|

Sedimentary Exhalative Deposit

Sedimentary exhalative deposits (SEDEX or SedEx deposits) are zinc-lead deposits originally interpreted to have been formed by discharge of metal-bearing basinal fluids onto the seafloor resulting in the precipitation of mainly stratiform ore, often with thin laminations of sulphide minerals. Goodfellow, W.D., Lydon, J.W. (2007) Sedimentary exhalative (SEDEX) deposits. In: Goodfellow, W.D. (Ed.) Mineral deposits of Canada: a synthesis of major deposit types, district metallogeny, the evolution of geological provinces, and exploration methods. Geological Association of Canada Special Publication 5, 163–183. SEDEX deposits are hosted largely by clastic rocks deposited in intracontinental rifts or failed rift basins and passive continental margins. Since these ore deposits frequently form massive sulfide lenses, they are also named ''sediment''-hosted massive sulfide (SHMS) deposits, as opposed to ''volcanic''-hosted massive sulfide (VHMS) deposits. The sedimentary appearanc ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Sullivan Mine

The Sullivan Mine is a now-closed conventional–mechanized underground mine located in Kimberley, British Columbia, Canada. The ore body is a complex, sediment-hosted, sedimentary exhalative deposit consisting primarily of zinc, lead, and iron sulphides. Lead, zinc, silver and tin were the economic metals produced. The deposit lies within the lower part of the Purcell Supergroup and mineralization occurred about 1470 million years ago during the late Precambrian (Mesoproterozoic).Jaing, S.-Y., Slack, J.F. and Palmer, M.R. 2000. Sm-Nd dating of the giant Pb-Zn-Ag deposit, British Columbia. Geology, vol. 28, no. 8, p. 751-754. The deposit was discovered in 1892 and acquired in 1909 by the CPR-owned Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company of Canada (later Cominco Ltd. and Teck Cominco). The mine's economic success resulted largely from Sullivan's 1916 development of the differential flotation process that allowed separate recovery of lead and zinc concentrates in the milling ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Ocean Topography

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as 'seabeds'. The structure of the seabed of the global ocean is governed by plate tectonics. Most of the ocean is very deep, where the seabed is known as the abyssal plain. Seafloor spreading creates mid-ocean ridges along the center line of major ocean basins, where the seabed is slightly shallower than the surrounding abyssal plain. From the abyssal plain, the seabed slopes upward toward the continents and becomes, in order from deep to shallow, the continental rise, slope, and shelf. The depth within the seabed itself, such as the depth down through a sediment core, is known as the “depth below seafloor.” The ecological environment of the seabed and the deepest waters are collectively known, as a habitat for creatures, as the “benthos.” Most of the seabed throughout the world's oceans is covered in layers of marine sediments ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Sericite

Sericite is the name given to very fine, ragged grains and aggregates of white (colourless) micas, typically made of muscovite, illite, or paragonite. Sericite is produced by the alteration of orthoclase or plagioclase feldspars in areas that have been subjected to hydrothermal alteration typically associated with copper, tin, or other hydrothermal ore deposits. Sericite also occurs as the fine mica that gives the sheen to phyllite and schistose metamorphic rocks. The name comes from Latin ''sericus'', meaning "silken" in reference to the location from which silk was first utilized, which in turn refers to the silky sheen of rocks with abundant sericite. File:Granite pmg ss 2006.jpg, Granite in thin section under cross-polarized light in which feldspar crystals exhibit sericite alteration. File:Staurolite garnet schist 3mm xp 2007.jpg, Staurolite-garnet schist in thin section under cross-polarized light with sericite. References External linksMindat [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Chlorite Group

The chlorites are the group of phyllosilicate minerals common in low-grade metamorphic rocks and in altered igneous rocks. Greenschist, formed by metamorphism of basalt or other low-silica volcanic rock, typically contains significant amounts of chlorite. Chlorite minerals show a wide variety of compositions, in which magnesium, iron, aluminium, and silicon substitute for each other in the crystal structure. A complete solid solution series exists between the two most common end members, magnesium-rich clinochlore and iron-rich chamosite. In addition, manganese, zinc, lithium, and calcium species are known. The great range in composition results in considerable variation in physical, optical, and X-ray properties. Similarly, the range of chemical composition allows chlorite group minerals to exist over a wide range of temperature and pressure conditions. For this reason chlorite minerals are ubiquitous minerals within low and medium temperature metamorphic rocks, some igneous r ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Siderite

