johnson, a former United States Senator

The United States Senate is the Upper house, upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives being the Lower house, lower chamber. Together they compose the national Bica ...

and governor of Louisiana

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

, and Jesse Batey. They were looking to buy slaves in the Upper South

The Upland South and Upper South are two overlapping cultural and geographic subregions in the inland part of the Southern and lower Midwestern United States. They differ from the Deep South and Atlantic coastal plain by terrain, history, econom ...

more cheaply than they could in the Deep South, and agreed to Mulledy's asking price of approximately $400 per person.

Terms of the agreement

On June 19, 1838, Mulledy, Johnson, and Batey signed articles of agreement formalizing the sale. Johnson and Batey agreed to pay $115,000, equivalent to $ in , over the course of ten years plus six percent annual interest. In exchange, they would receive 272 slaves from the four Jesuit plantations insouthern Maryland

Southern Maryland is a geographical, cultural and historic region in Maryland composed of the state's southernmost counties on the Western Shore of the Chesapeake Bay. According to the state of Maryland, the region includes all of Calvert, Cha ...

, constituting nearly all of the slaves owned by the Maryland Jesuits. Johnson and Batey were to be held jointly and severally liable

Where two or more persons are liable in respect of the same liability, in most common law legal systems they may either be:

* jointly liable, or

* severally liable, or

* jointly and severally liable.

Joint liability

If parties have joint liabili ...

and each additionally identified a responsible party as a guarantor

In finance, a surety , surety bond or guaranty involves a promise by one party to assume responsibility for the debt obligation of a borrower if that borrower defaults. Usually, a surety bond or surety is a promise by a surety or guarantor to pa ...

. The slaves were also identified as collateral

Collateral may refer to:

Business and finance

* Collateral (finance), a borrower's pledge of specific property to a lender, to secure repayment of a loan

* Marketing collateral, in marketing and sales

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Collate ...

in the event that Johnson, Batey, and their guarantors defaulted on their payments.

The articles of agreement listed each of the slaves being sold by name. More than half were younger than 20, and nearly a third were not yet 10 years old. The agreement provided that 51 slaves would be sent to the port of

The articles of agreement listed each of the slaves being sold by name. More than half were younger than 20, and nearly a third were not yet 10 years old. The agreement provided that 51 slaves would be sent to the port of Alexandria, Virginia

Alexandria is an independent city (United States), independent city in the northern region of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia, United States. It lies on the western bank of the Potomac River approximately south of Downto ...

in order to be shipped to Louisiana. Upon receipt of these 51, Johnson and Batey were to pay the first $25,000. The first payment on the remaining $90,000 would become due after five years. The remainder of the slaves were accounted for in three subsequent bills of sale executed in November 1838, which specified that 64 would go to Batey's plantation named West Oak in Iberville Parish

Iberville Parish (french: Paroisse d'Iberville) is a List of parishes in Louisiana, parish located south of Baton Rouge in the U.S. state of Louisiana, formed in 1807. The parish seat is Plaquemine, Louisiana, Plaquemine. At the 2010 U.S. census, ...

and 140 slaves would be sent to Johnson's two plantations, Ascension Plantation (later known as Chatham Plantation) in Ascension Parish

Ascension Parish (french: Paroisse de l'Ascension, es, Parroquia de Ascensión) is a parish located in the U.S. state of Louisiana. As of the 2020 census, the population was 126,500. Its parish seat is Donaldsonville. The parish was created ...

and another in Maringouin

Maringouin is a town in Iberville Parish, Louisiana, United States. The population was 1,098 at the 2010 census, down from 1,262 at the 2000 census. At the 2020 population estimates program, its population was 966. It is part of the Baton Rouge ...

in Iberville Parish.

Delivery of the slaves

Anticipating that some of the Jesuit plantation managers who opposed the sale would encourage their slaves to flee, Mulledy, along with Johnson and asheriff

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland that is commonly transla ...

, arrived at each of the plantations unannounced to gather the first 51 slaves for transport. When he returned in November to gather the rest of the slaves, the plantation managers had their slaves flee and hide. The slaves Mulledy gathered were sent on the three-week voyage aboard the ''Katherine Jackson,'' which departed Alexandria on November 13 and arrived in New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

on December 6. Most of the slaves who fled returned to their plantations, and Mulledy made a third visit later that month, where he gathered some of the remaining slaves for transport.

