|

Thioketal

In organosulfur chemistry, a thioketal is the sulfur analogue of a ketal (), with one of the oxygen replaced by sulfur (as implied by the '' thio-'' prefix), giving the structure . A dithioketal has ''both'' oxygens replaced by sulfur (). Thioketals can be obtained by reacting ketones () or aldehydes () with thiols (). An oxidative cleavage mechanism has been proposed for dithioketals, which involves thioether oxidation, the formation of thionoiums, and hydrolysis, resulting in the formation of aldehyde and ketone products. Thioketal moieties are found to be responsive to reactive oxygen species (ROS). In the presence of ROS, thioketals can be selectively cleaved. ROS successfully cleave heterobifunctional thioketal linkers, which have been found to have therapeutic potential, as they can produce ROS-responsive agents with two different functionalities. Ketones can be reduced at neutral pH via conversion to thioketals; the thioketal prepared from the ketone can be easily red ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Thiols

In organic chemistry, a thiol (; ), or thiol derivative, is any organosulfur compound of the form , where R represents an alkyl or other organic substituent. The functional group itself is referred to as either a thiol group or a sulfhydryl group, or a sulfanyl group. Thiols are the sulfur analogue of alcohols (that is, sulfur takes the place of oxygen in the hydroxyl () group of an alcohol), and the word is a blend of "''thio-''" with "alcohol". Many thiols have strong odors resembling that of garlic, cabbage or rotten eggs. Thiols are used as odorants to assist in the detection of natural gas (which in pure form is odorless), and the smell of natural gas is due to the smell of the thiol used as the odorant. Nomenclature Thiols are sometimes referred to as mercaptans () or mercapto compounds, a term introduced in 1832 by William Christopher Zeise and is derived from the Latin ('capturing mercury')''Oxford American Dictionaries'' (Mac OS X Leopard). because the thiolate group ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

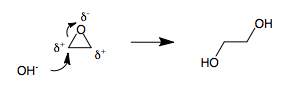

Thioacetal

In organosulfur chemistry, thioacetals are the sulfur (''thio-'') analog (chemistry), analogues of acetals (). There are two classes: the less-common monothioacetals, with the formula , and the dithioacetals, with the formula (symmetric dithioacetals) or (asymmetric dithioacetals). The symmetric dithioacetals are relatively common. They are prepared by Condensation reaction, condensation of thiols () or dithiols (two groups) with aldehydes (). These reactions proceed via the Reaction intermediate, intermediacy of hemithioacetals (): :Thiol addition to give hemithioacetal: :: :Thiol addition with loss of water to give dithioacetal: :: Such reactions typically employ either a Lewis acid or Brønsted acid as catalyst. Dithioacetals generated from aldehydes and either 1,2-ethanedithiol or 1,3-propanedithiol are especially common among this class of molecules for use in organic synthesis. : The carbonyl carbon of an aldehyde is electrophilic and therefore susceptible to attac ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Bond Cleavage

In chemistry, bond cleavage, or bond fission, is the splitting of chemical bonds. This can be generally referred to as dissociation when a molecule is cleaved into two or more fragments. In general, there are two classifications for bond cleavage: ''homo''lytic and ''hetero''lytic, depending on the nature of the process. The triplet and singlet excitation energies of a sigma bond can be used to determine if a bond will follow the homolytic or heterolytic pathway. A metal−metal sigma bond is an exception because the bond's excitation energy is extremely high, thus cannot be used for observation purposes. In some cases, bond cleavage requires catalysts. Due to the high bond-dissociation energy of C−H bonds, around , a large amount of energy is required to cleave the hydrogen atom from the carbon and bond a different atom to the carbon. Homolytic cleavage In homolytic cleavage, or homolysis, the two electrons in a cleaved covalent bond are divided equally betwee ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Mozingo Reduction

