Ămile Ajar on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Gary became one of France's most popular and prolific writers, writing more than 30 novels, essays and memoirs, some of which he wrote under a pseudonym.

He is the only person to win the

Gary became one of France's most popular and prolific writers, writing more than 30 novels, essays and memoirs, some of which he wrote under a pseudonym.

He is the only person to win the

Gary's first wife was the British writer,

Gary's first wife was the British writer,

"ÂŤChien blancÂť: le goĂťt du risque d'AnaĂŻs Barbeau-Lavalette"

''

Romain Gary (; 2 December 1980), born Roman Kacew (, and also known by the pen name Ămile Ajar), was a French novelist, diplomat, film director, and World War II

interview and ''aviator

An aircraft pilot or aviator is a person who controls the flight of an aircraft by operating its Aircraft flight control system, directional flight controls. Some other aircrew, aircrew members, such as navigators or flight engineers, are al ...

. He is the only author to have won the Prix Goncourt

The Prix Goncourt (french: Le prix Goncourt, , ''The Goncourt Prize'') is a prize in French literature, given by the acadĂŠmie Goncourt to the author of "the best and most imaginative prose work of the year". The prize carries a symbolic reward o ...

under two names. He is considered a major writer of French literature

French literature () generally speaking, is literature written in the French language, particularly by citizens of France; it may also refer to literature written by people living in France who speak traditional languages of France other than Fr ...

of the second half of the 20th century. He was married to Lesley Blanch

Lesley Blanch, MBE, FRSL (6 June 1904, London â 7 May 2007, Garavan near Menton, France) was a British writer, historian and traveller. She is best known for '' The Wilder Shores of Love'', about Isabel Burton (who married the Arabist and ex ...

, then Jean Seberg

Jean Dorothy Seberg (; ; November 13, 1938August 30, 1979) was an American actress who lived half of her life in France. Her performance in Jean-Luc Godard's 1960 film ''Breathless'' immortalized her as an icon of French New Wave cinema.

Seb ...

.

Early life

Gary was born Roman Kacew ( yi, ''Roman Katsev'', russian: link=no, РОПаĚĐ˝ ĐĐľĚĐšĐąĐžĐ˛Đ¸Ń ĐĐ°ĚŃов, ''Roman Leibovich Katsev'') inVilnius

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the municipality of Vilnius). The population of Vilnius's functional urb ...

(at that time in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

). In his books and interviews, he presented many different versions of his parents' origins, ancestry, occupation and his own childhood. His mother, Mina OwczyĹska (1879â1941), was a Jewish

Jews ( he, ×Ö°××Öź×Ö´××, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

actress from Ĺ venÄionys

Ĺ venÄionys (, known also by several alternative names) is a town located north of Vilnius in Lithuania. It is the capital of the Ĺ venÄionys district municipality. , it had population of 4,065 of which about 17% is part of the Polish minority ...

(SvintsyĂĄn) and his father was a businessman named Arieh-Leib Kacew (1883â1942) from Trakai

Trakai (; see names section for alternative and historic names) is a historic town and lake resort in Lithuania. It lies west of Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania. Because of its proximity to Vilnius, Trakai is a popular tourist destination. T ...

(Trok), also a Lithuanian Jew

Lithuanian Jews or Litvaks () are Jews with roots in the territory of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania (covering present-day Lithuania, Belarus, Latvia, the northeastern SuwaĹki and BiaĹystok regions of Poland, as well as adjacent areas o ...

. The couple broke in 1925 and Arieh-Leib remarried. Gary later claimed that his actual father was the celebrated actor and film star Ivan Mosjoukine

Ivan Ilyich Mozzhukhin ( rus, Đван ĐĐťŃĐ¸Ń ĐОСМŃŃ

ин, p=ÉŞËvan ɨËlʲjitÉ mÉËĘËĘxʲɪn; —18 January 1939), usually billed using the French transliteration Ivan Mosjoukine, was a Russian silent film actor.

Career in R ...

, with whom his actress mother had worked and to whom he bore a striking resemblance. Mosjoukine appears in his memoir ''Promise at Dawn

''Promise at Dawn'' (french: La Promesse de l'aube) is a 1970 American drama film directed by Jules Dassin and starring Melina Mercouri, Dassin's wife. It is based on the 1960 novel ''Promise at Dawn'' (french: La Promesse de l'aube) by Romain ...

''. Deported to central Russia

Central Russia is, broadly, the various areas in European Russia.

Historically, the area of Central Russia varied based on the purpose for which it is being used. It may, for example, refer to European Russia (except the North Caucasus and ...

in 1915, they stayed in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, ĐĐžŃква, r=Moskva, p=mÉskËva, a=ĐĐžŃква.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

until 1920. They later returned to Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the municipality of Vilnius). The population of Vilnius's functional urb ...

, then moved on to Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

. When Gary was fourteen, he and his mother emigrated illegally to Nice

Nice ( , ; Niçard: , classical norm, or , nonstandard, ; it, Nizza ; lij, Nissa; grc, ÎίκιΚι; la, Nicaea) is the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative c ...

, France. Converted to Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

by his mother, Gary studied law, first in Aix-en-Provence

Aix-en-Provence (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Ais de Provença in classical norm, or in Mistralian norm, ; la, Aquae Sextiae), or simply Aix ( medieval Occitan: ''Aics''), is a city and commune in southern France, about north of Marseille. ...

and then in Paris. He learned to pilot an aircraft in the French Air Force

The French Air and Space Force (AAE) (french: ArmĂŠe de l'air et de l'espace, ) is the air and space force of the French Armed Forces. It was the first military aviation force in history, formed in 1909 as the , a service arm of the French Army; ...

in Salon-de-Provence

Salon-de-Provence (, ; oc, label= Provençal Occitan, Selon de Provença/Seloun de Provènço, ), commonly known as Salon, is a commune located about northwest of Marseille in the Bouches-du-Rhône department, region of Provence-Alpes-Côte d' ...

and in Avord Air Base

Avord Air Base or BA 702 (french: Base AĂŠrienne 702 Capitaine Georges Madon), named after Captain Georges Madon, is a base of the French Air and Space Force (ArmĂŠe de l'air et de l'espace) located north northwest of Avord in central France.

...

, near Bourges

Bourges () is a commune in central France on the river Yèvre. It is the capital of the department of Cher, and also was the capital city of the former province of Berry.

History

The name of the commune derives either from the Bituriges, t ...

.

Career

Of almost 300 cadets in his class, and despite completing all parts of his course successfully, Gary was the only one not to be commissioned as an officer. He believed that the military establishment was distrustful of what they saw as a foreigner and aJew

Jews ( he, ×Ö°××Öź×Ö´××, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""Th ...

. Training on Potez 25 and GoĂŤland LĂŠo-20 aircraft, and with 250 hours flying time, only after three months' delay was he made a sergeant

Sergeant (abbreviated to Sgt. and capitalized when used as a named person's title) is a rank in many uniformed organizations, principally military and policing forces. The alternative spelling, ''serjeant'', is used in The Rifles and other uni ...

on 1 February 1940. Lightly wounded on 13 June 1940 in a Bloch MB.210

The Bloch MB.210 and MB.211 were the successors of the French Bloch MB.200 bomber developed by SociĂŠtĂŠ des Avions Marcel Bloch in the 1930s and differed primarily in being low wing monoplanes rather than high wing monoplanes.

Development

The ...

, he was disappointed with the armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the La ...

; after hearing General de Gaulle

Charles AndrĂŠ Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Governm ...

's radio appeal

In law, an appeal is the process in which cases are reviewed by a higher authority, where parties request a formal change to an official decision. Appeals function both as a process for error correction as well as a process of clarifying and ...

, he decided to go to England. After failed attempts, he flew to Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, اŮ؏زا،ع, al-JazÄĘžir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques ...

from Saint-Laurent-de-la-Salanque

Saint-Laurent-de-la-Salanque (; ca, Sant Llorenç de la Salanca) is a commune in the PyrÊnÊes-Orientales department in southern France.

Geography

Saint-Laurent-de-la-Salanque is located in the canton of La CĂ´te Salanquaise and in the arron ...

in a Potez

Potez (pronounced ) was a French aircraft manufacturer founded as AĂŠroplanes Henry Potez by Henry Potez at Aubervilliers in 1919 in aviation, 1919. The firm began by refurbishing war-surplus SEA IV aircraft, but was soon building new examples of ...

. Made adjutant

Adjutant is a military appointment given to an officer who assists the commanding officer with unit administration, mostly the management of human resources in an army unit. The term is used in French-speaking armed forces as a non-commission ...

upon joining the Free French

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exile ...

and serving on Bristol Blenheim

The Bristol Blenheim is a British light bomber aircraft designed and built by the Bristol Aeroplane Company (Bristol) which was used extensively in the first two years of the Second World War, with examples still being used as trainers until ...

s, he saw action across Africa and was promoted to second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

. He returned to England to train on Boston IIIs. On 25 January 1944, his pilot was blinded, albeit temporarily, and Gary talked him to the bombing target and back home, the third landing being successful. This and the subsequent BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...Evening Standard

The ''Evening Standard'', formerly ''The Standard'' (1827â1904), also known as the ''London Evening Standard'', is a local free daily newspaper in London, England, published Monday to Friday in tabloid format.

In October 2009, after be ...

'' newspaper article were an important part of his career. He finished the war as a captain in the London offices of the Free French Air Forces

The Free French Air Forces (french: Forces AÊriennes Françaises Libres, FAFL) were the air arm of the Free French Forces in the Second World War, created by Charles de Gaulle in 1940. The designation ceased to exist in 1943 when the Free Frenc ...

. As a bombardier-observer in the ''Groupe de bombardement Lorraine'' (No. 342 Squadron RAF), he took part in over 25 successful sorties, logging over 65 hours of air time. During this time, he changed his name to Romain Gary. He was decorated for his bravery in the war, receiving many medals and honours, including Compagnon de la LibĂŠration

The Order of Liberation (french: Ordre de la LibĂŠration) is a French Order which was awarded to heroes of the Liberation of France during World War II. It is a very high honour, second only after the ''LĂŠgion dâHonneur'' (Legion of Honour) ...

and commander of the LĂŠgion d'honneur

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la LĂŠgion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon ...

. In 1945 he published his first novel, ''Ăducation europĂŠenne''. Immediately following his service in the war, he worked in the French diplomatic service in Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, ĐŃНгаŃиŃ, BÇlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

and Switzerland. In 1952 he became the secretary of the French Delegation to the United Nations. In 1956, he became Consul General

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

in Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ăngeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

and became acquainted with Hollywood.

As Ămile Ajar

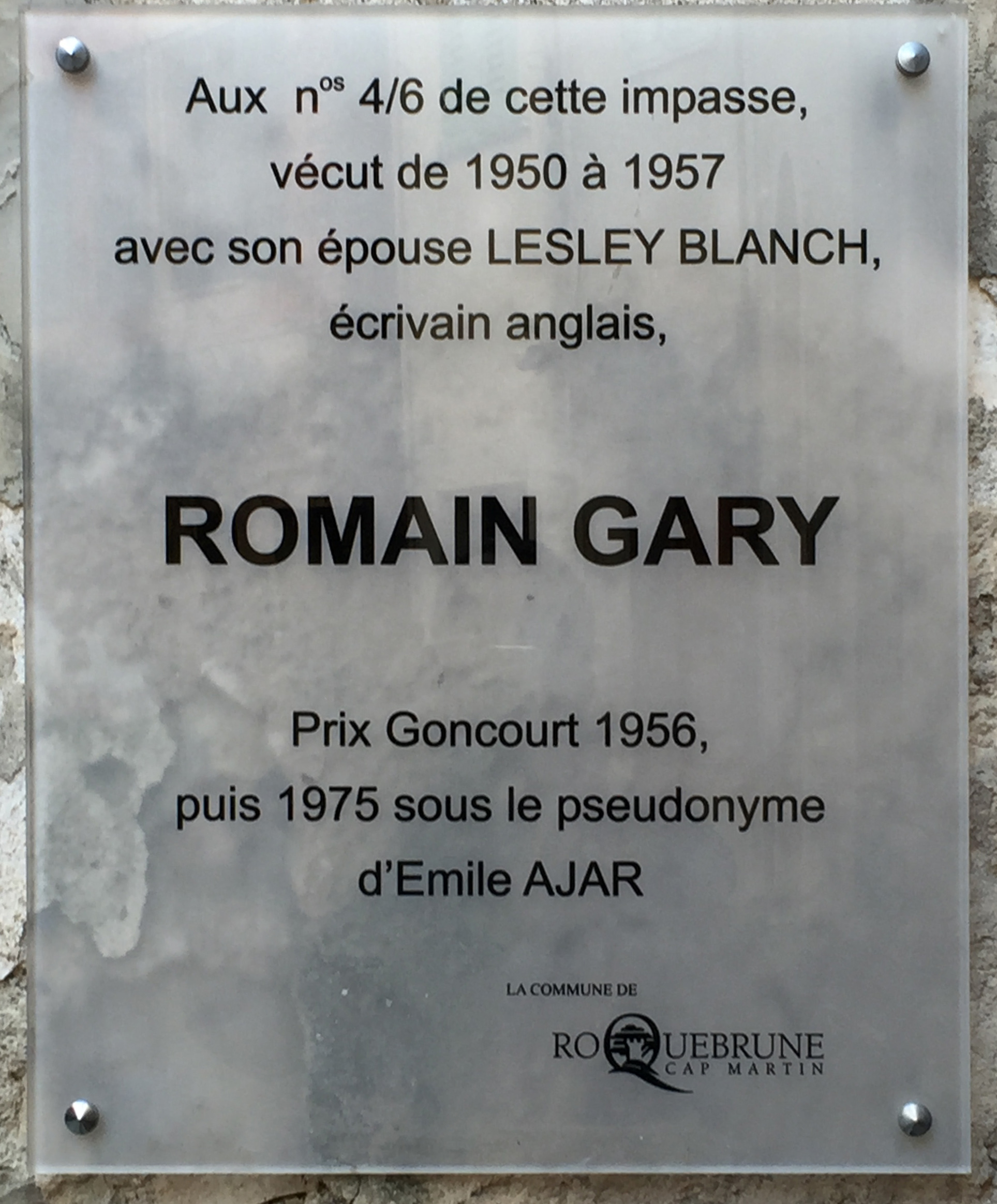

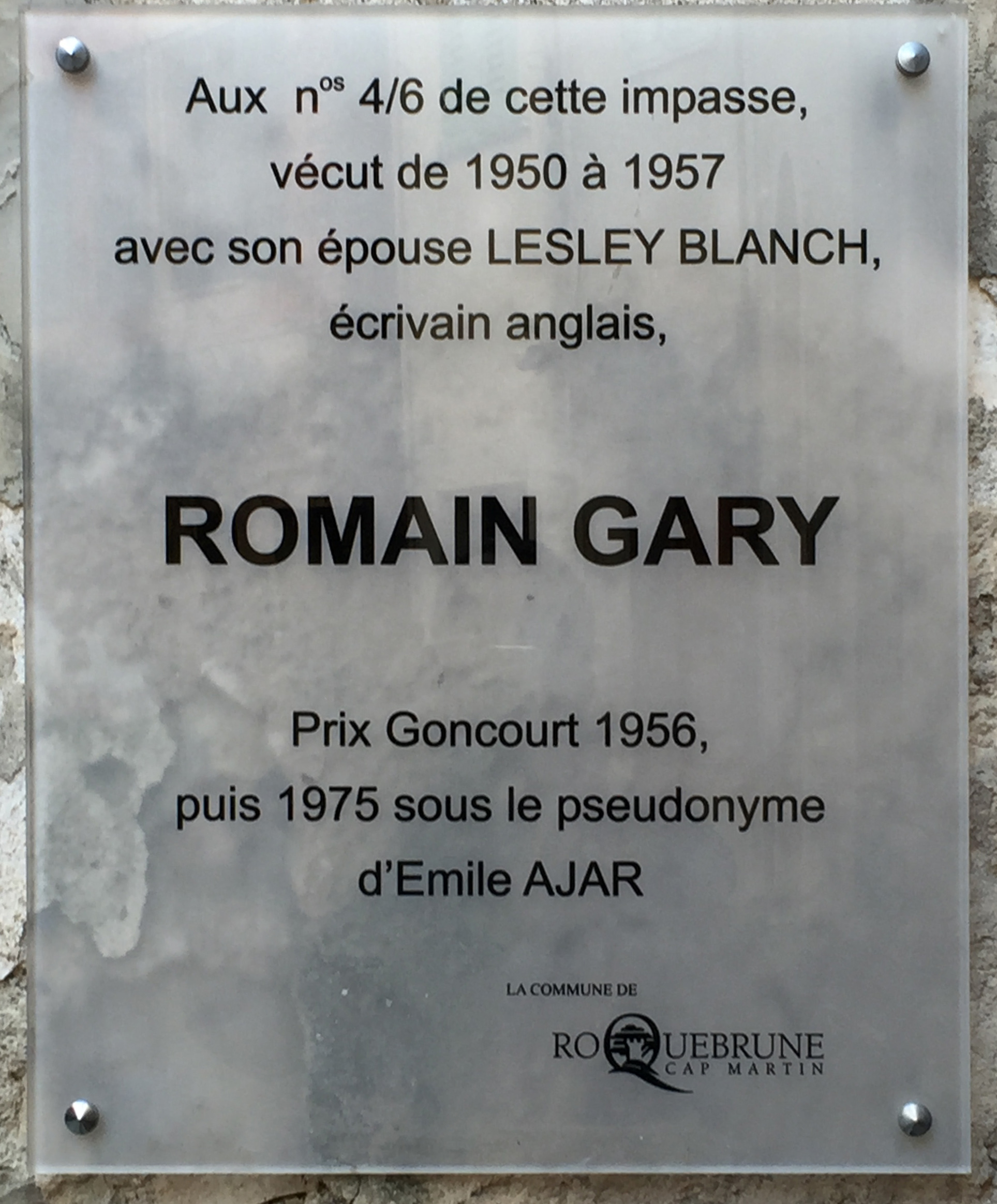

In a memoir published in 1981, Gary's nephew Paul Pavlowitch claimed that Gary also produced several works under the pseudonym Ămile Ajar. Gary recruited Pavlowitch to portray Ajar in public appearances, allowing Gary to remain unknown as the true producer of the Ajar works, and thus enabling him to win the 1975 Goncourt Prize, a second win in violation of the prize's usual rules. Gary also published under the pseudonyms Shatan Bogat and Fosco Sinibaldi.Literary work

Gary became one of France's most popular and prolific writers, writing more than 30 novels, essays and memoirs, some of which he wrote under a pseudonym.

He is the only person to win the

Gary became one of France's most popular and prolific writers, writing more than 30 novels, essays and memoirs, some of which he wrote under a pseudonym.

He is the only person to win the Prix Goncourt

The Prix Goncourt (french: Le prix Goncourt, , ''The Goncourt Prize'') is a prize in French literature, given by the acadĂŠmie Goncourt to the author of "the best and most imaginative prose work of the year". The prize carries a symbolic reward o ...

twice. This prize for French language literature is awarded only once to an author. Gary, who had already received the prize in 1956 for ''Les racines du ciel

''The Roots of Heaven'' (french: Les Racines du ciel) is a 1956 novel by the Lithuanian-born French writer and WW II aviator, Romain Gary (born Roman Kacew). It received the Prix Goncourt for fiction. It was translated into English in 1957.

Syno ...

'', published ''La vie devant soi

''The Life Before Us'' (1975; French: ''La vie devant soi'') is a novel by French author Romain Gary who wrote it under the pseudonym of "Emile Ajar". It was originally published in English as ''Momo'' translated by Ralph Manheim, then re-publis ...

'' under the pseudonym Ămile Ajar in 1975. The AcadĂŠmie Goncourt

The SociĂŠtĂŠ littĂŠraire des Goncourt (Goncourt Literary Society), usually called the AcadĂŠmie Goncourt (Goncourt Academy), is a French literary organisation based in Paris. It was founded in 1900 by the French writer and publisher Edmond de Go ...

awarded the prize to the author of that book without knowing his identity. Gary's cousin's son Paul Pavlowitch posed as the author for a time. Gary later revealed the truth in his posthumous book '' Vie et mort d'Ămile Ajar''. Gary also published as Shatan Bogat, RenĂŠ Deville and Fosco Sinibaldi, as well under his birth name Roman Kacew.

In addition to his success as a novelist, he wrote the screenplay for the motion picture '' The Longest Day'' and co-wrote and directed the film ''Kill!'' (1971), which starred his wife at the time, Jean Seberg

Jean Dorothy Seberg (; ; November 13, 1938August 30, 1979) was an American actress who lived half of her life in France. Her performance in Jean-Luc Godard's 1960 film ''Breathless'' immortalized her as an icon of French New Wave cinema.

Seb ...

. In 1979, he was a member of the jury at the 29th Berlin International Film Festival

The 29th Berlin International Film Festival was held from 20 February â 3 March 1979. The Golden Bear was awarded to the West German film ''David'' directed by Peter Lilienthal.

Michael Cimino's ''The Deer Hunter'' was surrounded by controver ...

.

Diplomatic career

After the end of the hostilities, Gary began a career as adiplomat

A diplomat (from grc, δίĎÎťĎΟι; romanized ''diploma'') is a person appointed by a state or an intergovernmental institution such as the United Nations or the European Union to conduct diplomacy with one or more other states or internati ...

in the service of France, in consideration of the services rendered for his release. In this capacity, he held positions in Bulgaria (1946â1947), Paris (1948â1949), Switzerland (1950â1951), New York (1951â1954) â at the Permanent Mission of France to the United Nations, where he regularly rubs shoulders with the Jesuit Teilhard de Chardin

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin ( (); 1 May 1881 â 10 April 1955) was a French Jesuit priest, scientist, paleontologist, theologian, philosopher and teacher. He was Darwinian in outlook and the author of several influential theological and philo ...

, whose personality deeply marked him and inspired him, particularly for the character of Father Tassin in ''Les Racines du ciel

''The Roots of Heaven'' (french: Les Racines du ciel) is a 1956 novel by the Lithuanian-born French writer and WW II aviator, Romain Gary (born Roman Kacew). It received the Prix Goncourt for fiction. It was translated into English in 1957.

Syno ...

''âin London (1955), then as Consul General of France in Los Angeles (1956â1960). Back in Paris, he remained unassigned until he was laid off from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (1961).

Personal life and final years

Gary's first wife was the British writer,

Gary's first wife was the British writer, journalist

A journalist is an individual that collects/gathers information in form of text, audio, or pictures, processes them into a news-worthy form, and disseminates it to the public. The act or process mainly done by the journalist is called journalism ...

, and ''Vogue

Vogue may refer to:

Business

* ''Vogue'' (magazine), a US fashion magazine

** British ''Vogue'', a British fashion magazine

** ''Vogue Arabia'', an Arab fashion magazine

** ''Vogue Australia'', an Australian fashion magazine

** ''Vogue China'', ...

'' editor Lesley Blanch

Lesley Blanch, MBE, FRSL (6 June 1904, London â 7 May 2007, Garavan near Menton, France) was a British writer, historian and traveller. She is best known for '' The Wilder Shores of Love'', about Isabel Burton (who married the Arabist and ex ...

, author of '' The Wilder Shores of Love''. They married in 1944 and divorced in 1961. From 1962 to 1970, Gary was married to American actress Jean Seberg

Jean Dorothy Seberg (; ; November 13, 1938August 30, 1979) was an American actress who lived half of her life in France. Her performance in Jean-Luc Godard's 1960 film ''Breathless'' immortalized her as an icon of French New Wave cinema.

Seb ...

, with whom he had a son, Alexandre Diego Gary. According to Diego Gary, he was a distant presence as a father: "Even when he was around, my father wasn't there. Obsessed with his work, he used to greet me, but he was elsewhere."

After learning that Jean Seberg had had an affair with Clint Eastwood

Clinton Eastwood Jr. (born May 31, 1930) is an American actor and film director. After achieving success in the Western TV series '' Rawhide'', he rose to international fame with his role as the "Man with No Name" in Sergio Leone's "''Doll ...

, Gary challenged him to a duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people, with matched weapons, in accordance with agreed-upon Code duello, rules.

During the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier), duels were mostly single combats fought with swords (the r ...

, but Eastwood declined.

Gary died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound on 2 December 1980 in Paris. He left a note which said that his death had no relation to Seberg's suicide the previous year. He also stated in his note that he was Ămile Ajar.D. Bona, Romain Gary, Paris, Mercure de France-Lacombe, 1987, p. 397â398.

Gary was cremated in Père Lachaise Cemetery

Père Lachaise Cemetery (french: Cimetière du Père-Lachaise ; formerly , "East Cemetery") is the largest cemetery in Paris, France (). With more than 3.5 million visitors annually, it is the most visited necropolis in the world. Notable figures ...

and his ashes were scattered in the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

near Roquebrune-Cap-Martin

Roquebrune-Cap-Martin (; oc, Ròcabruna Caup Martin or ; it, Roccabruna-Capo Martino, ; Mentonasc: ''Rocabrßna''; Roquebrune until 1921) is a commune in the Alpes-Maritimes department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, Southeastern Fr ...

.Beyern, B., ''Guide des tombes d'hommes cÊlèbres'', Le Cherche Midi, 2008,

Legacy

The name of Romain Gary was given to a promotion of theĂcole nationale d'administration

The Ăcole nationale d'administration (generally referred to as ENA, en, National School of Administration) was a French ''grande ĂŠcole'', created in 1945 by President of France, President Charles de Gaulle and principal author of the Constitu ...

(2003â2005), the Institut d'ĂŠtudes politiques de Lille

Lille ( , ; nl, Rijsel ; pcd, Lile; vls, Rysel) is a city in the northern part of France, in French Flanders. On the river DeĂťle, near France's border with Belgium, it is the capital of the Hauts-de-France region, the prefecture of the No ...

(2013), the Institut rĂŠgional d'administration de Lille (2021â2022) and the Institut d'ĂŠtudes politiques de Strasbourg (2001â2002), in 2006 at Place Romain-Gary in the 15th arrondissement of Paris

15 (fifteen) is the natural number following 14 and preceding 16.

Mathematics

15 is:

* A composite number, and the sixth semiprime; its proper divisors being , and .

* A deficient number, a smooth number, a lucky number, a pernicious nu ...

and at the Nice Heritage Library. The French Institute in Jerusalem also bears the name of Romain Gary.

On 16 May 2019, his work appeared in two volumes in the Bibliothèque de la PlÊiade

The ''Bibliothèque de la PlÊiade'' (, "Pleiades Library") is a French editorial collection which was created in 1931 by Jacques Schiffrin, an independent young editor. Schiffrin wanted to provide the public with reference editions of the c ...

under the direction of Mireille Sacotte.

In 2007, a statue of Romualdas Kvintas, ÂŤThe Boy with a GalocheÂť, was unveiled, depicting the 9-year-old little hero of the Promise of Dawn, preparing to eat a shoe to seduce his little neighbor, Valentina. It is placed in Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the municipality of Vilnius). The population of Vilnius's functional urb ...

, in front of the BasanaviÄius, where the novelist lived.

A plaque to his name is affixed in the Pouillon building of the Faculty of Law and Political Science of Aix-Marseille where he studied.

In 2022, Denis MĂŠnochet

Denis MĂŠnochet (born 18 September 1976) is a French actor. MĂŠnochet is known to international audiences for his role as Perrier LaPadite, a French dairy farmer interrogated by the Nazis for harboring Jews in the 2009 Quentin Tarantino film ''I ...

portrayed Gary in '' White Dog (Chien blanc)'', a film adaptation by AnaĂŻs Barbeau-Lavalette

AnaĂŻs Barbeau-Lavalette (born 1979) is a Canadian novelist, film director, and screenwriter from Quebec. Her films are known for their "organic, participatory feel." Barbeau-Lavalette is the daughter of filmmaker Manon Barbeau and cinematogra ...

of Gary's 1970 book.Maxime Demers"ÂŤChien blancÂť: le goĂťt du risque d'AnaĂŻs Barbeau-Lavalette"

''

Le Journal de MontrĂŠal

''Le Journal de MontrĂŠal'' is a daily French-language tabloid newspaper published in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. It has the largest circulation of any newspaper in Quebec and is also the largest French-language daily newspaper in North America. ...

'', November 2, 2022.

Bibliography

As Romain Gary

* ''french: Ăducation europĂŠenne'' (1945); translated as '' Forest of Anger'' * ''french: Tulipe'' (1946); republished and modified in 1970. * '' Le Grand Vestiaire'' (1949); translated as ''The Company of Men'' (1950) * '' Les Couleurs du jour'' (1952); translated as '' The Colors of the Day'' (1953); filmed as ''The Man Who Understood Women

''The Man Who Understood Women'' is a 1959 American drama film written and directed by Nunnally Johnson from a novel by Romain Gary, and starring Henry Fonda, Leslie Caron, Renate Hoy and Cesare Danova.

Plot

Willie Bauche, a Hollywood producer, ...

'' (1959)

* ''Les Racines du ciel

''The Roots of Heaven'' (french: Les Racines du ciel) is a 1956 novel by the Lithuanian-born French writer and WW II aviator, Romain Gary (born Roman Kacew). It received the Prix Goncourt for fiction. It was translated into English in 1957.

Syno ...

'' â ''1956 Prix Goncourt''; translated as '' The Roots of Heaven'' (1957); filmed as '' The Roots of Heaven'' (1958)

* ''Lady L

''Lady L'' is a 1965 comedy film based on the novel by Romain Gary and directed by Peter Ustinov. Starring Sophia Loren, Paul Newman, David Niven and Cecil Parker, the film focuses on an elderly Corsican lady as she recalls the loves of her ...

'' (1958); self-translated and published in French in 1963; filmed as ''Lady L

''Lady L'' is a 1965 comedy film based on the novel by Romain Gary and directed by Peter Ustinov. Starring Sophia Loren, Paul Newman, David Niven and Cecil Parker, the film focuses on an elderly Corsican lady as she recalls the loves of her ...

'' (1965)

* ''La Promesse de l'aube'' (1960); translated as ''Promise at Dawn

''Promise at Dawn'' (french: La Promesse de l'aube) is a 1970 American drama film directed by Jules Dassin and starring Melina Mercouri, Dassin's wife. It is based on the 1960 novel ''Promise at Dawn'' (french: La Promesse de l'aube) by Romain ...

'' (1961); filmed as ''Promise at Dawn

''Promise at Dawn'' (french: La Promesse de l'aube) is a 1970 American drama film directed by Jules Dassin and starring Melina Mercouri, Dassin's wife. It is based on the 1960 novel ''Promise at Dawn'' (french: La Promesse de l'aube) by Romain ...

'' (1970) and again in 2017

* '' Johnie CĹur'' (1961, a theatre adaptation of "L'homme Ă la colombe")

* '' Gloire Ă nos illustres pionniers'' (1962, short stories); translated as "Hissing Tales" (1964)

* '' The Ski Bum'' (1965); self-translated into French as ''Adieu Gary Cooper'' (1969)

* '' Pour Sganarelle'' (1965, literary essay)

* '' Les Mangeurs d'ĂŠtoiles'' (1966); self-translated into French and first published (in English) as '' The Talent Scout'' (1961)

* '' La Danse de Gengis Cohn'' (1967); self-translated into English as ''The Dance of Genghis Cohn

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the m ...

''

* '' La TĂŞte coupable'' (1968); translated as ''The Guilty Head'' (1969)

* ''Chien blanc'' (1970); self-translated as '' White Dog'' (1970); filmed as '' White Dog'' (1982)

* '' Les TrĂŠsors de la mer Rouge'' (1971)

* ''Europa

Europa may refer to:

Places

* Europe

* Europa (Roman province), a province within the Diocese of Thrace

* Europa (Seville Metro), Seville, Spain; a station on the Seville Metro

* Europa City, Paris, France; a planned development

* Europa Cliff ...

'' (1972); translated in English in 1978.

* '' The Gasp'' (1973); self-translated into French as ''Charge d'âme'' (1978)

* '' Les Enchanteurs'' (1973); translated as ''The Enchanters'' (1975)

* '' La nuit sera calme'' (1974, interview)

* '' Au-delĂ de cette limite votre ticket n'est plus valable'' (1975); translated as ''Your Ticket Is No Longer Valid'' (1977); filmed as '' Your Ticket Is No Longer Valid'' (1981)

* '' Clair de femme'' (1977); filmed as ''Womanlight

''Womanlight'' (french: Clair de femme) is a 1979 film by Costa-Gavras based on the 1977 novel '' Clair de femme'' by Romain Gary.RazĂłn y fe: Revista hispano-americana de cultura 1979 En la actualidad Costaâ Gavras trabaja en el rodaje de su nu ...

'' (1979)

* '' La Bonne MoitiĂŠ'' (1979, play)

* '' Les Clowns lyriques'' (1979); new version of the 1952 novel, ''Les Couleurs du jour'' (''The Colors of the Day'')

* '' Les Cerfs-volants'' (1980); translated as The Kites (2017)

* '' Vie et Mort d'Ămile Ajar'' (1981, posthumous)

* '' L'Homme Ă la colombe'' (1984, definitive posthumous version)

* '' L'Affaire homme'' (2005, articles and interviews)

* '' L'Orage'' (2005, short stories and unfinished novels)

* ''Un humaniste

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

'', short story

As Ămile Ajar

* '' Gros câlin'' (1974); illustrated byJean-Michel Folon

Jean-Michel Folon (1 March 1934 â 20 October 2005) was a Belgian artist, illustrator, painter, and sculptor.

Early life

Folon was born on 1 March 1934 in Uccle, Brussels, Belgium in 1934. He studied architecture at the Institut Saint-Luc.

C ...

, filmed as '' Gros câlin'' (1979)

* ''La vie devant soi

''The Life Before Us'' (1975; French: ''La vie devant soi'') is a novel by French author Romain Gary who wrote it under the pseudonym of "Emile Ajar". It was originally published in English as ''Momo'' translated by Ralph Manheim, then re-publis ...

'' â ''1975 Prix Goncourt''; filmed as ''Madame Rosa

''Madame Rosa'' (french: La vie devant soi) is a 1977 French drama film directed by MoshĂŠ Mizrahi, adapted from the 1975 novel ''The Life Before Us'' by Romain Gary. It stars Simone Signoret and Samy Ben-Youb, and tells the story of an elderly ...

'' (1977); translated as "Momo" (1978); re-released as '' The Life Before Us'' (1986). Filmed as ''The Life Ahead

''The Life Ahead'' ( it, La vita davanti a sĂŠ) is a 2020 Italian drama film directed by Edoardo Ponti, from a screenplay by Ponti and Ugo Chiti. It is the third screen adaptation of the 1975 novel ''The Life Before Us'' by Romain Gary. It stars ...

'' (2020)

* ''Pseudo

The prefix pseudo- (from Greek ĎÎľĎ

δΎĎ, ''pseudes'', "false") is used to mark something that superficially appears to be (or behaves like) one thing, but is something else. Subject to context, ''pseudo'' may connote coincidence, imitation, ...

'' (1976)

* '' L'Angoisse du roi Salomon'' (1979); translated as ''King Solomon'' (1983).

* '' Gros câlin'' â new version including final chapter of the original and never published version.

As Fosco Sinibaldi

* '' L'homme Ă la colombe'' (1958)As Shatan Bogat

* '' Les tĂŞtes de StĂŠphanie'' (1974)Filmography

As screenwriter

*1958: '' The Roots of Heaven'' *1962: '' The Longest Day'' *1978: ''La vie devant soi

''The Life Before Us'' (1975; French: ''La vie devant soi'') is a novel by French author Romain Gary who wrote it under the pseudonym of "Emile Ajar". It was originally published in English as ''Momo'' translated by Ralph Manheim, then re-publis ...

''

As actor

*1936: '' Nitchevo'' â Le jeune homme au bastingage *1967: ''The Road to Corinth

''The Road to Corinth'' ( french: La route de Corinthe, it, Criminal story, also released as ''Who's Got the Black Box?'') is a 1967 French-Italian Eurospy film directed by Claude Chabrol.Marco Giusti. ''007 all'italiana''. Isbn Edizioni, 2010. . ...

'' â (uncredited) (final film role)

As director

*1968: '' Birds in Peru'' (''Birds in Peru'') starring Jean Seberg *1971: ''Kill! Kill! Kill! Kill!

''Kill! Kill! Kill! Kill!'' is a 1971 film written and directed by Romain Gary.

Cast

* Stephen Boyd as Brad Killian

* Jean Seberg as Emily Hamilton

* James Mason as Alan Hamilton

* Curd JĂźrgens as Grueningen

* Daniel Emilfork as Mejid

Receptio ...

'' also starring Jean Seberg

In popular culture

*2019: ''Seberg

''Seberg'' is a 2019 political thriller film directed by Benedict Andrews, from a screenplay by Joe Shrapnel and Anna Waterhouse based on the life of Jean Seberg. It stars Kristen Stewart, Jack O'Connell, Margaret Qualley, Zazie Beetz, Antho ...

'' , jouĂŠ par Yvan Attal Yvan is a given name. Notable people with the name include:

*Jacques-Yvan Morin, GOQ (born 1931), politician in Quebec, Canada

*Marc-Yvan CĂ´tĂŠ (born 1947), former Quebec politician and Cabinet Minister for the Quebec Liberal Party

*Maurice-Yvan S ...

References

Further reading

* Ajar, Ămile (Romain Gary), ''Hocus Bogus'',Yale University Press

Yale University Press is the university press of Yale University. It was founded in 1908 by George Parmly Day, and became an official department of Yale University in 1961, but it remains financially and operationally autonomous.

, Yale Universi ...

, 2010, 224p, (translation of ''Pseudo'' by David Bellos

David Bellos (born 1945) is an English-born translator and biographer. Bellos is Meredith Howland Pyne Professor of French Literature and Professor of Comparative Literature at Princeton University in the United States. He was director of Princeton ...

, includes ''The Life and Death of Ămile Ajar'')

* Anissimov, Myriam, ''Romain Gary, le camĂŠlĂŠon'' (DenoĂŤl 2004)

* Bellos, David, ''Romain Gary: A Tall Story'', Harvill Secker, 2010, 528p,

* Bellos, David. 2009. The cosmopolitanism of Romain Gary. ''Darbair ir Dienos'' (Vilnius) 51:63â69.

* Gary, Romain, ''Promise at Dawn'' (Revived Modern Classic), W.W. Norton

W. W. Norton & Company is an American publishing company based in New York City. Established in 1923, it has been owned wholly by its employees since the early 1960s. The company is known for its Norton Anthologies (particularly ''The Norton An ...

, 1988, 348p,

* Huston, Nancy, ''Tombeau de Romain Gary'' (Babel, 1997)

* Bona, Dominique, ''Romain Gary'' (Mercure de France, 1987)

* Cahier de l'Herne, ''Romain Gary'' (L'Herne, 2005)

* DÊsÊrable, François-Henri, ''Un certain M. Piekielny'', Gallimard, 2017,

*

* Blanch, Lesley, ''Romain, un regard particulier'' (Editions du Rocher, 2009)

* Marret, Carine, ''Romain Gary â Promenade Ă Nice'' (Baie des Anges, 2010)

* Marzorati, Michel (2018). Romain Gary: des racines et des ailes. ''Info-Pilote, 742'' pp. 30â33

* Spire, Kerwin, ''Monsieur Romain Gary'', Gallimard, 2021,

* Stjepanovic-Pauly, Marianne. Romain Gary La mĂŠlancolie de l'enchanteur. ''Editions du Jasmin,

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Gary, Romain 1914 births 1980 deaths Film people from Vilnius People from Vilensky Uyezd French people of Lithuanian-Jewish descent Lithuanian Jews Jews from the Russian Empire 20th-century French diplomats 20th-century French novelists French male novelists Jewish novelists Postmodern writers 20th-century French male writers Prix Goncourt winners French Royal Air Force pilots of World War II Suicides by firearm in France 1980 suicides Writers from Vilnius Jews in the French resistance French Resistance members