Not all of the 272 slaves intended to be sold to Louisiana met that fate. In total, only 206 are known to have been transported to Louisiana. Several substitutions were made to the initial list of those to be sold, and 91 of those initially listed remained in Maryland. There are several reasons many slaves were left behind. The Jesuits decided that the elderly would not be sold south and instead would be permitted to remain in Maryland. Other slaves were sold locally in Maryland so that they would not be separated from their spouses who were either free or owned by non-Jesuits, in compliance with Roothaan's order. Johnson allowed these slaves to remain in Maryland because he intended to return and try to buy their spouses as well. Some of the initial 272 slaves who were not delivered to Johnson were replaced with substitutes. An unknown number of slaves may also have Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

run away

Runaway, Runaways or Run Away may refer to:

Engineering

* Runaway reaction, a chemical reaction releasing more heat than what can be removed and becoming uncontrollable

* Thermal runaway, self-increase of the reaction rate of an exothermic proce ...

and escaped transportation.

Aftermath

Scandal and reproach

Almost immediately, the sale, which was one of the largest slave sales in the history of the United States, became a scandal among American Catholics. Many Maryland Jesuits were outraged by the sale, which they considered to be immoral, and many of them wrote graphic, emotional accounts of the sale to Roothaan.

Almost immediately, the sale, which was one of the largest slave sales in the history of the United States, became a scandal among American Catholics. Many Maryland Jesuits were outraged by the sale, which they considered to be immoral, and many of them wrote graphic, emotional accounts of the sale to Roothaan. Benedict Fenwick

Benedict Joseph Fenwick (September 3, 1782 – August 11, 1846) was an American Catholic prelate, Jesuit, and educator who served as the Bishop of Boston from 1825 until his death in 1846. In 1843, he founded the College of the Holy Cross i ...

, the Bishop of Boston, privately lamented the fate of the slaves and considered the sale an extreme measure. Dubuisson described how the public reputation of the Jesuits in Washington and Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

declined as a result of the sale. Other Jesuits voiced their anger to the Archbishop of Baltimore

The Metropolitan Archdiocese of Baltimore ( la, link=no, Archidiœcesis Baltimorensis) is the premier (or first) see of the Latin Church of the Catholic Church in the United States. The archdiocese comprises the City of Baltimore and nine of Mar ...

, Samuel Eccleston

Samuel Eccleston, P.S.S. (June 27, 1801 – April 22, 1851) was an American prelate of the Roman Catholic Church who served as the fifth Archbishop of the Archdiocese of Baltimore, Maryland from 1834 until his death in 1851.

Biography

Earl ...

, who conveyed this to Roothaan. During the controversy, Mulledy fell into alcoholism

Alcoholism is, broadly, any drinking of alcohol (drug), alcohol that results in significant Mental health, mental or physical health problems. Because there is disagreement on the definition of the word ''alcoholism'', it is not a recognize ...

.

Soon after the sale, Roothaan decided that Mulledy should be removed as provincial superior. Roothaan was particularly concerned because it had become clear that, contrary to his order, families had been separated by the slaves' new owners. In the years after the sale, it also became clear that most of the slaves were not permitted to carry on their Catholic faith because they were living on plantations far removed from any Catholic church or priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particu ...

. While McSherry initially persuaded Roothaan to forgo removing Mulledy, in August 1839, Roothaan resolved that Mulledy must be removed to quell the ongoing scandal. He demanded that Mulledy travel to Rome to answer the charges of disobeying orders and promoting scandal. He ordered McSherry to inform Mulledy that he had been removed as provincial superior, and that if Mulledy refused to step down, he would be dismissed from the Society of Jesus.

Before Roothaan's order reached Mulledy, Mulledy had already accepted the advice of McSherry and Eccleston in June 1839 to resign and go to Rome to defend himself before Roothaan. As censure for the scandal, Roothaan ordered Mulledy to remain in Europe, and Mulledy lived in exile in Nice

Nice ( , ; Niçard: , classical norm, or , nonstandard, ; it, Nizza ; lij, Nissa; grc, Νίκαια; la, Nicaea) is the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative c ...

until 1843.

Financial outcome

While Roothaan ordered that the proceeds of the sale be used to provide for the training of Jesuits, the initial $25,000 was not used for that purpose. Of the sum, $8,000 was used to satisfy a financial obligation that, following a long-running and contentious dispute,Pope Pius VII

Pope Pius VII ( it, Pio VII; born Barnaba Niccolò Maria Luigi Chiaramonti; 14 August 1742 – 20 August 1823), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 14 March 1800 to his death in August 1823. Chiaramonti was also a m ...

had previously determined the Maryland Jesuits owed to Archbishop Ambrose Maréchal

Ambrose Maréchal, P.S.S. (August 28, 1764 – January 29, 1828) was an American Sulpician and prelate of the Roman Catholic Church who served as the third Archbishop of the Archdiocese of Baltimore in Maryland. He dedicated the Basilica of the N ...

of Baltimore and his successors. The remaining $17,000, equivalent to approximately $ in , was used to offset part of Georgetown College's $30,000 of debt that had accrued during the construction of buildings during Mulledy's prior presidency of the college. However, the remainder of the money received did go to funding Jesuit formation.

Johnson was unable to pay according to the schedule of the agreement. As a result, he had to sell his property in the 1840s and renegotiate the terms of his payment. He was allowed to continue paying well beyond the ten years initially allowed, and continued to do so until just before the Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the Civil War. The Proclamation changed the legal sta ...

in 1862, during the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

. The Jesuits never received the total $115,000 that was owed under the agreement.

Subsequent fate of the slaves

Before theabolition of slavery in the United States

From the late 18th to the mid-19th century, various states of the United States of America allowed the enslavement of human beings, mostly of African Americans, Africans who had been transported from Africa during the Atlantic slave trade. The i ...

in 1865, many slaves sold by the Jesuits changed ownership several times. Following Batey's death, his West Oak plantation and the slaves living there were sold in January 1853 to Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

politician Washington Barrow

George Washington Barrow (October 5, 1807 – October 19, 1866) was a slave owner, American politician, a member of the United States House of Representatives for Tennessee's 8th congressional district; he later fought against the Union as a mem ...

and Barrow's son, John S. Barrow, a resident of Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Baton Rouge ( ; ) is a city in and the capital of the U.S. state of Louisiana. Located the eastern bank of the Mississippi River, it is the parish seat of East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana's most populous parish—the equivalent of counties i ...

. In 1856, Washington Barrow sold the slaves he purchased from Batey to William Patrick and Joseph B. Woolfolk of Iberville Parish. Patrick and Woolfolk's slaves were then sold in July 1859 to Emily Sparks, the widow of Austin Woolfolk

Austin Woolfolk (1796–1847) was an American slave trader. Among the busiest slave traders in Maryland, he trafficked more than 2,000 enslaved people through the port of Baltimore to the port of New Orleans, and became notorious in time for selli ...

. Due to financial difficulties, Johnson sold half his property, including some of the slaves he had purchased in 1838, to Philip Barton Key in 1844. Key then transferred this property to John R. Thompson. In 1851, Thompson purchased the second half of Johnson's property, so that by the beginning of the Civil War, all the slaves sold by Mulledy to Johnson were owned by Thompson.

Legacy

Historiography

While the 1838 slave sale gave rise to scandal at the time, the event eventually faded out of the public awareness. However, the history of the sale and the Jesuits' slave ownership was never secret. It is one of the most well-documented slave sales of its era. There was periodic and sometimes extensive coverage of both the sale and the Jesuits' slave ownership in various literature. Articles in the ''Woodstock Letters

The Woodstock Letters were a periodical publication by the Society of Jesus. Originally published by Woodstock College in Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, ...

'', an internal Jesuit publication that later became accessible to the public, routinely addressed both subjects during the course of its existence from 1872 to 1969. The 1970s saw an increase in public scholarship on the Maryland Jesuits' slave ownership. In 1977, the Maryland Province named Georgetown's Lauinger Library

The Joseph Mark Lauinger Library is the main library of Georgetown University and the center of the seven-library Georgetown University Library, Georgetown library system that includes 3.5 million volumes. It holds 1.7 million volumes on six floo ...

as the custodian of its historic archives, which were made available to the public through the Georgetown University Library

The Georgetown University Library is the library system of Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. The library's holdings now contain approximately 3.5 million volumes housed in seven university buildings across 11 separate collections.