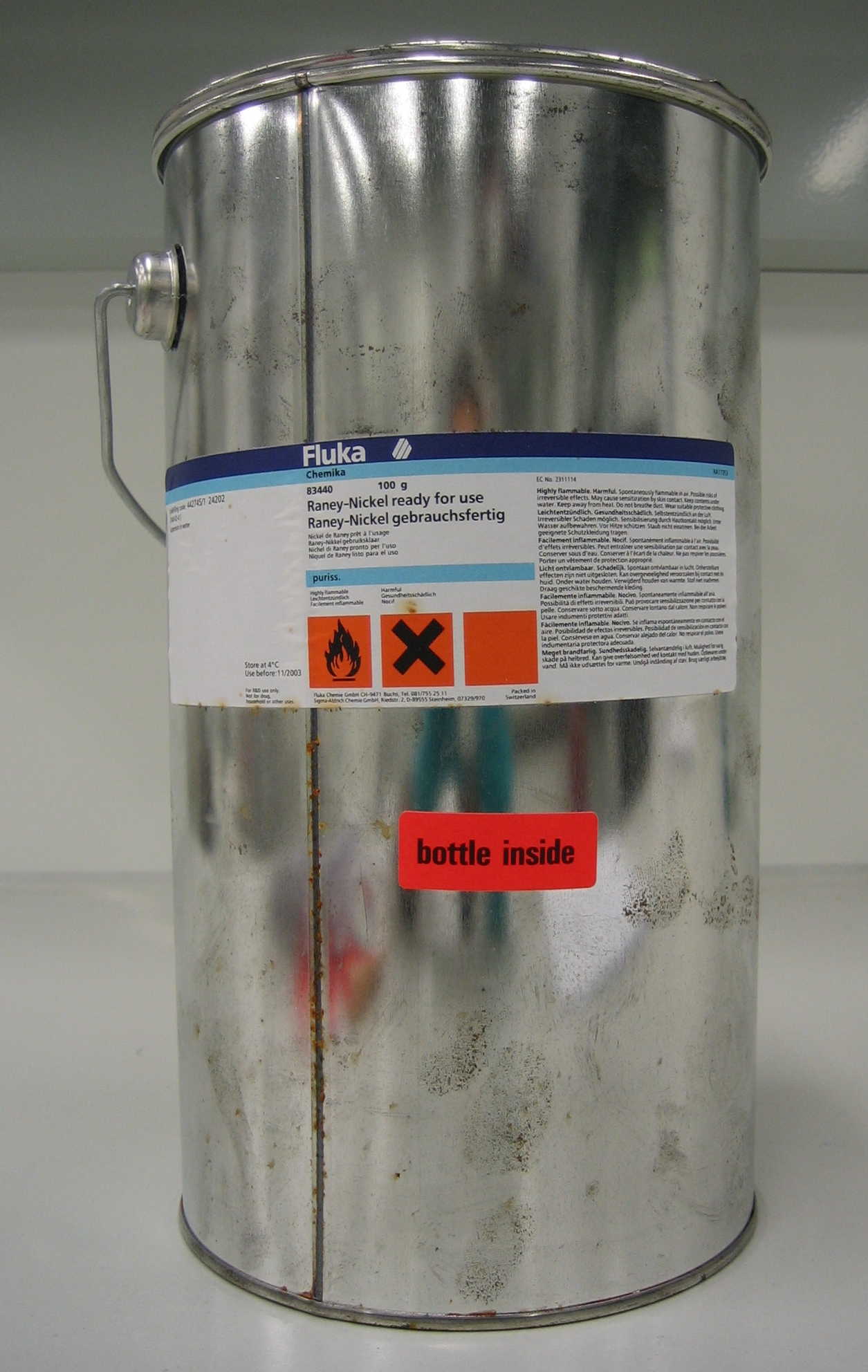

The Mozingo reduction, also known as Mozingo reaction or thioketal reduction, is a chemical reaction capable of fully reducing a ketone or aldehyde to the corresponding alkane via a dithioacetal. The reaction scheme is as follows: The ketone or aldehyde is activated by conversion to cyclic dithioacetal by reaction with a dithiol (nucleophilic substitution) in presence of a H+ donating acid. The cyclic dithioacetal structure is then hydrogenolyzed using Raney nickel. Raney nickel is converted irreversibly to nickel sulfide. This method is milder than either the Clemmensen or Wolff-Kishner reductions, which employ strongly acidic or basic conditions, respectively, that might interfere with other functional groups. History The reaction is named after Ralph Mozingo, who reported the cleavage of thioether In organic chemistry, a sulfide (British English sulphide) or thioether is an organosulfur functional group with the connectivity as shown on right. Like many other sulfur-c ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Raney Nickel

Raney nickel , also called spongy nickel, is a fine-grained solid composed mostly of nickel derived from a nickel–aluminium alloy. Several grades are known, of which most are gray solids. Some are pyrophoric, but most are used as air-stable slurries. Raney nickel is used as a reagent and as a catalyst in organic chemistry. It was developed in 1926 by American engineer Murray Raney for the hydrogenation of vegetable oils. Raney Nickel is a registered trademark of W. R. Grace and Company. Other major producers are Evonik and Johnson Matthey. Preparation Alloy preparation The Ni–Al alloy is prepared by dissolving nickel in molten aluminium followed by cooling ("quenching"). Depending on the Ni:Al ratio, quenching produces a number of different phases. During the quenching procedure, small amounts of a third metal, such as zinc or chromium, are added to enhance the activity of the resulting catalyst. This third metal is called a "Promoter (catalysis), promoter". The promoter ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Reactive Oxygen Species