Siderite is a mineral composed of iron(II) carbonate (FeCO3). It takes its name from the Greek word σίδηρος ''sideros,'' "iron". It is a valuable iron mineral, since it is 48% iron and contains no sulfur or phosphorus. Zinc, magnesium and manganese commonly substitute for the iron resulting in the siderite-smithsonite, siderite- magnesite and siderite-rhodochrosite solid solution series. Siderite has Mohs hardness of 3.75-4.25, a specific gravity of 3.96, a white streak and a vitreous lustre or pearly luster. Siderite is antiferromagnetic below its Néel temperature of 37 K which can assist in its identification. It crystallizes in the trigonal crystal system, and are rhombohedral in shape, typically with curved and striated faces. It also occurs in masses. Color ranges from yellow to dark brown or black, the latter being due to the presence of manganese. Siderite is commonly found in hydrothermal veins, and is associated with barite, fluorite, galena, and others. It i ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Ankerite

Ankerite is a calcium, iron, magnesium, manganese carbonate mineral of the group of rhombohedral carbonates with the chemical formula . In composition it is closely related to dolomite, but differs from this in having magnesium replaced by varying amounts of iron(II) and manganese. It forms a series with dolomite and kutnohorite. The crystallographic and physical characters resemble those of dolomite and siderite. The angle between the perfect rhombohedral cleavages is 73° 48', the hardness is 3.5 to 4, and the specific gravity is 2.9 to 3.1. The color is white, grey or reddish to yellowish brown. Ankerite occurs with siderite in metamorphosed ironstones and sedimentary banded iron formations. It also occurs in carbonatites. In sediments it occurs as authigenic, diagenetic minerals and as a product of hydrothermal deposition. It is one of the minerals of the dolomite-siderite series, to which the terms brown-spar, pearl-spar and bitter-spar have been historically loosely applied ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Vein (geology)

In geology, a vein is a distinct sheetlike body of crystallized minerals within a rock. Veins form when mineral constituents carried by an aqueous solution within the rock mass are deposited through precipitation. The hydraulic flow involved is usually due to hydrothermal circulation. Veins are classically thought of as being the ones in the body not the rock veins and arteries planar fractures in rocks, with the crystal growth occurring normal to the walls of the cavity, and the crystal protruding into open space. This certainly is the method for the formation of some veins. However, it is rare in geology for significant open space to remain open in large volumes of rock, especially several kilometers below the surface. Thus, there are two main mechanisms considered likely for the formation of veins: ''open-space filling'' and ''crack-seal growth''. Open space filling Open space filling is the hallmark of epithermal vein systems, such as a stockwork, in greisens or in cert ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

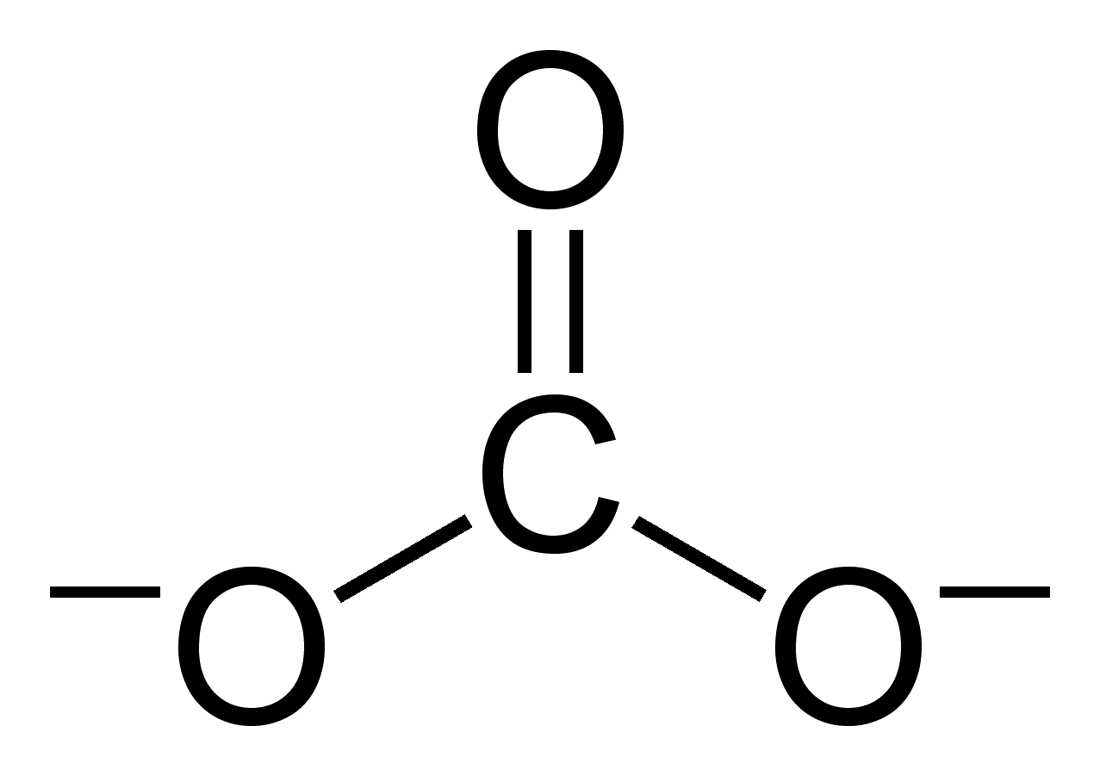

Carbonate

A carbonate is a salt of carbonic acid (H2CO3), characterized by the presence of the carbonate ion, a polyatomic ion with the formula . The word ''carbonate'' may also refer to a carbonate ester, an organic compound containing the carbonate group C(=O)(O–)2. The term is also used as a verb, to describe carbonation: the process of raising the concentrations of carbonate and bicarbonate ions in water to produce carbonated water and other carbonated beverageseither by the addition of carbon dioxide gas under pressure or by dissolving carbonate or bicarbonate salts into the water. In geology and mineralogy, the term "carbonate" can refer both to carbonate minerals and carbonate rock (which is made of chiefly carbonate minerals), and both are dominated by the carbonate ion, . Carbonate minerals are extremely varied and ubiquitous in chemically precipitated sedimentary rock. The most common are calcite or calcium carbonate, CaCO3, the chief constituent of limestone (as well a ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon-oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall chemical formula of SiO2. Quartz is the second most abundant mineral in Earth's continental crust, behind feldspar. Quartz exists in two forms, the normal α-quartz and the high-temperature β-quartz, both of which are chiral. The transformation from α-quartz to β-quartz takes place abruptly at . Since the transformation is accompanied by a significant change in volume, it can easily induce microfracturing of ceramics or rocks passing through this temperature threshold. There are many different varieties of quartz, several of which are classified as gemstones. Since antiquity, varieties of quartz have been the most commonly used minerals in the making of jewelry and hardstone carvings, especially in Eurasia. Quartz is the mineral defining the val ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Breccia

Breccia () is a rock composed of large angular broken fragments of minerals or rocks cemented together by a fine-grained matrix. The word has its origins in the Italian language, in which it means "rubble". A breccia may have a variety of different origins, as indicated by the named types including sedimentary breccia, tectonic breccia, igneous breccia, impact breccia, and hydrothermal breccia. A megabreccia is a breccia composed of very large rock fragments, sometimes kilometers across, which can be formed by landslides, impact events, or caldera collapse. Types Breccia is composed of coarse rock fragments held together by cement or a fine-grained matrix. Like conglomerate, breccia contains at least 30 percent of gravel-sized particles (particles over 2mm in size), but it is distinguished from conglomerate because the rock fragments have sharp edges that have not been worn down. These indicate that the gravel was deposited very close to its source area, since otherwise th ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Celsius

The degree Celsius is the unit of temperature on the Celsius scale (originally known as the centigrade scale outside Sweden), one of two temperature scales used in the International System of Units (SI), the other being the Kelvin scale. The degree Celsius (symbol: °C) can refer to a specific temperature on the Celsius scale or a unit to indicate a difference or range between two temperatures. It is named after the Swedish astronomer Anders Celsius (1701–1744), who developed a similar temperature scale in 1742. Before being renamed in 1948 to honour Anders Celsius, the unit was called ''centigrade'', from the Latin ''centum'', which means 100, and ''gradus'', which means steps. Most major countries use this scale; the other major scale, Fahrenheit, is still used in the United States, some island territories, and Liberia. The Kelvin scale is of use in the sciences, with representing absolute zero. Since 1743 the Celsius scale has been based on 0 °C for the freezing ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |