ûlvaro D'Ors Pûˋrez-Peix on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

ûlvaro Jordi d'Ors Rovira y Pûˋrez-Peix (14 April 1915 ã 1 February 2004) was a

DãOrsã first academic teaching contract is dated 1939; he obtained an auxiliary position at the chair of Roman law in Madrid. In 1940 he left for

DãOrsã first academic teaching contract is dated 1939; he obtained an auxiliary position at the chair of Roman law in Madrid. In 1940 he left for  There are conflicting views on dãOrsã didactical profile. The prevailing one is that though very diligent and ideologically uncompromising, as a colleague and mentor dãOrs remained extremely fair and very respectful towards his assistants and students. Perhaps even tending to excess benevolence, he allowed them a great deal of research liberty. According to his son, he had no personal enemies and never embarked on personal charges. However, a competitive view is that the above seems highly debatable, that he was very lenient only towards his disciples while remaining intransigent if not hostile towards those considered opponents, and that his judgment was seriously impaired by ideological fanaticism.

There are conflicting views on dãOrsã didactical profile. The prevailing one is that though very diligent and ideologically uncompromising, as a colleague and mentor dãOrs remained extremely fair and very respectful towards his assistants and students. Perhaps even tending to excess benevolence, he allowed them a great deal of research liberty. According to his son, he had no personal enemies and never embarked on personal charges. However, a competitive view is that the above seems highly debatable, that he was very lenient only towards his disciples while remaining intransigent if not hostile towards those considered opponents, and that his judgment was seriously impaired by ideological fanaticism.

Though dãOrs remained active on many scholarly fields, he considered himself and is most appreciated today as a Roman law scholar. His interest in

Though dãOrs remained active on many scholarly fields, he considered himself and is most appreciated today as a Roman law scholar. His interest in  The first major work published by dãOrs was ''Estudios sobre la Constitutio Antoniniana'' (1943), a multi-volume edition of his Ph.D. dissertation. The same year he released ''Presupuestos crûÙticos para el Estudio del Derecho Romano'', mostly a study on methodology and source criticism. ''Introducciû°n al estudio de los Documentos del Egipto romano'' (1948) was relatively minor compared to ''EpigrafûÙa jurûÙdica de la EspaûÝa romana'' (1953), by some considered his most important contribution to scholarship on Roman law. In 1960 dãOrs summarized his studies on Visigothic law in his monumental ''El Cû°digo de Eurico'' (1960). ''Elementos de Derecho romano'' (1960) was designed as textbook for students of Roman law, and following some changes re-appeared with 10 re-issues it served generations of Spanish students of law and was last published in 2017. Specific problems or municipal statutes was discussed in ''La ley Flavia municipal'' (1986) and ''Lex Irnitana'' (1988), while ''Las ãQuaestionesã de Africano'' (1997) provided an all-round description of judicial ideas of Sextus Caecilius Africanus. The last major work published was a set of essays, ''CrûÙtica romanûÙstica'' (1999). DãOrsã lesser works, mostly articles scattered across juridical press, run into the hundreds.

The first major work published by dãOrs was ''Estudios sobre la Constitutio Antoniniana'' (1943), a multi-volume edition of his Ph.D. dissertation. The same year he released ''Presupuestos crûÙticos para el Estudio del Derecho Romano'', mostly a study on methodology and source criticism. ''Introducciû°n al estudio de los Documentos del Egipto romano'' (1948) was relatively minor compared to ''EpigrafûÙa jurûÙdica de la EspaûÝa romana'' (1953), by some considered his most important contribution to scholarship on Roman law. In 1960 dãOrs summarized his studies on Visigothic law in his monumental ''El Cû°digo de Eurico'' (1960). ''Elementos de Derecho romano'' (1960) was designed as textbook for students of Roman law, and following some changes re-appeared with 10 re-issues it served generations of Spanish students of law and was last published in 2017. Specific problems or municipal statutes was discussed in ''La ley Flavia municipal'' (1986) and ''Lex Irnitana'' (1988), while ''Las ãQuaestionesã de Africano'' (1997) provided an all-round description of judicial ideas of Sextus Caecilius Africanus. The last major work published was a set of essays, ''CrûÙtica romanûÙstica'' (1999). DãOrsã lesser works, mostly articles scattered across juridical press, run into the hundreds.

DãOrsã theory of law was founded on distinction between authority (''autoridad'') and power (''poder''). Authority is derived from genuine wisdom, and this, in turn, is based not on human assertions, but may be ascertained through tradition and from the natural order, the latter founded on divine rules. Power, in turn, is a ruling structure; it must be based on authority, though it should remain separate from it. This ideal was best embodied in early

DãOrsã theory of law was founded on distinction between authority (''autoridad'') and power (''poder''). Authority is derived from genuine wisdom, and this, in turn, is based not on human assertions, but may be ascertained through tradition and from the natural order, the latter founded on divine rules. Power, in turn, is a ruling structure; it must be based on authority, though it should remain separate from it. This ideal was best embodied in early

The cornerstone of dãOrsã political theory is criticism of

The cornerstone of dãOrsã political theory is criticism of

Throughout most of his academic career, dãOrs pursued his interest in specific local legal establishments known as

Throughout most of his academic career, dãOrs pursued his interest in specific local legal establishments known as  DãOrs interest in jurisprudence also translated into his focus on

DãOrs interest in jurisprudence also translated into his focus on

The early 1960s mark the beginning of dãOrsã explicit engagement in Carlist labors. In 1962 he co-worked on a document, which legally backed citizenship claims of the Borbû°n-Parmas; it was presented to Franco during the prince's visit to

The early 1960s mark the beginning of dãOrsã explicit engagement in Carlist labors. In 1962 he co-worked on a document, which legally backed citizenship claims of the Borbû°n-Parmas; it was presented to Franco during the prince's visit to  Since the early 1960s, Carlism was increasingly divided between an emergent progressist faction centred around Don Carlos Hugo and the Traditionalist core. In the mid-1960s, the progressists were already in control of key institutions of the movement. There is no information on dãOrsã taking part in the internal power struggle. Though ideologically he was the key representative of Traditionalist orthodoxy and spoke out against subversive, revolutionary currents, marked by the deification of democracy and human rights, until 1968 he was among authors most frequently published in the carlo-huguista review, ''

Since the early 1960s, Carlism was increasingly divided between an emergent progressist faction centred around Don Carlos Hugo and the Traditionalist core. In the mid-1960s, the progressists were already in control of key institutions of the movement. There is no information on dãOrsã taking part in the internal power struggle. Though ideologically he was the key representative of Traditionalist orthodoxy and spoke out against subversive, revolutionary currents, marked by the deification of democracy and human rights, until 1968 he was among authors most frequently published in the carlo-huguista review, ''

As an

As an

DãOrs established his position among the best Spanish experts in Roman law following the 1953 publication of ''EpigrafûÙa jurûÙdica''. However, he became known nationally upon receiving

DãOrs established his position among the best Spanish experts in Roman law following the 1953 publication of ''EpigrafûÙa jurûÙdica''. However, he became known nationally upon receiving  Attempts to classify dãOrsã thought in terms of any specific school or current are fairly rare. Some consider him the member of an intellectual formation named ãgeneration 48ã; others ponder upon the labels of ãescolûÀsticoã or ãrealistaã; in the theory of law clearly supporter of natural law school, in the theory of politics he is also decisively categorized as a Traditionalist. All scholars underline his intellectual kinship to

Attempts to classify dãOrsã thought in terms of any specific school or current are fairly rare. Some consider him the member of an intellectual formation named ãgeneration 48ã; others ponder upon the labels of ãescolûÀsticoã or ãrealistaã; in the theory of law clearly supporter of natural law school, in the theory of politics he is also decisively categorized as a Traditionalist. All scholars underline his intellectual kinship to

d'Ors at University of Navarre website

d'Ors at University Carlos III website

''Por Dios y por EspaûÝa''; contemporary Carlist propaganda

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ors Perez Preix, Alvaro d' Canon law jurists Carl Schmitt scholars Carlists Francoist Spain Male essayists Roman Catholic writers Spanish anti-communists 20th-century Spanish historians Spanish educational theorists Spanish essayists Spanish male writers Spanish monarchists Spanish military personnel of the Spanish Civil War (National faction) Spanish philosophers Spanish politicians Spanish Roman Catholics Academic staff of the University of Coimbra Academic staff of the University of Granada Academic staff of the University of Navarra Academic staff of the University of Santiago de Compostela 20th-century Spanish lawyers 1915 births 2004 deaths

Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

scholar of Roman law

Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the '' Corpus Juris Civilis'' (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor Ju ...

, currently considered one of the best 20th-century experts on the field; he served as professor at the universities of Santiago de Compostela

Santiago de Compostela is the capital of the autonomous community of Galicia, in northwestern Spain. The city has its origin in the shrine of Saint James the Great, now the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, as the destination of the Way of S ...

and Pamplona

Pamplona (; eu, IruûÝa or ), historically also known as Pampeluna in English, is the capital city of the Chartered Community of Navarre, in Spain. It is also the third-largest city in the greater Basque cultural region.

Lying at near above ...

. He was also theorist of law and political theorist

A political theorist is someone who engages in constructing or evaluating political theory, including political philosophy. Theorists may be Academia, academics or independent scholars. Here the most notable political theorists are categorized b ...

, responsible for development of Traditionalist vision of state and society. Politically he supported the Carlist

Carlism ( eu, Karlismo; ca, Carlisme; ; ) is a Traditionalist and Legitimist political movement in Spain aimed at establishing an alternative branch of the Bourbon dynasty ã one descended from Don Carlos, Count of Molina (1788ã1855) ã ...

cause. Though he did not hold any official posts within the organization, he counted among top intellectuals of the movement; he was member of the advisory council of the Carlist claimant.

Family and youth

The Ors family has been for centuries related toCatalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, CataluûÝa ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a '' nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the nort ...

, its origins traced back to Lerida. The great-grandfather of ûlvaro, Joan Ors Font, was the native of Sabadell; his son and ûlvaro's paternal grandfather, Josûˋ Ors Rosal, settled in Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

and since the 1880s he practiced as doctor in the Santa Creu hospital. He married a girl from an enriched indiano family, born in Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, Repû¤blica de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

though related to Vilafranca del Penedû´s

Vilafranca del Penedû´s, or simply Vilafranca (), is the capital of the ''comarca'' of the Alt Penedû´s in Catalonia, Spain. The Spanish spelling of the name, ''Villafranca del Panadûˋs'', is no longer in official use since 1982 (Law 12/1982, of ...

. Their son and the father of ûlvaro, Eugenio Ors Rovira (1881-1954), in the 1910s emerged among protagonists of cultural life in Catalonia; he later changed his surname to dãOrs. In the 1920s he grew to nationally recognized figure as publisher, essayist, art critic, writer and philosopher; in the Francoist

Francoist Spain ( es, EspaûÝa franquista), or the Francoist dictatorship (), was the period of Spanish history between 1939 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death in 1975, Spai ...

Spain he held high jobs related to culture. Currently he is considered one of key representatives of late Spanish Modernism

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

and Catalan cultural renaissance. In 1906 he married MarûÙa Pûˋrez Peix (1879-1972), daughter to a successful textile business entrepreneur from Barcelona; a cultured person with artistic penchant, she tried her hand in music, dance, guitar, photography and especially sculpture.

The couple settled in Barcelona; they had three children, all of them sons; ûlvaro was born as the youngest one. He was raised in luxurious and bohemian atmosphere, since childhood traveling extensively abroad due to professional assignments of his father; in 1922 the family moved to Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the Largest cities of the Europ ...

. First educated by his mother, in 1923-1932 he frequented Instituto-Escuela, an establishment known for its liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

profile; it is there he obtained the baccalaureate Baccalaureate may refer to:

* ''Baccalaurûˋat'', a French national academic qualification

* Bachelor's degree, or baccalaureate, an undergraduate academic degree

* English Baccalaureate, a performance measure to assess secondary schools in England ...

. In 1932 dãOrs enrolled at law and in 1933 at philosophy and letters. Outbreak of the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

caught him at the family estate in Argentona

Argentona is a municipality in the ''comarca'' of the Maresme in Catalonia, Spain. It is situated on the south-east side of the granite Litoral range, to the north-west of Matarû°. The town is both a tourist centre and a notable horticultural cen ...

. Fearing repression due to pro-Nationalist stand assumed in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 kmôý (41 sq mi), ma ...

by his father, ûlvaro opted for self-confinement. In mid-1937, he crossed the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyrûˋnûˋes ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Pirenû´us ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to ...

and through France, he made it to the Nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

zone. Drafted to the army he deserted and volunteered to the Carlist troops, serving in requetûˋ

The Requetûˋ () was a Carlist organization, at times with paramilitary units, that operated between the mid-1900s and the early 1970s, though exact dates are not clear.

The Requetûˋ formula differed over the decades, and according to its chan ...

units until 1939. Released, the same year he graduated in law and obtained a teaching contract at Universidad Central.

In 1945 dãOrs married Palmira Lois Estûˋvez (1920-2003), his student and daughter to a local Galician lawyer; until 1961 they lived in Santiago de Compostela

Santiago de Compostela is the capital of the autonomous community of Galicia, in northwestern Spain. The city has its origin in the shrine of Saint James the Great, now the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, as the destination of the Way of S ...

, and later on in Pamplona

Pamplona (; eu, IruûÝa or ), historically also known as Pampeluna in English, is the capital city of the Chartered Community of Navarre, in Spain. It is also the third-largest city in the greater Basque cultural region.

Lying at near above ...

. The couple had 11 children, born between the mid-1940s and the mid-1960s. Three sons became academics: Miguel dãOrs Lois in literature (Pamplona, Granada), though he gained some recognition also as a poet, Javier in law (Santiago, Leû°n) and Angel in philosophy (Pamplona, Madrid). Daughters became local editors, historians or art critics; one daughter was mentally impaired and passed away prematurely. The best known of dãOrsã grandchildren are Laura dãOrs Vilardebo, a photographer and art critic, and Diego dãOrs Vilardebû°, a musician. Among ûlvaro's nephews, a Catholic priest Pablo dãOrs Fû¥hrer is a writer and Juan dãOrs Fû¥hrer a musician. Both ûlvaro's brothers served as requetûˋs and one in Division Azul in Russia; VûÙctor gained some nationwide recognition as an architect and author of related books.

Academic career

DãOrsã first academic teaching contract is dated 1939; he obtained an auxiliary position at the chair of Roman law in Madrid. In 1940 he left for

DãOrsã first academic teaching contract is dated 1939; he obtained an auxiliary position at the chair of Roman law in Madrid. In 1940 he left for Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, where under the guidance of Emilio Albertario dãOrs pursued research related to his PhD dissertation

A thesis ( : theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144: ...

. It materialized as a thesis on Constitutio Antoniniana

The ''Constitutio Antoniniana'' (Latin for: "Constitution r Edictof Antoninus") (also called the Edict of Caracalla or the Antonine Constitution) was an edict issued in AD 212, by the Roman Emperor Caracalla. It declared that all free men in t ...

, accepted cum laude at Universidad Central in 1941. Following vacancies at the chairs of Roman law in Granada and Las Palmas

Las Palmas (, ; ), officially Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, is a Spanish city and capital of Gran Canaria, in the Canary Islands, on the Atlantic Ocean.

It is the capital (jointly with Santa Cruz de Tenerife), the most populous city in the auto ...

he applied and emerged successful over two counter-candidates. Entitled to choose his seat he opted for Granada, where dãOrs was teaching Roman law

Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the '' Corpus Juris Civilis'' (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor Ju ...

in 1943ã1944. In 1944 he swooped chairs and moved to Universidad de Santiago de Compostela

, established =

, type = Public

, budget = ã˜228 million (2011)

, rector = Prof. Dr. Antonio Lû°pez DûÙaz

, city = Santiago de Compostela

, state = Galicia

, country = Spain

, undergrad = 23,835

, postgrad = 1,716

, doctoral = 2,697

, ...

, the institution he co-operated with since the early 1940s.

In addition to Roman law, d'Ors was periodically teaching Civil Law and History of Law

Legal history or the history of law is the study of how law has evolved and why it has changed. Legal history is closely connected to the development of civilisations and operates in the wider context of social history. Certain jurists and hist ...

; in the late 1940s, he held the job of Library Director of the University of Santiago. During his Santiago spell he was also heading the library of the School of Law. In 1948 he commenced long-lasting co-operation with University of Coimbra

The University of Coimbra (UC; pt, Universidade de Coimbra, ) is a public research university in Coimbra, Portugal. First established in Lisbon in 1290, it went through a number of relocations until moving permanently to Coimbra in 1537. The u ...

. In 1953 he was nominated head of the Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Vatican City, the city-state ruled by the pope in Rome, including St. Peter's Basilica, Sistine Chapel, Vatican Museum

The Holy See

* The Holy See, the governing body of the Catholic Church and sovereign entity recognized ...

-based Istituto Giuridico Spagnolo; until 1973 dãOrs would lead its works. Though he felt very well in Santiago, in 1960 and reportedly due to influence of Josûˋ MarûÙa Escriva dãOrs moved to the newly set up University of Navarra

, image = UNAV.svg

, latin_name = Universitas Studiorum Navarrensis

, established = 17 October 1952

, type = Private, Roman Catholic

, chancellor = Fernando OcûÀriz BraûÝa

, president = MarûÙa Iraburu Eliz ...

, a corporate work of Opus Dei. Since 1961 for the following 24 years he continued as chair of Roman law; until 1972 he served also as Library Director and was responsible for setting up and managing the School of Librarians. Though in the early 1980s he was pondering upon return to Santiago he retired

Retirement is the withdrawal from one's position or occupation or from one's active working life. A person may also semi-retire by reducing work hours or workload.

Many people choose to retire when they are elderly or incapable of doing their j ...

in Pamplona in 1985; until 1989 he contributed as professor emeritus

''Emeritus'' (; female: ''emerita'') is an adjective used to designate a retired chair, professor, pastor, bishop, pope, director, president, prime minister, rabbi, emperor, or other person who has been "permitted to retain as an honorary title ...

and until death as honorary professor.

Apart from strictly academic institutions, in the 1940s dãOrs was active in Centro de Estudios Histû°ricos

Centro may refer to:

Places Brazil

*Centro, Santa Maria, a neighborhood in Santa Maria, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

* Centro, Porto Alegre, a neighborhood of Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

*Centro (Duque de Caxias), a neighborhood of Duq ...

, Instituto Nacional de Estudios JurûÙdicos, Instituto Nebrija de Estudios ClûÀsicos, and in Consejo Superior de Investigaciones CientûÙficas

The Spanish National Research Council ( es, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones CientûÙficas, CSIC) is the largest public institution dedicated to research in Spain and the third largest in Europe. Its main objective is to develop and promote res ...

. During long spells he remained in editorial boards of numerous periodicals, notably ''Emerita'', '' Anuario de Historia del Derecho EspaûÝol'', ''Revista de Estudios Histû°rico-JurûÙdicos'', ''Revue Internationale des Droits de lãAntiquitûˋ'' and ''Studia et Documenta''. DãOrs was member of numerous scientific organisations in Spain and abroad. He kept writing throughout all his life; it is estimated that dãOrs wrote some 600ã800 academic publications, plus thousands of op-eds

An op-ed, short for "opposite the editorial page", is a written prose piece, typically published by a North-American newspaper or magazine, which expresses the opinion of an author usually not affiliated with the publication's editorial board. ...

and other pieces.

Roman law scholar

Though dãOrs remained active on many scholarly fields, he considered himself and is most appreciated today as a Roman law scholar. His interest in

Though dãOrs remained active on many scholarly fields, he considered himself and is most appreciated today as a Roman law scholar. His interest in ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753ã509 BC ...

originated from juvenile visits in the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

, but was later cultivated and developed by his academic masters Josûˋ Castillejo and Ursicino Alvarez. He also admitted masterly influence of Theodor Mommsen

Christian Matthias Theodor Mommsen (; 30 November 1817 ã 1 November 1903) was a German classical scholar, historian, jurist, journalist, politician and archaeologist. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest classicists of the 19th centu ...

, Otto Lenel

Otto Lenel (13 December 1849 ã 7 February 1935) was a German Jewish jurist and legal historian. His most important achievements are in the field of Roman law.

Life and career

Otto Lenel was born in Mannheim, Germany on 13 December 1849. He was ...

, Leopold Wenger, Emilio Albertario; the peers he was indebted to were mostly Max Kaser and Franz Wieacker.

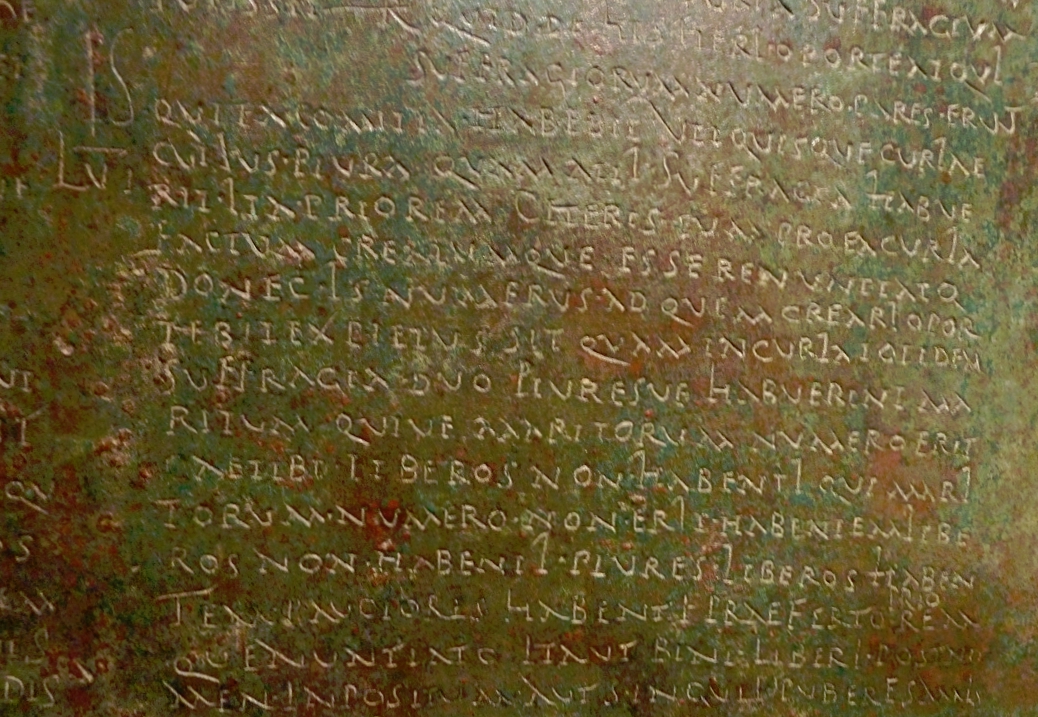

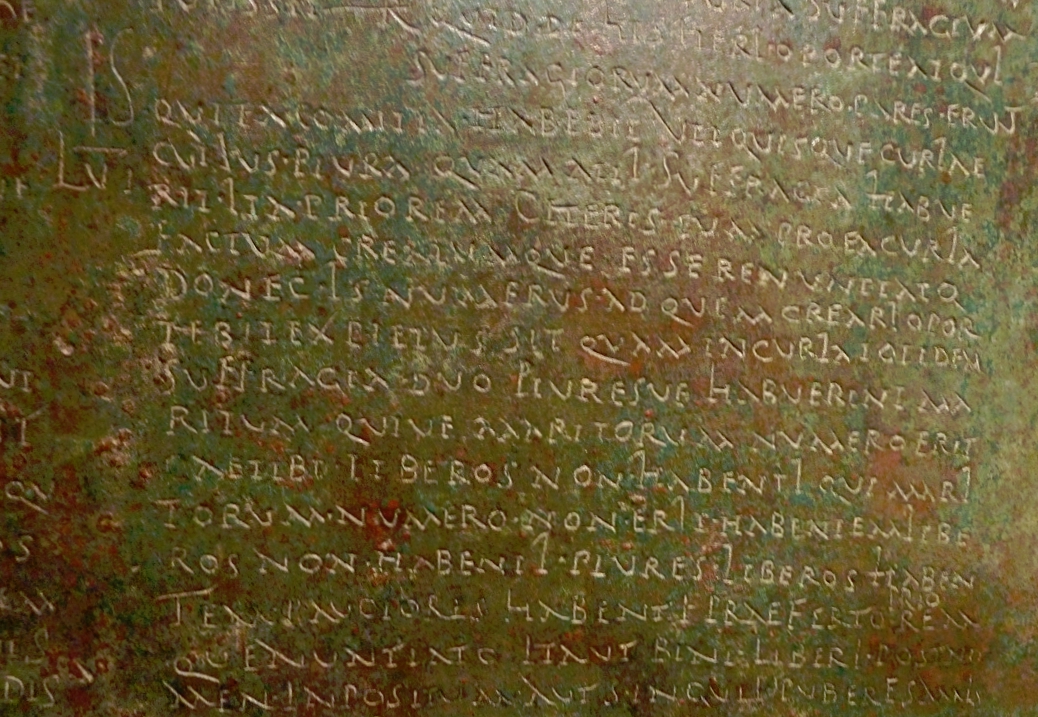

In terms of specific issues tackled, chronologically the first was the problem of Roman citizenship

Citizenship is a "relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection".

Each state determines the conditions under which it will recognize persons as its citizens, and ...

regulations; dãOrs offered a new view of Edict of Caracalla

The ''Constitutio Antoniniana'' (Latin for: "Constitution r Edictof Antoninus") (also called the Edict of Caracalla or the Antonine Constitution) was an edict issued in AD 212, by the Roman Emperor Caracalla. It declared that all free men in t ...

and challenged the previously dominating, so-called interpolationist theory. Another thread of his research was contractual agreements, and particularly credit; dãOrs questioned the fourfold classification of contracts and emphasized their bilateral nature. Throughout his career he dedicated much attention to municipal law, especially during the Flavian era. D'Ors also focused on the reconstruction of the praetor's edicts, improving thus earlier reconstructions offered by Adolf Friedrich Rudorff and Otto Lenel. He dedicated much work to Visigothic law, pursuing a territorialist thesis against personalism of Germanic law. Last but not least, he offered an extensive analysis of the juridical thought of the Roman jurist Sextus Caecilius Africanus.

Methodologically, dãOrs advocated much stricter and rigorous approach related to source criticism, especially concerning Roman legal sources; this view constituted the guiding thread of his research and together with works of ûlvarez contributed to a new turn in the research of Roman law in Spain. His own specific approach consisted of particular focus on so far underestimated sources, namely papyrology

Papyrology is the study of manuscripts of ancient literature, correspondence, legal archives, etc., preserved on portable media from antiquity, the most common form of which is papyrus, the principal writing material in the ancient civilizations ...

and epigraphy; in the early 1950s he collected and extensively commented on all known epigraphic fragments related to juridical order in Roman Spain

Hispania ( la, Hispánia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: Hispania ...

, and later on followed new discoveries, esp. on so-called '' Lex Flavia'' and '' Lex Irnitana'' in the 1980s.

The first major work published by dãOrs was ''Estudios sobre la Constitutio Antoniniana'' (1943), a multi-volume edition of his Ph.D. dissertation. The same year he released ''Presupuestos crûÙticos para el Estudio del Derecho Romano'', mostly a study on methodology and source criticism. ''Introducciû°n al estudio de los Documentos del Egipto romano'' (1948) was relatively minor compared to ''EpigrafûÙa jurûÙdica de la EspaûÝa romana'' (1953), by some considered his most important contribution to scholarship on Roman law. In 1960 dãOrs summarized his studies on Visigothic law in his monumental ''El Cû°digo de Eurico'' (1960). ''Elementos de Derecho romano'' (1960) was designed as textbook for students of Roman law, and following some changes re-appeared with 10 re-issues it served generations of Spanish students of law and was last published in 2017. Specific problems or municipal statutes was discussed in ''La ley Flavia municipal'' (1986) and ''Lex Irnitana'' (1988), while ''Las ãQuaestionesã de Africano'' (1997) provided an all-round description of judicial ideas of Sextus Caecilius Africanus. The last major work published was a set of essays, ''CrûÙtica romanûÙstica'' (1999). DãOrsã lesser works, mostly articles scattered across juridical press, run into the hundreds.

The first major work published by dãOrs was ''Estudios sobre la Constitutio Antoniniana'' (1943), a multi-volume edition of his Ph.D. dissertation. The same year he released ''Presupuestos crûÙticos para el Estudio del Derecho Romano'', mostly a study on methodology and source criticism. ''Introducciû°n al estudio de los Documentos del Egipto romano'' (1948) was relatively minor compared to ''EpigrafûÙa jurûÙdica de la EspaûÝa romana'' (1953), by some considered his most important contribution to scholarship on Roman law. In 1960 dãOrs summarized his studies on Visigothic law in his monumental ''El Cû°digo de Eurico'' (1960). ''Elementos de Derecho romano'' (1960) was designed as textbook for students of Roman law, and following some changes re-appeared with 10 re-issues it served generations of Spanish students of law and was last published in 2017. Specific problems or municipal statutes was discussed in ''La ley Flavia municipal'' (1986) and ''Lex Irnitana'' (1988), while ''Las ãQuaestionesã de Africano'' (1997) provided an all-round description of judicial ideas of Sextus Caecilius Africanus. The last major work published was a set of essays, ''CrûÙtica romanûÙstica'' (1999). DãOrsã lesser works, mostly articles scattered across juridical press, run into the hundreds.

Theorist of law

DãOrsã theory of law was founded on distinction between authority (''autoridad'') and power (''poder''). Authority is derived from genuine wisdom, and this, in turn, is based not on human assertions, but may be ascertained through tradition and from the natural order, the latter founded on divine rules. Power, in turn, is a ruling structure; it must be based on authority, though it should remain separate from it. This ideal was best embodied in early

DãOrsã theory of law was founded on distinction between authority (''autoridad'') and power (''poder''). Authority is derived from genuine wisdom, and this, in turn, is based not on human assertions, but may be ascertained through tradition and from the natural order, the latter founded on divine rules. Power, in turn, is a ruling structure; it must be based on authority, though it should remain separate from it. This ideal was best embodied in early Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

, but it started to crack when haruspices

In the religion of ancient Rome, a haruspex (plural haruspices; also called aruspex) was a person trained to practise a form of divination called haruspicy (''haruspicina''), the inspection of the entrails ('' exta''—hence also extispicy ...

replaced augurs

An augur was a priest and official in the classical Roman world. His main role was the practice of augury, the interpretation of the will of the gods by studying the flight of birds. Determinations were based upon whether they were flying in ...

. The distinction between authority and power was eventually blurred following the rise of Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

and ensuing religious wars. Rulers assumed the role of authority; as it was no longer possible to appeal to ''autoridad'' against the injustice of ''poder'', the result was the curtailment of liberty.

Another pair was legitimacy (''legitimidad'', based on ''ius'') and legality (''legalidad'', based on ''lex''). According to dãOrs, the former is an order stemming from an authority, while the latter is declared by power. The two are not necessarily incompatible; in fact, they should be complementary. However, due to blurred distinction between ''autoridad'' and ''poder'', natural law

Natural law ( la, ius naturale, ''lex naturalis'') is a system of law based on a close observation of human nature, and based on values intrinsic to human nature that can be deduced and applied independently of positive law (the express enacte ...

was challenged by positive law. DãOrs confronted the law which claimed to be tantamount to legitimacy. To him, the legal system produced by contractual and/or voluntarist concept was by default flawed, as he declared ãsocial contractã and ãwill of the peopleã a myth. One more distinction, only marginally related to the theory of law, was this between ownership (''propiedad'') and possession (''posesiû°n''). DãOrs challenged claims raised by modern states as unduly based on abuse of possession; he also confronted the capitalist

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, priva ...

order, based on the exaltation of property.

A concept related to dãOrs theory of law was violence. He viewed it as an intrinsic part of human history, usually coming to the forefront when an existing order was cracking or collapsing. Since dãOrs at times declared himself to be a ãrealist,ã he considered it in extremis necessary to resolve to violent means, especially when defending natural order against chaos and disorder. In fact, as long as violence was stemming from an authority, it formed part of ''ius'', even in case it was not compatible with ''lex''.

DãOrsã general theory of law is by some named philosophy of law and by others juridical-political philosophy. It is noted that because of its implications, ãit is sometimes not easy to distinguish dãOrs's political theory from his legal theoryã. In contrast to his romanist teachings, DãOrs theory of law and juridical order has been presented neither in systematic lecture nor structured analysis. It was exposed in numerous press publications, private letters, some paragraphs and sub-chapters in his Roman law works, and above all in essays, most of them collected in separate volumes. The two which stand out are ''Escritos varios sobre el Derecho en crisis'' (1973) and ''Derecho y Sentido Comû¤n'' (1995); some pieces were published in more heterogeneous collections, like ''Papeles del Oficio Universitario'' (1961), ''Nuevos Papeles del Oficio Universitario'' (1980), ''Cartas a un joven estudiante'' (1991), and ''Parerga histû°rica'' (1997).

Political theorist

The cornerstone of dãOrsã political theory is criticism of

The cornerstone of dãOrsã political theory is criticism of modern state

A state is a centralized political organization that imposes and enforces rules over a population within a territory. There is no undisputed definition of a state. One widely used definition comes from the German sociologist Max Weber: a "st ...

. He viewed it as born out of a sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

concept constructed in the 16th century and religious wars, enhanced by Absolutism and the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

. This concept was founded on abandoning the distinction between authority and power; its product were mushrooming ãartificialã nation-states, which confused ownership with possession. In the late 20th century an alternative solution to obsolete nation-states was a system of ãgreat spaces.ã DãOrs was rather vague about them; some commentators compared them to a set of global orders, some to confederations

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a union of sovereign groups or states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

and some to entities resembling the British commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the Co ...

, though all agree that DãOrs subscribed neither to Pax Americana

''Pax Americana'' (Latin for "American Peace", modeled after ''Pax Romana'' and ''Pax Britannica''; also called the Long Peace) is a term applied to the concept of relative peace in the Western Hemisphere and later in the world after the end o ...

nor to Pax Sovietica concepts. He tried to launch a new science he called "geodieretics," dealing with the organization of territorial order; it differed from geopolitics by discarding the nation state

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may i ...

. Instead, it advanced the theory of subsidiarity, viewed as a regulatory principle operating among social bodies.

DãOrsã recipe for organizing human communities is described as ãcounter-revolutionary trinomy.ã Equality is replaced with legitimity, based on family, natural law, and divine Revelation

In religion and theology, revelation is the revealing or disclosing of some form of truth or knowledge through communication with a deity or other supernatural entity or entities.

Background

Inspiration ã such as that bestowed by God on the ...

as the source of truth. Liberty is replaced by responsibility, founded on personal identity, law, and concept of service. Brotherhood is replaced with fatherhood, this one rooted in authority, wisdom, public good, and order. Contemporary scholars list 32 building blocks of the Orsian order, among them, the exaltation of tradition, ãpolitical verticalism,ã piety, Christianity, religious unity, monarchy, authority, collectivism and violence, and de-emphasizing of reason, democracy, parliamentarism, nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

, capitalism and others.

Some historians name dãOrs a Francoist

Francoist Spain ( es, EspaûÝa franquista), or the Francoist dictatorship (), was the period of Spanish history between 1939 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death in 1975, Spai ...

ideologue. It is underlined that his legitimization of violence and exaltation of the Crusade served the regime perfectly, that he was exponent of the caudillaje theory, that his focus on strong executive and religion supported the mix of nacional-catolicismo, that he advocated ã democracûÙa orgûÀnicaã and that after death of the dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in tim ...

, he judged him favorably. Other scholars claim that dãOrs supported Francoism as long as the regime remained rooted in traditional values and opposed its revolutionary syndicalist

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence i ...

current, that he worked to make Traditionalism the core of Francoist ideology, and that he formed the group which challenged statolatrian penchant of the regime. It is also noted that after 1975, dãOrs confronted the continental order as formed by the Germany-dominated EEC and the world order as dominated by the United States, both devoted to ãconsumismo capitalistaã; he was increasingly bitter about Spain becoming prey of global capitalism.

DãOrs did not produce a synthetic work exposing his political theory, which he viewed as ãteologûÙa polûÙticaã. It was presented mostly in numerous essays, scattered across various press titles and partially re-published in separate collections. Some of them formed part of books devoted to law; those which covered politics are ''De la guerra y la paz'' (1954), ''Forma de gobierno y legitimidad familiar'' (1963), ''Ensayos de TeorûÙa PolûÙtica'' (1979), ''La violencia y el orden'' (1987), ''Parerga histû°rica'' (1997), ''La posesiû°n del espacio'' (1998), and ''Bien comû¤n y Enemigo Pû¤blico'' (2002).

Foralist, canonist and taxonomist

Throughout most of his academic career, dãOrs pursued his interest in specific local legal establishments known as

Throughout most of his academic career, dãOrs pursued his interest in specific local legal establishments known as fueros

(), (), () or () is a Spanish legal term and concept. The word comes from Latin , an open space used as a market, tribunal and meeting place. The same Latin root is the origin of the French terms and , and the Portuguese terms and ; all ...

, related to municipalities, provinces, and regions. In 1946 he took part in Congreso Nacional de Derecho Civil in Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''EncyclopûÎdia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. It lies by the Ebro river and its tributari ...

, where he delivered a lecture endorsing foral rights; it was indirectly aimed against homogenization and centralization, favored by the Francoist regime. He kept presenting his concept of subsidiarity as a form of foralism in articles, published later on. He advanced the concept systematically since the early 1960, when he entered Comisiû°n Compiladora; it was a team which worked on codification of the Navarrese regional legislation, to be titled ''Recopilaciû°n privada de las leyes del Derecho Civil de Navarra''. The labors went on for a few years until their result was published in a series ''Fuero Nuevo de Navarra'' (1968-1971), endorsed by Diputaciû°n Foral. In line with the Orsian idea, the Navarrese establishments were presented as derived from ''autoridad'' and as based on natural law. After the fall of Francoism dãOrs became a member of Consejo de Estudios de Derecho Navarro, entrusted with work on ''Ley OrgûÀnica de Reintegraciû°n y Amejoramiento del Fuero de Navarra''; however, in the early 1980s, the draft proposed by the council was rejected by the local self-government. Afterward, DãOrs focused on smaller territorial entities; he helped to complete ''Ordenanzas del Valle de Salazar'', a set of legal establishments specific for a Pyrenean community of the Salazar Valley.

DãOrs interest in jurisprudence also translated into his focus on

DãOrs interest in jurisprudence also translated into his focus on canon law

Canon law (from grc, ö¤öÝö§üö§, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is th ...

; between 1961 and 1985, he served as professor of canon law at the University of Navarra. Promulgation of the new Code of Canon Law in 1983 directed him more specifically towards some legal regulations within the Catholic Church; he was interested mainly in the legal terminology used, as well as in the critical exegesis of the canons in their Latin versions. A few dedicated articles followed; the work was summarized in the revision of the Spanish translation of the Code of Canon Law, edited by MartûÙn Azpilcueta and published by Institute of the University of Navarra (2001). One more and perhaps the most holistic of dãOrsã academic interests was related to the general classification of sciences, which he developed in the 1960s. Instead of the most widely accepted Diltheian segmentation into natural sciences (''Naturwissenschaften'') and human sciences (''Geisteswissenschaften''), he proposed segmentation into Ciencias Humanas, Ciencias Naturales, and Ciencias Geonû°micas. Law formed part of the first group; the third one listed grouped disciplines related to ''organizaciû°n de la tierra''. The attempt was finalized as a multi-volume massive work titled ''Sistema de las Ciencias'' (1969).

Carlist: access and early years

Though there were very distant and isolated Carlist antecedents in the Ors family, his parents were members of the modernizing bohemian avant-garde. In his juvenile period, dãOrs entered the same liberal path. In the late 1920s, he co-founded ''Juventud'', an art magazine which remained in the press current ãde tono progresista, socializanteã. During his academic years dãOrs did not engage politically; following the outbreak of the war he spent the first year reading books. He crossed via France to the Nationalist zone influenced by his father, but having deserted from the army, he felt heavily attracted to volunteerrequetûˋ

The Requetûˋ () was a Carlist organization, at times with paramilitary units, that operated between the mid-1900s and the early 1970s, though exact dates are not clear.

The Requetûˋ formula differed over the decades, and according to its chan ...

troops. He enlisted to the requetûˋ battalion, Tercio Burgos-Sangû¥esa; service in this unit and since early 1939 in Tercio de Navarra formed him as a Carlist.

When released from the army in 1939 dãOrs did not engage in politics; having landed the academic job in Santiago in the mid-1940s he resumed his links with local Carlist groups, he did not assume any position in organized structures of the movement. As Carlism was increasingly plagued by internal fragmentation dãOrs did not explicitly back any of the factions. Throughout the 1940s and the 1950s, he rather advanced his Traditionalism as a theorist of law and politics, occasionally confronting excessive Falangist

Falangism ( es, falangismo) was the political ideology of two political parties in Spain that were known as the Falange, namely first the Falange EspaûÝola de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista (FE de las JONS) and afterwards the Fal ...

zeal in the academic environment; none of the historiographic studies discussing Carlism of that period mentions his name. His relations with institutional Carlism became closer in the late 1950s. The young entourage of prince Carlos Hugo, at that time just entering the public stage in Spain, turned to the then Santiago academic for support. DãOrs co-drafted the address that the prince was to deliver during the annual Carlist Montejurra

Montejurra in Spanish and Jurramendi in Basque are the names of a mountain in Navarre region (Spain). Each year, it hosts a Carlist celebration in remembrance of the 1873 Battle of Montejurra during the Third Carlist War. In 2004, approximately 1 ...

rally in 1958; it contained bold references to local fueros, to the idea of subsidiarity, and hinted at the concept of a federative Europe. In 1960 he took part in a semi-ideological conference named Semana de Estudios Tradicionalistas, held in Valle de los CaûÙdos

The Valley of the Fallen (Spanish: Valle de los CaûÙdos; ) is a Catholic basilica and a monumental memorial in the municipality of San Lorenzo de El Escorial, erected at Cuelgamuros Valley in the Sierra de Guadarrama, near Madrid. Dictator Fra ...

; dãOrsã lecture was an exposition of his political theory.

At the turn of the decades in public dãOrs was not identified as a Carlist zealot; politicians from the Alfonsist camp considered him their potential ally, especially given his membership in the pro-Juanista Opus Dei. When in 1960 Franco

Franco may refer to:

Name

* Franco (name)

* Francisco Franco (1892ã1975), Spanish general and dictator of Spain from 1939 to 1975

* Franco Luambo (1938ã1989), Congolese musician, the "Grand MaûÛtre"

Prefix

* Franco, a prefix used when ref ...

decided that further education of Don Juan Carlos, who had turned 18, should be coordinated by an academic board, the entourage of Don Juan

Don Juan (), also known as Don Giovanni ( Italian), is a legendary, fictional Spanish libertine who devotes his life to seducing women. Famous versions of the story include a 17th-century play, ''El burlador de Sevilla y convidado de piedra'' ...

suggested that dãOrs becomes its member. The office of Franco dropped him from the candidates' list. Still, he was reinstated on the insistence of the Alfonsinos. The controversy became pointless as sounded on his membership, DãOrs declined. He pointed out that the only legitimate heir was Don Javier; when pressed, he responded with ã lealtad o the Carlist dynastyobliga.ã

Carlist: climax

The early 1960s mark the beginning of dãOrsã explicit engagement in Carlist labors. In 1962 he co-worked on a document, which legally backed citizenship claims of the Borbû°n-Parmas; it was presented to Franco during the prince's visit to

The early 1960s mark the beginning of dãOrsã explicit engagement in Carlist labors. In 1962 he co-worked on a document, which legally backed citizenship claims of the Borbû°n-Parmas; it was presented to Franco during the prince's visit to El Pardo

El Pardo is a ward (''barrio'') of Madrid belonging to the district of Fuencarral-El Pardo. As of 2008 its population was of 3,656.

History

The ward was first mentioned in 1405 and in 1950 was an autonomous municipality of the Community of Madri ...

the same year. DãOrs accompanied Don Carlos Hugo at the occasion,. However, he was not admitted to the interview. According to his later account until that point, he had genuinely believed that Franco-endorsed coronation of a Carlist pretender was possible; the interview convinced him that it was an illusion, yet he went on to support the Borbû°n-Parmas, because of his loyalty to the dynasty. There is confusing evidence, though; the same year he developed doubts about Traditionalist credentials of Don Carlos Hugo.

In 1964 dãOrs prepared a set of documents to be agreed during the grand meeting at Puchheim and then attended the meeting, staged the following year. As a legal expert, he elaborated on the legal case of Don Sixto, threatened with expulsion from Spain and later admitted to the Foreign Legion. In 1965 for the only time he spoke during the Montejurra rally; discussing the legitimacy of the Borbû°n-Parmas, he made a great impact. In 1965 d'Ors was nominated to Junta del Gobierno, in 1966 to the newly established Consejo Asesor de la Jefatura Delegada and in the press he appeared as a member of Junta Nacional. In 1968 he entered another body, Consejo Real; among some 80 candidates, he was among 4 the most-voted. He kept serving as chief legal adviser to Don Javier, e.g., drafting his declaration on the planned Ley OrgûÀnica referendum.

Since the early 1960s, Carlism was increasingly divided between an emergent progressist faction centred around Don Carlos Hugo and the Traditionalist core. In the mid-1960s, the progressists were already in control of key institutions of the movement. There is no information on dãOrsã taking part in the internal power struggle. Though ideologically he was the key representative of Traditionalist orthodoxy and spoke out against subversive, revolutionary currents, marked by the deification of democracy and human rights, until 1968 he was among authors most frequently published in the carlo-huguista review, ''

Since the early 1960s, Carlism was increasingly divided between an emergent progressist faction centred around Don Carlos Hugo and the Traditionalist core. In the mid-1960s, the progressists were already in control of key institutions of the movement. There is no information on dãOrsã taking part in the internal power struggle. Though ideologically he was the key representative of Traditionalist orthodoxy and spoke out against subversive, revolutionary currents, marked by the deification of democracy and human rights, until 1968 he was among authors most frequently published in the carlo-huguista review, ''Montejurra

Montejurra in Spanish and Jurramendi in Basque are the names of a mountain in Navarre region (Spain). Each year, it hosts a Carlist celebration in remembrance of the 1873 Battle of Montejurra during the Third Carlist War. In 2004, approximately 1 ...

''. However, in the late 1960s, he was increasingly alienated by new ideas introduced by the prince and his entourage, especially that there were already few Traditionalists left in the command layer of the organization. He declared to Don Carlos Hugo ãVuestra Alteza es republicanoã, and started to distance himself from the party structures. In the early 1970s, following grand carlo-huguista rallies in Arbonne

Arbonne (; eu, Arbona) is a commune in the Pyrûˋnûˋes-Atlantiques department in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region of southwestern France.

The inhabitants of the commune are known as ''Arbonars''Brigitte Jobbûˋ-Duval, ''Dictionary of place names - ...

, he withdrew from Consejo del Rey and terminated his links with the newly emergent Partido Carlista.

Carlist: post-Franco years

Since the early 1970s, dãOrs stayed clear of official Carlist structures, controlled by the carlo-huguistas; he was also greatly disappointed by the position taken by the claimant, Don Javier, who apparently condoned proto-socialist endeavors of his son, Don Carlos Hugo. However, he did not engage in open confrontation. In 1976 and encouraged by his daughter, he attended the annual Montejurra rally; according to his own account, he was unaware that the Traditionalists chose the event to confront Don Carlos Hugo and his followers. When the gathering turned into amelee

A melee ( or , French: mûˆlûˋe ) or pell-mell is disorganized hand-to-hand combat in battles fought at abnormally close range with little central control once it starts. In military aviation, a melee has been defined as " air battle in which ...

he withdrew; however, some press titles claimed later that dãOrs instigated Traditionalist militants towards violence. Afterwards he visited some of them, like Arturo MûÀrquez de Prado, during their brief incarceration period.

Close to nothing is known about dãOrsã Carlist engagement at the turn of the decades. In the early 1980s, he maintained private relations with Traditionalist activists like MûÀrquez de Prado, Javier Nagore YûÀrnoz or Miguel Garisoain and pundits like Antonio Segura, Rafael Gambra or Frederick Wilhelmsen; at times he took part in semi-scientific conferences or public rallies, e.g., the one commemorating the fallen requetûˋ at Isusquiza. As numerous Carlist grouplets tried to overcome the period of fragmentation, dãOrs remained highly supportive; during a unification rally of 1986, which gave rise to Comuniû°n Tradicionalista Carlista, he was present and got elected to its executive, Consejo Nacional. However, he was more of a patriarch than an active politician, and did not take part in day-to-day party activities. The exception were elections to the EU parliament, staged in 1994. He agreed to stand as the last candidate on the CTC list, his presence tailored to lend his personal prestige to other Carlist candidates running. The bid ended in total failure.

octogenarian

Ageing ( BE) or aging ( AE) is the process of becoming older. The term refers mainly to humans, many other animals, and fungi, whereas for example, bacteria, perennial plants and some simple animals are potentially biologically immortal. In ...

dãOrs considered Carlism a politically lost cause; according to his 2000 letter, the role of CTC was ãto save principles of the Tradition against democratic correctness, which rules todayã. It is not clear what was his opinion on another breakup, namely when followers of Don Sixto set up their own organization and left CTC. According to some sources, until death dãOrs remained in the CTC executive. In 2002 dãOrs became target of heavy criticism on part of the Sixtinos; it was following his article, which presented the Carlist theme "Dios Patria Rey" as somewhat obsolete. DãOrs suggested that religious question became largely a private issue, that patriotism was mostly down to defense of foral order, and that a king became a symbol of monarchy rather than a specific person or a dynasty. The Sixtino leader, Rafael Gambra, vehemently rejected the theory and charged dãOrs with the intention of reducing Carlism to ãone more christian-democratic groupingã.

Reception and legacy

DãOrs established his position among the best Spanish experts in Roman law following the 1953 publication of ''EpigrafûÙa jurûÙdica''. However, he became known nationally upon receiving

DãOrs established his position among the best Spanish experts in Roman law following the 1953 publication of ''EpigrafûÙa jurûÙdica''. However, he became known nationally upon receiving Premio Nacional de Literatura A National Prize for Literature ( es, Premio Nacional de Literatura) is a kind of award offered by various countries.

Examples include:

* National Prize for Literature (Argentina)

* National Literary Awards, Burma

* National Prize for Literature ( ...

in 1954, the award which acknowledged his ''De la Guerra y de la Paz'' essays. In the 1960s, he was already the top national Roman law scholar. He was awarded Premio Nacional de Investigaciû°n (1973), Cruz de Alfonso X el Sabio (1974) and Gran Cruz de San Raimundo de PeûÝafort (1997), and honorary degrees by the universities of Toulouse

Toulouse ( , ; oc, Tolosa ) is the prefecture of the French department of Haute-Garonne and of the larger region of Occitania. The city is on the banks of the River Garonne, from the Mediterranean Sea, from the Atlantic Ocean and from Pa ...

(1972), Coimbra (1983) and La Sapienza

The Sapienza University of Rome ( it, Sapienza ã Universitû di Roma), also called simply Sapienza or the University of Rome, and formally the Universitû degli Studi di Roma "La Sapienza", is a public research university located in Rome, Ita ...

(1996). D'Ors also was awarded honors by the University of Navarre, Eusko Ikaskuntza

The ''Basque Studies Society'' ( eu , Eusko Ikaskuntza; '' 'EI-SEV' '') is a scientific-cultural institution created in 1918 by the Provincial Councils of ûlava, Vizcaya, Guipû¤zcoa and Navarra a stable and lasting resource to develop the Bas ...

and Navarrese self-government. However, since the 1980s, he complained about having been increasingly isolated as a result of ãrevanchismo polûÙtico.ã

Currently dãOrs is counted among European scholars responsible for renaissance of studies in Roman law, most influential Roman law scholars of the 20th century, best Spanish jurists of the period, and best world romanistas of the last 150 years. In terms of theory of politics, he is counted among best European scholars of the 20th century and among greatest Traditionalist thinkers. However, it is noted that dãOrs was hardly known beyond Spain, the result of his decision to write in castellano

Castellano may refer to:

* Castilian (disambiguation) (Spanish: ''castellano'')

** Castile (historical region)

Castile or Castille (; ) is a territory of imprecise limits located in Spain. The invention of the concept of Castile relies on the ...

only. His memory is cherished in the University of Navarra

, image = UNAV.svg

, latin_name = Universitas Studiorum Navarrensis

, established = 17 October 1952

, type = Private, Roman Catholic

, chancellor = Fernando OcûÀriz BraûÝa

, president = MarûÙa Iraburu Eliz ...

, which consider him a central figure in the development of the university. In 2013 a bust of d'Ors was placed at the entrance to the university library main building; in 2020 an interdisciplinary chair at the University of Navarra Institute of Culture and Society was named after dãOrs. Apart from Roman law, he is generally noted as expert in linguistics

Linguistics is the science, scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure ...

, philology

Philology () is the study of language in oral and written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics (with especially strong ties to etymology). Philology is also defined as th ...

, philosophy, papyrology, epigraphy, ancient history, civil law, canon law, foral law, legal theory, Catholic theology, social philosophy and theory of education. Numerous present-day academics are listed as his disciples.

Attempts to classify dãOrsã thought in terms of any specific school or current are fairly rare. Some consider him the member of an intellectual formation named ãgeneration 48ã; others ponder upon the labels of ãescolûÀsticoã or ãrealistaã; in the theory of law clearly supporter of natural law school, in the theory of politics he is also decisively categorized as a Traditionalist. All scholars underline his intellectual kinship to

Attempts to classify dãOrsã thought in terms of any specific school or current are fairly rare. Some consider him the member of an intellectual formation named ãgeneration 48ã; others ponder upon the labels of ãescolûÀsticoã or ãrealistaã; in the theory of law clearly supporter of natural law school, in the theory of politics he is also decisively categorized as a Traditionalist. All scholars underline his intellectual kinship to Carl Schmitt

Carl Schmitt (; 11 July 1888 ã 7 April 1985) was a German jurist, political theorist, and prominent member of the Nazi Party. Schmitt wrote extensively about the effective wielding of political power. A conservative theorist, he is noted as ...

, but some underline differences, some relate him to the Schmittian decisionism, some categorize dãOrs concepts as ãextremeã and discuss them against the background of pro-Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

leaning of Schmitt. Some present dãOrs as a Traditionalist contributor to the Francoist ideology. In the Traditionalist ambience dãOrs is hailed as one of the all-time greats; the progressist ones offer challenge, criticism and highly ambiguous acknowledgement. Some note that in the theory of law many scholars follow him up to the point when their own clichûˋs prevent further alignment. Among tens of scientific articles, some written as far away as in the United States, Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

, Mexico, Hungary or Poland, dãOrs earnt at least 3 doctoral dissertations, one written already during his lifetime. Among 3 books published one is an all-round biography, published by dãOrsã son-in-law

Son-in-Law (22 April 1911 ã 15 May 1941) was a British Thoroughbred racehorse and an influential sire, especially for sport horses.

The National Horseracing Museum says Son-in-Law is "probably the best and most distinguished stayer this co ...

.Gabriel Pûˋrez Gû°mez is husband to Paz dãOrs Lois

See also

* Carlism *Traditionalism (Spain)

Traditionalism ( es, tradicionalismo) is a Spanish political doctrine formulated in the early 19th century. It understands politics as implementing the social kingship of Jesus Christ, with Catholicism as the state religion and Catholic religious ...

* Roman law

Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the '' Corpus Juris Civilis'' (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor Ju ...

* Eugenio d'Ors

Eugenio d'Ors Rovira (Barcelona, 28 September 1882 ã Vilanova i la Geltrû¤, 25 September 1954) was a Spanish writer, essayist, journalist, philosopher and art critic. He wrote in both Catalan and Spanish, sometimes under the pseudonym of ''Xû´n ...

Footnotes

Further reading

*Rafael Domingo Osle

Rafael Domingo Oslûˋ (Logrono, La Rioja, 1963) is a Spanish professor of law and legal historian.

Education

Rafael Domingo received his university law degree and a doctorate in law from the University of Navarra. He conducted legal research as a ...

, ''ûlvaro dãOrs. Una aproximaciû°n a su obra'', Cizur Menor 2005,

* AgustûÙn GûÀndara Moure, ''El Concepto de derecho en ûlvaro d'Ors'' hD thesis Universidade de Santiago de Compostela Santiago 1993

* Montserrat Herrero (ed.), ''Carl Schmitt und ûlvaro dãOrs Briefwechsel'', Berlin 2004,

* Juan Ramû°n Medina Cepero, ''La trinomûÙa anti-revolucionaria de ûlvaro d'Ors'' hD thesis Universitat Ramon Llull Barcelona 2013

* Manuel J. PelûÀez, ''ûlvaro d'Ors Pûˋrez-Peix'', n:''Revista de Dret Histûýric Catalû '' 4 (2005), pp. 195ã219

* Gabriel Pûˋrez Gû°mez, ''ûlvaro d'Ors: SinfonûÙa de una vida'', Madrid 2020,

* Alejandra Vanney, ''Libertad y Estado. El pensamiento filosû°fico-polûÙtico de ûlvaro dãOrs'', Pamplona 2009,

* Rafael Domingo Osle, Javier MartûÙnez-Torrû°n (eds), ''Great Christian Jurists in Spanish History'', Cambridge, 2017,

External links

d'Ors at University of Navarre website

d'Ors at University Carlos III website

''Por Dios y por EspaûÝa''; contemporary Carlist propaganda

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ors Perez Preix, Alvaro d' Canon law jurists Carl Schmitt scholars Carlists Francoist Spain Male essayists Roman Catholic writers Spanish anti-communists 20th-century Spanish historians Spanish educational theorists Spanish essayists Spanish male writers Spanish monarchists Spanish military personnel of the Spanish Civil War (National faction) Spanish philosophers Spanish politicians Spanish Roman Catholics Academic staff of the University of Coimbra Academic staff of the University of Granada Academic staff of the University of Navarra Academic staff of the University of Santiago de Compostela 20th-century Spanish lawyers 1915 births 2004 deaths