Histor ...

, Saint Louis University

Saint Louis University (SLU) is a private Jesuit research university with campuses in St. Louis, Missouri, United States, and Madrid, Spain. Founded in 1818 by Louis William Valentine DuBourg, it is the oldest university west of the Mississip ...

Library, and Maryland State Library

The Maryland State Library Agency is the official state library agency of Maryland located in Baltimore, Maryland. It is governed by the twelve-member Maryland State Library Board.

They administer state and federal funds supporting Maryland's t ...

.

In 1981, historian Robert Emmett Curran presented at academic conferences a comprehensive research into the Maryland Jesuits' participation in slavery, and published this research in 1983. Curran also published Georgetown University's official, bicentennial history in 1993, in which he wrote about the university's and Jesuits' relationship with slavery. Other historians covered the subject in literature published between the 1980s and 2000s. In 1996, the Jesuit Plantation Project was established by historians at Georgetown, which made available to the public via the internet digitized versions of much of the Maryland Jesuits' archives, including the articles of agreement for the 1838 sale.

Return to public awareness

The 1838 slave sale returned to the public's awareness in the mid-2010s. In 2013, Georgetown began planning to renovate the adjacent Ryan, Mulledy, and Gervase Halls, which together served as the university's Jesuit residence until the opening of a new residence in 2003. After the Jesuits vacated the buildings, Ryan and Mulledy Halls lay vacant, while Gervase Hall was put to other use. In 2014, renovation began on Ryan and Mulledy Halls to convert them into a student residence.

With work complete, in August 2015, university president

The 1838 slave sale returned to the public's awareness in the mid-2010s. In 2013, Georgetown began planning to renovate the adjacent Ryan, Mulledy, and Gervase Halls, which together served as the university's Jesuit residence until the opening of a new residence in 2003. After the Jesuits vacated the buildings, Ryan and Mulledy Halls lay vacant, while Gervase Hall was put to other use. In 2014, renovation began on Ryan and Mulledy Halls to convert them into a student residence.

With work complete, in August 2015, university president John DeGioia

John Joseph DeGioia (born 1957) is an American academic administrator and philosopher who has been the president of Georgetown University since 2001. He is the first lay president of the school and is currently its longest-serving president. ...

sent an open letter to the university announcing the opening of the new student residence, which also related Mulledy's role in the 1838 slave sale after stepping down as president of the university. Despite the decades of scholarship on the subject, this revelation came as a surprise to many Georgetown University members, and some criticized the retention of Mulledy's name on the building. An undergraduate student also brought this to public attention in several articles published by the school newspaper, ''The Hoya

''The Hoya'', founded in 1920, is the oldest and largest student newspaper of Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., serving as the university’s newspaper of record. ''The Hoya'' is a student-run paper that prints every Friday and publish ...

'' between 2014 and 2015, about the university's relationship with slavery and the slave sale.

Renaming halls

In September 2015, DeGioia convened a Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation to study the slave sale and recommend how to treat it in the present day. In November of that year, following a student-led protest and sit-in, the working group recommended that the university temporarily rename Mulledy Hall (which opened during Mulledy's presidency in 1833) to Freedom Hall, and McSherry Hall (which opened in 1792 and housed a meditation center) to Remembrance Hall. On November 14, 2015, DeGioia announced that he and the university's board of directors accepted the working group's recommendation, and would rename the buildings accordingly. This coincided with a protest by a group of students against keeping Mulledy's and McSherry's names on the buildings the day before. In 2016, ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' published an article that brought the history of the Jesuits' and university's relationship with slavery to national attention.

The College of the Holy Cross

The College of the Holy Cross is a private, Jesuit liberal arts college in Worcester, Massachusetts, about 40 miles (64 km) west of Boston. Founded in 1843, Holy Cross is the oldest Catholic college in New England and one of the oldest ...

in Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

, of which Mulledy was the first president from 1843 to 1848, also began to reconsider the name of one of its buildings in 2015. Mulledy Hall, a student dormitory that opened in 1966, was renamed as Brooks–Mulledy Hall in 2016, adding the name of a later president, John E. Brooks, who worked to racially integrate

Racial integration, or simply integration, includes desegregation (the process of ending systematic racial segregation). In addition to desegregation, integration includes goals such as leveling barriers to association, creating equal opportunity ...

the college. In 2020, the college removed Mulledy's name.

On April 18, 2017, DeGioia, along with the provincial superior of the Maryland Province, and the president of the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States

Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States is the collaborating body of the five provincial superiors of the Society of Jesus in Canada, the United States, Belize, and Haiti. The conference includes the Canada Province (which includes Ha ...

, held a liturgy

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. ''Liturgy'' can also be used to refer specifically to public worship by Christians. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and partic ...

in which they formally apologized on behalf of their respective institutions for their participation in slavery. The university also gave permanent names to the two buildings. Freedom Hall became Isaac Hawkins Hall, after the first slave listed on the articles of agreement for the 1838 sale. Remembrance Hall became Anne Marie Becraft

Anne Marie Becraft, OSP (1805 – December 16, 1833) was an American educator and nun. One of the first African-American nuns in the Catholic Church, she established a school for black girls in Washington, D.C and later joined the Oblate Sisters o ...

Hall, after a free black woman who founded a school for black girls in the Georgetown neighborhood and later joined the Oblate Sisters of Providence

The Oblate Sisters of Providence (OSP) is a Roman Catholic women's religious institute, founded by Mother Mary Elizabeth Lange, OSP, and Rev. James Nicholas Joubert, SS in 1828 in Baltimore, Maryland for the education of girls of African des ...

.

Additional developments

Georgetown University also extended to descendants of slaves that the Jesuits owned or whose labor benefitted the university the same preferential legacy status inuniversity admission

University admission or college admission is the process through which students enter tertiary education at universities and colleges. Systems vary widely from country to country, and sometimes from institution to institution.

In many countries, ...

given to children of Georgetown alumni. This admissions preference has been described by historian Craig Steven Wilder

Craig Steven Wilder is a professor of American history at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Biography

He grew up in Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn, New York. He received his Ph.D. from Columbia University focusing on urban history, under th ...

as the most significant measure recently taken by a university to account for its historical relationship with slavery. Several groups of descendants have been created, which have lobbied Georgetown University and the Society of Jesus for reparations

Reparation(s) may refer to:

Christianity

* Restitution (theology), the Christian doctrine calling for reparation

* Acts of reparation, prayers for repairing the damages of sin

History

*War reparations

**World War I reparations, made from G ...

, and groups have disagreed with the form that their desired reparations should take.

In 2019, undergraduate students at Georgetown voted in a non-binding referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

to impose a symbolic reparations fee of $27.20 per student. The university instead decided to raise $400,000 per year in voluntary donations for the benefit of descendants. In 2021, the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States pledged to raise $100million for a newly created Descendants Truth and Reconciliation Foundation, which would aim to ultimately raise $1billion, with the purpose of working for the benefit of descendants of all slaves owned by the Jesuits. Georgetown also made a $1million donation to the foundation and a $400,000 donation to create a charitable fund to pay for healthcare and education in Maringouin, Louisiana.

See also

* Great Slave Auction * Slavery at American colleges and universities *History of Georgetown University

The history of Georgetown University spans nearly four hundred years, from the early European settlement of America to the present day. Georgetown University has grown with both its city, Washington, D.C., and the United States, each of which dat ...

*Domestic slave trade

The domestic slave trade, also known as the Second Middle Passage and the interregional slave trade, was the term for the domestic trade of enslaved people within the United States that reallocated slaves across states during the Antebellum period ...

Notes

References

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * *External links

Georgetown Slavery Archive

{{Authority control June 1838 events 1838 in Maryland 1838 in Louisiana 1838 in Washington, D.C. Slave trade in the United States History of slavery in Louisiana History of slavery in Maryland History of slavery in the District of Columbia History of slavery in Virginia Georgetown University History of colleges and universities in Washington, D.C. African-American Roman Catholicism Society of Jesus in the United States Catholicism and slavery