|

Ukaz 493

Decree No. 493 "On citizens of Tatar nationality, formerly living in the Crimea" () was issued by the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet on 5 September 1967 proclaming that "Citizens of Tatar nationality formerly living in the Crimea" icwere officially legally rehabilitated and had "taken root" in places of residence. For many years the government claimed that the decree "settled" the "Tatar problem", despite the fact that it did not restore the rights of Crimean Tatars and formally made clear that they were no longer recognized as a distinct ethnic group. History While other deported peoples such as the Chechens, Ingush, Kalmyks, Karachays, and Balkars had long since been permitted to return to their native lands and their republics were restored in addition to other forms of political rehabilitation as recognized peoples, the very same decree of 24 November 1956 ŌĆ£On the restoration of national autonomies of the Kalmyk, Karachay, Chechen and Ingush peoplesŌĆØ (┬½ą× ą▓ąŠčüčüčéą░ąĮą ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Presidium Of The Supreme Soviet

The Presidium of the Supreme Soviet (russian: ą¤čĆąĄąĘąĖą┤ąĖčāą╝ ąÆąĄčĆčģąŠą▓ąĮąŠą│ąŠ ąĪąŠą▓ąĄčéą░, Prezidium Verkhovnogo Soveta) was a body of state power in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).The Presidium of the Supreme Council of the USSR (ą¤ąĀąĢąŚąśąöąśąŻą£ ąÆąĢąĀąźą×ąÆąØą×ąōą× ąĪą×ąÆąĢąóąÉ ąĪąĪąĪąĀ) . The presidium was elected by joint session of both houses of the |

Rowman & Littlefield

Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group is an independent publishing house founded in 1949. Under several imprints, the company offers scholarly books for the academic market, as well as trade books. The company also owns the book distributing company National Book Network based in Lanham, Maryland. History The current company took shape when University Press of America acquired Rowman & Littlefield in 1988 and took the Rowman & Littlefield name for the parent company. Since 2013, there has also been an affiliated company based in London called Rowman & Littlefield International. It is editorially independent and publishes only academic books in Philosophy, Politics & International Relations and Cultural Studies. The company sponsors the Rowman & Littlefield Award in Innovative Teaching, the only national teaching award in political science given in the United States. It is awarded annually by the American Political Science Association for people whose innovations have advanced ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Government Documents Of The Soviet Union

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state. In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a means by which organizational policies are enforced, as well as a mechanism for determining policy. In many countries, the government has a kind of constitution, a statement of its governing principles and philosophy. While all types of organizations have governance, the term ''government'' is often used more specifically to refer to the approximately 200 independent national governments and subsidiary organizations. The major types of political systems in the modern era are democracies, monarchies, and authoritarian and totalitarian regimes. Historically prevalent forms of government include monarchy, aristocracy, timocracy, oligarchy, democracy, theocracy, and tyranny. These forms are not always mutually exclusive, and mixed governme ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Politics Of The Crimean Tatars

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that studies politics and government is referred to as political science. It may be used positively in the context of a "political solution" which is compromising and nonviolent, or descriptively as "the art or science of government", but also often carries a negative connotation.. The concept has been defined in various ways, and different approaches have fundamentally differing views on whether it should be used extensively or limitedly, empirically or normatively, and on whether conflict or co-operation is more essential to it. A variety of methods are deployed in politics, which include promoting one's own political views among people, negotiation with other political subjects, making laws, and exercising internal and external force, including w ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Tashkent Ten

The Tashkent Ten were ten Crimean Tatar civil rights activists tried in Tashkent by the Uzbek Supreme Court from 1 July to 5 August 1969. The trial was sometimes called the Tashkent Process (Russian: ąóą░čłą║ąĄąĮčéčüą║ąĖą╣ ą┐čĆąŠčåąĄčüčü). They were tried under Articles 190-1 of the RSFSR The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, ąĀąŠčüčüąĖą╣čüą║ą░čÅ ąĪąŠą▓ąĄčéčüą║ą░čÅ ążąĄą┤ąĄčĆą░čéąĖą▓ąĮą░čÅ ąĪąŠčåąĖą░ą╗ąĖčüčéąĖč湥čüą║ą░čÅ ąĀąĄčüą┐čāą▒ą╗ąĖą║ą░, Ross├Łyskaya Sov├®tskaya Federat├Łvnaya Soci ... Criminal Code and similar codes of other Soviet republics for activities the prosecutor described as "being actively involved in solving the so-called Crimean Tatar issue ic. The case was investigated and prepared by Boris Berezovsky, who had a reputation for specializing in cases of Crimean Tatars. In line with standard practice at the time, the indictment and prosecution documents consistently labeled Crimean Tatars referred to in them not as ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Self-immolation

The term self-immolation broadly refers to acts of altruistic suicide, otherwise the giving up of one's body in an act of sacrifice. However, it most often refers specifically to autocremation, the act of sacrificing oneself by setting oneself on fire and burning to death. It is typically used for political or religious reasons, often as a form of non-violent protest or in acts of martyrdom. It has a centuries-long recognition as the most extreme form of protest possible by humankind. Etymology The English word '' immolation'' originally meant (1534) "killing a sacrificial victim; sacrifice" and came to figuratively mean (1690) "destruction, especially by fire". Its etymology was from Latin "to sprinkle with sacrificial meal (mola salsa); to sacrifice" in ancient Roman religion. ''Self-immolation'' was first recorded in Lady Morgan's ''France'' (1817). Effects Self-immolators frequently use accelerants before igniting themselves. This, combined with the self-immolators' refusal ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Residence Permit

A residence permit (less commonly ''residency permit'') is a document or card required in some regions, allowing a foreign national to reside in a country for a fixed or indefinite length of time. These may be permits for temporary residency, or permanent residency. The exact rules vary between regions. In some cases (e.g. the UK) a temporary residence permit is required to extend a stay past some threshold, and can be an intermediate step to applying for permanent residency. Residency status may be granted for a number of reasons and the criteria for acceptance as a resident may change over time. In New Zealand the current range of conditions include being a skilled migrant, a retired parent of a New Zealand National, an investor and a number of others. Biometric residence permit Some countries have adopted biometric residence permits, which are cards including embedded machine readable information and RFID NFC capable chips. In Georgia Georgia (country) offers several types ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Abdraim Reshidov

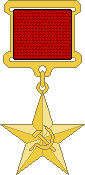

Abdraim Izmailovich Reshidov ( crh, Abduraim ─░smail o─¤lu Re┼¤idov, russian: ąÉą▒ą┤čĆą░ąĖą╝ ąśąĘą╝ą░ą╣ą╗ąŠą▓ąĖčć ąĀąĄčłąĖą┤ąŠą▓; 8 March 1912 ŌĆō 24 October 1984) was the deputy commander of the 162nd Guards Bomber Aviation Regiment of the Soviet Air Forces during World War II, known as the Great Patriotic War in the USSR. In 1945 while he held the rank of Major he was declared a Hero of the Soviet Union for his first 166 missions in a Pe-2 during the war. After the war he was heavily involved in the Crimean Tatar civil rights movement, and swore to the government that he would publicly commit self-immolation if they continued to refuse him the right of return. Early life Reshidov was born on 8 March 1912 to a Crimean Tatar family in the village of Mamashay, Crimea. After completing only five grades of school he began working at the workshops of Kachin Military Aviation School. In 1932 he graduated from the Simferopol Osoaviahim flight school, and in 1933 he entered the Red Army ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Hero Of The Soviet Union

The title Hero of the Soviet Union (russian: ąōąĄčĆąŠą╣ ąĪąŠą▓ąĄčéčüą║ąŠą│ąŠ ąĪąŠčĹʹ░, translit=Geroy Sovietskogo Soyuza) was the highest distinction in the Soviet Union, awarded together with the Order of Lenin personally or collectively for heroic feats in service to the Soviet state and society. Overview The award was established on 16 April 1934, by the Central Executive Committee of the Soviet Union. The first recipients of the title originally received only the Order of Lenin, the highest Soviet award, along with a certificate (ą│čĆą░ą╝ąŠčéą░, ''gramota'') describing the heroic deed from the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. Because the Order of Lenin could be awarded for deeds not qualifying for the title of hero, and to distinguish heroes from other Order of Lenin holders, the Gold Star medal was introduced on 1 August 1939. Earlier heroes were retroactively eligible for these items. A hero could be awarded the title again for a subsequent heroic feat with ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Yuri Andropov

Yuri Vladimirovich Andropov (ŌĆō 9 February 1984) was the sixth paramount leader of the Soviet Union and the fourth General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. After Leonid Brezhnev's 18-year rule, Andropov served in the post from November 1982 until his death in February 1984. Earlier in his career, Andropov served as the Soviet ambassador to Hungary from 1954 to 1957, during which time he was involved in the suppression of the 1956 Hungarian Uprising. He was named chairman of the KGB on 10 May 1967. In this position, he oversaw a massive crackdown on dissent carried out via mass arrests and involuntary psychiatric commitment of people deemed "socially undesirable". After Brezhnev suffered a stroke in 1975 that impaired his ability to govern, Andropov effectively dominated policy-making alongside Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko, Defense Minister Andrei Grechko and Grechko's successor, Marshal Dmitry Ustinov, for the rest of Brezhnev's rule. Upon Brezhnev ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Roman Rudenko

Roman Andreyevich Rudenko (russian: ąĀąŠą╝ą░╠üąĮ ąÉąĮą┤čĆąĄ╠üąĄą▓ąĖčć ąĀčāą┤ąĄ╠üąĮą║ąŠ, ŌĆō January 23, 1981) was a Soviet lawyer and statesman. Procurator-General of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic from 1944 to 1953, Rudenko became Procurator-General of the entire Soviet Union after 1953. He is well known internationally for acting as chief prosecutor for the USSR at the 1946 trial of the major Nazi war criminals in Nuremberg. He was also chief prosecutor at the "Trial of the Sixteen" (Polish Underground leaders) held in Moscow the year before. At the time he served at Nuremberg, Rudenko held the rank of Lieutenant-General within the USSR Procuracy. In 1961 Rudenko was elected to the CPSU Central Committee. In 1972 he was awarded the Soviet honorary title of Hero of Socialist Labor. Ukrainian SSR to 1953 Rudenko was one of the chief commandants of NKVD special camp Nr. 7, a former Nazi concentration camp, until its closure in 1950. Of the 60,000 prisoners in ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Nikolai Shchelokov

Nikolai Anisimovich Shchelokov; uk, ą£ąĖą║ąŠą╗ą░ ą×ąĮąĖčüąĖą╝ąŠą▓ąĖčć ą®ąŠą╗ąŠą║ąŠą▓ ( ŌĆō 13 December 1984) was a Soviet statesman and army general who served sixteen years as minister of internal affairs from 17 September 1966 to 17 December 1982. He was fired from all posts on corruption charges and committed suicide on 13 December 1984. Early life and education Shchelokov was born in Almazna, a large Cossack village near Luhansk in Donbas region of Russian Empire, on 26 November 1910. His father was a mine worker, and Shchelokov himself began working in the mines when he was fifteen years old. He attended Dzerzhinsky Metallurgical Institute and received a bachelor's degree in metallurgical engineering in 1933. Career Communist Party Shchelokov joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1931. In 1938, he was appointed first secretary of its committee in the Krasnogvardeysky district of Dnipropetrovsk. From 1939 to 1941 he was the chairman of the Dnipropetrovsk Cit ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |