|

Snare Technique (surgery)

SNARE proteins – " SNAP REceptor" – are a large protein family consisting of at least 24 members in yeasts, more than 60 members in mammalian cells, and some numbers in plants. The primary role of SNARE proteins is to mediate vesicle fusion – the fusion of vesicles with the target membrane; this notably mediates exocytosis, but can also mediate the fusion of vesicles with membrane-bound compartments (such as a lysosome). The best studied SNAREs are those that mediate the neurotransmitter release of synaptic vesicles in neurons. These neuronal SNAREs are the targets of the neurotoxins responsible for botulism and tetanus produced by certain bacteria. Types SNAREs can be divided into two categories: ''vesicle'' or ''v-SNAREs'', which are incorporated into the membranes of transport vesicles during budding, and ''target'' or ''t-SNAREs'', which are associated with nerve terminal membranes. Evidence suggests that t-SNAREs form stable subcomplexes which serve as guid ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Tetanus

Tetanus, also known as lockjaw, is a bacterial infection caused by ''Clostridium tetani'', and is characterized by muscle spasms. In the most common type, the spasms begin in the jaw and then progress to the rest of the body. Each spasm usually lasts a few minutes. Spasms occur frequently for three to four weeks. Some spasms may be severe enough to fracture bones. Other symptoms of tetanus may include fever, sweating, headache, trouble swallowing, high blood pressure, and a fast heart rate. Onset of symptoms is typically three to twenty-one days following infection. Recovery may take months. About ten percent of cases prove to be fatal. ''C. tetani'' is commonly found in soil, saliva, dust, and manure. The bacteria generally enter through a break in the skin such as a cut or puncture wound by a contaminated object. They produce toxins that interfere with normal muscle contractions. Diagnosis is based on the presenting signs and symptoms. The disease does not spread between pe ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Heptad Repeat

The heptad repeat is an example of a structural motif that consists of a repeating pattern of seven amino acids: ''a b c d e f g'' H P P H C P C where H represents hydrophobic residues, C represents, typically, charged residues, and P represents polar (and, therefore, hydrophilic) residues. The positions of the heptad repeat are commonly denoted by the lowercase letters ''a'' through ''g''. These motifs are the basis for most coiled coils and, in particular, leucine zippers, which have predominantly leucine in the ''d'' position of the heptad repeat. A conformational change in a heptad repeat in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein In virology, a spike protein or peplomer protein is a protein that forms a large structure known as a spike or peplomer projecting from the surface of an enveloped virus. as cited in The proteins are usually glycoproteins that form dimers or ... facilitates entry of the virus into the host cell membrane. References {{DEFAULTSORT:Heptad Repeat ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Sequence Motif

In biology, a sequence motif is a nucleotide or amino-acid sequence pattern that is widespread and usually assumed to be related to biological function of the macromolecule. For example, an ''N''-glycosylation site motif can be defined as ''Asn, followed by anything but Pro, followed by either Ser or Thr, followed by anything but Pro residue''. Overview When a sequence motif appears in the exon of a gene, it may encode the "structural motif" of a protein; that is a stereotypical element of the overall structure of the protein. Nevertheless, motifs need not be associated with a distinctive secondary structure. " Noncoding" sequences are not translated into proteins, and nucleic acids with such motifs need not deviate from the typical shape (e.g. the "B-form" DNA double helix). Outside of gene exons, there exist regulatory sequence motifs and motifs within the " junk", such as satellite DNA. Some of these are believed to affect the shape of nucleic acids (see for example RN ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Peroxisome

A peroxisome () is a membrane-bound organelle, a type of microbody, found in the cytoplasm of virtually all eukaryotic cells. Peroxisomes are oxidative organelles. Frequently, molecular oxygen serves as a co-substrate, from which hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is then formed. Peroxisomes owe their name to hydrogen peroxide generating and scavenging activities. They perform key roles in lipid metabolism and the conversion of reactive oxygen species. Peroxisomes are involved in the catabolism of very long chain fatty acids, branched chain fatty acids, bile acid intermediates (in the liver), D-amino acids, and polyamines, the reduction of reactive oxygen species – specifically hydrogen peroxide – and the biosynthesis of plasmalogens, i.e., ether phospholipids critical for the normal function of mammalian brains and lungs. They also contain approximately 10% of the total activity of two enzymes (Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase) in the pentose ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Mitochondria

A mitochondrion (; ) is an organelle found in the Cell (biology), cells of most Eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and Fungus, fungi. Mitochondria have a double lipid bilayer, membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is used throughout the cell as a source of chemical energy. They were discovered by Albert von Kölliker in 1857 in the voluntary muscles of insects. The term ''mitochondrion'' was coined by Carl Benda in 1898. The mitochondrion is popularly nicknamed the "powerhouse of the cell", a phrase coined by Philip Siekevitz in a 1957 article of the same name. Some cells in some multicellular organisms lack mitochondria (for example, mature mammalian red blood cells). A large number of unicellular organisms, such as microsporidia, parabasalids and diplomonads, have reduced or transformed their mitochondria into mitosome, other structures. One eukaryote, ''Monocercomonoides'', is known to have completely lost its mitocho ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

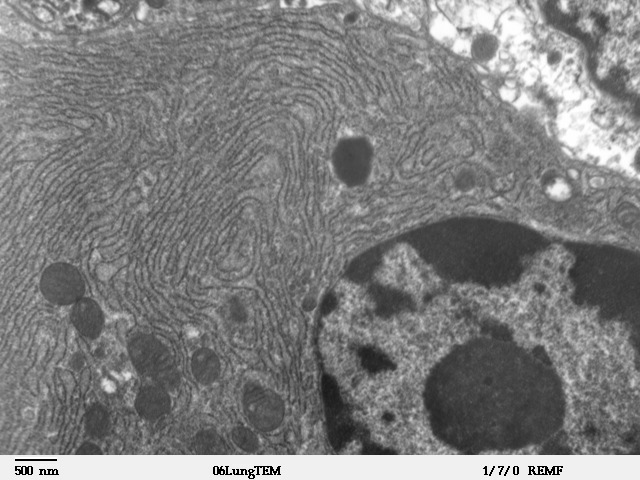

Endoplasmic Reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is, in essence, the transportation system of the eukaryotic cell, and has many other important functions such as protein folding. It is a type of organelle made up of two subunits – rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER), and smooth endoplasmic reticulum (SER). The endoplasmic reticulum is found in most eukaryotic cells and forms an interconnected network of flattened, membrane-enclosed sacs known as cisternae (in the RER), and tubular structures in the SER. The membranes of the ER are continuous with the outer nuclear membrane. The endoplasmic reticulum is not found in red blood cells, or spermatozoa. The two types of ER share many of the same proteins and engage in certain common activities such as the synthesis of certain lipids and cholesterol. Different types of cells contain different ratios of the two types of ER depending on the activities of the cell. RER is found mainly toward the nucleus of cell and SER towards the cell membrane or plasma ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Plasma Membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane (PM) or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of all cells from the outside environment (the extracellular space). The cell membrane consists of a lipid bilayer, made up of two layers of phospholipids with cholesterols (a lipid component) interspersed between them, maintaining appropriate membrane fluidity at various temperatures. The membrane also contains membrane proteins, including integral proteins that span the membrane and serve as membrane transporters, and peripheral proteins that loosely attach to the outer (peripheral) side of the cell membrane, acting as enzymes to facilitate interaction with the cell's environment. Glycolipids embedded in the outer lipid layer serve a similar purpose. The cell membrane controls the movement of substances in and out of cells and organelles, being selectively permeable to ions an ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Palmitoylation

Palmitoylation is the covalent attachment of fatty acids, such as palmitic acid, to cysteine (''S''-palmitoylation) and less frequently to serine and threonine (''O''-palmitoylation) residues of proteins, which are typically lipid bilayer, membrane proteins. The precise function of palmitoylation depends on the particular protein being considered. Palmitoylation enhances the hydrophobicity of proteins and contributes to their membrane association. Palmitoylation also appears to play a significant role in subcellular trafficking of proteins between membrane compartments, as well as in modulating protein–protein interactions. In contrast to prenylation and myristoylation, palmitoylation is usually reversible (because the bond between palmitic acid and protein is often a thioester bond). The reverse reaction in mammalian cells is catalyzed by Acyl-protein thioesterase, acyl-protein thioesterases (APTs) in the cytosol and palmitoyl protein thioesterases in lysosomes. Because palm ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

SNAP-25

Synaptosomal-Associated Protein, 25kDa (SNAP-25) is a Target Soluble NSF (''N''-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor) Attachment Protein Receptor (t-SNARE) protein encoded by the ''SNAP25'' gene found on chromosome 20p12.2 in humans. SNAP-25 is a component of the ''trans''-SNARE complex, which accounts for membrane fusion specificity and directly executes fusion by forming a tight complex that brings the synaptic vesicle and plasma membranes together. Structure and function SNAP-25, a Q-SNARE protein, is anchored to the cytosolic face of membranes via palmitoyl side chains covalently bound to cysteine amino acid residues in the central linker domain of the molecule. This means that SNAP-25 does not contain a trans-membrane domain. SNAP-25 has been identified to contribute two α-helices to the SNARE complex, a four-α-helix domain complex. The SNARE complex participates in vesicle fusion, which involves the docking, priming and merging of a vesicle with the cell membrane to in ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Transmembrane Domain

A transmembrane domain (TMD) is a membrane-spanning protein domain. TMDs generally adopt an alpha helix topological conformation, although some TMDs such as those in porins can adopt a different conformation. Because the interior of the lipid bilayer is hydrophobic, the amino acid residues in TMDs are often hydrophobic, although proteins such as membrane pumps and ion channels can contain polar residues. TMDs vary greatly in length, sequence, and hydrophobicity, adopting organelle-specific properties. Functions of transmembrane domains Transmembrane domains are known to perform a variety of functions. These include: * Anchoring transmembrane proteins to the membrane. *Facilitating molecular transport of molecules such as ions and proteins across biological membranes; usually hydrophilic residues and binding sites in the TMDs help in this process. *Signal transduction across the membrane; many transmembrane proteins, such as G protein-coupled receptors, receive extracellular ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Caenorhabditis Elegans

''Caenorhabditis elegans'' () is a free-living transparent nematode about 1 mm in length that lives in temperate soil environments. It is the type species of its genus. The name is a blend of the Greek ''caeno-'' (recent), ''rhabditis'' (rod-like) and Latin ''elegans'' (elegant). In 1900, Maupas initially named it '' Rhabditides elegans.'' Osche placed it in the subgenus ''Caenorhabditis'' in 1952, and in 1955, Dougherty raised ''Caenorhabditis'' to the status of genus. ''C. elegans'' is an unsegmented pseudocoelomate and lacks respiratory or circulatory systems. Most of these nematodes are hermaphrodites and a few are males. Males have specialised tails for mating that include spicules. In 1963, Sydney Brenner proposed research into ''C. elegans,'' primarily in the area of neuronal development. In 1974, he began research into the molecular and developmental biology of ''C. elegans'', which has since been extensively used as a model organism. It was the first multicellu ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

.png)