In chemistry and biology, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are highly Reactivity (chemistry), reactive chemicals formed from diatomic oxygen (), water, and hydrogen peroxide. Some prominent ROS are hydroperoxide (H2O2), superoxide (O2−), hydroxyl radical (OH.), and singlet oxygen(1O2). ROS are pervasive because they are readily produced from O2, which is abundant. ROS are important in many ways, both beneficial and otherwise. ROS function as signals, that turn on and off biological functions. They are intermediates in the redox behavior of O2, which is central to fuel cells. ROS are central to the photodegradation of organic pollutants in the atmosphere. Most often however, ROS are discussed in a biological context, ranging from their effects on aging and their role in causing dangerous genetic mutations. Inventory of ROS ROS are not uniformly defined. All sources include superoxide, singlet oxygen, and hydroxyl radical. Hydrogen peroxide is not nearly as reactive as these s ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Moiety (chemistry)

In organic chemistry, a moiety ( ) is a part of a molecule that is given a name because it is identified as a part of other molecules as well. Typically, the term is used to describe the larger and characteristic parts of organic molecules, and it should not be used to describe or name smaller functional groups of atoms that chemically react in similar ways in most molecules that contain them. Occasionally, a moiety may contain smaller moieties and functional groups. A moiety that acts as a branch extending from the backbone of a hydrocarbon molecule is called a substituent or side chain, which typically can be removed from the molecule and substituted with others. The term is also used in pharmacology, where an active moiety is the part of a molecule responsible for the physiological or pharmacological action of a drug. Active moiety In pharmacology, an active moiety is the part of a molecule or ion—excluding appended inactive portions—that is responsible for the ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Hydrolysis

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used broadly for substitution reaction, substitution, elimination reaction, elimination, and solvation reactions in which water is the nucleophile. Biological hydrolysis is the cleavage of Biomolecule, biomolecules where a water molecule is consumed to effect the separation of a larger molecule into component parts. When a carbohydrate is broken into its component sugar molecules by hydrolysis (e.g., sucrose being broken down into glucose and fructose), this is recognized as saccharification. Hydrolysis reactions can be the reverse of a condensation reaction in which two molecules join into a larger one and eject a water molecule. Thus hydrolysis adds water to break down, whereas condensation builds up by removing water. Types Usually hydrolysis is a chemical process in which a molecule of water is added to a substance. Sometimes this addition causes both the su ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Organosulfur Chemistry

Organosulfur chemistry is the study of the properties and synthesis of organosulfur compounds, which are organic compounds that contain sulfur. They are often associated with foul odors, but many of the sweetest compounds known are organosulfur derivatives, e.g., saccharin. Nature is abound with organosulfur compounds—sulfur is vital for life. Of the 20 common amino acids, two (cysteine and methionine) are organosulfur compounds, and the antibiotics penicillin and sulfa drugs both contain sulfur. While sulfur-containing antibiotics save many lives, sulfur mustard is a deadly chemical warfare agent. Fossil fuels, coal, petroleum, and natural gas, which are derived from ancient organisms, necessarily contain organosulfur compounds, the removal of which is a major focus of oil refineries. Sulfur shares the chalcogen group with oxygen, selenium, and tellurium, and it is expected that organosulfur compounds have similarities with carbon–oxygen, carbon–selenium, and carbon–tell ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Aldehydes

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () (lat. ''al''cohol ''dehyd''rogenatum, dehydrogenated alcohol) is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred to as an aldehyde but can also be classified as a formyl group. Aldehydes are a common motif in many chemicals important in technology and biology. Structure and bonding Aldehyde molecules have a central carbon atom that is connected by a double bond to oxygen, a single bond to hydrogen and another single bond to a third substituent, which is carbon or, in the case of formaldehyde, hydrogen. The central carbon is often described as being sp2- hybridized. The aldehyde group is somewhat polar. The bond length is about 120–122 picometers. Physical properties and characterization Aldehydes have properties that are diverse and that depend on the remainder of the molecule. Smaller aldehydes such as formaldehyde and acetaldehyde are soluble ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Ketones

In organic chemistry, a ketone is an organic compound with the structure , where R and R' can be a variety of carbon-containing substituents. Ketones contain a carbonyl group (a carbon-oxygen double bond C=O). The simplest ketone is acetone (where R and R' are methyl), with the formula . Many ketones are of great importance in biology and industry. Examples include many sugars (ketoses), many steroids, ''e.g.'', testosterone, and the solvent acetone. Nomenclature and etymology The word ''ketone'' is derived from ''Aketon'', an old German word for ''acetone''. According to the rules of IUPAC nomenclature, ketone names are derived by changing the suffix ''-ane'' of the parent alkane to ''-anone''. Typically, the position of the carbonyl group is denoted by a number, but traditional nonsystematic names are still generally used for the most important ketones, for example acetone and benzophenone. These nonsystematic names are considered retained IUPAC names, although some introd ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |