|

PtaRNA1

PtaRNA1 (plasmid transferred antisense RNA) is a family of non-coding RNAs. Homologs of PtaRNA1 can be found in the bacterial families, Betaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria. In all cases the PtaRNA1 is located anti-sense to a short protein-coding gene. In ''Xanthomonas campestris'' pv. ''vesicatoria'', this gene is annotated aXCV2162and is included in the plasmid toxin family of proteins. Distribution and function Both PtaRNA1 and the adjacent coding gene, which only appear only in combination, have an erratic phylogenetic distribution. The distribution of ''ptaRNA1'' is not congruent with the phylogeny of the host species as it is with other sRNA families such as Yfr1 and Yfr2. This indicates that ptaRNA1 has undergone frequent horizontal gene transfer. These observations are in accordance with those made of Type I toxin-antitoxin systems. In type I toxin-antitoxin systems, the gene expression of a toxic protein is regulated by a small non-coding RNA. Type I toxin-an ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

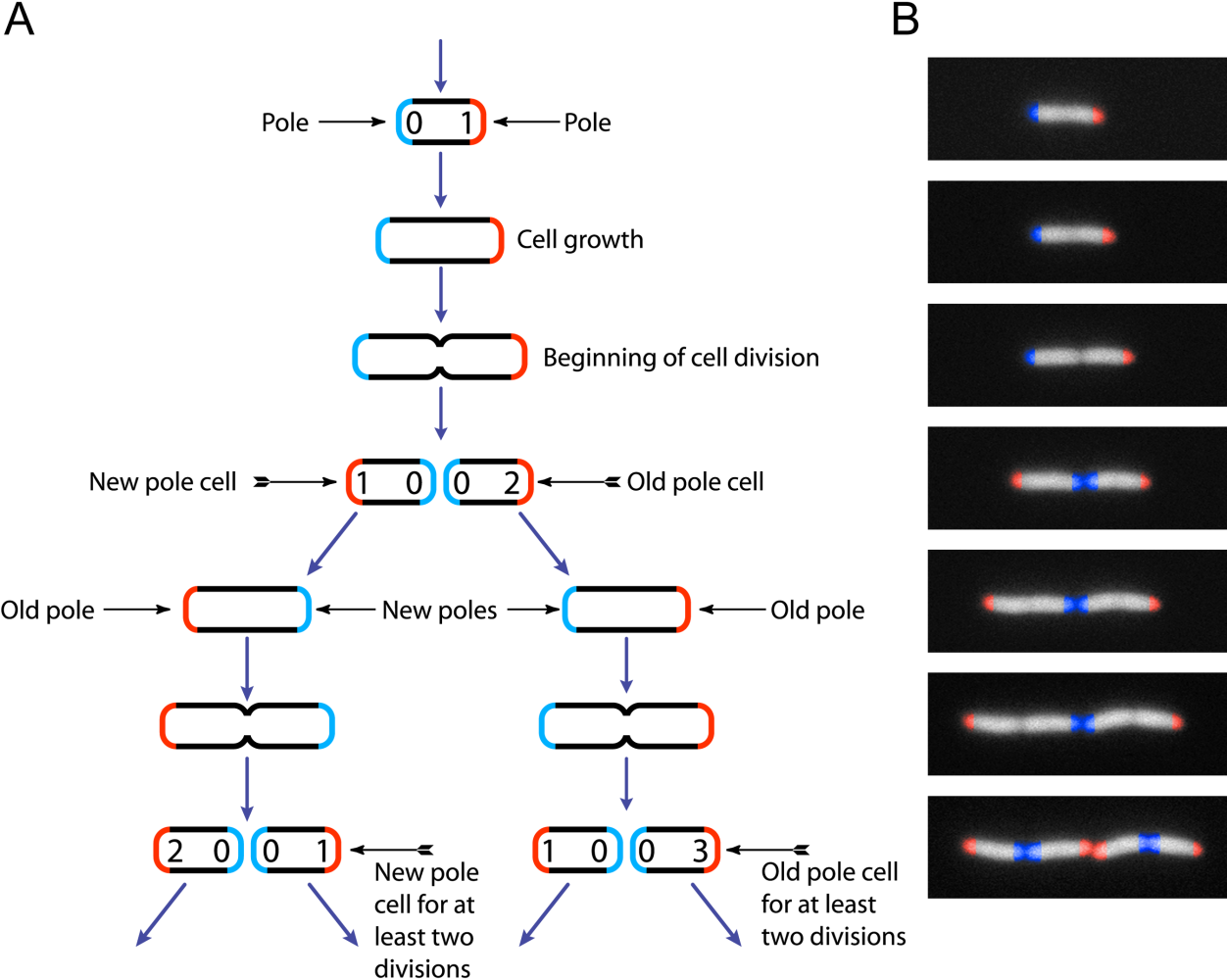

Hok/sok System

The hok/sok system is a postsegregational killing mechanism employed by the R1 plasmid in ''Escherichia coli''. It was the first type I toxin-antitoxin pair to be identified through characterisation of a plasmid-stabilising locus. It is a type I system because the toxin is neutralised by a complementary RNA, rather than a partnered protein (type II toxin-antitoxin). Genes involved The hok/sok system involves three genes: * ''hok'', host killing - a long lived (half-life 20 minutes) toxin * ''sok'', suppression of killing - a short lived (half-life 30 seconds) RNA antitoxin * ''mok'', modulation of killing - required for ''hok'' translation Killing mechanism When ''E. coli'' undergoes cell division, the two daughter cells inherit the long-lived hok toxin from the parent cell. Due to the short half-life of the sok antitoxin, daughter cells inherit only small amounts and it quickly degrades. If a daughter cell has inherited the R1 plasmid, it has inherited the ''sok'' gene and a ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Gammaproteobacteria

Gammaproteobacteria is a class of bacteria in the phylum Pseudomonadota (synonym Proteobacteria). It contains about 250 genera, which makes it the most genera-rich taxon of the Prokaryotes. Several medically, ecologically, and scientifically important groups of bacteria belong to this class. It is composed by all Gram-negative microbes and is the most phylogenetically and physiologically diverse class of Proteobacteria. These microorganisms can live in several terrestrial and marine environments, in which they play various important roles, including ''extreme environments'' such as hydrothermal vents. They generally have different shapes - rods, curved rods, cocci, spirilla, and filaments and include free living bacteria, biofilm formers, commensals and symbionts, some also have the distinctive trait of being bioluminescent. Metabolisms found in the different genera are very different; there are both aerobic and anaerobic (obligate or facultative) species, chemolithoautotrophic ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Gene Expression

Gene expression is the process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, protein or non-coding RNA, and ultimately affect a phenotype, as the final effect. These products are often proteins, but in non-protein-coding genes such as transfer RNA (tRNA) and small nuclear RNA (snRNA), the product is a functional non-coding RNA. Gene expression is summarized in the central dogma of molecular biology first formulated by Francis Crick in 1958, further developed in his 1970 article, and expanded by the subsequent discoveries of reverse transcription and RNA replication. The process of gene expression is used by all known life—eukaryotes (including multicellular organisms), prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea), and utilized by viruses—to generate the macromolecular machinery for life. In genetics, gene expression is the most fundamental level at which the genotype gives rise to the phenotype, '' ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Toxin-antitoxin System

A toxin-antitoxin system is a set of two or more closely linked genes that together encode both a "toxin" protein and a corresponding "antitoxin". Toxin-antitoxin systems are widely distributed in prokaryotes, and organisms often have them in multiple copies. When these systems are contained on plasmids – transferable genetic elements – they ensure that only the daughter cells that inherit the plasmid survive after cell division. If the plasmid is absent in a daughter cell, the unstable antitoxin is degraded and the stable toxic protein kills the new cell; this is known as 'post-segregational killing' (PSK). Toxin-antitoxin systems are typically classified according to how the antitoxin neutralises the toxin. In a type I toxin-antitoxin system, the translation of messenger RNA (mRNA) that encodes the toxin is inhibited by the binding of a small non-coding RNA antitoxin that binds the toxin mRNA. The toxic protein in a type II system is inhibited post-translationally ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Bootstrapping (statistics)

Bootstrapping is any test or metric that uses random sampling with replacement (e.g. mimicking the sampling process), and falls under the broader class of resampling methods. Bootstrapping assigns measures of accuracy (bias, variance, confidence intervals, prediction error, etc.) to sample estimates.software This technique allows estimation of the sampling distribution of almost any statistic using random sampling methods. Bootstrapping estimates the properties of an (such as its ) by measuring those properties when sampling from an approximating distribution. One standard choice for an a ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Phylogenetic Tree

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological species or other entities based upon similarities and differences in their physical or genetic characteristics. All life on Earth is part of a single phylogenetic tree, indicating common ancestry. In a ''rooted'' phylogenetic tree, each node with descendants represents the inferred most recent common ancestor of those descendants, and the edge lengths in some trees may be interpreted as time estimates. Each node is called a taxonomic unit. Internal nodes are generally called hypothetical taxonomic units, as they cannot be directly observed. Trees are useful in fields of biology such as bioinformatics, systematics, and phylogenetics. ''Unrooted'' trees illustrate only the relatedness of the leaf nodes and do not require the ancestral root to b ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

TraJ 5' UTR

The traJ 5' UTR is a cis acting RNA element which is involved in regulating plasmid transfer in bacteria. In conjugating bacteria the FinOP system regulates the transfer of F-like plasmids. The FinP gene encodes an antisense RNA product that is complementary to part of the 5' UTR of the traJ mRNA. The traJ gene encodes a protein required for transcription from the major transfer promoter, pY. The FinO protein is essential for effective repression, acting by binding to FinP and protecting it from RNase Ribonuclease (commonly abbreviated RNase) is a type of nuclease that catalyzes the degradation of RNA into smaller components. Ribonucleases can be divided into endoribonucleases and exoribonucleases, and comprise several sub-classes within the ... E degradation. References External links * * Cis-regulatory RNA elements {{molecular-cell-biology-stub ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Cis-acting

''Cis''-regulatory elements (CREs) or ''Cis''-regulatory modules (CRMs) are regions of non-coding DNA which regulate the transcription of neighboring genes. CREs are vital components of genetic regulatory networks, which in turn control morphogenesis, the development of anatomy, and other aspects of embryonic development, studied in evolutionary developmental biology. CREs are found in the vicinity of the genes that they regulate. CREs typically regulate gene transcription by binding to transcription factors. A single transcription factor may bind to many CREs, and hence control the expression of many genes (pleiotropy). The Latin prefix ''cis'' means "on this side", i.e. on the same molecule of DNA as the gene(s) to be transcribed. CRMs are stretches of DNA, usually 100–1000 DNA base pairs in length, where a number of transcription factors can bind and regulate expression of nearby genes and regulate their transcription rates. They are labeled as ''cis'' because they are ty ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

FinP

FinP encodes an antisense non-coding RNA gene that is complementary to part of the TraJ 5' UTR. The FinOP system regulates the transfer of F-like plasmids. The traJ gene encodes a protein required for transcription Transcription refers to the process of converting sounds (voice, music etc.) into letters or musical notes, or producing a copy of something in another medium, including: Genetics * Transcription (biology), the copying of DNA into RNA, the fir ... from the major transfer promoter, pY. The FinO protein is essential for effective repression, acting by binding to FinP and protecting it from RNase E degradation. References External links * * Antisense RNA {{molecular-cell-biology-stub ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Escherichia Coli

''Escherichia coli'' (),Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. also known as ''E. coli'' (), is a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus ''Escherichia'' that is commonly found in the lower intestine of warm-blooded organisms. Most ''E. coli'' strains are harmless, but some serotypes ( EPEC, ETEC etc.) can cause serious food poisoning in their hosts, and are occasionally responsible for food contamination incidents that prompt product recalls. Most strains do not cause disease in humans and are part of the normal microbiota of the gut; such strains are harmless or even beneficial to humans (although these strains tend to be less studied than the pathogenic ones). For example, some strains of ''E. coli'' benefit their hosts by producing vitamin K2 or by preventing the colonization of the intestine by pathogenic bacteria. These mutually beneficial relationships between ''E. col ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Secondary Structure

Protein secondary structure is the three dimensional conformational isomerism, form of ''local segments'' of proteins. The two most common Protein structure#Secondary structure, secondary structural elements are alpha helix, alpha helices and beta sheets, though beta turns and omega loops occur as well. Secondary structure elements typically spontaneously form as an intermediate before the protein protein folding, folds into its three dimensional protein tertiary structure, tertiary structure. Secondary structure is formally defined by the pattern of hydrogen bonds between the Amine, amino hydrogen and carboxyl oxygen atoms in the peptide backbone chain, backbone. Secondary structure may alternatively be defined based on the regular pattern of backbone Dihedral angle#Dihedral angles of proteins, dihedral angles in a particular region of the Ramachandran plot regardless of whether it has the correct hydrogen bonds. The concept of secondary structure was first introduced by Kaj Ulrik ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Prokaryote

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek πρό (, 'before') and κάρυον (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Connections". Pearson Education. San Francisco: 2003. In the two-empire system arising from the work of Édouard Chatton, prokaryotes were classified within the empire Prokaryota. But in the three-domain system, based upon molecular analysis, prokaryotes are divided into two domains: ''Bacteria'' (formerly Eubacteria) and ''Archaea'' (formerly Archaebacteria). Organisms with nuclei are placed in a third domain, Eukaryota. In the study of the origins of life, prokaryotes are thought to have arisen before eukaryotes. Besides the absence of a nucleus, prokaryotes also lack mitochondria, or most of the other membrane-bound organelles that characterize the eukaryotic cell. It was once thought that prokaryotic cellular components within the cytop ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |